The amount of biomedical knowledge doubles every 20 years, and new classes of drug (such as phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors) become available when lectures at medical school are over. Therefore, a practice risks fossilising after doctors finish professional training. Many continuing medical education or continuing professional development activities help doctors carry on learning and improving their skills. These activities include courses, conferences, mailed educational materials, weekly grand rounds, journal clubs, and using internet sites. In many countries, evidence of this process is needed for doctors to continue to practice. Although these activities may increase knowledge, their impact on clinical practice is variable

The aim of traditional medical education is to commit knowledge to memory and then use this knowledge in the workplace. The way knowledge is learnt influences its recall and application to work. One tactic to improve the process is to ensure that learning happens in the clinical workplace. Lessons are learnt faster and recalled more reliably when they originate in everyday experience.

Learning in the workplace means spending a minute here or three minutes there to find answers prompted by the clinical questions and learning opportunities that come up in every working day, rather than doing continuing medical education for an intensive two hours a week, or a few days a year. Workplace learning is hard to achieve. It emphasises problem solving and learning skills—such as how to find relevant answers fast—not learning facts.

Barriers and solutions

Nobody can find a satisfactory answer to every clinical question or information need, especially as there are about two needs for every three clinical encounters. Many important clinical questions have no satisfactory answer—for example, what is the cause of motor neurone disease? Other questions are simply interesting rather than information needs. A range of practical difficulties face doctors who follow the approach of learning in the workplace. Some suggestions about how to overcome the difficulties follow.

Too many questions, not enough time

Doctors generate approximately 45 questions about patient care every week, and they probably allow two minutes to answer each one. This adds up to an extra hour and a half per week, and even though it represents only 3% of their working time, where do doctors find this time? Time is always short. They often have to adjust the threshold for seeking answers, prioritising questions that have the highest clinical impact and are quickest to answer.

Figure 1.

In the United Kingdom, the National electronic Library for Health aims to provide answers within 15 seconds that take only 15 seconds to read

Prioritising clinical questions by the likely impact of the answer means distinguishing between the questions in the box opposite. When doctors have time, they can pursue all answers. When under pressure, they pursue answers that are needed now (category 1). If they never pursue other answers, they will miss many clinical advances. It is often hard to recognise when knowledge is lacking, and so it is important to sometimes pursue answers even when only slightly uncertain of the answer.

Table 1.

Prioritisation of clinical questions

| 1 Answers needed now |

| 2 Answers needed before patient is seen next |

| 3 Answers needed to guide care of other patients or to reorganise clinical practice |

| 4 Answers that have interest to doctor and patient, but carry no obvious clinical impact |

This is the ninth in a series of 12 articles A glossary of terms is available at http://bmj.com/cgi/content/full/331/7516/566/DC1

Patrick Murphy is a 8 year old boy who has recently returned home from a hospital admission. The discharge letter asks you to prescribe inhaled steroids and a phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor

Workplace learning means finding solutions to clinical problems when they arise, or soon after, with minimum effort. When unsure about what has happened, why, or what to do, answers should be looked up

To ease time pressure, clinicians can spend less time answering a question by using knowledge resources that are comprehensive, and can be instantly accessed and easily searched. They could also increase the time available for workplace learning. Individually, doctors can work for longer hours, reserving time for “reflective practice” with a preceptor or mentor, exploiting “teachable moments,” perhaps by answering an educational prescription. Overall, the medical profession needs to recognise the sanctity of workplace learning throughout doctors' careers: life long, self directed learning.

Table 2.

Turning clinical problems into easily investigated formats

| Patient or problem | Intervention (or cause, prognostic factor, treatment) | Comparison (if necessary) | Outcomes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tips for building | Starting with your patient ask “How would I describe a group of patients similar to mine?” Balance precision with brevity | Ask “Which main intervention am I considering?” Be specific | Ask “What is the main alternative to compare with the intervention?” Be specific | Ask “What can I hope to accomplish?” or “What could this exposure really affect?” Be specific |

| Example (see scenario on p 1129) | In children with poorly controlled asthma... | “...would adding phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor to inhaled corticosteroid...” | “...when compared with adding a long acting β agonist...” | “...reduce the likelihood of readmission?” |

Lack of clear questions

Asking clear questions is not easy. Sometimes doctors feel uncertain and fail to formalise a question, which makes it harder to find the answer. Immediate identification of clinical questions is important, and is easiest to do on ward rounds or when teaching students. When working alone, some clinicians log their questions (for example, on BMJLearning), then look up the learning resources on the website (the “just in time learning” package on childhood asthma) or other sources, or they discuss the answer with peers later. Structuring clinical questions using the problem, intervention, comparison and outcome (PICO) model makes them easier to focus, recall, and answer.

