Abstract

Various mutant strains were used to examine the regulation and metabolic control of the Calvin-Benson-Bassham (CBB) reductive pentose phosphate pathway in Rhodobacter capsulatus. Previously, a ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RubisCO)-deficient strain (strain SBI/II) was found to show enhanced levels of cbbI and cbbII promoter activities during photoheterotrophic growth in the presence of dimethyl sulfoxide. With this strain as the starting point, additional mutations were made in genes encoding phosphoribulokinase and transketolase and in the gene encoding the LysR-type transcriptional activator, CbbRII. These strains revealed that a product generated by phosphoribulokinase was involved in control of CbbR-mediated cbb gene expression in SBI/II. Additionally, heterologous expression experiments indicated that Rhodobacter sphaeroides CbbR responded to the same metabolic signal in R. capsulatus SBI/II and mutant strain backgrounds.

The Calvin-Benson-Bassham (CBB) reductive pentose phosphate pathway is the primary pathway by which plants, algae, and most photosynthetic bacteria accomplish the fixation of carbon dioxide into organic carbon for subsequent cell metabolism and growth (59). There exist two key enzymes unique to the CBB cycle: ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate (RuBP) carboxylase/oxygenase (RubisCO), which catalyzes the carboxylation of RuBP, and phosphoribulokinase (PRK), which catalyzes a reaction in which the CO2 acceptor molecule, RuBP, is generated via the phosphorylation of ribulose 5-phosphate with ATP. CO2 fixation via the CBB pathway has two major physiological roles in nonsulfur purple photosynthetic bacteria. Under photoautotrophic or chemoautotrophic growth conditions, the key enzymes of the CBB pathway are maximally expressed, with CBB-dependent CO2 fixation being the major synthetic pathway for the synthesis of organic carbon. Substantially lower levels of CBB cycle enzymes, however, are synthesized under photoheterotrophic growth conditions. Under such conditions, basal levels of CBB pathway enzymes perform the important metabolic function of enabling the cell to employ CO2 as a preferred electron sink for excess reducing equivalents generated during photoheterotrophic metabolism (58). Thus, when carbon substrates such as l-malate and succinate are metabolized, the CBB cycle facilitates balancing of the oxidation-reduction potential (redox poise) of the cell (17, 37, 69). Given its different roles in photoheterotrophic and photoautotrophic metabolism, it is not surprising that multiple levels of control influence expression of the CBB system (10, 22, 46, 59, 67).

Enzymes of the CBB pathway are encoded by the cbb genes, which are organized in regulons in both Rhodobacter capsulatus (44, 45) and Rhodobacter sphaeroides (19, 23, 24). For both organisms, there are two major cbb operons: the form I (cbbI) operon, containing form I RubisCO genes (cbbL cbbS), is predominant under autotrophic growth conditions, and the form II (cbbII) operon, containing the form II RubisCO gene (cbbM), is expressed under all growth conditions, albeit at enhanced levels during autotrophic growth. In R. sphaeroides, a LysR-type transcriptional activator gene (cbbR) is situated upstream and is divergently transcribed from the cbbI operon, with CbbR activating expression of both cbbI and cbbII promoters (21). By contrast, R. capsulatus contains a separate cbbR gene upstream and divergently transcribed from each cbb operon (44, 45), with each operon being independently regulated by its cognate CbbR activator (46, 67). CbbR has also been identified and in some cases shown to control cbb expression in many other autotrophic organisms that employ the CBB pathway. These organisms include Rhodospirillum rubrum (16), Thiobacillus ferrooxidans (34), Xanthobacter flavus (39), Ralstonia eutropha (Alcaligenes eutrophus) (71), Chromatium vinosum (65), and Nitrobacter vulgaris (56). LysR-type transcriptional regulators generally utilize a metabolite or coinducer produced by the pathway they regulate (52). The nature of the signal(s) for CbbR has remained unclear, although some “organism-dependent specificity in the coinducer” has been suggested (59). For example, NADPH enhances the binding of X. flavus CbbR (64) while exhibiting no effect on CbbR from R. eutropha (26), R. capsulatus (P. Vichivanives and F. R. Tabita, unpublished results), or R. sphaeroides (J. M. Dubbs and F. R. Tabita, unpublished results).

Previous studies with R. capsulatus suggested that a metabolic signal(s) generated by enzymes encoded by the cbbII genes, downstream of cbbP (PRK) but before cbbM (form II RubisCO), might contribute to the regulation of cbb expression in response to photoheterotrophic and photoautotrophic growth conditions (46, 62). For example, the RubisCO (cbbLS cbbM)-deficient strain SBI/II maximally expressed cbb promoter activities during photoheterotrophic growth which favor activation of the dimethylsulfoxide reductase (DMSOR) system, while a PRK (cbbP)-deficient strain exhibited wild-type control (62). SBI/II thus presented a useful tool to examine the nature of the metabolic signal(s) that could influence CbbR-mediated cbb expression. This work presents in vivo studies that suggest that a product generated by PRK contributes to CbbR-mediated control of cbb expression in an R. capsulatus SBI/II background.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

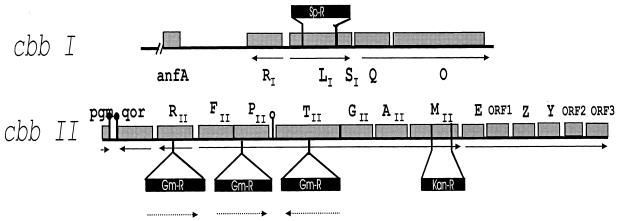

Relevant characteristics of R. capsulatus and Escherichia coli strains as well as plasmids used or constructed in this study are listed in Table 1. Insertional mutagenesis of cbbP, cbbT, and cbbRII in R. capsulatus SBI/II and SBI is illustrated in Fig. 1.

TABLE 1.

