Abstract

Conjugative relaxases are the proteins that initiate bacterial conjugation by a site-specific cleavage of the transferred DNA strand. In vitro, they show strand-transferase activity on single-stranded DNA, which suggests they may also be responsible for recircularization of the transferred DNA. In this work, we show that TrwC, the relaxase of plasmid R388, is fully functional in the recipient cell, as shown by complementation of an R388 trwC mutant in the recipient. TrwC transport to the recipient is also observed in the absence of DNA transfer, although it still requires the conjugative coupling protein. In addition to its role in conjugation, TrwC is able to catalyze site-specific recombination between two origin of transfer (oriT) copies. Mutations that abolish TrwC DNA strand-transferase activity also abolish oriT-specific recombination. A plasmid containing two oriT copies resident in the recipient cell undergoes recombination when a TrwC-piloted DNA is conjugatively transferred into it. Finally, we show TrwC-dependent integration of the transferred DNA into a resident oriT copy in the recipient cell. Our results indicate that a conjugative relaxase is active once in the recipient cell, where it performs the nicking and strand-transfer reactions that would be required to recircularize the transferred DNA. This TrwC site-specific integration activity in recipient cells may lead to future biotechnological applications.

Keywords: bacterial conjugation, plasmid R388, site-specific integration, strand transferase, TrwC

Bacterial conjugation is a widespread mechanism for horizontal DNA transfer among prokaryotes. Under laboratory conditions, conjugation has also been reported between bacteria and eukaryotic cells (1-3). Any DNA molecule containing a short segment called the origin of transfer (oriT) can be conjugatively transferred to a recipient cell if the rest of the conjugation machinery is provided, either in cis or in trans. The transfer apparatus can be divided into three functional modules (4-6). (i) A nucleoprotein complex known as relaxosome consists of oriT-binding proteins and their cognate DNA. These proteins include one relaxase plus one or more accessory nicking proteins; the relaxase introduces a site-specific nick at the oriT and remains covalently bound to the 5′ end of the strand that is to be transferred. (ii) A type IV secretion system (T4SS) is a multiprotein complex spanning the inner and outer membranes through which the substrate is secreted. (iii) The conjugative coupling protein (T4CP) is responsible for connecting the two other functional modules. Current models for DNA transfer through T4SS, in both conjugation and the Agrobacterium tumefaciens T-DNA transfer system (7, 8), postulate that a T4CP recruits the relaxosome to the T4SS via protein-protein interactions.

For >20 years, models for conjugative DNA transport have postulated that the relaxase catalyzes the final recircularization step of the transferred DNA because of its strand-transfer activity (8, 9). Nevertheless, it was not until recently that experimental data demonstrated that relaxases are substrates of their cognate T4SS and consequently enter the recipient cell. Transfer of the RSF1010 relaxase MobA through the Legionella Dot/Icm and plasmid RP4 T4SSs was inferred by fusing it to Cre and detecting Cre activity in the recipient, in the absence of DNA transfer (10). Also, the C-terminal domain of a conjugative relaxase (protein TraA of A. tumefaciens plasmid pATC58) mediated protein transfer to eukaryotic cells through the T4SS of Bartonella henselae (11). In the related A. tumefaciens T-DNA transfer system, the role of the relaxase homologue VirD2 as a DNA pilot protein in the plant cell is well established (12, 13); however, its role in integration of the T-DNA into the plant genome remains controversial (14).

TrwC, the relaxase of plasmid R388, is a bifunctional protein with an N-terminal relaxase domain and a C-terminal DNA helicase domain (15). The atomic structures of the relaxase domains of TrwC and TraI of plasmid F have been solved (16, 17). They share a common fold with replication initiation proteins of parvoviruses, such as tomato yellow leaf curl virus (18) and adeno-associated virus (19). Besides initiating replication, the adeno-associated virus Rep protein catalyzes integration of the viral genome into a unique site in the human genome (20). In addition to the site-specific nicking and strand-transfer activities that these proteins share, TrwC has the ability to catalyze an oriT-specific recombination reaction in the absence of conjugation (21).

In this work, we show that a conjugative relaxase is active once in the recipient cell. We detected TrwC transport in vivo by measuring its ability to complement a trwC mutation and to catalyze an oriT-specific recombination in the recipient. In addition, we show that the incoming TrwC protein can catalyze site-specific integration of the transferred DNA.

Methods

Plasmids. Plasmids used are listed in Table 1. For a detailed description, see Plasmid Construction, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site.

