Abstract

Type IIa Na/Pi cotransporters are expressed in renal proximal brush border and are the major determinants of inorganic phosphate (Pi) reabsorption. Their carboxyl-terminal tail contains information for apical expression, and interacts by means of its three terminal amino acids with several PSD95/DglA/ZO-1-like domain (PDZ)-containing proteins. Two of these proteins, NaPi-Cap1 and Na/H exchanger-regulatory factor 1 (NHERF1), colocalize with the cotransporter in the proximal brush border. We used opossum kidney cells to test the hypothesis of a potential role of PDZ-interactions on the apical expression of the cotransporter. We found that opossum kidney cells contain NaPi-Cap1 and NHERF1 mRNAs. For NHERF1, an apical location of the protein could be documented; this location probably reflects interaction with the cytoskeleton by means of the MERM-binding domain. Overexpression of PDZ domains involved in interaction with the cotransporter (PDZ-1/NHERF1 and PDZ-3/NaPi-Cap1) had a dominant–negative effect, disturbing the apical expression of the cotransporter without affecting the actin cytoskeleton or the basolateral expression of Na/K-ATPase. These data suggest an involvement of PDZ-interactions on the apical expression of type IIa cotransporters.

Keywords: opossum kidney cells‖Na, H exchanger-regulatory factor 1‖ proximal tubules

Proximal tubular reabsorption of inorganic phosphate (Pi) plays a key role in Pi metabolism (1, 2). Up to 80% of the renal reabsorption of Pi is mediated by the brush border membrane (BBM)-associated type IIa Na/Pi-cotransporters (NaPi IIa; refs. 3 and 4; for review, see ref. 2). According to their key physiological role, these cotransporters are up-regulated by factors that stimulate renal reabsorption of Pi (ref. 5; for review see ref. 2), whereas they are down-regulated by phosphaturic factors (refs. 6 and 7; for review, see ref. 2). Their expression is also affected in pathological states associated with Pi wasting, such as X-linked hypophosphatemic rickets: a primary defect on the PHEX gene leads by a yet-unknown mechanism to a reduced expression of NaPi IIa (8, 9). Many of the proximal tubular characteristics in terms of Pi handling are retained in a cell line derived from opossum kidney (OK) cells. These OK cells contain an endogenous NaPi IIa cotransporter (NaPi4) apically located and regulated by the same hormones and factors as NaPi IIa cotransporters in proximal tubules (6, 10, 11).

NaPi IIa cotransporters are predicted to contain eight transmembrane domains with intracellular N- and C-terminal tails (12). The C-terminal tail contains two signals involved in apical expression: a terminal PSD95/DglA/ZO-1-like domain (PDZ)-binding motif (TRL) and an internal determinant (13). The C-terminal tail interacts, by means of TRL residues, with several PDZ-containing proteins, among them NaPi-Cap1 and Na/H exchanger-regulatory factor 1 (NHERF1; ref. 14). Similar to NaPi IIa, both proteins are located on the BBM of proximal tubules (14, 15). NaPi-Cap1 is a protein of about 500 residues that contains four PDZ domains, one of which (PDZ-3) interacts with NaPi IIa (14). NaPi-Cap1, also named CAP70 (16), is the mouse ortholog of rat Diphor1 (17) and human PDZK1 (18). The human homologue is known to interact with the chloride channel CFTR (16) and the multidrug resistance-associated protein MRP2 (19), whereas interaction with a subtype of HDL scavenger receptors has been reported for the rat homologue (20). On the other hand, NHERF1 is a protein of about 350 residues that contains two PDZ domains, with PDZ-1 being responsible for interaction with NaPi IIa (14). Although NHERF1 was initially identified as the cofactor required for cAMP-inhibition of NHE3 (21, 22), it has been reported to interact with a wide variety of channels, transporters, and receptors (refs. 23–26; for review, see refs. 27 and 28). Unlike NHERF1, which is localized in the proximal tubule, a second isoform named NHERF2 (29) is localized in glomerulus and distal segments (15). Although NHERF1 and NHERF2 are highly homologous within their PDZ domains, they show no homology within their carboxyl-terminal domains (29).

PDZ domains are modules for protein–protein interaction and are involved in sorting and/or the stability of asymmetrically distributed proteins (30, 31). The findings that NaPi-Cap1 and NHERF1 are expressed in the renal proximal BBM and interact with the C-terminal tail of NaPi IIa in a PDZ-motif-dependent manner, together with the observation that this terminal PDZ-motif contains information for apical expression, prompted us to analyze whether such interactions are involved in apical expression of NaPi IIa. For this purpose, the interactions between the endogenous cotransporter (NaPi4) and the endogenous NaPi-Cap1 or NHERF1, respectively, were made to compete in a renal proximal cell model (OK cells), and we studied the effect of these competitions on the expression of the endogenous type II Na/Pi cotransporter.

