Abstract

The thermal unfolding of a series of 6-, 10-, and 14-mer cyclic β-hairpin peptides was studied to gain insight into the mechanism of formation of this important secondary structure. The thermodynamics of the transition were characterized using temperature dependent Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Thermodynamic data were analyzed using a two-state model which indicates increasing cooperativity along the series. The relaxation kinetics of the peptides in response to a laser induced temperature jump were probed using time-resolved infrared spectroscopy. Single exponential relaxation kinetics were observed and fit with a two-state model. The folding rate determined for these cyclic peptides is accelerated by some two orders of magnitude over the rate of a linear peptide that forms a β-hairpin. This observation supports the argument that the rate limiting step in the linear system is either stabilization of compact collapsed structures or rearrangement of collapsed structures over a barrier to achieve the native interstrand registry. Small activation energies for folding of these peptides obtained from an Arrhenius analysis of the rates imply a primarily entropic barrier, hence an organized transition state having specific stabilizing interactions.

INTRODUCTION

Small peptide models have proven to be invaluable experimental systems for studying the fundamental processes of protein folding (reviewed in Callender et al., 1998; Eaton et al., 1998). Many of the essential elements of protein folding, including hydrophobic collapse, hydrogen bond formation, and side-chain packing have been observed in the folding of peptide models (Espinosa and Gellman, 2000; Krantz et al., 2000; Ramirez-Alvarado et al., 1999; Syud et al., 2001). Studies of helical peptides have been particularly successful in elucidating the dynamics of helix nucleation and propagation, and helix-helix interactions. (Werner et al., 2002; Williams et al., 1996) The study of β-structures has been more difficult due to the scarcity of suitable model systems. Some of the problems associated with β-sheet peptide models include their tendency to be large, prone to aggregate, not very stable, and low in secondary structure content.

Significant breakthroughs have been made recently in the design of stable and soluble peptides with β-turn and β-sheet structures (Griffiths-Jones et al., 1999; Jäger et al., 2001; Kortemme et al., 1998; Schenck and Gellman, 1998; Smith and Regan, 1997). The dynamics of folding of one such system, the 16-residue C-terminal β-hairpin fragment of protein G, have been studied by Muñoz et al. (1997, 1998). They observed apparent two-state relaxation kinetics of the β-hairpin structure using laser induced temperature jump (T-jump) and time-resolved fluorescence measurements of the native Trp in this fragment. The relaxation kinetics were analyzed using a statistical mechanical kinetic zipper model. Using this model, they calculate a folding lifetime of 6 μs for the hairpin. This is substantially slower than the folding lifetimes of ∼200 ns reported for similarly sized helical peptides under similar conditions (Werner et al., 2002; Williams et al., 1996). The slower rate is rationalized within the kinetic zipper model by assuming that the hydrogen bond propagation rate is the same in both instances, which implies that the nucleation of a stable turn is much slower than helix nucleation. Muñoz et al. postulate that hairpin nucleation is slow because it requires a cooperative stabilization by hydrophobic side chain interactions.

The folding of the β-hairpin fragment of protein G has also been studied using Langevin simulations of minimal off-lattice models (Klimov and Thirumalai, 2000) and all atom molecular dynamics (Pande and Rokhsar, 1999) and multicanonical Monte Carlo simulations (Dinner et al., 1999). These studies find that the hairpin folds via discrete intermediates, or through a hierarchy of structural changes involving hydrophobic collapse, hydrogen bond formation, and side chain ordering. The model of Muñoz et al. suggests that folding nucleates at the turn, followed by a zipping of the structure. The hydrophobic core is formed subsequent to the turn, and stabilizes the structure. In contrast, the simulations of Dinner et al. predict that hydrophobic collapse and rearrangement to produce a native-like topology is the key initial step, followed by hydrogen bond formation. Thus, formation of a collapsed, native-like topology serves as a nucleating event, with hydrogen bonds propagating outward from the hydrophobic core. These models predict fundamentally different roles for the formation of the turn versus the hydrophobic core in the folding mechanism of this β-hairpin structure. In either case, hydrogen bond formation is seen as a fast propagation step that follows the nucleating event. The relative importance of hydrophobic interactions versus turn formation in facilitating chain collapse and formation of the native topology remains unresolved. The rate of hydrogen bond propagation and how it compares to that in helical systems is also not known.

We have explored the dynamics of β-turn formation and hydrogen bond propagation within a series of 6-, 10-, and 14-mer cyclic β-hairpin analogs of Gramicidin S (GS) using equilibrium Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy and T-jump relaxation probed by time-resolved infrared (IR) spectroscopy. Cyclic peptides have gained increasing attention in recent years as a result of their antimicrobial properties and membrane permeation capabilities (Fernandez-Lopez et al., 2001). GS is one such cyclic peptide [cyclo(-Val-Orn-Leu-D-Phe-Pro-)2] having antibiotic properties and an amphipathic nature. Studies of the sequence-dependent biophysical properties of GS analogs have been used to examine the effects of hydrophobicity, amphipathicity, and β-hairpin turn propensity (Gibbs et al., 2002; Jelokhani-Niaraki et al., 2000, 2001; Kondejewski et al., 2002; McInnes et al., 2000) These studies provide useful insight into the antimicrobial and hemolytic activities of GS. What is lacking, however, is an understanding of the structural dynamics that are critical to the biological activity of GS.

