Abstract

Dimerization of the transmembrane domain of glycophorin A is mediated by a seven residue motif LIxxGVxxGVxxT through a combination of van der Waals and hydrogen bonding interactions. One of the unusual features of the motif is the large number of β-branched amino acids that may limit the entropic cost of dimerization by restricting side-chain motion in the monomeric transmembrane helix. Deuterium NMR spectroscopy is used to characterize the dynamics of fully deuterated Val80 and Val84, two essential amino acids of the dimerization motif. Deuterium spectra of the glycophorin A transmembrane dimer were obtained using synthetic peptides corresponding to the transmembrane sequence containing either perdeuterated Val80 or Val84. These data were compared with spectra of monomeric glycophorin A peptides deuterated at Val84. In all cases, the deuterium line shapes are characterized by fast methyl group rotation with virtually no motion about the Cα-Cβ bond. This is consistent with restriction of the side chain in both the monomer and dimer due to intrahelical packing interactions involving the β-methyl groups, and indicates that there is no energy cost associated with dimerization due to loss of conformational entropy. In contrast, deuterium NMR spectra of Met81 and Val82, in the lipid interface, reflected greater motional averaging and fast exchange between different side-chain conformers.

INTRODUCTION

Most membrane proteins span lipid bilayers with long stretches of hydrophobic amino acids that independently fold into transmembrane helices. The specific association of these helices is a key element in the folding of polytopic membrane proteins (Popot and Engelman, 2000). Over the past few years, the analyses of membrane protein sequences along with high resolution x-ray and NMR structures of helical membrane proteins have provided clues as to how transmembrane helices associate in a sequence specific manner. One conclusion from these studies is that the mechanism of helix association in membrane proteins is clearly different than in soluble proteins where the hydrophobic effect is a dominant driving force for protein folding. In membrane proteins, the hydrophobic effect is lost once the helices are inserted into the membrane bilayer, and a combination of van der Waals, hydrogen bonding, and electrostatic interactions are likely to be the major determinants of specific helix association. We have used the transmembrane domain of glycophorin A as a simple model system for establishing how different amino acids can drive specific helix association and can contribute to the stability of transmembrane helix dimers (Smith et al., 2001; Smith et al., 2002).

The energetic contributions to the dimerization of the glycophorin A helix have been studied by analytical ultracentrifugation (Fleming et al., 1997; Fleming and Engelman, 2001) and Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) (Fisher et al., 1999). These experiments provide estimates of the monomer-dimer equilibrium and corresponding free energy of association. FRET between monomers of the glycophorin A dimer solubilized in the zwitterionic detergent dodecyl-N,N,-dimethyl ammonium butyrate yields a dissociation constant of 80 nM (Fisher et al., 1999), whereas analytical ultracentrifugation of the dimer in the detergent pentaoxyethylene octyl ether yields a dissociation constant of 240 nM (Fleming et al., 1997). These dissociation constants correspond to standard state association free energy changes of −7.0 kcal/mol and −4.5 kcal/mol, respectively (Fleming, 2002).

The tight association of transmembrane helices results in part from favorable enthalpic interactions between helices. The enthalpic contributions to dimerization are clearly illustrated by the fact that specific conservative mutations disrupt stable dimers (Fleming and Engelman, 2001) and by the observation of specific interhelical contacts in the structure of the dimer in both detergent micelles (MacKenzie et al., 1997) and membrane bilayers (Smith and Bormann, 1995; Smith et al., 2001). For instance, the conservative Gly79Ala and Gly83Ala replacements (i.e., insertion of a single methyl group) result in complete dissociation of the dimer. Direct interhelical packing of these glycines allows close approach of the helix backbones in the dimer, which facilitates stabilizing van der Waals interactions and interhelical -C O⋯H-O- and CαH⋯O

O⋯H-O- and CαH⋯O C- hydrogen bonds (Javadpour et al., 1999; Senes et al., 2001; Smith et al., 2002).

C- hydrogen bonds (Javadpour et al., 1999; Senes et al., 2001; Smith et al., 2002).

It has been more difficult to estimate whether the entropic contribution to helix association is favorable or unfavorable. In terms of helix interactions, one must consider the changes in entropy resulting from the loss of helix-lipid contacts and the gain of helix-helix contacts. A key question is whether lipids become ordered when associated with the surfaces of membrane proteins. Both deuterium NMR (Bloom and Smith, 1985) and EPR (Marsh and Horvath, 1998) indicate that the ordering of lipid chains at the protein-lipid interface is very similar to the ordering in bulk lipid, suggesting that there is no entropic contribution to helix association from helix-lipid interactions. However, molecular dynamics simulations (Lague et al., 2001) suggest that lipid chains transiently become ordered against transmembrane helix surfaces indicating that helix-helix association is favored in terms of a net increase in entropy of the lipid chains upon dimerization.

There has been less attention paid to the entropic contribution to dimerization associated with the formation of helix-helix contacts. The loss of side-chain entropy in the dimer interface has been thought to be a factor in destabilizing dimerization. However, the observation of a large number of β-branched amino acids in the dimer interface of glycophorin A has suggested that these residues restrict side-chain motion and consequently minimize entropy loss upon dimerization (MacKenzie et al., 1997; Smith et al., 2001).

Deuterium NMR spectroscopy is well-suited for probing dynamic processes in membrane proteins (Siminovitch, 1998; Ying et al., 2000; Sharpe et al., 2002). Deuterium NMR has previously been used to study the dynamics of valine in the β-helix of gramicidin (Lee and Cross, 1994) and in the α-helices of bacteriorhodopsin (Keniry et al., 1984a). In gramicidin A, Cross and co-workers found that the motion of the valine side chains was sequence specific (Lee et al., 1995). Val1 and Val7 (L-amino acids) produced axially symmetric line shapes characteristic of only fast methyl rotation, whereas the line shapes of Val6 and Val8 (D-amino acids) showed clear evidence of additional motions on the intermediate timescale (∼105 s−1). Lee and Cross (1994) were able to simulate the Val6 and Val8 deuterium spectra by fast methyl rotation superimposed on rotation about the Cα-Cβ bond. They used a three-site jump model with an unequal occupancy ratio of 75:15:10 for the three χ1 rotamers and an average occupancy time of 1.5 μs. These studies showed that it is possible for local packing interactions to have a dramatic effect on the side-chain dynamics of valine.

