Abstract

The class II transactivator (CIITA) is the master regulator of major histocompatibility complex class II (MHCII) transcription. Its activity is regulated at the post-transcriptional level by phosphorylation and oligomerization. This aggregation mapped to and depended on the phosphorylation of residues between positions 253 and 321 in CIITA, which resulted in a dramatic accumulation of the protein and increased expression of MHCII genes in human promonocytic U937 cells, which represent immature antigen-presenting cells. Thus, the post-transcriptional modification of CIITA plays an important role in the immune response.

Keywords: CIITA/MHCII transcription/oligomerization/phosphorylation

Introduction

Major histocompatibility complex class II (MHCII) molecules play a fundamental role in the homeostasis of the immune response. They dictate the immune repertoire in the thymus and activate CD4+ T cells in the periphery (Germain, 1994). MHCII genes are expressed constitutively on antigen-presenting cells, such as B cells, thymic epithelial cells and dendritic cells, and after IFNγ induction in macrophages and other cell types (Glimcher and Kara, 1992). Their expression is regulated primarily at the level of transcription (Benoist and Mathis, 1990). The elucidation of the molecular defects in mutant somatic cell lines generated in vitro (Gladstone and Pious, 1978; Accolla, 1983; Calman and Peterlin, 1987) and in cells from patients with the bare lymphocyte syndrome, which is a severe combined immunodeficiency (Griscelli et al., 1989), which lack MHCII determinants, facilitated the identification of factors controlling the transcription of these genes (Reith and Mach, 2001). Among them, the class II transactivator (CIITA), the product of the AIR-1 locus (Accolla et al., 1986), regulates the constitutive and inducible expression of MHCII genes (Steimle et al., 1993, 1994; Chang et al., 1994).

CIITA is a non-DNA-binding co-activator that is recruited to MHCII promoters via many proteins bound to DNA (Caretti et al., 2000; De Sandro et al., 2000). It measures 1130 amino acids (aa) and has four essential functional domains. Its N-terminal acidic region forms the transcriptional activation domain (AD). This AD binds components of the general transcriptional machinery and other cofactors to direct the initiation and elongation of MHCII transcription. (Kretsovali et al., 1998; Fontes et al., 1999; Kanazawa et al., 2000). The N-terminus of CIITA also contains an acetyltransferase activity (Raval et al., 2001). Although its specific role is still elusive, the proline-, serine- and threonine-rich domain (P/S/T) is essential for the activity of CIITA (Chin et al., 1997). The GTP-binding domain (GBD) and the C-terminal leucine-rich repeats (LRR) are critical for the subcellular localization of CIITA (Harton et al., 1999; Hake et al., 2000).

Several distinct promoters direct the expression of the CIITA gene (Muhlethaler-Mottet et al., 1997), which ensures the presence of CIITA in different cellular compartments (Landmann et al., 2001). Whereas the transcriptional control of CIITA is understood, very little is known about how the activity of CIITA itself is regulated. Nevertheless, the activity of many transcription factors is controlled by their post-transcriptional modification, like phosphorylation, oligomerization, glycosylation, acetylation and ubiquitylation (Darnell, 1997; Sartorelli et al., 1999; Fuchs et al., 2000).

In this study, the role of two such modifications, oligomerization and phosphorylation, in the activity of CIITA was investigated. We demonstrated that phosphorylation is a prerequisite for CIITA aggregation, which involves a short fragment in the C-terminus of the P/S/T region. In addition, oligomerization increased the accumulation of CIITA and the expression of MHCII genes in cells.

Results

CIITA oligomerizes in vivo

To examine whether CIITA interacts with itself, COS cells were co-transfected with plasmids that directed the expression of Myc or Flag epitope-tagged CIITA proteins (mCIITA and fCIITA, respectively). COS cells were chosen because they do not express CIITA but support the activity of exogenous CIITA on MHCII promoters (Fontes et al., 1999). Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with the anti-Myc antibody and immunoprecipitations were examined for the presence of fCIITA with the anti-Flag antibody by western blotting. When fCIITA alone was expressed in COS cells, no fCIITA was detected in our immunoprecipitations (Figure 1A, right top panel, lane 6). However, when mCIITA and fCIITA were co-expressed, fCIITA co-immunoprecipitated with mCIITA (Figure 1A, left top panel, lane 1). Thus, CIITA oligomerizes in vivo.

Fig. 1. CIITA oligomerization in COS cells. (A) Residues 1–321 contain the oligomerization domain of CIITA. fCIITA and C-terminal deletion mutant fCIITA proteins were co-expressed with the same mCIITA protein (left top panel) or pcDNA3 (right top panel). Anti-Myc-precipitated proteins were separated by 7.5% SDS–PAGE and analyzed by anti-Flag western blotting (top panels). An aliquot, corresponding to 5% of the pre-cleared cell lysates, was analyzed for the expression of fCIITA and mCIITA by western blotting with specific antibodies (middle and bottom panels). (B) Residues from positions 253–321 are essential for the oligomerization of CIITA. Listed fCIITA proteins were co-expressed with mCIITA(1–699) (left panel) or with pcDNA3 (right panel). Top panels show the results of the binding assay performed as described in (A). Expression levels of fCIITA proteins and mCIITA(1–699) were evaluated as in (A). (C) Sequences from positions 253–410 are required for optimal CIITA oligomerization. fCIITA(253–410) was expressed alone (lanes 2 and 4) or in combination with mCIITA (lane 1) or mCIITA(253–410) (lane 3). fCIITA(Δ253–410) was expressed alone (lane 6) or in combination with the same myc-tagged mutant protein (lane 5). The binding assay was performed as in (A). The expression of CIITA, CIITA(Δ253–410) and CIITA(253–410) was confirmed by SDS–PAGE (7.5 and 10% polyacrylamide, respectively) and immunoblotting with specific antibodies (middle and bottom panels). (D) Schematic representation of the interactions in vivo. Each combination of mCIITA and fCIITA proteins from (A–C) (a, b and c, respectively) is illustrated along with its ability to aggregate (+). At the top is a diagram of CIITA with its domains: AD (aa 1–144), P/S/T region (aa 163–322), GBD (aa 420–561) and LRR (aa 988–1097). The endpoints of each CIITA form are indicated. The solid box represents the minimal oligomerization domain from positions 253–321 and the hatched box represents the residues from positions 322–410, which are required for optimal oligomerization.

