Abstract

The light-driven proton pump bacteriorhodopsin (bR) is a transmembrane protein that uses large conformational changes for proton transfer from the cytoplasmic to the extracellular regions. Crystal structures, due to their solvent conditions, do not resolve the effect of lipid molecules on these protein conformational changes. To begin to understand the molecular details behind such large conformational changes, we simulated two conformations of wild-type bacteriorhodopsin, one of the dark-adapted state and the second of an intermediate (MO) state, each within an explicit dimyristoyl-phosphatidylcholine (DMPC) lipid bilayer. The simulations included all-hydrogen and all-atom representations of protein, lipid, and water and were performed for 20 ns. We investigate the equilibrium properties and the dynamic motions of the two conformations in the lipid setting. We note that the conformational state of the MO intermediate bR remains markedly different from the dark-adapted bR state in that the MO intermediate shows rearrangement of the cytoplasmic portions of helices C, F, and G, and nearby loops. This difference in the states remained throughout the simulations, and the results are stable on the molecular dynamics timescale and provide an illustration of the changes in both lipid and water that help to stabilize a particular state. Our analysis focuses on how the environment adjusts to these two states and on how the dynamics of the helices, loops, and water molecules can be related to the pump mechanism of bacteriorhodopsin. For example, water generally behaves in the same manner on the extracellular sides of both simulations but is decreased in the cytoplasmic region of the MO intermediate. We suspect that the different water behavior is closely related to the fluctuations of microcavities volume in the protein interior, which is strongly coupled to the collective motion of the protein. Our simulation result suggests that experimental observation can be useful to verify a decreased number of waters in the cytoplasmic regions of the late-intermediate stages by measuring the rate of water exchange with the interior of the protein.

INTRODUCTION

Bacteriorhodopsin (bR) is a purple membrane protein that acts as a light-driven proton pump in Halobacterium salinarum (Oesterhelt and Stoeckenius, 1971). The protein contains seven transmembrane α-helical subunits, helices A–G, that encapsulate a retinal chromophore covalently linked to residue Lys-216 via a protonated Schiff base (—C=NH+—). As an integral membrane protein, bacteriorhodopsin releases protons to the extracellular medium and takes up protons from the cytoplasmic medium, producing a chemical potential gradient across the cell membrane that is used for ATP synthase (Stock et al., 1999). Under steady-state illumination, bacteriorhodopsin completes a photocycle within 10 ms with the release of one proton to the extracellular side (Stoeckenius et al., 1979).

The photocycle is defined by a set of intermediate states in the sequence of K, L, M1, M2, N, and O. The intermediates are measured through spectral changes in the retinal and its surroundings, and thus do not directly comment on protein conformational change. Nonetheless, it is expected that protein conformational changes occur during the photocycle, and recent structural work has confirmed that assumption. In particular, electron diffraction work shows significant conformational changes in the M2 stage of the protein (Brown et al., 2002; Subramaniam et al., 1999). For wild-type bacteriorhodopsin in the dark-adapted state, the photocycle starts with the photoinduced isomerization of the all-trans retinal chromophore to the 13-cis conformation. On the completion of retinal isomerization, the protein responds locally with the formation of K and L intermediate states. During the transition from the L to the M1 intermediate, a proton is transferred from the Schiff base to Asp-85, and this is followed by the escape of a proton from the proton release group (Glu-194, Glu-204, and waters) to the extracellular medium (Balashov et al., 1997; Brown et al., 1995; Cao et al., 1995). During the M2 stage, a large conformational change of the protein occurs (Subramaniam et al., 1999). This change was shown to involve structural rearrangements on the cytoplasmic portion of the helices, especially helices E, F, G, and the EF loop, to create a water accessible region from the cytoplasmic side. The reprotonation of the Schiff base by a proton from Asp-96 occurs in the transition from M2 to the N intermediate. The thermal reisomerization of the retinal to the all-trans configuration and the reprotonation of Asp-96 from the cytoplasmic medium occur with the formation of the O intermediate. Finally, a proton transfer from Asp-85 to the proton release group (Glu-194, Glu-204, and waters) ends the photocycle with a return to the dark-adapted state.

The vectorial proton migration through the bacteriorhodopsin pump is closely linked to the set of local and global conformational changes in the K, L, M1, M2, N, and O intermediates. For wild-type bacteriorhodopsin, the global conformational change is associated with the structural rearrangement of cytoplasmic helices and loops from the early intermediates (K, L, and M1) to the later intermediates (M2, N, and O) (Subramaniam et al., 1999). This has been described as a switch between two conformations: from a cytoplasmically closed conformation (dark adapted) to a cytoplasmically open conformation (M2 and later intermediates). A variety of experimental methods have been used to measure the light-induced conformational change during the photocycle for wild-type bRs (Edman et al., 1999; Facciotti et al., 2001; Lanyi and Schobert, 2002, 2003; Luecke et al., 1999b; Royant et al., 2000; Sass et al., 2000; Schobert et al., 2003) and bR mutants (Facciotti et al., 2003; Luecke et al., 1999a, 2000; Oka et al., 2002; Rouhani et al., 2001; Schobert et al., 2003; Tittor et al., 2002; Weik et al., 1998; Xiao et al., 2000). Our study uses the results of Subramaniam and Henderson (2000b) for electron diffraction structures of both the wild-type dark-adapted bR and the D96G/F171C/F219L triple mutant in unilluminated 2D crystals. The structure of the triple mutant provides a definition of the light-induced protein conformational change, kinetically trapped by the mutation, and serves as a model for the late M intermediate. The conformational change observed in the triple mutant bR is associated with a large-scale structural rearrangement of the cytoplasmic portions of helices E, F, and G (Subramaniam et al., 1999; Weik et al., 1998).

The effect of the lipid bilayer environment on membrane proteins is not well understood. In particular, how the environment supports and adapts to different membrane protein conformations needs to be examined on a molecular level. Molecular dynamics simulations on membrane/protein systems provide useful insights into the molecular details of protein/lipid interactions. However, the simulations are challenging, since the amphipathic nature of lipid molecules requires long relaxation and simulation timescales. Relative to experiment, the simulations are still of small size and of short timescale. This situation will clearly improve with faster hardware and algorithmic developments. Molecular dynamics simulations of individual α-helices have now been performed by many groups and indicate the increasingly robust use of the method for insights into membrane/protein interactions (Bright and Sansom, 2003; Son and Sansom, 2000; Son et al., 2000). In a preliminary analysis to this article, individual bacteriorhodopsin α-helices in an explicit dimyristoyl-phosphatidylcholine (DMPC) lipid bilayer have been explored (Woolf, 1997, 1998a). Larger scale simulations of bacteriorhodopsin and other proteins are still challenging but are becoming more common (e.g., Baudry et al., 2001; Crozier et al., 2003; Hayashi et al., 2002, 2003; Radzwill et al., 2001; Tajkhorshid et al., 2000). Recently, the proton pumping mechanism of bacteriorhodopsin during the photocycle was explored from the standpoint of pK changes (Onufriev et al., 2003; Song et al., 2003). Defining the starting point for these all-atom calculations is difficult due to the long relaxation times of lipid molecules.

In this article, we investigate the equilibrium properties and dynamic motions of wild-type bacteriorhodopsin in the dark-adapted state and in the later M intermediate. The effect of the lipid environment on protein conformation is included by simulating the proteins within an explicit DMPC lipid bilayer. The starting point of the lipid/protein systems was from a library of preequilibrated and prehydrated DMPC lipid molecules. The CHARMM program (Brooks et al., 1983) was used for the initial construction of the starting point and for the relaxation of the system to a production-ready stage with Ewald, constant normal pressure, constant cross sectional area, and constant temperature at 307 K. When construction and equilibration have been performed well, these simulations can offer tremendous insights into molecular behavior.

Another long-term goal of this work is to determine dynamic pathways between functionally important conformational states of membrane proteins like those found in the bacteriorhodopsin photocycle. It is becoming increasingly common to have experimentally defined starting structures for large conformational transitions (Echols et al., 2003), but understanding how these large conformational transitions are coupled is not obvious from the structures themselves. Likewise, starting a molecular dynamics simulation from either conformation and waiting to observe a large-scale conformational change is not reasonable because the molecular dynamics timescale is so short relative to the timescale for large-scale conformational change. This is especially true for simulations in complex environments like a membrane bilayer. For these reasons, we, and others, have developed sampling techniques to improve the ability to explore possible dynamic pathways between conformations (Bolhuis et al., 2002; Dellago et al., 1998; Woolf, 1998b; Zuckerman and Woolf, 1999). The results from the present equilibrium simulations for bacteriorhodopsin in two different conformational states set the stage for this future work where we plan to apply our dynamic importance sampling (DIMS) techniques (Woolf, 1998b; Zuckerman and Woolf, 1999) to determine possible dynamic pathways between transition states.

In the following Simulation Methods section, a full description of the model and the simulation method is presented. Next is the Results section, which is divided into six subsections: the first presents the results for structural stability, the second shows helix motions, the third describes interaction energies, the fourth shows results for the interior water, the fifth presents the results for the hydrogen bonding network, and the sixth reveals results for normal mode calculations. The article discusses the importance of the results with a summary of key findings in a Discussion section.

SIMULATION METHODS

Two bacteriorhodopsins based on the electron diffraction of 2D crystal structures (Subramaniam and Henderson, 2000b; pdb numbers: 1FBB and 1FBK) were used for all-atom simulations. The CHARMM program was used to construct the starting points within an explicit DMPC lipid bilayer and water and to relax the systems to a production-ready stage. The LAMMPS code (Brightwell et al., 2000) was used for the starting point with the same force field that was used in the CHARMM code for the initial construction. Production runs were performed on a Cplant computer at Sandia National Laboratories taking full advantage of the parallel computation environment provided by the code and machines. For the two bacteriorhodopsin conformations, the simulations used identical environments, potential functions, and dynamics.

