Abstract

1. Striated muscle fibres were found in each of twenty consecutive pineal glands cultured from individual neonatal rats.

2. In subsequent experiments performed with dissociated cultures of pineal organs pooled from several litters, myotubes were first visible after about 1 week in culture.

3. During the next several weeks the myotubes increased in size, developed crossstriations, and began to twitch spontaneously.

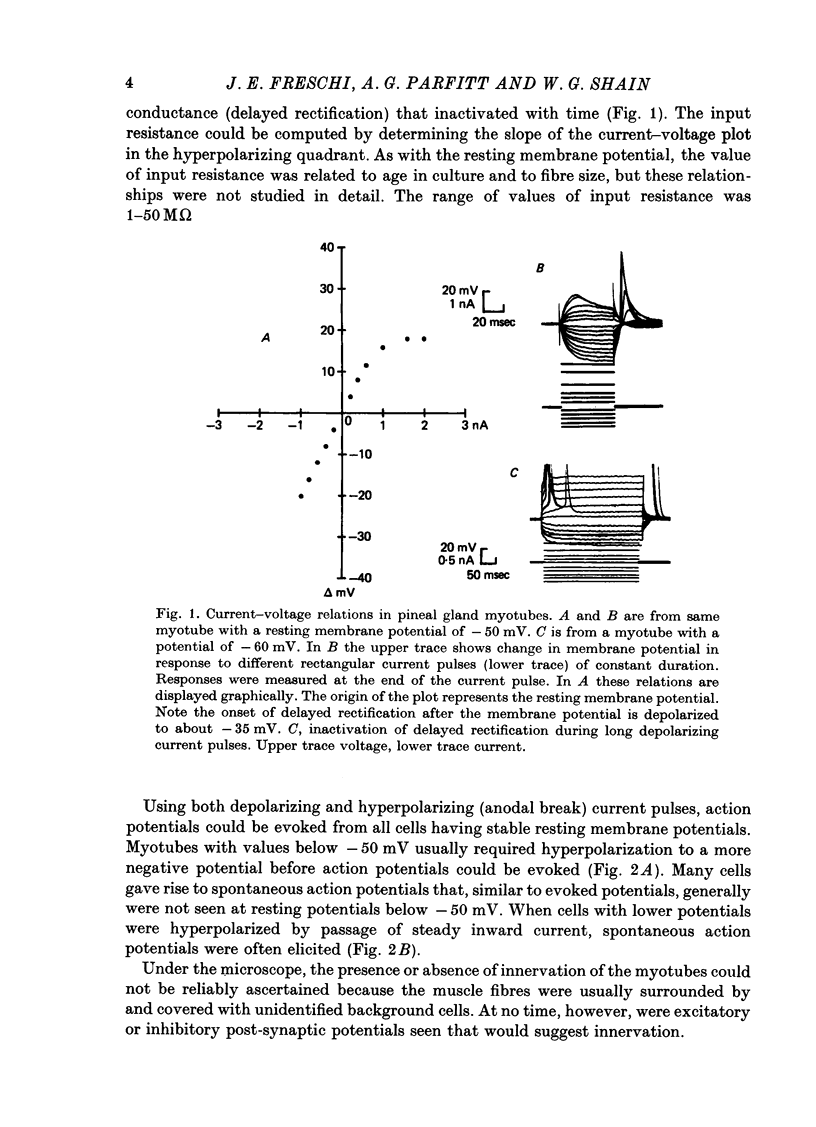

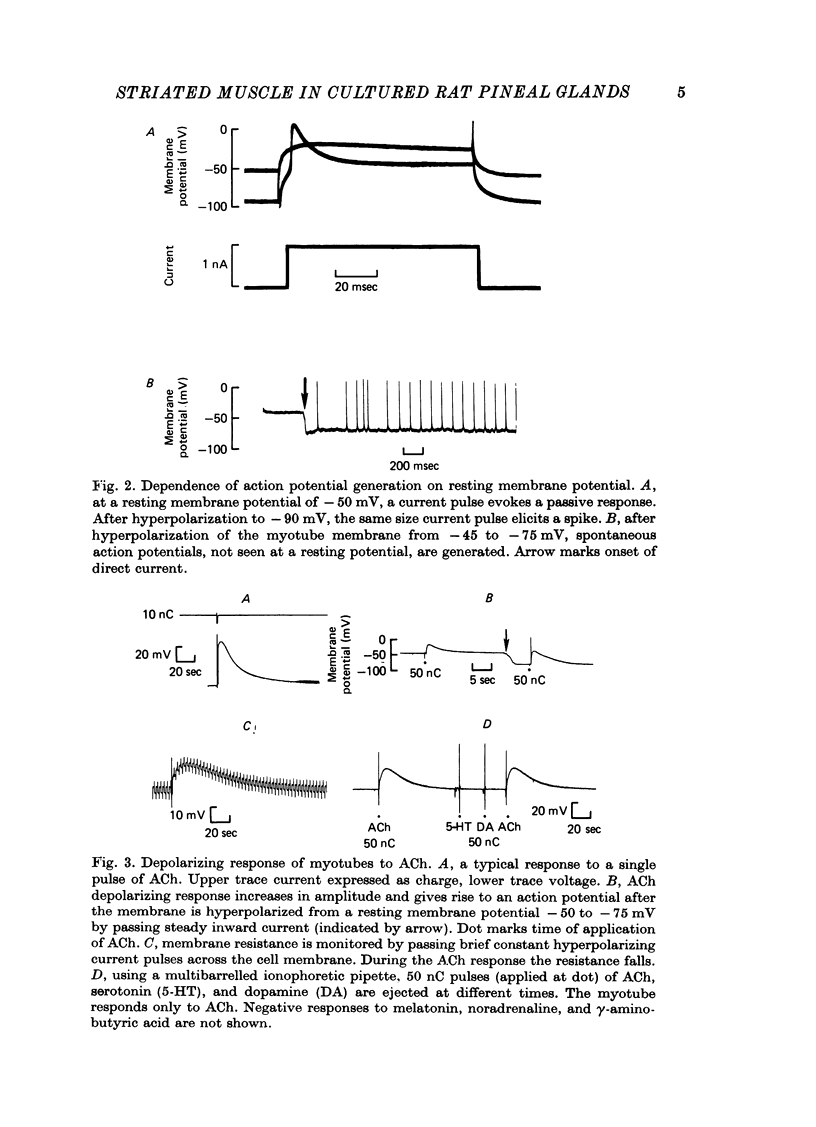

4. The resting membrane potential increased with age in culture. All myotubes studied showed delayed rectification. Action potentials either occurred spontaneously or could be evoked if the membrane were sufficiently polarized. No spontaneous end plate potentials were seen.

