Abstract

The mce1A gene of Mycobacterium tuberculosis was initially identified by its ability to promote uptake of Escherichia coli into HeLa cells. It was subsequently shown that this activity was confined to a 58-amino-acid region of the protein. A 72-amino-acid fragment (InvX) incorporating this active peptide was expressed in E. coli as a fusion to the AIDA (adhesin involved in diffuse adherence) autotransporter translocator, and its stable expression on the surface of the bacterium was demonstrated. Recombinant E. coli expressing InvX-AIDA showed extensive association with HeLa cells, and InvX was shown to be sufficient for internalization. Uptake was found to be both microtubule and microfilament dependent and required the Rho family of GTPases. Thus, the E. coli AIDA system facilitated both the qualitative and quantitative analysis of the functional domain of a heterologous protein.

It has been estimated that one-third of the world's population is infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the etiologic agent of tuberculosis, which kills approximately two million people each year (14). In vivo M. tuberculosis is thought to primarily invade and replicate within alveolar macrophages, although a recent study suggests that it may persist in other types of human lung cells (21). Additionally, it has been shown to enter a number of different cell types in vitro (6, 37). M. tuberculosis is known to bind many different macrophage receptors. For example, bacilli opsonized with C3b and C3bi bind complement receptors CR1, CR3, and CR4 (35, 36) and also bind CR3 nonopsonically via envelope polysaccharides (11). In addition, the terminal mannosyl residues of lipoarabinomannan bind mannose receptors (34) and opsonization with surfactant protein A enhances uptake (12). In spite of this array of receptors, very little is known about the M. tuberculosis ligands involved in invasion or the macrophage signaling events involved in phagocytosis.

A putative M. tuberculosis virulence gene, mce1A (mycobacterium cell entry), was originally identified because its expression in Escherichia coli enabled this noninvasive bacterium to enter nonphagocytic mammalian cells (1). It was subsequently shown that latex microspheres coated with recombinant Mce1A were also capable of entering HeLa cells (9). Comparison of the ability of truncated forms of recombinant Mce1A to induce the uptake of microspheres confined this activity to a 58-amino-acid domain located between positions 106 and 163 of the protein. Disruption of the mce1A gene homologue in Mycobacterium bovis BCG reduced its ability to invade HeLa cells, providing evidence that, in its native host, Mce1A plays a role in the invasion of nonphagocytic cells (18).

Sequencing of the M. tuberculosis genome revealed that mce1A (Rv0169) was part of an operon that encoded eight putative membrane-associated proteins (10, 39). The first two genes of the operon (Rv0167-68) encode proteins with six putative transmembrane regions and are predicted to be integral membrane proteins. The following six encoded proteins (Rv0169-74) have putative signal sequences, indicating that they are presented on the surface of the bacillus. Indeed, electron microscopic analysis of immunogold-labeled M. tuberculosis has demonstrated the surface exposure of Mce1A, which is consistent with a role in interaction with the host cell (9). The mce operon is present four times in the M. tuberculosis chromosome (10).

Autotransporters comprise a growing family of gram-negative proteins that are also referred to as type V secretion systems (19, 30). Remarkably, in these secretion systems, all the information required for export through the outer membrane is contained within a single self-translocating polypeptide. The typical autotransporter consists of an amino-terminal signal peptide, a “passenger” domain, a linker region, and a core translocator at the carboxy terminus. The signal peptide directs translocation across the inner membrane, most probably by a sec-dependent mechanism. Subsequently, the core translocator, which consists of 14 amphipathic β-strands, inserts into the outer membrane in a characteristic β-barrel structure. The amino-terminal passenger is then extruded through a central pore and may undergo further proteolytic processing at the cell surface (20, 32, 38).

Several studies have reported that plasmids expressing recombinant autotransporter proteins are able to present heterologous passenger proteins at the bacterial cell surface. For example, the immunoglobulin A1 protease of Neisseria gonorrhoeae was shown to efficiently express the cholera toxin B subunit on the surfaces of E. coli and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium cells (24). The E. coli autotransporter, known as AIDA (adhesin involved in diffuse adherence) (3, 4, 5, 27), has been used to present functional T-cell epitopes as well as enzymatically active β-lactamase on the surface of the native host (26, 28).

