Abstract

The most common human diseases are caused by pathogens. Several of these microorganisms have developed efficient ways in which to exploit host molecules, along with molecular pathways to ensure their survival, differentiation and replication in host cells. Although the contribution of the host cell to the development of many intracellular pathogens (particularly viruses and bacteria) has been unequivocally established, the study of host-cell requirements during the life cycle of protozoan parasites is still in its infancy. In this review, we aim to provide some insight into the manipulation of the host cell by parasites through discussing the hurdles that are faced by the latter during infection.

Keywords: host cell, infection, intracellular parasite

Introduction

After entering the host, intracellular pathogens need to recognize and exploit host-cell resources for their own benefit. Although this might seem obvious, the importance of a detailed understanding of the host-cell environment has only recently been generally acknowledged in the parasitology research field. The extent of the manipulation of host function by protozoan parasites can be seen, for example, in the uncontrolled proliferation of cells that are infected by Theileria (Dobbelaere & Kuenzi, 2004) and in the microarray analysis of a Toxoplasma-infected cell versus a non-infected cell, which highlighted important differences in several regulatory and biosynthetic activities (Blader et al, 2001). Therefore, the host-cell composition should no longer be considered as a 'black box'; rather, it should be seen as an ideal 'milieu' of molecular interactions in which the parasite strives towards success.

Reaching and entering the host cell

To infect a host, parasites must reach and recognize their specific target cell, as most infect only one or a few cell types in their host. In the phylum Apicomplexa, for example, Plasmodium invades hepatocytes and erythrocytes, whereas Theileria and Babesia spp. infect leukocytes. Toxoplasma spp. are an exception as they can survive in all types of nucleated cell, which implies that they recognize target molecules that are present on all cells and/or have developed many redundant mechanisms of infection.

On the transmission of Plasmodium by anopheline mosquitoes, sporozoites (the stage injected by a mosquito bite) rapidly reach the liver. Once there, they traverse several cells by breaching their plasma membranes before they finally invade their target cell through the formation of a vacuole (Mota et al, 2001). The migration of Plasmodium sporozoites through different cells before infection might be an example of a parasite seeking its required target cell. Migration has also been observed during the sporozoite and ookinete (the stage that traverses the mosquito gut after fertilization) stages of other apicomplexan parasites, such as Toxoplasma and Eimeria, although no migration has been seen during the merozoite and tachyzoite stages (the second and third invasive stages in the vertebrate host; Mota & Rodriguez, 2001). Therefore, the sporozoite and ookinete stages are the invasive forms that encounter, and must overcome, host cellular barriers to reach their replication sites. Recently, mutant Plasmodium parasites have been generated by disruption of the gene that encodes sporozoite microneme protein essential for cell traversal (spect). Although spect mutants are unable to migrate through cells and are not infectious in vivo, they are still able to infect hepatocytes in vitro (Ishino et al, 2004). The reason for this behaviour is under investigation.