Relevant characteristics of bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s) | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| R. capsulatus | ||

| SB1003 | Rifr derivative of wild-type strain B10 | 74 |

| SBI | cbbLS::Spr, derivative of SB1003 | 46 |

| SBII | cbbM::Spr, derivative of SB1003 | 46 |

| SBI/II | cbbLS::Spr, cbbM::Kmr derivative of SB1003 | 46 |

| SBI/IIP | cbbP::Gmr derivative of SBI/II | This work |

| SBI/IIT | cbbT::Gmr derivative of SBI/II | This work |

| SBI/IIRII | cbbRII::Gmr derivative of SBI/II | This work |

| SBI/P | cbbP::Gmr derivative of SBI | This work |

| E. coli | ||

| JM109 | recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi hsdR17 supE44 relA1 Δ(lac-proAB) | 73 |

| S17-1λpir | Strr Tpr Spcr, λpir and mobilizing factors on chromosome | 47 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pUC19 | Apr | 68 |

| pK18, pK19 | Kmr, pUC derivatives | 49 |

| pUC1813, pUC1318 | Apr, pUC derivative with hybrid multiple cloning site | 33 |

| pRK2013 | Kmr, helper plasmid for triparental conjugation | 18 |

| pXLB | Tcr, R. capsulatus cbbI translational promoter fusion to lacZ | 46 |

| pXFB | Tcr, R. capsulatus cbbII translational promoter fusion to lacZ | 46 |

| pVKC1 | Tcr, R. sphaeroides cbbI translational promoter fusion to lacZ, lacking cbbR | 9 |

| pVKD1 | Tcr, R. sphaeroides cbbI translational promoter fusion to lacZ, containing cbbR | 9 |

| pRPS-1 | Tcr, broad-host range expression vector containing Rhodospirillum rubrum cbbM promoter and cbbR gene | 15 |

| pRPS::FII(S2)-I | pRPS-1 containing the R. capsulatus form II RubisCO gene, cbbM | 45 |

| pRPS::429 | pRPS-1 containing the R. sphaeroides aldolase and form I RubisCO genes, cbbAIcbbL cbbS | 15 |

| pRPS::329NΔ | pRPS-1 containing the R. sphaeroides form I RubisCO genes, cbbL cbbS | D. L. Falcone and F. R. Tabita, unpublished data |

| pRPS-MCS-3 | Broad-host range expression vector containing the Rhodosprillum rubrum cbbM promoter and cbbR gene | Smith and Tabita, unpublished |

| pVK-cbbR | Complementation vector containing R. capsulatus cbbRII | 46 |

| pK18FIIB2.3 | pK18 containing the R. capsulatus cbbRII′, cbbF, and cbbP′ genes on a 2.3-kb BamHI fragment | 45 |

| pK18FIIS4.4 | pK18 containing the R. capsulatus pgm, qor, cbbRII, cbbF, and cbbP′ genes on a 4.4 SalI fragment | 45 |

| pK18FIIS4 | pK18 containing R. capsulatus cbbP′, cbbT, cbbG, and cbbA′ genes on a 4-kb SalI fragment | 45 |

| pUC1813::RsPIA | pUC1813 containing the R. sphaeroides cbbPI gene on a 1-kb AvaI fragment | 46 |

| pTC5603 | Tcr, mobilizable suicide vector containing multiple EcoRI sites | 46 |

| pJPTC | Tcr, mobilizable suicide vector containing a single EcoRI site located in the multiple cloning site | Y. Qian and F. R. Tabita, unpublished data |

| pUC1318-Gm | pUC1318 containing a Gmr cassette cloned as a 1.6 kb HindIII-SphI fragment from plasmid pFRK-1 | Smith and Tabita, unpublished |

| pRPS-cbbP | pRPS-MCS-3 containing the R. sphaeroides cbbPI gene cloned as a 1-kb AvaI-SmaI fragment from plasmid pUC1813::RsPIA into XhoI-blunt-ended PstI sites | This work |

| pRPS-cbbTG | pRPS-MCS-3 containing the R. capsulatus cbbT and cbbG genes cloned as a 4-kb SalI fragment from plasmid pK18FIIS4 into XhoI site | This work |

| pRPS-cbbG | pRPS-MCS-3 containing the R. capsulatus cbbG gene cloned as a 1.8-kb KpnI-SalI fragment from plasmid p19-cbbGA′ into KpnI-XhoI sites | This work |

| p19-cbbGA′ | pUC19 containing the R. capsulatus cbbT′, cbbG, and cbbA′ genes cloned as a 1.8-kb BamHI-SalI fragment from plasmid pK18FIIS4 | This work |

| pK18-cbbPGm | pK18FIIB2.3 with a Gmr cassette cloned into the XhoI site of cbbP as a 1.6-kb SalI fragment from pUC1318-Gm | This work |

| pTC5603-cbbPGm | 3.8-kb KpnI-XbaI fragment of plasmid pK18-cbbPGm containing the disrupted cbbP gene cloned into pTC5603 | This work |

| p19-cbbT′ | pUC19 containing the R. capsulatus cbbP′ and cbbT′ genes cloned as a 2.0-kb BamHI fragment from plasmid pK18FIIS4 | This work |

| p19-cbbTGm | p19-cbbT′ with a Gmr cassette cloned into the XhoI site of cbbT as a 1.6-kb SalI fragment from pUC1318-Gm | This work |

| pJPTC-cbbTGm | p19-cbbTGm cloned into vector pJPTC by linearizing with EcoRI | This work |

| pK18-cbbRGm | pK18FIIS4.4 with a Gmr cassette cloned into the EcoRV site of cbbRII as a 1.6-kb SmaI fragment from pUC1318-Gm | This work |

| pJPTC-cbbRGm | pK18-cbbRGm cloned into vector pJPTC by linearizing with EcoRI | This work |

FIG. 1.

cbbI and cbbII gene clusters of R. capsulatus. The sites of gene disruptions in the mutant strains are indicated. Solid arrows indicate direction of transcription; dotted arrows indicate orientation of the gentamicin resistance cassette used to inactivate the respective genes. The genes encoding the enzymes of the CBB pathway in R. capsulatus are organized in two operons, each preceded by a separate cbbR gene (encoding a LysR-type transcriptional regulator). cbbL cbbS encodes form I RubisCO, while cbbM encodes form II RubisCO. cbbM is clustered with genes encoding other enzymes of the CBB pathway: cbbF (fructose 1,6/sedoheptulose 1,7-bisphosphatase), cbbP (phosphoribulokinase), cbbT (transketolase), cbbG (glyceraldehydes-3-phosphate dehydrogenase), cbbA (fructose 1,6-bisphosphate aldolase), and cbbE (epimerase). The cbb genes are oriented with respect to other familiar genes in this organism: pgm, phosphoglucomutase; qor, quinol oxidoreductase; anfA, regulator for the alternative nitrogenase genes.