This report describes the construction of a fusion protein consisting of the AIDA autotransporter translocator and a 72-amino-acid region of Mce1A, designated InvX, which contains the putative active domain with short flanking regions (9). It is shown that expression of the InvX-AIDA fusion in E. coli results in the stable presentation of functional InvX on the bacterial surface. The AIDA system provided a convenient way to analyze and quantify InvX-directed uptake into HeLa cells, demonstrating its utility in the characterization of functional domains from heterologous proteins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and cell lines.

E. coli strain UT4400, an ompT-negative derivative of UT2300, was the host strain used in all experiments (15). E. coli was grown in Luria-Bertani medium supplemented with 100 μg of ampicillin/ml or 50 μg of kanamycin/ml to maintain plasmids. The human epithelial cell line, HeLa (ATCC CCL-2), was maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10 mM sodium pyruvate, 10% fetal bovine serum, and 10 μg of penicillin-streptomycin/ml.

Construction of vectors.

Plasmid pMK90 is an ampicillin-resistant pBR322 derivative that expresses a recombinant AIDA protein under the control of its own promoter (3). The AIDA coding sequence has been altered to remove the native passenger; it consists of a 49-amino-acid signal peptide, a 78-amino-acid linker region incorporating a multiple cloning site, and the entire 440-amino-acid β-barrel core. A 240-bp DNA fragment encoding InvX (M. tuberculosis H37Rv genome positions 198847 to 199063) was amplified by PCR from a plasmid containing mce1A and cloned into pMK90, generating pMK100. The correct insert was confirmed by sequencing. The amino acid sequence of InvX is VNADIKATTVFGGKYVSLTTPKNPTKRRITPKDVIDVRSVTTEINTLFQTLTSIAEKVDPVKLNLTLSAAAE. Plasmid pMS2kan expresses a kanamycin resistance marker.

Invasion and attachment assays.

Gentamicin protection assays were performed according to the method of Elsinghorst (16). HeLa cells were seeded at 105 cells per well onto coverslips or directly into 24-well plates and cultured for 24 h until confluent. Cell culture medium was modified to contain 1% mannose and no antibiotics. Recombinant E. coli cells were added to the monolayer at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10:1 and incubated at 37°C for 3 h. To enumerate associated (adherent and intracellular) bacteria, we washed the monolayer three times with phosphate-buffered saline and subsequently lysed the cells in 0.1% Triton X-100 (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.). Alternatively, washing was followed by incubation with medium containing 100 μg of gentamicin (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.)/ml for 1 h to kill extracellular bacteria and permit the enumeration of intracellular bacteria. The monolayer was again washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline and lysed. Serial dilutions of released bacteria were plated for counting. Associated and invaded bacteria are presented as a percentage of the inoculum; results shown are the mean values for an experiment performed in triplicate ± standard deviation. Each experiment was executed three times using independent cultures, with similar results.

In some experiments, HeLa cells were pretreated with various concentrations of inhibitory agents; inhibitors were kept in the medium throughout the experiment. Cytochalasin D (Sigma Chemical Co.) was added at a concentration of 0.01 to 1 μg/ml, and the cells were incubated at 37°C for 30 min prior to infection. Nocodazole (Sigma Chemical Co.) was used at a concentration of 0.5 to 10 μg/ml, with preincubation for 1 h at 4°C followed by warming to 37°C for 30 min. Clostridium difficile toxin B (Sigma Chemical Co.) was added at a concentration of 10 ng/ml, and incubation was continued for 20 h at 37°C before the addition of bacteria. The effect of inhibitors on HeLa cell viability was assessed by using the trypan blue exclusion assay (2), and the effect on the growth of the recombinant E. coli strains in supplemented Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium was determined.

After infection, HeLa cells seeded onto coverslips were fixed in ice-cold methanol at 4°C for 10 min and stained with SureStain Wright-Giemsa (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, Pa.) at room temperature for 10 min. Coverslips were washed three times in water and mounted onto microscope slides with CytoSeal (Stephens Scientific, Riverdale, N.J.). Slides were viewed with a Nikon Optiphot-2 microscope and photographed with a Sony DKC-5000 digital camera.

Electron microscopy.

Infected cells were prepared for examination by transmission electron microscopy as previously described (9). Briefly, cells were fixed in 2% glutaraldehyde and stained with osmium tetroxide solution before dehydration through graded ethanol solutions. Cells were embedded in Spur's low-viscosity embedding medium, and ultrathin sections were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Samples were examined with a JEOL model 100CX-II transmission electron microscope.

Immunofluorescence microscopy.

