Abstract

Electric charge distribution in mRNA 5′ cap terminus has been exhaustively characterized in respect to the affinity for cap-binding proteins. Formation of the stacked configuration of positively charged 7-methylguanine in between two aromatic amino acid rings, known as sandwich cation-π stacking, is thought to be prerequisite for the specific recognition of the cap by eukaryotic initiation factor eIF4E; i.e., discrimination between the cap and nucleotides without the methyl group at N(7). Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy of 15N/13C-double-labeled 7-methylguanosine 5′-triphosphate and 7-methylguanosine, as well as their unsubstituted counterparts, GTP and guanosine, yielded characteristic changes of the electron-mediated spin-spin couplings and chemical shifts due to the methylation at N(7). The experimentally measured changes of the nuclear magnetic resonance parameters have been analyzed in respect to the electric charge distribution calculated by means of quantum chemical methods, and interpreted in terms of new proposed positive charge localization in the 7-methylguanine five-member ring.

INTRODUCTION

All nuclear transcribed mRNAs possess a 5′-terminal cap, m7GpppN, in which 7-methylguanosine is linked by a 5′-to-5′-triphosphate bridge with the first transcribed nucleoside. The cap structure is necessary for optimal mRNA translation (Muthukrishnan et al., 1975; Sonenberg, 1988); it participates in the splicing of mRNA precursors (Konarska et al., 1984; Izaurralde et al., 1994), and affects nuclear export and mRNA stability (Izaurralde et al., 1992). The cap function in translation is mediated by the 25 kDa protein eIF4E (eukaryotic initiation factor 4E), a subunit of the heterotrimeric eIF4F initiation complex (Gingras et al., 1999). The cap is also specifically recognized by other cap-binding proteins like vaccinia virus methyltransferase VP39 (Hu et al., 1999) and the CBC80/20 nuclear cap-binding complex (Mazza et al., 2002).

Three-dimensional structures of murine eIF4E and its yeast homolog, both complexed with 7-methyl-guanosinediphosphate (m7GDP), have been solved by x-ray crystallography (Marcotrigiano et al., 1997) and by solution nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy (Matsuo et al., 1997), respectively. The crystal structures of m7GTP- and m7GpppA-bound human eIF4E (Tomoo et al., 2002) and m7GpppG-bound murine eIF4E (Niedzwiecka et al., 2002) have also been determined recently. The eIF4E protein is shaped like a cupped hand, with the cap analog located in a narrow slot on the concave surface. The 7-methylguanine moiety is stabilized by base sandwich stacking between Trp56 and Trp102, and formation of three Watson-Crick-like hydrogen bonds with a side-chain carboxylate of Glu103, a backbone NH of Trp102, and a van der Waals contact of the N(7)-methyl group with Trp166. The phosphate chain forms salt bridges and direct or water-mediated hydrogen bonds with the NH of tryptophan 166 indole rings as well as positively charged lysines and arginines. Similarly, in the VP39 complex (Hu et al., 1999; Mazza et al., 2002) the most striking interaction is the intimate cation-π stacking between the sandwiched 7-methylguanine and two side chains of Tyr22 and Phe180. In the crystal structure of CBC with m7GpppG (Mazza et al., 2002), a similar type of binding of 7-methylguanine has been found—i.e., the stacking in between the Tyr20 and Tyr43 aromatic rings.

Whereas the structure determinations provided detailed information on the mode of cap binding, the consistent physical description of the cap-protein interactions has not been proposed yet. The molecular charge distribution is necessary to address electrostatic forces in cation-π interactions (Dougherty, 1996), which are widespread in proteins (for review see, e.g., Gallivan and Dougherty, 1999). They are also of primary importance for the formation (Blachut-Okrasinska et al., 2000) and stability (Niedzwiecka et al., 2002) of the eIF4E-cap complexes; hence the mechanistic basis of the molecular recognition in translation initiation in eukaryotes. This prompted us to perform systematic NMR measurements and theoretical calculations of the electron-mediated spin-spin couplings and chemical shifts in 15N/13C-double labeled 7-methyl-GTP, 7-methylguanosine, and their nonmethylated counterparts (Fig. 1). The NMR parameters are sensitive markers of the molecular charge density changes upon chemical substitution in organic molecules (Harris, 1983). In this article we focus our attention on variation of the electric charge distribution due to introduction of a methyl group at N(7) of guanine with the aim to elucidate the role of electrostatics in interactions between eIF4E and mRNA 5′ cap. Although no simple correlation occurs between the experimentally determined NMR parameters and the theoretically calculated atomic charges, the proposed approach allows a verification of the theoretically calculated charge distributions and a deeper insight into the effects of the guanine methylation on the interactions in the eIF4E cap-binding center. Moreover, a large set of experimentally measured and theoretically verified couplings for the guanine and 7-methylguanine moieties is very valuable for NMR analyses, considering the scarcity of such a data set (Hilbers and Wijmenga, 1996).

