Abstract

In human mitochondria, genes for tRNATyr and tRNACys overlap by a single nucleotide. From polycistronic precursors, a 3′-truncated upstream tRNATyr is released, missing the overlapping position. A subsequent editing reaction restores this position. Similar mitochondrial tRNA gene overlaps exist in all metazoans, but not in organisms such as yeast or Escherichia coli. Therefore, we asked whether tRNA overlaps are processed in these organisms. Corresponding constructs were introduced and transcripts tested for processing and editing in E. coli and yeast. E. coli produces only one functional tRNA from these precursors, indicating that tRNA overlaps are incompatible with its processing pathway. In contrast, yeast processes overlapping tRNAs similar to human mitochondria, releasing a 3′-truncated upstream tRNA. This tRNA is restored in an editing-like event, although yeast does not carry a corresponding endogenous editing substrate. These findings support the hypothesis of the evolution of editing by recruitment of a pre-existing and promiscuous editing enzyme.

Keywords: Escherichia coli, overlapping genes, RNA editing, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, tRNA processing

Introduction

In mitochondrial genomes of metazoans, overlapping tRNA genes have been described (Yokobori & Pääbo, 1995a, 1995b, 1997; Tomita et al, 1996; Reichert et al, 1998). Depending on the organism, the overlaps span a region of 1–6 nucleotides. Adjacent tRNAs are transcribed as part of a multicistronic precursor, and processing releases a complete downstream tRNA (carrying the overlapping nucleotides at its 5′ end) and a 3′-truncated upstream tRNA that misses the overlapping region. Subsequently, this tRNA is restored by an unknown nucleotide-incorporating activity (Yokobori & Pääbo, 1995a, 1995b; Reichert et al, 1998). In the human mitochondrial genome, the overlap between genes for tRNATyr and tRNACys consists of a single A residue, representing the last nucleotide of tRNATyr as well as the first nucleotide of tRNACys (Reichert et al, 1998).

Here, we investigated whether overlapping tRNA genes can exist in organisms that naturally do not contain such overlaps and whether maturation pathways of these organisms lead to functional transcripts. The results indicate that the processing machinery of Escherichia coli is not compatible with overlapping tRNAs, whereas in yeast, processing as well as tRNA editing could be found in the cytosol/nucleus. These results support the evolutionary scenario of RNA editing, describing the acquisition of a pre-existing activity as an editing enzyme.

Results And Discussion

E. coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (representing prokaryotes and eukaryotes) do not carry overlapping tRNA sequences in their genomes. This fact led to the question of whether these organisms are able to process overlapping tRNA precursors in a way similar to that of metazoans, which contain such gene overlaps in their mitochondrial DNA. Therefore, both organisms were tested for their ability to process artificially introduced overlapping tRNA precursors.