Oldfield and co-workers obtained deuterium spectra of valine in bacteriorhodopsin, an integral membrane protein having seven transmembrane helices. The spectra exhibited an ∼40 kHz quadrupole splitting characteristic of both fast methyl rotation and significant intensity between +20 kHz and −20 kHz characteristic of motion about the Cα-Cβ bond (Kinsey et al., 1981; Keniry et al., 1984b). Because the 21 valines in bacteriorhodopsin are predominantly located in the transmembrane helices, the data suggest that even for L-amino acids in α-helices the local environment may influence the side-chain dynamics. The drawback of these studies is that the authors were not able to observe the dynamics of single valines.

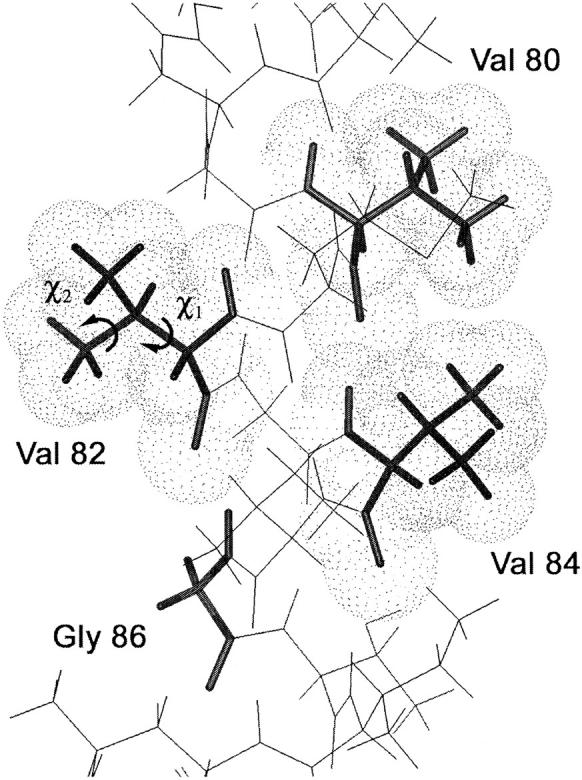

To probe the motion of valine in glycophorin A, deuterium NMR measurements were made on peptides corresponding to the transmembrane domain of glycophorin A that were synthesized with deuterium labels at single amino acids. The first two peptides contained fully deuterated Val80 or fully deuterated Val84. These two amino acids are part of the seven-residue glycophorin A dimerization motif (Fig. 1). Deuterium NMR measurements were made on peptides reconstituted into multilamellar membrane dispersions of dimyristoylphosphocholine (DMPC) at 20°C and 60°C. The deuterium spectra of Val80 and Val84 were compared with spectra of monomeric glycophorin A specifically deuterated at Val84. The monomeric peptide was produced by substitution of Leu75 with valine which prevents dimerization (Lemmon et al., 1992). The spectra were also compared with deuterium spectra of Met81 and Val82, both of which are oriented toward the surrounding lipid in the dimer (Smith et al., 2001). In the native glycophorin A sequence, residue 82 is an alanine. However, saturation mutagenesis has shown that Ala82 can be replaced by valine without disruption of dimerization (Lemmon et al., 1992). Moreover, the amino acid at position 82 is positioned one helical turn above Gly86 in the sequence (Fig. 1). This location eliminates the potential for side chain–side chain contacts that may hinder the motion of Val82. This is in contrast to Val80 and Val84 that are part of a tightly packed ridge of β-branched amino acids running along one face of the glycophorin A transmembrane helix (Smith et al., 2001). Together these samples allow us to study the influence of dimerization and local environment on the motion of valine in the glycophorin A dimer interface.

FIGURE 1.

Model of the glycophorin A monomer in the region of Val80 – Gly86. The view is along the dimer interface and highlights Val80, Val82, Val84, and Gly86. The β-branched valines are in the trans conformation. The χ1 and χ2 torsion angles of Val82 are indicated.

The deuterium NMR measurements on single sites in a well-defined transmembrane α-helix also address the more general question concerning the motion of valine in α-helices. High resolution crystal structures of soluble proteins show that valine has a single preferred rotational conformer (rotamer) in α-helices (Lovell et al., 2000). Specifically, Richardson and co-workers found that the distribution of valine in the trans, gauche+, and gauche− rotamers is ∼90:7:3, respectively. However, the crystallographic data yield only the time-averaged conformation of the amino acid side chain and cannot assess the rates of interconversion between rotamers. In other words, the distribution of conformers alone does not indicate whether there is a kinetic barrier for conversion between states having comparable energies or whether the predominant trans conformer simply has a much lower energy than the gauche+ and gauche− conformers. This information is accessible through deuterium line shapes that are sensitive to the motional rates and rotamer populations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Deuterated (D8) valine and deuterium-free water were purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories (Andover, MA). Other amino acids and octyl-β-glucoside were obtained from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO). DMPC was obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL) as a lyophilized powder and used without further purification.

Peptide synthesis and reconstitution into DMPC bilayers

Peptides (29 residues in length) corresponding to the transmembrane domain of human glycophorin A were synthesized using solid-phase methods at the W. M. Keck Peptide Synthesis Facility at Yale University. The sequence is largely hydrophobic with Glu and Arg defining the N-terminal and C-terminal boundaries of the transmembrane domain, respectively.

|

|

The purification and reconstitution of the peptides have recently been described in detail (Smith et al., 2002). Briefly, the crude peptide (5–15 mg) was purified by reverse-phase HPLC on a C4 column using gradient elution. The gradient starts with a largely aqueous solution of 70% distilled water, 12% acetonitrile, and 18% 2-propanol, and is changed to a more hydrophobic composition of 40% acetonitrile and 60% 2-propanol that elutes the peptides. The elution was monitored by the optical absorbance at 280 nm. The solutions corresponding to the peaks were collected into several fractions that were then lyophilized and checked by mass spectrometry for purity.

Purified glycophorin A peptides were reconstituted by detergent dialysis by first dissolving DMPC, lyophilized peptide, and detergent (octyl-β-glucoside) in trifluoroethanol. This mixture was incubated at 37°C for over 2 h, and the trifluoroethanol was removed by evaporation using a stream of argon gas and then placing the sample under vacuum. The dry mixture was rehydrated with phosphate buffer (10 mM phosphate and 50 mM NaCl, pH 7), such that the final concentration of octyl-β-glucoside was 5% (w/v). The rehydrated sample was then stirred slowly for at least 6 h, and the octyl-β-glucoside was removed by dialysis using Spectra-Por dialysis tubing (3500 MW cutoff) for 24 h against phosphate buffer at 30°C. The resulting membrane vesicles were sonicated and loaded onto a 10–40% (w/v) sucrose gradient and ultracentrifuged at 150,000 × g for 8–12 h at 15°C. The reconstituted membranes formed two discrete bands in the sucrose gradient. For the deuterium NMR measurements, we used the upper band, which we have previously shown corresponds to the glycophorin A peptide oriented in a transmembrane fashion (Smith et al., 2002). The sucrose was removed by dialysis against phosphate buffer for 24 h with repeated buffer changes. The bilayers were then pelleted and resuspended in deuterium-depleted water and incubated at 30°C for more than 24 h. The reconstituted membranes were then pelleted to form multilamellar dispersions and loaded into NMR rotors. Excess water was removed by spinning the sample in a table top rotor spinning unit. The water remaining in all samples was 49% ± 5% by weight.