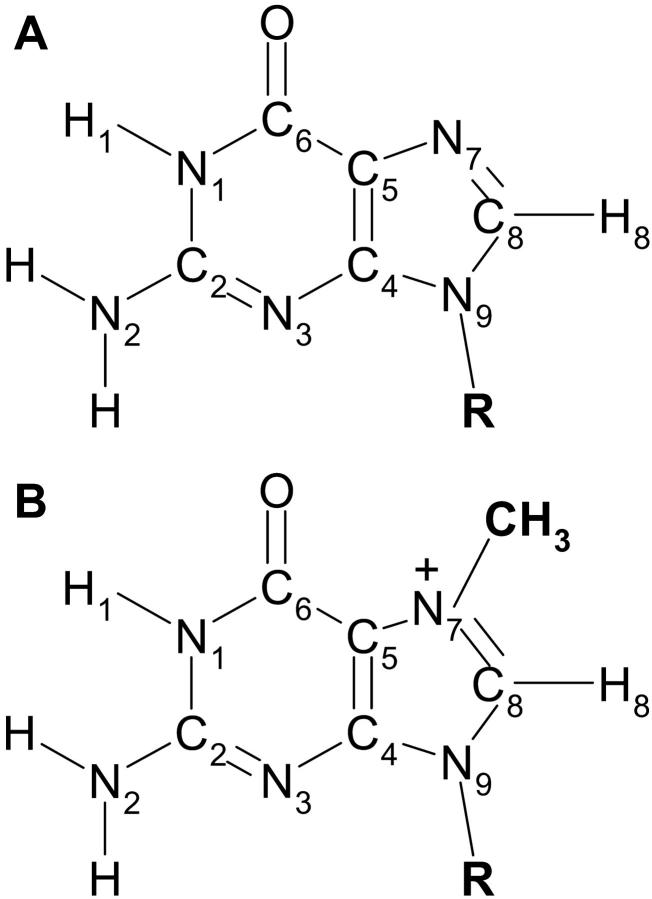

FIGURE 1.

(A) GTP (R = ribose-5′-triphosphate), guanosine (R = ribose), and 9-methylguanine (R = CH3). (B) The corresponding 7-methyl derivatives (cap analogs), with the marked localization of the additional positive charge.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

15N/13C-double-labeled GTP was purchased from Martek Bioscience (Stable Isotope Group, Columbia, MD). Synthesis of labeled 7-methyl-GTP was performed by methylation of 15N/13C double-labeled GTP with CH3I and the product was purified by ion exchange chromatography on DEAE-Sephadex (A-25, HCO3− form) using a linear gradient of triethylammonium bicarbonate (pH 7.5), as described previously for the nonlabeled cap analogs (Darzynkiewicz et al., 1987).

15N/13C-double-labeled guanosine and 7-methylguanosine were obtained from the corresponding triphosphates by enzymatic dephosphorylation as follows: 1 ml 0.5 M Tris-HCl pH 9 and 1 μl of E. coli alkaline phosphatase (47 units/mg, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) were added to 0.7 ml solution of GTP and incubated at 37°C for 12 h. The mixture was analyzed on TLC (silica gel 60 F254, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and by HPLC (Nova-Pack C18 4 μm, 4.6 × 250 mm column, Waters, Vienna, Austria). The product was separated on 20 × 20 cm silica gel PF254 plates (Merck) using a mixture of 2-propanol and water (7:3), and eluted with a mixture of methanol and water (2:1). 7-methylguanosine was obtained similarly using 2 μl of the alkaline phosphatase, and without the addition of Tris-HCl.

1H-, 13C-, and 15N-NMR spectra were run on Varian UNITYplus 500 MHz (Palo Alto, CA) and Bruker AM 500 MHz (Karlsruhe, Germany) spectrometers at 25°C and 15 mM concentration in water at pH 6.2 (10% D2O for locking) or in DMSO-d6, for the nucleotides, m7GTP and GTP, or the nucleosides, m7G and G, respectively. The low pH ensures >90% preference of the cationic form of the 7-methylguanine base, pK ∼7.2–7.5 (Wieczorek et al., 1995), which is required by eIF4E (Marcotrigiano et al., 1997; Niedzwiecka et al., 2002). The 13C chemical shifts were assigned on the basis of the assignments previously made for guanosine measured in DMSO (Kalinowski et al., 1994). Similarly, the 15N chemical shifts were assigned by analogy to those reported for guanosine measured in DMSO (Buchanan and Stothers, 1982) and 3′-GMP measured in H2O (Kyogoku et al., 1982).

The electron-mediated spin-spin couplings were determined from the NMR resonances by means of the STSIT simulation program (S. Szymanski, unpublished program). The STSIT program involves a nonlinear, least-squares fit of the relevant spectral parameters to the experimental line shape, under assumption that all of the spectral lines are Lorentzians and of the same width. It is equivalent to the program DAVINS by D. Stephenson and G. Binsch (distributed once by the Quantum Chemistry Programs Exchange). Its unique feature is that, in the realization of the Newton-Rawson minimization scheme, the derivatives of the line-shape function versus the optimized parameters are calculated analytically from the corresponding matrix expressions. The fitting was based on mutual accordance of a maximal number of the common couplings extracted from different resonance signals, and referring to the theoretically calculated values (see below) in ambiguous cases.

Theoretical calculations of the electric charges and bond orders for Gua and m7Gua (crystallographic and minimized structures) were performed by the Gaussian94 program (Gaussian Inc., Pittsburgh, PA, 1995) using the DFT method at the RB3LYP/6-31G(d,p) level. The AIM(BO) module of Gaussian94 was applied to calculate the bond orders n, according to Bader et al. (1983): n = exp[A(ρ − B)], where ρ is the charge density in critical points on the attractor interaction lines, and the parameters A and B were obtained by fitting the Bader's equation to the simple model molecules of the known bond orders.

