Abstract

Keratinocyte growth factor (KGF) is a potent mitogen for epithelial cells, and it promotes survival of these cells under stress conditions. In a search for KGF-regulated genes in keratinocytes, we identified the gene encoding the transcription factor NF-E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2). Nrf2 is a key player in the cellular stress response. This might be of particular importance during wound healing, where large amounts of reactive oxygen species are produced as a defense against invading bacteria. Therefore, we studied the wound repair process in Nrf2 knockout mice. Interestingly, the expression of various key players involved in wound healing was significantly reduced in early wounds of the Nrf2 knockout animals, and the late phase of repair was characterized by prolonged inflammation. However, these differences in gene expression were not reflected by obvious histological abnormalities. The normal healing rate appears to be at least partially due to an up-regulation of the related transcription factor Nrf3, which was also identified as a target of KGF and which was coexpressed with Nrf2 in the healing skin wound. Taken together, our results reveal novel roles of the KGF-regulated transcription factors Nrf2 and possibly Nrf3 in the control of gene expression and inflammation during cutaneous wound repair.

Injury to adult tissues initiates a series of events, including inflammation, new tissue formation, and matrix remodeling, which finally lead to at least partial reconstruction of the wounded tissue. During the early inflammatory phase, neutrophils and macrophages are attracted to the wound. Their influx is beneficial, since they attack contaminating bacteria, e.g., by release of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (reviewed in references 11 and 34). However, prolonged production of high levels of ROS can cause severe tissue damage and DNA mutations. Therefore, cells in injured and inflamed tissues must be able to protect themselves against ROS toxicity.

A series of studies revealed a potent cytoprotective effect of keratinocyte growth factor (KGF) on different types of epithelial cells (reviewed in reference 49). KGF (fibroblast growth factor 7 [FGF7]) is a member of the FGF family which is predominantly produced by mesenchymal cells and acts specifically on epithelial cells via binding to its high-affinity receptor, a splice variant of FGF receptor 2 (FGFR2-IIIb; reviewed in reference 40). KGF expression is strongly increased in injured and inflamed tissues, including wounded skin (31, 46, 49). This upregulation is likely to be important for the repair process, since transgenic mice, which express a dominant-negative FGFR2-IIIb in the epidermis showed inhibition of wound reepithelialization (48). However, mice lacking KGF had no significant wound healing phenotype (19), suggesting the presence of other FGFR2-IIIb ligands, which can compensate for the lack of KGF. The most likely candidate is FGF10, which is also expressed in wounded skin and which binds to FGFR2-IIIb with high affinity (1, 23).

The cytoprotective effect of KGF has been suggested to be at least partially achieved by an increase in the expression of genes encoding ROS-detoxifying enzymes (reviewed in reference 49). In this study we identified Nrf2 as a novel target of KGF action in keratinocytes. Nrf2 is a member of the “cap’n’ collar” family of transcription factors (35), which also includes NF-E2, Nrf1, Nrf3, Bach1, and Bach2 (5, 6, 29, 38). These proteins do not homo- or heterodimerize with each other but require other leucine zipper proteins, such as small Maf proteins, Jun proteins, or c-Fos, for activity (28, 33, 43, 44). Together with these interaction partners, Nrf1 and Nrf2 bind to cis-acting elements in the promoters of target genes, called antioxidant response element (ARE) (42) or electrophile response element (17). Interestingly, these target genes encode a series of cytoprotective proteins, including NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase (43), glutathione S-transferase Ya subunit (GST-Ya) (41), γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase (36), and heme oxygenase 1 (HO1) (39). Furthermore, expression of genes encoding the detoxifying enzymes catalase and superoxide dismutase 1 is reduced in Nrf2 knockout mice, suggesting that they are also targets of Nrf2 (8).

The important role of Nrf2 in the regulation of protective genes and thus in the cellular stress response is also reflected by the phenotype of Nrf2 knockout mice. These animals have no obvious phenotype under normal laboratory conditions (7). However, induction of phase II detoxifying enzymes by a phenolic antioxidant was strongly reduced in the liver and intestine of the knockout mice (25). Most interestingly, these mice were extremely susceptible to the administration of the antioxidant butylated hydroxytoluene, which caused death in these animals from acute respiratory distress syndrome (8). Nrf2 knockout mice are also highly sensitive to acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity, mostly due to the depletion and impaired de novo synthesis of glutathione (9, 13). Considering these remarkable findings, it seemed particularly interesting to determine a potential role of Nrf2 in the protection of cells against oxidative stress during cutaneous wound repair. Therefore, we used Nrf2 knockout mice to investigate whether the lack of this transcription factor influences the wound healing process.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

The human keratinocyte cell line HaCaT (3) was cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 100 U of penicillin/ml, and 100 μg of streptomycin/ml. Cells were grown to confluence without changing the medium, rendered quiescent by a 16- to 20-h incubation in serum-free DMEM, and subsequently incubated in fresh DMEM containing purified KGF (10 ng/ml of medium), FGF10 (10 ng/ml), or epidermal growth factor (EGF) (20 ng/ml of medium). They were harvested before and at different time points after growth factor addition and used for RNA isolation or preparation of cell lysates. DMEM was purchased from Sigma, FCS was purchased from Amimed-BioConcept (Allschwil, Switzerland), and KGF, FGF10, and EGF were purchased from Roche (Basel, Switzerland) or R&D Systems (Minneapolis, Minn.).

Animals.

Mice with a disrupted Nrf2 gene were described previously (7). BALB/c mice were obtained from RCC (Füllinsdorf, Switzerland). Mice were housed and fed according to federal guidelines, and all procedures were approved by the local authorities.

Wounding and preparation of wound tissue.

Mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of 100 μl of ketamine (10 g/liter)-xylazine (8 g/liter). Two full-thickness excisional wounds, 5 mm in diameter, were made on either side of the dorsal midline by excising skin and panniculus carnosus as described by Werner et al. (48). Wounds were left uncovered and harvested 1, 5, or 13 days after injury. For expression analyses, the complete wounds including 2 mm of the epithelial margins were excised and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. Nonwounded back skin served as a control. For histological analyses the complete wounds were isolated, bisected, fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and embedded in paraffin. Sections (7 μm) from the middle of the wound were stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H/E) or Masson trichrome. Only littermates of the same sex were used for direct histological comparison.

RNA isolation and RNase protection assay.

RNA isolation and the RNase protection assay were performed as described by Chomczynski and Sacchi (10) and by Werner et al. (47), respectively. All protection assays were carried out at least in duplicate with different sets of RNA from independent wounding experiments. The following templates were generated by reverse transcription-PCR and cloned: Nrf1 cDNA fragments (nucleotides [nt] 2726 to 3010 of the human cDNA [accession no. L24123] and nt 1837 to 2123 of the murine cDNA [accession no. X78709]), Nrf2 cDNA fragments (nt 1496 to 1743 of the human cDNA [accession no. S74017] and nt 988 to 1210 of the murine cDNA [accession no. U20532]), Nrf3 cDNA fragments (nt 1181 to 1477 of the human cDNA [accession no. AF133059] and nt 1337 to 1638 of the murine cDNA [accession no. NM_010903]), a murine Keap1 cDNA fragment (nt 425 to 691 of the cDNA [accession no. AB020063]), a fragment of the murine GST-Ya cDNA (nt 160 to 436 of the cDNA [accession no. NM_008181]), and a murine IL-6 cDNA fragment (nt 1477 to 1723 of the cDNA [accession no. M20572]). Other templates were described previously: murine IL-1β and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) (22), murine fibronectin, collagen α1 (I) and α1 (III) (2), murine TGFβ1 and β3 (16), murine vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (15), and murine HO1 (20). As a loading control, either 1 μg of the RNA samples was loaded on a 1% agarose gel prior to hybridization and stained with ethidium bromide or the RNA was hybridized with a probe for a housekeeping gene, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (nt 566 to 685 of the cDNA [accession no. NM_008084]). Quantification of the mRNA levels was performed with the National Institutes of Health image program.

