Abstract

Dimerization of genomic RNA is directly related with the event of encapsidation and maturation of the virion. The initiating sequence of the dimerization is a short autocomplementary region in the hairpin loop SL1. We describe here a new solution structure of the RNA dimerization initiation site (DIS) of HIV-1Lai. NMR pulsed field-gradient spin-echo techniques and multidimensional heteronuclear NMR spectroscopy indicate that this structure is formed by two hairpins linked by six Watson–Crick GC base pairs. Hinges between the stems and the loops are stabilized by intra and intermolecular interactions involving the A8, A9 and A16 adenines. The coaxial alignment of the three A-type helices present in the structure is supported by previous crystallography analysis but the A8 and A9 adenines are found in a bulged in position. These data suggest the existence of an equilibrium between bulged in and bulged out conformations in solution.

INTRODUCTION

Retroviruses are unique in having a diploid genome (1). This diploid feature is directly involved in different stages of the virion life cycle such as recombination and encapsidation (2–7). Electron microscopy of HIV-1 has shown the RNA genome to consist of two identical genomic RNA strands joined within their 5′ leader, at a 100 bases long region defined as the dimer linkage structure (DLS) (8–11). In the HIV-1Lai strain, the dimerization initiation site (DIS) is a 6 nt autocomplementary sequence located in the highly conserved 35 bases long sequence stem–loop (SL1) (Figure 1) (12,13). Mutations in the DIS region or deletion of the entire autocomplementary sequence have been shown to affect the yield of dimer formation consequently reducing virion infectivity (14–22). Further more this deficit in virulence is closely implicated with defects in encapsidation, indicating a direct involvement between dimerization and formation of the capsid.

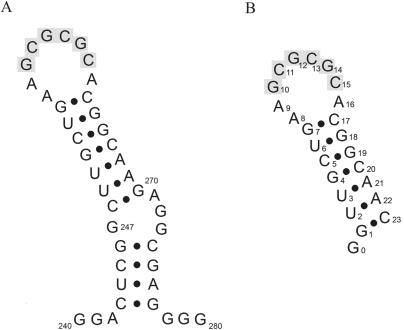

Figure 1.

(A) The SL1 sequence of the genomic RNA HIV-1Lai. (B) The SL1 sequence synthesized for NMR studies. Bases in SL1 are numbered with respect to the cap site in the HIV-1 genomic transcript. The 6 nt autocomplementary sequence is highlighted in grey. In the numbering of the Mal variant genome, the adenines 256, 257 and 264 are numbered 272, 273 and 280, respectively.

In vitro studies with 200 nt RNA sequences containing the DIS region show that HIV-1 dimer formation is initiated via a loop–loop interaction between two RNA molecules (23,24). This metastable complex is converted at 55°C, or at lower temperatures in the presence of the NCp7 protein, into a more stable conformation, an extended dimer (23,25–27). Shorter sequences comprising the entire 35 nt SL1 sequence (28) or its extremity of 23 nt (29,30) remain able to dimerize into two different conformations of different stabilities. The structure of the loop–loop dimer or ‘kissing complex’ has been resolved by NMR (31) and crystallography (32). Both studies utilize different RNA sequences. The NMR sequence presents a modification of the base pair order in the stem contrary to the crystallography sequence. Although both studies report identical nucleotide sequences of the loop, discrepancies appear when both proposed structures are compared. The NMR solution structure shows a symmetrical homodimer where the average plane of the loops is roughly perpendicular to the axis of the stems whereas in the crystallographic structure it shows a perfect coaxial alignment with the stems. Unlike the NMR structure where all the bases are inside the RNA molecule, the crystallographic structure presents the A8 and A9 adenines as stacked in a bulged out conformation. The NMR structure shows that the last base pair of the stem (G7-C17) is not paired contrary to the model proposed by crystallography where bases appear paired. Previous NMR findings from our laboratory have confirmed the presence of base pair (G7-C17) in the loop–loop complex in the 23 nt sequence in the wild-type. To clarify these contradictory reports, we solved the 23 nt structure of the SL1 region in the HIV-1Lai wild-type without base pair rearrangement in the stem by multidimensional NMR spectroscopy. We found a new solution structure of the ‘kissing complex’. Its structure is composed by two hairpins, coaxially aligned, linked by their autocomplementary sequence with the loop adenines appearing in a bulged in position.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

