Abstract

Bacterial genomes are usually partitioned in several replicons, which are dynamic structures prone to mutation and genomic rearrangements, thus contributing to genome evolution. Nevertheless, much remains to be learned about the origins and dynamics of the formation of bacterial alternative genomic states and their possible biological consequences. To address these issues, we have studied the dynamics of the genome architecture in Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234 and analyzed its biological significance. NGR234 genome consists of three replicons: the symbiotic plasmid pNGR234a (536,165 bp), the megaplasmid pNGR234b (>2,000 kb), and the chromosome (>3,700 kb). Here we report that genome analyses of cell siblings showed the occurrence of large-scale DNA rearrangements consisting of cointegrations and excisions between the three replicons. As a result, four new genomic architectures have emerged. Three consisted of the cointegrates between two replicons: chromosome-pNGR234a, chromosome-pNGR234b, and pNGR234a-pNGR234b. The other consisted of a cointegrate of the three replicons (chromosome-pNGR234a-pNGR234b). Cointegration and excision of pNGR234a with either the chromosome or pNGR234b were studied and found to proceed via a Campbell-type mechanism, mediated by insertion sequence elements. We provide evidence showing that changes in the genome architecture did not alter the growth and symbiotic proficiency of Rhizobium derivatives.

Many bacteria harbor multiple replicons consisting of chromosomes and plasmids in either linear or circular forms (11). These replicons may interact resulting in either cointegrated or independent units. The classic paradigm is exemplified by F plasmids, conceptually referred to as episomes. In fact, F plasmids may exist as free circular genetic elements or integrated into the Escherichia coli chromosome (1). Another interesting example, due to its topology, concerns the megabase-sized, linear plasmids of Streptomyces that in some strains have been found as autonomously replicating entities while in others are present as cointegrates with the linear chromosome (9). The existence of plasmids in free or integrated form may have genetic and biological consequences, since they could be transferred alone or together with adjacent segments of the chromosome, allowing the transmission of new traits into a recipient cell (8). Plasmid-chromosome hybrids have been found in different bacteria. Usually the dynamics of genome architecture has been inferred from a comparison of different strains. To better understand the dynamics and biological consequences of differential genomic structures at the intrastrain level, we have obtained natural derivatives of Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234 with alternative genomic architectures and examined their growth and symbiotic properties.

Rhizobia establish nitrogen-fixing symbioses with leguminous plants. Strain NGR234 has the broadest host range known to date, being capable of nodulating more than 112 genera of legumes as well as the nonlegume Parasponia andersonii (18). Generally, the NGR234 genome is partitioned into three replicons: the chromosome, the symbiotic (Sym) plasmid or pNGR234a that carries most of the genes for nodulation and nitrogen fixation, and a megaplasmid or pNGR234b which contains exopolysaccharide genes (2). The complete sequence of pNGR234a showed the presence of a large amount of reiterated sequences, mainly insertion sequence elements (4). Some of them participate in intragenomic rearrangements such as DNA amplifications or deletions (3). Reiterated sequences are also present in the chromosome and in pNGR234b (16, 24), suggesting that the three replicons may participate in the plasticity of the NGR234 genome. This makes strain NGR234 a convenient model to analyze genome dynamics and its biological consequences.

In this study, we provide evidence that the genome of NGR234 undergoes large-scale DNA rearrangements consisting of replicon fusions and excisions, promoted mainly by homologous recombination between insertion sequence elements. Cell siblings from the wild-type Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234, containing alternative genomic architectures, were isolated and tested for growth and symbiotic properties.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial cultures.

Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234 and its derivatives were routinely propagated in PY medium (0.5% peptone, 0.3% yeast extract, and 10 mM CaCl2) containing 50 μg of rifampin/ml. In all experiments reported here, a culture was started by inoculating a portion of a single colony into liquid medium and incubating overnight at 28°C.

Isolation of Rhizobium derivatives.

Leading up to the isolation of Rhizobium derivatives by the culture-based method, a 5-ml overnight culture was diluted and plated on solid agar medium. Individual colonies were isolated and screened for rearrangements. The frequency of rearrangements was reported as the proportion of rearranged cells in a total population.