Table 1. Plasmids used in this work.

| Plasmid | Description | Phenotype* | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| pBBR::oriT | R388 oriT in pBBR6 | Gm | This work |

| pClomob::oriT | pSU4814::R388 oriT | Cm | This work |

| pET29c | Expression vector | Km | Novagen |

| pET29::trwABC | PABC-trwABC† in pET29c | Km | This work |

| pET29::trwAC | PABC-trwA-trwC† in pET29c | Km | This work |

| pET3a | Expression vector | Ap | Novagen |

| pET3::trwAC | PABC-trwA-trwC† in pET3a | Ap | This work |

| pET3::trwACmut | As pET3::trwAC, TrwC Y18FY26F | Ap | This work |

| pKK223-3 | Expression vector | Ap | Pharmacia |

| pKK::oriT | pKK223–3:R388 oriT | Ap | This work |

| pKK::oriT-Km | pKK::oriT plus nptII gene | Ap Km | This work |

| pKM101Δmob | pKM101 SmaI deletion derivative‡ | Ap | This work |

| pR6K::oriTW | oriV(R6K)::R388 oriT + nptII gene | Cm | This work |

| pR6K::oriTWoriTP | pR6K::oriTW plus RP4 oriT | Cm | This work |

| pRec2oriT-Ap | oriT recombination substrate | Ap Km | This work |

| pRec2oriT-Cm | oriT recombination substrate | Cm Km | This work |

| pSU711ΔoriT::aac3 | R388 derivative without oriT | GmKm | 22 |

| pSU1371 | R388 oriT in pSU19 | Cm | 23 |

| pSU1443 | R388 trwB | Tp Km | 21 |

| pSU1445 | R388 trwC | Tp Km | 21 |

| pSU1458 | R388 trwC | Tp | 21 |

| pSU1547 | pET22::trwA | Ap | 24 |

| pSU4028 | R388 trwA | Cm | 25 |

| pSU4058 | R388 T4SS in vector pHG329 | Ap | 25 |

| pSU4814 | pSU19::CloDF13mob | Cm | 26 |

Antibiotic resistance: Ap, ampicillin; Cm, chloramphenicol; Gm, gentamicin; Km, kanamycin; Tp, trimethoprim

PABC, R388 promoter for the trwA-trwB-trwC operon

This plasmid retains only the T4SS component of its transfer system

Matings. Bacterial conjugations were performed as described (27). Donor and recipient strains were D1210 (28) and DH5α (29), respectively. For integration experiments, strains CC118 λpir and S17-1 λpir (30) were used as donors in matings with strains UB1637 (31) or DH5α, respectively. These matings were carried out at 30°C to minimize prophage induction (30). Each λpir strain was also mated with DH5α λpir as a conjugation control. Triparental matings were performed by mixing derivatives of DH5α strain carrying the test plasmids (strain 1), UB1637 strain carrying the R388 mutant (strain 2), and HMS174 (32) as the recipient (strain 3). Transfer frequencies are expressed as number of transconjugants per donor cell. In triparental matings, frequencies represent number of HMS174 transconjugants per strain 2 cell. Frequencies calculated as transconjugants per strain 1 cell were very similar (data not shown).

Recombination Assays. TrwC-mediated recombination in donor cells was assayed by the loss of a DNA segment between two oriT copies, as described (21), but instead of checking for loss of kanamycin (Km) resistance, recombinants were detected by counting blue colonies after growing cells for 40 generations and plating on selective media containing 60 μg/ml X-Gal. The lacZΔM15 strain DH5α was used as the host for β-galactosidase complementation. Any colony showing at least one blue sector was considered a recombinant. Recombination in recipient cells after conjugation was measured directly by the ratio of blue transconjugants.

Integration Assays. Matings were carried out by using a λpir strain as donor and a recipient strain harboring a plasmid with or without R388 oriT. pR6K::oriTW, containing R388 oriT and an R6K replicon, was mobilized from Escherichia coli CC118 λpir containing helper plasmids for conjugative mobilization into UB1637, where the R6K replicon is not functional; pR6K::oriTWoriTP (pR6K::oriTW with RP4 oriT) was mobilized from E. coli S17-1 λpir into DH5α. Parallel matings were performed by using DH5α λpir strain as a recipient to calculate conjugation frequencies. Integration events were selected in plates supplemented with SmApCm for pR6K::oriTW matings or NxApCm for pR6K::oriTW oriTP matings. A total of 170 resistant colonies were then replicated onto Km-containing plates. DNA was extracted from 40 independent colonies for further analysis.

Results

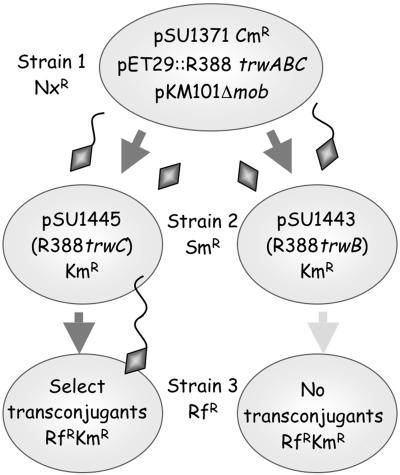

TrwC protein Is Active After Conjugative Transport to the Recipient Cell. Triparental matings were performed as illustrated in Fig. 1 to detect protein transfer via conjugation. Strain 1 carried a combination of elements of the transfer machinery. Strain 2 carried R388 transfer-deficient (Tra) mutants. The recipient (strain 3) contained no plasmids and was used to select for transconjugants of the R388 Tra mutants. The defective gene in each R388 Tra mutant in strain 2 was always present in strain 1 in a functional form on a nonmobilizable plasmid. Thus, R388 Tra mutants became transfer-proficient only if the missing protein was provided by strain 1. To avoid entry exclusion between two R388-derived transfer machineries in strains 1 and 2, the T4SS of the related IncN plasmid pKM101 was used to mobilize R388 derivatives from strain 1. The T4SSs of R388 and pKM101 are functionally interchangeable with ≈10% efficiency (33) but neither excludes transfer of the other.

