Abstract

Time-resolved resonance Raman spectroscopy is used to obtain chromophore vibrational spectra of the pR, pB′, and pB intermediates during the photocycle of photoactive yellow protein. In the pR spectrum, the C8–C9 stretching mode at 998 cm−1 is ∼60 cm−1 lower than in the dark state, and the combination of C–O stretching and C7H=C8H bending at 1283 cm−1 is insensitive to D2O substitution. These results indicate that pR has a deprotonated, cis chromophore structure and that the hydrogen bonding to the chromophore phenolate oxygen is preserved and strengthened in the early photoproduct. However, the intense C7H=C8H hydrogen out-of-plane (HOOP) mode at 979 cm−1 suggests that the chromophore in pR is distorted at the vinyl and adjacent C8–C9 bonds. The formation of pB′ involves chromophore protonation based on the protonation state marker at 1174 cm−1 and on the sensitivity of the COH bending at 1148 cm−1 as well as the combined C–OH stretching and C7H=C8H bending mode at 1252 cm−1 to D2O substitution. The hydrogen out-of-plane Raman intensity at 985 cm−1 significantly decreases in pB′, suggesting that the pR-to-pB′ transition is the stage where the stored photon energy is transferred from the distorted chromophore to the protein, producing a more relaxed pB′ chromophore structure. The C=O stretching mode downshifts from 1660 to 1651 cm−1 in the pB′-to-pB transition, indicating the reformation of a hydrogen bond to the carbonyl oxygen. Based on reported x-ray data, this suggests that the chromophore ring flips during the transition from pB′ to pB. These results confirm the existence and importance of the pB′ intermediate in photoactive yellow protein receptor activation.

INTRODUCTION

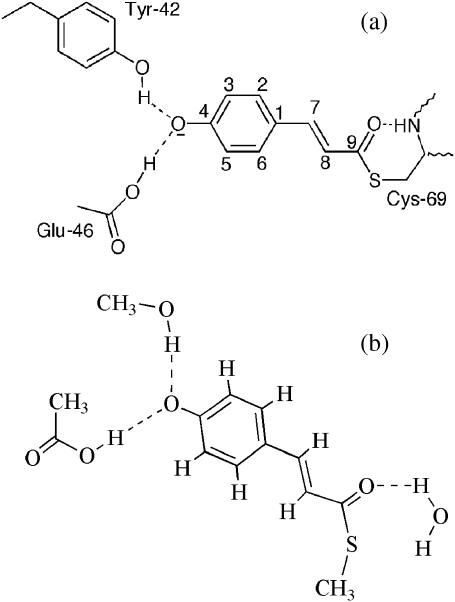

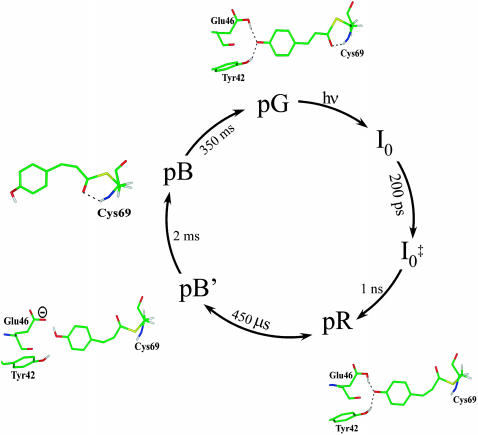

The blue light receptor photoactive yellow protein (PYP) is an attractive system for studying the mechanism of light-transduction processes as well as functional protein dynamics because of its small size (14 kD), water solubility, ease of crystallization, and similarity with bacteriorhodopsin (Hellingwerf et al., 2003; Hoff et al., 1994a; Meyer et al., 1987). The structure of PYP consists of five α-helices and six β-strands forming a central β-sheet (Borgstahl et al., 1995). The photoactive 4-hydroxycinnamic acid chromophore of PYP (Fig. 1) is covalently bound to Cys-69 via a thioester linkage (Baca et al., 1994; Hoff et al., 1994a; Kim et al., 1995). In the dark state the PYP chromophore is in the trans configuration about the vinyl C=C bond (Borgstahl et al., 1995), and the phenol group is deprotonated (Kim et al., 1995). The phenolate oxygen is stabilized by a hydrogen-bonding network involving Tyr-42 and the protonated side chain of Glu-46 (Borgstahl et al., 1995) that also plays a major role in tuning the absorption maximum (Genick et al., 1997b; Mihara et al., 1997). Upon absorption of blue light (λmax = 446 nm), PYP undergoes a photocycle with a quantum yield of 0.64 (Meyer et al., 1989) or 0.35 (van Brederode et al., 1995), which involves trans-cis isomerization of its chromophore and structural changes of both the chromophore and the protein. These conformational changes then modulate interactions with an unknown factor in the signaling pathway (Spudich, 1994; Yaghmai and Hazelbauer, 1992).

FIGURE 1.

The 4-hydroxycinnamyl chromophore structure of photoactive yellow protein in the dark state (a) and the model used for vibrational frequency calculations (b).

The PYP photocycle has been characterized with time-resolved UV/vis spectroscopy (Devanathan et al., 1999; Gensch et al., 2002; Imamoto et al., 1996; Ujj et al., 1998), x-ray crystallography (Baca et al., 1994; Genick et al., 1998; Ren et al., 2001), NMR (Craven et al., 2000) and vibrational spectroscopies (Brudler et al., 2001; Unno et al., 2002; Xie et al., 2001), circular dichroism spectroscopy (Chen et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2001a), and photothermal techniques (Takeshita et al., 2002a,b; van Brederode et al., 1995). The primary isomerization event in PYP is complete in a few picoseconds, producing the earliest red-shifted states with similar absorption properties (λmax = 510 nm), named I0 and I0‡ (Devanathan et al., 1999; Ujj et al., 1998). After a few nanoseconds, I0‡ thermally relaxes to the pR intermediate (λmax = 465 nm; also referred to as I1 or PYPL), which finally converts on the submillisecond timescale to a blue-shifted signaling state of PYP called pB (λmax = 355 nm, also referred to as I2 or PYPM). Vibrational spectroscopy (Brudler et al., 2001; Unno et al., 2002; Xie et al., 2001) has revealed that the chromophore structure in pR is cis and deprotonated; the trans-cis isomerization appears to be achieved without dramatic movements of the aromatic ring in the initial light photoreaction (Genick et al., 1998; Xie et al., 1996). Therefore, the hydrogen-bonding network involving Tyr-42 and Glu-46 remains intact in pR and stabilizes the chromophore anion. The transition from pR to the signaling state pB consists of protonation of the chromophore and a large conformational change of the protein (Craven et al., 2000; Hoff et al., 1999; Lee et al., 2001b; Ohishi et al., 2001).

