Abstract

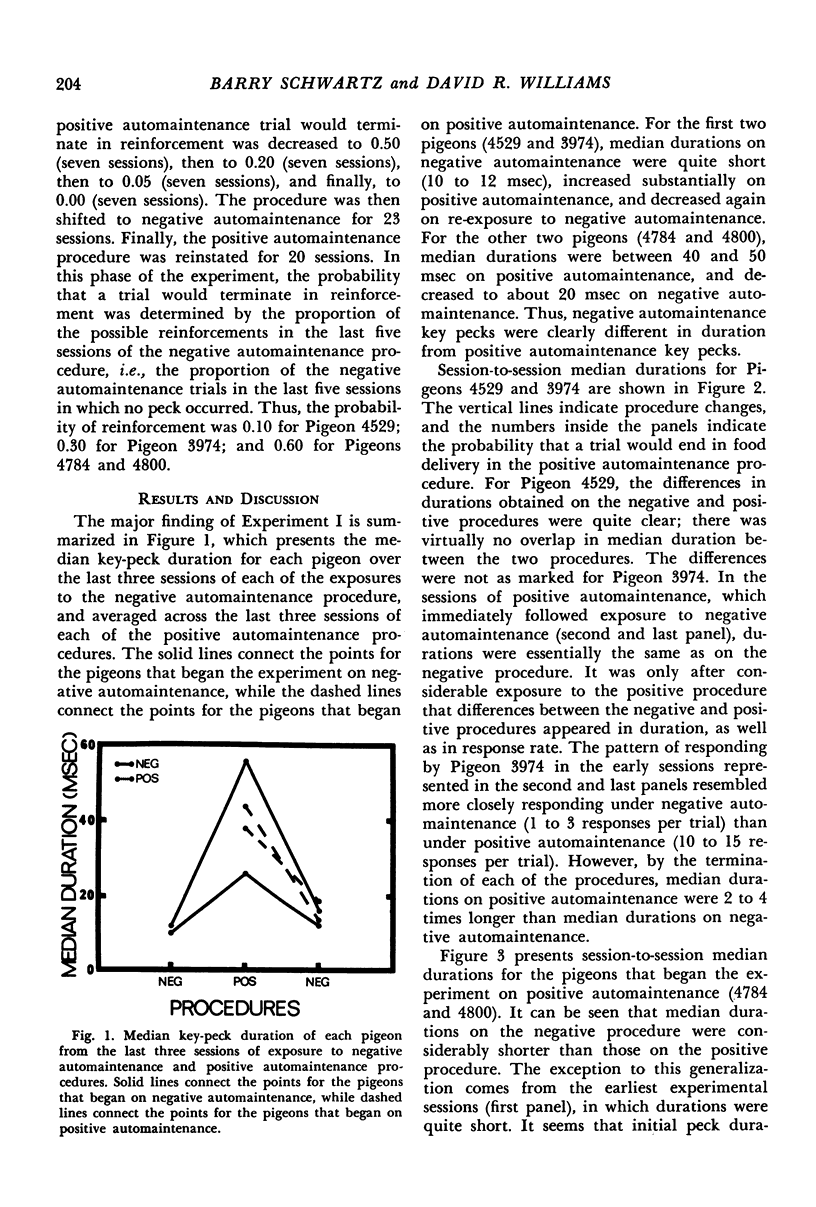

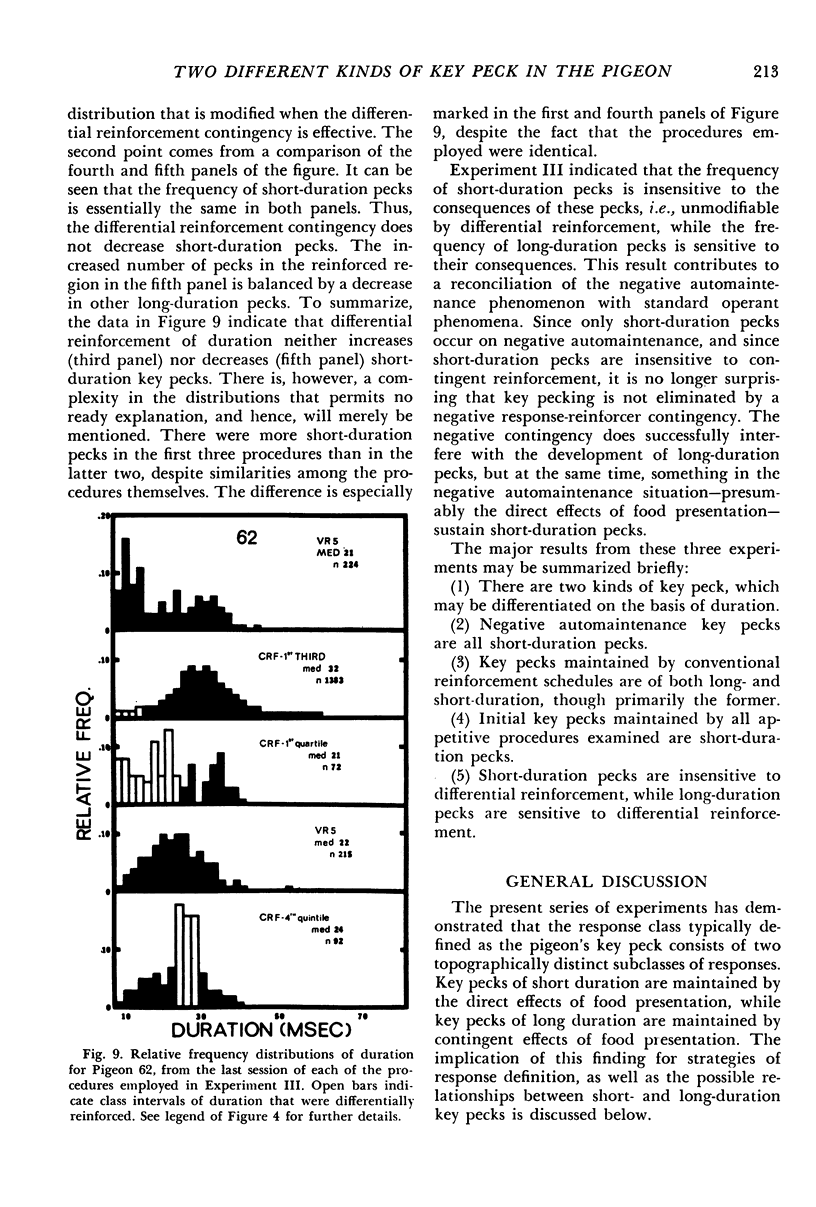

Pigeons emitted almost exclusively short-duration key pecks (shorter than 20 msec) when on negative automaintenance procedures, in which pecks prevented reinforcement. Peck durations under fixed-interval and fixed-ratio reinforcement schedules were generally two to five times longer than pecks under a negative automaintenance schedule. However, initial key pecks were of short duration, independent of procedure. The frequency of short-duration pecks was insensitive to differential reinforcement, while the frequency of long-duration pecks was sensitive to differential reinforcement. It is proposed that short-duration pecks arise from the pigeon's normal feeding pattern and are directly enhanced by food presentation, while long-duration pecks are controlled by the contingent effects of food presentation. The implications of the existence of two classes of pecks for the functional definition of operants and the separation of phylogenetic and ontogenetic sources of control of key pecking are discussed.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Blough D. S. Interresponse time as a function of continuous variables: a new method and some data. J Exp Anal Behav. 1963 Apr;6(2):237–246. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1963.6-237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown P. L., Jenkins H. M. Auto-shaping of the pigeon's key-peck. J Exp Anal Behav. 1968 Jan;11(1):1–8. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1968.11-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOFFMAN H. S., FLESHLER M. Aversive control with the pigeon. J Exp Anal Behav. 1959 Jul;2:213–218. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1959.2-213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller N. E., Carmona A. Modification of a visceral response, salivation in thirsty dogs, by instrumental training with water reward. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1967 Feb;63(1):1–6. doi: 10.1037/h0024170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachlin H. Autoshaping of key pecking in pigeons with negative reinforcement. J Exp Anal Behav. 1969 Jul;12(4):521–531. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1969.12-521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachlin H., Hineline P. N. Training and maintenance of keypecking in the pigeon by negative reinforcement. Science. 1967 Aug 25;157(3791):954–955. doi: 10.1126/science.157.3791.954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schick K. Operants. J Exp Anal Behav. 1971 May;15(3):413–423. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1971.15-413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz B., Williams D. R. The role of the response-reinforcer contingency in negative automaintenance. J Exp Anal Behav. 1972 May;17(3):351–357. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1972.17-351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner B. F. The phylogeny and ontogeny of behavior. Contingencies of reinforcement throw light on contingencies of survival in the evolution of behavior. Science. 1966 Sep 9;153(3741):1205–1213. doi: 10.1126/science.153.3741.1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. R., Williams H. Auto-maintenance in the pigeon: sustained pecking despite contingent non-reinforcement. J Exp Anal Behav. 1969 Jul;12(4):511–520. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1969.12-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]