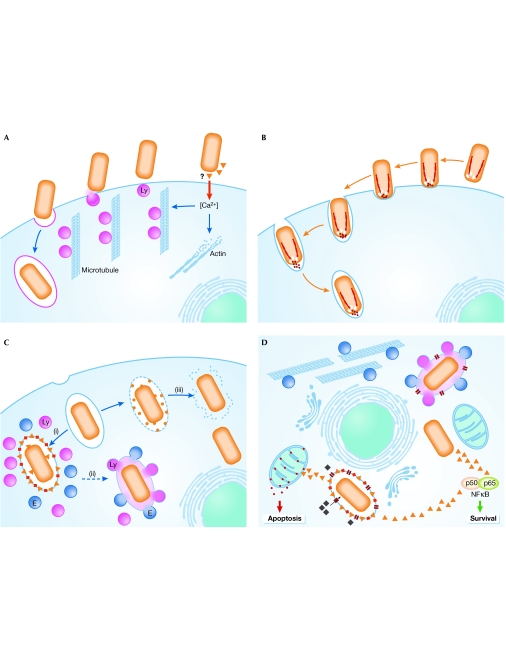

Once their target has been reached, different parasites have developed distinct strategies for entering the host cell. Professional phagocytic cells, such as neutrophils and macrophages, use phagocytosis to internalize and destroy not only foreign objects and apoptotic cells but also microbial pathogens. However, several intracellular pathogens are able to subvert this defence mechanism to gain access to the cells. The invasion of macrophages by Leishmania parasites, for example, is mediated by classical phagocytic receptors that are coupled to the vigorous actin-driven uptake machinery of these cells (Peters et al, 1995; Mosser & Brittingham, 1997).This process is mediated by serum opsonins that coat the parasite and requires the activation of Rho, Cdc42 and Rac1 in the macrophage. Leishmania parasites can also enter host cells by a non-opsonic pathway through a phagocyte-like actin-mediated process that does not involve Rac1 activation (Morehead et al, 2002). Conversely, the invasion of Trypanosoma cruzi is distinct from phagocytosis and is actually enhanced by inhibitors of actin polymerization (Kipnis et al, 1979; Schenkman et al, 1991; Tardieux et al, 1992; Rodriguez et al, 1999). This parasite uses a unique calcium-regulated microtubule-mediated pathway that directs the recruitment and fusion of lysosomes to the plasma membrane of host cells. The binding of T. cruzi to cells causes a transient increase in intracellular calcium, which induces actin disruption and the mobilization of lysosomes along microtubules towards the site of parasite attachment by associated kinesin motors. T. cruzi exploits this lysosomal-derived membrane to form a parasitophorous vacuole inside the host cell (Fig 1A; Schenkman et al, 1988; Rodriguez et al, 1996). Not surprisingly, other parasites have also developed strategies for cell invasion that are not dependent on particular components of the host cell. Some apicomplexans, for example, use an actin–myosin motor that is present in their own cytoskeleton to generate the motile force that is necessary to actively propel themselves into cells. This movement is known as gliding motility and is required for the active process of invasion that is mediated by the parasite. In the beststudied example—Toxoplasma invasion—the host cell has little or no active role in uptake (Fig 1B). No change is detected in host membrane ruffling, in the actin cytoskeleton or in the phosphorylation of host-cell proteins (Morisaki et al, 1995; Dobrowolski & Sibley, 1996). Host-cell actin polymerization is necessary, however, for the invasion of some apicomplexan parasites, such as Cryptosporidium parvum (Fayer & Hammond, 1967; Elliott & Clark, 2000; Elliott et al, 2001). Recent work indicates that C. parvum invades target epithelia by activating a Cdc42 GTPase signalling pathway that induces host-cell actin remodelling at the attachment site (Chen et al, 2004).

Figure 1.

Recognition, entrance and survival: a schematic representation of some of the strategies adopted by pathogens. (A) Induced recruitment of lysosomes to fuse with the host-cell plasma membrane to form the required vacuole for Trypanosoma cruzi. (B) A parasite, such as Toxoplasma, uses its own form of motility to propel itself into the host cell. (C) Once inside, intracellular pathogens follow different routes: they either reside inside the vacuole (i), which sometimes fuses with the exocytic/endocytic pathways (ii), or they reside in the host cytosol (iii). The same pathogen might use different strategies at different stages of development. (D) Independent of the route taken, all pathogens face similar problems, which include how to ensure that the cell is alive or dead at the appropriate times, how to acquire nutrients, how to avoid host-recognition systems and how to increase in size. Parasites and their proteins are shown in orange. E, endosomes; Ly, lysosomes.

Plasmodium sporozoites invade hepatocytes, whereas the merozoites invade erythrocytes. The effects of actin-depolymerizing agents on Plasmodium invasion are difficult to interpret as they affect not only the cytoskeleton of the host but also Plasmodium motility, which is required for invasion. The invasion of red blood cells by the merozoite begins with the initial attachment of the parasite and its subsequent reorientation such that its apical end is directed towards the erythrocyte. A moving junction is formed and the parasite pulls itself into the cell, where it stays inside a vacuole that is formed by the host plasma membrane (Chitnis & Blackman, 2000). In all of the apicomplexan parasite examples discussed here, parasite ligands for host-cell receptors are required for invasion. However, many of these adhesins are not displayed statically on the surface of the parasite; instead, they are stored in apically located secretory organelles that are known as micronemes. Constitutive secretion from these organelles is probably sufficient for gliding motility. Nevertheless, enhanced microneme secretion is probably required for invasion. This occurs when parasites contact host cells or migrate through cells, for example, in the cases of Toxoplasma tachyzoites and Plasmodium sporozoites, respectively (Carruthers & Sibley, 1997; Gantt et al, 2000; Mota et al, 2002). However, another exception in the Apicomplexa is the invasion of Theileria, the invasive stages of which are non-motile with no micronemes, and which require neither apical attachment to the host cell nor apical organelle secretion for invasion. In addition, invasion is neither dependent on the parasite actin cytoskeleton, nor does it involve substantial remodelling of the host cell surface. It has therefore been proposed that entry is accomplished by a physical process of zippering, which seems to be sufficient to cause internalization by a passive process (Webster et al, 1985; Shaw, 1999, 2003).

