Abstract

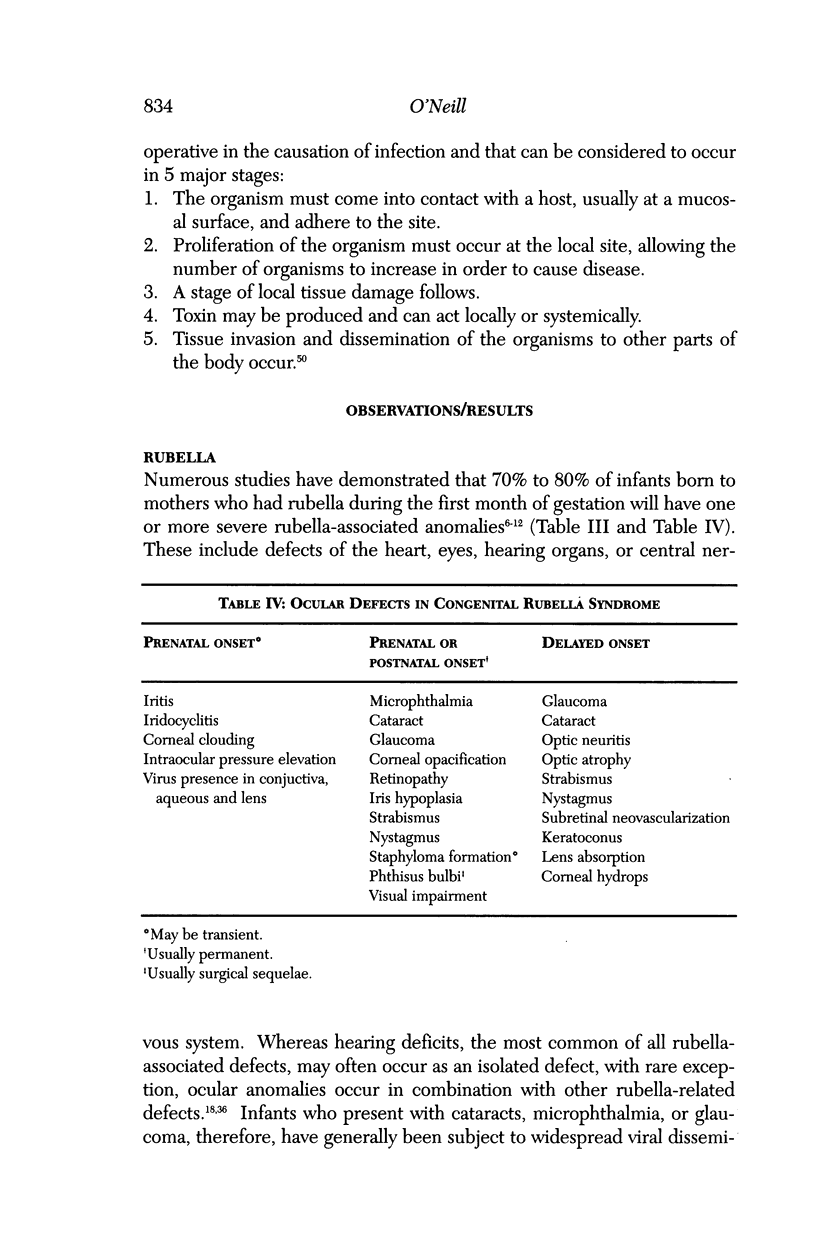

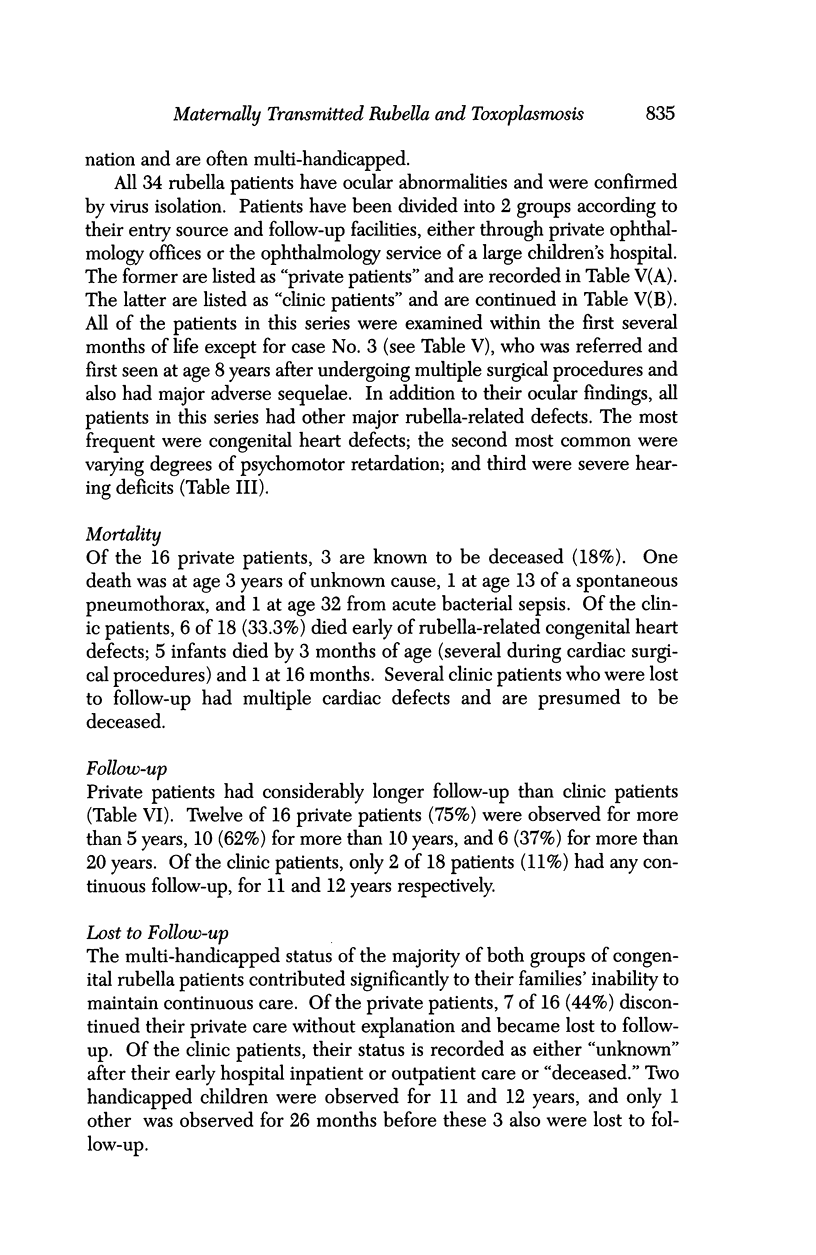

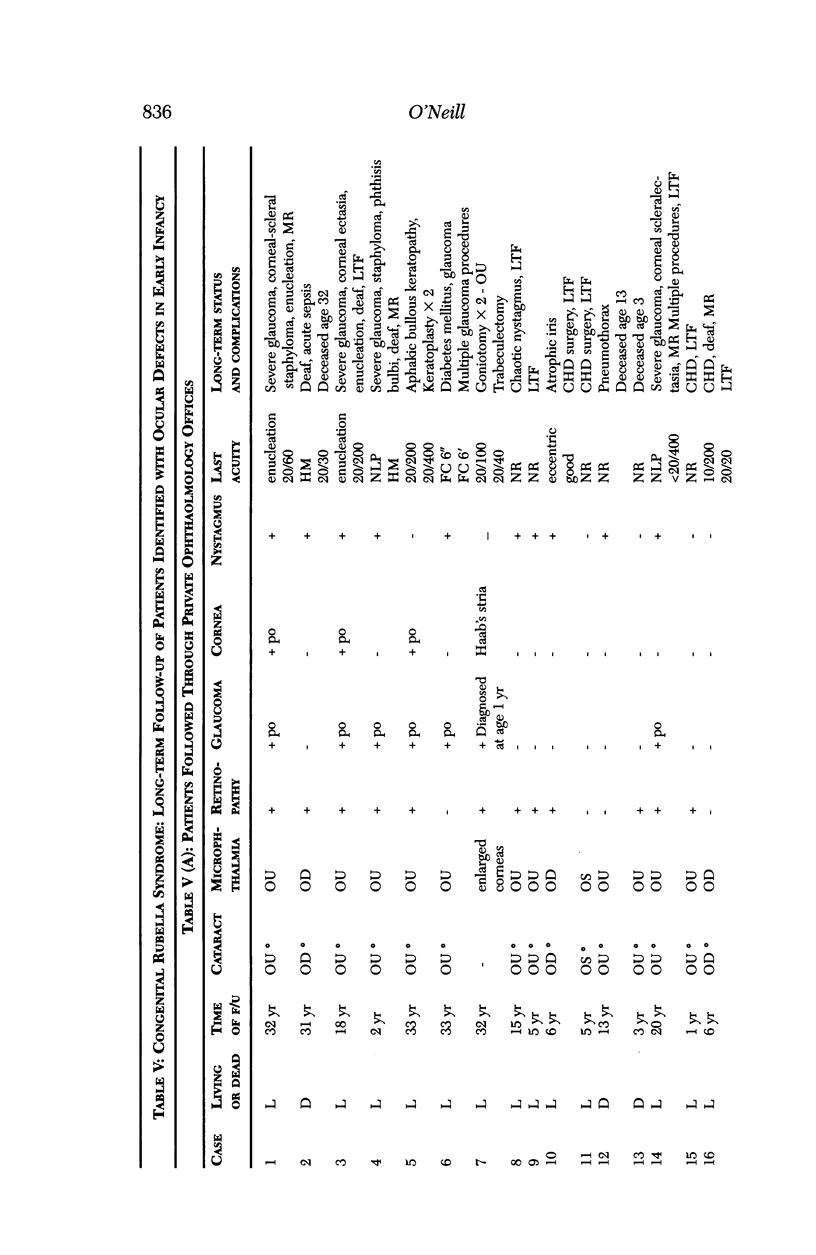

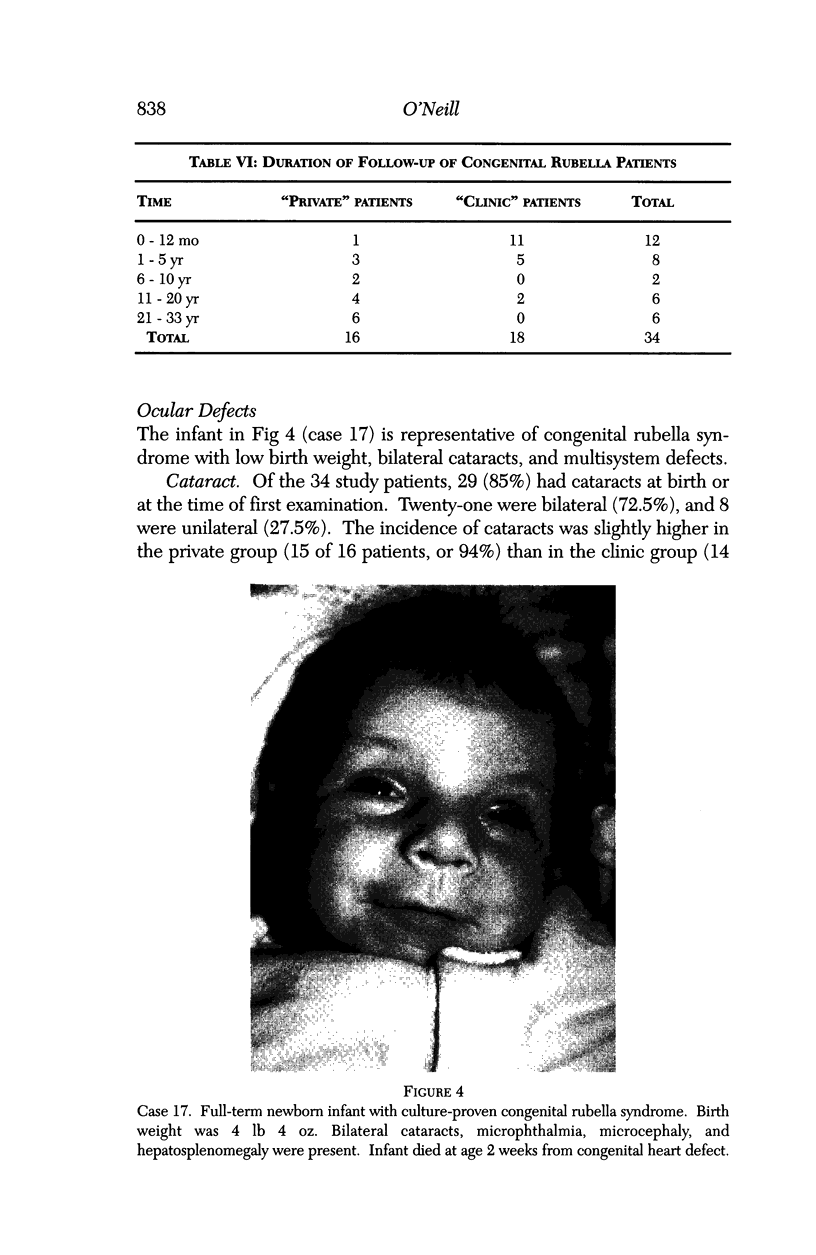

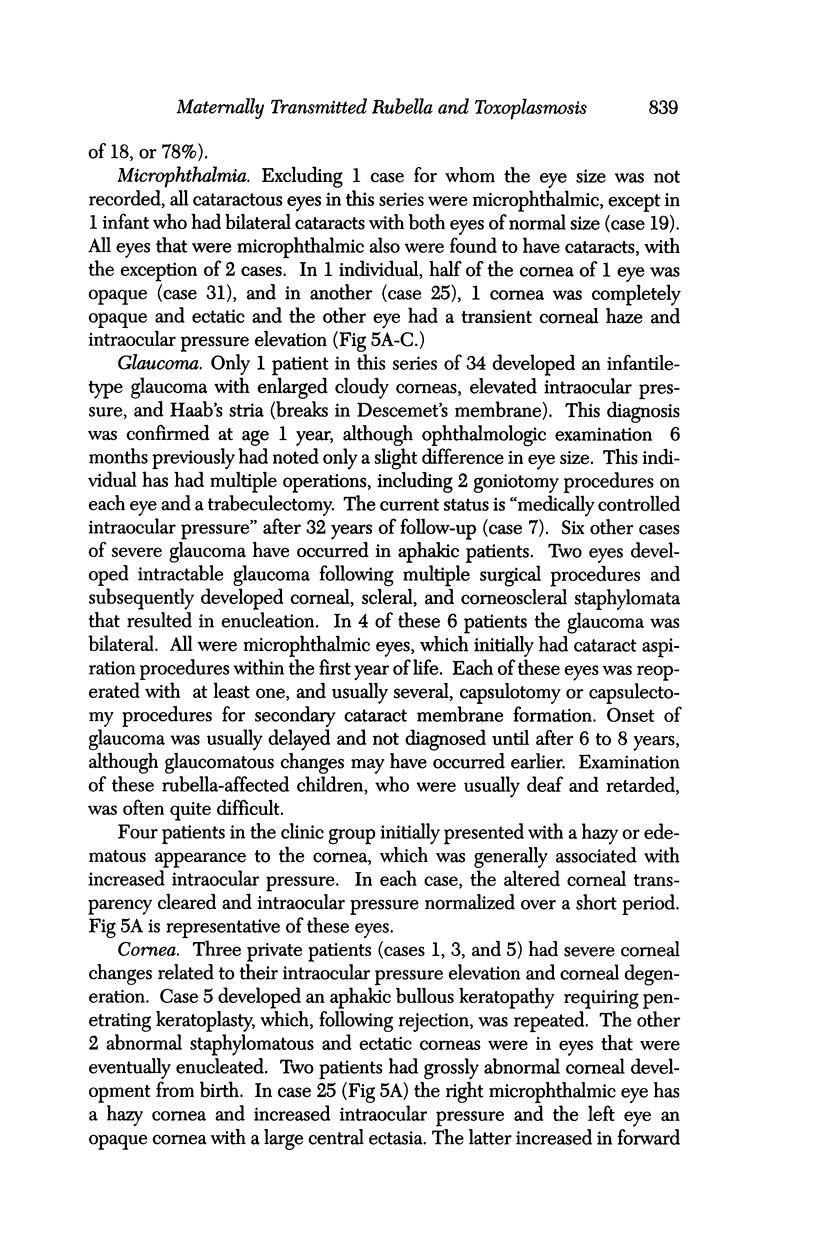

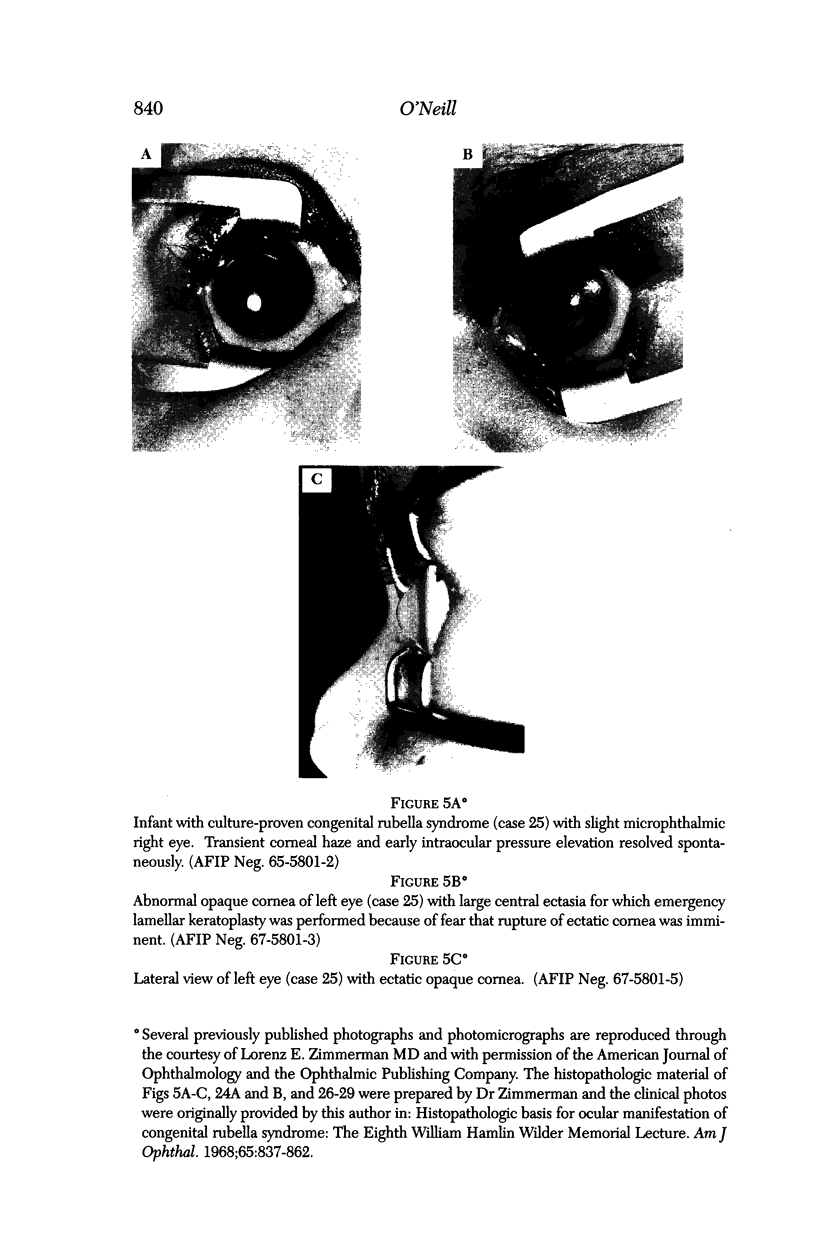

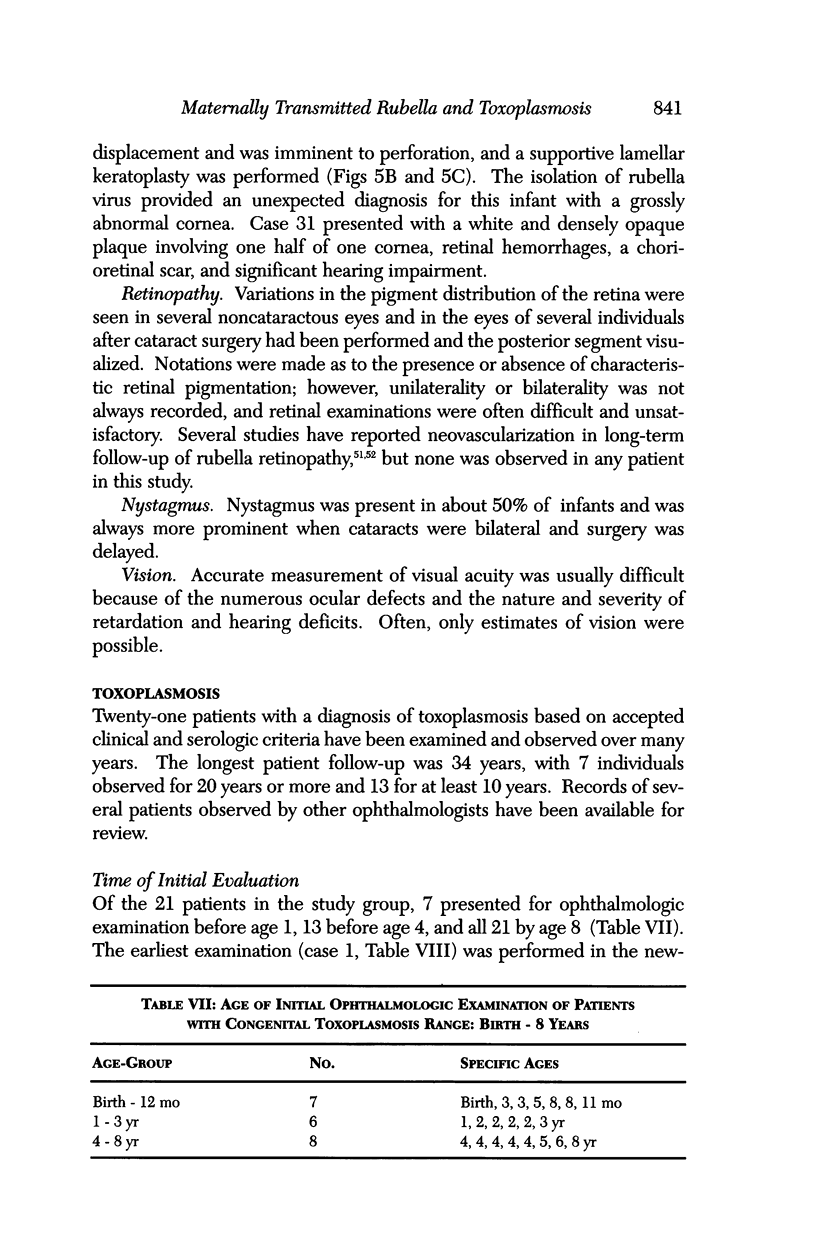

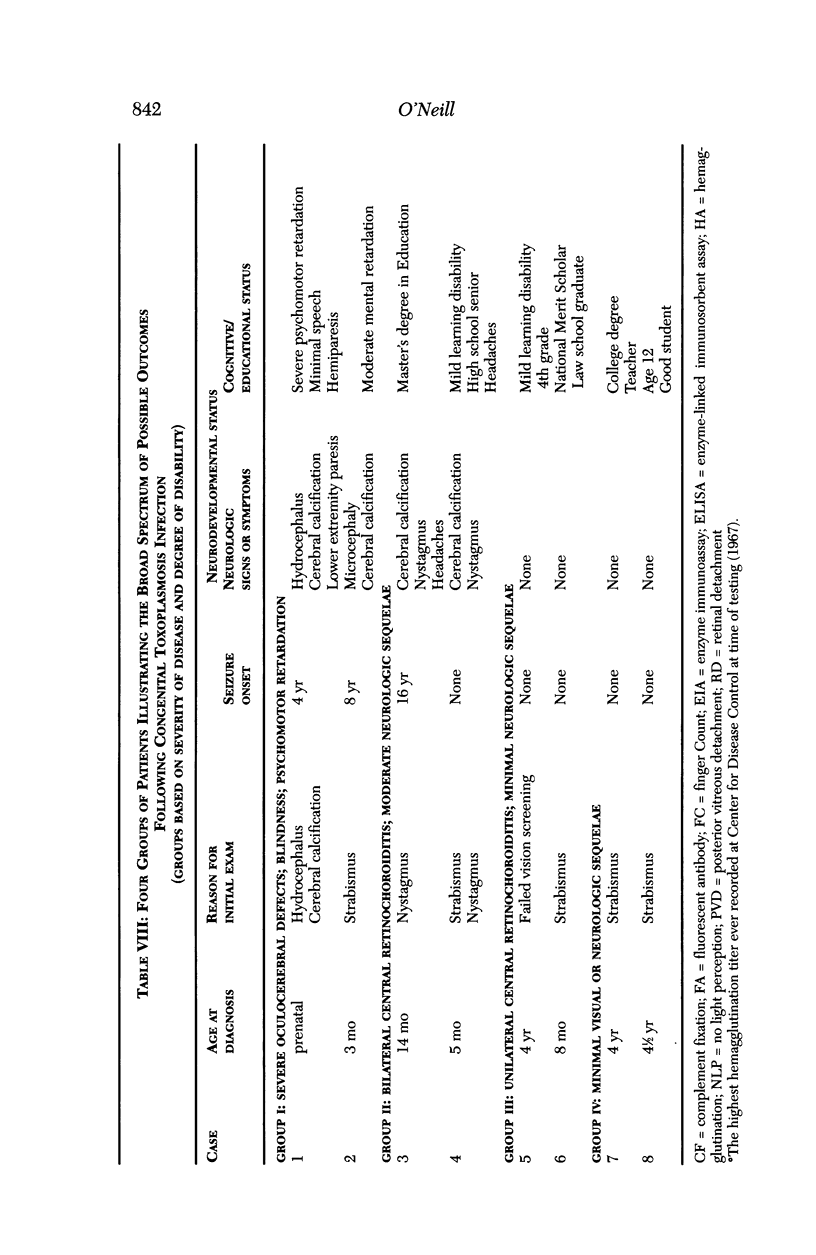

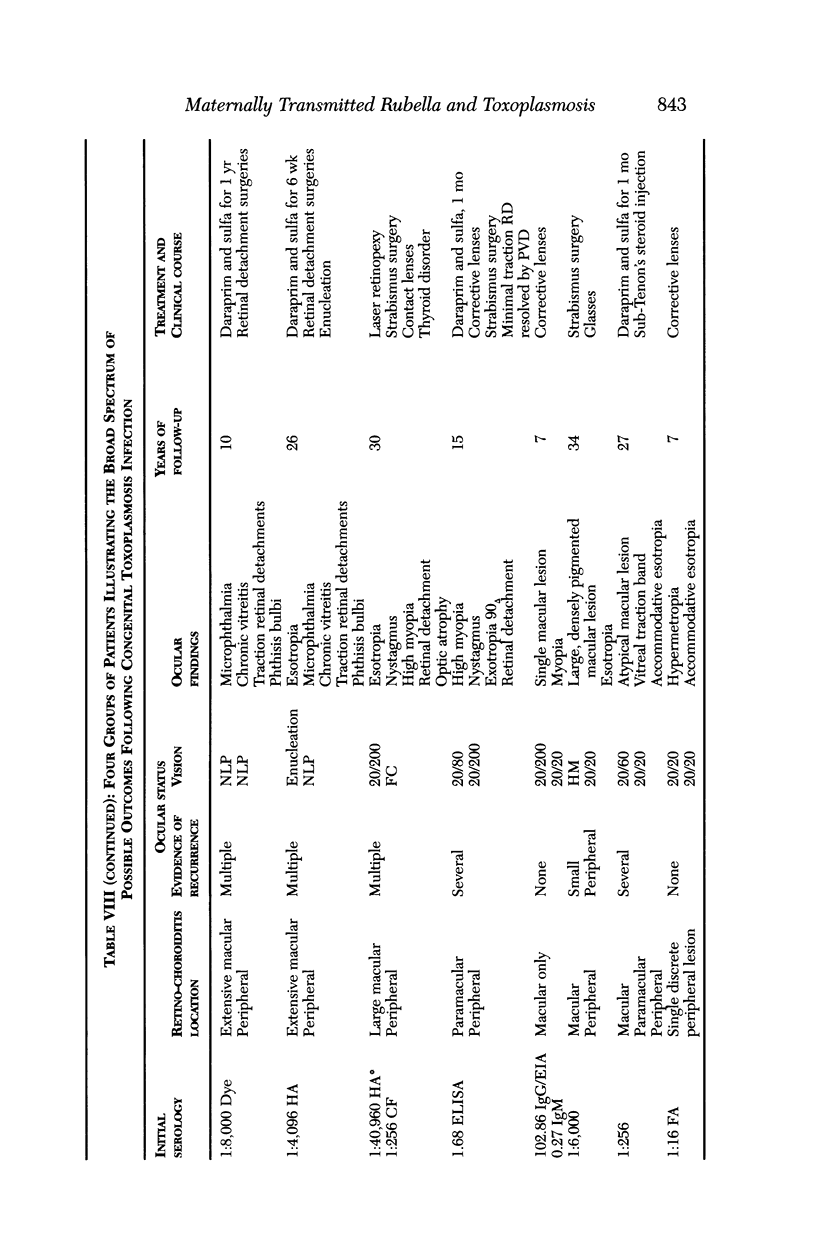

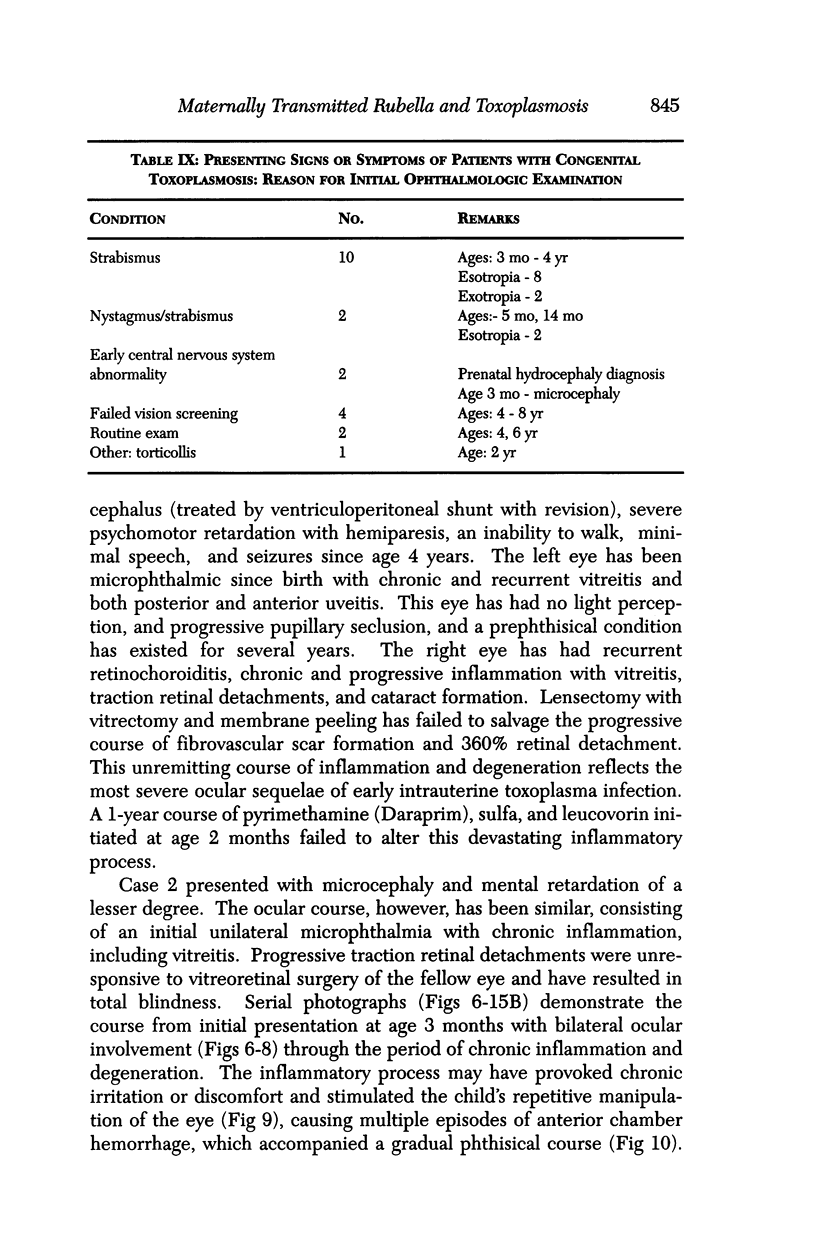

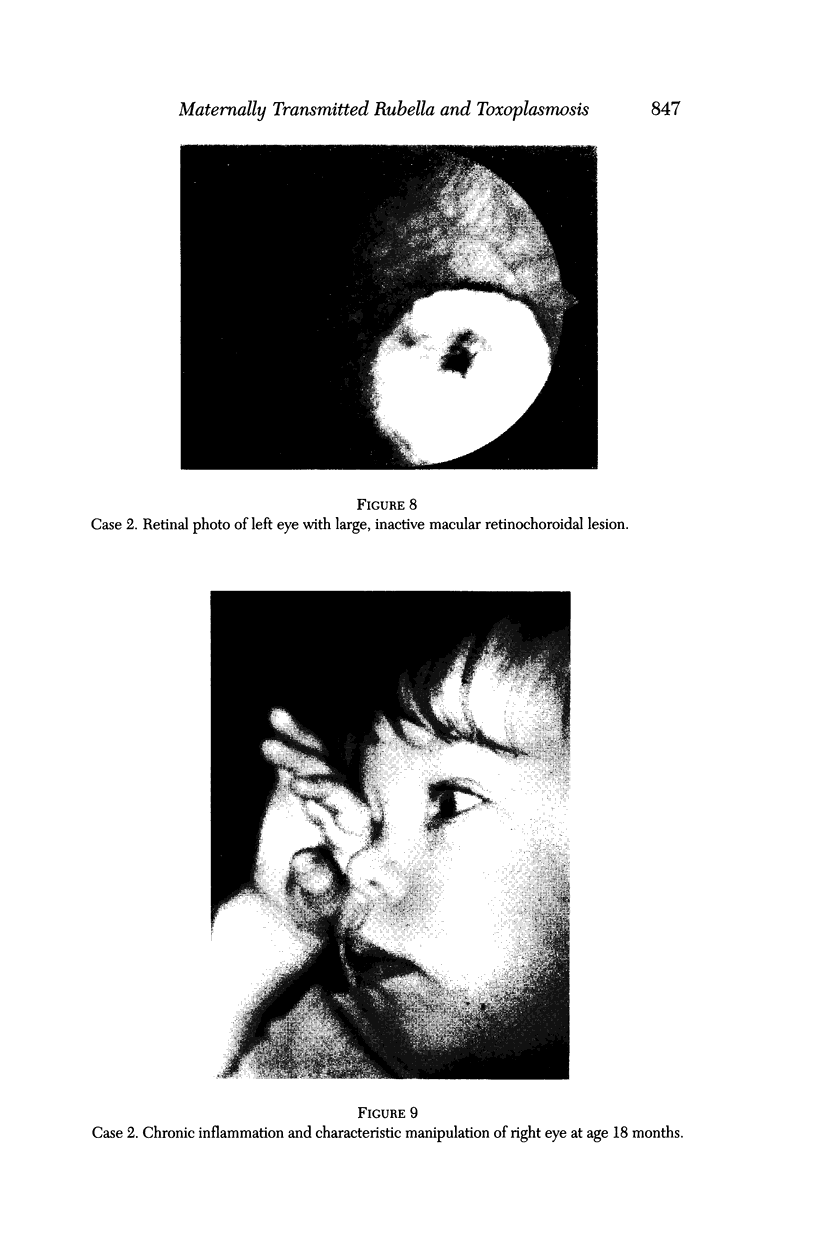

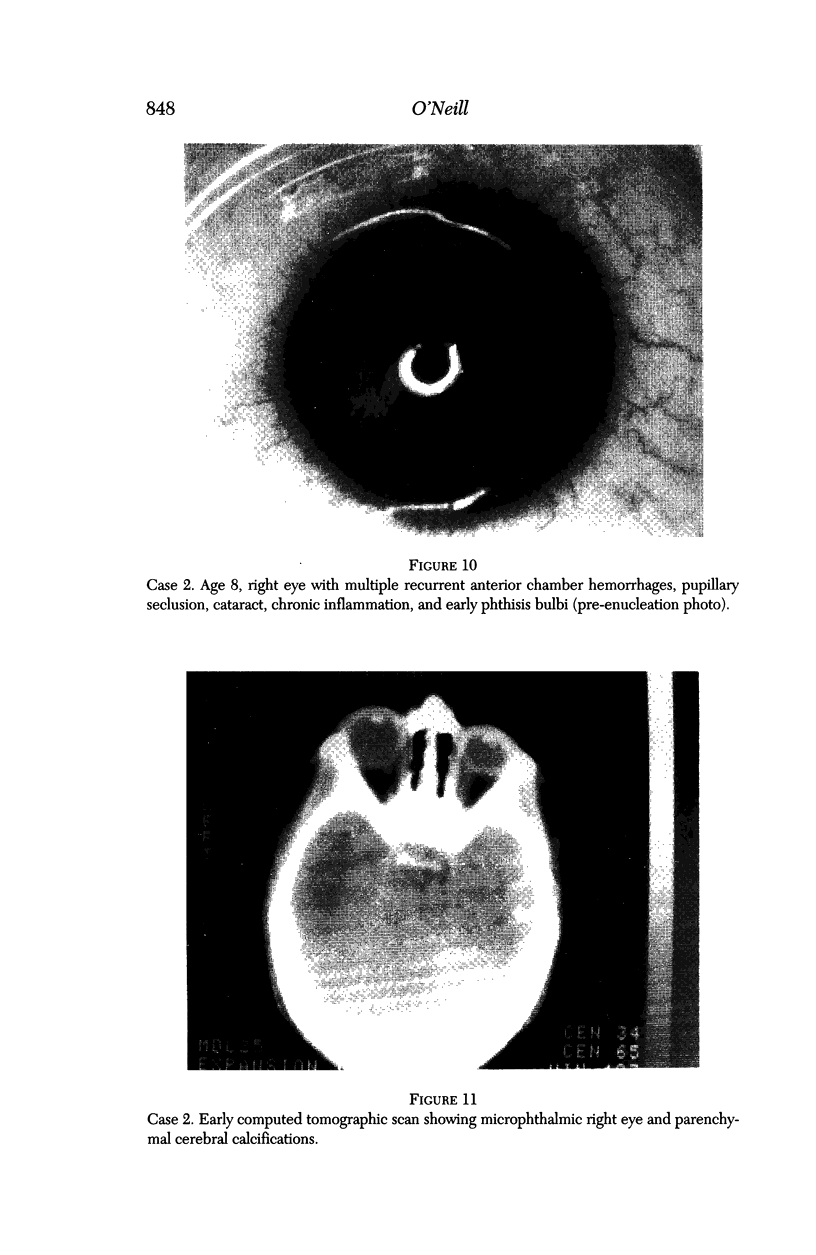

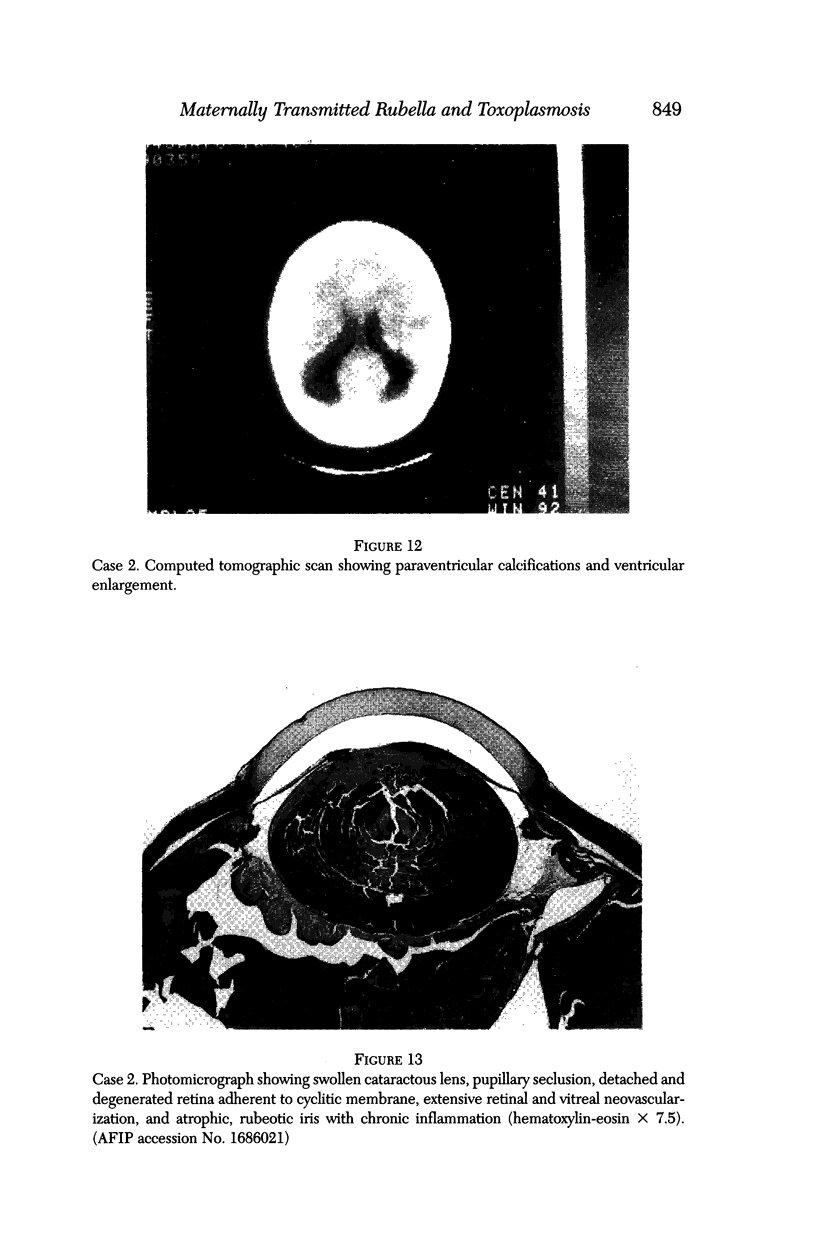

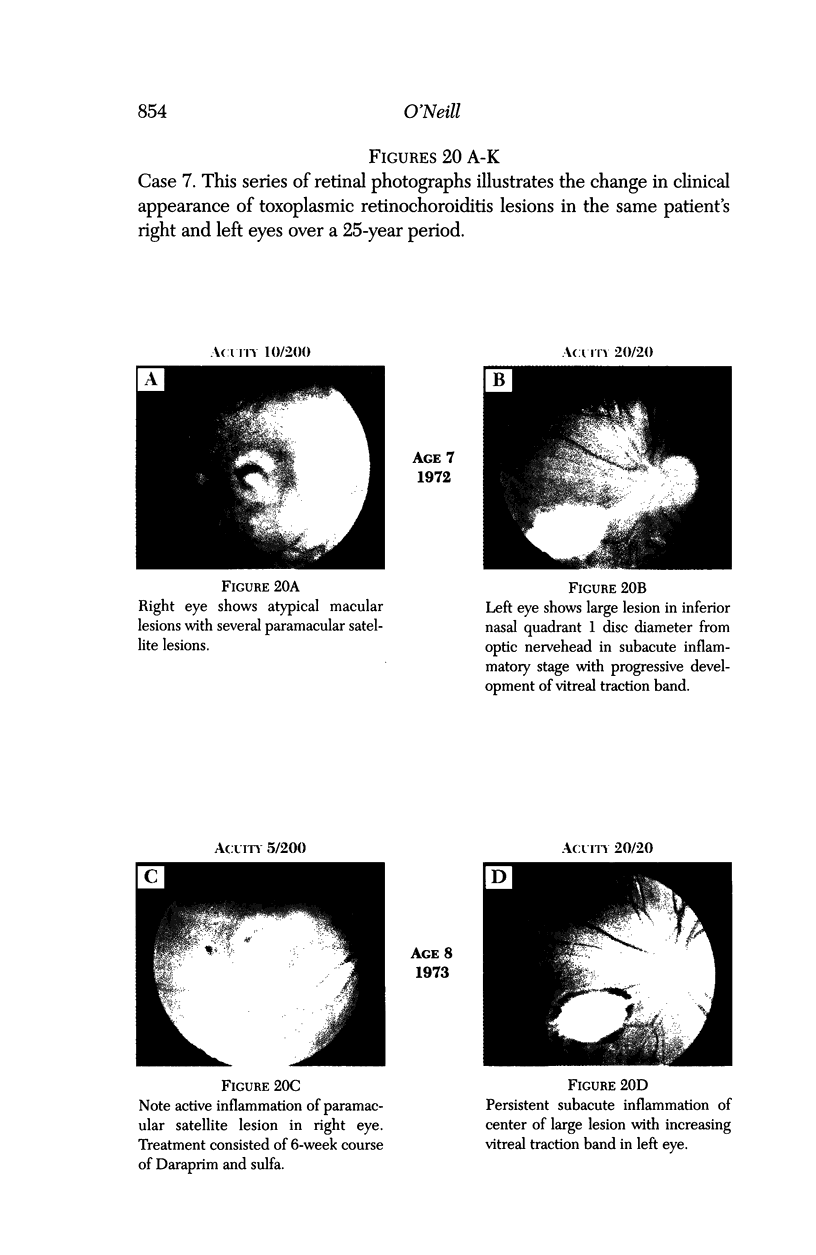

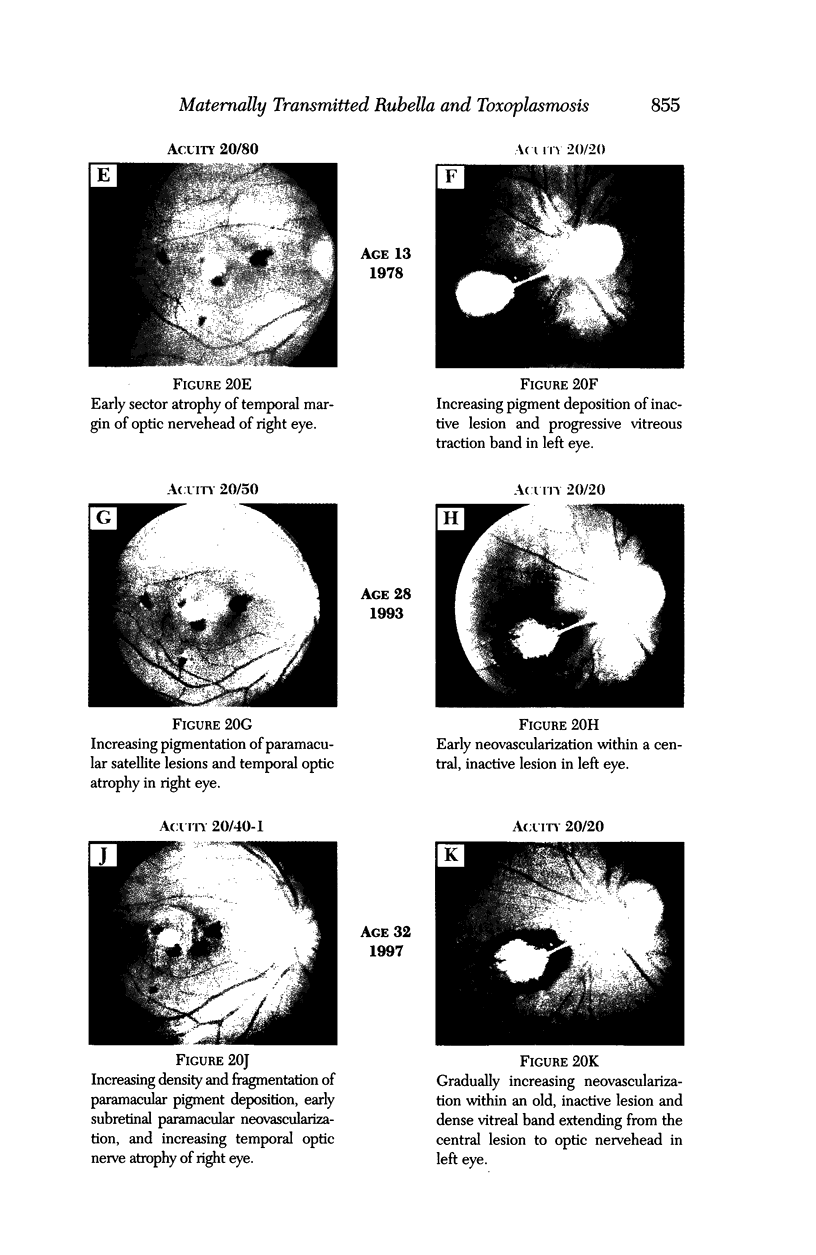

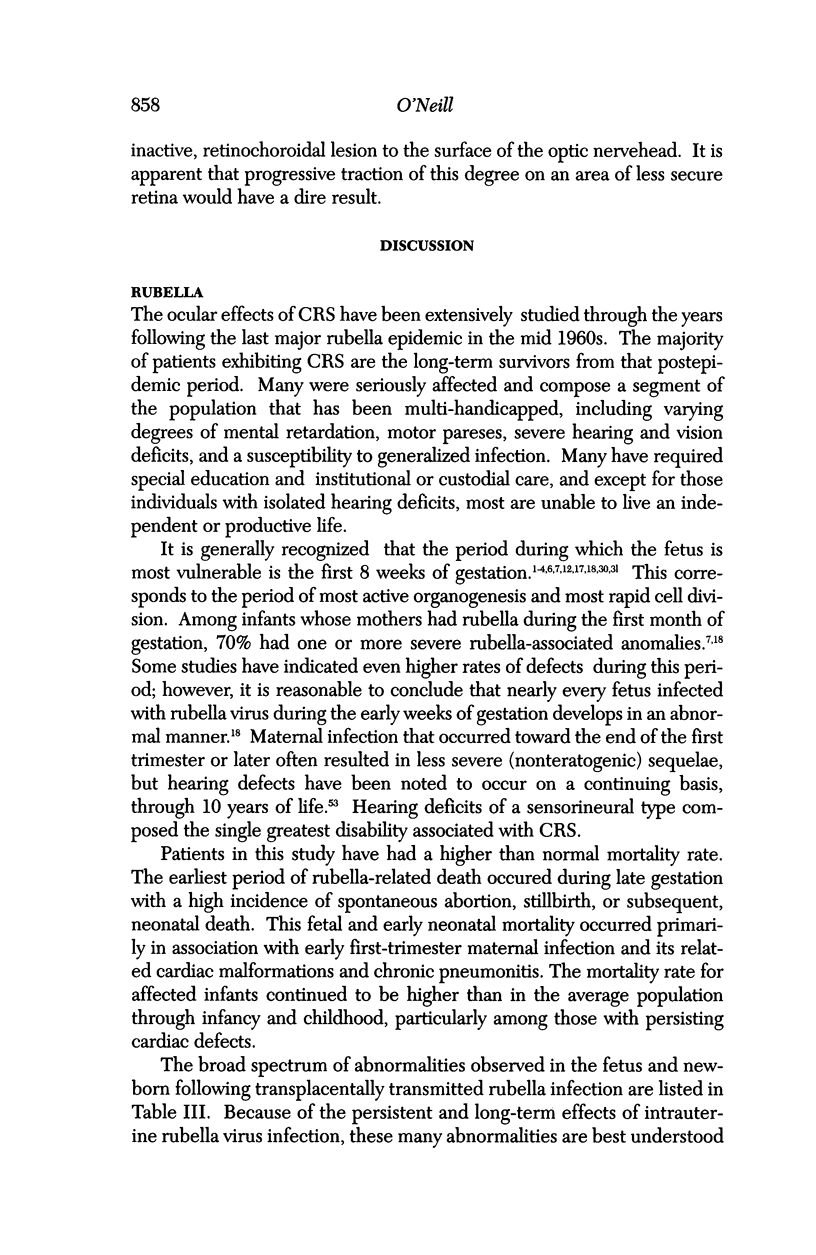

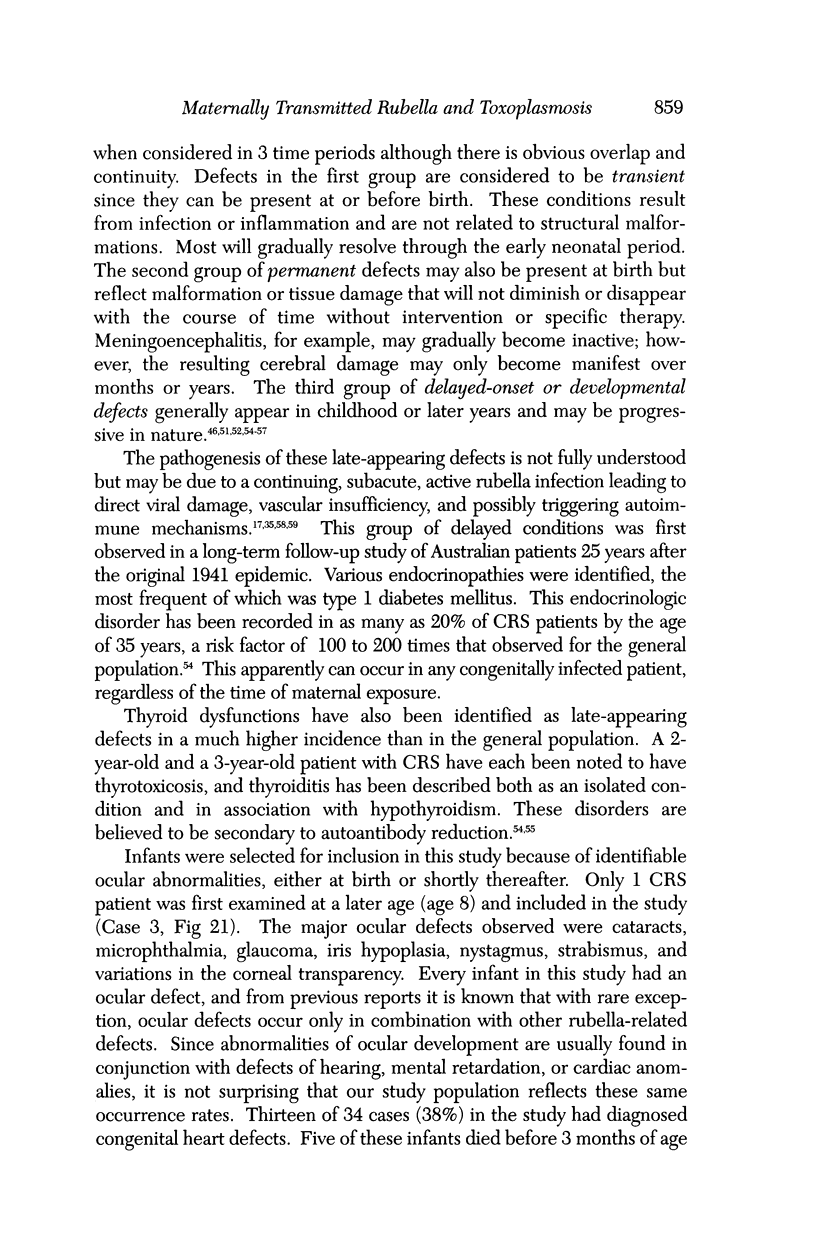

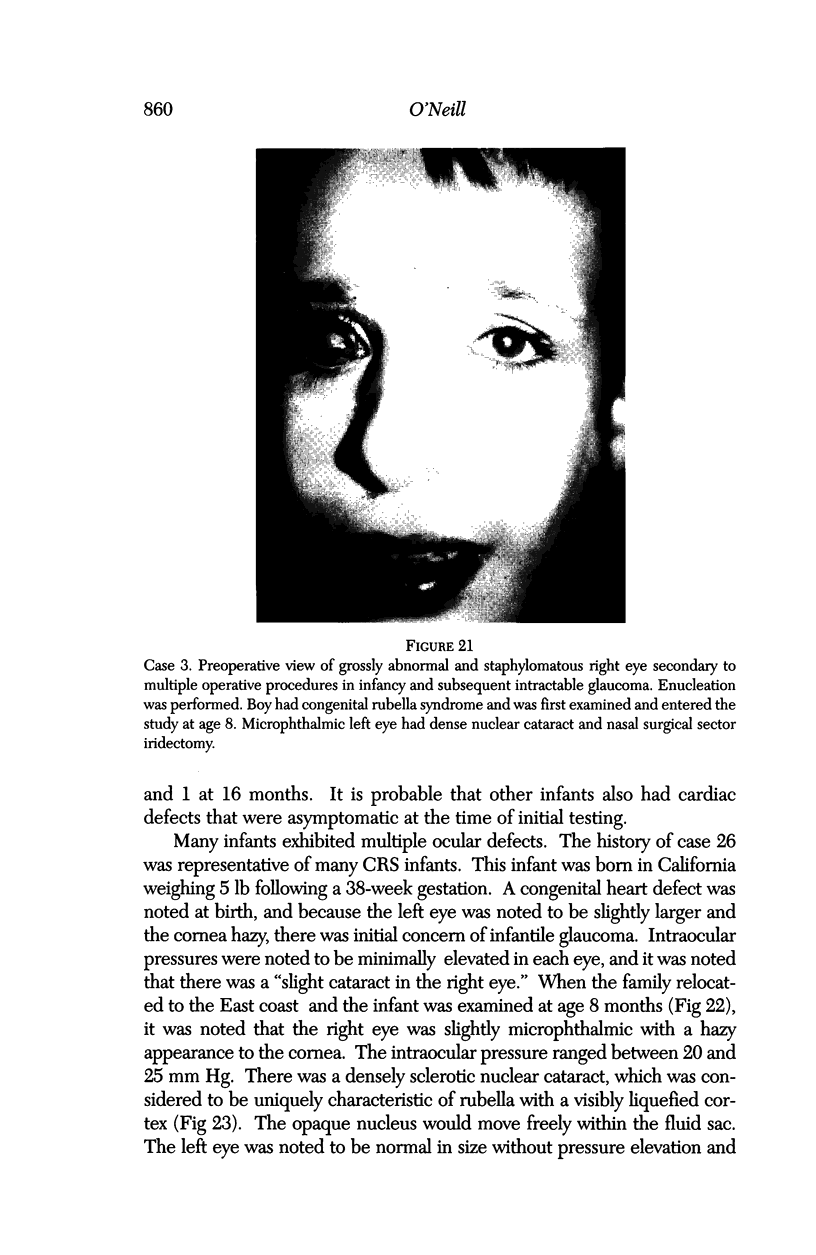

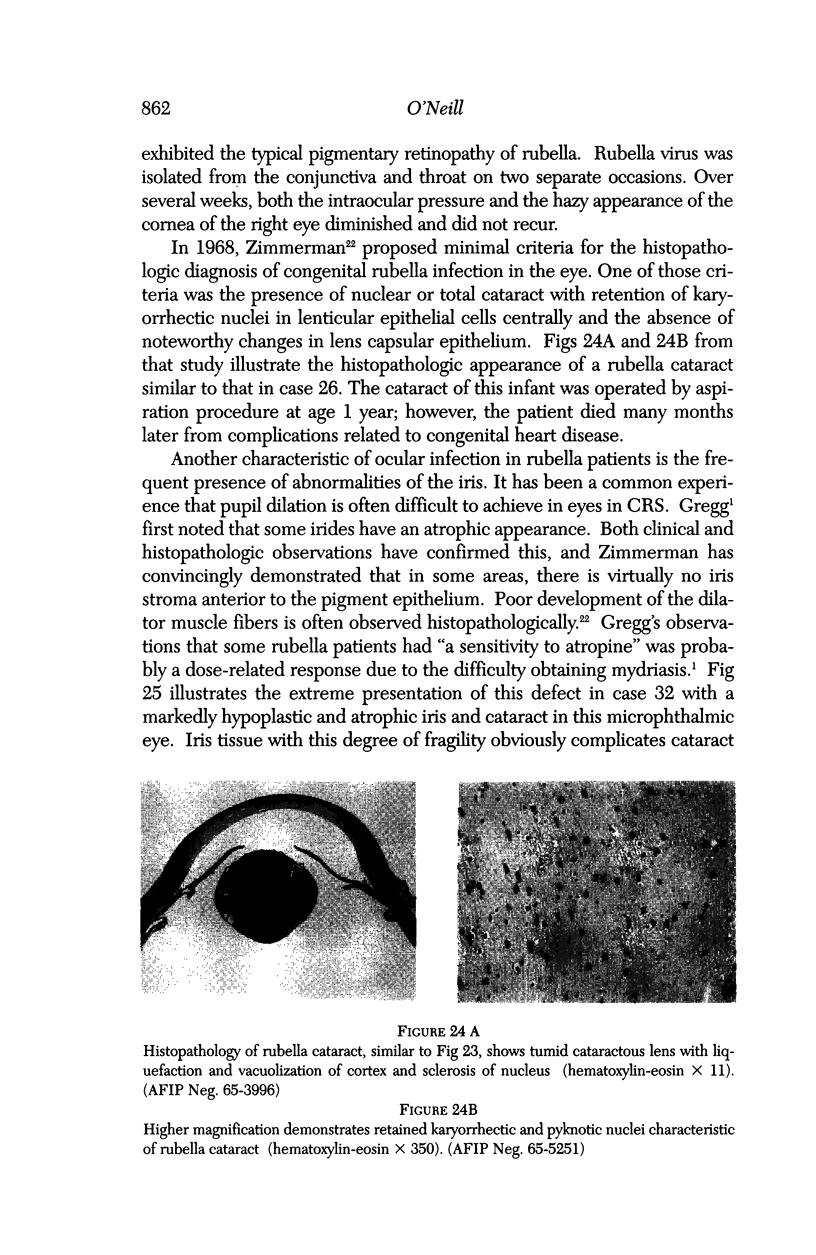

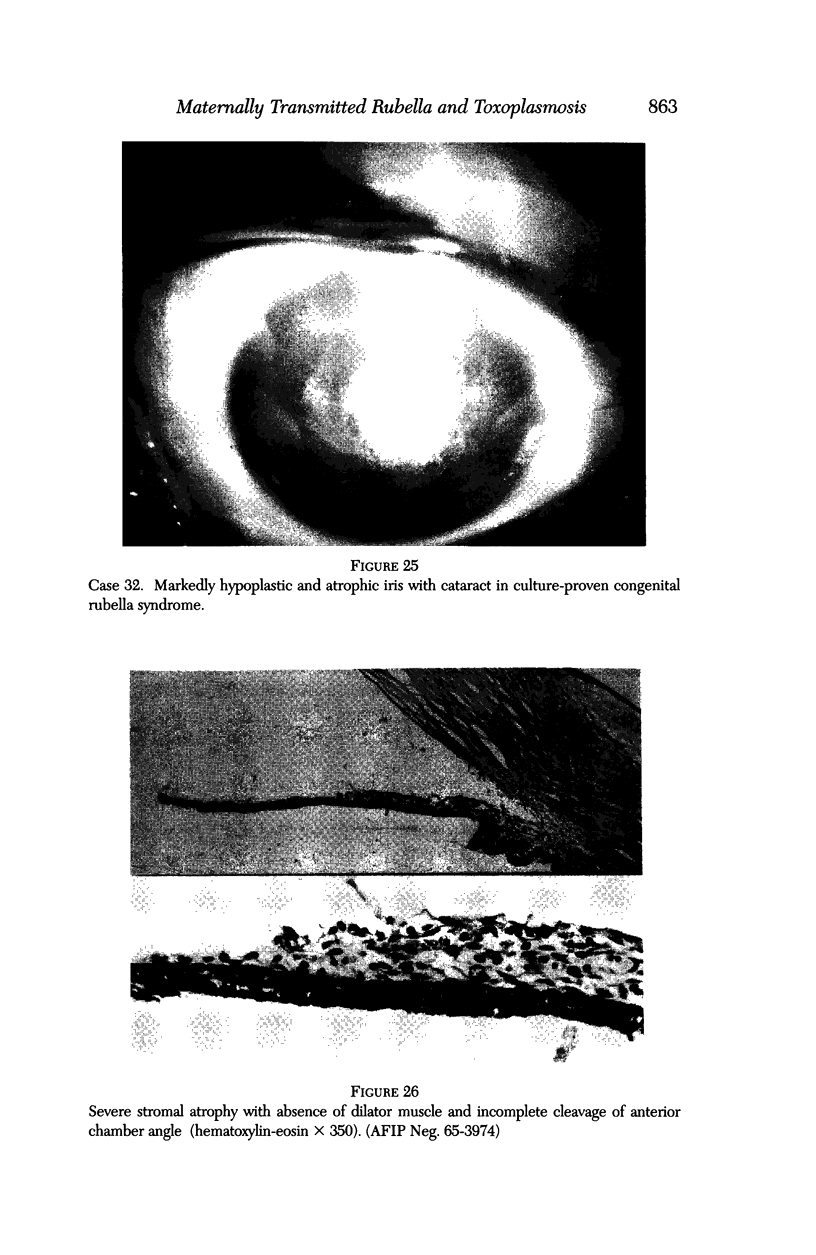

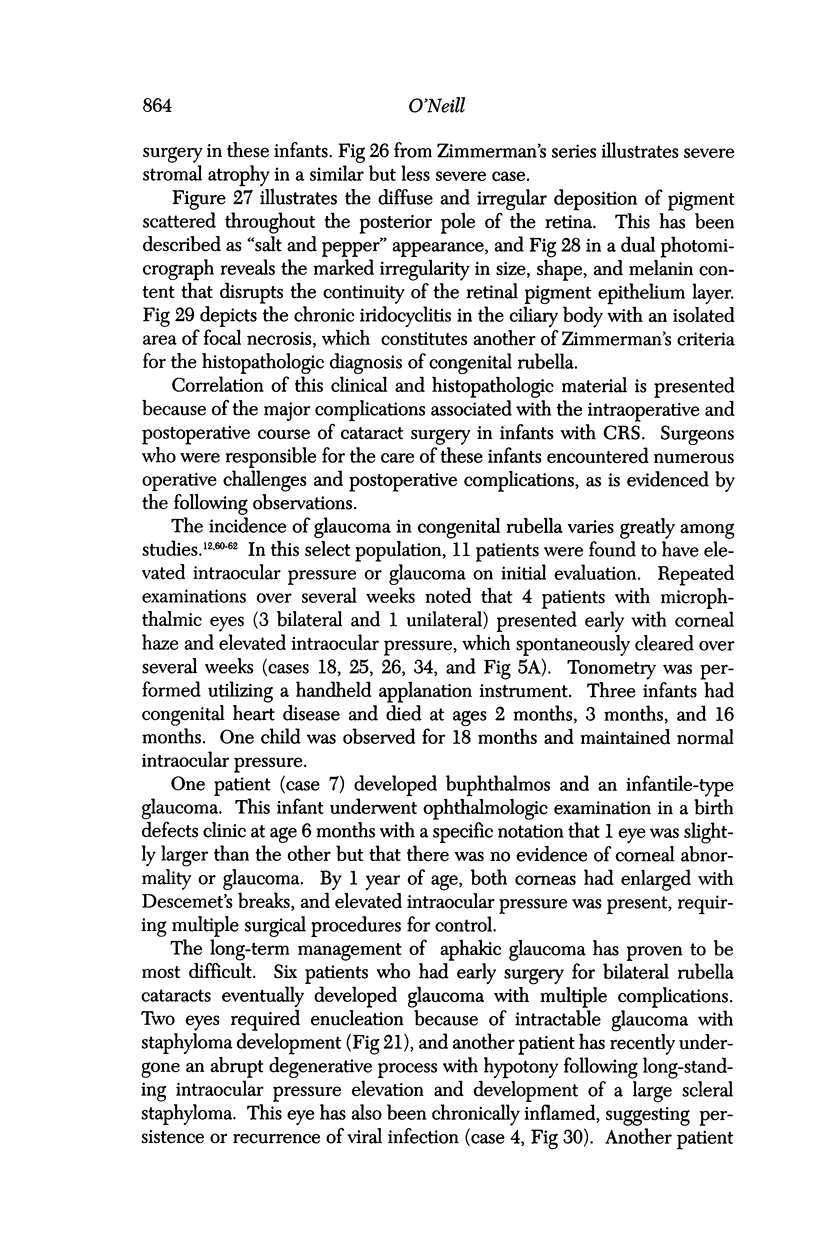

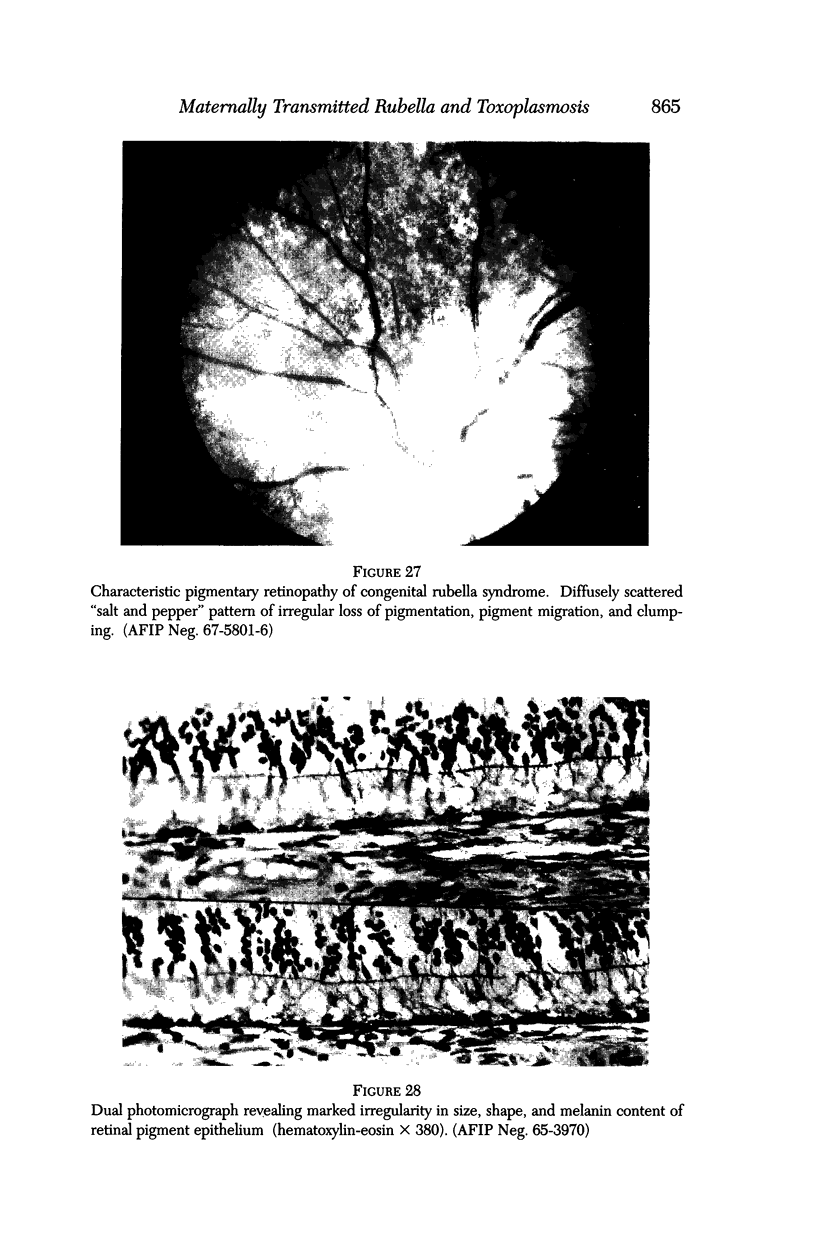

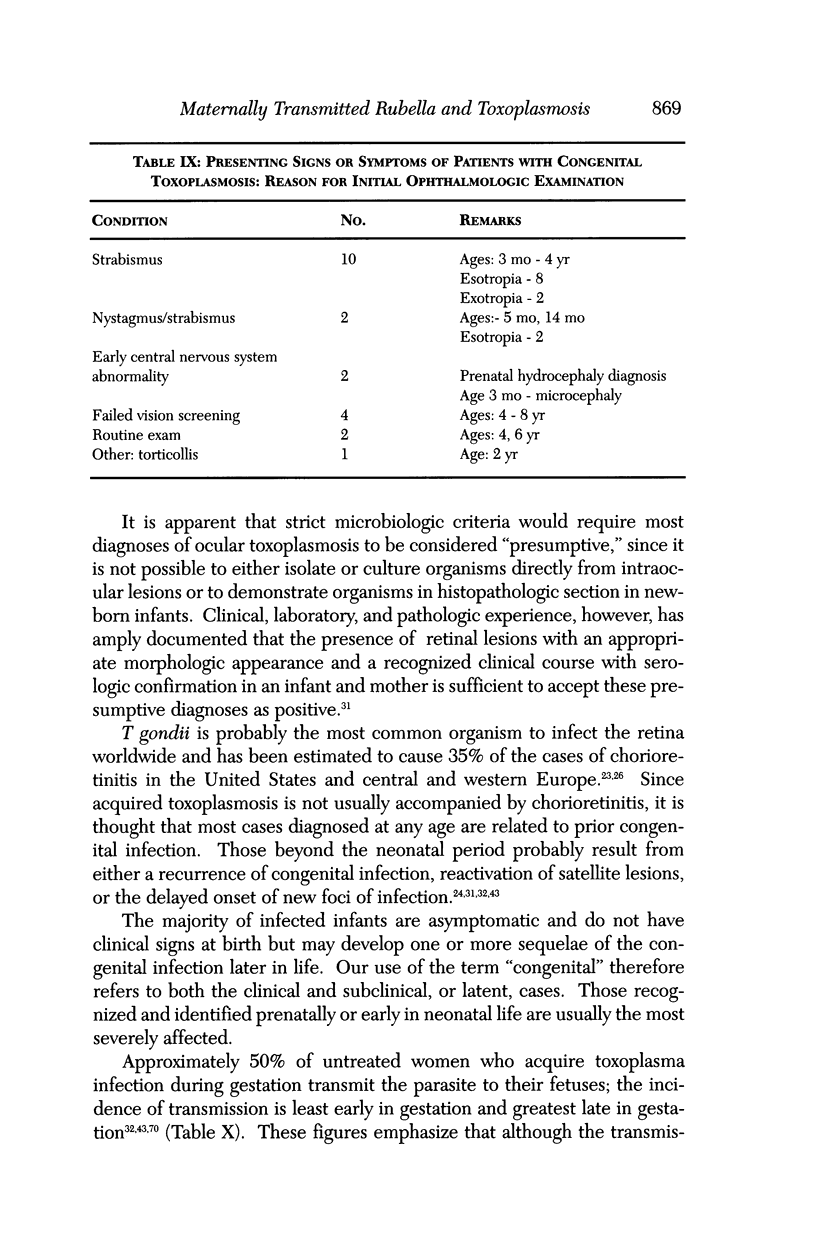

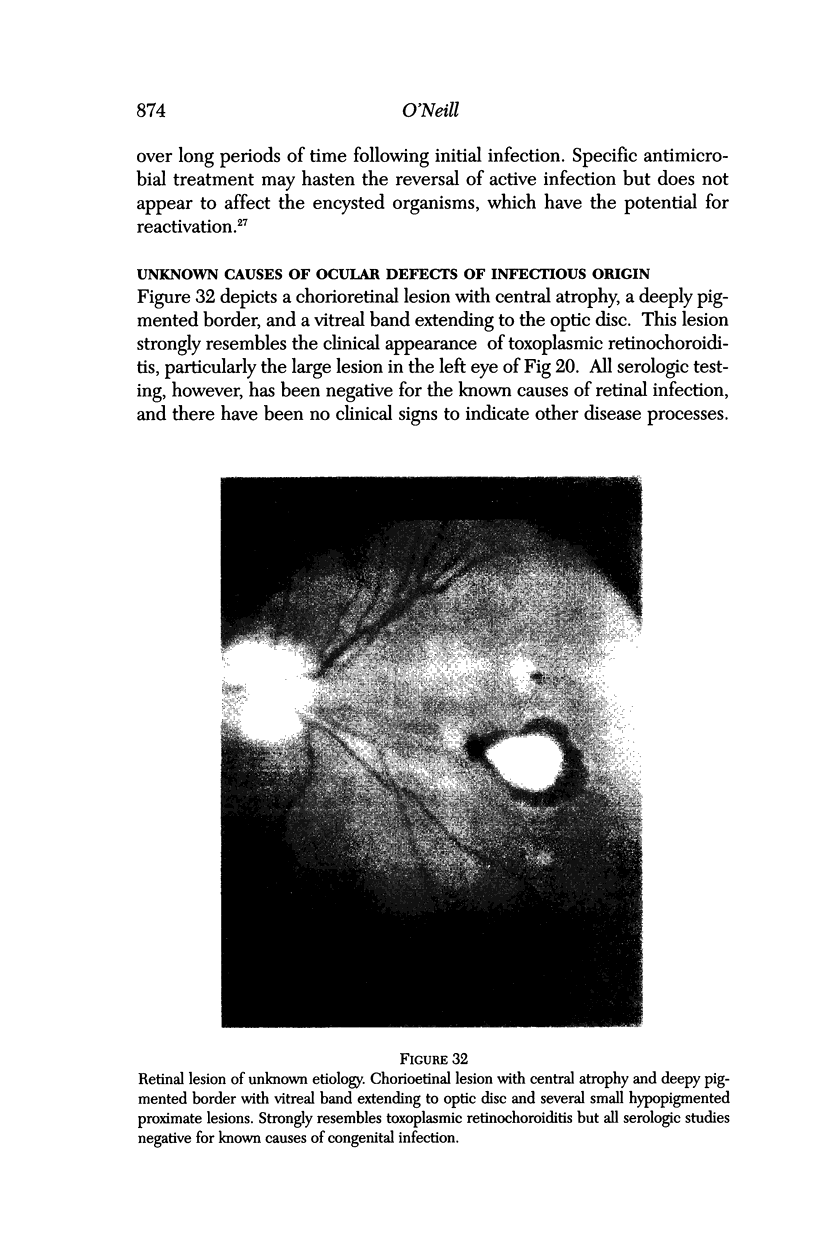

PURPOSE: To study the spectrum of adverse ocular effects which result from maternally transmitted rubella and toxoplasma infection; further, to record the long-term visual and neurodevelopmental outcomes of these 2 major causes of fetal infection. STUDY DESIGN AND PATIENTS: A series of 55 patients with congenital infection have been studied prospectively on a long-term basis. The study group included a cohort of 34 cases with congenital rubella syndrome demonstrated by virus isolation, and 21 cases with a clinical diagnosis of congenital toxoplasmosis and serologic confirmation. All patients had specific disease-related ocular defects. Rubella patients were first identified during or following the last major rubella epidemic in 1963-1964, and some have been followed serially since that time. A separate study group of representative toxoplasmosis patients presented for examination