The initial protein:lipid ratio for the reconstitutions was 1:40. Analysis of the upper band in the sucrose gradients by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy indicates that the final protein:lipid ratio is in the range of 1:60. The lower band in the sucrose gradients is enriched in peptide, possibly due to aggregation. Importantly, we have shown that the glycophorin A transmembrane peptides form dimers using this reconstitution protocol (Smith et al., 2002). The total amount of deuterated peptide in the sample (∼2 μmol) is sufficient for deuterium magic angle spinning (MAS) studies because the signal intensity is focused in the narrow spinning side bands. However, static NMR measurements of comparable sensitivity are difficult; the advantages of MAS are lost and coherent ringing in the system from the sample coil to the preamplifier results in distortions in the spectra, which of course cannot be averaged, even using echo sequences.

Solid-state NMR spectroscopy

Deuterium NMR spectra were obtained at a 2H frequency of 92.12 MHz on a Bruker Avance NMR spectrometer using magic angle spinning. MAS spectra yield much higher sensitivity compared to conventional static spectra in these membrane-reconstituted samples where the concentration of deuterated peptide is low. A MAS frequency of 3 kHz was used to increase the number of spinning side bands. Single pulse excitation was employed using a 3.7-μs 90° pulse, followed by a 4.5-μs delay before data acquisition. The repetition delay was 1 s. A total of 100,000–200,000 transients were averaged for each spectrum and processed using a 200-Hz exponential line broadening function. Spectra were obtained at 20°C and 60°C. The 60°C temperature is well above the 24°C phase transition temperature of pure DMPC. The addition of peptide at a 1:40 molar ratio to lipid should lower the DMPC phase transition temperature by only 1–2°C (Morein et al., 2002; Liu et al., 2002).

NMR simulations

MAS deuterium spectra were simulated using the program SIMPSON version 1.1.0 (Bak et al., 2000) with a spin rate of 3 kHz. For fast methyl group rotation, we used an asymmetry parameter (η) of 0 and an effective quadrupole coupling constant of 49 kHz. For simulating fast methyl group rotation superimposed upon fast rotation about the Cα-Cβ bond, we used an asymmetry parameter η of 0.1 and an effective quadrupole coupling constant of 47 kHz (see Results). The static deuterium line shapes of the methyl deuterons were simulated with the program MXET1 (Greenfield et al., 1987) on a Sun Blade 100 workstation with a 64-bit 500-MHz UltraSPARC-IIe processor. Fast methyl group rotation was assumed by starting with an effective quadrupole coupling constant of 49 kHz. The χ1 rotation was simulated by a three-site hop with the hop angle set at 120°. The jump rate was varied from 5 × 109 s−1 to 50 s−1. The starting asymmetry parameter η was 0.05, the 90° pulse length was 3.5 μs, and the echo delay was 50 μs. Typical three-site simulations required two minutes of processor time. In the discussion below of the static line shape simulations using MXET1, we indicate the input jump rate. This would be the jump rate if the populations between the different sites are equal.

Occluded surface (OS) calculations

The coordinates of the transmembrane dimer of glycophorin A were obtained from the model we developed based on solid-state NMR distance constraints (Smith et al., 2001). Packing of the Val80, Val82, and Val84 side chains were determined using the method of occluded surfaces (Pattabiraman et al., 1995; DeDecker et al., 1996). The OS method provides a direct measure of molecular packing, and yields a packing value for each valine residue.