Fig. 1.

Scheme of triparental matings. Bacteria are represented by ovals containing the respective plasmids. Antibiotic resistance of strains and mobilizable plasmids is indicated. Plasmid pSU1371, containing R388-oriT, is mobilized from strain 1 by nonmobilizable helper plasmids pET29:trwABC (providing R388 trwA, trwB, and trwC genes) and pKM101Δmob (providing the T4SS). TrwC is represented by a diamond, leading or not the transferred DNA (wavy line) into a recipient cell. TrwC in strain 2 is able or not to complement the R388 mutants (strain 2, left and right, respectively), leading to transconjugants or lack thereof in strain 3 (strain 3 left and right, respectively). Nx, nalidixic acid; Sm, streptomycin; Rf, rifampicin.

We tested for transfer of TrwA, TrwB, and TrwC by their ability to complement their respective mutations in strain 2. R388 trwB and trwC are transfer-deficient mutants, whereas R388 trwA retains weak transfer efficiency (Table 2, experiments 1-3). In the presence of a mobilizable plasmid carrying R388 oriT in strain 1, TrwC transport could be detected by a high conjugation frequency of the R388 trwC mutant plasmid (4-log increase; Table 2, experiment 4). Because the functional trwC gene resided on a nonmobilizable plasmid, transconjugants can be explained only if the TrwC protein itself was transferred from strain 1 to strain 2, where it complemented the R388 trwC mutation for transfer to strain 3. Thus, TrwC enters strain 2, where it is fully active. No increase in the number of transconjugants was observed when R388 trwB or trwA mutants were used (experiments 5 and 6), suggesting that neither TrwB nor TrwA can be transported into the recipient. The absence of complementation in these cases also discards other possible mechanisms to explain complementation of the R388 trwC mutant, such as conduction of the trwABC-containing plasmid to strain 2 by physical association with the mobilizable plasmid in strain 1, or transfer of the mutant R388 from strain 2 to strain 1, where it would be complemented.

Table 2. Mating experiments to check for protein transfer into recipient cells.

| Transfer elements in strain 1

|

R388 mutation in strain 2

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment | Plasmids | oriT | trwA | trwB | trwC | T4SS R388 | T4SS pKM101 | oriT-mob CloDF13 | Transfer frequency | |

| 1. trwC control | pKM101Δmob + pET29c | + | trwC (pSU1445) | <10–7 | ||||||

| 2. trwB control | pKM101Δmob + pET29c | + | trwB (pSU1443) | <10–7 | ||||||

| 3. trwA control | pKM101Δmob + pET29c | + | trwA (pSU4028) | 8 × 10—6 | ||||||

| 4. TrwC transfer with DNA transfer | pKM101Δmob + pET29:trwABC + pSU1371 | + | + | + | + | + | trwC (pSU1445) | 8 × 10—3 | ||

| 5. TrwB transfer with DNA transfer | pKM101Δmob + pET29:trwABC + pSU1371 | + | + | + | + | + | trwB (pSU1443) | 8 × 10—7 | ||

| 6. TrwA transfer with DNA transfer | pKM101Δmob + pET29:trwABC + pBBR::oriT | + | + | + | + | + | trwA (pSU4028) | 2 × 10—6 | ||

| 7. TrwC transfer w/o DNA transfer | pKM101Δmob + pET29:trwABC | + | + | + | + | trwC (pSU1445) | 5 × 10—5 | |||

| 8. TrwB transfer w/o DNA transfer | pKM101Δmob + pET29:trwABC | + | + | + | + | trwB (pSU1443) | 2 × 10—7 | |||

| 9. TrwA transfer w/o DNA transfer | pKM101Δmob + pET29:trwABC | + | + | + | + | trwA (pSU4028) | 5 × 10—6 | |||

| 10. TrwC transfer w/CloDF DNA transfer | pKM101Δmob + pET29:trwABC + pSU4814 | + | + | + | + | + | trwC (pSU1445) | 5 × 10—5 | ||

| 11. Negative control for CloDF13 | pKM101Δmob + pET29c + pSU4814 | + | + | trwC (pSU1445) | <10—7 | |||||

| 12. TrwC transfer w/o coupling protein | pKM101Δmob + pET29:trwAC | + | + | + | trwC (pSU1445) | 2 × 10—7 | ||||

| 13. TrwC transfer with entry exclusion | pSU711ΔoriT::aac3 | + | + | + | + | trwC (pSU1445) | <10—7 | |||

| 14. TrwB transfer with entry exclusion | pSU711ΔoriT::aac3 | + | + | + | + | trwB (pSU1443) | <10—7 | |||

Triparental matings were performed as explained in Methods. The first column describes the aim of each experiment. To facilitate interpretation, the elements of the conjugative machinery present in strain 1 are indicated. Frequencies represent number of transconjugants per strain 2. Figures are the mean of two to six experiments.