The cyclic 6-, 10-, and 14-mer β-hairpin peptides are excellent model systems because a study of length dependence of the dynamics is possible, with the number of intramolecular hydrogen bonds increasing from two to four to six along the series. Additionally, these peptides are sterically constrained in their search of conformational space, and consequently, turn formation and hydrogen bond propagation can be measured separately from chain diffusion (collapse) processes. The solution structures of the 6-, 10-, and 14-mer peptides have been solved by NMR (Gibbs et al., 1998). They form stable antiparallel β-hairpin structures, bordered by two type II′ β-turns. We have modeled the relaxation behavior of these peptides using a two-state model, from which we extract folding rates and activation parameters.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Peptides

Synthesis of the cyclic β-hairpin peptides was performed by Gibbs et al. (1998) with the first and last residues in the sequence linked in the cyclization. The sequences of the peptides used in these studies are as follows, where Tyr residues are of D stereochemistry:

|

The samples were purified by reverse phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and deuterium exchanged by repeated lyophilization from D2O. Trifluoroacetic acid, which was used in the HPLC purification, was present as an impurity in all samples. Samples were dissolved in D2O (99.9%, Sigma), and final concentrations were found to be in the range of 1–4 mM as determined by the UV absorption of Tyr at 274 nm.

Infrared spectroscopy

The equilibrium melting behavior of the cyclic peptides was studied using FTIR spectroscopy. FTIR spectra were collected on a Biorad (Boston, MA) FTS-40 interferometer using a temperature controlled IR cell. The IR cell contained both the sample and a D2O reference solution with trifluoroacetic acid between CaF2 windows with a 100 μm spacer. The cell is translated laterally under computer control to acquire matching sample and reference single beam spectra, and the protein absorption spectrum is computed as −log(Isamp/Iref). It is critical to match the sample and reference solutions as closely as possible, particularly with regard to H2O content, because of the overlap of the temperature-dependent spectrum of HOD with the protein spectrum in the region of interest. Temperature-dependent spectra in the amide I′ (the prime indicates the deuterated amide group) region from 1600–1700 cm–1 were baseline corrected using a linear baseline to account for the small differences in the broad HOD absorption. The baseline corrections required were typically smaller than 1 mOD, or less than 1% of the observed protein signal.

T-jump relaxation measurements

The T-jump relaxation apparatus has been described previously (Williams et al., 1996). Briefly, a laser induced T-jump is used to rapidly shift the folding/unfolding equilibrium, and the relaxation kinetics are measured using time-resolved infrared spectroscopy. The T-jump perturbation generated by a laser heating pulse is faster than the molecular dynamics of interest. The T-jump pulse is generated by Raman shifting a Q-switched Nd:YAG (DCR-4, Spectra Physics, Mountain View, CA) fundamental at 1064 nm in H2 gas (1-Stokes shift), producing a 10-ns pulse at 1.91 μm. The near infrared wavelength is partially absorbed by the D2O (ɛ ∼ 6 cm−1, or 87% transmittance in a 100-μm path length cell), and the absorbed energy is rapidly thermalized within the irradiated volume. The magnitude of the T-jump produced depends on the per pulse energy and the focus of the laser, typically 40 mJ and 1-mm spot diameter, respectively, which yields an 11°C T-jump. The mid-IR probe beam is a continuous wave lead-salt diode laser (Laser Components, Olching, Germany) with a tunable output range of 1600–1700 cm−1. The probe beam is focused to a 50 μm (1/e2 diameter) spot at the center of the heated volume. Probing only the center of the heated volume ensures a uniform temperature distribution in the probe volume by avoiding the temperature gradient produced on the wings of the Gaussian pump beam (Wray et al., 2002). The transient transmission of the probe beam through the sample is measured using a fast (100 MHz) photovoltaic MCT IR detector/preamplifier (Kolmar Technologies, Newburyport, MA). Transient signals are digitized and signal averaged using a Tektronics digitizer (7612D, Beaverton, OR). Instrument control and data collection are accomplished using a LabVIEW computer program.

Very high dynamic range is achieved in these transient IR measurements using a simple procedure to measure the total transmitted intensity of the probe beam independently from the transient change in the transmission due to the T-jump. The detector and amplifier are DC coupled to maximize the bandwidth of the measurement (to cover the range from 100 MHz–1 Hz). The amplitude of the transmitted probe beam (I0) is measured using an optical chopper, and the DC offset of the detector preamplifier is adjusted to null the DC signal. The transient signal (ΔI) is then measured in the presence of the pump beam, and the transient absorbance is computed as:

|

(1) |

In this way, the full dynamic range of the detector, amplifier, and digitizer is exploited to measure the transient signal. Measurements of the transient absorbance for both the sample and the reference were collected from 10−9 to 10−1 s, and relaxation times were obtained using a deconvolution process described below.

Analysis of kinetics data

Accurate determination of the peptide relaxation kinetics requires deconvolution of the instrument response function from the observed kinetics. Very accurate deconvolution of the instrument response is possible because it is determined concurrently with each sample measurement under the exact same conditions. Using a macro created using IGOR (WaveMetrics, Inc., Lake Oswego, OR), the observed sample relaxation kinetics are fit as a function of the instrument response convolved with an exponential decay. The instrument response function for the system is taken to be the derivative of the reference trace, normalized to have an integral of 1 at the maximum of the reference trace. Normalizing the instrument response is necessary so that amplitudes represent changes in absorbance. The decay function used is an exponential decay with the formula (A × exp(−kT)), where A and k are the change in absorbance and the rate, respectively. The reported relaxation rates represent an average of at least seven separate trials, and the reported uncertainties represent the standard deviation of the average values.