RNA synthesis and folding

RNA strands were synthesized by in vitro transcription with T7 RNA polymerase using synthetic templates as described previously (33). Template oligonucleotides (5′-GTTGCCGTGCGCGCTTCAGCAACCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTA and 5′- TAATACACT CACTATAG) were purchased from Eurogentec (Belgium). T7 RNA polymerase was isolated from Escherichia coli strain BL21/PAR1219 as described in Davanloo et al. (34). RNAs were synthesized with unlabelled NTPs (Sigma) or labelled 15N/13C NTPs (Silantes). Following phenol extraction and ethanol precipitation, all RNA samples were purified by PAGE under denaturing conditions with 8 M Urea. The SL1 24 nt RNA (Figure 1) was recovered by diffusion in water. RNA was desalted by reverse phase chromatography on Sep-Pak C18 (Waters) and by gel filtration on DG-10 column (Bio-Rad). A total of 10 µM desalted sample was refolded by heating at 90°C (3 min) and snap-frozen at −20°C. The sample was concentrated by lyophilization. The final concentrations of the unlabelled and labelled SL1 24 nt were 2 mM and 0.6 mM, respectively. Each sample was placed in a Shigemi tube in 170 µl of 90% water, 10% deuterium oxide at pH 5.7, without addition of any salt for the experiments involving exchangeable protons. For the non-exchangeable protons experiments, samples were lyophilized and solved again in 100% deuterium oxide. The NMR experiment was generally run below 12°C to avoid the transition toward the extended structure.

NMR spectroscopy

NOESY, DQF-COSY, TOCSY, 15N and 13C HSQC, HNN-COSY, HMBC, NMR pulsed field-gradient spin-echo experiments (35) were run on a Varian 600 MHz UNITY INOVA spectrometer. 15N and 13C double-half-filter NOESY experiments were run on a Varian 600 MHz and on an 800 MHz UNITY INOVA spectrometer.

Pf1 phage was purchased from ASLA Ltd (Riga, Latvia). Phage concentrations were adjusted by weighing appropriate amounts of a 50 mg/ml stock solution in H2O. Phage alignment was verified by measuring the splitting of the HOD signal in 90% H2O/10% D2O. Resonance assignments are reported relative to DSS.

Structure refinement

The structure of the loop–loop complex was calculated using torsion angle molecular dynamics (TAMD) as described by Stallings and Moore (36). First, one hundred random structures were generated using CNS 1.0 (37). The basic started structures were subjected to a simulated annealing-restrained molecular dynamics protocol in torsion angle space. TAMD consisted of a high-temperature torsion angle dynamics for a total of 15 ps at 20 000 K with a Van der Waals scale factor of 0.1. The molecules were then cooled to 300 K in 4000 steps for 60 ps of torsion angle dynamics with a Van der Waals scale factor increased from 0.1 to 1. This was followed by another simulated annealing step in Cartesian space from 2000 K to 300 K in 3000 steps for 15 ps where the Van der Waals scale factor increased from 1 to 4, finalized by 2000 steps of Powell minimization with full electrostatic and Van der Waals terms. The structures with zero violation on NOE distance (0.2 Å), dihedral (5°) and with the lowest energies were selected. Molecular graphics image were visualized with the MOLMOL program (38). All helical parameters were determined using CURVES (39,40).

Coordinates

The coordinates of the eighteenth structures have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID code is 2F4X).

RESULTS

NMR spectroscopy and assignments

The sequential assignment of the imino and amino protons of the dimer was obtained by using a 80 ms mixing time NOESY spectrum recorded at 10°C. The three guanine imino protons of the loop were linked by hydrogen bonds to cytosines C11, C13, C15 and a sequential assignment G10-G14-G12 was observed. These data were confirmed by using the 15N HSQC and HNN-COSY spectra. 15N HSQC discriminated the 15NH belonging to T, G or U by their 15N chemical shifts (41). HNN-COSY (42) allowed the direct observation of hydrogen coupling by a cross hydrogen scalar coupling between the imino 15N1 of the donor guanines with the hydrogen bond acceptor 15N4 atom of the complementary cytosines, in the Watson–Crick base pairs. The pairing of G7 and of C17 bases, which is essential for the modelling, has been shown by several spectra. First, the connectivity 15N1-1H of G7 clearly appears on the 15N HSQC spectrum, demonstrating the pairing of G17. Second, the observation of two NH2-H5 connectivities on the 80 ms NOESY spectrum showed a rotation hindrance of the amino group of C17 and strongly suggested its pairing. Lastly, weak connectivity appeared between 15N1(G7) and the 15N4 (C17) on the HNN-COSY.

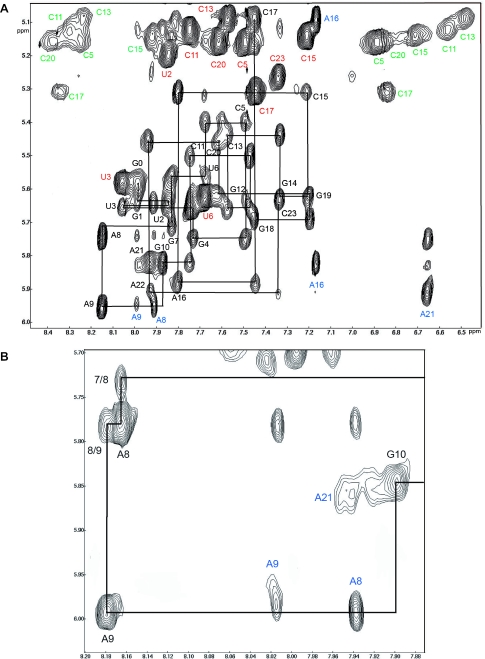

All the H6/8—H1′ connectivities, except the sequential way between H8(A9) and H1′(G10), were directly assigned on the NOESY spectra at 80 ms mixing time in H2O (Figure 2). H2 assignment of A8, A9 and A16 were discriminated from the corresponding H8 resonances by using their 13C2 and 13C8 chemical shifts on the HSQC spectra at 10°C. The assignments were confirmed using NOESY-HSQC, HCCH-TOCSY to connect H1′ to H2′, H1′ to H6 or H8 in HCN (43) as well as H8 to H2 of adenines in HMBC (44).