TrwC Is Transported by the R388 T4SS. We expect bona fide T4SS substrates to be recruited for secretion by the T4CP even in the absence of trailing DNA, as shown for other conjugative relaxases (10, 11). With this in mind, we tested for protein transfer in the absence of a mobilizable plasmid in strain 1. Results (Table 2, experiments 7-9) again show an increase in transfer frequency only for the R388 trwC mutant, indicating that TrwC was transported on its own, in the absence of DNA transfer. Nevertheless, the observed increase was ≈2 logs, significantly lower than in the presence of DNA transfer. To rule out the possibility that TrwC was being transferred passively, hitchhiking on any transported DNA as suggested for other ssDNA-binding proteins (34), the same experiment was performed in the presence of a CloDF13 mobilizable system (experiments 10 and 11). CloDF13 can use the T4SS from different transfer systems for its mobilization, providing its own coupling protein (26). No further increase in transfer frequency was observed (compare experiments 7 and 10). We also confirmed that there was no TrwC transport in the absence of a T4CP in strain 1 (i.e., no increase in the transfer frequency; compare experiments 7 and 12). This means the T4CP is required for recruitment of the protein substrate (the relaxase), whether it is alone or covalently linked to the DNA strand. Finally, we observed no TrwC transfer when there was entry exclusion between strains 1 and 2 (experiments 13 and 14), implying that Eex in strain 2 blocks both DNA and protein transfer from strain 1, i.e., the TrwC export pathway is the same as that of TrwC-DNA.

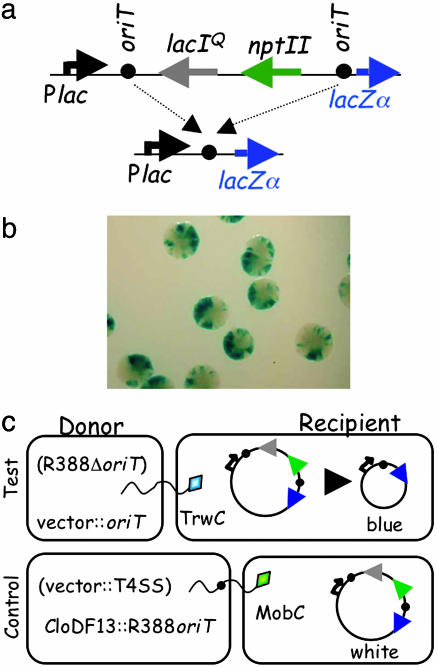

TrwC Catalyzes a Site-Specific Recombination Reaction Both in Donor and in Recipient Cells. TrwC catalyzes a site-specific recombination reaction between two directly repeated oriT copies in the absence of conjugation. This reaction was shown to depend on the presence of a functional TrwC (21). To analyze this reaction in more detail, an improved substrate plasmid was created that contained two R388 oriT copies separated by an antibiotic resistance marker and a lactose repressor gene lacIq (Fig. 2a). Upon recombination and subsequent loss of the intervening DNA, the lactose promoter comes into close proximity with the lacZα gene. Thus, in the appropriate genetic background and in an X-Gal-containing medium, recombination can be monitored by the appearance of blue bacterial colonies, simplifying the screening procedure. Fig. 2b shows a sample of the type of colonies observed when recombination is taking place, with characteristic blue sectors originating from each recombination event. Table 3 shows the recombination frequencies obtained: after 40 generations of growth, 100% of the colonies containing the substrate plasmid and TrwC were blue, whereas the background recombination level without TrwC was <1%. The recombination reaction likely reflects the strand-transferase activity of TrwC. A double mutant in the pair of active-site tyrosines (Y18F+Y26F) was shown to be completely transfer-deficient in vivo as well as strand-transfer-deficient in vitro (27). This mutant was also deficient in catalyzing site-specific recombination (Table 3), confirming that nicking and strand-transfer reactions are necessary for recombination to take place.

Fig. 2.

Assays for TrwC-mediated oriT-specific recombination. (a) Structure of the recombination cassette and the resulting product after recombination between the two oriT copies (black circles). Arrows point in the direction of transcription. Plac, lactose promoter. npt II, neomycin phosphotransferase gene conferring Km resistance. (b) DH5α (pRec2oriT-Cm) colonies transformed with pET3::trwAC and plated on CmAp X-Gal plates. Each blue sector originated from a single recombination event. (c) Assay for TrwC transfer into recipient cells carrying the recombination cassette. Helper nonmobilizable plasmids in the donor are indicated in brackets. Relaxases are shown as diamonds leading the DNA (wavy line) into recipient cells.