RESULTS

Equilibrium FTIR studies

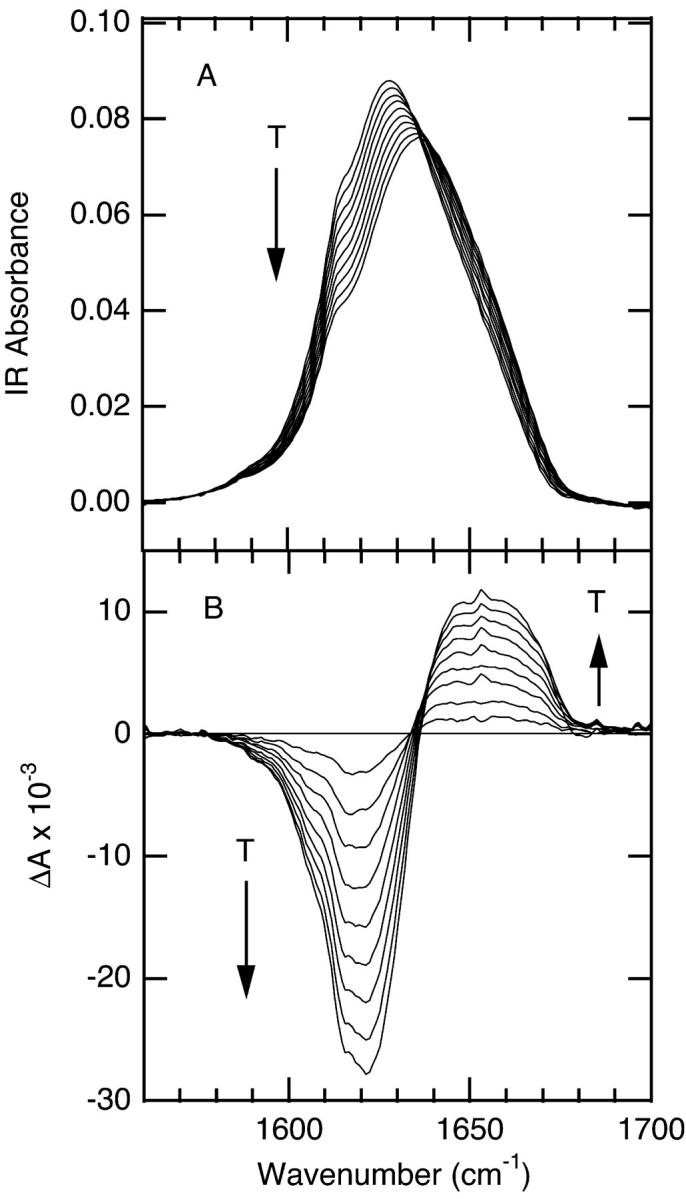

All three cyclic peptides adopt β-hairpin (folded) structures in solution at room temperature (Gibbs et al., 1998). We have studied the temperature induced unfolding in the range from 1°C to 85°C using FTIR spectroscopy. We focus on the amide I′ spectral region because this vibrational mode is an established indicator of secondary structure (Arrondo et al., 1996; Susi and Byler, 1986). This broad, multicomponent band contains contributions from the entire polypeptide backbone, which in this case adopts either a β-sheet, β-turn, or disordered conformation. The absorption spectra as a function of temperature for the 6-, 10-, and 14-mer are shown in Figs. 1 A, 2 A, and 3 A, respectively. The amide I′ maximum at room temperature is similar to that previously reported for GS in D2O (Lewis et al., 1999), with a peak maximum at 1632 cm−1. The changes with temperature are highlighted in the difference spectra for each peptide, in Figs. 1 B, 2 B, and 3 B, respectively. These difference spectra are generated by subtraction of the lowest temperature spectrum from each of the absorbance spectra at higher temperatures. The amide I′ envelopes of all three peptides were simultaneously deconvolved using a multi-Gaussian global fitting routine in IGOR (WaveMetrics). The number of subcomponents and their frequencies was determined from the second derivative of the absorbance spectra. The frequencies and peak areas from the global fit are reported in Table 1.

FIGURE 1.

Temperature-dependent FTIR spectra for the 6-mer cyclic peptide, 3.4 mM in D2O, minimal salt. (A) Absorbance spectra in the amide I′ region; the temperatures of the individual traces range from 2°C to 85°C from top to bottom with ∼10°C intervals. (B) Difference spectra obtained by subtracting the spectrum at 2°C from the spectra at higher temperatures.

FIGURE 2.

Temperature-dependent FTIR spectra for the 10-mer cyclic peptide, 2.9 mM in D2O, minimal salt. (A) Absorbance spectra in the amide I′ region; the temperatures of the individual traces range from 1°C to 85°C from top to bottom with ∼10°C intervals. (B) Difference spectra obtained by subtracting the spectrum at 1°C from the spectra at higher temperatures.

FIGURE 3.

Temperature-dependent FTIR spectra for the 14-mer cyclic peptide, 2.4 mM in D2O, minimal salt. (A) Absorbance spectra in the amide I′ region; the temperatures of the individual traces range from 2°C to 83°C from top to bottom with ∼10°C intervals. (B) Difference spectra obtained by subtracting the spectrum at 2°C from the spectra at higher temperatures.

