Abstract

The GATA-1-like factor Ash1 is a repressor of the HO gene, which encodes an endonuclease that is responsible for mating-type switching in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. A multi-step programme, which involves a macromolecular protein complex, the secondary structure of ASH1 mRNA and the cell cytoskeleton, enables Ash1 to asymmetrically localize to the daughter cell nucleus in late anaphase and to repress HO transcription. The resulting Ash1 activity prevents the daughter cell from switching mating type. How does Ash1 inhibit transcription of HO exclusively in the daughter cell? In this review, a speculative model is proposed and discussed. Through its action as a daughter-specific repressor, Ash1 can be considered to be an ancestral regulator of cell fate in eukaryotes.

Keywords: Ash1, repression, transcription, asymmetry, yeast

Introduction

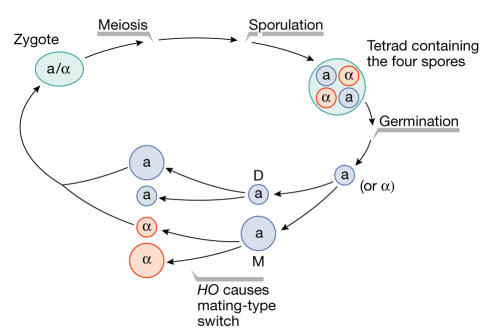

The yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae propagates as haploid a, haploid α or diploid a/α cell types. During its vegetative cycle, the diploid a/α cells undergo meiosis and sporulation to produce an ascus that contains four haploid spores. After germination, two of these spores become cell type a and the other two α. These new a and α spores divide to produce a mother and a daughter cell that have the same mating type as the original spore (Fig 1). During the second mitotic division, the mother switches mating type before S phase, whereas the daughter undergoes DNA duplication, budding and division without switching mating type. Four cells are then generated after two mitotic divisions of the original spore: two with the a mating type and two with the α.

Figure 1.

The budding yeast life cycle. The zygote undergoes meiosis and sporulation. Four spores germinate from the ascus. Each spore divides, producing a mother (M) and a daughter (D) cell without changing mating type. During the second mitotic division, only the mother cell can switch mating type before division.

The cell mating type is determined by the MAT locus. The interconversion between MATa and MATα in homothallic strains is due to the protein product of the HO gene, which is an endonuclease that causes mating-type switching in S. cerevisiae (Herskowitz, 1988; Nasmyth, 1982). Mating-type interconversion occurs exclusively in mother cells, and never in daughters or in spores; indeed, HO is expressed exclusively in mother cells, and only during late G1. Mother/daughter asymmetric HO expression is due to the protein product of the HOspecific repressor gene, known as the asymmetric synthesis of HO (Ash1).

Asymmetric HO expression: the discovery of ASH1 and SHE

How HO is expressed exclusively in mother cells was an intriguing question until the discovery of the ASH1 and the Swi5p-dependent HO expression (SHE) genes by genetic screening. Indeed, these discoveries were a milestone in the study of asymmetry and cell-fate determination in eukaryotic cells. Even in a simple organism such as S. cerevisiae, the fate of the two newborn cells is controlled at each mitotic division by a tight programme, which is orchestrated by the gene products of ASH1 and SHE.

ASH1 was identified through the isolation of mutants, the daughter cells of which were defective in HO repression and so were able to switch mating type. Ash1 is a repressor that inhibits HO transcription through its asymmetric accumulation in the daughter nucleus in late anaphase (Bobola et al, 1996; Sil & Herskowitz, 1996). It is also required for pseudohyphal growth (Chandarlapaty & Errede, 1998). Ash1 contains a region that is highly homologous to the zinc-finger domain of the erythroid cell nuclear protein GATA-1 (Bobola et al, 1996; Sil & Herskowitz, 1996). The GATA motif is a cis regulatory element that is located in enhancers, insulators and the 5′ and 3′ regions of genes. It was first found in globin gene promoters and in other erythroid-expressed non-globin genes (Orkin, 1992). All the GATA-like factors bind to the GATA motif and either activate or repress transcription. Recently, the Ash1-binding consensus sequence, YTGAT, was identified within the HO promoter. This consensus, which is related to the canonical (A/T)GATA(A/G) sequence bound by most GATA factors, is present at least 20 times within the upstream repression sequence 1 (URS1) region of the HO promoter (Maxon & Herskowitz, 2001). The HO promoter can be divided into two cis regulatory regions, URS1 and URS2, which are bound by many regulatory factors and which determine the expression of HO in late G1, exclusively in the mother cell (Nasmyth, 1993). Ash1 has two principal domains: the C-terminal DNA-binding domain, which binds to the YTGAT consensus within URS1 of HO; and the amino-terminal domain, which is devoted to the repression of HO transcription (Maxon & Herskowitz, 2001). Remarkably, the YTGAT consensus of HO is located within a chromosomal region that is highly regulated by nucleosome modifications (Cosma et al, 1999; Krebs et al, 1999); similarly, the GATA motifs of human α- and β-globin gene clusters are found in the locus control regions within nucleosome-modified regions (Orkin, 1992).

