Abstract

Reovirus infection activates NF-κB, which leads to programmed cell death in cultured cells and in the murine central nervous system. However, little is known about how NF-κB elicits this cellular response. To identify host genes activated by NF-κB following reovirus infection, we used HeLa cells engineered to express a degradation-resistant mutant of IκBα (mIκBα) under the control of an inducible promoter. Induction of mIκBα inhibited the activation of NF-κB and blocked the expression of NF-κB-responsive genes. RNA extracted from infected and uninfected cells was used in high-density oligonucleotide microarrays to examine the expression of constitutively activated genes and reovirus-stimulated genes in the presence and absence of an intact NF-κB signaling axis. Comparison of the microarray profiles revealed that the expression of 176 genes was significantly altered in the presence of mIκBα. Of these genes, 64 were constitutive and not regulated by reovirus, and 112 were induced in response to reovirus infection. NF-κB-regulated genes could be grouped into four distinct gene clusters that were temporally regulated. Gene ontology analysis identified biological processes that were significantly overrepresented in the reovirus-induced genes under NF-κB control. These processes include the antiviral innate immune response, cell proliferation, response to DNA damage, and taxis. Comparison with previously identified NF-κB-dependent gene networks induced by other stimuli, including respiratory syncytial virus, Epstein-Barr virus, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and heart disease, revealed a number of common components, including CCL5/RANTES, CXCL1/GRO-α, TNFAIP3/A20, and interleukin-6. Together, these results suggest a genetic program for reovirus-induced apoptosis involving NF-κB-directed expression of cellular genes that activate death signaling pathways in infected cells.

Mammalian reoviruses have served as highly tractable models for studies of viral pathogenesis (59). Reoviruses are nonenveloped, icosahedral viruses with a genome consisting of 10 double-stranded RNA segments (37). Following attachment to cellular receptors (2, 7) and entry by receptor-mediated endocytosis (17, 50), reovirus replication occurs exclusively in the cytoplasm. Newborn mice infected with reovirus sustain injury to a variety of organs, including the central nervous system (CNS), heart, and liver (62). Reovirus induces the morphological and biochemical features of apoptosis in cultured cells (10, 60) and in vivo (11, 13, 38). Apoptotic cell death appears to be the primary mechanism for virus-induced tissue injury in the murine CNS (38, 39) and heart (11, 13).

In both cell culture models and the murine CNS, apoptosis induced by reovirus is contingent upon activation of transcription factor NF-κB (2, 8, 10, 39). NF-κB plays a critical role in the activation of innate immune responses (1, 45) and can either prevent or potentiate death signaling depending on the cell type and stimulatory cue (22). NF-κB family members exist as heterodimers or homodimers sequestered in the cytoplasm by association with IκBα or other structurally related inhibitors (1, 22). Agonists of NF-κB, including viral infection, trigger a signaling cascade that leads to phosphorylation and degradation of IκBα, which in turn permits translocation of NF-κB into the nucleus, where target gene transcription is activated (4).

Following reovirus infection, the prototypical form of NF-κB containing p50 and p65 subunits translocates to the nucleus and activates proapoptotic gene expression (10, 39). Activation of NF-κB is not dependent on viral RNA synthesis but does require signaling responses elicited by viral disassembly in the endocytic pathway (9). Reovirus-induced apoptosis is blocked in proteasome-arrested cells or following enforced cellular expression of degradation-resistant forms of IκBα, indicating that NF-κB is essential for proapoptotic signaling (10). Consistent with this requirement, cell lines deficient in either the p50 or p65 subunits of NF-κB are resistant to reovirus-induced apoptosis (10). Moreover, apoptosis is diminished in the CNS of mice lacking a functional nfkb1/p50 gene (39).

Despite these data linking NF-κB to reovirus pathobiology, the underlying genetic program for reovirus-induced apoptosis is unknown. To identify the relevant NF-κB-responsive genes, we monitored gene expression profiles in mammalian cells that express a degradation-resistant mutant of IκBα (mIκBα) under the control of an inducible promoter (57). These microarray experiments revealed a network of NF-κB-regulated genes that are activated by reovirus in a temporal pattern. Remarkably, a substantial number of these transcription units are involved in host innate immune responses, including interferon (IFN)-stimulated genes (ISGs). Our findings raise the possibility that innate immune response genes are involved in the mechanism by which NF-κB induces apoptosis in reovirus-infected cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

Spinner-adapted murine L929 (L) cells were grown in suspension or monolayer culture and maintained as described elsewhere (10). HeLa cells expressing mIκBα were generated and maintained as described previously (57). Expression of mIκBα was suppressed by the addition of 2 μg of doxycycline per ml to the medium. Reovirus strain type 3 Dearing (T3D) is a laboratory stock. Viral particles were purified by freon extraction of infected cell lysates and CsCl gradient centrifugation as described elsewhere (18). Titers of infectious virus were determined by plaque assay using L cell monolayers (61).

Immunoblot analysis.

HeLa cells (7 × 106) grown in 100-mm tissue culture plates (Costar) were either induced to express mIκBα by doxycycline withdrawal or uninduced and either mock infected with phosphate-buffered saline or infected with reovirus T3D at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100 PFU per cell. After viral adsorption at room temperature for 1 h, fresh medium was added, and cells were incubated at 37°C for 10 h. Nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts were prepared as described previously (10). Cytoplasmic extracts (50 μg of total protein) were electrophoresed in sodium dodecyl sulfate-10% polyacrylamide gels (29) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes.

Immunoblotting was performed as previously described (42) using a rabbit polyclonal antiserum specific for IκBα (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), each diluted 1:1,000 in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween 20 and 5% lowfat dry milk.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays.

HeLa cells (7 × 106) grown in 100-cm tissue culture plates were either induced or uninduced and adsorbed with reovirus T3D at an MOI of 100 PFU per cell. After incubation at 37°C for 0, 2, 6, and 10 h postinfection, cells were lysed in hypotonic lysis buffer (10 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and protease inhibitor cocktail [Roche]) at 4°C for 15 min. A 1/20 volume of 10% Igepal CA-630 (Sigma Chemical Co.) was added to the cell lysate, and the sample was vortexed for 20 s and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 5 min. The nuclear pellet was washed once in hypotonic buffer, resuspended in high-salt buffer (25% glycerol, 20 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 0.42 M NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and protease inhibitor cocktail), and incubated at 4°C for 2 h. Samples were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min, and the supernatant was used as the nuclear extract.

Nuclear extracts (20 μg of total protein) were assayed for NF-κB activation by electrophoretic mobility shift assay using a 32P-labeled oligonucleotide probe (1.0 ng) consisting of the NF-κB consensus binding sequence (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) as described elsewhere (10). Nucleoprotein complexes were subjected to electrophoresis in native polyacrylamide gels, which were dried and exposed to film.

Quantitation of reovirus growth.

Induced or uninduced HeLa cells were grown in 24-well tissue culture plates (Costar) and infected with reovirus T3D at an MOI of 100 PFU per cell. After adsorption at room temperature for 1 h, 1.0 ml of fresh medium was added, and the cells were incubated at 37°C for 0, 12, 24, and 48 h. Following incubation, cells and culture medium were frozen (−70°C) and thawed twice, and viral titers in the cell lysates were determined by plaque assay using L cell monolayers (61).

Oligonucleotide probe-based microarrays.

HeLa cells (7 × 106) grown in 100-cm tissue culture plates were either induced or uninduced and adsorbed with reovirus T3D at an MOI of 100 PFU per cell. After incubation at 37°C for 0, 2, 6, and 10 h postinfection, cells were lysed and RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). Ten micrograms of total RNA was subjected to first-strand cDNA synthesis using a T7 RNA polymerase (dT)24 oligomer (5′-GGCCAGTGAATTGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGGCGG-dT24-3′) and SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies). Bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase was used to synthesize biotinylated cRNA according to the manufacturer's protocol (Enzo Diagnostics). The biotinylated target RNAs were fragmented to a mean size of 200 bases and hybridized to Hu95Av2 GeneChips (Affymetrix) containing 12,626 sequenced human genes according to the manufacturer's protocol. GeneChips were washed under both nonstringent (1 M NaCl, 25°C) and stringent (1 M NaCl, 50°C) conditions prior to staining with phycoerythrin-streptavidin (10 μg/ml final concentration). Arrays were scanned using a Gene Array scanner (Hewlett Packard) and analyzed using the GeneChip Analysis suite 5 software (Affymetrix). For each gene, 16 to 20 probe pairs were immobilized as ∼25-mer oligonucleotides that hybridize throughout the mRNA; each probe pair was represented as a perfect match oligonucleotide and a mismatch oligonucleotide as a hybridization control. The “detection” of a given mRNA (i.e., whether the mRNA is detected [“present”] or not [“absent”]) and the “signal” (i.e., measure of mRNA abundance) were determined as previously described (31).

Data analysis.