Materials and Methods

Plasmids.

Nucleotide sequences encoding the myc epitope (EQKLISEEDL) immediately preceded by a Kozak consensus sequence were first introduced into the pcDNA3 plasmid (Invitrogen) between the XbaI and XhoI sites; simultaneously, a downstream NotI site was mutated to introduce a stop codon. These modifications were done by a single round of PCR in the presence of Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene) and a pair of primers containing in their 5′ the above extra sequences. The resulting PCR product was ligated with T4 DNA ligase and transformed into Escherichia coli. Then, either the full-length or the indicated discrete domains of NaPi-Cap1 (PDZ-3) and NHERF1 (PDZ-1, PDZ-2, and MERM-binding domain) were subcloned into the myc-pcDNA3 plasmid to generate myc-fused proteins. Subcloning involved PCR amplification of the above domains using Pfu DNA polymerase, followed by double digestions of plasmid and PCR fragments with XhoI and KpnI, and, finally, ligation with T4 DNA ligase. All constructs were partially sequenced to confirm that the inserts were in frame with the myc epitope.

Cell Culture, Transfections, and Immunostainings.

The methods for handling OK cells have been described in detail (10). Untransfected cultures were stained with antibodies against the rat homologue of NaPi-Cap1 (17) and NHERF (21) as well as with phalloidin-AlexaFluor (Molecular Probes) for actin staining. Where indicated, subconfluent cultures were transfected either with plasmids containing the myc-fusion proteins described above or with enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)-fused NaPi IIa (32). Transfections were done in the presence of Lipofectamine (GIBCO/BRL) following the manufacture's protocol. After reaching confluence, transfected cultures were processed for staining with antibodies against the endogenous NaPi IIa (NaPi4; ref. 33) and/or the myc epitope (Invitrogen) as well as with phalloidin-AlexaFluor; a monoclonal antibody against the Na/K-ATPase (Upstate Biotechnology, Lucerne) was also used in parallel experiments. Stainings were analyzed by confocal microscopy using a Leica TCSSP laser scan microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) equipped with a 40× oil-immersion objective; confocal sections were processed by using the IMARIS program.

Northern Blot.

Poly(A) samples were isolated from mouse kidney cortex as well as from OK cells by using a PolyATtract mRNA isolation system (Promega). Samples were separated on a 1% denaturing agarose gel, transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes, and preincubated for 4 h at 60°C following standard procedures (34). Membranes then were incubated overnight at 60°C with [32P]dCTP-labeled probes. For probes, we used either the whole ORF of mouse NaPi-Cap1 or the fragment encoding just the last 100 residues of mouse NHERF1. After a final wash in 1× SSC at 60°C, membranes were exposed to an x-ray film at −80°C.

Western Blots and Glutathione S-Transferase (GST) Pull-Downs.

OK cell total lysates (Ly) and membrane preparations (Ms) were done as reported (10). Ly were prepared by homogenizing cells in TBS (120 mM NaCl/50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 8) containing 0.5% Nonidet P-40 (Sigma) as detergent, whereas cracking buffer (5 mM Hepes/0.5 mM EDTA, pH 7.2) was used for M. After centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 2 min to remove unbroken cells, supernatants containing Ly were collected and either analyzed by Western blot or subjected to GST pull-downs. To obtain Ms, homogenates were centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 h, and pellets containing crude membranes were resuspended in 50 mM mannitol/10 mM Hepes⋅Tris, pH 7.2. Protein concentrations were determined in both cases by using a commercial kit (Bio-Rad). For Western blot analysis, samples of Ly (100 μg) and Ms (50 μg) were separated on an SDS/10% PAGE gel, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and incubated with antibodies against NaPi4, NaPi-Cap1, and NHERF; immunoreactive signals were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Pharmacia). Pull-downs were done as described (14). Briefly, Ly (200 μg) were incubated for 1 h at 4°C with glutathione agarose beads coupled either to GST alone, GST-PDZ3/CAP1, or GST-PDZ1/NHERF1. Construction of these GST-fused proteins has been described (14). Then, samples were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min. Supernatants containing unbound NaPi4 (Ub) were saved, and the pelleted beads containing bound NaPi4 (Bd) were washed three times in TBS/Nonidet P-40. Both Ub and Bd fractions were mixed with loading buffer, incubated at 95°C for 2 min, and analyzed by Western blotting using the NaPi4 antibody.