Vacuole or cytoplasm?

Parasites can survive and replicate in a vacuole or a phagolysosome inside the cell, or, less commonly, free in the host-cell cytosol (Fig 1C).

Inside a vacuole. The vacuolar compartment that is formed during parasite entry has an acidic environment, which is poor in nutrients, and undergoes progressive fusions with early endosomes, late endosomes and lysosomes. Parasites must therefore avoid, or modify, these compartments to escape destruction.

A general strategy that is used by pathogens to avoid the hostile lysosomal environment is to arrest the process of vacuole maturation at different stages. The maturation of vacuoles might be arrested not only by the persistence but also by the exclusion of host proteins that are known to regulate the endocytic/phagocytic pathway. For example, in infections by Toxoplasma gondii, which resist typical phagosome–lysosome fusion (Jones & Hirsch, 1972; Sibley et al, 1985), host-cell integral membrane proteins are largely excluded from the parasitophorous vacuole, whereas those of the parasite are incorporated (Sibley & Krahenbuhl, 1988; Beckers et al, 1994). This results in the formation of a membrane that is unique in its biochemical and biophysical properties, and leads to the creation of a non-fusogenic vacuole.

Conversely, some parasites survive in, and might even depend on, the harsh acidic environment of the phagolysosome. Although these pathogens must be resistant to acid hydrolases, the molecular mechanisms of this protection have yet to be clarified. Leishmania donovani is an interesting example, as it applies a dual strategy at distinct stages of its life cycle. L. donovani promastigotes, which are sensitive to acid, seem to inhibit phagosome–endosome fusion through unique lipophosphoglycan molecules on their cell surface (Miao et al, 1995; Descoteaux & Turco, 1999). After the amastigote transformation occurs, this inhibition is lifted and L. donovani multiplies in the now acidic intracellular compartment. Indeed, the amastigotes are metabolically most active when their environment is acidic (Joshi et al, 1993).

Free in the host-cell cytoplasm. Intracellular parasites can avoid the harsh environment that results from the fusion of their vacuole with degradative endocytic compartments by escaping rapidly from the nascent vacuole into the cytoplasm. Surprisingly, this strategy is used by only a few parasites, including T. cruzi and Theileria. Little is known about the molecular events that precede vacuole lysis. The exit of T. cruzi from the vacuole involves a parasite-secreted molecule, Tc-TOX, which has membrane pore-forming activity at acidic pHs (Andrews & Whitlow, 1989; Andrews et al, 1990; Ley et al, 1990). In the case of Theileria, escape into the cytoplasm coincides with the discharge of the parasite apical organelles, but their contents remain unknown (Shaw, 2003). Theileria also secretes proteins that contain AT-rich DNA-binding domains (AT-hook motifs) and that localize to the host-cell nucleus during infection (Swan et al, 1999, 2001, 2003). Recently, it has been shown that transfection of an uninfected, transformed bovine macrophage cell line with a plasmid that encodes the AT-hook parasite protein modulates cellular morphology and alters the expression pattern of a cytoskeletal polypeptide in a manner similar to that observed during the infection of leukocytes by the parasite (Shiels et al, 2004). Putative polypeptides that bear AT-hook motifs are present in the genomes of other parasites, such as T. gondii (http://ToxoDB.org; accession number TgTwinScan_4661) and several Plasmodium spp. (http://PlasmoDB.org; accession numbers PFC0325c, PB001090, Q7R873 and Q7RDC7). However, whether they are involved in host-cell modulation remains to be determined.