Processing of overlapping tRNA precursors in E. coli

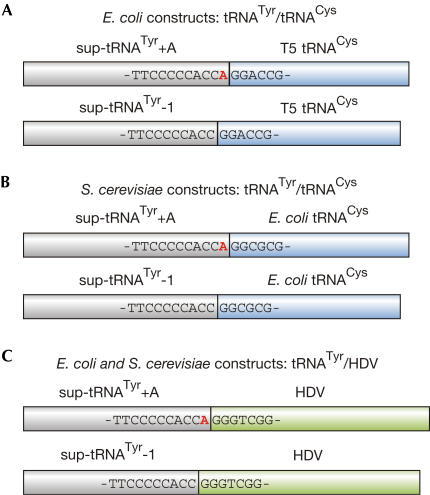

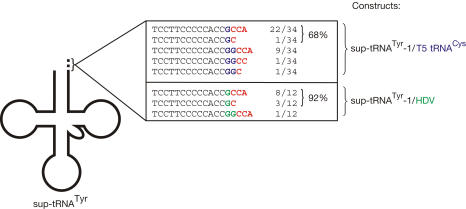

The following constructs were cloned into plasmid pBAD30 without 5′ extensions and introduced into E. coli CA244 (Fig 1A): in construct sup-tRNATyr–1/T5 tRNACys, two tRNA genes (E. coli suppressor tRNATyr, phage T5 tRNACys) were overlapping, as position A73 of the suppressor tRNA was not encoded, resembling the situation in human mitochondria. The second construct sup-tRNATyr+A/T5 tRNACys, where this position was encoded, served as a control. sup-tRNATyr and T5 tRNACys were chosen to distinguish introduced tRNAs from endogenous transcripts. All constructs were expressed by arabinose induction, and cells were grown on selective Luria-Bertani agar plates (30 μg/ml ampicillin). Subsequently, total RNA was prepared and the 3′ end of sup-tRNATyr—resulting from the overlapping construct—was determined by ligation of the RNA to an RNA/DNA oligonucleotide, followed by reverse transcription–PCR (RT–PCR), cloning and sequencing of individual clones (Fig 2). sup-tRNATyr released from the nonoverlapping construct carried an A residue at position 73 in 100% of the cases. In contrast, the corresponding tRNA from the overlapping construct showed in 68% (23 out of 34 clones) a G residue at position 73 and a complete (65%, 22 clones) or partial (3%, one clone) CCA end, whereas a further 32% (11 out of 34) showed two G residues plus complete or partial CCA sequence. As both G residues at the 3′ end of tRNATyr probably result from the 5′ part of tRNACys, a truncated sup-tRNATyr was obviously not released in E. coli.

Figure 1.

Expression constructs. (A,B) Constructs resembling overlapping tRNA genes: sup-tRNATyr is located upstream of tRNACys from phage T5, for expression in Escherichia coli (A), and from E. coli, for expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (B), respectively. In sup-tRNATyr+A/tRNACys, sup-tRNATyr ends with position 73 (A, red), whereas in sup-tRNATyr-1/tRNACys, this position is missing. (C) Constructs of sup-tRNATyr linked to HDV ribozyme. In tRNATyr+A/HDV, the tRNA carries position A73 (red). In tRNATyr-1/HDV, the tRNA sequence ends without this position.

Figure 2.

Sequence analysis of upstream sup-tRNATyr expressed in Escherichia coli. All molecules carry the diagnostic G residue at position 73 (blue, 5′ of the CCA terminus, red) that represents the first position of the downstream RNA. This indicates that in both constructs (sup-tRNATyr-1/T5 tRNACys, sup-tRNATyr-1/HDV), tRNATyr is not released as a 3′-truncated tRNA, but as a complete molecule.

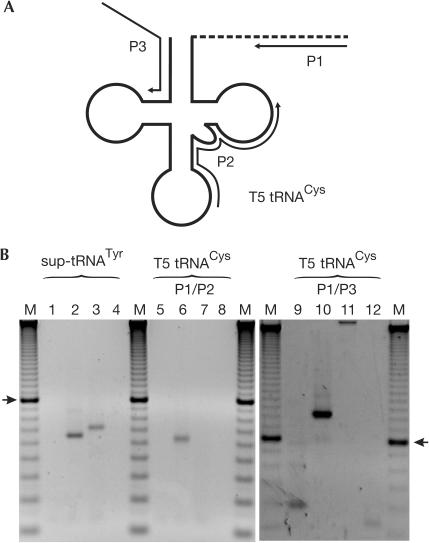

In addition, we tried to detect the T5 tRNACys located downstream. As standard procedures of tRNA circularization and RT–PCR for the simultaneous analysis of 5′ and 3′ ends of tRNA (Yokobori & Pääbo, 1995a) did not lead to any product, an alternative strategy was applied. An RNA/DNA-tagging oligonucleotide was ligated to the tRNA 3′ end and the ligation product amplified by RT–PCR using two different primer sets (P1/P2 and P1/P3; Fig 3A). Complementary DNA amplification of an in vitro-transcribed T5 tRNACys using these primers served as a positive control and resulted in products of 62 and 123 base pairs (bp), respectively (Fig 3B). In a further control PCR, sup-tRNATyr was amplified as an in vitro transcript as well as one present in the tRNA preparation, indicating that the RNA preparation contained amplifiable material. The in vitro transcript resulted in a product of the expected size (66 bp; Fig 3B), whereas sup-tRNATyr amplified from total RNA migrated at a higher position, as it carried position 73 plus the CCA end (70 bp; Fig 3B). In contrast, T5 tRNACys from E. coli total tRNA preparation could not be amplified with any of the primer pairs, indicating that this tRNA is not expressed as a stable transcript in transformed E. coli.