Proton transfer between the protein and the chromophore upon pB formation is likely to play a crucial role in the PYP photocycle. Time-resolved step-scan FTIR spectroscopy (Xie et al., 2001) has been used to examine the proton transfer pathway. These results demonstrated that proton transfer from Glu-46 to the chromophore leads to the formation of a new intermediate (pB′) between pR and pB, which was not previously identified by transient absorption. In addition, proton transfer results in the formation of an energetically unstable buried charge, Glu-46−, that is thought to provide the driving force for structural changes of the protein during the transition from pB′ to pB (Groenhof et al., 2002; Xie et al., 2001). A recent study exploring the kinetic deuterium isotopic effect in PYP provided indirect evidence for the existence of the pB′ state as well as an equilibrium between the pB′ and pR intermediates (Hendriks et al., 2003). We were thus interested in obtaining time-resolved resonance Raman spectra of pB′ at room temperature to determine the vibrational structure of the chromophore and to address how the chromophore structure changes in the transitions from pR-to-pB′ and pB′-to-pB.

Time-resolved resonance Raman spectroscopy is an ideal tool for obtaining detailed structural information about short-lived transient intermediates (Mathies et al., 1987; Pan and Mathies, 2001; van den Berg et al., 1990). We recently developed a time-resolved resonance Raman microchip flow technique and successfully used it to obtain high-quality, transient Raman spectra of key rhodopsin intermediates at physiologically relevant temperatures on the 250-ns–1-ms timescale (Pan et al., 2002; Pan and Mathies, 2001). Here we have used this technique to obtain transient Raman spectra of the pR, pB′, and pB intermediates of PYP. A comparison of their vibrational spectra reveals the structural changes that occur upon formation of pB′ from pR. These data provide new information on the interactions between the protein and chromophore after the intramolecular proton transfer that lead to photoreceptor activation.

EXPERIMENTAL METHODS

Sample preparation

Photoactive yellow protein was overexpressed in Escherichia coli and purified as described (Xie et al., 1996) except that the histidine-tagged PYP gene was contained in the pQE-80L plasmid transformed into E. coli BL21 cells and the cells were lysed by sonication. All Raman experiments were carried out using 100-μM PYP samples in 50 mM sodium phosphate, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.0 buffer. Deuterated PYP samples were prepared by dialysis (three times) with Slide-A-Lyzer (Pierce, Rockford, IL) cassettes for 4 h at 4°C with D2O buffer (pD 7.0).

Time-resolved resonance Raman spectroscopy

Transient Raman spectra of the pR intermediate were obtained by using the time-resolved Raman microchip flow technique reported previously (Pan and Mathies, 2001). Briefly, the nearly collinear pump (476.5 nm) and probe (413.1 nm) beams were focused using a Raman microprobe to form displaced ∼3 × 100-μm spots in a flowing sample stream. For the pR intermediate measurement, the power of the probe beam is 150 μW, which provides a photoalteration parameter (Mathies et al., 1976) of 0.4, indicating that ∼40% of the PYP molecules are photolyzed by the probe beam. The pump power of 3.5 mW with a photoalteration parameter of 3.0 was chosen to maximize photolysis of PYP. A microfabricated channel (∼70-μm deep × 190-μm wide) in a glass sandwich structure (Simpson et al., 1998) was used as a single pass flow cell because it requires minimal sample volume (∼5 mL) for good signal/noise ratio spectra. The flow rate (50 cm/s) and the physical separation (100 μm) between pump and probe beams were chosen to give a 200-μs delay time for detecting Raman scattering from pR whose lifetime is 450 μs (Hendriks et al., 2003; Xie et al., 2001).

The transient Raman experiments of pB′ and pB were performed using a dual-beam, pump-probe flow configuration (Ames and Mathies, 1990). The sample (2.0 OD/cm at 446 nm) was recirculated from a 4-mL reservoir through a 1.0-mm diameter quartz capillary tube. The photocycle was initiated with a spherically focused 413.1-nm beam (70-μm diameter). A focused 356-nm probe beam (40-μm diameter, 2 mW), displaced from the pump, was used to excite the Raman spectrum from the intermediates. The photoalteration parameter of the pump beam was 2.0 based on a quantum yield of 0.35. Kinetic studies show that the pB′ state is formed in hundreds of microseconds and its lifetime is 2 ms (Xie et al., 2001). In our experiment, the pB′ Raman spectrum was measured with a 660-μs time delay (spatial separation of ∼1 mm and flow rate of 150 cm/s). For the pB Raman spectrum, a time delay of 10 ms was provided by a 50-cm/s flow rate and a 5-mm separation between the pump and probe beams. The power of the pump beam is 14 mW for pB′ and 5 mW for pB. The transient Raman spectrum of each species was obtained by subtracting the probe-only spectrum from the pump-plus-probe spectrum with a subtraction parameter determined by minimizing the positive and negative features of the C=O stretch mode (1633 cm−1) due to the ground state.

Raman spectra were detected with a cooled back-illuminated charge-coupled device (LN/CCD-1100/PB, Roper Scientific, Trenton, NJ) controlled by a ST-133 controller coupled to a subtractive dispersion, double spectrograph. All spectra were corrected for the wavelength dependence of the spectrometer efficiency by using a white lamp. Cyclohexane Raman bands were used to calibrate the spectrum giving ±1-cm−1 accuracy. The spectral bandpass is 8 cm−1 for pR experiments and 10 cm−1 for pB′ and pB experiments.

Computational methods

We performed vibrational frequency calculations for PYP chromophore models based on the density functional theory (DFT) method using Gaussian 98 (Frisch et al., 2001). The deprotonated hydroxycinnamyl methyl thioester was used as a model of the chromophore in the dark state; methanol, acetic acid, and H2O were used to represent the hydrogen-bond network of Tyr-42, Glu-46, and the backbone amide of Cys-69, respectively (see Fig. 1 b). The initial geometry for these components was taken from the crystal structure determined by Genick et al. (1998) and optimized. The optimized geometries along with the experimental parameters of PYP in the dark state are available in the Supplementary Material. For the pR simulation, the hydrogen-bonding network with Tyr-42 and Glu-46 remained intact, but the hydrogen bond between the carbonyl oxygen and the backbone amide Cys-69 was broken based on the mechanism of photoisomerization that is achieved via rotation of the carbonyl group of the chromophore (Genick et al., 1998; Xie et al., 1996). The pB′ state was simulated as a protonated cis hydroxycinnamyl methyl thioester without hydrogen bonds. We also calculated the protonated cis hydroxycinnamyl methyl thioester with a hydrogen bond from a water molecule to the carbonyl oxygen as an aid in interpreting the pB vibrational spectrum. All calculations were done using the B3LYP hybrid functional in combination with 6-31G(d) basis set. The frequencies of the normal vibrational modes were scaled by a factor of 0.9613 (Foresman and Frisch, 1996).