For the PCR-based strategy and artificial selection of rearranged subpopulations, the reported procedure (3) was modified as follows: a culture of a strain was diluted, and a total of 100 aliquots containing 100 cells/2 μl were spotted on an agar plate. Individual colonies derived from 100 cells were inoculated into liquid medium, and genomic DNA was isolated. PCR assays (see below) were performed with each DNA sample by using primers that detect the recombinant product of a predicted genome architecture. The colony corresponding to the highest amount of PCR product was selected. Samples of the selected colony were handled as described above, except that each spotted aliquot contained 50 cells. The procedure was continued with spots containing 10 cells, and finally individual colonies were isolated and screened. At this step, a colony showing an optimal PCR signal was usually “pure” for a specific rearrangement. A colony of a culture was considered pure for a specific rearrangement when most of the individual cells plated from the culture gave rise to colonies showing an optimal PCR signal for the rearrangement. To quantify cells containing a particular genome structure in different subpopulations, a strain pure for a particular rearrangement was used as a standard in a PCR amplification procedure. This is based on the amount of PCR products yielded as a function of the number of amplification cycles in the reaction. Similar amounts of genomic DNAs of the strains were used as templates in PCR amplification with primers that detected the specific PCR product. If a similar amount of PCR product was obtained, differences in the number of reaction cycles were used to estimate the proportion of cells bearing the genomic structure (3).

DNA manipulations and PFGE.

Isolation of genomic and plasmidic DNA, DNA restriction and cloning, DNA labeling, and filter blot hybridization were performed as described earlier (12). Plasmid profiles were obtained as described elsewhere (10). For pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), intact genomic DNAs in agarose plugs were prepared according to published protocols (20) with some modifications. Briefly, Rhizobium strains were grown to an optical density at 600 nm of 1.0. A total of 75 ml of cell culture was centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C. The pellet was washed once and resuspended in Tris-EDTA buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 7.5, and 0.1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) to a density of 8 × 109 cells per ml. An equal volume (1 ml) of 1.6% low-melt, preparative-grade agarose (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) in water was added to the cell suspension, and the mixture was distributed into the mould (200 μl/well) and cooled at 4°C for 15 min. Agarose plugs were treated with 1.2 mg of lysozyme (Sigma)/ml overnight at 37°C and with 2 mg of proteinase K (Sigma)/ml at 50°C for 48 h. After incubation in 0.4 mg of phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride/ml at 50°C for 1 h, the agarose plugs were washed once and stored in 0.5 M EDTA, pH 8.0, at 4°C. Approximately 1 μg of agarose-embedded DNAs was loaded into wells. PFGE was performed using a CHEF Mapper apparatus (Bio-Rad) with 0.8% chromosomal-grade agarose (Bio-Rad) in 1× TAE (40 mM Tris-acetate-1 mM EDTA). Conditions were as follows: a constant pulse of 35 min, a 106° field angle, a temperature of 13°C, and a run of 80 h at 2 V/cm.

PCR assays.

All of the primers were synthesized by Bio-Synthesis (Lewinsville, Tex.). The oligonucleotides designed to prime the NGRRS-1 repeat in each replicon were the following: chromosomal forward primer (FP) 5′-GACATCTCCTCGACCAGCTCCACAGCCTTC-3′ 82 bp upstream of NGRRS-1 in cosmid pXB826; chromosomal reverse primer (RP) 5′-AGCAACGCCGTCGTATTGAGGAGGCAGAAC-3′ 7 bp downstream of NGRRS-1 in pXB826; pNGR234b FP 5′-GGTAGCGAACTGTCCGAGGAGGAGTTGAAC-3′ 265 bp upstream of NGRRS-1 in cosmid pXB9; pNGR234b RP 5′-GTTGATCATTCGACGGGAAGACGACGAGAC-3′ 452 bp downstream of NGRRS-1 in pXB9 (K. Reichwald, X. Perret, and W. J. Broughton, unpublished data); pNGR234a FP 5′-ACCTCCTGTTTGCAGCATGGATTCAGATTC-3′ 78 bp upstream of NGRRS-1; and pNGR234a RP 5′-CGTTGGACAAAAGCTGTAACCCGCTAAATC-3′ 172 bp downstream of NGRRS-1 in the reported sequence (4).