RESULTS

Deuterium NMR spectroscopy

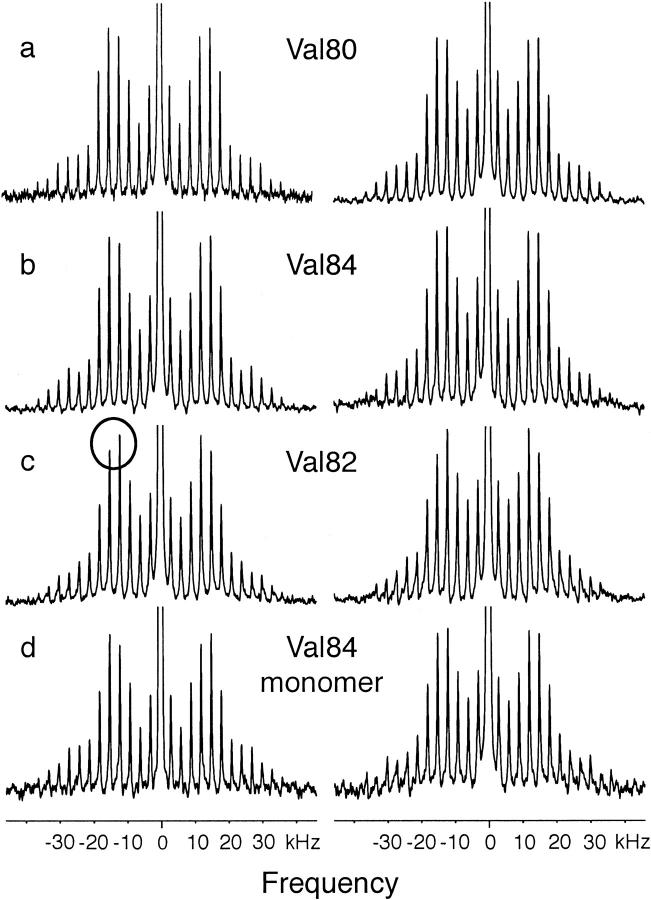

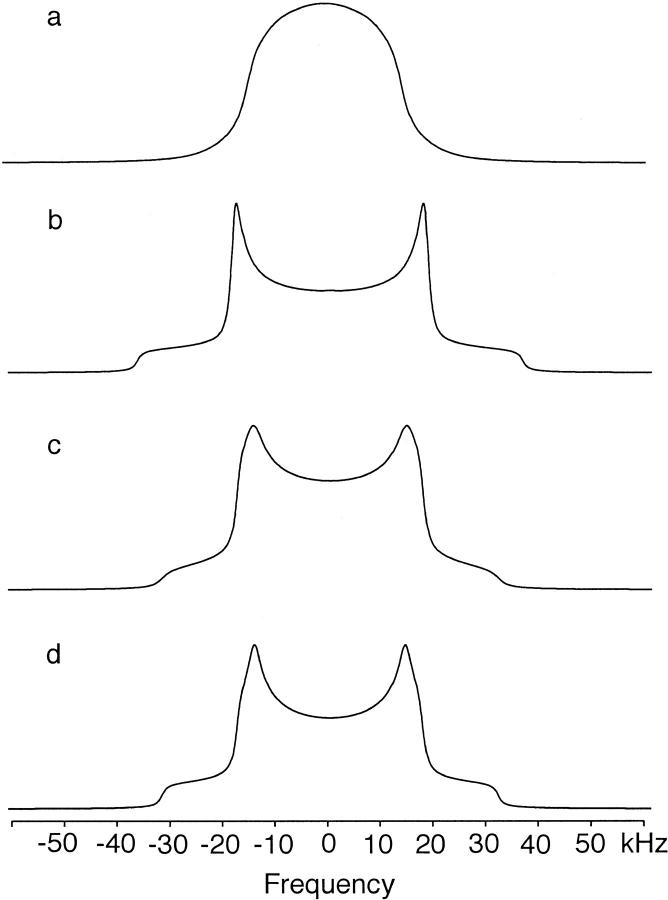

Fig. 2 presents MAS spectra of the 29-residue glycophorin A transmembrane peptides containing fully deuterated valine at positions 80, 82, and 84, where the numbering is retained from the full protein sequence. MAS spectra were obtained rather than conventional static spectra to increase the spectral sensitivity and to better characterize the contribution of motion about the χ1 torsion angle. A MAS frequency of 3 kHz was chosen to increase the number of spinning side bands. Deuterium spectra were collected at 20°C (left) and at 60°C (right). The spectra have been symmetrized and the large HOD peak in the center of the spectrum has been truncated. The HOD peak is extremely narrow in the MAS spectra. Its contribution to the deuterium line shape, which is easily distinguished from the contribution of the deuterated valine side chain, can be eliminated from the analysis.

FIGURE 2.

Deuterium NMR spectra of perdeuterated (D8) Val80, Val82, and Val84 glycophorin A at 20°C (left) and 60°C (right). Glycophorin A peptides were reconstituted into DMPC multilayers at a 1:40 peptide:lipid molar ratio and hydrated with ∼50 wt% deuterium-depleted water. The MAS spectra were obtained using single pulse excitation at a deuterium frequency of 92.12 MHz with a spinning speed of 3000 Hz ± 3 Hz. The 90° 2H pulse length was 3.7 μs. Each spectrum represents the average of 100,000–200,000 transients. An exponential line broadening of 200 Hz was applied. The intensity differences that occur in the most intense spinning side bands in Val82, circled in (c), are significant and reveal the presence of motion about the Cα-Cβ bond.

Although there are eight deuterons in each labeled valine, the observed intensity in the deuterium spectrum results from the six methyl CγD3 deuterons. Methyl groups characteristically undergo fast three-site hops. Reducing methyl group rotation requires lowering the temperature to <−120°C (Beshah et al., 1987). Consequently, all of the spectra shown in Fig. 2 reflect narrowing by fast methyl rotation. The contribution of the single Cα and Cβ deuterons is negligible because the quadrupole coupling constants for these rigid sites are expected to be >120 kHz.

The 30-kHz splitting between the two most intense spinning side bands at 20°C for Val80 and Val84 (Fig. 2, a and b) is consistent with only methyl rotation (see Simulations below). There is no evidence of motion about the Cα-Cβ bond or axial rotation of the transmembrane helix in either the glycophorin A monomer or dimer. In contrast, the spectra obtained at 60°C exhibit a slight narrowing of the overall deuterium lines shape relative to the spectra obtained at 20°C. The spectral changes that occur between 20°C and 60°C are most clearly seen in the relative intensities of the two most intense side bands. The narrowing of the line shape at 60°C may result from increased motion about the Cα-Cβ bond (see Simulations below) or increased axial rotation of the peptide in the membrane.

The deuterium line shape of Val82 at 20°C is slightly narrower than that of Val80 and Val84. This is clearly seen in the change in the relative intensities of the two most intense side bands (circled). Narrowing of the line shape is not unexpected because Val82 is not in the dimer interface and is positioned one helical turn above Gly86 in the sequence. Fig. 1 clearly shows that the space created by Gly86 eliminates the potential for side chain–side chain contacts as seen for Val80 and Val84. The narrowing must result from increased rotation about the Cα-Cβ bond because there was no evidence for axial rotation of the dimer in the spectra of deuterated Val80 and Val84 at 20°C.

Fig. 2 d presents deuterium spectra of Val84 in the glycophorin A monomer. The monomer is produced by substituting Leu75 with valine. This substitution is known to completely disrupt dimerization (Lemmon et al., 1992). The striking result is that specifically deuterated Val84 in the monomer exhibits the same line shape as in the dimer, indicating fast methyl rotation with virtually no motion about the Cα-Cβ bond.

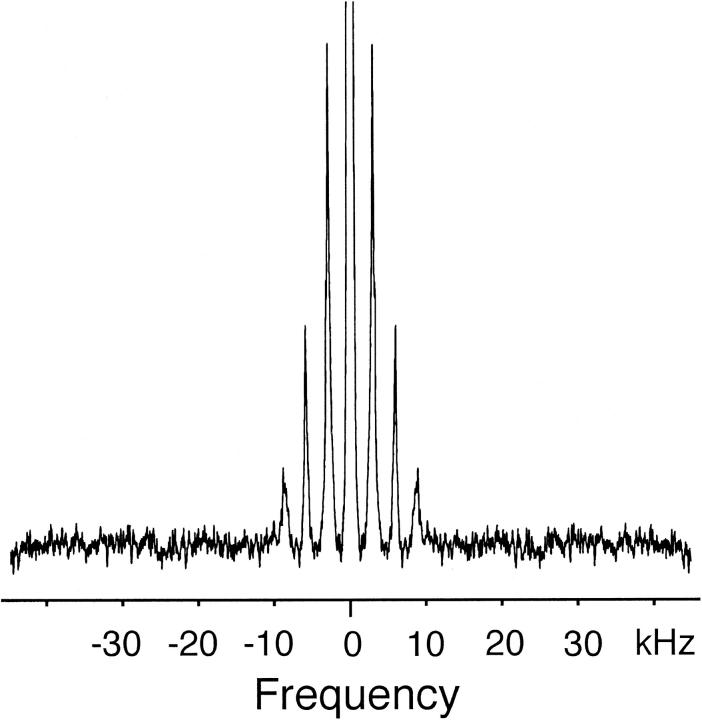

Fig. 3 presents the spectra of glycophorin A deuterated at the side-chain methyl group of Met81. This spectrum is included for comparison to the valine spectra. Met81 is not β-branched and the terminal CD3 methyl group of methionine is at the end of a long flexible side chain. Consistent with increased motion, the deuterium line shape is considerably narrower than that observed for valine under the same experimental conditions of temperature, hydration, and lipid-to-protein ratio.