Two independent experiments were performed in which mRNA levels were compared by microarray analysis at 0, 2, 6, and 10 h following adsorption of induced and uninduced cells with either reovirus or gelatin saline as a mock infection control. For comparison of the fluorescence intensity (signal) values among multiple experiments, the signal values for each “experimental” GeneChip were scaled to those of the “base” GeneChip. This analysis was performed by first calculating the 2% trimmed mean (a measurement of global signal) for each GeneChip. The trimmed mean was obtained by calculating the mean signal of the chip after discarding the top and bottom 2% signal values (representing the “outliers”). Scaling was then performed by multiplying each of the signal measurements in the “experimental” array by a scaling factor defined as the ratio of the “base” trimmed mean to that of the “experimental” trimmed mean (the “base” array was defined to be the GeneChip for the zero-hour control mIκBα-induced cells). Because both reovirus infection and mIκBα induction (i.e., doxycycline withdrawal) can be considered experimental treatments, the scaled average difference values were subjected to a two-way analysis of variance with replications (ANOVA), as applied in the program Splus version 6 (Insightful), to identify genes that were significantly influenced by either reovirus infection or mIκBα induction.

Levels of gene expression were compared by hierarchical clustering following normalization of the average signal values by Z-score (57). The Z-score expresses the signal measurement of each gene during the course of treatment as a deviation from the mean in standard deviation units. For any cell, the Z-score is determined by the formula Z = (Si − Srow)/SD, where Srow is the average signal value for the gene (across the row) and SD is the standard deviation. Agglomerative hierarchical clustering was performed using the weighted pair-group method with arithmetic mean (Spotfire Array Explorer, version 8; Spotfire) using euclidean distance (5, 57).

Gene ontology analysis.

Gene ontology analysis was performed using the functional annotation tool of the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) 2.1 program (14). For each probe set, Gene Ontology:Biological Process (GO:BP) categories that were significantly overrepresented, as determined by the Fisher exact test (P < 0.05), were identified. The represented genes in GO:BP categories of interest were used for comparisons. For the reovirus-induced, NF-κB-dependent probe sets, identification of overrepresented GO:BP categories was verified using the NetAffx Analysis center (Affymetrix) (34).

Real-time PCR.

RNA was extracted from 1 × 106 cells using TRIzol reagent. Three micrograms of RNA was used in a reverse transcription reaction mixture containing 10× buffer, 25 mM MgCl2, 100 μM dithiothreitol, 1 U RNasin (Promega), 10 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 50 μM random hexamers, and 1 U avian myeloblastosis virus) reverse transcriptase (Promega). The reaction mixture was incubated at 43°C for 1 h and terminated at 95°C for 10 min.

Real-time PCRs were performed using the Bio-Rad icycler and IQ supermix buffer containing DNA polymerase and SYBR Green (Bio-Rad). Two to three replicate amplification reactions were performed in 96-well plates (Bio-Rad). Each reaction mixture contained 12.5 μl IQ supermix buffer, 300 nM forward and reverse primers, and 1 μl cDNA in a final volume of 25 μl. Primers for the reactions are shown in Table 1. Cycling conditions were as follows: 95°C for 10 min and then 45 cycles at 95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 15 s.

TABLE 1.

Primers used for quantitative PCR

| Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|

| IL-6 forward | 5′-AAAGAGGCACTGGCAGAAAA-3′ |

| IL-6 reverse | 5′-TTTCACCAGGCAAGTCTCCT-3′ |

| IRF-1 forward | 5′-GCAGCTCAAAAAGGGAAGTG-3′ |

| IRF-1 reverse | 5′-AAGGCAGGAGTCATGCAAGT-3′ |

| OAS1 (p40/46) forward | 5′-CAAGCTCAAGAGCCTCATCC-3′ |

| OAS1 (p40/46) reverse | 5′-GAGCTCCAGGGCATACTGAG-3′ |

| GAPDH forward | 5′-CAACTACATGGTCTACATGTTC-3′ |

| GAPDH reverse | 5′-CTCGCTCCTGGAAGATG-3′ |

Data analysis was performed using the Bio-Rad icycler PCR detection and analysis software, version 3.0 (Bio-Rad). DNA was quantified using the standard curve method with the background subtracted. Known concentrations of cDNA were used to obtain the standard curve for each gene (concentrations between 0.0228 and 710 ng). A melting curve was determined for each sample to detect primer dimers, in which case data were not used. Results are expressed as the ratio of target cDNA and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) cDNA.

RESULTS

NF-κB activation by reovirus is blocked in cells expressing mIκBα.

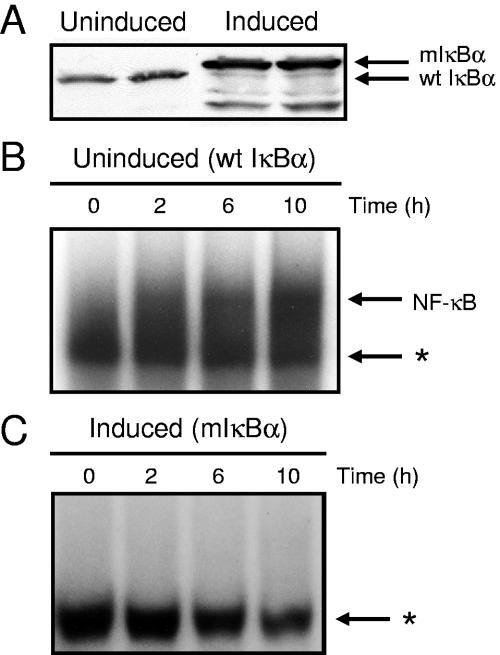

To investigate whether NF-κB activation by reovirus is altered in cells induced to express mIκBα, we first confirmed the expression of mIκBα by doxycycline withdrawal. HeLa cells were cultured for 7 days in either the presence (uninduced) or absence (induced) of doxycycline. Cytoplasmic extracts were prepared and analyzed by immunoblotting for mIκBα and endogenous wild-type (wt) IκBα (Fig. 1A). Immunoblot analysis confirmed the expression of mIκBα following doxycycline withdrawal, indicating that these cells are appropriate for studies of NF-κB activation by reovirus. The difference in relative molecular mass exhibited by wt IκBα and mIκBα reflects a FLAG epitope tag appended to the carboxy terminus of mIκBα (57).

FIG. 1.

IκBα expression and NF-κB activation in cells cultured in the presence and absence of doxycycline. (A) Expression of wt IκBα and mIκBα in the presence and absence of doxycycline. Cytoplasmic extracts were prepared at 7 days after either culture with doxycycline (uninduced) or doxycycline deprivation (induced). Extracts were subjected to immunoblotting using an IκBα-specific antiserum. (B and C) Time course of NF-κB gel shift activity in nuclear extracts prepared from reovirus-infected HeLa cells cultured in the presence (B) and absence (C) of doxycycline. Cells (5 × 106) were either uninduced or induced, infected with reovirus T3D at an MOI of 100 PFU per cell, and incubated at 37°C for the times shown. Nuclear extracts were prepared and incubated with a 32P-labeled oligonucleotide consisting of the NF-κB consensus binding sequence. Incubation mixtures were resolved by acrylamide gel electrophoresis, dried, and exposed to film. NF-κB-containing complexes are indicated. *, nonspecific band.

To determine whether expression of mIκBα is capable of blocking the NF-κB response elicited by reovirus, either uninduced or induced cells were infected with reovirus strain T3D, and nuclear extracts were prepared at 0, 2, 6, and 10 h postinfection. Extracts were incubated with a 32P-labeled oligonucleotide probe consisting of an NF-κB consensus binding sequence and resolved in nondenaturing polyacrylamide gels (Fig. 1B and C). Following infection with reovirus, proteins capable of shifting the radiolabeled oligonucleotide to a higher relative molecular mass were increased in nuclear extracts prepared from uninduced cells (Fig. 1B) in comparison to extracts prepared from cells expressing mIκBα (Fig. 1C). NF-κB activation was first detected at 2 h postinfection and increased at 6 and 10 h postinfection in uninduced cells (Fig. 1B). In contrast, little NF-κB activation was detected at any time point in cells induced to express mIκBα (Fig. 1C). These results demonstrate that reovirus stimulates nuclear translocation of NF-κB complexes in uninduced cells but not in cells expressing mIκBα.

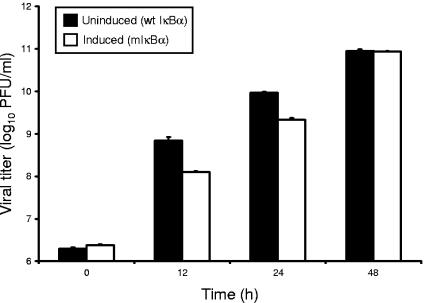

To determine whether the absence of NF-κB activation in HeLa cells expressing mIκBα is due to a failure of reovirus to productively infect these cells, uninduced and induced HeLa cells were infected with reovirus T3D, and viral titers were determined by plaque assay at 0, 12, 24, and 48 h postinfection (Fig. 2). Reovirus replicated efficiently in both uninduced and induced cells, although yields of progeny virus were greater in uninduced cells at 12 and 24 h of infection. By 48 h, viral yields in uninduced and induced cells were equivalent. Together with results presented in Fig. 1, these data indicate that mIκBα potently blocks NF-κB signaling in cells but does not abolish viral replication, validating the use of mIκBα-expressing cells for studies to assign NF-κB gene targets.