The program deMon developed by Malkin et al. (1994), based on the DFT method, was used to calculate the couplings across n bonds, nJ, and shielding constants, σ, for Gua and m7Gua. The calculations were performed using the correlation functional of Perdew (1986) and the semilocal exchange of Perdew and Wang (1986). The IGLO-III basis set of Kutzelnigg et al. (1991) and a fine grid with 64 radial points were employed. The value of 0.001 was used as the perturbation parameter. In the methodology applied, three contributions to the coupling mechanism are taken into account: the Fermi contact, the paramagnetic spin-orbit, and the diamagnetic spin-orbit terms, whereas the spin-dipolar contribution was neglected. The Fermi contact and the paramagnetic spin-orbit contributions were calculated with the finite perturbation theory and the sum-over-states density functional perturbation theory, respectively, and the diamagnetic spin-orbit term was obtained by numerical integration. The molecular geometry optimization was carried out by the program DMOL (Accelrys, San Diego, CA) before the couplings calculations.

The stacking energies between 7-methylguanosine or guanosine and indole rings of two tryptophans were estimated using a simple Coulombic interaction model,  where rjk is the separation of the partial atomic charges qj, qk in the interacting molecules, according to the geometry known from crystallography (Marcotrigiano et al., 1997), and k is a scaling factor to get the energy in kJ/mol.

where rjk is the separation of the partial atomic charges qj, qk in the interacting molecules, according to the geometry known from crystallography (Marcotrigiano et al., 1997), and k is a scaling factor to get the energy in kJ/mol.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Couplings in the guanine and 7-methylguanine rings

NMR measurements of 15N/13C-double-labeled cap analogs give a unique opportunity to get a large number of the spin-spin couplings in the 7-methylguanine ring and compare them with those of the nonmethylated guanine. However, the complicated splitting patterns of the individual 13C and 15N resonance lines in m7GTP and GTP made it difficult to extract the individual couplings, except for most of the largest couplings through one bond 1J. Accordingly, we compared and reconciled the couplings deduced from the simulation of the resonance multiplets using the STSIT program with those calculated by means of the deMon program based on the DFT quantum method (see Materials and Methods).

The assignment of the values extracted by a fitting procedure from the NMR multiplets to the suitable couplings has been done on the basis of the expected ranges of their values and the mutual accordance of the same couplings derived from the NMR signals of different nuclei. An example of fitting the GTP C(6) signal using trial values of the couplings is shown in Fig. 2. Satisfactory agreement between unambiguously assigned experimental couplings and the theoretically calculated ones (Table 1) supports the use of the theoretical values in those cases in which the assignment from the experiment alone was not feasible. Moreover, the quantum calculations provided the signs of the couplings which are difficult to measure experimentally. It is crucial for comparison (subtraction) of the two values, one of the parent and the other of the methylated guanine, if the coupling value changes its sign after the methylation. The couplings have been calculated for the guanine bases substituted at N(9) with the methyl group, because the deMon program allows calculations of the molecules of a limited size only. However, according to the experimental data (see Table 1), dephosphorylation of GTP does not have significant influence on the coupling values.

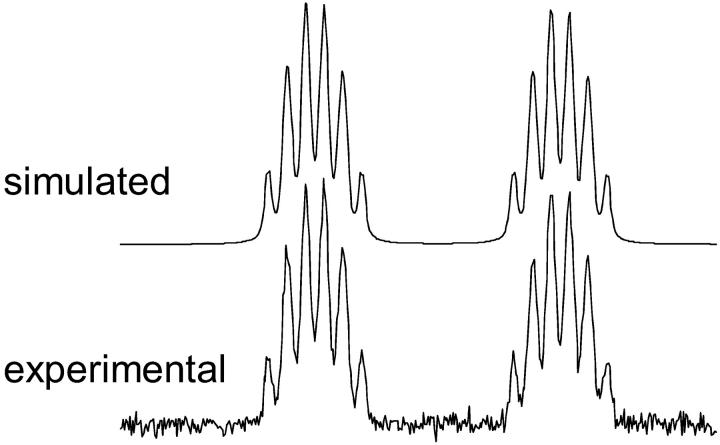

FIGURE 2.

C(6) Carbon multiplet of GTP. (Top) Simulated with Prof. Szymanski's program. Coupling values used for simulation: 1JC5C6 = 87.9 Hz; 1JC6N1 = 5.9 Hz; 2JC4C6 = 12.9 Hz; 2JC6N7 = 7.9 Hz; 3JC6C8 = 6.8 Hz; and 3JC6N9 = 1.3 Hz, linewidth 0.8 Hz. (Bottom) Experimental.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of the selected values of the DFT calculated couplings [Hz] for m7Gua and Gua with those measured experimentally for the corresponding nucleoside triphosphates, m7GTP and GTP