Table 3. oriT-specific recombination catalyzed by TrwC.

| Goal of experiment | Helper plasmid | TrwC protein | Percent blue |

|---|---|---|---|

| TrwC-mediated recombination | pET3::trwAC | Wild-type | 100.0 |

| Strand-transfer mutant | pET3::trwACmut | Y18FY26F | 0.7 |

| Negative control | pSU1547 | None | 0.7 |

Transformation of helper plasmid into DH5α (pRec2oriT-Cm). Blue colonies screened after 40 generations of growth. Data are the mean of three independent assays.

To determine whether TrwC is able to catalyze this recombination upon entering the recipient cell, matings were performed with recipient cells harboring the substrate plasmid (Fig. 2c). The plasmid mobilized from the donor cell did not carry a functional trwC gene, so only the TrwC protein, with or without the transferred DNA, was transported into the recipient cell. Results are shown in Table 4. A significant percentage of transconjugants (10%) contained the recombined substrate when TrwC was encoded in the donor cell, confirming that the protein can catalyze recombination in the recipient cell. As a negative control, a CloDF13 derivative carrying R388 oriT was mobilized by MobC to the same recipient cell in the absence of TrwC. This experiment was designed to rule out the possibility that recombinants may arise in the recipient by a TrwC-independent recombination process, such as recombination induced by the stress caused by the incoming single-stranded DNA. The recombination level in this case was 100 times lower (0.1%). A similar recombination frequency was obtained by direct transformation of the substrate plasmid into a DH5α derivative containing plasmid pSU1458 (R388 trwC; data not shown).

Table 4. oriT-specific recombination in recipient cells.

| Goal of experiment | Plasmids in donor | Plasmid features | Percent blue |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recombination in recipient (TrwC-DNA transfer) | pSU711ΔoriT + pSU1371 | R388 w/o oriT + vector::oriT | 10.0 |

| Negative control (MobC–DNA transfer) | pClomob::oriT + pSU4058 | CloDF13 w/R388 oriT + vector::T4SS (R388) | 0.1 |

Conjugation from D1210 into DH5α (pRec2oriT-Ap). Direct count of blue/white transconjugants. Data are the mean of three independent assays.

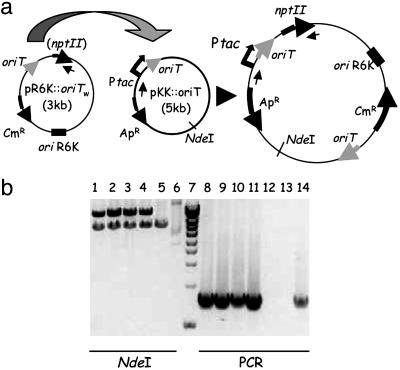

Site-Specific Integration in the Recipient. The oriT-specific recombination reaction catalyzed by TrwC was shown to occur intermolecularly (21). This prompted us to look for TrwC-mediated integration of transferred DNA into an oriT-containing plasmid resident in the recipient cell. Matings were carried out by using as donor a λpir strain carrying pR6K::oriTW (a plasmid with the R6K origin of replication and R388 oriT) and two helper plasmids for conjugative mobilization: one encoding TrwABC of R388 (pET29::trwABC) and the other providing the pKM101 T4SS (pKM101Δmob). The recipient strain, which does not allow replication of the incoming R6K-derived plasmid, harbored a plasmid with or without the R388 oriT. In addition, pR6K::oriTW carried a silent npt II gene downstream of its oriT; the expression of this gene should be activated after integration into the recipient plasmid, which carries a strong promoter upstream of its oriT.

Integration events were selected for by resistance due to the mobilizable plasmid. Because this plasmid cannot replicate in the recipient strain, resistant colonies represent integration events. Table 5 shows the results obtained in this case. A significant number of colonies were obtained only when pR6K::oriTW was mobilized into a recipient cell carrying an oriT-containing plasmid (pKK::oriT) (Table 5, compare lines 1 and 2). When these colonies were replicated onto kanamycin-containing plates, 100% were Km-resistant. However, when integration events were selected by plating cells after mating directly onto kanamycin-selective medium, no colonies grew; this observation is addressed within the Discussion. DNA from Km-resistant colonies was extracted and subjected to PCR and restriction analysis as shown in Fig. 3. Results confirm that they represent integration events of the incoming DNA into the oriT copy present in the recipient. Restriction analyses show that cointegrates coexist with the unaltered target plasmid in the recipient cell. Parallel matings into a λpir strain served to estimate pR6K::oriTW transfer frequency in this system. The frequency of integration is ≈1 in 200 transconjugants (compare lines 1 and 3 in Table 5).

