Abstract

The membrane interactions and position of a positively charged and highly aromatic peptide derived from a secretory carrier membrane protein (SCAMP) are examined using magnetic resonance spectroscopy and several biochemical methods. This peptide (SCAMP-E) is shown to bind to membranes containing phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate, PI(4,5)P2, and sequester PI(4,5)P2 within the plane of the membrane. Site-directed spin labeling of the SCAMP-E peptide indicates that the position and structure of membrane bound SCAMP-E are not altered by the presence of PI(4,5)P2, and that the peptide backbone is positioned within the lipid interface below the level of the lipid phosphates. A second approach using high-resolution NMR was used to generate a model for SCAMP-E bound to bicelles. This approach combined oxygen enhancements of nuclear relaxation with a computational method to dock the SCAMP-E peptide at the lipid interface. The model for SCAMP generated by NMR is consistent with the results of site-directed spin labeling and places the peptide backbone in the bilayer interfacial region and the aromatic side chains within the lipid hydrocarbon region. The charged side chains of SCAMP-E lie well within the interface with two arginine residues lying deeper than a plane defined by the position of the lipid phosphates. These data suggest that SCAMP-E interacts with PI(4,5)P2 through an electrostatic mechanism that does not involve specific lipid-peptide contacts. This interaction may be facilitated by the position of the positively charged side chains on SCAMP-E within a low-dielectric region of the bilayer interface.

INTRODUCTION

Phosphatidylinositol is a membrane phospholipid that has a number of different phosphorylated forms, each of which plays a critical role in mediating cell-signaling events (Cremona and De Camilli, 2001; Czech, 2000; DiNitto et al., 2003; Hurley and Meyer, 2001; Martin, 2001; Overduin et al., 2001; Simonsen et al., 2001; Toker, 1998). Among these polyphosphoinositides, phosphatidylinositol 4, 5-bisphosphate (PI(4,5)P2) is the most abundant and the best characterized. PI(4,5)P2 is the precursor for three other signaling molecules, inositol trisphosphate (IP3), diacylglycerol (DAG), and phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate (PI(3,4,5)P3), but PI(4,5)P2 also acts directly as a second messenger regulating numerous events including enzyme activation, ion channel function (Runnels et al., 2002; Wu et al., 2002), membrane trafficking (Cremona and De Camilli, 2001; Martin, 2001; Simonsen et al., 2001), and membrane-cytoskeletal interactions (Raucher et al., 2000; Sechi and Wehland, 2000; Sheetz, 2001).

PI(4,5)P2 regulates many diverse functions in response to intermittent cellular signals. To achieve this regulation it has been proposed that a significant fraction of the PI(4,5)P2 within the membrane is bound to proteins, which then release PI(4,5)P2 locally in response to specific cellular signals (Caroni, 2001; McLaughlin et al., 2002). There is good evidence that proteins may bind and sequester PI(4,5)P2 through an electrostatic mechanism. In this case, highly positively charged regions of proteins that are localized at the membrane interface interact electrostatically with PI(4,5)P2 (which has a valence of from −3 to −4 at neutral pH) to alter the lateral heterogeneity of PI(4,5)P2 (Gambhir et al., 2004; McLaughlin et al., 2002; Rauch et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2001, 2002, 2004).

The highly charged effector domain of the myristoylated alanine-rich C-kinase substrate (MARCKS-ED) is an example of a membrane-associated protein segment that binds and sequesters PI(4,5)P2 within the plane of the membrane through an electrostatic mechanism (Gambhir et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2004). A peptide derived from the MARCKS-ED binds to membranes containing PI(4,5)P2 with high affinity (Wang et al., 2001), and inhibits the activity of phospholipase C (PLC), an enzyme that hydrolyzes PI(4,5)P2 at the membrane interface (Wang et al., 2002). EPR measurements using a spin-labeled derivative of PI(4,5)P2 indicate that the MARCKS-ED binds ∼3 molecules of PI(4,5)P2, and site-directed spin labeling of the MARCKS-ED peptide suggests that neither specific van der Waals contacts nor hydrogen bonds are required for the peptide-PI(4,5)P2 interaction (Rauch et al., 2002). There appear to be two mechanisms to reverse the binding of PI(4,5)P2 by MARCKS. In the first, MARCKS is phosphorylated within its effector domain segment by protein kinase C, thereby reducing its positive charge and releasing PI(4,5)P2. In the second, the presence of high intracellular Ca2+ activates Ca2+-calmodulin, which binds the effector domain segment of MARCKS and removes it from the membrane interface.

The MARCKS-ED (residues 151–175) is a highly charged segment containing 13 positively charged residues and five phenylalanines. A peptide corresponding to the MARKCKS-ED is positioned at the membrane interface as an extended structure, with its five phenylalanine residues buried 5−10 Å below the level of the lipid phosphates (Ellena et al., 2003; Qin and Cafiso, 1996; Zhang et al., 2003). The position of this peptide at the membrane interface appears to be important in its ability to sequester PI(4,5)P2. When the five phenylalanine residues of the MARCKS-ED peptide are replaced by alanine residues, the peptide binds but no longer penetrates the membrane interface (Victor et al., 1999); in addition, the ability of this peptide to sequester PI(4,5)P2 is diminished (Gambhir et al., 2004). Thus, aromatic residues in the MARCKS-ED may function to position this peptide at the membrane interface. At the time of this study, direct information on the position of the positively charged residues in the MARCKS-ED has not been obtained. A number of other charged peptides also appear to bind and sequester PI(4,5)P2, and the ability of these peptides to sequester PI(4,5)P2 generally increases with the amount of charge and the number of aromatic residues in the sequence (Wang et al., 2002). However, there is little structural information on the membrane interactions made by these peptides.

In this work, we investigate the PI(4,5)P2 binding and membrane position of a basic, aromatic 11-residue peptide derived from a secretory carrier membrane protein (SCAMP). SCAMPs are membrane proteins with four membrane-spanning helical segments (Hubbard et al., 2000) that function in membrane fusion during exocytosis (Fernandez-Chacon et al., 1999; Guo et al., 2002; Liu et al., 2002). The SCAMP-derived peptide examined here, CWYRPIYKAFR or E-peptide, is derived from a short, highly conserved cytoplasm-facing segment linking the second and third transmembrane helices of SCAMP2 (Hubbard et al., 2000). This peptide is a sequence-specific and late-acting inhibitor of exocytosis in permeabilized mast cells and neuroendocrine (PC12) cells (Guo et al., 2002; Liu et al., 2002). Using an electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR)-based assay and a measurement of PLC activity on monolayers, we provide evidence that SCAMP-E peptide has the capacity to bind and sequester PI(4,5)P2 within the plane of the bilayer. SDSL is used to position the peptide in the membrane interface and suggests that the interactions with PI(4,5)P2 are electrostatic in origin. We also utilize high-resolution NMR to generate a model for the position of the SCAMP-E peptide in the lipid interface. In this model the aromatic side chains of the peptide are located in the lipid hydrocarbon region and the charged amino acid side chains lie at or deeper than the level of the lipid phosphates. The deep position of the charged residues of this peptide is consistent with an electrostatic mechanism for the sequestration of PI(4,5)P2 by SCAMP-E.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Materials

