Abstract

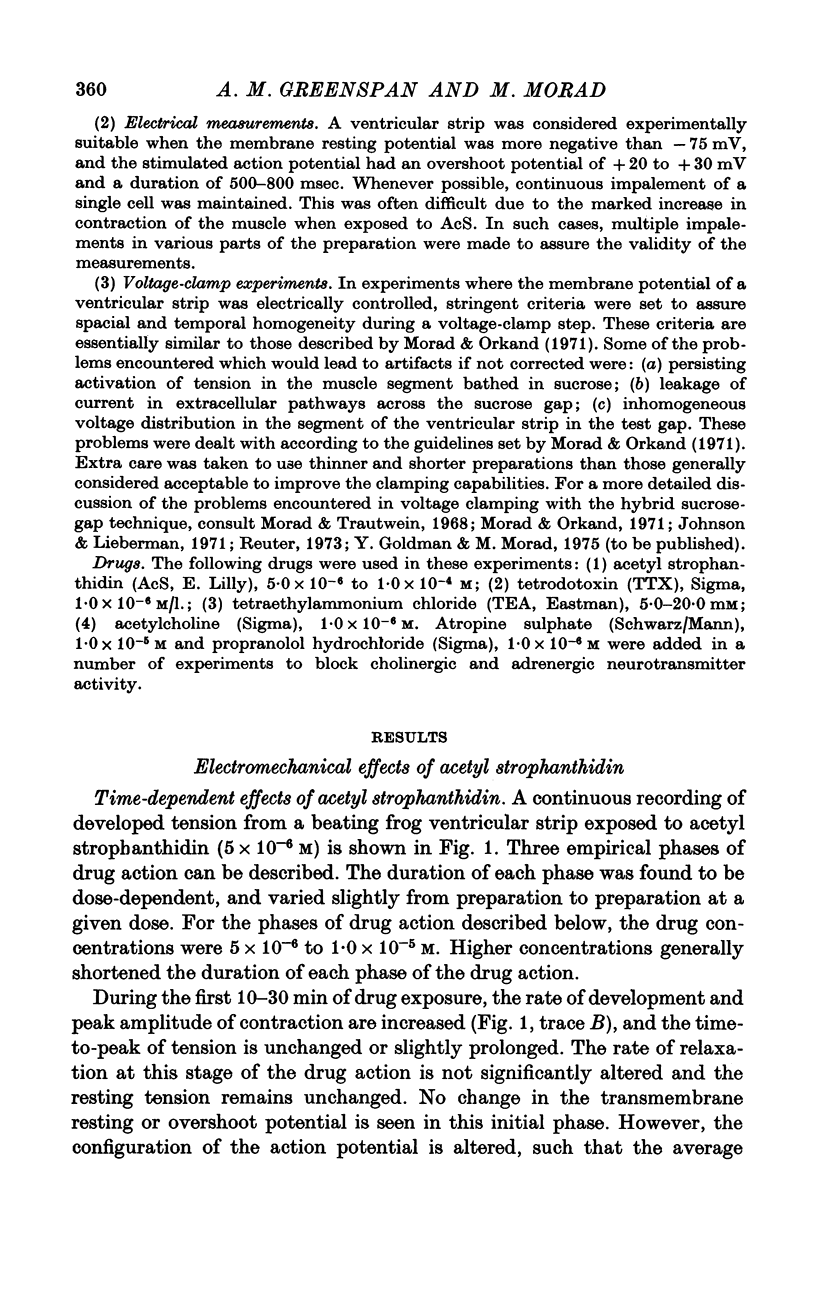

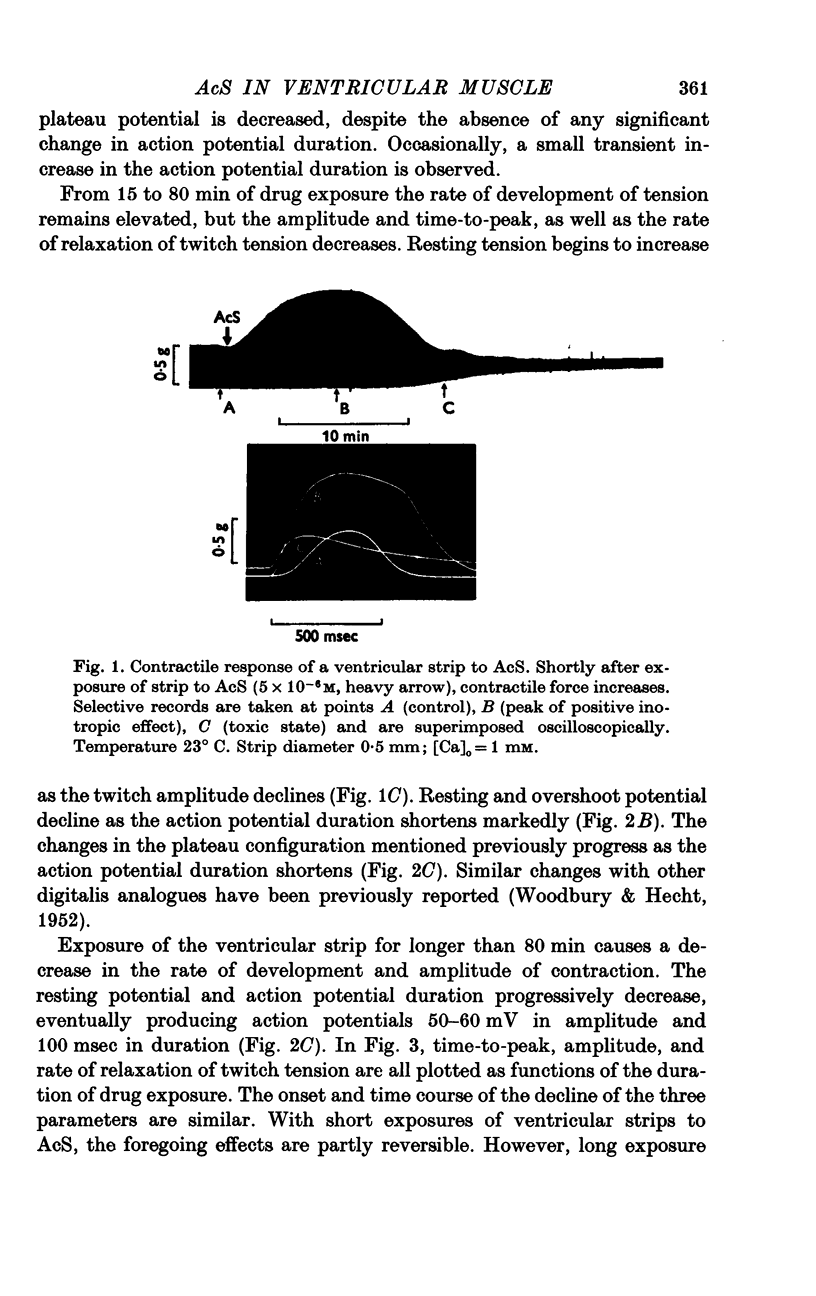

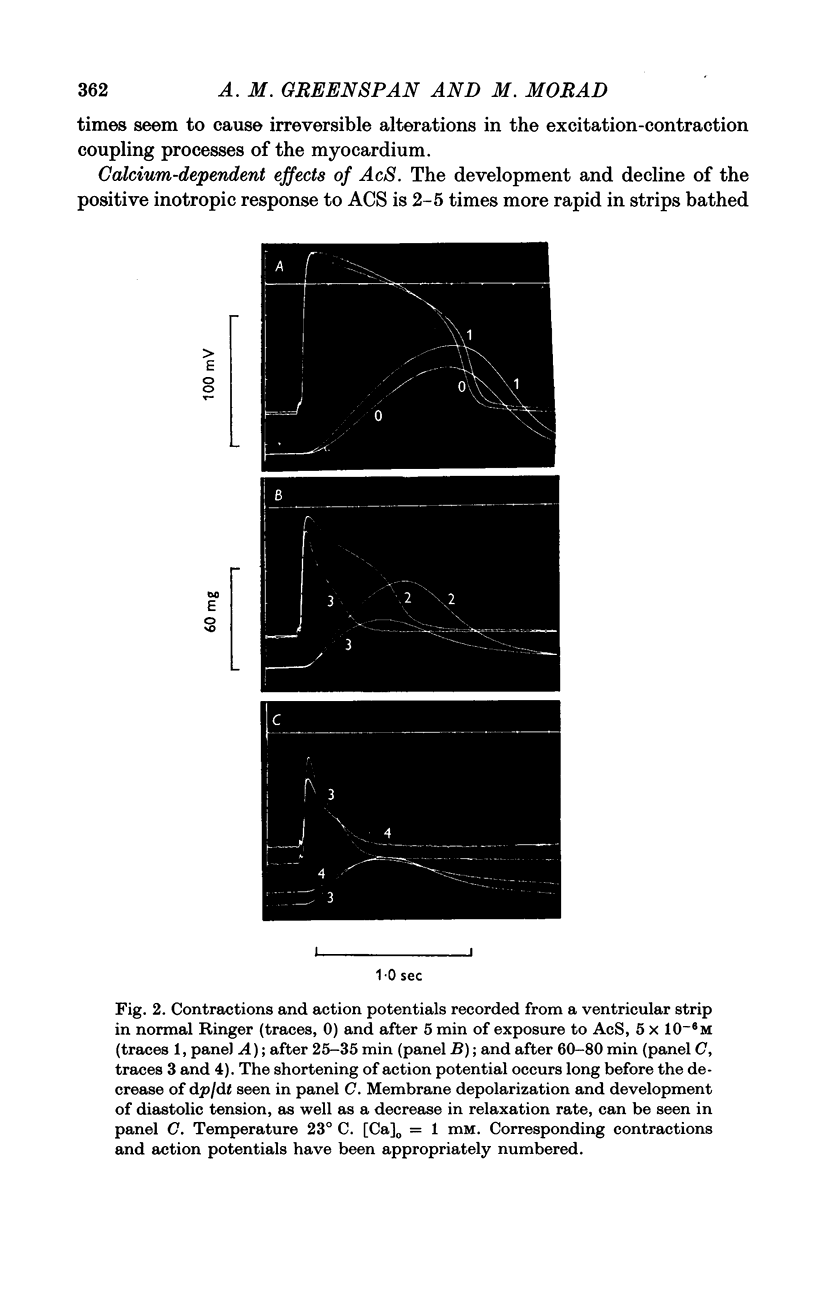

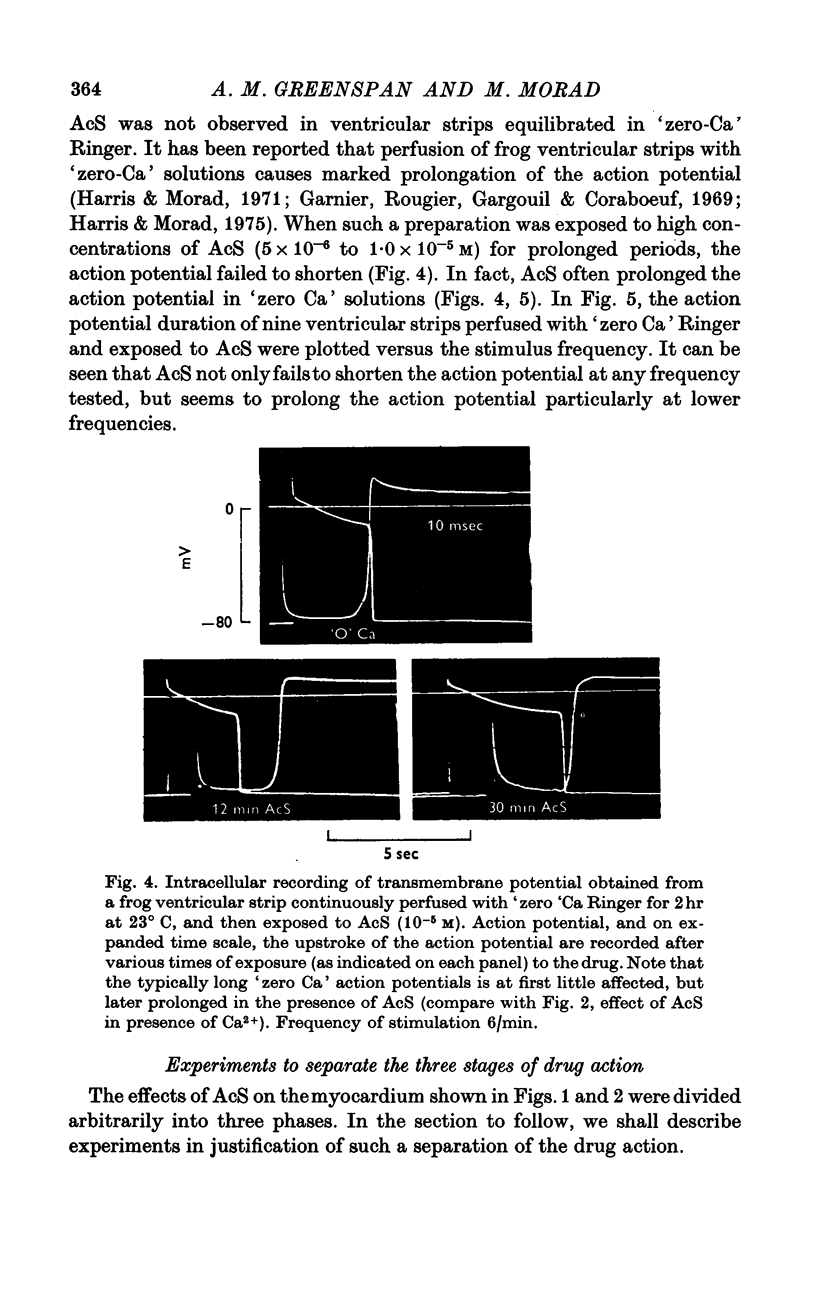

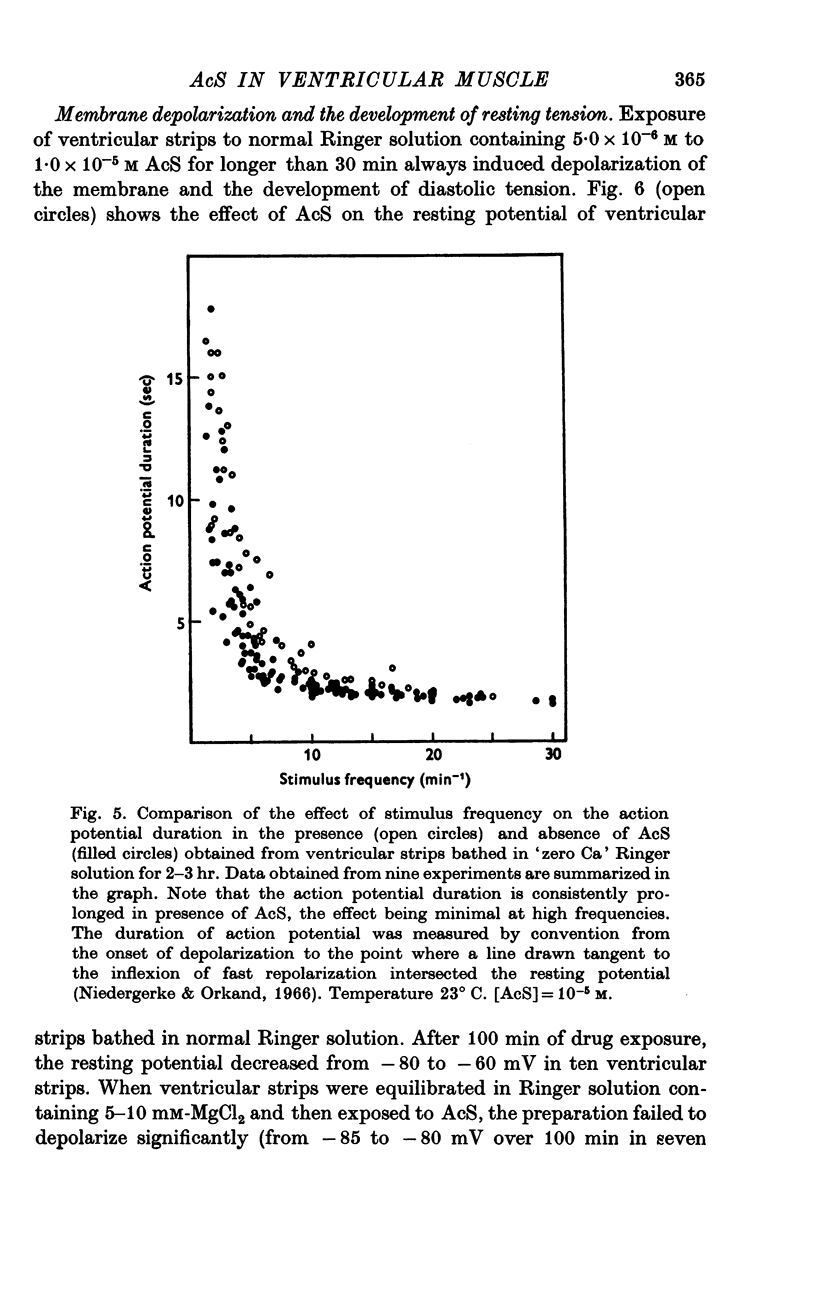

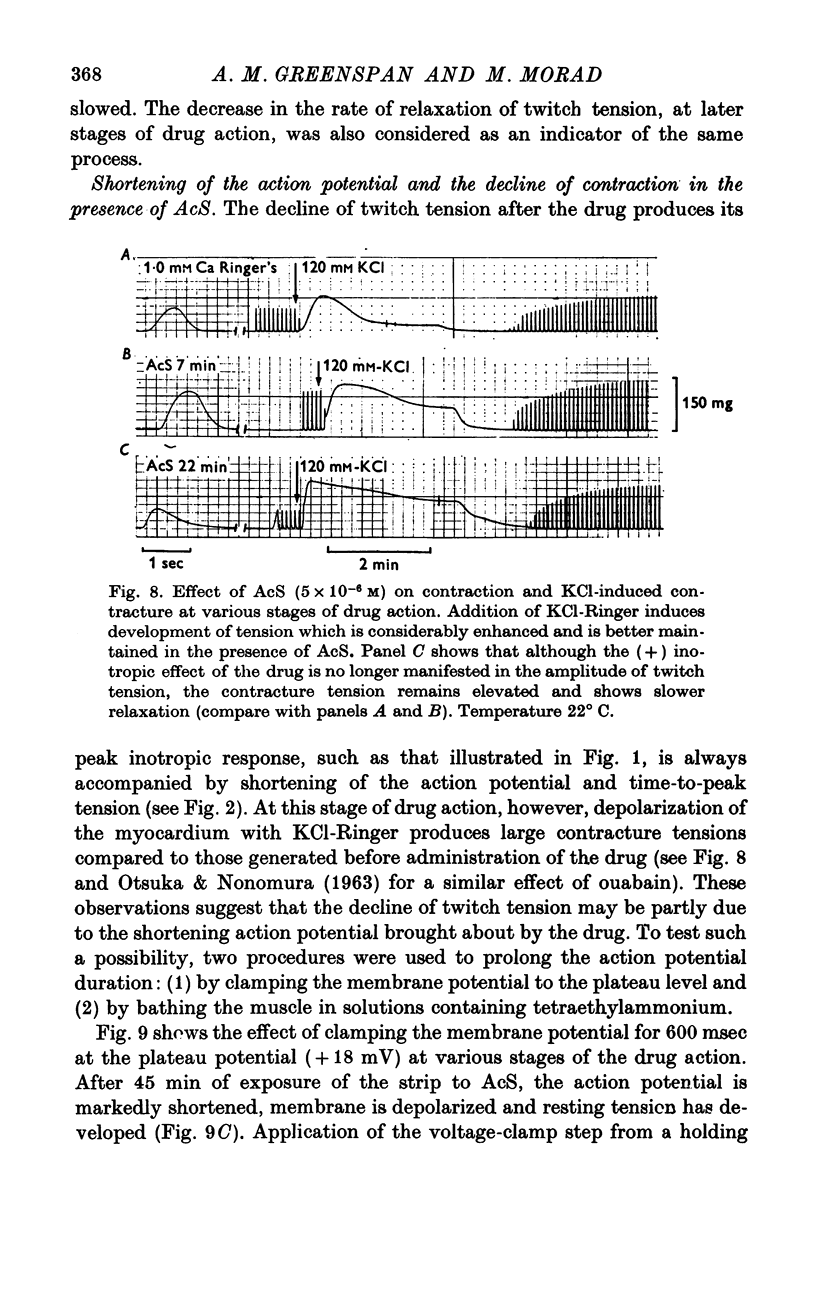

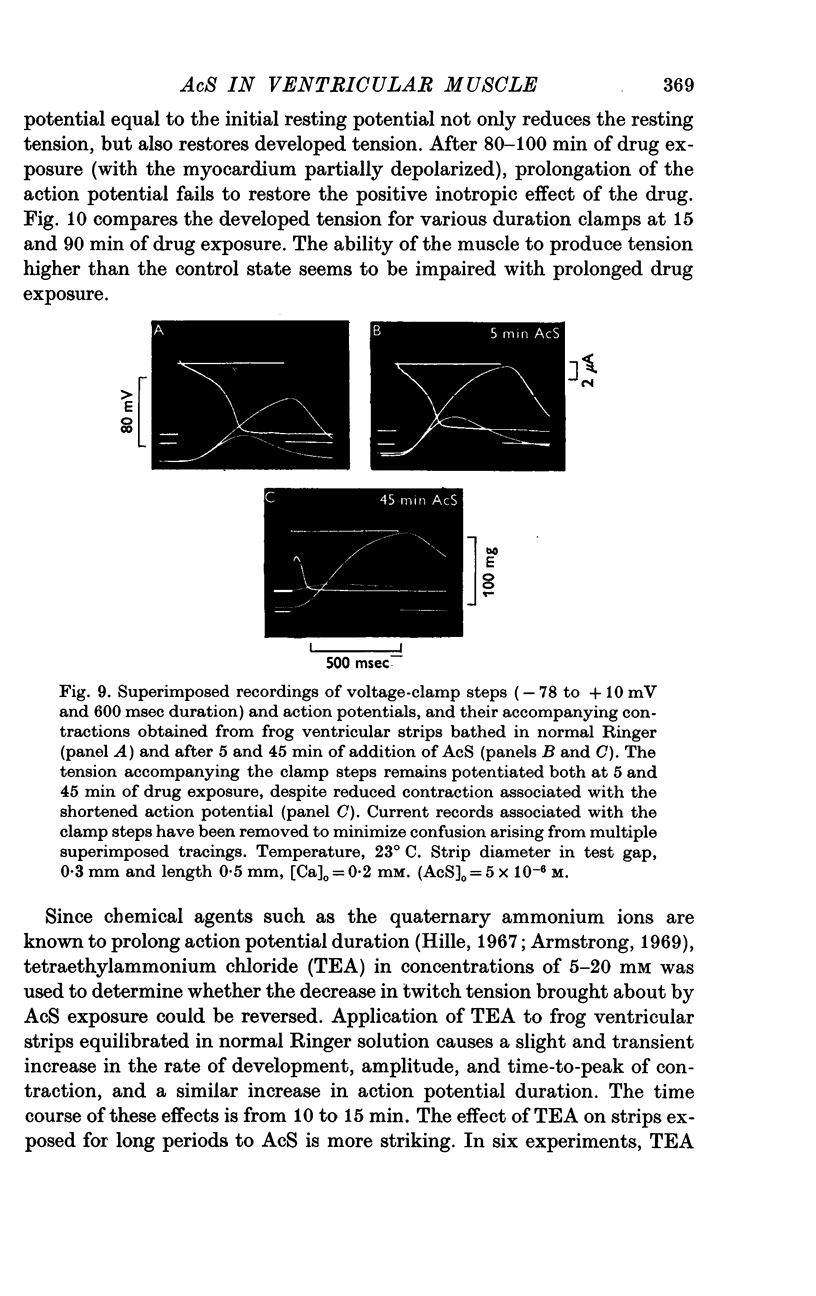

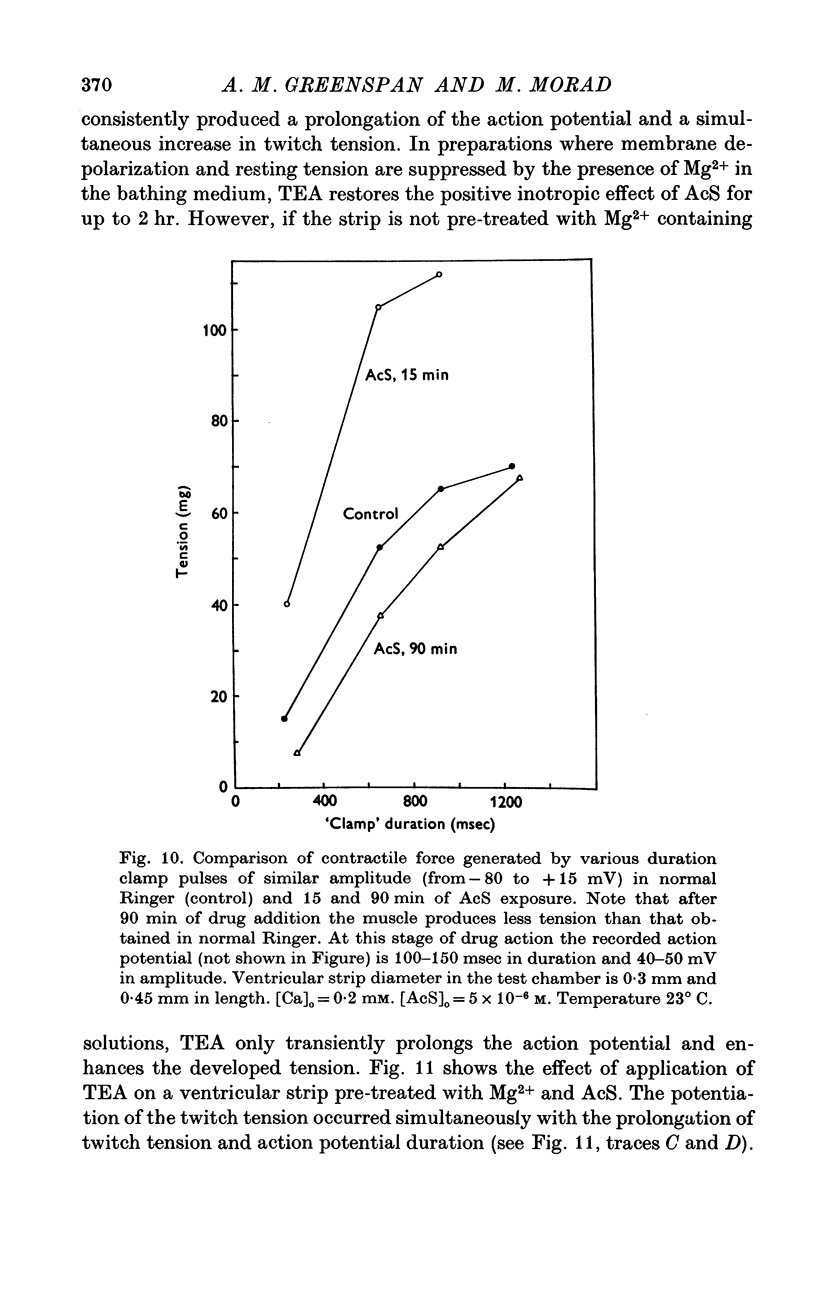

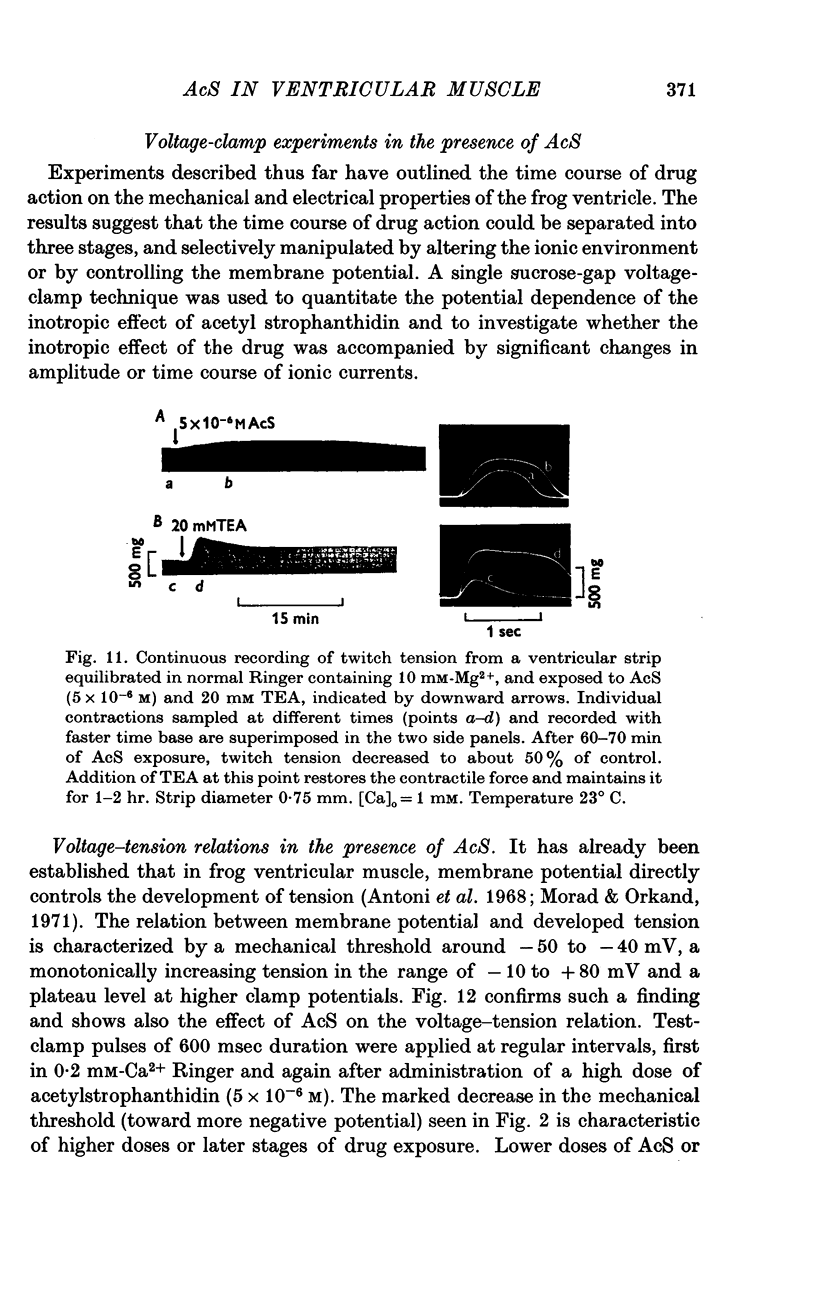

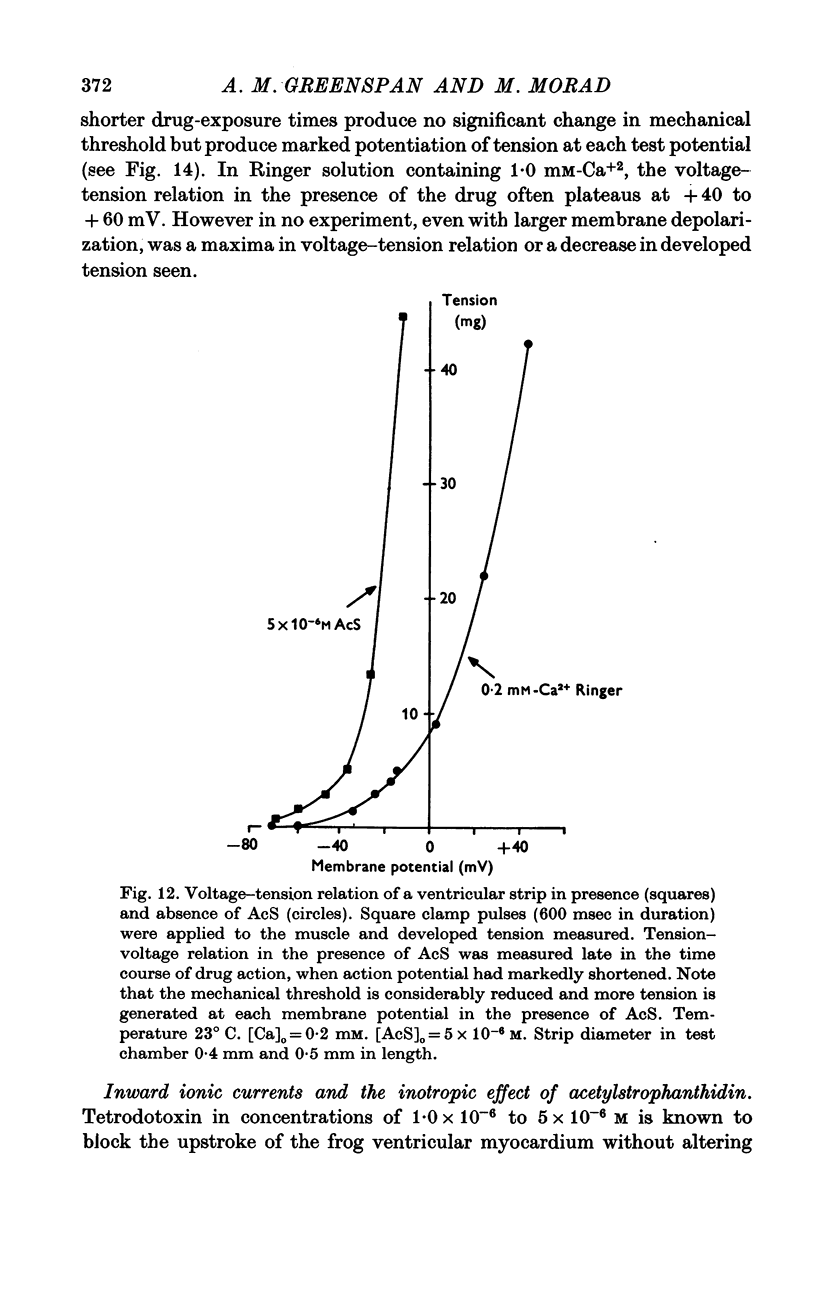

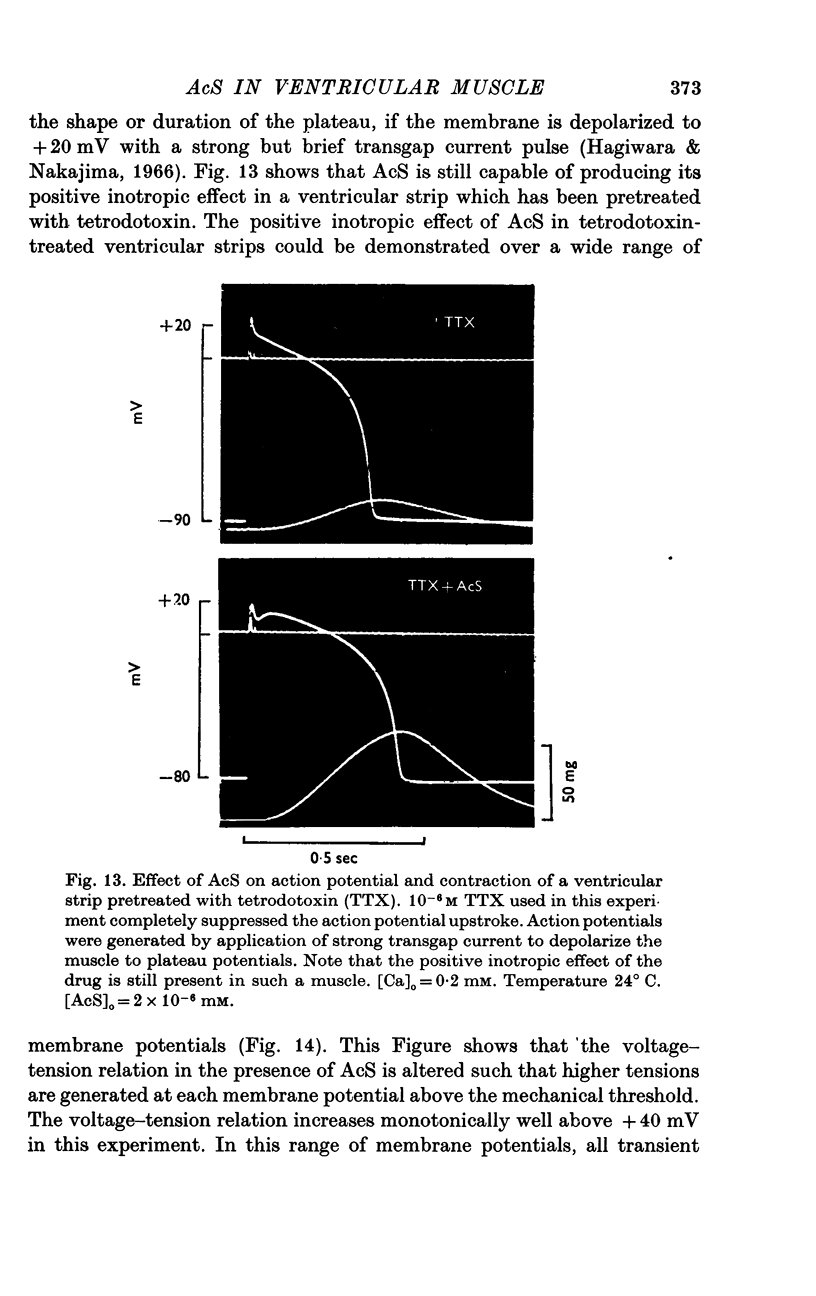

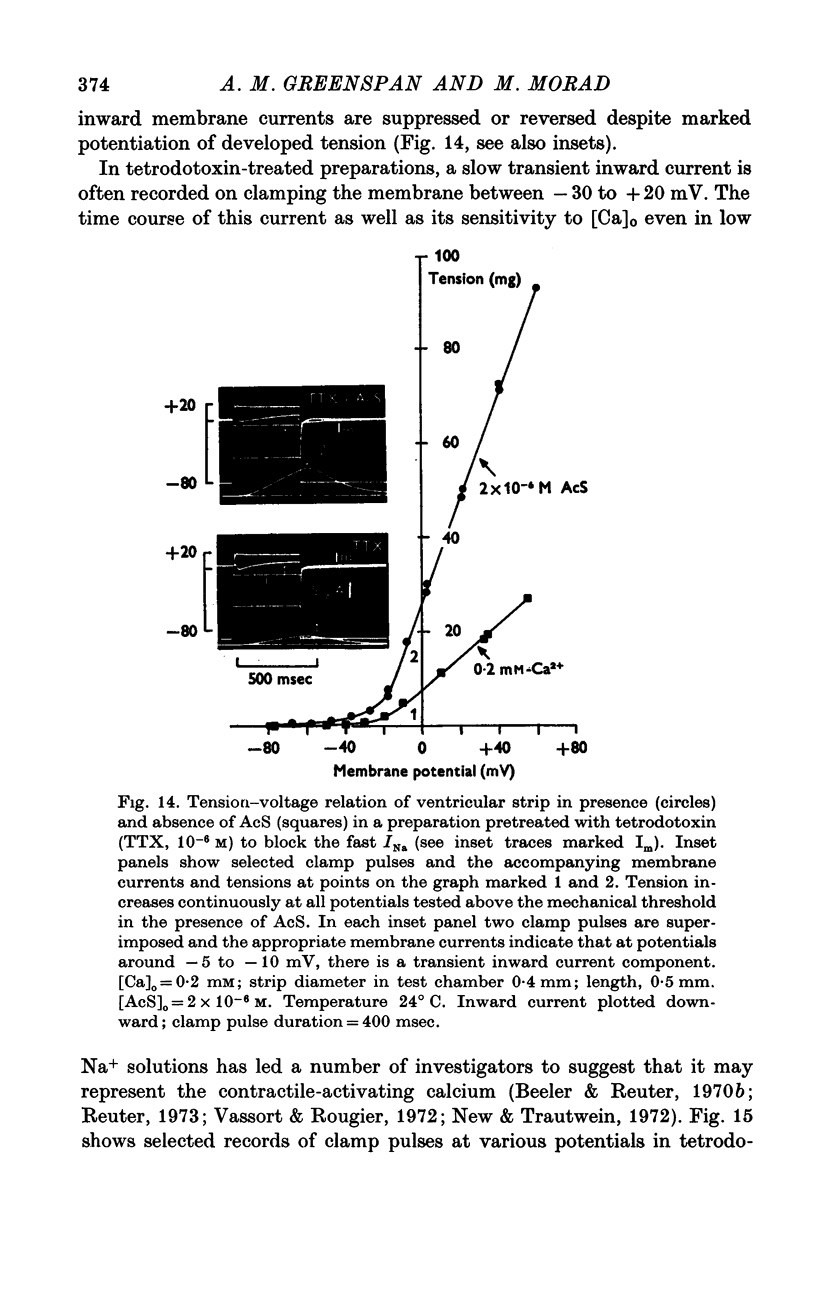

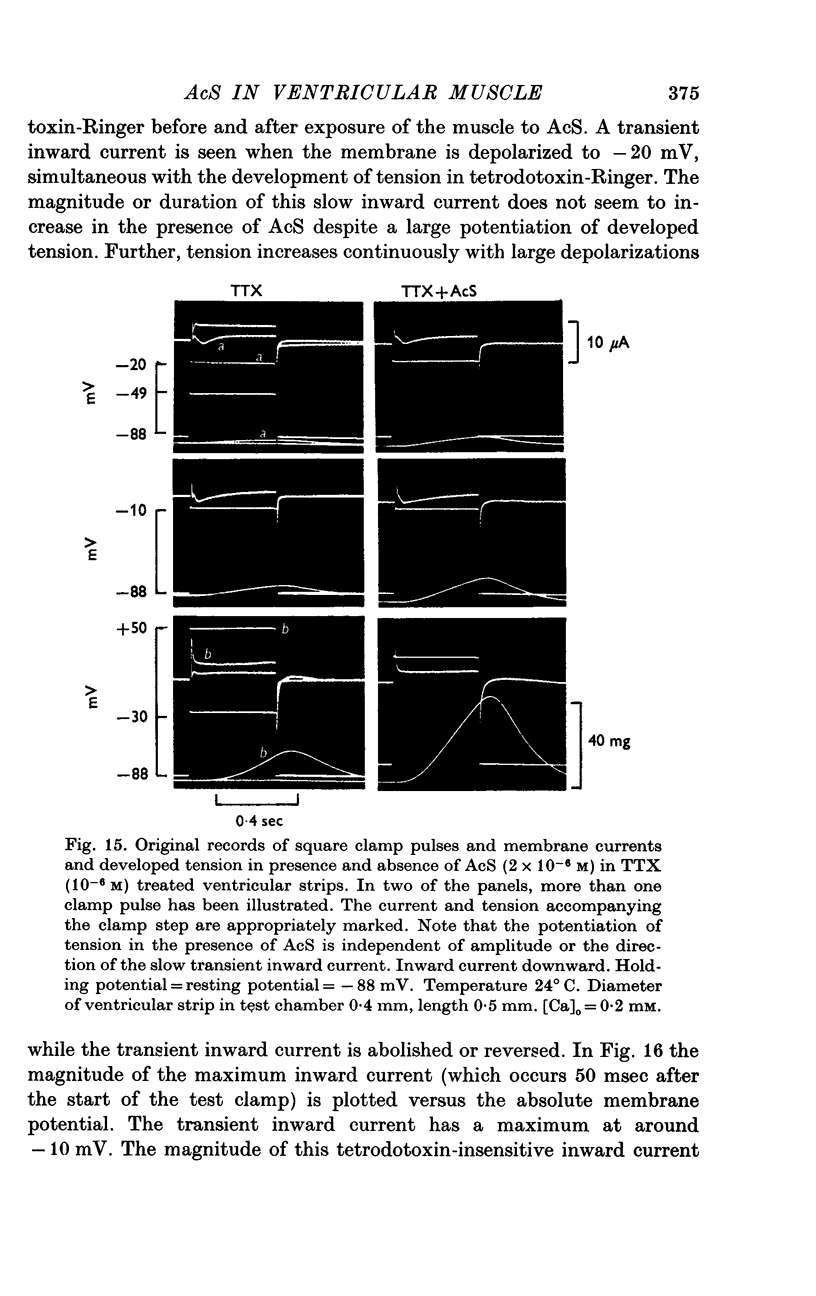

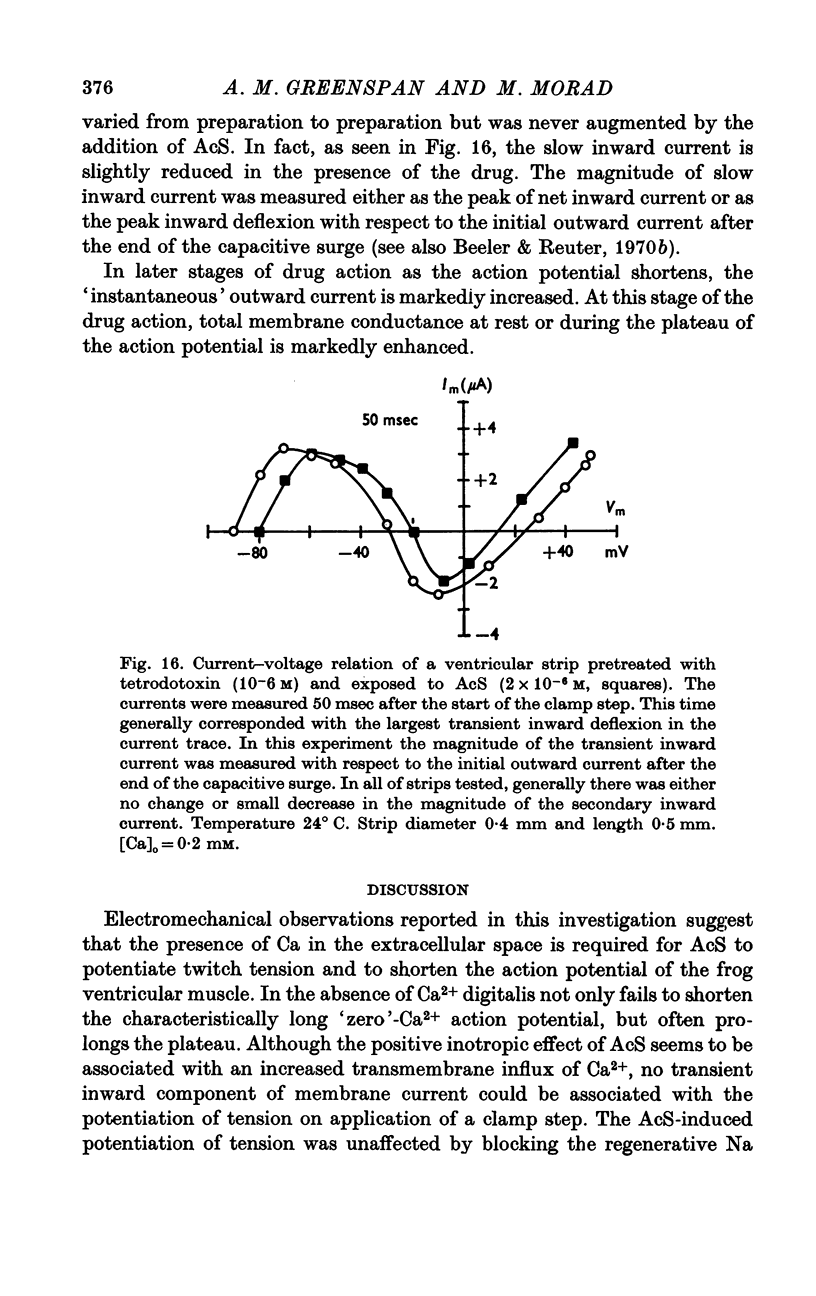