Media and growth conditions.

E. coli strains were grown aerobically on LB medium (1) at 37°C with appropriate antibiotic selection. Photoheterotrophic (0.4% [wt/vol] dl-malate) and photoautotrophic (1.5% CO2, 98.5% H2) cultures of R. capsulatus were grown anaerobically in Ormerod's medium as previously described (42) supplemented with 1 μg of thiamine/ml (15, 43). The nitrogen source during photoheterotrophic growth was provided as either 30 mM ammonia or 6.8 mM l-glutamate. The antibiotics used for selection of the R. capsulatus strains were as follows: rifampin, 100 μg/ml; kanamycin, 5 μg/ml; spectinomycin, 10 μg/ml; gentamicin, 10 μg/ml; and tetracycline, 3 μg/ml for stock cultures or 0.5 μg/ml for plasmid maintenance during photosynthetic growth and 0.3 μg/ml for screening exconjugant sensitivity. For E. coli, the concentrations of antibiotics for plasmid maintenance were as follows: ampicillin, 100 μg/ml; kanamycin, 10 μg/ml; gentamicin, 10 μg/ml; and tetracycline, 10 μg/ml. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was utilized at 30 mM.

Cell extracts and enzyme assays.

Culture samples (10 to 30 ml) were harvested in late log phase (optical density at 660 nm, 0.9 to 1.2), washed in buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]), and disrupted by sonication. The resultant cell debris was removed by centrifugation for 15 min at 4°C. β-Galactosidase activity was measured as previously reported (46); the production of o-nitrophenol (40) was continuously measured by monitoring the increase in absorbance at 405 nm over 10 min. RubisCO activity was assayed as previously described by measuring RuBP-dependent 14CO2 fixation into acid-stable material (70). PRK activity was measured by previously described protocols (57) except that ribulose 5-phosphate was generated from ribose 5-phosphate by the addition of 5 U of phosphoriboisomerase (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, Mo.). The following CBB enzymatic activities were measured spectrophotometrically on a Beckman DU-70 spectrophotometer by using a coupled enzyme assay following established protocols: fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase (FBPase) (20), transketolase (60), and ribulose 5-phosphate-3-epimerase (35). Protein concentrations were determined with a protein assay dye binding reagent (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.) with bovine serum albumin as a standard.

Western immunoblot analysis of form I and form II RubisCO.

Samples were prepared and subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis as previously described (36). A low cross-linker ratio (acrylamide to bisacrylamide, 150/1) was utilized in 18% polyacrylamide gels. Following electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Immobilon-NC; Millipore, Bedford, Mass.) (63) using a Bio-Rad Transblot semidry cell. Polyclonal antibodies raised against Synechococcus sp. PCC 6301 RubisCO and R. sphaeroides form II RubisCO at a 1:3,000 dilution were utilized to follow the synthesis of form I and form II RubisCO, respectively. Western blots were developed by following protocols of the Vistra ECF fluorescent detection system (Amersham Corporation, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, England). Blots were visualized with a Storm 840 imaging system (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, Calif.).

DNA manipulations and conjugation techniques.

All routine DNA manipulations were carried out following standard protocols (1). R. capsulatus chromosomal DNA was isolated as previously described (25). Southern blotting procedures were carried out with Hybond N+ (Amersham, Arlington Heights, Ill.) membranes following previously established protocols supplied with GeneScreen Plus membranes (NEN, Dupont, Boston, Mass.). Hybridizations, labeling of probes, and development of blots were conducted by following protocols of the Vistra ECF fluorescent detection system (Amersham Corporation). Blots were visualized with a Storm 840 imaging system. For complementation experiments, E. coli strain JM107 (73) containing the mobilizable helper plasmid pRK2013 (18) was used in triparental matings. To generate mutant strains, derivatives of plasmid pJP5603 were conjugated into R. capsulatus strain SBI/II or SBI using E. coli S17-λpir (11, 47).

Construction of R. capsulatus mutant strains by insertional mutagenesis. (i) Strain SBI/IIP (cbbLS cbbM cbbP).

cbbP was inactivated by insertion of a gentamicin resistance cassette as a 1.56-kb SalI fragment isolated from plasmid pUC1318-Gm into the unique XhoI site of cbbP in plasmid pK18FIIB2.3, generating plasmid pK18-cbbPGm. The 3.8-kb KpnI-XbaI fragment of pK18-cbbPGm, containing the disrupted cbbP gene, was cloned into the suicide vector pTC5603, generating plasmid pTC5603-cbbPGm. pTC5603-cbbPGm was mobilized into R. capsulatus strain SBI/II from E. coli strain S17-λpir. Of the 1,350 Gmr exconjugants screened, 4 were found to be Tets. Southern blot analysis of chromosomal DNA indicated that each of the Gmr Tets isolates resulted from double recombination.

(ii) Strain SBI/IIT (cbbLS cbbM cbbT).

