Abstract

The role of polypeptide collapse and formation of intermediates in protein folding is still under debate. Miniproteins, small globular peptide structures, serve as ideal model systems to study the basic principles that govern folding. Experimental investigations of folding dynamics of such small systems, however, turn out to be challenging, because requirements for high temporal and spatial resolution have to be met simultaneously. Here, we demonstrate how selective quenching of an extrinsic fluorescent label by the amino acid tryptophan (Trp) can be used to probe folding dynamics of Trp-cage (TC), the smallest protein known to date. Using fluorescence correlation spectroscopy, we monitor folding transitions as well as conformational flexibility in the denatured state of the 20-residue protein under thermodynamic equilibrium conditions with nanosecond time resolution. Besides microsecond folding kinetics, we reveal hierarchical folding of TC, hidden to previous experimental studies. We show that specific collapse of the peptide to a molten globule-like intermediate enhances folding efficiency considerably. A single point mutation destabilizes the intermediate, switching the protein to two-state folding behavior and slowing down the folding process. Our results underscore the importance of preformed structure in the denatured state for folding of even the smallest globular structures. A unique method emerges for monitoring conformational dynamics and ultrafast folding events of polypeptides at the nanometer scale.

Keywords: fluorescence correlation spectroscopy, photoinduced electron transfer, protein folding

Identifying the mechanisms by which an unfolded protein chain folds into its unique three-dimensional structure continues to be one of the central issues in molecular biology (1). The role of polypeptide collapse and formation of intermediates for efficient folding is still under debate (2–4). It has been proposed that rapid formation of compact intermediates with native-like topology limits the conformational search and directs the polypeptide chain along a preferred route toward the native conformation (3). In contrast, for small and structurally simple proteins, it is commonly found that only two populations of molecules are observable at equilibrium, folded and unfolded, suggesting a simple two-state mechanism (4). The smallest folding species are miniproteins (i.e., peptides that exhibit secondary and tertiary structural elements). Folding kinetics of miniproteins are extraordinarily fast [i.e., in the microsecond time domain (5)]. Small size and ultrafast folding kinetics allow mechanisms of protein folding to be elucidated by theoretical means. With increasing computing power, calculation of complete unfolding trajectories of microsecond length has become possible (6). From a theoretical point of view, it has been proposed that true two-state protein folding is fundamentally impossible (7). Simulations of folding pathways at atomic resolution reveal that native tertiary interactions evolve from varying degrees of residual structure in the denatured state. Experimentally, however, folding kinetics of miniproteins are commonly described by simple two-state transitions (5, 8). Often, experimental characterization of the denatured state in protein folding remains elusive. Investigations of early events in protein folding are challenging, because requirements for high temporal and spatial resolution have to be met simultaneously. Spectroscopic probes and techniques are required, which can monitor ultrafast folding kinetics as well as characterize structure and conformational dynamics in the denatured state under various experimental conditions.

Today, the recently designed miniprotein Trp-cage (TC) represents the smallest protein (9). The 20-residue peptide has been generated by truncation and mutation of the poorly folded 39-residue peptide exendin-4 from Gila monster saliva. The solution structure of TC features a hydrophobic core, built by tight packing of a short proline-rich carboxyl-terminal domain to an amino-terminal α-helical segment (9). A single Trp residue is buried in the core, well shielded from solvent exposure (Fig. 1A). Folding of TC has been characterized by NMR and CD and has been proposed to follow a highly cooperative two-state transition (9). Using Trp fluorescence in combination with a temperature-jump apparatus, Qui et al. (10) demonstrated that TC exhibits two-state folding behavior with a characteristic folding time of 4 μs (10), making it one of the fastest folding miniproteins known to date (5).

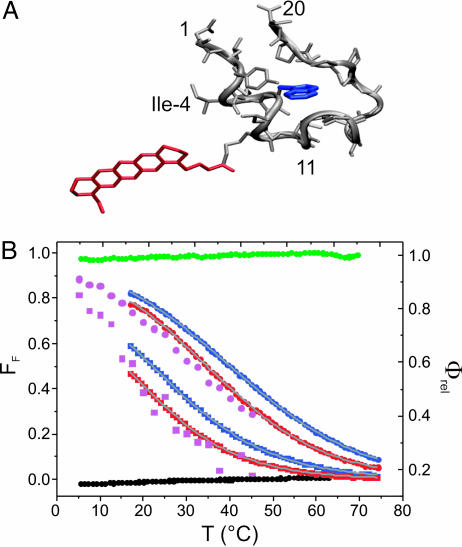

Fig. 1.