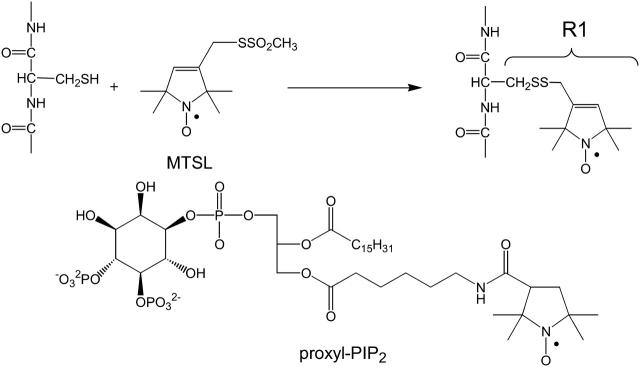

All phospholipids were obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). A number of peptides based on the human SCAMP-E sequence were synthesized and are listed in Table 1. The human SCAMP-E peptide and two structural variants with residues switched were synthesized and purified by the Biomolecular Research Facility at the University of Virginia, and the identity of each peptide was confirmed by mass spectrometry. These peptides were blocked at the C-terminus, but had a free N-terminus, so that the valence was +4 at neutral pH. The native SCAMP-E sequence was also synthesized along with two analogs with cysteines at positions 6 and 9 (Ac-SWYRPCYKAFR-NH and Ac-SWYRPIYKCFR-NH) using a Gilson automated peptide synthesizer (AMS 422; Gilson, Middletown, WI) as described previously (Hubbard et al., 2000). Each of these peptides were acetylated at the N-terminus and had a valence of +3 (loss of the N-terminal charge on this peptide did not significantly alter the ability of this peptide to interact with proxyl-PI(4,5)P2). These peptides were spin-labeled (Scheme 1) with the sulfhydryl reactive methanethiosulfonate spin label (MTSL), (1-oxy-3-methanesulfonylthiomethyl-2,2,5,6-tetramethyl-2,5-dihydro-1H pyrroline), which was purchased from Toronto Research Chemicals (Toronto, Ontario, Canada). A radiolabeled version of SCAMP-E was produced by derivatizing the N-terminal cysteine of purified SCAMP-E peptide with 3H-NEM as described previously (Arbuzova et al., 2000) and repurified by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). The identity of all peptides was confirmed by mass spectrometry, and each had a purity in excess of 97% as determined by HPLC and in-line detection by ultraviolet spectrometry of the peptide backbone at 210 nm. A spin-labeled derivative of PI(4,5)P2, proxyl-PI(4,5)P2 (Scheme 1), was obtained from Echelon Biosciences (Salt Lake City, UT) (Prestwich, 2004).

TABLE 1.

SCAMP-E peptides synthesized

| Peptide | Sequence |

|---|---|

| Human SCAMP-E | NH2-CWYRPIYKAFR-NH or Ac-CWYRPIYKAFR-NH |

| E peptide with 6/11 switch | NH2-CWYRPRYKAFI-NH |

| E peptide with 4/5 and 9/10/11 switch | NH2-CWYPRIYKRAF-NH |

| 3H labeled SCAMP-E | NH2-(Cys-NEM)WYRPIYKAFR-NH |

| C1R1 | Ac-(R1)WYRPIYKAFR-NH |

| I6R1 | Ac-SWYRP(R1)YKAFR-NH |

| A9R1 | Ac-SWYRPIYK(R1)FR-NH |

SCHEME 1.

Lipid vesicle preparation

Lipid vesicles were formed from either palmitoyloleoylphosphatidylcholine (PC) and mixtures of POPC with palmitoyloleoylphosphatidylserine (PS) and/or PI(4,5)P2. Lipid vesicles were produced by mixing the appropriate lipids from stock solutions in chloroform. The chloroform was removed by vacuum desiccation, and the resulting lipid film was hydrated in a buffer containing 100 mM KCl, 10 mM 3-morpholinopropanesulfonic acid (MOPS), pH 7.0. The lipid mixture was taken through five freeze-thaw cycles, and unilamellar vesicles were produced by extrusion of the mixture through 1000-Å polycarbonate filters (Poretics, Livermore, CA) using a LiposoFast extruder (Avestine, Ottawa, Ontario). In the experiments described here, the spin-labeled proxyl-PI(4,5)P2 was incorporated into the outer membrane leaflet by adding the vesicle solution to a dried film of proxyl-PI(4,5)P2. This procedure was shown previously to quantitatively incorporate proxyl-PI(4,5)P2 into the outer leaflet of the vesicle bilayer (Rauch et al., 2002). Either unlabeled or spin-labeled versions of the SCAMP-E peptide were added directly to preformed lipid vesicle suspensions from an aqueous stock solution of peptide.

Centrifugation binding measurements

Membrane binding was determined by the use of 3H-NEM SCAMP-E peptide using a centrifugation assay described previously (Wang et al., 2002) and was carried out by Jiyao Wang in the laboratory of Stuart McLaughlin. The levels of peptide in the supernatant and pellet fraction were determined by scintillation counting and used to calculate the fraction of membrane-bound peptide, FB. The binding was then expressed as a reciprocal molar binding constant K as given by:

|

(1) |

where [L] represents the accessible lipid concentration. We assume that SCAMP-E does not cross the bilayer and take [L] to be half the total lipid concentration. As described elsewhere (Buser and McLaughlin, 1998), it is important that the peptide does not significantly alter the total surface charge under the conditions of the binding titration. Hence, care was taken to ensure that the experiment was carried out under conditions where the accessible lipid concentration greatly exceeded the bound peptide concentration.

PLC monolayer assay

The activity of either PLC-δ1 or PLC-β was measured on lipid monolayers as described previously (Wang et al., 2002) and was carried out by Jiyao Wang in the laboratory of Stuart McLaughlin. Briefly, the SCAMP-E peptide was added to the subphase at the indicated concentrations, and the levels of 3H-IP3, which resulted from the PLC hydrolysis of 3H-PI(4,5)P2 in the monolayer, were measured in the subphase by scintillation counting.

EPR spectroscopy

EPR spectra for either proxyl-PI(4,5)P2 or spin-labeled SCAMP-E peptides, were obtained at X-band from ∼5 μL of sample using a Varian E-line century series spectrometer fitted with a MITEQ microwave amplifier (Varian, Hauppauge, NY) and a two-loop, one-gap resonator (Medical Advances, Milwaukee, WI). Nonsaturated EPR spectra were obtained using a microwave power of ∼2 mW or less and a modulation amplitude of 1 G peak-to-peak.

EPR spectroscopy was used to determine the interaction between proxyl-PI(4,5)P2 and several SCAMP-E peptides listed in Table 1, as described previously (Rauch et al., 2002). Briefly, the peptide was added in steps from a concentrated stock solution to 50–100 μL of a 20-mM lipid vesicle suspension (0.25–0.5% proxyl-PI(4,5)P2) while the first derivative peak-to-peak amplitude of the central proxyl nitroxide resonance, A(0), was recorded. The EPR spectrum of proxyl-PI(4,5)P2 in the presence of the SCAMP-E peptide is a sum of EPR signals from free lipid and lipid bound to the peptide. As discussed below, the fraction of bound proxyl-PI(4,5)P2 may be determined from the value of A(0).

EPR power saturation measurements

Power saturation measurements on spin-labeled SCAMP-E peptides were used to determine the depth of the nitroxide label from the level of the lipid phosphate (Altenbach et al., 1994). Power saturation was performed as described previously (Rauch et al., 2002) using gas permeable TPX capillary tubes (Medical Advances, Milwaukee WI). The parameter P1/2 was measured under three sets of conditions: in the presence of Air (20% O2), N2, or N2 + 20 mM aqueous nickel (II) ethylenediaminediacetic acid (NiEDDA), as described previously (Victor and Cafiso, 2001). The values of  or

or  were then determined from the difference in P1/2 values in the presence and absence of either O2 or NiEDDA, respectively. For each sample a depth parameter, Φ, was determined from the values of ΔP1/2 according to

were then determined from the difference in P1/2 values in the presence and absence of either O2 or NiEDDA, respectively. For each sample a depth parameter, Φ, was determined from the values of ΔP1/2 according to

|

(2) |

The value of Φ is related to the local concentrations of O2 and NiEDDA, which vary as a function of depth in the lipid bilayer. As a result, Φ provides an estimate of the nitroxide depth in the lipid bilayer (Altenbach et al., 1994). A previously defined calibration curve was used to estimate the position of the nitroxide labels on SCAMP-E in either PC/PS- or PC/PS/PI(4,5)P2-containing membranes (Frazier et al., 2002).

Analysis of EPR binding data

The 1:1 binding of SCAMP-E to proxyl-PI(4,5)P2 was analyzed in a manner similar to that described previously for the equilibrium

|

(3) |

The apparent association constant, Ka, for 1:1 binding is given by

|

(4) |

where [M-PI(4,5)P2] is the concentration of macromolecule: PI(4,5)P2 complex, [PI(4,5)P2] is the concentration of free PI(4,5)P2, and [M] is the concentration of macromolecule in aqueous solution (Wang et al., 2001). In addition, if [M]T and [PI(4,5)P2]T represent the total concentrations of macromolecule and PI(4,5)P2, respectively, we may write

|

(5) |

|

(6) |

The solution of Eqs. 4–6 yields a quadratic that can be used to predict the 1:1 binding as a function of the concentration of SCAMP-E, neomycin, or other PI(4,5)P2 binding species. This expression can be used to predict the amplitude of the central EPR resonance amplitude, A(0), as a function of added macromolecule. The EPR spectrum is a simple sum of EPR spectra from the free and bound proxyl-PI(4,5)P2 as a result the magnitude of A(0) may be written as

|

(7) |

where Af and Ab represent the intrinsic amplitudes of free and macromolecule-associated proxyl-PI(4,5)P2. Equation 7 was used in combination with Eqs. 4–6 to determine the 1:1 binding behavior of proxyl-PI(4,5)P2.