E. coli cells were fixed onto microscope slides with 0.4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature, and nonspecific binding was blocked by incubation in 1% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin for 30 min. Slides were incubated for 1 h with a 1:40 dilution of a mouse antibody raised against Mce1A (HI5), washed, and incubated with a 1:100 dilution of fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled anti-mouse antibody (Sigma Chemical Co.) for 1 h. After extensive washing, the coverslips were mounted with SlowFade Light antifade reagent (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.). Slides were viewed on a Nikon Eclipse TE300 inverted microscope with an epifluorescence attachment, and photomicrography was performed with Nikon U-III equipment.

Statistical analyses.

A two-tailed Student's t test, adjusted for unequal variance, was used to compare the mean CFUs recovered after the gentamicin protection assays.

RESULTS

InvX is presented on the surface of E. coli cells by the AIDA autotransporter translocator.

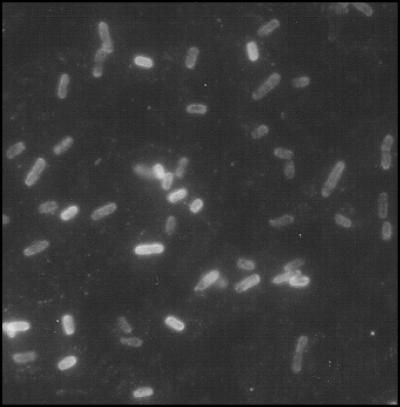

The recombinant AIDA autotransporter translocator was expressed from the plasmid pMK90. A 72-amino-acid region of Mce1A (positions 106 to 177) termed InvX, which contains the 58-amino-acid putative active domain with short flanking regions (9), was cloned into the AIDA vector, resulting in the construct pMK100. An ompT-negative E. coli strain, UT4400, was used to express AIDA fusions, as OmpT is known to sometimes cleave surface-exposed passengers (25, 38). Immunoblotting with polyclonal antibodies raised against the core AIDA translocator or Mce1A indicated that the expected fusion protein was expressed in E. coli UT4400(pMK100) cells (data not shown). Surface expression of InvX was ascertained by loss of immunoreactivity with the anti-Mce1A antibody after trypsin digestion of whole cells (data not shown) and verified by indirect immunofluorescence of whole cells (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Indirect immunofluorescent staining of InvX-expressing E. coli. E. coli cells were surface labeled with a mouse polyclonal antibody raised against Mce1A and a fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody. Fluorescence microscopy showed that E. coli expressing the InvX-AIDA fusion protein bound anti-Mce1A antibody but not mouse preimmune serum (not shown). Neither antibody nor preimmune serum bound to the surface of E. coli cells expressing AIDA alone (not shown). Magnification, ×1,000.

InvX can mediate adhesion to HeLa cells and is sufficient for internalization.

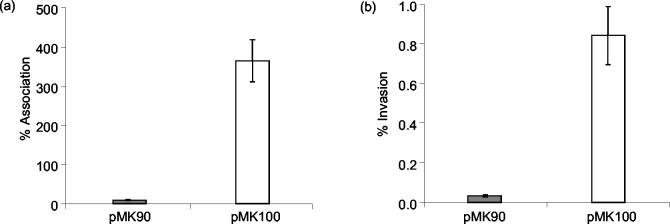

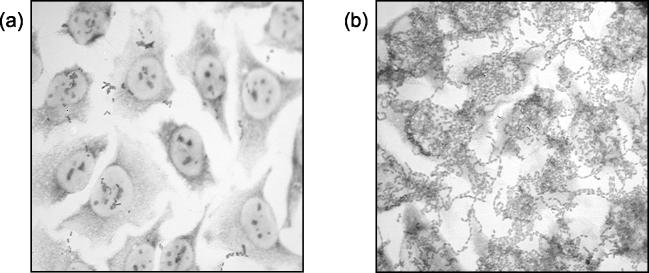

InvX-expressing E. coli cells showed a 40-fold greater association with HeLa cells than the control strain (P < 0.008) (Fig. 2a). The recombinant E. coli strains had a doubling time of approximately 1 h in tissue culture medium; hence, the level of association after 3 h was calculated at almost 400% that of the inoculum. Adherence was also assessed microscopically by Giemsa staining. E. coli(pMK100) showed extensive association with HeLa cells, forming dense lacy networks on the monolayer, whereas the control strain showed little adherence (Fig. 3).