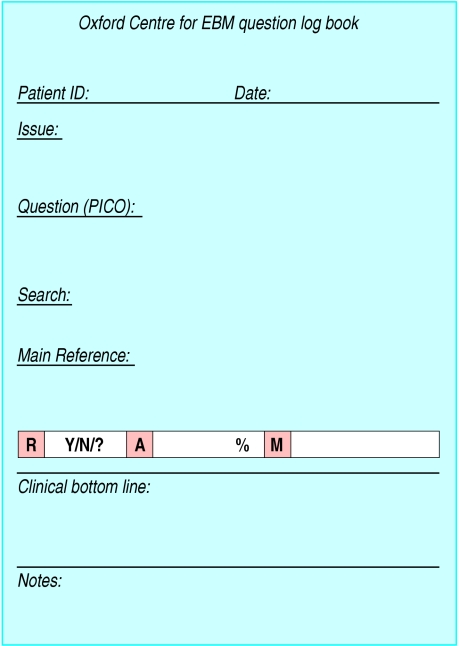

Figure 2.

Adapted from a page from the Oxford Centre for Evidence Based Medicine's logbook (R=randomised and representative, A=ascertainment or follow-up rate percentage, M=measures unbiased, relevant

Lack of answers

A source of answers needs to be available in the workplace. This source should provide answers that are clinically relevant, scientifically sound, and in a form that can influence decisions. One solution is a library in the workplace that contains current text and reference books, relevant reprints, and electronic resources. The library must be close and organised for rapid access. The material should be filtered for clinical relevance and be evidence based, such as Clinical Evidence in book or CD-Rom format or an indexed collection of systematic reviews.

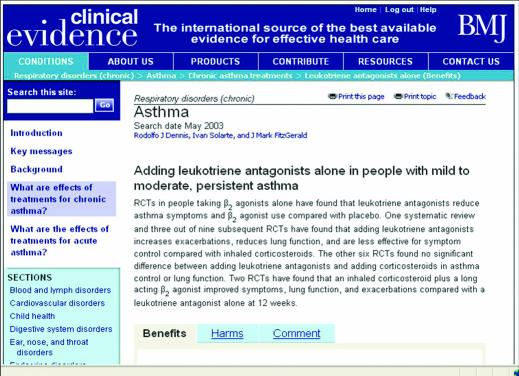

Figure 3.

Clinical evidence is a useful resource in workplace learning

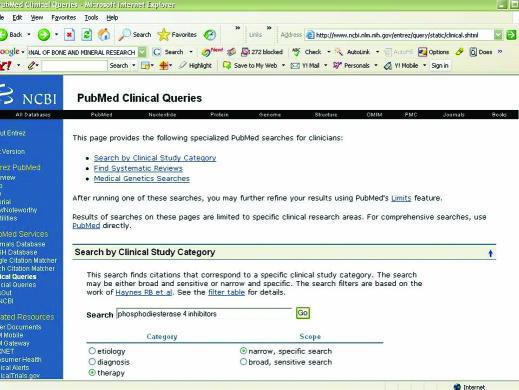

These sources will not answer all questions. In Patrick Murphy's case (see scenario on p 1129) the treatment is not indexed, and so online access to Medline will be needed, preferably via the PubMed clinical queries search page that provides answers useful to practicing doctors. Ideally, doctors will then retrieve the full text of relevant articles because relying on the abstract alone can be misleading. When Pitkin compared the statements made in 264 structured abstracts in six medical journals with the corresponding article, a fifth contained statements that were not substantiated in the article and 28% contained statements that disagreed with those in the article. Thus, tempting though it may be to rely on abstracts alone—especially because they are now so accessible through PubMed—it can be dangerous.

An alternative to carrying out the search yourself is to call or email a question answering service, such as ATTRACT, for clinicians working in Wales. For years, NHS poisons and drug information services have provided similar services that give instant answers to specialist questions. Some libraries, primary care trusts and academic departments have services that cover many topics. The service usually returns a telephone call or sends a summary within two to four hours. Despite their obvious potential, these services seem underused at present.

Figure 4.

A PubMed search filters for clinical queries

Parochialism

If doctors only look up answers to questions arising in their own practice, their knowledge will depend on the local case mix. Most doctors broaden their knowledge by reading a general medical journal or looking up points raised in replies to referrals, inpatient summaries, clinic letters, or laboratory reports. Some participate in multidisciplinary clinics or ward rounds, or join colleagues in an email discussion group. To be ready for rare, serious problems that need an instant response, some clinicians use patient simulators to practice managing cardiopulmonary arrest, anaesthetic accidents, or brittle diabetes. Although time spent on simulators does not yet count towards doctors' continuing education, taking part in interactive cases in some journals does.

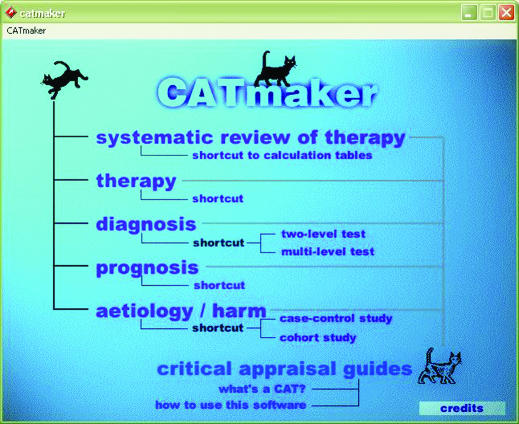

Figure 5.