and diagnosis at varying time periods between 1967 and 1991. OBSERVATIONS AND RESULTS: This study confirms that a broad spectrum of fetal injury may result from intrauterine infection and that both persistent and delayed-onset effects may continue or occur as late as 30 years after original infection. Many factors contribute to the varied outcome of prenatal infection, the 2 most important being the presence of maternal immunity during early gestation and the stage of gestation during which fetal exposure occurs in a nonimmune mother. RUBELLA: As a criteria of inclusion, all 34 rubella patients in this study exhibited one or more ocular defects at the time of birth or in the immediate neonatal period. Cataracts were present in 29 (85%) of the 34, of which 21 (63%) were bilateral. Microphthalmia, the next most frequent defect, was present in 28 (82%) of the 34 infants and was bilateral in 22 (65%). Glaucoma was recorded in 11 cases (29%) and presented either as a transient occurrence with early cloudy cornea in microphthalmic eyes (4 patients), as the infantile type with progressive buphthalmos (1 patient), or as a later-onset, aphakic glaucoma many months or years following cataract aspiration in 11 eyes of 6 patients. Rubella retinopathy was present in the majority of patients, although an accurate estimate of its incidence or laterality was not possible because of the frequency of cataracts and nystagmus and the difficulty in obtaining adequate fundus examination. TOXOPLASMOSIS: Twenty-one patients with congenital toxoplasmosis have been examined and followed for varying time periods, 7 for 20 years or more. The major reason for initial examination was parental awareness of an ocular deviation. Twelve children (57%) presented between the ages of 3 months and 4 years with an initial diagnosis of strabismus, 9 of whom had minor complaints or were diagnosed as part of routine