FIG. 2.

InvX-mediated association and invasion of HeLa cells. HeLa cells were infected with E. coli harboring the InvX-expressing plasmid pMK100 or the control plasmid pMK90 at an MOI of 10:1 for 3 h. Bars represent the mean number of associated (a) or intracellular (b) bacteria as a percentage of the inoculum in a representative experiment performed in triplicate. Standard deviations are indicated by error bars.

FIG. 3.

InvX-mediated attachment to HeLa cells. HeLa cells were infected with the control strain (a) or E. coli cells expressing InvX (b) at an MOI of 10:1. After 3 h, the monolayer was washed thoroughly and stained with Giemsa to visualize bacteria associated with the HeLa cells. Magnification, ×400.

We assessed the ability of InvX to mediate uptake of the host E. coli cells by using gentamicin protection assays (16). E. coli(pMK100) cells showed invasion levels at the 3-h time point that were 25-fold higher than those for the control cells, with 0.8% of the inoculum protected (P < 0.011) (Fig. 2b). Incubation of the infected monolayer for up to 3 h in the presence of gentamicin did not result in increased bacterial recovery, indicating that the recombinant E. coli did not replicate inside HeLa cells during this time period.

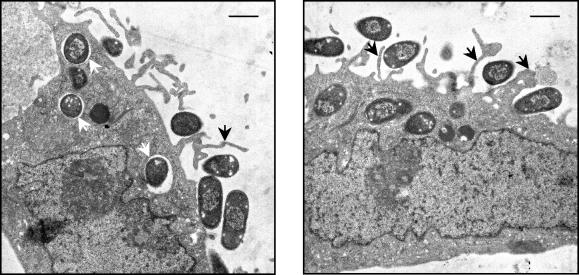

In order to confirm that the gentamicin-protected bacteria truly resided intracellularly, we additionally examined infected cells by electron microscopy (Fig. 4). After 3 h of incubation, E. coli(pMK100) cells showed extensive adherence to the HeLa cell surface and appeared to elicit filopodia-like membrane protrusions. Intracellular bacteria were seen in membrane-bound compartments, definitively demonstrating that they had been internalized. Control E. coli(pMK90) was rarely seen associated with HeLa cells and was never seen inside cells.

FIG. 4.

Electron micrographs of InvX-expressing E. coli invading HeLa cells. E. coli cells expressing InvX were incubated with HeLa cells for 3 h at an MOI of 10:1 before they were processed for transmission electron microscopy. The micrographs show that E. coli cells attached to the HeLa cell surface elicit membrane protrusions (black arrows) and that intracellular bacilli are located within membrane-bound compartments (white arrows). Scale bars are 1 μm.

Disruption of the actin cytoskeleton inhibits invasion.