Figure 2.

(A) Sequential assignment of the NOESY spectra run in H2O at 10°C with 80 ms mixing time on the loose complex formed by SL1. The sequential assignment of the H8, H6 and H1′ protons as well as H5, H2 and the NH2 of cytosines is shown. (B) Expansion of a region shows clearly the connectivity H8(A9)-H1′(A8) at 20°C with 300 ms mixing time in D2O.

Size of the complex and special features

The diffusion coefficient was obtained by NMR pulsed field-gradient spin-echo techniques (35). The size of the loose complex was determined by comparing this coefficient with the extended complex and the mutated SL1-A12. These two structures were already characterized as an extended duplex of 2 × 24 nucleotides (28,45) and as a stem–loop monomer of 23 nt (46), respectively. At 10°C, the diffusion coefficients of the extended duplex and those of the loose complex were the same (0.52 ± 0.05 10−6 and 0.51 ± 0.05 10−6 cm2/s), showing a similar size (2 × 24mer). This result confirms the data of Muriaux et al. (27) showing that the loose duplex migration is similar to the extended duplex on non-denaturing PAGE on longer DIS sequences.

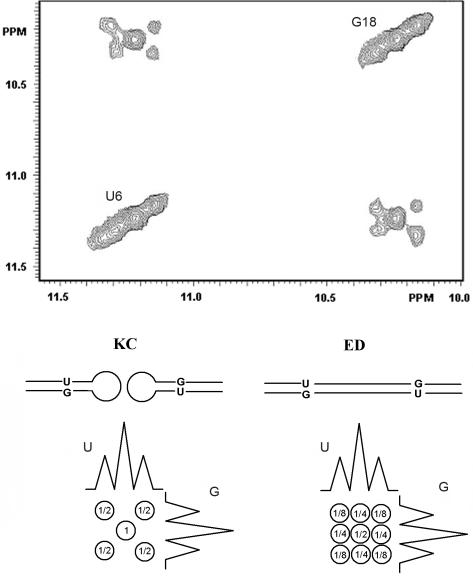

To discriminate between the presence of the loop–loop complex and that of the extended complex we performed NOESY WATERGATE. This was done without 15N decoupling during t1 and t2 at 80 ms mixing time on a 1:1 mixture of a labelled 13C15N SL1-24mer and an unlabelled SL1-24mer. As shown by Takashashi et al. (28), the N3H(U6)-N1H(G18) NOESY connectivity is predicted to show quite different patterns for the extended duplex and the loop–loop complex due to non existent 14NH-15NH connectivities in the loop complex. Figure 3 shows a clear pattern with a central connectivity 14N1H-14N3H surrounded by four smallest cross-peaks 15N1H-15N3H with J(15N,1H) = 95 Hz, in agreement with a loop–loop association. Confirmation of our NH assignments in the ‘kissing complex’ was obtained by 15N double-half-filter NOESY experiment on a mixing (1:1) of unlabelled SL1 and 13C15N labelled SL1 (47).

Figure 3.

Pattern of the NOE connectivity between N3H(U6) and N1H(G18) obtained on a NOESY spectra. This was run at 10°C without 15N decoupling during t1 and t2 on a mixture 1:1 formed by an unlabelled SL1 oligonucleotide and a 15N/13C labelled SL1 oligonucleotide. For an extended duplex, 25% of 14N-14N, 25% of 15N-15N and 50% of 14N-15N connectivities are expected due to the interaction between strands of different labelling. For the ‘kissing complex’, 50% of 14N-14N and 50% of 15N-15N connectivities are expected, due to the interaction between strands of same labelling. Following these data and taking into account the 15N1H coupling constant, a scheme shows the two different patterns predicted for an extended duplex (ED) and for a ‘kissing complex’ (KC), demonstrating that in our experimental conditions SL1 formed a loop–loop complex.

As expected for a loop–loop complex, the 15N→15N or the 14N→14N sub spectra showed only the connectivities between residues belonging to the stem while the 15N→14N or the 14N→15N sub spectra showed the connectivities NH(G10)-NH(G12) and NH(G12)-NH(G14) as well as the corresponding NH-NH2 connectivities.

Several unique features were noticed on the NOESY, COSY or TOCSY spectra. First, A8 and A9 were not found in anti conformation and their sugar in north conformation. Second, the H2 proton of A16 showed medium or strong connectivities with the H2 proton of A9 and with the H8 and H1′ protons of G10. Third, the imino proton of G10 showed connectivities with the H1′, H2 and H8 protons of A16.