RESULTS

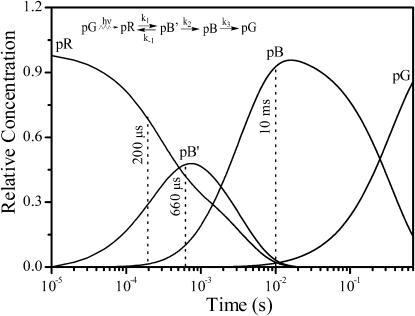

The time delays and excitation wavelengths used to obtain resonance Raman spectra of the pR, pB′, and pB intermediates were selected as follows. Based on current knowledge of the photocycle kinetics (Hellingwerf et al., 2003), the predicted relative concentrations of these three intermediates during the PYP photocycle are presented in Fig. 2. For the detection of pR a delay time of 200 μs was chosen with a 413.1-nm probe beam. At this time delay the concentration ratio of pR/pB′ is 2.3. However, the extinction coefficient of pB′ at the 413.1-nm excitation wavelength is essentially zero (Hendriks et al., 2003; Hoff et al., 1994b), so the contribution of pB′ to this transient Raman spectrum will be negligible. To selectively enhance the contribution of the pB′ intermediate, we chose a 356-nm probe wavelength that is distant from the pR absorption band (λmax = 465 nm). Since the pB′ and pB states have similar absorption properties (Hendriks et al., 2003), we predict that at a 660-μs time delay 82% of the Raman scattering will come from pB′ and 18% from pB. An error of 5% for the pB′/pB ratio is estimated to arise because the rate constants for the kinetic model are based on measurements with slightly different buffer conditions (Xie et al., 2001; Hendriks et al., 2003). Finally, the pure pB Raman spectrum was obtained at a 10-ms time delay with a 356-nm probe excitation.

FIGURE 2.

Temporal evolution of the relative concentrations of the dark state pG and its pR, pB′, and pB intermediates. The kinetic scheme for the intermediate concentrations at room temperature is described in the figure, where k1 and k−1 are 2200 and 1300 s−1, respectively, k2 is 500 s−1, and k3 is 2.87 s−1 at pH 7.0 (Meyer et al., 1989; Hoff et al., 1994b; Xie et al., 2001; Hendriks et al., 2003). The dashed lines indicate the time delays used for probing the Raman spectra of pR, pB′, and pB.

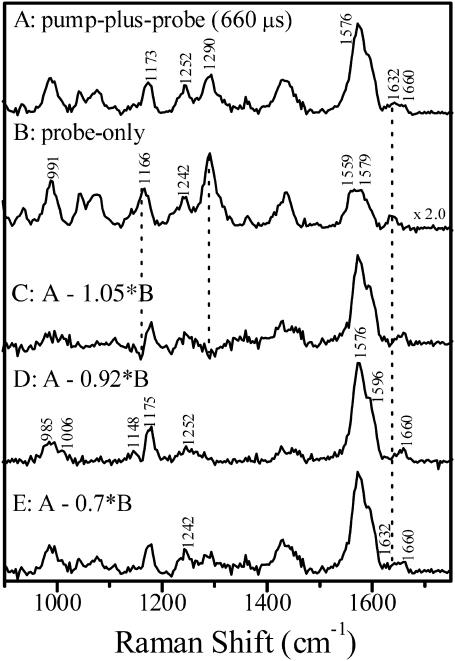

Fig. 3 presents the results of time-resolved resonance Raman experiments with a time delay of ∼660 μs. The probe-only spectrum of PYP was obtained using 356-nm excitation. Adding a 413.1-nm pump beam (Fig. 3 A) produces new bands at 1252 and 1660 cm−1 and significantly increases the ethylenic intensity at ∼1576 cm−1 due to resonance enhancement of the intermediate species, suggesting that it contains a mixture of scattering from pG, pB′, and pB. Subtraction of the probe-only spectrum from the pump-plus-probe to minimize the residual 1632-cm−1 band of the dark state yields an optimum difference spectrum with a subtraction parameter of 0.92 ± 0.05 (Fig. 3 D).

FIGURE 3.

Time-resolved resonance Raman spectrum of PYP with a 660-μs time delay. (A) Pump-plus-probe spectrum. (B) Probe-only spectrum. C–E present spectra obtained by subtracting the indicated fractions of the probe-only spectrum from the pump-plus-probe spectrum. The optimum subtraction parameter to isolate the pB′ spectrum was determined to be 0.92. The pump and probe excitation wavelengths were 413.1 and 356 nm, respectively.

