Abstract

In our previous study, we established that inhibition of apoptosis by the general caspase inhibitor is associated with an increase in the level of oxidized proteins in a multicellular eukaryotic system. To gain further insight into a potential link between oxidative stress and apoptosis, we carried out studies with Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which contains a gene (YCA1) that encodes synthesis of metacaspase, a homologue of the mammalian caspase, and is known to play a crucial role in the regulation of yeast apoptosis. We show that upon exposure to H2O2, the accumulation of protein carbonyls is much greater in a Δyca1 strain lacking the YCA1 gene than in the wild type and that apoptosis was abrogated in the Δyca1 strain, whereas wild type underwent apoptosis as measured by externalization of phosphatidylserine and the display of TUNEL-positive nuclei. We also show that H2O2-mediated stress leads to up-regulation of the 20S proteasome and suppression of ubiquitinylation activities. These findings suggest that deletion of the apoptotic-related caspase-like gene leads to a large H2O2-dependent accumulation of oxidized proteins and up-regulation of 20S proteasome activity.

Keywords: H2O2, metacaspase, programmed cell death, proteasome activity, protein carbonyl

During the last decade, the caspase genes related to apoptosis in multicellular eukaryotic organisms have been extensively studied, and the mechanism of programmed cell death is well documented (1, 2). The possibility that inappropriate regulation or inhibition of apoptotic capacity might contribute to the aging process and to the development of some pathologies is underscored by the demonstration that inhibition of apoptosis in cultured mammalian acute promyelocytic leukemia-derived NB4 cells leads to a substantial increase in the accumulation of oxidized proteins (3). Both processes are characteristic of aging and many diseases (4). As noted earlier (1), the removal of irreversibly damaged cells by apoptosis might have a critical role in the maintenance of tissue integrity because it permits replacement of the damaged cells in tissues with new cells. Results of recent investigations show that unicellular organisms also possess the ability to undergo programmed cell death (5–7). In particular, yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae dies in an apoptotic-like manner in response to oxidative stress (8–11). The budding yeast S. cerevisiae has emerged as a useful system for programmed cell death or apoptotic studies because it is readily amenable to genetic and molecular analysis (12). As with mammalian cells, reactive oxygen species (ROS) are also produced in yeast cells undergoing cell death in response to a number of external or internal stimuli (13). It was proposed that yeast cells might commit suicide to provide nutrients for other, probably younger and fitter, cells (14). However, the recent demonstration that the yeast YCA1 (Yor197w) gene codes for a metacaspase that is structurally homologous and exhibits proteolytic activity analogous to mammalian caspases (15) indicates that the yeast apoptotic machinery is functionally equivalent to that of mammals (16). H2O2 is an important mediator of intracellular signaling, which exerts potent oxidative stress and induces apoptosis. Disruption of the YCA1 gene abrogates H2O2-induced apoptosis, whereas overexpression of YCA1 increases H2O2-induced caspase-like activity and apoptosis (15).

We report here results of studies to determine the effects of YCA1 disruption in S. cerevisiae on the H2O2-mediated apoptosis and oxidation of endogenous proteins to carbonyl and methionine sulfoxide derivatives. We also examine the relationship between apoptosis and changes in proteasome activities.

Materials and Methods

Strains and Growth Conditions. The S. cerevisiae wild-type yeast (BY 4743) and Δyca1 (homozygous diploid) cells were grown on yeast extract/peptone/dextrose medium containing 1% bactoyeast extract, 2% bacto-tryptone, and 2% glucose; however, 200 μg/ml Geniticin antibiotic was added to the medium used for growth of Δyca1 cells. The strains were obtained from Open Biosystems (www.openbiosystems.com). Both strains were grown to early stationary phase at 30°C. Then amounts of the cell suspensions needed to yield an OD600 of 2.0 were added to fresh media containing various concentrations of H2O2, and the cultures were allowed to grow for 4 h at 30°C.