Figure 3.

Analysis of downstream T5 tRNACys in Escherichia coli. (A) Schematic representation. After fusing the 3′ end of the tRNA to the tag oligonucleotide (dashed line) and cDNA conversion (primer P1), several primer pairs were used for PCR amplification. (B) PCR products were separated on agarose gels. Left panel: lane 1, negative RT control without RNA; lane 2, sup-tRNATyr in vitro transcript lacking A73 and CCA terminus (66 bp; positive control); lane 3, sup-tRNATyr in E. coli RNA preparation (70 bp; positive control); lane 4, PCR blank control. Central and right panel: lanes 5,9, negative RT controls without RNA; lanes 6,10, in vitro-transcribed T5 tRNACys (positive controls: 62 and 123 bp); lanes 7,11, in vivo-expressed T5 tRNACys is not amplifiable; lanes 8,12, PCR blank controls. M, DNA size standard (10 bp ladder; 100 bp band is indicated by arrows).

In another strategy to express a 3′-truncated tRNA, constructs of sup-tRNATyr lying immediately upstream of the sequence of human hepatitis delta virus ribozyme (HDV) were designed and expressed in E. coli (Fig 1C; Wu & Huang, 1992; Schürer et al, 2002). In vitro, such precursor transcripts were processed by the cleavage reaction of the ribozyme, releasing a suppressor tRNATyr with (sup-tRNATyr+A/HDV) or without position 73 (sup-tRNATyr-1/HDV; not shown). Sequence analysis of 3′ ends showed that sup-tRNATyr released from the non-overlapping construct carried the encoded A73 plus a complete or partial CCA terminus (not shown), whereas products resulting from the overlapping construct showed a G residue at position 73. Most of the clones (92%) represented a sup-tRNATyr with G73 and complete (67%, 8 out of 12 clones) or partial (25%, 3 out of 12) CCA end, whereas 8% (1 out of 12) showed two G residues plus a CCA terminus (Fig 2). Therefore, as in the tRNATyr/tRNACys constructs, none of the clones showed a sup-tRNATyr in which position A73 was restored. The G residues at the tRNA 3′ end probably originate from the precursor transcript. As in the case of T5 tRNACys, no HDV RNA was detected in RT–PCR analysis, indicating that the ribozyme was rapidly degraded in E. coli.

The fact that bacteria and mitochondria have several features in common (genome organization, gene expression, etc.) indicates that mitochondria are of prokaryotic origin (Scheffler, 1999). Therefore, it is possible that overlapping tRNA genes of mitochondria are also a feature common to prokaryotes. However, our results demonstrate that E. coli is not able to make two functional tRNAs from overlapping precursors. An explanation for this discrepancy is that E. coli uses a set of endo- and exonucleases for tRNA 3′ end processing (Ray & Apirion, 1981b; Deutscher, 1984, 1990, 1995; Li & Deutscher, 1994, 1996): the initial step is a cleavage reaction in the 3′ trailer (here, represented by tRNACys) by RNase E or RNase III (Ray & Apirion, 1981a; Apirion & Miczak, 1993; Deutscher, 1995; Li & Deutscher, 2002). Subsequently, the mature 5′ end is produced by RNase P and the 3′ end further trimmed by exonucleases. Obviously, cleavage of downstream tRNACys by RNase P, leading to the release of a 3′-truncated upstream tRNATyr (as observed in vitro, not shown), cannot compete with this 3′-trailer trimming system. This situation can be explained by two scenarios. First, RNase P can be inhibited by long, unprocessed 3′ ends (Altman et al, 1987). The 3′ trailer of the downstream tRNACys resulting from the expression vector may represent such an extension that interferes with RNase P activity. Second, transcription and processing of tRNA precursors are not independent in E. coli, but are linked and occur in parallel. Therefore, a nascent overlapping precursor transcript seems to be processed by RNase E as soon as the first tRNA has left the polymerase, before synthesis of the second tRNA is completed. This would initiate processing of the upstream tRNA by exo- and endonucleolytic 3′ trimming, leading to degradation of downstream RNA. Alternatively, E. coli tRNase Z might cleave downstream of the overlapping nucleotide, at the 3′ end of tRNATyr, leading to the release of a 5′-truncated tRNACys that is then rapidly degraded by the RNA quality control system (Li et al, 2002). Such scenarios are strongly supported by the fact that neither T5 tRNACys nor HDV ribozyme could be detected (Fig 3). Further support comes from the observation that upstream sup-tRNATyr carries a G residue at position 73, which is probably derived from the RNA located downstream.