NMR structure determination and general description of the loose complex

The part of the dimer corresponding to the stems (G0 to G7 and C17 to C23) and to the loops (G10 to C15) showed a typical double helix A-type conformation and no ambiguity with the intra and intermolecular connectivities assignment. The A8 and A9 nucleotides adopt a different conformation accommodating the transition from an A-RNA conformation to a loop–loop association with a minimum of constraints. They present original connectivities whose discrimination between inter-strand and intra-strand is not trivial. In order to choose between intra and inter connectivities, four [1H, 1H]NOESY spectra were obtained using a 13C(ω1,ω2) double-half-filter where each half-filter was applied alternatively. A linear combination of these four spectra gave separately the 13C→13C, 13C→12C and 12C→12C connectivities (48). The strong NOE connectivities H8(A8)-H1′(A8) and H8(A9)-H1′(A9) were found intra-strand and H1′(G10)-H2(A16), H8(G10)-H2(A16), H2(A8)-H1′(A9) inter-strand. We attempted to obtain supplementary information concerning the relative orientation of the loop and the stem by measuring residual dipolar coupling. This experiment, which requires partial orientation of the molecule, produced a transition of the ‘kissing complex’ toward the extended dimer conformation in presence of phages. Classical A–helix connectivities were observed for G1 to G7, G10 to C15 and C17 to C23. For these nucleotides, the following dihedral restraints were used: α = −85 ± 50°, β = −165 ± 50°, γ = 53 ± 50°, ɛ = 180 ± 50° and ς = −60 ± 50° (Table 1). Cross-validation of our structure was obtained by removing 25% of the restraints involving G7, A8, A9, G10, A16 and C17. The eighteen converged structures showed no violation of distance restraints >0.2 Å. A very weak connectivity H2(A9)-H1′(G10) was observed at 300 ms mixing time, corresponding to a distance of 6.2 Å in our structures. It can be explained by the spin diffusion way H2(A9)→H2(A16)→H1′(G10).

Table 1.

NMR restraints and statistics for the 18 converged structures

| Distance and dihedral restraints | |

| Intra-residue distance restraints | 120 |

| Inter-residue distance restraints | 236 |

| Hydrogen bonding distance restraints | 108 |

| Total distance restraints | 464 |

| Torsion angle restraints for sugar pucker | 92 |

| Backbone torsion angle restraints | 200 |

| Total angle restraints | 292 |

| Total restraints | 756 |

| Precision of lowest-energy structures | |

| Number of structures | 18 |

| NMR distance restraint violations (up to 0.2 Å) | 0 |

| R.m.s.da | |

| Stem helix (bases G1-G7, C17-C23) | 0.59 ± 0.15 Å |

| Central stem helix (bases G10-C15) | 0.53 ± 0.17 Å |

| Adenines of junction | 0.48 ± 0.20 Å |

| Whole kissing complex | 0.59 ± 0.16 Å |

| Energy | |

| Total Energy | −1255 ± 29 kcal.mol−1 |

aR.m.s.d: root mean square deviation ± SD in position of heavy atoms compared to the global average structure.

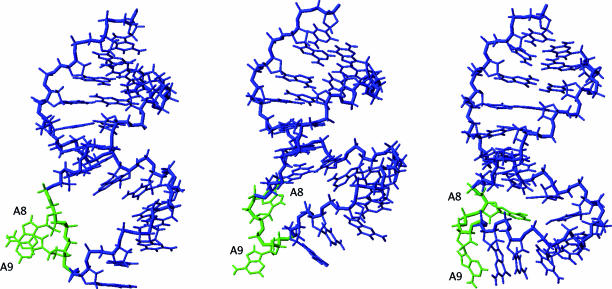

The solution structure of the loose complex of HIV-1Lai showed a symmetric homodimer fully paired on the stems and the loops (Figure 4). These two loops, which are hydrogen bonded by six central GC base pairs, were roughly located in the axe of the stems. The overall phosphodiester backbone was similar to the canonical A-type geometry, except for the residues A8 and A9 whose sugars were in south conformation and positioned syn.

Figure 4.

Perpendicularly views of the average structure obtained with the 18 converged structures. G0 that was not restrained was not presented in the figure. The A8, A9 and A16 nucleotides are shown in green.

The molecular edifice was stabilized by stacking of A16 with G7-C17 of the other strand, in agreement with the observed upfield shift resonance of H1′(C17) (5.1 p.p.m.).