Bicelle and peptide samples for NMR spectroscopy

Proton NMR chemical shift assignments for SCAMP-E (N-acetylated version) were obtained using a solution of 3 mM SCAMP-E, 10% D2O, pH 4.2. The SCAMP-E peptide does not produce resolvable 1H resonances when bound to lipid bilayers, and a bicelle system was chosen that contained physiologically relevant levels of negatively charged lipid. The bicelle samples containing SCAMP-E were formed by preparing a concentrated solution of DCPC (dicaproylphosphatidylcholine) in H2O in a glove bag filled with dry nitrogen. Appropriate amounts of dry dimyristoylphosphatidylcholine (DMPC), dimyristoylphosphatidylglycerol (DMPG), and SCAMP-E were then added to the DCPC solution followed by an appropriate amount of 1 M NaCl in D2O. The volume was adjusted with H2O to 90% of the final volume, the pH was adjusted to 5.5, and the sample was diluted to the final volume. The mixture was freeze-thawed five times and the pH checked. The sample contained 4 mM SCAMP-E, 150 mM NaCl, 0.15 w/v bicelles, 10% (v/v) D2O, pH 5.5. The lipid content of the bicelles was 67 mol % DCPC, 20 mol % DMPG, 13 mol % DMPC.

Samples for spin-lattice relaxation experiments were degassed by using the freeze-pump-thaw method and then equilibrated with 9 atm of O2 or N2.

NMR spectroscopy

NMR spectroscopy was performed using Varian UnityPlus and Inova 500 MHz spectrometers at 37°C. The amide and aromatic regions of the one-dimensional 1H spectra of bicelle-bound SCAMP-E peptide were selectively excited using e-SNOB (selective excitation for biomedical applications) pulses (Kupce et al., 1995). The PENCE (pulse with enhanced selectivity) sequence containing an r-SNOB selective pulse (Kupce et al., 1995) was used to selectively excite the 6.5- to 10-ppm spectral region in ω2-selective total correlation spectroscopy (TOCSY) (mixing times 30 ms, 60 ms, and 100 ms) and nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy (NOESY) (mixing times 40 ms, 75 ms, 150 ms, and 250 ms) experiments (Seigneuret and Levy, 1995) for SCAMP-E in bicelles. Standard pulse sequences from Varian were used to obtain the TOCSY (mixing times 50 ms, 100 ms, and 150 ms) and rotating-frame NOESY (ROESY) (mixing times 150 ms and 200 ms) spectra of SCAMP-E in solution. The inversion recovery method was used for spin-lattice relaxation measurements. Spin-lattice relaxation rates due to the presence of molecular oxygen (R1para) were obtained by measuring the relaxation rate (R1) for a sample which was equilibrated with 9 atm of N2. The sample was then degassed and equilibrated with 9 atm of O2 and the R1 experiment was repeated. The value of R1para was obtained by subtracting R1 for samples equilibrated with N2 from R1 for the same samples equilibrated with O2.

Determining the position of bicelle-bound peptide from oxygen paramagnetic enhancements of 1H relaxation

As described previously, the values of R1para vary as a function of depth within a lipid bicelle and reflect the increase in oxygen solubility within the hydrocarbon (Ellena et al., 2002; Luchette et al., 2001; Prosser et al., 2000, 2001; Windrem and Plachy, 1980). A model for the position of SCAMP-E at the interface was generated from the values of R1para for SCAMP-E bound to bicelles in combination with lipid proton depths, lipid R1para values and a model for the structure of SCAMP-E. Membrane-bound SCAMP-E appears to be at least partially helical (Hubbard et al., 2000), and an α-helical model of SCAMP-E was constructed and the coordinates for each resolvable SCAMP-E proton were obtained. The intrabilayer position of SCAMP-E was then defined by its depth and three Euler angles. The relationship between the value of R1para and bilayer depth was defined empirically as

|

(8) |

where the values of A, B, C, and D are constants that define the bulk values of R1para and the position of the curve. The position of SCAMP-E and the parameters that define the hyperbolic tangent function were then fit to the values of R1para using lipid values of R1para as calibration points.

The hyperbolic tangent function (Eq. 8) was chosen because it describes the distance behavior of the oxygen-based EPR determined depth parameter given in Eq. 2 (Frazier et al., 2002). The EPR depth parameter Φ is dependent on the local concentration of O2 (Altenbach et al., 1994), as is the value of R1para (Ellena et al., 2002; Prosser et al., 2001). The effects of nuclear motion have little effect upon R1para, because R1para is dominated by the very large electron spin-lattice relaxation rate (Teng et al., 2001).

As indicated above, the values of R1para for the lipid protons were used as calibration points. Depths for the lipid headgroup and glycerol protons were estimated by constructing a bilayer containing the A and B forms of the DMPC crystal structure (Pearson and Pascher, 1979) and measuring the average distance (for the two crystal forms) from the lipid protons to a plane defined by the lipid phosphorus atoms. The same approach was taken for the acyl chain protons except that the effects of chain order on distance were included (Salmon et al., 1987), using the acyl chain order parameters for bicellar DMPC at 40°C (Vold and Prosser, 1996).

RESULTS

PI(4,5)P2 enhances the binding of SCAMP-E peptide to membranes

Membrane binding affinities were measured for the SCAMP-E peptide to membrane vesicles composed of PC, PC + 1 mol % PI(4,5)P2, and PC + 3 mol % PI(4,5)P2. Shown in Fig. 1 are plots of the fraction of SCAMP-E bound to membranes as a function of lipid concentration measured using a 3H-labeled peptide. The solid lines represent the best fits through the data as defined by Eq. 1 and yield the reciprocal molar lipid binding constant of the peptide. From these data, the affinity of SCAMP-E to PC membranes is found to be 1.3 × 102 M−1, close to the value reported previously using a spin-labeled E-peptide and EPR spectroscopy (Hubbard et al., 2000). When PC membranes contain 1 mol % PI(4,5)P2 the affinity of SCAMP-E increases ∼6-fold, and when the membranes contain 3% PI(4,5)P2 the membrane affinity is ∼100-fold larger. The binding increase seen in the presence of PI(4,5)P2 is likely to result from the Coulombic interaction of positively charged residues on SCAMP-E with the negatively charged membrane surface. The zeta potential of bilayers composed of PC and 3 mol % PI(4,5)P2 is ∼−20 mV (Wang et al., 2001), and from the Boltzmann relation a 20-fold enhancement in binding would be expected for a point charge of valence +4 from this potential. Thus, the binding increase observed here represents a slight increase over what would be expected from a purely nonspecific Coulombic interaction with a uniform membrane charge distribution. This increase may arise from a localized electrostatic effect or discreetness-of-charge effects as discussed previously for the MARCKS-ED (Wang et al., 2002).

FIGURE 1.

Membrane binding of 3H-NEM-SCAMP E-peptide (+4) to PC vesicles (○), 1% PI(4,5)P2 in PC (▴), and 3% PI(4,5)P2 in PC (•) as a function of the concentration of accessible lipid. The reciprocal molar binding constants for PC, 1% PI(4,5)P2, 3% PI(4,5)P2 are 130, 8.9 × 102, and 1.4 × 104 M−1, respectively. The radiolabeled peptide is at a concentration of 40 nM. The membrane vesicles are extruded into a buffer of 100 mM KCl, 1 mM MOPS, pH 7.0.