FIGURE 3.

Deuterium NMR spectrum of CD3 methyl group of Met81 in glycophorin A at 20°C. The breadth of the side-band manifold is much narrower than those observed for the deuterated valines in Fig. 2 due to conformational flexibility of the long methionine side chain. Glycophorin A peptides were reconstituted into DMPC multilayers at a 1:40 peptide:lipid molar ratio and hydrated with ∼50 wt% deuterium-depleted water. The experimental conditions are identical to those in Fig. 2.

Simulations

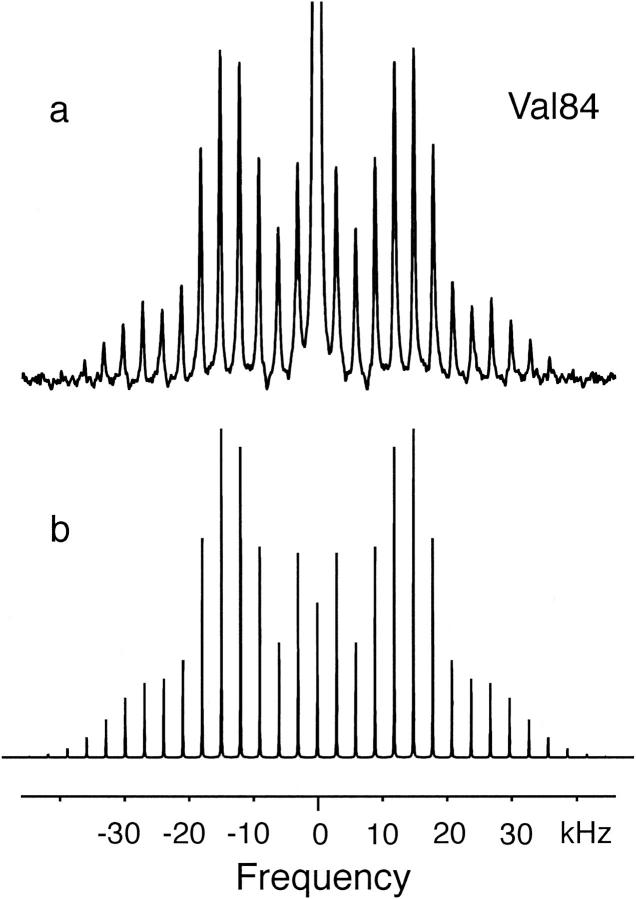

Simulation of the side-band intensities in the MAS spectrum of Val84 is relatively straightforward with the program SIMPSON because rapid methyl group rotation results in an axially symmetric line shape (η = 0). Fig. 4 compares the experimental Val84 spectrum with a simulation produced using an asymmetry parameter η of 0, a MAS frequency of 3 kHz, and an effective quadrupole coupling constant of 49 kHz. The 49 kHz effective quadrupole coupling constant is identical to that observed for valine methyl deuterons in gramicidin by Koeppe and co-workers (Jude et al., 1999). The simulation is remarkably similar to the experimental spectrum indicating that the data are consistent with the proposed model of only rapid methyl group rotation. Changing the asymmetry parameter to 0.1 and the effective quadrupole coupling constant to 47 kHz clearly changes the relative side-band intensities in the simulation (see simulation for Val82 in Fig. 6 below).

FIGURE 4.

Experimental (a) and simulated (b) MAS spectra of Val84 at 20°C. The simulation was done using the program SIMPSON with an effective quadrupole coupling constant of 49 kHz, an asymmetry parameter η of 0, and a spinning speed of 3 kHz.

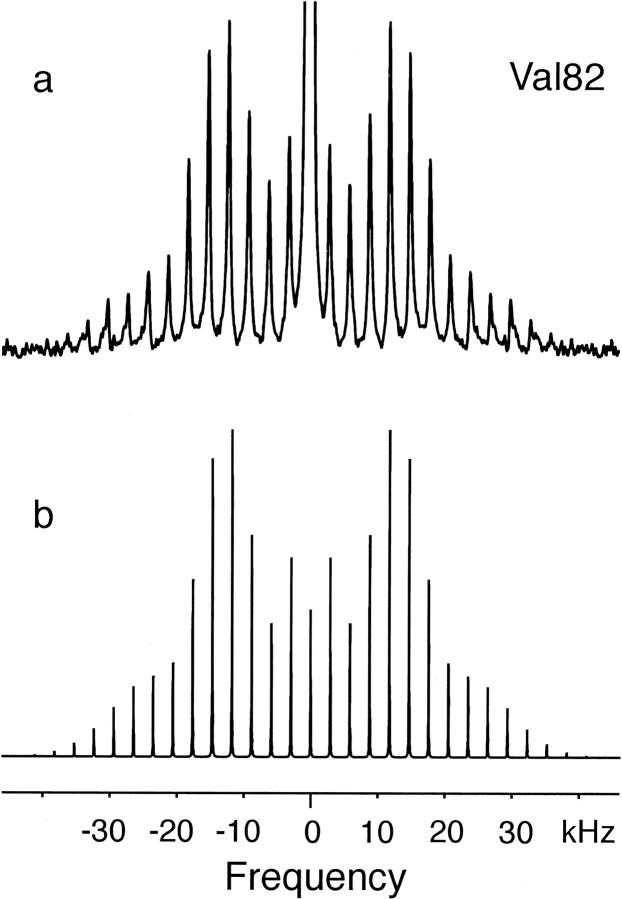

FIGURE 6.

Experimental (a) and simulated (b) MAS spectra of Val82 at 20°C. The simulation was done using the program SIMPSON with an asymmetry parameter η of 0.1. This asymmetry parameter assumes that motion about the Cα-Cβ bond is fast on the 2H NMR timescale and unequal populations (90:7:3) for occupancy of the three dominant rotamers. The best fit to the experimental spectrum was obtained using an effective quadrupole coupling constant of 47 kHz. The MAS frequency in both the experimental and simulated spectra was 3 kHz.