DISCUSSION

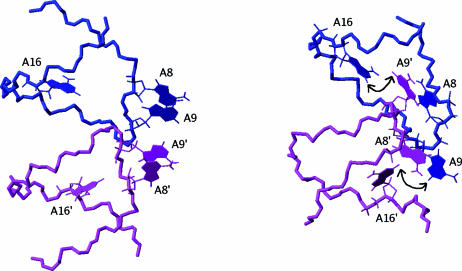

The solution structure presented in our NMR study is very similar to the crystallographic structure (32) (Figure 5), however significant differences emerged when comparisons were made with the NMR structure obtained in the study by Mujeeb et al. (31). The orientation of the loops versus the stems represented a major difference between these two NMR structures (Figure 5). A valid explanation accounting for this difference lies with the discrepancies in obtaining the restraints for the structures in both studies (Table 2). The overall conformation of our ‘kissing complex’ presented similarities with the crystallographic structure (23), particularly in the co-linearity of the three helices as well as the stacking of A16 with G7-C17. However, several elements involving the A8, A9 and A16 nucleotides were different. A9 was found in proximity of A16 in agreement with a medium NOE between H2(A9) and H2(A16) (Table 2). In addition, the sequential way between A8-A9 indicated the proximity of A8 to A9 of the same strand. These data did not support the conformational model where A8 and A9 are found in the bulged out position as observed in the crystallographic structure. It is worth noting that in our structure, the relative positions of the four adenines A8 and A9 of the two strands were such that their H2 and H8 resonances were exposed to small ring current effect supported by their chemical shift (Figure 6). On the contrary, in the crystallographic structure A8 and A9 were found stacked. The bulged out conformation of A8 and A9 generated a ‘hole’ between G7-C17 and A16 (C1′(A16)-C1′(C17) = 15 Å), which did not exist in our solution structure (C1′(A16)-C1′(C17) = 5 Å) (Figure 5). The bulging out phenomenon was a destabilizing factor, which can be compensated by the interdimer stacking of the adenines in the crystalline form. In solution, the absence of such a self-association could explain the bulged in conformation where the corresponding hole is filled by A8 and A9.

Figure 5.

Comparison between the crystallographic structure by Ennifar et al. (32) (left), our solution structure (middle) and the NMR structure by Mujeeb et al. (31) (right). The hole generated by the bulged out conformation can be observed on the left-structure. In order to improve the sight of each nucleotide, only one strand is shown.

Table 2.

| Nature of the restraints | Experimental data | Crystallographic structure |

|---|---|---|

| Differences between our experimental data and the structural elements of the crystallographic structure (32) | ||

| H8(A9)-H1′(A8) | Weak | AA > 5 and AB > 10 Å |

| H1′(A9)-H2(A8) | Weak | AA > 5 and AB > 10 Å |

| H2(A9)-H2(A16) | Medium | AA and AB > 10 Å |

| H8(A8)-H1′(A8) | syn | anti |

| H8(A9)-H1′A9) | syn | anti |

| H8(G7)-H8(A8) | Medium | AA and AB > 10 Å |

| H2(A9)-H1′(G10) | Very weak | AA and AB >10 Å no possible pathway for spin diffusion |

| H2(A8)-H8(A9) | 4.5 Å | >10 Å |

| H2(A8)-H2(A9) | No NOE | 4.3 Å |

| A8 | South | North |

| G7 | North | South |

| δ H2A8 | 8.17 p.p.m.a* | A8 and A9 stacked |

| δ H8A8 | 7.91 p.p.m.a* | |

| δ H2A9 | 8.18 p.p.m.a* | |

| δ H8A9 | 8.0 p.p.m.a* | |

| A8 and A9 unstacked | ||

| Nature of the restraints | Experimental data | Other NMR structure |

| Differences between our experimental data and the structural elements of the Mujeeb et al. NMR structure (31) | ||

| H2(A16)-H1′(C17) | Strong | >7 Å |

| H5(C17)-H1′(A16) | Weak | 2.6 Å |

| H1′(A9)-H2(A8) | Medium | >7 Å |

| H2(A8)-H8(A9) | Weak | >7 Å |

| H6(C17)-H8(A16) | Medium | 6.3 Å |

| A8 | syn | anti |

| A9 | syn | anti |

| C17 | anti | syn |

| H2(A8)-H2(A16) | No NOE | 3.5 Å |

| H2(A8)-H2(A9) | No NOE | 3.4 Å |

| H2(A16)-H5(C17) | No NOE | 3.7 Å |

| G7-C17 | Paired | Unpaired |

| A8,A9 | South | North |

| G7 | North | South |

AA and AB characterize distances involving intra- and inter-strand residues.

Strong, medium, weak and very weak are relative to the intensity of the NOEs.

aThe value of the chemical shift of H2 and H8 of A8 and A9 indicated that their H2 and H8 proton are not efficiently shifted upfield by a ring current effect and consequently are far from ring of other bases.

Figure 6.

Comparison between the bulged in (32) and bulged out conformations showing the relative location of the A8, A9 and A16 adenines. The nearest adenines are A8 and A9 in the crystalline structure (left) and A8 and A9′ in the solution structure (right). The double-arrow shows the proximity of H2(A9) and H2(A16).