The asymmetric accumulation of Ash1 in late anaphase is due to the products of five genes, SHE1-SHE5, each of which has a specific function (Jansen et al, 1996). SHE mutants fail to restrict Ash1 to the daughters therefore HO transcription is repressed in both mother and daughter cells. The She proteins are cytoplasmic, with She1 and She3 accumulating preferentially in the bud. SHE1 encodes the actin-based myosin motor protein She1/Myo4, and SHE5 encodes the septin protein Bni1, which is required for cytokinesis. SHE4 encodes a protein that binds to some motor myosins, including She1/Myo4 (Toi et al, 2003; Wesche et al, 2003), and she4 mutants show defects in endocytosis and in the polarization of the actin cytoskeleton (Wendland et al, 1996). Finally, SHE2 and SHE3 were originally classified as unknown open reading frames (Jansen et al, 1996).

The identification of ASH1 and the SHE genes by genetic screening and the initial studies on the functions of their protein products raised many questions as to how the asymmetric localization of Ash1 is achieved. Many other cases of regulation of gene expression through the asymmetric localization of mRNA are known; to ensure cellular or developmental-stage specificity, the mRNA is actively transported to where the gene product is needed. This is a post-transcriptional level of regulation of gene transcription that occurs in a large variety of organisms (Kloc et al, 2002). The key elements that cooperate in the asymmetric localization of Ash1 have been identified as follows: the cis-acting sequences within ASH1 mRNA; the secondary structure of the ASH1 mRNA; the cell cytoskeleton; a macromolecular complex that includes the She1-3 proteins; and finally, factors that are required for the recognition of ASH1 mRNA in the nucleus and for ASH1 mRNA anchoring and translation at the bud tip.

Localization elements of ASH1 mRNA and the cytoskeleton

Ash1 localizes to the nucleus in the bud in late anaphase. It soon became clear that this asymmetric localization of Ash1 is due to the asymmetric localization of the ASH1 mRNA. The latter is assembled into particles that associate with the cell cortex of the distal tip in late anaphase (Long et al, 1997; Takizawa et al, 1997). Initially, it was observed that the 3′-untranslated region (UTR) of ASH1 mRNA was able to localize a hybrid mRNA (formed by the ASH1 3′-UTR fused either to the LacZ coding sequence or to green fluorescent protein (GFP)) to the bud in uninucleate cells and to the daughters in binucleate cells. This localization was dependent on SHE1 (Long et al, 1997; Takizawa et al, 1997).

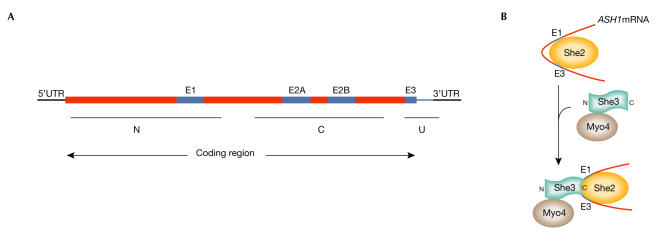

Further studies have shown that there are four minimal localization sequences within the ASH1 mRNA. In addition to the minimal 3′-UTR region, known as E3 or ASH1 U, which spans seven nucleotides before and 67 after the stop codon, there are three elements within the ASH1 mRNA that are present within the carboxy- and N-terminal domains of Ash1. The minimum size of these additional localization elements has been determined, and they have been named as E1 (spanning between nucleotides 598 and 750) in the N-domain, and E2A (between 1044 and 1196) and E2B (between 1175 and 1447) in the C-domain (Fig 2A). When fused to LacZ or GFP reporter genes, all of these elements are equally able to localize the hybrid mRNA in a SHE1-dependent manner (Chartrand et al, 1999; Gonzalez et al, 1999).