Simulation of the deuterium MAS spectrum of Val82 is more difficult because the line shape revealed by the side-band intensities is not axially symmetric and may be produced from motion in an intermediate exchange regime (Kristensen et al., 1998). In contrast, it is possible to simulate experimental static line shapes over a range of timescales and involving one or more axes of rotation. Fig. 5 presents a series of simulations of powder line shapes, using the program MXET1, that establish the range of motions that would be consistent with the narrowing of the Val82 line shape. For these simulations, we assume fast methyl group rotation by using an effective 49-kHz quadrupole coupling constant and explore the influence that rotation about the Cα-Cβ bond has on the line shape. The two key variables in these simulations are the populations (or occupancies) of the different rotamers and the jump rates between them.

FIGURE 5.

Static NMR simulations. A series of simulations of powder line shapes of fast methyl rotation superimposed upon rotation about the Cα-Cβ bond. Methyl group rotation was simulated simply using an effective quadrupole coupling constant of 46 kHz (a) or 49 kHz (b–d). The χ1 rotation was simulated by a three-site hop with a hop angle of 120°. For (a), the populations were 75:15:10 and the jump rate (105 s−1) was in the intermediate exchange regime. These conditions reproduce the deuterium spectra of Val6 and Val8 in gramicidin (Lee and Cross, 1994). For (b–d), the populations were 90:7:3 and the jump rates were in the slow (102 s−1)(b), intermediate (105 s−1) (c), and fast (108 s−1) (d) exchange regimes. Comparison of (a) and (c) highlights the effect on the deuterium line shape of changing the relative rotamer populations. Exponential line broadening of 1.5 kHz was applied to all spectra.

Fig. 5 a presents the line shape simulated by an unequal occupancy ratio of 75:15:10 and a jump rate of 105 s−1 in the intermediate (μs) exchange regime. This simulation matches the experimental line shape observed by Lee and Cross (1994) for Val6 and Val8 in gramicidin, and is included here to illustrate the dramatic difference that changing the relative populations and rates has on the observed line shape. Fig. 5, b–d, present a series of simulations using an occupancy ratio of 90:7:3 consistent with the rotamer distribution of valine in α-helices obtained from an analysis of soluble protein crystal structures (Lovell et al., 2000). Rotation about the Cα-Cβ bond was simulated by a three-site hop with a hop angle of 120° and jump rates in the slow (b), intermediate (c), and fast (d) time regimes. Using a jump rate of 102 s−1 (b), the line shape is axially symmetric. This line shape is indistinguishable from that resulting from only fast methyl rotation. The observed splitting of 36 kHz corresponds to an effective quadrupole coupling constant of 49 kHz. However, when the jump rate is increased to 105 s−1 in (c) the observed splitting decreases from 36 kHz to ∼29 kHz and there is increased intensity in the center of the spectrum. This line shape simulation was made using the same jump rate as in Fig. 5 a, but is distinctly different due to the differences in rotamer populations. In the fast exchange limit (108 s−1), there is a slight decrease in the spectral intensity in the center of the spectrum. However, this intensity is still significantly higher than in (b). Importantly, comparison of the static line shapes in Fig. 5, b–d, with the MAS spectra in Fig. 2 shows that the narrowing of the quadrupole splitting observed in the Val82 spectrum is consistent with intermediate to fast rotation about the Cα-Cβ bond if the rotamer distribution favors a single orientation.

In the regime where motions are fast on the 2H NMR timescale, the line shape analysis problem is particularly simple. For a discrete motional process among n sites, the motionally averaged electric field gradient (EFG) tensor is

|

(1) |

where P(Ωk) are the site probabilities (Wittebort et al., 1987). Each of the static tensors Vij(Ωk) are expressed in a common reference frame according to the following transformation

|

(2) |

where R(Ωk) has been used to rotate the axially symmetric 2H EFG tensor VPAS in its principal axis system (PAS) to an arbitrary orientation (Ωk) = (θ, φ). Diagonalizing the motionally averaged EFG tensor of Eq. 1 then yields the residual principal components  , and the asymmetry parameter

, and the asymmetry parameter

|

(3) |

Applying this formalism to describe the effects of rapid interconversion among the valine conformers about the Cα-Cβ bond, we have used a three-state model with the following populations and site orientations to describe the jumps about the χ1 torsion angle:

|

(4) |

|

(5) |

|

(6) |

Diagonalizing the motionally averaged EFG tensor  defined by Eq. 1 for this motional model, we find η = 0.1048.

defined by Eq. 1 for this motional model, we find η = 0.1048.

Using this value of η, Fig. 6 presents a simulation of the Val82 MAS spectrum. The best fit to the side-band intensities required using an effective quadrupole coupling constant of 47 kHz for fast methyl group rotation rather than 49 kHz as in Fig. 4. The simulation clearly shows that the observed Val82 spectrum is consistent with fast rotation about the Cα-Cβ bond if the rotamer distribution favors a single conformer.

DISCUSSION

The transmembrane domain of glycophorin A serves as a simple model system for understanding the nature of the interactions that drive helix association in membrane bilayers (MacKenzie et al., 1997; Smith et al., 2001). One of the unexpected features of the dimer interface of glycophorin A was the occurrence of glycine. Glycine lacks a side chain and is known to function as a helix breaker in soluble proteins. Using the structure of the glycophorin A dimer as a guide, Engelman and co-workers identified GXXXG as a major motif in the Swiss-Prot data base (Senes et al., 2000) and in TOXCAT (ToxR chloramphenicol acetyltransferase) screens of designed sequence libraries (Russ and Engelman, 1999). More recently, in an analysis of helix packing interactions in the crystal structures of polytopic membrane proteins, we have shown that glycine is well-tolerated in transmembrane helices and is part of a general helix interaction motif involving small and polar residues (Javadpour et al., 1999; Eilers et al., 2000; Eilers et al., 2002).

A second unexpected feature of the glycophorin A dimer interface is the predominance of β-branched amino acids (Senes et al., 2000). Of the seven residues in the dimerization motif of glycophorin A, four are β-branched. β-branched amino acids generally have low propensities in the helices and high propensities in the β-sheet regions of soluble proteins. Nevertheless, these amino acids are abundant in the transmembrane helices of membrane proteins (Eilers et al., 2002). In the membrane structure of the glycophorin A dimer, three of the four β-branched amino acids (Ile76, Val80, Val84) in the dimerization motif form a ridge of tightly packed side chains (Smith and Bormann, 1995; Smith et al., 2001). Engelman and co-workers suggested that β-branched Val80 and Val84 may facilitate dimerization by helping to shape a preformed surface (MacKenzie et al., 1997). This idea was directly tested by the deuterium NMR measurements presented above.