Problems of an intracellular lifestyle

Once inside the host cell, intracellular pathogens are faced with several obstacles and, in particular, must circumvent host defences, acquire nutrients and either kill or maintain the host cell according to their needs.

Host-cell defences. Parasites rarely reside in the cytosol, so it might be expected to contain many protective proteins or other antimicrobial agents. However, surprisingly, no cytosolic agents with direct antimicrobial activity have yet been identified. Most antimicrobial agents are either delivered into 'infected' vacuoles or are secreted into the extracellular space. The only known example of a cytosolic antimicrobial peptide is ubiquicidin, which is produced by the post-translational processing of the Fau protein, and part of which is very similar to ubiquitin. The peptide has strong antimicrobial activity against several bacteria, including Listeria monocytogenes (Hiemstra et al, 1999). However, it is not known whether this peptide is active against protozoan parasites.

Replication and growth. One of the problems faced by an intracellular pathogen is how to create sufficient space for replication. For this process to occur inside the vacuole, a considerable expansion of the compartment is required. Therefore, vacuoles must acquire large amounts of additional membrane lipids. As the cytoskeleton is involved in membrane transport events, modulation of its structure and/or function is an obvious strategy through which pathogens might alter vacuole formation and behaviour. A mesh of microtubules has been described around Toxoplasma vacuoles (Melo et al, 2001), but whether this provides a means for vacuole expansion is not yet known. No other strategy has been described for the enlargement of a parasitophorous vacuole by a protozoan parasite.

Nutrient acquisition. Acquisition of nutrients is crucial for pathogen survival. Although it provides protection from host defences, the membrane of non-fusogenic vacuoles restricts the access of the intravacuolar pathogens to the nutrient-rich cytoplasm. Therefore, pathogens must modify the vacuole membrane to allow them to scavenge the necessary nutrients and metabolites from the cytosol. During the blood stages of its life cycle, Plasmodium is inside a cell in which haemoglobin is extremely abundant, and this serves as the main source of amino acids for the parasite. As the parasite matures, it develops a special organelle, called the cytostome, for the uptake of host cytoplasm (Goldberg, 1993). In addition, Plasmodium (in the erythrocytic stages) and other apicomplexan parasites, such as Toxoplasma and Eimeria, have been shown to render the parasitophorous vacuole membrane freely permeable to small cytosolic molecules through the introduction of high-capacity channels or pores (Desai et al, 1993; Schwab et al, 1994; Desai & Rosenberg, 1997; Werner-Meier & Entzeroth, 1997). Conversely, results obtained for Leishmania imply that such pores or channels are not present in their vacuoles (Antoine et al, 1990). In the case of Leishmania amastigotes, the vacuole fuses with lysosomes and endosomes, which provides a relatively constant supply of nutrients. However, in promastigotes, the vacuole membrane does not fuse with vesicles of the endocytic or lysosomal compartments (Heinzen et al, 1996). It has been proposed that the association of vacuolar membranes with host-cell organelles, such as mitochondria and the endoplasmic reticulum, might have a role in nutrient acquisition in Toxoplasma (Jones & Hirsch, 1972; Sinai et al, 1997; Fig 1D).

