Abstract

1. The patterns of facilitation and inhibition of the Sa and Sb components of the post-ganglionic compound action potential after a single conditioning stimulus were different and dependent on stimulus parameters.

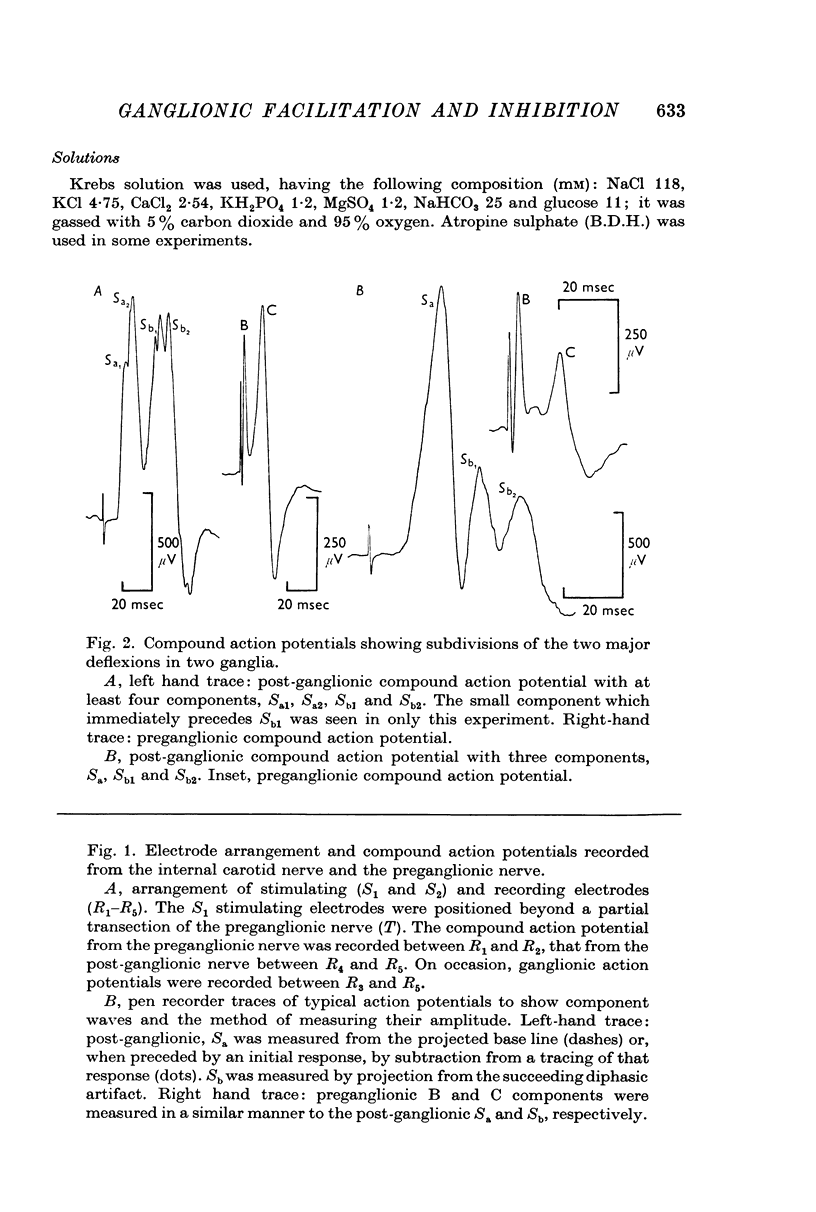

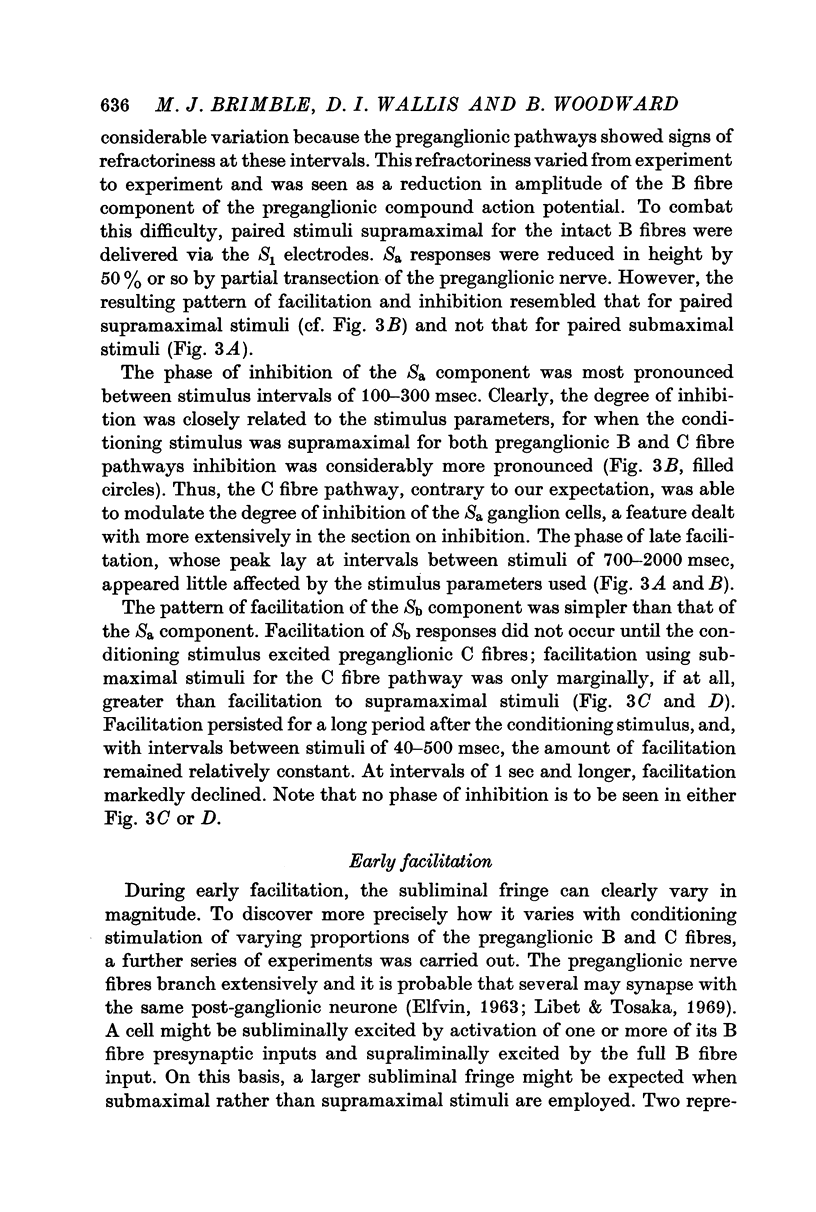

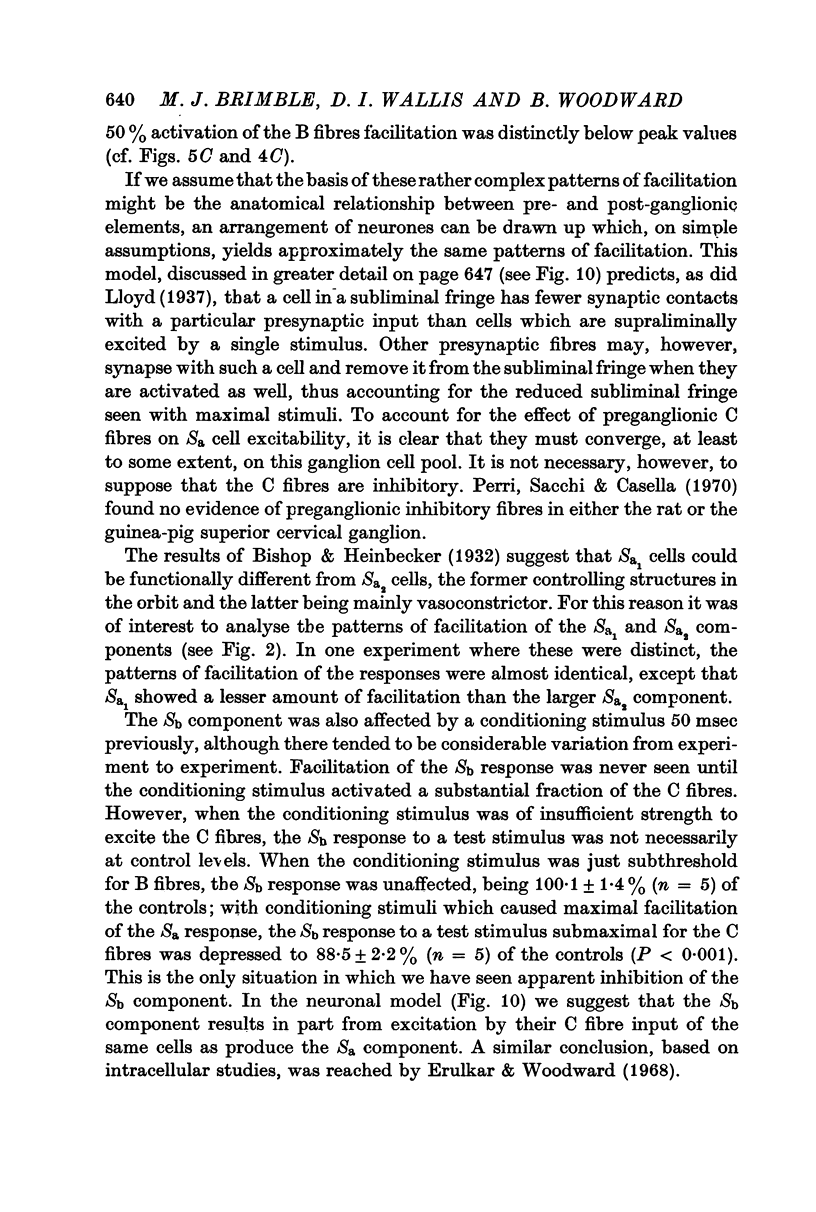

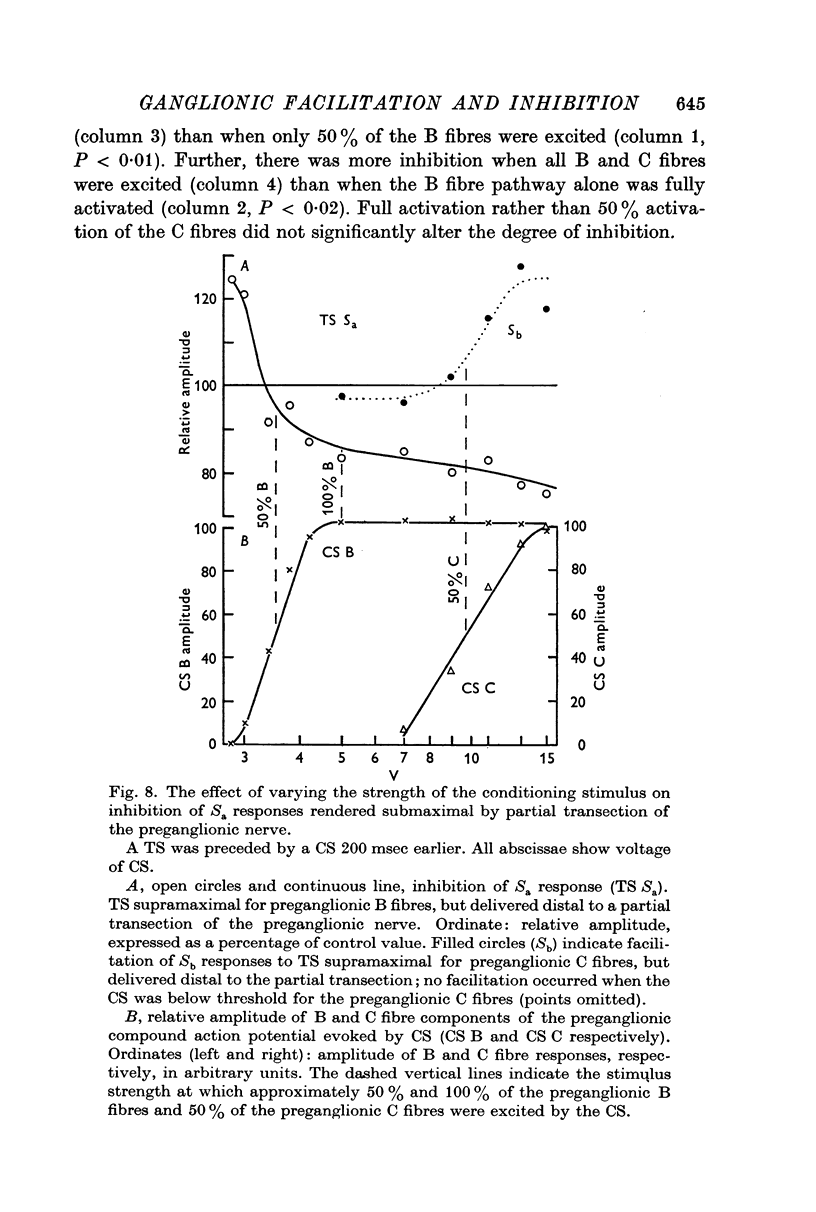

2. With submaximal conditioning and test stimuli, the Sa component showed a phase of early facilitation (40-75 msec after the conditioning stimulus) followed by a prolonged tail of facilitation. With maximal stimuli, early facilitation and late facilitation (700-2000 msec after the conditioning stimulus) were separated by a phase of inhibition or relative inhibition, most pronounced 100-300 msec after the conditioning stimulus.

3. During early facilitation, a submaximal Sa response was facilitated by 33·1 ± 3·9%, while a maximal Sa response was facilitated by 14·5 ± 2·9%.

4. Providing preganglionic C fibres were excited, facilitation of the Sb component remained relatively constant for 40-500 msec after the conditioning stimulus, with no phase of inhibition.