Protein Preparation, Electrophoresis, and Western Blot. After incubation in the presence or absence of H2O2, the yeast cells were harvested by centrifugation, and the sedimented pellets were suspended in 1 ml of lysis buffer, prepared by dissolving one tablet of EDTA-free protease inhibitor (Roche Diagnostics) in 10 ml of PBS (pH 7.4) containing 0.1% vol/vol Triton X-100. The cells were lysed with acid-washed glass beads in a MiniBeads beater (BioSpec, Bartlesville, OK). After lysis, the soluble cell proteins were separated from insoluble debris by centrifuging at 2,100 × g for 15 min, and the supernatant solutions were frozen at –20°C until used. Protein concentration was determined by using bicinchoninic acid (BCA) reagents with BSA as standard. For Western analysis, aliquots of total protein (20 μg per lane) were fractionated by Nu-PAGE and blotted onto nitrocellulose membrane (Invitrogen). The membrane was blocked by 5% nonfat dry milk. Anti-RPT1, RPT2, and RPT5 from Biomol (Plymouth Meeting, PA) and anti-Ubc, anti-smt3, and anti-PGK from Abcam (Cambridge, MA) were used as primary Abs at a dilution of 1:2,000. The membranes were incubated with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-mouse or goat anti-rabbit secondary Abs for 30 min (dilution of 1:5,000). Specific proteins were detected with the blotting reagent CSPD [disodium 3-(4-methoxyspiro{1,2-dioxetane-3,2′-(5′-chloro) tricyclo-[3.3.1.13.7]decan}-4-yl) phenyl phosphate] containing Nitroblock, and chemiluminescence was detected by exposure of membranes to Kodak X-Omat films.

Immunoblot Analysis of Protein Carbonyl. Assays were performed as described in refs. 17 and 18 with slight modifications. Equal amounts (20 μg) of the soluble protein in the cell extracts were derivatized by adding 14 μl of 2,4-dinitrophenyl hydrazine reagent to 14 μl of sample in lysis buffer containing 6% SDS (pH 7.2). The reaction was allowed to continue at room temperature for 10 min. The derivatization reaction was stopped by adding 12 μl of neutralizing solution containing 2 M Tris base, 30% glycerol (final concentration 0.52 M), and 1.3 μl of 2-mercaptoethanol (pH 6.9), followed by vortexing. Derivatized protein samples were then loaded onto a 12% Nu-PAGE gel, and electrophoresis was run at 150 V for 75 min. Subsequently, the proteins were transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. For dot blots, 2-μl aliquots of each sample from the above derivatized protein samples were applied to dry nitrocellulose membranes and then the dots were dried. The membrane was blocked by Li-Cor block (Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE) without Tween-20 for 30 min before immunostaining. The 2,4-dinitrophenyl hydrazine-bound protein was detected by using rabbit anti-2,4-dinitrophenyl (DNP) (DAKO) as a primary Ab (1:2,000 dilution) in Li-Cor block with 0.1% Tween-20. The membrane was then incubated in the dark for 30 min with goat anti-rabbit polyclonal Ab labeled with IR800CW 611-131-122 (Rockland, Gilbertsville, PA) as a secondary Ab. For dot blots, oxidized glutamine synthetase was used as a standard for quantification of oxidized protein. The protein carbonyl detection and quantification was done by using the Odyssey scanner (Li-Cor).

Analysis of Oxidized Methionine. Ten micrograms of protein from cell extract was dried by vacuum centrifugation (Savant) in 4-ml glass vials followed by CNBr cleavage (19). CNBr cleaves peptide bonds on the carboxyl side of methionine, yielding homoserine; it does not cleave at methionine sulfoxide. CNBr was prepared as a 10 mM stock solution in acetonitrile, then diluted to 100 mM with 70% formic acid just before use. One hundred microliters was added to the vial, which was capped and incubated for 1 h at 70°C in a hood and, after centrifugation at 750 × g for 5 min, the samples were dried overnight by speed-vacuum centrifugation. The dried samples were hydrolyzed in 6 M HCl at 155°C for 45 min in the presence of 2 mM DTT. Hydrolysates were dried by vacuum centrifugation and dissolved in 200 μl of 0.05% of TFA, and amino acid analyses were carried out on samples with and without CNBr treatment by using the HPLC technique (19).

FACS Analysis of Apoptosis. For apoptotic analyses, the manufacturer's protocol was followed. Briefly, cells were washed with PBS (pH 7.4) and suspended in the 100-μl binding buffer (10 mM Hepes buffer containing 140 mM NaCl and 2.5 mM CaCl2, pH 7.4), and then 5 μl of FITC-annexin V was added. After incubation for 15 min at room temperature, 400 μl of the same buffer was added, and externalization of phosphatidylserine was determined by using the FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson) with excitation and emission wavelength settings at 488 and 530 nm, respectively (FL1 detector). Analysis was performed by using cellquest software (Becton Dickinson).

Morphological Analysis of Apoptotic Cells. For TUNEL-peroxidase staining, we used the In Situ Cell Death kit (Roche Diagnostics). The treated and untreated wild-type and Δyca1 cells were attached to poly(l-lysine)-coated glass-bottomed dishes and fixed for 30 min in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS (pH 7.4). After the cells were washed three times with PBS, the endogenous peroxidase was inactivated by incubation with 3% H2O2 in methanol for 30 min at room temperature. The cells were then washed with PBS and subsequently permeabilized for 2 min on ice with 0.1% sodium-citrate solution containing 0.1% Triton X-100. The cells were then washed twice with PBS, stained with the TUNEL reaction mixture for 60 min at 37°C, washed twice with PBS, and labeled with peroxidase-conjugated goat Ab for 30 min at 37°C. DNA fragmentation was detected by staining with diaminobenzidine (DAB) substrate and observed under a microscope (Spot Insight with digital camera, Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI).