In situ hybridization.

Antisense and sense riboprobes were generated by in vitro transcription using 35S-labeled UTP (1,000 Ci/mmol) and the Nrf1, Nrf2, and Nrf3 templates described above. Paraformaldehyde-fixed frozen sections (7 μm) from the middle of the wound were hybridized as described by Wilkinson et al. (50). After hybridization, sections were coated with NTB2 nuclear emulsion (Kodak), exposed in the dark at 4°C for 3 to 4 weeks, developed, counterstained with H/E, and mounted.

Preparation of HaCaT and skin lysates.

HaCaT cells were lysed by adding 500 μl (per 10-cm dish) of lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100, 137 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 0.15 U of aprotinin/ml, 1% leupeptin, 1% pepstatin, 1 mM Na2P2O7, 1 mM Na3VO4). After a 10-min incubation at 4°C on a rocker, cells were scraped off the dish and the lysates were sonicated. Preparation of tissue lysates from normal and wounded skin was performed as described previously (47). Alternatively, protein lysates were prepared under denaturing conditions in urea buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 9.5 M urea, 2 mM EDTA, 2 mM PMSF, 1 mM dithiothreitol).

Western blot analysis.

Proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose filters. Antibody incubations were performed in 5% nonfat dry milk in TBS-T (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20). The following antibodies were used: anti-Nrf1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. [La Jolla, Calif], diluted 1:200), anti-HO1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., diluted 1:100), and anti-interleukin 1 beta (anti-IL-1β) (Chemicon International, Inc. [Temecula, Calif.], diluted 1:500). The Nrf2 antibody (dilution, 1:1,000) was raised in rabbits against a GST-Nrf2 fusion protein. This immunization protein contains the GST protein from Schistosoma japonicum fused to the 189 C-terminal amino acids of the human Nrf2 protein (amino acids 401 to 589). The fusion protein was expressed from the pGEX2T vector (Amersham-Pharmacia). For affinity purification, the fusion protein used for immunization was coupled to N-hydroxysuccinimide-activated Sepharose and the crude serum was purified by column chromatography.

To demonstrate that the antibodies specifically recognize Nrf1 and Nrf2, respectively, they were incubated overnight at 4°C with a fivefold (by weight) excess of the immunization peptide (Nrf1) or protein (Nrf2). As a control, the antibodies were also incubated with the same amount of bovine serum albumin (BSA).

Immunofluorescence.

Wounds were fixed overnight in 95% ethanol-1% acetic acid and paraffin embedded. Sections (7 μm) from the middle of the wounds were incubated overnight at 4°C with rat antibodies directed against PECAM (Pharmingen, San Diego, Calif.) (diluted 1:100 in PBS containing 1% BSA and 0.2% Tween 20), Ly6G (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, Pa.) (diluted 1:125), or F4/80 (Serotec, Oxford, United Kingdom) (diluted 1:125). After three 10-min washes with PBS-0.2% Tween 20, sections were incubated for 1 h with anti-rat IgG-Cy3 (Jackson ImmunoResearch) (diluted 1:100), rinsed with PBS-0.2% Tween 20, mounted with Mowiol (Hoechst, Frankfurt, Germany), and photographed with a Zeiss Axioplan fluorescence microscope.

Detection of proliferating cells by labeling with 5′-bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU).

Mice were injected intraperitoneally with BrdU (Sigma, 250 mg/kg in 0.9% NaCl) and sacrificed 2 h after injection. Bisected wounds were fixed overnight at 4°C in 95% ethanol-1% acetic acid and embedded in paraffin. Sections (7 μm) were incubated overnight at 4°C with a peroxidase-conjugated monoclonal antibody directed against BrdU (Roche Diagnostics Ltd., Rotkreuz, Switzerland) (diluted 1:2) and stained with the diaminobenzidine-peroxidase substrate kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, Calif.). Counterstaining was performed with hematoxylin.

IL-1β ELISA.

Protein lysates from intact and wounded skin were prepared as described previously (47). IL-1β protein content was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Establishment of primary mouse keratinocytes, menadione treatment, and transfection with morpholino oligonucleotides.

Murine epidermal keratinocytes were isolated from pools of Nrf2 knockout mice and control littermates, respectively, as described by Caldelari et al., (4), with the exception that 3-day-old mice were used instead of E17.5 embryos and that cells were seeded at a density of 105 cells per cm2. For each experiment, keratinocytes were freshly isolated, grown to confluence in defined keratinocyte serum-free medium (Gibco, BRL) supplemented with 10 ng of EGF/ml and 10−10 M cholera toxin, and rendered quiescent by incubation in defined keratinocyte serum-free basal medium without growth supplements, EGF, and cholera toxin. Subsequently, 25 μM menadione was added to the medium and the cells were harvested before menadione addition and 1 and 3 h later. The delivery of morpholino oligonucleotides (Nrf3: 5′-AGC TTC ATC TCC CAC GGT GCG CCG-3′; control: 5′-CCT CTT ACC TCA GTT ACA ATT TAT A-3′) to primary keratinocytes was carried out according to the manufacturer"s instructions (special delivery protocol; Gene Tools, LLC). Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were treated for 3 h with menadione and subsequently used for RNA isolation.

RESULTS

Nrf2 is a novel target of KGF.

To gain insight into the mechanisms of KGF action, we searched for KGF-regulated genes by analyzing a subtractive cDNA library of quiescent and KGF-stimulated HaCaT keratinocytes (18). One of the clones we obtained included a fragment of the Nrf2 cDNA. To confirm the KGF-regulated expression, we performed RNase protection assays with RNAs from quiescent and KGF-treated HaCaT cells. As shown in Fig. 1A, Nrf2 mRNA levels increased two- to threefold within 3 h after addition of KGF. A similar regulation was also observed after stimulation of HaCaT cells with FGF10 or with EGF (data not shown). By contrast, Nrf1 mRNA levels were not altered in HaCaT keratinocytes after treatment with either KGF (Fig. 1A) or EGF (data not shown).

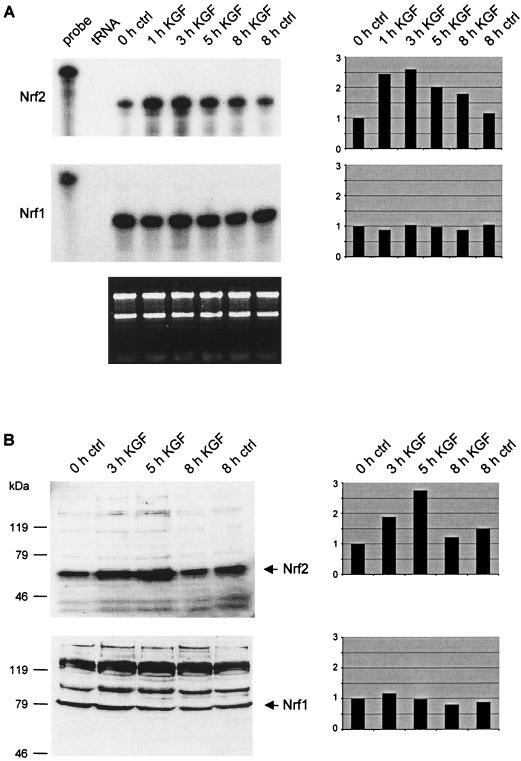

FIG. 1.