The deuterium NMR spectra of Val84 in the monomeric and dimeric glycophorin A peptides are remarkably similar and are dominated by fast methyl rotation. There is no evidence for rotation about the Cα-Cβ bond. This is consistent with restriction of the side chain in both the monomer and dimer due to intrahelical packing interactions involving the β-methyl group, and indicates that there is no energy cost associated with dimerization due to loss of conformational entropy. In contrast, deuterium spectra of Met81 and Val82 in the lipid interface reflect greater motional averaging and fast exchange between different side-chain conformers.

Comparison of the mobility of Val84 in monomeric glycophorin A with Val82 is important because both valines face lipid, but exhibit different motions. The side chain of Val84 only exhibits fast methyl rotation, while the side chain of Val82 is consistent with fast rotation about both the Cβ-CH3 and Cα-Cβ bonds. This comparison suggests that the additional contacts between the β-branched side chains of Val80 and Val84 in both the monomer and dimer serve to restrict side-chain motion. To quantitatively assess the packing of the three transmembrane valine residues, we calculated amino acid packing values in the glycophorin A dimer and monomer using the method of occluded surfaces (Pattabiraman et al., 1995; DeDecker et al., 1996). The average amino acid packing value for the transmembrane region of helical membrane proteins is 0.441 (Eilers et al., 2002). Surface residues generally have packing values in the range of 0.2–0.3, whereas the most tightly packed buried residues have packing values in the range of 0.5–0.6. The OC analysis yields relatively high packing values for Val80 (0.465) and Val84 (0.459) in the membrane structure of the glycophorin A dimer (Smith et al., 2001). The packing values for Val80 (0.270) and Val84 (0.247) in the monomer are significantly less than the packing values for the dimer, as might be expected. The packing value of Val82 (0.205) in the monomer and dimer is substantially lower than either Val80 or Val84 in the monomer. Val82 is above Gly86 in the glycophorin A sequence and the most significant side chain contact of Val82 is with the backbone carbonyl of Phe78. In a similar fashion, the side-chain methyl groups of Val80 and Val84 have contacts to the backbone carbonyl of the i−4 amino acid. However, in contrast to Val82 these two interfacial valines exhibit significant intrahelical contacts to the side-chain groups of the i+4 amino acids. For Val82, the i+4 amino acid is glycine. Together the deuterium NMR data and the packing analysis of the monomer and dimer structures of glycophorin A support the idea that the correlation observed by Engelman and co-workers (Senes et al., 2000) between β-branched amino acids at positions i and i−4 may be related to the role of β-branched amino acids in helix association.

The deuterium NMR measurements on Val82 also allow us to address the more general question concerning the motion of valine in α-helices. As mentioned in the introduction, valine typically exists in a single rotameric state when it occurs in α-helical secondary structure. We show that simulations of valine having predominantly a single rotamer (i.e., 90:7:3), but in fast exchange, are consistent with the intensity changes observed in the MAS spectra of Val82. This suggests that the rotamer distribution results from a thermodynamic equilibrium rather than from a kinetic barrier that prevents conversion between different conformations.

These studies highlight the advantages of deuterium MAS NMR studies for characterizing the dynamics of side chains and investigating the oligomerization of transmembrane helices. Deuterium is a relatively insensitive nucleus because it has a low gyromagnetic ratio and the spectral intensity is generally spread over an extremely wide frequency range due to the quadrupole interaction. Magic angle spinning makes measurements of deuterium quadrupole couplings feasible in biological systems (Liu et al., 1998) where the amount of sample required for static experiments is often a serious limitation. For studies on oligomerization, deuterium MAS spectra can greatly complement other MAS NMR methods, such as rotational resonance (Peersen et al., 1995) or rotational-echo double-resonance (Gullion and Schaefer, 1989). In contrast to valine, the long flexible side chains of leucine or methionine would make better probes of helix-helix interfaces due to the significant differences between free and restricted line shapes.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the late Dr. Regitze Vold for the program MXET1, Dr. Niels Nielsen for the program SIMPSON, and Jim Elliott at the Keck Peptide Facility at Yale University for peptide synthesis. We thank Ann McDermott for helpful comments concerning the deuterium NMR simulations.

This research was supported at Stony Brook by the National Institutes of Health (S.O.S., GM-46732), the National Science Foundation (Instrumentation Grant No. 9907840), and the W. M. Keck Foundation. At Lethbridge, research was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, and by the Office of the Vice President for Research.

References

- Bak, M., J. T. Rasmussen, and N. C. Nielsen. 2000. SIMPSON: A general simulation program for solid-state NMR spectroscopy. J. Magn. Reson. 147:296–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beshah, K., E. T. Olejniczak, and R. G. Griffin. 1987. Deuterium NMR study of methyl-group dynamics in L-alanine. J. Chem. Phys. 86:4730–4736. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, M., and I. C. P. Smith. 1985. Manifestations of lipid-protein interactions in deuterium NMR. In Progress in Protein-Lipid Interactions. A. Watts, J. J. H. H. M. De Pont, editors. Elsevier, Amsterdam. 61–88.

- DeDecker, B. S., R. O'Brien, P. J. Fleming, J. H. Geiger, S. P. Jackson, and P. B. Sigler. 1996. The crystal structure of a hyperthermophilic archaeal TATA-box binding protein. J. Mol. Biol. 264:1072–1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eilers, M., S. C. Shekar, T. Shieh, S. O. Smith, and P. J. Fleming. 2000. Internal packing of helical membrane proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 97:5796–5801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eilers, M., A. B. Patel, W. Liu, and S. O. Smith. 2002. Comparison of helix interactions in membrane and soluble α-bundle proteins. Biophys. J. 82:2720–2736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, L. E., D. M. Engelman, and J. N. Sturgis. 1999. Detergents modulate dimerization, but not helicity, of the glycophorin A transmembrane domain. J. Mol. Biol. 293:639–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, K. G., A. L. Ackerman, and D. M. Engelman. 1997. The effect of point mutations on the free energy of transmembrane alpha-helix dimerization. J. Mol. Biol. 272:266–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, K. G., and D. M. Engelman. 2001. Specificity in transmembrane helix-helix interactions can define a hierarchy of stability for sequence variants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:14340–14344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, K. G. 2002. Standardizing the free energy change of transmembrane helix-helix interactions. J. Mol. Biol. 323:563–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield, M. S., A. D. Ronemus, R. L. Vold, R. R. Vold, P. D. Ellis, and T. E. Raidy. 1987. Deuterium quadrupole-echo NMR-spectroscopy. 3. Practical aspects of lineshape calculations for multiaxis rotational processes. J. Magn. Reson. 72:89–107. [Google Scholar]

- Gullion, T., and J. Schaefer. 1989. Detection of weak heteronuclear dipolar coupling by rotational-echo double-resonance NMR. In Advances in Magnetic Resonance, Vol. 13. W. S. Warren, editor. Academic Press, Inc., San Diego and London. 57–84.