Even though a weak part of the bulged out conformation may coexist in solution, our data show clearly that the majority conformation did not own extra adenines at pH 5.7. However, it can be pointed out that 1H-13C HSQC spectra showed that adenine A8 underwent a protonation–deprotonation equilibrium with an apparent pK of 6.4 in 3.3 mM MgCl2 for DIS23(Mal) (49). Besides, fluorescence studies and mutation on A8 indicated that the pH dependence of the NCp7-catalyzed DIS isomerization was correlated to the protonation state of A8 (49). Although it may be hazardous to deduct the behaviour of DIS23(Lai) from those of DIS23(Mal), because the transition toward the extended conformation can be easily induced by increasing the temperature for Lai (30) contrary to Mal (29), these data suggest that the ratio between bulged out and bulged in conformation for DIS23(Lai) should be different at physiological pH.

In order to explain the discrepancy in A8 and A9 conformation between the solution structure and the crystal structure we suggest that the crystallization process shifts the equilibrium between a bulged in and a bulged out conformation. The transition from a bulged in to a bulged out conformation generated a change in the position of the base from syn to anti for A8 and A9 as well as the conformation of the sugar from south to north for A8. This reversed the adenine positions and allowed the bulged out conformation (Figure 6). Further differences between the NMR and crystallographic studies emerge from addition of salt during sample preparation. Our sample was analyzed in the absence of salts whereas magnesium chloride was present in the mixture for crystallographic procedure. Addition of magnesium (1 ion for every 5 nt) on the ‘kissing complex’ structure did not change the NOESY spectrum, however it broadened the resonance lines. Increased magnesium concentrations caused precipitation prevented high-resolution NMR and bringing evidence of self-association.

Several results concerning the chemical probes support our structure: (i) chemical probes showed that N1(A8) is hyper reactive whereas N7(A8) is not (50). This added to the idea that N1 of A8 is not involved in a hydrogen bond and that N7 of A8 has limited accessibility to the chemical probes, (ii) methylation of N1 of the adenine bases A8, A9 and A16 did not impair dimerization in agreement with the fact that these three adenines are not paired, (iii) the three phosphates 5′-P(A8)-P(A9)-P-3′ may be ethylated without impairing dimerization. This region allows the ethylation without destroying the initial conformation.

In our structure, the unpaired adenines of A8, A9 and A16 had weaker interactions than those of the extended dimer where they formed a zipper like motif. Moreover weaker stacking was observed for the six central GC base pairs. These features would explain the state of ‘kissing complex’ as less thermostable than the linear duplex.

We have previously shown that the conformational change from ‘kissing complex’ to extended dimer (induced by an increase of the temperature) kept the six central base pairs GC paired during the transition (30). We suggest that increased temperature lead to the weakness of adenines A8, A9 and A16 interaction and the fading of G7-C17 pairing. The mechanism of this transition starts by distancing of A9 from A16, allowing an increase in the stacking of the central GC base pairs. The stems are less thermostable than the central mini double helix, because they comprise two AT and one wobble GU base pairs. Their melting may allow for molecular rearrangements from paired loops to extended duplex.