20S Proteasome Activity. The Proteasome Activity kit (Chemicon) was used to measure the 20S proteasome's chymotryptic-like activity. Clear whole-cell extract (50 μg) was incubated with fluorogenic proteasome substrate, suc-LLVY-AMC, in 100 μlof reaction mixture for 1 h at 37°C, followed by fluorescence measurement of the free AMC formed with the CytoFluor multiwell plate reader (Series 4000, PerSeptive Biosystems, Framingham, MA) with excitation and emission wavelengths at 380 and 460 nm, respectively.

Results

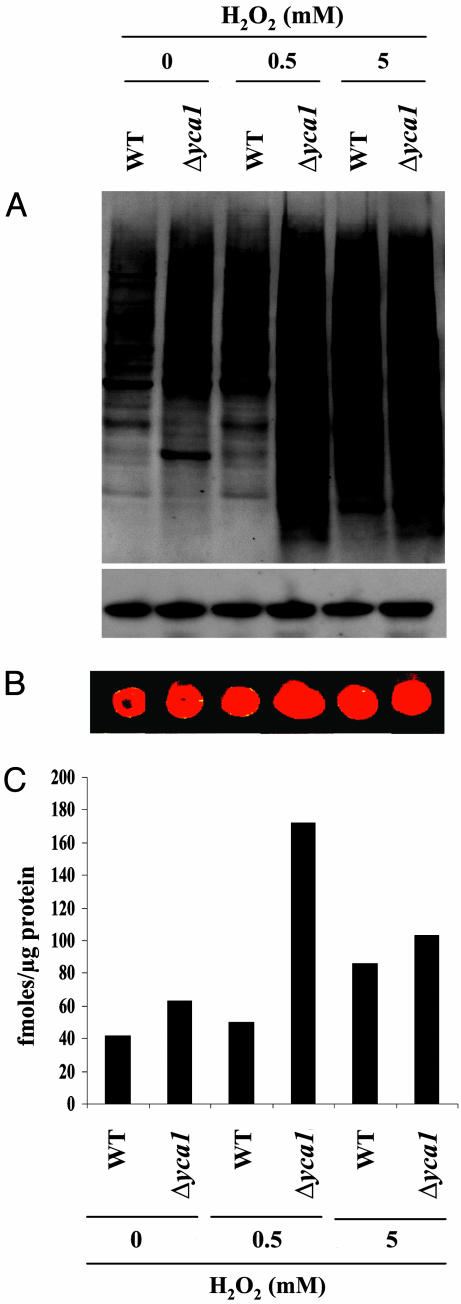

Knockout of Apoptotic-Related Protein, YCA1, Is Correlated with the Accumulation of Oxidized Protein. In previous studies, the correlation between the inhibition of apoptosis and protein carbonyl accumulation in response to indirect and direct effects of arsenic trioxide (As2O3) and H2O2, respectively, was demonstrated in multicellular eukaryotic organisms (3). In this study, we demonstrated that the same phenomenon also exists in unicellular eukaryotic systems. In mammals, caspases are involved in apoptosis, whereas a structurally similar analog, metacaspase (YCA1), is responsible for programmed cell death in yeast. We examined the effects of H2O2 concentration on the formation of protein carbonyl derivatives in wild-type S. cerevisiae and in a Δyca1 strain lacking the YCA1 enzyme. The protein carbonyl content of the wild type increased progressively with increases in the concentration of H2O2 up to 5 mM. By comparison, the protein carbonyl level in the Δyca1 cells was significantly greater than that of the wild type and increased with H2O2 concentrations up to 1 mM but decreased gradually with concentrations >2 mM (data not shown). In further studies, we elected to compare the effects of 0, 0.5, and 5 mM concentrations of H2O2 on various parameters. As shown in Fig. 1, the protein carbonyl content of cells grown in the absence of H2O2 was slightly greater in the Δyca1 cells than in the wild-type cells; but the level of protein carbonyls in Δyca1 cells grown in the presence of 0.5 mM H2O2 was much greater than that of the wild-type cells and, as mentioned above, the level in Δyca1 cells was appreciably lower in 5 mM than in 0.5 mM H2O2 but was still greater than in wild-type cells.

Fig. 1.