TABLE 1.

| Assignment | β-turn | β-sheet (in) | β-sheet (out) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6-mer | |||

| Frequency (cm−1) | 1623 | 1637 | 1657 |

| Area | 1.87 | 1.11 | 0.11 |

| 10-mer | |||

| Frequency (cm−1) | 1625 | 1636 | 1658 |

| Area | 1.81 | 2.47 | 0.44 |

| 14-mer | |||

| Frequency (cm−1) | 1624 | 1635 | 1655 |

| Area | 1.90 | 3.53 | 1.32 |

Derived from deconvolution analysis of FTIR spectrum at 10°C.

The deconvolution analysis reveals three components of the amide I′ band at 10°C, centered near 1625, 1636, and 1658 cm−1 (Table 1). All three of these spectral components decrease in intensity with increasing temperature. These components of amide I′ arise from the folded structure, which is highly populated at low temperature, and are therefore due to the β-turn and antiparallel β-sheet backbone conformations present in the folded state. We assign the peak at ∼1625 cm−1 to the β-turns on the basis of its low frequency (characteristic of β-turns) and constant intensity across the series (all three peptides contain two type II′ β-turns). Two peaks are observed for the β-sheet, consistent with the structure that contains inward and outward directed C=O groups, i.e., intra- and intermolecular (to water) hydrogen bonding, respectively. We assign the peak at ∼1636 cm−1 to the inward directed C=O groups (intramolecular H-bonding) and the peak at ∼1658 cm−1 to the outward directed C=O groups (intermolecular H-bonding to water). There are several lines of evidence that support these assignments. First, the peak at 1658 cm−1 is similar in frequency to that observed for disordered polypeptide and therefore is most likely indicative of the C=O groups which are intermolecularly H-bonded to water. Second, the peak at 1658 cm−1 is always smaller than the 1636 cm−1 peak and altogether absent in the 6-mer. This absence of a peak for intermolecularly H-bonded carbonyl groups in the 6-mer is reasonable, since both of the sheet residues in this peptide exhibit intramolecular H-bonding. In contrast, the 10-mer will have 4 intra- and 2 intermolecular H-bonds, and the 14-mer will have 6 intra- and 4 intermolecular H-bonds. Consequently, the intermolecular H-bonding band is expected to be weaker than the intramolecular H-bonding band, and both bands should increase in intensity along the series, which is what is observed. Finally, these assignments are supported by the observed ratio of β-sheet/β-turn, which is 0.6, 1.6, and 2.6 for the 6-, 10-, and 14-mer, respectively, compared to the expected values of 0.5, 1.5, and 2.5.

A single broad component centered at 1660 cm−1 grows in with increasing temperature. The difference spectra for the 10- and 14-mer show the growth of this broad positive absorbance overlapped with the loss of the narrower high frequency β-sheet band near 1658 cm−1 (of negligible intensity in the 6-mer). The frequency and breadth of the 1660 cm−1 peak are characteristic of disordered polypeptide structure (Dyer et al., 1998; Werner et al., 2002; Williams et al., 1996). The FTIR spectra therefore provide clear evidence for the loss of folded conformation with increasing temperature.

The FTIR spectra of the 6-mer and 10-mer are concentration independent, and lack the amide I′ signature of aggregation (sharp peaks at 1615 and 1681 cm−1 (Colley et al., 2000; Zurdo et al., 2001)), evidence that these peptides are monomers in the concentration range of our experiments (1–4 mM). In contrast, the FTIR spectra of the 14-mer contain an aggregation signature (sharp peaks at 1615 and 1681 cm−1 seen in Fig. 3 B). The amplitudes of these features are concentration dependent and increase with time, especially at elevated temperatures. In addition, aggregation of the 14-mer peptide at concentrations above 70 μM was reported in a previous study (Jelokhani-Niaraki et al., 2001). Despite the presence of aggregated peptide, it is possible to monitor the monomer independently, via its distinct amide I′ bands. Thus it is possible to follow the unfolding of the monomer with increasing temperature, without interference from the aggregated peptide. The very weak temperature dependence of the aggregation peaks suggests that the aggregated form of the peptide is very stable over this temperature range, and does not contribute substantially to the monomer folding/unfolding equilibrium. Finally, the data for the 14-mer reported here were obtained under conditions where the maximum concentration of aggregated peptide was 11% of the total, estimated from the intensity of the aggregation peaks relative to the monomer peaks.

Melting curves derived from the temperature dependent IR absorbance for the three cyclic peptides are shown in Fig. 4. The solid lines represent fits to a two-state equilibrium model:

|

(2) |

where Ai and Af are the extrapolated absorbance values at the two endpoints of the transition, Tm is the transition midpoint, and ΔT represents the overall temperature range of the transition. The Tm and ΔT values from the two-state model fits are listed in Table 2. The melting transition for the 6-mer is so broad that it cannot be uniquely fit using the two-state model over the range of experimentally accessible temperatures. Consequently, the thermodynamic parameters derived for the 6-mer melting transition are not very reliable. They do reflect the general trend along the series, however, and hence are included for comparative purposes. The transition becomes increasingly sharper (smaller ΔT) as the peptide length increases. This trend reveals the increasing cooperativity along the series. Thermodynamic parameters derived from a van't Hoff analysis are also summarized in Table 2. The free energy of unfolding of these peptides is linear with temperature over an 80°C temperature range. The thermodynamic parameters reveal that the stability of the peptides increases with increasing peptide length. The substantial enthalpy gain is nearly counterbalanced by the unfavorable entropic cost of folding for both the 10-mer and 14-mer.