Residues from positions 253–410 are necessary and sufficient for the oligomerization of CIITA

To define the region required for CIITA aggregation, we first examined the ability of different C-terminal truncations of CIITA to associate with themselves. Several Myc and Flag epitope-tagged deletion mutants were constructed. The endpoints were chosen such that the deletion would remove progressively defined domains of CIITA (Figure 1Da). CIITA(1–980), CIITA(1–699) and CIITA(1–410) proteins retained the ability to oligomerize (Figure 1A, left top panel, lanes 2–4) to a similar extent as the wild-type protein. On the contrary, mCIITA(1– 410) co-precipitated small amounts of fCIITA(1–321) (Figure 1A, left top panel, lane 5). Co-precipitated proteins were not detected when mutant fCIITA proteins were co-expressed with the parental plasmid (Figure 1A, right top panel, lanes 7–10), indicating that the observed interactions were specific. These results, summarized in Figure 1Da, indicate that the first 321 residues of CIITA, encompassing AD and P/S/T sequences, contain the oligomerization domain of CIITA, but residues from positions 322–410 increase this interaction. As the LRR did not contribute to this aggregation and CIITA(1–699) behaved like the wild-type protein, this peptide was chosen for subsequent experiments.

To delineate the boundary at the N-terminus of CIITA that is required for its oligomerization, mCIITA(1–699) was co-expressed with fCIITA(322–1130) or fCIITA(253– 1130). mCIITA(1–699) co-precipitated fCIITA(253–1130) but not fCIITA(322–1130) (Figure 1B, left top panel, lanes 6 and 7), demonstrating that the sequence from positions 253–321 is critical for CIITA aggregation. Identical results were obtained when the two N-terminal deletion mutant proteins were co-expressed with mCIITA, or mCIITA(1–980) or mCIITA(1–410) (data not shown). mCIITA(1–699) was also co-expressed with fCIITA and with the entire panel of Flag epitope-tagged C-terminal deletion mutant proteins. mCIITA(1–699) co-precipitated CIITA, CIITA(1–980), CIITA(1–699) and CIITA(1–410) (Figure 1B, left top panel, lanes 1–4). Co-expression of mCIITA(1–699) with fCIITA(1–321) still formed a weak complex (Figure 1B, left top panel, lane 5), confirming that sequences from positions 253–321 must be extended at the C-terminus for the optimal aggregation of CIITA. No specific immunoprecipitations were observed when our fCIITA proteins were co-expressed with the empty vector (Figure 1B, right top panel, lanes 8–14). These results define the boundary of CIITA oligomerization to residues from positions 253–321 (Figure 1D, solid box). Residues from positions 322–410 increased this interaction (Figure 1D, hatched box). Results in Figure 1B also demonstrate that the GBD is not an aggregation domain.

To confirm that residues from positions 253–410 mediate the oligomerization of CIITA, we expressed fCIITA(253–410) with mCIITA or mCIITA(253–410). fCIITA(253–410) was detected as two electrophoretically distinct forms and the upper form was co-precipitated by mCIITA and mCIITA(253–410) (Figure 1C, top panel, lanes 1 and 3). To confirm the requirement of residues from positions 253–410 for this oligomerization, mutant CIITA proteins lacking this sequence were made and examined for their ability to aggregate. No specific inter action between these proteins was observed (Figure 1C, top panel, lane 5). Finally, cell lysates containing fCIITA(253–410) were subjected to gel-filtration chromatography. In addition to monomers, fCIITA(253–410) dimers were observed (data not shown). We conclude that residues from positions 253–410 are necessary and sufficient for the optimal oligomerization of CIITA.

Temperature-dependent oligomerization of CIITA in vitro

To determine whether this interaction between CIITA in vivo could also be observed in vitro, we performed pull-down experiments with proteins that were expressed from the coupled transcription and translation reaction using the rabbit reticulocyte lysate in vitro (in vitro translation, IVT). mCIITA and fCIITA, expressed in vitro, failed to oligomerize (Figure 2, lane 1), suggesting that critical modifications were required for this interaction. Remark ably, when IVT reactions were performed at 30°C and incubated at 37°C before the immunoprecipitation, these proteins bound each other (Figure 2, lane 4). Taken together, these results indicate that CIITA oligomerization is an active process that involves a post-translational modification of the protein. This modification occurs under physiological conditions in cells and can be achieved at 37°C in vitro.

Fig. 2. Incubation at 37°C restores the ability of CIITA to oligomerize in vitro. fCIITA and mCIITA were expressed from IVT at 30°C, alone or in combination (lanes 1 and 4), and then incubated at 37°C for 2 h (lanes 4–6) or kept on ice (lanes 1–3). Proteins were immunoprecipitated with the anti-Myc antibody and examined for the presence of fCIITA by anti-Flag immunoblotting; 5% of the pre-cleared IVT reactions were analyzed for the presence of fCIITA and mCIITA by immunoblotting (middle and bottom panels).

Wild-type CIITA and deletion mutant CIITA proteins containing the oligomerization domain are phosphorylated in vivo