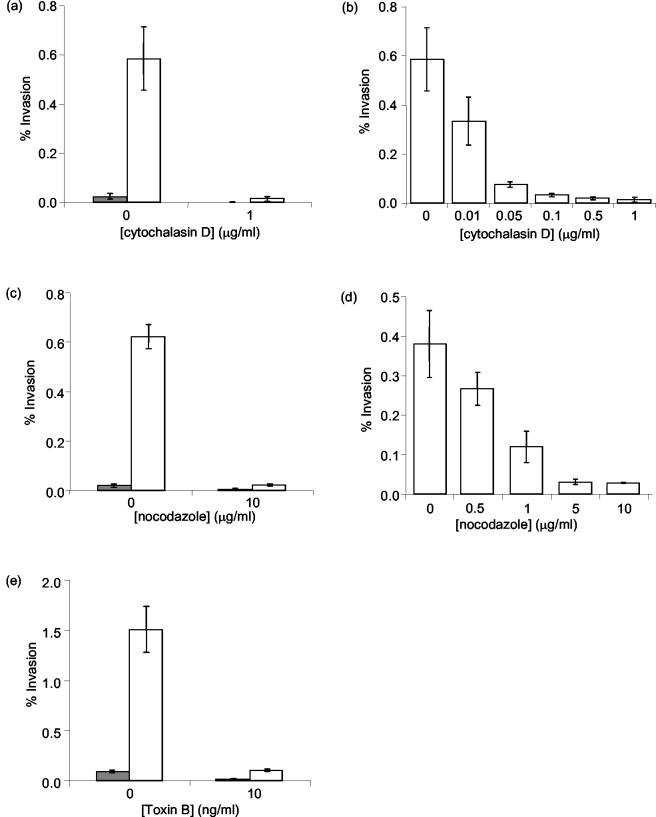

To determine whether actin microfilaments were required for InvX-mediated invasion, HeLa cells were pretreated with cytochalasin D, which specifically inhibits actin polymerization (33). Gentamicin protection assays showed that treatment of cells with 1 μg of cytochalasin D/ml reduced the invasion of E. coli(pMK100) to control levels (P < 0.016) and that the inhibition of invasion was dose dependent (Fig. 5a and b). HeLa cell viability and bacterial viability were not affected. Bacterial adhesion was also not affected by cytochalasin D treatment, indicating that the role of actin microfilaments was in bacterial uptake.

FIG. 5.

Effect of cytoskeletal inhibitors on InvX-mediated invasion. Gentamicin protection assays were used to determine the effects of cytochalasin D (a and b), nocodazole (c and d), or toxin B (e) on the level of invasion of E. coli(pMK90) (filled bars) and E. coli(pMK100) (open bars) into HeLa cells. Bars represent the mean number of internalized bacilli from a representative experiment performed in triplicate. Standard deviations are indicated by error bars.

Inhibition of Rho-family GTPases prevents invasion.

C. difficile toxin B inactivates Rho family GTPases by monoglucosylation with a dominant negative effect (23). Toxin B treatment resulted in the rounding up of HeLa cells but did not affect their viability. This pretreatment completely inhibited E. coli(pMK100) entry (P < 0.003) (Fig. 5e) but did not affect bacterial adhesion or viability. Thus, it appears that Rho family GTPases are involved in the invasion mechanism of InvX-expressing E. coli. It was not possible to determine the dose dependency of inhibition due to the narrow concentration range at which toxin B was active without being toxic.

Microtubule disruption inhibits invasion.

Pretreatment of HeLa cells with 10 μg of nocodazole/ml, which specifically depolymerizes microtubules, resulted in rounding of the cells without affecting viability. Nocodazole treatment clearly inhibited the uptake of E. coli(pMK100), reducing it to the level of the control, E. coli(pMK90) (P < 0.009) (Fig. 5c). It was shown that the inhibition of invasion was dose dependent (Fig. 5d) but that bacterial viability and association were not affected. Hence, E. coli expressing InvX requires an intact microtubule network for entry but not for adhesion to HeLa cells.

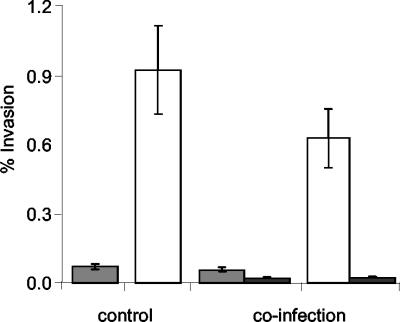

Invasion does not affect the uptake of bystander bacteria.

We wished to determine whether internalization of InvX-expressing E. coli resulted in the nonspecific uptake of proximal bacilli. Thus, HeLa cells were simultaneously infected with either E. coli(pMK100) or E. coli(pMK90) cells, which carry an ampicillin resistance marker, and a second noninvasive recombinant E. coli strain expressing kanamycin resistance. Recovered intracellular bacteria were plated on ampicillin and kanamycin to determine whether nonspecific uptake occurred. No significant uptake of the noninvasive kanamycin-resistant strain was observed when coinfected with either E. coli(pMK100) or E. coli(pMK90) (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Effect of InvX-mediated invasion on bystander bacteria. Control HeLa cells were infected with either E. coli(pMK90) (shaded bars) or the InvX-expressing E. coli(pMK100) (white bars). In addition, HeLa cells were coinfected with the same number of noninvasive bystander E. coli(pMS2) cells (black bars) in the presence of either E. coli(pMK90) or E. coli(pMK100). The number of internalized bacilli was determined in triplicate by using a gentamicin protection assay, and the mean result was expressed as a percentage of the inoculum. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

DISCUSSION

Mce1A of M. tuberculosis has previously been shown to facilitate the uptake of E. coli into HeLa cells (1). This activity appears to reside in the amino acid region between positions 106 and 163 of Mce1A, the deletion of which rendered the truncated protein inactive in HeLa cell invasion assays using latex microspheres (9). In previous studies, in which E. coli was shown to be taken up by HeLa cells (1), the mechanism by which the recombinant protein gained access to the surface of the bacilli to induce cell uptake was not investigated. It is possible that E. coli became coated with recombinant protein released by low-level lysis in the growing culture, which is consistent with the reported adhesive properties of Mce1A (9). The role of the active domain in the cell uptake of latex microspheres could not be readily quantified, as light microscopy did not distinguish internalized versus surface-associated microspheres and electron microscopy is not a reliable quantitative technique. Thus, the ability of the AIDA autotransporter translocator to present Mce1A-derived peptide on the surface of E. coli cells was investigated as a system that would enable us to more reliably characterize and quantify the interaction of the putative active domain with mammalian cells.