Processing overlapping tRNA precursors in S. cerevisiae

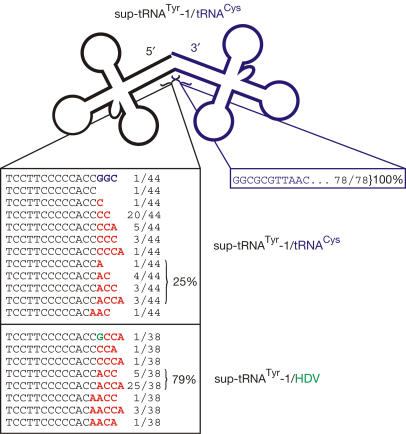

To analyse the processing of overlapping tRNA precursors in yeast, constructs consisting of E. coli sup-tRNATyr and tRNACys (sup-tRNATyr+A/tRNACys, sup-tRNATyr-1/tRNACys) were cloned into vector Y352_gal1 (Fig 1B). Constructs were expressed in S. cerevisiae BY 4741 growing in uracil-dropout medium containing galactose. Again, total RNA was isolated and tRNA 3′ ends were analysed using the above-mentioned oligo-tagging procedure followed by cloning and sequencing of individual clones (Fig 4). As in E. coli, only processed tRNA molecules could be detected, but not precursor molecules, indicating that in both systems, cleavage reactions were comparably efficient, even at increased levels of induction (not shown). In yeast, however, only 2.3% of the clones (1 out of 44) carried the encoded overlapping G residue at the 3′ end (plus two further nucleotides of the downstream tRNACys), whereas 97.7% carried non-encoded C or A residues at these positions, suggesting that a truncated upstream tRNATyr is released. Of the clones, 68% (30 out of 44) showed a C residue at the editing position plus a complete or partial CCA end, representing immediate CCA addition to the truncated 3′ end of the tRNA. Interestingly, 25% (11 out of 44) carried an A residue at the editing position 73. As this A is not encoded, it must have been added after processing of the precursor. To examine the 5′ end of downstream tRNACys, the same RNA preparation used for tRNATyr characterization was analysed by tRNA circularization and RT–PCR (Yokobori & Pääbo, 1995a). All clones (78 out of 78) showed a complete 5′ end of tRNACys, carrying the overlapping G residue at position 1 (Fig 4). This indicates that, in yeast, the precursor molecule is processed by an endonucleolytic cleavage 5′ of tRNACys, releasing a complete tRNACys and a 3′-terminally truncated tRNATyr.

Figure 4.

Sequence analysis of 3′ and 5′ ends of tRNAs introduced into Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Whereas tRNACys (blue) located downstream carried a complete 5′ terminus including the overlapping first position (diagnostic G residue), upstream sup-tRNATyr was released as a 3′-truncated molecule. An unidentified base-incorporating activity restored in 25%–79% of the cases the correct A residue at position 73 (bold character, red). This indicates that both tRNAs are released as stable transcripts and that yeast can catalyse editing-like reactions at the tRNA 3′ end.

As in E. coli, a second set of tRNA constructs (tRNATyr fused to HDV ribozyme in overlapping and non-overlapping arrangements; Fig 1C) was introduced into S. cerevisiae. Here, it turned out that 79% (30 out of 38) of tRNATyr clones had a restored A residue at the editing position 73 plus a complete (25 out of 38) or partial (5 out of 38) CCA end, whereas 5.4% carried a C residue at position 73. In all, 13% (4 out of 38) were obviously further truncated (positions 72 and 73) and were restored by the incorporation of two A residues with (partial) CCA addition. One single clone (2.6%) carried a G residue at position 73, which probably represents the overlapping first nucleotide of the HDV ribozyme.