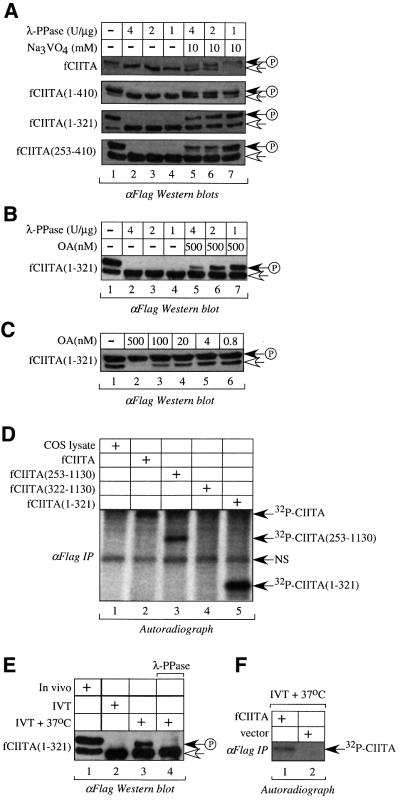

On the basis of the mobility shifts in SDS–PAGE and binding results in vivo and in vitro, we hypothesized that among the post-translational modifications, phosphorylation could play a role in the oligomerization of CIITA. To test this hypothesis, we first verified whether CIITA, and in particular its N-terminal sequence, are phosphorylated in vivo. fCIITA, fCIITA(1–410), fCIITA(1–321) and fCIITA(253–410) were expressed in COS cells and cell extracts were analyzed by anti-Flag immunoblotting. We found that CIITA and its deletion mutant proteins were expressed as two forms with different mobilities (Figure 3A, lane 1). Of note, for each CIITA protein, the upper, slower migrating polypeptide species was the predominant one. To determine whether these electrophoretic mobility changes were the result of phosphorylation, cell extracts were treated with increasing amounts of λ-phosphatase (λ-PPase) and analyzed. λ-PPase removes phosphates from serines, threonines and, to a lesser extent, tyrosines. λ-PPase treatment caused a dramatic shift in the migration pattern of CIITA. It abolished the higher- and increased the lower-molecular-weight forms (Figure 3A, lanes 2–4). This effect was reversed by co-incubating treated extracts with the phosphatase antagonist sodium orthovanadate (Figure 3A, lanes 5–7), indicating that the shift was caused by the phosphorylation of CIITA. In addition, the reappearance of the hyperphosphorylated form after sodium orthovanadate treatment was inversely correlated with the amount of λ-phosphatase used (Figure 3A, compare lane 5 with 7 in various panels). These data demonstrate that CIITA, CIITA(1–410), CIITA(1–321) and CIITA(253–410) are phosphorylated in vivo and indicate that the overlapping sequence from positions 253–321 contains the phosphorylation sites. It is of particular interest that this sequence overlaps the oligomerization domain of CIITA. Treatment of COS cell extracts, expressing fCIITA(1–321), with PTP1b, a phosphotyrosine phosphatase, did not alter the mobility of any band (data not shown). The effect of λ-PPase was reversed not only by treatment with sodium orthovanadate, but also with okadaic acid (OA), a specific inhibitor of cellular S/T phosphatases (Figure 3B). As the segment from positions 253–321 of CIITA contains nine serines and eight threonines, the results are compatible with the phosphorylation of these residues and the observed shift in the migration pattern of CIITA.

Fig. 3. CIITA is a phosphoprotein. (A) λ-PPase treatment reveals that the self-interaction domain is phosphorylated in vivo. COS cell extracts containing fCIITA, fCIITA(1–410), fCIITA(1–321) and fCIITA(253– 410) were treated with various amounts of λ-PPase (U/µg cell extract) alone or in combination with 10 mM sodium orthovanadate, as indicated at the top, and then separated by SDS–PAGE (5, 6, 7.5 and 10%, respectively). Blots were probed with the anti-Flag antibody. Lane 1 corresponds to the untreated extracts. The white arrow indicates the faster migrating form; the black arrow with the circled ‘P’ indicates the slower migrating phosphorylated form. (B) OA blocks in vitro λ-PPase activity and restores the upper phosphorylated form of fCIITA(1–321). The lysate of COS cells expressing fCIITA(1–321) was treated with different amounts of λ-PPase (lanes 2–4) or λ-PPase plus 500 nM OA (lanes 5–6) and then analyzed by anti-Flag immunoblotting. Lane 1 corresponds to the untreated extract. Arrows are as in (A). (C) OA prevents the dephosphorylation of fCIITA(1–321) in vivo. COS cells expressing fCIITA(1–321) were treated for 2 h with the indicated amounts of OA (lanes 2–6) and then analyzed by anti-Flag western blotting. Lane 1 corresponds to the untreated extract. Arrows are as in (A). (D) Autoradiograph of anti-Flag-immunoprecipitated wild-type and mutant forms of CIITA from [32P]orthophosphate-labeled COS cells. Migration positions of [32P]CIITA proteins are indicated on the right. NS indicates a non-specific radiolabeled band, which was also present in the lysate of untransfected COS cells (lane 1). (E) Temperature-dependent phosphorylation of CIITA(1–321) in vitro. fCIITA(1–321) was expressed in COS cells (lane 1) or produced from IVT (lane 2). An aliquot of IVT was incubated at 37°C for 2 h and then either left untreated (lane 3) or treated with 12.5 U of λ-PPase at 30°C for 2 h (lane 4). Anti-Flag immunoblotting is shown. (F) In vitro phosphorylation assay. IVTs containing fCIITA (lane 1) or pcDNA3 vector (lane 2) were assayed for phosphorylation. Proteins were analyzed by anti-Flag immunoblotting (data not shown) or by autoradiography. The arrow indicates the phosphorylated CIITA.

These results suggest that steady-state levels of CIITA phosphorylation are determined by a dynamic equilibrium between kinases and phosphatases in COS cells. To investigate this finding further, we analyzed the effects of OA in intact COS cells expressing fCIITA(1–321). At 500 nM OA (Figure 3C, lane 2), only the slower migrating phosphorylated form was detected by anti-Flag immunoblotting, indicating that CIITA is dephosphorylated by an OA-sensitive S/T phosphatase in COS cells. To obtain more direct evidence of CIITA phosphorylation in vivo, COS cells were transfected with expression vectors for fCIITA, fCIITA(253–1130), fCIITA(322–1130) or fCIITA(1–321), which were labeled metabolically with [32P]orthophosphate. The expression of CIITA proteins was evaluated as above (data not shown). Autoradio graphy of CIITA proteins precipitated by anti-Flag– agarose beads revealed that CIITA, CIITA(253–1130), CIITA(1–321), but not CIITA(322–1130), were phosphorylated in vivo (Figure 3D, lanes 2–5). Taken together, these observations indicate that a kinase targets residues from positions 253–321 in the P/S/T region of CIITA in COS cells.

The finding that CIITA is phosphorylated in the first 321 residues in vivo raised the interesting possibility that the same phosphorylation events could occur in vitro at 37°C but not at 30°C. We compared the migration patterns of fCIITA(1–321) from IVT with those from COS cells. Indeed, the upper phosphorylated form was detected in the cell lysates but was absent from the IVT (Figure 3E, lanes 1 and 2). However, the incubation of the IVT reaction at 37°C changed the electrophoretic mobility of CIITA and restored the upper phosphorylated band (Figure 3E, lane 3). This effect was reversed by treatment with λ-PPase (Figure 3E, lane 4). We conclude that the phosphorylation of CIITA is temperature dependent. Furthermore, our results correlated the phosphorylation (Figure 3E) with the ability of CIITA to oligomerize at 37°C in vitro (Figure 2). To confirm that CIITA is phosphorylated in vitro, an in vitro phosphorylation assay was also performed. fCIITA produced from the IVT was incubated at 37°C in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP and then isolated with anti-Flag–agarose beads. After SDS–PAGE and autoradiography, CIITA was detected as a 32P-labeled protein (Figure 3F, lane 1). Thus, CIITA is phosphorylated in vitro at 37°C.

Phosphorylation-dependent oligomerization of CIITA regulates its transcriptional activity

To demonstrate that CIITA oligomerization depends on its phosphorylation, cell extracts of COS cells, which co-expressed fCIITA and mCIITA, were treated with λ-PPase and then analyzed for their ability to form complexes (Figure 4A, lanes 4–6). CIITA aggregation, which was observed with the untreated cell lysates (Figure 4A, lanes 1 and 10), was abrogated by phosphatase treatment (Figure 4A, lane 4) and was restored by the co-incubation of λ-PPase with sodium orthovanadate (Figure 4A, lane 7). We conclude that CIITA oligomerization depends on its phosphorylation.