FIG. 2.

Growth of reovirus in HeLa cells cultured in the presence and absence of doxycycline. HeLa cells (1 × 105) were either uninduced or induced, infected with reovirus T3D at an MOI of 100 PFU per cell, and incubated at 37°C for the times shown. Viral titers were determined by plaque assay using L cells. The results are presented as the mean viral titers for three independent experiments. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

Identification of an NF-κB-dependent gene network in reovirus-infected cells.

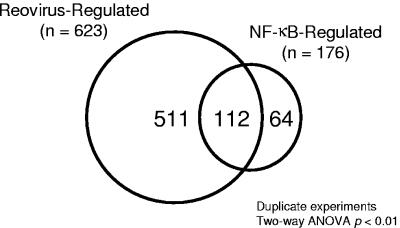

To identify gene expression profiles dependent on reovirus infection and NF-κB activation, mIκBα-expressing HeLa cells were cultured in the presence or absence of doxycycline for 7 days prior to infection with reovirus T3D. RNA was harvested from duplicate samples of mock-infected and reovirus-infected cells at 0, 2, 6, and 10 h postinfection (Fig. 1B). Gene expression changes were detected by using high-density oligonucleotide microarrays containing oligonucleotides corresponding to approximately 12,696 sequenced human genes (Affymetrix Hu95A GeneChip). Two-way ANOVA was used to identify changes in expression levels that were significantly altered (P < 0.01) following reovirus infection. In these experiments, reovirus infection significantly influenced the expression of 623 mRNAs represented on the GeneChip (Fig. 3). Induction of mIκBα significantly changed the expression of 176 mRNAs. Comparison of the two expression profile groups revealed that there were 112 genes common to both reovirus infection and NF-κB activation (Fig. 3 and Table 2). Since the expression of these 112 genes is dependent on both reovirus and NF-κB, these genes were chosen for further analysis.

FIG. 3.

Cellular genes regulated by reovirus and NF-κB. Two-way ANOVA of scaled signal intensities was used to identify genes regulated by either reovirus infection or mIκBα expression. Probe sets with a P value of <0.01 by either treatment were selected for further analysis. Shown is a Venn diagram of genes common to both data sets. Of the 623 genes regulated by reovirus, 112 also are under NF-κB control.

TABLE 2.

Expression profiles of reovirus-regulated genesa

| Cluster and gene symbol | GenBank accession no. | Mean scaled avg difference

|

Pr(F)

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NF-κB intact (+Dox)

|

NF-κB inhibited (−Dox)