FIGURE 4.

FTIR melt curves for the 6-mer (•), 10-mer (▪), and 14-mer (▴) cyclic peptides obtained by plotting the change in IR intensity at the peak maximum of the β-turn band at 1621 cm−1, 1619 cm−1, and 1624 cm−1, respectively, versus temperature. The solid lines are fits to a two-state model (Eq. 2).

TABLE 2.

Cyclic peptide thermodynamic parameters of folding

| Tm (°C) | ΔT(°C) | ΔHf (kJ/mol) | ΔSf (J/mol·K) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6-mer* | 37 | 387 | −10 | −31 |

| 10-mer | 50.5 ± 0.3† | 139.4 ± 12.4 | −29.1 ± 0.4 | −89.8 ± 1.4 |

| 14-mer | 71.0 ± 2.3 | 84.1 ± 5.0 | −48.3 ± 0.5 | −140.4 ± 1.8 |

The breadth of the transition in this case precludes a unique fit; included for comparative purposes only.

Standard deviations are reported. Thermodynamic parameters are derived from a two-state model and a van't Hoff analysis.

Temperature-jump relaxation kinetics

The relaxation kinetics of the F→U transition following a laser induced T-jump were probed using time-resolved infrared spectroscopy in the amide I′ band. Fig. 5 displays the relaxation kinetics for the three peptides following a T-jump from 40°C to 51°C. A progressively slower relaxation time is clearly observed along the series for T-jumps to the same final temperature. The data are well fit by a single exponential decay in each case. All of the relaxation kinetics observed for these cyclic peptides are single exponentials, regardless of concentration, starting temperature, or magnitude of the T-jump. Furthermore, the equilibrium changes in the FTIR spectra as a function of temperature are best modeled in terms of two states (folded and unfolded structures), as discussed above. We have therefore analyzed the relaxation kinetics using a two-state model, for which the observed relaxation rate is the sum of the folding and unfolding rates, and the equilibrium constant is the ratio of these rates. The relaxation rates for all three peptides (Table 3) are close to the instrument response (response time = 28 ns, k = 3.6 × 107 s−1). Nevertheless, deconvolution of the instrument response from the observed relaxation kinetics is possible because the instrument response is very accurately determined for every relaxation measurement by the reference response. The observed relaxation rates are reproducibly resolved from the measured instrument response using the deconvolution procedure described above (in Methods). Folding and unfolding rates (Table 3) were extracted from the observed relaxation rates using the equilibrium constant determined from the static FTIR data.

FIGURE 5.

T-jump relaxation kinetics monitored in the amide I′ spectral region (1625 cm−1) following a jump from 40°C to 51°C. A single exponential fit is overlaid on each kinetics trace. The amplitudes are normalized to the 6-mer amplitude at long time (10 μs) to aid comparison of the relaxation times.

TABLE 3.

Kinetic parameters from T-jump measurements of the cyclic peptides

| kobs × 107 (s−1)†§ | kf × 107 (s−1) | ku × 107 (s−1) | ΔHf‡ (kJ/mol)¶ | ΔHu‡ (kJ/mol)¶ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6-mer | 2.4 ± 0.4 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | – | – |

| 10-mer | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | −17 ± 2 | 9 ± 1.0 |

| 14-mer | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.03 | −20 ± 6 | 23 ± 6 |

Standard deviations are reported.

Relaxation rates measured at Tf = 51°C.

Activation parameters are derived from Arrhenius plots.

A second set of kinetics experiments with the 10-mer and 14-mer peptides examined the dependence of the relaxation rates on the final temperature following a T-jump. The magnitude of the T-jump was kept constant while varying the initial temperature to produce a different final temperature within the range of the melting transition. Folding and unfolding rates were determined using the equilibrium constant at the final temperature. An Arrhenius plot of the folding and unfolding rates versus temperature yielded the activation parameters summarized in Table 3. The limited temperature range of our measurements led to a level of uncertainty in the Arrhenius plots which precluded an accurate determination of ΔS‡.

DISCUSSION

Simple peptide models provide a framework for exploring the fundamental processes of protein folding, including chain collapse and hydrogen bond formation. We have explored these processes in a unique series of cyclic peptides that form β-hairpin structures. Tying the ends of the peptide together dramatically influences the folding behavior compared to linear analogs that form a β-hairpin.

The equilibrium structures and melting behavior of these peptides have been studied using temperature dependent FTIR spectroscopy. At room temperature, all three peptides are strongly folded, having characteristic β-turn and β-sheet components of the amide I′ band (Table 1). These bands are reduced in intensity and a new band corresponding to disordered polypeptide grows in as the temperature is increased. The frequency and bandwidth of the disordered polypeptide band is essentially identical to what we have observed for noncyclic peptides and for proteins (Gilmanshin et al., 1997; Williams et al., 1996). The increase in frequency of the amide I′ mode upon unfolding is consistent with loss of strong intramolecular hydrogen bonding.