The SCAMP-E peptide binds to proxyl-PI(4,5)P2

Shown in Fig. 2 A are EPR spectra of the spin-labeled PI(4,5)P2 analog, proxyl-PI(4,5)P2, incorporated into PC bilayers in the presence and absence of SCAMP-E peptide. The lineshape recorded in the absence of peptide (gray line, Fig. 2 A) is identical to that reported previously for proxyl-PI(4,5)P2 in PC (Rauch et al., 2002) and indicates that the probe is incorporated into the vesicle membrane. This EPR spectrum results from a nitroxide having an effective correlation time of ∼1.5–2 ns. At least one component of the motion of this probe is likely the rapid nanosecond rotational diffusion about the long axis of the lipid. When excess SCAMP-E peptide (black line, Fig. 2 A) is added to the proxyl-PI(4,5)P2/PC sample, the EPR spectrum broadens and decreases in amplitude, indicating that there is an interaction between the peptide and the lipid probe. This broadening in the EPR spectrum indicates that the correlation time of the nitroxide on proxyl-PI(4,5)P2 has increased and is ∼2–3 ns in the presence of SCAMP-E. Similar lineshape changes for proxyl-PI(4,5)P2 in PC were seen upon the addition of either neomycin or the PH domain from PLC-δ1, two molecules that are known to bind PI(4,5)P2 (Rauch et al., 2002). The changes in lineshape seen in Fig. 2 A are likely to result from a decrease in the rotational diffusion rate of proxyl-PI(4,5)P2 that would take place upon association of the SCAMP-E peptide with the phosphoinositol headgroup. Fig. 2 B is a plot the central EPR line amplitude from proxyl-PI(4,5)P2 as a function of the addition of SCAMP-E peptide. The solid line in Fig. 2 B represents the best fit to the EPR amplitudes using the 1:1 binding model described by Eqs. 3–7, and this fit yields an association binding constant (Eq. 4) for the interaction of SCAMP-E with proxyl-PI(4,5)P2 of 10−4 M−1.

FIGURE 2.

(A) EPR spectra of proxyl-PI(4,5)P2 in the absence (gray trace) and presence (black trace) of ∼1 mM SCAMP-E peptide. The membrane vesicles contain PC with ∼0.25 mol % proxyl-PI(4,5)P2. (B) Titration of the central EPR resonance of proxyl-PI(4,5)P2 as a function of the concentration of added SCAMP-E peptide. The total proxyl-PI(4,5)P2 concentration is 50 μM in PC vesicles at a lipid concentration of 20 mM. The solid line represents a nonlinear least squares fit through the data using Eqs. 3–6, assuming a 1:1 stoichiometry, and yields a value for Ka of 3 × 104 M−1.

In addition to the native SCAMP-E peptide (CWYRPIYKAFR), we tested two analogs of SCAMP-E (See Table 1) to determine whether they also interacted with proxyl-PI(4,5)P2. In these two peptides, the amino acid composition was identical to that of the native peptide except that either residues 6 and 11 or residues 4 and 5 and 9, 10, and 11 had been switched. These two scrambled peptides produced nearly identical results to those shown in Fig. 2 for the native SCAMP-E peptide, indicating that the specific order of the positively charged and aromatic residues was not critical to the interaction with the labeled PI(4,5)P2.

The cytoplasmic surface of a plasma membrane typically contains a substantial fraction of monovalent negatively charged lipid such as PS. To determine whether negatively charged lipids might interfere with the interaction between proxyl-PI(4,5)P2 and the native SCAMP-E peptide, the experiment shown in Fig. 2 was repeated in membranes composed of PC/PS (70:30). In the presence of negatively charged lipid, virtually identical results to those shown in Fig. 2 B were obtained, indicating that the presence of monovalent negatively charged lipids do not significantly alter the interaction between SCAMP-E and proxyl-PI(4,5)P2.

SCAMP-E peptide inhibits PLC-β and PLC-δ1 activity on monolayers

The data shown in Fig. 1 indicate that the SCAMP-E peptide prefers to bind to membranes containing PI(4,5)P2, and the data in Fig. 2 indicate that SCAMP-E directly interacts with the proxyl-PI(4,5)P2 headgroup in the membrane. To further test for a SCAMP-E peptide-PI(4,5)P2 interaction, the effect of the SCAMP-E peptide on the activity of both PLC-δ1 and PLC-β on monolayer surfaces was measured. If SCAMP-E has a greater affinity for PI(4,5)P2 than the active site of these enzymes, the peptide should decrease the rate at which these PLCs are able to hydrolyze PI(4,5)P2 on a monolayer surface. Shown in Fig. 3 are plots of the fraction of radiolabeled PI(4,5)P2 hydrolyzed by either PLC-δ1 or PLC-β in the absence or presence of SCAMP-E peptide. For either PLC isoform, addition of 1 μM SCAMP-E to the monolayer subphase produces a >90% reduction in the rate of enzymatic activity. This inhibition by SCAMP-E suggests that the peptide has the capacity to bind and sequester PI(4,5)P2, making the lipid inaccessible to the active site on either PLC isoform.

FIGURE 3.

Effect of the addition of the SCAMP-E peptide on the hydrolysis of PI(4,5)P2 on monolayers by either (A) PLC-δ1 at peptide concentrations of zero (•), 1 μM (▴), and 10 μM (○); or (B) PLC-β at peptide concentrations of zero (•), 100 nM (▴), and 1 μM (○).

Site-directed spin labeling indicates that SCAMP-E peptide binds below the level of the lipid phosphates and does not change position or structure in the presence of PI(4,5)P2

Site-directed spin labeling (SDSL) was used to determine the position of SCAMP-E in the membrane interface and determine whether the presence of PI(4,5)P2 in the membrane altered the position or structure of SCAMP-E. Previous work indicated that the SCAMP-E peptide has a random structure in solution, but assumes an ∼30% helical structure upon membrane association (Hubbard et al., 2000). The native peptide and two mutant peptides (see Table 1) having single cysteine residues (I6C and A9C) were modified with the MTSL. Shown in Fig. 4 are the EPR spectra of the R1 label at positions 1, 6, and 9 for the SCAMP-E peptide fully bound to vesicles composed of PC, PC/PS, or PC/PS/PI(4,5)P2. In each case the spectra have correlation times of 2–3 ns and are similar to other EPR spectra for R1 side chains on peptides that are positioned within the membrane interface. The EPR spectrum at position 1 arises from a label having slightly more motion than those at positions 6 and 9 (there is a ∼20% difference in correlation times). For each label, the spectra in PC, PC/PS (75:25), or PC/PS/PI(4,5)P2 (73:22:5) are remarkably similar. The similarity of these spectra and the relatively mobile lineshapes indicate that there are no dramatic changes in structure of the peptide or specific tertiary contacts made between the labeled peptide side chains and PI(4,5)P2.

FIGURE 4.

EPR spectra of spin-labeled derivatives of the SCAMP-E peptide when fully bound to PC, PC/PS (75:25), or PC/PS/PI(4,5)P2 (73:22:5) membrane vesicles. The spin-labeled side chain when placed at position 1 has an apparent rotational correlation time of ∼2 ns. At positions 6 and 9 the apparent rotational correlation times are slightly longer and have values of ∼2.4 ns. The lineshapes are virtually unchanged in the presence of PI(4,5)P2, indicating that the spin-labeled side chain does not experience a change in tertiary environment in the presence of PI(4,5)P2. This result is consistent with the hypothesis that the interaction between the SCAMP-E peptide and PI(4,5)P2 is mediated largely by electrostatic interactions.

To determine the membrane position of the spin-labeled side chains relative to the lipid phosphates, the EPR spectra of spin-labeled SCAMP-E peptides bound to PC/PS or PC/PS/PI(4,5)P2 vesicles were power saturated (see Methods). Shown in Table 2 are the distances obtained for the R1 side chain relative to the lipid phosphate. Each label sits at a position 7–9 Å below the level of the lipid phosphates on the hydrocarbon side of a plane defined by the carbonyl carbons. The depths of the R1 labels are unchanged within experimental error in the presence of PI(4,5)P2. As discussed previously, these depths should approximate the position assumed by nonpolar side chains on this peptide (Qin and Cafiso, 1996). If the most likely configuration for the nitroxide side chain R1 is assumed (Altenbach et al., 2001; Langen et al., 2000), these positions indicate that the backbone of the SCAMP-E peptide lies at or below the level of the lipid phosphates.

TABLE 2.