Results and Discussion

We have shown that the C-terminal PDZ-binding motif of NaPi IIa (TRL) is involved in its apical expression (13). Several proteins interact with this tail in a PDZ-dependent manner (14). Two of these proteins, NaPi-Cap1 and NHERF1, have the same cellular location as NaPi IIa cotransporters; i.e., they are expressed in the proximal tubular BBM (14, 15).

OK Cells Express Endogenous NaPi-Cap1 and NHERF1.

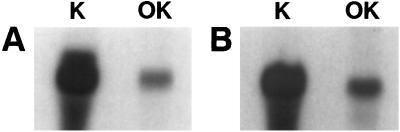

OK cells contain the molecular machinery required for membrane expression and regulatory membrane retrieval/reinsertion of NaPi IIa (refs. 10 and 11; for review, see ref. 2). By using the cDNA of murine NaPi-Cap1 as probe, we detected a 2.4-kb mRNA species in OK cells (Fig. 1A); this mRNA corresponds to the major signal in mouse kidney cortex mRNA (Fig. 1A; ref. 17). The weaker signal in OK cells compared with mouse kidney cortex may be because of species differences (mouse vs. OK cells), although it could also reflect a relatively lower abundance in OK cells. A fragment encoding just the last 100 residues of NHERF1 was used as probe to test whether OK cells express this proximal tubular specific NHERF isoform. As shown in Fig. 1B, the NHERF1-specific probe recognized an mRNA species both in kidney cortex as well as in OK cells. Therefore, in addition to an endogenous NaPi IIa (NaPi4), OK cells also express NaPi-Cap1 and NHERF1, at least at the mRNA level.

Figure 1.

OK cells express endogenous NaPi-Cap1 and NHERF-1 mRNAs. Samples of 10 μg of polyA RNA extracted from mouse kidney cortex (K) and OK cells (OK) were separated in a 10% agarose denaturing gel, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and incubated overnight with [32P]dCTP-labeled NaPi-Cap1 (A) or NHERF1 (B) probes.

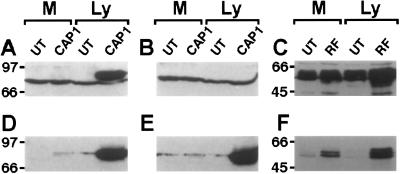

An antibody specific for the rat ortholog of NaPi-Cap1 (17) failed to recognize a specific band in preparations from untransfected OK cells (Fig. 2A). Although a 66-kDa band was stained, its detection was not prevented by preincubation of the antiserum with the immunogenic peptide (Fig. 2B). In contrast, a band of 70 kDa was detected by both the NaPi-Cap1 and myc antibodies in Ly from OK cells transiently transfected with the mouse myc-Cap1 (Fig. 2 A, D, and E). This band was detected in the absence (Fig. 2A) but not in the presence (Fig. 2B) of the immunogenic peptide. This set of data suggests that the antibody against the rat protein does not recognize the endogenous NaPi-Cap1 from OK cells; alternatively, the protein may not be expressed in significant amounts. An antibody generated against a peptide conserved in the rabbit, human, and murine NHERF1 has been shown to recognize a 50-kDa band in OK cells (21, 35). By using this antibody, we could detect the corresponding band both in Ly and in Ms from either untransfected cultures or from cells transiently transfected with myc-NHERF1 (Fig. 2C). In transfected cells, the same band was recognized by the myc antibody (Fig. 2F). Based on sequence homology, the NHERF antibody also may recognize the NHERF2 isoform (21, 29). However, based on the proximal tubular origin of OK cells and in the finding that proximal tubules contain NHERF1 but not NHERF2 (15), as well as on our Northern blot (Fig. 1B) and myc antibody data (Fig. 2F), we consider that the band detected in OK cells is related to NHERF1 rather than to NHERF2. Incubation with a rabbit NHERF1-specific antibody (35) failed to detect the protein in OK Ms (data not shown), probably because of interspecies differences (opossum vs. rabbit).

Figure 2.

Endogenous NHERF-1 (C) but not NaPi-Cap1 (A and B) is recognized by available antibodies. Samples of Ly (100 μg) or Ms (50 μg) from untransfected (UT) or transfected (CAP1/RF) OK cells were separated on an SDS/10% PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were incubated with either a NaPi-Cap1 (Diphor1) antibody in the absence (A) or presence (B) of 50 μg/ml of the antigenic peptide, or with a NHERF antibody (C). The same membranes were subsequently incubated with a myc monoclonal antibody (D–F).