A previous study reported minimal temperature-dependent changes for the 10-mer peptide in the far-UV-CD (Jelokhani-Niaraki et al., 2001). The interpretation of the 10-mer result was that no significant conformational changes occurred in the temperature range studied between 5 and 85°C. The problem with this interpretation is that CD spectra of cyclic peptides are not well characterized in general. Furthermore, these cyclic β-hairpin structures have an unusual CD spectrum that more closely resembles that expected for an α-helix than for a β-sheet. Finally, the CD spectrum for unfolded cyclic peptides is not known. Large differences are observed between the CD spectra of β-hairpin forming (6-, 10-, and 14-mer) and non-β-hairpin forming peptides (8-, 12-, and 16-mer) (Gibbs et al., 1998). However, it is unlikely that the unfolded structures of the 6-, 10-, and 14-mer resemble the structures of the 8-, 12-, and 16-mer due to the periodicity dependence of accessible conformations. The cyclic systems obviously cannot access extended conformations that would give the characteristic CD spectrum of a disordered polypeptide. Therefore, it is possible that the CD spectrum of the unfolded 10-mer may closely resemble that of the folded state, accounting for the small changes observed in the temperature dependent CD data. In contrast, the IR data offer definitive proof that the intramolecular H-bonding of the β-hairpin structure is lost with increasing temperature. Furthermore, the amide I′ peak of the unfolded state is characteristic of a disordered polypeptide H-bonded to water. Clearly, changes in the backbone conformation, in addition to loss of the β-hairpin H-bonding, are necessary to accommodate intermolecular interactions with water molecules.

Further insight into the nature of the thermally induced transition is provided by thermodynamic characterization. A van't Hoff analysis reveals a linear dependence of the free energy of folding over a very wide temperature range (1°C to 85°C). Both the stability of the folded structure and the cooperativity of the transition (measured by the transition width) increase along the series. The thermodynamic parameters for folding of the 14-mer (Table 2) are remarkably close to those found previously for the GB1 β-hairpin (ΔH = −48.5 kJ mol−1, ΔS = −163 J mol−1 K−1). The entropy loss of folding of the cyclic peptide is only slightly smaller than that of the noncyclic peptide. This is somewhat surprising given the restriction in conformational entropy imposed by the cyclization of the structure. This result suggests that the entropy change is dominated by side chain rather than the backbone motions.

The T-jump relaxation kinetics observed for the cyclic β-hairpin structures are remarkably fast. All three cyclic peptides exhibit relaxation rates about two orders of magnitude greater than that observed for the β-hairpin of protein G under similar conditions (Muñoz et al., 1997). This rate acceleration occurs in both the folding and unfolding steps, and appears to be a consequence of cyclization. Obviously, the cyclic peptides are constrained to adopt compact structures even in the unfolded state. An estimate of the rate at which a linear polypeptide samples such compact conformations can be obtained from measurements of the rate of contact of the ends of a polypeptide (Lapidus et al., 2000). A flexible peptide of 16 residues is predicted to have an end-to-end contact rate of ∼107 s−1, which provides an upper limit for the rate at which GB1 samples compact conformations. The folding rate of GB1 is much slower (105 s−1), indicating that either the residence times in such conformations are small until specific stabilizing interactions are made, or that collapsed structures are quickly stabilized but with the wrong registry and must rearrange over a barrier to reach the correct fold. In contrast, the structure of the cyclic peptides precludes the collapse process as a rate-limiting step. In addition, the barrier to rearrangement of the compact, unfolded conformations must be small in this case.

An important feature of the folding rates of this series of cyclic peptides is that they are essentially constant with peptide length (Table 3). The unfolding rate, in contrast, shows a clear decrease along the series. These results suggest that the free energies of the unfolded state and the transition state do not change along the series, but rather the free energy of the folded state is decreased, to yield an increasingly stable folded structure, and a decreasing rate of unfolding. The estimated propagation time (i.e., the rate of making or breaking a single H-bond in a nucleated structure) in a β-hairpin is 1 ns−1 (Muñoz et al., 1997). In addition, the disruption of β-sheet H-bonds in response to a T-jump has been reported to occur on a 1–5 ns timescale in ribonuclease A (Phillips et al., 1995). If the macroscopic folding rate were sensitive to this propagation rate, we would expect it to scale with the number of H bonds in the structure, which it does not. On the other hand, if the rate were dominated by the folding of the turn structure, it should remain constant since all three peptides have the same type II′ β-turns. We conclude that the folding rate is dominated by turn formation.

The temperature dependence of the folding rates yields a negative enthalpy of activation of folding for both the 10-mer and 14-mer. Negative activation enthalpies are unusual in chemical reactions because energy is required to partially break covalent bonds in the transition state. Outer-sphere transition metal electron transfer reactions having large negative enthalpies of reaction have been shown to exhibit negative activation enthalpies (Cramer and Meyer, 1974; Marcus and Sutin, 1975). This observation has been rationalized within Marcus electron transfer theory as due to more energetic states of the activated complex in this case (highly negative enthalpy of reaction) being less reactive than the less energetic ones (Marcus and Sutin, 1975). The molecular basis for the observation of negative activation enthalpies in protein folding reactions, however, is less clear. Negative activation enthalpies have been observed in the kinetics of the folding of many proteins, including RnaseA, lysozyme, chymotrypsin inhibitor 2, and barnase (Chen et al., 1989; Hagerman and Baldwin, 1976; Oliveberg et al., 1995). This behavior has been attributed to the difference in heat capacity between the unfolded and transition states (ΔCp‡), due to the formation of native-like hydrophobic interactions in the transition state (Chen et al., 1989; Oliveberg et al., 1995). The free energy of activation of the reaction is temperature dependent because of the change in heat capacity between the ground (unfolded) state and the transition state. It has a minimum value as a function of temperature, at which the folding rate reaches its maximum, then begins to decrease again. Thus, the folding rate exhibits a parabolic dependence on temperature, yielding an apparent negative activation enthalpy at higher temperatures.

