Abstract

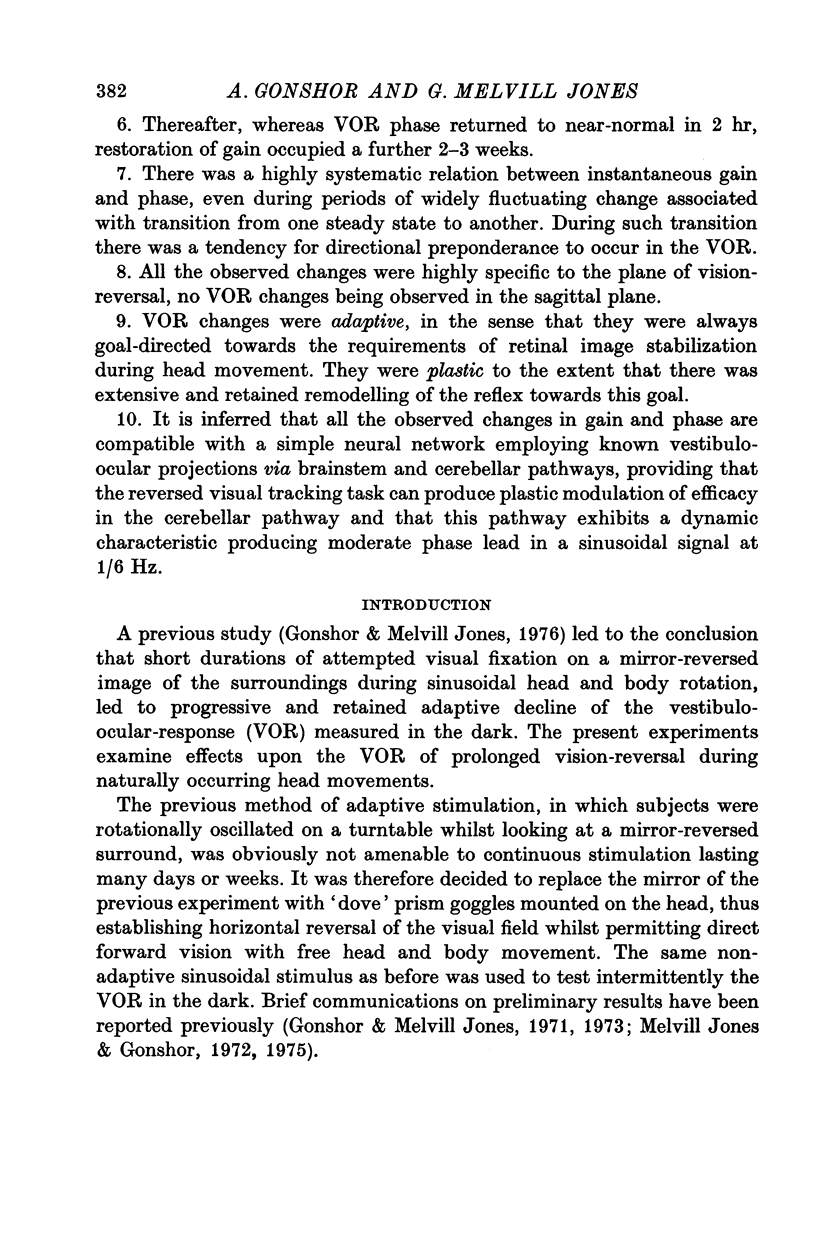

1. These experiments investigated plastic changes in the vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR) of human subjects consequent to long-term optical reversal of vision during free head movement. Horizontal vision-reversal was produced by head-mounted dove prisms. Four normal adults were continuously exposed to these conditions during 2, 6, 7 and 27 days respectively.