In order to isolate a unique XhoI site in the cbbT gene, a 2.0-kb BamHI fragment containing a truncated cbbT gene was subcloned from plasmid pK18FIIS4 into plasmid pUC19, generating plasmid p19-cbbT′. Inactivation of cbbT was achieved by insertion of a gentamicin resistance cassette as a 1.56-kb SalI fragment isolated from pUC1318-Gm into the XhoI site of cbbT in p19-cbbT′, generating p19-cbbTGm. A cointegrate of p19-cbbTGm and the suicide plasmid pJPTC was formed after linearizing the DNA with EcoRI, resulting in plasmid pJPTC-cbbTGm. E. coli strain S17-λpir was used to mobilize pJPTC-cbbTGm into R. capsulatus strain SBI/II. Of the 700 Gmr exconjugants screened, 1 was found to be Tets and confirmed to be a double crossover by Southern blot analysis of chromosomal DNA.

(iii) Strain SBI/IIRII (cbbLS cbbM cbbRII).

Inactivation of cbbRII was accomplished by insertion of a gentamicin resistance cassette as a 1.56-kb SmaI fragment from plasmid pUC1318-Gm into the unique EcoRV site of cbbRII in plasmid pK18FIIS4.4, generating plasmid pK18-cbbRGm. pJPTC-cbbRGm was generated by forming a cointegrate between pK18-cbbRGm and the suicide vector pJPTC, after linearizing the DNA with EcoRI. pJPTC-cbbRGm was mobilized into R. capsulatus strain SBI/II by using E. coli strain S17-λpir. Of the 500 Gmr exconjugants, 162 were found to be Tets; 8 were chosen for Southern blot analysis of chromosomal DNA, and all were confirmed to be double crossovers. One of these strains was chosen for all subsequent experiments.

(iv) Strain SBI/P (cbbLS cbbP).

Inactivation of cbbP was achieved by mobilizing plasmid pTC5603-cbbPGm from E. coli strain S17-λpir into R. capsulatus strain SBI. Of the 4,100 Gmr exconjugants screened, 1 was found to be Tets. Southern blot analysis of chromosomal DNA indicated that the Gmr Tets isolate resulted from double recombination.

RESULTS

Construction and phenotypes of cbb mutant strains.

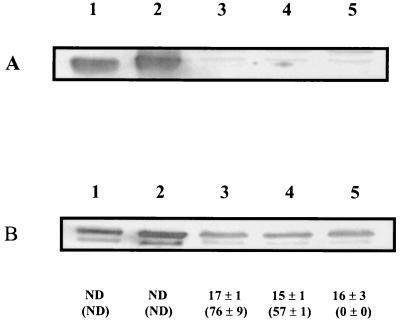

Strains SBI/IIP (cbbLS cbbM cbbP), SBI/IIT (cbbLS cbbM cbbT), and SBI/IIRII (cbbLS cbbM cbbRII) were constructed as described in Materials and Methods, with the orientation of the gentamicin resistance cassette as shown in Fig. 1. This cassette does not contain a transcription terminator. Thus, provided that the cassette is in the correct orientation, expression of genes downstream of the cassette can occur. The orientation of the Gmr interposon inserted into cbbP was such that transcriptional read-through could occur into the cbb genes located directly downstream of cbbP (Fig. 1). To address the issue of polarity of the Gm interposon insertion in cbbP on downstream gene expression, a cbbP mutant was constructed in R. capsulatus form I (cbbLS) RubisCO deletion strain SBI (see Materials and Methods). For this strain, levels of form II RubisCO protein and activity were examined in order to detect expression of genes downstream of the Gmr interposon insertion site. The levels of RubisCO and PRK activities in wild-type strain SB1003 were comparable to those of SBI (Fig. 2B, lanes 3 and 4) during photoheterotrophic growth with DMSO. In addition, form II RubisCO was synthesized and no form I RubisCO polypeptides were detected in extracts of either strain (Fig. 2, lanes 3 and 4). Strain SBI/P exhibited levels of RubisCO activity similar to those of wild-type strain SB1003 (Fig. 2B, lanes 3 and 5), and form II RubisCO polypeptides were detected during photoheterotrophic growth with DMSO (Fig. 2B, lane 5). As expected, no PRK activity or form I RubisCO polypeptide was detected in SBI/P (Fig. 2, lane 5). These data suggested transcriptional read-through of genes downstream of the Gmr interposon insertion site in cbbP.

FIG. 2.

Immunoblot analysis and levels of RubisCO and PRK activities in strain SBI/P during photoheterotrophic growth. Antibodies raised against form I Synechococcus 6301 RubisCO (A) and R. sphaeroides form II RubisCO (B) were utilized. Approximately 5 μg of protein was added per lane (A and B). Levels of RubisCO activity (below the lanes) and PRK activity (below the lanes, in parentheses) (both in nanomoles per minute per milligram) were determined from three independent cultures grown photoautotrophically (1.5%CO2-98.5% H2) (lane 1) or photoheterotrophically in the presence of DMSO (lanes 3 to 5). Lanes 1, extract from wild-type strain SB1003; lanes 2, purified Synechococcus sp. strain 6301 RubisCO (A) and R. sphaeroides form II RubisCO (B); lanes 3, extract from SB1003; lanes 4, extract from SBI; lanes 5, extract from SBI/P. ND, not determined.

Under photoheterotrophic growth conditions, strains SBI/IIP, SBI/IIT, and SBI/IIRII behaved similarly to parent strain SBI/II; i.e., no growth was achieved in the absence of DMSO with ammonia as the nitrogen source. Additionally, no growth was achieved in SBI/P under photoheterotrophic conditions when ammonia was used as the nitrogen source; however, when cultures were supplemented with DMSO, growth of SBI/P comparable to that of parent strain SBI was observed.

Metabolic control of the CBB pathway in R. capsulatus.

Previous physiological studies suggested that a metabolic signal produced by enzymes encoded by the R. capsulatus cbbII genes, in particular the product of a gene downstream of cbbP, but before cbbM (form II RubisCO), contributes to regulation of the CBB pathway (46, 62). To address this issue, insertional mutagenesis was performed on strain SBI/II, whereby specific genes (see orientation in Fig. 1) encoding PRK (cbbP), transketolase (cbbT), and the LysR-type transcriptional activator CbbRII (cbbRII) were inactivated (see Materials and Methods).