KGF induces expression of Nrf2 in HaCaT keratinocytes. Cells were rendered quiescent by serum starvation and treated with KGF as described in Materials and Methods. (A) RNase protection assays were performed with total cellular RNA (10 μg) from quiescent and KGF-treated cells to analyze the Nrf2 (upper panel) and Nrf1 (middle panel) mRNA levels. tRNA (50 μg) was used as a negative control. The hybridization probes (1,000 cpm) were loaded in the lanes labeled “probe” and used as size markers. One microgram of each RNA sample was loaded on a 1% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide (bottom panel). (B) Western blot analyses of lysates (50 μg) from quiescent and KGF-stimulated HaCaT cells for the presence of Nrf2 (top panel) and Nrf1 (bottom panel). Densitometric quantification of each RNase protection assay and Western blot is shown on the right-hand side. The signal intensities of nontreated keratinocytes were arbitrarily set as 1.

The KGF regulation of Nrf2 was confirmed on the protein level by Western blot analysis of cell lysates from KGF-treated cells. A two- to threefold up-regulation of the Nrf2 protein (65 kDa) occurred after 5 h of KGF treatment. Membranes with the same lysates were also probed with an Nrf1 antibody (Fig. 1B). In agreement with the mRNA data, no KGF regulation of the Nrf1 protein (81 kDa) was detected. The specificity of the bands was confirmed by Western blot analyses with antibodies that had been pretreated with the immunization peptide (Nrf1) or with the fusion protein used for immunization (Nrf2). In these cases, no signals were obtained (data not shown).

Nrf2 expression is up-regulated after skin injury.

To determine whether the observed KGF-induced expression of Nrf2 in vitro might be physiologically relevant, we analyzed the expression of Nrf2 under conditions where high levels of KGF are present, such as cutaneous wound repair. RNase protection assays with RNAs from nonwounded skin and from full-thickness excisional wounds at different stages of the healing process revealed that Nrf2 mRNA levels increased within 1 day after injury. Expression subsequently declined slowly to reach the expression level of unwounded skin at day 13 after wounding (Fig. 2). Consistent with the lack of KGF inducibility, expression of Nrf1 was not altered after skin injury (Fig. 2).

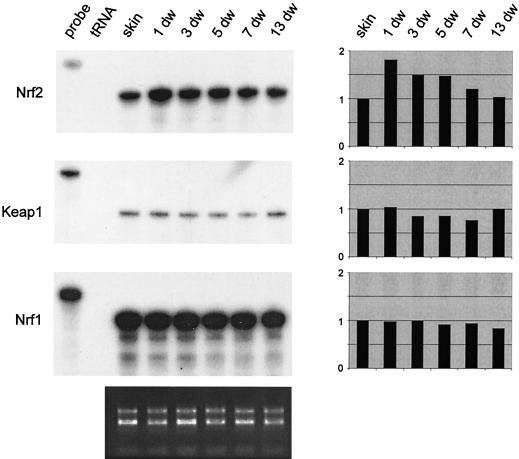

FIG. 2.

Increased expression of Nrf2 after skin injury. Mice were wounded and sacrificed at different time points (e.g., 1-day wound ([1 dw]) after injury as described in Materials and Methods. Twenty micrograms of total cellular RNA from normal and wounded skin was analyzed by RNase protection assay for the expression of Nrf2, Keap1, and Nrf1. For an explanation of lanes labeled “probe” and “tRNA,” see the legend to Fig. 1. Ethidium bromide-stained 1% agarose gel loaded with each RNA sample (1 μg) served as a loading control (shown below the protection assays). Densitometric quantification of each RNase protection assay is shown on the right-hand side. The signal intensities of unwounded skin were arbitrarily set as 1.

The activity of Nrf2 was shown to be regulated by Keap1, a cytosolic protein that retains Nrf2 in this compartment of the cell and thereby inhibits its function as a transcriptional activator (26). The expression of Keap1, however, was not altered after wounding (Fig. 2).

Nrf2 is predominantly expressed in the keratinocytes of the hyperproliferative wound epithelium.

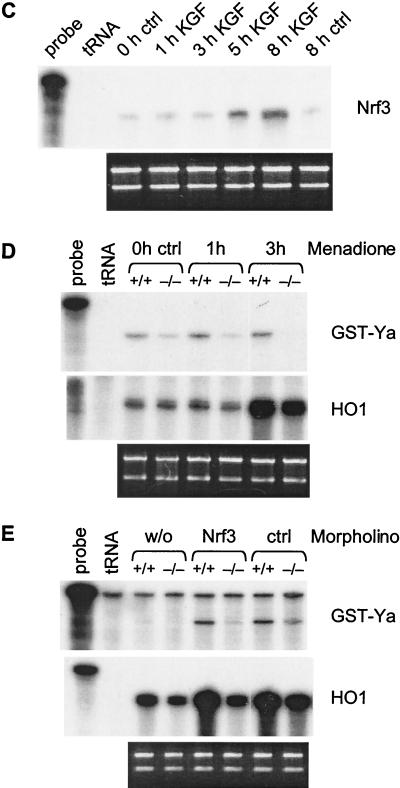

To determine the spatial distribution of Nrf2 and Nrf1 mRNAs in wounded skin, we performed in situ hybridization with 5-day wound sections. At this stage after injury, partial reepithelialization of the wound has occurred, and a thick hyperproliferative epithelium as well as an extensive granulation tissue are present. Strongest Nrf2 signals were observed in the hyperproliferative epidermis at the wound edge, especially in the basal keratinocytes (Fig. 3A, upper right and lower left panels). Signals were also scattered over the granulation tissue, and the positive cells appeared to include macrophages. Nrf1 mRNA was distributed more evenly throughout the wound, but the highest expression was detectable in the hyperproliferative epithelium (Fig. 3B, upper right and lower left panels). No specific signals were obtained with sense riboprobes (Fig. 3A and B, lower right panels).

FIG. 3.

Localization of Nrf2 (A) and Nrf1 (B) mRNAs in 5-day wounds by in situ hybridization. Paraformaldehyde-fixed frozen sections from the middle of 5-day full-thickness excisional wounds from BALB/c mice were hybridized with 35S-labeled sense (lower right panels; magnification, ×100) or antisense (upper right panels; ×100) riboprobes. The upper left panels show an overview over the right wound margin (×50), and the rectangles mark the area of the wounds, which are shown in the panels on the right hand side. Details of the hyperproliferative epithelium (marked with rectangles in the upper right panels) are shown in the lower left panels (×1,000). Signals appear as black dots in the bright field survey (lower left panels) and as white dots in the dark field survey (right panels). D, dermis; E, epidermis; ES, eschar; G, granulation tissue; HE, hyperproliferative epithelium. Sections were counterstained with H/E.

Nrf2−/− mice show no histological wound healing phenotype.