Subcellular Localization of NHERF1 in OK Cells.

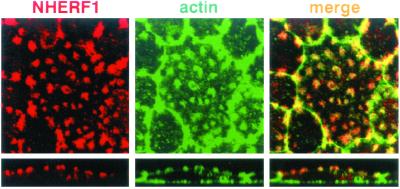

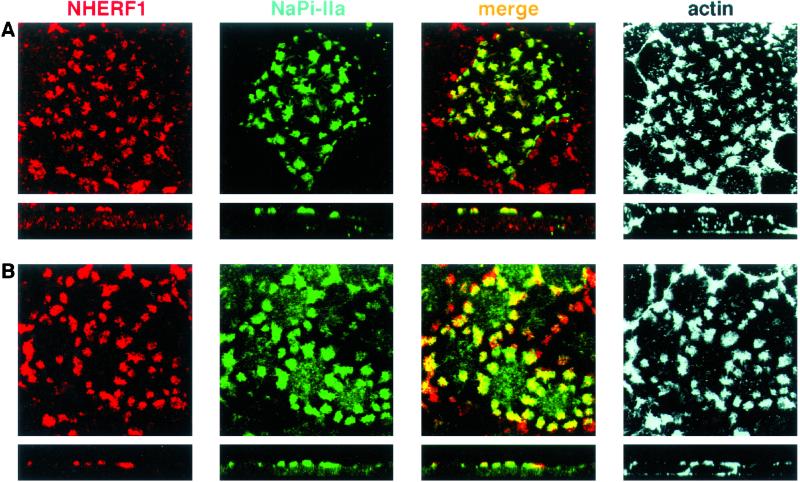

Stainings of OK cultures with the NHERF antibody revealed that the protein was expressed in apical patches (Fig. 3), a pattern reminiscent of that of NaPi IIa (10, 11, 32). We have reported (10) that NaPi IIa patches represent clusters of actin where the cotransporter accumulates. As shown in Fig. 3, there was a total overlap between the NHERF1 and actin locations, as indicated by the yellow signal of the merged composite. As indicated above for the Western blot data, the NaPi-Cap1 antibody also failed to identify the endogenous protein in immunostainings (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Endogenous NHERF-1 is expressed in actin-containing apical patches. Confluent OK cultures plated on coverslips were stained with the NHERF antibody (in red) and with phalloidin-AlexaFluor to detect actin signal (in green). Samples were analyzed by confocal microscopy: squares represent apical focal planes and rectangles represent confocal cross sections. There was a total overlap between the NHERF1 and actin stainings, as reflected by the yellow signal of the merge composite, indicating that NHERF1 is accumulated in actin-containing apical patches.

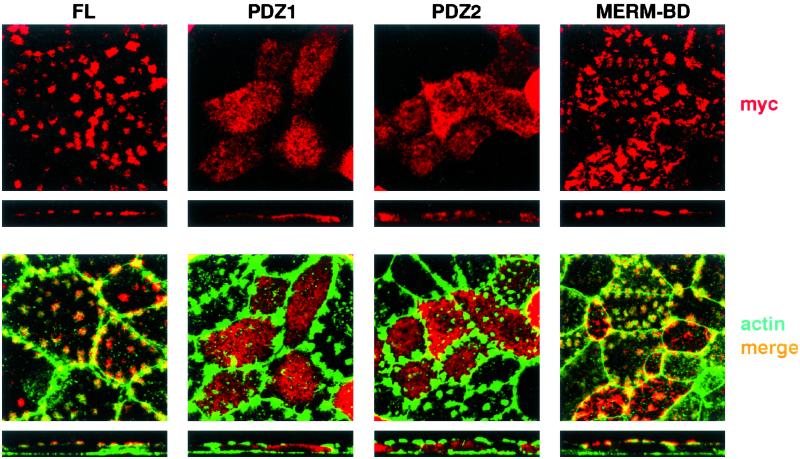

NHERF1 associates through its C-terminal domain with members of the Merlin-Ezrin-Radixin-Moesin (MERM) family (36). It has been suggested that Ezrin binds and thus attaches actin filaments to the plasma membrane (37). To address whether the MERM-binding domain is involved in the expression of NHERF1 in apical patches, we transfected OK cells with several myc-NHERF1 constructs and analyzed their expression. As shown in Fig. 4, the full-length (FL) protein as well as the construct containing only the MERM-binding domain reproduced the pattern of expression of the endogenous NHERF1 and were expressed within actin-containing apical patches; in contrast, the constructs containing only PDZ-1 or PDZ-2 were detected intracellularly. These data show that the MERM-binding domain by itself retains apical location, suggesting its involvement in the apical expression of NHERF1.