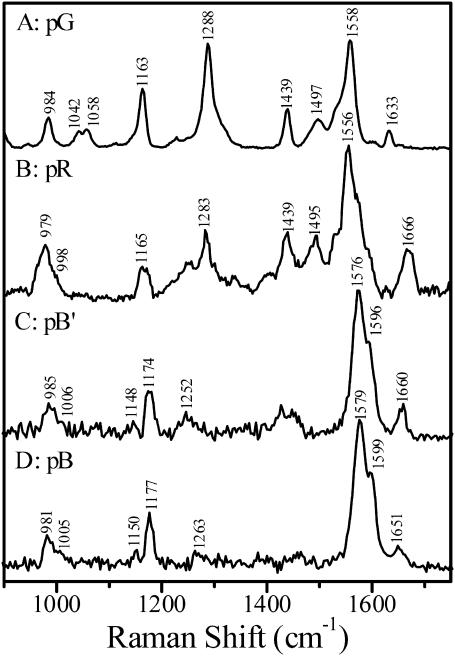

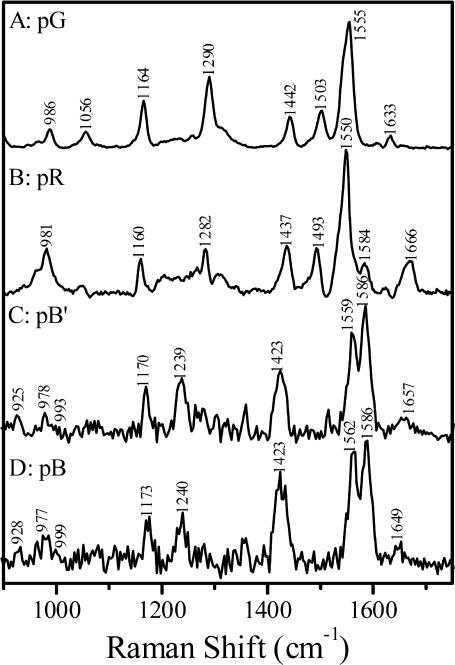

Time-resolved resonance Raman spectra of the pR, pB′, and pB intermediates obtained following similar procedures are presented in Fig. 4. The probe-only spectrum of the pG state (Fig. 4 A) excited with 413.1 nm is in good agreement with data reported previously (Kim et al., 1995). Visual inspection of the time-resolved spectra reveals that—as predicted by the kinetic model in Fig. 2—all three spectra are distinct. The temporal evolution of the spectrum measured using the 356-nm probe wavelength, which will be interpreted in detail below, provides direct evidence that confirms the presence of the pB′ intermediate, and shows that its chromophore structure is distinct from that in the pB intermediate.

FIGURE 4.

Time-resolved resonance Raman spectra of PYP and its pR, pB′, and pB intermediates at room temperature pH 7.0: (A) the PYP dark state (pG) spectrum obtained with 413.1 nm excitation, (B) the pR spectrum with a 200-μs time delay, (C) the pB′ spectrum obtained by subtracting 18% the pB spectrum from the transient Raman spectrum with a 660-μs time delay, and (D) the transient Raman spectrum of pB with a 10-ms time delay.

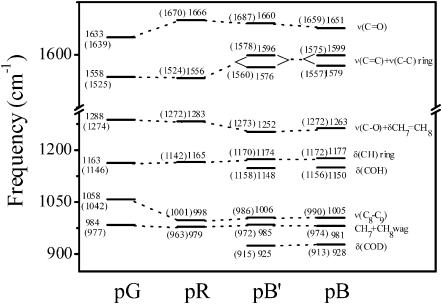

To aid in the assignment and interpretation of the resonance Raman spectra of the different PYP states, we performed DFT calculations designed to model the conformation and environment of the chromophore in the different intermediates. A comparison of observed and calculated frequencies is presented in Fig. 5. For the pG state, the most intense peak at 1558 cm−1 is due to coupling of the aromatic ring C–C stretching and the vinyl bond C=C stretching modes. The corresponding mode is calculated at 1525 cm−1. The band at 1633 cm−1 is assigned to the carbonyl group C=O stretching mode, consistent with the calculated normal mode at 1639 cm−1. The band at 1058 cm−1 has been assigned to the C8–C9 stretching mode based on the isotopic shift (∼14 cm−1) caused by 13C-substitution at C9 (Unno et al., 2002). The C–H bending of the aromatic ring is calculated at 1146 cm−1. We thus assigned the Raman band at 1163 cm−1 to the C–H bending of the chromophore aromatic ring, which is analogous to the Y9a mode of tyrosine (Harada and Takeuchi, 1986). This assignment is supported by chromophore ring deuteration experiments (Imamoto et al., 2001). The band at 984 cm−1 corresponds to the hydrogen out-of-plane (HOOP) mode of the C7H=C8H group that is calculated at 977 cm−1. The strong line at 1288 cm−1 is tentatively attributed to the coupling of C–O stretching and C7H=C8H bending (Unno et al., 2003); the calculation predicts this coupled mode at 1274 cm−1.

FIGURE 5.

Correlation diagram of the vibrational frequencies observed in the PYP dark state (pG), and the pR, pB′, and pB intermediates. The values in parentheses correspond to the calculated vibrational frequencies, which were obtained by using the models for simulating the conformation and environment of the chromophore in the different intermediates (see text). The calculated COD bending frequency for the pB′ and pB intermediates is also presented in parentheses.

Fig. 4 B presents the transient Raman spectrum with a 200-μs time delay that is dominated by pR scattering. The C=C stretching mode at 1556 cm−1 is identical to that of pG. However, the C=O stretching mode in pR is observed at 1666 cm−1, a dramatic 33-cm−1 upshift compared to pG. The DFT calculations show a similar upshift (31 cm−1) for the C=O stretching mode as a result of the cis configuration and the concomitant loss of the hydrogen bond between the carbonyl oxygen and the backbone amide of Cys-69. The 998-cm−1 shoulder is assigned to the C8–C9 stretching mode, ∼60 cm−1 lower than in pG. The calculated C8–C9 stretch shifts from 1042 cm−1 in the trans pG chromophore to 1001 cm−1 in the cis pR configuration. The 1165-cm−1 line in pR corresponds to the ring C–H bending and the 979-cm−1 line to the C7H=C8H HOOP mode, consistent with the calculations.

Fig. 4 C presents the Raman spectrum of the pB′ intermediate. The pB′ spectrum is characterized by its distinctive doublet ethylenic band at 1576 and 1596 cm−1, a ∼38-cm−1 upshift compared to pR. The 1174-cm−1 line corresponds to the ring C–H bending, 9 cm−1 higher than the corresponding mode of pR, and 11 cm−1 above the C–H bending mode in pG. The line at 1660 cm−1 is assigned to the C=O stretch, and the shoulder at 1006 cm−1 is assigned to the C8–C9 stretch. A similar result has been observed in FTIR studies that also demonstrated that the 1000-cm−1 band is sensitive to C8D substitution (Imamoto et al., 2001). In addition, a weak band at 1148 cm−1 appears in the pB′ spectrum that was not observed in pG and pR.

Fig. 4 D presents a pure Raman spectrum of pB obtained with a time delay of 10 ms. The vibrational pattern of pB is similar to that of pB′. A doublet at 1579 and 1599 cm−1 corresponds to the coupling of the C=C and ring C–C stretching. The 1005-cm−1 line is assigned to the C8–C9 stretch and the 981-cm−1 line to the C7H=C8H HOOP mode. A weak band at 1150 cm−1 is also observed in pB. The 1177-cm−1 band corresponds to the ring C–H bending. It is important to note that the C=O stretching band clearly shifts down by 9 cm−1 to 1651 cm−1 in the transition from pB′ to pB.