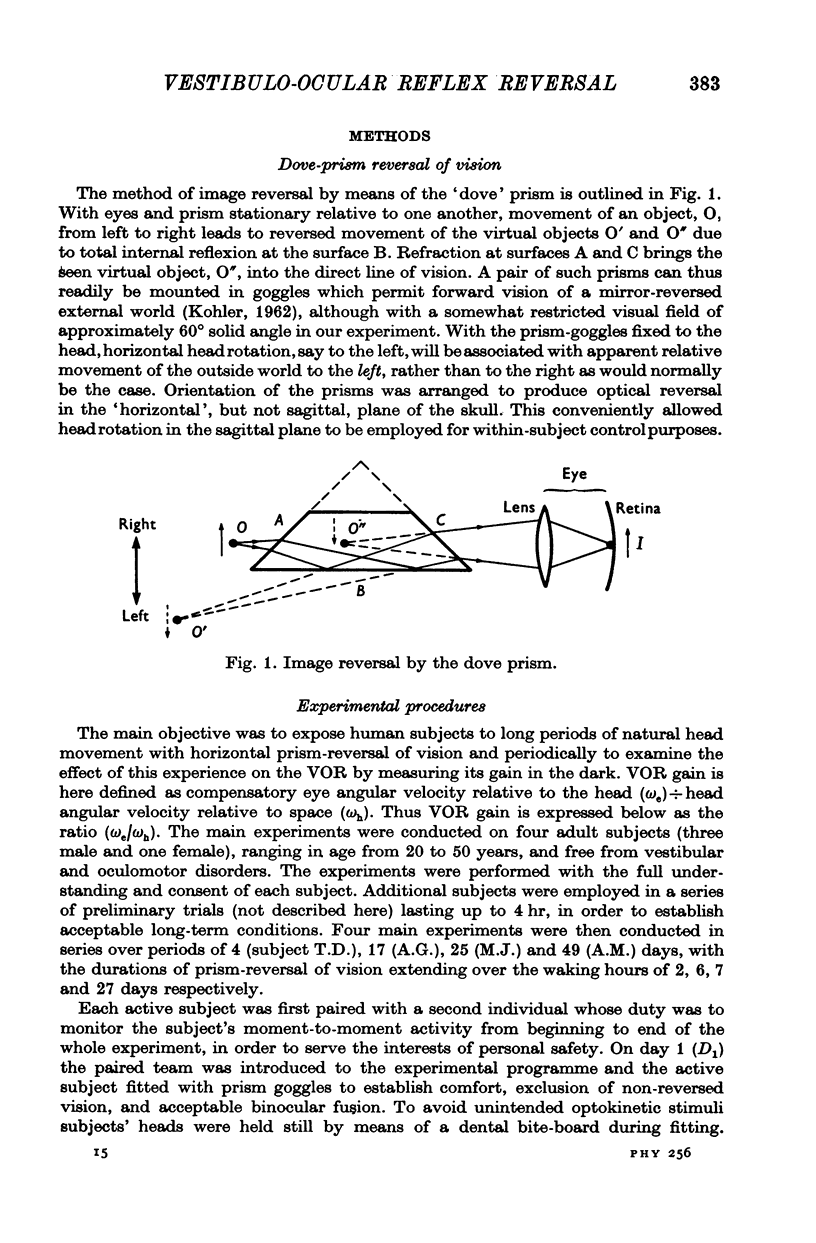

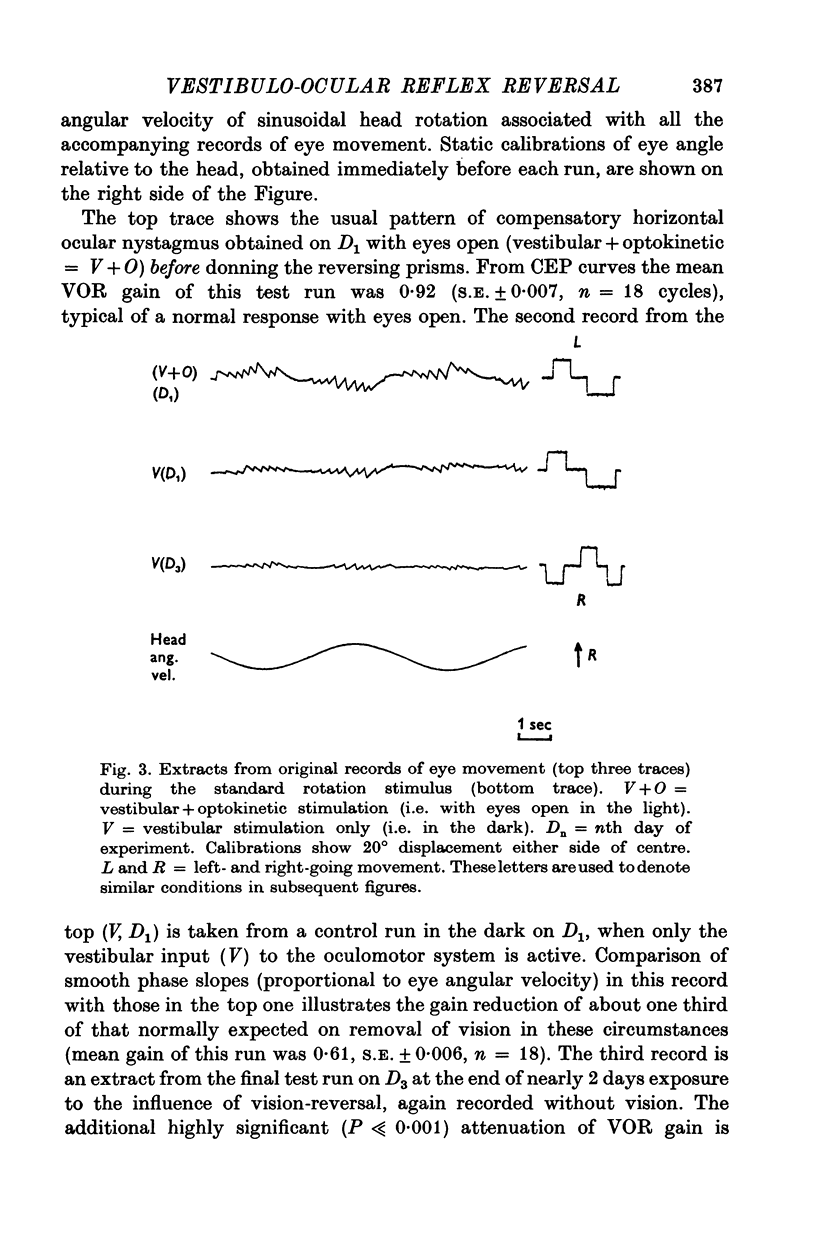

2. A sinusoidal rotational stimulus, previously shown to be nonhabituating (1/6 Hz; 60°/sec amplitude), was used to test the VOR in the dark at frequent intervals both during the period of vision-reversal and an equal period after return to normal vision. D.c. electro-oculography (EOG) was used to record eye movement, taking care to avoid changes of EOG gain due to light/dark adaptation of the retina.