Table 5. TrwC-mediated site-specific integration in recipient cells.

| Donor strain (plasmids) | Recipient strain | Frequency/donor* |

|---|---|---|

| CC118 λpir (pR6K::oriTW + pKM101Δmob + pET29::trwABC) | UB1637 (pKK::oriT) | 5.4 × 10-6 |

| CC118 λpir (pR6K::oriTW + pKM101Δmob + pET29::trwABC) | UB1637 (pKK223–3) | <1.5 × 10-8 |

| CC118 λpir (pR6K::oriTW + pKM101Δmob + pET29::trwABC) | DH5α λpir | 1.0 × 10-3 |

| S17-1 λpir (pR6K::oriTWoriTP) | DH5α (pKK::oriT) | <1.2 × 10-7 |

| S17-1 λpir (pR6K::oriTWoriTP) | DH5α (pKK223–3) | <1.4 × 10-7 |

| S17-1 λpir (pR6K::oriTWoriTP) | DH5α λpir | 3.0 × 10-2 |

Matings between donor and recipient strains were performed as explained in Methods. Selective plating was done on plates containing chloramphenicol plus ampicillin plus the antibiotic to select for the recipient strain. Frequencies are shown as number of resistant colonies per donor and are the average of three independent assays. The numbers represent integration frequencies or transfer frequencies when DH5α λpir was used as recipient

Fig. 3.

Analysis of integrants. (a) Structure of the oriT-containing plasmids present in donor (pR6K::oriTW) and recipient (pKK::oriT) cells and of the resulting cointegrant upon integration. Arrows point in the direction of transcription or DNA transfer. Small inner arrows indicate the annealing sites for the primers used in PCR reactions. (b) DNA analysis of integrants. Lanes 1-6, NdeI restriction digestion. Lane 7, 1-kb ladder (sizes in kb from the bottom of the gel: 1.0-1.5-2.0-2.5-3.0-4.0-5.0-6.0-8.0-10). Lanes 8-14, products of PCR reactions with oligonucleotides M13R (-48) and BamHindnptIIR (see Table 6, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site), which anneal 5′ to the vector Ptac promoter and 3′ to the npt II gene, respectively. Lanes 1-4 and 8-11, four different colonies obtained in the integration assays. Lanes 5 and 12, pKK::oriT. Lanes 6 and 13, pR6K::oriTW. Lane 14, positive control (plasmid pKK::oriT-Km). Other plasmids present in the matings (pKM101Δmob, pET29::trwABC, pKK223-3) were also PCR-negative (not shown).

To confirm that integration depended on TrwC, plasmid pR6K::oriTW oriTP, containing both the RP4 and R388 oriTs, was assayed for mobilization by the RP4 transfer system in the absence of R388 TrwC. Thus, pR6K::oriTW oriTP entered the recipient cell as a single strand guided by the RP4 relaxase protein and carrying an R388 oriT in its sequence. The results (Table 5, line 4) show that no resistant colonies were obtained, confirming the dependence of integration on the presence of TrwC.

Discussion

We show here that a conjugative relaxase is functional after conjugative transport into the recipient cell. Our results support the long-held assumption that termination of conjugation is accomplished by relaxase-mediated recircularization of the transferred DNA in the recipient cell. This is an important step forward in deciphering the molecular mechanism of conjugation in the recipient, about which there is little information.

Evidence for TrwC transfer and function in the recipient is provided by a range of genetic experiments. First, donors expressing TrwC from a nonmobilizable plasmid transport TrwC protein into a strain containing a trwC-deficient R388, rendering it transfer-proficient by the incoming protein. Second, a plasmid with two oriT copies resident in the recipient strain undergoes TrwC-dependent oriT-oriT recombination when TrwC protein is transferred from a donor carrying a nonmobilizable trwC gene. Finally, we demonstrate TrwC-dependent integration of the transferred DNA into a recipient-based oriT. Exhaustive negative controls in all cases ensure that these results can be explained only by T4SS-dependent transfer of the TrwC protein.

Triparental matings as diagrammed in Fig. 1 were performed to detect conjugative protein transfer. Results shown in Table 2 make evident that a trwC mutation in strain 2 can be complemented, whereas neither trwA nor trwB mutations can be complemented. Thus, TrwC protein is transferred into strain 2, where it complements the trwC mutant pSU1445. Although the results support our contention that TrwA and TrwB are not transported during conjugation, we cannot rule out the possibility that these proteins are transferred but are not functional in the recipient.

TrwC is a DNA-binding protein, so the observed protein transport could be the consequence of DNA transfer. Passive protein transport concomitant with DNA transfer was previously suggested for RecA transport during conjugation (34). In contrast, complementation of the trwC-deficient plasmid in strain 2 was observed in the presence and absence of DNA transfer from strain 1 (Table 2). Hence, TrwC protein can be transferred during conjugation on its own, as was shown indirectly for relaxase MobA of RSF1010 (10) and the relaxase homologue VirD2 of A. tumefaciens (12). This result underscores the concept that T4SSs are protein secretion machines, and that DNA is dragged along by the relaxase substrate. We observed that the complementation level of the R388 trwC mutant was ≈100 times lower in the absence of conjugative DNA transfer, but again this was not due to a “hitchhiking” effect of the protein traveling passively on any transferred DNA, because conjugative transfer of a coresident CloDF13 plasmid did not contribute to TrwC transport (Table 2). The higher level of complementation in the presence of mobilizable plasmids containing R388 oriT could reflect either that a TrwC-DNA complex is a better substrate for the T4SS, or that the TrwC-DNA complex is more stable, and so the half-life of the relaxase in the recipient is increased.