2D crystal structures

The 2D crystal structures of bacteriorhodopsin from electron diffraction studies (Subramaniam and Henderson, 2000b) provide insight into the structural analysis between the dark-adapted state and the later M intermediate. The 1FBB structure is a wild-type bR in the dark-adapted state, which contains an all-trans retinal configuration. The 1FBK structure is a D96G/F171C/F219L triple mutant in the dark-adapted state. The dark-adapted triple mutant can serve as model for the later M intermediate, since even without illumination it presents the light-induced large conformational change that is associated with the late M intermediate in the bR photocycle. This large conformational change is associated with a structural rearrangement of helices E, F, and G on the cytoplasmic side (Subramaniam et al., 1999; Weik et al., 1998). The MO intermediate is obtained by replacing the triple mutant residues, Gly-96 of helix C, Cys-171 of helix F, and Leu-219 of helix G, into Asp-96, Phe-171, and Phe-219, respectively. The MO intermediate shows a large conformational change as seen in the later M intermediate and retains an all-trans retinal configuration as observed in the O intermediate. For both conformations, Asp-96 and Asp-115 are protonated (Roux et al., 1996).

Building a unit cell containing lipid bilayer

Since crystal structures do not reveal the exact locations of lipid molecules around the protein, our method closely follows the previous method, which has been successfully applied to gramicidin (Woolf and Roux, 1994, 1996), α-helical systems (Woolf, 1997, 1998a), and rhodopsin (Crozier et al., 2003). A unit cell that has two layers of lipids surrounding the central protein and contains almost 40,000 atoms is constructed. The appropriate cell dimensions should be computationally efficient and have a protein-lipid concentration that is consistent with the experimental value (White and Wimley, 1999). Since current molecular dynamics practice cannot adequately maintain a constant surface tension of the lipid bilayer throughout the simulation, constant membrane surface area is maintained, with a constant normal pressure applied in the direction perpendicular to the membrane. The effective (time-averaged) surface tension is determined by choice of lateral cell dimensions. To obtain the optimal value of cross sectional area for lipid and bacteriorhodopsin, the cross sectional area of lipid is taken from a recent experimental review of lipid area for pure lipid systems (Nagle and Tristram-Nagle, 2000), and the cross sectional area of bacteriorhodopsin is estimated using the CHARMM program. We used a value of 62 Å2 per DMPC lipid and lateral cell dimensions of 62 Å × 62 Å for the total unit cell.

Simple van der Waals (vdW) spheres representing lipid headgroups are placed in two parallel planes separated by the expected headgroup-to-headgroup DMPC lipid bilayer thickness. These planes can be regarded as membrane surfaces. Dynamics is performed on the spheres, constrained to their respective planes, with the embedded bR structure held rigid. This planar harmonic constraint ensures that the vdW spheres are randomly distributed onto the planes and well packed around the protein. Note however that the planar harmonic constraint on the vdW spheres is removed after the dynamics. The lipid bilayer is then constructed with headgroups at the positions of the vdW spheres. The 100 lipid molecules were randomly selected from a library of preequilibrated liquid crystalline state lipids. After replacement of the vdW spheres with lipid molecules, a series of minimizations is performed to remove overlaps of the alkane chains and gradually relax the system. TIP3P waters are then added and relaxed through a series of minimizations and dynamics. In addition to the bulk water, a water molecule is inserted into the nonpolar channel on the extracellular side of the Schiff base, and four additional water molecules are added to the nonpolar channel on the cytoplasmic side of the Schiff base (Baudry et al., 1999, 2001; Roux et al., 1996). To electrically neutralize the system and obtain a salt concentration near 100 mM, 13 sodium and 15 chlorine atoms are added. The unit cells now contain a total of 38,295 atoms for the dark-adapted state and 38,292 atoms for the MO intermediate.

Relaxation of initial configurations

Initial configurations are gradually relaxed, with the protein held rigid. To relax the solvent, dynamic cycles are performed with electrostatic cutoffs (12 Å) and constant temperature (Nosé-Hoover). This ensures that all degrees of freedom are adjusted as much as possible before the protein starts to move. In the subsequent stages, the protein is harmonically restrained, and then the harmonic restraints are gradually diminished, allowing the protein to adjust to the surrounding solvent. Harmonic restraints on the protein backbone atoms are gradually relaxed until gone, while performing dynamics in the NPT ensemble. A Nosé-Hoover thermostat/barostat is used to maintain a constant temperature of 307 K and a constant pressure of 1 atm. Subsequent equilibration stages include full Ewald electrostatics.

Production runs

Production runs of 20 ns each for the bacteriorhodopsin systems were performed at Sandia National Laboratories using the LAMMPS code on Cplant (Brightwell et al., 2000). At peak performance (100 processors), throughput of 1 ns/day was achieved. Analysis was performed with CHARMM on a Beowulf cluster at Johns Hopkins University.

RESULTS

We simulated two bacteriorhodopsin conformations, both with wild-type sequence, one starting from the dark-adapted state and the other starting from the later M intermediate state. We will refer to the later M intermediate state as the MO intermediate, since the structure of the M-like intermediate exhibits the large conformational change of the protein as seen in the later M intermediate, and yet has a retinal with an all-trans configuration as observed in the O intermediate. Note that the dark-adapted state in this article is the ground state but not functional, since the functional ground state of bacteriorhodopsin is the light-adapted state. In our simulations, the protein, lipid bilayer, water, and salt are explicitly present in atomic detail.

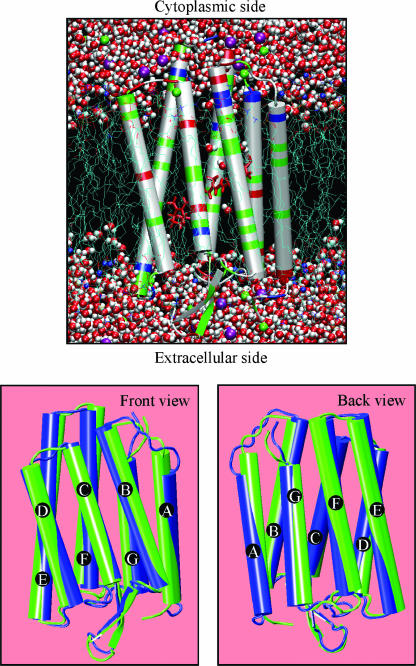

Structural stability

The cartoon representations shown in Fig. 1 are the starting point for the MO intermediate (top panel) and the average structures (bottom panels) that were determined from time-averaged molecular dynamics structures of bacteriorhodopsin started from two different states: the dark-adapted and the MO intermediate states. More details for the starting point are described in the Simulation Methods section. The time-averaged protein structures are obtained by accumulating and then averaging the protein's coordinates over the last half of the molecular dynamics simulation for each state. In the figure, the averaged structures of bacteriorhodopsin in the two states are superimposed to show the conformational differences between the states. The dark-adapted bR is shown in blue and the MO intermediate bR is shown in green. For brevity, lipid and water molecules are not shown in the figure, though they are part of the simulation. The primary sequence of the protein starts from the N-terminus located on the extracellular side and finishes at the C-terminus on the cytoplasmic side. The cytoplasm, in the figure, is located at the top, whereas the extracellular region is located at the bottom of the cartoons. Distinct geometrical differences between the two protein conformations are readily apparent. These structural differences include changes in the defined length of helix A (from the secondary structure definition used in VMD; Humphrey et al., 1996) and the orientations of helices F and G. The change in helix A length reflects changes in secondary structure of three residues, Val-29, Lys-30, and Gly-31, from the MO intermediate that are assigned to helix A on the cytoplasmic side, whereas they are assigned as members of AB loop in the dark-adapted state. The differences between the two conformations of bR observed in the orientations of helices F and G are a defining property of the MO intermediate that creates a cytoplasmically open structure.

FIGURE 1.

Outlines of the simulation system for the MO intermediate (top panel) and superposition of average structures (bottom panels) from the last half of the simulation for bacteriorhodopsin in the dark-adapted state (blue) and the MO intermediate (green). In the top figure, a water molecule is shown as red (oxygen) and white beads (hydrogen), a lipid tail is shown as a thread, phosphate in the lipid headgroup is shown as a blue bead, sodium is shown as a green bead, and chloride is shown as a purple bead. The protein is illustrated in a cartoon form in which a hydrophobic residue is shown in white, a polar residue is shown in green, a positively charged residue is shown in blue, and a negatively charged residue is shown in red.

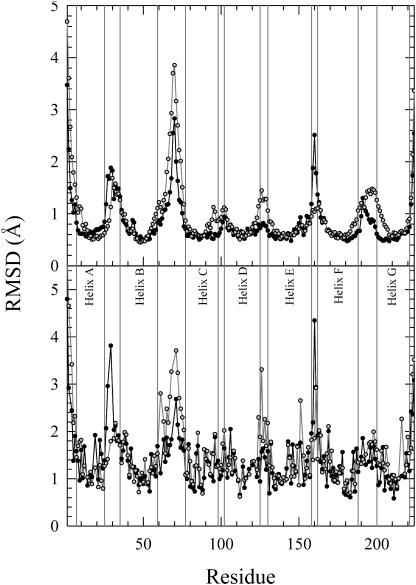

A useful measure of the reliability of a molecular dynamics calculation is the root-mean-squared (RMS) deviation from either the starting point or from the equilibrated structural beginning point of the calculation. Overall deviations that are very large (e.g., 5–10 Å or more) usually show a poorly defined simulation. Under some conditions large RMS values can instead indicate regions that have moved a great deal in the simulation or even indicate the presence of large conformational changes. For these evaluation purposes, we present RMS deviations relative to the starting point averaged over the 20-ns simulations of both simulations in Fig. 2. The figure shows Cα atoms in the protein backbone (top) and Cβ atoms in the side chains (bottom) for the dark-adapted state (solid symbols and lines) and for the MO intermediate (shaded symbols and lines). The starting point used for reference is a relaxed structure, in the CHARMM potential, with minor changes from the electron diffraction structure (Subramaniam and Henderson, 2000b). The RMS deviations of the Cα atoms are related to the backbone motion, whereas the RMS deviations of the Cβ atoms suggest the motion of the protein's side chains. As expected, loop regions show more motion than helical regions, which is reflected in the larger deviations from the starting point as indicated by peaks in the graph. In contrast, the helices have smaller deviations from the starting point, indicating that their average positions stay close to the starting point. The larger fluctuations in the RMS of the Cβ atoms as compared to that of the Cα atoms reflect the active motions of side chains.