Thermal unfolding of modified TC peptides monitored by fluorescence intensity measurements. (A) Engineered NMR structure (Protein Data Bank ID code 1L2Y) of fluorescently modified TC*. The fluorophore MR121 labeled to the ε-amino group of lysine (K8) and the Trp residue (W6) are shown in red and blue, respectively. (B) Relative quantum yields (Φrel) and corresponding folded fractions (FF) measured from the MR121 fluorescence of labeled (red) and the Trp fluorescence of unlabeled (blue) TC (circles). Data recorded from the mutant TC(I4G) are shown as squares. Gray lines are sigmoidal data fits. Note that, for better comparison, Φrel for unlabeled TC is shown as 1 – ΦTrp (ΦTrp being a measure of the relative Trp fluorescence), because, in contrast to MR121 in TC*, the fluorescence intensity of Trp in TC increases upon unfolding. Φrel values measured from MR121 in labeled control peptides TC*F1 and TC*F2(W6F) are shown as black and green circles, respectively. Melting curves for TC* (circles) and TC*(I4G) (squares), calculated from normalized FCS amplitudes (see Materials and Methods), are shown in magenta.

Here, we introduce fluorescence quenching of an extrinsic fluorophore by the amino acid tryptophan (Trp) as a unique method to probe ultrafast folding dynamics of proteins. Using fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS), we monitor folding kinetics as well as conformational flexibility in the denatured state of TC under thermodynamic equilibrium conditions with nanosecond time resolution. The method is similar to the triplet state quenching method introduced recently to measure folding/unfolding kinetics of the 35-residue headpiece subdomain of the protein villin (11).

By monitoring folding dynamics of TC under various experimental conditions, we reveal residual structure in the denatured state of the miniprotein, hidden to previous experimental studies. Hierarchical folding of TC observed in our experiments confirms predictions from theoretical work and implies that specific collapse of the peptide to a molten globule-like intermediate is responsible for efficient folding. This finding is corroborated by the fact that a single point mutation destabilizes the intermediate, switching the protein to true two-state folding behavior with reduced folding efficiency. The presented results underscore the importance of preformed structure in the denatured state for fast folding, even in the smallest globular structures. Thus, the established technique lends itself as a method for monitoring ultrafast folding kinetics as well as for characterizing structure and conformational dynamics in the denatured state of polypeptides with excellent temporal and spatial resolution.

Materials and Methods

Fluorescence Modification of Peptides. The amino-reactive oxazine fluorophore MR121 was provided by K. H. Drexhage (University of Siegen, Siegen, Germany). Synthetic peptides with the following sequences (with mutations underscored) were purchased from Thermo (Ulm, Germany): TC, NLYIQWLKDGGPSSGRPPPS; TCF1, NLYIQWLKDGG; TCF2(W6F), NLYIQFLKDGGP; TC(I4G), NLYGQWLKDGGPSSGRPPPS; TCF1(I4G), NLYGQWLKDGG; p53–1, SQETFSDLWKLLPEN. (TCF1 is TC residues 1–11, and TCF2 is TC residues 1–12.) ε-Amino modification of lysine residues (K) in the peptide sequences was performed by classical N-hydroxysuccinimidylester chemistry. Chemicals were purchased from Sigma. Fifty micrograms of the dye was dissolved in 5 μl of dimethylformamide (DMF). Five hundred micrograms of the peptide was dissolved in 50 μl of DMF. Dye and peptide solution were mixed and incubated for 3 h at room temperature in the dark after the addition of 1 μl of diisopropylethylamine. Dye–peptide conjugates were purified by RP-HPLC (Hypersil-ODS column, Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA) using a linear gradient of 0–75% acetonitrile in 0.1 M aqueous triethylammonium acetate.

Steady-State Fluorescence and CD Measurements. Steady-state fluorescence intensities of MR121 conjugates (absorption maxima λabs = 664–666 nm and emission maxima λem = 677–683 nm) and Trp fluorescence of unlabeled peptides (λabs = 280 nm and λem = 356 nm) were recorded by using a standard fluorescence spectrometer (Cary Eclipse, Varian) equipped with a sample temperature control unit. Samples were diluted in PBS solution (pH 7.4) containing 0.05% Tween 20 and 0.3 mg/ml BSA. Measurements under acidic conditions were performed in 50 mM acetic acid (pH 3.0) containing 0.05% Tween20 and 0.3 mg/ml BSA. Sample concentrations were kept strictly <10–6 M to prevent reabsorption and reemission effects. Relative fluorescence quantum yields, Φrel, were determined with respect to the free dye. Experimental fluorescence intensities of dye–peptide conjugates (MR121 fluorescence) and unlabeled peptides (Trp fluorescence) were normalized to the fluorescence intensity of the control peptide TC*F2(W6F) and TCF1, respectively. Far-UV CD measurements were performed on a J810 spectropolarimeter (Jasco, Easton, MD). Sample concentration was 0.2 mg/ml peptide in 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.3).