Fig. 4. Phosphorylation is critical for CIITA oligomerization and activity. (A) λ-PPase treatment abrogates CIITA self-association. COS cell extracts, containing fCIITA and mCIITA or either one of the two proteins, were treated with λ-PPase (2 U/µg) (lanes 4–6), λ-PPase plus sodium orthovanadate (10 mM) (lanes 7–9), λ-PPase reaction buffer (lanes 10–12) or left untreated (lanes 1–3). Anti-Myc-immunoprecipitated proteins were run on 7.5% acrylamide gel and probed with anti-Flag antibody (top panels). Protein expression was confirmed by immunoblotting (middle and bottom panels). (B) OA treatment in vivo increases CIITA oligomerization. COS cells expressing fCIITA and mCIITA were treated with 250 nM OA for 2 h before the harvesting (lane 1) or left untreated (lane 2). Lane 3 corresponds to cells expressing fCIITA only. Cell lysates were normalized to protein concentration and analyzed for CIITA interaction as described in (A) (top panel) or for expression by immunoblotting (middle and bottom panels). (C) OA treatment in vivo increases CIITA activity. COS cells were co-transfected with CAT-reporter and -effector plasmids, as indicated, and treated for 9 h before cell harvesting with 125 or 250 nM OA (black bars) or left untreated (hatched bars). White bars represent co-transfection of the reporter plasmid with pcDNA3 (left panel) or pSG424 (middle and right panels). The activity of the empty plasmid was not increased by OA treatment (data not shown). Two days after the transfection, CAT activity of cellular extracts normalized to protein concentration was determined. Fold activation represents values from experiments with co-expressed protein effector over those obtained with the plasmid reporter alone. CAT enzymatic activities represent the mean value of three independent experiments performed in triplicate with indicated standard errors of the mean.

Since CIITA aggregation was inhibited by phosphatase treatment in vitro, inhibiting a phosphatase activity should result in enhanced CIITA oligomerization in vivo. Thus, the degree of CIITA oligomerization was analyzed in COS cells before and after treatment with OA. As expected, OA treatment increased CIITA aggregation by 4- to 5-fold (Figure 4B, top panel, compare lane 1 with 2). The amount of detectable CIITA was also increased (Figure 4B, middle and bottom panels, compare lane 1 with 2 and 3).

To examine the relevance of these results, we performed functional studies in cells. fCIITA was expressed and examined for its ability to activate a CAT reporter gene under the control of the DRA promoter in COS cells. CAT activities were measured in extracts of untreated and OA-treated cells. We found that OA increased the activity of CIITA in a dose-dependent fashion (Figure 4C, left panel). At higher concentrations of OA, this activation was increased 3-fold (Figure 4C, left panel, compare bar 2 with 4). Interestingly, this activity paralleled the increased CIITA oligomerization after treatment with OA in vivo (Figure 4B). We conclude that OA treatment increases MHCII transcription by CIITA.

To demonstrate that the effect of OA treatment on promoter activation by CIITA was independent of all other factors that regulate MHCII transcription, we co-expressed CIITA fused to the GAL4 DNA-binding domain (GalCIITA) with pG5bCAT, which contains five binding sites for the Gal4 protein upstream of a TATA box linked to the CAT reporter gene (Figure 4C, middle panel). Similarly to the results obtained for CIITA on the DRA promoter, OA treatment increased the ability of GalCIITA to transactivate pG5bCAT. At the dose of 250 nM, a 3-fold-increased GalCIITA activity was observed (Figure 4C, middle panel, compare bar 2 with 4). To demonstrate that this increased transcriptional activity by OA was specific for CIITA, COS cells were co-transfected with pG5bCAT and GalVP16, and treated with OA. No significantly increased CAT activity was observed (Figure 4C, right panel). We conclude, therefore, that the effect of OA treatment is specific for CIITA and independent of other MHCII promoter elements.

CIITA is mostly unphosphorylated and inactive in U937 cells, but its activity is increased by PMA treatment

The results presented above suggested that the activity of CIITA is regulated by protein phosphorylation and dephosphorylation, through unidentified S/T protein kinase(s) and phosphatase(s). As CIITA plays a major role in regulating MHCII transcription and thus antigen presentation by the immune system, it was important to evaluate whether phosphorylation was similarly involved in the stability and function of CIITA in cells of the monocyte/macrophage lineage, which are professional antigen-presenting cells. U937, a human promonocytic cell line, was chosen. These cells are relatively undifferentiated, do not express CIITA and MHCII determinants, and respond poorly to IFNγ.

To study CIITA phosphorylation and its functional consequences in U937 cells, we established a panel of cell lines that expressed fCIITA constitutively. fCIITA was detected in U937 cells as two major bands and its faster migrating form was the most abundant (Figure 5A, lane 1). Of particular interest, the relative abundance of the two electrophoretically distinct forms was inverted in U937 cells compared with COS cells (Figure 5A, compare lane 1 with 3).

Fig. 5. The predominantly unphosphorylated exogenous CIITA correlates with the low abundance of MHCII determinants on the surface of U937 cells. (A) U937 cells, which stably expressed fCIITA, were analyzed for the expression of CIITA by anti-Flag immunoprecipitation and anti-CIITA immunoblotting of total cell lysates (lane 1). In COS cells, transient expression of fCIITA was checked by anti-CIITA immunoblotting (lane 3). In lanes 2 and 4 are the analyses of U937 and COS cells, respectively, transfected with pcDNA3. Proteins were separated on 5% SDS–PAGE. Arrows indicate the two forms with different mobilities; the black arrow indicates the phosphorylated form. (B) PMA increases MHCII expression in U937/fCIITA cells. U937 cells transfected with pcDNA3 (U937) or with the plasmid coding for fCIITA (U937/fCIITA) were analyzed by FACS for the expression of MHC proteins listed at the top of the figure, before and after treatment with 100 ng/ml PMA for 24 h. The analysis was carried out on bulk cultures, which had been selected for antibiotic resistance for at least 5 weeks. The gray histograms represent the background staining with the FITC-conjugated secondary reagent. Numbers in each panel indicate the mean fluorescence intensity expressed as arbitrary units (a.u.).

To determine whether fCIITA in U937 cells could rescue the expression of MHCII determinants, cell surface analysis was carried out by immunofluorescence and flow cytometry. Approximately 3- and 4-fold increased expression of HLA-DR and -DP, respectively, was found (Figure 5B, compare h with b, and i with c). It must be underlined that the rescue of MHCII gene expression in various U937/fCIITA cells was generally low, and in some cases not detectable (see below). Expression of HLA-A,B,C was not altered, if not slightly decreased in U937/fCIITA cells (Figure 5B, compare g with a). We conclude that the expression of exogenous fCIITA slightly increased the expression of MHCII genes in U937 cells.

