Abstract

The Rad17-Mec3-Ddc1 complex is essential for the cellular response to genotoxic agents and is thought to be important for sensing DNA lesions. Deletion of any of the RAD17, MEC3 or DDC1 genes abolishes the G1 and G2 and impairs the intra-S DNA-damage checkpoints. We characterize a dominant-negative mec3-dn mutation that has an unexpected phenotype. It inactivates the G1 checkpoint while it leaves the G2 response functional, thus revealing a difference in the requirements of the DNA-damage response in different phases of the cell cycle. In an attempt to identify the molecular defect imparted by the mutation, we dissected step-by-step the signaling cascade, which is triggered by DNA lesions and requires the activity of Mec1 and Rad53 kinases. The analysis of the phosphorylation state of checkpoint factors and critical protein interactions showed that, in mec3-dn cells, the signal transduction cascade is triggered normally, and the central kinase Mec1 can be activated. In G1 cells expressing the mutation, the signaling cannot proceed any further along the pathway, indicating that the Rad17 complex acts after the activation of Mec1, possibly recruiting targets for the kinase. We also show that the function of the G2 checkpoint in mutant cells is maintained by an uncharacterized activity of Tel1, the yeast homologue of ATM. This work thus reports a previously undiscovered role for Tel1 in checkpoint control.

Eukaryotic cells evolved checkpoint mechanisms that control the order of events during cell cycle progression (1) and are extremely important for the preservation of genome integrity, which requires fidelity of DNA replication and chromosome segregation. The DNA-damage checkpoint, elicited upon detection of alterations in chromosome structure, leads to temporary arrest of the G1/S and G2/M transitions and slows down DNA replication, depending on when the lesion is sensed in the cell cycle (2–5). In the last few years, a big effort has been devoted to understanding the organization of the DNA-damage response pathway. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, several data suggested the existence of so-called sensor proteins, represented by Rad17, Mec3, Ddc1, Rad24, and Rad9, which would elicit a signal that is relayed, mostly via the Mec1 and Rad53 protein kinases, to a set of largely unknown effectors (2, 5, 6). These genes are absolutely required for the G1 and G2 DNA-damage checkpoints, whereas in the intra-S response, Rad17, Mec3, Ddc1, and Rad9 have only a partial role (7–10). Rad17, Mec3, and Ddc1 physically interact, forming a heterotrimeric complex structurally related to proliferating cell nuclear antigen, whereas Rad24 is homologous to the replication factor C subunits and can be purified associated with Rfc2–5 (7, 11–13). These observations would place the above-mentioned proteins directly at the damage, and genetic data support this idea (14, 15). Mec1 and Rad53 play fundamental roles in the DNA-damage checkpoint pathway. Mec1 belongs to the PI-3 protein kinase family, which also includes ATM and DNA-PK, and is the homologue of ATR (16). The function of Tel1, the structural homologue of human ATM, partially overlaps with that of Mec1 but is still poorly defined (17–19). Rad53, a dual specificity protein kinase, is transactivated after DNA damage and is subjected to autophosphorylation events; this activation depends upon MEC1, DDC2/LCD1, RAD17, MEC3, DDC1, RAD24, and RAD9 (9, 10, 19–23). The order of function of the proteins in the signal transduction cascade has been inferred from genetic and phosphorylation studies, but some data seem to conflict. In fact, the so-called sensor proteins are required for Mec1-dependent phosphorylation of Rad53 (2, 5, 6). On the other hand, some of these factors, such as Rad9 and Ddc1, are themselves phosphorylated by Mec1 in a Rad17 complex-dependent manner, suggesting a feedback loop (22, 24–27). Finally, both Mec1 and its S. pombe homologue, Rad3, interact with and phosphorylate Ddc2/Lcd1 and Rad26, respectively; this phosphorylation event is independent of all other checkpoint proteins, suggesting that Mec1 can be activated without the need for the Rad17 complex function (21–23, 28, 29).

In this article, we describe a mutant version of MEC3 that, behaving like the deletion of the gene, inactivates the DNA-damage checkpoint in G1 and partially compromises the intra-S checkpoint. Surprisingly, the mutant doesn't alter the G2/M arrest, which, instead, is totally defective in the deletion strain (30). Such a mutant thus reveals a difference in the requirements for checkpoint activation in various phases of the cell cycle. We show that the mutant is proficient in phosphorylating Ddc1, an early event in the signaling cascade; in G1, the defective step is the phosphorylation of Rad9 and its interaction with Rad53. Finally, we uncover a previously unreported function for Tel1 which, in this genetic background, is required for Rad53 activation in G2 cells.

Materials and Methods

Plasmids and Strains.

Plasmid pM3.10 carries the complete MEC3 ORF, which is tagged with a 9MYC epitope at the N terminus and cloned into the two-hybrid vector pEG202 (31). Plasmids pNB187-MEC3 and pNB187-mec3-dn contain, respectively, wild-type MEC3 or 9MYC-MEC3 (mec3-dn) under the control of the GAL1 promoter (32). All yeast strains derive from W303 and are described in Table 1, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org. Standard yeast genetic techniques and media have been described (7).