This evidence indicates that yeast releases a truncated tRNATyr in the processing of overlapping precursors and restores at least part of this pool of truncated tRNA by an editing-like activity, adding an A residue at position 73. These results lead to the following conclusions: in contrast to E. coli, the yeast tRNA maturation system is able to process overlapping tRNA precursors in a way similar to the human mitochondrial pathway. An endonuclease recognizes the bicistronic precursor and releases a complete downstream RNA (whether HDV ribozyme is released by the same mechanism or by a self-cleaving reaction was not determined). Possible candidates for such a reaction are RNase P (5′-end processing) and tRNase Z (3′-end processing). Whereas the typical RNase P cleavage reaction at the 5′ end of tRNACys would generate a 3′-truncated tRNATyr, it is also possible that tRNase Z cleaves at a site shifted one position upstream relative to the standard site. A similar shift to the opposite direction was observed with pig tRNase Z, where the composition of the tRNA acceptor stem affects the site of trailer cleavage (Nashimoto et al, 1999). It is not clear yet which of these enzymes is responsible for the release of a truncated upstream tRNA in yeast.

A possible candidate for the A inserting activity is poly(A) polymerase that might add several A residues to the 3′ end of the tRNA. The surplus A residues might be removed by tRNase Z, leading to the release of a tRNA ending with A73 as a substrate for CCA addition. Indeed, some clones show a further truncated tRNA that was completed by the incorporation of two A residues at positions 72 and 73 followed by a complete or partial CCA end (Fig 4). But, although polyadenylated tRNAs were probable reaction intermediates in chicken mitochondria, where poly(A) polymerase is discussed as the editing activity (Yokobori & Pääbo, 1997), our analysis showed no such molecules. Another candidate is the CCA enzyme that generates the invariant CCA triplet at the 3′ end of tRNAs. However, the recombinant yeast enzyme was not able to restore the missing A residue at position 73, but simply added CCA to the truncated tRNA substrate (not shown). Therefore, both poly(A) polymerase and CCA enzyme can probably be ruled out in editing activities in yeast, indicating that a different, as yet unidentified, enzyme is involved.

The question arises as to whether the edited sup-tRNATyr is indeed functional and can be aminoacylated with tyrosine. As the anticodon is not a principal identity element in tRNATyr, the suppressor anticodon does not affect the identity of the tRNA (Andoh & Ozeki, 1968). However, the editing position A73 represents a true tyrosine determinant (Fechter et al, 2000). As the base-incorporating activity restores exactly the nature of this position, the tRNA receives an important identity element by the editing event, thereby defining its tyrosine identity. However, as this transcript represents a prokaryotic tRNA, it lacks a typical eukaryotic identity element (base pair C1–G72). Introducing that element into E. coli tRNATyr, Fechter et al (2000) showed that this tRNA is then readily accepted by the corresponding synthetase and is therefore a functional tRNA in yeast. Thus, an edited E. coli tRNATyr is a functional molecule and needs just a slight adaptation (which does not affect the editing position A73) to be tyrosylated efficiently in the yeast system.

Evolutionary considerations

These results document that production of two tRNAs from an overlapping precursor and formation of truncated tRNAs are incompatible with the prokaryotic tRNA processing pathway. The mitochondrion, as a former prokaryote, obviously replaced this tRNA 3′-end maturation using trimming exonucleases with the endonucleolytic system of the host cell, in which specific endonucleases cleave close to, or at, the tRNA 3′ end (Schürer et al, 2001). Because such an endonuclease activity is compatible with overlapping tRNA transcripts, the adaptation of the host maturation pathway was a prerequisite for the evolution of overlapping tRNA genes in mitochondrial genomes. Furthermore, the current results indicate that the former prokaryotic endosymbiont transferred not only essential primordial functions, but also most of its essential endogenous genes to its host, and relies now on the re-import of the corresponding proteins. It also adopted host functions, such as RNA maturation modes, that are now identified as typical mitochondrial RNA-processing reactions.