FIGURE 2.

The average root-mean-squared deviation (RMSD) from the starting point for Cα atoms (top) and Cβ atoms (bottom) of bacteriorhodopsin in the dark-adapted state (solid symbols and lines) and the MO intermediate (shaded symbols and lines).

In addition, the results of Fig. 2 illustrate differences between the two states and between different regions of the protein. Note, for example, that there is more motion in the BC loop and in the N- and C-termini than in other regions. The AB and EF loops have the next larger set of motions, followed by smaller fluctuations in the CD, DE, and FG loops. Consistent with this, we note that large conformational changes in the EF loop have been observed in time-resolved fluorescence depolarization (Alexiev et al., 2003). The largest differences between the two states are seen in the Cα plots for the DE and EF loops and in the Cβ plots for the AB, BC, DE, and EF loops. These differences between the RMS fluctuations are also analyzed with the quasiharmonic analysis presented below in Fig. 14. Thus, the differences in time-averaged positions reflect differences in underlying dynamics between the two states.

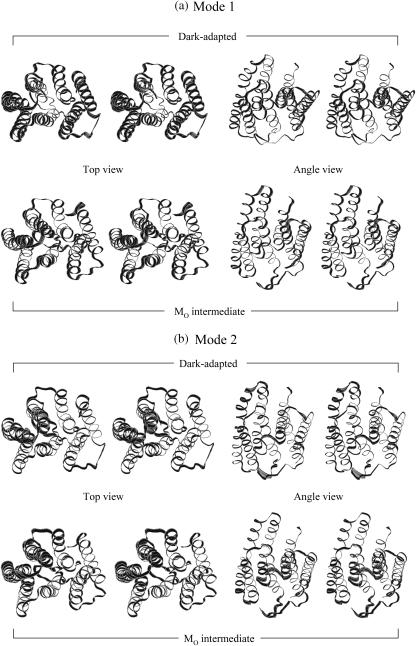

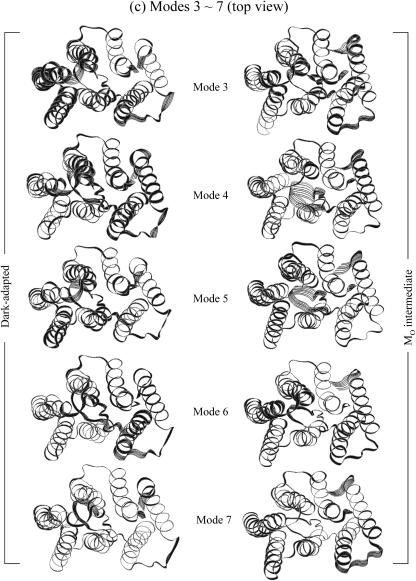

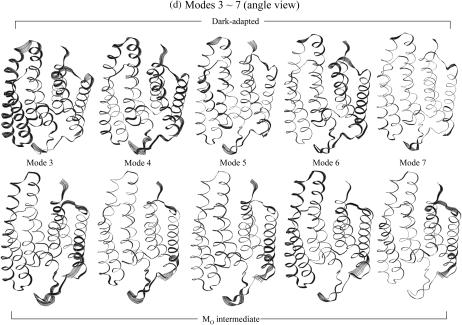

FIGURE 14.

Superposition of protein motions (a) at the frequency mode 1, (b) at the frequency mode 2 in stereo pair views, and at the modes from 3 to 7 (c) in the top views from cytoplasmic side and (d) in the angle views from the later side of the protein.

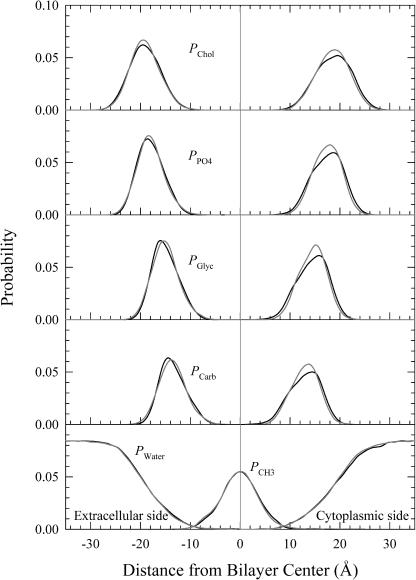

The average positions of lipid groups and water provide information on the environmental response within each simulation. Fig. 3 shows position probability distribution functions (P) for five different component groups of DMPC and for water as a function of distance from the bilayer center for the dark-adapted state (solid lines) and for the MO intermediate (shaded lines). The headgroup is divided into four subunits of choline (PChol), phosphate (PPO4), glycerol (PGlyc), and carbonyl (PCarb). The tailgroup consists of 12 saturated methylenes and one terminal methyl on each side of the two fatty acids (PCH3). The computed probability distribution functions, PChol, PPO4, PGlyc, PCarb, and PCH3, for the DMPC bilayer and PWater for water are similar to those observed in simulations of pure DPPC bilayers (Nagle and Tristram-Nagle, 2000; Petrache et al., 1997). However, there is an asymmetry present due to the protein. It is interesting to note how well the lipid and water have accommodated the protein with nearly identical trends in molecular group distribution on both sides of the bilayer. The differences are largely on the cytoplasmic side and reflect the time-averaged effect of the shift to a cytoplasmically open structure.

FIGURE 3.

Probability distribution functions (P) for different component groups of lipid (PChol (choline), PPO4 (phosphate), PGlyc (glycerol), PCarb (carbonyls), and PCH3 (methyl)) and for water (PWater) as a function of distance from the bilayer center for bacteriorhodopsin in the dark-adapted state (solid lines) and in the MO intermediate (shaded lines).

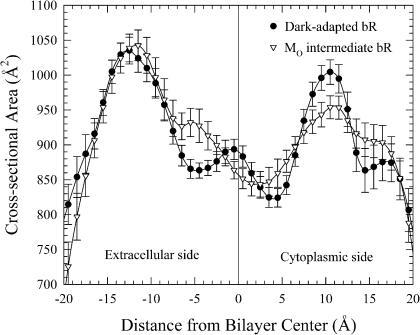

In a similar analysis to the time-averaged positions of environment atoms, the time-averaged cross section of the protein provides insight into the nature of the differences between the two states. Fig. 4 shows the time-averaged cross sectional area of the two protein states averaged over the 20-ns simulation as a function of distance from the bilayer center. In the calculation of the cross sectional area, the system's coordinates are shifted every picosecond to obtain a best fit to a reference coordinate set. This reference coordinate set was obtained by a reorientation of the coordinates at the starting point to compute the maximal cross sectional area at the membrane surface. This choice was made to maximize the functional conformational differences between the two states. It can be seen from the figure that for both bR states the cross sectional area is larger at the extracellular membrane surface (roughly located at −17 Å) than at the cytoplasmic membrane surface (roughly located at +17 Å). The difference of the cross sectional area at both membrane surfaces is closely related to the helix orientations within the lipid bilayer, since the outline of the helices defines the cross sectional area. It is interesting to note that in the region from −7 to −2 Å, the MO intermediate (open triangles) has a larger effective cross sectional area (by ∼50 Å2) than the dark-adapted form (solid circles). The helices do not orient in parallel to each other, but instead orient with different angles relative to the membrane normal, mediated by the lipid setting. At the cytoplasmic membrane surface, the cross sectional area of the MO intermediate bR is slightly larger (∼30 Å2) than the dark-adapted bR. This shift in cross sectional area is consistent with the idea that the MO intermediate is a state with a cytoplasmically open region. Changes in helix orientation and kink are tied to the opening mechanism.

FIGURE 4.

The average cross sectional area of the protein as a function of distance from bilayer center for bacteriorhodopsin in the dark-adapted state (•) and in the MO intermediate (▿).

Helix motions

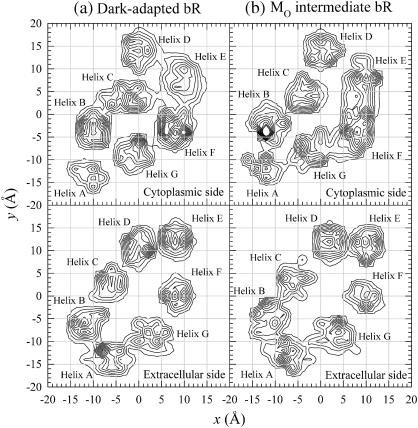

The free energy of gating the conformational shift in bacteriorhodopsin is determined by the ability of helices and loops to reorient in the lipid setting. Evaluating this full free energy surface is a major task, but some idea of the free energy surface is provided by analyzing the motion of helices in both simulations. The population distribution of x, y coordinates of the Cα atoms in each helix is shown in Fig. 5 for (a) the dark-adapted state and (b) the MO intermediate. The population distribution is obtained by mapping the coordinates of the Cα atoms of the extracellular and cytoplasmic sides separately onto the x-y planes and accumulating the coordinates over the 20-ns trajectory. The gradations of Cα density are represented by the contour lines, with the highest density at the peaks. This is reminiscent of the two-dimensional projection Fourier map obtained experimentally by electron diffraction (Subramaniam and Henderson, 2000a, 2000b; Subramaniam et al., 1999). Qualitative differences between the helix distribution at the cytoplasmic side for the dark-adapted state and that for the MO intermediate are apparent. For example, the cytoplasmic portion of helix C in the dark-adapted state is closely located to helix E, whereas for the MO intermediate, helix C is further apart from helix E as indicated by the gap in the distribution. Moreover, the cytoplasmic half of helix F in the MO intermediate is more flexible, shown in the graph as a relatively large spread over the region between helices E and G. This dynamic result is consistent with the experimental starting point and with the notion that a major structural rearrangement of the cytoplasmic portions of helices E, F, and G is associated with the shift to a cytoplasmically open conformation of the protein during the photocycle (Subramaniam et al., 1999; Weik et al., 1998). If the dynamics had instead shown a collapse back toward a single structure for both simulations, it would have been more difficult to understand the stability of the two structures on the experimental timescale. The extracellular ends of the helices for both bR conformations are more rigid than the cytoplasmic ends, since the helix distributions at the extracellular side are more localized. This is similar to a recent experimental study of elastic incoherent neutron scattering on bacteriorhodopsin suggesting that the extracellular parts of bR exhibit more rigid dynamics than the protein globally, showing an asymmetry in the distribution of flexibility (Réat et al., 1998). The rigidity is due to a hydrogen bonding network connected by waters on the extracellular side of the protein.