The Raman spectra of PYP in the dark state and its intermediates in D2O buffer are presented in Fig. 6. In general, the Raman spectra of pG and pR in D2O are identical to those in H2O except that the 1042/1058-cm−1 doublet changes to a single band at 1056 cm−1. However, significant changes appear in the pB and pB′ Raman spectra after the protein is suspended in D2O buffer. The coupled C=C and ring C–C stretching modes at 1576 and 1596 cm−1 in pB′ shift to 1559 and 1586 cm−1 in D2O, respectively. The band at 1288 cm−1 in pG (1283 cm−1 in pR) exhibits only a ∼1–2-cm−1 isotopic shift in D2O, whereas the 1252-cm−1 band in pB′ shifts 13 cm−1 to 1239 cm−1 in D2O, and the 1263-cm−1 band in pB shifts 23 cm−1 to 1240 cm−1. The sensitivity to deuteration suggests that the 1252-cm−1 band in pB′ is a combination of C–OH stretching and C7H=C8H bending. The D2O-induced shift of the ring C–H bending mode is −4 cm−1 for pB′ and −3 cm−1 for pB. However, the weak band observed at 1148 cm−1 in pB′ and 1150 cm−1 in pB shifts to 925 and 928 cm−1 in D2O, respectively. Based on the D2O experiments, we therefore assign this weak band to the COH bending mode. This assignment is supported by our calculations for the protonated cis chromophore. The calculated COH bending (1158 cm−1) mode exhibits an isotopic shift of 243 cm−1.

FIGURE 6.

Room temperature time-resolved resonance Raman spectra of PYP and its intermediates in D2O phosphate buffer at pD 7.0: (A) the pG Raman spectrum, (B) the pR Raman spectrum, (C) the pB′ Raman spectrum, and (D) the pB Raman spectrum.

DISCUSSION

Time-resolved resonance Raman spectra allow us to study the chromophore structural dynamics that result from photochemical reactions within photoactive proteins (Kim et al., 2001; Pan et al., 2002). Here we compare the vibrational spectra of PYP in the dark state and its pR, pB′, and pB intermediates to elucidate the chromophore structural changes and to probe interactions with the protein during the transitions that lead to receptor activation.

Chromophore structure of pR

The pG dark state of PYP has a deprotonated trans chromophore and its Raman spectrum is characterized by its 1558-cm−1 C=C stretching and 1058-cm−1 C8–C9 stretching modes. In the pR spectrum, the C=C stretch mode is identical to that in pG, but the C8–C9 stretch (at 998 cm−1) is ∼60 cm−1 lower. Since DFT calculations predict a similar downshift of this mode (41 cm−1) from the trans to the cis configuration, these data indicate that the chromophore structure of pR has a cis configuration about the C7=C8 bond. The C8–C9 mode has been proposed to function as a marker for the trans/cis configuration of the PYP chromophore (Unno et al., 2002), in line with the results reported here. A number of features in the vibrational spectrum of the pR state indicate that the chromophore remains ionized in this early intermediate. First, the C–O stretching and C7H=C8H bending combination at 1283 cm−1 are insensitive to D2O substitution, indicating that the chromophore remains ionized. The protonation state marker (Unno et al., 2002) provided by the C–H bending mode at 1165 cm−1 in pR also shows that the chromophore remains ionized at this stage of the photocycle.

A study on the hydrogen-bonding environment of tyrosine showed that a stronger hydrogen bond results in a lower C–O stretching frequency when the phenolic hydroxyl group acts as a proton acceptor (Takeuchi et al., 1989). The analogous shift of the C–O stretching and C7H=C8H bending combination from 1288 cm−1 in pG to 1283 cm−1 in pR indicates that the hydrogen bonding to the chromophore phenolate oxygen in pR is strengthened. This suggests that the hydrogen bonding to the chromophore phenolate oxygen in pR is preserved, consistent with FTIR studies (Brudler et al., 2001; Xie et al., 2001). The preservation of this hydrogen bonding implies that the chromophore's aromatic ring has not moved significantly in the process of photoisomerization.

The C=O stretching mode also provides insight into the hydrogen bonding of this chromophore oxygen. The relatively low frequency of this mode at 1633 cm−1 in pG is consistent with the hydrogen bond between the C=O and the backbone amide of Cys-69 that was derived from x-ray crystallography (Borgstahl et al., 1995). Fig. 4 shows that the vibrational frequency of the C=O stretch shifts from 1633 cm−1 in pG to 1666 cm−1 in pR. Such a large shift (+33 cm−1) of the C=O stretching mode provides evidence that the hydrogen bond between the carbonyl oxygen and the backbone amide group of Cys-69 is broken in the pR state (Unno et al., 2002). Our calculations predict a 31-cm−1 upshift of this mode upon removal of the hydrogen bond to the carbonyl oxygen. This observation supports a chromophore isomerization mechanism in which the carbonyl group flips to a new position, whereas the chromophore ring remains essentially in the same location (Xie et al., 1996). A flip in the position of the carbonyl oxygen of the chromophore is also consistent with x-ray crystallographic results (Genick et al., 1998; Ren et al., 2001)

Studies on retinal proteins have shown that hydrogen out-of-plane vibrations provide a probe of the conformational distortion of the chromophore (Eyring et al., 1982; Palings et al., 1987). Here we use HOOP modes to characterize the distortion of the PYP chromophore during the photocycle. The C7H=C8H HOOP in pG is observed at 984 cm−1 and the intensity of the C7H=C8H HOOP in pR increases significantly relative to the ring C–H bending mode. In the ground state, the chromophore is almost completely planar (Borgstahl et al., 1995). However, after isomerization, the planarity is lost (Genick et al., 1998; Ren et al., 2001), presumably due to intermolecular effects as well as steric hindrance between the carbonyl oxygen and the aromatic ring atoms. The crystal structure of a cryotrapped early intermediate revealed that the chromophore has an extremely distorted geometry that stores much of the initial photon energy (Genick et al., 1998). Therefore, although the transition from I0‡ to pR involves relaxation of the chromophore, the strong HOOP mode clearly indicates that the chromophore structure in pR is still twisted about the vinyl and adjacent C8–C9 bonds.

Proton transfer leading to formation of the pB′ state

FTIR data (Xie et al., 2001) indicated that the pR intermediate thermally relaxes to a new blue-shifted intermediate called pB′, absorbing at 360 nm (Hendriks et al., 2003). The changes in chromophore vibrational spectra observed between 660 μs and 10 ms during the photochemical reaction provide direct evidence for the existence of this intermediate and allow structural conclusions on this state to be drawn.