PCR assays were carried out in a 25-μl reaction containing the template genomic DNA (150 ng) in 1× polymerase reaction XL buffer II (Perkin-Elmer, Branchburg, N.J.), 1.1 mM magnesium acetate, 200 μM concentrations of deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 5 pmol of each primer, and 1 U of rTth polymerase (Perkin-Elmer). PCR amplifications were performed in a 2,400 Thermocycler (Perkin-Elmer) with the following thermal conditions: an initial denaturation at 94°C for 1 min; 37 cycles (unless otherwise stated) of denaturation (15 s at 94°C) and annealing (5 min at 68°C); and a final extension at 72°C for 7 min. PCR products were monitored by gel electrophoresis in 1% agarose and by staining with ethidium bromide.

Bacterial growth kinetics and plant assays.

For growth kinetics, bacterial strains were cultivated in 250-ml flasks containing 50 ml of minimal RMM3 (17) or PY media inoculated to an initial optical density at 600 nm of 0.02. Nodulation tests were performed in Magenta jars (19) containing four plants each in four replicates. Each plant was inoculated with 106 bacterial cells. Experiments with Vigna unguiculata and Leucaena leucocephala were repeated twice. The total nodule number was determined for each pot, and total plant dry weight was determined after drying at 75°C for 72 h.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Rationale for isolation of Rhizobium strains with alternative genome architectures.

To detect cell siblings containing different genomic architectures, two strategies were followed. In a culture-based strategy, a culture of a Rhizobium strain is plated on a solid rich medium. Individual colonies are isolated, and their plasmid profile and hybridization with specific replicon probes are compared to those of the parental strain. Changes in plasmid pattern indicated the possible emergence of new genomic architectures. We focused on cointegration between replicons that might arise by large-scale DNA rearrangements. This is indicated by the disappearance of plasmid bands and the appearance of replicons with a higher molecular weight. Derivative clones containing potential new genomic architectures are further analyzed by PFGE.

A second strategy consists of a PCR-based method coupled with artificial selection of rearranged derivative strains, which has been referred to as natural genomic design (3). Based on complete or partial sequences of Rhizobium replicons, repeated sequences significant for homologous recombination and that are shared by different replicons are selected. Recombination between such sequences may lead to replicon cointegration. PCR primers that match regions proximal, but external, to the homologous repeats are synthesized. The appropriate combination of primers may allow the detection of a PCR product corresponding to the recombinant band generated by a replicon fusion. Actually, the FP of a repeated sequence in replicon a with the RP of the homologous repeated sequence in replicon b or vice versa would detect a recombinant product resulting from a cointegration between both replicons. After the detection of the recombinant product, cell cultures pure for a particular cointegration are isolated by an artificial selection procedure (3). This is based on the gradual enrichment of the specific rearrangement in subpopulations of the original culture. The degree of enrichment is determined by quantifying the specific recombinant PCR product (Materials and Methods).

Emergence of Rhizobium sp. strains with different genome architectures.

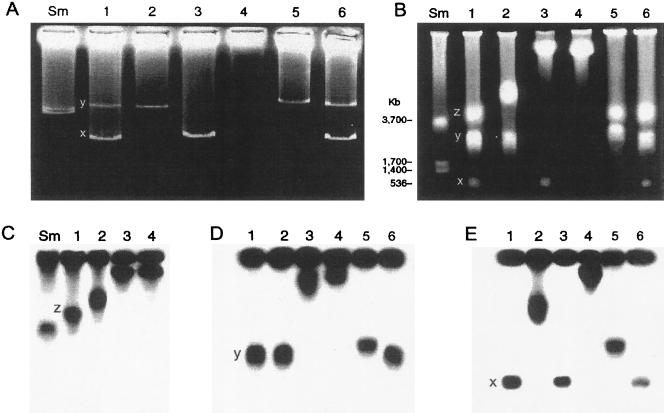

By use of the culture-based strategy, a total of 3,000 individual colonies were isolated from the wild-type Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234 and its derivatives. Isolated colonies were first screened by plasmid patterns, and then potential candidates containing new genomic architectures were further analyzed by PFGE. Representative data are presented in Fig. 1. Sinorhizobium meliloti strain 1021 has a well-known genome structure (5, 21) that was used as a control and showed the three expected replicons: the chromosome (3,654 kb) and two megaplasmids (pSyma, 1,354 kb; and pSymb, 1,683 kb). The wild-type Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234 harbors three replicons: the chromosome, which is larger than that of S. meliloti; the symbiotic plasmid (536 kb) or pNGR234a; and a megaplasmid or pNGR234b, which is larger than the pSymb of S. meliloti. The three replicons hybridized with their respective specific DNA probes (Fig. 1C to E). Interestingly, three types of derivative strains containing new genome architectures emerged at about 10−3 frequency. Strains with pNGR234a integrated into the chromosome (CFNX401 type) (Fig. 1, lane 2) and those harboring a pNGR234b-chromosome hybrid (CFNX407 type) (Fig. 1, lane 3) came from the wild-type NGR234, whereas strains in which both plasmids and the chromosome form a unique, large replicon (CFNX408 type) (Fig. 1, lane 4) were derived from CFNX401 or CFNX407.