FCS Experiments. FCS experiments were performed on a confocal fluorescence microscope that essentially consists of a standard inverse fluorescence microscope equipped with a HeNe laser, emitting at 632.8 nm, as excitation source. The collimated laser beam was coupled into an oil-immersion objective (×63, numerical aperture of 1.4, Zeiss) by a dichroic beam splitter (645DLRP, Omega Optical, Brattleboro, VT). The average laser power was adjusted to be 1 mW before entering the aperture of the microscope (corresponding to 800 μW at the sample). The fluorescence signal was collected by the same objective, filtered by a band-pass filter (700RDF75, Omega Optical), and imaged onto the active area of two single-photon avalanche photodiodes (APDs) (AQR-14, EG & G, Vaudreuil, QC, Canada), sharing the fluorescence signal by a cubic nonpolarizing beamsplitter (Linos, Göttingen, Germany). The signals of the APDs were recorded in the cross-correlation mode (5 min for each measurement) by using a digital real-time correlator device (ALV-6010, ALV, Langen, Germany). The application of two APDs in the cross-correlation mode circumvents dead-time and after-pulsing effects, yielding a time resolution of 6.25 ns. Fluorescently modified peptides were diluted in buffered solution to a final concentration of 5 × 10–10 M. Samples were transferred onto a microscope slide and covered by a coverslip. Sample temperature was controlled by a custom-built objective heater (5–60°C). FCS measurements under denaturing conditions [guanidinium chloride (GdmCl)] were recorded at 10°C.

The recorded autocorrelation functions were fitted by using a FCS model containing a single diffusion term and two independent relaxation kinetics for intrinsic fluorescence quenching as follows:

|

[1] |

Here, t is the lag time of the correlation function, N is the average number of molecules in the detection focus, τD is the experimental diffusion time, and τ1 and τ2 are two independent fluorescence relaxation kinetics with corresponding amplitudes K1 and K2. FCS data were normalized to N. In the following notation, K1 and τ1 denote the microsecond relaxation kinetics, whereas K2 and τ2 denote the nanosecond kinetics, whenever two kinetic processes appear in FCS data.

For diffusing molecules that follow a single kinetic process and switch between two states, one being fluorescent (on) and the other being nonfluorescent (off), on a time scale faster than the diffusion time, an analytical expression for the correlation function can be derived as follows:

|

[2] |

In the applied two-state kinetic model, K represents the experimental equilibrium constant for the interconversion between the on and off state, where K = k+/k–, with k+ being the population rate of the off state and k– being the population rate of the on state. The experimental relaxation time is τ = 1/(k+ + k–). Besides evaluation of folding and unfolding kinetics, the fraction of folded species, FF = k–/(k+ + k–) = 1/(K + 1), can be calculated.

In the case of TC*, where K2 is negligible, FF can be directly extracted from normalized K1 values in the corresponding temperature range. FF values of TC*(I4G) were calculated from the sum of normalized amplitudes (K1 and K2). For the calculation of the temperature-dependent unfolded random-coil fractions (FU) of TC* and TC*(I4G), K2 values were normalized to the temperature dependence of K2 values of the corresponding fragments TC*F1 and TC*F1(I4G).

Results and Discussion

Thermal Unfolding of TC Monitored by Fluorescence Quenching. To investigate folding of TC, we modified the peptide with the fluorophore MR121, an oxazine dye that tends to form nonfluorescent complexes with the amino acid Trp in water (12, 13). Bimolecular complexes between MR121 and Trp in water exhibit stacked face-to-face interaction geometries. Upon excitation of MR121, efficient fluorescence-quenching electron transfer reactions from Trp to the fluorophore can take place at van der Waals contact (13). Site-specific labeling of TC with MR121 at the lysine residue (K8) in the amino-terminal segment yielded the conjugate TC* (Fig. 1 A). Steady-state fluorescence intensities measured from TC* show fluorescence quenching of MR121 upon thermal unfolding (Fig. 1B). In the folded state, MR121 is shielded from fluorescence quenching interactions with Trp (W6) that is “caged” in the hydrophobic core of TC*, whereas in the denatured state, W6 is solvent-exposed and accessible to MR121, giving rise to fluorescence quenching interactions. The thermal melting profile of TC* shown in Fig. 1B compares well with that obtained from the intrinsic Trp fluorescence of TC (10). The melting temperature (Tm) of 35°C for TC* is lower compared with 39°C for TC due to a slight destabilization of the fold upon fluorescence modification. In accordance with the proposed model, truncation of TC* [i.e., removal of the carboxyl-terminal cap (residues 12–20)], leads to strong fluorescence quenching being nearly independent of temperature (TC*F1, Fig. 1B). The relative fluorescence quantum yield (Φrel) of the fragment TC*F1 of 0.16 at 20°C is similar to that of TC* in the unfolded state (Fig. 1B). In contrast, mutation of Trp in TC*F1 by phenylalanine (W6F) leads to complete recovery of fluorescence [TC*F2(W6F), Fig. 1B], confirming that fluorescence quenching of MR121 in TC* is solely caused by interactions with Trp.