Figure 4.

The MERM-binding domain of NHERF1 retains apical expression. OK cultures were transfected with myc constructs containing either the full-length NHERF1 (FL) or only the PDZ-1, PDZ-2, or MERM-binding domain. Samples were stained with myc antibody (red) and with phalloidin-AlexaFluor (green) and were analyzed by confocal microscopy. (Upper) myc staining (NHERF-related signals). (Lower) myc/actin merge. The transfected FL protein as well as the construct containing only the MERM-binding domain reproduced the pattern of expression of the endogenous NHERF1; i.e., they appear in apical patches.

To test whether NHERF1 and NaPi IIa are expressed within the same actin patches, OK cells were transfected either with the EGFP-fused cotransporter (Fig. 5A) or with the myc-NHERF1 (Fig. 5B). Cultures then were stained with antibodies against NHERF and actin or against myc, NaPi4, and actin, respectively. Simultaneous staining of endogenous NHERF1 and NaPi4 was prevented by the fact that all available antibodies are anti-rabbit antiserum. We found that the same actin patches indeed contained NHERF1 and NaPi4 cotransporter, as reflected by the yellow signal in the merge composite (Fig. 5 A and B). This set of experiments documents that OK cells, like renal proximal tubules, express NHERF1 within the same cellular compartment as the NaPi IIa. The location of NaPi-Cap1 in OK cells remains elusive because of the lack of immunolocation data (see above).

Figure 5.

NaPi4 and NHERF1 colocalize in actin-containing apical patches. OK cells were transfected with either EGFP-NaPi (A) or with myc-NHERF1 (B). Cultures then were stained with antibodies against NHERF and actin (A) or against myc, NaPi4, and actin (B), respectively. Samples were analyzed by confocal microscopy. NaPi4 and NHERF1 colocalize in actin patches, as reflected by the yellow signal of the merge composite.

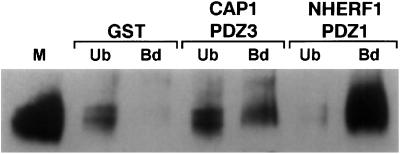

NaPi-Cap1 and NHERF1 Interact with NaPi4.

To test whether the endogenous NaPi4 interacts with NaPi-Cap1 and NHERF1, we performed pull-down experiments in Ly from OK cells. Yeast two hybrid data and pull-down experiments using proximal BBM indicated that the C-terminal tail of the cotransporter interacts with the PDZ-3 of NaPi-Cap1 and the PDZ-1 of NHERF1 (14). Therefore, GST-fused constructs containing only these interacting domains were used for pull-downs. As shown in Fig. 6, incubation of OK Ly with both GST-PDZ3/Cap1 and GST-PDZ1/NHERF1 led to the pull-down of NaPi4, because NaPi4 signal was recovered in the Bd fractions. NHERF1 pulled down NaPi4 more efficiently than NaPi-Cap1: some NaPi4 signal remained in the PDZ3/Cap1 Ub fraction, whereas very little was detected in the PDZ1/NHERF1-Ub; whether or not this reflects a general higher affinity of the cotransporter for NHERF1 than for NaPi-Cap1, or whether it is because of different affinities of the OK cells cotransporter for the mouse proteins remains unclear. GST alone failed to interact with the cotransporter, as reflected by the lack of NaPi4 signal in the Bd fraction. These data indicate that also NaPi4 is able to interact with NaPi-Cap1 and NHERF1.

Figure 6.

NaPi-Cap1 and NHERF1 pull down the endogenous (NaPi4) cotransporter. Samples of 200 μg of OK Ly were incubated with GST alone or with GST-PDZ3/Cap1 or GST-PDZ1/NHERF1, as indicated in Materials and Methods. Unbound (Ub; supernatants) and bound (Bd; pellets) samples as well as 50 μg of Ms were separated in an SDS/PAGE gel, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and incubated with a NaPi4 antibody. PDZ3/CAP1 and PDZ1/NHERF1 led to the pull-down of NaPi4, indicating that NaPi4 is able to interact with both proteins.

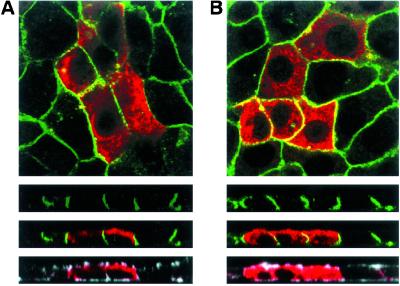

Disruption of the Endogenous Interactions Affects Apical Expression of NaPi4.