FIGURE 5.

Mapping of x, y coordinates of Cα atoms on the cytoplasmic half of the helix and on the extracellular half of the helix into the x-y plane for bacteriorhodopsin in (a) the dark-adapted state and (b) the MO intermediate.

A further analysis that is useful for understanding the dynamics of helices is the relative amount of rigid body helical motion. To examine the motions of the α-helical subsections, a best-fit cylinder is determined for each subsection, and then the cylinder axis is compared to the bilayer normal. Table 1 describes the average helix tilt angle over the 20-ns simulation θave, along with the helix tilt angle for the 2D crystal structure θc, the maximal helix tilt angle θmax, and the minimal helix tilt angle θmin. The helix tilt angles are slightly shifted relative to the 2D crystal values, indicating relaxation from the crystal structure that may be partly due to the CHARMM potential parameterization or the environmental effects of the simulated DMPC lipid and water. Note the large differences between the maximal and minimal values of helix tilt angles (average difference of 16.8° over all seven helices in both simulations). This indicates that the seven α-helices are flexibly moving within the environment, showing the importance of a dynamic perspective.

TABLE 1.

Helix tilt angles for bacteriorhodopsin in the dark-adapted state and MO intermediate

| (deg)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Helix | θc | θave | θmin | θmax |

| Dark-adapted state | ||||

| A | 18.1 | 21.4 ± 2.6 | 12.9 | 29.0 |

| B | 13.8 | 11.4 ± 2.6 | 4.6 | 22.0 |

| C | 15.0 | 14.6 ± 2.9 | 7.1 | 22.8 |

| D | 16.1 | 10.8 ± 3.0 | 0.4 | 18.8 |

| E | 12.6 | 14.7 ± 2.8 | 5.4 | 23.4 |

| F | 2.8 | 5.5 ± 2.5 | 0.0 | 14.2 |

| G | 4.8 | 9.8 ± 2.8 | 1.0 | 18.2 |

| MO intermediate | ||||

| A | 17.1 | 24.0 ± 3.1 | 14.8 | 33.1 |

| B | 10.1 | 9.6 ± 3.0 | 2.2 | 18.5 |

| C | 15.4 | 10.3 ± 2.8 | 3.8 | 18.4 |

| D | 9.4 | 11.3 ± 3.6 | 2.8 | 21.2 |

| E | 14.2 | 16.5 ± 2.5 | 7.4 | 23.6 |

| F | 3.1 | 11.7 ± 2.1 | 1.5 | 16.4 |

| G | 8.3 | 14.3 ± 3.4 | 5.8 | 24.6 |

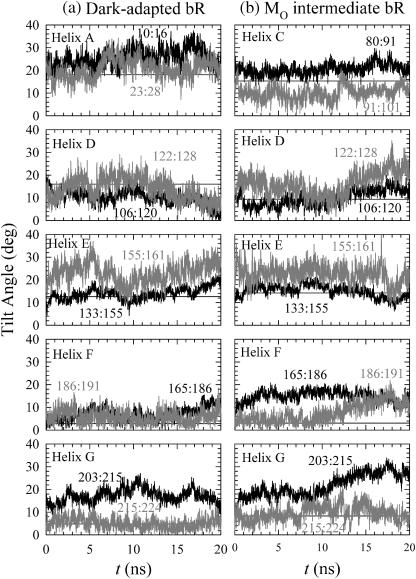

To further analyze rigid body motions of the helices, the behavior of α-helical subsections separated by kinking residues (e.g., glycine or proline) was determined. Each α-helical subsection was fit to a cylinder. Fig. 6 shows selected sets of time series for tilt angles, with each helix divided into two subsections at a hinge point. Each subsection's tilt angle was calculated separately. For the dark-adapted state in Fig. 6 a, helices A, D, and E exhibit a weak kink, whereas helix G shows a strong kink over the course of the simulation, as evidenced by the large differences between the tilt angles of its subsections. No kink is observed for helices B, C, and F. Helix A contains three glycine residues (Gly-16, Gly-21, and Gly-23) that are responsible for kinks. Helices B and C contain Pro-50 and Pro-91, respectively, but no kink is observed. Helices D and E exhibit a weak kink during the simulations with a possible hinge point at their respective glycine residues. No kink is observed around Pro-186 of helix F. Helix G is hinged at Ala-215, rather than at a proline or glycine residue as is more common. This nonproline kink is known as a π-bulge (Luecke et al., 1999b) and is due to the local unwinding of helix G near the retinal binding site where Ala-215 accepts a hydrogen bond from water.

FIGURE 6.

Time series of helix tilt angles for the bR helix subsections in (a) the dark-adapted state and (b) the MO intermediate. Residue ranges for each subsection are indicated. Horizontal lines mark helix tilt angles for the best-fit cylinder for the corresponding entire helices of the 2D crystal structure.

In the MO intermediate, helices B, D, E, and G show similar amounts of kinking as in the dark-adapted state. In contrast to the dark-adapted state, the MO intermediate exhibits strong kinking in helices C and F. In a recent study, the local flexibility of helix C with the hinge point at Pro-91 was also observed in the L intermediate (Neutze et al., 2002). The movement of the cytoplasmic end of helix F is hinged at Pro-186. The above observations suggest that a major structural rearrangement observed in the MO intermediate is associated with the kinks of the cytoplasmic portions of helices C, F, and G.

Interaction energy

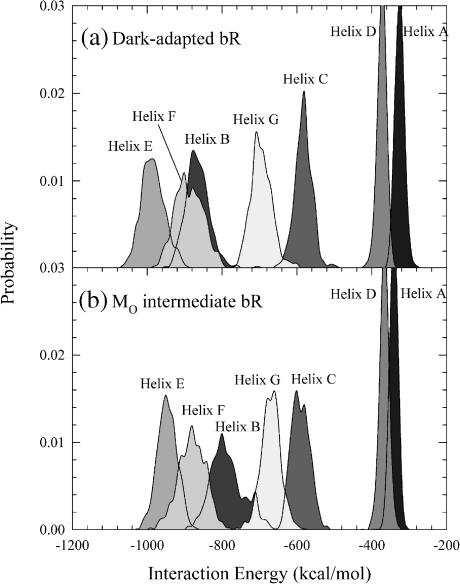

Analysis of interaction energies between subsets of atoms in the simulations gives insights into the dominant forces that stabilize a structure and also where the greatest flexibility can be found. To start this analysis, we first present interaction energies between helices and their environments. The calculation of the interaction energy between each helix and the surrounding environment was determined every 10 ps over the 20-ns simulation. The resulting distributions of interaction energies are shown in Fig. 7. The surrounding environment includes the other helices, the lipid, and the water. For our purposes, we define a strong interaction as E < −800 kcal/mol, an intermediate strength interaction as −800 kcal/mol < E < −400 kcal/mol, and a weak interaction as E > −400 kcal/mol. Helices E, F, and B have strong interactions with their environments, whereas helices G and C have intermediate strength interactions, and helices D and A have weak interactions. The interaction energy depends on helix length, since a longer helix has a greater number of residues involved in interactions. This is consistent with helix E, the longest helix, having the strongest interaction energy, whereas helix A, the shortest helix, shows the weakest interaction energy. However this trend is not always true, since helix D is longer than helices C and G, but its interaction energy is much weaker. In addition, all helices, except helices A and D, contain three charged residues (helix A contains no charged residues, and helix D contains only one charged residue). This suggests that electrostatic interactions of charged side chains also play an important role in helix interactions with the environment. For the MO intermediate, the shapes of the helix interaction energy distributions are qualitatively similar to those of the dark-adapted state, but the distributions are located within a smaller range of the interaction energy than found for the dark-adapted state.

FIGURE 7.

Probability of interaction energies for each helix with surroundings for bacteriorhodopsin in (a) the dark-adapted state and (b) the MO intermediate.

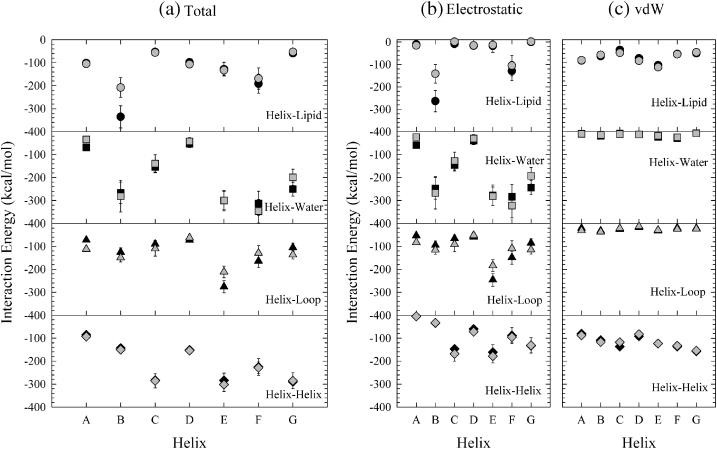

More detailed information on helix interactions with the surrounding environment is contained in Fig. 8. This shows interaction energies separately for each helix with lipid, water, loops, and other helices. Each helix has its own preference for interactions with the surrounding environment. Fig. 8 a shows the total interaction energy, Fig. 8 b shows the electrostatics contributions, and Fig. 8 c shows the vdW contributions. For the dark-adapted state (solid symbols), helices B and F strongly interact with lipid. The strong interactions of helix B and F with lipid are due to electrostatic interactions between the positively charged side chains in the helices and negatively charged phosphates in the lipid headgroup. This is structurally seen with the positively charged residues Lys-40 and Lys-41 of helix B and Lys-172 and Arg-175 of helix F near lipid headgroups at the cytoplasmic membrane surface. Helices B, E, F, and G interact strongly with water. The strong interactions between helices and water depend mainly on the size of the water accessible surface area for each helix. Helices B, E, and F are relatively longer than the thickness of the lipid bilayer. We note that small portions of the helices are extended into bulk water, mainly on the cytoplasmic side. The water immersed parts of the helices contain the negatively charged residues of Asp-38 in helix B, Glu-161 in helix E, and Glu-166 in helix F that are possible candidates for an acceptor with strong hydrogen bonding to bulk water. Although helix G is not so long as to be immersed in the water bath, the interaction between helix G and water is relatively strong. This is because helix G is interacting more strongly with the interior protein water than with the bulk water. Helix E strongly interacts with the loops. This can be rationalized by noting that the cytoplasmic part of helix C is located at the interface between helices E and F as seen in Fig. 5 a for the dark-adapted state. As a result, the loop connecting helices C and D (CD loop) on the cytoplasmic side is located close to helix E. This CD loop contains two negative residues, Asp-102 and Asp-104, that interact through a salt bridge with Lys-159 of helix E, producing a strong electrostatic interaction. Helices C, E, F, and G strongly interact with the other helices.