Cell Cycle Arrests and Genotoxic Agent Treatments.

Cells grown to log phase were blocked in G1 with 20 μg/ml α-factor and in G2 with 20 μg/ml nocodazole. Arrests were verified by estimating the percentage of budded/unbudded cells. 4-Nitroquinoline oxide (1 μg/ml; 4NQO) was added for 15 min to the cultures when needed. Cell cycle synchronization and checkpoint function analysis were performed as described (24, 30). Sensitivity to DNA damaging agents was evaluated according to published procedures (33).

Protein Extracts and Immunoprecipitation Analysis.

Native extracts were obtained as described (24). For phosphorylation analysis, cell extracts were prepared by trichloro acetic acid (TCA) treatment (10) and analyzed by standard electrophoretic and immunoblotting methods. All blots were stained with Sypro Ruby (Molecular Probes) and analyzed in a Typhoon (Amersham Pharmacia) to verify similar loading in all wells. For Rad9 analysis, extracts were run on 3–8% Tris-acetate gels (NOVEX, San Diego) following manufacturer suggestions. Native extracts were immunoprecipitated following published procedures (24). GST-FHA2 was purified from bacteria transformed with the expression plasmid, and pull-down experiments were performed as described (27).

Results

Identification of a mec3 Mutant Defective Only in a Subset of the DNA-Damage Checkpoints.

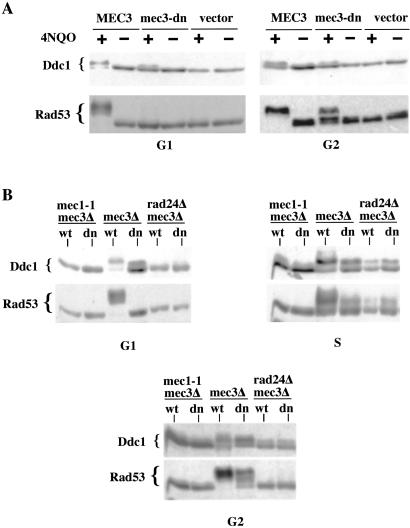

With the aim of identifying new proteins involved in DNA-damage response in yeast, we generated two-hybrid bait plasmids for Rad17, Mec3, Ddc1, and Rad24, where the complete coding sequence is cloned in-frame with the DNA-binding domain of LexA, and its expression is controlled by the constitutive promoter ADH1 (31). We analyzed the effect of these hybrid proteins on the DNA-damage checkpoint. Although plasmids containing Rad17, Ddc1, and Rad24 fusions did not influence checkpoint activation, a plasmid (pM3.10) expressing a fusion consisting of lexA-9MYC-MEC3 conferred a particular checkpoint defect. We treated G1-arrested cells with UV (not shown) or 4NQO and monitored activation of the checkpoint by looking at Rad53 phosphorylation, which is detectable as a mobility shift in SDS/PAGE (20). In cells transformed with the empty vector (pEG202), Rad53 is normally phosphorylated, whereas expression of the Mec3 bait totally prevented Rad53 phosphorylation, mimicking the behavior of a mec3Δ strain (Fig. 1A). The fusion protein (Mec3-dn) is thus capable of inactivating the wild-type Mec3 expressed from the chromosomal locus, behaving as a dominant-negative, in a manner similar to what has been described for a specific hus1 allele (34). The strain carrying the fusion protein also has the same phenotype as a mec3Δ in the intra-S checkpoint, leading to only partial phosphorylation of Rad53 in response to methyl-methane-sulfonate (MMS) treatment (Fig. 1B and refs. 10 and 26). Whereas in G2-arrested mec3Δ cells Rad53 cannot be phosphorylated, unexpectedly, expressing mec3-dn allowed Rad53 phosphorylation, although to a lower extent compared with wild-type cells (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

mec3-dn overexpression impairs Rad53 phosphorylation in G1 and S, but not in G2. Rad53 phosphorylation was analyzed by Western blotting in extracts obtained from cultures treated as follows. (A) Cells were arrested in G1 with α-factor and half of the culture was treated with 4NQO. (B) Cells were arrested in G1 with α-factor and released in the presence or absence of MMS (0.02%) for 1.5 h. (C) Cells were arrested in G2 with nocodazole and then half of the culture was treated with 4NQO. After the treatment, cells were lysed with TCA, and proteins were separated by SDS/PAGE. The experiment was performed by using wild-type K699 cells transformed with the plasmid expressing the mutant mec3-dn (pM3.10) or the empty pEG202 vector. YLL335 [pEG202], carrying a deletion of the MEC3 gene, was used as control. An aspecific band revealed by the antibodies that can be used as loading control is indicated by *.