Host-cell death and survival. Pathogens often kill cells and sometimes even the whole host organism, but at the same time they are heavily dependent on living cells and many of their functions. It is therefore not surprising that they have developed mechanisms for both the promotion of, and protection against, cell death. Although the apoptotic pathways that are regulated by virus- and bacteria-derived molecules have been extensively characterized at the molecular level, the details of these pathways in protozoan parasites are only just beginning to be revealed (reviewed in Heussler et al, 2001; Luder et al, 2001). The intracellular parasites T. parva, Toxoplasma and Leishmania can all inhibit apoptosis of the infected host cell (Moore & Matlashewski, 1994; Nash et al, 1998; Heussler et al, 1999). For both T. parva and Toxoplasma, activation of the transcription factor nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) seems to be crucial in protecting infected cells against apoptosis (Heussler et al, 2002; Molestina et al, 2003; Payne et al, 2003). In Theileria, NF-κB activation in infected transformed cells is known to be mediated by the recruitment of the multisubunit IκB kinase (IKK) into large activated foci on the surface of a specific parasite stage (Heussler et al, 2002). This indicates that the parasite seems to bypass the conventional pathways that link surface-receptor stimulation to IKK activation (Heussler et al, 2002). However, the precise mechanism by which the parasite recruits IKK signalosomes remains unknown. How Toxoplasma infection mediates NF-κB activation is also poorly understood and, in fact, is an area of some controversy (reviewed in Sinai et al, 2004). T. cruzi shows dual activity: it inhibits apoptotic pathways in the infected cell while simultaneously inducing apoptosis in T cells (Lopes et al, 1995; Clark & Kuhn, 1999; Nakajima-Shimada et al, 2000). It has been reported that Cryptosporidium infections induce apoptosis in in vitro-infected cell lines that were derived from primary hosts (Chen et al, 1999; McCole et al, 2000). More recently, and using a different in vitro cell system, it has been shown that Cryptosporidium induces non-apoptotic death in host cells as it leaves them (Elliott & Clark, 2003). The relevance of each of these observations to the outcome of the infection remains to be clarified. The erythrocytic stages of a malaria infection are unusual, as Plasmodium parasitizes one of the few types of cell that is thought to have limited ability to undergo apoptosis. However, apoptosis in erythrocytes has been characterized (Bratosin et al, 2001), and erythrocytes that are infected with mature stages of Plasmodium seem to contain phosphatidylserine on their surface (Eda & Sherman, 2002). This membrane phospholipid is present on the external surface of cells that are undergoing apoptosis or oxidative stress. It is not yet known whether, in this case, it is related to apoptosis. Conversely, in the hepatic stages of infection, hepatocytes infected with Plasmodium berghei and Plasmodium yoelii are protected against apoptosis, and this resistance seems to be triggered by both host and parasite molecules (P.L., S.S.A. and M.M.M., unpublished data).

Escape from the host cell

A final important step in the intracellular life of pathogens is their ability to exit the host cell after intracellular replication. The free pathogens can then infect new cells in the same host, or can be transmitted into a new host, depending on the life cycle of the pathogen. Parasites that have replicated inside a vacuole need to exit from both the vacuole and the cell, whereas those in the cytoplasm only need to escape from the cell itself. In Plasmodium merozoites, distinct proteases are involved in leaving the vacuole and the cell (Salmon et al, 2001; Wickham et al, 2003). Although the signals that trigger pathogens to leave cells are not yet known, in Toxoplasma, an increase in intraparasitic Ca2+ signalling occurs before exit of the parasite (Moudy et al, 2001; Arrizabalaga & Boothroyd, 2004).

Conclusions

Although the study of infectious diseases has spanned more than 100 years, we have only recently begun to appreciate the intricate interactions and the delicate balance that occur between pathogens and their host cells. Signalling pathways abound in cells and represent potential mechanisms by which a pathogen can cause profound effects in a host cell. Understanding these intricate interactions not only offers a new perspective on mammalian cell biology, but also allows the design of rational approaches to combat infectious diseases.

Clockwise from top left: Sónia S. Albuquerque, Maria M. Mota, Patricia Leirião & Cristina D. Rodrigues

Acknowledgments

We thank V. Heussler for discussion and comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by the Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (Portugal).