In this study, the AIDA autotransporter translocator was shown to be capable of presenting InvX, a 72-amino-acid peptide encompassing the putative active domain of Mce1A, on the surface of E. coli cells. Surface localization was demonstrated by the binding of InvX-specific antibodies to whole cells by indirect immunofluorescence and confirmed by the loss of immunoreactivity after protease treatment. E. coli cells expressing InvX-AIDA on their surface were tested for their ability to adhere to and invade HeLa cells compared to a control recombinant E. coli strain expressing the AIDA translocator without any passenger domain. An adherence assay revealed that, after 3 h of incubation, dense networks of InvX-expressing bacteria were associated with the HeLa cell monolayer. Approximately 0.8% of the inoculum was protected from gentamicin, implying an intracellular location, and electron microscopic analysis of HeLa cells incubated with InvX-expressing E. coli definitively demonstrated the presence of internalized bacteria. Thus, InvX promotes the attachment of and is sufficient for the entry of noninvasive bacteria into HeLa cells. The ability of the AIDA autotransporter translocator to present functional peptides establishes its potential for use in the analysis of surface interactions between bacterial and mammalian cells.

Invasive bacterial pathogens frequently hijack host cell cytoskeletal components and subvert host-signaling pathways to promote their own uptake. Numerous pathogens are able to trigger the rearrangement of host cell actin, and a number of bacterial virulence factors target the Rho family of small GTPases, Rho, Rac, and Cdc42, which are key regulators of actin reorganization (17). The inhibition of InvX-induced uptake in the presence of cytochalasin D and C. difficile toxin B indicates that internalization is actin dependent and that Rho GTPases are involved in the signaling pathway of actin rearrangement. Microtubules are less often exploited by invasive bacteria than microfilaments, but there are a growing number of instances in which invasion has been shown to be microtubule dependent (31). Internalization of InvX-expressing E. coli was abolished by pretreatment with nocodazole, demonstrating that an intact microtubule network is needed for InvX-mediated invasion. It is interesting to note that M. tuberculosis invasion of cultured alveolar epithelial cells has also been shown to be both microfilament and microtubule dependent (6).

Strategies for the exploitation of the host cytoskeleton by bacterial pathogens during entry can be divided into two distinct categories, termed the zipper and trigger mechanisms (13). The zipper mechanism involves local cytoskeletal rearrangement and requires direct contact between bacterial ligands and cellular receptors, which sequentially encircle the organism, resulting in a tight apposition between the host cell membrane and the bacillus. The most well-studied examples of this receptor-mediated zipper-type mechanism of entry include the Yersinia pseudotuberculosis invasin and the Listeria monocytogenes internalins InlA and InlB (7, 8, 22, 29). In contrast, the trigger mechanism, exemplified by Salmonella and Shigella entry, requires a large number of proteins (17). This mechanism involves the induction of dramatic membrane ruffles, which trap the bacilli in spacious vacuoles, resulting in the passive entry of bacteria and particles in the vicinity. InvX-induced invasion did not affect the uptake of proximal bystander bacteria, suggesting that this mode of entry resembles the receptor-mediated zipper-type mechanism. The electron micrographs showing filopodia encircling the bacilli, which are subsequently enclosed in vacuoles with tightly fitting membranes, provide additional evidence in support of this mechanism. Consistent with these observations is the finding that solubilized recombinant Mce1A is able to competitively inhibit the uptake of Mce1A-coated microspheres (9). However, despite extensive investigation, the receptor for Mce1A and InvX remains elusive. The ability to express the active domain of Mce1A by the AIDA system may now facilitate its identification.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Electron Microscopy Lab and the Scientific Visualization Center at the University of California, Berkeley, for assistance in preparing the images.

This work was supported by NIH grant number AI53266.

N.C. and M.K. contributed equally to this work.