Membrane depths for spin labels on SCAMP-E peptide

| PC/PS (3:1)

|

PC/PS/PI(4,5)P2 (73:22:5)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peptide | Φ | d (Å) | Φ | d (Å) |

| C1R1 | 0.64 | 7.3 | 0.82 | 7.8 |

| I6R1 | 0.76 | 7.6 | 1.3 | 9.1 |

| A9R1 | 1.2 | 8.8 | 1.2 | 8.8 |

The membrane depth, d, corresponds to the position of the nitroxide side chain from the level of the lipid phosphate where positive values indicate a position within the bilayer. The error in the depth due to the error in Φ is ∼±1 Å.

Interfacial location of SCAMP-E determined by high-resolution NMR in bicelles

Shown in Fig. 5 are NMR spectra of the SCAMP-E peptide in aqueous solution and bound to DCPC/DMPG/DMPC (67:20:13) bicelles. As expected, many 1H resonances are resolved for SCAMP-E bound to bicelles, but they are significantly broader than resonances acquired from the peptide in aqueous solution. Proton chemical shift assignments for the SCAMP-E peptide were determined using standard techniques from 1H TOCSY and ROESY spectra of SCAMP-E in solution, and 1H TOCSY and NOESY spectra of SCAMP-E in bicelles (Wuthrich, 1986). The chemical shift positions in solution and bicelle-bound peptide are similar (see Fig. 5) and the assignment of the SCAMP-E 1H chemical shifts in solution facilitated the assignment of the bicelle-bound SCAMP-E 1H chemical shifts (See Supplementary Material for chemical shift assignments).

FIGURE 5.

1H NMR spectra (500 MHz) showing the aromatic and guanidino 1H resonances of SCAMP-E in (A) solution and (B) DCPC/DMPG/DMPC (67:20:13) bicelles. The resonances are broader in bicelles but have similar chemical shifts. (See Supplementary Material for chemical shift assignments).

Proton spin-lattice relaxation rates were measured for the peptide-bicelle system in the presence and absence of oxygen. Shown in Fig. 6 are the paramagnetic enhancements of proton spin-lattice relaxation rates due to oxygen, R1para, for lipid and peptide protons (see Supplementary Material for a list of these rates). As seen in Fig. 6, the value of R1para for the bilayer lipid protons increases as one proceeds from the choline methyls of the headgroup to the methyls of the fatty acid chains. This behavior has been observed previously (Ellena et al., 2002, 2003; Prosser et al., 2000, 2001) and is a result of the increased solubility of oxygen in the membrane hydrocarbon phase (Windrem and Plachy, 1980).

FIGURE 6.

Oxygen-induced spin-lattice relaxation rates (R1para) in units of s−1 for several bilayer lipid (▪) and SCAMP-E peptide (•) 1H resonances. The lipid bilayer resonances are arranged in order of increasing distance (left to right) from the membrane surface.

The position of the SCAMP-E peptide at the lipid interface was determined by varying the peptide orientation and depth to obtain a best fit of the measured values of R1para for the peptide with the depth dependence of R1para (see Methods). Shown in Fig. 7 are the depths for peptide protons obtained, the lipid depth data, which were used as calibration points, and a line defining the best fit of Eq. 8 to the R1para data. In this fit, all SCAMP-E intrabilayer depths differ from the best-fit line by <1.5 Å. A few flexible side-chain dihedral angles were manually adjusted to obtain this fit, along with small changes to two backbone dihedral angles (R4 φ and ϕ were changed from −65 to −85 and from −40 to −20, respectively).

FIGURE 7.

Relationship between bilayer depth and O2-induced spin-lattice relaxation rate (1/T1para). Paramagnetic enhancements for bilayer lipid protons (•) and SCAMP-E (○) bound to bicelles (Fig. 6). The solid line is the best fit of the data to a hyperbolic tangent function: 1/T1para = A tanh[B(x − C)] + D, where x is the distance between the relaxing nucleus and the lipid phosphorus atom plane, and the fitted parameters are A = 3.1, B = 0.16, C = 3.2, D = 3.5. The fit also generates an orientation for the SCAMP-E peptide at the membrane interface (see Fig. 8).

Shown in Fig. 8 is the location of SCAMP-E at the lipid interface that was obtained from the fit to the 1H relaxation data shown in Fig. 7. The SCAMP-E helical axis (backbone shown in yellow) is nearly coincident with the carbonyl carbon plane, which is in the bilayer interface region (Hristova and White, 1998). The peptide is amphipathic and most of the aromatic side chains (shown in green) are located in the lipid hydrocarbon. Thus, the picture obtained from the NMR data in bicelles is consistent with the location of the R1 side chain obtained by EPR depth measurements. In addition, this model places the charged side chains (shown in red) at or deeper than the level of the lipid phosphates. In particular, the R4 and R11 1Hη (guanidino hydrogens) reside 2 Å deeper than the carbonyl carbons of the lipid.

FIGURE 8.

Location of SCAMP-E when bound to a bilayer. The data in Fig. 6 were used to position SCAMP-E in a PC bilayer leaflet (bilayer coordinates from Scott E. Feller, http://persweb.wabash.edu/facstaff/fellers) (Armen et al., 1998). The best-fit planes of the bilayer phosphorus and carbonyl atoms are shown and are perpendicular to the page. The SCAMP-E peptide backbone is shown in yellow, positively charged side chains are red, and nonpolar side chains are green. The two arginine and one lysine residue are labeled. Although the placement of the aromatic and arginine side chains relative to the membrane interface is defined by values of R1para, there is considerable uncertainty regarding the conformation of the peptide. It was not possible to determine the structure from 1H NMR data of the bicelle-bound peptide, and this peptide may in fact exist in a mixture of conformational forms.

Two additional sets of NMR data are consistent with the position shown in Fig. 8. First, three broad peaks appear in the backbone HN region of the 1H spectrum of SCAMP-E in bicelles. Because of spectral overlap, more than one backbone HN contributes to each of these peaks, and we did not use these data to generate the structure shown in Fig. 8. However, these three peaks have similar values of R1para, which average to 3.4 ± 0.4 s−1. Comparing this rate to those for the lipids (Fig. 6) indicates that that these backbone HN protons assume a position near the glycerol backbone. Second, two-dimensional 1H-1H NOESY spectra indicate that there are crosspeaks between side-chain resonances of SCAMP-E (aromatic and R-guanidino) and acyl resonances of the bicelle lipids at relatively short (75-ms) mixing times (see Supplementary Material). Because these NOE data are much less quantitative than the R1para with respect to peptide position, they were not used to produce the model in Fig. 8.

DISCUSSION

The results described here provide evidence that a basic aromatic peptide derived from SCAMP2 has the capacity to sequester PI(4,5)P2 within the bilayer. Three observations suggest that the SCAMP-E peptide interacts with PI(4,5)P2. First, the results of binding measurements (Fig. 1) indicate that this peptide has an enhanced affinity toward membranes composed of PI(4,5)P2. Second, membrane binding of the peptide slows the rotational correlation time of a spin-labeled analog of PI(4,5)P2, proxyl-PI(4,5)P2. Finally, this peptide inhibits the enzymatic activity of both PLC-δ1 and PLC-β on lipid monolayers by over 90% when present in the subphase at concentrations of 1 μM.

When compared to the MARCKS-ED, the SCAMP-E peptide binds much more weakly to PI(4,5)P2 containing membranes. The SCAMP-E peptide binding constant to PC membranes increases 100-fold when 3 mol % PI(4,5)P2 is present. For the MARCKS-ED, a 10,000-fold increase in binding constant in the presence of 1 mol % PI(4,5)P2 is observed (Wang et al., 2001). Nonetheless, the SCAMP-E affinity is significant and ∼50% of the peptide will be membrane-bound in the presence of 10−6 M PI(4,5)P2 in PC membranes. This is similar to the binding constant measured for the interaction of neomycin (10−5 M) (Gabev et al., 1989) or the PH domain of PLC-δ1 (10−6 M) with PI(4,5)P2 (Garcia et al., 1995). It should be noted that these affinities are not entirely comparable, because the SCAMP-E peptide binds to pure PC membranes whereas neomycin and the PH domain do not.