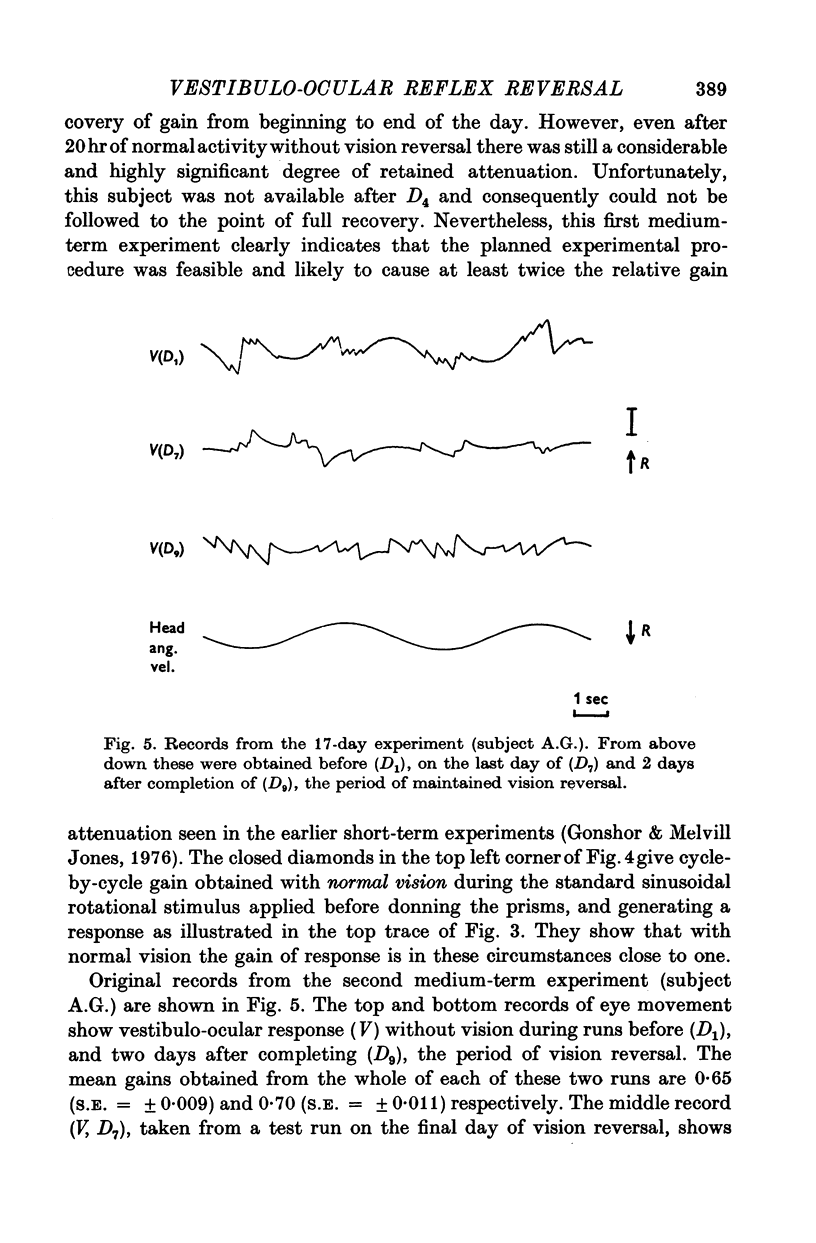

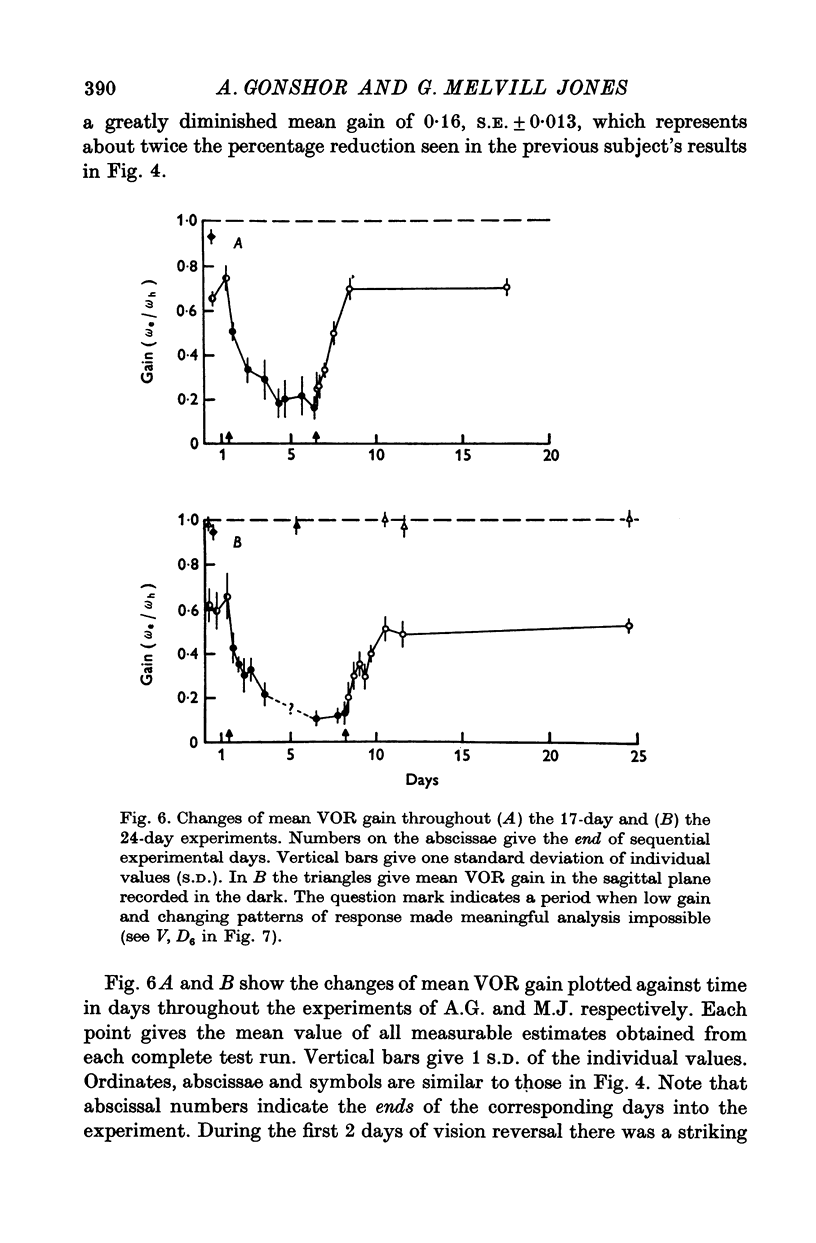

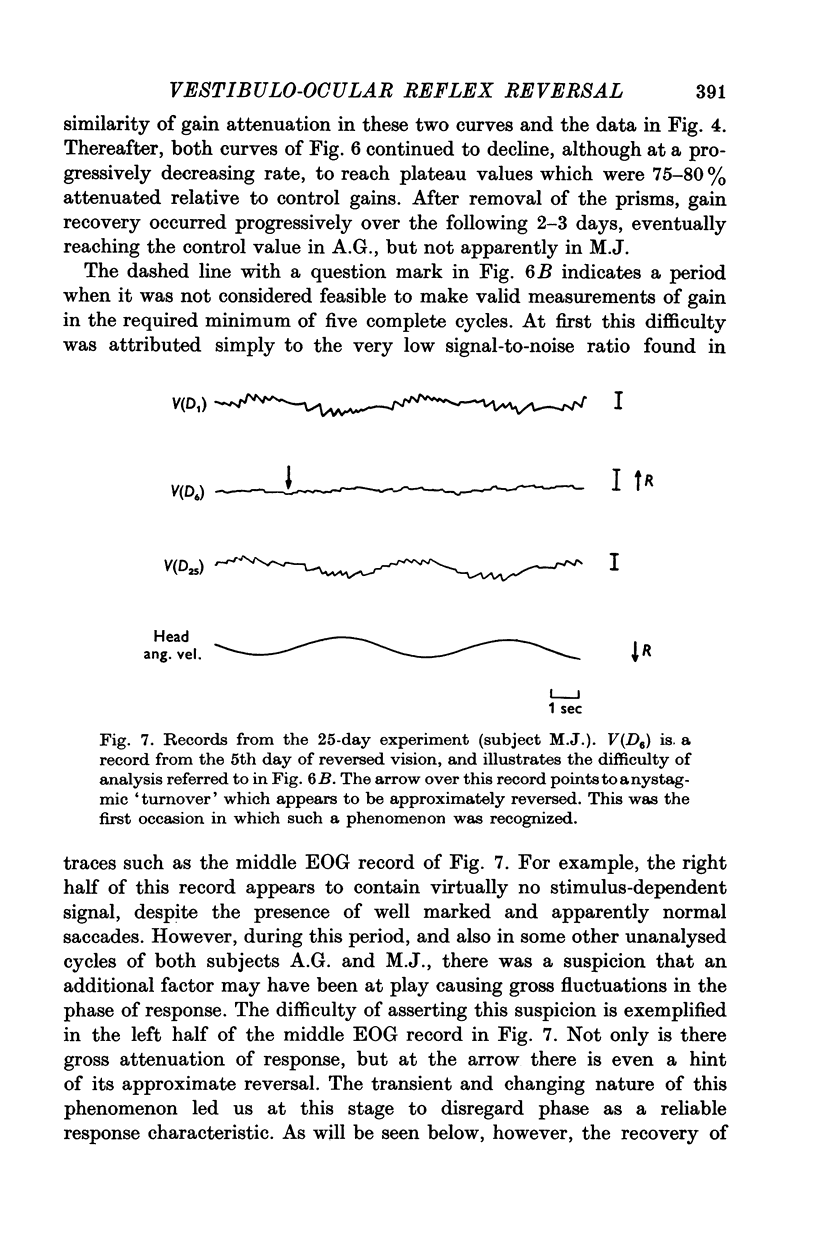

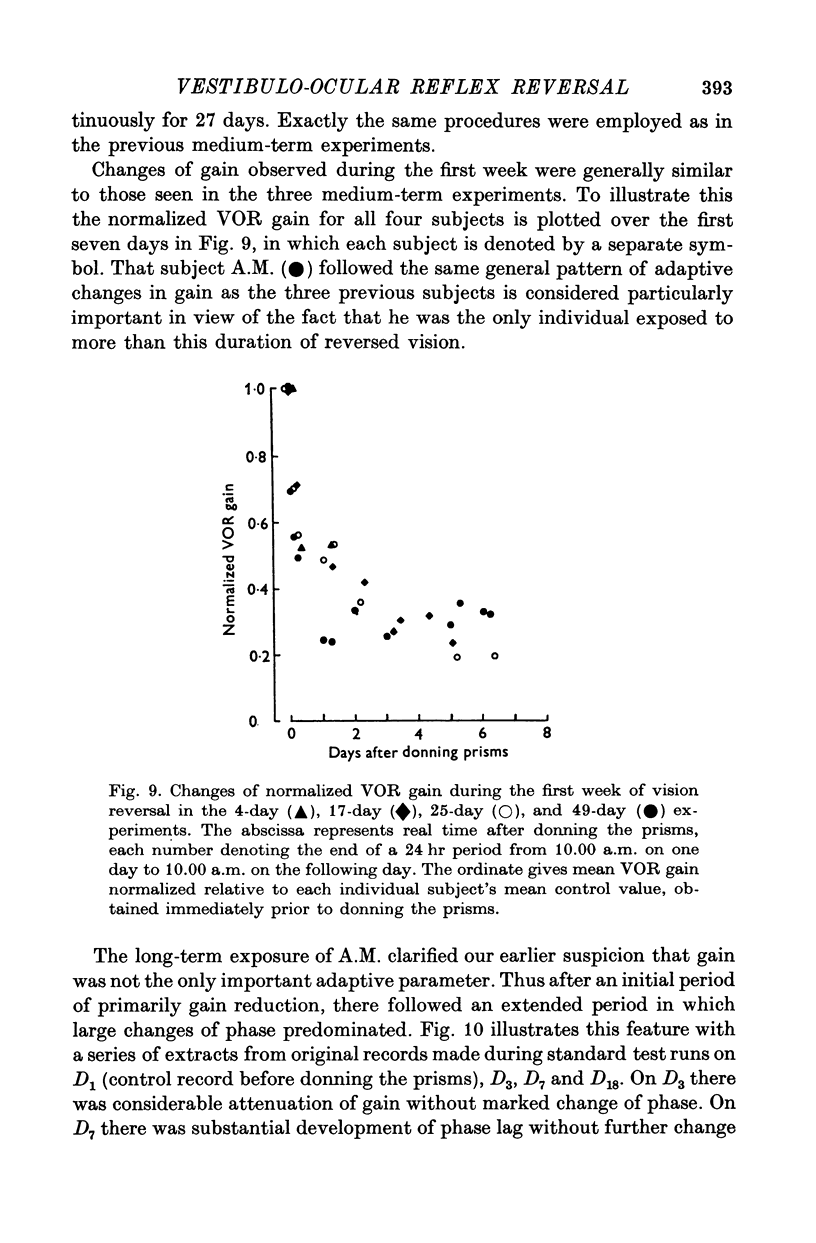

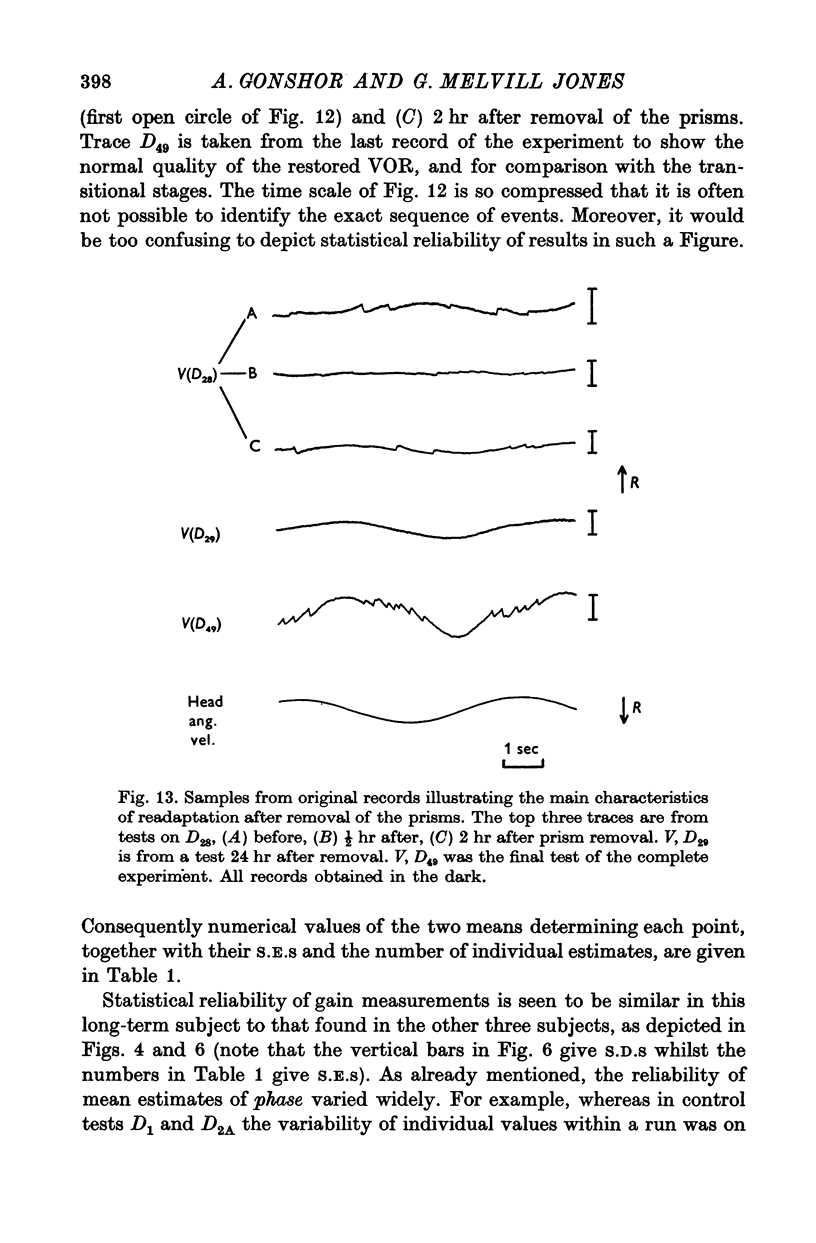

3. All subjects showed substantial reduction of VOR gain (eye velocity/head velocity) during the first 2 days of vision-reversal. The 6-, 7- and 27-day subjects showed further reduction of gain which reached a low plateau at about 25% the normal value by the end of one week. At this time the attenuation of some EOG records was so marked as to defy extraction of a meaningful sinusoidal signal.

4. After removal of the prisms VOR gain recovered along a time course which approximated that of the original adaptive attenuation.