FIG. 1.

Characterization of genomic architecture of Rhizobium sp. strains. (A) Plasmid profiles. (B) PFGE of undigested genomic DNA stained by ethidium bromide. (C to E) Autoradiographs of blotted PFGE hybridized against replicon-specific probes: 16S RNA gene probe for the chromosome (C), exopolysaccharide gene probe for pNGR234b (D), and nitrogenase gene probe for pNGR234a (E). Lanes: Sm, S. meliloti strain 1021; 1 and 6, wild-type strain NGR234; 2, CFNX401; 3, CFNX407; 4, CFNX408; and 5, CFNX416. The position of each replicon is indicated in the wild-type strain: x, pNGR234a; y, pNGR234b; and z, chromosome.

Prediction, identification, and isolation of derivatives containing specific cointegrations.

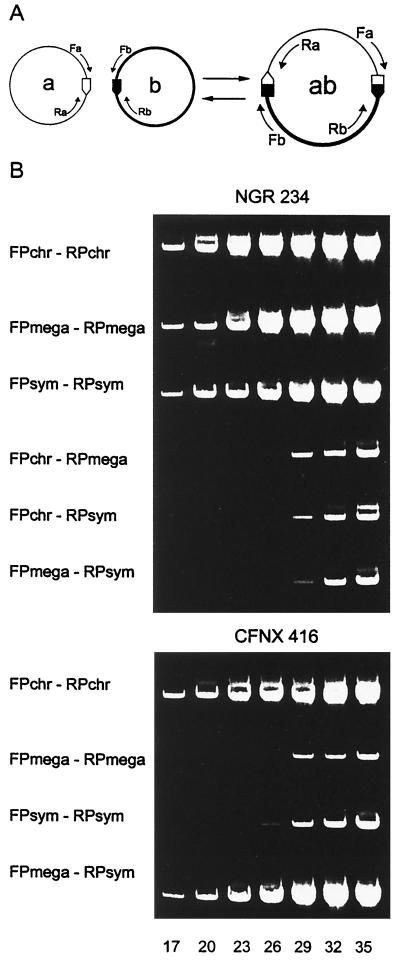

Based on the analysis of the complete pNGR234a sequence and partial sequences of pNGR234b and the chromosome, some reiterated elements shared by the three replicons were identified. One of them consists of a complex repeated element, NGRRS-1 of 6 kb (16). Initially, the presence of one copy of NGRRS-1 in pNGR234a and three copies in the chromosome was reported (16). However, after the identification of the pNGR234b replicon (2), it is now known that the latter contains two NGRRS-1 copies, whereas the chromosome bears one. We have predicted cointegrations to occur between either two of the three replicons by homologous recombination involving NGRRS-1 repeats. To identify the presence of cells containing such cointegrations in the wild-type NGR234 strain, we applied the PCR-based approach (see above and diagram of Fig. 2A). FPs and RPs were designed in the regions proximal to one NGRRS-1 repeat in each of the three replicons. As expected, PCRs performed with the FPs and RPs of the same replicon produced optimal PCR signals in the wild-type NGR234 strain (Fig. 2B). The combination of primers from two different replicons, either chromosome-pNGR234a or chromosome-pNGR234b or pNGR234a-pNGR234b, yielded the PCR product expected for each particular cointegration. However, as inferred from the PCR cycles, the PCR products were obtained at a much lower concentration (Fig. 2). This indicates that, in the wild-type population, only a fraction of cells contained a particular rearrangement, estimated in frequencies of 10−3 to 10−4.

FIG. 2.