References

- Andrews NW, Whitlow MB (1989) Secretion by Trypanosoma cruzi of a hemolysin active at low pH. Mol Biochem Parasitol 33: 249–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews NW, Abrams CK, Slatin SL, Griffiths G (1990) A T. cruzisecreted protein immunologically related to the complement component C9: evidence for membrane pore-forming activity at low pH. Cell 61: 1277–1287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoine JC, Prina E, Jouanne C, Bongrand P (1990) Parasitophorous vacuoles of Leishmania amazonensis-infected macrophages maintain an acidic pH. Infect Immun 58: 779–787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrizabalaga G, Boothroyd JC (2004) Role of calcium during Toxoplasma gondii invasion and egress. Int J Parasitol 34: 361–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckers CJ, Dubremetz JF, Mercereau-Puijalon O, Joiner KA (1994) The Toxoplasma gondii rhoptry protein ROP2 is inserted into the parasitophorous vacuole membrane, surrounding the intracellular parasite, and is exposed to the host cell cytoplasm. J Cell Biol 127: 947–961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blader IJ, Manger ID, Boothroyd JC (2001) Microarray analysis reveals previously unknown changes in Toxoplasma gondii-infected human cells. J Biol Chem 276: 24223–24231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bratosin D et al. (2001) Programmed cell death in mature erythrocytes: a model for investigating death effector pathways operating in the absence of mitochondria. Cell Death Differ 8: 1143–1156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carruthers VB, Sibley LD (1997) Sequential protein secretion from three distinct organelles of Toxoplasma gondii accompanies invasion of human fibroblasts. Eur J Cell Biol 73: 114–123 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen XM, Gores GJ, Paya CV, LaRusso NF (1999) Cryptosporidium parvum induces apoptosis in biliary epithelia by a Fas/Fas ligand-dependent mechanism. Am J Physiol 277: G599–G608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen XM, Huang BQ, Splinter PL, Orth JD, Billadeau DD, McNiven MA, LaRusso NF (2004) Cdc42 and the actin-related protein/neural Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome protein network mediate cellular invasion by Cryptosporidium parvum. Infect Immun 72: 3011–3021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitnis CE, Blackman MJ (2000) Host cell invasion by malaria parasites. Parasitol Today 16: 411–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark RK, Kuhn RE (1999) Trypanosoma cruzi does not induce apoptosis in murine fibroblasts. Parasitology 118: 167–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai SA, Rosenberg RL (1997) Pore size of the malaria parasite's nutrient channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 2045–2049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai SA, Krogstad DJ, McCleskey EW (1993) A nutrient-permeable channel on the intraerythrocytic malaria parasite. Nature 362: 643–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Descoteaux A, Turco SJ (1999) Glycoconjugates in Leishmania infectivity. Biochim Biophys Acta 1455: 341–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbelaere DA, Kuenzi P (2004) The strategies of the Theileria parasite: a new twist in host–pathogen interactions. Curr Opin Immunol 16: 524–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrowolski JM, Sibley LD (1996) Toxoplasma invasion of mammalian cells is powered by the actin cytoskeleton of the parasite. Cell 84: 933–939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eda S, Sherman IW (2002) Cytoadherence of malaria-infected red blood cells involves exposure of phosphatidylserine. Cell Physiol Biochem 12: 373–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DA, Clark DP (2000) Cryptosporidium parvum induces host cell actin accumulation at the host–parasite interface. Infect Immun 68: 2315–2322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DA, Clark DP (2003) Host cell fate on Cryptosporidium parvum egress from MDCK cells. Infect Immun 71: 5422–5426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DA, Coleman DJ, Lane MA, May RC, Machesky LM, Clark DP (2001) Cryptosporidium parvum infection requires host cell actin polymerization. Infect Immun 69: 5940–5942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fayer R, Hammond DM (1967) Development of first-generation schizonts of Eimeria bovis in cultured bovine cells. J Protozool 14: 764–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gantt S, Persson C, Rose K, Birkett AJ, Abagyan R, Nussenzweig V (2000) Antibodies against thrombospondin-related anonymous protein do not inhibit Plasmodium sporozoite infectivity in vivo. Infect Immun 68: 3667–3673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg DE (1993) Hemoglobin degradation in Plasmodium-infected red blood cells. Semin Cell Biol 4: 355–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinzen RA, Scidmore MA, Rockey DD, Hackstadt T (1996) Differential interaction with endocytic and exocytic pathways distinguish parasitophorous vacuoles of Coxiella burnetii and Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect Immun 64: 796–809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heussler VT, Machado J Jr, Fernandez