That TrwC is not transferred when there is no TrwB in donor cells indicates that the T4CP is needed to recruit the substrate, the relaxase, independently of the presence of a trailing DNA. This supports the current view of T4CPs as protein substrate recruiters for T4SS (5, 6). The potential active role of T4CPs on DNA transport may have been acquired independently of their function as substrate recruiters. Alternatively, their role as DNA motors could have been lost in T4SSs that do not secrete DNA, keeping the T4CP for substrate recruitment only. There is increasing evidence that ancestral T4SSs were conjugation systems, and relaxases could be the ancestors of T4SS protein substrates in general (11).

The ability of TrwC to catalyze an oriT-specific recombination reaction in the absence of conjugation was reported a decade ago (21). There have been scarce reports that relate conjugative relaxases to site-specific recombination reactions (21, 35-37). How these proteins accomplish a reaction characteristic of the family of site-specific recombinases is still to be determined. The ability to perform this type of events must rely on some common activity of relaxases, the obvious candidate being their strand-transfer ability. We show here that this activity of TrwC is indeed responsible for the recombination reaction, because a mutant in the catalytic Tyr residues loses this function (Table 3). Most interestingly, we also demonstrate that TrwC catalyzes oriT-specific recombination upon entering the recipient cell. Donor cells carrying nonmobilizable trwC genes were mated with recipient cells containing the substrate plasmids for recombination, and a 100-fold increase in the number of transconjugants containing the recombined plasmid was observed when TrwC protein enters the recipient (Table 4). Thus, TrwC can act as a site-specific recombinase in a recipient cell when introduced in vivo by conjugation.

The possibility that a conjugative relaxase transported to the recipient cell can undergo strand-transfer reactions is essential to understanding the mechanism of termination of conjugation. In the case of relaxases containing a single active-site Tyr, as is the case for RP4 TraI, termination requires two relaxase molecules (38), and this can occur only if additional relaxase molecules can be transported to the recipient, where they engage in the termination strand-transfer reaction. The observed relaxase transfer in the absence of trailing DNA may reflect the necessary transport of additional relaxase molecules to the recipient cell.

The ability of TrwC to catalyze site-specific integration of the transferred DNA strand into the recipient genome was also tested. We performed matings between a λpir donor and an oriT-containing recipient strain; transferred DNA cannot replicate in the recipient strain, so transconjugants were produced only by integration of the incoming DNA into the oriT copy present in the recipient. We observed integration events with a frequency only 200 times lower than conjugation events (Table 5). The structure of integrants was checked by DNA analysis (Fig. 3). The dependence on TrwC was confirmed by mobilization of a similar plasmid by the RP4 relaxase, in which case no integration events were observed (Table 4). Upon integration, a silent npt II gene on the incoming DNA was placed downstream of a tac promoter. Interestingly, Km resistance was detected only after replica-plating of the colonies obtained by Cm selection, indicating that integration does not occur immediately upon DNA transfer. The result also suggests that DNA needs to be converted to its double-stranded form (which allows cat transcription) before integration.

The above results make TrwC potentially useful for biotechnological and biomedical purposes. TrwC and any oriT-containing DNA can be conjugatively transferred into a recipient cell. Bacteria conjugate to a wide variety of recipient cells, including mammalian cells (3), and introduction of DNA by bacterial conjugation may provide a decisive advantage over existing viral vectors for gene therapy, because it imposes no size limit on the transferred DNA. Once in the recipient, TrwC can catalyze integration of the trailing DNA into a resident oriT sequence. Future work includes determining the minimal DNA target sequence for TrwC-mediated integration. By analogy to adeno-associated virus-Rep, we expect it to be similar to the region required for nicking and strand transfer in the donor, which is 18 nucleotides in length (ref. 17 and M. Lucas, personal communication). A database search for sequences resembling the R388 nic region shows several putative target DNA sequences in the human genome. Our own results show that TrwC efficiently binds and catalyzes strand-transfer reactions on oligonucleotides containing these sequences (data not shown). Current approaches to accomplish targeted modification of mammalian genomes by using classical recombinases such as Cre, Flp, or phage ΦC31 integrase require that the target site be first inserted into the recipient genome (39); in contrast, DNA sequences resembling nic sites could represent naturally existing target sites for relaxase-mediated integration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Maria Pilar Garcillán-Barcia for helpful discussions. Work in our laboratories is supported by Grants BIO2002-00063 and BMC2002-00379 (Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología, Spain) to M.L. and F.C., respectively. C.E.C. was a recipient of a Formación de Personal Investigador fellowship from the Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia (Spain).