Folding Dynamics Probed by FCS. To monitor folding kinetics of TC*, reflected in on/off fluctuations of fluorescence, we applied FCS using confocal fluorescence microscopy. FCS analyzes temporal fluorescence fluctuations from highly diluted samples (at nanomolar concentrations), probing molecules diffusing through a confined detection volume (typically ≈1 fl with 1–20 molecules) by Brownian motion (14, 15). Characteristic time scales of molecular processes that result in fluctuating fluorescence emission can be measured under thermodynamic equilibrium conditions with nanosecond time resolution (16–18).

Selective fluorescence quenching of MR121 by Trp arises from photoinduced electron transfer reactions from Trp to the excited fluorophore at van der Waals contact (13, 19), a process that is much faster than the temporal resolution of our FCS setup (6.25 ns). Dynamic quenching of fluorophores by electron donors or acceptors results in a decrease in the measured fluorescence lifetime (20), but quenching of MR121 by Trp is dominated by the formation of nonfluorescent complexes where electron transfer occurs on femtosecond to picosecond time scales (21). Complex formation is confirmed by an almost unchanged fluorescence lifetime measured in intermolecular quenching experiments of MR121 with Trp in aqueous solvents (12). Furthermore, under moderate excitation conditions, no photophysical process, such as intersystem crossing, is apparent in the submillisecond time domain as demonstrated by FCS data recorded from the control peptide TC*F2(W6F) lacking a Trp residue (Fig. 2A).

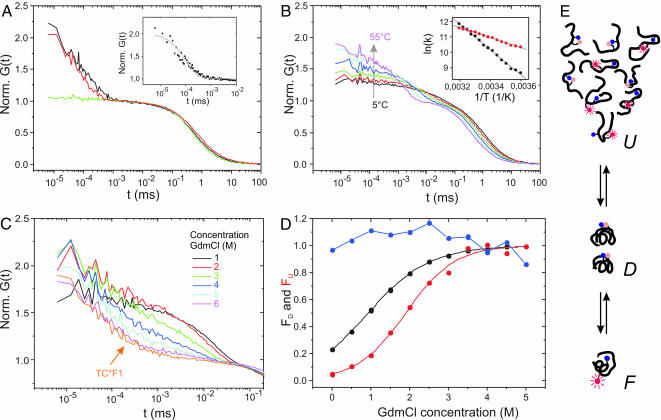

Fig. 2.

Folding of TC* monitored by FCS. (A) Normalized autocorrelation function [Norm. G(t)] measured from the TC fragments TC*F1 (black), TC*F2(W6F) (green), and the unstructured control peptide p53*1 (red) at 20°C. (Inset) Nanosecond relaxation kinetics of TC*F1 and corresponding exponential fit. (B) Temperature-dependent autocorrelation functions of TC* measured in 5-K temperature intervals (only samples spaced by 10 K are shown; 5–55°C). (Inset) Folding (red) and unfolding (black) rates, k, calculated from the relaxation times and corresponding normalized amplitudes, follow Arrhenius folding behavior at moderate temperatures. Gray lines are linear data fits. (C) Autocorrelation functions of fast relaxation kinetics of TC* measured at various GdmCl concentrations. Additionally, corresponding data recorded from the fragment TC*F1 at 6 M GdmCl are shown. (D) Fraction of the denatured (FD) and the unfolded (FU) ensemble of TC measured as a function of the GdmCl concentration, monitored by Trp fluorescence of TC (black) and by the amplitude of the nanosecond relaxation kinetics (K2) of TC* (red). The amplitude K2 of the fragment TC*F1 measured as a function of the GdmCl concentration is shown in blue. (E) Illustration of the TC folding ensemble as revealed by FCS. The unfolded state (U) is characterized by extended random-coil conformations giving rise to fluorescence quenching, with fluorophore (red)–Trp (blue) interaction kinetics on nanosecond time scales. Under mildly denaturing conditions, the denatured ensemble (D) is dominated by a collapsed intermediate with Trp being solvent-exposed. The labeled fluorophore is within a short interaction distance to Trp, leading to efficient fluorescence quenching with interaction kinetics beyond the time window of FCS. In the folded state (F), the fluorophore is well shielded from quenching interactions with Trp, being buried in the hydrophobic pocket.