We next analyzed the effect of this mutant on the final outcome of DNA-damage checkpoint activation, the control of cell-cycle progression. We treated wild-type cells expressing the mec3-dn or carrying the empty vector with UV light (not shown) or 4NQO, released them from a G1 arrest, and analyzed their DNA content by flow cytometry. Fig. 2A shows that cells expressing the fusion protein do not arrest at the G1/S phase transition in response to DNA damage; in fact, they start accumulating a 2C DNA content at 60–90 min after the release, whereas in cells carrying the empty vector, S-phase entry is normally prevented.

Figure 2.

mec3-dn interferes with the G1/S and intra-S but not with the G2/M DNA-damage checkpoint. (A) Wild-type cells transformed with pM3.10 plasmid or pEG202 vector were arrested in G1 with α-factor. Cultures were treated with 4NQO (1 μg/ml) or left untreated and then released from the G1 arrest. For intra-S checkpoint analysis, 0.02% MMS was added to the medium after the release. Samples were taken every 30 min, and DNA content was estimated by FACS. (B) mec3Δ [pEG202] (●) and wild-type cells carrying pM3.10 plasmid (▴) or pEG202 vector (■) were arrested in G2 with nocodazole, UV-irradiated (40 J/m2), and released from the block. Samples were taken every 15 min, cells were stained with DAPI, and nuclear division was monitored by microscopic analysis. (C) Cells from the strains described in B were blocked in G1 or G2, spread onto selective plates, and UV-irradiated as indicated. Survival was estimated by counting the colony forming units after 3-days incubation.

When α-factor-arrested wild-type cells are released in the presence of sublethal amounts of the alkylating agent MMS, they slow down S-phase progression because of activation of the intra-S checkpoint (35). We found that cells expressing the lexA-9MYC-MEC3 fusion were as defective as mec3Δ cells in slowing DNA synthesis when treated with MMS (Fig. 2A and ref. 30).

Next, we looked at the G2/M checkpoint, which prevents completion of mitosis in cells that have suffered genomic insults. Nocodazole-arrested cells were treated with DNA-damaging agents, and the percentage of cells arrested at the metaphase–anaphase transition, an indication of checkpoint activation, was evaluated by following nuclear division by 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining after release from the block. In this case, cells expressing mec3-dn showed a delayed nuclear division and, thus, a functional G2/M checkpoint like cultures containing the empty vector, whereas the MEC3 deletion abolished this delay (Fig. 2B). Therefore, the G2 checkpoint is not altered in the mec3-dn mutant. The significance of these results is supported by the analysis of the lethality induced by genotoxic treatment. In fact, mec3-dn causes sensitivity to DNA damage in G1 and S, whereas it doesn't influence sensitivity of G2 cells (Fig. 2C and data not shown). We also observed that a 9MYC-MEC3 fusion behaved identically to the original lexA-9MYC-MEC3, suggesting that the defect is not caused by the presence of the LexA moiety but is likely related to the negatively charged domain contributed by the 9MYC tag inserted at the N terminus of Mec3. Interestingly, the Rad53 phosphorylation defect does not require overexpression of the mutant protein because it is also present when 9MYC-MEC3 replaces the wild-type gene at its chromosomal locus (not shown); moreover, these data exclude the possibility that the results may be influenced by the presence of the wild-type protein. Finally, immunoprecipitation studies revealed that the Mec3 mutant protein replaces its wild-type counterpart in the Rad17 complex not only in G1, but also in G2, where the checkpoint is still functional (unpublished observation).

In conclusion, this mec3 mutant is capable of interfering with the DNA-damage response of an otherwise wild-type strain in G1 and in S phase, whereas it doesn't seem to have an effect in G2, thereby defining a difference in the requirements for checkpoint function in the various phases of the cell cycle. The simplest explanation for such a phenotype is that the mec3-dn mutation could be hypomorphic, and, thus, it reveals a different threshold for checkpoint activation in G1 and G2; however, other interpretations are also possible (see Discussion).

The Mutated Rad17 Complex Does Not Prevent Mec1 Activation and Consequent Ddc1 Phosphorylation.

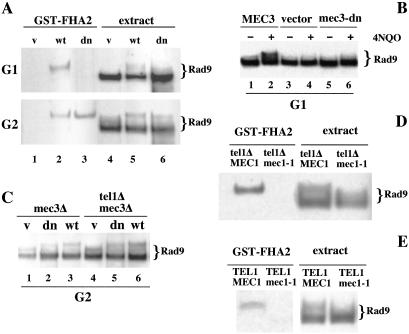

Having observed a defective Rad53 phosphorylation in mec3-dn cells, and because the Rad17-Mec3-Ddc1 complex is often considered to be a sensor of DNA damage, we wanted to investigate what step of the signal-transduction cascade was affected. We first analyzed an early step in the pathway: Ddc1 phosphorylation. mec3Δ cells carrying plasmids expressing either mec3-dn or wild-type MEC3, or carrying the empty vector, were arrested in G1 or G2 and then treated with genotoxic agents. Fig. 3A shows that mec3-dn does not prevent Ddc1 phosphorylation both in G1, where it is defective in Rad53 activation, and in G2, where the checkpoint doesn't seem to be affected by the mutation. A similar experiment has shown that Ddc2/Lcd1 can also be phosphorylated in G2 mec3-dn cells (not shown). The exhibit in Fig. 3 seems to suggest that Ddc1 may be slightly less phosphorylated under these conditions; this may be the case, although the data are variable between different experiments and may be caused by a partial alteration of the structure of the complex because of the mutation. This phosphorylation of Ddc1 exhibits all of the known genetic requirements, because it is Mec1-dependent, Rad24-dependent, and Rad9-independent (Fig. 3B and not shown), excluding the possibility that it may be attributable to a different pathway. These data prove that the defect imparted by mutating the Rad17 complex is not abolishment of Mec1 kinase activity. The step affected by this mutation is indeed downstream in the pathway, between Ddc1 and Rad53 phosphorylation.