|

NF-κB (+Dox) | Reovirus | ||||||||

| 0 h | 2 h | 6 h | 10 h | 0 h | 2 h | 6 h | 10 h | ||||

| Cluster I | |||||||||||

| POLD1 | M80397 | 80 | 67 | 67 | 62 | 802 | 73 | 69 | 77 | 4.81E-08 | 5.73E-09 |

| CGA | S70585 | 6,909 | 8,097 | 6,852 | 6,705 | 8,215 | 9,129 | 8,553 | 8,277 | 6.00E-07 | 1.43E-04 |

| MFAP2 | U19718 | 4,730 | 4,359 | 3,853 | 3,466 | 6,048 | 5,222 | 4,759 | 4,718 | 7.00E-07 | 1.10E-05 |

| SLC9A8 | AL031685 | 80 | 67 | 67 | 62 | 233 | 73 | 69 | 77 | 1.65E-05 | 2.46E-06 |

| HR | W27191 | 80 | 67 | 67 | 62 | 269 | 73 | 69 | 77 | 1.94E-05 | 2.86E-06 |

| BAPX1 | AF009801 | 352 | 227 | 269 | 243 | 438 | 311 | 342 | 396 | 9.46E-05 | 1.30E-03 |

| ERCC4 | L76568 | 80 | 67 | 67 | 62 | 76 | 304 | 69 | 77 | 4.93E-04 | 1.74E-04 |

| POU6F1 | Z21966 | 80 | 67 | 67 | 62 | 93 | 165 | 69 | 77 | 1.02E-03 | 2.39E-03 |

| LMO1 | M26682 | 554 | 309 | 335 | 384 | 916 | 390 | 419 | 481 | 1.09E-03 | 8.32E-05 |

| INSIG1 | U96876 | 373 | 372 | 184 | 190 | 558 | 484 | 184 | 333 | 1.11E-03 | 5.14E-05 |

| RAB5B | X54871 | 479 | 394 | 353 | 342 | 564 | 487 | 395 | 507 | 1.46E-03 | 5.88E-03 |

| ARL3 | AF038193 | 80 | 67 | 67 | 62 | 179 | 73 | 69 | 77 | 1.83E-03 | 4.41E-04 |

| HBP1 | AF019214 | 299 | 265 | 124 | 186 | 419 | 283 | 148 | 189 | 2.17E-03 | 6.93E-07 |

| PPP1R3C | N36638 | 242 | 308 | 228 | 184 | 334 | 474 | 263 | 244 | 2.18E-03 | 1.22E-03 |

| ACADS | Z80345 | 80 | 67 | 67 | 62 | 234 | 73 | 106 | 77 | 2.37E-03 | 2.96E-03 |

| CLK3 | L29217 | 388 | 282 | 262 | 283 | 354 | 290 | 69 | 242 | 2.85E-03 | 1.00E-04 |

| RABGGTA | Y08200 | 389 | 365 | 380 | 404 | 405 | 373 | 69 | 372 | 2.99E-03 | 6.17E-04 |

| IL10RB | AI984234 | 458 | 404 | 408 | 397 | 643 | 537 | 415 | 450 | 3.06E-03 | 9.20E-03 |

| FOS | V01512 | 928 | 1,283 | 778 | 156 | 1,018 | 1,972 | 853 | 263 | 3.12E-03 | 1.02E-06 |

| MTUS1 | AL096842 | 392 | 310 | 268 | 315 | 513 | 419 | 291 | 392 | 6.13E-03 | 4.27E-03 |

| ARMC6 | AC003038 | 697 | 675 | 67 | 62 | 330 | 73 | 69 | 77 | 6.65E-03 | 2.70E-03 |

| SMAD2 | U68018 | 671 | 852 | 688 | 735 | 814 | 962 | 702 | 851 | 7.99E-03 | 3.14E-03 |

| LAMA4 | S78569 | 118 | 97 | 79 | 79 | 176 | 134 | 98 | 98 | 8.02E-03 | 7.02E-03 |

| CLDN7 | AJ011497 | 245 | 185 | 146 | 152 | 286 | 225 | 180 | 229 | 8.11E-03 | 4.25E-03 |

| DDR1 | L20817 | 381 | 378 | 330 | 248 | 477 | 445 | 294 | 341 | 8.37E-03 | 5.99E-04 |

| HTRA1 | D87258 | 1,510 | 1,404 | 1,194 | 950 | 1,776 | 1,822 | 1,289 | 1,369 | 9.24E-03 | 8.39E-03 |

| NOTCH3 | U97669 | 708 | 474 | 383 | 320 | 815 | 692 | 417 | 463 | 9.53E-03 | 3.03E-04 |

| CHES1 | U68723 | 364 | 301 | 308 | 330 | 508 | 355 | 319 | 383 | 9.54E-03 | 8.58E-03 |

| HYAL1 | U03056 | 370 | 224 | 148 | 124 | 443 | 243 | 133 | 181 | 9.90E-03 | 2.10E-07 |

| Cluster II (kinetic class 3) | |||||||||||

| IRF1 | L05072 | 80 | 67 | 619 | 664 | 76 | 73 | 69 | 77 | 8.10E-11 | 7.18E-10 |

| OAS1 (p40/46) | X04371 | 80 | 67 | 67 | 846 | 76 | 73 | 69 | 77 | 1.76E-10 | 1.69E-11 |

| TNIP1 | AJ011896 | 80 | 67 | 1,138 | 1,290 | 76 | 73 | 69 | 77 | 9.47E-08 | 8.07E-07 |

| G1P2 | AA203213 | 79.5 | 194 | 661 | 3,472 | 76 | 73 | 553 | 1,620 | 3.03E-07 | 1.79E-11 |

| CCL5 | M21121 | 80 | 67 | 267 | 692 | 76 | 73 | 69 | 225 | 2.45E-06 | 1.46E-07 |

| IRF7 | U53831 | 80 | 67 | 67 | 631 | 76 | 73 | 69 | 183 | 3.88E-06 | 1.88E-08 |

| G1P3 | U22970 | 80 | 67 | 67 | 1,260 | 76 | 73 | 69 | 406 | 5.97E-06 | 7.80E-09 |

| STAT1 | M97936 | 261 | 265 | 391 | 1,457 | 301 | 264 | 303 | 443 | 1.75E-05 | 1.75E-06 |

| MX2 | M30818 | 80 | 67 | 67 | 236 | 76 | 73 | 69 | 75 | 4.15E-05 | 3.44E-06 |

| IFIT1 | M24594 | 110 | 98 | 1,090 | 7,793 | 99 | 99 | 864 | 3,164 | 6.20E-05 | 2.59E-08 |

| STAT2 | U18671 | 80 | 67 | 67 | 219 | 76 | 73 | 69 | 77 | 6.92E-05 | 4.37E-06 |

| OGFR | AF109134 | 1,545 | 1,636 | 1,543 | 3,024 | 1,385 | 1,329 | 1,140 | 1,485 | 1.09E-04 | 2.43E-04 |

| FXYD2 | H94881 | 80 | 67 | 67 | 62 | 76 | 73 | 69 | 187 | 1.26E-04 | 8.51E-05 |

| CXCL10 | X02530 | 80 | 67 | 62 | 226 | 76 | 73 | 69 | 77 | 1.54E-04 | 7.62E-06 |

| EBNA1BP2 | U86602 | 2,599 | 2,573 | 2,757 | 3,066 | 2,216 | 2,306 | 2,384 | 2,536 | 1.56E-04 | 5.24E-03 |

| PLSCR1 | AB006746 | 719 | 781 | 1,142 | 3,321 | 715 | 718 | 697 | 1,024 | 1.61E-04 | 2.75E-05 |

| CXCL11 | AF030514 | 80 | 67 | 90 | 437 | 76 | 73 | 69 | 80 | 1.92E-04 | 3.65E-05 |

| BF | L15702 | 80 | 67 | 365 | 415 | 76 | 73 | 69 | 77 | 3.28E-04 | 2.40E-03 |

| IFIT5 | U34605 | 140 | 163 | 206 | 452 | 162 | 134 | 181 | 229 | 3.53E-04 | 4.08E-06 |

| OASL (p59) | AJ225089 | 80 | 237 | 2,092 | 11,230 | 76 | 148 | 1,646 | 6,298 | 5.01E-04 | 1.82E-08 |

| NMI | U32849 | 578 | 446 | 497 | 954 | 495 | 468 | 388 | 504 | 6.54E-04 | 3.80E-04 |

| SP110 | L22342 | 80 | 67 | 67 | 413 | 76 | 73 | 69 | 77 | 8.88E-04 | 1.21E-04 |

| TDRD7 | AB025254 | 80 | 67 | 99 | 396 | 76 | 73 | 69 | 121 | 9.74E-04 | 4.87E-05 |

| FLJ38348 | AL047596 | 208 | 217 | 323 | 817 | 261 | 230 | 265 | 352 | 1.87E-03 | 2.16E-05 |

| TAP1 | X57522 | 434 | 332 | 554 | 916 | 316 | 290 | 406 | 415 | 1.93E-03 | 2.42E-03 |

| IFITM1 | J04164 | 1,730 | 1,477 | 1,376 | 4,210 | 1,641 | 1,524 | 1,202 | 1,451 | 2.31E-03 | 8.63E-04 |

| TUBB4 | U47634 | 3,747 | 3,720 | 3,899 | 4,407 | 2,979 | 3,247 | 3,409 | 3,942 | 2.69E-03 | 9.33E-03 |

| PML | M82827 | 174 | 67 | 163 | 817 | 76 | 73 | 69 | 77 | 2.80E-03 | 4.24E-03 |

| PODXL | U97519 | 887 | 881 | 1,224 | 1,259 | 805 | 752 | 987 | 1,019 | 3.29E-03 | 8.79E-04 |

| IL15 | AF031167 | 148 | 138 | 274 | 330 | 168 | 144 | 212 | 155 | 3.84E-03 | 7.45E-04 |

| PTGES | AF010316 | 427 | 879 | 1,145 | 1,148 | 76 | 73 | 846 | 1,060 | 4.30E-03 | 7.21E-04 |

| TRIM21 | M62800 | 160 | 176 | 231 | 795 | 223 | 174 | 115 | 231 | 4.83E-03 | 7.46E-04 |

| RAD51C | AF029669 | 307 | 205 | 234 | 179 | 262 | 164 | 144 | 176 | 6.85E-03 | 8.24E-04 |

| IFI16 | M63838 | 618 | 469 | 417 | 1,565 | 517 | 504 | 370 | 524 | 7.21E-03 | 1.97E-03 |

| HEG1 | W28612 | 861 | 949 | 1,452 | 1,690 | 732 | 956 | 1,143 | 1,173 | 7.66E-03 | 5.03E-04 |

| IFIT2 | M14660 | 80 | 67 | 562 | 4,647 | 76 | 73 | 681 | 2,518 | 7.73E-03 | 2.97E-07 |

| DPH2 | AF053003 | 964 | 1,061 | 1,201 | 1,229 | 912 | 929 | 1,127 | 1,079 | 8.63E-03 | 1.22E-03 |

| GSTM3 | J05459 | 458 | 340 | 418 | 348 | 345 | 73 | 423 | 384 | 8.90E-03 | 1.04E-03 |

| ANXA3 | M20560 | 311 | 352 | 546 | 683 | 205 | 233 | 447 | 475 | 9.01E-03 | 9.48E-04 |

| LHFPL2 | D86961 | 522 | 414 | 553 | 582 | 591 | 474 | 576 | 615 | 9.30E-03 | 2.10E-04 |

| UBC | AB009010 | 4,699 | 4,354 | 4,769 | 5,500 | 5,370 | 4,746 | 5,423 | 5,881 | 9.33E-03 | 5.68E-03 |

| IFI44 | D28915 | 170 | 211 | 758 | 2,453 | 156 | 162 | 618 | 1,452 | 9.84E-03 | 1.81E-06 |

| Cluster III (kinetic class 1) | |||||||||||

| IL6 | X04430 | 80 | 1,222 | 1,116 | 759 | 76 | 355 | 235 | 180 | 2.44E-08 | 3.85E-07 |

| CXCL2 | M36820 | 46 | 395 | 205 | 204 | 76 | 139 | 105 | 79 | 5.01E-07 | 5.68E-07 |

| PLK3 | U56998 | 80 | 869 | 67 | 62 | 76 | 73 | 69 | 77 | 1.35E-06 | 1.41E-07 |

| TNFAIP3 | M59465 | 132 | 742 | 588 | 380 | 91 | 350 | 190 | 183 | 7.00E-06 | 1.25E-05 |

| PSMB9 | AA808961 | 370 | 318 | 321 | 646 | 268 | 218 | 221 | 199 | 1.47E-05 | 1.99E-03 |

| NFKBIA | M69043 | 706 | 2,079 | 1,664 | 1,126 | 717 | 1,340 | 953 | 627 | 1.04E-04 | 2.77E-05 |

| IL8 | M28130 | 80 | 1,866 | 580 | 62 | 76 | 421 | 69 | 77 | 2.61E-04 | 3.12E-05 |

| CXCL1 | X54489 | 117 | 615 | 341 | 162 | 76 | 351 | 69 | 77 | 3.67E-04 | 3.71E-05 |

| GADD45A | M60974 | 362 | 687 | 563 | 430 | 392 | 538 | 422 | 398 | 3.93E-04 | 4.73E-06 |

| NFKB1 | M58603 | 2,747 | 3,708 | 4,029 | 3,044 | 2,836 | 2,802 | 2,908 | 2,515 | 5.40E-04 | 5.02E-03 |