To determine whether a lack of Nrf2 affects the wound healing process, we generated full-thickness excisional wounds on the backs of Nrf2−/− mice, Nrf2+/− mice, and control littermates of the same sex (8 to 12 weeks old). At days 1 and 2 after wounding, the wounds of many knockout mice were wider and the development of the scab was delayed compared to their wild-type littermates. From day 3 on, wounds of knockout and control mice were macroscopically indistinguishable (data not shown). Histological analysis of 1-day, 5-day, and 13-day wounds revealed no obvious abnormalities in the Nrf2−/− mice at either stage after injury, with the exception that incoming inflammatory cells were still observed at day 13 in most of the wounds of Nrf2 null mice (Fig. 4A to D and data not shown; results from each four (1-day wounds), nine (5-day wounds), and six (13-day wounds) control and Nrf2 null mice).

FIG. 4.

(A to D): Histology of 5- and 13-day wounds of wild-type and homozygous Nrf2 knockout mice. Full-thickness excisional wounds were made on the backs of control and Nrf2−/− mice (8 to 12 weeks old). Sections from the middle of 5-day and 13-day wounds were stained with H/E. (A) Five-day wound of a control mouse (+/+); (B) Five-day wound of an Nrf2−/− mouse (−/−); (C) Thirteen-day wound of a control mouse; (D) Thirteen-day wound of an Nrf2−/− mouse. For abbreviations, see the legend to Fig. 3. Magnification, ×50. (E and F) Analysis of cell proliferation in 5-day wounds. Mice were injected with BrdU and sacrificed 2 h after injection. Paraffin sections of wounds from control mice (E) and Nrf2 null mice (F) were incubated with a peroxidase-conjugated antibody against BrdU and stained with the diaminobenzidine-peroxidase staining kit.

In addition, we investigated the cell proliferation rate during wound healing. For this purpose, mice were injected with bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) 2 h before sacrifice. Immunohistological staining using a BrdU-specific antibody allowed the identification of proliferating cells. No significant difference in either the total number or density of proliferating cells in the epidermis and the granulation tissue was seen in 5-day (four control and five knockout animals; Fig. 4E and F) and 13-day wound sections (four control and six knockout animals; data not shown). Furthermore, no difference in the number of apoptotic cells was observed at day 1 after injury as determined by immunostaining with an antibody against caspase-3 (data not shown).

Altered expression of proinflammatory cytokines in Nrf2−/− mice.

To determine potential differences in the inflammatory response between Nrf2 knockout and control mice, we isolated RNA from excisional wounds of wild-type, heterozygous, and homozygous knockout mice at different time points after wounding and performed RNase protection assays with probes for IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α (Fig. 5A). Interestingly, the normally observed induction of IL-1β and TNF-α expression (22) was delayed in the knockout mice. The levels of IL-1β mRNA were 50% lower in the 1-day wounds of Nrf2−/− mice than for control littermates. However, expression was prolonged until day 13 after wounding in Nrf2 null mice. A comparison of the TNF-α expression in knockout and wild-type mice revealed reduced mRNA levels in 1-day wounds of the mutant mice, followed by a significant increase in 5-day wounds (approximately 100% higher). Expression of IL-6 was also lower in 1-day wounds of Nrf2 null mice, but—in contrast to IL-1β—the mRNA of this cytokine was no longer detectable at later stages of repair. All the observed differences were more pronounced in female than in male animals (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

(A) Altered expression of proinflammatory cytokines in wounded skin of Nrf2 knockout mice. mRNA levels of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α were determined by RNase protection assay on 10-μg samples from normal and wounded skin of wild-type (+/+), heterozygous (+/-), and homozygous (−/−) Nrf2 knockout mice. As a loading control the RNA samples were also hybridized with an antisense probe to the housekeeping GAPDH gene. The same set of RNAs was used for the protection assays shown in Fig. 5, 6, and 8. For an explanation of lanes labeled “probe” and “tRNA,” see the legend to Fig. 1. The mRNA levels of the various cytokines during the wound repair process in control, heterozygous, and homozygous Nrf2 knockout mice were quantified by laser scanning densitometry of the autoradiograms (panels on the right-hand side). Results of a representative experiment are shown. The band intensities of the RNase protection assays are expressed as a percentage of the maximal mRNA level for each gene assayed. 1dw, 5dw, and 13dw, 1-, 5-, and 13-day wounds. (B) IL-1β protein content in wild-type (+/+) and homozygous (−/−) knockout mice during wound repair determined by ELISA.

The abnormal expression of proinflammatory cytokines in Nrf2 null mice was confirmed on the protein level for IL-1β as an example. Using an ELISA assay, we quantified the amounts of IL-1β protein in unwounded skin and at different stages of the healing process (Fig. 5B). The amounts of IL-1β protein exactly correlated with the mRNA levels. In comparison to control animals, Nrf2−/− mice showed reduced amounts of IL-1β in 1-day wounds (∼30% reduction) and increased levels after 5 days (∼60% increase), and 13 days postwounding a ∼fourfold-higher concentration of this protein was detectable. This result was reproduced by Western blotting with urea lysates of wounds from an independent wound healing experiment (data not shown).

Since IL-1β and TNF-α are expressed predominantly by neutrophils and macrophages, we determined whether the altered expression of these cytokines in Nrf2 knockout mice is a result of abnormal inflammatory cell infiltration and/or persistence. Immunofluorescence staining of wound sections from wild-type and Nrf2−/− mice using anti-F4/80 and anti-Ly6G antibodies which recognize monocytes/macrophages and neutrophils, respectively, revealed no obvious difference in the number of either type of inflammatory cells in 1-day wounds (data not shown). Macrophages were still abundant in 13-day wounds of the Nrf2 knockout mice, whereas only few of these cells were seen in control animals at this time point (Fig. 6). Neutrophils were not detectable in 13-day wounds of either knockout or wild-type mice (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

Elevated number of macrophages in 13-day wounds of Nrf2 knockout mice. Paraffin sections from 13-day wounds of control mice (+/+) and Nrf2 knockout mice (−/−) were incubated with an antibody against F4/80 and a Cy3-coupled secondary antibody (left panels; magnification, ×200). Serial sections were stained with H/E (right panels; ×50), and the part of the wound that is shown in the respective immunofluorescence is marked with a rectangle.

Delayed expression of extracellular matrix molecules after wounding.

We subsequently analyzed the expression profiles of several matrix molecules by RNase protection assay (Fig. 7). The levels of collagen α1 (I), α1 (III), and fibronectin mRNAs were reduced in 1-day wounds of Nrf2 knockout mice compared to control littermates. At later stages of the repair process, no difference between control and Nrf2−/− animals could be detected. The mRNA levels of collagen α1 (I) were already reduced in the skin of the knockout animals compared to wild-type mice, but this reduced collagen expression was not accompanied by obvious histological abnormalities in the nonwounded skin of Nrf2 null mice (data not shown).

FIG. 7.

Altered expression of extracellular matrix molecules, TGFβ1, and VEGF in wounded skin of Nrf2 knockout mice. mRNA levels of collagens α1 (I) and α1 (III), fibronectin, TGFβ1, and VEGF were determined by RNase protection assay on 10-μg RNA samples from nonwounded back skin and wounds. Hybridization with a GAPDH probe served as a loading control. For an explanation of lanes labeled “probe” and “tRNA,” see the legend to Fig. 1. 1dw, 5dw, and 13dw, 1-, 5-, and 13-day wounds

The different expression pattern of these matrix molecules during wound healing of control and Nrf2−/− mice together with the fact that transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) induces expression of these genes tempted us to speculate about a difference in TGF-β1 expression between knockout and wild-type mice. Indeed, TGF-β1 mRNA was present at lower levels in unwounded back skin and in 1-day wounds of Nrf2−/− mice (Fig. 7). The expression level of TGF-β3 was not altered (data not shown). Expression of VEGF, a major regulator of angiogenesis, was also reduced in nonwounded skin and in 1-day wounds of Nrf2 null mice (Fig. 7). However, this did not lead to obvious abnormalities in angiogenesis as determined by PECAM staining of 5-day wounds (data not shown).