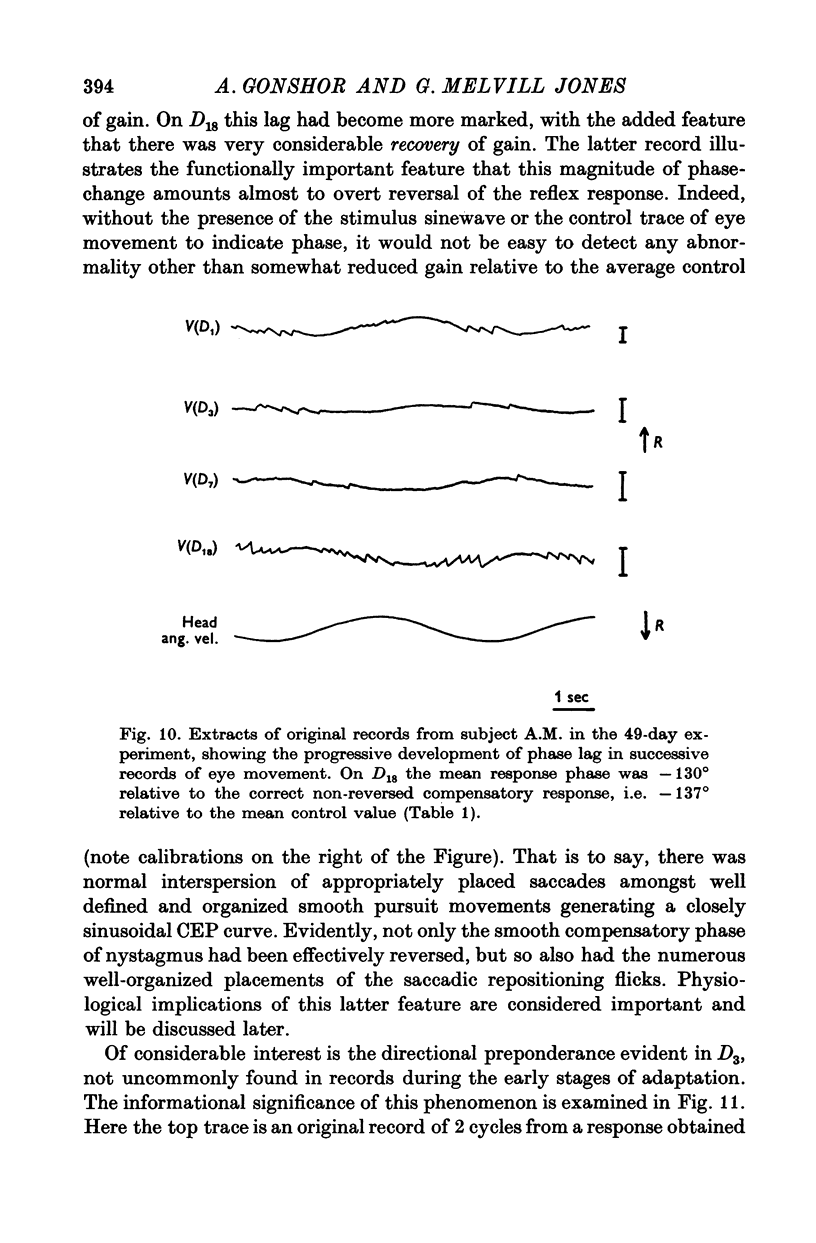

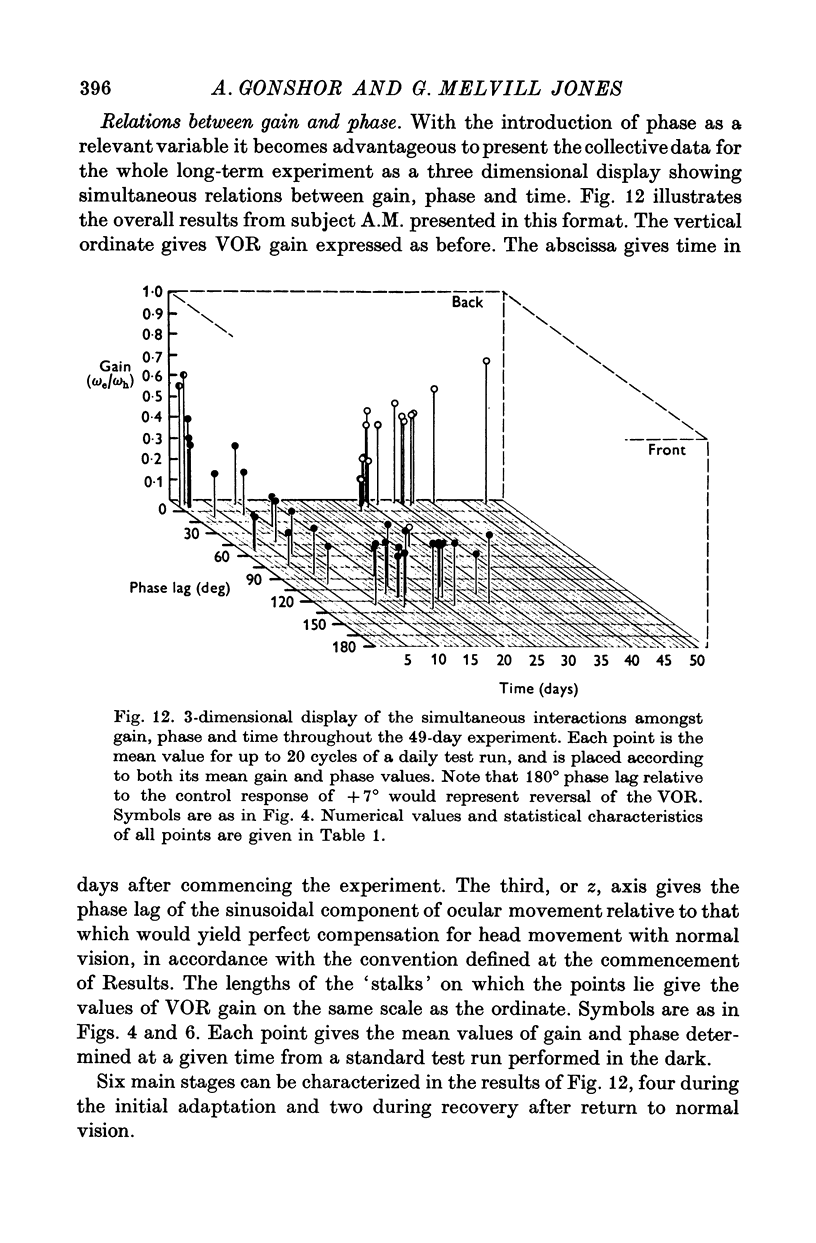

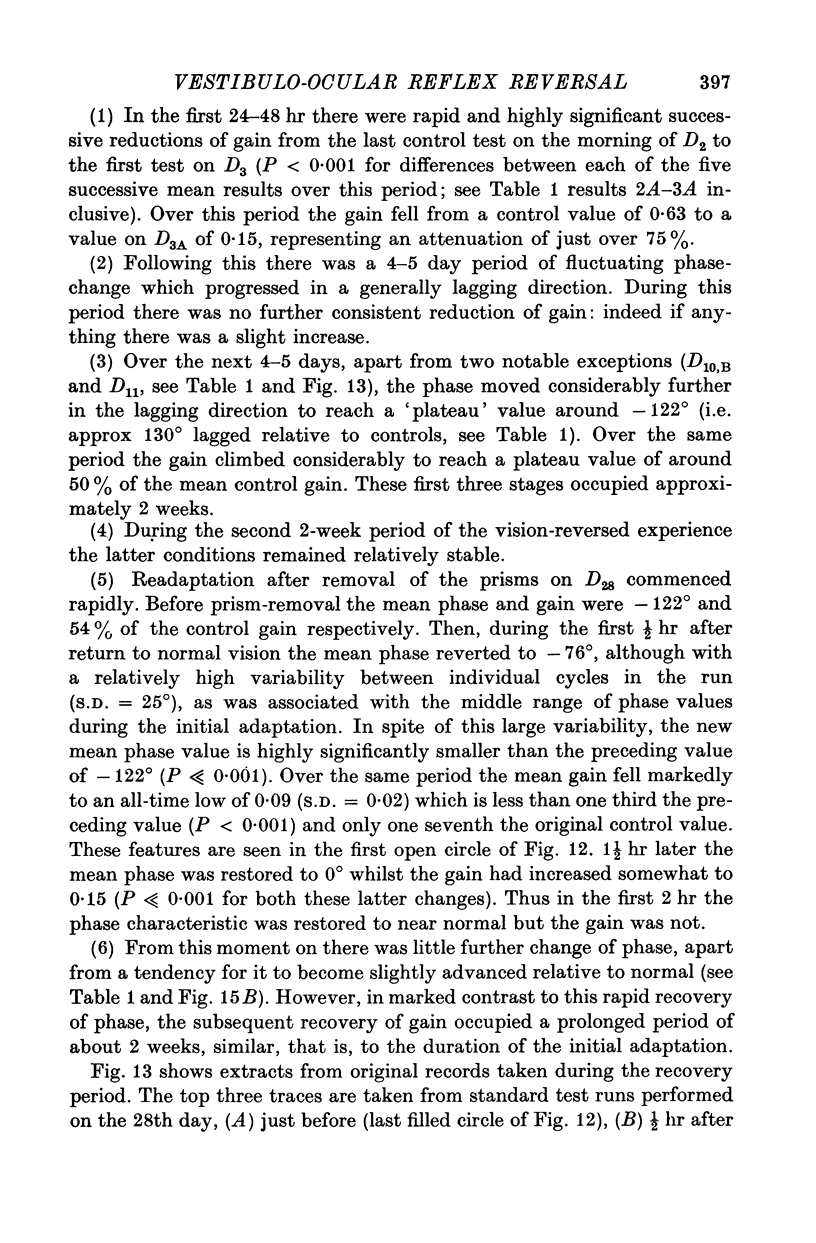

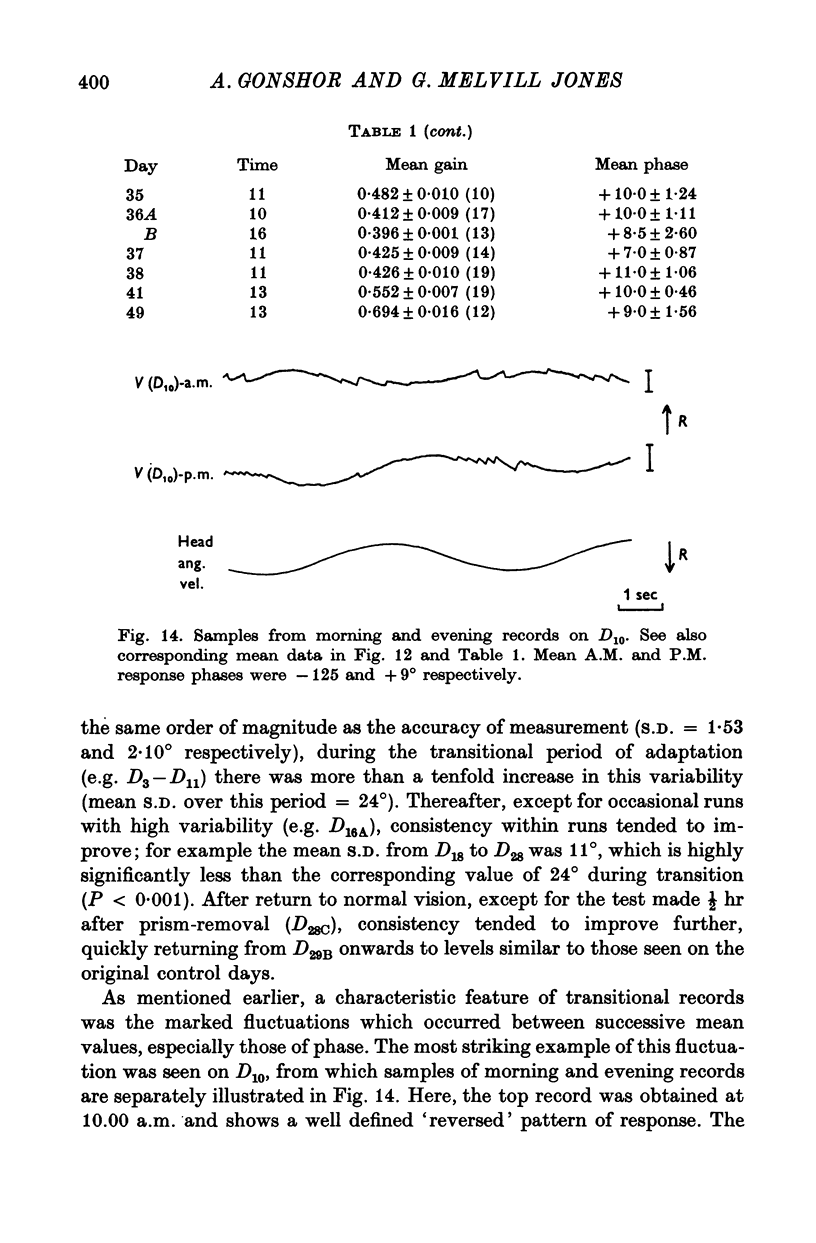

5. In the 27-day experiment large changes of phase developed in the VOR during the second week of vision-reversal. These changes generally progressed in a lagging sense, to reach 130° phase lag relative to normal by the beginning of the third week. Accompanying this was a considerable restoration of gain from 25 to 50% the normal value. These adapted conditions, which approximate functional reversal of the reflex, were then maintained steady, even overnight, until return to normal vision on the 28th day.