Next, we studied whether the interactions with NaPi-Cap1 and NHERF1 are involved in the apical expression of NaPi4. For that purpose, we transfected OK cells with plasmids containing only the myc-fused interacting PDZ domains. By expressing only the interacting domains, we expected the association between endogenous partners to compete with nonproductive interactions; the transfected constructs do not contain most of the protein sequences which are most probably required for NaPi-Cap1/NHERF to interact with additional partners and, thus, to mediate their physiological effect. Then, the pattern of expression of NaPi4 patches was compared in untransfected (myc-negative) and transfected cells (myc-positive) showing normal actin patches (impaired expression of NaPi4 would be expected in cells with a disturbed actin cytoskeleton). By using a similar dominant–negative approach, it has been reported recently that MERM-deficient NHERF1 impairs cAMP-induced inhibition of NHE3 in OK cells (35). We found that 75% of untransfected cells contained strong NaPi4 patches, whereas 25% had weak patches (Fig. 7 A–C). In contrast, only 30% of cells with a strong PDZ1/NHERF1 signal contained strong NaPi4 patches, although they had a normal actin cytoskeleton (Fig. 7 A and B); this ratio increased to 50% in cells with weak PDZ1/NHERF1 signal, but the difference with untransfected cells remained statistically significant. On the other hand, 55% of cells with strong PDZ3/CAP1 signal contained strong NaPi4 patches (Fig. 7C), a ratio significantly lower than in untransfected cells; this value increased to 66% in cells with weak PDZ3/CAP1 signal, losing statistical significance. Complementary experiments transfecting the C-terminal tail of NaPi IIa, the other partner in the interactions, were not feasible because the NaPi4 antibody is directed against this tail (33). To assess the specificity of the NHERF1 and NaPi-Cap1 dominant–negative effects on the apical expression of NaPi4, we stained OK cultures with antibodies against apical proteins known to be expressed in this cell line. Staining with polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies against the rat 5′-nucleotidase, rabbit amino acid transporters and human ezrin all failed to identify their OK cells counterpart (data not shown). In contrast, a monoclonal antibody against the rat Na/K-ATPase recognized this basolateral protein in OK cells. The location of the endogenous Na/K-ATPase was unaffected by expression of PDZ1/NHERF1 (Fig. 8A) or PDZ3/CAP1 (Fig. 8B). This latter information, together with the fact that the effect of expressing the PDZ domains was analyzed only in those cells with a normal apical actin cytoskeleton, supports the specificity of our findings.

Figure 7.

Expression of PDZ1/NHERF1 and PDZ3/NaPi-Cap1 impairs apical expression of the endogenous NaPi4. OK cells were transfected with myc-fused PDZ1/NHERF (A, B) or PDZ3/Cap1 (C), and stained for myc (A, red), actin (A, white), and NaPi4 (A, green). In every transfection experiment, we consistently detected the presence of two types of cells: one with a strong myc signal (myc++) and a second one with a clear but weaker myc fluorescence (myc+). Discrimination between both groups was easy and consistently clear within single experiments. (A) Squares show apical focal planes and rectangles show confocal cross sections of cultures transfected with myc-fused PDZ1/NHERF. Untransfected (myc−) or transfected cells (myc++, myc+) showing a normal actin cytoskeleton were analyzed for the expression of strong (black bars) or weak (white bars) NaPi4 patches. (B and C) Bars = mean ± SE of nine independent experiments. *, P < 0.05.

Figure 8.

Expression of PDZ1/NHERF1 and PDZ3/NaPi-Cap1 does not affect basolateral expression of the endogenous Na/K-ATPase. OK cells were transfected with myc-fused PDZ1/NHERF (A) or PDZ3/Cap1 (B) and stained for myc (red), actin (white), and Na/K-ATPase (green). Samples were analyzed by confocal microscopy: squares represent basal focal planes and rectangles represent confocal cross sections.