| IFNGR1 | U19247 | 297 | 479 | 480 | 362 | 282 | 372 | 321 | 234 | 5.83E-04 | 1.48E-03 |

| CCND1 | M64349 | 1,097 | 1,339 | 1,452 | 917 | 1,009 | 1,106 | 946 | 800 | 5.89E-04 | 1.17E-03 |

| PLK2 | AF059617 | 68 | 736 | 382 | 185 | 76 | 419 | 198 | 125 | 7.35E-04 | 3.84E-06 |

| IFITM3 | X57352 | 9,310 | 9,027 | 8,522 | 15,241 | 7,661 | 6,352 | 7,720 | 8,288 | 9.43E-04 | 4.63E-03 |

| TNFAIP2 | M92357 | 1,029 | 1,560 | 1,619 | 880 | 943 | 1,252 | 1,028 | 822 | 1.11E-03 | 1.90E-04 |

| PLAUR | U09937 | 1,112 | 2,347 | 1,785 | 2,146 | 1,028 | 2,106 | 1,644 | 1,529 | 1.74E-03 | 5.26E-06 |

| JUNB | M29039 | 573 | 1,466 | 1,031 | 772 | 589 | 1,175 | 918 | 456 | 1.94E-03 | 2.68E-06 |

| IL4R | X52425 | 168 | 365 | 360 | 192 | 148 | 274 | 224 | 100 | 2.47E-03 | 3.57E-04 |

| TNFAIP8 | AF099935 | 526 | 729 | 675 | 534 | 553 | 625 | 479 | 502 | 2.65E-03 | 9.96E-04 |

| RND3 | S82240 | 282 | 677 | 427 | 489 | 244 | 583 | 309 | 348 | 3.55E-03 | 3.15E-05 |

| PTPN1 | M93425 | 740 | 1,183 | 843 | 664 | 682 | 1,016 | 560 | 562 | 4.09E-03 | 8.53E-05 |

| EPHA2 | M59371 | 300 | 1,192 | 810 | 329 | 248 | 886 | 511 | 193 | 4.50E-03 | 1.26E-05 |

| PSCD1 | M85169 | 243 | 483 | 344 | 244 | 198 | 402 | 196 | 262 | 5.93E-03 | 7.12E-05 |

| IER3 | S81914 | 568 | 1,976 | 847 | 448 | 621 | 1,569 | 584 | 385 | 6.79E-03 | 1.40E-07 |

| ID1 | X77956 | 5,708 | 15,703 | 10,646 | 8,703 | 5,801 | 14,940 | 9,909 | 6,742 | 7.40E-03 | 1.00E-08 |

| BCAR3 | U92715 | 295 | 726 | 587 | 303 | 239 | 686 | 370 | 270 | 8.29E-03 | 4.96E-06 |

| AMIGO2 | AC004010 | 172 | 698 | 483 | 286 | 152 | 633 | 385 | 237 | 8.84E-03 | 1.00E-07 |

| CEBPD | M83667 | 577 | 1,440 | 903 | 931 | 557 | 1,202 | 611 | 660 | 8.89E-03 | 1.18E-04 |

| Cluster IV (kinetic class 2) | |||||||||||

| PLAU | X02419 | 296 | 902 | 1,034 | 586 | 254 | 707 | 705 | 412 | 1.06E-06 | 5.40E-09 |

| NFKB2 | U20816 | 80 | 306 | 431 | 328 | 76 | 73 | 69 | 77 | 1.74E-06 | 6.60E-04 |

| RHOB | M12174 | 652 | 1,257 | 1,242 | 1,605 | 903 | 1,522 | 1,957 | 1,839 | 3.65E-05 | 1.80E-06 |

| RELB | M83221 | 80 | 421 | 623 | 422 | 76 | 203 | 69 | 77 | 1.23E-04 | 6.86E-03 |

| SDC4 | D79206 | 169 | 524 | 672 | 503 | 202 | 431 | 353 | 251 | 5.10E-04 | 1.53E-04 |

| MAFF | AL021977 | 80 | 370 | 131 | 65 | 76 | 187 | 79 | 77 | 9.11E-04 | 2.80E-06 |

| TRIM16 | AF096870 | 729 | 1,163 | 1,908 | 1,686 | 767 | 832 | 1,161 | 1,022 | 3.43E-03 | 2.80E-03 |

| GALNT1 | U41514 | 355 | 418 | 444 | 424 | 333 | 359 | 365 | 403 | 3.57E-03 | 9.82E-03 |

| OSMR | U60805 | 323 | 540 | 597 | 552 | 340 | 473 | 481 | 362 | 3.89E-03 | 8.06E-04 |

| JUN | J04111 | 116 | 182 | 171 | 140 | 89 | 250 | 209 | 157 | 4.13E-03 | 4.81E-06 |

| TXNRD1 | X91247 | 3,421 | 4,352 | 5,620 | 4,496 | 3,151 | 4,230 | 4,786 | 3,948 | 4.67E-03 | 2.00E-05 |

| BIRC2 | U37547 | 251 | 443 | 548 | 474 | 249 | 392 | 391 | 359 | 7.50E-03 | 7.38E-04 |

| NPR3 | M59305 | 586 | 787 | 861 | 835 | 744 | 832 | 885 | 973 | 8.85E-03 | 1.00E-03 |

Shown are reovirus-responsive, NF-κB-dependent genes identified in the microarray analysis, categorized by gene cluster and kinetic class. The gene symbol, GenBank accession number, mean scaled average difference values for each treatment condition, and the P value [Pr(F)] as a function of either NF-κB signaling or reovirus infection are shown for each gene identified. Dox, doxycycline. Within each cluster, genes are listed according to statistical significance for NF-κB dependence.

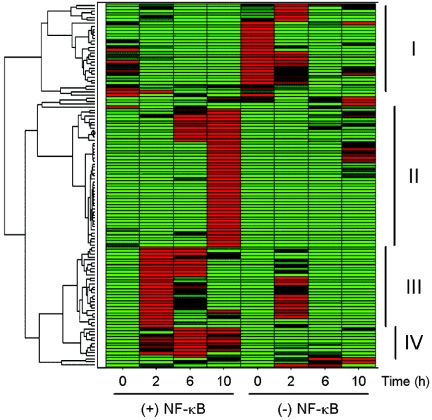

Identification of distinct expression patterns of NF-κB-regulated genes in response to reovirus infection.

To characterize gene expression profiles that are dependent on both reovirus infection and NF-κB activation and to determine whether NF-κB gene expression is temporally regulated during reovirus infection, we used a hierarchical clustering algorithm to define the relationship of genes of interest (64). Each gene expression profile was grouped with its nearest neighbor, and the mathematical proximity of each expression profile to that of the others was defined. The hierarchical clustering of 112 genes with expression patterns dependent on both reovirus and NF-κB is shown in Fig. 4, with the data visually presented using a color-coded scale. Inspection of the dendrogram reveals four distinct gene clusters with expression patterns that are dependent on the time of infection. The second, third, and fourth clusters include genes that are induced by reovirus and blocked by expression of mIκBα. In general, genes in cluster III were maximally expressed 2 h postinfection (kinetic class 1), genes in cluster IV were expressed 6 h postinfection (kinetic class 2), and genes in cluster II were expressed 10 h postinfection (kinetic class 3). Cluster I includes genes with low-level expression in uninduced cells that are enhanced by expression of mIκBα. These genes appear to be constitutively regulated by NF-κB. We conclude that distinct groups of NF-κB-dependent genes are induced by reovirus at distinct times during infection.

FIG. 4.

Hierarchical clustering of mRNA expression profiles. The signal intensities of probe sets were normalized by Z-score and subjected to hierarchical clustering. Data are represented as a heat map, where each row represents a different probe set. At each time point, the calculated Z-score is shown by a color code in which red represents a Z of >+1.2, green represents a Z of <−1.2, and black represents a Z of 0. The treatment conditions are indicated at the bottom of the figure. Shown at the left is a dendrogram indicating the mathematical relationship of the expression profiles. Genes with similar expression profiles are grouped together and connected by a short line that connects the two nodes. Four major clusters are evident, labeled I to IV, at the right.

NF-κB-regulated genes induced by reovirus belong to distinct functional classes.

To determine whether reovirus-responsive genes under NF-κB control can be grouped into functional classes, we used the functional annotation tool of the DAVID program. Biological processes in each kinetic class that were statistically overrepresented by the Fisher exact test (P < 0.05) were identified. Biological processes overrepresented in kinetic class 1 include cell proliferation, taxis, apoptosis, and response to pest, pathogen, or parasite. Taxis and response to pest, pathogen, or parasite also were represented in kinetic class 3, along with the Janus-activated kinase (JAK) signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) cascade and response to virus. No overrepresented biological processes were identified in kinetic class 2. Thus, distinct classes of genes under NF-κB control are activated following reovirus infection.

Confirmation of microarray analysis by real-time PCR.

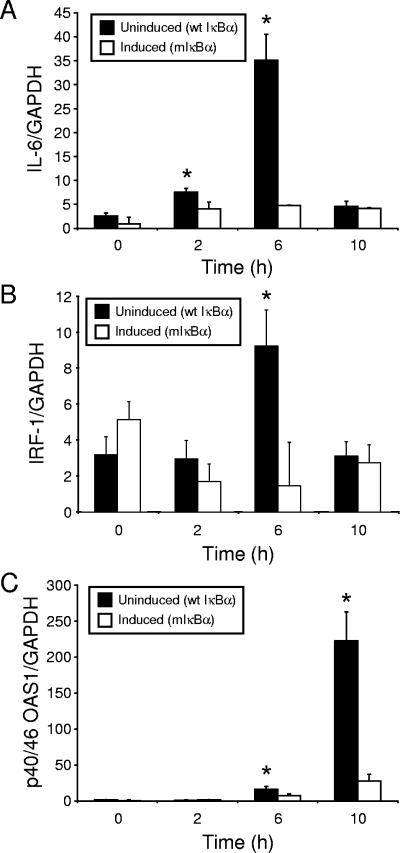

To confirm the temporal expression pattern of NF-κB-responsive genes identified in the microarray analysis, we used real-time PCR to define the expression levels of single genes during the interval of reovirus infection employed in the microarray experiments. Either uninduced or induced HeLa cells were infected with reovirus T3D, and RNA was harvested at 0, 2, 6, and 10 h postinfection. Following reverse transcription, resultant cDNAs were used in real-time PCRs to detect levels of interleukin-6 (IL-6), IRF-1, and p40/46 OAS1 mRNA (Fig. 5). The results demonstrated that these genes are upregulated following reovirus infection in an NF-κB-dependent manner with kinetics that parallel the microarray results.