Abnormal expression of the Nrf2 target genes HO1 and GST-Ya.

Finally, we analyzed the expression of the Nrf2 target genes HO1 and GST-Ya during wound repair. To our surprise, the mRNA levels of both genes were identical in unwounded skin of control and Nrf2−/− mice (Fig. 8A). However, at day 1 after injury, the mRNA levels of HO1 and GST-Ya were reduced by more than 50% in the knockout mice compared to control animals. After 5 days, HO1 mRNA levels were higher in knockout mice than in wild-type mice, whereas the mRNA levels of GST-Ya were still lower in knockout animals than in controls. Consistent with the RNA data, decreased amounts of the 32-kDa HO1 protein were detected in lysates from 1-day wounds of Nrf2−/− mice compared to Nrf2+/+ or Nrf2+/− animals. This difference was no longer detectable at later stages of the healing process (Fig. 8B).

FIG. 8.

Altered expression of the Nrf2 target genes HO1 and GST-Ya in wounded skin of Nrf2 knockout mice. (A) The band intensities of RNase protection assays (not shown) were quantified by laser scanning densitometry of the autoradiograms and are expressed as a percentage of the maximal mRNA level for each gene assayed. Results from at least two RNase protection assays with RNAs from independent wound healing experiments were used for this quantitative analysis. (B) Western blot analysis of tissue lysates from normal and wounded skin of control (+/+), Nrf2+/−, and Nrf2−/− mice for the presence of HO1. 1dw, 5dw, and 13dw, 1-day, 5-day, and 13-day wounds.

Nrf3 potentially compensates for the loss of Nrf2.

Although the expression of several wound-regulated genes was significantly altered in normal and particularly in wounded skin of Nrf2 knockout mice, no gross abnormalities of the healing process were observed, and the expression of Nrf2 target genes was not significantly altered at later stages of the repair process. Therefore, we speculated about compensatory mechanisms exerted by other members of the Nrf family. As depicted in Fig. 9A, the expression of Nrf1 was identical in normal and wounded skin of Nrf2+/+, Nrf2+/−, and Nrf2−/− mice. However, elevated levels of Nrf3 mRNA (four- to fivefold up-regulation) were found in unwounded skin and 1 day postwounding in Nrf2 knockout animals compared to wild-type mice. Nrf3 mRNA was present at highest levels in the hyperproliferative epidermis and in the migrating epithelial tongue (Fig. 9B, upper right and lower left panel, respectively). Since these cells are also major producers of Nrf2, our findings suggest that Nrf3 can at least partially compensate for the lack of Nrf2 in normal and wounded skin of Nrf2 null mice.

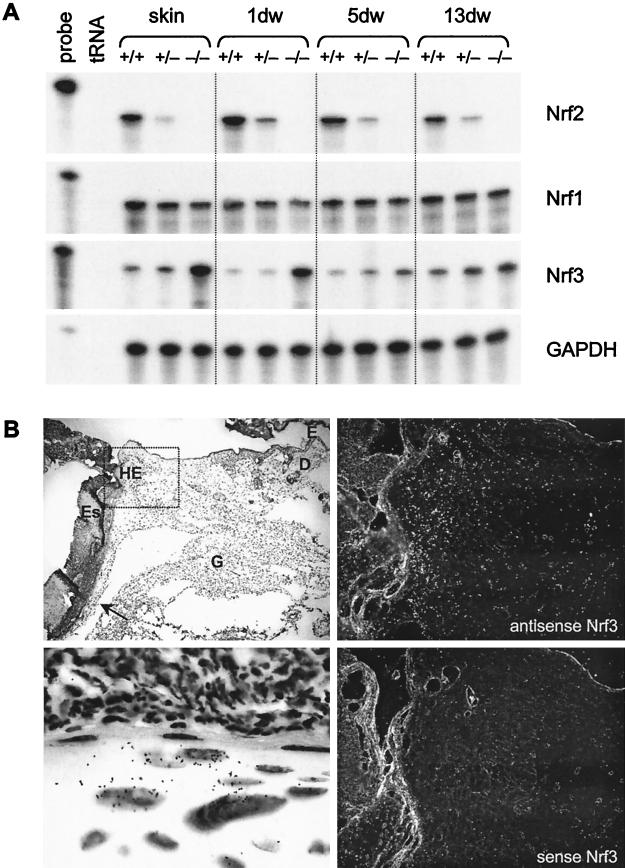

FIG. 9.

A possible compensatory effect of Nrf3 in Nrf2 knockout mice. (A) Ten-microgram RNA samples from unwounded skin and wound tissue of control (+/+), Nrf2+/−, and Nrf2−/− mice were analyzed by RNase protection assay for the presence of Nrf1, Nrf2, and Nrf3 mRNAs. Hybridization with a GAPDH probe served as a loading control. 1dw, 5dw, and 13dw, 1-day, 5-day, and 13-day wounds. (B) Paraformaldehyde-fixed frozen sections from the middle of 5-day full-thickness excisional wounds from BALB/c mice were hybridized with a 35S-labeled sense (lower right panel; magnification, ×200) or antisense (upper right panel; ×200) Nrf3 riboprobes. An overview of half of the wound area is shown in the upper left panel (magnification, ×50). The area indicated by the rectangle is shown in the panels on the right-hand side. Details of the migrating epithelial tongue (marked with an arrow in the upper left panel) are shown in the lower left panel (magnification, ×1,000). Signals appear as black dots in the bright field survey (lower left panel) and as white dots in the dark field survey (right panels). For abbreviations, see the legend to Fig. 3. Sections were counterstained with H/E. (C) HaCaT cells were rendered quiescent by serum starvation and treated with KGF. Total cellular RNA (10 μg) isolated from quiescent and KGF-treated cells was analyzed by RNase protection assay for the expression of Nrf3. (D) Freshly isolated keratinocytes from 3-day-old Nrf2−/− mice and control (ctrl) littermates were rendered quiescent and subsequently treated with menadione. Cells were harvested before and after 1 or 3 h of menadione treatment. (E) Primary keratinocytes from the skin of 3-day-old Nrf2−/− mice and control littermates were transfected either with an antisense morpholino oligonucleotide directed against Nrf3 or with a control morpholino oligonucleotide and treated with menadione for 3 h. Nontransfected cells served as a control. w/o, without morpholino oligonucleotide. Total cellular RNA (10 μg [D] or 5 μg [E]) was analyzed by RNase protection assay for the expression of GST-Ya and HO1 as indicated. Note that the GST-Ya signal seen in menadione-treated, nontransfected cells is visible only in panel D and not in panel E due to the smaller amounts of RNA used in the protection assay shown in panel E. Ethidium bromide-stained agarose gels loaded with each RNA sample (1 μg) served as a loading control for the RNase protection assays shown in panels C, D, and E (shown below the RNase protection assays). For an explanation of lanes in panels C, D, and E labeled “probe” and “tRNA,” see the legend to Fig. 1.