A second determination of the strength of the interaction between PI(4,5)P2 and the SCAMP-E peptide was made by measuring the amplitude of the EPR spectrum of proxyl-PI(4,5)P2 as a function of peptide concentration. This titration (Fig. 2 B) was carried out under high lipid concentrations so that all the added peptide was membrane-bound. Under these conditions, the interaction between SCAMP-E and proxyl-PI(4,5)P2 was found to have a binding constant of 104 M−1 (see Eq. 4). This binding constant is 100 times weaker than the binding measured by membrane partitioning, a difference that reflects the different conditions used in the two types of binding experiments. The EPR measurement using proxyl-PI(4,5)P2 provides a measure of the free energy of interaction between peptide and lipid once the peptide is membrane-bound, whereas the binding data in Fig. 1 provide a measure of free energy of transfer from the aqueous solution to the membrane interface.

A third measure of the interaction between SCAMP-E and PI(4,5)P2 was obtained by examining the enzymatic activity of PLC on monolayer surfaces. The data presented here indicate that SCAMP-E is quite potent at inhibiting the enzymatic hydrolysis of PI(4,5)P2 by PLC, a finding that is consistent with the EPR result indicating that SCAMP-E binds PI(4,5)P2 within the plane of the bilayer. The MARCKS-ED is more inhibitory than the SCAMP-E peptide, producing a 90% inhibition of PLC activity at a concentration of 100 nM (a 10-fold lower peptide concentration than that required for SCAMP-E). However, heptalysine (Lys7) produces little inhibition even when present at a 100-times higher concentration than that required for inhibition by SCAMP-E (Wang et al., 2002). Although some of the differences in the inhibition produced by these peptides may be due to differences in their membrane binding, SCAMP-E appears to be particularly effective at inhibiting PLC when peptides of roughly similar binding energies are compared (Wang et al., 2002).

It should be noted that the simplest interpretation of these enzymatic measurements is that SCAMP-E inhibits PLC activity by binding and sequestering its substrate, PI(4,5)P2. However, other interactions may play a role and cannot be ruled out. Because the SCAMP-E peptide is deeply buried within the interface when membrane-bound, it might alter the lateral pressure profile within membranes. PLC is known to be modulated by lateral pressure (Boguslavsky et al., 1994; Rebecchi et al., 1992) and it is conceivable that some of the effect of the SCAMP-E peptide observed here on PLC may be mediated by changes in lateral pressure.

A number of observations indicate that the interaction between SCAMP-E and PI(4,5)P2 is driven by nonspecific electrostatic interactions. There is good evidence that the MARCKS-ED interacts with PI(4,5)P2 through a nonspecific electrostatic mechanism. The MARCKS-ED has a valence of +13 and PI(4,5)P2 has an average valence of −3 to −4. Multiple PI(4,5)P2 (probably 3–4) are bound by the MARCKS-ED and this stoichiometry is consistent with that expected for an electrostatic interaction (Gambhir et al., 2004; Rauch et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2002, 2004). In the case of the SCAMP-E peptide the binding data are well fit by Eqs. 4–7, which assume a 1:1 stoichiometry. A 1:1 stoichiometry would be expected if the interactions between the SCAMP-E peptide and PI(4,5)P2 are also driven by nonspecific electrostatic interactions, since there are approximately equal charges on SCAMP-E and PI(4,5)P2.

Site-directed spin labeling also suggests that nonspecific interactions drive the interaction between the SCAMP-E peptide and PI(4,5)P2. As shown in Fig. 4, the EPR lineshapes of spin-labeled SCAMP-E are remarkably similar, irrespective of the lipid to which the peptide is bound. In addition to lineshapes, the depths of the R1 labels when bound to membranes are unchanged by the presence of PI(4,5)P2 (Table 2). The EPR spectrum of the spin-labeled side chain R1 is highly sensitive to changes in tertiary contact or backbone dynamics (Columbus et al., 2001; Hubbell et al., 1998), and the absence of a change in lineshape or membrane depth indicates that SCAMP-E has a similar configuration and is interacting similarly with membranes in either the absence or presence of PI(4,5)P2. A similar observation was made using SDSL for spin-labeled peptides derived from the MARCKS-ED (Rauch et al., 2002).

Two variants of the SCAMP-E peptide having an identical amino acid composition to that of native SCAMP-E, but with altered sequences, appear to sequester proxyl-PI(4,5)P2 with approximately the same affinity as the native peptide. This observation suggests that amino acid composition rather than sequence is important for the interaction of SCAMP-E with PI(4,5)P2. Taken together, these observations indicate that the interaction between the SCAMP-E peptide and PI(4,5)P2 does not involve specific molecular contacts or hydrogen bonding, and that the interaction is most easily explained by a mechanism that is electrostatic in origin.

If electrostatic interactions between peptides like SCAMP-E and PI(4,5)P2 are relevant on the cytoplasmic surface of the plasma membrane, they must occur in the presence of significant levels of negatively charged lipid. As indicated above, the presence of 30 mol % phosphatidylserine within a PC bilayer does not inhibit the interaction between SCAMP-E and the spin-labeled proxyl-PI(4,5)P2. This is consistent with the finding that the MARCKS-ED sequesters PI(4,5)P2 in the presence of 15–35 mol % PS (Gambhir et al., 2004), and with a computational study on the electrostatic interactions between basic peptides and PI(4,5)P2. In the presence of 15–35 mol % negatively charged lipid, significant positive potentials are predicted close to the MARCKS-ED when it is localized on the membrane interface (Wang et al., 2004). Negatively charged monovalent lipid produces a negative electrostatic surface potential at regions far from the peptide. PI(4,5)P2 will preferentially interact with the peptide because the Boltzmann relation predicts a much stronger interaction with the peptide for a lipid with a valence of −4 (PI(4,5)P2) than a lipid with a valence of −1 (PS). Highly charged peptides, such as those from MARCKS, are predicted to have many energetically equivalent favorable sites for association with PI(4,5)P2 (Wang et al., 2004). The SCAMP-E peptide likely produces such a local electrostatic free energy minimum for PI(4,5)P2.

The position of the SCAMP-E peptide at the membrane surface is similar to that assumed by the MARCKS-ED peptide (Ellena et al., 2003; Qin and Cafiso, 1996; Zhang et al., 2003). The EPR data obtained here place the R1 side chains (positions 1, 6, and 9) on the spin-labeled SCAMP-E peptides several Å below the level of the membrane phosphorus atoms. Likewise the NMR data show that the Phe and Tyr side chains of the SCAMP-E peptide lie in the hydrocarbon region of the bicelles, with the peptide backbone at or very close to the level of the carbonyl carbons. The orientation and depth obtained for SCAMP-E also provides information on the positions of the arginine residues on the peptide. Obtaining direct information on the position of the charged residues in the MARCKS-ED has been more problematic due to its highly redundant sequence. For SCAMP-E, the data acquired for R4 and R11 guanidino hydrogens indicate that the positive charges of these arginine side chains lie ∼2 Å deeper than the carbonyl carbons.

The interfacial position of the arginine side chains may seem surprising because it should entail a significant Born energy penalty. However, this electrostatic penalty is difficult to estimate because the effective dielectric constant in the interfacial region is not precisely known, and because the interface is highly anisotropic. The charge on arginine is partially delocalized, which will increase its ionic radius and lower its Born energy. If a radius of 2Å and a dielectric constant of 20 are assumed, the Born energy penalty would be 6 kcal/mole to transfer two arginines into the interface. However, this may be an overestimate since the transfer free energy for moving two entire arginine residues from water to octanol (dielectric constant 10) is estimated to be +3.6 kcal/mole (White and Wimley, 1998). Two types of favorable interactions may act to balance out this energy penalty. First, water-interfacial hydrophobicity scales predict that the four aromatic side chains on the peptide will contribute a total of ∼−5 kcal/mole to the partition free energy of the peptide (White and Wimley, 1998). Second, the charged side chains interact favorably with the negatively charged interface and this interaction will lower the binding free energy. For a lysine residue positioned at an interface containing negatively charged lipid, the Coulombic interaction will lower the energy of the bound peptide by 1.4 kcal/mole (Kim et al., 1991). As a result, the position of the arginine residues in SCAMP-E shown in Fig. 8 is not inconsistent with the total binding energy expected for this peptide.