U937 cells are not yet fully differentiated monocytes. They undergo terminal differentiation to macrophages following induction with a variety of stimuli, such as vitamin D3, retinoic acid and PMA, a potent activator of protein kinase C. To examine whether the expression of MHCII molecules in U937/fCIITA cells was affected by PMA, cell surface analysis was performed after 24 h of treatment. Remarkably, U937/fCIITA cells demonstrated a 10- and 4-fold increased expression of HLA-DR and -DP, respectively, over that observed with untreated cells (Figure 5B, compare k with h, and l with i). In sharp contrast, PMA treatment did not alter the expression of MHCII determinants in mock-transfected U937 cells (Figure 5B, compare e with b, and f with c) and of MHCI determinants in U937/fCIITA and in U937 control cells (Figure 5B, compare j with g, and d with a).

Phosphorylation increases the accumulation of CIITA in U937 cells and results in increased expression of MHCII genes

To investigate whether PMA-mediated upregulation of MHCII molecules correlated with increased phosphorylation of CIITA, we performed a kinetic study of the expression and phosphorylation status of fCIITA in U937 cells stimulated with PMA over a 6 h period. As previously presented in Figure 5A (lane 1), in untreated cells (time = 0), CIITA was detected as a doublet in a predominant high mobility form (Figure 6A, lane 1). Upon stimulation with PMA for 15 min, the relative abundance of the two forms was inverted with an increase in the upper phosphorylated form (Figure 6A, lanes 1 and 2). Interestingly, as early as 30 min after PMA induction, the overall expression of fCIITA was increased, reaching a maximum after 2 h (Figure 6A, lanes 3–6). At this time, 1/250 (5 µl) of the total cell lysate used for the immunoprecipitation was sufficient for the detection of CIITA by immunoblotting (Figure 6A, bottom panel). Furthermore, the majority of CIITA was in the phosphorylated form. We then assessed whether 2 h of PMA treatment were sufficient to increase MHCII expression in U937/fCIITA cells. Cell surface analysis of U937 cells, which expressed CIITA (Figure 6A, lane 1), but not MHCII molecules (Figure 6B, compare e with b, and f with c), was performed. PMA treatment produced approximately a 30- and 20-fold increased expression of HLA-DR and -DP, respectively (Figure 6B, compare h with e, and i with f). The expression of HLA-A,B,C was not changed (Figure 6B, compare g with d). We conclude that PMA induced a rapid phosphorylation and an impressive accumulation of CIITA, which correlated with the increased expression of MHCII determinants.

Fig. 6. PMA and OA treatments increase the levels of CIITA and MHCII determinants in U937/fCIITA cells. (A) PMA induction of U937/fCIITA cells. U937/fCIITA cells (1 × 108) were treated with 100 ng/ml PMA for 15 min, 30 min, 1 h, 2 h and 6h. At each time point, cell extracts were prepared and immunoprecipitated with the anti-Flag M2–agarose beads. Precipitated proteins were run on 5% acrylamide gels and probed with the anti-CIITA antibody (lanes 1–6). After 2 h of PMA treatment, three aliquots (5, 10 and 20 µl) of the whole-cell extract were also analyzed by anti-Flag immunoblotting (lanes 7–9). The arrows indicate CIITA as described in Figure 5A. (B) Treatment with PMA or OA for 2 h is sufficient to induce maximal expression of MHCII molecules in U937/fCIITA cells. MHCI and II expression was evaluated after 2 h treatment with 100 ng/ml PMA (g–i) or 250 nM OA (j–l) in U937/fCIITA cells. After stimulation, cells were washed extensively and kept in culture for an additional 22 h before the analysis. (a–c) refer to U937 cells transfected with pcDNA3. (d–f) refer to unstimulated U937/fCIITA cells. The gray histograms indicate background staining obtained with the FITC-conjugated secondary antibody. Numbers in each panel indicate the mean fluorescence intensity. (C) The OA time-course analysis in U937/fCIITA cells. Total cell lysates of 1 × 108 cells treated with 250 nM OA for the times indicated at the top of the blot were immunoprecipitated with the anti-Flag M2–agarose beads and analyzed by 5% SDS–PAGE and anti-CIITA immunoblotting.

To explore whether the inhibition of a phosphatase might produce a similar effect, U937/fCIITA cells were treated with OA and analyzed for the expression of CIITA and MHCII determinants over time. Expression levels of fCIITA gradually increased over the 6 h time course (Figure 6C). The kinetics of accumulation were similar, although not superimposable, to those observed after PMA treatment. After 30 min, fCIITA increased, reaching a maximum at 6 h of treatment (Figure 6C, lanes 1–6). Thus, the inhibition of a pre-existing phosphatase activity in cells resulted in the accumulation of CIITA similar to that by the activation of a kinase. The flow cytometric analyses of U937/fCIITA cells treated for 2 h with OA revealed 16- and 10-fold increased expression of HLA-DR and -DP, respectively (Figure 6B, compare k with e, and l with f). No variation in the expression of MHCII determinants was observed with the mock-transfected cells (data not shown). The expression of MHCI determinants was not affected by OA (Figure 6B, compare j with d). We conclude that OA not only induced an increased accumulation of CIITA, but also stimulated its transcriptional activity on MHCII promoters. An effect of PMA and OA on the CMV promoter driving the expression of fCIITA was ruled out by the lack of increased β-galactosidase activity in CMVβGal-transfected U937 cells after PMA or OA treatment (data not shown). Interestingly, effects of PMA and OA on CIITA expressed in U937 cells closely resemble those of OA treatment in COS cells, where the inhibition of a phosphatase activity increased the phosphorylation of CIITA, its oligomerization, accumulation and, more importantly, its functional activity (Figure 4).

PMA treatment causes an increased accumulation of CIITA both in the cytoplasm and nucleus of U937/fCIITA cells

To determine the localization of CIITA, we performed subcellular fractionation and immunofluorescence experiments in U937/fCIITA cells before and after PMA stimulation. In untreated cells, fCIITA was precipitated in the total and in the cytoplasmic cell lysate but was undetectable in the nuclear fraction (Figure 7A, top panel, lanes 1–3). By immunofluorescence, fCIITA was shown to be confined to the cytoplasm (Figure 7B, middle panel). After PMA stimulation, CIITA was present abundantly in the cytoplasm and nucleus, as shown by subcellular fractionation (Figure 7A, second panel, lanes 2 and 3) and immunofluorescence of intact cells (Figure 7B, bottom panel). These results are consistent with the increased transcription from MHCII promoters and increased expression of MHCII molecules in U937/fCIITA cells after PMA treatment.