FIGURE 8.

Interaction energies for each helix with lipids, waters, loops, and other helices for bacteriorhodopsin in the dark-adapted state (solid symbols) and the MO intermediate (shaded symbols). Total interaction energies (a), as well as the electrostatic contributions (b) and the vdW contributions (c), are shown.

Comparing the MO intermediate and the dark-adapted state, we see that the interaction energies are qualitatively similar. However, the interaction of helix B with lipid is weaker for the MO intermediate than for the dark-adapted state. Moreover, the interaction of helix F with water is slightly stronger and the interaction of helix G with water is slightly weaker for the MO intermediate than it is for the dark-adapted state. It is intriguing to point out that the interaction of helix E with loops is weaker for the MO intermediate than it is for the dark-adapted state. This is due to the backward movement of the CD loop from helix E, weakening the electrostatic interaction between the charged residues of CD loop and helix E. This backward movement of the CD loop is produced by kinking within helix C as is observed in Fig. 5 b.

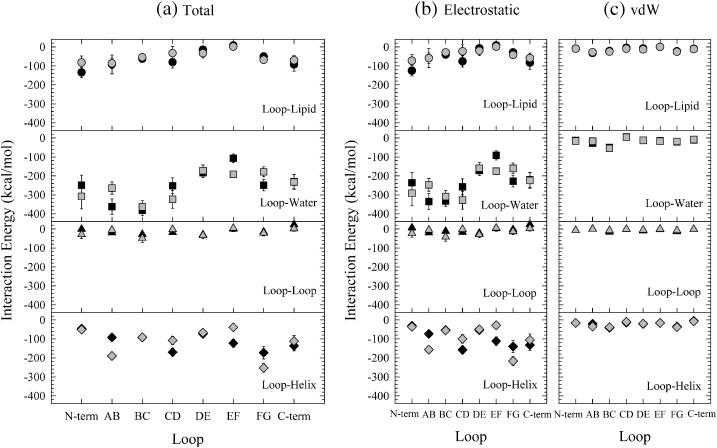

Fig. 9 shows interaction energies for each loop with lipid, water, other loops, and helices. It provides a sense of each loop's interaction preference with the surrounding environment. Fig. 9 a shows the total interaction energy, Fig. 9 b shows the electrostatic contributions, and Fig. 9 c shows the vdW contributions. As expected, due to their location, the loops interact more strongly with water than with lipid and are dominated by electrostatic effects. For the dark-adapted state (solid symbols), the interaction energies of all of the extracellular loops (BC, DE, and FG loops, except N-terminus) with water are slightly larger than those of the MO intermediate (shaded symbols). This indicates that the extracellular loops attract more water molecules in the dark-adapted state than in the MO intermediate. For the MO intermediate, two cytoplasmic loops, the CD and EF loops, have stronger interaction energies with water than with those in the dark-adapted state, further emphasizing that the MO intermediate is a cytoplasmically open structure. The interaction energy between the AB loop and water in the MO intermediate is significantly smaller than in the dark-adapted state, since the AB loop has fewer residues in the MO intermediate than in the dark-adapted state.

FIGURE 9.

Interaction energies for each loop with lipids, waters, other loops, and helices for bacteriorhodopsin in the dark-adapted state (solid symbols) and the MO intermediate (shaded symbols). Total interaction energies (a), as well as the electrostatic contributions (b) and the vdW contributions (c), are shown.

In the transition from the dark-adapted state to the MO intermediate state, the interaction energy between the CD loop and all the helices becomes weaker, whereas for the AB and the FG loops it becomes stronger. Structural differences between the two states lead to the energetic differences. For example, the weak interaction between the CD loop and all the helices in the MO intermediate is due to an increase in the interaction distance between the CD loop and helix E as a result of the kink of helix C. The strong interaction of the AB loop with helices in the MO intermediate is caused by the seceding residues from the loop, since these residues participate in the backbone hydrogen bonding in helix A.

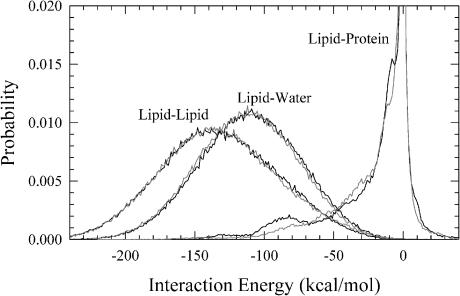

Lipids play an important role in coupling protein motion during the simulation. The interaction between lipid and protein varies from the relatively weak coupling of helices C and G to the strong coupling of helix B as shown in Fig. 8 a. Other lipid interactions are also important. The interaction energy distributions for lipid with the other lipids, water, and protein are shown in Fig. 10 for the dark-adapted state (solid lines) and the MO intermediate (shaded lines). It is interesting to note the broad and strong lipid-lipid and lipid-water interactions. For the lipid-protein interaction, the interaction energy distribution for the dark-adapted state exhibits a small peak at −85 kcal/mol that is not observed for the MO intermediate, indicating a change in coupling of lipid to protein with a stronger coupling in the dark-adapted state for this region of the distribution.

FIGURE 10.

Probability of lipid interaction energies with other lipids, waters, and protein for bacteriorhodopsin in the dark-adapted state (solid lines) and the MO intermediate (shaded lines).

Another conformational change is seen through the calculation of lipid and water accessible surface areas for each helix and loop. Table 2 summarizes the changes in accessible surface areas. As expected, helices have large lipid exposed surface areas and small water exposed surface areas, and vice versa for the loops. There is a good correlation between water exposed surface areas and helix/water interaction energies but a poor correlation between lipid exposed surface areas and helix/lipid interaction energies. Fig. 7 shows that helix B has the strongest interaction with lipid, whereas Table 2 shows that helix E has the largest lipid exposed surface area. In contrast, helices B, E, and F have the strongest interactions with water as well as the largest water exposed surface areas. Likewise for the loops, there is a poor correlation between lipid exposed surface areas and loop/lipid interaction energies but a much better correlation between water exposed surface areas and loop/water interaction energies.

TABLE 2.

Lipid and water accessible surface areas for helices and loops of bacteriorhodopsins in the dark-adapted state and MO intermediate

| Helices

|

Lipid accessible surface area (Å2)

|

Water accessible surface area (Å2)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loops | Dark-adapted bR | MO intermediate bR | Dark-adapted bR | MO intermediate bR |

| Helix A | 816.8 ± 47.9 | 818.0 ± 31.1 | 36.4 ± 17.2 | 34.6 ± 12.3 |

| Helix B | 587.9 ± 38.1 | 543.9 ± 52.7 | 234.8 ± 34.1 | 271.4 ± 47.3 |

| Helix C | 374.0 ± 38.2 | 465.7 ± 28.3 | 61.4 ± 19.4 | 88.3 ± 20.3 |

| Helix D | 649.1 ± 37.9 | 677.5 ± 37.2 | 71.7 ± 29.9 | 74.1 ± 38.6 |

| Helix E | 945.5 ± 42.5 | 911.1 ± 52.2 | 354.8 ± 56.4 | 376.5 ± 58.2 |

| Helix F | 468.3 ± 30.5 | 482.6 ± 22.2 | 361.4 ± 47.3 | 409.6 ± 40.7 |

| Helix G | 516.5 ± 28.3 | 473.4 ± 28.0 | 41.3 ± 17.7 | 65.3 ± 23.0 |

| N-term | 43.4 ± 15.8 | 26.7 ± 15.3 | 396.0 ± 71.0 | 460.4 ± 66.9 |

| AB loop | 121.1 ± 38.0 | 161.6 ± 25.1 | 558.0 ± 43.3 | 386.3 ± 39.7 |

| BC loop | 94.2 ± 30.0 | 105.7 ± 24.1 | 771.2 ± 48.5 | 848.3 ± 90.7 |

| CD loop | 4.7 ± 4.4 | 16.7 ± 4.7 | 110.5 ± 24.8 | 185.0 ± 36.6 |

| DE loop | 12.2 ± 12.5 | 41.7 ± 21.4 | 235.0 ± 36.9 | 241.2 ± 41.4 |

| EF loop | 0.02 ± 0.2 | 0.03 ± 0.2 | 304.2 ± 23.8 | 385.9 ± 20.9 |

| FG loop | 88.6 ± 40.5 | 115.1 ± 27.5 | 262.3 ± 64.5 | 231.5 ± 56.7 |

| C-term | 29.7 ± 13.9 | 46.8 ± 27.8 | 344.8 ± 41.4 | 297.8 ± 43.5 |

Interior protein defined water

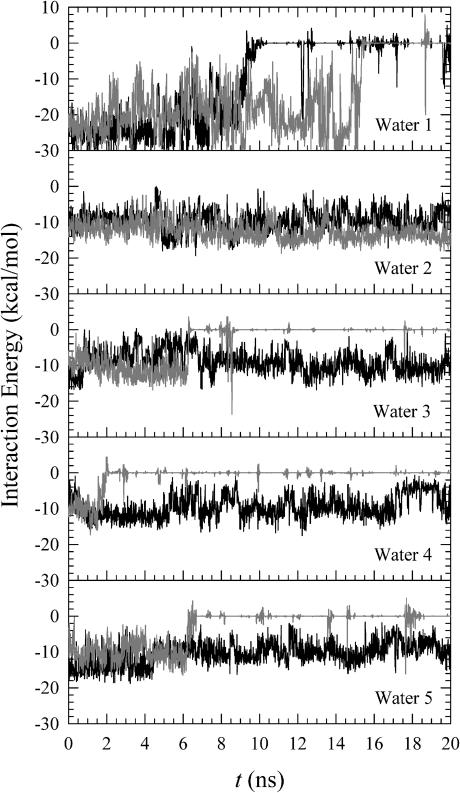

At the starting state of the simulation, an additional water molecule (labeled water 1) was inserted into the nonpolar part of the protein on the extracellular side of the Schiff base, and four additional water molecules (labeled waters 2–5) were added to the nonpolar region on the cytoplasmic side of the Schiff base (Baudry et al., 1999, 2001; Roux et al., 1996). These waters play an important role in transporting a proton during the photocycle, since they can form a continuous hydrogen bonding network between the Asp-96 side chain and the Schiff base. Fig. 11 shows the time series of the interaction energy for each interior water with the helix surroundings. Water 1 is initially placed in the extracellular region of the protein, forming a hydrogen bond to the N16-H16 group of the retinal. Waters 2–5 are initially located near the cytoplasmic side of the protein, establishing a continuous hydrogen bonding network from the Schiff base to Asp-96. For the dark-adapted state (solid lines), water 1 escapes from the protein at around 9 ns, whereas the other waters in the cytoplasmic part of the protein remain. However, for the MO intermediate (shaded lines), only water 2 remains in the protein at the end of the simulation.