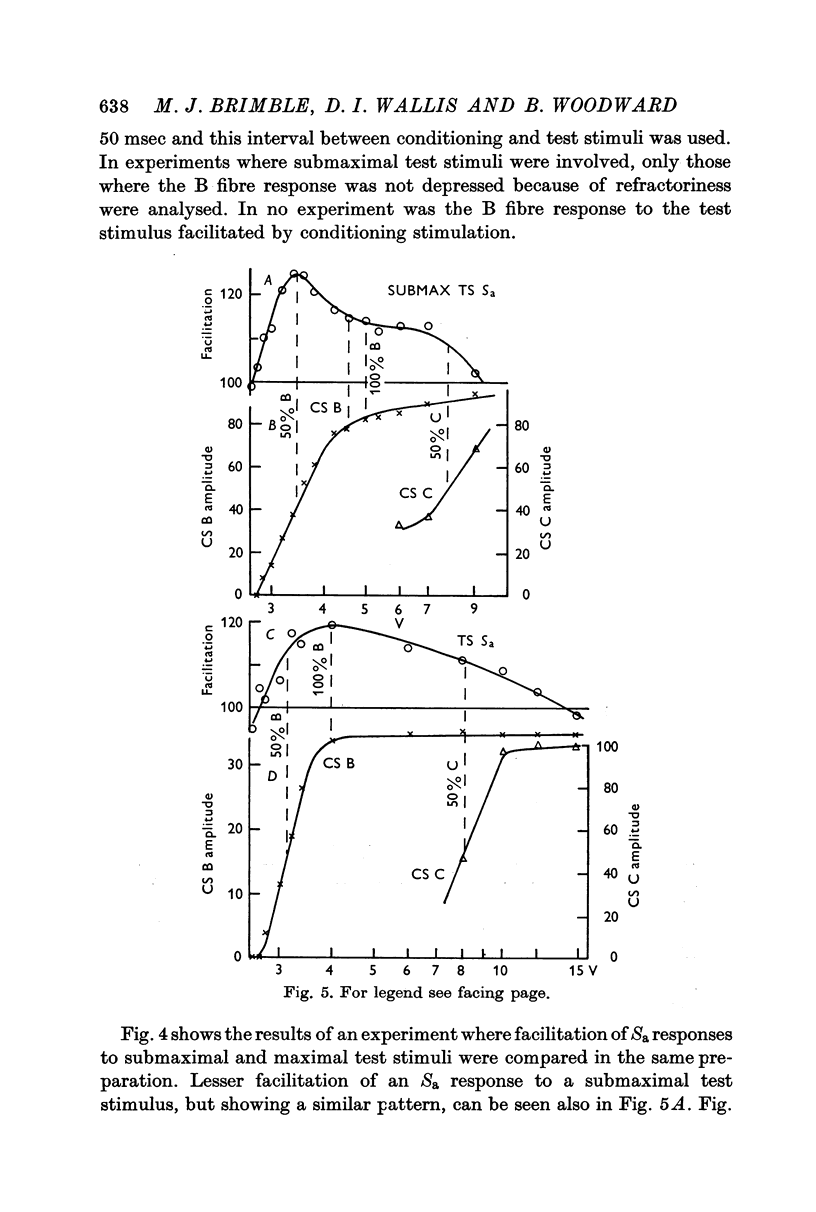

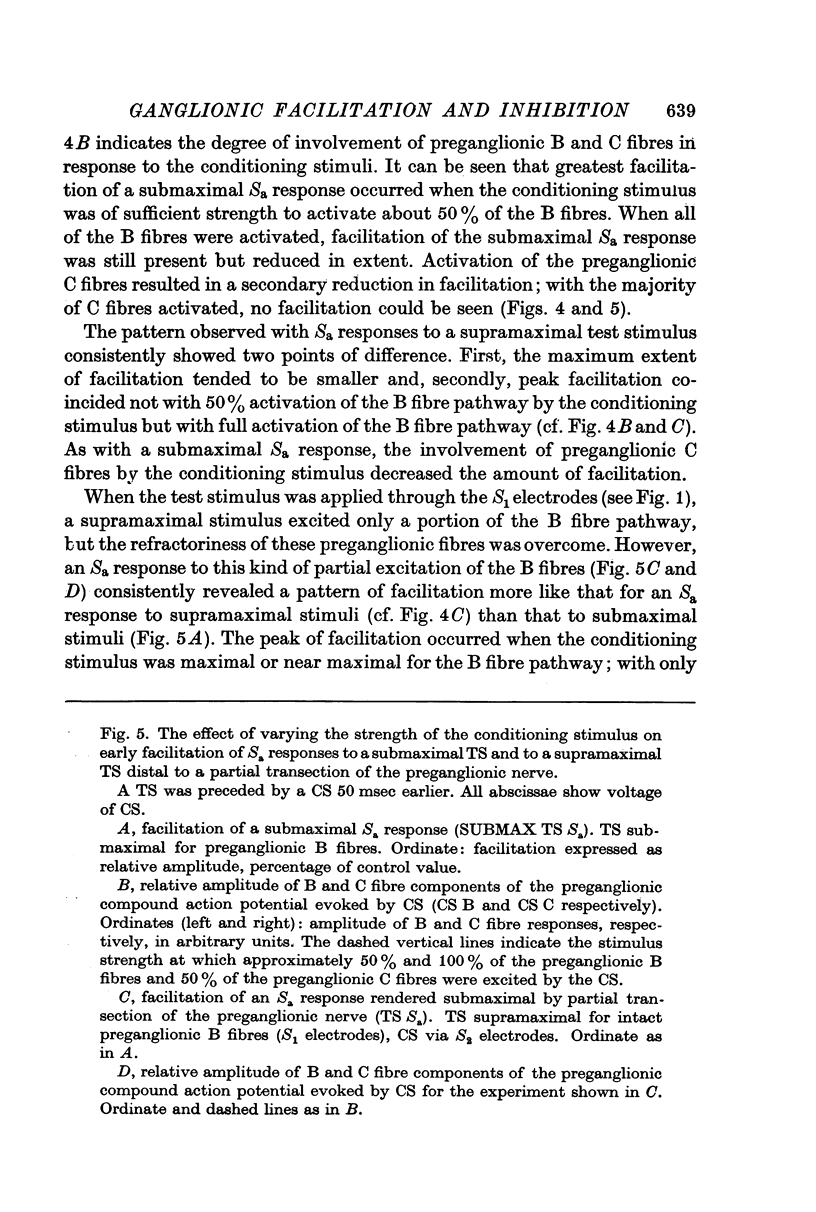

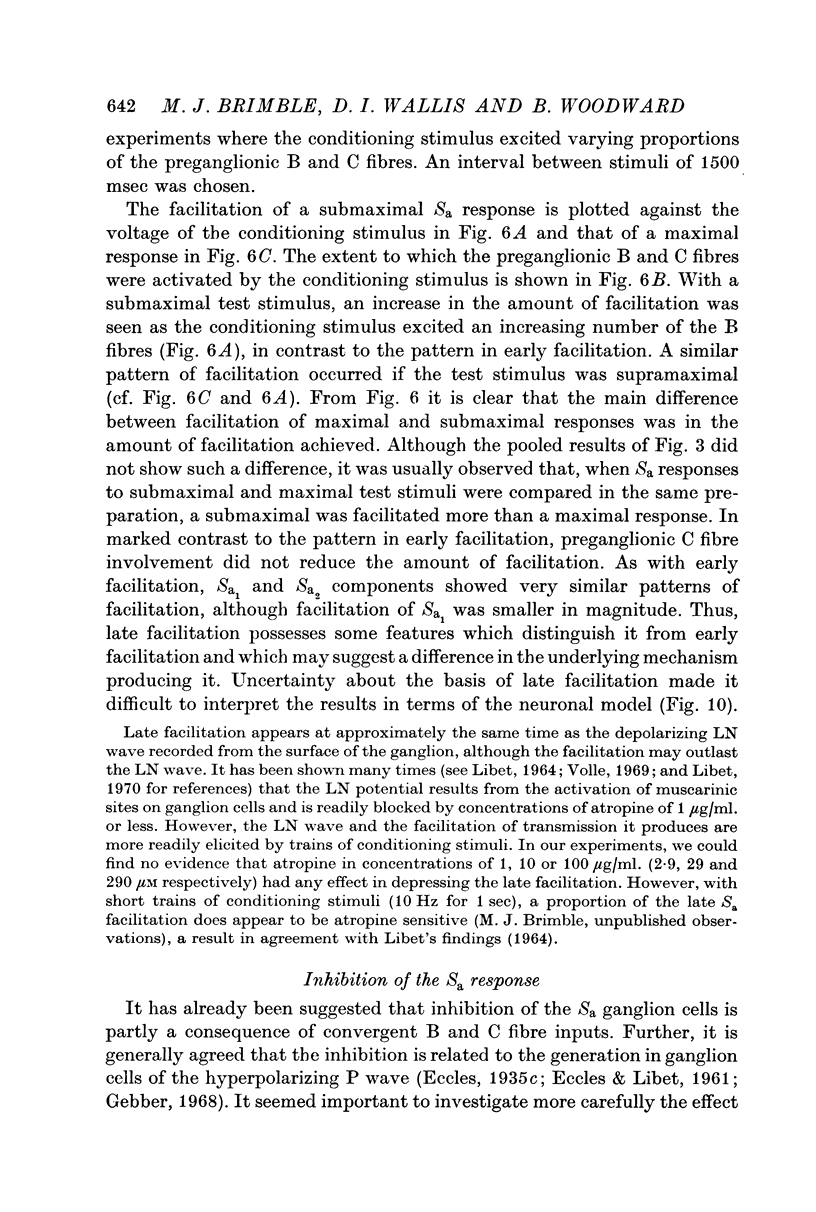

5. Early facilitation of submaximal Sa responses was greatest when the conditioning stimulus excited about 50% of the preganglionic B fibres, but that of maximal responses was greatest when the conditioning stimulus excited all the B fibres. The preganglionic C fibres modulated facilitation of the Sa component. Maximal facilitation of this component was associated with depression of the Sb component.