examinations. All cases in this study have had evidence of retinochoroiditis, the primary ocular pathology of congenital toxoplasmosis. Two patients had chronic and recurrent inflammation with progressive vitreal traction bands, retinal detachments, and bilateral blindness. Macular lesions were always associated with central vision loss; however, over a period of years visual acuity gradually improved in several patients. Individuals with more severe ocular involvement were also afflicted with the most extensive central nervous system deficits, which occurred following exposure during the earliest weeks of gestation. CONCLUSIONS: Although congenital infection due to rubella virus has been almost completely eradicated in the United States, the long-term survivors from the prevaccination period continue to experience major complications from their early ocular and cerebral defects. They may be afflicted by the persistence of virus in their affected organs and the development of late manifestations of their congenital infection. Congenital toxoplasmosis continues to be the source of major defects for 3,000 to 4,100 infants in the United States each year; the spectrum of defects is wide and may vary from blindness and severe mental retardation to minor retinochoroidal lesions of little consequence. Effective solutions for either the prevention or treatment of congenital toxoplasmosis have not been developed in this country but are under intensive and continuing investigation.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Alford C. A., Jr, Kanich L. S. Congenital rubella: a review of the virologic and serologic phenomena occurring after maternal rubella in the first trimester. South Med J. 1966 Jun;59(6):745–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boger W. P., 3rd Late ocular complications in congenital rubella syndrome. Ophthalmology. 1980 Dec;87(12):1244–1252. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(80)35097-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boger W. P., 3rd, Petersen R. A., Robb R. M. Keratoconus and acute hydrops in mentally retarded patients with congenital rubella syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1981 Feb;91(2):231–233. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(81)90179-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boger W. P., 3rd, Petersen R. A., Robb R. M. Spontaneous absorption of the lens in the congenital rubella syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol. 1981 Mar;99(3):433–434. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1981.03930010435007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrousos G. A., Parks M. M., O'Neill J. F. Incidence of chronic glaucoma, retinal detachment and secondary membrane surgery in pediatric aphakic patients. Ophthalmology. 1984 Oct;91(10):1238–1241. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(84)34161-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper L. Z., Green R. H., Krugman S., Giles J. P., Mirick G. S. Neonatal thrombocytopenic purpura and other manifestations of rubella contracted in utero. Am J Dis Child. 1965 Oct;110(4):416–427. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1965.02090030436011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmonts G., Daffos F., Forestier F., Capella-Pavlovsky M., Thulliez P., Chartier M. Prenatal diagnosis of congenital toxoplasmosis. Lancet. 1985 Mar 2;1(8427):500–504. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)92096-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutman A. F., Grizzard W. S. Rubella retinopathy and subretinal neovascularization. Am J Ophthalmol. 1978 Jan;85(1):82–87. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)76670-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folk J. C., Lobes L. A. Presumed toxoplasmic papillitis. Ophthalmology. 