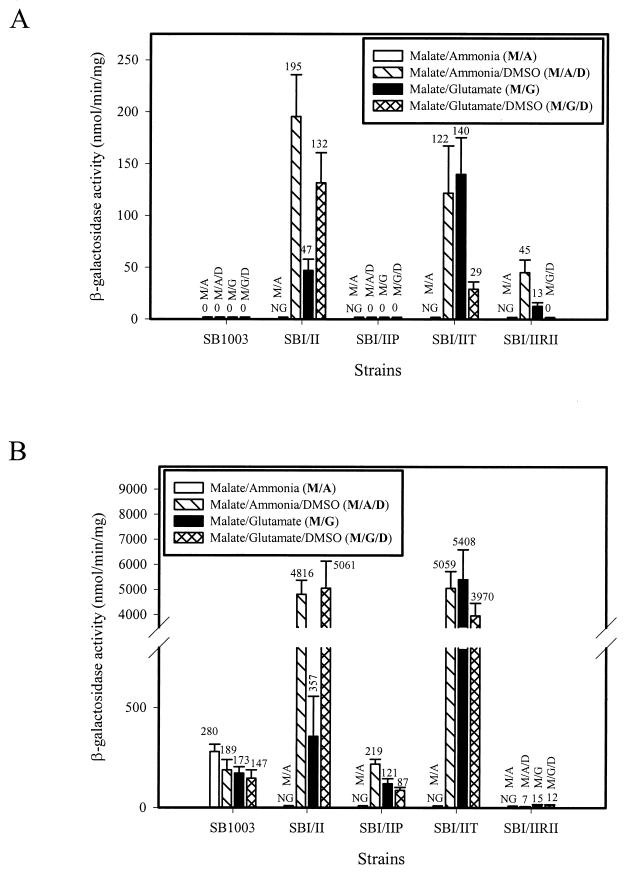

Form I RubisCO is not synthesized under photoheterotrophic growth conditions when malate is used as the carbon source in wild-type R. capsulatus (19, 45, 55). Accordingly, wild-type strain SB1003 exhibited no cbbI promoter activity for all photoheterotrophic growth conditions examined. Strain SBI/II exhibited cbbI promoter activity during photoheterotrophic growth and levels were substantially enhanced during growth with DMSO (Fig. 3A) as previously reported (62). Indeed, promoter activities in SBI/II approached the levels obtained in the wild type under photoautotrophic growth conditions, which is known to be a growth condition that favors maximum cbb transcription (46, 61, 62). However, when a knockout mutation in the cbbP gene was constructed in this strain (creating strain SBI/IIP), as observed in the wild type, no cbbI promoter activity was noted for all photoheterotrophic growth conditions (Fig. 3A). Strain SBI/IIRII exhibited levels of cbbI promoter activity approximately fourfold lower than those of strain SBI/II for malate-ammonia-DMSO and malate-glutamate growth conditions and no promoter activity for growth with malate-glutamate-DMSO (Fig. 3A). Compared to strain SBI/II, strain SBI/IIT also exhibited high levels of cbbI promoter activity during growth with malate-ammonia-DMSO. By contrast, however, levels were greatly enhanced compared to wild-type levels during growth in the absence of DMSO (malate-glutamate) and decreased 4.8-fold during malate-glutamate-DMSO growth (Fig. 3A). For cbbII promoter activity, for all photoheterotrophic growth conditions tested, activity was readily detected in wild-type strain SB1003. However, SBI/II exhibited a 13- to 14-fold induction of cbbII promoter activity when cultures were supplemented with DMSO (Fig. 3B) (62). Like the cbbI promoter results, SBI/IIP regained wild-type control of its cbbII promoter activity during photoheterotrophic growth, although slightly less activity was observed with malate-glutamate-DMSO than for the wild-type (Fig. 3B). These results were similar to what occurred in PRK deletion strains of wild-type R. capsulatus (62). SBI/IIT enhanced cbbII promoter activity to levels comparable to those for SBI/II under photoheterotrophic growth conditions when cultures were supplemented with DMSO. However, for this strain, enhanced levels of promoter activity were obtained in cultures grown in the absence of DMSO (malate-glutamate) (Fig. 3B). Levels of cbbII promoter activity in strain SBI/IIRII were considerably reduced for all the photoheterotrophic growth conditions tested (Fig. 3B) and were at levels observed with R. capsulatus cbbRII strains (46, 67).

FIG. 3.

cbbI::lacZ (A) and cbbII::lacZ (B) promoter activity during photoheterotrophic growth of R. capsulatus strains. β-Galactosidase activities were determined from three to nine independent cultures assayed in duplicate. NG, no growth during photoheterotrophic conditions with ammonia as the nitrogen source in the absence of DMSO.

The promoter-fusion studies suggested that the levels of activity of individual enzymes encoded by the cbbII operon genes might also be affected in the different strains. Thus, under photoheterotrophic growth conditions in the presence of DMSO, strain SBI/II possessed levels of PRK activity that were comparable to the induced levels observed in wild-type strain SB1003 after photoautotrophic (1.5% CO2-98.5% H2) growth (Table 2). Enhanced levels of PRK activity were also found in strain SBI/IIT; moreover, SBI/II and SBI/IIT also had enhanced levels of FBPase activity compared to SB1003 after photoheterotrophic growth in the presence of DMSO (Table 2). However, like the cbbII promoter activity results (Fig. 3B), a knockout of cbbP (SBI/IIP) resulted in wild-type levels of FBPase and transketolase activity during photoheterotrophic growth with DMSO; decreased levels of FBPase activity were observed in SBI/IIRII, and near-wild-type levels of transketolase activity were also observed (Table 2). The wild-type level of transketolase activity in SBI/IIRII is probably due to the fact that R. capsulatus and R. sphaeroides contain an additional chemoheterotrophic transketolase, TktA, which plays a role in the CBB pathway in the absence of CbbT (5, 7); thus, perhaps TktA contributes to the levels of transketolase activity in SBI/IIRII. Somewhat lower levels of epimerase activity were observed in SBI/II and SBI/IIP than in SB1003 during photoheterotrophic growth with DMSO (Table 2); whether the levels of epimerase activity reflect transcription from a third cbb promoter (43) or activity from an additional epimerase remains to be established.