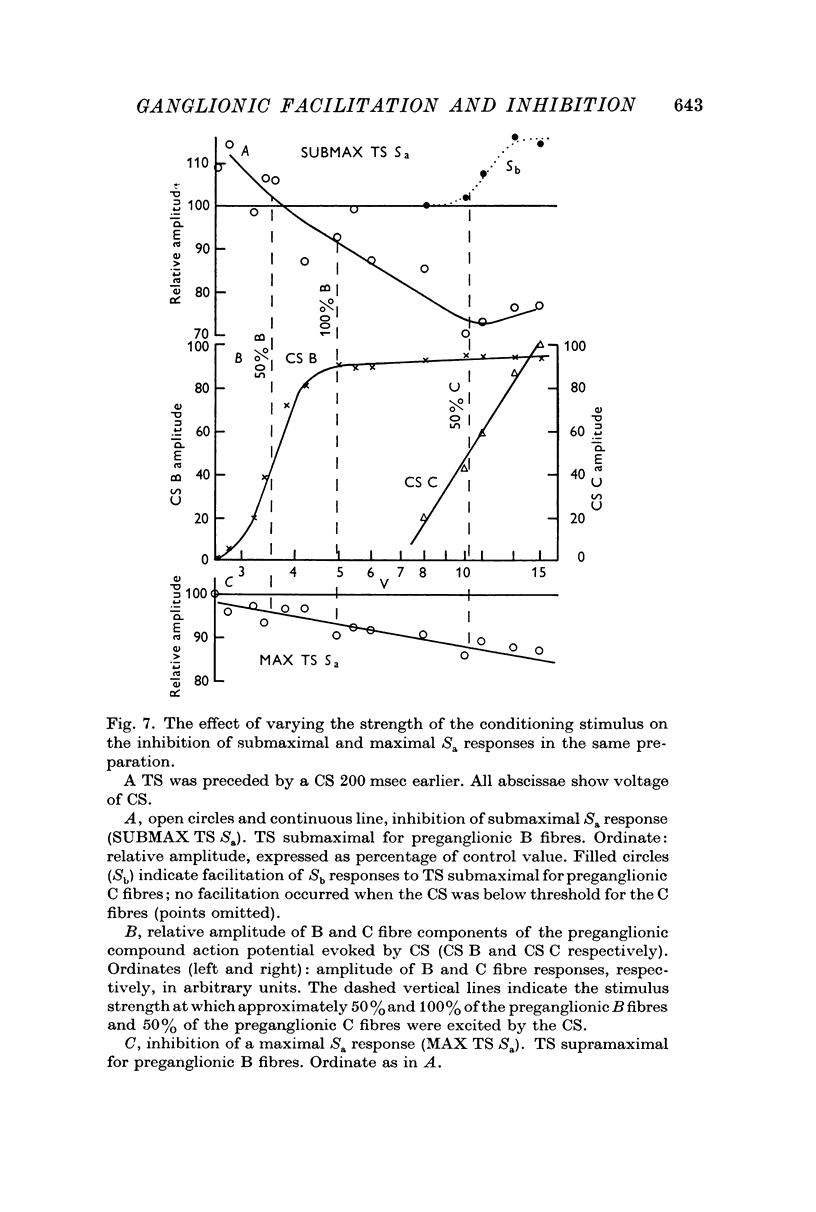

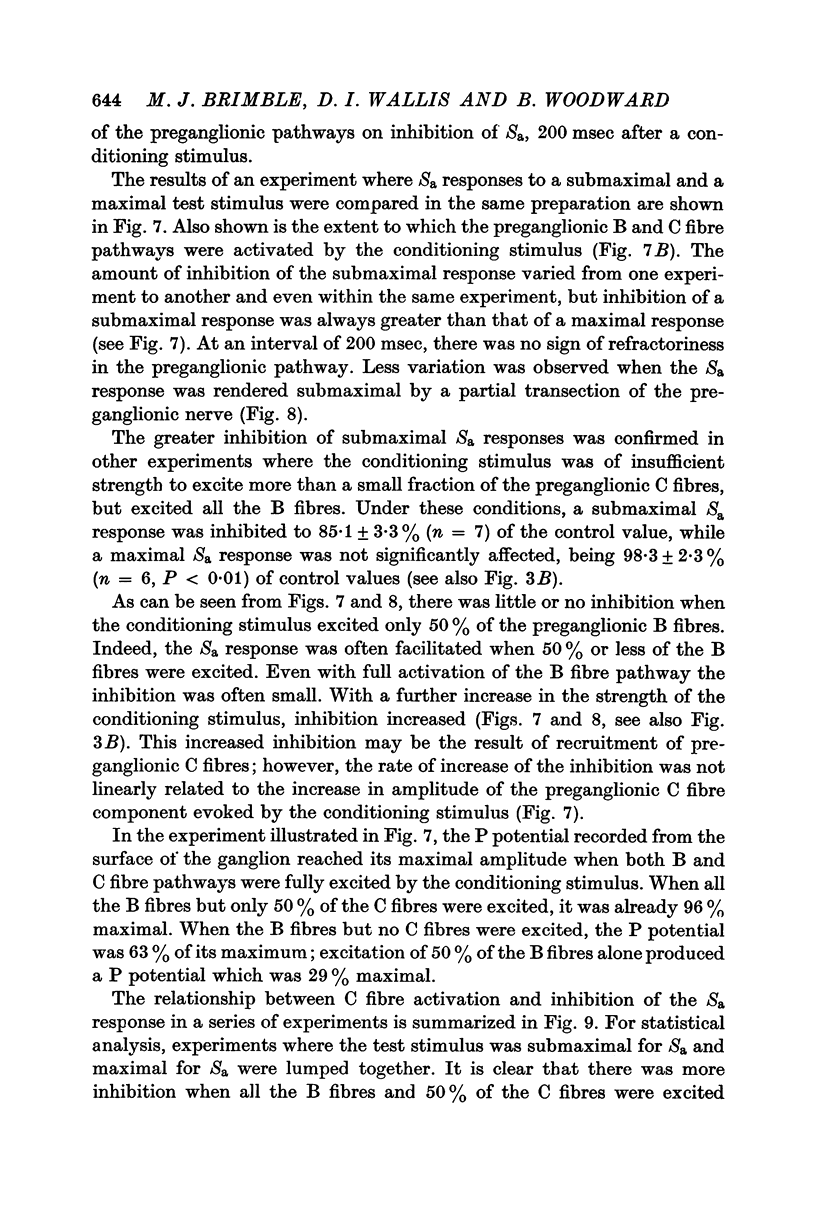

6. Submaximal Sa responses are more strongly inhibited than maximal Sa responses 200 msec after a conditioning stimulus. The C fibre pathway seems able to modulate the degree of inhibition of the Sa ganglion cells.