1984 Jan;91(1):64–67. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(84)34329-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank K. E., Purnell E. W. Subretinal neovascularization following rubella retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1978 Oct;86(4):462–466. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(78)90290-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GREEN R. H., BALSAMO M. R., GILES J. P., KRUGMAN S., MIRICK G. S. STUDIES ON THE EXPERIMENTAL TRANSMISSION, CLINICAL COURSE, EPIDEMIOLOGY AND PREVENTION OF RUBELLA. Trans Assoc Am Physicians. 1964;77:118–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Givens K. T., Lee D. A., Jones T., Ilstrup D. M. Congenital rubella syndrome: ophthalmic manifestations and associated systemic disorders. Br J Ophthalmol. 1993 Jun;77(6):358–363. doi: 10.1136/bjo.77.6.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOGAN M. J., KIMURA S. J., O'CONNOR G. R. OCULAR TOXOPLASMOSIS. Arch Ophthalmol. 1964 Nov;72:592–600. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1964.00970020592003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOGAN M. J. Ocular toxoplasmosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1958 Oct;46(4):467–494. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(58)91127-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOGAN M. J., ZWEIGART P. A., LEWIS A. Recovery of toxoplasma from a human eye. AMA Arch Ophthalmol. 1958 Oct;60(4 Pt 1):548–554. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1958.00940080566004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertzberg R. Twenty-five-year follow-up of ocular defects in congenital rubella. Am J Ophthalmol. 1968 Aug;66(2):269–271. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(68)92072-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson D. D., Whitehead R. L. Effect of maternal rubella on hearing and vision: a twenty year post-epidemic study. Am Ann Deaf. 1989 Jul;134(3):232–242. doi: 10.1353/aad.2012.0670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keith C. G. Congenital choroido-retinitis and cerebral damage from unidentified infective agents. Med J Aust. 1974 Feb 9;1(6):177–181. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1974.tb50786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koppe J. G., Loewer-Sieger D. H., de Roever-Bonnet H. Results of 20-year follow-up of congenital toxoplasmosis. Lancet. 1986 Feb 1;1(8475):254–256. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)90785-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAWRENCE G. H., BASHANT G. H. BILATERAL PULMONARY RESECTION FOR METASTATIC HEPATOMA. JAMA. 1965 Jan 11;191:139–140. doi: 10.1001/jama.1965.03080020067027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh E. D., Menser M. A. A fifty-year follow-up of congenital rubella. Lancet. 1992 Aug 15;340(8816):414–415. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)91483-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mets M. B., Holfels E., Boyer K. M., Swisher C. N., Roizen N., Stein L., Stein M., Hopkins J., Withers S., Mack D. Eye manifestations of congenital toxoplasmosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996 Sep;122(3):309–324. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)72057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor G. R. Manifestations and management of ocular toxoplasmosis. Bull N Y Acad Med. 1974 Feb;50(2):192–210. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill J. F., Costenbader F. D. Aspiration procedure for congenital cataracts: its advantages and complications. South Med J. 1971 Feb;64(2):226–232. doi: 10.1097/00007611-197102000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill J. F. Strabismus in congenital rubella. Management in the presence of brain damage. Arch Ophthalmol. 