Abstract

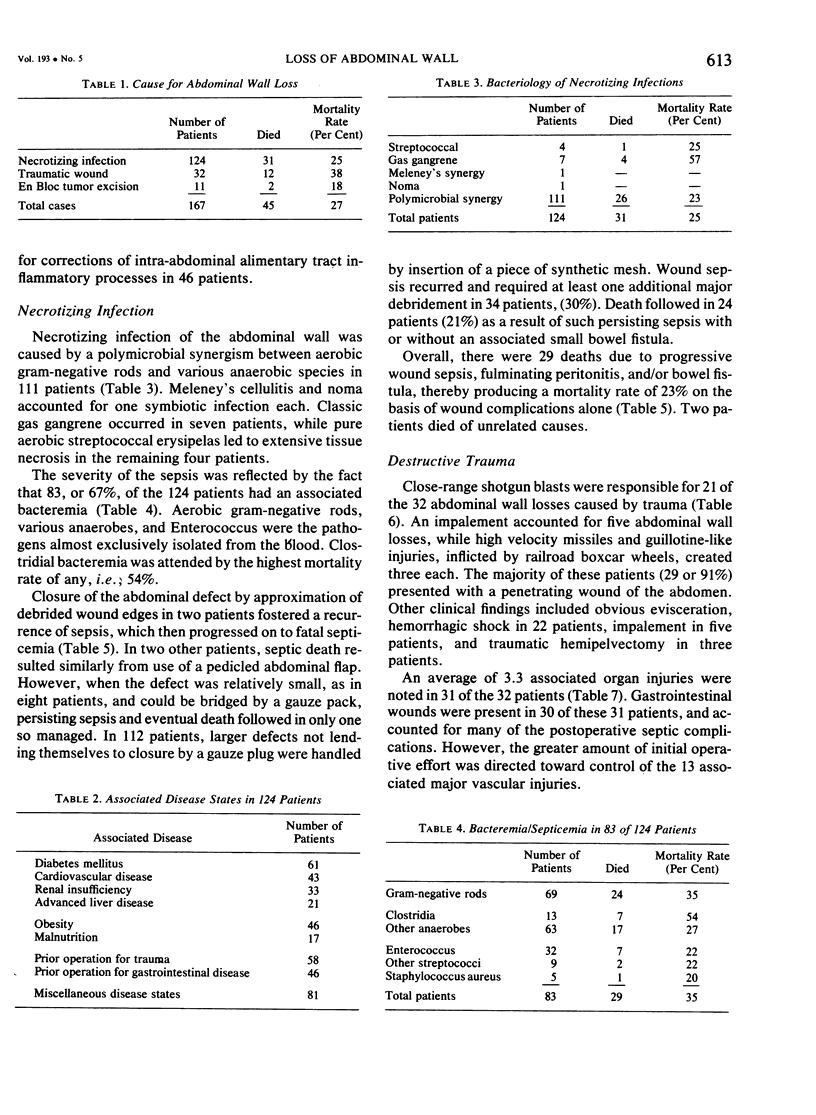

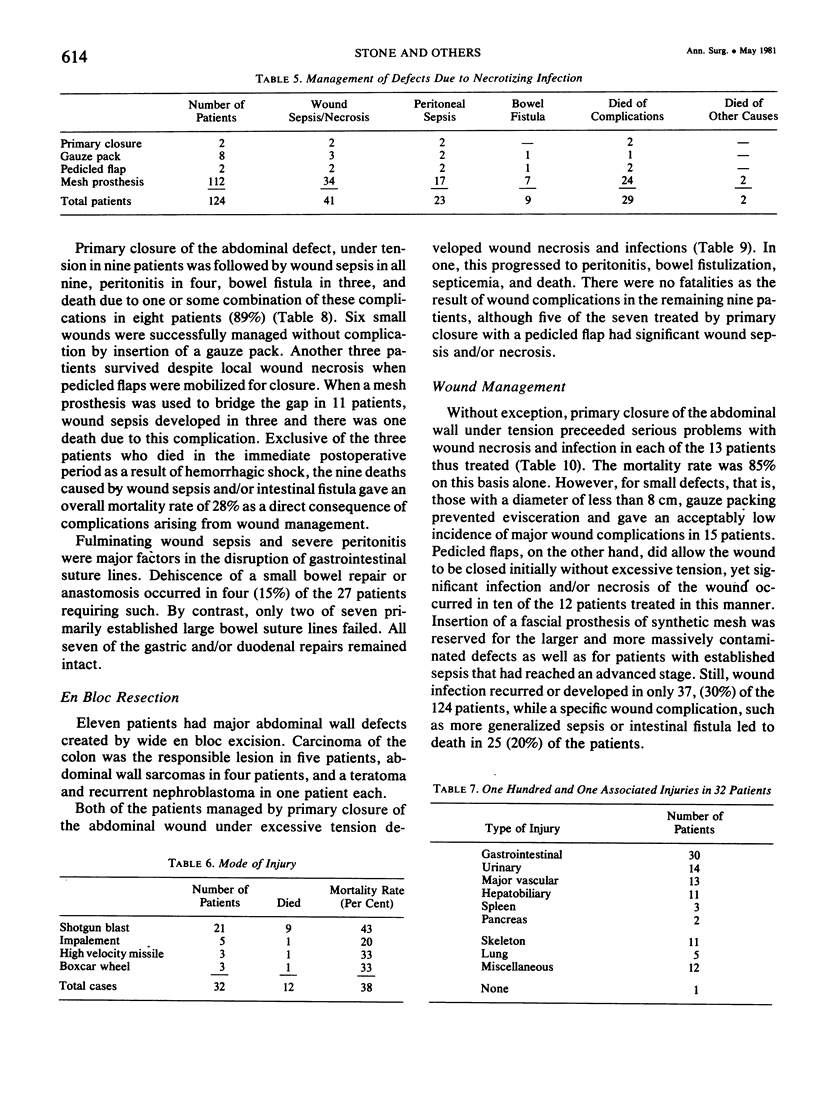

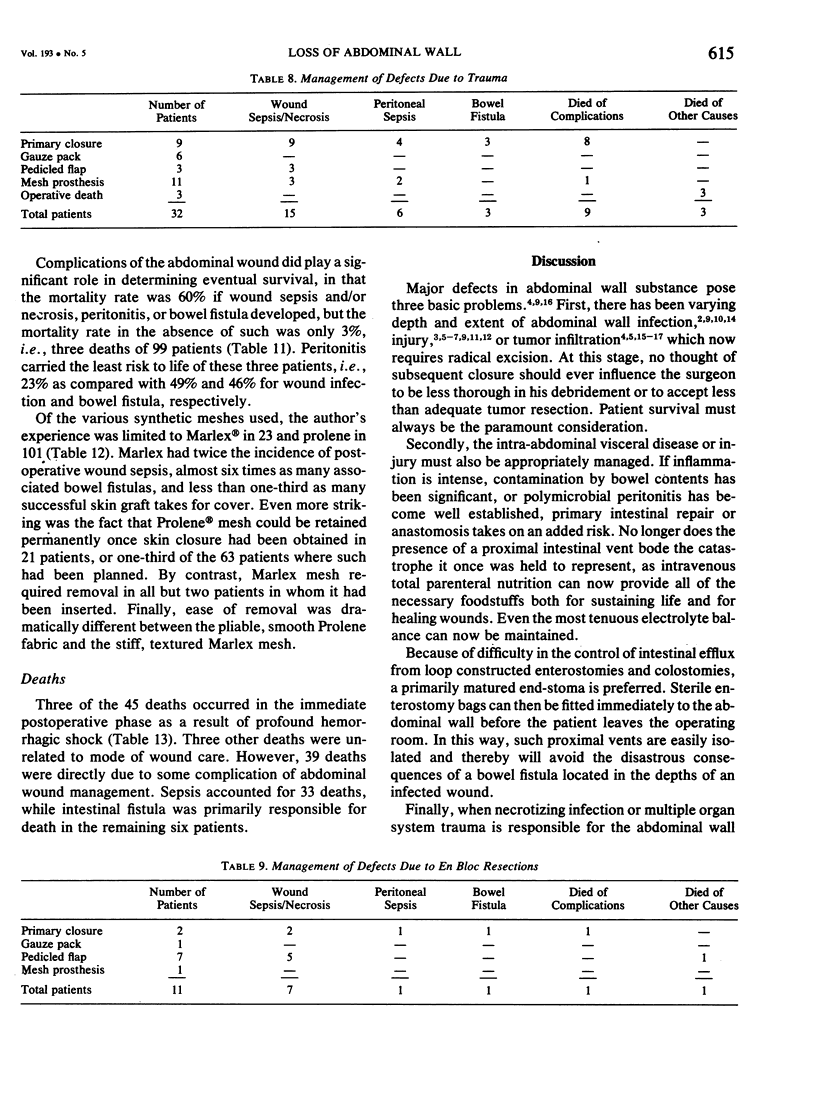

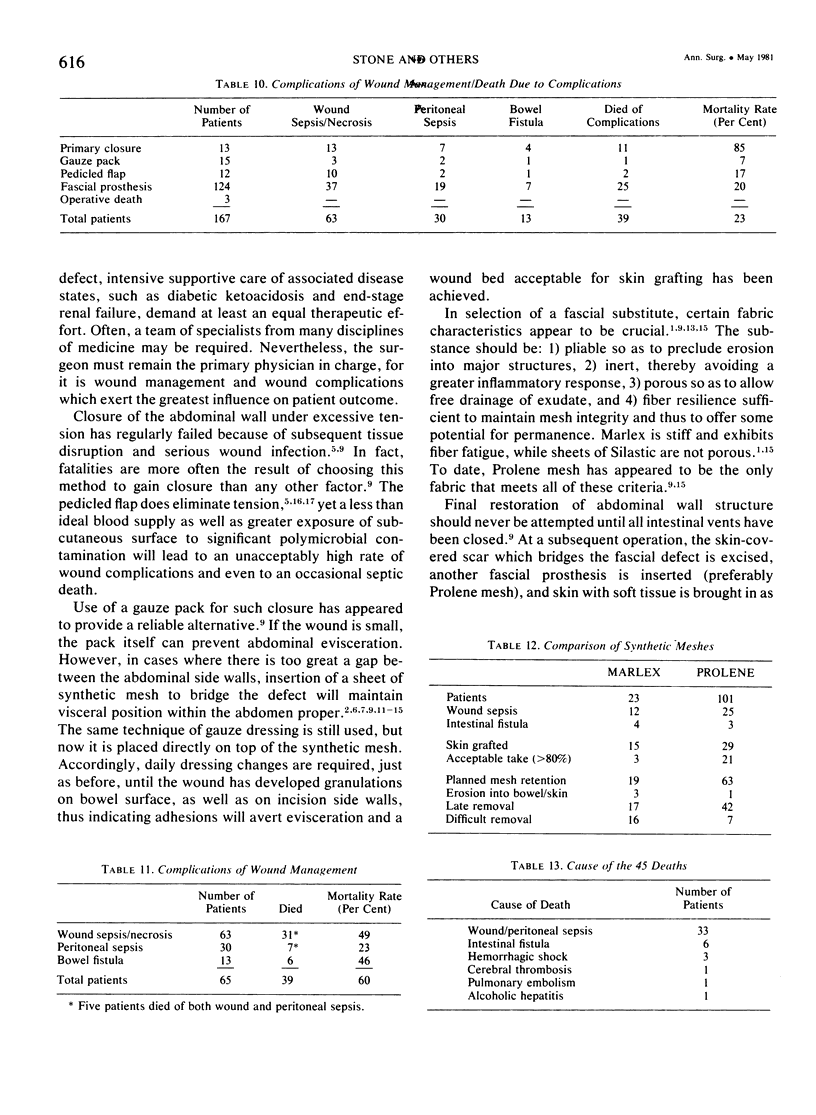

Over a 20-year interval, 167 patients sustained acute full-thickness abdominal wall loss due to necrotizing infection (124 patients), destructive trauma (32 patients), or en bloc tumor excision (11 patients). Polymicrobial infection or contamination was present in all but five of the patients. Of 13 patients managed by debridement and primary closure under tension, abdominal wall dehiscence occurred in each. Only two patients survived, the 11 deaths being caused by wound sepsis, evisceration, and/or bowel fistula. Debridement and gauze packing of a small defect was used in 15 patients; the single death resulted from recurrence of infectious gangrene. Pedicled flap closure, with or without a fascial prosthesis beneath, led to survival in nine of the 12 patients so-treated; yet flap necrosis from infection was a significant complication in seven patients who survived. The majority of patients (124) were managed by debridements, insertions of a fascial prostheses (prolene in 101 patients, marlex in 23 patients), and alternate day dressing changes, until the wound could be closed by skin grafts