Effect of caspase deletion on the sensitivity of yeast proteins to H2O2-mediated oxidation to carbonyl derivatives. Wild-type S. cerevisiae and Δyca1 cells were incubated for 4 h at 30°C in the presence of 0, 0.5, or 5 mM H2O2, as indicated. (A) Immunoblot analysis of protein carbonyls. Phosphoglycerate kinase was used as a loading control. (B) Dot blot, aliquots of 2-μl 2,4-dinitrophenyl hydrazine-derivatized protein samples from A were used. Oxidized glutamine synthetase was used as a standard. (C) Densitometric analysis by dot blot was used to prepare the bar graph.

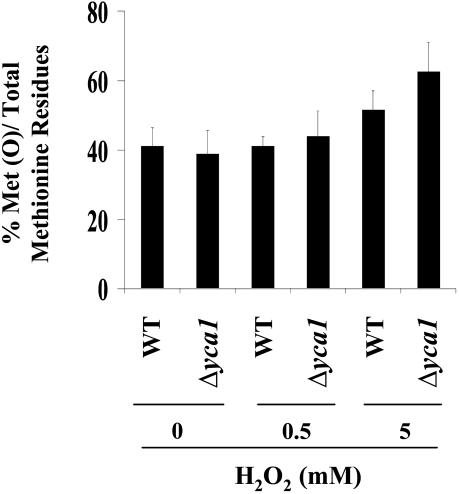

Analysis of Oxidized Methionines in Wild-Type and Δyca1 Strains. Methionine residues of proteins are readily oxidized to methionine sulfoxide (MetO) derivatives by ROS. Results of studies to determine the effect of H2O2 concentration on the generation of MetO in Δyca1 and wild-type yeast are summarized in Fig. 2. The level of MetO increased with increasing H2O2 concentrations, but the increase was significantly greater in the Δyca1 strain. The Δyca1 cells treated with 0.5 and 5 mM H2O2 showed 3% and 21% more oxidized methionines, respectively, compared with wild-type cells with equivalent treatment (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Effect of H2O2 concentration on the oxidation of methionine residues of proteins in wild-type and Δyca1 cells. After a 4-h incubation in the presence of 0, 0.5, or 5 mM H2O2, as indicated, the fraction of methionine residues converted to methionine sulfoxide was determined as described in Materials and Methods. Results shown are the means of three independent experiments (bars are ±SD).

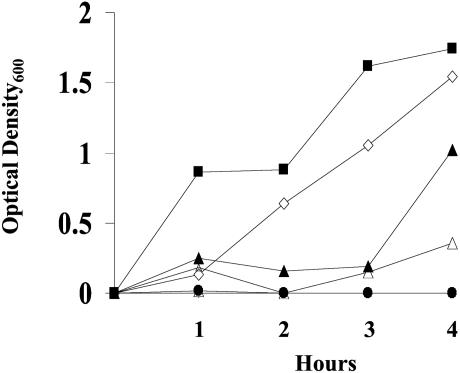

Effect of H2O2 on Growth of Wild-Type and Δyca1 Cells. To examine the effect of H2O2 concentration on the growth of wild-type and Δyca1 cells, we measured the time-dependent changes in optical density (OD600) of cultures exposed to various H2O2 concentrations. As shown in Fig. 3, growth of both strains was delayed during the first 2–3 h of exposure to 0.5 mM H2O2 but then increased, and after 4 h, the densities of the wild-type and Δyca1 cultures were 23% and 59% of those observed in the absence of H2O2, respectively. However, exposure to 5 mM H2O2 led to complete inhibition of cell growth and to a small (8–9%) decrease in cell density of both strains, likely reflecting H2O2-induced apoptosis, or necrosis.

Fig. 3.

Effects of caspase deletion and H2O2 concentration on growth capacity. The wild-type and Δyca1 cells were grown for 4 h at 30°C in culture media containing 0, 0.5, or 5 mM H2O2, and cell growth was measured by time-dependent changes in the optical density (OD600). Open symbols ([figchr; ⋄, ▵, and (□) refer to the relative densities of wild-type cultures in the presence of 0, 0.5, and 5 mM H2O2, respectively. Closed symbols (▪, ▴, and •) refer to the relative densities of Δyca1 cultures in the presence of 0, 0.5, and 5 mM H2O2, respectively.