Fig. 7. Localization of CIITA protein in U937/fCIITA cells. (A) Subcellular fractionation. The presence of fCIITA in the total (T), cytoplasmic (C) and nuclear (N) cell extracts of untreated U937/fCIITA cells was demonstrated by anti-Flag immunoprecipitation followed by 7.5% SDS–PAGE and anti-CIITA (top panel), or anti-Flag immunoblotting in PMA-stimulated cells (second panel). U937 total cell lysate (lane 4) was included as the negative control. Equal amounts (in µg) of lysate from each fraction were used. Anti-β-adaptin and anti-p34Cdc2 immunoblotting were performed to control for cytoplasmic and nuclear fractionation (third and bottom panels, respectively). (B) Immunofluorescence. Untreated (middle panel) or PMA-treated (bottom panel) U937/fCIITA cells were stained with FITC-conjugated anti-Flag M2 antibody. U937-untransfected cells were analyzed to assess the background fluorescence (top panel). Representative fields are presented. Scale bar = 5 µm.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that CIITA oligomerizes in vivo and in vitro. N-terminal residues from positions 253–321 were required minimally for this aggregation. Moreover, the oligomerization depended on the S/T phosphorylation of this sequence, which correlated with the increased accumulation of the protein and its increased activity on MHCII promoters. Importantly, this observation was also confirmed in U937 cells upon their activation and differentiation with exogenous stimuli, like PMA. We conclude that this post-transcriptional modification of CIITA is critical for its activity in cells.

Recent investigations confirmed this oligomerization of CIITA in vivo (Kretsovali et al., 2001; Linhoff et al., 2001; Sisk et al., 2001). However, our study was designed to find the minimal surface that could aggregate under the most stringent conditions. Indeed, a minimal peptide from positions 253–410 bound itself and formed minimally homodimers by gel-filtration chromatography. Moreover, the deletion of this sequence was sufficient to prevent the oligomerization of CIITA in cells (Figure 1C). Furthermore, we could exclude contributions of LRR, GBD and AD sequences from this oligomerization. As suggested previously, these regions most likely contribute to intra- rather than inter-molecular associations of CIITA (Linhoff et al., 2001). Since our study also demonstrated that the phosphorylation of residues between positions 253 and 410 was required for this aggregation, we conclude that this modification may alter the conformation of CIITA, allowing for optimal oligomerization in vivo and in vitro (Figures 1–3).

The precise residues that are phosphorylated were not identified. Nine serines, eight threonines and one tyrosine are found between positions 253 and 321 in CIITA. They conform to many different consensus phosphorylation sites. Therefore, it is possible that many different kinases, and thus signaling cascades, could phosphorylate this region with similar outcomes. We can only exclude protein kinase A, which phosphorylates residues at the C-terminus of CIITA and negatively affects the activity of the protein (Li et al., 2001).

In COS cells, CIITA is phosphorylated constitutively. This finding explains its aggregation and activity in these cells. In contrast, exogenous CIITA is mostly unphosphorylated in U937 cells, which represent immature monocytes. Despite exogenous expression of CIITA, low expression of MHCII determinants was observed on the surface of these cells. However, upon the activation and differentiation of U937 cells by PMA, CIITA became heavily phosphorylated. Although the activity of the promoter that directed the expression of CIITA remained unchanged and CIITA transcripts lacked endogenous 5′ and 3′ ends, levels of CIITA rose quickly and dramatically in the cytoplasm and nucleus of these cells. This increase was accompanied by the abundant expression of MHCII determinants on the surface of U937 cells. These findings connect oligomerization, phosphorylation and activity of CIITA in a physiologically relevant setting, where monocytes have to differentiate to macrophages for optimal antigen processing and presentation. It is tempting to speculate that one of the signals involved in this activation of monocytes, which results in the phosphorylation of CIITA, could be via receptors of the innate immune system, which would then activate the first steps of the adaptive immune system.

The theme of differential phosphorylation and activity of transcription factors is not new. Many signaling cascades converge on the activation of NF-κB, STAT, NF-AT and AP-1 complexes, which depend on these post-transcriptional modifications for nuclear localization and transcriptional activity (Darnell et al., 1997; Karin et al., 1997; Crabtree, 1999). A particularly interesting example is ATF2 transcription factor, whose stability is regulated by a phosphorylation-dependent dimerization (Fuchs et al., 2000). Moreover, in the case of cJun, differential phosphorylation leads to its activation and inactivation (Karin et al., 1997), a scenario that could be similar to the activation of CIITA via PMA and its PKA-mediated inactivation by prostaglandins and cAMP (Li et al., 2001). These post-translational modifications also make CIITA an attractive target for manipulating the immune system. For example, one can envisage using mutant CIITA proteins that mimic its phosphorylated state to augment immune responses in vaccinations, immunodeficiencies and neoplastic diseases. Alternatively, blocking the phosphorylation of CIITA could contribute to the treatment of autoimmune diseases.

Materials and methods

Cell cultures and treatments

COS cells and U937, a human promonocytic cell line, were grown in DMEM and RPMI, respectively, supplemented with 10% FBS and 5 mM l-glutamine. For phosphorylation studies in vivo, cells were treated with 100 ng/ml PMA (Sigma) or OA (Calbiochem) at the amounts indicated in the text. Dephosphorylation of cell extracts was performed by incubating with λ-PPase (New England BioLabs) at 30°C for 2 h at the amounts indicated in the text.