Three phases in the inotropic response of acetyl strophanthidin (AcS) on the electromechnical activity of the frog ventricular myocardium were identified and studied using a single sucrose voltage-clamp technique and other conventional electrophysiological methods. 2. the positive inotropic response of the drug was accompanied by a shift in tension-voltage relation, so that more tension developed with every depolarization step above the mechanical threshold (-50mV). Only at higher drug concentrations or with long exposure times did the mechanical threshold shift to more negative membrane potentials (-60 to-70 mV). 3. In tetrodotoxin-treated muscles AcS produced marked potentiation of twitch tension and an appropriate shift in the tension-voltage relation. 4. the positive inotropic response of the drug was not related to the magnitude of the direction of the fast or slow Na current. 5. in tetrodotoxin-treated ventricular strips the direction or the magnitude of the secondary inward current (ICa or INa) were not related to the inotropic effect of AcS. 6. AcS shortens the action potential markedly during the later stages of its positive inotropic response. When Ca2+ is omitted from the bathing solution AcS not only fails to shorten the action potential, but often prolongs it. 7. The shortening of the action potential in the presence of AcS is accompanied by an increase in the "instantaneous" membrane conductance both at rest and during the time course of the plateau. 8. The decline in the positive inotropic response of the drug was accompanied by the shortening of the action potential. Electrical or chemical prolongation of the action potential restored the full positive inotropic response if the membrane had not depolarized. 9. Membrane depolarization and the development of diastolic tension always occurred at later stages of drug action. Elevation of [Mg+2]degrees to 5 or 10 mM prevented or suppressed the membrane depolarization and the diastolic tension. 10. KCl-induced contractures were potentiated throughout the duration of drug exposure. The tonic component of the contracture tension was markedly elevated especially at later stages of drug action. 11. The experimental evidence suggests that no unitary mechanism could account for multiple actions of acetyl strophanthidin. However, the contributions of the Na pump, the Ca+2 sequestering system, and the K-efflux system to the various stages of drug action are discussed.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Antoni H., Jacob R., Kaufmann R. Mechanische Reaktionen des Frosch- und Säugetiermyokards bei Veränderung der Aktionspotential-Dauer durch konstante Gleichstromimpulse. Pflugers Arch. 1969;306(1):33–57. doi: 10.1007/BF00586610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong C. M. Inactivation of the potassium conductance and related phenomena caused by quaternary ammonium ion injection in squid axons. J Gen Physiol. 1969 Nov;54(5):553–575. doi: 10.1085/jgp.54.5.553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