The electrostatic field on the membrane interface that results from these charged side chains will also be enhanced as a consequence of placing these charges within a low dielectric region of the interface (McLaughlin, 1977). A recent computational study indicates that PI(4,5)P2 sequestration is enhanced as charged peptides are moved from the aqueous phase closer to the membrane interface (Wang et al., 2004). In this case, the position of the SCAMP-E peptide within the interface might be particularly important for an electrostatic sequestration mechanism, and may explain the potent ability of SCAMP-E to bind PI(4,5)P2.

The aromatic residues of the SCAMP-E peptide are likely to drive this peptide into the membrane interface. In contrast to the position found for SCAMP-E and the MARCKS-ED, positively charged peptides lacking hydrophobic residues, such as pentalysine, hexalysine, or the N-terminal fragment of src (myr-src(2–16)), reside several Å on the aqueous side of the lipid interface within the aqueous double layer (Victor and Cafiso, 1998, 2001). Indeed, replacing the five phenylalanine residues in the MARCKS-ED peptide with alanines shifts the equilibrium binding position of the peptide more than 10 Å so that it resides in the aqueous phase (Victor et al., 1999). These highly charged hydrophilic peptides are believed to bind to membranes due to a long-range Coulombic attraction, but fail to penetrate the bilayer interface due to a desolvation repulsion that is experienced near the membrane interface (Ben-Tal et al., 1996; Murray et al., 1998). The addition of hydrophobic residues to the sequence is thought to facilitate membrane penetration by allowing the peptide to overcome the desolvation repulsion.

At this time, neither the role of the native SCAMP protein nor the function of the highly conserved E segment is understood. Evidence has been obtained implicating SCAMPs in the membrane fusion that takes place during exocytosis (Fernandez-Chacon et al., 1999; Guo et al., 2002; Liu et al., 2002). Ablation of SCAMP1 impairs opening of the fusion pore and the E segment of SCAMP2 inhibits exocytosis when employed as a soluble peptide in permeabilized cells and when mutated within the full-length protein and expressed in intact cells. As part of a short amphipathic cytoplasmic linker connecting the second and third transmembrane helices, the E segment is likely to bind within the bilayer interface in the intact protein (Hubbard et al., 2000). SCAMPs are present in high copy number within the cell and also have a propensity to aggregate (Wu and Castle, 1997; A. Castle, unpublished). As a consequence, multiple copies of the E segment may be clustered and positioned at the membrane interface. Collectively, these segments might act directly on the membrane interface to alter the lateral distribution of polyphosphoinositides or modulate the interfacial properties of the bilayer.

In summary, a positively charged but highly aromatic peptide derived from a secretory carrier membrane protein binds to PI(4,5)P2 containing membranes and interacts with PI(4,5)P2 within the plane of the membrane. When bound to lipid bilayers or bicelles, EPR and NMR methods indicate that this peptide is positioned within the interface, so that the peptide backbone is near the level of the lipid carbonyl carbons. The charged residues on this peptide are placed at or below a plane defined by the lipid phosphates. The deep interfacial position of these charged residues is likely to facilitate interactions with PI(4,5)P2 through a nonspecific electrostatic mechanism.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

An online supplement to this article can be found by visiting BJ Online at http://www.biophysj.org.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Stuart McLaughlin and Jiyao Wang for performing binding and PLC monolayer activity measurements, and Colin Ferguson and Glenn Prestwich for providing the proxyl-PI(4,5)P2. We also thank Stuart McLaughlin for many useful discussions regarding the role of electrostatics in PI(4,5)P2 sequestration, and Gail Fanucci for productive comments on this manuscript.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants GM62305 (to D.S.C.) and DE09655 (to J.D.C.).

Sajith Jaysinghne's present address is Neurogenetics Institute, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90033.

References

- Altenbach, C., D. A. Greenhalgh, H. G. Khorana, and W. L. Hubbell. 1994. A collision gradient-method to determine the immersion depth of nitroxides in lipid bilayers. Application to spin-labeled mutants of bacteriorhodopsin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 91:1667–1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altenbach, C., K. J. Oh, R. J. Trabanino, K. Hideg, and W. L. Hubbell. 2001. Estimation of inter-residue distances in spin labeled proteins at physiological temperatures: experimental strategies and practical limitations. Biochemistry. 40:15471–15482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuzova, A., L. Wang, J. Wang, G. Hangyas-Mihalyne, D. Murray, B. Honig, and S. McLaughlin. 2000. Membrane binding of peptides containing both basic and aromatic residues. Experimental studies with peptides corresponding to the scaffolding region of caveolin and the effector region of MARCKS. Biochemistry. 39:10330–10339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armen, R. S., O. D. Uitto, and S. E. Feller. 1998. Phospholipid component volumes: determination and application to bilayer structure calculations. Biophys. J. 75:734–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Tal, N., B. Honig, R. M. Peitzsch, G. Denisov, and S. McLaughlin. 1996. Binding of small basic peptides to membranes containing acidic lipids: theoretical models and experimental results. Biophys. J. 71:561–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boguslavsky, V., M. Rebecchi, A. J. Morris, D. Y. Jhon, S. G. Rhee, and S. McLaughlin. 1994. Effect of monolayer surface pressure on the activities of phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C-beta 1, -gamma 1, and -delta 1. Biochemistry. 33:3032–3037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buser, C. A., and S. McLaughlin. 1998. Ultracentrifugation technique for measuring the binding of peptides and proteins to sucrose-loaded phospholipid vesicles. Methods Mol. Biol. 84:267–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caroni, P. 2001. New EMBO members' review: actin cytoskeleton regulation through modulation of PI(4,5)P(2) rafts. EMBO J. 20:4332–4336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Columbus, L., T. Kalai, J. Jeko, K. Hideg, and W. L. Hubbell. 2001. Molecular motion of spin labeled side chains in a-helices: analysis by variation of side chain structure. Biochemistry. 40:3828–3846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cremona, O., and P. De Camilli. 2001. Phosphoinositides in membrane traffic at the synapse. J. Cell Sci. 114:1041–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czech, M. P. 2000. PIP2 and PIP3: complex roles at the cell surface. Cell. 100:603–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiNitto, J. P., T. C. Cronin, and D. G. Lambright. 2003. Membrane recognition and targeting by lipid-binding domains. Sci. STKE. 2003:re16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellena, J. F., M. C. Burnitz, and D. S. Cafiso. 2003. Location of the myristoylated alanine-rich C-kinase substrate (MARCKS) effector domain in negatively charged phospholipid bicelles. Biophys. J. 85:2442–2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellena, J. F., V. V. Obraztsov, V. L. Cumbea, C. M. Woods, and D. S. Cafiso. 2002. Perfluorooctyl bromide has limited membrane solubility and is located at the bilayer center. Locating small molecules in lipid bilayers through paramagnetic enhancements of NMR relaxation. J. Med. Chem. 45:5534–5542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Chacon, R., G. Alvarez de Toledo, R. E. Hammer, and T. C. Sudhof. 1999. Analysis of SCAMP1 function in secretory vesicle exocytosis by means of gene targeting in mice. J. Biol. Chem. 274:32551–32554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier, A. A., M. A. Wisner, N. J. Malmberg, K. G. Victor, G. E. Fanucci, E. A. Nalefski, J. J. Falke, and D. S. Cafiso. 2002. Membrane orientation and position of the C2 domain from cPLA2 by site-directed spin labeling. Biochemistry. 41:6282–6292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabev, E., J. Kasianowicz, S. Abbott, and S. McLaughlin. 1989. Binding of neomycin to phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2). Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 979:105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gambhir, A., G. Hangyas-Mihalyne, I. Zaitseva, D. S. Cafiso, J. Wang, D. Murray, S. N. Pentyala, S. O. Smith, and S. McLaughlin. 2004. Electrostatic sequestration of PIP2 on phospholipid membranes by basic/aromatic regions of proteins. Biophys. J. 86:2188–2207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, P., R. Gupta, S. Shah, A. J. Morris, S. A. Rudge, S. Scarlata, V. Petrova, S. McLaughlin, and M. J. Rebecchi. 1995. The pleckstrin homology domain of phospholipase C-delta 1 binds with high affinity to phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate in bilayer membranes. Biochemistry. 34:16228–16234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Z., L. Liu, D. Cafiso, and D. Castle. 2002. Perturbation of a very late step of regulated exocytosis by a secretory carrier membrane protein (SCAMP2)-derived peptide. J. Biol. Chem. 277:35357–35363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hristova, K., and S. H. White. 1998. Determination of the hydrocarbon core structure of fluid dioleoylphosphatidylcholine (DOPC) bilayers by x-ray diffraction using specific bromination of the double bonds: effect of hydration. Biophys. J. 74:2419–2433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard, C., D. Singleton, M. Rauch, S. Jayasinghe, D. Cafiso, and D. Castle. 2000. The secretory carrier membrane protein family: structure and membrane topology. Mol. Biol. Cell. 11:2933–2947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbell, W. L., A. Gross, R. Langen, and M. A. Lietzow. 1998. Recent advances in site-directed spin labeling of proteins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 8:649–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley, J. H., and T. Meyer. 2001. Subcellular targeting by membrane lipids. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 13:146–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J., M. Mosior, L. A. Chung, H. Wu, and S. McLaughlin. 1991. Binding of peptides with basic residues to membranes containing acidic phospholipids. Biophys. J. 60:135–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupce, E., J. Boyd, and I. D. Campbell. 1995. Short selective pulses for biochemical applications. J. Magn. Reson. Ser. B. 106:300–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langen, R., K. J. Oh, D. Cascio, and W. L. Hubbell. 2000. Crystal structures of spin-labeled T4 lysozyme mutants: implications for the interpretation of EPR spectra in terms of structure. Biochemistry. 39:8396–8405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L., Z. Guo, Q. Tieu, A. Castle, and D. Castle. 2002. Role of secretory carrier membrane protein SCAMP2 in granule exocytosis. Mol. Biol. Cell. 13:4266–4278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luchette, P. A., R. S. Prosser, and C. R. Sanders. 2001. Oxygen as a paramagnetic probe of membrane protein structure by cysteine mutagenesis and 19F NMR spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124:1778–1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, T. F. 2001. PI(4,5)P2 regulation of surface membrane traffic. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 13:493–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin, S., J. Wang, A. Gambhir, and D. Murray. 2002. PIP(2) and proteins: interactions, organization, and information flow. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 31:151–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin, S. A. 1977. Electrostatic potentials at membrane-solution interfaces. Curr. Top. Membr. Transp. 9:71–144. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, D., L. Hermida-Matsumoto, C. A. Buser, J. Tsang, C. T. Sigal, N. Ben-Tal, B. Honig, M. D. Resh, and S. McLaughlin. 1998. Electrostatics and the membrane association of Src: theory and experiment. Biochemistry. 37:2145–2159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Z., and D. S. Cafiso. 1996. Membrane structure of the PKC and calmodulin binding domain of MARCKS determined by site-directed spin-labeling. Biochemistry. 35:2917–2925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overduin, M., M. L. Cheever, and T. G. Kutateladze. 2001. Signaling with phosphoinositides: better than binary. Mol. Interv. 1:150–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, R. H., and I. Pascher. 1979. The molecular structure of lecithin dihydrate. Nature. 281:499–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prestwich, G. D. 2004. Phosphoinositide signaling: from affinity probes to phamaceutical targets. Chem. Biol. 11:619–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prosser, R. S., P. A. Luchette, and P. W. Westerman. 2000. Using O2 to probe membrane immersion depth by 19F NMR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 97:9967–9971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prosser, R. S., P. A. Luchette, P. W. Westerman, A. Rozek, and R. E. W. Hancock. 2001. Determination of membrane immersion depth with O2: A high-pressure 19F NMR study. Biophys. J. 80:1406–1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauch, M. E., C. G. Ferguson, G. D. Prestwich, and D. S. Cafiso. 2002. Myristoylated alanine-rich C kinase substrate (MARCKS) sequesters spin-labeled phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate in lipid bilayers. J. Biol. Chem. 277:14068–14076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raucher, D., T. Stauffer, W. Chen, K. Shen, S. Guo, J. D. York, M. P. Sheetz, and T. Meyer. 2000. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate functions as a second mesenger that regulates cytoskeleton-plasma membrane adhesion. Cell. 100:221–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebecchi, M., V. Boguslavsky, L. Boguslavsky, and S. McLaughlin. 1992. Phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C-delta 1: effect of monolayer surface pressure and electrostatic surface potentials on activity. Biochemistry. 31:12748–12753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Runnels, L. W., L. Yue, and D. E. Clapham. 2002. The TRPM7 channel is inactivated by PIP(2) hydrolysis. Nat. Cell Biol. 4:329–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmon, A., S. W. Dodd, G. W. Williams, J. M. Beach, and M. F. Brown. 1987. Configurational statistics of acyl chains in polyunsaturated lipid bilayers from 2H NMR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 109:2600–2609. [Google Scholar]