- Javadpour, M. M., M. Eilers, M. Groesbeek, and S. O. Smith. 1999. Helix packing in polytopic membrane proteins: role of glycine in transmembrane helix association. Biophys. J. 77:1609–1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jude, A. R., D. V. Greathouse, M. C. Leister, and R. E. Koeppe, II. 1999. Steric interactions of valines 1, 5, and 7 in [valine 5, D-alanine 8] gramicidin A channels. Biophys. J. 77:1927–1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keniry, M. A., H. S. Gutowsky, and E. Oldfield. 1984a. Surface dynamics of the integral membrane protein bacteriorhodopsin. Nature. 307:383–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keniry, M. A., A. Kintanar, R. L. Smith, H. S. Gutowsky, and E. Oldfield. 1984b. Nuclear magnetic resonance studies of amino acids and proteins. Deuterium nuclear magnetic resonance relaxation of deuteriomethyl-labeled amino acids in crystals and in Halobacterium halobium and Escherichia coli cell membranes. Biochemistry. 23:288–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsey, R. A., A. Kintanar, M. D. Tsai, R. L. Smith, N. Janes, and E. Oldfield. 1981. First observation of amino acid side chain dynamics in membrane proteins using high field deuterium nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J. Biol. Chem. 256:4146–4149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen, J. H., G. L. Hoatson, and R. L. Vold. 1998. Investigation of multiaxial molecular dynamics by 2H MAS NMR spectroscopy. Solid State Nucl. Magn. Reson. 13:1–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lague, P., M. J. Zuckermann, and B. Roux. 2001. Lipid-mediated interactions between intrinsic membrane proteins: dependence on protein size and lipid composition. Biophys. J. 81:276–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K. C., and T. A. Cross. 1994. Side-chain structure and dynamics at the lipid-protein interface: Val1 of the gramicidin A channel. Biophys. J. 66:1380–1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K. C., S. Huo, and T. A. Cross. 1995. Lipid-peptide interface: valine conformation and dynamics in the gramicidin channel. Biochemistry. 34:857–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemmon, M. A., J. M. Flanagan, H. R. Treutlein, J. Zhang, and D. M. Engelman. 1992. Sequence specificity in the dimerization of transmembrane alpha-helices. Biochemistry. 31:12719–12725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F., R. Lewis, R. S. Hodges, and R. N. McElhaney. 2002. Effect of variations in the structure of a polyleucine-based α-helical transmembrane peptide on its interaction with phosphatidylcholine bilayers. Biochemistry. 41:9197–9207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, K., J. Williams, H. R. Lee, M. M. Fitzgerald, G. M. Jensen, D. B. Goodin, and A. E. McDermott. 1998. Solid-state deuterium NMR of imidazole ligands in cytochrome c peroxidase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120:10199–10202. [Google Scholar]

- Lovell, S. C., J. M. Word, J. S. Richardson, and D. C. Richardson. 2000. The penultimate rotamer library. Proteins. 40:389–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie, K. R., J. H. Prestegard, and D. M. Engelman. 1997. A transmembrane helix dimer: structure and implications. Science. 276:131–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, D., and L. I. Horvath. 1998. Structure, dynamics and composition of the lipid-protein interface. Perspectives from spin-labelling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Rev. Biomembr. 1376:267–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morein, S., J. A. Killian, and M. M. Sperotto. 2002. Characterization of the thermotropic behavior and lateral organization of lipid-peptide mixtures by a combined experimental and theoretical approach: effects of hydrophobic mismatch and role of flanking residues. Biophys. J. 82:1405–1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattabiraman, N., K. B. Ward, and P. J. Fleming. 1995. Occluded molecular surface: analysis of protein packing. J. Mol. Recognit. 8:334–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peersen, O. B., M. Groesbeek, S. Aimoto, and S. O. Smith. 1995. Analysis of rotational resonance magnetization exchange curves from crystalline peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117:7228–7237. [Google Scholar]

- Popot, J. L., and D. M. Engelman. 2000. Helical membrane protein folding, stability, and evolution. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69:881–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russ, W. P., and D. M. Engelman. 1999. TOXCAT: a measure of transmembrane helix association in a biological membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96:863–868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senes, A., M. Gerstein, and D. M. Engelman. 2000. Statistical analysis of amino acid patterns in transmembrane helices: the GxxxG motif occurs frequently and in association with beta-branched residues at neighboring positions. J. Mol. Biol. 296:921–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senes, A., I. Ubarretxena-Belandia, and D. M. Engelman. 2001. The Cα-H…O hydrogen bond: a determinant of stability and specificity in transmembrane helix interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:9056–9061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe, S., K. R. Barber, C. W. M. Grant, D. Goodyear, and M. R. Morrow. 2002. Organization of model helical peptides in lipid bilayers: insight into the behavior of single-span protein transmembrane domains. Biophys. J. 83:345–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siminovitch, D. J. 1998. Solid-state NMR studies of proteins: the view from static 2H NMR experiments. Biochem. Cell Biol. 76:411–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S. O., and B. J. Bormann. 1995. Determination of helix-helix interactions in membranes by rotational resonance NMR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 92:488–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S. O., D. Song, S. Shekar, M. Groesbeek, M. Ziliox, and S. Aimoto. 2001. Structure of the transmembrane dimer interface of glycophorin A in membrane bilayers. Biochemistry. 40:6553–6558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S. O., M. Eilers, D. Song, E. Crocker, W. W. Ying, M. Groesbeek, G. Metz, M. Ziliox, and S. Aimoto. 2002. Implications of threonine hydrogen bonding in the glycophorin A transmembrane helix dimer. Biophys. J. 82:2476–2486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittebort, R. J., E. T. Olejniczak, and R. G. Griffin. 1987. Analysis of deuterium nuclear-magnetic-resonance line-shapes in anisotropic media. J. Chem. Phys. 86:5411–5420. [Google Scholar]

- Ying, W. W., S. E. Irvine, R. A. Beekman, D. J. Siminovitch, and S. O. Smith. 2000. Deuterium NMR reveals helix packing interactions in phospholamban. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122:11125–11128. [Google Scholar]