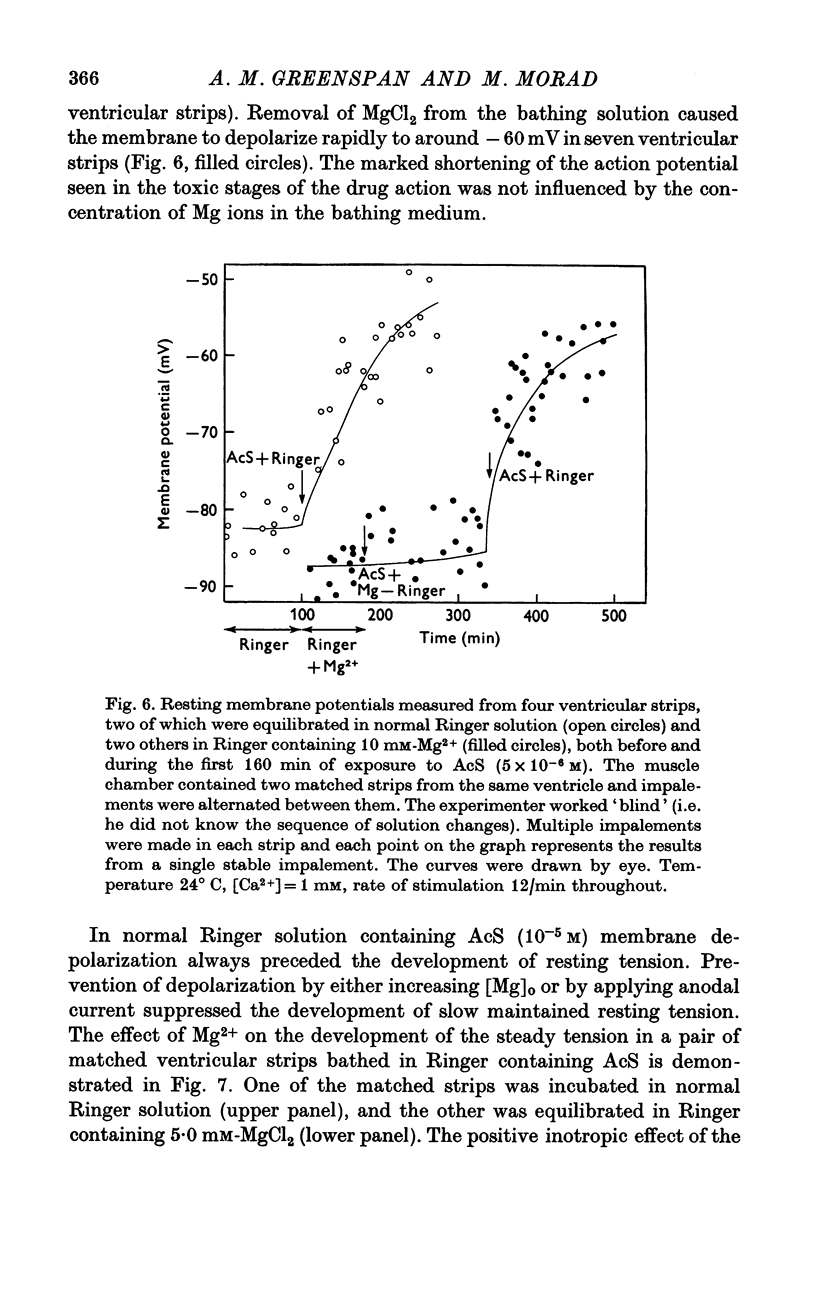

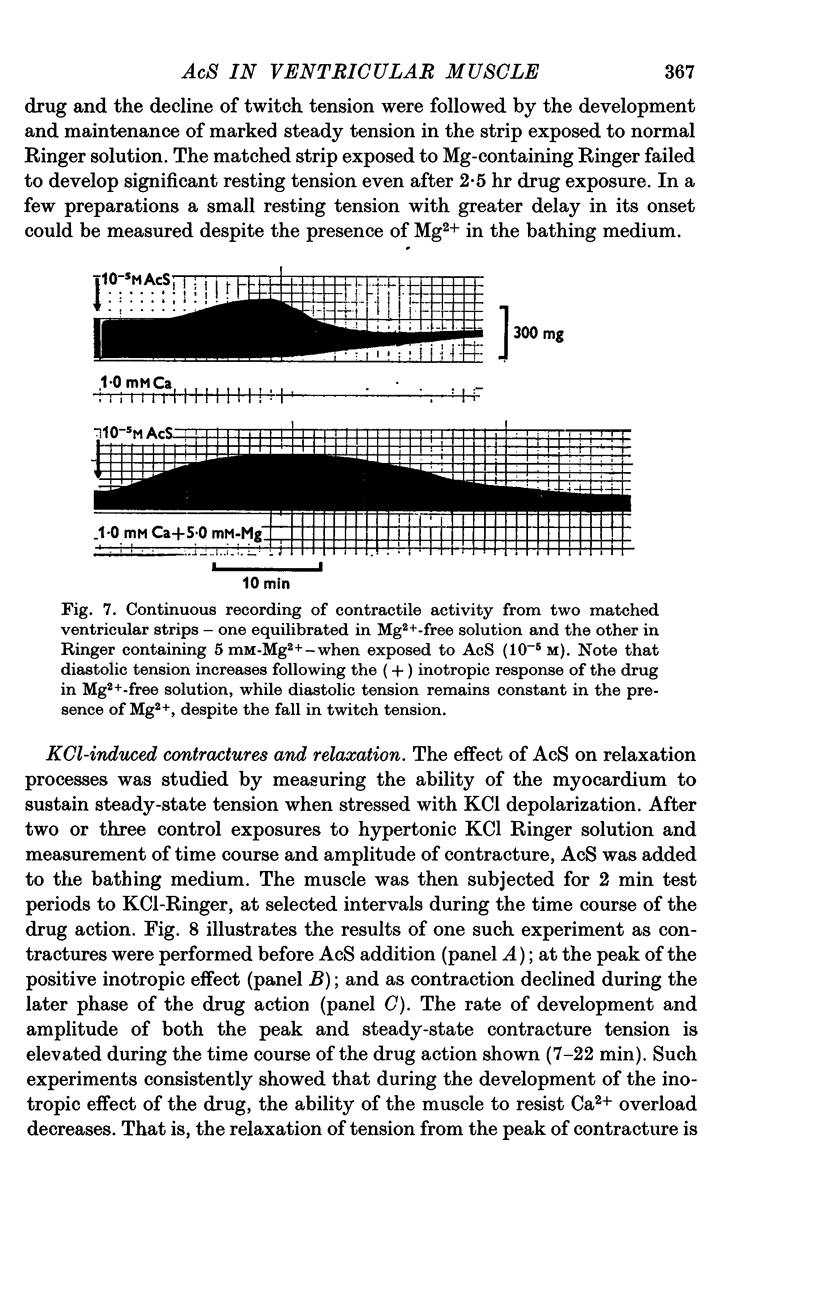

- Baker P. F., Blaustein M. P., Hodgkin A. L., Steinhardt R. A. The influence of calcium on sodium efflux in squid axons. J Physiol. 1969 Feb;200(2):431–458. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1969.sp008702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeler G. W., Jr, Reuter H. Membrane calcium current in ventricular myocardial fibres. J Physiol. 1970 Mar;207(1):191–209. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1970.sp009056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeler G. W., Jr, Reuter H. The relation between membrane potential, membrane currents and activation of contraction in ventricular myocardial fibres. J Physiol. 1970 Mar;207(1):211–229. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1970.sp009057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besch H. R., Jr, Allen J. C., Glick G., Schwartz A. Correlation between the inotropic action of ouabain and its effects on subcellular enzyme systems from canine myocardium. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1970 Jan;171(1):1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carsten M. E. Cardiac sarcotubular vesicles. Effects of ions, ouabain and acetylstrophanthidin. Circ Res. 1967 Jun;20(6):599–605. doi: 10.1161/01.res.20.6.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chimoskey J. E., Gergely J. Effect of norepinephrine, ouabain, and pH on cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 1968 Dec;176(2):289–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta S., Marks B. H. Factors that regulate ouabain-H3 accumulation by the isolated guinea-pig heart. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1969 Dec;170(2):318–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Entman M. L., Cook J. W., Jr, Bressler R. The influence of ouabain and alpha angelica lactone on calcium metabolism of dog cardiac microsomes. J Clin Invest. 1969 Feb;48(2):229–234. doi: 10.1172/JCI105979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GROSSMAN A., FURCHGOTT R. F. THE EFFECTS OF FREQUENCY OF STIMULATION AND CALCIUM CONCENTRATION ON CA45 EXCHANGE AND CONTRACTILITY ON THE ISOLATED GUINEA-PIG AURICLE. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1964 Jan;143:120–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnier D., Rougier O., Gargouïl Y. M., Coraboeuf E. Analyse électrophysiologique du plateau des réponses myocardiques, mise en évidence d'un courant lent entrant en absence d'ions bivalents. Pflugers Arch. 1969;313(4):321–342. doi: 10.1007/BF00593957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gertz E. W., Hess M. L., Lain R. F., Briggs F. N. Activity of the vesicular calcium pump in the spontaneously failing heart-lung preparation. Circ Res. 1967 May;20(5):477–484. doi: 10.1161/01.res.20.5.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons W. R., Fozzard H. A. Voltage dependence and time dependence of contraction in sheep cardiac Purkinje fibers. Circ Res. 1971 Apr;28(4):446–460. doi: 10.1161/01.res.28.4.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOLLAND W. C., SEKUL A. Influence of potassium and calcium ions on the effect of ouabain on Ca45 entry and contracture in rabbit atria. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1961 Sep;133:288–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagiwara S., Nakajima S. Differences in Na and Ca spikes as examined by application of tetrodotoxin, procaine, and manganese ions. J Gen Physiol. 1966 Mar;49(4):793–806. doi: 10.1085/jgp.49.4.793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen O., Skou J. C. A study on the influence of the concentration of Mg 2+ , P i , K + , Na + , and Tris on (Mg 2+ + P i )-supported g-strophanthin binding to (Na + = K + )activated ATPase from ox brain. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1973 Jun 7;311(1):51–66. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(73)90254-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. The selective inhibition of delayed potassium currents in nerve by tetraethylammonium ion. J Gen Physiol. 1967 May;50(5):1287–1302. doi: 10.1085/jgp.50.5.1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson E. A., Lieberman M. Heart: excitation and contraction. Annu Rev Physiol. 1971;33:479–532. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.33.030171.002403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaus W., Lee K. S. Influence of cardiac glycosides on calcium binding in muscle subcellular components. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1969 Mar;166(1):68–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUTTGAU H. C., NIEDERGERKE R. The antagonism between Ca and Na ions on the frog's heart. J Physiol. 1958 Oct 31;143(3):486–505. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1958.sp006073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer G. A. Ion fluxes in cardiac excitation and contraction and their relation to myocardial contractility. Physiol Rev. 1968 Oct;48(4):708–757. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1968.48.4.