- Sechi, A. S., and J. Wehland. 2000. The actin cytoskeleton and plasma membrane connection: PtdIns(4,5)P(2) influences cytoskeletal protein activity at the plasma membrane. J. Cell Sci. 113:3685–3695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seigneuret, M., and D. Levy. 1995. A high resolution 1H NMR approach for structure determination of membrane peptides and proteins in non-deuterated detergent: Application to mastoparan X solubilized in n-octylglucoside. J. Biomol. NMR. 5:345–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheetz, M. P. 2001. Cell control by membrane-cytoskeleton adhesion. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2:392–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonsen, A., A. E. Wurmser, S. D. Emr, and H. Stenmark. 2001. The role of phosphoinositides in membrane transport. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 13:485–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng, C. L., H. Hong, S. Kiihne, and R. G. Bryant. 2001. Molecular oxygen spin-lattice relaxation in solutions measured by proton magnetic relaxation dispersion. J. Magn. Reson. 148:31–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toker, A. 1998. The synthesis and cellular roles of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 10:254–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victor, K., and D. S. Cafiso. 1998. Structure and position of the N-terminal binding domain of pp60src at the membrane interface. Biochemistry. 37:3402–3410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victor, K., J. Jacob, and D. S. Cafiso. 1999. Interactions controlling the membrane binding of basic protein domains: phenylalanine and the attachment of the myristoylated alanine-rich C-kinase substrate protein to interfaces. Biochemistry. 38:12527–12536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victor, K. G., and D. S. Cafiso. 2001. Location and dynamics of basic peptdies at the membrane interface: EPR spectroscopy of TOAC labeled peptides. Biophys. J. 81:2241–2250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vold, R. R., and R. S. Prosser. 1996. Magnetically oriented phospholipid bilayered micelles for structural studies of polypeptides. Does the ideal bicelle exist? J. Magn. Reson. B113:267–271. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J., A. Arbuzova, G. Hangyas-Mihalyne, and S. A. McLaughlin. 2001. The effector domain of myristoylated alanine-rich C kinase substrate binds strongly to phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. J. Biol. Chem. 276:5012–5019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J., A. Gambhir, G. Hangyas-Mihalyne, D. Murray, U. Golebiewska, and S. McLaughlin. 2002. Lateral sequestration of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate by the basic effector domain of myristolated alanine-rich C kinase substrate is due to nonspecific electrostatic interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 277:34401–34412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J., A. Gambhir, S. McLaughlin, and D. Murray. 2004. A computational model for the electrostatic sequestration of PI(4,5)P2 by membrane-adsorbed basic peptides. Biophys. J. 86:1969–1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White, S. H., and W. C. Wimley. 1998. Hydrophobic interactions of peptides with membrane interfaces. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1376:339–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windrem, D. A., and W. Z. Plachy. 1980. The diffusion-solubility of oxygen in lipid bilayers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 600:655–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L., C. S. Bauer, X. G. Zhen, C. Xie, and J. Yang. 2002. Dual regulation of voltage-gated calcium channels by PtdIns(4,5)P2. Nature. 419:947–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, T. T., and J. D. Castle. 1997. Evidence for colocalization and interaction between 37 and 39 kDa isoforms of secretory carrier membrane proteins (SCAMPs). J. Cell Sci. 110:1533–1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuthrich, K. 1986. NMR of Proteins and Nucleic Acids. Wiley and Sons, New York.

- Zhang, W., E. Crocker, S. McLaughlin, and S. O. Smith. 2003. Binding of peptides with basic and aromatic residues to bilayer membranes: Phenylalanine in the MARCKS effector domain penetrates into the hydrophobic core of the bilayer. J. Biol. Chem. 278:21459–21466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.