| DFT calculated

|

Measured

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m7Gua

|

Gua

|

m7GTP*

|

GTP*

|

Guanosine†

|

|||||||

| 1J | (1K) | 1J | (1K) | 1J | (1K) | 1J | (1K) | 1J | (1K) | ||

| H(8)C(8) | 218.2 | (72.2) | 210.0 | (69.5) | 225.4 | (74.5) | 216.3 | (71.4) | 213.2 | (70.5) | |

| H(2)N(2) | −95.2 | (78.2) | −93.3 | (76.6) | −89.2 | (73.2) | −90.1 | (74.0) | −89.5 | (73.5) | |

| −93.6 | (76.9) | −91.7 | (75.3) | ||||||||

| C(4)C(5) | 62.6 | (82.3) | 57.6 | (75.8) | 68.4 | (90.0) | 63.5 | (83.5) | 62.1 | (81.7) | |

| C(4)N(9) | −14.9 | (48.6) | −19.8 | (64.6) | −16.9 | (55.2) | −19.2 | (62.7) | −19.6 | (64.0) | |

| C(5)C(6) | 91.6 | (120.5) | 96.6 | (127.1) | 87.6 | (115.2) | 87.9 | (115.6) | 85.4 | (112.4) | |

| C(5)N(7) | −12.8 | (41.8) | 6.8 | (−22.2) | −7.4 | (24.1) | 4.1 | (-13.4) | ‡ | ||

| C(6)N(1) | −7.6 | (24.8) | −2.0 | (6.6) | −13.6 | (44.4) | −5.9 | (19.2) | ‡ | ||

| C(8)N(9) | −15.6 | (50.9) | −5.9 | (19.2) | −18.4 | (60.1) | ‡ | −3.3 | (10.8) | ||

| C(8)N(7) | −15.4 | (50.2) | 8.7 | (−28.4) | ‡ | ‡ | ‡ | ||||

Values of the reduced couplings K × 1019 [T2/J] are given in parentheses.

In H2O, pH 6.2 25°C, the signs assigned after the calculated values.

In DMSO, the signs assigned after the calculated values.

Impossible to extract from the spectra; loss of the signal splitting due to a coincidental overlapping of a large number of the multiplet lines.

A few comments should be made on the 1JCC and 1JCN coupling magnitudes. The first and most important observation concerns the mechanism governing the couplings across the bonds of the C-C and C-N type. The former is dominated by the Fermi contact contribution, whereas in the case of the latter the spin-dipolar and spin-orbit terms also play an important role. The 1JCC couplings in guanine and 7-methylguanine are ∼65 Hz across the double C(4)=C(5) bond, and ∼90 Hz across the formally single bond, C(5)-C(6). For a comparison, the 1JCC couplings for enaminoester, (C2H5)2NCH=CHC(O)OCH3, are 72.8 Hz for the C=C double bond and 82.5 Hz for the C-C(O) single bond (Krivdin et al., 1989). Thus, in the case of both types of compounds, quite a substantial decrease of the couplings across the double bond occurs as opposed to 1JC=C = 79.2 Hz in enamine, (C2H5)2NCH=CHC2H5 (Krivdin et al., 1989). The result clearly indicates that a strong delocalization of the electrons of the double bond toward the carbonyl group takes place. It is worth noting that 1JCC in ethylene is 68.6 Hz and increases significantly upon substitution of the double bond with electronegative substituents (Kamienska-Trela, 1995). An analysis of the couplings across two and three bonds (data not shown) provides an additional support to the conclusions drawn on the basis of the one-bond couplings. All long-range couplings calculated for the six-membered rings of guanine and its methylated counterpart are very similar. This is at variance with the couplings observed in the five-membered rings, which increase significantly (in absolute terms) upon the methylation at N(7). The only exceptions are the 2JC4C6 and 2JC4C8, which are 2× smaller in m7Gua than those in Gua.

The effect of methylation on the chemical shifts and couplings

The reduced couplings  (Table 1) represent the electronic contribution irrespective of the nuclear magnetogyric ratios γA, γB, and are thus isotope-independent. The values of chemical shifts reflect shielding of the nuclei by the electrons and, like those of the reduced couplings, they depend on electric charge distribution in the investigated molecule. For completion of the experimentally-based insight into changes of the electric charge due to the guanine methylation, we have analyzed the 13C- and 15N-chemical shifts and the reduced couplings across one bond.

(Table 1) represent the electronic contribution irrespective of the nuclear magnetogyric ratios γA, γB, and are thus isotope-independent. The values of chemical shifts reflect shielding of the nuclei by the electrons and, like those of the reduced couplings, they depend on electric charge distribution in the investigated molecule. For completion of the experimentally-based insight into changes of the electric charge due to the guanine methylation, we have analyzed the 13C- and 15N-chemical shifts and the reduced couplings across one bond.