6. Thereafter, whereas VOR phase returned to near-normal in 2 hr, restoration of gain occupied a further 2-3 weeks.

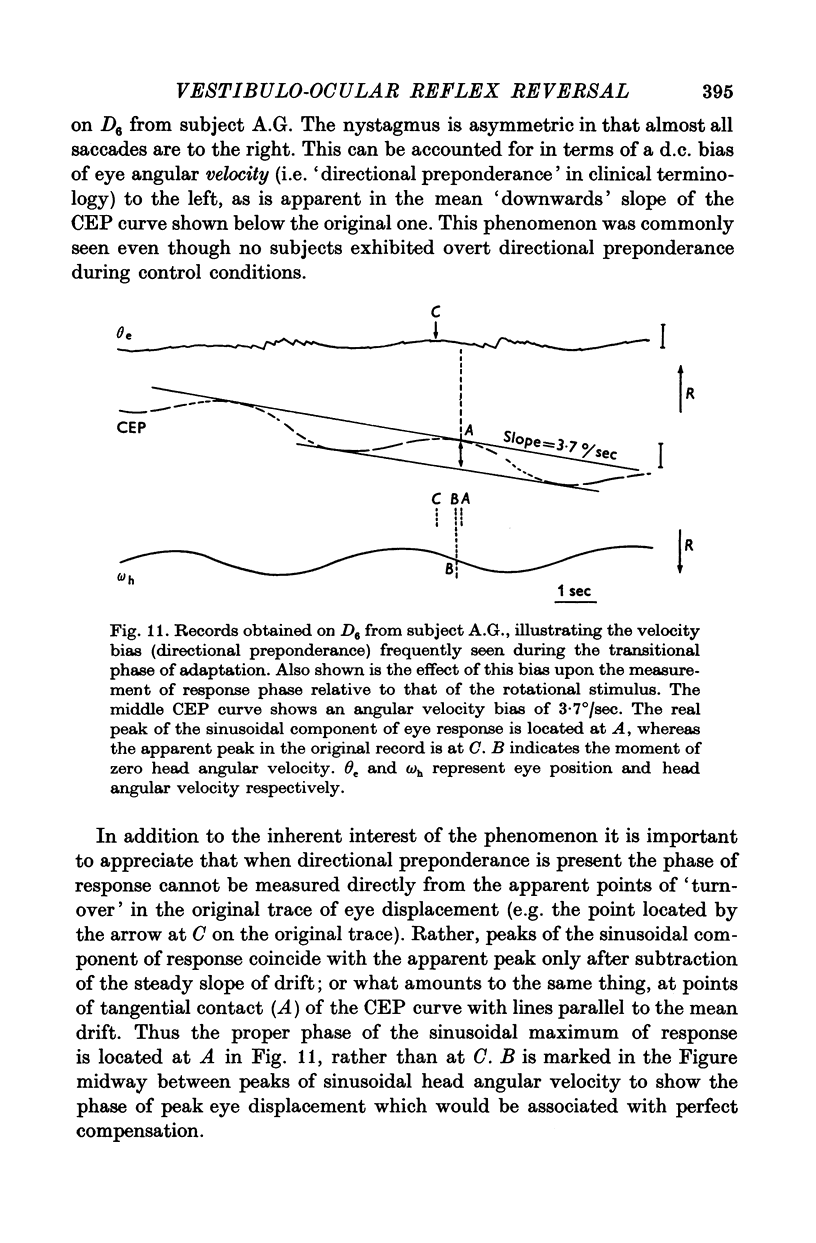

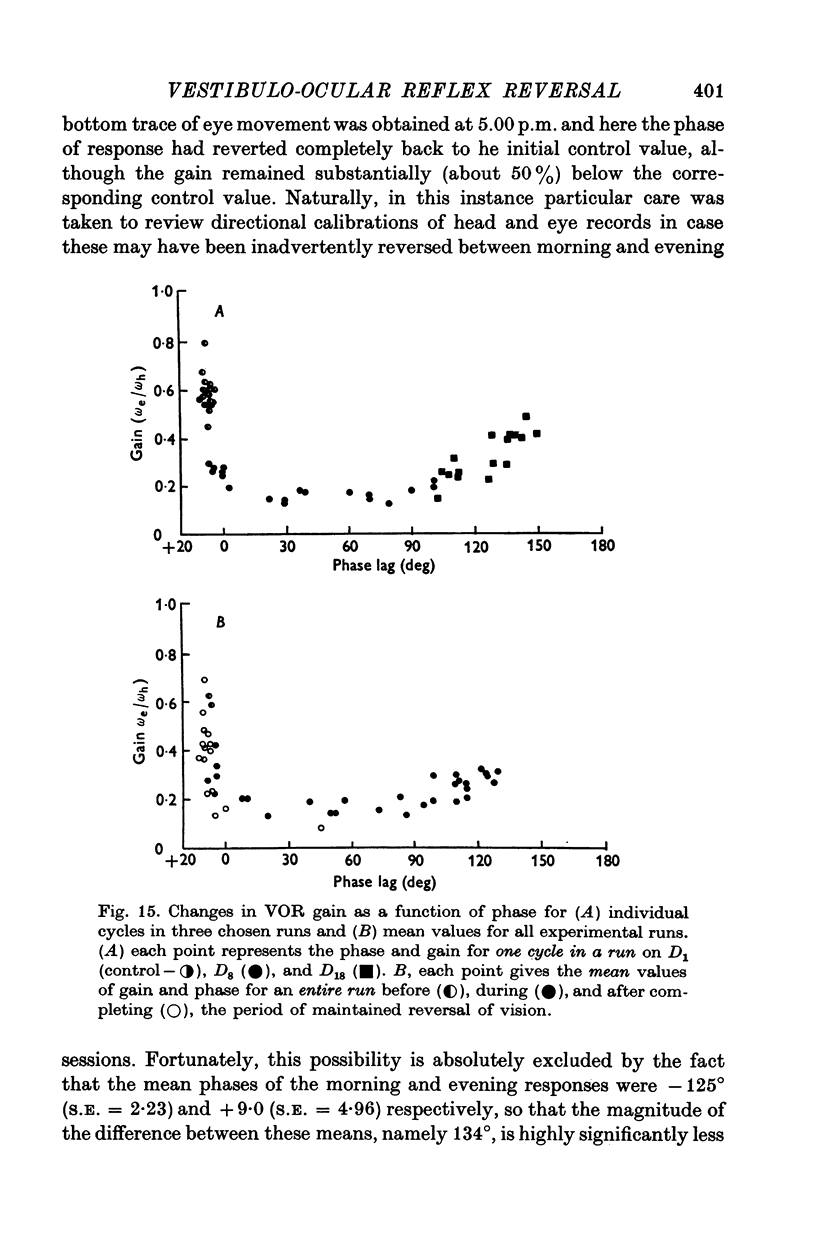

7. There was a highly systematic relation between instantaneous gain and phase, even during periods of widely fluctuating change associated with transition from one steady state to another. During such transition there was a tendency for directional preponderance to occur in the VOR.

