Abstract

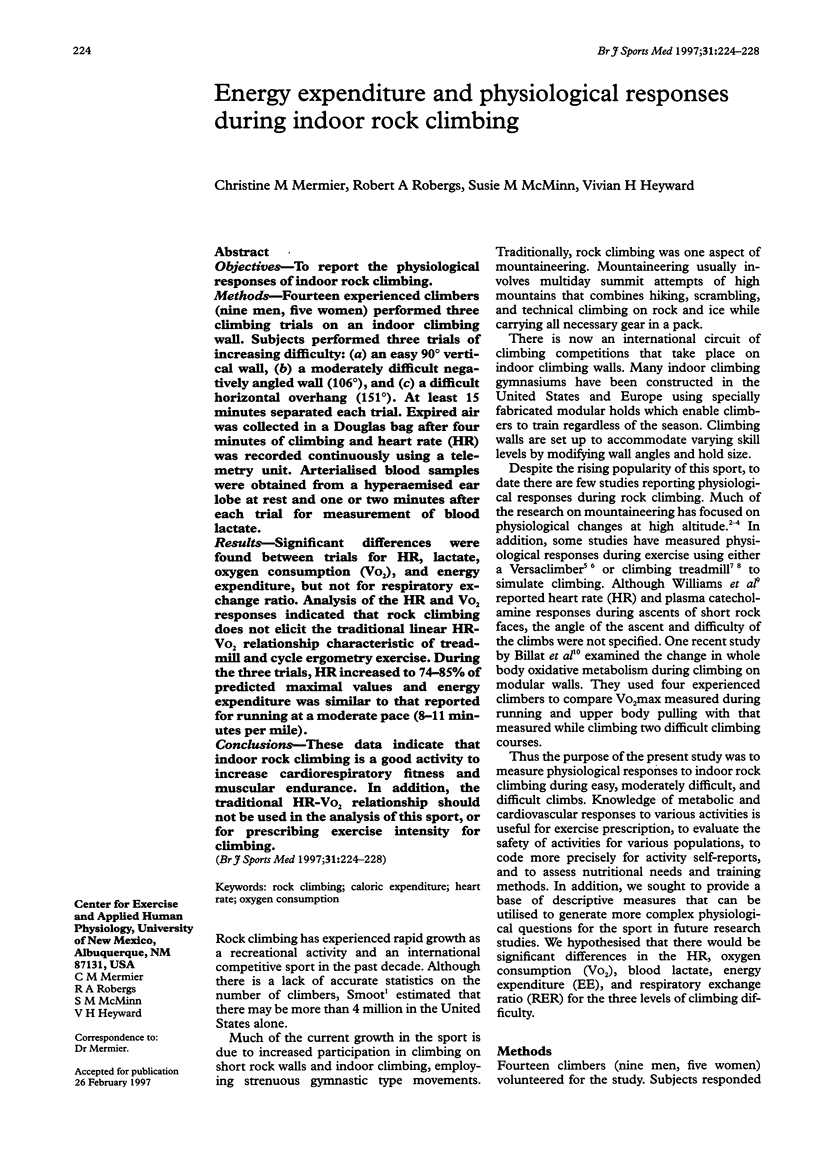

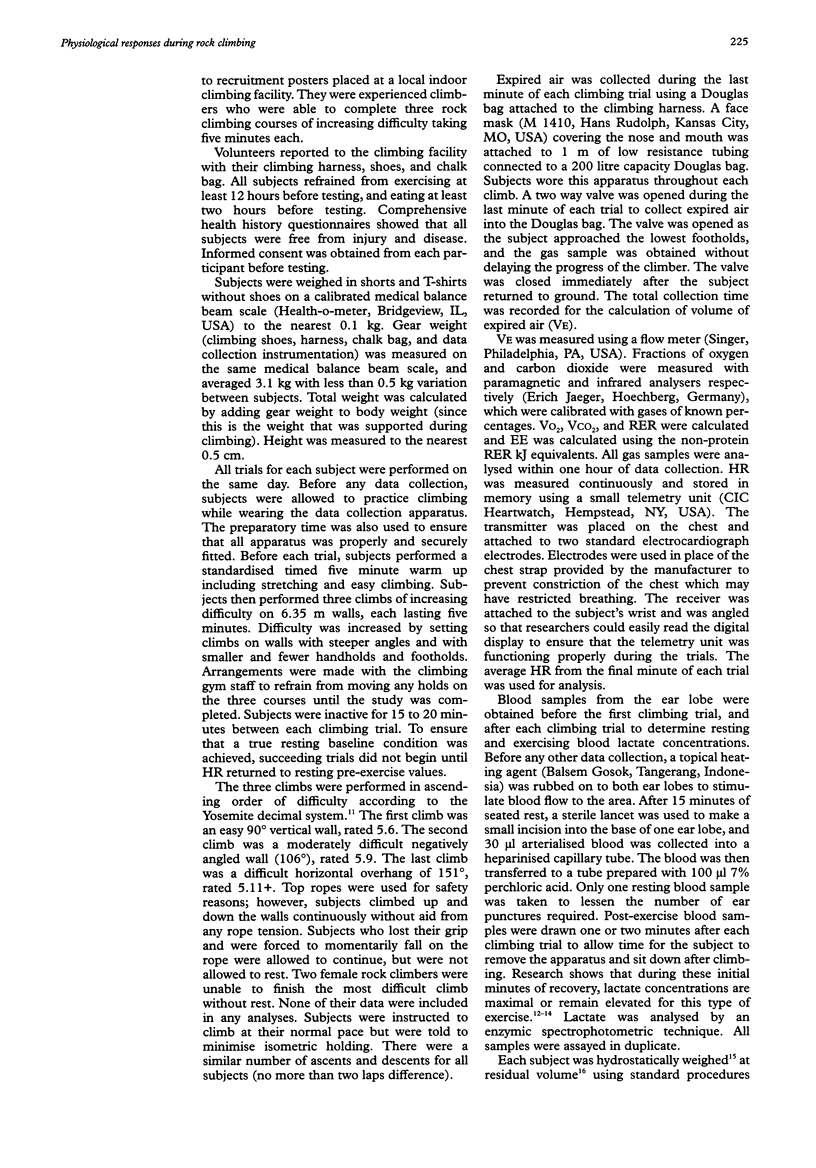

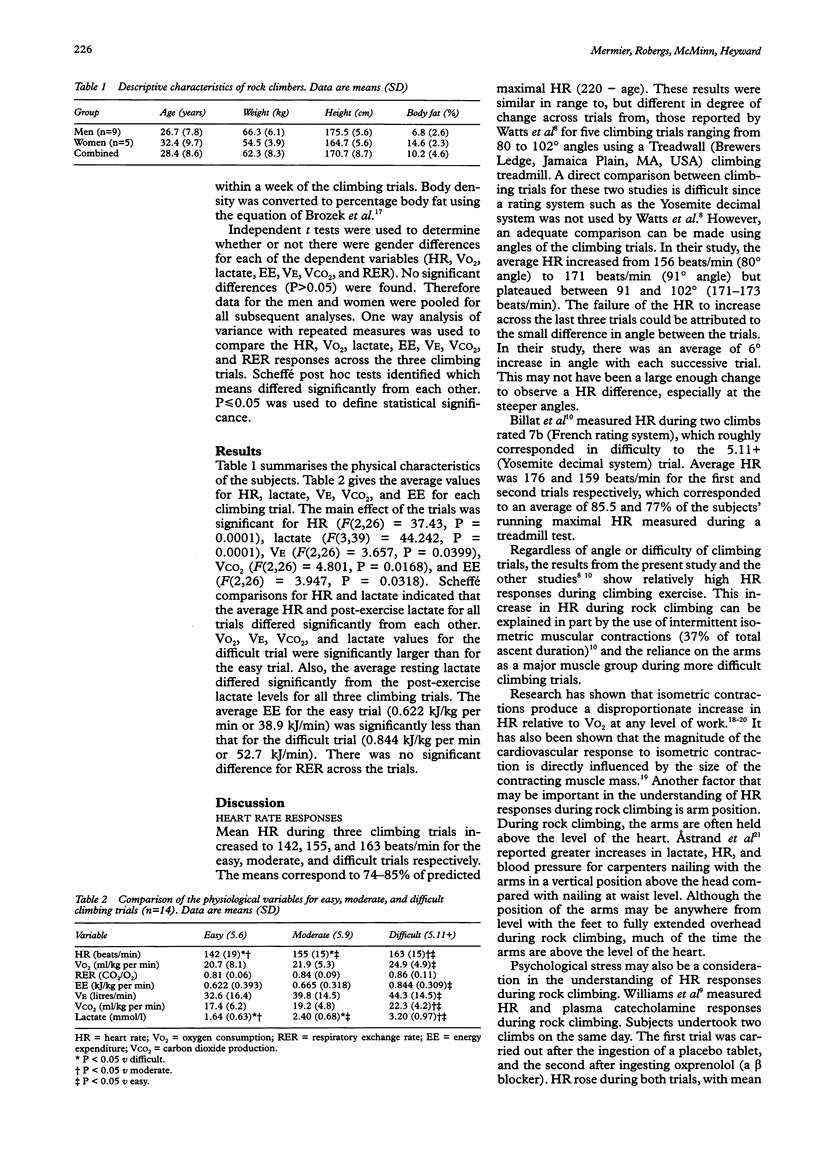

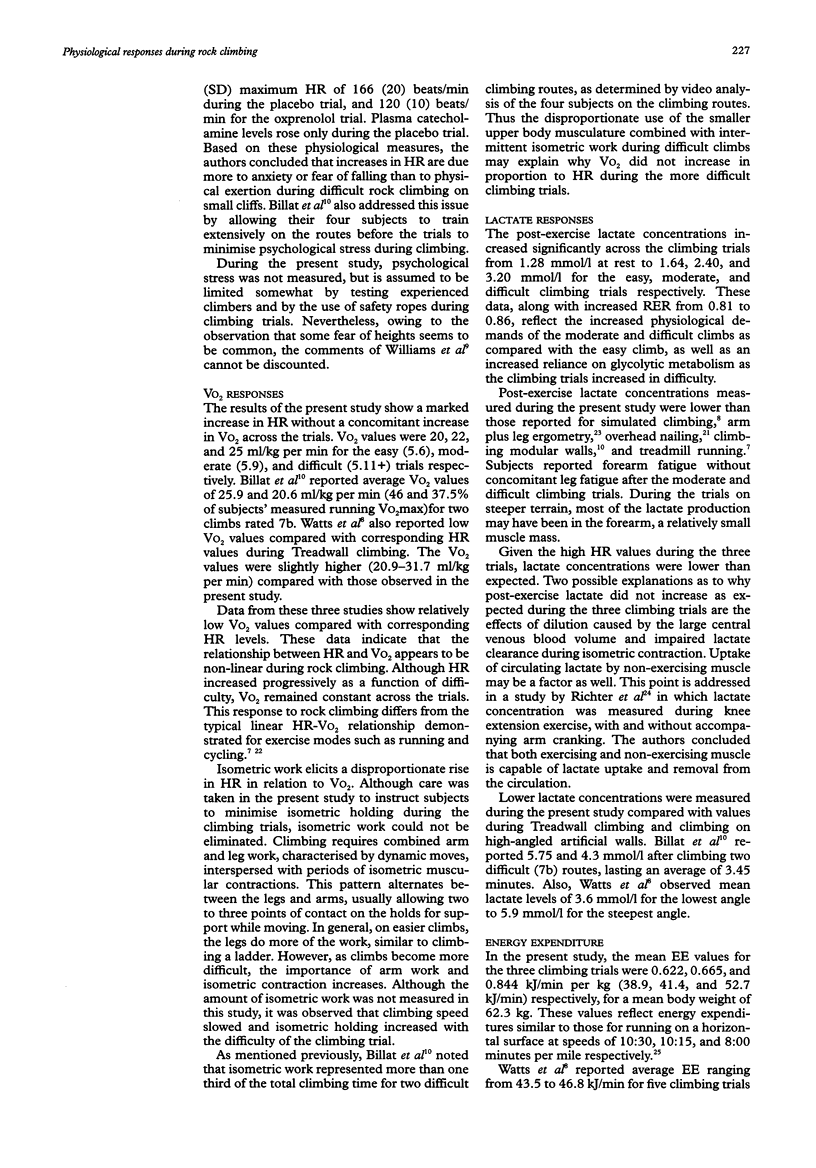

OBJECTIVES: To report the physiological responses of indoor rock climbing. METHODS: Fourteen experienced climbers (nine men, five women) performed three climbing trials on an indoor climbing wall. Subjects performed three trials of increasing difficulty: (a) an easy 90 degrees vertical wall, (b) a moderately difficult negatively angled wall (106 degrees), and (c) a difficult horizontal overhang (151 degrees). At least 15 minutes separated each trial. Expired air was collected in a Douglas bag after four minutes of climbing and heart rate (HR) was recorded continuously using a telemetry unit. Arterialised blood samples were obtained from a hyperaemised ear lobe at rest and one or two minutes after each trial for measurement of blood lactate. RESULTS: Significant differences were found between trials for HR, lactate, oxygen consumption (VO2), and energy expenditure, but not for respiratory exchange ratio. Analysis of the HR and VO2 responses indicated that rock climbing does not elicit the traditional linear HR-VO2 relationship characteristic of treadmill and cycle ergometry exercise. During the three trials, HR increased to 74-85% of predicted maximal values and energy expenditure was similar to