The increased expression of Nrf3 in keratinocytes at the wound edge raised the question of whether this gene is also under the control of KGF. Indeed, RNase protection assays with RNAs from quiescent and KGF-treated HaCaT cells revealed a four- to fivefold up-regulation of Nrf3 mRNA levels by KGF. Maximal mRNA levels were seen between 5 and 8 h after addition of KGF (Fig. 9C), demonstrating a similar regulation of Nrf2 and Nrf3 in keratinocytes.

Finally, we determined if the reduced expression of HO-1 and GST-Ya in the Nrf2 knockout mice is at least partially due to a downregulation of these genes in keratinocytes and whether Nrf3 is also involved in the regulation of these genes. For this purpose, primary keratinocytes were established from 3-day-old Nrf2−/− mice and control littermates and treated for 1 to 3 h with menadione, a potent xenobiotic that induces the generation of ROS in the cells. As shown in Fig. 9D, the basal and in particular the menadione-induced expression of GST-Ya was significantly reduced in Nrf2−/− cells compared to control cells. The lack of Nrf2 did not affect the basal expression of HO1 in keratinocytes, but the inducibility of this gene by menadione was also reduced. These results demonstrate that Nrf2 is also a regulator of HO1 and GST-Ya expression in keratinocytes.

To determine if the residual expression of HO1 and GST-Ya in Nrf2-deficient keratinocytes can be further reduced by inhibition of Nrf3, we analyzed the expression of these genes in menadione-treated (3 h) keratinocytes that had been transfected with morpholino antisense oligonucleotides against Nrf3 or with control morpholino oligonucleotides. Treatment with any morpholino oligonucleotide increased the expression of HO1 and GST-Ya (Fig. 9E), possibly reflecting a stress response. Importantly, however, expression of these genes was reduced in the presence of the Nrf3 oligonucleotide in Nrf2-deficient cells but not in wild-type cells. These results suggest that Nrf2 is predominantly responsible for the ROS-induced expression of HO1 and GST-Ya in keratinocytes but that Nrf3 can at least partially compensate for a lack of Nrf2 in these cells.

DISCUSSION

Nrf2, a novel target of KGF action.

The important role of KGF receptor signaling in epithelial repair and cytoprotection is well established (reviewed in reference 49). Therefore, clinical trials have been initiated with KGF and FGF10 for the treatment of wound healing disorders and also of radiation- and chemotherapy-induced mucositis (12, 27). However, the mechanisms of KGF action are still poorly understood. In this study, we identified the Nrf2 gene as a novel target of KGF action. This is the first demonstration that Nrf2 is regulated by growth factors on the transcriptional level and suggests that upregulation of Nrf2 is at least partially responsible for the cytoprotective effect of KGF and FGF10.

Several results indicate that KGF is also an inducer of Nrf2 expression in vivo: (i) We found a coordinated induction of Nrf2 (this study) and KGF (46) expression after skin injury, (ii) Nrf2 is expressed at particularly high levels in the KGF-responsive keratinocytes of the hyperproliferative wound epithelium, and (iii) expression of Nrf2 is reduced in normal and wounded skin of transgenic mice that express dominant-negative FGFR2-IIIb in the epidermis (preliminary data from our laboratory). In addition, other ligands of FGFR2-IIIb, in particular FGF10, as well as ligands of the EGF receptor, which are also expressed at high levels in the healing skin wound (32), are likely to further enhance the levels of Nrf2 during wound healing.

Nrf2, a regulator of inflammation in wounded skin.

To elucidate the function of Nrf2 in the wound healing process, we wounded Nrf2 knockout mice. The results presented in this study indeed revealed several remarkable differences between Nrf2 null mice and control animals. In particular, expression of proinflammatory cytokines, which are mainly expressed by neutrophils and macrophages in the wound, was strongly reduced 1 day after wounding. The reduced expression of these genes in early wounds might be due to (i) a reduced number of inflammatory cells recruited to the wound, (ii) enhanced death of these cells caused by elevated levels of ROS, or (iii) reduced expression of these proinflammatory cytokines by the immigrated inflammatory cells. Although exact quantification of neutrophils was hampered by their massive infiltration into the clot, where their numbers are not readily discernible, we observed no obvious differences in the number of inflammatory cells or apoptotic cells between wild-type mice and knockout mice. These results suggest that the reduced levels of IL-1β and TNF-α are a direct consequence of the lack of Nrf2 in inflammatory cells. This hypothesis is in line with a previous finding obtained with mast cells, where Nrf2 was shown to be involved in the transcription factor complex formation at the AP1 site of the TNF-α promoter (37). An involvement of Nrf2 also seems likely for the expression of IL-6, since an ARE is present in its promoter (45). However, Nrf2 is obviously not the only regulator of these genes, since their expression was higher in 5-day wounds of Nrf2 knockout mice than for controls, demonstrating that other inducers of these genes can compensate for the lack of Nrf2.

Surprisingly, IL-1β levels were still elevated in 13-day wounds, most likely due to the longer persistence of macrophages in the wound. The latter finding suggests that an as yet unknown inflammatory stimulus is still present in the wounds of Nrf2 knockout mice at this late stage of repair.

Nrf2 regulates the expression of cytoprotective proteins in keratinocytes under stress conditions.

To our surprise, expression of the Nrf2 target genes HO1 and GST-Ya was not altered in nonwounded skin of Nrf2 knockout mice. Furthermore, expression of these genes in nonstressed cultured keratinocytes was not significantly affected by a lack of Nrf2. These findings are consistent with results from a recent study that demonstrated that the basal expression of HO1 is not altered in macrophages of Nrf2 knockout animals. In this case, strong differences were only seen in macrophages after treatment with ROS (24). Similarly, we also observed a strongly reduced expression of HO1 and GST-Ya in Nrf2-deficient keratinocytes after menadione treatment. Furthermore, the major difference in HO1 and GST-Ya expression was seen at day 1 after wounding, when high levels of ROS are present, indicating that Nrf2 mainly affects the ROS-induced expression of these genes. The reduced expression was, however, no longer detectable at later stages after injury, indicating that HO1 expression can also be induced via mechanisms that are independent of Nrf2. Possible alternative inducers are nitric oxide (reviewed in reference 14) and hypoxia (30).

Nrf3 can at least partially compensate for the lack of Nrf2 in keratinocytes.

Although the present study revealed obvious differences in the wound healing process between Nrf2 knockout mice and control animals, the abnormalities were clearly less severe than expected. In particular, no defect in reepithelialization was observed, in spite of the high levels of Nrf2 in keratinocytes. This finding suggested that other genes can compensate—at least in part—for the lack of Nrf2. Nrf1 could be one of them, since it is also highly expressed in keratinocytes. Most interestingly, Nrf3 was also found to be expressed in keratinocytes of the wound epidermis, and a striking increase in Nrf3 expression was observed in normal and wounded skin of the Nrf2 knockout mice. Although this transcription factor is as yet poorly characterized, the fact that it can bind to AREs (29) suggests that Nrf3 can perform functions similar to those of Nrf2. Moreover, downregulation of Nrf3 expression in Nrf2−/− keratinocytes resulted in a reduced inducibility of HO-1 and GST-Ya by menadione, suggesting that Nrf3 can indeed contribute to the ROS-induced expression of these genes. Finally, the two transcription factors are obviously regulated in a similar manner, since they were both found to be up-regulated in response to KGF.

Tissue-specific effects of Nrf2.