Negative activation energies have also been observed for the folding of small peptide models, although the reason for this is less clear than for the protein examples cited above (Lednev et al., 1999; Muñoz et al., 1997; Werner et al., 2002). The characteristic parabolic behavior of the Eyring plot produced by ΔCp‡ is not observed for any of these peptide models, including the cyclic β-hairpin structures in the present study. This is not surprising since the folding of these structures does not involve substantial burial of hydrophobic side chains (with the possible exception of the linear β-hairpin structure studied by Muñoz et al., which also exhibits some curvature in the Arrhenius plot). This implies that the transition state is stabilized by other interactions, such as the formation of intramolecular H-bonds. Our results also imply a substantial entropic barrier to folding, which leads to a positive free energy of activation. The cyclic nature of these peptides restricts the accessible conformations of the polypeptide to relatively compact structures. Consequently, the entropic barrier must arise from limited peptide backbone degrees of freedom, loss of side chain mobility, and changes in solvation of the transition state.

In summary, the cyclic peptides studied in this work provide new insight into the mechanism of β-hairpin formation. The folding rate of these cyclic peptides is significantly accelerated over the rate of a linear peptide that forms a β-hairpin. The folding of the cyclic peptides involves both formation of the turn and the requisite cross-strand interactions. These events occur on the tens-of-ns time scale, two orders of magnitude faster than the linear GB1 system. This observation supports the argument that the rate-limiting step in the linear system is either stabilization of compact collapsed structures or rearrangement of collapsed structures over a barrier to achieve the native intrastrand registry. Lastly, a negative value for the activation energy for folding implies a transition state barrier that is primarily entropic in nature, and therefore corroborates the idea of an organized transition state. While the specific structural origin of these effects is not revealed in these experiments, it is likely due to the presence of stabilizing native cross-strand interactions in the transition state, including hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic contacts.

Acknowledgments

We thank J.H. Werner for helpful discussions, and C. Caramana, J.A. Bailey, and C.T. Buscher for technical assistance.

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (GM 53640) to R.B.D.

References

- Arrondo, J. L. R., F. J. Blanco, L. Serrano, and F. M. Goni. 1996. Infrared evidence of a β-hairpin peptide structure in solution. FEBS Lett. 384:35–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callender, R. H., R. B. Dyer, R. Gilmanshin, and W. H. Woodruff. 1998. Fast events in protein folding: the time evolution of primary processes. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 49:173–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B. L., W. A. Baase, and J. A. Schellman. 1989. Low-temperature unfolding of a mutant of phage-T4 lysozyme.2. Kinetic investigations. Biochemistry. 28:691–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colley, C. S., S. R. Griffiths-Jones, M. W. George, and M. S. Searle. 2000. Do interstrand hydrogen bonds contribute to b-hairpin peptide stability in solution? IR analysis of peptide folding in water. Chemical Communications: 593–594.

-

Cramer, J. L., and T. J. Meyer. 1974. Unusual activation parameters in oxidation of

by polypyridine complexes of iron(III): Evidence for multiple paths for outer-sphere electron-transfer. Inorg. Chem. 13:1250–1252. [Google Scholar]

by polypyridine complexes of iron(III): Evidence for multiple paths for outer-sphere electron-transfer. Inorg. Chem. 13:1250–1252. [Google Scholar] - Dinner, A., T. Lazaridis, and M. Karplus. 1999. Understanding beta-hairpin formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96:9068–9073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer, R. B., F. Gai, W. H. Woodruff, R. Gilmanshin, and R. H. Callender. 1998. Infrared studies of fast events in protein folding. Acc. Chem. Res. 31:709–716. [Google Scholar]