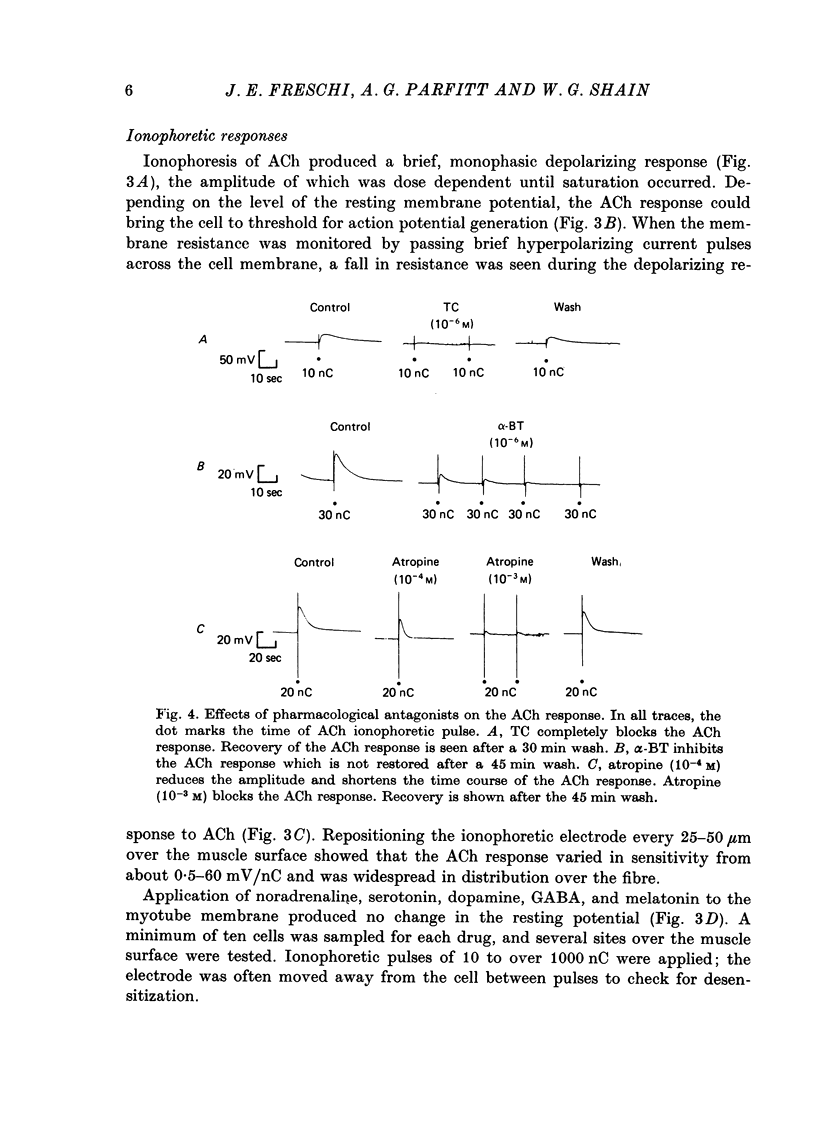

5. Acetylcholine (ACh) produced a brief, monophasic depolarizing response. Noradrenaline, serotonin, melatonin, dopamine, and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) had no effect on the resting membrane potential when applied iontophoretically.