TABLE 2.

CBB enzymatic activities during photoheterotrophic growth with ammonia and DMSO

| Strain | Sp act (nmol/min/mg)a

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FBPase (cbbF) | PRK (cbbP) | Transketolase (cbbT/tktA) | RubisCO (cbbM) | Epimerase (cbbE) | |

| SB1003 | 19 ± 5 | 101 ± 24 | 230 ± 42 | 39 ± 8 | 431 ± 80 |

| SB1003b | ND | 1,446 ± 148 | ND | 153 ± 15 | ND |

| SBI/II | 211 ± 39 | 1,122 ± 303 | 748 ± 159 | 0 ± 0 | 199 ± 27 |

| SBI/II::pRPSFIIS2-1 | 69 ± 15 | 185 ± 36 | 228 ± 57 | 11 ± 4 | 208 ± 15 |

| SBI/IIP | 15 ± 4 | 0 ± 0 | 203 ± 46 | 0 ± 0 | 316 ± 69 |

| SBI/IIP::pRPScbbP | 16 ± 2 | 31 ± 5 | ND | 0 ± 0 | ND |

| SBI/IIP::pRPScbbTG | 17 ± 3 | 0 ± 0 | 353 ± 87 | 0 ± 0 | ND |

| SBI/IIP::pRPScbbG | 14 ± 4 | 0 ± 0 | ND | 0 ± 0 | ND |

| SBI/IIP::pRPS-429 | 20 ± 4 | 0 ± 0 | ND | 5 ± 1 | ND |

| SBI/IIP::pRPS-329NΔ | 9 ± 3 | 0 ± 0 | ND | 7 ± 4 | ND |

| SBI/IIT | 424 ± 64 | 1,362 ± 249 | ND | 0 ± 0 | ND |

| SBI/IIRII | 7 ± 2 | 4 ± 3 | 269 ± 54 | 0 ± 0 | ND |

Values are averages ± standard errors from three to five independent cultures. ND, not determined.

Photoautotrophically grown (1.5% CO2-98.5% H2-ammonia).

Vectors containing R. sphaeroides or R. capsulatus cbb genes on a broad-host-range plasmid (containing the Rhodospirillum rubrum cbbM promoter and cbbR gene) were constructed (Table 1). When each plasmid (pRPS-cbbP, pRPS-cbbTG, pRPS-cbbG, pRPS-429, and pRPS-329NΔ), containing the respective cbb gene(s), was mated into SBI/IIP, levels of FBPase activity were not significantly altered during photoheterotrophic growth with DMSO (Table 2). SBI/II, containing pRPSFIIS2-1, with the cbbM gene from R. capsulatus (encoding form II RubisCO), possessed decreased levels of PRK and transketolase activity, to near wild-type levels; moreover, levels of FBPase activity decreased significantly (Table 2). These results indicated that the restoration of a functional CBB pathway in SBI/II (pRPSFIIS2-1) (containing R. capsulatus form II RubisCO) diminished the accumulation of some important metabolite that influenced regulation when RubisCO activity was blocked. This putative compound would appear to substantially contribute to up-regulated gene expression in SBI/II during photoheterotrophic growth with DMSO (62).

R. capsulatus SBII, which has no form II RubisCO, had been shown to synthesize form I RubisCO during photoheterotrophic growth, unlike wild-type strains (46). Thus, in order to compensate for the absence of form II RubisCO, a signal is processed to somehow allow SBII to synthesize compensatory levels of form I RubisCO. Consistent with these observations, cbbI promoter activity became detectable in SBII after photoheterotrophic growth with ammonia (Table 3). This cbbI promoter activity was observed under photoheterotrophic growth conditions with either ammonia or glutamate as the nitrogen source in the absence or presence of DMSO. Wild-type strain SB1003, as previously shown (62), exhibited no cbbI promoter activity (Table 3). SBII enhanced levels of cbbII promoter activity 7.2-fold compared to SB1003 during malate-ammonia growth, while levels were enhanced 3.4-fold during malate-ammonia-DMSO growth and 2.4- to 2.5-fold during malate-glutamate growth regardless of the presence of DMSO (Table 3). SBII also showed enhanced levels of PRK activity (2.5- to 2.6-fold) compared to SB1003 during photoheterotrophic growth in the presence or absence of DMSO (data not shown). Similar to the situation with SBI/II (Table 2), upon the restoration of a complete CBB pathway via complementation with the R. capsulatus cbbM gene (encoding form II RubisCO) using plasmid pRPS::FII(S2)-I, decreased levels of PRK activity were obtained (data not shown).

TABLE 3.

Levels of cbbI and cbbII promoter activities in strain SBII during photoheterotrophic growth

| Promoter | Strain | β-Galactosidase activity (nmol/min/mg) ona

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MA | MAD | MG | MGD | ||

| cbbI::lacZ | SB1003 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| SBII | 10 ± 3 | 8 ± 1 | 10 ± 2 | 5 ± 1 | |

| cbbII::lacZ | SB1003 | 137 ± 6 | 187 ± 82 | 197 ± 43 | 154 ± 39 |

| SBII | 985 ± 230 | 629 ± 58 | 496 ± 12 | 364 ± 45 | |

MA, malate-ammonia; MAD, malate-ammonia-DMSO; MG, malate-glutamate; MGD, malate-glutamate-DMSO. Data are means ± standard errors from three independent cultures.