- Eaton, W. A., V. Munoz, P. A. Thompson, E. R. Henry, and J. Hofrichter. 1998. Kinetics and dynamics of loops, alpha-helices, beta-hairpins, and fast-folding proteins. Acc. Chem. Res. 31:745–753. [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa, J. F., and S. H. Gellman. 2000. A designed beta-hairpin containing a natural hydrophobic cluster. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 39 (13):2330–2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Lopez, S., H. S. Kim, E. C. Choi, M. Delgado, J. R. Granja, A. Khasanov, K. Kraehenbuehl, G. Long, D. A. Weinberger, K. M. Wilcoxen, and M. R. Ghadiri. 2001. Antibacterial agents based on the cyclic D,L-alpha-peptide architecture. Nature. 412:452–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, A. C., T. C. Bjorndahl, R. S. Hodges, and D. S. Wishart. 2002. Probing the structural determinants of type II′ beta-turn formation in peptides and proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124:1203–1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, A. C., L. H. Kondejewski, W. Gronwald, A. M. Nip, R. S. Hodges, B. D. Sykes, and D. S. Wishart. 1998. Unusual beta-sheet periodicity in small cyclic peptides. Nat. Struct. Biol. 5:284–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmanshin, R., S. Williams, R. H. Callender, W. H. Woodruff, and R. B. Dyer. 1997. Fast events in protein folding: relaxation dynamics of secondary and tertiary structure in native apomyoglobin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 94:3709–3713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths-Jones, S. R., A. J. Maynard, and M. S. Searle. 1999. Dissecting the stability of a β-hairpin peptide that folds in water. J. Mol. Biol. 292:1051–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagerman, P. J., and R. L. Baldwin. 1976. Quantitative treatment of kinetics of folding transition of ribonuclease-A. Biochemistry. 15:1462–1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jäger, M., H. Nguyen, J. C. Crane, J. W. Kelly, and M. Gruebele. 2001. The folding mechanism of a β-sheet: the WW domain. J. Mol. Biol. 311:373–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelokhani-Niaraki, M., L. H. Kondejewski, S. W. Farmer, R. E. W. Hancock, C. M. Kay, and R. S. Hodges. 2000. Diastereoisomeric analogues of gramicidin S: structure, biological activity and interaction with lipid bilayers. Biochem. J. 349:747–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelokhani-Niaraki, M., E. J. Prenner, L. H. Kondejewski, C. M. Kay, R. N. McElhaney, and R. S. Hodges. 2001. Conformation and other biophysical properties of cyclic antimicrobial peptides in aqueous solutions. J. Pept. Res. 58:293–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimov, D. K., and D. Thirumalai. 2000. Mechanisms and kinetics of beta-hairpin formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 97:2544–2549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondejewski, L. H., D. L. Lee, M. Jelokhani-Niaraki, S. W. Farmer, R. E. W. Hancock, and R. S. Hodges. 2002. Optimization of microbial specificity in cyclic peptides by modulation of hydrophobicity within a defined structural framework. J. Biol. Chem. 277:67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kortemme, T., M. Ramírez-Alvarado, and L. Serrano. 1998. Design of a 20-amino acid, three-stranded β-sheet protein. Science. 281:253–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krantz, B. A., L. B. Moran, A. Kentsis, and T. R. Sosnick. 2000. D/H amide kinetic isotope effects reveal when hydrogen bonds form during protein folding. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7:62–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapidus, L. J., W. A. Eaton, and J. Hofrichter. 2000. Measuring the rate of intramolecular contact formation in polypeptides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 97:7220–7225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lednev, I. K., A. S. Karnoup, M. C. Sparrow, and S. A. Asher. 1999. Alpha-helix peptide folding and unfolding activation barriers: a nanosecond UV resonance raman study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121:8074–8086. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, R. N. A. H., E. J. Prenner, L. H. Kondejewski, C. R. Flach, R. Mendelsohn, R. S. Hodges, and R. N. McElhaney. 1999. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopic studies of the interaction of the antimicrobial peptide gramicidin S with lipid micelles and with lipid monolayer and bilayer membranes. Biochemistry. 38:15193–15203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus, R. A., and N. Sutin. 1975. Electron-transfer reactions with unusual activation parameters. A treatment of reactions accompanied by large entropy decreases. Inorg. Chem. 14:213–216. [Google Scholar]

- McInnes, C., L. H. Kondejewski, R. S. Hodges, and B. D. Sykes. 2000. Development of the structural basis for antimicrobial and hemolytic activities of peptides based on gramicidin S and design of novel analogs using NMR spectroscopy. J. Biol. Chem. 275:14287–14294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz, V., E. Henry, J. Hofrichter, and W. Eaton. 1998. A statistical mechanical model for β-hairpin kinetics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:5872–5879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz, V., P. Thompson, J. Hofrichter, and W. A. Eaton. 1997. Folding dynamics and mechanism of β-hairpin formation. Nature. 390:196–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveberg, M., Y.-J. Tan, and A. R. Fersht. 1995. Negative activation enthalpies in the kinetics of protein folding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 92:8926–8929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pande, V. S., and D. S. Rokhsar. 1999. Molecular dynamics simulations of unfolding and refolding of a beta-hairpin fragment of protein G. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96:9062–9067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, C. M., Y. Mizutani, and R. M. Hochstrasser. 1995. Ultrafast thermally induced unfolding of RNase A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 92:7292–7296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Alvarado, M., T. Kortemme, F. J. Blanco, and L. Serrano. 1999. Beta-hairpin and beta-sheet formation in designed linear peptides. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 7:93–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenck, H. L., and S. H. Gellman. 1998. Use of a designed triple-stranded antiparallel β-sheet to probe β-sheet cooperativity in aqueous solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120:4869–4870. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, C. K., and L. Regan. 1997. Construction and design of β-sheets. Acc. Chem. Res. 30:153–161. [Google Scholar]

- Susi, H., and D. M. Byler. 1986. Resolution enhanced Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy of enzymes. Methods Enzymol. 130:290–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syud, F. A., H. E. Stanger, and S. H. Gellman. 2001. Interstrand side chain–side chain interactions in a designed beta-hairpin: significance of both lateral and diagonal pairings. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123:8667–8677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner, J. H., R. B. Dyer, R. M. Fesinmeyer, and N. H. Andersen. 2002. Dynamics of the primary processes of protein folding: helix nucleation. J. Phys. Chem. B. 106:487–494. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, S., T. P. Causgrove, R. Gilmanshin, K. S. Fang, R. H. Callender, W. H. Woodruff, and R. B. Dyer. 1996. Fast events in protein folding: helix melting and formation in a small peptide. Biochemistry. 35:691–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray, W. O., T. Aida, and R. B. Dyer. 2002. Photoacoustic cavitation and heat transfer effects in the laser-induced temperature jump in water. Appl. Phys. B. 74:57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Zurdo, J., J. I. Guijarro, J. L. Jimenez, H. R. Saibil, and C. M. Dobson. 2001. Dependence on solution conditions of aggregation and amyloid formation by an SH3 domain. J. Mol. Biol. 311:325–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]