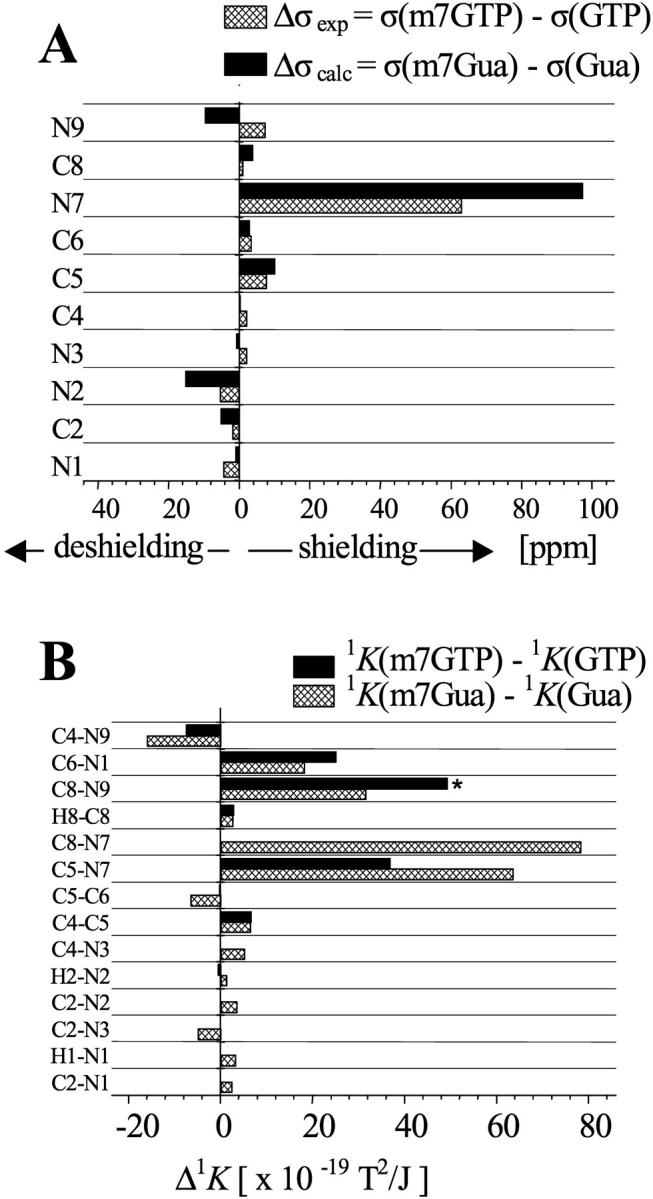

Methylation at N(7) of the guanine ring introduces additional +1 charge, which was commonly thought to be delocalized through N(7), C(8), and N(9). This view was intuitively supported by well-known phenomena: H(8) exchange in aqueous solution of guanine nucleosides and nucleotides bearing a substituent at N(7), and a reduced stability of the cap analogs in alkali. The alkaline decomposition proceeds by opening of the imidazole ring followed by cleavage of the glycosidic bond (Darzynkiewicz et al., 1990). An analysis of the changes of the chemical shifts (Fig. 3 A) and couplings (Fig. 3 B) of the base nuclei resulting from the methylation provides evidence that the positive charge is concentrated almost entirely at N(7).

FIGURE 3.

Changes of the NMR parameters due to the methylation at N(7) of guanine. (A) Differences of 13C- and 15N-experimental chemical shifts in ppm, Δσexp = −Δδ = −(δ(m7GTP)-δ(GTP)), and calculated shielding constants, Δσcalc = σ(m7Gua) − σ(Gua). (B) Differences of one-bond reduced couplings 1K × 1019 [T2/J]. Experimental, Δ1K = 1K(m7GTP)-1K(GTP). Theoretical, Δ1K = 1K(m7Gua)-1K(Gua). The Δ1K value across the C(8)-N(9) bond (asterisk) was derived by subtraction of the 1K of m7GTP from that of guanosine.

The experimental (Δσexp) and calculated (Δσcalc) increase of the shielding is the most pronounced for N(7), 63 ppm, and 97 ppm, respectively (see Fig. 3 A). It is worth noting that the typical α-effect of the methyl group on the N-shielding is of a few ppm only (Witanowski et al., 1986). The shielding by an order-of-one-magnitude smaller than that observed for N(7) is observed for C(5) and N(9). The influence on the remaining nuclei is still less pronounced, some of them being slightly deshielded—i.e., N(1), N(2), and C(2). In particular, the change in Δσ, both experimental and calculated, found for C(8) is nonsignificant.

Among the 1J (1K) couplings the 1JC5N7 and 1JC8N7 (1KC5N7 and 1KC8N7) couplings are the most significantly affected by the methylation. Their absolute values increase roughly 2× and the signs change. A similar increase is observed for 1KC8N9 and 1KC6N1 but their signs do not change. The other couplings are substantially less influenced; in particular, the coupling across C(8)-H(8) exhibits only small, ∼4%, increase upon introduction of the methyl group at the neighboring nitrogen atom. This indicates that the acidity of H(8) is similar in m7G and G, and the mechanism of the proton exchange in the aqueous solvent is therefore not straightforward. The exchange probably occurs via hydration of the N(7)=C(8) bound after a nucleophilic attack at N(7) and temporal opening of the imidazole ring. However, the opening does not lead to decomposition of the base, and only at pH > 7.5 does it become permanent and further lead to disruption of the N(9)-C(1′) bond (Darzynkiewicz et al., 1990).

Thus, we would like to emphasize once again that the above observations strongly indicate that the charge is concentrated mainly on the N(7) atom, which is at variance with the generally accepted structure where the positive charge was strongly delocalized among N(7), C(8), and N(9).