PC, Botteron C, Chen CG, Pearse MJ, Dobbelaere DA (1999) The intracellular parasite Theileria parva protects infected T cells from apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 7312–7317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heussler VT, Kuenzi P, Rottenberg S (2001) Inhibition of apoptosis by intracellular protozoan parasites. Int J Parasitol 31: 1166–1176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heussler VT et al. (2002) Hijacking of host cell IKK signalosomes by the transforming parasite Theileria. Science 298: 1033–1036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiemstra PS, van den Barselaar MT, Roest M, Nibbering PH, van Furth R (1999) Ubiquicidin, a novel murine microbicidal protein present in the cytosolic fraction of macrophages. J Leukoc Biol 66: 423–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishino T, Yano K, Chinzei Y, Yuda M (2004) Cell-passage activity is required for the malarial parasite to cross the liver sinusoidal cell layer. PLoS Biol 2: E4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones TC, Hirsch JG (1972) The interaction between Toxoplasma gondii and mammalian cells. II. The absence of lysosomal fusion with phagocytic vacuoles containing living parasites. J Exp Med 136: 1173–1194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi M, Dwyer DM, Nakhasi HL (1993) Cloning and characterization of differentially expressed genes from in vitro-grown 'amastigotes' of Leishmania donovani. Mol Biochem Parasitol 58: 345–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kipnis TL, Calich VL, da Silva WD (1979) Active entry of bloodstream forms of Trypanosoma cruzi into macrophages. Parasitology 78: 89–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley V, Robbins ES, Nussenzweig V, Andrews NW (1990) The exit of Trypanosoma cruzi from the phagosome is inhibited by raising the pH of acidic compartments. J Exp Med 171: 401–413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes MF, da Veiga VF, Santos AR, Fonseca ME, DosReis GA (1995) Activation-induced CD4+ T cell death by apoptosis in experimental Chagas' disease. J Immunol 154: 744–752 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luder CG, Gross U, Lopes MF (2001) Intracellular protozoan parasites and apoptosis: diverse strategies to modulate parasite–host interactions. Trends Parasitol 17: 480–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCole DF, Eckmann L, Laurent F, Kagnoff MF (2000) Intestinal epithelial cell apoptosis following Cryptosporidium parvum infection. Infect Immun 68: 1710–1713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo EJ, Carvalho TM, De Souza W (2001) Behaviour of microtubules in cells infected with Toxoplasma gondii. Biocell 25: 53–59 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao L, Stafford A, Nir S, Turco SJ, Flanagan TD, Epand RM (1995) Potent inhibition of viral fusion by the lipophosphoglycan of Leishmania donovani. Biochemistry 34: 4676–4683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molestina RE, Payne TM, Coppens I, Sinai AP (2003) Activation of NF-κB by Toxoplasma gondii correlates with increased expression of antiapoptotic genes and localization of phosphorylated IκB to the parasitophorous vacuole membrane. J Cell Sci 116: 4359–4371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore KJ, Matlashewski G (1994) Intracellular infection by Leishmania donovani inhibits macrophage apoptosis. J Immunol 152: 2930–2937 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morehead J, Coppens I, Andrews NW (2002) Opsonization modulates Rac-1 activation during cell entry by Leishmania amazonensis. Infect Immun 70: 4571–4580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morisaki JH, Heuser JE, Sibley LD (1995) Invasion of Toxoplasma gondii occurs by active penetration of the host cell. J Cell Sci 108: 2457–2464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosser DM, Brittingham A (1997) Leishmania, macrophages and complement: a tale of subversion and exploitation. Parasitology 115 (Suppl.): S9–S23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mota MM, Rodriguez A (2001) Migration through host cells by apicomplexan parasites. Microbes Infect 3: 1123–1128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mota MM, Pradel G, Vanderberg JP, Hafalla JC, Frevert U, Nussenzweig RS, Nussenzweig V, Rodriguez A (2001) Migration of Plasmodium sporozoites through cells before infection. Science 291: 141–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mota MM, Hafalla JC, Rodriguez A (2002) Migration through host cells activates Plasmodium sporozoites for infection. Nat Med 8: 1318–1322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moudy R, Manning TJ, Beckers CJ (2001) The loss of cytoplasmic potassium upon host cell breakdown triggers egress of Toxoplasma gondii. J Biol Chem 276: 41492–41501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima-Shimada J, Zou C, Takagi M, Umeda M, Nara T, Aoki T (2000) Inhibition of Fas-mediated apoptosis by Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Biochim Biophys Acta 1475: 175–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nash PB, Purner MB, Leon RP, Clarke P, Duke RC, Curiel TJ (1998) Toxoplasma gondii-infected cells are resistant to multiple inducers of apoptosis. J Immunol 