A role of PDZ interactions in the functional and structural organization of the plasma membrane is emerging (31). These 80- to 90-aa modules are found throughout evolution, and are typically expressed in multiple copies within a given protein. In polarized epithelial cells, proteins containing PDZ domains are expressed within particular membrane domains (cell–cell contacts, apical or basolateral surfaces) where they colocalize with their binding partners. This membrane expression may be mediated, at least partially, by the ability of many PDZ proteins to interact with the cortical cytoskeleton (for review, see ref. 31). Therefore, one role of PDZ interactions may be to anchor the binding partner to a specific membrane domain. In addition, the presence of several PDZ domains within a single protein, together with their ability of form homo- or heteromultimeric complexes, may allow these proteins to form large domain-specific protein complexes. NaPi-Cap1 homologues interact with several membrane proteins, among them the multidrug resistance-associated protein MRP2 (19), the chloride channel CFTR (16), and the HDL-scavenger receptor SR-BI (20). Although no functional implications were suggested for MRP2, interaction of NaPi-Cap1 was reported to potentiate CFTR and SR-BI activity. An activating dimerization mechanism seems to operate in the case of CFTR (16), whereas interaction with NaPi-Cap1 could serve to anchor SR-BI receptors on the correct membrane domain (20). On the other hand, many transporters, channels, and receptors are known to interact with NHERF (for review, see refs. 27 and 28). Interaction with NHERF has been shown to be required for apical expression of CFTR (25, 26) as well as for recycling of β2-adrenergic receptors (24). Our data are consistent with a role of NaPi-Cap1 and NHERF1 on the apical expression of type IIa Na/Pi-cotransporters (Fig. 7). The relatively smaller effect of NaPi-Cap1 compared with NHERF1 could reflect differences in affinity of the NaPi4 PDZ-binding motif (TRL) for the interacting PDZ domains of both proteins (Fig. 6). Alternatively, anchoring of NaPi-Cap1 to the apical membrane of OK cells may be less efficient than anchoring of NHERF1. In this regard, NHERF1 is known to bind actin through association with ezrin (36), and such association is reproducible in OK cells (Fig. 4). However, the equivalent cytoskeleton counterpart for NaPi-Cap1 (per se a hydrophilic protein) is unknown; moreover, it is not known whether this protein is expressed in OK cells. Interestingly, although NaPi-Cap1 is detected in proximal BBM, both EGFP- and myc-fused Cap1 failed to reach (or to stay) in the apical membrane of OK cells (data not shown). Whether the interaction of type IIa cotransporters with NaPi-Cap1 and NHERF1 is involved in the stabilization of the cotransporters at the apical membrane or also plays a role in the rate of recycling of endocytosed cotransporters is unknown. However, based on our observation that recycling does not play a role in the regulation of these transporters in OK cells (10), a stabilization effect seems more likely. Recent reports suggest that both NaPi-Cap1 (19) and NHERF1 (38) are able to self-associate, and we have data indicating that they can also interact with each other (S.G., unpublished work). In addition, both proteins contain PDZ domains that are not involved in binding to type IIa cotransporters but that can interact with other apical or intracellular proteins. Formation of these homomeric and heteromeric complexes beneath the proximal brush border may play a role in organizing this compartment in terms of making complexes of different membrane proteins and/or linking proteins to the cytoskeleton and cellular regulatory machinery.

In conclusion, we have provided evidence that NHERF1 and NaPi-Cap1, two PDZ-containing proteins known to bind to the terminal TRL residues of type IIa Na/Pi cotransporters, play a role in the apical expression of these cotransporters.

Acknowledgments

We thank Christian Gasser for assistance in preparing the figures. This work was supported by Swiss National Science Foundation Grant 31.46523 (to H.M.), Hartmann Müller-Stiftung (Zürich, Switzerland), Olga Mayenflsch-Stiftung, Schweizerische Bank-Gesellschaft (Zürich; Bu 70417-1), and Fridericus-Stiftung.