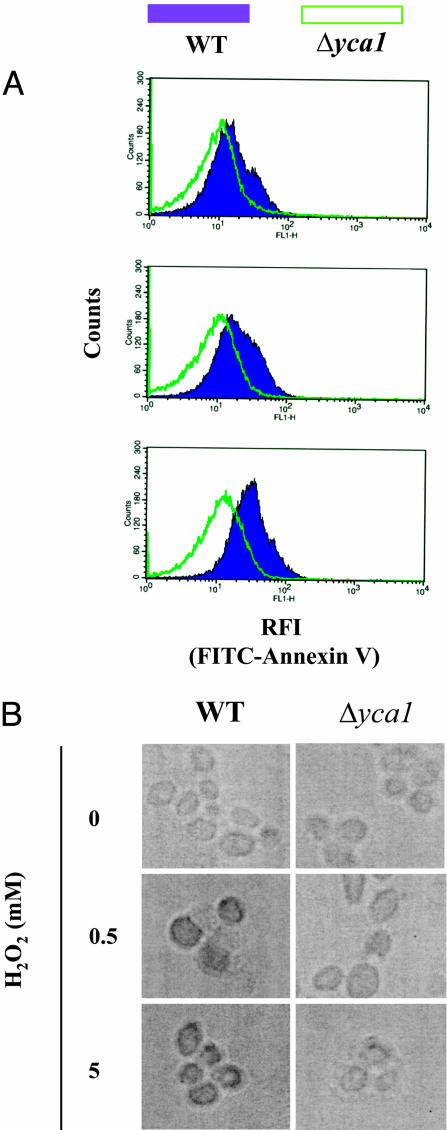

Yeast Mimic Typical Mammalian Downstream Apoptotic Characteristics. In mammals, the upstream events are initiated by intracellular ROS production, which is followed by the decrease of mitochondrial membrane potential and release of cytochrome-C and thereby to activation of apoptosis. In normal cells, membrane phospholipids are distributed asymmetrically between inner and outer leaflets of the plasma membrane. Downstream events occurring during apoptosis include flipping out of phosphatidylserine that interacts with annexin-V on the outer surface of the membrane and condensation of nuclei. Accordingly, externalization of phosphatidylserine and generation of TUNEL-positive nuclei are used as a measures of apoptosis. To test the specificity of the apoptotic response in yeast, we performed FACS analysis of phosphatidylserine externalization by introducing FITC-conjugated annexin-V into the wild-type and Δyca1 cell samples. As shown in Fig. 4A, the increase in the apoptotic population was observed in wild-type cells exposed to H2O2 in concentration-dependent manner with the emergence of a higher fluorescence peak, a phenomenon not observed with the Δyca1 cells. Similar results were obtained by using the TUNEL assay. Exposure of wild-type cells to H2O2 led to the formation of apoptotic bodies and TUNEL-positive nuclei (Fig. 4B). In contrast, Δyca1 cells showed no characteristics of apoptosis. Moreover, after treatment with H2O2, it was confirmed by immunoblot analysis that the wild-type cells contain a band corresponding to the caspase-like protein, YCA1, whereas no such band was observed in the Δyca1 strain (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Analysis of apoptotic cells. After treatment with various concentrations of H2O2, as indicated, apoptosis was measured by FACS analysis of phosphatidylserine externalization and by TUNEL-staining of nuclei, as described in Materials and Methods. (A) FACS measurements of wild-type (shaded) and Δyca1 cells (unshaded). Upper, 0 μMH2O2; Middle, 0.5 mM H2O2; Lower, 5 mM H2O2.(B) Detection of DNA breaks by TUNEL staining. Apoptotic cells were visible in the form of dark bodies.

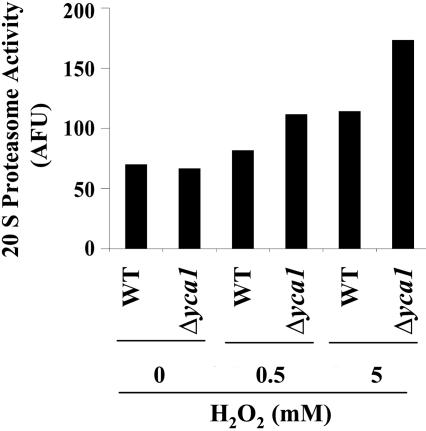

Effect of Oxidized Proteins on Proteasome Activity. To determine whether the 20S proteasome is involved in degradation of oxidized proteins formed during incubations with H2O2, we measured the ability of whole-cell extracts of wild-type and Δyca1 cells to catalyze cleavage of the 20S proteasome fluorogenic substrate, suc-LLVY-AMC. In untreated cells, the 20S proteasome activity of wild-type and Δyca1 cells was almost the same. However, after treatment with 0.5 and 5 mM H2O2, the activity was increased 1.2- and 1.6-fold for wild-type and 1.7- and 2.6-fold for Δyca1 cells, respectively, compared with the respective controls (Fig. 5). The observed increase in 20S proteasome activity might reflect an induction of the proteasome in response to enhanced accumulation of oxidized proteins.

Fig. 5.