Editor: S. H. E. Kaufmann

REFERENCES

- 1.Arruda, S., G. Bomfim, R. Knights, T. Huima-Byron, and L. W. Riley. 1993. Cloning of an M. tuberculosis DNA fragment associated with entry and survival inside cells. Science 261:1454-1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl. 1992. Short protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley and Sons, New York, N.Y.

- 3.Benz, I., and M. A. Schmidt. 1989. Cloning and expression of an adhesin (AIDA-I) involved in diffuse adherence of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 57:1506-1511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benz, I., and M. A. Schmidt. 1992. AIDA-I, the adhesin involved in diffuse adherence of the diarrhoeagenic Escherichia coli strain 2787 (O126:H27), is synthesized via a precursor molecule. Mol. Microbiol. 6:1539-1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benz, I., and M. A. Schmidt. 1992. Isolation and serologic characterization of AIDA-I, the adhesin mediating the diffuse adherence phenotype of the diarrhea-associated Escherichia coli strain 2787 (O126:H27). Infect. Immun. 60:13-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bermudez, L. E., and J. Goodman. 1996. Mycobacterium tuberculosis invades and replicates within type II alveolar cells. Infect. Immun. 64:1400-1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braun, L., B. Ghebrehiwet, and P. Cossart. 2000. gC1q-R/p32, a C1q-binding protein, is a receptor for the InlB invasion protein of Listeria monocytogenes. EMBO J. 19:1458-1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braun, L., H. Ohayon, and P. Cossart. 1998. The InIB protein of Listeria monocytogenes is sufficient to promote entry into mammalian cells. Mol. Microbiol. 27:1077-1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chitale, S., S. Ehrt, I. Kawamura, T. Fujimura, N. Shimono, N. Anand, S. Lu, L. Cohen-Gould, and L. W. Riley. 2001. Recombinant Mycobacterium tuberculosis protein associated with mammalian cell entry. Cell. Microbiol. 3:247-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cole, S. T., R. Brosch, J. Parkhill, T. Garnier, C. Churcher, D. Harris, S. V. Gordon, K. Eiglmeier, S. Gas, C. E. Barry, F. Tekaia, K. Badcock, D. Basham, D. Brown, T. Chillingworth, R. Connor, R. Davies, K. Devlin, T. Feltwell, S. Gentles, N. Hamlin, S. Holroyd, T. Hornby, K. Jagels, A. Krogh, J. McLean, S. Moule, L. Murphy, K. Oliver, J. Osborne, M. A. Quail, M. A. Rajandream, J. Rogers, S. Rutter, K. Seeger, J. Skelton, R. Squares, S. Squares, J. E. Sulston, K. Taylor, S. Whitehead, and B. G. Barrell. 1998. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature 393:537-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cywes, C., H. C. Hoppe, M. Daffe, and M. R. Ehlers. 1997. Nonopsonic binding of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to complement receptor type 3 is mediated by capsular polysaccharides and is strain dependent. Infect. Immun. 65:4258-4266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Downing, J. F., R. Pasula, J. R. Wright, H. L. D. Twigg, and W. J. D. Martin. 1995. Surfactant protein A promotes attachment of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to alveolar macrophages during infection with human immunodeficiency virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:4848-4852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dramsi, S., and P. Cossart. 1998. Intracellular pathogens and the actin cytoskeleton. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 14:137-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dye, C., S. Scheele, P. Dolin, V. Pathania, and M. C. Raviglione. 1999. Global burden of tuberculosis: estimated incidence, prevalence, and mortality by country. JAMA 282:677-686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elish, M. E., J. R. Pierce, and C. F. Earhart. 1988. Biochemical analysis of spontaneous fepA mutants of Escherichia coli. J. Gen. Microbiol. 134:1355-1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elsinghorst, E. A. 1994. Measurement of invasion by gentamicin resistance. Methods Enzymol. 236:405-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Finlay, B. B., and P. Cossart. 1997. Exploitation of mammalian host cell functions by bacterial pathogens. Science 276:718-725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flesselles, B., N. N. Anand, J. Remani, S. M. Loosmore, and M. H. Klein. 1999. Disruption of the mycobacterial cell entry gene of Mycobacterium bovis BCG results in a mutant that exhibits a reduced invasiveness for epithelial cells. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 177:237-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henderson, I. R., R. Cappello, and J. P. Nataro. 2000. Autotransporter proteins, evolution and redefining protein secretion. Trends Microbiol. 8:529-532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Henderson, I. R., F. Navarro-Garcia, and J. P. Nataro. 