Identification and quantification of cointegration and excision events in wild-type NGR234 and in the derivative CFNX416. (A) Schematic representation of cointegration and excision between two replicons (a and b) sharing homologous repeats (⌂,  ). The use of FP and RP from the same replicon reveals the wild-type structure. A combination of FP of replicon a and RP of replicon b or vice versa allows the detection of the recombinant bands (

). The use of FP and RP from the same replicon reveals the wild-type structure. A combination of FP of replicon a and RP of replicon b or vice versa allows the detection of the recombinant bands ( ,

,  ) generated in the cointegration; reversion is revealed by detecting the original structure with primers belonging to each of the replicons. (B) PCR products monitored by agarose gel electrophoresis and staining with ethidium bromide. PCR assays were performed at a different cycle of reactions (indicated at the bottom of the lanes). Different primers were used to detect the original or recombinant PCR products. The quantification was carried out by comparing the number of PCR cycles necessary to produce a certain amount of PCR product as indicated in Materials and Methods. Chr, chromosome; mega, megaplasmid pNGR234b; and sym, symbiotic plasmid pNGR234a.

) generated in the cointegration; reversion is revealed by detecting the original structure with primers belonging to each of the replicons. (B) PCR products monitored by agarose gel electrophoresis and staining with ethidium bromide. PCR assays were performed at a different cycle of reactions (indicated at the bottom of the lanes). Different primers were used to detect the original or recombinant PCR products. The quantification was carried out by comparing the number of PCR cycles necessary to produce a certain amount of PCR product as indicated in Materials and Methods. Chr, chromosome; mega, megaplasmid pNGR234b; and sym, symbiotic plasmid pNGR234a.

In the culture-based strategy, strains containing a pNGR234a-pNGR234b cointegration were not detected. The PCR-based procedure was used to obtain a subpopulation pure for the pNGR234a-pNGR234b cointegration. Actually, rearrangements promoted by homologous recombination between repeated elements are usually reversible. Thus, a subpopulation will never be pure since some cells should contain the revertant architecture (reference 3 and see below). As illustrated in Fig. 2B, the subpopulation pure for the pNGR234a-pNGR234b cointegration showed an optimal PCR signal when using one primer derived from pNGR234a and the other from pNGR234b (exemplified by the CFNX416 strain). It is important that when both primers were derived from one replicon, either pNGR234a or pNGR234b, a low-intensity PCR product resulted, indicating that, in the purified subpopulation, some cells have reverted to the original architecture (CFNX416) (Fig. 2B). In contrast, when the two primers derived from the chromosome were used, the PCR signal was optimal. The quantification experiments based on PCR amplification at different reaction cycles (Materials and Methods) indicated that the wild-type population contained pNGR234a-pNGR234b cointegrate at about 1 per 104 cells and that, in derivative CFNX416, revertant cells were present at a similar proportion (Fig. 2B).

Further characterization of the derivative strains containing pNGR234a-pNGR234b cointegration showed the expected plasmid and PFGE patterns with a larger new replicon (CFNX416 type) (Fig. 1A and B, lane 5) that hybridized with each of the respective replicon-specific probes (Fig. 1D and E, lane 5).

In a previous study (3), the PCR-based strategy coupled with artificial selection of rearranged subpopulations, referred to as genomic design, has been used to predict and characterize rearrangements such as amplifications and deletions of discrete DNA regions in pSym of Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234. Our results demonstrate that the genomic design approach can be experimentally extended to obtain large-scale architectural changes.

Integration sites of pSym into other replicons.

Based on the reported sequence of pNGR234a (4), sets of primers were designed to produce 96 overlapping PCR products of about 6 kb each, covering the complete pNGR234a replicon. Amplifications yielded all the corresponding PCR products in wild-type NGR234 and derivative strains, except for the regions involved in cointegration events (data not shown). From these data, we conclude that the entire pNGR234a replicon is integrated into the chromosome by homologous recombination between DNA regions containing insertion sequences. In strains CFNX401 and CFNX408, pSym was cointegrated through NGRIS3a and NGRIS3c, respectively. NGRIS3a and NGRIS3c repeats are identical in sequence but lie 168,007 bp from each other on the pNGR234a replicon. These sites of integration were ascertained by detecting the corresponding recombinant bands by Southern hybridization of PstI-digested genomic DNA, using an internal fragment of NGRIS3 as a probe (data not shown).

To ascertain if NGRRS-1 represents the site of recombination between pNGR234a and pNGR234b in strain CFNX416, the DNA sequences of the borders of the recombinant PCR products were determined. They were shown to be identical to that expected for the recombinant products (data not shown), compared with sequences reported for pNGR234a (4) and the cosmid pXB9 region of pNGR234b.

Stability of derivative strains with different genome architectures.