that reported for running at a moderate pace (8-11 minutes per mile). CONCLUSIONS: These data indicate that indoor rock climbing is a good activity to increase cardiorespiratory fitness and muscular endurance. In addition, the traditional HR-VO2 relationship should not be used in the analysis of this sport, or for prescribing exercise intensity for climbing.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Astrand I., Guharay A., Wahren J. Circulatory responses to arm exercise with different arm positions. J Appl Physiol. 1968 Nov;25(5):528–532. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1968.25.5.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belcastro A. N., Bonen A. Lactic acid removal rates during controlled and uncontrolled recovery exercise. J Appl Physiol. 1975 Dec;39(6):932–936. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1975.39.6.932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonge D., Donnelly J. E. Trials to criteria for hydrostatic weighing at residual volume. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1989 Jun;60(2):176–179. doi: 10.1080/02701367.1989.10607433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brahler C. J., Blank S. E. VersaClimbing elicits higher VO2max than does treadmill running or rowing ergometry. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1995 Feb;27(2):249–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodd S., Powers S. K., Callender T., Brooks E. Blood lactate disappearance at various intensities of recovery exercise. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol. 1984 Nov;57(5):1462–1465. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1984.57.5.1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIND A. R., TAYLOR S. H., HUMPHREYS P. W., KENNELLY B. M., DONALD K. W. THE CIRCULATIORY EFFECTS OF SUSTAINED VOLUNTARY MUSCLE CONTRACTION. Clin Sci. 1964 Oct;27:229–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOTLEY H. L. Comparison of a simple helium closed with the oxygen open-circuit method for measuring residual air. Am Rev Tuberc. 1957 Oct;76(4):601–615. doi: 10.1164/artpd.1957.76.4.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oelz O., Howald H., Di Prampero P. E., Hoppeler H., Claassen H., Jenni R., Bühlmann A., Ferretti G., Brückner J. C., Veicsteinas A. Physiological profile of world-class high-altitude climbers. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1986 May;60(5):1734–1742. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1986.60.5.1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PASSMORE R., DURNIN J. V. Human energy expenditure. Physiol Rev. 1955 Oct;35(4):801–840. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1955.35.4.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seals D. R., Washburn R. A., Hanson P. G., Painter P. L., Nagle F. J. Increased cardiovascular response to static contraction of larger muscle groups. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol. 1983 Feb;54(2):434–437. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1983.54.2.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Secher N. H., Ruberg-Larsen N., Binkhorst R. A., Bonde-Petersen F. Maximal oxygen uptake during arm cranking and combined arm plus leg exercise. J Appl Physiol. 1974 May;36(5):515–518. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1974.36.5.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts P. B., Martin D. T., Schmeling M. H., Silta B. C., Watts A. G. Exertional intensities and energy requirements of technical mountaineering at moderate altitude. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 1990 Dec;30(4):365–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams E. S., Taggart P., Carruthers M. Rock climbing: observations on heart rate and plasma catecholamine concentrations and the influence of oxprenolol. Br J Sports Med. 1978 Sep;12(3):125–128. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.12.3.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyndham C. H. Submaximal tests for estimating maximum oxygen intake. Can Med Assoc J. 1967 Mar 25;96(12):736–745. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]