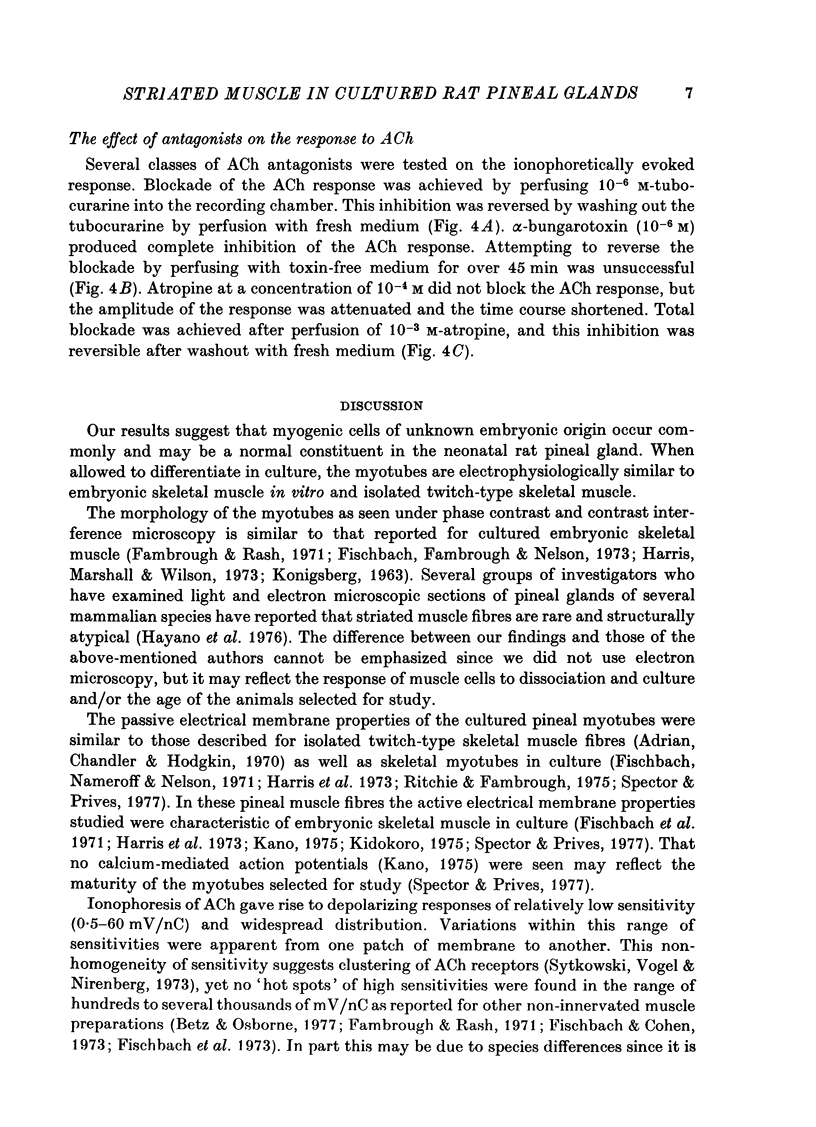

6. The ACh response was reversibly blocked by 10-6 M-tubocurarine and irreversibly blocked by 10-6 M-α-bungarotoxin. Atropine (10-4 M) reduced the amplitude and shortened the time course of the ACh response, and 10-3 M-atropine produced complete but reversible inhibition.