Figure 2.

ASH1 mRNA localization domains and RNP complex formation. (A) ASH1 mRNA has four localization domains: E1, E2A, E2B and E3. (B) The RNA-binding protein She2 binds first to ASH1 mRNA, thus allowing the association of the pre-assembled She1/Myo4/She3 complex. C, carboxy-terminal domain; N, amino-terminal domain; U, untranslated region.

The secondary structure within such localization elements is important for their function (Kloc et al, 2002), and the ability of the E3 element to fold into stem-loop-containing doublestranded regions has been studied in detail. This secondary structure is crucial for ASH1 mRNA localization (Bertrand et al, 1998) and mutations in the stem loop of the E3 element can affect the localization of ASH1 mRNA (Chartrand et al, 1999).

The cytoskeleton has a role in the transport of different mRNAs in many organisms. There are two classes of cytoskeletal elements that are involved in cargo functions: actin microfilaments and microtubules (Kloc et al, 2002). The localization of ASH1 mRNA was not affected in the tub2-401 mutant, which causes the disruption of astral microtubules. However, disruption of actin-dependent motor proteins, such as She1/Myo4, tropomyosin, profilin and actin, abolished ASH1 mRNA localization to the bud (Long et al, 1997). In addition, disruption of the cytoskeleton by latrunculin A, but not of microtubules by nocodazole, affected ASH1 mRNA localization and Ash1 asymmetry (Takizawa et al, 1997). The She proteins regulate various functions of the cytoskeleton (Jansen et al, 1996) and indeed, in she1, she2, she3 and she4 mutants, not only Ash1, but also ASH1 mRNA were equally distributed in mothers and daughters (Long et al, 1997).

A ribonucleoprotein complex localizes ASH1 mRNA

Another step in the regulation of the asymmetric distribution of Ash1 is the activity of a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex formed by the She proteins and ASH1 mRNA. Numerous studies from many groups have suggested the following model of RNP assembly: She2, an RNA-binding protein, binds to ASH1 mRNA first, which allows the association of a pre-assembled She1/Myo4/She3 complex. Significantly, She2 associates with ASH1 mRNA independent of the other She proteins. She3 is an adaptor protein that binds She1/Myo4 through its N-terminal domain and the ASH1 E1 and E3 elements via its C-terminal domain (Fig 2B). The assembled RNP, and therefore ASH1 mRNA, is transported by She1/Myo4 to the distal tip along the actin filaments (Bohl et al, 2000; Long et al, 2000; Takizawa & Vale, 2000).

In the RNP complex, She2 was proposed to be the cargo of the ASH1 mRNA as it moves into and out of the nucleus. Kruse and colleagues demonstrated that a small fraction of She2 shuttles into the nucleus, and can be exported into the cytoplasm in an mRNA-dependent manner (Kruse et al, 2002). In a mex67-5ts mutant, in which mRNA export is blocked, She2 was sequestered in the nucleus and the cells failed to localize She1/Myo4, which is one of the components of the RNP, to the bud. Similarly, She1/Myo4 is mislocalized in a she2ΔN70 mutant (which encodes a truncated She2 that lacks the 70 N-terminal amino acids): the truncated she2ΔN70 failed to co-precipitate ASH1 mRNA and accumulated in the nucleus (Kruse et al, 2002). These results, however, remain controversial, as Gonsalvez and colleagues reported that the nuclear export of She2 was independent of both mRNA transport and the ability of She2 to bind mRNA (Gonsalvez et al, 2003).

In terms of ASH1 mRNA recognition, She2 is not unique; another key factor, Loc1, resides strictly in the nucleus and contributes to the asymmetric localization of ASH1 mRNA. Loc1 has a high affinity for double-stranded RNAs, and can interact non-specifically with RNA-containing stem loops. However, it interacts specifically (with higher affinity) with the E3 domain and with full-length ASH1 mRNA; these interactions are dependent on the structural integrity of the stem-loop elements. In a loc1 mutant, ASH1 mRNA and Ash1 itself are symmetrically localized in mother and daughter cells, which implies that Loc1 is important for the correct localization of ASH1 mRNA (Long et al, 2001).