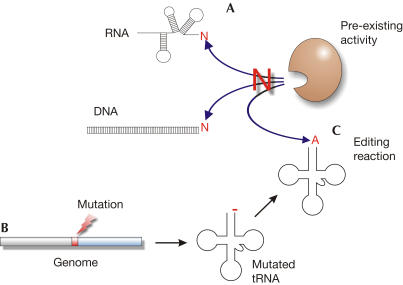

The fact that S. cerevisiae is able to edit a truncated tRNA is surprising, as this organism does not carry overlapping tRNA genes in its genome. Obviously, an editing activity is present in yeast without having a corresponding editing substrate. Although this happens in the nucleus/cytosol and not in the mitochondria of yeast, this situation exactly represents the general scenario that is discussed for the evolution of RNA editing (Fig 5; Covello & Gray, 1993; Cavaliersmith, 1997; Simpson et al, 2000). A prerequisite for the emergence of editing is a pre-existing enzymatic activity that catalyses a related reaction on some (RNA) substrates in the cell. This activity is promiscuous and accepts other (RNA) molecules as substrates. Then, a mutation—a deletion in the case of overlapping tRNA genes—occurs in a certain gene, leading to the expression of a nonfunctional transcript (here, 3′-truncated tRNA). Usually, such a mutation is deleterious, as the resulting product has lost its function. Here, however, the detrimental effect is neutralized by the promiscuous activity that restores the functional transcript. Consequently, the activity has now acquired an additional function as an editing enzyme. As this editing reaction removes the selective constraint from the mutated substrate gene, the editing event can be permanently established. Alternatively, it is also conceivable that yeast originally encoded editing substrates (overlapping tRNAs) and has lost them by mutation (base insertions). Nevertheless, even in that case, it is possible that a back mutation again creates overlapping tRNA molecules, (re)establishing an editing event in yeast.

Figure 5.

Model for the evolution of RNA editing. (A) A nucleotide-incorporating enzyme is present as a pre-existing editing activity in the cell. (B) A mutation in a gene leads to the transcription of a (t)RNA molecule that has to be edited to regain its function. (C) The pre-existing activity is promiscuous and accepts the inactive transcript as a new substrate and restores its function. Thereby, an RNA-editing event is established.

As such a situation obviously exists in yeast, it seems that this organism might be on its way to acquiring a nuclear tRNA editing event similar to that observed in metazoan mitochondria. Further experiments will help to identify the nature of this possible candidate for a future editing enzyme.

Methods

Preparation of DNA and RNA from E. coli and S. cerevisiae. Total DNA or RNA was prepared as described previously (Sambrook et al, 1989).

Construction of overlapping tRNA genes. See the supplementary information online.

Sequence analysis of tRNA 3′ termini. tRNA was ligated to a DNA oligonucleotide (Purimex, Göttingen, Germany) carrying an RNA nucleotide at the phosphorylated 5′ end (tag oligo pU-ATACTCATGGTCATAGCTGTT; Betat et al, 2004). cDNA synthesis was carried out by annealing primer P1 (AACAGCTATGACCATG) to the tag oligonucleotide and using MMLV Reverse Transcriptase (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. cDNA was amplified in a standard PCR reaction containing 2% dimethyl sulphoxide using primer P1 and a primer specific for E. coli sup-tRNATyr, E. coli tRNACys or T5 tRNACys. PCR products were cloned using a TA cloning kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). DNA sequencing was performed on an ABI Prism 3700 automated sequencer (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Freiburg, Germany).

Circularization of tRNA. The total RNA (4 μg) prepared was circularized as described previously (Yokobori & Pääbo, 1995a). cDNA was synthesized and amplified as described above, using primers specific for E. coli sup-tRNATyr and E. coli tRNACys.

Supplementary information is available at EMBO reports online (http://www.nature.com/embor/journal/vaop/ncurrent/extref/7400381s1.pdf).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

We thank K. Köhler for expert technical assistance, H. Dihazi for plasmid Y325_gal1, U. Krause-Buchholz for S. cerevisiae strain BY 4741 and E. Lizano, C. Rammelt and R.K. Hartmann for helpful discussions. This work was supported by the Max-Planck-Society and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Mo 634/2).