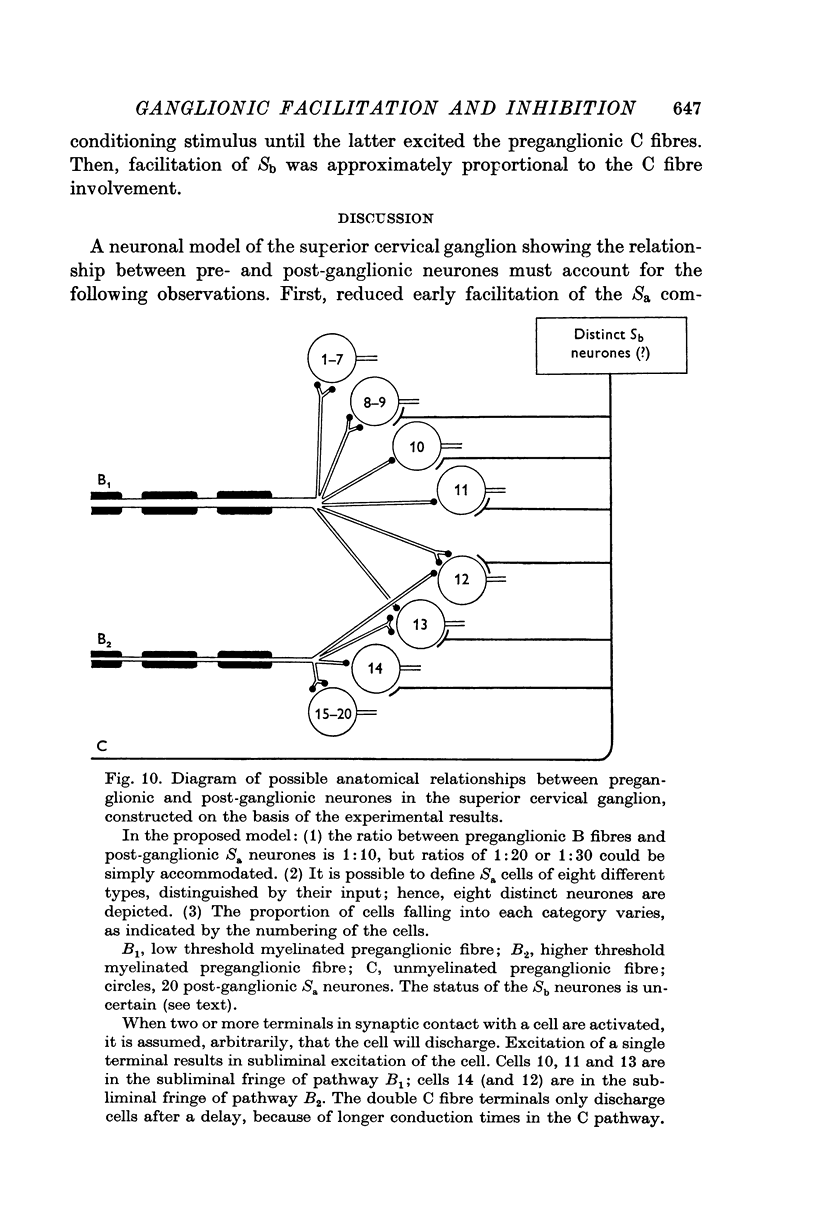

7. A neuronal model with divergent and convergent preganglionic B and C fibres supplying Sa ganglion cells is consistent with the results. The preganglionic input is able to vary the size of the subliminal fringe. The Sb component is in part due to the Sa ganglion cells firing to their C fibre input.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- DOUGLAS W. W., RITCHIE J. M. The conduction of impulses through the superior cervical and accessory cervical ganglia of the rabbit. J Physiol. 1956 Jul 27;133(1):220–231. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1956.sp005580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas W. W., Lywood D. W., Straub R. W. On the excitant effect of acetylcholine on structures in the preganglionic trunk of the cervical sympathetic: with a note on the anatomical complexities of the region. J Physiol. 1960 Sep;153(2):250–264. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1960.sp006533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunant Y. Organisation topographique et fonctionnelle du ganglion cervical supérieur chez le Rat. J Physiol (Paris) 1967 Jan-Feb;59(1):17–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ECCLES R. M., LIBET B. Origin and blockade of the synaptic responses of curarized sympathetic ganglia. J Physiol. 1961 Aug;157:484–503. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1961.sp006738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ECCLES R. Action potentials of isolated mammalian sympathetic ganglia. J Physiol. 1952 Jun;117(2):181–195. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1952.sp004739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles J. C. Facilitation and inhibition in the superior cervical ganglion. J Physiol. 1935 Oct 26;85(2):207–238.3. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1935.sp003314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles J. C. Slow potential waves in the superior cervical ganglion. J Physiol. 1935 Dec 16;85(4):464–501. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1935.sp003333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles J. C. The action potential of the superior cervical ganglion. J Physiol. 1935 Oct 26;85(2):179–206.2. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1935.sp003313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erulkar S. D., Woodward J. K. Intracellular recording from mammalian superior cervical ganglion in situ. J Physiol. 1968 Nov;199(1):189–203. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1968.sp008648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebber G. L. Prolonged ganglionic facilitation and the positive afterpotential. Int J Neuropharmacol. 1968 May;7(3):195–205. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(68)90027-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koketsu K. Cholinergic synaptic potentials and the underlying ionic mechasims. Fed Proc. 1969 Jan-Feb;28(1):101–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosterlitz H. W., Lees G. M., Wallis D. I. Resting and action potentials recorded by the sucrose-gap method in the superior cervical ganglion of the rabbit. J Physiol. 1968 Mar;195(1):39–53. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1968.sp008445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosterlitz H. W., Wallis D. I. The effects of hexamethonium and morphine on transmission in the superior cervical ganglion of the rabbit. Br J Pharmacol Chemother. 1966 Feb;26(2):334–344. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1966.tb01912.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LARRABEE M. G., POSTERNAK J. M. Selective action of anesthetics on synapses and axons in mammalian sympathetic ganglia. J Neurophysiol. 1952 Mar;15(2):91–114. doi: 10.1152/jn.1952.15.2.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIBET B. SLOW SYNAPTIC RESPONSES AND EXCITATORY CHANGES IN SYMPATHETIC GANGLIA. J Physiol. 1964 Oct;174:1–25. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1964.sp007471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libet B. Generation of slow inhibitory and excitatory postsynaptic potentials. Fed Proc. 1970 Nov-Dec;29(6):1945–1956. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libet B., Tosaka T. Slow inhibitory and excitatory postsynaptic responses in single cells of mammalian sympathetic ganglia. J Neurophysiol. 1969 Jan;32(1):43–50. doi: 10.1152/jn.1969.32.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd D. P. The excitability states of inferior mesenteric ganglion cells following preganglionic activation. J Physiol. 1939 May 15;95(4):464–475. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1939.sp003743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd D. P. The origin and nature of ganglion after-potentials. J Physiol. 1939 Jul 14;96(2):118–129. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1939.sp003762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd D. P. The transmission of impulses through the inferior mesenteric ganglia. J Physiol. 1937 Dec 14;91(3):296–313. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1937.sp003561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perri V., Sacchi O., Caella C. Electrical properties and synaptic connections of the sympathetic neurons in the rat and guinea-pig superior cervical ganglion. Pflugers Arch. 1970;314(1):40–54. doi: 10.1007/BF00587045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMUEL E. P. Chromidial studies on the superior cervical ganglion of the rabbit; caudally projected postganglionic axons; intercalary commissural neurons. J Comp Neurol. 1953 Feb;98(1):93–111. doi: 10.1002/cne.900980107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volle R. L. Ganglionic transmission. Annu Rev Pharmacol. 1969;9:135–146. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.09.040169.001031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]