Plasmids

fCIITA pcDNA3 vector (FLAG.CIITA8) (Chin et al., 1997) was a gift from J.Ting. mCIITA cDNA was cloned into pcDNA3 EcoRI site (pCmCIITA) (S.Kanazawa, unpublished data). All CIITA deletion mutants were generated from FLAG.CIITA8 and pcmCIITA. To create pcfCIITA(1–980), fCIITA cDNA was excised by EcoRI and inserted into EcoRI-cleaved pcDNA3 vector (Invitrogen), killed at the BamHI site. The ligation product was digested with BamHI–XbaI, filled in and religated to create a stop codon after the BamHI site in CIITA. pcmCIITA(1– 980) was made by digesting pcmCIITA with KpnI. The resulting 2.4 kb fragment was subcloned into KpnI-digested pcfCIITA(1– 980). pcfCIITA(1–699) and pcmCIITA(1–699) were made by digesting the parental vectors with SacII–XbaI, filling in and religation. pcfCIITA(1–410) and pcmCIITA(1–410) were made by digestion of the parental vectors with NotI and religation. pcfCIITA(1–321) was made by PCR with the primers F1 (5′-GGGGGGAATTCGCCACCATGG ACTACAAGGACGACGACGACAAGGCACGTTGCCTGGCTCCAC GCCCTGCTGGG) and 321R (5′-GGGGGCTCGAGTCAGCATTGGGTGGGGGACGTCTTGTGC), and ligation into EcoRI–XhoI-cleaved pcDNA3 vector. pcfCIITA(253–1130) and pcfCIITA(322–1130) were made by PCR with primers F253 (5′-GGGGGGAATTCGCCACCAGTGAGG) and F322 (5′-GGGGGGAATTCACAATGGACTACAAGGACGACGACGACAAGCCGGCAGCTGGAGAGGTCTCC), respectively, and the common primer 1130R (5′-CGATGCTCTAGATCATCTCAGGCTGATCCGTGA). PCR products were ligated into EcoRI– XbaI-cleaved pcDNA3. pcfCIITA(253–410) was made by digesting pcfCIITA(253–1130) with NotI–XbaI, filling in and religation. pcmCIITA(253–410) was made by inserting the PCR fragment (primers M253, 5′-GGGGGGAATTCGCCACCATGGAGCAGAAGCTGATCTCCGAGGAGGACCTGATATTCATCTACCATGGTGAGG; and 410R, 5′-GGGGGCTCGAGTCACGGCCGCCGGTGCTCCTTGGCAGCCAACAGC) into EcoRI–XhoI-cleaved pcDNA3 vector. To make pcfCIITA(Δ253–410) and pcmCIITA(Δ253–410), the sequence corresponding to aa 1–252 of CIITA was PCR amplified with the F1 (see above) and the M1 (5′-GGGGGGAATTCGCCACCATGGAGCAGAAGCTGATCTCCGAGGAGGACCTGCGTTGCCTGGCTCCACGCCCTGCTGG) primers, respectively, containing EcoRI site and the 252R (5′-GGGGGGCGGCCGCACTGGAGACCCCTGTTCCAGCCTCAGAG) reverse primer containing NotI site. PCR products were subcloned into EcoRI–NotI-cleaved pcfCIITA(322–1130). The resulting plasmids were subjected to mutagenesis using the QuikChange XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene), the mutagenic primer (Δ253–410) 5′-GGGGTCTCCAGTCGTGAGACACGA and its complementary primer. This resulted in an internal deletion of CIITA, which fuses the sequence 1–252 to sequence 411–1130. All plasmids were sequenced to verify identity. pDRASCAT, GalCIITA (pSGCIITA), pG5bCAT, pSG424 and Gal-VP16 plasmids were described previously (Fontes et al., 1999; Nekrep et al., 2000).

Transient transfections, immunoprecipitation and western blotting

COS cells were transfected with 6 µg of total DNA using Lipofectamine (Life Technologies) and lysed 24 h after transfection with lysis buffer (1% NP-40, 10 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 0.1% protease inhibitors) for 45 min on ice. Protein concentration was measured by Bradford assay. Pre-cleared cell lysates were immunoprecipitated overnight at 4°C with the rabbit polyclonal anti-Myc antibody (Santa Cruz Biotech) and protein A–Sepharose beads. The complexes were washed five times with the lysis buffer and once with the lysis buffer containing 500 mM NaCl. Precipitated proteins were resolved on SDS–PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Flag M2 monoclonal antibody (Sigma) followed by HRP-conjugated sheep anti-mouse Ig. Anti-Myc immunoblotting was performed with monoclonal antibody 9E10 (Santa Cruz Biotech). Blots were developed by chemiluminescence assay (NEN Life Science Products).

In vitro transcription and translation, and in vitro phosphorylation assay

fCIITA and mCIITA were expressed in vitro by using the TnT T7 coupled rabbit reticulocyte lysate transcription and translation system (Promega). For the phosphorylation assay, fCIITA produced in vitro was incubated at 37°C for 2 h in the presence of 10 µCi of [γ-32P]ATP. IVT proteins were immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag M2–agarose beads (Sigma) and resolved by 7.5% SDS–PAGE. Phosphorylated bands were visualized by autoradiography.

Enzyme activity assays

CAT assays were performed as described previously (Nekrep et al., 2000).

Stable transfection and FACS analysis

U937 cells were transfected by electroporation and analyzed by FACS with the anti-HLA-A,B,C (B9.12.1), anti-HLA-DR (D1.12) and anti-HLA-DP (B7.21) antibodies, as described previously (Tosi et al., 2000). Transfected cells were selected and cultivated with 500 µg/ml neomycin (Gibco, BRL) and assayed for the presence of fCIITA by immunoprecipitation with anti-Flag M2–agarose beads, followed by immunoblotting with rabbit serum raised against the first 321 aa of CIITA.

Subcellular localization of CIITA

Nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts were prepared as described previously (Bovolenta et al., 1999). Immunofluorescence experiments were performed on cytospins of U937 cells fixed with cold methanol:acetone (1:1) for 10 min. Cells were incubated with 1% PBS–BSA for 1 h and then with FITC-conjugated anti-Flag M2 antibody (Sigma) for 1 h at 37°C. The localization of CIITA was analyzed by an Olympus BX60 microscope at 100× magnification.

In vivo labeling with [32P]orthophosphate

COS cells were washed, 24 h after transfection, with phosphate-free DMEM medium, incubated for 1 h at 37°C with phosphate-free medium plus 10% dialyzed FCS and for 3 h with 1 mCi/ml [32P]orthophosphate. Cells were washed extensively with phosphate-free medium containing 0.5 mM Na3VO4 and 25 nM OA, and lysed with lysis buffer containing 5 mM Na3VO4 and 250 nM OA.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Roberto Accolla, Nada Nekrep, Elisabetta Pilotti and members of the laboratory for technical help and comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by the Nora Eccles Treadwell Foundation and by the Istituto Superiore di Sanità (I.S.S.) National Research Project on AIDS n. 40.C.1.