The COH bending mode in pB′ is detected as a weak band at 1148 cm−1, which shifts to 925 cm−1 in D2O, providing evidence that the phenolate oxygen of the chromophore is protonated. Similarly, the C–OH stretching and C7H=C8H bending combination at 1252 cm−1 in pB′ shows a 13-cm−1 D2O-induced shift, whereas the corresponding band at 1283 cm−1 in pR is not sensitive to deuteration. Moreover, the ring C–H bending mode at 1174 cm−1 in pB′ is 9 cm−1 higher than the corresponding mode in pR. This may result from the repulsion between the hydrogen atoms of the phenolate moiety and the phenyl ring in the protonated state (Takeuchi et al., 1989). All these results strongly support the idea that the chromophore becomes protonated in the transition from pR to pB′, in line with conclusions based on time-resolved FTIR spectroscopy of PYP (Xie et al., 2001). In addition, the intensity of the C–OH stretching and C7H=C8H bending combination at 1252 cm−1 in pB′ is significantly changed relative to that in pR; this change most likely results from the altered local protein environment in the pR-to-pB′ transition.

The light-induced intramolecular proton transfer probably occurs from Glu-46 to the chromophore (Xie et al., 1996; Imamoto et al., 1997; Xie et al., 2001). This proton transfer collapses the hydrogen-bonding network, making the structure of the chromophore binding site more flexible (Groenhof et al., 2002). Therefore, the electrostatic contribution to the hydrogen bond formed between the protonated chromophore and Tyr-42 is dramatically weakened upon formation of pB′. Compared to pR, the Raman intensity of the C7H=C8H HOOP at 985 cm−1 in the pB′ intermediate significantly drops, implying that the loss of the strong hydrogen-bonding interaction releases the conformation constraints on the chromophore.

Structural changes during the photocycle

Our experiments show that the vibrational spectrum of the chromophore in pB is similar to that of pB′ except for the C=O stretching mode. The COH bending and the C8–C9 stretching modes in pB are observed at 1150 and 1005 cm−1, respectively. The sensitivity of these modes to D2O substitution, together with the position of the C–H bending mode at 1177 cm−1, supports that the chromophore is protonated. The reduced intensity of the C8H=C9H HOOP band at 981 cm−1 suggests that the chromophore structure in pB is largely planar. The C=O stretching at 1651 cm−1 is 9 cm−1 lower than that of pB′ and 15 cm−1 below the corresponding mode of pR. The downshift of the C=O stretching from 1660 to 1651 cm−1 reports on the hydrogen bonding environmental changes at the carbonyl oxygen during the transition from pB′ to pB. Our calculations predict a 28-cm−1 downshift from pB′ to pB when a hydrogen bond is formed with the carbonyl group. We therefore propose that a hydrogen bond is made with the carbonyl oxygen upon pB formation. The hydrogen-bonding donor could be a new alternative residue or backbone amide. Based on the crystal structure of pB reported by Genick et al. (1997a), this hydrogen bond could be formed with the backbone amide of Cys-69, suggesting that a major chromophore rearrangement occurs in the transition from pB′ to pB involving a flip of the position of the phenolate ring.

A graphics model of the chromophore-active site is presented in Fig. 7 to schematically depict these structural changes. In the dark pG state, the chromophore is trans and deprotonated. The hydrogen-bonding network involving Glu-46 and Tyr-42 stabilizes the phenolate oxygen of the chromophore. After photoisomerization, pR has a twisted cis chromophore structure. Since the chromophore in pR is deprotonated, the hydrogen bonding at the phenolate oxygen remains intact. Furthermore, the trans-cis isomerization moves the carbonyl oxygen away from the backbone amide of Cys-69, disrupting the hydrogen bonding between the carbonyl oxygen and backbone. The carbonyl oxygen is thus located in a hydrophobic pocket formed by the aromatic side chain of Phe-96 as well as the aromatic ring of the chromophore (Genick et al., 1998).

FIGURE 7.

Graphics model of the active site of PYP illustrating the chromophore structural changes in the photocycle.

The formation of pB′ involves intramolecular proton transfer from Glu-46 to the phenolate oxygen and loss of the strong hydrogen-bonding interaction between the chromophore and the protein. Therefore, the pR-to-pB′ transition is likely to be the stage where the stored photon energy is transferred from the distorted chromophore to the protein, producing a relaxed pB′ chromophore structure. The light-induced proton transfer also results in the formation of a buried charge, Glu-46−, which would interact strongly with the chromophore and alter its environment through electrostatic-dielectric interaction. This newly formed charge that remains in a highly hydrophobic pocket in pB′ (Xie et al., 2001) in general is energetically unstable. The resulting conformational change likely triggers the chromophore rearrangement that results in the reformation of the hydrogen bond at the carbonyl oxygen in pB, thereby moving the phenolate moiety away from Glu-46. Such a large movement of the chromophore implies that the transition from pB′ to pB involves significant protein alteration, leading to activation of the PYP receptor. Collectively, our results confirm the presence of the pB′ intermediate in the photocycle of PYP and support a possible mechanistic role for the pB′→pB transition in the formation of a signaling state.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

An online supplement to this article can be found by visiting BJ Online at http://www.biophysj.org.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ziad Ganim and Michael J. Tauber for technical assistance and helpful discussions.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (EY02051) and the National Science Foundation (CHE 98-01651) to R.A.M., and by a National Institutes of Health grant (GM63805) to W.D.H.

References

- Ames, J. B., and R. A. Mathies. 1990. The role of back-reactions and proton uptake during the N→O transition in bacteriorhodopsin's photocycle: a kinetic resonance Raman study. Biochemistry. 29:7181–7190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baca, M., G. E. O. Borgstahl, M. Boissinot, P. M. Burke, D. R. Williams, K. A. Slater, and E. D. Getzoff. 1994. Complete chemical structure of photoactive yellow protein: novel thioester linked 4-hydroxycinnamyl chromophore and photocycle chemistry. Biochemistry. 33:14369–14377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgstahl, G. E. O., D. R. Williams, and E. D. Getzoff. 1995. 1.4 Å structure of photoactive yellow protein, a cytosolic photoreceptor: unusual fold, active site and chromophore. Biochemistry. 34:6278–6287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brudler, R., R. Rammelsberg, T. T. Woo, E. D. Getzoff, and K. Gerwert. 2001. Structure of the I1 early intermediate of photoactive yellow protein by FTIR spectroscopy. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8:265–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, E., T. Gensch, A. B. Gross, J. Hendriks, K. J. Hellingwerf, and D. S. Kliger. 2003. Dynamics of protein and chromophore structural changes in the photocycle of photoactive yellow protein monitored by time-resolved optical rotatory dispersion. Biochemistry. 42:2062–2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craven, C. J., N. M. Derix, J. Hendriks, R. Boelens, K. J. Hellingwerf, and R. Kaptein. 2000. Probing the nature of the blue-shifted intermediate of photoactive yellow protein in solution by NMR: hydrogen-deuterium exchange data and pH studies. Biochemistry. 39:14392–14399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devanathan, S., A. Pacheco, L. Ujj, M. Cusanovich, G. Tollin, S. Lin, and N. Woodbury. 1999. Femtosecond spectroscopic observations of initial intermediates in the photocycle of the photoactive yellow protein from Ectothiorhodospira halophila. Biophys. J. 77:1017–1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyring, G., B. Curry, A. Broek, J. Lugtenburg, and R. Mathies. 1982. Assignment and interpretation of hydrogen out-of-plane vibrations in the resonance Raman spectra of rhodopsin and bathorhodopsin. Biochemistry. 21:384–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foresman, J. B., and A. Frisch. 1996. Exploring Chemistry with Electronic Structure Methods. Gaussian, Inc., Pittsburgh.