Anchoring and translation of ASH1 mRNA

The anchoring of ASH1 mRNA to the bud tip and its consequent translation are additional control steps in its asymmetric localization. Khd1 is involved in this process owing to its co-localization and physical binding to ASH1 mRNA. A genetic interaction has been demonstrated between the KHD1 and SHE genes; indeed, over-expression of KHD1 suppressed the effects of she mutations on HO expression by reducing the concentration of Ash1. This was due to the decreased anchoring of ASH1 mRNA. Therefore, KHD1 is involved in the translational control of ASH1 mRNA, through its role in anchoring ASH1 mRNA at the distal cortex (Irie et al, 2002). Furthermore, a stop codon inserted immediately after the AUG of the ASH1 coding region did not affect the stability of the mRNA, but instead impaired the localization of the untranslated mRNA (Gonzalez et al, 1999). As ASH1 mRNA is highly mobile within the bud, it is possible that although the untranslatable mRNA reaches the distal cortex of the daughter, it does not remain there because it is not properly anchored. Thus, the concentration of Ash1 is essential for efficient anchoring of its mRNA; indeed, a hybrid mRNA encoded by a GFPsTOP-ASH1 construct, which only translates GFP, was symmetrically distributed in mother and daughter cells (Gonzalez et al, 1999).

The rate of translation is also important for the efficient localization of Ash1; a decreased rate of ASH1 mRNA translation was observed following the introduction of a short stem loop in the 5′-UTR, which resulted in an increase in Ash1 localization (Chartrand et al, 1999). The 5′-UTR of mRNA is a fundamental regulatory element during the initial steps of protein synthesis in eukaryotes as it facilitates start-codon recognition by ribosomes (Preiss & Hentze, 2003). The introduction of a stem loop in the 5′-UTR interferes with the correct assembly of the translational machinery, which leads to a slowing down, or even a block, of translation. Remarkably, a temperaturesensitive translational control mechanism was described for prfA mRNA, the Listeria monocytogene virulence-activating transcription factor. At 30° C, the 5′-UTR of the prfA mRNA formed a stem-loop structure that blocked ribosome binding, whereas at 37° C the loop melted, thus allowing translation (Johansson et al, 2002).

Chartrand and colleagues demonstrated that the disruption of all four localization elements resulted in the de-localization of the ASH1 mRNA and its protein product. Additionally, the four elements were functionally redundant in their ability to localize ASH1 mRNA, and their effects were independent of their positions within the ASH1 mRNA. By contrast, their positions were essential for localization of the Ash1 protein to the bud (Chartrand et al, 2002). This mechanism was shown to be correlated to the rate of translation; the faster ASH1 mRNA is translated, the more likely that Ash1 enters the mother-cell nucleus and thus loses its asymmetric localization. Chartrand and colleagues suggested that the position of the localization elements interferes with ribosome elongation and thus with the rate of translation. Indeed, when the elements were moved to the 3′-UTR of ASH1 mRNA, this was asymmetrically localized, but the protein itself was not because of an increased rate of translation (Chartrand et al, 2002).

Movement of ASH1 mRNA within the bud

Once transported to the bud, ASH1 mRNA is mobile. It moves within the cortical region of the bud tip and from the cortical cap to the neck. The path of this movement and its rate have been measured by visualizing a fluorescent 'particle' (formed by the bacteriophage coat protein MS2 fused to GFP and the 3′-UTR of ASH1) in the bud. However, particle formation and localization were inhibited in she mutants (Beach & Bloom, 2001; Beach et al, 1999; Bertrand et al, 1998).

Living cell time-lapse experiments revealed cell-cycle-dependent movements of the particle. From late anaphase to cytokinesis, the particle moved from the cortical region of large budded cells to the bud neck, and finally from there to the newly forming bud site. Therefore, the emerging bud contained the particle at the cortical cap. The particle moved with different velocities within the bud. In cells that lack Bud6/Aip3 or She5, which are involved in polarity establishment and actin organization, the particle migrated to the bud but did not remain stably localized at the bud cup. In these mutants, the movement and the rate of excursions out of the cortical cup were much higher than in wild-type cells. This observation led to the conclusion that Bud6/Aip3 or She5 are required for the anchoring of ASH1 mRNA at the cortical bud cup (Beach & Bloom, 2001; Beach et al, 1999).