A much more severe phenotype was observed when other organs, including the lung and the liver of the Nrf2 knockout mice, were challenged by either butylated hydroxytoluene or N-acetyl-p-aminophenol (8, 9, 13). This could be due to the more severe stress exerted by these treatments compared to the stress occurring during normal wound healing. Thus, more-severe healing abnormalities might be seen in infected wounds where much higher levels of ROS are present. Alternatively, any compensatory effects exerted by Nrf1, Nrf3, or other transcription factors might be lower in the liver and the lung than in the skin. Finally, the Nrf2 dependence of tissue repair could be organ specific, as suggested by recent results from this laboratory that demonstrated a much stronger up-regulation of Nrf1 than of Nrf2 after lesion to the hippocampus (21).

Dual regulation of Nrf2.

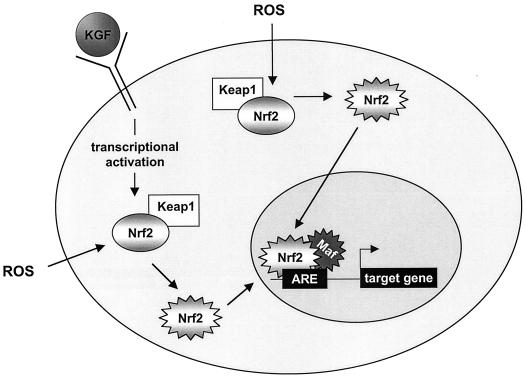

In summary, we have identified the Nrf2 and Nrf3 transcription factors as novel targets of KGF action in keratinocytes in vitro and possibly also in vivo in wounded skin. Our results suggest that the presence of high levels of KGF in the wound stimulates Nrf2/Nrf3 expression. The simultaneous presence of ROS in the early phase of wound repair is likely to activate these transcription factors, as shown in vitro for Nrf2, which is liberated from its inhibitor Keap1 in the presence of ROS. Thus, the simultaneous presence of KGF and ROS in the wound and in inflamed tissues in general is likely to result in high levels of biologically active Nrfs (Fig. 10), which are required for the efficient induction of various cytoprotective proteins. Therefore, this dual regulation could play a major role in the protection of cells from oxidative stress after tissue injury and also in inflammatory diseases of epithelial tissues where KGF is also highly expressed (reviewed in reference 49).

FIG. 10.

Model of Nrf2 activation by KGF and ROS. Triggered by ROS, the inactive Nrf2 (gray shaded oval) is liberated from its cytosolic inhibitor, Keap1, and therefore activated. Subsequently, the active Nrf2 (jagged gray shaded oval) is translocated into the nucleus, where it dimerizes with small Maf proteins, binds to the ARE sequence, and initiates the transcription of target genes (26). As shown in this study, KGF stimulates the expression of Nrf2. In inflamed tissues, e.g., in wounded skin, the newly synthesized Nrf2 protein is likely to be activated by ROS.

Acknowledgments

We thank Silke Durka for excellent technical assistance and P. Boukamp for HaCaT keratinocytes.

This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant no. 31-61358.00 to S.W.), the Stiftung VERUM (to S.W.), and a Boehringer Ingelheim predoctoral fellowship (to U.A.D.K).

REFERENCES

- 1.Beer, H. D., C. Florence, J. Dammeier, L. McGuire, S. Werner, and D. R. Duan. 1997. Mouse fibroblast growth factor 10: cDNA cloning, protein characterization, and regulation of mRNA expression. Oncogene 15:2211-2218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bloch, W., K. Huggel, R. Sasaki, R. Grose, P. Bugnon, K. Addicks, R. Timpl, and S. Werner. 2000. The angiogenesis inhibitor endostatin impairs blood vessel maturation during wound healing. FASEB J. 14:2373-2376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boukamp, P., R. T. Petrussevska, D. Breitkreutz, J. Hornung, A. Markham, and N. E. Fusenig. 1988. Normal keratinization in a spontaneously immortalized aneuploid human keratinocyte cell line. J. Cell Biol. 106:761-771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caldelari, R., M. M. Suter, D. Baumann, A. De Bruin, and E. Müller. 2000. Long-term culture of murine epidermal keratinocytes. J. Investig. Dermatol. 114:1064-1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan, J. Y., X. L. Han, and Y. W. Kan. 1993. Isolation of cDNA encoding the human NF-E2 protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:11366-11370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan, J. Y., X. L. Han, and Y. W. Kan. 1993. Cloning of Nrf1, an NF-E2-related transcription factor, by genetic selection in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:11371-11375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan, K., R. Lu, J. C. Chang, and Y. W. Kan. 1996. NRF2, a member of the NFE2 family of transcription factors, is not essential for murine erythropoiesis, growth, and development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:13943-13948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan, K., and Y. W. Kan. 1999. Nrf2 is essential for protection against acute pulmonary injury in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:12731-12736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan, K., X. D. Han, and Y. W. Kan. 2001. An important function of Nrf2 in combating oxidative stress: detoxification of acetaminophen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:4611-4616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chomczynski, P., and N. Sacchi. 1987. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal. Biochem. 162:156-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clark, R. A. F. 1996. Wound repair. Overview and general considerations, p. 3-50. In R. A. F. Clark (ed.), The molecular and cellular biology of wound repair, 2nd ed. Plenum Press, New York, N.Y.

- 12.Danilenko, D. M. 1999. Preclinical and early clinical development of keratinocyte growth factor, an epithelial-specific tissue growth factor. Toxicol. Pathol. 27:64-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Enomoto, A., K. Itoh, E. Nagayoshi, J. Haruta, T. Kimura, T. O'Connor, T. Harada, and M. Yamamoto. 2001. High sensitivity of Nrf2 knockout mice to acetaminophen hepatotoxicity associated with decreased expression of ARE-regulated drug metabolizing enzymes and antioxidant genes. Toxicol. Sci. 59:169-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foresti, R., and R. Motterlini. 1999. The heme oxygenase pathway and its interaction with nitric oxide in the control of cellular homeostasis. Free Radic. Res. 31:459-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frank, S., G. Hübner, G. Breier, M. T. Longaker, D. G. Greenhalgh, and S. Werner. 1995. Regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor expression in cultured keratinocytes: implications for normal and impaired wound healing. J. Biol. Chem. 270:12607-12613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frank, S., M. Madlener, and S. Werner. 1996. Transforming growth factors β1, β2, and β3 and their receptors are differentially regulated during normal and impaired wound healing. J. Biol. Chem. 271:10188-10193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Friling, R. S., A. Bensimon, Y. Tichauer, and V. Daniel. 1990. Xenobiotic-inducible expression of murine glutathione S-transferase Ya subunit gene is controlled by an electrophile-responsive element. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:6258-6262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gassmann, M. G., and S. Werner. 2000. Caveolin-1 and -2 expression is differentially regulated in cultured keratinocytes and within the regenerating epidermis of cutaneous wounds. Exp. Cell Res. 258:23-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guo, L., L. Degenstein, and E. Fuchs. 1996. Keratinocyte growth factor is required for hair development but not for wound healing. Genes Dev. 15:165-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanselmann, C., C. Mauch, and S. Werner. 2001. Haem oxygenase-1: a novel player in cutaneous wound repair and psoriasis? Biochem. J. 353:459-466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hertel, M., S. Braun, S. Durka, C. Alzheimer, and S. Werner. Upregulation and activation of the Nrf-1 transcription factor in the lesioned hippocampus as a novel neuroprotective mechanism against reactive oxygen species. Eur. J. Neurosci., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Hübner, G., M. Brauchle, H. Smola, M. Madlener, R. Fässler, and S. Werner. 1996. Differential regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines during wound healing in normal and glucocorticoid-treated mice. Cytokine 8:548-556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Igarashi, M., P. W. Finch, and S. A. Aaronson. 1998. Characterization of recombinant human fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-10 reveals functional similarities with keratinocyte growth factor (FGF-7). J. Biol. Chem. 273:13230-13235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ishii, T., K. Itoh, S. Takahashi, H. Sato, T. Yanagawa, Y. Katoh, S. Bannai, and M. Yamamoto. 2000. Transcription factor Nrf2 coordinately regulates a group of oxidative stress-inducible genes in macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 275:16023-16029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Itoh, K., T. Chiba, S. Takahashi, T. Ishii, K. Igarashi, Y. Katoh, T. Oyake, N. Hayashi, K. Satoh, I. Hatayama, M. Yamamoto, and Y. Nabeshima. 1997. An Nrf2/small Maf heterodimer mediates the induction of phase II detoxifying enzyme genes through antioxidant response elements. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 236:313-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Itoh, K., N. Wakabayashi, Y. Katoh, T. Ishii, K. Igarashi, J. D. Engel, and M. Yamamoto. 1999. Keap1 represses nuclear activation of antioxidant responsive elements by Nrf2 through binding to the amino-terminal Neh2 domain. Genes Dev. 13:76-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jimenez, P. A., D. Greenwalt, D. L. Mendrick, M. A. Rampy, J. Su, K. H. Leung, and K. M. Connolly. 2000. Keratinocyte growth factor-2, p. 101-119. In S. Narula and R. Coffman (ed.), New cytokines as potential drugs. Birkhäuser Verlag, Basel, Switzerland.