Figure 3.

A mec3-dn strain is proficient in phosphorylating Ddc1. (A) mec3Δ cells, expressing either wild-type MEC3 or mec3-dn, were arrested in G1 and G2 and treated with 4NQO. Proteins were analyzed by Western blotting with the indicated antibodies. A strain with the same genetic background but carrying the empty pNB187 vector was used as a control. (B) Cells carrying different mutations in checkpoint genes and transformed with the plasmids expressing either MEC3 (wt) or mec3-dn (dn) were arrested in G1 and G2 and treated with 4NQO. The intra-S checkpoint response was analyzed by releasing an aliquot of the same culture in the presence of MMS (0.02%) for 1.5 h. Rad53 and Ddc1 phosphorylation were monitored by Western blotting.

Expression of mec3-dn Interferes with Rad9 Phosphorylation and with Its Association with Rad53.

Because we found that Mec1 is activated by DNA damage in the mec3 mutant, as shown by Ddc1 phosphorylation, but because Rad53 is not phosphorylated, we investigated the interaction between Rad9 and Rad53. It has, in fact, been reported that after DNA damage, Rad9 is phosphorylated and, in this state, it interacts with the FHA2 domain of Rad53, a crucial event for Rad53 activation (25, 27, 36).

We tested the ability of Rad9 to associate with Rad53 in the presence of the mutant Rad17 complex, both in G1 and in G2. Purified GST-FHA2 was added to crude extracts obtained from Rad9-tagged cells arrested with α-factor or nocodazole and damaged with 4NQO. Proteins associated with GST-FHA2 were recovered with glutathione-Sepharose and analyzed by Western blotting. Fig. 4A shows that GST-FHA2 captures only the slower migrating form of Rad9 (lanes 2 and 5 in Fig. 4A), as previously shown (27, 36), and this is independent of the cell cycle stage. Interestingly, the presence of mec3-dn does not alter the interaction of Rad9 with the Rad53-FHA2 domain in G2-damaged cells, whereas the same interaction is abolished in G1 (Fig. 4A, lane 3).

Figure 4.

Expression of the mec3-dn in G1 abolishes Rad9 phosphorylation and impairs its interaction with Rad53. (A) mec3Δ cells carrying MYC-tagged RAD9 at its chromosomal locus (YMIC5C4) and transformed with pNB187 vector (v), pNB187-MEC3 (wt), or pNB187-mec3-dn (dn) were arrested in G1 and G2 and treated with 4NQO. Native extracts were incubated with GST-FHA2, and proteins recovered with glutathione-Sepharose were analyzed by immunoblotting with 9E10 antibodies. TCA extracts were run on the same gel as controls. (B) YMIC5C4 cells transformed with the same plasmids as in A were arrested in G1 and treated with 4NQO. Rad9 phosphorylation was analyzed by Western blotting. (C) A YMIC5C4 strain and a derivative, carrying a TEL1 deletion, were transformed with the plasmids indicated in A. Cells were arrested in G2 and damaged with 4NQO. Rad9 phosphorylation was analyzed as described. (D) A YMIC5C4 tel1Δ and a derivative, also carrying the mec1–1 mutation, were transformed with pNB187-mec3-dn, arrested in G2, and treated with 4NQO. Native extracts were incubated with GST-FHA2 and analyzed as described above. (E) The same experiment as in D but performed on YMIC5C4 and an mcc1-1 derivative, both harboring pNB187-mec3-dn.

Because it has been shown that Rad53 interacts with Rad9 only when the latter is phosphorylated (22, 26, 27), we checked the status of Rad9 phosphorylation in our genetic background. Cells arrested in G1 or G2 expressing wild-type MEC3, mec3-dn, or no MEC3 in a mec3Δ strain were treated with genotoxic agents, and Rad9 phosphorylation was analyzed by Western blotting. As expected, a wild-type Rad17 complex is required for Rad9 phosphorylation in G1 (Fig. 4B lanes 1–4). The presence of mec3-dn abolishes Rad9 phosphorylation in G1 (Fig. 4B, lanes 5, 6), suggesting that Mec1 kinase, even though active on Ddc1, does not recognize Rad9 as a target under these conditions. This finding also provides an explanation for the failure to recover Rad9 in GST-FHA2 pull-down in G1 cells. As reported by others (26), in G2 cells there is a partial modification of Rad9 that does not depend on the Rad17 complex (Fig. 4C, lane 1). By using modified electrophoretic conditions, we observed a hyperphosphorylated form of Rad9 that also requires the Rad17-group of proteins in G2 (Fig. 4C; compare lanes 1 and 3), revealing the existence of two levels of phosphorylation that exhibit different genetic requirements. Only the slowest form, dependent on the Rad17 complex, is capable of interacting with the FHA2 domain of Rad53 (Fig. 4A; compare lanes 1 and 4 to 2 and 5), suggesting that this second level of phosphorylation is critical for checkpoint function. In the presence of the mec3-dn mutant, Rad9 is well hyperphosphorylated in G2, where it mimics the wild-type situation.