The goal: Ash1 represses HO transcription in daughters

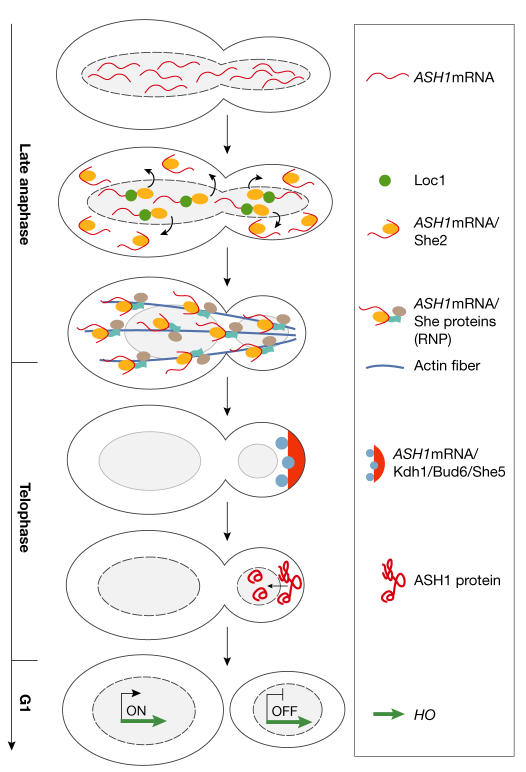

All the events described above lead to the final goal: the repression of HO transcription in daughter cells. This results in the inhibition of mating-type switching, as follows (Fig 3).

Figure 3.

The asymmetric accumulation of Ash1 represses HO in daughters. ASH1 mRNA is recognized by Loc1 and She2 and transported in the cytoplasm, where it is coupled to the other She proteins to form the ribonucleoprotein (RNP; ASH1 mRNA/She2/She3/Myo4). The RNP is transported along the actin cables to the distal tip, where the anchoring and translation of ASH1 mRNA occurs. Finally, Ash1 enters the daughter nucleus, where it represses HO.

In late anaphase, cyclinB/Cdk1 degradation and Cdc14 activity lead to the de-phosphorylation of the Swi5 nuclear localization signal, which allows Swi5 to enter both mother and daughter nuclei (Visintin et al, 1998). Swi5 binds the ASH1 and HO promoters in both cells with similar kinetics, but although ASH1 is immediately transcribed to start the HO repression program, the transcription of HO is delayed until late G1.

ASH1 mRNA is recognised in both mother and daughter nuclei by the nuclear RNA-binding proteins Loc1 and She2. It is then transported through nuclear pores into the cytoplasm, where it is coupled to other She proteins to form the RNP. This macromolecular complex is transported through the bud neck along actin cables and is asymmetrically localized to the distal tip of the bud, where it is anchored by factors such as Khd1 and/or Bud6/Aip3 and/or She5. ASH1 mRNA is finally translated and Ash1 enters the daughter nucleus, where it binds its consensus sequences within URS1 and represses HO transcription by aborting all of the events following Swi5 association (Gonzalez et al, 1999; Irie et al, 2002; Long et al, 2001; Maxon & Herskowitz, 2001; Munchow et al, 1999).

Meanwhile, at the HO promoter in the mother cell, ASH1 transcription has already been accomplished and the following occurs: after Swi5 association, the recruitment of SWI/SNF and SAGA results in the binding of SBF—an HO-specific activator—to the HO promoter, which then recruits the mediator complex. Finally, following the activation of the cyclin kinase Cdk1, RNA PolII and the basal transcription factors can associate with the HO promoter and commence transcription (Cosma, 2002).

Concluding remarks and speculations

What is remarkable about the regulation of ASH1 transcription, translation and Ash1 repression is the temporal window during which all of these events occur. In late anaphase, Swi5 recruits chromatin remodelling and acetylation complexes to the HO promoter in the mother cell, but not in the daughter. However, there have been indications that Swi5 recruits these proteins to the ASH1 promoter in both mother and daughter cells (Krebs et al, 2000). How are these nucleosome-modifying complexes recruited by Swi5 in mother and daughter at ASH1, but only in the mother at HO? It is the time that it takes from Swi5 binding to both promoters to Ash1 synthesis and localization that results in this motherspecific recruitment of SWI/SNF and differential mother/daughter HO expression. Five minutes elapse between Swi5 and Ash1 association with the HO promoter (Cosma et al, 1999). During this time window, the scenario on the HO promoter is frozen in both mother and daughter until all of the factors that regulate ASH1 mRNA nuclear recognition, asymmetric localization, anchoring and translation complete their activities.