7. We conclude that pineal muscle fibres are electrophysiologically and pharmacologically similar to skeletal muscle fibres in vitro. Although the pineal gland has undetectable levels of ACh, pineal muscle develops ACh receptors but not noradrenaline, serotonin, melatonin, dopamine, or GABA receptors mediating electrophysiological responses, although these latter substances (except dopamine) are found in the pineal.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Adler M., Albuquerque E. X. An analysis of the action of atropine and scopolamine on the end-plate current of frog sartorius muscle. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1976 Feb;196(2):360–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adrian R. H., Chandler W. K., Hodgkin A. L. Voltage clamp experiments in striated muscle fibres. J Physiol. 1970 Jul;208(3):607–644. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1970.sp009139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Askanas V., Engel W. K., Ringel S. P., Bender A. N. Acetylcholine receptors of aneurally cultured human and animal muscle. Neurology. 1977 Nov;27(11):1019–1022. doi: 10.1212/wnl.27.11.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beránek R., Vyskocil F. The effect of atropine on the frog sartorius neuromuscular junction. J Physiol. 1968 Mar;195(2):493–503. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1968.sp008470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betz W., Osborne M. Effects of innervation on acetylcholine sensitivity of developing muscle in vitro. J Physiol. 1977 Aug;270(1):75–88. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1977.sp011939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coon H. G. Clonal stability and phenotypic expression of chick cartilage cells in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1966 Jan;55(1):66–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.55.1.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coon H. G., Weiss M. C. A quantitative comparison of formation of spontaneous and virus-produced viable hybrids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1969 Mar;62(3):852–859. doi: 10.1073/pnas.62.3.852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fambrough D., Hartzell H. C., Rash J. E., Ritchie A. K. Trophic functions of the neuron. I. Development of neural connections. Receptor properties of developing muscle. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1974 Mar 22;228(0):47–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1974.tb20501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fambrough D., Rash J. E. Development of acetylcholine sensitivity during myogenesis. Dev Biol. 1971 Sep;26(1):55–68. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(71)90107-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltz A., Large W. A., Trautmann A. Analysis of atropine action at the frog neutromuscular junction. J Physiol. 1977 Jul;269(1):109–130. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1977.sp011895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischbach G. D., Cohen S. A. The distribution of acetylcholine sensitivity over uninnervated and innervated muscle fibers grown in cell culture. Dev Biol. 1973 Mar;31(1):147–162. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(73)90326-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischbach G. D., Fambrough D., Nelson P. G. A discussion of neuron and muscle cell cultures. Fed Proc. 1973 Jun;32(6):1636–1642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischbach G. D., Nameroff M., Nelson P. G. Electrical properties of chick skeletal muscle fibers developing in cell culture. J Cell Physiol. 1971 Oct;78(2):289–299. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1040780218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidotti A., Badiani G., Pepeu G. Taurine distribution in cat brain. J Neurochem. 1972 Feb;19(2):431–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1972.tb01352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris J. B., Marshall M. W., Wilson P. A physiological study of chick myotubes grown in tissue culture. J Physiol. 1973 Mar;229(3):751–766. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1973.sp010165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayano M., Sung J. H., Mastri A. R., Hill E. G. Striated muscle in the pineal gland of swine. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1976 Nov-Dec;35(6):613–621. doi: 10.1097/00005072-197611000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KONIGSBERG I. R. Clonal analysis of myogenesis. Science. 1963 Jun 21;140(3573):1273–1284. doi: 10.1126/science.140.3573.1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kano M. Development of excitability in embryonic chick skeletal muscle cells. J Cell Physiol. 1975 Dec;86(3 Pt 1):503–510. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1040860307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz B., Miledi R. The binding of acetylcholine to receptors and its removal from the synaptic cleft. J Physiol. 1973 Jun;231(3):549–574. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1973.sp010248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz B., Miledi R. The effect of atropine on acetylcholine action at the neuromuscular junction. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1973 Nov 27;184(1075):221–226. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1973.0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz B., Miledi R. The statistical nature of the acetycholine potential and its molecular components. J Physiol. 1972 Aug;224(3):665–699. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1972.sp009918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidokoro Y. Developmental changes of membrane electrical properties in a rat skeletal muscle cell line. J Physiol. 1975 Jan;244(1):129–143. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1975.sp010787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathanson M. A., Binkley S., Hilfer R. Cultivation of mammalian pineal cells: retention of organization and function in tissue culture. In Vitro. 1977;13(12):843–848. doi: 10.1007/BF02615133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QUAY W. B. HISTOLOGICAL STRUCTURE AND CYTOLOGY OF THE PINEAL ORGAN IN BIRDS AND MAMMALS. Prog Brain Res. 1965;10:49–86. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)63447-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie A. K., Fambrough D. M. Electrophysiological properties of the membrane and acetylcholine receptor in developing rat and chick myotubes. J Gen Physiol. 1975 Sep;66(3):327–355. doi: 10.1085/jgp.66.3.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossier J., Vargo T. M., Minick S., Ling N., Bloom F. E., Guillemin R. Regional dissociation of beta-endorphin and enkephalin contents in rat brain and pituitary. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977 Nov;74(11):5162–5165. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.11.5162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe V., Neale E. A., Avins L., Guroff G., Schrier B. K. Pineal gland cells in culture. Morphology, Biochemistry, Differentiation, and co-culture with sympathetic neurons. Exp Cell Res. 1977 Feb;104(2):345–356. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(77)90100-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrier B. K., Klein D. C. Absence of choline acetyltransferase in rat and rabbit pineal gland. Brain Res. 1974 Oct 18;79(2):347–351. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(74)90431-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spector I., Prives J. M. Development of electrophysiological and biochemical membrane properties during differentiation of embryonic skeletal muscle in culture. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977 Nov;74(11):5166–5170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.11.5166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sytkowski A. J., Vogel Z., Nirenberg M. W. Development of acetylcholine receptor clusters on cultured muscle cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1973 Jan;70(1):270–274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.1.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel Z., Sytkowski A. J., Nirenberg M. W. Acetylcholine receptors of muscle grown in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1972 Nov;69(11):3180–3184. doi: 10.1073/pnas.69.11.3180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurtman R. J., Moskowitz M. A. The pineal organ (Second of two parts). N Engl J Med. 1977 Jun 16;296(24):1383–1386. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197706162962405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]