Assay of 20S proteasome. The activity was measured by fluorometric analysis of the cleavage of the suc-LLVY-AMC peptide as described in Materials and Methods. The activity was presented as arbitrary fluorescence unit observed.

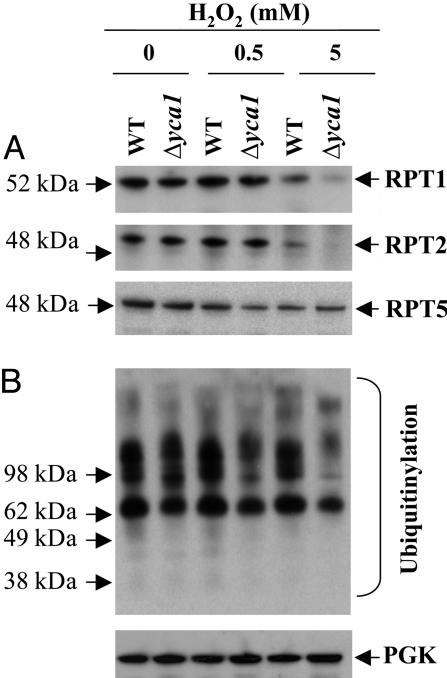

RPT1, RPT2, and RPT5 are the among the six ATPases of the 19S regulatory particle of the 26S proteasome involved in the degradation of polyubiquitinated substrates of yeast. By means of immunoblot analysis, it was shown that treatment of yeast cells with 0.5 mM H2O2 had little, if any, effect on the levels of RPT1, RPT2, and RPT5 proteins; however, treatment with 5 mM H2O2 led to a significant decrease in the levels of RPT1 and RPT2 in the wild-type cells and an even greater decrease in the Δyca1 cells but had little effect on the level of RPT5 (Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6.

Effect of H2O2 concentration on levels of the 19S regulatory subunits, and on ubiquitinylated proteins. After exposing wild-type and Δyca1 cells to various concentrations of H2O2, cell samples were subjected to immunoblot analyses of specific proteins as described in Materials and Methods.(A) RPT1, RPT2, and RPT5 subunits of 19S regulatory particle. (B) Ubiquitinylated proteins. Phosphoglycerate kinase was used as a loading control.

To determine whether ubiquitinylation might have a role in the degradation of oxidized proteins, we measured the levels of ubiquitinylated proteins using the ubiquitin polyclonal Ab in the whole-cell extract of wild-type and Δyca1 cells treated with various concentrations of H2O2. Surprisingly, ubiquitinylation was suppressed upon exposure to H2O2 oxidative stress in both wild-type and Δyca1 cells in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 6B). However, the wild-type cells contained much higher concentrations of ubiquitinylated proteins than the Δyca1 cells.

Discussion

Programmed cell death (apoptosis) is the basis of a highly coordinated cellular suicide program that is crucial for maintenance of health and tissue function. Misregulation of apoptosis can lead to a number of neurodegenerative and physiological disorders (20). Although previously thought to be restricted to animals, recent studies have shown that programmed cell death also occurs in unicellular organisms. For example, yeast contain a metacaspase (YCA1) that is structurally homologous to mammalian caspases (7). Overexpression of the YCA1 gene stimulates apoptotic cell death, whereas no apoptosis occurs in Δyca1 cells (7). It is suggested that YCA1-mediated apoptosis might have developed to eliminate cells that are not able to adapt to a new environment, e.g., predamaged cells or replicative older cells (14). Similar to mammalian cells, ROS are also produced in yeast undergoing cell death in response to a number of external or internal stimuli (13).

Yoo and Regnier (21) showed that the level of protein carbonyls in yeast reached a maximum of 1.7 times higher than the control value after exposure to 5 mM H2O2 for 1 h; thereafter, the carbonyl content gradually decreased within 3 h. We show here that in the absence of H2O2, the level of protein carbonyls in Δyca1 cells is ≈1.5 times greater than that of wild-type cells; however, their responses to the addition of 0.5 and 5 mM H2O2 concentrations were very different. Incubation of wild-type yeast with 0.5 mM H2O2 ledtoa slight increase (1.2-fold) in the levels of oxidized protein compared with levels in the absence of H2O2, whereas exposure to 5 mM H2O2 led to a 2.1-fold increase in the protein carbonyl content. In contrast, treatment of the Δyca1 cells with 0.5 mM H2O2 led to an enormous increase (2.7-fold) in the level of protein carbonyls, but upon exposure to 5 mM H2O2, there was a substantial decrease in the level of protein carbonyl derivatives (Fig. 1). Among other possibilities, differences in the responses of protein carbonyl levels of wild-type and Δyca1 cells to increasing H2O2 concentrations may reflect differences in the effects of H2O2 on their 20S proteasome activities. As shown in Fig. 5, exposure of the wild-type and Δyca1 cells to 5 mM H2O2 led to 1.6- and 2.6-fold increases in their 20S proteasome activity, respectively. In view of the fact that oxidation of proteins increases their sensitivity to degradation by the 20S proteasome (22–26), the large decline in the level of protein carbonyls observed when the level of H2O2 was increased from 0.5 to 5 mM in Δyca1 cells might reflect an increase in the rate of degradation of the oxidized proteins in response to the large increase in the proteasome level that occurs in the Δyca1 cells under these conditions. It is noteworthy that apoptosis is also associated with a progressive decrease in cell mass due to protein degradation or decreased synthesis (27).