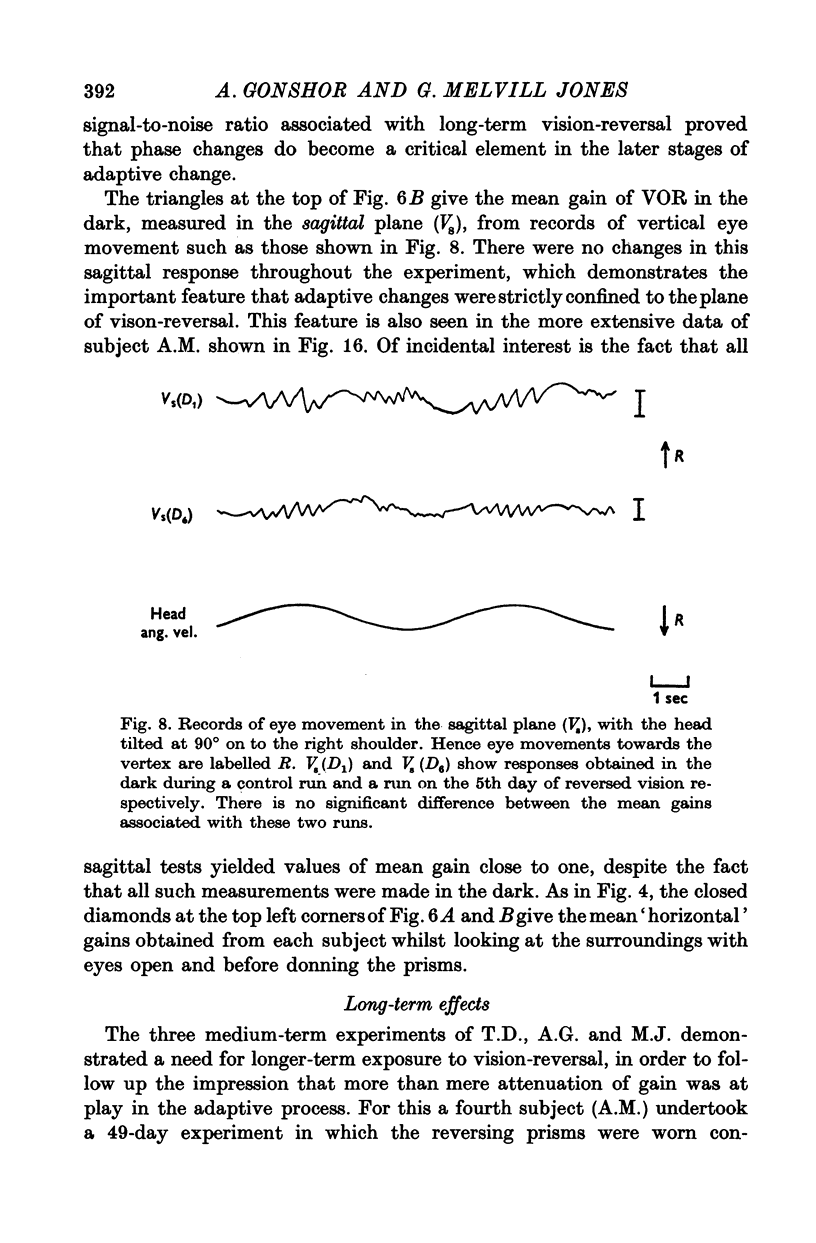

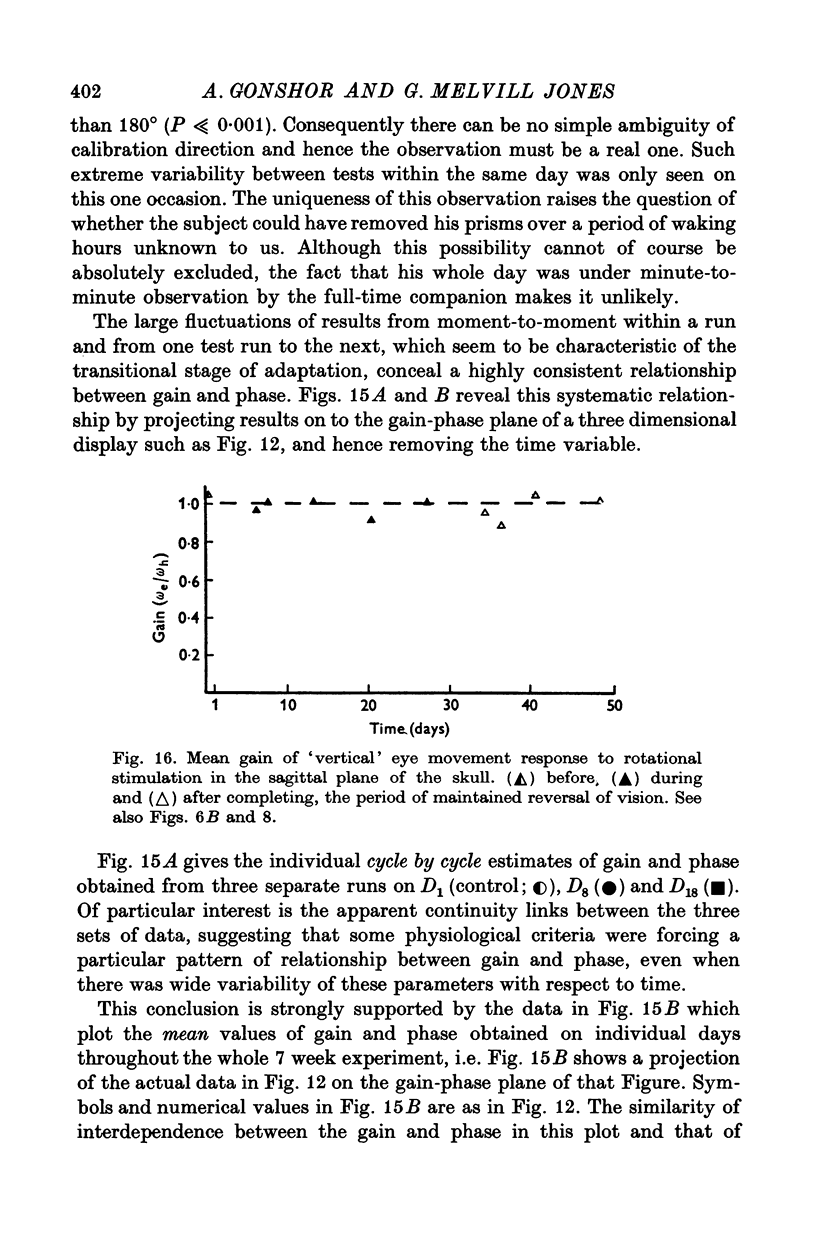

8. All the observed changes were highly specific to the plane of vision-reversal, no VOR changes being observed in the sagittal plane.

9. VOR changes were adaptive, in the sense that they were always goal-directed towards the requirements of retinal image stabilization during head movement. They were plastic to the extent that there was extensive and retained remodelling of the reflex towards this goal.