- Frisch, M. J., G. W. Trucks, H. B. Schlegel, G. E. Scuseria, M. A. Robb, J. R. Cheeseman, V. G. Zakrzewski, J. J. A. Montgomery, R. E. Stratmann, J. C. Burant, S. Dapprich, J. M. Millam, A. D. Daniels, K. N. Kudin, M. C. Strain, O. Farkas, J. Tomasi, V. Barone, M. Cossi, R. Cammi, B. Mennucci, C. Pomelli, C. Adamo, S. Clifford, J. Ochterski, G. A. Petersson, P. Y. Ayala, Q. Cui, K. Morokuma, D. K. Malick, A. D. Rabuck, K. Raghavachari, J. B. Foresman, J. Cioslowski, J. V. Ortiz, A. G. Baboul, B. B. Stefanov, G. Liu, A. Liashenko, P. Piskorz, I. Komaromi, R. Gomperts, R. L. Martin, D. J. Fox, T. Keith, M. A. Al-Laham, C. Y. Peng, A. Nanayakkara, C. Gonzalez, M. Challacombe, P. M. W. Gill, B. Johnson, W. Chen, M. W. Wong, J. L. Andres, C. Gonzalez, M. Head-Gordon, E. S. Replogle, and J. A. Pople. 2001. Gaussian98. Gaussian, Inc., Pittsburgh.

- Genick, U. K., G. E. O. Borgstahl, N. Kingman, R. Zhong, C. Pradervand, P. M. Burke, V. Srajer, T.-Y. Teng, W. Schildkamp, D. E. Mcree, K. Moffat, and E. D. Getzoff. 1997a. Structure of a protein photocycle intermediate by millisecond time-resolved crystallography. Science. 275:1471–1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genick, U. K., S. Devanathan, T. E. Meyer, I. L. Canestrelli, E. Williams, M. A. Cusanovich, G. Tollin, and E. D. Getzoff. 1997b. Active site mutants implicate key residues for control of color and light cycle kinetics of photoactive yellow protein. Biochemistry. 36:8–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genick, U. K., S. M. Soltis, P. Kuhn, I. L. Canestrelli, and E. D. Getzoff. 1998. Structure at 0.85 Å resolution of an early protein photocycle intermediate. Nature. 392:206–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gensch, T., C. C. Gradinaru, I. H. M. van Stokkum, J. Hendriks, K. J. Hellingwerf, and R. van Grondelle. 2002. The primary photoreaction of photoactive yellow protein (PYP): anisotropy changes and excitation wavelength dependence. Chem. Phys. Lett. 356:347–354. [Google Scholar]

- Groenhof, G., M. F. Lensink, H. J. Berendsen, and A. E. Mark. 2002. Signal transduction in the photoactive yellow protein. II. Proton transfer initiates conformational changes. Proteins. 48:212–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada, I., and H. Takeuchi. 1986. Raman and ultraviolet resonance Raman spectra of proteins and related compounds. In Advances in Spectroscopy: Spectroscopy of Biological Systems. R. Clark and R. Hester, editors. Wiley, New York. 113–175.

- Hellingwerf, K. J., J. Hendriks, and T. Gensch. 2003. Photoactive yellow protein, a new type of photoreceptor protein: will this “yellow lab” bring us where we want to go? J. Phys. Chem. A. 107:1082–1094. [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks, J., I. H. van Stokkum, and K. J. Hellingwerf. 2003. Deuterium isotope effects in the photocycle transitions of the photoactive yellow protein. Biophys. J. 84:1180–1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoff, W. D., P. Düx, K. Hård, B. Devreese, I. M. Nugteren-Roodzant, W. Crielaard, R. Boelens, R. Kaptein, J. van Beeumen, and K. J. Hellingwerf. 1994a. Thiol ester- linked p-coumaric acid as a new photoactive prosthetic group in a protein with rhodopsin-like photochemistry. Biochemistry. 33:13959–13962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoff, W. D., I. H. van Stokkum, H. J. van Ramesdonk, M. E. van Brederode, A. M. Brouwer, J. C. Fitch, T. E. Meyer, R. van Grondelle, and K. J. Hellingwerf. 1994b. Measurement and global analysis of the absorbance changes in the photocycle of the photoactive yellow protein from Ectothiorhodospira halophila. Biophys. J. 67:1691–1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoff, W. D., A. Xie, I. H. M. van Stokkum, X. J. Tang, J. Gural, A. R. Kroon, and K. J. Hellingwerf. 1999. Global conformational changes upon receptor stimulation in photoactive yellow protein. Biochemistry. 38:1009–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamoto, Y., M. Kataoka, and F. Tokunaga. 1996. Photoreaction cycle of photoactive yellow protein from Ectothiorhodospira halophila studied by low-temperature spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 35:14047–14053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamoto, Y., K. Mihara, O. Hisatomi, M. Kataoka, F. Tokunaga, N. Bojkova, and K. Yoshihara. 1997. Evidence for proton transfer from Glu-46 to the chromophore during the photocycle of photoactive yellow protein. J. Biol. Chem. 272:12905–12908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamoto, Y., Y. Shirahige, F. Tokunaga, T. Kinoshita, K. Yoshihara, and M. Kataoka. 2001. Low-temperature Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy of photoactive yellow protein. Biochemistry. 40:8997–9004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M., R. A. Mathies, W. D. Hoff, and K. J. Hellingwerf. 1995. Resonance Raman evidence that the thioester-linked 4-hydroxycinnamyl chromophore of photoactive yellow protein is deprotonated. Biochemistry. 34:12669–12672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J. E., D. W. McCamant, L. Zhu, and R. A. Mathies. 2001. Resonance Raman structural evidence that the cis-to-trans isomerization in rhodopsin occurs in femtoseconds. J. Phys. Chem. B. 105:1240–1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, B. C., P. A. Croonquist, T. R. Sosnick, and W. D. Hoff. 2001a. PAS domain receptor photoactive yellow protein is converted to a molten globule state upon activation. J. Biol. Chem. 276:20821–20823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, B. C., A. Pandit, P. A. Croonquist, and W. D. Hoff. 2001b. Folding and signaling share the same pathway in a photoreceptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:9062–9067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathies, R., A. R. Oseroff, and L. Stryer. 1976. Rapid-flow resonance Raman spectroscopy of photolabile molecules: rhodopsin and isorhodopsin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 73:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathies, R. A., S. O. Smith, and I. Palings. 1987. Determination of retinal chromophore structure in rhodopsins. In Biological Applications of Raman Spectroscopy: Resonance Raman Spectra of Polyenes and Aromatics. T. G. Spiro, editor. John Wiley and Sons, Inc., New York. 59–108.