All amino acids are susceptible to oxidation, but their susceptibilities vary greatly (28). Methionine residues in proteins are susceptible to oxidation by ROS, such as H2O2 (19). In the present study, treatment of the Δyca1 cells with 0.5 and 5 mM concentrations of H2O2 led to 3% and 21% greater, respectively, increases in the fractions of methionine residues converted to MetO than that observed for the wild type (Fig. 2). Unlike other amino acid residues (except cysteine), the oxidation of methionine can be repaired by the action of methionine sulfoxide reductase (29, 30); therefore, the accumulation of MetO may reflect either a decrease in the concentration of the reductase or an increase in the rate of ROS formation (30). Nevertheless, oxidation of methionine residues in proteins has been shown to increase their susceptibility to proteolysis by the proteasome (19). In confirmation of the fact that apoptosis is associated with externalization of phosphatidylserine on the surface of the membrane (31, 32) and the condensation of nucleic acid to form TUNEL-positive derivatives (33), we showed that upon exposure to H2O2, the Δyca1 strain failed to exhibit either of these characteristics. In contrast, exposure of the wild type to H2O2 led to both phosphatidylserine externalization and formation of TUNEL-positive nuclei (Fig. 4).

The proteasome is also an essential part of the protein oxidation surveillance mechanism. Proteasomes common among eukaryotic species and the amino acid sequences of its subunits are highly conserved in humans and S. cerevisiae (34). The proteasome plays a critical role in the maintenance of cellular homeostasis. Oxidized protein clearance is a complex process. The accumulation of damaged or oxidized protein reflects not only the rate of protein modification but also the rate of damaged or oxidized protein degradation that is dependent, at least in part, on the activity of intracellular proteases that preferentially degrade damaged proteins (35). Moreover, oxidized proteins are retained by maternal cells so that daughter cells begin with a lower oxidized protein burden (36). There is considerable evidence that the 20S proteasome is responsible for the preferential degradation of oxidatively modified intracellular proteins in the absence of ATP and ubiquitin (22–26, 37–39), whereas the 26S proteasome (with or without ATP/ubiquitin) has only a minimal ability to selectively degrade oxidatively modified proteins (37). In another report, it was demonstrated that the ATP/ubiquitin-dependent 26S proteasome is very sensitive to direct oxidative inactivation (39), and the oxidative stress eventually suppresses the ubiquitinylation process (40), whereas the 20S proteasome complex is quite resistant (39). The further observation that exposure of Δyca1 cells to H2O2-mediated oxidative stress leads to decreases in the levels of the RPT1 and RPT2 and to a lesser extent the RPT5 subunits of the 19S particle of the 26S proteasome raises the possibility that caspase may have an important role in protein ubiquitination.

Interestingly, knocking out of the apoptotic-related caspase-like gene, YCA1, leads to a large H2O2-dependent accumulation of intracellular oxidized proteins and in the elevation of 20S proteasome activity. However, the basic mechanisms responsible for these changes remain to be established.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Hammou Oubrahim for discussions; Barbara Berlett, Nancy Wehr, and Dr. Ephrem Tekle for technical assistance; and Dr. Noriyuki Miyoshi for help with FACS analysis. This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute).

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

Abbreviations: MetO, methionine sulfoxide; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