Abbreviations

- BBM

brush border membranes

- OK

opossum kidney

- PDZ-domain

PSD95/DglA/ZO-1-like domain

- NHERF

Na/H exchanger-regulatory factor

- Ly

total lysates

- Ms

membrane preparations

- GST

glutathione S-transferase

- Ub

unbound

- Bd

bound

- MERM

Merlin-Ezrin-Radixin-Moesin

References

- 1.Murer H, Kaissling B, Forster I, Biber J. In: The Kidney: Physiology and Pathophysiology. 3rd Ed. Seldin D W, Giebish G, editors. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murer H, Hernando N, Forster I, Biber J. Physiol Rev. 2000;80:1373–1409. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.4.1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beck L, Karaplis A C, Amizuka N, Hewson A S, Ozawa H, Tenenhouse H S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:5372–5377. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Custer M, Lötscher M, Biber J, Murer H, Kaissling B. Am J Physiol. 1994;35:F767–F774. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1994.266.5.F767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ritthaler T, Traebert M, Lötscher M, Biber J, Murer H, Kaissling B. Kidney Int. 1999;55:976–983. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.055003976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bacic D, Hernando N, Traebert M, Lederer E, Völk H, Biber J, Kaissling B, Murer H. Pflügers Arch Eur J Physiol. 2001;443:306–313. doi: 10.1007/s004240100695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Traebert M, Völkl H, Biber J, Murer H, Kaissling B. Am J Physiol. 2000;278:F792–F798. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.278.5.F792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.HYP Consortium. Nat Genet. 1995;11:130–136. doi: 10.1038/ng1095-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tenenhouse H S. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999;14:333–341. doi: 10.1093/ndt/14.2.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pfister M F, Lederer E, Forgo J, Ziegler U, Lötscher M, Quabius E S, Biber J, Murer H. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:20125–20130. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.32.20125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pfister M F, Hilfiker H, Forgo J, Lederer E, Biber J, Murer H. Pflügers Arch. 1998;435:713–719. doi: 10.1007/s004240050573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lambert G, Traebert M, Hernando N, Biber J, Murer H. Pflügers Arch. 1999;437:972–978. doi: 10.1007/s004240050869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karim-Jimenez Z, Hernando N, Biber J, Murer H. Pflügers Arch Eur J Physiol. 2001;442:782–790. doi: 10.1007/s004240100602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gisler S, Stagljar I, Traebert M, Bacic D, Biber J, Murer H. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:9206–9213. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008745200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wade J B, Welling P A, Donowitz M, Shenolikar S, Weinman E. Am J Physiol. 2001;280:C192–C198. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.280.1.C192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang S, Yue H, Derin R B, Guggino W B, Li M. Cell. 2000;103:169–179. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00096-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Custer, M., Spindler, B., Verrey, F., Murer, H. & Biber, J. (1997) Am. J. Physiol. F801–F806. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Kocher O, Comella N, Tognazzi K, Brown L F. Lab Invest. 1998;78:117–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kocher O, Comella N, Gilchrist A, Pal R, Tognazzi K, Brown L F, Knoll J H M. Lab Invest. 1999;79:1161–1170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ikemoto M, Arai H, Feng D, Tanaka K, Aoki J, Dohmae N, Takio K, Adachi H, Tsujimoto M, Inoue K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6538–6543. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100114397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weinman E J, Steplock D, Wang Y, Shenolikar S. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:2143–2149. doi: 10.1172/JCI117903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weinman E J, Steplock D, Donowitz M, Shenolikar S. Biochemistry. 2000;39:6123–6129. doi: 10.1021/bi000064m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Breton S, Wiederhold T, Marshansky V, Nsumu N N, Ramesh V, Brown D. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:18219–18224. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M909857199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cao T T, Deacon H W, Reczek D, Bretscher A, von Zastrow M. Nature (London) 1999;401:286–290. doi: 10.1038/45816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moyer B D, Denton J, Karlson K, Reynolds D, Wang S, Mickle J E, Milewski M, Cutting G R, Guggino W B, Min L, Stanton B A. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:1353–1361. doi: 10.1172/JCI7453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moyer B D, Duhaime M, Shaw C, Denton J, Reynolds D, Karlson K H, Pfeiffer J, Wang S, Mickle J E, Milewski M, et al. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:27069–27074. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004951200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moe O W. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:2412–2425. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V10112412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weinman E J, Minkoff C, Shenolikar S. Am J Physiol. 2000;279:F393–F3999. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.279.3.F393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yun C H C, Oh S, Zizak M, Steplock D, Tsao S, Tse C-M, Weinman E J, Donowitz M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3010–3015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dunbar L A, Caplan M J. Eur J Cell Biol. 2000;79:557–563. doi: 10.1078/0171-9335-00079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fanning A S, Anderson J M. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:767–762. doi: 10.1172/JCI6509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hernando N, Sheikh S, Karim-Jimenez Z, Galliker H, Forgo J, Biber J, Murer H. Am J Physiol. 2000;278:F361–F368. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.278.3.F361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lederer E D, Sohi S S, Mathiesen J M, Klein J B. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:F270–F277. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1998.275.2.F270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 2nd Ed. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weinman E J, Steplock D, Wade J B, Shenolikar S. Am J Physiol. 2001;281:F374–F380. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.281.2.F374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reczek D, Berryman M, Bretscher A. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:169–179. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.1.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bretscher A. J Cell Biol. 1983;97:425–432. doi: 10.1083/jcb.97.2.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fouassier L, Yun C C, Fittz J G, Doctor R B. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:25039–25045. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000092200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]