Altogether, these data demonstrate that in mec3-dn mutant cells, the G1 signal-transduction cascade responsible for DNA-damage checkpoint is blocked downstream of the Rad17 complex, where Rad9 gets hyperphosphorylated. This evidence provides an explanation for the effect of the mutant complex on Rad53 phosphorylation and demonstrates that the interaction between FHA2 and Rad9 strictly requires MEC3 (Fig. 4A, lanes 1 and 2).

Activation of Rad53 in G2 mec3-dn Cells Depends on TEL1.

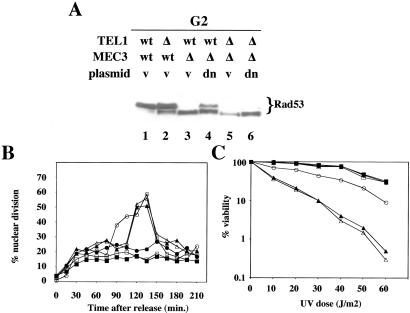

The data presented so far suggest that, in this mutant background, Mec1 cannot phosphorylate Rad9 and Rad53 in G1. The G2-checkpoint proficiency observed in a mec3-dn strain, therefore, could be caused by different kinases that partially bypass the function missing because of the mutated complex, and whose role might be normally obscured by the activity of Mec1. We investigated a possible role for Tel1, the yeast homologue of ATM, in the G2 checkpoint by analyzing Rad9 and Rad53 phosphorylation in tel1Δ mec3Δ cells bearing the empty vector, the MEC3 or the mec3-dn plasmid, after treatment with 4NQO in G2. Fig. 4C shows that Rad9 phosphorylation was identical in single mec3-dn or in double mec3-dn tel1Δ mutant cells (Fig. 4C; compare lanes 2 and 3 to 5 and 6), indicating that, in our experimental conditions, TEL1 is not involved in Rad9 modification and its interaction with Rad53, which require MEC1 (Fig. 4 D and E). On the contrary, in mec3-dn cells, Tel1 plays an unexpected role in Rad53 phosphorylation. Fig. 5A shows that Tel1 is required for Rad53 activation in these mutant cells (compare lanes 4 and 6), whereas its contribution is scarcely detectable in wild-type cells (compare lanes 1 and 2). The role of Tel1 in these conditions is critical; in fact, deletion of TEL1 in these cells causes a G2/M checkpoint defect (Fig. 5B) and an increased sensitivity to UV damage (Fig. 5C), confirming an important physiological role for the observed phosphorylation.

Figure 5.

G2 Rad53 phosphorylation in a mec3-dn background requires TEL1. (A) Wild type, tel1Δ, mec3Δ, and mec3Δ tel1Δ cells transformed with the pEG202 vector (v) or pM3.10 plasmid (dn) were arrested in G2. After 4NQO treatment, Rad53 phosphorylation was analyzed by Western blotting. (B) MEC3 TEL1 (■), MEC3 tel1Δ (□), mec3Δ TEL1 (▴), and mec3Δtel1Δ (▵) strains were transformed with the pEG202 vector. mec3Δ TEL1 (●) and mec3Δ tel1Δ (○) were transformed with the pM3.10 plasmid. Cells were arrested with nocodazole, UV-treated, and released from the block; samples were taken at the indicated time-points. Activation of the G2/M checkpoint was evaluated by estimating nuclear division by DAPI staining. (C) Sensitivity to the treatment was evaluated by plating.

These observations suggest that in mec3-dn G2-arrested cells, Mec1 is still responsible for phosphorylating Rad9 and allowing its interaction with Rad53, but Rad53 cannot be activated unless Tel1 is present. This effect is likely caused by a defect in recruiting Rad53 to Mec1 for transphosphorylation.

The observation that mec3-dn tel1Δ cells, even though completely defective in the G2/M checkpoint, display only a partial sensitivity to UV treatment is intriguing. Because survival after genotoxic treatment requires not only checkpoint activation but also DNA repair and proper cell cycle recovery, one could speculate that the mec3-dn mutant, although affecting the checkpoint function of the Rad17 complex, may be proficient in an additional role of Mec3.