- 28.Johnsen, O., R. Murphy, H. Prydz, and A. B. Kolsto. 1998. Interaction of the CNC-bZIP factor TCF11/LCR-F1/Nrf1 with MafG: binding-site selection and regulation of transcription. Nucleic Acids Res. 26:512-520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kobayashi, A., E. Ito, T. Toki, K. Kogame, S. Takahashi, K. Igarashi, N. Hayashi, and M. Yamamoto. 1999. Molecular cloning and functional characterization of a new Cap'n'Collar family transcription factor Nrf3. J. Biol. Chem. 274:6443-6452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee, P. J., B. H. Jiang, B. Y. Chin, N. V. Iyer, J. Alam, G. L. Semenza, and A. M. Choi. 1997. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 mediates transcriptional activation of the heme oxygenase-1 gene in response to hypoxia. J. Biol. Chem. 272:5375-5381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marchese, C., M. Chedid, O. R. Dirsch, K. G. Csaky, F. Santanelli, C. Latini, W. J. LaRochelle, M. R. Torrisi, and S. A. Aaronson. 1995. Modulation of keratinocyte growth factor and its receptor in reepithelializing human skin. J. Exp. Med. 182:1369-1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marikovsky, M., K. Breuing, P. Y. Liu, E. Eriksson, S. Higashiyama, P. Farber, J. Abraham, and M. Klagsbrun. 1993. Appearance of heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor in wound fluid as a response to injury. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:3889-3893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marini, M. G., K. Chan, L. Casula, Y. W. Kan, A. Cao, and P. Moi. 1997. hMAF, a small human transcription factor that heterodimerizes specifically with Nrf1 and Nrf2. J. Biol. Chem. 272:16490-16497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martin, P. 1997. Wound healing—aiming for perfect skin regeneration. Science 276:75-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moi, P., K. Chan, I. Asunis, A. Cao, and Y. W. Kan. 1994. Isolation of NF-E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), a NF-E2-like basic leucine zipper transcriptional activator that binds to the tandem NF-E2/AP1 repeat of the β-globin locus control region. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:9926-9930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mulcahy, R. T., M. A. Wartman, H. H. Bailey, and J. J. Gipp. 1997. Constitutive and β-naphthoflavone-induced expression of the human γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase heavy subunit gene is regulated by a distal antioxidant response element/TRE sequence. J. Biol. Chem. 272:7445-7454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Novotny, V., E. E. Prieschl, R. Csonga, G. Fabjani, and T. Baumruker. 1998. Nrf1 in a complex with fosB, c-jun, junD and ATF2 forms the AP1 component at the TNFα promoter in stimulated mast cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 26:5480-5485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oyake, T., K. Itoh, H. Motohashi, N. Hayashi, H. Hoshino, M. Nishizawa, M. Yamamoto, and K. Igarashi. 1996. Bach proteins belong to a novel family of BTB-basic leucine zipper transcription factors that interact with MafK and regulate transcription through the NF-E2 site. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:6083-6095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prestera, T., P. Talalay, J. Alam, Y. I. Ahn, P. J. Lee, and A. M. Choi. 1995. Parallel induction of heme oxygenase-1 and chemoprotective phase 2 enzymes by electrophiles and antioxidants: regulation by upstream antioxidant-responsive elements (ARE). Mol. Med. 1:827-837. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rubin, J. S., D. P. Bottaro, M. Chedid, T. Miki, D. Ron, H.-G. Cheon, W. G. Taylor, E. Fortney, H. Sakata, P. W. Finch, and W. J. LaRochelle. 1995. Keratinocyte growth factor. Cell Biol. Int. 19:399-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rushmore, T. H., R. G. King, K. E. Paulson, and C. B. Pickett. 1990. Regulation of glutathione S-transferase Ya subunit gene expression: identification of a unique xenobiotic-responsive element controlling inducible expression by planar aromatic compounds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:3826-3830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rushmore, T. H., M. R. Morton, and C. B. Pickett. 1991. The antioxidant responsive element. Activation by oxidative stress and identification of the DNA consensus sequence required for functional activity. J. Biol. Chem. 266:11632-11639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Venugopal, R., and A. K. Jaiswal. 1996. Nrf1 and Nrf2 positively and c-fos and Fra1 negatively regulate the human antioxidant response element-mediated expression of NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase1 gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:14960-14965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Venugopal, R., and A. K. Jaiswal. 1998. Nrf2 and Nrf1 in association with Jun proteins regulate antioxidant response element-mediated expression and coordinated induction of genes encoding detoxifying enzymes. Oncogene 17:3145-3156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wasserman, W. W., and W. E. Fahl. 1997. Functional antioxidant responsive elements. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:5361-5366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Werner, S., K. G. Peters, M. T. Longaker, F. Fuller-Pace, M. J. Banda, and L. T. Williams. 1992. Large induction of keratinocyte growth factor expression in the dermis during wound healing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:6896-6900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Werner, S., W. Weinberg, X. Liao, K. G. Peters, M. Blessing, S. H. Yuspa, R. L. Weiner, and L. T. Williams. 1993. Targeted expression of a dominant-negative FGF receptor mutant in the epidermis of transgenic mice reveals a role of FGF in keratinocyte organization and differentiation. EMBO J. 12:2635-2643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Werner, S., H. Smola, X. Liao, M. T. Longaker, T. Krieg, P. H. Hofschneider, and L. T. Williams. 1994. The function of KGF in morphogenesis of epithelium and re-epithelialization of wounds. Science 266:819-822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Werner, S. 1998. Keratinocyte growth factor: a unique player in epithelial repair processes. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 9:153-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wilkinson, D. G., J. A. Bailes, J. E. Champion, and A. P. McMahon. 1987. A molecular analysis of mouse development from 8 to 10 days post coitum detects changes only in embryonic globin expression. Development 99:493-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]