References

- Accolla R.S. (1983) Human B cell variants immunoselected against a single Ia subset have lost expression of several Ia antigen subsets. J. Exp. Med., 157, 1053–1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Accolla R.S., Jotterand-Bellomo,M., Scarpellino,L., Maffei,A., Carra,G. and Guardiola,J. (1986) aIr-1, a newly found locus on mouse chromosome 16 encoding a trans-acting activator factor for MHC class II gene expression. J. Exp. Med., 164, 369–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benoist C. and Mathis,D. (1990) Regulation of major histocompatibility complex class II genes: X, Y and other letters of the alphabet. Annu. Rev. Immunol., 8, 681–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovolenta C., Lorini,A.L., Mantelli,B., Camorali,L., Novelli,F., Biswas,P. and Poli,G. (1999) A selective defect of IFN-γ- but not of IFN-α-induced JAK/STAT pathway in a subset of U937 clones prevents the antiretroviral effect of IFN-γ against HIV-1. J. Immunol., 162, 323–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calman A.J. and Peterlin,B.M. (1987) Mutant human B cell lines deficient in class II major histocompatibility complex transcription. J. Immunol., 139, 2489–2495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caretti G., Cocchiarella,F., Sidoli,C., Villard,J., Peretti,M., Reith,W. and Mantovani,R. (2000) Dissection of functional NF-Y-RFX cooperative interactions on the MHC class II Ea promoter. J. Mol. Biol., 302, 539–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C.H., Fontes,J.D., Peterlin,M. and Flavell,R.A. (1994) Class II transactivator (CIITA) is sufficient for the inducible expression of major histocompatibility complex class II genes. J. Exp. Med., 180, 1367–1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin K.C., Li,G.G.X. and Ting,J.P.Y. (1997) Importance of acidic, proline/serine/threonine-rich, and GTP-binding regions in the major histocompatibility complex class II transactivator: generation of transdominant-negative mutants. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 2501–2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabtree G.R. (1999) Generic signals and specific outcomes: signaling through Ca2+, calcineurin and NF-AT. Cell, 96, 611–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnell J.E. Jr, (1997) STATs and gene regulation. Science, 277, 1630–1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Sandro A.M., Nagarajan,U.M. and Boss,J.M. (2000) Association and interactions between bare lymphocyte syndrome factors. Mol. Cell. Biol., 20, 6587–6599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontes J.D., Kanazawa,S., Jean,D. and Peterlin,B.M. (1999) Interactions between the class II transactivator and CREB binding protein increases transcription of major histocompatibility complex class II genes. Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 941–947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs S.Y., Tappin,I. and Ronai,Z. (2000) Stability of ATF2 transcription factor is regulated by phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 12560–12564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germain R.N. (1994) MHC dependent antigen processing and peptide presentation: providing ligands for lymphocyte activation. Cell, 76, 287–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladstone S.D. and Pious,D. (1978) Stable variants affecting B cell alloantigens in human lymphoid cells. Nature, 271, 459–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glimcher L.H. and Kara,C.J. (1992) Sequences and factors: a guide to MHC class II transcription. Annu. Rev. Immunol., 10, 13–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griscelli C., Lisowska-Grospierre,B. and Mach,B. (1989) Combined immunodeficiency with defective expression in MHC class II genes. Immunodefic. Rev., 1, 135–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hake S.B., Masternak,K., Kammerbauer,C., Janzen,C., Reith,W. and Steimle,V. (2000) CIITA leucine-rich repeats control nuclear localization, in vivo recruitment to the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II enhanceosome, and MHC class II gene transactivation. Mol. Cell. Biol., 20, 7716–7725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harton J.A., Cressman,D.E., Chin,K.C., Der,C.J. and Ting,J.P. (1999) GTP binding by class II transactivator: role in nuclear import. Science, 285, 1402–1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanazawa S., Okamoto,T. and Peterlin,B.M. (2000) Tat competes with CIITA for the binding to P-TEFb and blocks the expression of MHC class II genes in HIV infection. Immunity, 12, 61–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karin M., Liu,Z. and Zandi,E. (1997) AP-1 function and regulation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol., 9, 240–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kretsovali A., Agalioti,T., Spilianakis,C., Tzortzakaki,E., Merika,M. and Papamatheakis,J. (1998) Involvement of CREB binding protein in expression of major histocompatibility complex class II genes via interaction with the class II transactivator. Mol. Cell. Biol., 18, 6777–6783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kretsovali A., Spilianakis,C., Dimakopoulos,A., Makatounakis,T. and Papamatheakis,J. (2001) Self-association of CIITA correlates with its intracellular localization and transactivation. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 32191–32197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landmann S. et al. (2001) Maturation of dendritic cells is accompanied by rapid transcriptional silencing of class II transactivator (CIITA) expression. J. Exp. Med., 194, 379–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G., Harton,J.A., Zhu,X. and Ting,J.P. (2001) Dowregulation of CIITA function by protein kinase A (PKA)-mediated phosphorylation: mechanism of prostaglandin E, cyclic AMP, and PKA inhibition of class II major histocompatibility complex expression in monocytic lines. Mol. Cell. Biol., 21, 4626–4635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linhoff M.W., Harton,J.A., Cressman,D.E., Martin,B.K. and Ting,J.P. (2001) Two distinct domains within CIITA mediate self-association: involvement of the GTP-binding and leucine-rich repeat. Mol. Cell. Biol., 21, 3001–3011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhlethaler-Mottet A., Otten,L.A., Steimle.V. and Mach,B. (1997) Expression of MHC class II molecules in different cellular and functional compartments is controlled by differential usage of multiple promoters of the transactivator CIITA. EMBO J., 16, 2851–2860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nekrep N., Jabrane-Ferrat,N. and Peterlin,B.M. (2000) Mutations in the Bare Lymphocyte Syndrome define critical steps in the assembly of the regulatory factor X complex. Mol. Cell. Biol., 20, 4455–4461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raval A., Howcroft,T.K., Weissman,J.D., Kirshner,S., Zhu,X.-S., Yokoyama,K., Ting,J. and Singer,D.S. (2001) Transcriptional coactivator, CIITA, is an acetyltransferase that bypasses a promoter requirement for TAFII250. Mol. Cell, 7, 105–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reith W. and Mach,B. (2001) The Bare Lymphocyte Syndrome and the regulation of MHC expression. Annu. Rev. Immunol., 19, 331–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartorelli V., Puri,P.L., Hamamori,Y., Ogryzko,V., Chung,G., Nakatani,Y., Wang,J. and Kedes,L. (1999) Acetylation of MyoD directed by PCAF is necessary for the execution of the muscle program. Mol. Cell, 4, 725–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisk T.J., Roys,S. and Chang,C.H. (2001) Self-association of CIITA and its transactivation potential. Mol. Cell. Biol., 21, 4919–4928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steimle V., Otten,L.A., Zufferey,M. and Mach,B. (1993) Complementation cloning of an MHC class II transactivator mutated in hereditary MHC class II deficiency (or Bare Lymphocyte Syndrome). Cell, 75, 135–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steimle V., Siegrist,C.A., Mottett,A., Lisowska-Grospierre,B. and Mach,B. (1994) Regulation of MHC class II expression by interferon-γ mediated by the transactivator gene CIITA. Science, 265, 106–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosi G., De Lerma Barbaro,A., D’Agostino,A., Valle,M.T., Megiovanni,A.M., Manca,F., Caputo,A., Barbanti-Brodano,G. and Accolla,R.S. (2000) HIV-1 Tat mutants in the cysteine-rich region down-regulate HLA class II expression in T lymphocytic and macrophage cell lines. Eur. J. Immunol., 30, 19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]