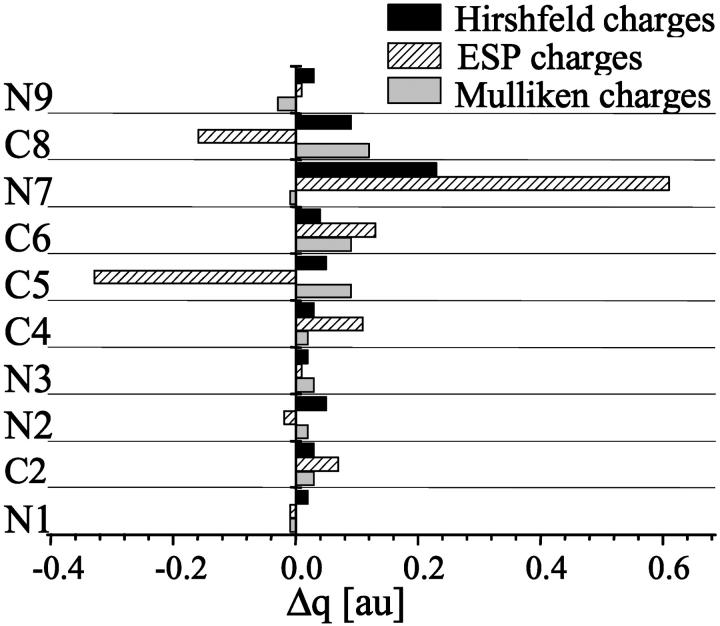

NMR parameters versus atomic charges

There are several ways to define partial atomic charges in the molecule. The most commonly used are the Mulliken (1955), ESP (Chirlian and Francl, 1987), and Hirshfeld (1977) charges. Charged molecules like m7GTP and GTP are “inconvenient” for quantum calculations of the molecular charge distribution due to convergence problems. Therefore we restricted our calculations to the 9-methyl derivatives of guanine and 7-methylguanine, seeing that the negative charge in the triphosphate chain does not exert an influence on the charge distribution in the base (see above). A juxtaposition of the ESP, Mulliken, and Hirshfeld charges in 7-methylated guanine and its nonmethylated counterpart is shown in Fig. 4. The striking difference is observed between distributions of the Mulliken and ESP additional positive charge due to the methyl substitution. The former is uniformly spread throughout the whole base whereas the latter is concentrated at N(7), with a concomitant increase of the negative charge at the neighboring C(5) and C(8). The distribution of the Hirshfeld charge has a uniform character like Mulliken's but with some enhancement of the positive charge at N(7). Summing up, the changes of the NMR parameters due to the methylation of the guanine ring are reflected rather by the changes of the molecular charge distribution as described in the ESP approximation.

FIGURE 4.

Changes of the atomic charges Δq = q(m7Gua) − q(Gua), ESP (Chirlian and Francl, 1987), Mulliken (1955), and Hirshfeld (1977), due to the methylation at N(7) of guanine.

The analysis of the bond orders (data not shown) points to a decrease of the double-bond character of C(8)-N(7) on the methylation by ∼0.25. The bond order of C(5)-N(7) also decreases by ∼0.15, whereas that of C(8)-N(9) increases by ∼0.2. The changes of the other bond orders, positive and negative, are <0.1. No correlation is observed between the bond orders and the 1J coupling changes.

The influence of guanine methylation on the stacking in eIF4E binding center

A large positive charge localized at the N(7) of 7-methylguanine is prerequisite for the binding of the cap to eIF4E (Marcotrigiano et al., 1997; Niedzwiecka et al., 2002) due to increase of its stacking strength with two tryptophan aromatic rings. Cation-π stacking possesses substantial electrostatic contributions (Mecozzi et al., 1996), so we applied a simple Coulombic model of intermolecular interaction to assess the influence of the guanine methylation on the energy of the eIF4E-cap association. The energies of the two complexes have been calculated (see Materials and Methods), one with 7-methylguanine between two indole rings and the other with guanine between two indole rings. In both cases, the same molecular geometry, taken from the eIF4E-m7GDP crystal structure (Marcotrigiano et al., 1997), has been applied. The calculated energy difference of the two complexes, ΔE ∼ 25 kJ/mol, using ESP and Mulliken partial atomic charges, is of the order of the free energy difference ΔG derived from the fluorescence titration experiments (Niedzwiecka et al., 2002). A larger discrepancy between the calculated ΔE and the experimental ΔG values was found for the Hirshfeld atomic charges. Thus, the discrimination between 7-methylguanine cap analogs and their nonmethylated counterparts (Niedzwiecka et al., 2002) seems to arise mainly from the differences in the stacking, bearing in mind that the interaction pattern in the real cap-eIF4E complex is much more complicated than in the model. However, the Watson-Crick-type hydrogen bonds between the guanine base of the cap and Glu102/Trp102 as well as the salt bridges and hydrogen bonds between the cap phosphate chain and the protein arginines and lysines can be formed irrespective of the presence of the methyl substituent at N(7). Specific discrimination between 7-methylguanine and guanine nucleotides by the cap binding proteins is due almost entirely to a positive charge located at N(7).

CONCLUSION

The introduction of the methyl group at the N(7) of the guanine moiety produces an increase of its stacking energy in the complexes with the tryptophan indole rings. The resultant positive charge, localized mainly at N(7) of the 7-methylguanine base, is crucial for the enhancement of the stacking in the cap-binding center of the protein. In the eIF4E-cap complexes the biological importance of methylation of guanosine is due to cooperativity of the cation-π stacking and hydrogen bonding. The enhanced stacking between the cationic m7G and the aromatic Trp side chains is necessary to stabilize effectively the base moiety, and this in turn is a precondition for the formation of three hydrogen bonds inside the cap-binding slot (Niedzwiecka et al., 2002). Strong sandwich stacking of the 7-methylated guanine ring with two parallel aromatic amino-acid side chains seems to be a general mode of the mRNA 5′ cap-specific recognition by various proteins. In addition to eIF4E, the same mechanism is observed for VP39 (Hu et al., 1999) where Tyr22 and Phe180 play a dominant role, and for the CBC80/20 protein complex (Mazza et al., 2002), where two tyrosine rings are engaged in the stacking, although VP39, CBC, and eIF4E do not share any common phylogenetical ancestor.