1967 Apr;77(4):450–454. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1967.00980020452007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks M. M., Hiles D. A. Management of infantile cataracts. Am J Ophthalmol. 1967 Jan;63(1):10–19. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(67)90575-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins E. S. Ocular toxoplasmosis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1973 Jan;57(1):1–17. doi: 10.1136/bjo.57.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao N. A., Font R. L. Toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis: electron-microscopic and immunofluorescence studies of formalin-fixed tissue. Arch Ophthalmol. 1977 Feb;95(2):273–277. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1977.04450020074012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SIGURJONSSON J. Rubella and congenital cataract blindness. Med J Aust. 1962 Apr 21;49(1):588–590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabin A. B., Feldman H. A. Dyes as Microchemical Indicators of a New Immunity Phenomenon Affecting a Protozoon Parasite (Toxoplasma). Science. 1948 Dec 10;108(2815):660–663. doi: 10.1126/science.108.2815.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sears M. L. Congenital glaucoma in neonatal rubella. Br J Ophthalmol. 1967 Nov;51(11):744–748. doi: 10.1136/bjo.51.11.744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sever J. L., Ellenberg J. H., Ley A. C., Madden D. L., Fuccillo D. A., Tzan N. R., Edmonds D. M. Toxoplasmosis: maternal and pediatric findings in 23,000 pregnancies. Pediatrics. 1988 Aug;82(2):181–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sever J. L., Nelson K. B., Gilkeson M. R. Rubella epidemic, 1964: effect on 6,000 pregnancies. Am J Dis Child. 