To test the stability of genome structure of derivatives harboring cointegrations, strains CFNX401, CFNX407, CFNX408, and CFNX416 were grown in liquid medium and subcultured every day in fresh medium. After different periods of growth, the cultures were screened en masse to analyze their genomic architecture. After 30 days (≈200 generations), derivative strains with a particular genome architecture showed the identical genome structure (data not shown). However, if a culture of a derivative strain was plated and individual colonies were isolated, in some cases siblings showed the emergence of new genome architectures, including revertants with plasmids of a size similar to that of the parental strain, confirming the participation of the entire plasmid replicons with regard to the cointegration and excision events (data not shown). As shown above, the PCR-based strategy to detect rearrangements also showed the occurrence of excision events in strain CFNX416 (Fig. 2B). In one case the excised plasmid presented a different size of approximately 400 kb, suggesting the existence of other points of excision. The recombination site was identified by PCR and involved NGRIS5b and NGRIS5c of pNGR234a (data not shown).

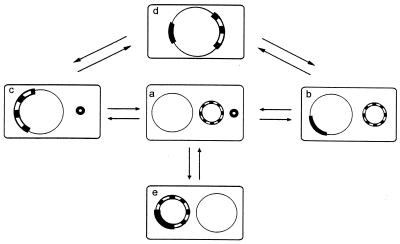

The reversible integration between replicons of Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234 confers a dynamic status to its genome. To illustrate that dynamic behavior, a synoptic view of the different genome architectures generated by cointegration and excision events is presented in Fig. 3. In the context of its dynamic behavior, NGR234 plasmids might be considered episomes by analogy with the F plasmids of E. coli (1). When integrated into the chromosome, the symbiotic plasmid could be considered a chromosomal symbiotic “island/region,” such as those described in Mesorhizobium loti (22) and Bradyrhizobium japonicum (6). Alternative genomic states raise numerous issues about the mechanisms of replication and maintenance of cointegrated replicons. For instance, the two plasmids pNGR234a and pNGR234b coexist in NGR234 cells, suggesting that they belong to different incompatibility groups. Thus, their respective origin of replication may be functional. Many plasmids contain multiple replication origins, and the selection of a particular origin of replication in such plasmids is determined by a complex mechanism (7). Characterization of the replication machinery in a cointegrate pNGR234a-pNGR234b should shed new light in the mechanism involved.

FIG. 3.

Synoptic view of the dynamics of genome architecture in Rhizobium. Interactions between replicons lead to cointegrations and excisions events (as indicated by arrows). This generates siblings with different genome structures. (a) Wild-type NGR234 with three replicons: chromosome (thin black segment); pNGR234b (white-and-black segment); and pNGR234a (thick black segment). (b) Derivative containing chromosome-pNGR234a cointegrate (CFNX401 type). (c) Derivative harboring chromosome-pNGR234b cointegrate (CFNX407 type). (d) Derivative bearing the cointegration of the three replicons: chromosome-pNGR234b-pNGR234a (CFNX408 type). (e) Derivative with a plasmid cointegration, pNGR234a-pNGR234b (CFNX416 type).

Growth and symbiotic phenotypes.