The big issue here is what happens at HO during those five minutes that the transcriptional programme continues at ASH1. An explanation could be that because SWI/SNF binds first to the URS1 region and then five minutes later, at the time of Ash1 association, to the URS2 region of the HO promoter (Cosma et al, 1999), Ash1 might impair binding of SWI/SNF to URS2 in daughters, which would ultimately induce the release of the complex from the URS1 region. In the case of ASH1 activation, SWI/SNF might associate at once upon Swi5 recruitment and the transcriptional programme would thus be committed to a rapid progression. Furthermore, all of the events following Swi5 association can occur efficiently at ASH1 because Ash1 specifically represses HO and not the ASH1 gene.

However, once on the promoter, how does Ash1 prevent Swi5 from recruiting SWI/SNF in the daughter cell? It is possible that Ash1 has a role in the control of the affinity and specificity of the DNA, such that the association of the SWI/SNF remodelling complex becomes unstable. Alternatively, Ash1 might itself occupy putative SWI/SNF association sites, or it might even mask a Swi5-binding domain that is responsible for the recruitment of the SWI/SNF remodelling complex, particularly as a physical interaction between Swi5 and SWI/SNF has been detected by co-immunoprecipitation (Neely et al, 1999).

The temporal association of factors is a regulation mechanism of eukaryotic genes, and the activity of Ash1 is clearly modulated by time-dependent events. Moreover, Ash1 itself regulates transcription of HO in a time-dependent manner. The targeting of ASH1 mRNA to the bud is a post-transcriptional mechanism of gene regulation that specifies the cell mating type through HO repression. The asymmetric localization of Ash1 can, therefore, be considered to be a stunning mechanism of cell lineage determination.