- Meyer, T. E., G. Tollin, J. H. Hazzard, and M. A. Cusanovich. 1989. Photoactive yellow protein from the purple phototrophic bacterium, Ectothiorhodospira halophila. Quantum yield of photobleaching and effects of temperature, alcohols, glycerol, and sucrose on kinetics of photobleaching and recovery. Biophys. J. 56:559–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, T. E., E. Yakali, M. A. Cusanovich, and G. Tollin. 1987. Properties of a water-soluble, yellow protein isolated from a halophilic phototrophic bacterium that has photochemical activity analogous to sensory rhodopsin. Biochemistry. 26:418–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihara, K., O. Hisatomi, Y. Imamoto, M. Kataoka, and F. Tokunaga. 1997. Functional expression and site-directed mutagenesis of photoactive yellow protein. J. Biochem. (Tokyo). 121:876–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohishi, S., N. Shimizu, K. Mihara, Y. Imamoto, and M. Kataoka. 2001. Light induces destabilization of photoactive yellow protein. Biochemistry. 40:2854–2859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palings, I., J. A. Pardoen, E. van den Berg, C. Winkel, J. Lugtenburg, and R. A. Mathies. 1987. Assignment of fingerprint vibrations in the resonance Raman spectra of rhodopsin, isorhodopsin and bathorhodopsin: implications for chromophore structure and environment. Biochemistry. 26:2544–2556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan, D., Z. Ganim, J. E. Kim, M. A. Verhoeven, J. Lugtenburg, and R. A. Mathies. 2002. Time-resolved resonance Raman analysis of chromophore structural changes in the formation and decay of rhodopsin's BSI intermediate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124:4857–4864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan, D., and R. A. Mathies. 2001. Chromophore structure in lumirhodopsin and metarhodopsin I by time-resolved resonance Raman microchip spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 40:7929–7936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Z., B. Perman, V. Srajer, T. Y. Teng, C. Pradervand, D. Bourgeois, F. Schotte, T. Ursby, R. Kort, M. Wulff, and K. Moffat. 2001. A molecular movie at 1.8 Å resolution displays the photocycle of photoactive yellow protein, a eubacterial blue-light receptor, from nanoseconds to seconds. Biochemistry. 40:13788–13801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, P. C., A. T. Woolley, and R. A. Mathies. 1998. Microfabrication technology for the production of capillary array electrophoresis chips. Biomed. Microdevices. 1:7–26. [Google Scholar]

- Spudich, J. L. 1994. Protein-protein interaction converts a proton pump into a sensory receptor. Cell. 79:747–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeshita, K., Y. Imamoto, M. Kataoka, K. Mihara, F. Tokunaga, and M. Terazima. 2002a. Structural change of site-directed mutants of PYP: new dynamics during pR state. Biophys. J. 83:1567–1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeshita, K., Y. Imamoto, M. Kataoka, F. Tokunaga, and M. Terazima. 2002b. Themodynamic and transport properties of intermediate states of the photocyclic reaction of photoactive yellow protein. Biochemistry. 41:3037–3048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi, H., N. Watanabe, Y. Satoh, and I. Harada. 1989. Effects of hydrogen-bonding on the tyrosine Raman bands in the 1300–1150 cm−1 region. J. Raman Spectrosc. 20:233–237. [Google Scholar]

- Ujj, L., S. Devanathan, T. E. Meyer, M. A. Cusanovich, G. Tollin, and G. H. Atkinson. 1998. New photocycle intermediates in the photoactive yellow protein from Ectothiorhodospira halophila: picosecond transient absorption spectroscopy. Biophys. J. 75:406–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unno, M., M. Kumauchi, J. Sasaki, F. Tokunaga, and S. Yamauchi. 2002. Resonance Raman spectroscopy and quantum chemical calculations reveal structural changes in the active site of photoactive yellow protein. Biochemistry. 41:5668–5674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unno, M., M. Kumauchi, J. Sasaki, F. Tokunaga, and S. Yamauchi. 2003. Assignment of resonance Raman spectrum of photoactive yellow protein in its long-lived blue-shifted intermediate. J. Phys. Chem. B. 107:2837–2845. [Google Scholar]

- van Brederode, M. E., T. Gensch, W. D. Hoff, K. J. Hellingwerf, and S. E. Braslavsky. 1995. Photoinduced volume change and energy storage associated with the early transformations of the photoactive yellow protein from Ectothiorhodospira halophila. Biophys. J. 68:1101–1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg, R., D. J. Jang, H. C. Bitting, and M. A. El-Sayed. 1990. Subpicosecond resonance Raman spectra of the early intermediates in the photocycle of bacteriorhodopsin. Biophys. J. 58:135–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie, A., W. D. Hoff, A. R. Kroon, and K. J. Hellingwerf. 1996. Glu46 donates a proton to the 4-hydroxycinnamate anion chromophore during the photocycle of photoactive yellow protein. Biochemistry. 35:14671–14678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie, A., L. Kelemen, J. Hendriks, B. J. White, K. J. Hellingwerf, and W. D. Hoff. 2001. Formation of a new buried charge drives a large-amplitude protein quake in photoreceptor activation. Biochemistry. 40:1510–1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaghmai, R., and G. L. Hazelbauer. 1992. Ligand occupancy mimicked by single residue substitutions in a receptor: transmembrane signaling induced by mutation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 89:7890–7894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.