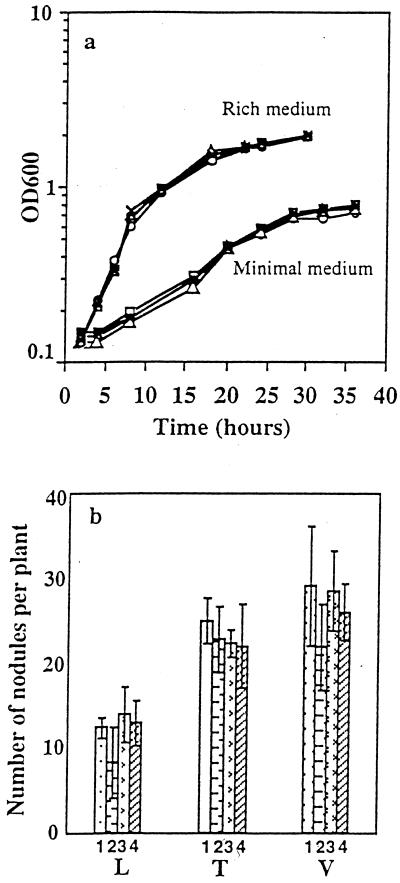

Differences in genomic structure could result in different phenotypic features. For example, differential partition of genetic information in alternative genomic structures may affect gene order and consequently transcriptional patterns and gene dosage. To investigate if changes in the genome architecture promote phenotypic drifts, we analyzed bacterial growth and the symbiotic properties by inoculating the legumes L. leucocephala, Tephrosia vogelii, and V. unguiculata with the wild-type strain and derivatives containing different genomic architectures. Both wild-type NGR234 and derivatives showed similar growth kinetics in either minimal or rich media (Fig. 4A) and did not differ in their capacity to form nodules on the host legumes (Fig. 4B). All Rhizobium sp. strains tested produced nitrogen-fixing nodules, and no significant differences were observed in the total plant dry weight (data not shown). The identities of the inoculated strains were confirmed by analyzing the plasmid and PFGE patterns of cells from liquid cultures and bacterial nodule isolates.

FIG. 4.

Phenotypic characteristics of Rhizobium sp. strains. (a) Growth kinetics. (b) Nodulation proficiency. Symbols in panel a: squares, wild-type NGR234; white circles, derivative of CFNX401; triangles, derivative of CFNX407; crosses, CFNX408; and black circles, CFNX416. Lanes in panel b: 1, wild-type NGR234; 2, CFNX401 derivative; 3, CFNX407 derivative; and 4, CFNX408. L, L. leucocephala; T, T. vogelii; and V, V. unguiculata. OD600, optical density at 600 nm.

Our results show that large-scale architectural genome changes are not accompanied by differences in important characteristics, such as bacterial growth or symbiotic proficiency with host plants, at least under laboratory and greenhouse conditions. Because these functions involve complex biological interactions, it cannot be ruled out that large-scale genomic reshufflings observed in this study may modify particular phenotypic traits, such as adaptation to particular conditions or selective pressure. Differences in genomic architecture could confer a distinct potentiality of adaptation to subpopulations derived from the same strain. Moreover, the differential partition of the genome is thought to play an important role in modulating horizontal gene transfer, which occurs in many bacteria, including rhizobia, thus contributing to genome evolution (22, 23).

By combining the two methods described in this study, we were able to obtain the four possible genome architectures, in regard to replicon fusions, in Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234. It is important that subpopulations enriched in a particular genome architecture were isolated in a very short experimental time, without introducing exogenous genetic elements and without exposure of the cells to any selective pressure. In concordance with recent studies on experimental evolution of bacteria (13–15), the work described here contributes to the belief that bacteria are capable of rapid genomic evolution that can be observed in action.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Rodríguez, A. Moreno, V. Quinto, and Rosa M. Ocampo for technical assistance as well as L. Barran, D. Romero, and M. Dunn for helpful comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants L0013N and 0028 from CONACyT-Mexico and IN214498 from DGAPA-UNAM-Mexico.

Footnotes

P.M. dedicates this paper to all colleagues of CIFN.