FCS curves recorded from TC* (Fig. 2B) exhibit marked, temperature-dependent relaxation kinetics on microsecond time scales, which could be well fitted by using Eq. 1. Data are dominated by a single exponential relaxation process. Because the folded and denatured states of TC* correspond to the fluorescent and fluorescence-quenched states, respectively, single exponential relaxation kinetics reveal a two-state folding transition. The folded fractions calculated from normalized amplitudes (K1) compare well with steady-state fluorescence intensities (Fig. 1B). Folding rates calculated from K1 values and corresponding microsecond relaxation times (τ1) follow Arrhenius behavior at moderate temperatures (5–45°C) (Fig. 2B Inset). The Arrhenius activation energy for folding (Ef = (27 ± 1) kJ/mol) is in excellent agreement with that derived from temperature-jump experiments (Ef = (27 ± 1) kJ/mol) (10). The somewhat lower activation energy for unfolding (Eu = (69 ± 1) kJ/mol versus Eu = (76 ± 5) kJ/mol in T-jump experiments) is consistent with a slight destabilization of TC due to fluorescence modification, as already indicated by the shift in melting temperature. We extract a folding time of τf = 16 ± 1 μs at 22.5°C, somewhat higher compared with τf = 4 μs (10), previously reported by Qui et al. (10). The deviation can be explained by complex formation of fluorophore and Trp in the denatured state of the protein slowing down incorporation of Trp into the hydrophobic core of the fold.

In contrast to TC*, FCS data recorded from the fragment TC*F1 show marked nanosecond fluorescence relaxation kinetics. These fluctuations are identical to those observed for a 15-residue control peptide derived from the sequence of human p53 (Fig. 2 A). The lysine-modified p53 peptide (p53*1) contains a single Trp residue and was labeled with positions of MR121 and Trp similar to those in TC*F1 (see Materials and Methods for sequences). Far-UV CD spectra recorded from the unlabeled fragment TCF1 (data not shown) as well as previous studies on the p53 peptide (22) demonstrate the lack of any residual structure in both peptides. We conclude that the observed relaxation for TC*F1 reflects intramolecular interaction kinetics of MR121 and Trp within an unstructured peptide. These interaction kinetics are mediated by peptide random-chain diffusion and the manifold intramolecular interaction possibilities of the fluorophore attached to the peptide. Amino acid contact formation kinetics in unstructured peptides are thought to represent elementary steps in protein folding and have been investigated extensively by using various spectroscopic techniques (19, 23–25).

A careful look at the submicrosecond FCS data indicates fundamental experimental insights into the folding mechanism of TC. For a protein following a true two-state transition, the denatured state would be characterized by an ensemble of random-coil conformations. FCS curves of TC* measured at moderate temperatures (5–45°C) lack the random-chain signature as seen for the fragment TC*F1. Apparently, TC* in its thermally unfolded state features considerably reduced conformational flexibility. Here, both solvent-exposed Trp and fluorophore are in a conformationally constrained microenvironment within a short interaction distance, leading to efficient fluorescence quenching with interaction kinetics beyond the time window of FCS.

We conclude that the amino-terminal domain of TC (residues 1–11) collapses to a conformationally confined intermediate before the formation of native tertiary interactions. Because the amino-terminal fragment itself (TC*F1) shows random-coil behavior, collapse is assisted by nonnative tertiary interactions with the proline-rich carboxyl-terminal domain (residues 12–20). The observed intermediate is characterized by solvent exposure of Trp, which is evidenced by fluorescence quenching of the attached fluorophore within this state, a process that requires van der Waals contact with the Trp side chain (13). Thus, the rate-limiting step of folding represents incorporation of Trp into a preformed hydrophobic core. Our data are in accordance with recent all-atom molecular dynamics simulations of TC, which predict that the extended, unfolded miniprotein collapses to a denatured state characterized by fluctuating secondary structure and native-like topology (26–29). However, it remains unclear whether collapse precedes or occurs concomitantly with formation of α-helical secondary structure. The match of Trp fluorescence and CD melting data has been proposed to demonstrate that breaking of the hydrophobic core of TC is accompanied by melting of the helix (10), supporting true two-state folding. But this correlation can be deceptive, because the α-helical CD signature at 222 nm is convoluted with a strong contribution from the Trp side chain (30). Very recently, indications for residual helical structure in the denatured state of TC have been reported by using UV-resonance Raman spectroscopy (31), suggesting the early formation of helical structure.