Our proposition of the positive charge localization in the 7-methylguanine ring leads to a closer analogy between the cation-π stacking of two aromatic rings and the interaction, common in protein structures, between an aromatic ring of one amino acid and a positively charged (lysine, arginine) side chain of the other (Gallivan and Dougherty, 1999), also sometimes termed cation-π stacking. However, a complete, quantitative description of the intermolecular cation-π interactions requires a quantum analysis of the highest occupied molecular orbital of the donor and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital of the acceptor, as well as contribution of hydrophobic and van der Waals forces (Dougherty, 1996; Gallivan and Dougherty, 1999; Mecozzi et al., 1996). The electrostatic interactions are thought to be dominated by the attraction between the positive charge and the quadruple moment of the aromatic ring as well as induction and dispersion forces. We are fully aware that interpretation of the physically complex interaction in terms of the Coulombic forces is a far-reaching simplification, which must be complemented by rigorous quantum analysis. Nevertheless, such an approach can give rise to valuable biophysical description of large eIF4E-cap complexes as a necessary counterpart to high-resolution structural (Marcotrigiano et al., 1997; Matsuo et al., 1997; Tomoo et al., 2002; Niedzwiecka et al., 2002) and dynamic (Blachut-Okrasinska et al., 2000) studies. This in turn can lead to a rational design of inhibitory cap analogs, bearing in mind the evidence implicating the role of eIF4E in malignancy and apoptosis (Gingras et al., 1999).

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Prof. J. Kusmierek for his assistance in enzymatic dephosphorylation of m7GTP and GTP. The authors thank Prof. S. Szymanski for his kind permission to use his unpublished simulation program, STSIT. The NMR spectra were run in the Laboratory of Nuclear Magnetic Resonance, Institute of Biochemistry and Biophysics, Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw. Quantum chemical calculations were performed in the Interdisciplinary Center for Mathematical and Computational Modeling, Warsaw University.

This work was supported by the State Committee for Scientific Research grants KBN 3 T09A 007 19, PBZ-KBN 059/T09/10, KBN 6 P04A 055 17, KBN 3 P04A 021 25, and BW-1565/BF.

Abbreviations used: Gua, 9-methylguanine; m7Gua, 7,9-dimethyguanine; G, guanosine; m7G, 7-methylguanosine; m7GTP, 7-methylguanosine 5′-triphosphate; eIF4E, eukaryotic initiation factor 4E; VP39, 39 kDa vaccinia methyltransferase; CBC, 80/20 kDa nuclear cap binding complex; DFT, density functional theory.

References

- Bader, R. F. W., T. S. Slee, D. Cremer, and E. Kraka. 1983. Description of conjugation and hyperconjugation in terms of electron distributions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 105:5061–5068. [Google Scholar]

- Blachut-Okrasinska, E., E. Bojarska, A. Niedzwiecka, L. Chlebicka, E. Darzynkiewicz, R. Stolarski, J. Stepinski, and J. M. Antosiewicz. 2000. Stopped-flow and Brownian dynamics studies of electrostatic effects in the kinetics of binding of 7-methyl-GpppG to the protein eIF4E. Eur. Biophys. J. 29:487–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan, G. W., and J. B. Stothers. 1982. Diamagnetic metal ion-nucleoside interactions in solution as studied by 15N nuclear magnetic resonance. Can. J. Chem. 60:787–791. [Google Scholar]

- Chirlian, L. E., and M. M. Francl. 1987. Atomic charges derived from electrostatic potentials—a detailed study. J. Comput. Chem. 8:894–905. [Google Scholar]

- Darzynkiewicz, E., I. Ekiel, P. Lassota, and S. M. Tahara. 1987. Inhibition of eukaryotic translation by analogues of messenger RNA 5′-cap: chemical and biological consequences of 5′-phosphate modifications of 7-methylguanosine 5′-monophosphate. Biochemistry. 26:4372–4380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darzynkiewicz, E., J. Stepinski, S. M. Tahara, R. Stolarski, I. Ekiel, D. Haber, K. Neuvonen, P. Lehikoinen, I. Labadi, and H. Lonnberg. 1990. Synthesis, conformation and hydrolytic stability of P1,P3-dinucleotide triphosphates related to mRNA 5′-cap, and comparative kinetic studies of their nucleoside and nucleoside monophosphate analogs. Nucleosides Nucleotides. 9:599–618. [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty, D. A. 1996. Cation-π interactions in chemistry and biology: a new view of benzene, Phe, Tyr, and Trp. Science. 271:163–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallivan, J. P., and D. A. Dougherty. 1999. Cation-π interactions in structural biology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96:9459–9464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gingras, A.-C., B. Raught, and N. Sonenberg. 1999. eIF4 initiation factors: effectors of mRNA recruitment to ribosomes and regulators of translation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 68:913–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris, R. K. 1983. A physicochemical view. In Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. Pitman Books, London, UK. 183–227.

- Hilbers, W. C., and S. S. Wijmenga. 1996. Nucleic acids: spectra, structures, and dynamics. In Encyclopedia of Nuclear Magnetic Resonance, Vol. 5. D. M. Grant and R. K. Harris, editors. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, UK. 3346–3359.

- Hirshfeld, F. L. 1977. Spatial partitioning of charge density. Isr. J. Chem. 16:198–201. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, G., P. D. Gershon, A. E. Hodel, and F. A. Quiocho. 1999. mRNA cap recognition: dominant role of enhanced stacking interactions between methylated bases and protein aromatic side chains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96:7149–7154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izaurralde, E., J. Lewis, C. McGuigan, M. Jankowska, E. Darzynkiewicz, and I. W. Mattaj. 1994. A nuclear cap binding protein complex involved in pre-mRNA splicing. Cell. 78:657–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izaurralde, E., J. Stepinski, E. Darzynkiewicz, and I. W. Mattaj. 1992. A cap binding protein that may mediate nuclear export of RNA polymerase II-transcribed RNAs. J. Cell Biol. 118:1287–1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalinowski, H.-O., S. Berger, and S. Braun. 1994. Carbon-13 NMR Spectroscopy. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, UK. 440.