R. sphaeroides CbbR responds to the R. capsulatus SBI/II background.

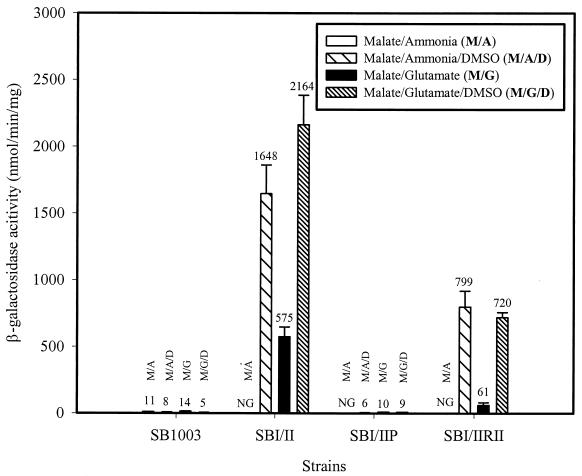

Control mechanisms involved in phototrophic redox homeostasis and cbb expression in R. capsulatus differ from those in R. sphaeroides (61, 62, 67). Although the cbbI and cbbII operons are independently regulated in R. sphaeroides, CbbR has been shown to be involved in the regulation of both operons (21, 32). By contrast, each cbb operon is independently regulated by its cognate CbbR activator in R. capsulatus (46, 67). Moreover, in R. sphaeroides, cbbI and cbbII promoters are both expressed during photoheterotrophic growth (9, 72), while in R. capsulatus, only the cbbII promoter is expressed during photoheterotrophic growth with malate as the carbon source (45, 46, 62). In view of these differences, and to determine whether the R. sphaeroides cbbI promoter and its cognate cbbR gene were subject to the same regulatory signals as the R. capsulatus system, heterologous expression experiments were performed. An R. sphaeroides translational cbbI::lacZ promoter fusion vector (also containing the R. sphaeroides cbbR gene) (9) was examined in the R. capsulatus SBI/II and SBI/II mutant strain background. β-Galactosidase activity levels were enhanced three- to fourfold in the presence of DMSO when R. capsulatus SBI/II was grown under photoheterotrophic growth conditions with glutamate as the nitrogen source (Fig. 4). Likewise, no significant R. sphaeroides cbbI promoter activity was found in wild-type strain SB1003 and strain SBI/IIP under the tested photoheterotrophic growth conditions (Fig. 4). In contrast to the lack of R. capsulatus cbbI promoter activity (Fig. 3A), β-galactosidase activity was obtained with the R. sphaeroides cbbI promoter fusion in SBI/IIRII during photoheterotrophic growth with malate-glutamate-DMSO, to similar levels during growth with malate-ammonia-DMSO. Levels of activity were decreased 12- to 13-fold in SBI/IIRII in the absence of DMSO (Fig. 4). No significant β-galactosidase activity was detected in any strain when R. sphaeroides cbbI promoter fusion vector pVKC1 (lacking a complete R. sphaeroides cbbR gene) (9) was used (data not shown). Aside from indicating that neither endogenous CbbRI or CbbRII R. capsulatus proteins could activate transcription of the R. sphaeroides cbbI promoter, these results are important because they show that the R. sphaeroides cbbI promoter and its cognate CbbR protein were subject to the same control as the R. capsulatus cbb promoters in the R. capsulatus SBI/II background. Thus, the metabolic signal produced in SBI/II is able to affect both homologous (R. capsulatus) and heterologous (R. sphaeroides) CbbR-mediated cbb transcription.

FIG. 4.

Promoter activity using an R. sphaeroides cbbR-cbbI::lacZ promoter fusion (pVKD1) (9) in R. capsulatus strains during photoheterotrophic growth. β-Galactosidase activities were determined from three independent cultures assayed in duplicate. NG, no growth in the absence of an alternative electron acceptor.

Finally, levels of PRK activity were monitored after complementation experiments were performed with SBI/IIRII during photoheterotrophic growth in the presence of DMSO (Table 4). Consistent with previous findings (Table 2), levels of PRK activity were enhanced (12-fold) in SBI/II compared to the wild type under photoheterotrophic growth conditions in the presence of DMSO. Considerably reduced levels were observed in SBI/IIRII, and of course no activity was found in SBI/IIP. R. sphaeroides cbbR was shown to complement and restore the ability of SBI/IIRII to provide SBI/II levels of PRK activity, since the addition of pVKD1 (with a complete R. sphaeroides cbbR gene), but not pVKC1 (with a truncated R. sphaeroides cbbR gene), yielded high levels of PRK activity. Likewise, complementation with R. capsulatus cbbRII resulted in high levels of PRK activity while addition of the Rhodospirillum rubrum cbbR gene (Table 4) or the R. capsulatus cbbRI gene did not (data not shown).

TABLE 4.

Complementation of R. capsulatus strain SBI/IIRII during photoheterotrophic growth with DMSO (malate-ammonia-DMSO)

| Strain | PRK activity (nmol/min/mg)a |

|---|---|

| SB1003 | 76 ± 12 |

| SBI/II | 929 ± 195 |

| SBI/IIP | 0 |

| SBI/IIRII | 4 ± 2 |

| SB1003::pVKC1b | 90 ± 15 |

| SBI/II::pVKC1 | 824 ± 160 |

| SBI/IIP::pVKC1 | 0 |

| SBI/IIRII::pVKC1 | 4 ± 3 |

| SB1003::pVKD1c | 40 ± 4 |

| SBI/II::pVKD1 | 724 ± 191 |

| SBI/IIP::pVKD1 | 0 |

| SBI/IIRII::pVKD1 | 1,086 ± 204 |

| SBI/IIRII::pVK-CbbRd | 628 ± 93 |

| SBI/IIRII::pRPS-MCS3e | 4 ± 1 |

PRK activity was determined from three to five independent cultures.

Contains truncated R. sphaeroides cbbR gene.

Contains intact R. sphaeroides cbbR gene.

