Abstract

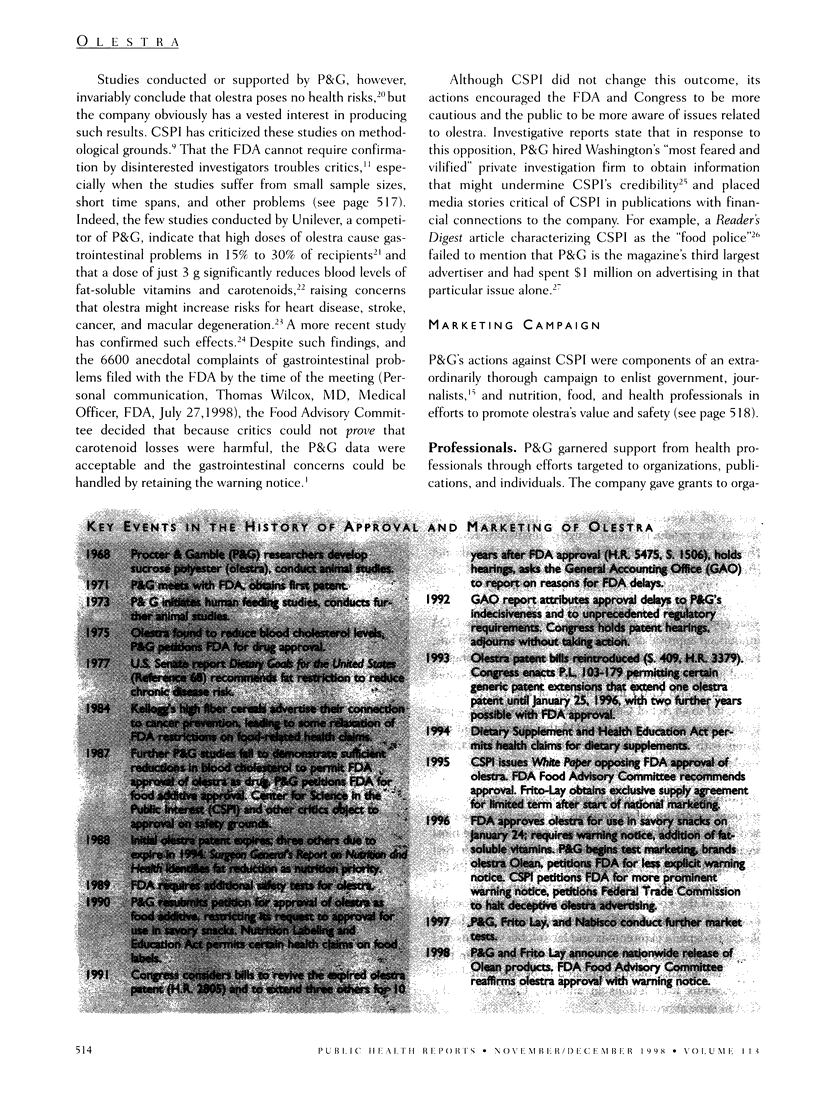

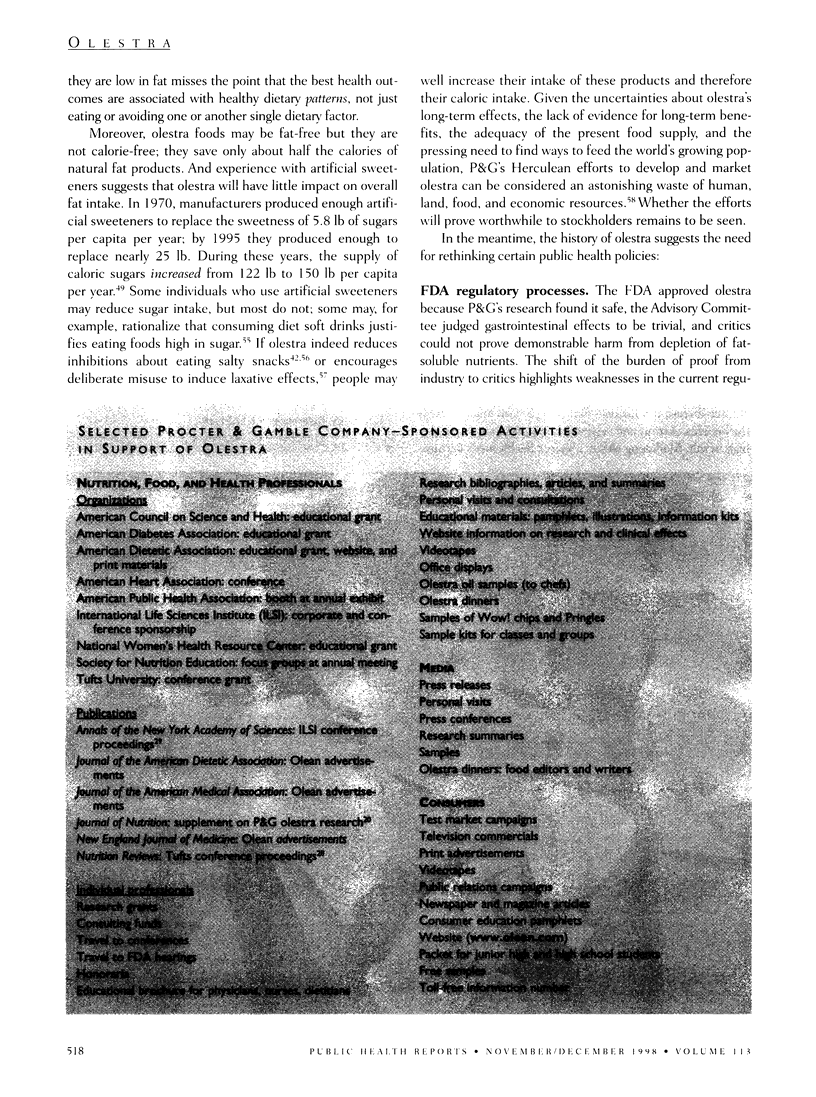

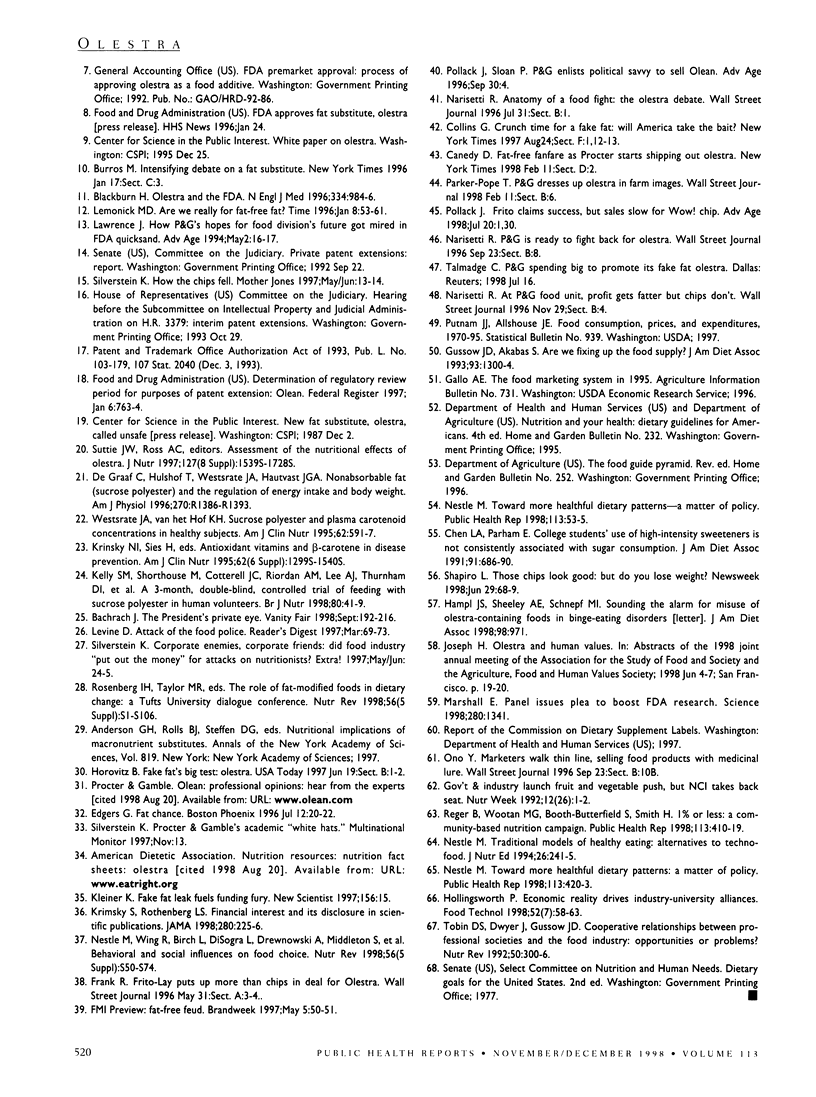

The Procter & Gamble Company spent 30 years and an estimated $500 million to bring its non-digestible fat substitute, olestra, to market. The Food and Drug Administration approved olestra as a food additive but requires products containing olestra to carry a warning statement about its potential effects on gastrointestinal function. In obtaining approval for olestra, P&G conducted a lengthy, persistent, and comprehensive campaign to enlist support from members of Congress; FDA staff; and food, nutrition, and health professionals. This campaign raises larger questions about corporate influence on government policies, and the relationships of corporations to health professionals. To address these larger concerns, the author reviews the history of olestra's approval; describes P&G's campaign to obtain support from FDA and Congress, to defend olestra against critics, and to market it to professionals, the press, and consumers; and suggests implications for public health policies.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Blackburn H. Olestra and the FDA. N Engl J Med. 1996 Apr 11;334(15):984–986. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199604113341511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L. N., Parham E. S. College students' use of high-intensity sweeteners is not consistently associated with sugar consumption. J Am Diet Assoc. 1991 Jun;91(6):686–690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gussow J. D., Akabas S. Are we really fixing up the food supply? J Am Diet Assoc. 1993 Nov;93(11):1300–1304. doi: 10.1016/0002-8223(93)91960-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly S. M., Shorthouse M., Cotterell J. C., Riordan A. M., Lee A. J., Thurnham D. I., Hanka R., Hunter J. O. A 3-month, double-blind, controlled trial of feeding with sucrose polyester in human volunteers. Br J Nutr. 1998 Jul;80(1):41–49. doi: 10.1017/s0007114598001755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krimsky S., Rothenberg L. S. Financial interest and its disclosure in scientific publications. JAMA. 1998 Jul 15;280(3):225–226. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.3.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson K. D., Middleton S. J., Hassall C. D. Olestra, a nonabsorbed, noncaloric replacement for dietary fat: a review. Drug Metab Rev. 1997 Aug;29(3):651–703. doi: 10.3109/03602539709037594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestle M. Toward more healthful dietary patterns--a matter of policy. Public Health Rep. 1998 Sep-Oct;113(5):420–423. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestle M., Wing R., Birch L., DiSogra L., Drewnowski A., Middleton S., Sigman-Grant M., Sobal J., Winston M., Economos C. Behavioral and social influences on food choice. Nutr Rev. 1998 May;56(5 Pt 2):S50–S74. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1998.tb01732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reger B., Wootan M. G., Booth-Butterfield S., Smith H. 1% or less: a community-based nutrition campaign. Public Health Rep. 1998 Sep-Oct;113(5):410–419. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobin D. S., Dwyer J., Gussow J. D. Cooperative relationships between professional societies and the food industry: opportunities or problems? Nutr Rev. 1992 Oct;50(10):300–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1992.tb02472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weststrate J. A., van het Hof K. H. Sucrose polyester and plasma carotenoid concentrations in healthy subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995 Sep;62(3):591–597. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/62.3.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]