Folding Dynamics Under Chemical Denaturation. For a closer characterization of the observed intermediate, we investigated folding of TC* under chemical denaturation (GdmCl) (Fig. 2C). Autocorrelation functions of TC* are characterized by increasing nanosecond and decreasing microsecond relaxation kinetics with increasing GdmCl concentration (τ1 = 15, 6, and 3 μs at 1, 3, and 5 M GdmCl, respectively). At 6 M GdmCl, TC* exhibits exclusively nanosecond relaxation kinetics, matching those measured from the amino-terminal fragment TC*F1. Because for the unstructured fragment TC*F1 the amplitude of the nanosecond relaxation kinetics (K2) is nearly independent of GdmCl concentration, K2 values measured from TC* can be directly used to monitor the population of the unfolded random-coil ensemble (FU). K2 of TC* as a function of GdmCl concentration (Fig. 2D) exhibits a sigmoidal transition with a midpoint at ≈2 M GdmCl, clearly above that obtained from Trp fluorescence intensity measurements (≈1 M GdmCl). While K2 probes the unfolded random-coil ensemble of TC, Trp fluorescence reports on packing of the Trp side chain into the hydrophobic core. Thus, in contrast to thermal folding studies, FCS reveals unfolding of the intermediate in a strongly denaturing environment. High thermal stability on one hand and complete unfolding under strongly denaturing conditions on the other hand suggests a molten globule-like intermediate (32, 33). The folding transitions of TC as revealed by FCS are depicted schematically in Fig. 2E.

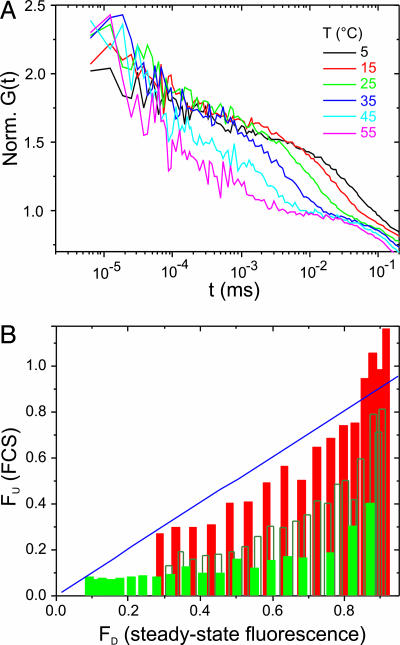

Folding Dynamics of Mutant TC. To investigate the role of the observed intermediate for folding efficiency, we introduced a helix-breaking point mutation in the amino-terminal segment of TC by replacing isoleucine (I4) by a glycine residue (G). I4 is not part of the hydrophobic cluster built by Trp and tyrosine, nor is it involved in tertiary interactions (Fig. 1 A). Thus, the I4G mutation serves as a good probe to assess the importance of the helix-forming propensity of the amino-terminal domain for folding. Fluorescence intensity measurements of the labeled peptide [TC*(I4G)] reveal a substantial decrease in thermal folding stability (Tm = 15°C compared with 35°C for TC*; Fig. 1B). In contrast to TC*, autocorrelation functions of the mutant TC*(I4G) reveal marked temperature-dependent nanosecond relaxation kinetics besides microsecond folding kinetics, indicating the presence of a substantial random-coil population (U) in the denatured-state ensemble (Fig. 3A). Fig. 3B shows the correlation of the thermally unfolded fraction FU, monitored by K2, with the thermally denatured fraction FD, monitored by steady-state fluorescence intensities, for both TC*(I4G) and TC*, respectively. For TC* at temperatures <≈50°C (corresponding to denatured fractions of up to ≈0.8), random-coil conformations are not significantly populated, indicated by FU values of ≈0.1 that are nearly independent of temperature. In contrast, TC*(I4G) exhibits good correlation of FD and FU values upon thermal unfolding. From the microsecond relaxation kinetics of TC*(I4G), we extract a folding time of 25 ± 1 μs at 22.5°C, which is significantly longer compared with that of TC*. Thus, introduction of the point mutation in the amino-terminal domain leads to melting of the collapsed intermediate state, switching the miniprotein to true two-state folding behavior and reduced folding efficiency. Probe-induced artifacts (that is, the formation of an unspecific collapse of TC* and deteriorations thereof by exchange of I4 by G) presumes the involvement of I4 in the formation of the unspecifically collapsed state. Because interaction energies between organic dyes and amino acids are much stronger for aromatic compared with aliphatic side chains, the exchange of I4 by G would not result in elimination of a probe-induced intermediate.

Fig. 3.

Temperature-dependent folding dynamics of the mutant TC*(I4G). (A) Expanded view of autocorrelation functions recorded from TC*(I4G) at various temperatures on the nanosecond to microsecond time scale. (B) Correlation plot of the denatured fraction (FD) versus the unfolded fraction (FU) of TC* (filled green bars) and TC*(I4G) (filled red bars). Open green bars show corresponding data recorded from TC* at pH 3.0. FD values are monitored by steady-state MR121 fluorescence intensities, whereas FU values correspond to the normalized amplitudes of nanosecond relaxation kinetics (K2) extracted from FCS data. The theoretical blue line represents 100% correlation.