Maria Pia Cosma is the recipient of an EMBO Young Investigator Award

References

- Beach DL, Bloom K (2001) ASH1 mRNA localization in three acts. Mol Biol Cell 12: 2567–2577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach DL, Salmon ED, Bloom K (1999) Localization and anchoring of mRNA in budding yeast. Curr Biol 9: 569–578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand E, Chartrand P, Schaefer M, Shenoy SM, Singer RH, Long RM (1998) Localization of ASH1 mRNA particles in living yeast. Mol Cell 2: 437–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobola N, Jansen RP, Shin TH, Nasmyth K (1996) Asymmetric accumulation of Ash1p in postanaphase nuclei depends on a myosin and restricts yeast mating-type switching to mother cells. Cell 84: 699–709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohl F, Kruse C, Frank A, Ferring D, Jansen RP (2000) She2p, a novel RNA-binding protein tethers ASH1 mRNA to the Myo4p myosin motor via She3p. EMBO J 19: 5514–5524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandarlapaty S, Errede B (1998) Ash1, a daughter cellspecific protein, is required for pseudohyphal growth of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol 18: 2884–2891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chartrand P, Meng XH, Huttelmaier S, Donato D, Singer RH (2002) Asymmetric sorting of ash1p in yeast results from inhibition of translation by localization elements in the mRNA. Mol Cell 10: 1319–1330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chartrand P, Meng XH, Singer RH, Long RM (1999) Structural elements required for the localization of ASH1 mRNA and of a green fluorescent protein reporter particle in vivo. Curr Biol 9: 333–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosma MP (2002) Ordered recruitment: genespecific mechanism of transcription activation. Mol Cell 10: 227–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosma MP, Tanaka T, Nasmyth K (1999) Ordered recruitment of transcription and chromatin remodeling factors to a cell cycle and developmentally regulated promoter. Cell 97: 299–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonsalvez GB, Lehmann KA, Ho DK, Stanitsa ES, Williamson JR, Long RM (2003) RNA-protein interactions promote asymmetric sorting of the ASH1 mRNA ribonucleoprotein complex. RNA 9: 1383–1399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez I, Buonomo SB, Nasmyth K, von Ahsen U (1999) ASH1 mRNA localization in yeast involves multiple secondary structural elements and Ash1 protein translation. Curr Biol 9: 337–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herskowitz I (1988) Life cycle of the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol Rev 52: 536–553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irie K, Tadauchi T, Takizawa PA, Vale RD, Matsumoto K, Herskowitz I (2002) The Khd1 protein, which has three KH RNA-binding motifs, is required for proper localization of ASH1 mRNA in yeast. EMBO J 21: 1158–1167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen RP, Dowzer C, Michaelis C, Galova M, Nasmyth K (1996) Mother cellspecific HO expression in budding yeast depends on the unconventional myosin myo4p and other cytoplasmic proteins. Cell 84: 687–697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson J, Mandin P, Renzoni A, Chiaruttini C, Springer M, Cossart P (2002) An RNA thermosensor controls expression of virulence genes in Listeria monocytogenes. Cell 110: 551–561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloc M, Zearfoss NR, Etkin LD (2002) Mechanisms of subcellular mRNA localization. Cell 108: 533–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs JE, Fry CJ, Samuels ML, Peterson CL (2000) Global role for chromatin remodeling enzymes in mitotic gene expression. Cell 102: 587–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs JE, Kuo MH, Allis CD, Peterson CL (1999) Cell cycle-regulated histone acetylation required for expression of the yeast HO gene. Genes Dev 13: 1412–1421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruse C, Jaedicke A, Beaudouin J, Bohl F, Ferring D, Guttler T, Ellenberg J, Jansen RP (2002) Ribonucleoprotein-dependent localization of the yeast class V myosin Myo4p. J Cell Biol 159: 971–982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long RM, Gu W, Lorimer E, Singer RH, Chartrand P (2000) She2p is a novel RNA-binding protein that recruits the Myo4p–She3p complex to ASH1 mRNA. EMBO J 19: 6592–6601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long RM, Gu W, Meng X, Gonsalvez G, Singer RH, Chartrand P (2001) An exclusively nuclear RNA-binding protein affects asymmetric localization of ASH1 mRNA and Ash1p in yeast. J Cell Biol 153: 307–318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long RM, Singer RH, Meng X, Gonzalez I, Nasmyth K, Jansen RP (1997) Mating type switching in yeast controlled by asymmetric localization of ASH1 mRNA. Science 277: 383–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxon ME, Herskowitz I (2001) Ash1p is a sitespecific DNA-binding protein that actively represses transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 1495–1500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munchow S, Sauter C, Jansen RP (1999) Association of the class V myosin Myo4p with a localised messenger RNA in budding yeast depends on She proteins. J Cell Sci 112: 1511–1518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasmyth K (1993) Regulating the HO endonuclease in yeast. Curr Opin Genet Dev 3: 286–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasmyth KA (1982) Molecular genetics of yeast mating type. Annu Rev Genet 16: 439–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neely KE, Hassan AH, Wallberg AE, Steger DJ, Cairns BR, Wright AP, Workman JL (1999) Activation domain-mediated targeting of the SWI/SNF complex to promoters stimulates transcription from nucleosome arrays. Mol Cell 4: 649–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orkin SH (1992) GATA-binding transcription factors in hematopoietic cells. Blood 80: 575–581 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preiss T, Hentze MW (2003) Starting the protein synthesis machine: eukaryotic translation initiation. Bioessays 25: 1201–1211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sil A, Herskowitz I (1996) Identification of asymmetrically localized determinant, Ash1p, required for lineagespecific transcription of the yeast HO gene. Cell 84: 711–722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takizawa PA, Sil A, Swedlow JR, Herskowitz I, Vale RD (1997) Actin-dependent localization of an RNA encoding a cell-fate determinant in yeast. Nature 389: 90–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takizawa PA, Vale RD (2000) The myosin motor, Myo4p, binds Ash1 mRNA via the adapter protein, She3p. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 5273–5278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toi H, Fujimura-Kamada K, Irie K, Takai Y, Todo S, Tanaka K (2003) She4p/Dim1p interacts with the motor domain of unconventional myosins in the budding yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell 14: 2237–2249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visintin R, Craig K, Hwang ES, Prinz S, Tyers M, Amon A (1998) The phosphatase Cdc14 triggers mitotic exit by reversal of Cdk-dependent phosphorylation. Mol Cell 2: 709–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendland B, McCaffery JM, Xiao Q, Emr SD (1996) A novel fluorescence-activated cell sorter-based screen for yeast endocytosis mutants identifies a yeast homologue of mammalian eps15. J Cell Biol 135: 1485–1500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesche S, Arnold M, Jansen RP (2003) The UCS domain protein She4p binds to myosin motor domains and is essential for class I and class V myosin function. Curr Biol 13: 715–724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]