Author contributions: O.D. and M.L. designed research; O.D., C.E.C., C.M., and M.L. performed research; O.D., C.E.C., C.M., F.d.l.C., and M.L. analyzed data; and O.D., F.d.l.C., and M.L. wrote the paper.

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: oriT, origin of transfer; T4SS, type IV secretion system; T4CP, conjugative coupling protein; Km, kanamycin; Ap, ampicillin; Cm, chloramphenicol.

References

- 1.Buchanan-Wollaston, V., Passiatore, J. E. & Cannon, F. (1987) Nature 328, 172-175. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heinemann, J. A. & Sprague, G. F., Jr. (1989) Nature 340, 205-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waters, V. L. (2001) Nat. Genet. 29, 375-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Llosa, M. & de la Cruz, F. (2005) Res. Microbiol. 156, 1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christie, P. J. (2004) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1694, 219-234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schroder, G. & Lanka, E. (2005) Plasmid 54, 1-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Atmakuri, K., Cascales, E. & Christie, P. J. (2004) Mol. Microbiol. 54, 1199-1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Llosa, M., Gomis-Rüth, F.-X., Coll, M. & de la Cruz, F. (2002) Mol. Microbiol. 45, 1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Willetts, N. & Wilkins, B. (1984) Microbiol. Rev. 48, 24-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luo, Z. Q. & Isberg, R. R. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 841-846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schulein, R., Guye, P., Rhomberg, T. A., Schmid, M. C., Schroder, G., Vergunst, A. C., Carena, I. & Dehio, C. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 856-861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vergunst, A. C., van Lier, M. C., den Dulk-Ras, A., Grosse Stuve, T. A., Ouwehand, A. & Hooykaas, P. J. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 832-837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Howard, E. A., Zupan, J. R., Citovsky, V. & Zambryski, P. C. (1992) Cell 68, 109-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tzfira, T., Li, J., Lacroix, B. & Citovsky, V. (2004) Trends Genet. 20, 375-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Llosa, M., Grandoso, G., Hernando, M. A. & de la Cruz, F. (1996) J. Mol. Biol. 264, 56-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Datta, S., Larkin, C. & Schildbach, J. F. (2003) Structure (Cambridge, U.K.) 11, 1369-1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guasch, A., Lucas, M., Moncalián, G., Cabezas, M., Pérez-Luque, R., Gomis-Rüth, F. X., De La Cruz, F. & Coll, M. (2003) Nat. Struct. Biol. 10, 1002-1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Campos-Olivas, R., Louis, J. M., Clerot, D., Gronenborn, B. & Gronenborn, A. M. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 10310-10315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hickman, A. B., Ronning, D. R., Kotin, R. M. & Dyda, F. (2002) Mol. Cell. 10, 327-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith, R. H. & Kotin, R. M. (2002) in Mobile DNA II, eds. Craig, N. L., Craigie, R., Gelert, M. & Lambowitz, A. M. (Am. Soc. Microbiol., Washington, DC), pp. 905-923.

- 21.Llosa, M., Bolland, S., Grandoso, G. & de la Cruz, F. (1994) J. Bacteriol. 176, 3210-3217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Demarre, G., Guerout, A. M., Matsumoto-Mashimo, C., Rowe-Magnus, D. A., Marliere, P. & Mazel, D. (2005) Res. Microbiol. 156, 245-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Llosa, M., Bolland, S. & de la Cruz, F. (1991) Mol. Gen. Genet. 226, 473-483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moncalian, G. & de la Cruz, F. (2004) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1701, 15-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bolland, S., Llosa, M., Avila, P. & de la Cruz, F. (1990) J. Bacteriol. 172, 5795-5802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Núñez, B. & de la Cruz, F. (2001) Mol. Microbiol. 39, 1088-1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grandoso, G., Avila, P., Cayón, A., Hernando, M. A., Llosa, M. & de la Cruz, F. (2000) J. Mol. Biol. 295, 1163-1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sadler, J. R., Tecklenburg, M. & Betz, J. L. (1980) Gene 8, 279-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grant, S. G., Jessee, J., Bloom, F. R. & Hanahan, D. (1990) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87, 4645-4649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Lorenzo, V. & Timmis, K. N. (1994) Methods Enzymol. 235, 386-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de la Cruz, F. & Grinsted, J. (1982) J. Bacteriol. 151, 222-228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Campbell, J. L., Richardson, C. C. & Studier, F. W. (1978) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 75, 2276-2280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Llosa, M., Zunzunegui, S. & de la Cruz, F. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 10465-10470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heinemann, J. A. (1999) Plasmid 41, 240-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Francia, M. V. & Clewell, D. B. (2002) J. Bacteriol. 184, 5187-5193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gennaro, M. L., Kornblum, J. & Novick, R. P. (1987) J. Bacteriol. 169, 2601-2610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Furuya, N. & Komano, T. (2003) J. Bacteriol. 185, 3871-3877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pansegrau, W. & Lanka, E. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 13068-13076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sorrell, D. A. & Kolb, A. F. (2005) Biotechnol. Adv. 23, 431-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.