FIGURE 11.

Time series of interaction energies for each interior water with helices for bacteriorhodopsin in the dark-adapted state (solid lines) and MO intermediate (shaded lines).

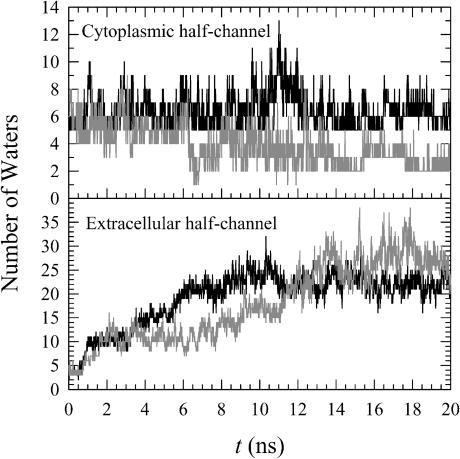

Although the initial internal waters escape from the hydrogen bonding network in the protein, additional waters from both sides of the membrane compensate for the lost waters during the simulation. To investigate the activity of water in the protein, the number of water molecules is counted in the region of the protein near the cytoplasm and near the extracellular region separately during the simulation. Fig. 12 shows the time series of the number of waters within both protein regions. For the cytoplasmically accessible region, it is clear that the dark-adapted bR (solid lines) has more waters than the MO intermediate bR (shaded lines). It is known that the cytoplasmic portion of the protein consists of many hydrophobic residues, and these residues are closely packed to each other preventing proton leakage over the hydrophobic barrier to the cytoplasmic medium (Neutze et al., 2002). The MO intermediate bR is a cytoplasmically open structure, indicating that waters in the protein can relatively easily move to the bulk. This appears to be the reason for waters moving into the cytoplasm and thus the small number of waters in the cytoplasmically accessible regions of the MO intermediate. For both states, the extracellular region of the protein contains more water molecules compared to the cytoplasmic region. This indicates that the extracellular region of the protein is easily accessible to bulk waters from the extracellular medium. Although the dark-adapted bR has more water molecules at t < 11 ns, the number of waters saturates at longer times and both states then have a similar number of waters in the extracellular regions of the protein. This suggests that the extracellular portions of both bacteriorhodopsin states are geometrically very similar in our simulations and are easily accessible to bulk waters from the extracellular medium.

FIGURE 12.

Time series of the number of waters in the cytoplasmic half channel (top) and in the extracellular half channel (bottom) for bacteriorhodopsin in the dark-adapted state (solid lines) and MO intermediate (shaded lines).

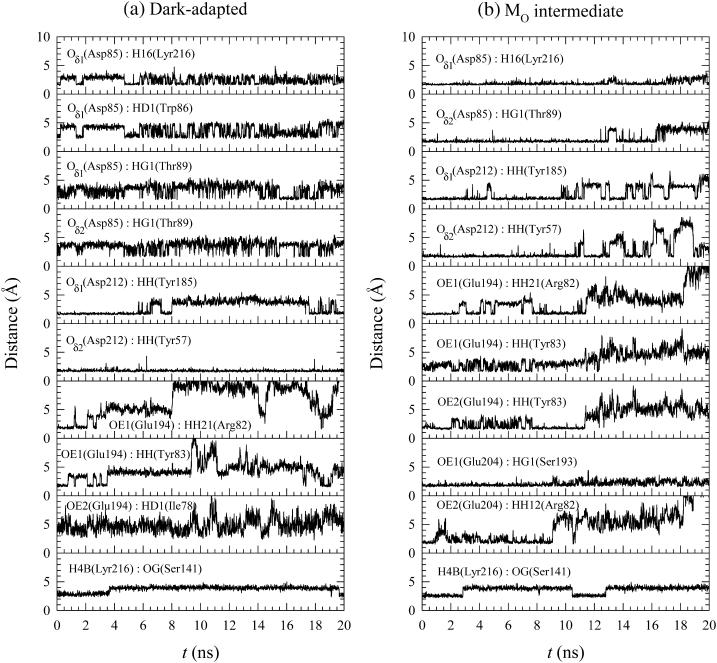

Hydrogen bonding network

Changes in the hydrogen bonding network may be important for the proton pumping mechanism during the photocycle. Since the CHARMM potential does not use an explicit term for hydrogen bonding, we estimated hydrogen bonding by looking at distances between a covalently bound hydrogen atom and a covalently bound electronegative acceptor atom, i.e., oxygen. Fig. 13 shows the time series of the distance between atoms for the selected pairs that are located in the protein. These atom pairs can be regarded as forming a hydrogen bond when the distance of the pair, d, is in the range of 1.8 Å < d < 2.4 Å. The data shows the dynamical nature of the hydrogen bond network and is consistent with the exchange of waters with the bulk as discussed above.

FIGURE 13.

The time series of atomic pair distances for bacteriorhodopsin in (a) the dark-adapted state and (b) the MO intermediate.

For the dark-adapted state in Fig. 13 a, the atom Oδ1 of Asp-85 forms a hydrogen bond with H16 of Lyr-216, but the bond fluctuates during the simulation. At the same time, Oδ1 of Asp-85 forms a hydrogen bond with HG1 of Thr-89, but there is fluctuation during the simulation. We observed a side-chain rotation within Asp-85 during the simulation, causing periodic fluctuations in the distance between Oδ1 of Asp-85 and other atoms. The hydrogen bond between Oδ1 of Asp-212 and the donor of HH (Tyr-185) is observed early in the simulation, but the bond is absent or unstable for the rest of the simulation. A very stable hydrogen bond between Oδ2 of Asp-212 and the donor of HH (Tyr-57) is seen during the simulation. The charged groups of Arg-82, Glu-194, and Glu-204 in the extracellular region compose the hydrogen bonding network at the starting point, but the hydrogen bonding network is disrupted as the simulations proceed. However, the hydrogen bonding network is compensated by the bulk water molecules from the extracellular medium. The water-mediated hydrogen bonding network is responsible for the rigidity, stabilizing the structure of the extracellular half of the protein (Neutze et al., 2002). The transition in the distance between OG of Ser-141 and H4B of Lyr-216 is related to the motion of the retinal. A stable hydrogen bond between OG1 of Thr-90 and the donor of HD2 (Asp-115) is observed in the cytoplasmic portion of the protein.

For the MO intermediate in Fig. 13 b, stable hydrogen bonds between Oδ1 of Asp-85 and the donor of H16 (Lyr-216) and between Oδ2 of Asp-85 and the donor of HG1 (Thr-89) are observed during the simulation. These stable bonds indicate that there is no side-chain rotation of Asp-85. A more stable hydrogen bond between Oδ2 of Asp-85 and the donor of HG1 (Thr-89) in the MO intermediate than in the dark-adapted state is consistent with recent experimental observations in a Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) study where the H-bond between Oδ2 of Asp-85 and the donor of HG1 (Thr-89) is stronger in K, L, and M than in the ground state (Kandori et al., 2001). Note, however that the Fourier transform infrared result disagrees with the x-ray structure of the intermediate, which shows that this bond is generally weak (Luecke et al., 1999a; Royant et al., 2000; Sass et al., 2000). The hydrogen bond between Oδ1 of Asp-212 and the donor of HH (Tyr-185) is more stable in the MO intermediate than in the dark-adapted state. However the hydrogen bond between Oδ2 of Asp-212 and the donor of HH (Tyr-57) is relatively more unstable in the MO intermediate than in the dark-adapted state, since frequent transitions are observed in the atomic pair distance at t > 10 ns. The charged groups of Arg-82, Glu-194, and Glu-204 in the extracellular half portion compose the stable hydrogen bonding network at the starting point, but the hydrogen bonding network is also compensated by the water-mediated hydrogen bonding network. Frequent transitions in distance between OG of Ser-141 and H4B of Lyr-216 are observed. A stable hydrogen bond between OG1 of Thr-90 and the donor of HD2 (Asp-115) is also observed in the cytoplasmic portion of the protein as seen in the dark-adapted state.