FIG. 5.

Levels of mRNAs corresponding to reovirus-responsive, NF-κB-dependent genes in cells expressing mIκBα and cells expressing wild-type IκBα. HeLa cells were either uninduced or induced and infected with reovirus T3D at an MOI of 100 PFU per cell. At 0, 2, 6, and 10 h postinfection, RNA was extracted and used as a template to generate cDNA. Levels of (A) IL-6, (B) IRF-1, (C) p40/46 OAS1, and GAPDH mRNA were quantified by real-time PCR. The results are expressed as a ratio of target cDNA to GAPDH cDNA. Shown are the mean ratios of two independent experiments performed in duplicate. Error bars indicate standard deviations. *, P < 0.05 by t test in comparison to induced cells at each time point.

DISCUSSION

Apoptotic cell death is the primary mechanism of reovirus-induced tissue injury in the murine CNS (38, 39) and heart (11, 13). Emerging mechanistic evidence indicates that transcription factor NF-κB plays an important role in the present death response (2, 8, 10, 39). However, until the present study, the underlying genetic program elicited by NF-κB activation in reovirus-infected cells remained unknown. To identify the relevant NF-κB-responsive genes, we monitored gene expression profiles in mammalian cells engineered to express a degradation-resistant mutant of IκBα (57). NF-κB-dependent alterations in the expression of 112 genes were observed following reovirus infection. This set of genes includes several members that have been linked to apoptosis, including STAT1, GADD45A, and RhoB (32, 46, 58).

Our gene profiling studies revealed a wide spectrum of reovirus-inducible genes under NF-κB control, including those encoding cytokines, transcription factors, cell cycle regulators, and enzymes (Table 2). Cytokine and cell proliferation genes were expressed at 2 h postinfection, NF-κB family members were expressed at 6 h postinfection, and ISGs were expressed at 10 h postinfection. These findings suggest that distinct gene clusters are temporally regulated following infection with reovirus. Genes encoding cytokines (e.g., IL-6, IL-8, CXCL1/GROα, and CXCL2/MIP-2α) were among the most rapidly expressed, which likely reflects their involvement in the activation of downstream signaling pathways for innate immunity. Thus, some of the NF-κB response genes identified in our study may be secondarily dependent on signaling pathways triggered by cytokines secreted early in the reovirus infectious cycle.

Innate immunity plays an important role in host defense by limiting viral replication and facilitating development of an adaptive immune response (4). Modification of the NF-κB signaling pathway by viruses is a common mechanism to enhance viral replication, manipulate host immunity, influence cell growth, and determine cell fate (1, 25). Following viral infection, NF-κB activation elicits innate immune responses by the production of IFN-α/β, which function as potent antiviral cytokines (44). Secreted IFN-α/β act in a paracrine manner to produce an antiviral state in uninfected cells through activation of the JAK-STAT signal transduction pathway (44). Based on the microarray data in this report, indicating that ISGs are induced in an NF-κB-dependent fashion following reovirus infection, we conclude that reovirus-induced activation of NF-κB has potent stimulatory effects on mechanisms of innate immunity.

Many of the biological effects of IFN-α/β and other IFNs are mediated by ISGs (48), which have been previously implicated in cell death signaling (24). STAT-1 is activated upon IFN binding to its receptor, and it forms a complex with STAT-2/p48 (ISGF3) to induce transcription (26). IFN regulatory factor 1 (IRF-1) is a target for STAT-1 transcriptional regulation (41), and IRF-1 itself transcriptionally regulates additional ISGs and promotes apoptosis following DNA damage (23, 51, 53). IFN-α/β can greatly enhance the apoptotic response of cultured cells to double-stranded RNA and influenza virus (54). In this regard, Tanaka et al. (54) have proposed that only virus-infected cells producing IFN undergo apoptosis following viral infection (54). According to this model, IFN induces cytotoxicity of infected cells via an autocrine pathway, whereas uninfected cells enter an antiviral state via a paracrine mode of IFN action (54). Of note, we found that NF-κB activation by reovirus leads to expression of STAT-1, STAT-2, and IRF-1 (Tables 2 and 3). This finding raises the possibility that reovirus induces apoptosis as a consequence of NF-κB-mediated stimulation of ISGs.

TABLE 3.

Host defense response genes induced by reovirusa

| Class and gene symbol | GenBank accession no. | Avg fold increase

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 h | 2 h | 6 h | 10 h | ||

| Kinetic class 1 | |||||

| CXCL1 | X54489 | 1.54 | 1.75 | 4.98 | 2.10 |

| CXCL2 | M36820 | 0.61 | 2.84 | 1.96 | 2.57 |

| IFITM3 | X57352 | 1.22 | 1.42 | 1.1 | 1.84 |

| IL4R | X52425 | 1.14 | 1.33 | 1.60 | 1.91 |

| IL6 | X04430 | 1.05 | 3.45 | 4.75 | 4.21 |

| IL8 | M28130 | 1.05 | 4.43 | 8.46 | 0.80 |

| NFKB1 | M58603 | 0.97 | 1.32 | 1.38 | 1.21 |

| Kinetic class 3 | |||||

| PSMB9 | AA808961 | 1.38 | 1.46 | 1.45 | 3.24 |

| BF | L15702 | 1.04 | 0.91 | 5.35 | 5.38 |

| CCL5 | M21121 | 1.04 | 0.91 | 3.92 | 3.07 |

| CXCL10 | X02530 | 1.05 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 2.93 |

| CXCL11 | AF030514 | 1.05 | 0.91 | 1.31 | 5.45 |

| G1P2 | AA203213 | 1.05 | 2.65 | 1.2 | 2.14 |

| G1P3 | U22970 | 1.05 | 0.91 | 0.98 | 3.11 |

| IFI16 | M63838 | 1.2 | 0.93 | 1.13 | 2.99 |

| IFIT1 | M24594 | 1.78 | 1.04 | 1.1 | 3.14 |

| IFIT2 | M14660 | 1.05 | 0.91 | 0.83 | 1.85 |

| IFIT5 | U34605 | 0.86 | 1.22 | 1.13 | 1.97 |

| IFITM1 | J04164 | 1.05 | 0.97 | 1.14 | 2.90 |

| IL15 | AF031167 | 0.87 | 0.95 | 1.29 | 2.12 |

| IRF1 | L05072 | 1.05 | 0.91 | 9.04 | 8.62 |

| IRF7 | U53831 | 1.05 | 0.91 | 0.98 | 3.44 |

| MX2 | M30818 | 1.05 | 0.91 | 0.98 | 3.15 |

| NMI | U32849 | 1.17 | 0.91 | 1.28 | 1.89 |

| OAS1 p40/46 | X04371 | 1.05 | 0.91 | 0.98 | 10.98 |

| OASL p59 | AJ225089 | 1.05 | 1.6 | 1.27 | 1.78 |

| PTGES | AF010316 | 5.6 | 12.02 | 1.35 | 1.08 |

| TAP1 | X57522 | 1.37 | 1.14 | 1.36 | 2.21 |

Shown is a subset of reovirus-responsive, NF-κB-dependent genes identified in the microarray analysis that are categorized as defense response by the DAVID program (14). Genes are listed alphabetically by kinetic class. Average fold change is expressed as a ratio of mRNA levels in uninduced cells (+doxycycline) divided by mRNA levels in induced cells (−doxycycline) at the indicated times after infection. Values less than 1 represent a decrease in expression.

In addition to the NF-κB-dependent innate immune response, reovirus infection induces expression of genes in other proapoptotic pathways, through both NF-κB-dependent (e.g., GADD45A [58] and RhoB [33]) and NF-κB-independent (e.g., TP53BP2/ASPP2 and PPP1R13B/ASPP1 [43]) mechanisms. GADD45A, RhoB, TP53BP2, and PPP1R13B have been implicated in the cellular response to DNA damage initiated by the p53 tumor suppressor (28, 35, 47). It is noteworthy that genes in the DNA damage response pathway are overrepresented among reovirus-regulated genes identified in this and a previous microarray study (12). DNA damage response genes identified in both studies include GADD45A, DDB2, ERCC4, FUS, and IRF-7. The pathological relationship between reovirus infection, NF-κB activation, and the cellular response to DNA damage, if any, remains unclear. However, there is evidence for significant interactions between the NF-κB and p53 pathways (15, 63), which may be operative in reovirus-infected cells. In support of this possibility, we identified two NF-κB-responsive genes in kinetic class 1 that have been previously implicated in the regulation of p53-mediated apoptosis (PLK3 and IER3/IEX-1) (30). In addition to regulating genes in the p53-mediated apoptotic pathway, reovirus infection regulates several genes involved in mitochondrial injury pathways, including MCL1 (3), PAWR/Par-4 (21), BNIP3L (27), and MOAP1 (52). However, NF-κB is not required for the regulation of these genes by reovirus, suggesting that these genes may function in concert with certain NF-κB-responsive genes to modulate the apoptotic response in reovirus-infected cells.