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer G. A., Serena S. D. Effects of strophanthidin upon contraction and ionic exchange in rabbit ventricular myocardium: relation to control of active state. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1970 Mar;1(1):65–90. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(70)90029-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K. S., Choi S. J. Effects of the cardiac glycosides on the Ca++ uptake of cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1966 Jul;153(1):114–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K. S., Klaus W. The subcellular basis for the mechanism of inotropic action of cardiac glycosides. Pharmacol Rev. 1971 Sep;23(3):193–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascher D., Peper K. Two components of inward current in myocardial muscle fibers. Pflugers Arch. 1969;307(3):190–203. doi: 10.1007/BF00592084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morad M., Orkand R. K. Excitation-concentration coupling in frog ventricle: evidence from voltage clamp studies. J Physiol. 1971 Dec;219(1):167–189. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1971.sp009656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morad M., Trautwein W. The effect of the duration of the action potential on contraction in the mammalian heart muscle. Pflugers Arch Gesamte Physiol Menschen Tiere. 1968;299(1):66–82. doi: 10.1007/BF00362542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New W., Trautwein W. The ionic nature of slow inward current and its relation to contraction. Pflugers Arch. 1972;334(1):24–38. doi: 10.1007/BF00585998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niedergerke R., Orkand R. K. The dependence of the action potential of the frog's heart on the external and intracellular sodium concentration. J Physiol. 1966 May;184(2):312–334. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1966.sp007917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OTSUKA M., NONOMURA Y. The influence of ouabain on the relation between membrane potential and tension in frog heart muscle. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1963 Jul;141:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page S. G., Niedergerke R. Structures of physiological interest in the frog heart ventricle. J Cell Sci. 1972 Jul;11(1):179–203. doi: 10.1242/jcs.11.1.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pretorius P. J., Pohl W. G., Smithen C. S., Inesi G. Structural and functional characterization of dog heart microsomes. Circ Res. 1969 Oct;25(4):487–499. doi: 10.1161/01.res.25.4.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuter H. Divalent cations as charge carriers in excitable membranes. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 1973;26:1–43. doi: 10.1016/0079-6107(73)90016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rougier O., Vassort G., Garnier D., Gargouil Y. M., Coraboeuf E. Existence and role of a slow inward current during the frog atrial action potential. Pflugers Arch. 1969;308(2):91–110. doi: 10.1007/BF00587018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherlag B. J., Helfant R. H., Ricciutti M. A., Damato A. N. Dissociation of the effects of digitalis on myocardial potassium flux and contractility. Am J Physiol. 1968 Nov;215(5):1288–1291. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1968.215.5.1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staley N. A., Benson E. S. The ultrastructure of frog ventricular cardiac muscle and its relationship to mechanism of excitation-contraction coupling. J Cell Biol. 1968 Jul;38(1):99–114. doi: 10.1083/jcb.38.1.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stam A. C., Jr, Weglicki W. B., Gertz E. W., Sonnenblick E. H. A calcium-stimulated, ouabain-inhibited ATPase in a myocardial fraction enriched with sarcolemma. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1973 Apr 16;298(4):927–931. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(73)90396-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassort G., Rougier O. Membrane potential and slow inward current dependence of frog cardiac mechanical activity. Pflugers Arch. 1972;331(3):191–203. doi: 10.1007/BF00589126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILBRANDT W. Zur Frage der Beziehungen zwischen Digitalis-und Kalzium-wirkungen. Wien Med Wochenschr. 1958 Sep 27;108(38-39):809–814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WOODBURY L. A., HECHT H. H. Effects of cardiac glycosides upon the electrical activity of single ventricular fibers of the frog heart, and their relation to the digitalis effect of the electrocardiogram. Circulation. 1952 Aug;6(2):172–182. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.6.2.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E. H., Heppner R. L., Weidmann S. Inotropic effects of electric currents. I. Positive and negative effects of constant electric currents or current pulses applied during cardiac action potentials. II. Hypotheses: calcium movements, excitation-contraction coupling and inotropic effects. Circ Res. 1969 Mar;24(3):409–445. doi: 10.1161/01.res.24.3.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]