placed directly on granulations over the mesh or the bowel itself after the mesh had been removed. Sepsis and/or intestinal fistulas accounted for 25 of the 27 deaths. Major principles to evolve from this experience were: 1) insertion of a synthetic prosthesis to bridge any sizeable defect in abdominal wall rather than closure under tension or via a primarily mobilized flap; 2) use of end bowel stomas rather than exteriorized loops or primary anastomoses in the face of active infection, significant contamination, and/or massive contusion; and 3) delay in final reconstruction until all intestinal vents and fistulas have been closed by prior operation.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- ADLER R. H., FIRME C. N. Use of pliable synthetic mesh in the repair of hernias and tissue defects. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1959 Feb;108(2):199–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eng K., Casson P., Berman I. R., Slattery L. R. Clostridial myonecrosis of the abdominal wall. Resection and prosthetic replacement. Am J Surg. 1973 Mar;125(3):367–371. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(73)90064-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FITZGERALD J. B., QUAST D. C., BEALL A. C., Jr, DEBAKEY M. E. SURGICAL EXPERIENCE WITH 103 TRUNCAL SHOTGUN WOUNDS. J Trauma. 1965 Jan;5:72–84. doi: 10.1097/00005373-196501000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HERSHEY F. B., BUTCHER H. R., Jr REPAIR OF DEFECTS AFTER PARTIAL RESECTION OF THE ABDOMINAL WALL. Am J Surg. 1964 Apr;107:586–590. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(64)90325-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LESNICK G. J., DAVIDS A. M. Repair of surgical abdominal wall defect with a pedicled musculofascial flap. Ann Surg. 1953 Apr;137(4):569–572. doi: 10.1097/00000658-195304000-00024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansberger A. R., Jr, Kang J. S., Beebe H. G., Le Flore I. Repair of massive acute abdominal wall defects. J Trauma. 1973 Sep;13(9):766–774. doi: 10.1097/00005373-197309000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markgraf W. H. Abdominal wound dehiscence. A technique for repair with Marlex mesh. Arch Surg. 1972 Nov;105(5):728–732. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1972.04180110051013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathes S. J., Stone H. H. Acute traumatic losses of abdominal wall substance. J Trauma. 1975 May;15(5):386–391. doi: 10.1097/00005373-197505000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan A., Morain W., Eraklis A. Gas gangrene of the abdominal wall: management after extensive debridement. Ann Surg. 1971 Apr;173(4):617–622. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197104000-00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokorny W. J., Thal A. P. A method for primary closure of large contaminated abdominal wall defects. J Trauma. 1973 Jun;13(6):542–547. doi: 10.1097/00005373-197306000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt H. J., Jr, Grinnan G. L. Use of Marlex mesh in infected abdominal war wound. Am J Surg. 1967 Jun;113(6):825–828. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(67)90355-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone H. H., Hester T. R., Jr Management of complicated omphaloceles. Am Surg. 1971 Apr;37(4):224–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone H. H., Martin J. D., Jr Synergistic necrotizing cellulitis. Ann Surg. 1972 May;175(5):702–711. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197205000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USHER F. C., WALLACE S. A. Tissue reaction to plastics; a comparison of nylon, orlon, dacron, teflon, and marlex. AMA Arch Surg. 1958 Jun;76(6):997–999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]