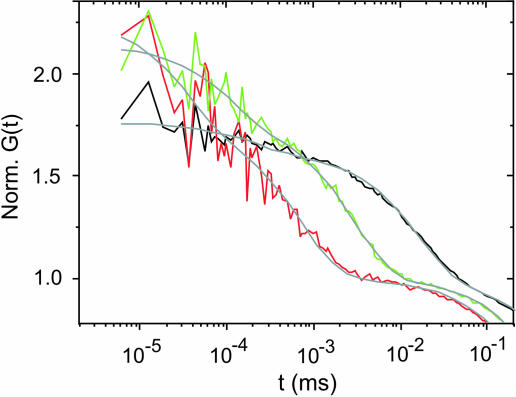

pH Dependence of TC Folding. Neidigh et al. (9) report a considerable increase in folding stability upon introduction of the salt bridge-forming residues aspartic acid (D9) and arginine (R16) during the design of the miniprotein. The salt bridge links the amino-terminal domain with the carboxyl-terminal domain of TC, stabilizing the globular fold (9). Destabilization of tertiary structure due to protonation of D9 in an acidic environment (pH 3.6) has been monitored by a decrease in NH exchange protection in NMR experiments (9). We investigated temperature-dependent folding dynamics of TC* at pH 3.0 monitored by fluorescence quenching of MR121 by Trp. In accordance with NMR experiments, we observe a considerable decrease in folding stability under acidic conditions. Fluorescence quenching data recorded from the label MR121 are in agreement with Trp fluorescence data. The midtransition point of TC* shifts from 35°C at pH 7.4 to 18°C at pH 3.0, similar to that of the mutant TC*(I4G) measured under physiological conditions (data not shown), and folding cooperativity is reduced. FCS curves of TC* at pH 3.0 are dominated by microsecond folding kinetics at low temperatures (i.e., formation and breaking of tertiary interactions) (Fig. 4). However, with increasing temperature, significant contributions of nanosecond relaxation kinetics appear in the autocorrelation function, signaling the existence of an unfolded random-coil population. The correlation plot of denatured fraction FD and unfolded random-coil fraction FU at pH 3.0 is shown in Fig. 3B. In contrast to data recorded for TC* at pH 7.4, partial melting of the intermediate appears under acidic conditions. In fact, folding behavior lies in between that of wild-type and mutant TC* under physiological conditions. Partial melting of the amino-terminal substructure in an acidic environment can be explained by destabilization of the pH-dependent, helix-favoring 1–5-glutamine/aspartic acid interaction (QXXXD) (9). Thus, besides the D9/R16 salt bridge, our FCS study identifies the QXXXD interaction as an additional contribution to folding stability of TC. A recent molecular dynamics simulation study has proposed the formation of the D9/R16 salt bridge to act as a stabilizing element in an on-pathway intermediate, speeding up folding (28). Our fluorescence data point in the opposite direction. We observe no significant change in folding time of TC* upon protonation of D9 (τf = 14 ± 1 μs at 22.5°C and pH 3.0). This result might be explained by two compensating effects. On the one hand, most likely, the D9/R16 salt bridge acts as a kinetic trap that is removed upon protonation of D9. On the other hand, destabilization of the QXXXD interaction leads to a destabilization of the molten globule, slowing down folding.

Fig. 4.

Folding dynamics of TC* monitored under acidic conditions. Autocorrelation functions recorded from TC* under acidic conditions at 5°C (black), 35°C (green), and 55°C (red). Gray lines are data fitting curves obtained by using the model described in Materials and Methods.

Conclusion

Folding dynamics of TC studied under equilibrium conditions using FCS lead us to the conclusion that the 20-residue peptide follows a hierarchical folding mechanism. Besides the observation of folding kinetics, we reveal conformational flexibility in the denatured state of TC under various experimental conditions. Early formation of a collapsed molten globule-like intermediate enhances folding efficiency of TC under physiological conditions. Strongly denaturing conditions (GdmCl) as well as introduction of a helix-breaking point mutation lead to complete melting of the intermediate. Our study contrasts previous reports proposing simple two-state folding (9, 10) and demonstrates that reduction of protein size and simplification of folding topology do not consequently lead to simplification of the folding mechanism. Rather, it underscores the importance of preformed structure in the denatured state for efficient folding of even the smallest globular structure.

Furthermore, our results demonstrate that FCS, in combination with selective fluorescence quenching of fluorophores by the amino acid Trp, can be used advantageously for the monitoring of submillisecond folding dynamics at the nanometer scale with nanosecond time resolution. Unlike nanosecond optical triggering methods (34–37), FCS can be used to study ultrafast folding kinetics under equilibrium conditions and in highly dilute solutions (i.e., at the single-molecule level). We anticipate our technique to be generally applicable in combination with protein engineering and site-specific fluorescence modification. The proposed method complements fluorescence resonance energy transfer, widely applied in modern molecular biology (38, 39), in exploration of both spatial and temporal scales.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. K. H. Drexhage for provision of the oxazine fluorophore MR121 and Prof. N. Metzler-Nolte for giving us the opportunity to perform CD measurements in his laboratory.

