Abstract

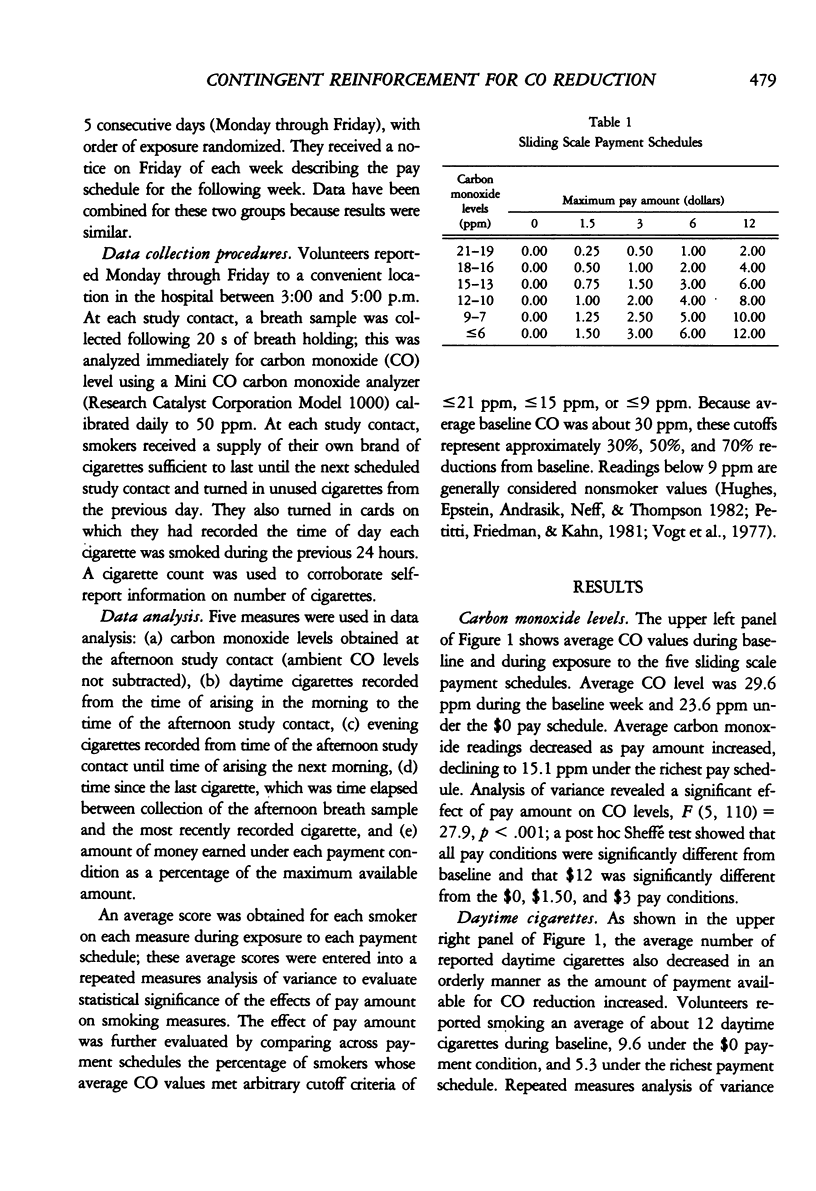

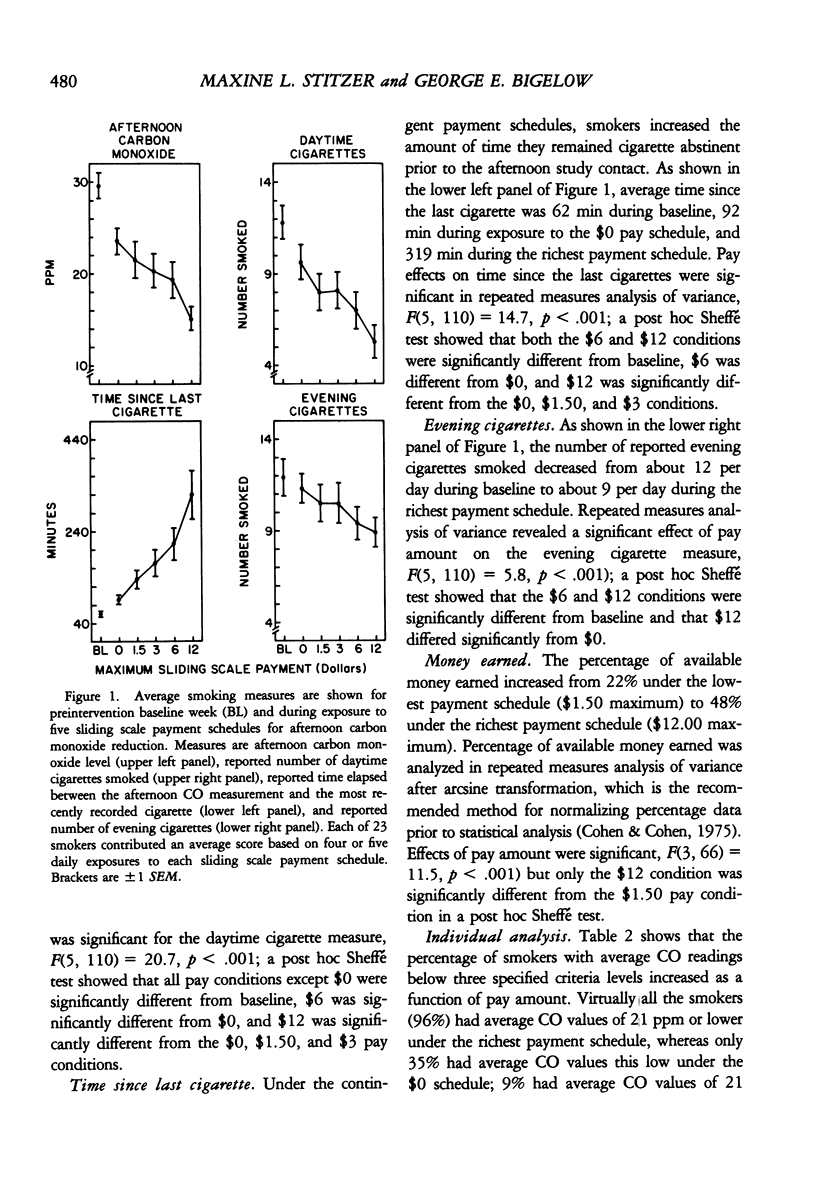

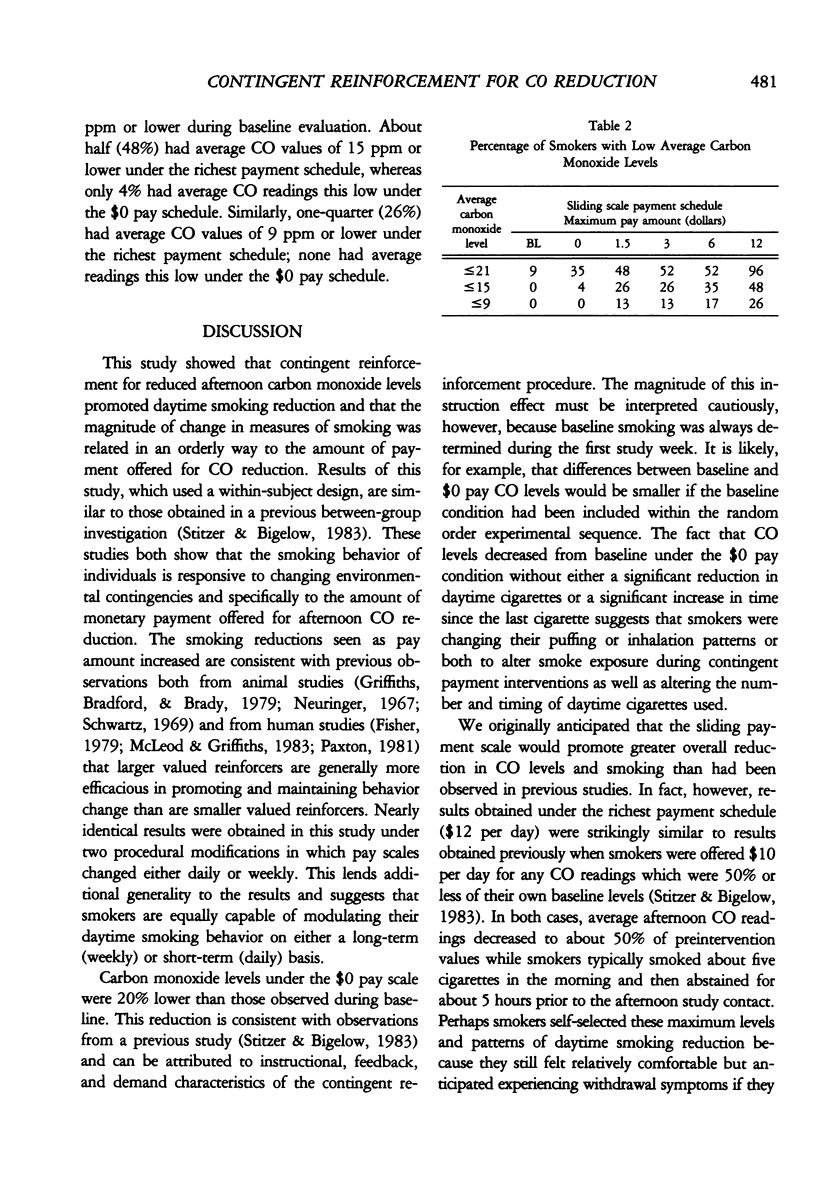

The relationship between reinforcer amount and daytime smoking reduction in smokers offered money for reduced afternoon breath carbon monoxide (CO) levels was examined. Twenty-three hired regular smokers with average baseline CO levels of about 30 ppm were exposed in random order to five sliding scale payment schedules that changed daily or weekly. Money was available for afternoon CO readings between 0 and 21 ppm with pay amount inversely related to the absolute CO reading obtained. Maximum pay amount for readings below 7 ppm varied among $0, $1.50, $3, $6, and $12 per day. Contingent reinforcement promoted CO and daytime cigarette reduction within individuals with the amount of behavior change related to the amount of payment available. Average CO levels decreased from 30 to 15 ppm as a function of pay amount whereas self-reported daytime cigarettes decreased from 12 to 5 per day. Average minutes of cigarette abstinence prior to the afternoon study contact increased from 62 to 319 minutes as a function of pay amount, whereas the percentage of available money earned increased from 22% to 48%. Nontargeted evening cigarette use also decreased during periods of daytime smoking reduction. The orderly effects of this contingent reinforcement intervention on daytime smoking of regular smoker volunteers suggest that this is a sensitive model for continued evaluation of factors that influence smoking reduction and cessation.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Ashton H., Stepney R., Thompson J. W. Should intake of carbon monoxide be used as a guide to intake of other smoke constituents? Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1981 Jan 3;282(6257):10–13. doi: 10.1136/bmj.282.6257.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. I., Perkins N. M., Ury H. K., Goldsmith J. R. Carbon monoxide uptake in cigarette smoking. Arch Environ Health. 1971 Jan;22(1):55–60. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1971.10665815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher E. B., Jr Overjustification effects in token economies. J Appl Behav Anal. 1979 Fall;12(3):407–415. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1979.12-407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths R. R., Bradford L. D., Brady J. V. Progressive ratio and fixed ratio schedules of cocaine-maintained responding in baboons. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1979 Oct;65(2):125–136. doi: 10.1007/BF00433038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henningfield J. E., Stitzer M. L., Griffiths R. R. Expired air carbon monoxide accumulation and elimination as a function of number of cigarettes smoked. Addict Behav. 1980;5(3):265–272. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(80)90049-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horan J. J., Hackett G., Linberg S. E. Factors to consider when using expired air carbon monoxide in smoking assessment. Addict Behav. 1978;3(1):25–28. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(78)90006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes J. R., Epstein L. H., Andrasik F., Neff D. F., Thompson D. S. Smoking and carbon monoxide levels during pregnancy. Addict Behav. 1982;7(3):271–276. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(82)90054-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JONES R. H., ELLICOTT M. F., CADIGAN J. B., GAENSLER E. A. The relationship between alveolar and blood carbon monoxide concentrations during breathholding; simple estimation of COHb saturation. J Lab Clin Med. 1958 Apr;51(4):553–564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebson I. A., Tommasello A., Bigelow G. E. A behavioral treatment of alcoholic methadone patients. Ann Intern Med. 1978 Sep;89(3):342–344. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-89-3-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod D. R., Griffiths R. R. Human progressive-ratio performance: maintenance by pentobarbital. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1983;79(1):4–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00433007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuringer A. J. Effects of reinforcement magnitude on choice and rate of responding. J Exp Anal Behav. 1967 Sep;10(5):417–424. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1967.10-417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxton R. Deposit contracts with smokers: varying frequency and amount of repayments. Behav Res Ther. 1981;19(2):117–123. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(81)90035-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxton R. The effects of a deposit contract as a component in a behavioural programme for stopping smoking. Behav Res Ther. 1980;18(1):45–50. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(80)90068-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petitti D. B., Friedman G. D., Kahn W. Accuracy of information on smoking habits provided on self-administered research questionnaires. Am J Public Health. 1981 Mar;71(3):308–311. doi: 10.2105/ajph.71.3.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RINGOLD A., GOLDSMITH J. R., HELWIG H. L., FINN R., SCHUETTE F. Estimating recent carbon monoxide exposures. A rapid method. Arch Environ Health. 1962 Oct;5:308–318. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1962.10663288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickert W. S., Robinson J. C. Estimating the hazards of less hazardous cigarettes. II. Study of cigarette yields of nicotine, carbon monoxide, and hydrogen cyanide in relation to levels of cotinine, carboxyhemoglobin, and thiocyanate in smokers. J Toxicol Environ Health. 1981 Mar-Apr;7(3-4):391–403. doi: 10.1080/15287398109529990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell M. A., Wilson C., Patel U. A., Feyerabend C., Cole P. V. Plasma nicotine levels after smoking cigarettes with high, medium, and low nicotine yields. Br Med J. 1975 May 24;2(5968):414–416. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5968.414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz B. Effects of reinforcement magnitude on pigeons' preference for different fixed-ratio schedules of reinforcement. J Exp Anal Behav. 1969 Mar;12(2):253–259. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1969.12-253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitzer M. L., Bigelow G. E. Contingent reinforcement for reduced carbon monoxide levels in cigarette smokers. Addict Behav. 1982;7(4):403–412. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(82)90010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitzer M. L., Bigelow G. E., Liebson I. A., Hawthorne J. W. Contingent reinforcement for benzodiazepine-free urines: evaluation of a drug abuse treatment intervention. J Appl Behav Anal. 1982 Winter;15(4):493–503. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1982.15-493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt T. M., Selvin S., Widdowson G., Hulley S. B. Expired air carbon monoxide and serum thiocyanate as objective measures of cigarette exposure. Am J Public Health. 1977 Jun;67(6):545–549. doi: 10.2105/ajph.67.6.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]