Normal mode analysis

Analysis of low frequency collective motions provides further insight into the differences between the two bR states. We performed quasiharmonic analysis (Teeter and Case, 1990; Brooks and Karplus, 1983) on the Cα motion for each 20-ns trajectory to calculate effective normal modes of vibration. In the calculations, overall translation and rotation are removed using the average coordinates as a reference. Each effective low frequency normal mode corresponds to a collective motion in the protein. Superimposed bacteriorhodopsin snapshots at the seven lowest frequency modes for the two different states of bacteriorhodopsin are presented in Fig. 14. For each mode, 10 sequential frames of the Cα motion are taken from the quasiharmonic period of vibration. In the figure, a large motion in the active site of the protein is highlighted with a wide ribbon that indicates large atomic fluctuations. At the lowest frequency mode (mode 1) in Fig. 14 a, the motions of bacteriorhodopsin in both states are nearly uniform, showing that the lowest mode is related to the global motion of the protein. In this mode, the motions are seen to be like a rigid body hinged at the middle and vibrating with low frequency. At the penultimate lowest frequency mode (2) in Fig. 14 b, the motion of the dark-adapted bR is also nearly uniform, indicating again that the second frequency mode is related to global motion. However, for the MO intermediate the second frequency mode exhibits some global motion but is distinctly different from the dark-adapted bR. The active sites of the MO intermediate bR in mode 2 are the cytoplasmic portions of helices and loops and the extracellular portions of helices and loops, vibrating independently in this frequency mode. In the first half of the vibrational mode period, the cytoplasmic portions of helices and loops are moving backward from the center of the protein, whereas at the same time the extracellular portions of helices and loops are moving forward toward the center of the protein, and vice versa in the second half of the vibrational mode. The periodic forward and backward motions at both ends of protein are only observed in the MO intermediate, and we believe that this may be related to the pump mechanism. Within modes 3–7 in Fig. 14, c and d, the large motions in the active sites of the proteins are localized into particular α-helices or particular loops. These collective motions of the proteins are associated with subdomain interactions and are distinctly different from each other at different frequency modes. Not all helices and loops have the same types of motion within the bilayer. Furthermore, even at the same modal frequency, the motions between the dark-adapted state and the MO intermediate are distinctly different. This indicates that the dark-adapted and the MO intermediate bacteriorhodopsins in the lipid bilayer exhibit different motions on the molecular dynamics timescale, and those motions may contribute to their different function roles in the photocycle.

DISCUSSION

There has been much debate about the nature of the conformational changes in bR that underlie the proton pumping mechanism (Baudry et al., 2001; Luecke and Lanyi, 2003). Although the current calculations do not permit us to comment on the full pathway and the coupling to the light isomerization itself, they do provide an important information for the interpretation of experimental measurements on the photocycle and on the types of protein conformational changes that may occur during the photocycle. In particular, the current debate has centered on how different regions of the protein may be alternatively cytoplasmically closed (during the dark stages) and then cytoplasmically open (during late M, N, O stages). The nature of these protein changes and their connection to the environment (the lipid and water setting) is key to understanding the full photocycle. The current calculations, by focusing all-atom attention on the bR dark state and the late-M stage, provide important guidelines for how the environment and the protein itself adapt to the set of changes forced by the photocycle.

One important observation, in this regard, is the behavior of the water on the cytoplasmic surface relative to the extracellular regions of the two simulations. Note that the water (Fig. 12) is generally behaving in the same manner on the extracellular sides of both simulations. Yet, on the cytoplasmic side, we observe a large change in the water behavior within the protein relative to bulk. This can provide a testable hypothesis on the rate of water exchange with the interior of the protein during the late-M, N, and O stages of the photocycle. In particular, the simulations suggest that time-resolved neutron scattering measurements should show a decreased number of water molecules in the cytoplasmic regions, relative to the extracellular regions at this stage of the photocycle. To our knowledge, this type of prediction on the water distribution in the later stages of the photocycle has not been made. Since the behavior of the water inside the protein has a profound impact on the collective motions of the protein, we further suggest that the collective motions of the protein are strongly influenced by the locations and the absence or presence of the internal waters.

In a somewhat similar way, recent experimental pressure measurements and analysis of x-ray structures have suggested that the presence of microcavities may be important for the pumping mechanism (Friedman et al., 2003; Klink et al., 2002). In this argument, the set of conformational changes that underlie the photocycle change the relative volumes of microcavities that are central to proton transfer. The experimental and structural analysis arguments are based on the thought that large changes in volume would be energetically expensive and that smaller changes in a collective structure would be more reasonable. The current calculations can be used to further elaborate this argument, since they imply that the role of interior waters and the coupling of the available volume fluctuations to the water and lipid environment is key to the consideration of the proton pumping mechanism. If the cytoplasmically open structure is considered a water-poor region, then it creates a picture for the proton transfer where the microvolumes can be further elaborated as key to the proton transition. That is, the coupling between water entry/exit and the collective motions that underlie the locations and the temporal dynamics of the microcavities can be essential to the proton transfer process.

Compensation of water and lipid to the membrane protein conformation are clearly observed in the simulations. This is central to the creation of the pumping mechanism. If the lipid and water did not support (or compensate) for the change in protein conformation, then it is difficult to envision how the pumping would occur. Phrased in another way, the protein clearly has to visit states that differ greatly in an energy evaluation performed in vacuum. If the environmental setting (the lipid and the water) did not enable the two conformations to remain stable (e.g., on the millisecond timescale), then it would be difficult for the proton transfer process to occur with a defined vectorial component and in a functionally relevant manner. By compensating, environmentally, between the two states, the lipid and water have contributed to the full pumping mechanism.

Thus, it is important to realize that the role of the environment in setting up the vectorial proton transfer is critical. A priori, one might have expected to find large changes in lipid and/or water behavior to stabilize the protein conformation. In fact, prediction would have suggested that large differences in interaction energies and in protein flexibility would be seen between the two states. Intriguingly, the simulations emphasize the degree of compensation that can occur: the water and lipid have adjusted to enable the two different protein conformations to remain stable. A foretaste of this finding is seen in Figs. 2 and 3 where the RMS deviations for the protein are generally the same, independent of the protein state. That is, note that the RMS deviations in protein helix and loop regions are markedly similar between the two conformations. In a similar way, Fig. 3 shows that the overall distribution of lipid is almost identical between the two states. This is despite the clear differences between the two conformations, as is reinforced in Figs. 4 and 5.

Despite the compensation of lipid and water interactions to support each of the two states, it is also clear that differences in flexibility and motions of the protein occur in the two states. This is most dramatically observed in Fig. 14 where quasiharmonic analysis is used to examine the lowest frequency collective modes of each simulation. These reflect differences seen in the computed trajectories and suggest that the types of collective motion that each state supports differ. Interestingly, the cytoplasmically open structure has a next to lowest quasiharmonic mode that may be close to the behavior expected for a gating transition that would control the degree of openness of the cytoplasmically open state. Experimentally, these types of differences could be seen through NMR or neutron scattering types of measurements, which can access both global and local motions and parse out their similarities and differences. Recent elastic incoherent neutron scattering measurements (Réat et al., 1998) have in fact shown that the cytoplasmic domains have more motion than the extracellular regions and are fully consistent with the current calculations.

A full free energy calculation of changes during the photocycle would be a large undertaking. One route would involve the definition of a reaction coordinate, possibly in multiple dimensions (Crouzy et al., 1999) and then the use of relative free energy methods to determine the relative free energy changes within that reduced surface (Woolf et al., 2004). Although this can be visualized for bacteriorhodopsin, the calculation is a large computational undertaking. An alternate route is the calculation of approximate kinetic transitions between the states under the constraints that the beginning and ending points are defined. This latter type of calculation can be further enhanced by the consideration of the ensemble of starting and ending points. We expect that the set of states defined by the dark-adapted and the M states of the current calculations can be used for this type of analysis.

Experimental investigations have largely concentrated on the spectral transitions that underlie the pumping mechanism. Although this reflects the available experimental methods, it does not allow a fully molecular description of the pumping mechanism. In this setting, molecular dynamics calculations can be invaluable. By providing a molecular model of how the protein moves, experimental ideas and conjectures on the proton transfer process can be considered in some detail. In this article, we performed all-atom calculations of the dark-adapted and the late-M stage states of the bR protein in explicit solvent. The results have suggested new, testable ideas for experimental measurement and further support the view of lipid/protein interactions that emphasizes the large compensation that can occur when either protein or lipid adjusts its conformation.

Acknowledgments

Sandia is a multiprogram laboratory operated by Sandia Corporation, a Lockheed Martin Company for the United States Department of Energy's National Nuclear Security Administration under contract DE-AC04-94AL85000. The work at Johns Hopkins University was supported under a grant from the American Cancer Society with contract ACS-RSG-01-048-01-GMC to T.B.W.

References

- Alexiev, U., I. Rimke, and T. Pohlmann. 2003. Elucidation of the nature of the conformational changes of the EF-interhelical loop in bacteriorhodopsin and of the helix VIII on the cytoplasmic surface of bovine rhodopsin: a time-resolved fluorescence depolarization study. J. Mol. Biol. 328:705–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balashov, S. P., E. S. Imasheva, T. G. Ebrey, N. Chen, D. R. Menick, and R. K. Crouch. 1997. Glutamate-194 to cysteine mutation inhibits fast light-induced proton release in bacteriorhodopsin. Biochemistry. 36:8671–8676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudry, J., S. Crouzy, B. Roux, and J. C. Smith. 1999. Simulation analysis of the retinal conformational equilibrium in dark-adapted bacteriorhodopsin. Biophys. J. 76:1909–1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudry, J., E. Tajkhorshid, F. Molnar, J. Phillips, and K. Schulten. 2001. Molecular dynamics study of bacteriorhodopsin and the purple membrane. J. Phys. Chem. B. 105:905–918. [Google Scholar]

- Bolhuis, P. G., D. Chandler, C. Dellago, and P. L. Geissler. 2002. Transition path sampling: throwing ropes over rough mountain passes, in the dark. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 53:291–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bright, J. N., and M. S. P. Sansom. 2003. The flexing/twirling helix: exploring the flexibility about molecular hinges formed by proline and glycine motifs in transmembrane helices. J. Phys. Chem. B. 107:627–636. [Google Scholar]