References

- Altman S, Baer M, Gold H, Guerrier-Takada C, Lawrence N, Lumelsky N, Vioque A (1987) Cleavage of RNA by RNase P. In Molecular Biology of RNA, Inouye M, Dudock BS (eds) pp 3–15. Orlando, FL, USA: Academic [Google Scholar]

- Andoh T, Ozeki H (1968) Suppressor gene Su3+ of E. coli, a structural gene for tyrosine tRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 59: 792–799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apirion D, Miczak A (1993) RNA processing in prokaryotic cells. Bioessays 15: 113–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betat H, Rammelt C, Martin G, Mörl M (2004) Exchange of regions between bacterial poly(A) polymerase and CCA adding enzyme generates altered specificities. Mol Cell 15: 389–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavaliersmith T (1997) Cell and genome coevolution: facultative anaerobiosis, glycosomes and kinetoplastan RNA editing. Trends Genet 13: 6–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covello PS, Gray MW (1993) On the evolution of RNA editing. Trends Genet 9: 265–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutscher M (1990) Ribonucleases, tRNA nucleotidyltransferase, and the 3′ processing of tRNA. Progress Nucleic Acids Res Mol Biol 39: 209–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutscher MP (1984) Processing of tRNA in prokaryotes and eukaryotes. CRC Crit Rev Biochem 17: 45–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutscher MP (1995) tRNA processing nucleases. In tRNA: Structure, Biosynthesis and Function, Söll D, RajBhandary UL (eds) pp 51–65. Washington, DC, USA: ASM [Google Scholar]

- Fechter P, Rudinger-Thirion J, Théobald-Dietrich A, Giegé R (2000) Identity of tRNA for yeast tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase: tyrosylation is more sensitive to identity nucleotides than to structural features. Biochemistry 39: 1725–1733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Deutscher MP (1994) The role of individual exoribonucleases in processing at the 3′ end of Escherichia coli tRNA precursors. J Biol Chem 269: 6064–6071 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Deutscher M (1996) Maturation pathway for E. coli tRNA precursors: a random multienzyme process in vivo. Cell 86: 503–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Deutscher MP (2002) RNase E plays an essential role in the maturation of Escherichia coli tRNA precursors. RNA 8: 97–109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Reimers S, Pandit S, Deutscher MP (2002) RNA quality control: degradation of defective transfer RNA. EMBO J 21: 1132–1138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nashimoto M, Tamura M, Kaspar RL (1999) Selection of cleavage site by mammalian tRNA 3′ processing endoribonuclease. J Mol Biol 287: 727–740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray BK, Apirion D (1981a) RNAase P is dependent on RNAase E action in processing monomeric RNA precursors that accumulate in an RNAase E− mutant of Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol 149: 599–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray BK, Apirion D (1981b) Transfer RNA precursors are accumulated in Escherichia coli in the absence of RNase E. Eur J Biochem 114: 517–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichert A, Rothbauer U, Mörl M (1998) Processing and editing of overlapping tRNAs in human mitochondria. J Biol Chem 273: 31977–31984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbour, NY, USA: Cold Spring Harbour Laboratory Press [Google Scholar]

- Scheffler IE (1999) Mitochondria. New York, USA: Wiley–Liss [Google Scholar]

- Schürer H, Schiffer S, Marchfelder A, Mörl M (2001) This is the end: processing, editing and repair at the tRNA 3′-terminus. Biol Chem 382: 1147–1156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schürer H, Lang K, Schuster J, Mörl M (2002) A universal method to produce in vitro transcripts with homogeneous 3′ ends. Nucleic Acids Res 30: e56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson L, Thiemann OH, Savill NJ, Alfonzo JD, Maslov DA (2000) Evolution of RNA editing in trypanosome mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 6986–6993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomita K, Ueda T, Watanabe K (1996) RNA editing in the acceptor stem of squid mitochondrial tRNA(Tyr). Nucleic Acids Res 24: 4987–4991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu HN, Huang ZS (1992) Mutagenesis analysis of the self-cleavage domain of hepatitis delta virus antigenomic RNA. Nucleic Acids Res 20: 5937–5941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokobori S, Pääbo S (1995a) Transfer RNA editing in land snail mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92: 10432–10435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokobori S, Pääbo S (1995b) tRNA editing in metazoans. Nature 377: 490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokobori S, Pääbo S (1997) Polyadenylation creates the discriminator nucleotide of chicken mitochondrial tRNATyr. J Mol Biol 265: 95–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information