The CATmaker tool is used to create critically appraised topics

Lack of incentives

To maintain the enthusiasm to keep looking up answers to clinical questions, doctors can keep a log book of questions and answers, or conduct clinical audits that compare practice and outcomes with results a year ago. Such log books and audit reports will become part of doctors' folders for accreditation and annual appraisal.

Table 3.

Cultural changes associated with workplace learning

| Old think | New think |

|---|---|

| • Passive listening to lectures | • Active participation in self directed learning |

| • Educator decides topic | • You decide topic |

| • Attend continuing medical education course you know most about | • Seek out areas of ignorance and answers to your clinical questions |

| • Focus is on laboratory research, pathophysiology, drug mechanisms | • Focus is on what works in practice, what to do, problem solving |

| • Read a journal or textbook | • Carry out problem solving on real or simulated cases |

| • Education to learn facts, pass exams | • Learning to solve clinical problems, improve team work, clinical and information seeking skills |

| • Formal, timed courses | • Informal, self directed, learning in the workplace |

| • Get continuing medical education or postgraduate education allowance points for turning up | • Get continuing medical education or postgraduate education allowance points for participating in workplace learning, using learning materials, improving standards |

| • Case presentation, journal club | • Work on an educational prescription, write a critically appraised topic, use a clinical simulator |

| • Competition: keep knowledge to yourself | • Sharing: open learning, exchange of knowledge and understanding to benefit patients and the health system |

| • Knowledge belongs to the individual. Continuing medical education points accumulate to the individual. Recertify the individual | • Communities of practice: learning is an attribute of the team and organisation and is part of its quality and risk management strategies. Accredit the organisation |

| • Patients are passive recipients of care | • Patients are sources of questions and insights, learning collaborators |

| • Errors should be forgotten and denied | • Errors are a learning experience to be treasured, discussed, and understood |

| • Errors happen to “bad apples” | • Errors happen to everyone |

Sharing insights is an incentive to learn, and giving a presentation often prompts discussion, especially if it is short, and it defines and deals with a real clinical problem (along with sources searched, the answers found, and actions taken). This activity can be formalised as a single page, dated, critically appraised topic (CAT), and stored in a loose leaf folder or a practice intranet for others.

Lowering barriers is also motivating: an old BNF in a desk drawer will be used more often than a current version in the practice library 10 m away, or one in the health library 5 km away. Electronic libraries and the internet bring the world's literature to your desktop, but can take longer and yield fewer answers to clinical questions than paper sources. This is changing. A German study found that clinical use of online learning was about ten times that of print journals.

Summary

Barriers to workplace learning can be overcome, but a minor culture change in the medical profession is needed. This shift is already taking place in undergraduate medical education and in primary care. Clinical governance, risk management, patient empowerment, and the National Programme for IT will further advance the change.

Using clinical questions to guide workplace learning relies on the motivation of individuals, teams, and organisations. It goes hand in hand with an open attitude to clinical errors and near misses. Motivation is especially necessary to fund the instant access resources needed to provide knowledge during clinical work. Fortunately, electronic media provide a simpler, cheaper method for workplace learning than paper libraries, although there is evidence that health librarians on site are still needed to support better clinical use of these resources.

The series will be published as a book by Blackwell Publishing in spring 2006.

Competing interests: None declared.

Further reading and resources

- • Wyatt J. Use and sources of medical knowledge. Lancet 1991;338: 1368-73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • General Medical Council. A licence to practice and revalidation. London: General Medical Council, 2003

- • Mazmanian PE, Davis DA. Continuing medical education and the physician as a learner: guide to the evidence. JAMA 2002;288: 1057-60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • Lave J, Wenger E. Situated learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991

- • Ebell MH, Shaughnessy A. Information mastery: integrating continuing medical education with the information needs of clinicians. J Contin Educ Health Prof 2003;23: 53-62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • The resourceful patient website. The e-consultation: vignette. www.resourcefulpatient.org/resources/econsult.htm (accessed 30 October 2005)

- • Smith R. What clinical information do doctors need? BMJ 1996;313: 1062-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • Ely JW, Osheroff JA, Ebell MH, Chambliss ML, Vinson DC, Stevermer JJ, et al. Obstacles to answering doctors' questions about patient care with evidence: qualitative study. BMJ 2002;324: 710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • PubMed clinical queries: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query/static/clinical.html (accessed 30 October 2005)

- • Pitkin RM, Branagan MA, Burmeister LF. Accuracy of data in abstracts of published research articles. JAMA 1999;281: 1110-11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • ATTRACT: www.attract.wales.nhs.uk/index.cfm (accessed 30 October 2005)

- • Harker N, Montgomery A, Fahey T. Treating nausea and vomiting during pregnancy: case outcome. BMJ 2004;328: 503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]