Discussion

Rad17, Mec3, and Ddc1 form a heterotrimeric complex required for a fully functional DNA-damage checkpoint activation in G1, S, and G2, resulting in Rad53 hyperphosphorylation (2, 11). Deletion of any of the three genes impairs Rad53 activation and causes a defective control of cell-cycle progression after DNA damage, leading to hypersensitivity to genotoxic agents and increased genomic instability (4–6).

We generated an MEC3 hybrid gene that disrupts the functionality of the G1 and intra-S DNA-damage checkpoints. Mutant cells are defective in G1 DNA damage-induced Rad53 phosphorylation and, like mec3Δ cells, fail to delay S-phase entry and progression, resulting in increased sensitivity when UV irradiated in G1. Surprisingly, the same mutation does not affect the G2 checkpoint; in fact, Rad53 phosphorylation was only mildly affected, and nuclear division was delayed normally after treating G2-arrested mec3-dn cells with genotoxic agents. Consequently, they do not display increased sensitivity to UV irradiation. The intermediate level of sensitivity exhibited when the mutant strain is damaged in G1 is likely caused by the fact that, if these cells succeed in going through S phase, they can then arrest in G2 and repair the lesions, because the G2 checkpoint is functional. Analysis of the composition of the Rad17 complex revealed that Mec3-dn replaces wild-type Mec3, generating a mutated Rad17 complex both in G1, when the mutation impairs checkpoint function, and also in G2, when the signal transduction cascade is still functional (unpublished work).

Altogether, these data suggest that the requirements for activation of the signal-transduction cascade may be different in the various phases of the cell cycle. It is likely, although difficult to verify, that mec3-dn is a hypomorphic mutant. This mutation would cause a reduced activity of the Rad17 complex and suggests that different thresholds for the activation of the checkpoint in G1 and G2 may exist. Another intriguing possibility lies in the need for alternative partners of the Rad17 complex in various phases of the cell cycle.

We have shown that the presence of a mutant Rad17 complex impairs the ability of Mec1 to induce Rad53 phosphorylation after DNA damage in G1 or S phase. Thus, it is possible that the modification of Rad53 observed in G2 mutant cells is caused by different kinases, such as Chk1 or Tel1, that, in these particular conditions, may be able to bypass partially the absence of some Mec1 function. We found that Chk1 does not affect Rad53 phosphorylation (see Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site), demonstrating that there is no evident cross talk between the Chk1 and the Rad53 branches of the pathway. Whereas Tel1 plays only a minor role in Rad53 phosphorylation when the Mec1 pathway is fully functional, expression of mec3-dn, that partially affects Mec1 function, uncovers a novel role for Tel1 in Rad53 activation. Under these conditions deletion of TEL1 practically eliminates Rad53 phosphorylation and abolishes the G2/M checkpoint. Interestingly, recent results showed that accumulation of unprocessed double strand breaks in mitotic cells causes hyperactivation of a previously uncharacterized pathway (TM), which depends on TEL1 but does not require Mec1 or the Rad24 group of proteins, leading to Rad53 phosphorylation (37). In our experimental conditions, we uncovered a role for Tel1 in Rad53 activation which still requires Rad24 and a Mec1-dependent Rad9 phosphorylation, implying that expression of mec3-dn does not activate the TM pathway. These findings are in agreement with intriguing results showing that the so-called rad50S checkpoint in meiotic cells requires Rad24, Rad9, Mec1, and also Tel1 (37). We thus suggest that Tel1 might play a role in both the TM and the Mec1-dependent checkpoint pathways.

Thanks to genetic and phosphorylation data, it had been proposed that Rad9, Rad24, Rad17, Mec3, and Ddc1 act upstream of Mec1 (4, 24). After DNA damage, Ddc1 is phosphorylated in a Mec1-dependent manner, and this phosphorylation is defective both in mec3Δ and in rad17Δ cells, suggesting a role for this complex in Mec1 activation. However, recent results showed that, in response to genotoxins, Mec1 can phosphorylate a tightly associated subunit (Ddc2/Lcd1) even in the absence of the Rad17 complex (21, 22, 28), and that Mec1 and Rad17 complex are independently recruited to the site of the lesion (38, 39). Here, we show that if the Rad17 complex contains a mutated Mec3 protein—which renders Mec1 incapable of phosphorylating Rad53 in G1—Ddc1 is still phosphorylated by Mec1. This phosphorylation is not observed in a mec3Δ or rad17Δ background probably because, in these conditions, Ddc1 is not assembled in a complex, resulting in a poor substrate for the kinase (11, 24).