In prior studies, we observed decreased yields of reovirus following growth in cells lacking either the p50 or p65 NF-κB subunits in comparison to wt controls (10). Yields of reovirus in cells induced to express mIκBα were also lower than those in uninduced cells following 12 and 24 h of viral growth. Reovirus produces substantially greater yields following growth in rapidly dividing or transformed cells (16, 49, 55), suggesting that cellular factors associated with cell growth augment viral replication. It is possible that a subset of NF-κB-regulated genes promotes cell proliferation, which in turn enhances viral nucleic acid or protein synthesis, intracellular transport of viral proteins, or assembly and release of progeny virions. These genes include those that encode cell cycle proteins, such as PLK2 (36), and cytokines, such as CXCL1, CXCL10, IL-6, and IL-8.

NF-κB-dependent gene networks that are activated in response to a variety of other stimuli have been described, including respiratory syncytial virus (57), Epstein-Barr virus (6), tumor necrosis factor alpha (56), and heart disease (20). Gene ontology analysis of these data reveal significant representation of genes involved in cellular proliferation, apoptosis, signal transduction, taxis, and host defense responses (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). For example, upregulation of CCL5/RANTES, NFKBIA/IκBα, NFKB2/p49/p100, and TNFAIP3/A20 was observed in four of five studies, including this study, while NFKB1/p50/p105, CXCL1/GRO-α, IL-6, and IL-8 were observed in three of five studies. Several genes, including those encoding retinoic acid receptor-α, glomulin, and placental growth factor, were classified as NF-κB dependent in one study (57) but not in this study. These divergent results suggest that such genes can be differentially regulated via agonist-specific mechanisms. Alternatively, a requirement for NF-κB may be a function of the interval following stimulation or the cell type. The expression of NF-κB-dependent genes, including CCL5, IL-6, and TNFAIP3, in failing human hearts is of particular significance (20), as we have recently shown that NF-κB activation protects the heart from reovirus-induced apoptosis in vivo (39). It will therefore be of interest to examine the expression of these genes in the heart of neonatal mice during infection with myocarditic and nonmyocarditic reovirus strains.

NF-κB plays an essential role in the genetic response to a variety of cellular stresses (19). The extensive array of NF-κB inducers and target genes suggests that numerous mechanisms exist to direct transcription of appropriate NF-κB-responsive genes due to specific stimuli (40). Here, we have identified a network of genes activated by NF-κB following reovirus infection. Many of these genes function in innate immunity (Table 3), suggesting a critical role for this component of host defense in proapoptotic signaling. These genes may act in concert with genes involved in other proapoptotic pathways that reovirus regulates, including the DNA damage response and mitochondrial injury pathways. Data presented in this report establish the requisite genetic framework to address this potential interplay and to further dissect the pathological mechanisms of reovirus-induced apoptosis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jim Chappell, Pranav Danthi, and Mark Hansberger for careful review of the manuscript and Shawn Levy for assistance in the design of the microarray experiments.