REFERENCES

- 1.Campbell, A. M. 1969. Episomes. Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 2.Flores, M., P. Mavingui, L. Girard, X. Perret, W. J. Broughton, E. Martínez-Romero, G. Dávila, and R. Palacios. 1998. Three replicons of Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234 harbor symbiotic gene sequences. J. Bacteriol. 180:6052–6053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flores, M., P. Mavingui, X. Perret, W. J. Broughton, D. Romero, G. Hernández, G. Dávila, and R. Palacios. 2000. Prediction, identification, and artificial selection of DNA rearrangements in Rhizobium: toward a natural genomic design. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:9138–9143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freiberg, C., R. Fellay, A. Bairoch, W. J. Broughton, A. Rosenthal, and X. Perret. 1997. Molecular basis of symbiosis between Rhizobium and legumes. Nature 387:394–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galibert, F., T. M. Finan, S. R. Long, A. Puhler, P. Abola, F. Ampe, F. Barloy-Hubler, M. J. Barnett, A. Becker, P. Boistard, G. Bothe, M. Boutry, L. Bowser, J. Buhrmester, E. Cadieu, D. Capela, P. Chain, A. Cowie, R. W. Davis, S. Dreano, N. A. Federspiel, R. F. Fisher, S. Gloux, T. Godrie, A. Goffeau, B. Golding, J. Gouzy, M. Gurjal, I. Hernandez-Lucas, A. Hong, L. Huizar, R. W. Hyman, T. Jones, D. Kahn, M. L. Kahn, S. Kalman, D. D. H. Keating, E. Kiss, C. Komp, V. Lelaure, D. Masuy, C. Palm, M. C. Peck, T. M. Pohl, D. Portetelle, B. Purnelle, U. Ramsperger, R. Surzycki, P. Thebault, M. Vandenbol, F. J. Vorholter, S. Weidner, D. H. Wells, K. Wong, K. C. Yeh, and J. Batut. 2001. The composite genome of the legume symbiont Sinorhizobium meliloti. Science 293:668–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Göttfert, M., S. Röthlisberger, C. Kündig, C. Beck, R. Marty, and H. Hennecke. 2001. Potential symbiosis-specific genes uncovered by sequencing a 410-kilobase DNA region of the Bradyrhizobium japonicum chromosome. J. Bacteriol. 183:1405–1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hiraga, S. 2000. Dynamic localization of bacterial and plasmid chromosomes. Annu. Rev. Genet. 34:21–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holloway, B. W. 1993. Genetics for all bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 47:659–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hopwood, D. A., and T. Kieser. 1990. The Streptomyces genome, p.147–161. In K. Drlica and M. Riley (ed.), The bacterial chromosome. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 10.Hynes, M. F., and N. F. McGregor. 1990. Two plasmids other than the nodulation plasmid are necessary for the formation of nitrogen-fixing nodules in Rhizobium leguminosarum. Mol. Microbiol. 4:567–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kraviecs, S., and M. Riley. 1990. Organization of the bacterial chromosome. Microbiol. Rev. 54:502–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mavingui, P., Flores, M., Romero, D., E. Martínez-Romero, and R. Palacios. 1997. Generation of Rhizobium strains with improved symbiotic properties by random DNA amplification (RDA). Nat. Biotechnol. 15:564–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naas, T., M. Blot, W. M. Fitch, and M. Arber. 1995. Dynamics of IS-related genetic rearrangements in resting Escherichia coli K-12. Mol. Biol. Evol. 12:198–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakatsu, C. H., R. Korona, R. Lenski, F. J. De Bruijn, T. L. Marsh, and L. J. Forney. 1998. Parallel and divergent genotypic evolution in experimental populations of Ralstonia sp. J. Bacteriol. 180:4325–4331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Papadopoulos, D., D. Schneider, J. Meier-Eiss, W. Arber, R. E. Lenski, and M. Blot. 1999. Genomic evolution during a 10,000-generation experiment with bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:3807–3812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perret, X., V. Viprey, C. Freiberg, and W. J. Broughton. 1997. Structure and evolution of NGRRS-1, a complex, repeated element in the genome of Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234. J. Bacteriol. 179:7488–7496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Price, N. P. J., B. Relic̀, F. Talmont, A. Lewin, D. Promé, S. G. Pueppke, F. Maillet, J. Dénarié, J.-C. Promé, and W. J. Broughton. 1992. Broad-host-range Rhizobium species strain NGR234 secretes a family of carbamoylated and fucosylated, nodulation signals that are O-acetylated or sulphated. Mol. Microbiol. 6:3575–3584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pueppke, S. G., and W. J. Broughton. 1999. Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234 and R. fredii USDA257 share exceptionally broad, nested host ranges. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 12:293–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Relic̀, B., F. Talmont, J. Kopcinska, W. Golinowski, J.-C. Promé, and W. J. Broughton. 1993. Biological activity of Rhizobium sp. NGR234 Nod-factors on Macroptilium atropurpureum. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 6:764–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwartz, D. C., and C. R. Cantor. 1984. Separation of yeast chromosome-sized DNAs by pulsed field gradient gel electrophoresis. Cell 37:67–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sobral, B. W., R. J. Honeycutt, A. G. Atherly, and M. McClelland. 1991. Electrophoretic separation of the three Rhizobium meliloti replicons. J. Bacteriol. 173:5173–5180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sullivan, J. T., and C. W. Ronson. 1998. Evolution of rhizobia by acquisition of a 500-kb symbiosis island that integrates into a phe-tRNA gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:5145–5149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Syvanen, M. 1994. Horizontal gene flow: evidence and possible consequences. Annu. Rev. Genet. 28:237–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Viprey, V., A. Rosenthal, W. J. Broughton, and X. Perret. 2000. Genetic snapshots of the Rhizobium species NGR234 genome. Genome Biol. 1:14.1–14.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]