We have demonstrated that, in a mec3-dn strain, DNA alterations are actually sensed, and the signal is transmitted as far as Ddc1 but doesn't reach Rad53 in G1. It has been shown that Rad53 is physically associated with Rad9 and that this interaction is necessary for Rad53 hyperphosphorylation (26, 27). Our results show that, in G1 cells expressing the mec3-dn mutation, this interaction is not observed, whereas it is maintained in G2 cells. Moreover, the Rad9–Rad53 interaction is impaired in a mec3Δ strain, suggesting that it requires the Rad17 complex in all phases of the cell cycle. As previous work had shown that in a mec3Δ background, Rad9 phosphorylation is abolished in G1 but not in G2, and because Rad53 interacts only with phosphorylated Rad9 (26), we wondered whether mec3-dn cells also were defective in Rad9 phosphorylation. This is indeed the case; in fact, in G1 cells expressing mec3-dn, the modified form of Rad9 is not visible. This result explains why, in these conditions, Rad53–Rad9 interaction is undetectable. In G2, our data show that in a mec3-dn strain, Rad9 can be normally phosphorylated in a Mec1-dependent manner. It is important to note that, even if there is a certain amount of Rad9 phosphorylation that does not depend on the Rad17 complex (26), it is not likely to be enough for checkpoint activation, because a mec3Δ strain does not activate Rad53 (10, 26). By using modified electrophoresis conditions, we found that there is a second level of damage-induced Rad9 phosphorylation, which depends on MEC3 instead. This second level of modification is probably the critical one for checkpoint function. In fact, this is the only form of Rad9 that can associate with the Rad53-FHA2 domain and that is restored, together with Rad53 activation, by expressing mec3-dn or wild-type MEC3 in a mec3Δ strain.

Having identified a role for Tel1 in Rad53 activation, we tested whether Tel1 was also responsible for Rad9 modification in mec3-dn G2 cells. We found that in G2-arrested mec3-dn cells, a deletion of TEL1 does not affect genotoxin-induced Rad9 phosphorylation, whereas it almost abolishes Rad53 phosphorylation. This observation leads us to speculate that Tel1 might act directly on Rad53, possibly by setting it up for the Rad9-mediated cycle of autophosphorylation events that normally require a transphosphorylation by Mec1. We propose that the mutant Rad17 complex might be defective in recruiting Rad53 to Mec1. In these conditions, where the Mec1 kinase activity is present and the Rad17 complex is presumably dysfunctional, Rad53 can be transphosphorylated through Tel1 activity. This step is then followed by Rad53 autophosphorylation, which requires its interaction with Mec1-phosphorylated Rad9.

As we have shown that in cells containing a mutated Rad17 complex, Mec1 is able to phosphorylate both Ddc1 (both in G1 and G2) and Rad9 (only in G2, not in G1) but not Rad53 (both in G1 and in G2), we think that the mec3-dn mutation may alter the target selectivity of Mec1 kinase. We propose that the actual role of the Rad17 complex could be the recruitment onto DNA of different factors, including various Mec1 substrates. It is likely that proteins like Mec1, functioning as regulators of different pathways, will be associated with protein complexes providing immediate access to downstream effectors. Indeed size fractionation studies indicate that ATR and ATM are associated in high molecular weight complexes with some of their targets (40). Another option is that the complex might modify the chromatin structure around the lesion so that Rad9 and Rad53 can be recruited and phosphorylated. As previously mentioned, if mec3-dn is hypomorphic, it would be possible to envision that the level of activity of the Rad17 complex needed by the cell to recruit Mec1 substrates might be different in various phases of the cell cycle. Alternatively, the complex containing Mec3-dn might be defective as an adaptor for Mec1 substrates, and this explains its defect in G1 and intra-S DNA-damage checkpoints. In G2, either a different partner or a different subunit of the Rad17 complex may be involved in recruiting Mec1 targets, thus allowing Rad9 phosphorylation. We further propose (see Fig. 6) that Rad53 can be transphosphorylated by both Mec1 and Tel1, although in wild-type cells, the role of Tel1 is masked by Mec1 activity. In the mec3-dn background, G2 cells are defective in the phosphorylation that Mec1 contributes to Rad53 and thus its activation rests mainly on Tel1. Once Rad53 is primed by Mec1/Tel1, and Rad9 is phosphorylated by Mec1, the autokinase activity of Rad53 can lead to its hyperphosphorylation. The mec3-dn is the only mutant available that leaves the Mec1 branch phosphorylating Rad9 unaffected, whereas it impedes Rad53 phosphorylation by Mec1, thus revealing the role of Tel1 in modulating Rad53 activation.

Figure 6.

A model for the DNA-damage-activated signal transduction cascade. In response to DNA damage, the Rad17 complex is required for the recruitment and hyperphosphorylation of Rad9 by Mec1. This event is necessary to promote Rad53–Rad9 interaction. Subsequently, Mec1 transphosphorylates Rad53 in a step that requires Rad17 complex; Tel1 has only a minor role in Rad53 phosphorylation. All of these steps lead to autophosphorylation and activation of Rad53 (a). When the mec3-dn mutation renders the Rad17 complex defective, the Rad9-phosphorylation branch is still functional in G2 cells, allowing formation of the Rad9–Rad53 complex. In these conditions, Mec1 cannot activate Rad53; hence, a role for Tel1 is uncovered (b). (c) In a mec3Δ situation, Rad9 cannot be phosphorylated; thus, Rad53 activation cannot be achieved.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M. P. Longhese, D. Stern, A. Pellicioli, and S. Healy for strains and plasmids, and we also thank N. Landsberger, G. Bertoni, and all members of the lab for stimulating discussions. We thank C. Santocanale for kindly providing Rad53 antibodies and D. Stern for helping with the GST-FHA2 pull-down. This work was supported by grants from Associazione Italiana Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC), Cofinanziamento Ministero dell'Universitá e della Ricerca Scientifica e Tecnologica (MURST)-Universita' di Milano, MURST (5%) Biomolecole per la Salute Umana, Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche (CNR) Target Project on Biotechnology, CNR Agenzia 2001, and European Union Contract ERBFMRXCT9701225.