- Brightwell, R., L. Fisk, D. Greenberg, T. Hudson, M. Levenhagen, A. Maccabe, and R. Riesen. 2000. Massively parallel computing using commodity components. Parallel Computing. 26:243–266. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, B. R., R. E. Bruccoleri, B. D. Olafson, D. J. States, S. Swaminathan, and M. Karplus. 1983. CHARMM: a program for macromolecular energy minimization and dynamics calculations. J. Comput. Chem. 4:187–217. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, B., and M. Karplus. 1983. Harmonic dynamics of proteins: normal modes and fluctuations in bovine pancreatic trypsin-inhibitor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 80:6571–6575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, L. S., R. Needleman, and J. K. Lanyi. 2002. Conformational change of the E-F interhelical loop in the M photointermediate of bacteriorhodopsin. J. Mol. Biol. 317:471–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, L. S., J. Sasaki, H. Kandori, A. Maeda, R. Needleman, and J. K. Lanyi. 1995. Glutamic acid 204 is the terminal proton release group at the extracellular surface of bacteriorhodopsin. J. Biol. Chem. 270:27122–27126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y., L. S. Brown, J. Sasaki, A. Maeda, R. Needleman, and J. K. Lanyi. 1995. Relationship of proton release at the extracellular surface to deprotonation of the Schiff base in the bacteriorhodopsin photocycle. Biophys. J. 68:1518–1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crouzy, S., J. Baudry, J. C. Smith, and B. Roux. 1999. Efficient calculation of two-dimensional adiabatic and free energy maps: application to the isomerization of the C13=C14 and C15=N16 bonds in the retinal of bacteriorhodopsin. J. Comput. Chem. 20:1644–1658. [Google Scholar]

- Crozier, P. S., M. J. Stevens, L. R. Forrest, and T. B. Woolf. 2003. Molecular dynamics simulation of dark-adapted rhodopsin in an explicit membrane bilayer: coupling between local retinal and larger scale conformational change. J. Mol. Biol. 333:493–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellago, C., P. G. Bolhuis, F. S. Csajka, and D. Chandler. 1998. Transition path sampling and the calculation of rate constants. J. Chem. Phys. 108:1964–1977. [Google Scholar]

- Echols, N., D. Milburn, and M. Gerstein. 2003. MolMovDB: analysis and visualization of conformational change and structural flexibility. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:478–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edman, K., P. Nollert, A. Royant, H. Belrhali, E. Pebay-Peyroula, J. Hajdu, R. Neutze, and E. M. Landau. 1999. High-resolution X-ray structure of an early intermediate in the bacteriorhodopsin photocycle. Nature. 401:822–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Facciotti, M. T., V. S. Cheung, D. Nguyen, S. Rouhani, and R. M. Glaeser. 2003. Crystal structure of the bromide-bound D85S mutant of bacteriorhodopsin: principles of ion pumping. Biophys. J. 85:451–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Facciotti, M. T., S. Rouhani, F. T. Burkard, F. M. Betancourt, K. H. Downing, R. B. Rose, G. McDermott, and R. M. Glaeser. 2001. Structure of an early intermediate in the M-state phase of the bacteriorhodopsin photocycle. Biophys. J. 81:3442–3455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, R., E. Nachliel, and M. Gutman. 2003. The role of small intraprotein cavities in the catalytic cycle of bacteriorhodopsin. Biophys. J. 85:886–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi, S., E. Tajkhorshid, and K. Schulten. 2002. Structural changes during the formation of early intermediates in the bacteriorhodopsin photocycle. Biophys. J. 83:1281–1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi, S., E. Tajkhorshid, and K. Schulten. 2003. Molecular dynamics simulation of bacteriorhodopsin's photoisomerization using ab initio forces for the excited chromophore. Biophys. J. 85:1440–1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey, W., A. Dalke, and K. Schulten. 1996. VMD—visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 14:33–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandori, H., Y. Yamazaki, Y. Shichida, J. Raap, J. Lugtenburg, M. Belenky, and J. Herzfeld. 2001. Tight Asp85-Thr89 association during the pump switch of bacteriorhodopsin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:1571–1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klink, B. U., R. Winter, M. Engelhard, and I. Chizhov. 2002. Pressure dependence of the photocycle kinetics of bacteriorhodopsin. Biophys. J. 83:3490–3498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanyi, J. K., and B. Schobert. 2002. Crystallographic structure of the retinal and the protein after deprotonation of the Schiff base: the switch in the bacteriorhodopsin photocycle. J. Mol. Biol. 321:727–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanyi, J. K., and B. Schobert. 2003. Mechanism of proton transport in bacteriorhodopsin from crystallographic structures of the K, L, M1, M2, and M2′ intermediates of the photocycle. J. Mol. Biol. 328:439–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luecke, H., and J. K. Lanyi. 2003. Structural clues to the mechanism of ion pumping in bacteriorhodopsin. Adv. Protein Chem. 63:111–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luecke, H., B. Schobert, J.-P. Cartailler, H.-T. Richter, A. Rosengarth, R. Needleman, and J. K. Lanyi. 2000. Coupling photoisomerization of retinal to directional transport in bacteriorhodopsin. J. Mol. Biol. 300:1237–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luecke, H., B. Schobert, H.-T. Richter, J.-P. Cartailler, and J. K. Lanyi. 1999a. Structural changes in bacteriorhodopsin during ion transport at 2 angstrom resolution. Science. 286:255–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luecke, H., B. Schobert, H.-T. Richter, J.-P. Cartailler, and J. K. Lanyi. 1999b. Structure of bacteriorhodopsin at 1.55 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 291:899–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagle, J. F., and S. Tristram-Nagle. 2000. Structure of lipid bilayers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1469:159–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neutze, R., E. Pebay-Peyroula, K. Edman, A. Royant, J. Navarro, and E. M. Landau. 2002. Bacteriorhodopsin: a high-resolution structural view of vectorial proton transport. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1565:144–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oesterhelt, D., and W. Stoeckenius. 1971. Rhodopsin-like protein from the purple membrane of Halobacterium halobium. Nat. New Biol. 233:149–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oka, T., N. Yagi, F. Tokunaga, and M. Kataoka. 2002. Time-resolved x-ray diffraction reveals movement of F helix of D96N bacteriorhodopsin during M-MN transition at neutral pH. Biophys. J. 82:2610–2616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onufriev, A., A. Smondyrev, and D. Bashford. 2003. Affinity changes driving unidirectional proton transport in the bacteriorhodopsin photocycle. J. Mol. Biol. 332:1183–1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrache, H. I., S. E. Feller, and J. F. Nagle. 1997. Determination of component volumes of lipid bilayers from simulations. Biophys. J. 72:2237–2242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radzwill, N., K. Gerwert, and H. J. Steinhoff. 2001. Time-resolved detection of transient movement of helices F and G in doubly spin-labeled bacteriorhodopsin. Biophys. J. 80:2856–2866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Réat, V., H. Patzelt, M. Ferrand, C. Pfister, D. Oesterhelt, and G. Zaccai. 1998. Dynamics of different functional parts of bacteriorhodopsin: H-2H labeling and neutron scattering. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:4970–4975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouhani, S., J.-P. Cartailler, M. T. Facciotti, P. Walian, R. Needleman, J. K. Lanyi, R. M. Glaeser, and H. Luecke. 2001. Crystal structure of the D85S mutant of bacteriorhodopsin: model of an O-like photocycle intermediate. J. Mol. Biol. 313:615–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux, B., M. Nina, R. Pomès, and J. C. Smith. 1996. Thermodynamic stability of water molecules in the bacteriorhodopsin proton channel: a molecular dynamics free energy perturbation study. Biophys. J. 71:670–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royant, A., K. Edman, T. Ursby, E. Pebay-Peyroula, E. M. Landau, and R. Neutze. 2000. Helix deformation is coupled to vectorial proton transport in the photocycle of bacteriorhodopsin. Nature. 406:645–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sass, H. J., G. Büldt, R. Gessenich, D. Hehn, D. Neff, R. Schlesinger, J. Berendzen, and P. Ormos. 2000. Structural alterations for proton translocation in the M state of wild-type bacteriorhodopsin. Nature. 406:649–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schobert, B., L. S. Brown, and J. K. Lanyi. 2003. Crystallographic intermediates of structures of the M and N bacteriorhodopsin: assembly of a hydrogen-bonded chain of water molecules between Asp-96 and the retinal Schiff base. J. Mol. Biol. 330:553–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son, H. S., I. D. Kerr, and M. S. P. Sansom. 2000. Simulation studies on bacteriorhodopsin bundle of transmembrane alpha segments. Eur. Biophys. J. 28:663–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son, H. S., and M. S. P. Sansom. 2000. Simulation studies on bacteriorhodopsin alpha-helices. Eur. Biophys. J. 28:674–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y. F., J. J. Mao, and M. R. Gunner. 2003. Calculation of proton transfers in bacteriorhodopsin bR and M intermediates. Biochemistry. 42:9875–9888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stock, D., A. G. W. Leslie, and J. E. Walker. 1999. Molecular architecture of the rotary motor in ATP synthase. Science. 286:1700–1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoeckenius, W., R. H. Lozier, and R. A. Bogomolni. 1979. Bacteriorhodopsin and related pigments of halobacteria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 505:215–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramaniam, S., and R. Henderson. 2000a. Crystallographic analysis of protein conformational changes in the bacteriorhodopsin photocycle. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1460:157–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramaniam, S., and R. Henderson. 2000b. Molecular mechanism of vectorial proton translocation by bacteriorhodopsin. Nature. 406:653–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramaniam, S., M. Lindahl, P. Bullough, A. R. Faruqi, J. Tittor, D. Oesterhelt, L. Brown, J. K. Lanyi, and R. Henderson. 1999. Protein conformational changes in the bacteriorhodopsin photocycle. J. Mol. Biol. 287:145–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajkhorshid, E., J. Baudry, K. Schulten, and S. Suhai. 2000. Molecular dynamics study of the nature and origin of retinal's twisted structure in bacteriorhodopsin. Biophys. J. 78:683–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teeter, M. M., and D. A. Case. 1990. Harmonic and quasiharmonic descriptions of crambin. J. Phys. Chem. 94:8091–8097. [Google Scholar]

- Tittor, J., S. Paula, S. Subramaniam, J. Heberle, R. Henderson, and D. Oesterhelt. 2002. Proton translocation by bacteriorhodopsin in the absence of substantial conformational changes. J. Mol. Biol. 319:555–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weik, M., G. Zaccai, N. A. Dencher, D. Oesterhelt, and T. Hauss. 1998. Structure and hydration of the M-state of the bacteriorhodopsin mutant D96N studied by neutron diffraction. J. Mol. Biol. 275:625–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White, S., and W. Wimley. 1999. Membrane protein folding and stability: physical principles. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 28:319–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]