Author contributions: H.N., S.D., and M.S. designed research; H.N. and S.D. performed research; H.N. and S.D. analyzed data; and H.N. wrote the paper.

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: FCS, fluorescence correlation spectroscopy; TC, Trp-cage; TCF1, TC residues 1–11; TCF2, TC residues 1–12; GdmCl, guanidinium chloride.

References

- 1.Dobson, C. M. (2003) Nature 426, 884–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferguson, N. & Fersht, A. R. (2003) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 13, 75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roder, H. & Colón, W. (1997) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 7, 15–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jackson, S. E. (1998) Folding Des. 3, R81–R91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kubelka, J., Hofrichter, J. & Eaton, W. A. (2004) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 14, 76–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mayor, U., Guydosh, N. R., Johnson, C. M., Grossmann, J. G., Sato, S., Jas, G. S., Freund, S. M. V., Alonso, D. O. V., Daggett, V. & Fersht, A. R. (2003) Nature 421, 863–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daggett, V. & Fersht, A. (2003) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 4, 497–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Snow, C. D., Nguyen, H., Pande, V. S. & Gruebele, M. (2002) Nature 420, 102–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neidigh, J. W., Fesinmeyer, R. M. & Andersen, N. H. (2002) Nat. Struct. Biol. 9, 425–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qui, L., Pabit, S. A., Roitberg, A. E. & Hagen, S. J. (2002) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 12952–12953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buscaglia, M., Kubelka, J., Eaton, A. & Hofrichter, J. (2005) J. Mol. Biol. 347, 657–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doose, S., Neuweiler, H. & Sauer, M. (Oct. 13, 2005) ChemPhysChem, 10.1002/cphc.200500191. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Vaiana, A. C., Neuweiler, H., Schulz, A., Wolfrum, J., Sauer, M. & Smith, J. C. (2003) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 14564–14572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rigler, R., Mets, U., Widengren, J. & Kask, P. (1993) Eur. Biophys. J. 22, 169–175. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Magde, D., Elson, E. L. & Webb, W. W. (1974) Biopolymers 13, 29–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hess, S. T., Huang, S., Heikal, A. A. & Webb, W. W. (2002) Biochemistry 41, 697–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rigler, R. & Elson, E. S. (2001) Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy: Theory and Applications (Springer, Berlin).

- 18.Chattopadhyay, K., Saffarian, S., Elson, E. L. & Frieden, C. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 14171–14176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neuweiler, H., Schulz, A., Böhmer, M., Enderlein, J. & Sauer, M. (2003) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 5324–5330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang, H., Luo, G., Karnchanaphanurach, P., Louie, T.-M., Rech, I., Cova, S., Xun, L. & Xie, X. S. (2003) Science 302, 262–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhong, D. & Zewail, A. H. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 11867–11872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang, J., Kim, D. H., Lee, S. W., Choi, K. Y. & Sung, Y. C. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 25014–25019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krieger, F., Fierz, B., Bieri, O., Drewello, M. & Kiefhaber, T. (2003) J. Mol. Biol. 332, 265–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hudgins, R. R., Huang, F., Gramlich, G. & Nau, W. M. (2002) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 556–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lapidus, L. J., Eaton, W. A. & Hofrichter, J. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 7220–7225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Snow, C. D., Zagrovic, B. & Pande, V. S. (2002) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 14548–14549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chowdhury, S., Lee, M. C., Xiong, G. & Duan, Y. (2003) J. Mol. Biol. 327, 711–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou, R. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 13280–13285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chowdhury, S., Lee, M. C. & Duan, Y. (2004) J. Phys. Chem. B 108, 13855–13865. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neidigh, J. W. & Andersen, N. H. (2002) Biopolymers 65, 354–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahmed, Z., Beta, I. A., Mikhonin, A. V. & Asher, S. A. (2005) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 10943–10950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ptitsyn, O. B. (1995) Adv. Protein Chem. 47, 83–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuwajima, K. & Arai, M. (2000) in Mechanisms of Protein Folding, ed. Pain, R. H. (Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford), pp. 138–174.

- 34.Jones, C. M., Henry, E. R., Hu, Y., Chan, C. K., Luck, S. D., Bhuyan, A., Roder, H., Hofrichter, J. & Eaton, W. A. (1993) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90, 11860–11864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Callender, R. H., Dyer, R. B., Gilmanshin, R. & Woodruff, W. H. (1998) Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 49, 173–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gruebele, M. (1999) Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 50, 485–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eaton, W. A., Munoz, V., Hagen, S. J., Jas, G. S., Lapidus, L. J., Henry, E. R. & Hofrichter, J. (2000) Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 29, 327–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weiss, S. (2000) Nat. Struct. Biol. 7, 724–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Selvin, P. R. (2000) Nat. Struct. Biol. 7, 730–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]