1965 Oct;110(4):395–407. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1965.02090030415009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sever J. L., South M. A., Shaver K. A. Delayed manifestations of congenital rubella. Rev Infect Dis. 1985 Mar-Apr;7 (Suppl 1):S164–S169. doi: 10.1093/clinids/7.supplement_1.s164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- South M. A., Sever J. L. Teratogen update: the congenital rubella syndrome. Teratology. 1985 Apr;31(2):297–307. doi: 10.1002/tera.1420310216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILDER H. C. Toxoplasma chorioretinitis in adults. AMA Arch Ophthalmol. 1952 Aug;48(2):127–136. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1952.00920010132001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werk R. How does Toxoplasma gondii enter host cells? Rev Infect Dis. 1985 Jul-Aug;7(4):449–457. doi: 10.1093/clinids/7.4.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson C. B., Remington J. S., Stagno S., Reynolds D. W. Development of adverse sequelae in children born with subclinical congenital Toxoplasma infection. Pediatrics. 1980 Nov;66(5):767–774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf A., Cowen D., Paige B. HUMAN TOXOPLASMOSIS: OCCURRENCE IN INFANTS AS AN ENCEPHALOMYELITIS VERIFICATION BY TRANSMISSION TO ANIMALS. Science. 1939 Mar 10;89(2306):226–227. doi: 10.1126/science.89.2306.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff S. M. The ocular manifestations of congenital rubella. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1972;70:577–614. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman L. E. Histopathologic basis for ocular manifestations of congenital rubella syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1968 Jun;65(6):837–862. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(68)92210-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]