- Kamienska-Trela, K. 1995. Unsubstituted hydrocarbons in one-bond 13C-13C spin-spin coupling constants. Ann. Rep. NMR Spectr. 30:131–230. [Google Scholar]

- Konarska, M. M., R. A. Padget, and P. A. Sharp. 1984. Recognition of cap structure in splicing in vitro of mRNA precursors. Cell. 38:731–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krivdin, L. B., I. G. Ostroumov, A. G. Projdakov, I. A. Maretina, V. V. Shcherbakov, and G. A. Kalabin. 1989. Constanty spin-spinovogo vzaimodejstvia 13C-13C v structurnych issledovanijach. Zhurnal Organicheskoy Khimi. 25:698–704. [Google Scholar]

- Kutzelnigg, W., U. Fleischer, and M. Schindler. 1991. The IGLO-Method: ab-initio calculation and interpretation of NMR chemical shifts and magnetic susceptibilities. In NMR-Basic Principles and Progress. 1st ed. Vol. 23. P. Diehl, E. Fluck, H. Günther, R. Kosfeld, and J. Seelig, editors. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany. 165–262.

- Kyogoku, Y., M. Watanabe, M. Kainosho, and T. Oshima. 1982. A 15N-NMR study on ribonuclease T1-guanylic acid complex. J. Biochem. 91:675–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malkin, V. G., O. L. Malkina, and D. R. Salahub. 1994. Calculation of spin-spin coupling constants using density functional theory. Chem. Phys. Lett. 221:91–99. [Google Scholar]

- Marcotrigiano, J., A.-C. Gingras, N. Sonenberg, and S. K. Burley. 1997. Co-crystal structure of the messenger RNA 5′ cap-binding protein (eIF4E) bound to 7-methyl-GDP. Cell. 89:951–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo, H., H. Li, A. M. McGuire, C. M. Fletcher, A.-C. Gingras, N. Sonenberg, and G. Wagner. 1997. Structure of translation factor eIF4E bound to m7GDP and interaction with 4E-binding protein. Nat. Struct. Biol. 4:717–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazza, C., A. Segref, I. W. Mattaj, and S. Cusack. 2002. Large-scale induced fit recognition of an m7GpppG cap analogue by the human nuclear cap-binding complex. EMBO J. 21:5548–5557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mecozzi, S., A. P. West, Jr., and D. A. Dougherty. 1996. Cation-π interactions in aromatics of biological and medicinal interest: electrostatic potential surfaces as a useful qualitative guide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 93:10566–10571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulliken, R. S. 1955. Electronic population analysis on LCAO-MO molecular wave functions. J. Chem. Phys. 23:1833–1840. [Google Scholar]

- Muthukrishnan, S., G. W. Both, Y. Furuichi, and A. J. Shatkin. 1975. 5′-Terminal 7-methylguanosine in eukaryotic mRNA is required for translation. Nature. 255:33–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niedzwiecka, A., J. Marcotrigiano, J. Stepinski, M. Jankowska-Anyszka, A. Wyslouch-Cieszynska, M. Dadlez, A.-C. Gingras, P. Mak, E. Darzynkiewicz, N. Sonenberg, S. K. Burley, and R. Stolarski. 2002. Biophysical studies of eIF4E cap-binding protein: recognition of mRNA 5′ cap structure and synthetic fragments of eIF4G and 4E–BP1 proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 319:615–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perdew, J. P. 1986. Density-functional approximation for correlation energy of the inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys. Rev. B. 33:8822–8824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perdew, J. P. 1986. Erratum: Density-functional approximation for correlation energy of the inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys. Rev. B. 34:7406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perdew, J. P., and Y. Wang. 1986. Accurate and simple density functional for the electronic exchange energy: generalized gradient approximation. Phys. Rev. B. 33:8800–8802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonenberg, N. 1988. Cap-binding proteins of eukaryotic messenger RNA: functions in initiation and control of translation. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 35:173–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomoo, K., X. Shen, K. Okabe, Y. Nozoe, S. Fukuhara, S. Morino, T. Ishida, T. Taniguhi, H. Hasegawa, A. Terashima, M. Sasaki, Y. Katsuya, K. Kitamura, H. Miyoshi, M. Ishikawa, and K. Miura. 2002. Crystal structures of 7-methylguanosine 5′-triphosphate (m7GTP)- and P(1)-7-methylguanosine-P3-adenosine-5′,5′-triphosphate (m7GpppA)-bound human full-length eukaryotic initiation factor 4E: biological importance of the C-terminal flexible region. Biochem. J. 362:539–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieczorek, Z., J. Stepinski, M. Jankowska, and H. Lonnberg. 1995. Fluorescence and absorption spectroscopic properties of RNA 5′-cap analogues derived from 7-methyl-, N2,7-dimethyl-, and N2,N2,7-trimethyl-guanosines. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B. 28:57–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witanowski, M., L. Stefaniak, and G. A. Webb. 1986. Nitrogen NMR spectroscopy. In Annual Reports on NMR Spectroscopy, Vol. 18. G. A. Webb, editor. Academic Press, London, UK. 225.