1998. The great escape: structure and function of the autotransporter proteins. Trends Microbiol. 6:370-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hernandez-Pando, R., M. Jeyanathan, G. Mengistu, D. Aguilar, H. Orozco, M. Harboe, G. A. W. Rook, and G. Bjune. 2000. Persistence of DNA from Mycobacterium tuberculosis in superficially normal lung tissue during latent infection. Lancet 356:2133-2138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Isberg, R. R., D. L. Voorhis, and S. Falkow. 1987. Identification of invasin: a protein that allows enteric bacteria to penetrate cultured mammalian cells. Cell 50:769-778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Just, I., J. Selzer, M. Wilm, C. von Eichel-Streiber, M. Mann, and K. Aktories. 1995. Glucosylation of Rho proteins by Clostridium difficile toxin B. Nature 375:500-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klauser, T., J. Pohlner, and T. F. Meyer. 1990. Extracellular transport of cholera toxin B subunit using Neisseria IgA protease β-domain: conformation-dependent outer membrane translocation. EMBO J. 9:1991-1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klauser, T., J. Pohlner, and T. F. Meyer. 1992. Selective extracellular release of cholera toxin B subunit by Escherichia coli: dissection of Neisseria IgA β-mediated outer membrane transport. EMBO J. 11:2327-2335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Konieczny, M. P., M. Suhr, A. Noll, I. B. Autenrieth, and M. A. Schmidt. 2000. Cell surface presentation of recombinant (poly-)peptides including functional T-cell epitopes by the AIDA autotransporter system. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 27:321-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Konieczny, M. P. J., I. Benz, B. Hollinderbäumer, C. Beinke, M. Niederweis, and M. A. Schmidt. 2001. Modular structure of the AIDA autotransporter translocator: evidence for a transmembrane β-sheet core stabilized by a surface-exposed N-terminal domain. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 80:19-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lattemann, C. T., J. Maurer, E. Gerland, and T. F. Meyer. 2000. Autodisplay: functional display of active β-lactamase on the surface of Escherichia coli by the AIDA-I autotransporter. J. Bacteriol. 182:3726-3733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lecuit, M., H. Ohayon, L. Braun, J. Mengaud, and P. Cossart. 1997. Internalin of Listeria monocytogenes with an intact leucine-rich repeat region is sufficient to promote internalization. Infect. Immun. 65:5309-5319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Loveless, B. J., and M. H. Saier, Jr. 1997. A novel family of channel-forming, autotransporting, bacterial virulence factors. Mol. Membr. Biol. 14:113-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oelschlaeger, T. A., and D. J. Kopecko. 2000. Microtubule dependent invasion pathways of bacteria. Subcell. Biochem. 33:3-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pohlner, J., R. Halter, K. Beyreuther, and T. F. Meyer. 1987. Gene structure and extracellular secretion of Neisseria gonorrhoeae IgA protease. Nature 325:458-462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosenshine, I., S. Ruschkowski, and B. B. Finlay. 1994. Inhibitors of cytoskeletal function and signal transduction to study bacterial invasion. Methods Enzymol. 236:467-476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schlesinger, L. S. 1993. Macrophage phagocytosis of virulent but not attenuated strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is mediated by mannose receptors in addition to complement receptors. J. Immunol. 150:2920-2930. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schlesinger, L. S., C. G. Bellinger-Kawahara, N. R. Payne, and M. A. Horwitz. 1990. Phagocytosis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is mediated by human monocyte complement receptors and complement component C3. J. Immunol. 144:2771-2780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schorey, J. S., M. C. Carroll, and E. J. Brown. 1997. A macrophage invasion mechanism of pathogenic mycobacteria. Science 277:1091-1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shepard, C. C. 1955. Phagocytosis by HeLa cells and their susceptibility to infection by human tubercle bacilli. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 90:392-396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Suhr, M., I. Benz, and M. A. Schmidt. 1996. Processing of the AIDA-I precursor: removal of AIDAc and evidence for the outer membrane anchoring as a β-barrel structure. Mol. Microbiol. 22:31-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tekaia, F., S. V. Gordon, T. Garnier, R. Brosch, B. G. Barrell, and S. T. Cole. 1999. Analysis of the proteome of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in silico. Tuber. Lung Dis. 79:329-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]