References

- 1.Stadtman, E. R. & Levine, R. L. (2002) Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 21, 83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nijhawan, D., Honarpour, N. & Wang, X. (2000) Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 23, 73–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan, M. A. S., Oubrahim, H. & Stadtman, E. R. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 11560–11565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stadtman, E. R. & Berlett, B. S. (1998) Drug Metab. Rev. 30, 225–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raff, M. (1998) Nature 396, 119–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Skulachev, V. P. (2002) FEBS Lett. 25, 23–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Madeo, F., Engelhardt, S., Herker, E., Lehmann, N., Maldener, C., Proksch, A., Wissing, S. & Frohlich, K. U. (2002) Curr. Genet. 41, 208–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Madeo, F., Frohlich, E., Ligr, M., Grey, M., Sigrist, S. J., Wolf, D. H. & Frohlich, K. U. (1999) J. Cell Biol. 145, 757–767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ligr, M., Velten, I., Frohlich, E., Madeo, F., Ledig, M., Frohlich, K. U., Wolf, D. H. & Hilt, W. (2001) Mol. Biol. Cell 12, 2422–2432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davermann, D., Martinez, M., McKoy, J., Patel, N., Averbeck, D. & Moore, C. W. (2002) Free Radical Biol. Med. 33, 1209–1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Phillips, A. J., Sudbery, I. & Ramsdale, M. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 14327–14332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watanabe, N. & Lam, E. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 14691–14699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodriguez-Menocal, L. & D'Urso, G. (2004) FEMS Yeast Res. 5, 111–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herker, E., Jungwirth, H., Lehmann, K. A., Maldener, C., Frohlich, K. U., Wissing, S., Buttner, S., Fehr, M., Sigrist, S. & Madeo, F. (2004) J. Cell Biol. 164, 501–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Madeo, F., Herker, E., Maldener, C., Wissing, S., Lächelt, S., Herlan, M., Fehr, M., Lauber, K., Sigrist, S. J., Wesselborg, S. & Frohlich, K. U. (2002) Mol. Cell 9, 911–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bettiga, M., Calzari, L., Orlandi, I., Alberghina, L. & Vai, M. (2004) FEMS Yeast Res. 5, 141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levine, R. L., Williams, J. A., Stadtman, E. R. & Schacter, E. (1994) Methods Enzymol. 233, 346–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keller, R. J., Halmes, N. C., Hinson, J. A. & Pumford, N. R. (1993) Chem. Res. Toxicol. 6, 430–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levine, R. L., Mosoni, L., Berlett, B. S. & Stadtman, E. R. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 15036–15040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Uren, A. G. & Vaux, D. L. (1996) Pharmacol. Ther. 72, 37–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoo, B. S. & Regnier, F. E. (2004) Electrophoresis 25, 1334–1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rivett, A. J. (1985) J. Biol. Chem. 260, 12600–12606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rivett, A. J. (1986) Curr. Top. Cell. Regul. 28, 291–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davies, K. J. A. & Goldberg, A. L. (1987) J. Biol. Chem. 262, 8227–8234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rivett, A. J., Roseman, J. E., Oliver, C. N., Levine, R. L. & Stadtman, E. R. (1985) in Intracellular Protein Catabolism, eds. Khairallah, E. A., Bond, J. S. & Bird, J. W. C. (Liss, New York), pp. 317–328.

- 26.Davies, K. J. A. (1987) J. Biol. Chem. 262, 9895–9901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Piedimonte, G., Crinelli, R., Salda, L. D., Corsi, D., Pennisi, M. G., Kramer, L., Casabianca, A., Sarli, G., Bendinelli, M., Marcato, P. S. & Magnani, M. (1999) Exp. Cell Res. 248, 381–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stadtman, E. R. (1993) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 62, 797–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Petropoulos, I. & Friguet, B. (2005) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1703, 261–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moskovitz, J., Bar-Noy, S., Williams, W. M., Requena, J., Berlett, B. S. & Stadtman, E. R. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 12920–12925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kenis, H., van Genderen, H., Bennaghmouch, A., Rinia, H. A., Frederik, P., Narula, J., Hofstra, L. & Reutelingsperger, C. P. M. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 52623–52629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schuler, M., Bossy-Wetzel, E., Goldstein, J. C., Fitzgerald, P. & Green D. R. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 7337–7342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang, G. Q., Gaitan, A., Hao, Y. & Wong, F. (1997) Microsc. Res. Tech. 36, 123–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glickman, M. H., Rubin, D. M., Fried, V. A. & Finley, D. (1998) Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 149–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Petropoulos, I., Conconi, M., Wang, X., Hoenel, B., Bregegere, F., Milner, Y. & Friguet, B. (2000) J. Gerontol. A 55, 220–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aguilaniu, H., Gustafsson, L., Rigoulet, M. & Nystrom, T. (2003) Science 299, 1751–1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Davies, K. J. A. (2001) Biochemie 83, 301–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schnall, R., Mannhaupt, G., Stucka, R., Tauer, R., Ehnle, S., Schwarzlose, C., Vetter, I. & Feldmann, H. (1994) Yeast 10, 1141–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reinheckel, T., Sitte, N., Ulrich, O., Kuckelkorn, U., Grune, T. & Davies, K. J. A. (1998) Biochem. J. 335, 637–642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Inai, Y. & Nishikimi, M. (2002) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 404, 279–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]