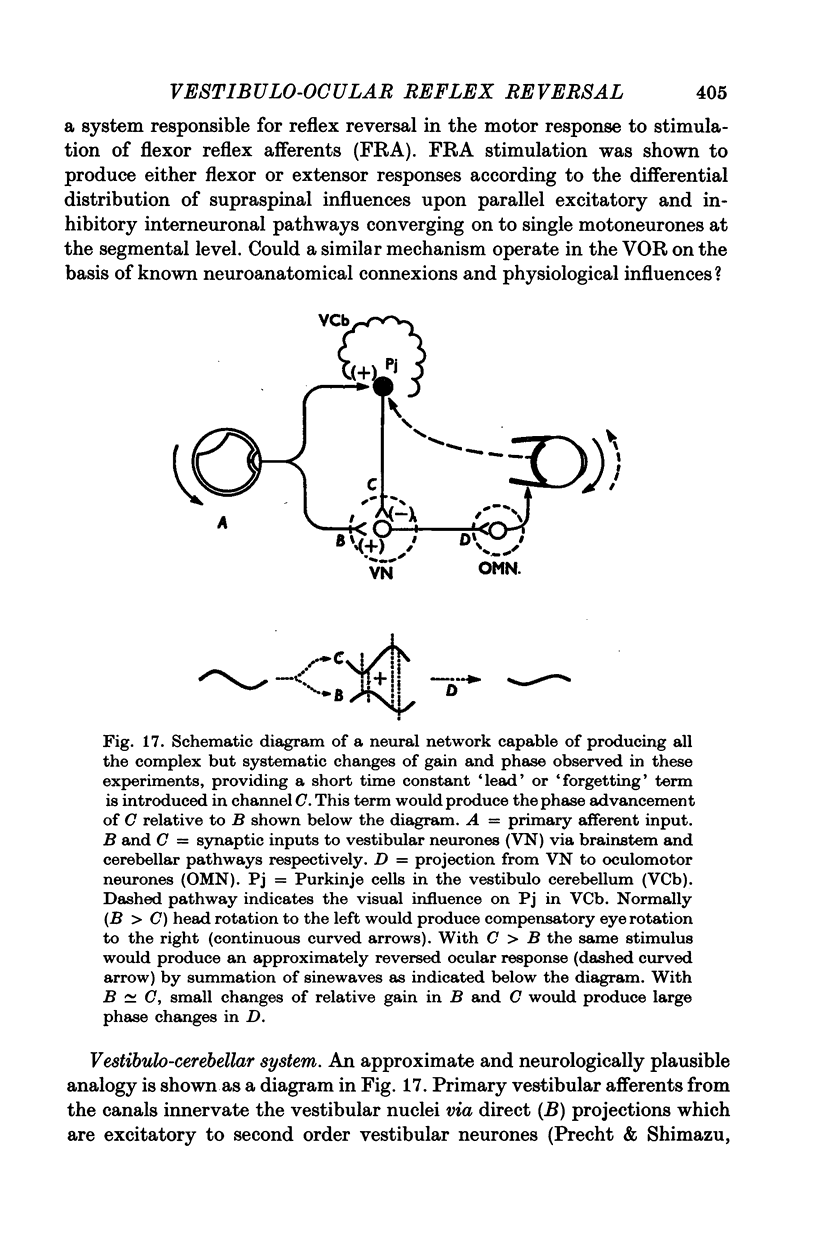

10. It is inferred that all the observed changes in gain and phase are compatible with a simple neural network employing known vestibulo-ocular projections via brainstem and cerebellar pathways, providing that the reversed visual tracking task can produce plastic modulation of efficacy in the cerebellar pathway and that this pathway exhibits a dynamic characteristic producing moderate phase lead in a sinusoidal signal at 1/6 Hz.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Angaut P., Brodal A. The projection of the "vestibulocerebellum" onto the vestibular nuclei in the cat. Arch Ital Biol. 1967 Nov;105(4):441–479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARRY W., JONES G. M. INFLUENCE OF EYE LID MOVEMENT UPON ELECTRO-OCULOGRAPHIC RECORDING OF VERTICAL EYE MOVEMENTS. Aerosp Med. 1965 Sep;36:855–858. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRODAL A., HOIVIK B. SITE AND MODE OF TERMINATION OF PRIMARY VESTIBULOCEREBELLAR FIBRES IN THE CAT. AN EXPERIMENTAL STUDY WITH SILVER IMPREGNATION METHODS. Arch Ital Biol. 1964 Jan 8;102:1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baarsma E., Collewijn H. Vestibulo-ocular and optokinetic reactions to rotation and their interaction in the rabbit. J Physiol. 1974 May;238(3):603–625. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1974.sp010546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker R., Precht W., Llinás R. Cerebellar modulatory action on the vestibulo-trochlear pathway in the cat. Exp Brain Res. 1972;15(4):364–385. doi: 10.1007/BF00234124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COLLINS W. E., CRAMPTON G. H., POSNER J. B. Effects of mental activity on vestibular nystagmus and the electroencephalogram. Nature. 1961 Apr 8;190:194–195. doi: 10.1038/190194b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COLLINS W. E., GUEDRY F. E., Jr Arousal effects and nystagmus during prolonged constant angular acceleration. Acta Otolaryngol. 1962 Mar-Apr;54:349–362. doi: 10.3109/00016486209126954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter M. B., Stein B. M., Peter P. Primary vestibulocerebellar fibers in the monkey: distribution of fibers arising from distinctive cell groups of the vestibular ganglia. Am J Anat. 1972 Oct;135(2):221–249. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001350209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies P., Jones G. M. An adaptive neural model compatible with plastic changes induced in the human vestibulo-ocular reflex by prolonged optical reversal of vision. Brain Res. 1976 Feb 27;103(3):546–550. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(76)90453-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dichgans J., Brandt T. Visual-vestibular interaction and motion perception. Bibl Ophthalmol. 1972;82:327–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez C., Goldberg J. M. Physiology of peripheral neurons innervating semicircular canals of the squirrel monkey. II. Response to sinusoidal stimulation and dynamics of peripheral vestibular system. J Neurophysiol. 1971 Jul;34(4):661–675. doi: 10.1152/jn.1971.34.4.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghelarducci B., Ito M., Yagi N. Impulse discharges from flocculus Purkinje cells of alert rabbits during visual stimulation combined with horizontal head rotation. Brain Res. 1975 Apr 4;87(1):66–72. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(75)90780-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg J. M., Fernandez C. Physiology of peripheral neurons innervating semicircular canals of the squirrel monkey. I. Resting discharge and response to constant angular accelerations. J Neurophysiol. 1971 Jul;34(4):635–660. doi: 10.1152/jn.1971.34.4.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonshor A., Jones G. M. Short-term adaptive changes in the human vestibulo-ocular reflex arc. J Physiol. 1976 Apr;256(2):361–379. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1976.sp011329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonshor A., Malcolm R. Effect of changes in illumination level on electro-oculography (EOG). Aerosp Med. 1971 Feb;42(2):138–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOLMQVIST B., LUNDBERG A. Differential supraspinal control of synaptic actions evoked by volleys in the flexion reflex afferents in alpha motoneurones. Acta Physiol Scand Suppl. 1961;186:1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henn V., Young L. R., Finley C. Vestibular nucleus units in alert monkeys are also influenced by moving visual fields. Brain Res. 1974 May 10;71(1):144–149. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(74)90198-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Highstein S. M. The organization of the vestibulo-oculomotor and trochlear reflex pathways in the rabbit. Exp Brain Res. 1973;17(3):285–300. doi: 10.1007/BF00234667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito M. Neural design of the cerebellar motor control system. Brain Res. 1972 May 12;40(1):81–84. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(72)90110-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito M. Neurophysiological aspects of the cerebellar motor control system. Int J Neurol. 1970;7(2):162–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito M., Nisimaru N., Yamamoto M. Specific neural connections for the cerebellar control of vestibulo-ocular reflexes. Brain Res. 1973 Sep 28;60(1):238–243. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(73)90863-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito M., Shiida T., Yagi N., Yamamoto M. Visual influence on rabbit horizontal vestibulo-ocular reflex presumably effected via the cerebellar flocculus. Brain Res. 1974 Jan 4;65(1):170–174. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(74)90344-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones G. M., Davies P. Adaptation of cat vestibulo-ocular reflex to 200 days of optically reversed vision. Brain Res. 1976 Feb 27;103(3):551–554. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(76)90454-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones G. M., Milsum J. H. Characteristics of neural transmission from the semicircular canal to the vestibular nuclei of cats. J Physiol. 1970 Aug;209(2):295–316. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1970.sp009166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones G. M., Milsum J. H. Frequency-response analysis of central vestibular unit activity resulting from rotational stimulation of the semicircular canals. J Physiol. 1971 Dec;219(1):191–215. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1971.sp009657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones G. M. Transfer function of labyrinthine volleys through the vestibular nuclei. Prog Brain Res. 1972;37:139–156. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)63899-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOHLER I. Experiments with goggles. Sci Am. 1962 May;206:62–72. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0562-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KRIS C. Corneo-fundal potential variations during light and dark adaptation. Nature. 1958 Oct 11;182(4641):1027–1028. doi: 10.1038/1821027a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisberger S. G., Fuchs A. F. Response of flocculus Purkinje cells to adequate vestibular stimulation in the alert monkey: fixation vs. compensatory eye movements. Brain Res. 1974 Apr 5;69(2):347–353. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(74)90013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maekawa K., Simpson J. I. Climbing fiber responses evoked in vestibulocerebellum of rabbit from visual system. J Neurophysiol. 1973 Jul;36(4):649–666. doi: 10.1152/jn.1973.36.4.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malcolm R., Jones G. M. A quantitative study of vestibular adaptation in humans. Acta Otolaryngol. 1970 Aug;70(2):126–135. doi: 10.3109/00016487009181867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles F. A., Fuller J. H. Adaptive plasticity in the vestibulo-ocular responses of the rhesus monkey. Brain Res. 1974 Nov 22;80(3):512–516. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(74)91035-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Precht W., Shimazu H., Markham C. H. A mechanism of central compensation of vestibular function following hemilabyrinthectomy. J Neurophysiol. 1966 Nov;29(6):996–1010. doi: 10.1152/jn.1966.29.6.996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROBINSON D. A. THE MECHANICS OF HUMAN SACCADIC EYE MOVEMENT. J Physiol. 1964 Nov;174:245–264. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1964.sp007485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SZENTAGOTHAI J. The elementary vestibulo-ocular reflex arc. J Neurophysiol. 1950 Nov;13(6):395–407. doi: 10.1152/jn.1950.13.6.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson J. I., Alley K. E. Visual climbing fiber input to rabbit vestibulo-cerebellum: a source of direction-specific information. Brain Res. 1974 Dec 27;82(2):302–308. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(74)90610-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skavenski A. A., Robinson D. A. Role of abducens neurons in vestibuloocular reflex. J Neurophysiol. 1973 Jul;36(4):724–738. doi: 10.1152/jn.1973.36.4.724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takemori S., Cohen B. Loss of visual suppression of vestibular nystagmus after flocculus lesions. Brain Res. 1974 Jun 7;72(2):213–224. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(74)90860-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]