This research was supported by Public Health Service awards T32 AI07474 (S.M.O.), T32 AI49824 (G.H.H.), R01 AI052379 (D.W.B), R01 AI50080 (T.S.D), the Vanderbilt University Medical Scholars Program (M.J.W.), and the Elizabeth B. Lamb Center for Pediatric Research. Additional support was provided by Public Health Service awards CA68485 for the Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center and DK20593 for the Vanderbilt Diabetes Research and Training Center.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jvi.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baldwin, A. S., Jr. 2001. The transcription factor NF-κB and human disease. J. Clin. Investig. 107:3-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barton, E. S., J. C. Forrest, J. L. Connolly, J. D. Chappell, Y. Liu, F. Schnell, A. Nusrat, C. A. Parkos, and T. S. Dermody. 2001. Junction adhesion molecule is a receptor for reovirus. Cell 104:441-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bingle, C. D., R. W. Craig, B. M. Swales, V. Singleton, P. Zhou, and M. K. B. Whyte. 2000. Exon skipping in Mcl-1 results in a Bcl-2 homology domain 3 only gene product that promotes cell death. J. Biol. Chem. 275:22136-22146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bose, S., and A. K. Banerjee. 2003. Innate immune response against nonsegmented negative strand RNA viruses. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 23:401-412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brasier, A. R., H. Spratt, Z. Wu, I. Boldogh, Y. Zhang, R. P. Garofalo, A. Casola, J. Pashmi, A. Haag, B. Luxon, and A. Kurosky. 2004. Nuclear heat shock response and novel nuclear domain 10 reorganization in respiratory syncytial virus-infected A549 cells identified by high-resolution two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. J. Virol. 78:11461-11476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cahir-McFarland, E. D., K. Carter, A. Rosenwald, J. M. Giltnane, S. E. Henrickson, L. M. Staudt, and E. Kieff. 2004. Role of NF-κB in cell survival and transcription of latent membrane protein 1-expressing or Epstein-Barr virus latency III-infected cells. J. Virol. 78:4108-4119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chappell, J. D., J. L. Duong, B. W. Wright, and T. S. Dermody. 2000. Identification of carbohydrate-binding domains in the attachment proteins of type 1 and type 3 reoviruses. J. Virol. 74:8472-8479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Connolly, J. L., E. S. Barton, and T. S. Dermody. 2001. Reovirus binding to cell surface sialic acid potentiates virus-induced apoptosis. J. Virol. 75:4029-4039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Connolly, J. L., and T. S. Dermody. 2002. Virion disassembly is required for apoptosis induced by reovirus. J. Virol. 76:1632-1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Connolly, J. L., S. E. Rodgers, P. Clarke, D. W. Ballard, L. D. Kerr, K. L. Tyler, and T. S. Dermody. 2000. Reovirus-induced apoptosis requires activation of transcription factor NF-κB. J. Virol. 74:2981-2989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeBiasi, R., C. Edelstein, B. Sherry, and K. Tyler. 2001. Calpain inhibition protects against virus-induced apoptotic myocardial injury. J. Virol. 75:351-361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeBiasi, R. L., P. Clarke, S. Meintzer, R. Jotte, B. K. Kleinschmidt-Demasters, G. L. Johnson, and K. L. Tyler. 2003. Reovirus-induced alteration in expression of apoptosis and DNA repair genes with potential roles in viral pathogenesis. J. Virol. 77:8934-8947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeBiasi, R. L., B. A. Robinson, B. Sherry, R. Bouchard, R. D. Brown, M. Rizeq, C. Long, and K. L. Tyler. 2004. Caspase inhibition protects against reovirus-induced myocardial injury in vitro and in vivo. J. Virol. 78:11040-11050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dennis, G., Jr., B. T. Sherman, D. A. Hosack, J. Yang, W. Gao, H. C. Lane, and R. A. Lempicki. 2003. DAVID: database for annotation, visualization, and integrated discovery. Genome Biol. 4:P3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dreyfus, D., M. Nagasawa, E. Gelfand, and L. Ghoda. 2005. Modulation of p53 activity by IκBα: evidence suggesting a common phylogeny between NF-κB and p53 transcription factors. BMC Immunol. 6:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duncan, M. R., S. M. Stanish, and D. C. Cox. 1978. Differential sensitivity of normal and transformed human cells to reovirus infection. J. Virol. 28:444-449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ehrlich, M., W. Boll, A. Van Oijen, R. Hariharan, K. Chandran, M. L. Nibert, and T. Kirchhausen. 2004. Endocytosis by random initiation and stabilization of clathrin-coated pits. Cell 118:591-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Furlong, D. B., M. L. Nibert, and B. N. Fields. 1988. Sigma 1 protein of mammalian reoviruses extends from the surfaces of viral particles. J. Virol. 62:246-256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilmore, T. D. 1999. The Rel/NF-κB signal transduction pathway: introduction. Oncogene 18:6842-6844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gupta, S., and S. Sen. 2005. Role of the NF-κB signaling cascade and NF-κB-targeted genes in failing human hearts. J. Mol. Med. [Online.] doi: 10.1007/s00109-005-0691-z. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Gurumurthy, S., A. Goswami, K. M. Vasudevan, and V. M. Rangnekar. 2005. Phosphorylation of Par-4 by protein kinase A is critical for apoptosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:1146-1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hayden, M. S., and S. Ghosh. 2004. Signaling to NF-κB. Genes Dev. 18:2195-2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Henderson, Y. C., M. Chou, and A. B. Deisseroth. 1997. Interferon regulatory factor 1 induces the expression of the interferon-stimulated genes. Br. J. Haematol. 96:566-575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hiscott, J., N. Grandvaux, S. Sharma, B. R. Tenoever, M. J. Servant, and R. Lin. 2003. Convergence of the NF-κB and interferon signaling pathways in the regulation of antiviral defense and apoptosis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1010:237-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hiscott, J., H. Kwon, and P. Genin. 2001. Hostile takeovers: viral appropriation of the NF-κB pathway. J. Clin. Investig. 107:143-151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horvath, C. M. 2000. STAT proteins and transcriptional responses to extracellular signals. Trends Biochem. Sci. 25:496-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Imazu, T., S. Shimizu, S. Tagami, M. Matsushima, Y. Nakamura, T. Miki, A. Okuyama, and Y. Tsujimoto. 1999. Bcl-2/E1B 19 kDa-interacting protein 3-like protein (Bnip3L) interacts with Bcl-2/Bcl-xL and induces apoptosis by altering mitochondrial membrane permeability. Oncogene 18:4523-4529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kamasani, U., and G. C. Prendergast. 2005. Genetic response to DNA damage: proapoptotic targets of RhoB include modules for p53 response and susceptibility to Alzheimer's disease. Cancer Biol. Ther. 4:282-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li, Z., J. Niu, T. Uwagawa, B. Peng, and P. J. Chiao. 2005. Function of polo-like kinase 3 in NF-κB-mediated proapoptotic response. J. Biol. Chem. 280:16843-16850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lipshutz, R. J., S. P. Fodor, T. R. Gingeras, and D. J. Lockhart. 1999. High density synthetic oligonucleotide arrays. Nat. Genet. 21:20-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu, A.-X., G. J. Cerniglia, E. J. Bernhard, and G. C. Prendergast. 2001. RhoB is required to mediate apoptosis in neoplastically transformed cells after DNA damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:6192-6197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu, A. X., N. Rane, J. P. Liu, and G. C. Prendergast. 2001. RhoB is dispensable for mouse development, but it modifies susceptibility to tumor formation as well as cell adhesion and growth factor signaling in transformed cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:6906-6912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu, G., A. E. Loraine, R. Shigeta, M. Cline, J. Cheng, V. Valmeekam, S. Sun, D. Kulp, and M. A. Siani-Rose. 2003. NetAffx: Affymetrix probe sets and annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:82-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lopez, C. D., Y. Ao, L. H. Rohde, T. D. Perez, D. J. O'Connor, X. Lu, J. M. Ford, and L. Naumovski. 2000. Proapoptotic p53-interacting protein 53BP2 is induced by UV irradiation but suppressed by p53. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:8018-8025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ma, S., J. Charron, and R. L. Erikson. 2003. Role of Plk2 (Snk) in mouse development and cell proliferation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:6936-6943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nibert, M. L., and L. A. Schiff. 2001. Reoviruses and their replication, p. 1679-1728. In D. M. Knipe and P. M. Howley (ed.), Fields virology, 4th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 38.Oberhaus, S. M., R. L. Smith, G. H. Clayton, T. S. Dermody, and K. L. Tyler. 1997. Reovirus infection and tissue injury in the mouse central nervous system are associated with apoptosis. J. Virol. 71:2100-2106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O'Donnell, S. M., M. W. Hansberger, J. L. Connolly, J. D. Chappell, M. J. Watson, J. M. Pierce, J. D. Wetzel, W. Han, E. S. Barton, J. C. Forrest, T. Valyi-Nagy, F. E. Yull, T. S. Blackwell, J. N. Rottman, B. Sherry, and T. S. Dermody. 2005. Organ-specific roles for transcription factor NF-κB in reovirus-induced apoptosis and disease. J. Clin. Investig. 115:2341-2350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pahl, H. L. 1999. Activators and target genes of Rel/NF-κB transcription factors. Oncogene 18:6853-6866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pine, R., A. Canova, and C. Schindler. 1994. Tyrosine phosphorylated p91 binds to a single element in the ISGF2/IRF-1 promoter to mediate induction by IFN alpha and IFN gamma, and is likely to autoregulate the p91 gene. EMBO J. 13:158-167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rodgers, S. E., J. L. Connolly, J. D. Chappell, and T. S. Dermody. 1998. Reovirus growth in cell culture does not require the full complement of viral proteins: identification of a σ1s-null mutant. J. Virol. 72:8597-8604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Samuels-Lev, Y., D. J. O'Connor, D. Bergamaschi, G. Trigiante, J.-K. Hsieh, S. Zhong, I. Campargue, L. Naumovski, T. Crook, and X. Lu. 2001. ASPP proteins specifically stimulate the apoptotic function of p53. Mol. Cell 8:781-794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sen, G. C. 2001. Viruses and interferons. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 55:255-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Silverman, N., and T. Maniatis. 2001. NF-κB signaling pathways in mammalian and insect innate immunity. Genes Dev. 15:2321-2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sironi, J. J., and T. Ouchi. 2004. STAT1-induced apoptosis is mediated by caspases 2, 3, and 7. J. Biol. Chem. 279:4066-4074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith, M. L., J. M. Ford, M. C. Hollander, R. A. Bortnick, S. A. Amundson, Y. R. Seo, C.-X. Deng, P. C. Hanawalt, and A. J. Fornace, Jr. 2000. p53-mediated DNA repair responses to UV radiation: studies of mouse cells lacking p53, p21, and/or gadd45 genes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:3705-3714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stark, G. R., I. M. Kerr, B. R. Williams, R. H. Silverman, and R. D. Schreiber. 1998. How cells respond to interferons. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67:227-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Strong, J. E., and P. W. Lee. 1996. The v-erbB oncogene confers enhanced cellular susceptibility to reovirus infection. J. Virol. 70:612-616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sturzenbecker, L. J., M. L. Nibert, D. B. Furlong, and B. N. Fields. 1987. Intracellular digestion of reovirus particles requires a low pH and is an essential step in the viral infectious cycle. J. Virol. 61:2351-2361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tamura, T., M. Ishihara, M. S. Lamphier, N. Tanaka, I. Oishi, S. Aizawa, T. Matsuyama, T. W. Mak, S. Taki, and T. Taniguchi. 1995. An IRF-1-dependent pathway of DNA damage-induced apoptosis in mitogen-activated T lymphocytes. Nature 376:596-599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tan, K. O., K. M. L. Tan, S.-L. Chan, K. S. Y. Yee, M. Bevort, K. C. Ang, and V. C. Yu. 2001. MAP-1, a novel proapoptotic protein containing a BH3-like motif that associates with Bax through its Bcl-2 homology domains. J. Biol. Chem. 276:2802-2807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tanaka, N., M. Ishihara, M. Kitagawa, H. Harada, T. Kimura, T. Matsuyama, M. S. Lamphier, S. Aizawa, T. W. Mak, and T. Taniguchi. 1994. Cellular commitment to oncogene-induced transformation or apoptosis is dependent on the transcription factor IRF-1. Cell 77:829-839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tanaka, N., M. Sato, M. S. Lamphier, H. Nozawa, E. Oda, S. Noguchi, R. D. Schreiber, Y. Tsujimoto, and T. Taniguchi. 1998. Type I interferons are essential mediators of apoptotic death in virally infected cells. Genes Cells 3:29-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Taterka, J., M. Sugcliffe, and D. H. Rubin. 1994. Selective reovirus infection of murine hepatocarcinoma cells during cell division. A model of viral liver infection. J. Clin. Investig. 94:353-360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tian, B., D. E. Nowak, M. Jamaluddin, S. Wang, and A. R. Brasier. 2005. Identification of direct genomic targets downstream of the nuclear factor-κB transcription factor mediating tumor necrosis factor signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 280:17435-17448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tian, B., Y. Zhang, B. A. Luxon, R. P. Garofalo, A. Casola, M. Sinha, and A. R. Brasier. 2002. Identification of NF-κB-dependent gene networks in respiratory syncytial virus-infected cells. J. Virol. 76:6800-6814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tong, T., J. Ji, S. Jin, X. Li, W. Fan, Y. Song, M. Wang, Z. Liu, M. Wu, and Q. Zhan. 2005. Gadd45a expression induces Bim dissociation from the cytoskeleton and translocation to mitochondria. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:4488-4500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tyler, K. L. 2001. Mammalian reoviruses, p. 1729-1745. In D. M. Knipe and P. M. Howley (ed.), Fields virology, 4th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 60.Tyler, K. L., M. K. Squier, S. E. Rodgers, S. E. Schneider, S. M. Oberhaus, T. A. Grdina, J. J. Cohen, and T. S. Dermody. 1995. Differences in the capacity of reovirus strains to induce apoptosis are determined by the viral attachment protein σ1. J. Virol. 69:6972-6979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Virgin, H. W., IV, R. Bassel-Duby, B. N. Fields, and K. L. Tyler. 1988. Antibody protects against lethal infection with the neurally spreading reovirus type 3 (Dearing). J. Virol. 62:4594-4604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Virgin, H. W., K. L. Tyler, and T. S. Dermody. 1997. Reovirus, p. 669-699. In N. Nathanson (ed.), Viral pathogenesis. Lippincott-Raven, New York, N.Y.

- 63.Webster, G. A., and N. D. Perkins. 1999. Transcriptional cross talk between NF-κB and p53. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:3485-3495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang, Y., B. A. Luxon, A. Casola, R. P. Garofalo, M. Jamaluddin, and A. R. Brasier. 2001. Expression of respiratory syncytial virus-induced chemokine gene networks in lower airway epithelial cells revealed by cDNA microarrays. J. Virol. 75:9044-9058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.