Our study provides a new structure of the SL1 HIV-1Lai loop–loop dimer. The next step in understanding the RNA dimerization is to solve the structure of the entire SL1 hairpin (51). This region contains a bulge of well-conserved residues. Mutations in the bulge cause defects in encapsidation (15). Antiretroviral therapy research has not yet targeted the process of dimerization of the viral RNA, thereby providing an avenue for future drug design strategies.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Laboratoire de RMN, Institut de Biologie Structurale in Grenoble, France, for running NMR spectra at 800 MHz. This work was supported by Agence Nationale de la Recherche sur le Sida grant (J.P.). F.K. was supported by a fellowship from the Ministère Français de l'Education Nationale, de la Recherche et de la Technologie. The Open Access publication charges for this article were waived by Oxford University Press.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Coffin J.M. Structure of the retroviral genome. In: Weiss R., Teich N., Varmus H., Coffin J., editors. Tumor Viruses. Vol. I. Cold Spring Harbor, New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1984. pp. 261–368. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hu W.S., Temin H.M. Genetic consequences of packaging two RNA genomes in one retroviral particle: pseudodiploidy and high rate of genetic recombination. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1990;87:1556–1560. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.4.1556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu W.S., Temin H.M. Retroviral recombination and reverse transcription. Science. 1990;250:1227–1233. doi: 10.1126/science.1700865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Panganiban A.T., Fiore D. Ordered interstrand and intrastrand DNA transfer during reverse transcription. Science. 1988;241:1064–1069. doi: 10.1126/science.2457948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stuhlmann H., Berg P. Homologous recombination of copackaged retrovirus RNAs during reverse transcription. J. Virol. 1992;66:2378–2388. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.4.2378-2388.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Temin H.M. Sex and recombination in retroviruses. Trends Genet. 1991;7:71–74. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(91)90272-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Temin H.M. Retrovirus variation and reverse transcription: abnormal strand transfers result in retrovirus genetic variation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:6900–6903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.15.6900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bender W., Davidson N. Mapping of poly(A) sequences in the electron microscope reveals unusual structure of type C oncornavirus RNA molecules. Cell. 1976;7:595–607. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(76)90210-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bender W., Chien Y.H., Chattopadhyay S., Vogt P.K., Gardner M.B., Davidson N. High-molecular-weight RNAs of AKR, NZB, and wild mouse viruses and avian reticuloendotheliosis virus all have similar dimer structures. J. Virol. 1978;25:888–896. doi: 10.1128/jvi.25.3.888-896.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoglund S., Ohagen A., Goncalves J., Panganiban A.T., Gabuzda D. Ultrastructure of HIV-1 genomic RNA. Virology. 1997;233:271–279. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chien Y.H., Junghans R.P., Davidson N. Electron Microscopic Analysis of the Structure of RNA Tumor Virus Nucleic Acids. NY: Academic Press; 1980. Molecular biology of RNA tumor viruses; pp. 395–446. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marquet R., Paillart J.C., Skripkin E., Ehresmann C., Ehresmann B. Dimerization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA involves sequences located upstream of the splice donor site. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:145–151. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.2.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Skripkin E., Paillart J.C., Marquet R., Ehresmann B., Ehresmann C. Identification of the primary site of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA dimerization in vitro. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:4945–4949. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.4945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bernacchi S., Mely Y. Exciton interaction in molecular beacons: a sensitive sensor for short range modifications of the nucleic acid structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:E62–E62. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.13.e62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clever J.L., Parslow T.G. Mutant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genomes with defects in RNA dimerization or encapsidation. J. Virol. 1997;71:3407–3414. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.5.3407-3414.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haddrick M., Lear A.L., Cann A.J., Heaphy S. Evidence that a kissing loop structure facilitates genomic RNA dimerisation in HIV-1. J. Mol. Biol. 1996;259:58–68. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laughrea M., Shen N., Jette L., Wainberg M.A. Variant effects of nonnative kissing-loop hairpin palindromes on HIV replication and HIV RNA dimerization: role of stem-loop B in HIV replication and HIV RNA dimerization. Biochemistry. 1999;38:226–234. doi: 10.1021/bi981728j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liang C., Rong L., Laughrea M., Kleiman L., Wainberg M.A. Compensatory point mutations in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag region that are distal from deletion mutations in the dimerization initiation site can restore viral replication. J. Virol. 1998;72:6629–6636. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.8.6629-6636.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McBride M.S., Schwartz M.D., Panganiban A.T. Efficient encapsidation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vectors and further characterization of cis elements required for encapsidation. J. Virol. 1997;71:4544–4554. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4544-4554.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paillart J.C., Skripkin E., Ehresmann B., Ehresmann C., Marquet R. A loop–loop “kissing” complex is the essential part of the dimer linkage of genomic HIV-1 RNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:5572–5577. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.11.5572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paillart J.C., Marquet R., Skripkin E., Ehresmann C., Ehresmann B. Dimerization of retroviral genomic RNAs: structural and functional implications. Biochimie. 1996;8:639–653. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(96)80010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shen N., Jette L., Liang C., Wainberg M.A., Laughrea M. Impact of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA dimerization on viral infectivity and of stem–loop B on RNA dimerization and reverse transcription and dissociation of dimerization from packaging. J. Virol. 2000;74:5729–5735. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.12.5729-5735.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muriaux D., Girard P.M., Bonnet-Mathoniere B., Paoletti J. Dimerization of HIV-1Lai RNA at low ionic strength. An autocomplementary sequence in the 5′ leader region is evidenced by an antisense oligonucleotide. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:8209–8216. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.14.8209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Windbichler N., Werner M., Schroeder R. Kissing complex-mediated dimerisation of HIV-1 RNA: coupling extended duplex formation to ribozyme cleavage. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:6419–6427. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laughrea M., Jette L. Kissing-loop model of HIV-1 genome dimerization: HIV-1 RNAs can assume alternative dimeric forms, and all sequences upstream or downstream of hairpin 248–271 are dispensable for dimer formation. Biochemistry. 1996;35:1589–1598. doi: 10.1021/bi951838f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laughrea M., Jette L. HIV-1 genome dimerization: formation kinetics and thermal stability of dimeric HIV-1Lai RNAs are not improved by the 1–232 and 296–790 regions flanking the kissing-loop domain. Biochemistry. 1996;35:9366–9374. doi: 10.1021/bi960395s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muriaux D., Fosse P., Paoletti J. A kissing complex together with a stable dimer is involved in the HIV-1Lai RNA dimerization process in vitro. Biochemistry. 1996;35:5075–5082. doi: 10.1021/bi952822s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takahashi K.I., Baba S., Chattopadhyay P., Koyanagi Y., Yamamoto N., Takaku H., Kawai G. Structural requirement for the two-step dimerization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genome. RNA. 2000;6:96–102. doi: 10.1017/s1355838200991635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rist M.J., Marino J.P. Mechanism of nucleocapsid protein catalyzed structural isomerization of the dimerization initiation site of HIV-1. Biochemistry. 2002;41:14762–14770. doi: 10.1021/bi0267240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Theilleux-Delalande V., Girard F., Huynh-Dinh T., Lancelot G., Paoletti J. The HIV-1(Lai) RNA dimerization. Thermodynamic parameters associated with the transition from the kissing complex to the extended dimer. Eur. J. Biochem. 2000;267:2711–2719. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mujeeb A., Clever J.L., Billeci T.M., James T.L., Parslow T.G. Structure of the dimer initiation complex of HIV-1 genomic RNA. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1998;5:432–436. doi: 10.1038/nsb0698-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ennifar E., Walter P., Ehresmann B., Ehresmann C., Dumas P. Crystal structures of coaxially stacked kissing complexes of the HIV-1 RNA dimerization initiation site. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2001;8:1064–1068. doi: 10.1038/nsb727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Milligan J.F., Groebe D.R., Witherell G.W., Uhlenbeck O.C. Oligoribonucleotide synthesis using T7 RNA polymerase and synthetic DNA templates. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:8783–8798. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.21.8783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davanloo P., Rosenberg A.H., Dunn J.J., Studier F.W. Cloning and expression of the gene for bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1984;81:2035–2039. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.7.2035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lapham J., Rife P.B., Moore J.P., Crothers D.M. Measurement of diffusion constants for nucleic acids by NMR. J. Biomol. NMR. 1997;10:255–262. doi: 10.1023/a:1018310702909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stallings S.C., Moore P.B. The structure of an essential splicing element: stem loop IIa from yeast U2 snRNA. Structure. 1997;5:1173–1185. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(97)00268-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brünger A.T., Adams P.D., Clore G.M., De Lano W.L., Gros P., Grosse-Kunstleve R.W., Jiang J.S., Kuszewski J., Nilges M., Pannu N.S., et al. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallog. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koradi R., Billeter M., Wuthrich K. MOLMOL: a program for display and analysis of macromolecular structures. J. Mol. Graphics. 1996;14:51–55. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00009-4. 29–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lavery R., Sklenar H. Defining the structure of irregular nucleic acids: conventions and principles. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 1989;6:655–667. doi: 10.1080/07391102.1989.10507728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lavery R., Sklenar H. The definition of generalized helicoidal parameters and of axis curvature for irregular nucleic acids. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 1988;6:63–91. doi: 10.1080/07391102.1988.10506483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nikonowicz E.P., Pardi A. An efficient procedure for assignment of the proton, carbon and nitrogen resonances in 13C/15N labeled nucleic acids. J. Mol. Biol. 1993;232:1141–1156. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dingley A.J., Grzesiek S. Direct observation of Hydrogen bonds in nucleic acid base pairs by internucleotide 2JNN Couplings. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:8293–8297. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sklenar V., Peterson R.D., Rejante M.R., Feigon J. Two- and three-dimensional HCN experiments for correlating base and sugar resonances in 15N,13C-labeled RNA oligonucleotides. J. Biomol. NMR. 1993;3:721–727. doi: 10.1007/BF00198375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Dongen M.J., Wijmenga S.S., Eritja R., Azorin F., Hilbers C.W. Through-bond correlation of adenine H2 and H8 protons in unlabeled DNA fragments by HMBC spectroscopy. J. Biomol. NMR. 1996;8:207–212. doi: 10.1007/BF00211166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Girard F., Barbault F., Gouyette C., Huynh-Dinh T., Paoletti J., Lancelot G. Dimer initiation sequence of HIV-1Lai genomic RNA: NMR solution structure of the extended duplex. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 1999;16:1145–1157. doi: 10.1080/07391102.1999.10508323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kieken F., Arnoult E., Barbault F., Paquet F., Huynh-Dinh T., Paoletti J., Genest D., Lancelot G. HIV-1(Lai) genomic RNA: combined used of NMR and molecular dynamics simulation for studying the structure and internal dynamics of a mutated SL1 hairpin. Eur. Biophys. J. 2002;31:521–531. doi: 10.1007/s00249-002-0251-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Slijper M., Kaptein R., Boelens R. Simultaneous 13C and 15N isotope editing of biomolecular complexes. Application to a mutant lac repressor headpiece DNA complex. J. Magn. Reson. B. 1996;111:199–203. doi: 10.1006/jmrb.1996.0083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Otting G., Senn H., Wagner G., Wüthrich K. Editing of 2D 1H NMR spectra using X half-filters. combined use with residue-selective 15N labeling of proteins. J. Magn. Reson. 1986;70:500–505. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mihailescu M.R., Marino J.P. A proton-coupled dynamic conformational switch in the HIV-1 dimerization initiation site kissing complex. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:1189–1194. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307966100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Paillart J.C., Westhof E., Ehresmann C., Ehresmann B., Marquet R. Non-canonical interactions in a kissing loop complex: the dimerization initiation site of HIV-1 genomic RNA. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;270:36–49. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kuiken C., Thakallapalli R., Esklid A., de Ronde A. Genetic analysis reveals epidemiologic patterns in the spread of human immunodeficiency virus. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2000;152:814–822. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.9.814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]