160: 1824–1830 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne TM, Molestina RE, Sinai AP (2003) Inhibition of caspase activation and a requirement for NF-κB function in the Toxoplasma gondii-mediated blockade of host apoptosis. J Cell Sci 116: 4345–4358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters C, Aebischer T, Stierhof YD, Fuchs M, Overath P (1995) The role of macrophage receptors in adhesion and uptake of Leishmania mexicana amastigotes. J Cell Sci 108: 3715–3724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez A, Samoff E, Rioult MG, Chung A, Andrews NW (1996) Host cell invasion by trypanosomes requires lysosomes and microtubule/kinesin-mediated transport. J Cell Biol 134: 349–362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez A, Martinez I, Chung A, Berlot CH, Andrews NW (1999) cAMP regulates Ca2+-dependent exocytosis of lysosomes and lysosome-mediated cell invasion by trypanosomes. J Biol Chem 274: 16754–16759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmon BL, Oksman A, Goldberg DE (2001) Malaria parasite exit from the host erythrocyte: a twostep process requiring extraerythrocytic proteolysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 271–276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenkman S, Andrews NW, Nussenzweig V, Robbins ES (1988) Trypanosoma cruzi invade a mammalian epithelial cell in a polarized manner. Cell 55: 157–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenkman S, Diaz C, Nussenzweig V (1991) Attachment of Trypanosoma cruzi trypomastigotes to receptors at restricted cell surface domains. Exp Parasitol 72: 76–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab JC, Beckers CJ, Joiner KA (1994) The parasitophorous vacuole membrane surrounding intracellular Toxoplasma gondii functions as a molecular sieve. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 509–513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw MK (1999) Theileria parva: sporozoite entry into bovine lymphocytes is not dependent on the parasite cytoskeleton. Exp Parasitol 92: 24–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw MK (2003) Cell invasion by Theileria sporozoites. Trends Parasitol 19: 2–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiels BR, McKellar S, Katzer F, Lyons K, Kinnaird J, Ward C, Wastling JM, Swan D (2004) A Theileria annulata DNA binding protein localized to the host cell nucleus alters the phenotype of a bovine macrophage cell line. Eukaryot Cell 3: 495–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibley LD, Krahenbuhl JL (1988) Modification of host cell phagosomes by Toxoplasma gondii involves redistribution of surface proteins and secretion of a 32 kDa protein. Eur J Cell Biol 47: 81–87 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibley LD, Weidner E, Krahenbuhl JL (1985) Phagosome acidification blocked by intracellular Toxoplasma gondii. Nature 315: 416–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinai AP, Webster P, Joiner KA (1997) Association of host cell endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria with the Toxoplasma gondii parasitophorous vacuole membrane: a high affinity interaction. J Cell Sci 110: 2117–2128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinai AP, Payne TM, Carmen JC, Hardi L, Watson SJ, Molestina RE (2004) Mechanisms underlying the manipulation of host apoptotic pathways by Toxoplasma gondii. Int J Parasitol 34: 381–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan DG, Phillips K, Tait A, Shiels BR (1999) Evidence for localisation of a Theileria parasite AT hook DNA-binding protein to the nucleus of immortalised bovine host cells. Mol Biochem Parasitol 101: 117–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan DG, Stern R, McKellar S, Phillips K, Oura CA, Karagenc TI, Stadler L, Shiels BR (2001) Characterisation of a cluster of genes encoding Theileria annulata AT hook DNA-binding proteins and evidence for localisation to the host cell nucleus. J Cell Sci 114: 2747–2754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan DG, Stadler L, Okan E, Hoffs M, Katzer F, Kinnaird J, McKellar S, Shiels BR (2003) TashHN, a Theileria annulata encoded protein transported to the host nucleus displays an association with attenuation of parasite differentiation. Cell Microbiol 5: 947–956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tardieux I, Webster P, Ravesloot J, Boron W, Lunn JA, Heuser JE, Andrews NW (1992) Lysosome recruitment and fusion are early events required for trypanosome invasion of mammalian cells. Cell 71: 1117–1130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster P, Dobbelaere DA, Fawcett DW (1985) The entry of sporozoites of Theileria parva into bovine lymphocytes in vitro. Immunoelectron microscopic observations. Eur J Cell Biol 36: 157–162 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner-Meier R, Entzeroth R (1997) Diffusion of microinjected markers across the parasitophorous vacuole membrane in cells infected with Eimeria nieschulzi (Coccidia, Apicomplexa). Parasitol Res 83: 611–613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickham ME, Culvenor JG, Cowman AF (2003) Selective inhibition of a twostep egress of malaria parasites from the host erythrocyte. J Biol Chem 278: 37658–37663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]