Abbreviations

- 4NQO

4-nitroquinoline oxide

- MMS

methyl-methane-sulfonate

References

- 1.Hartwell L H, Weinert T A. Science. 1989;246:629–634. doi: 10.1126/science.2683079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Longhese M P, Foiani M, Muzi-Falconi M, Lucchini G, Plevani P. EMBO J. 1998;17:5525–5528. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.19.5525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou B B, Elledge S J. Nature (London) 2000;408:433–439. doi: 10.1038/35044005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weinert T. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1998;8:185–193. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(98)80140-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lowndes N F, Murguia J R. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2000;10:17–25. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(99)00050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weinert T. Cell. 1998;94:555–558. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81597-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Longhese M P, Paciotti V, Fraschini R, Zaccarini R, Plevani P, Lucchini G. EMBO J. 1997;16:5216–5226. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.17.5216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weinert T A, Hartwell L H. Science. 1988;241:317–322. doi: 10.1126/science.3291120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de la Torre-Ruiz M A, Green C M, Lowndes N F. EMBO J. 1998;17:2687–2698. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.9.2687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pellicioli A, Lucca C, Liberi G, Marini F, Lopes M, Plevani P, Romano A, Di Fiore P P, Foiani M. EMBO J. 1999;18:6561–6572. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.22.6561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kondo T, Matsumoto K, Sugimoto K. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:1136–1143. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.2.1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thelen M P, Venclovas C, Fidelis K. Cell. 1999;96:769–770. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80587-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Green C M, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Lowndes N F. Curr Biol. 2000;10:39–42. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)00263-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lydall D, Weinert T. Science. 1995;270:1488–1491. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5241.1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garvik B, Carson M, Hartwell L. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:6128–6138. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.11.6128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carr A M. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1997;7:93–98. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(97)80115-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Craven R J, Petes T D. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:2378–2384. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.7.2378-2384.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mallory J C, Petes T D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:13749–13754. doi: 10.1073/pnas.250475697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sanchez Y, Desany B A, Jones W J, Liu Q, Wang B, Elledge S J. Science. 1996;271:357–360. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5247.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun Z, Fay D S, Marini F, Foiani M, Stern D F. Genes Dev. 1996;10:395–406. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.4.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paciotti V, Clerici M, Lucchini G, Longhese M P. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2046–2059. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rouse J, Jackson S P. EMBO J. 2000;19:5801–5812. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.21.5801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wakayama T, Kondo T, Ando S, Matsumoto K, Sugimoto K. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:755–764. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.3.755-764.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paciotti V, Lucchini G, Plevani P, Longhese M P. EMBO J. 1998;17:4199–4209. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.14.4199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Emili A. Mol Cell. 1998;2:183–189. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80128-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vialard J E, Gilbert C S, Green C M, Lowndes N F. EMBO J. 1998;17:5679–5688. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.19.5679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun Z X, Hsiao J, Fay D S, Stern D F. Science. 1998;281:272–274. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5374.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Edwards R J, Bentley N J, Carr A M. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:393–398. doi: 10.1038/15623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Durocher D, Jackson S P. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2001;13:225–231. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00201-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Longhese M P, Fraschini R, Plevani P, Lucchini G. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:3235–3244. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.7.3235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gyuris J, Golemis E, Chertkov H, Brent R. Cell. 1993;75:791–803. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90498-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goud B, Salminen A, Walworth N C, Novick P J. Cell. 1988;53:753–768. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90093-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Allen J B, Zhou Z, Siede W, Friedberg E C, Elledge S J. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2401–2415. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.20.2401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kostrub C F, Knudsen K, Subramani S, Enoch T. EMBO J. 1998;17:2055–2066. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.7.2055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paulovich A G, Hartwell L H. Cell. 1995;82:841–847. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90481-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Durocher D, Henckel J, Fersht A R, Jackson S P. Mol Cell. 1999;4:387–394. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80340-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Usui T, Ogawa H, Petrini J H. Mol Cell. 2001;7:1255–1266. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00270-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kondo T, Wakayama T, Naiki T, Matsumoto K, Sugimoto K. Science. 2001;294:867–870. doi: 10.1126/science.1063827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Melo J A, Cohen J, Toczyski D P. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2809–2821. doi: 10.1101/gad.903501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tibbetts R S, Cortez D, Brumbaugh K M, Scully R, Livingston D, Elledge S J, Abraham R T. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2989–3002. doi: 10.1101/gad.851000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.