Contains intact R. capsulatus cbbRII gene.

Contains intact Rs. rubrum cbbR gene.

DISCUSSION

Insight as to metabolic factors that might control the function of the CBB pathway is limited due to the complexity of the system; the CBB cycle involves up to 13 enzymes acting on 16 metabolites in a complex network of reactions, and it is also dependent on a ready source of ATP and reducing equivalents, as well as the removal of metabolites to be used in further biosynthetic pathways involved in cell growth (48). PRK has been suggested to be the target enzyme for in vivo control of the rate of CO2 fixation (8); indeed, changes in the flux of CO2 fixation are thought to be regulated in part through changes in the levels of RuBP, the product of PRK activity, in leaves of sugar beet (53).

LysR-type transcriptional activators generally require a coinducer, and this effector ligand is often a metabolite of the pathway regulated (52). With respect to the cbb operons of R. capsulatus, previous studies have shown that these operons belong to independent CbbR regulons (44, 46, 67). It has also been suggested that under phototrophic growth conditions, different inducer molecules could bind to the respective CbbR proteins or, alternatively, that CbbRI and CbbRII could bind the same inducer molecule but with different affinities (46). The present investigation strongly indicated a potential regulatory role of a metabolite generated by PRK function (either ADP, RuBP, or a derivative thereof). Presumably, this compound might act as a specific effector in mediating the ability of CbbRI and CbbRII to influence control of cbb expression in SBI/II. Previous physiological studies (46, 62) and genetic studies reported here have thus stimulated us to direct attention to the ability of such metabolites to influence CbbR function in vitro. It is clear, however, from the present studies that the enhanced levels of cbbII promoter activity in SBI/II were dependent on CbbRII, since inactivation of the cbbRII gene in SBI/II resulted in decreased basal levels of cbbII expression. Levels of PRK activity in SBI/IIRII were approximately 4% of wild-type levels during photoheterotrophic growth in the presence of DMSO (Table 2). Perhaps, the lower levels of PRK activity in SBI/IIRII contributed to the approximate fourfold reduction of cbbI promoter activity in this strain during photoheterotrophic growth. It is also apparent from mutagenesis studies presented here and elsewhere (62) that a separate metabolic signal (besides RuBP, ADP, or a derivative thereof) might be involved in the control of cbbII expression during photoheterotrophic growth, since SBI/IIP exhibited wild-type control of cbbII expression (Fig. 3B); additionally, cbbP strains generated by a polar mutation exhibited wild-type control of cbbII promoter activity during photoheterotrophic growth (62). Obviously, there exists an alternative signal that must be involved in CbbRII-mediated regulation of cbbII expression during photoheterotrophic growth. Presumably, this hypothetical signal is generated via processes separate from the function of structural genes downstream of and including cbbP. Again, if one assumes that the regulatory compound is generated by the CBB pathway, a potential metabolite candidate could possibly be the product generated by CbbF (fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase), namely, fructose 6-phosphate, since the cbbF gene is upstream of cbbP and is not inactivated by the polar effect of a cbbP mutation. Additional work obviously needs to be completed to reinforce these hypotheses. Certainly, the ability of LysR-type transcriptional activators to bind two separate inducer molecules is not unprecedented. For example, BenM, a LysR-type transcriptional activator involved in the regulation of benzoate degradation in Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1, has been shown to utilize two compounds of the pathway, benzoate and cis,cis-muconate, as effector molecules (6).

It is clear that both cbb operons are independently regulated in R. capsulatus 46, 62; this study) and R. sphaeroides (24, 27, 28). The present study shows that cbbI and cbbII promoter activities of R. capsulatus are both substantially enhanced during photoheterotrophic growth in the presence of DMSO in the RubisCO-deficient strain SBI/II. Indeed, the enhanced levels observed reached those obtained by the wild-type during photoautotrophic (1.5% CO2-98.5% H2) growth (62). It is thus apparent that a signal was generated in SBI/II that led to the deregulation and control of cbbI and cbbII expression under photoheterotrophic growth conditions in the presence of DMSO. Furthermore, this enhanced cbbI and cbbII promoter activity was lost when cbbP was inactivated (Fig. 3 and Table 2), causing a regain of the wild-type pattern of control. Consequently, we hypothesize that a metabolic signal generated by PRK function (ADP, RuBP, or a metabolite derived from RuBP) serves as a positive effector to enable CbbRI and CbbRII to enhance cbb gene expression in SBI/II. Such an effector also provides a common metabolic signal for communication between the two operons. Because effector compounds for LysR type regulators are usually metabolites unique to the pathway, we suggest that RuBP, or something directly derived from RuBP, is the most likely candidate for the coinducer or effector. The coincidence of the levels of cbb expression with levels of PRK function in SBI/II is certainly supportive of this idea. Moreover, upon restoration of a functional CBB pathway (by complementation with the R. capsulatus form II RubisCO gene), levels of PRK activity decreased 6.1-fold, which presumably diminished the intracellular levels of a metabolite that accumulated when RubisCO activity was blocked; this could contribute to the 3.1-fold decrease in FBPase activity and the 3.3-fold decrease in transketolase activity exhibited by SBI/II containing a functional form II RubisCO (Table 2). Additionally, levels of PRK activity appeared to be coincident with cbb induction in response to a photoautotrophic growth environment (1.5% CO2-98.5% H2) in SBI/II containing form II RubisCO (data not shown). From these findings, it appears that PRK function, and the levels of RuBP (or a metabolite derived from RuBP), appeared to contribute to CbbR-mediated cbbI and cbbII expression in SBI/II.

Further communication between the two cbb operons is illustrated by R. capsulatus SBII; unlike the wild type, SBII synthesized form I RubisCO under photoheterotrophic growth conditions with malate as the carbon source (46). This compensatory increase in the expression of the cbbI operon in SBII was reflected by enhanced levels of cbbI promoter activity, compared to the wild type, during photoheterotrophic growth with either ammonia or glutamate as the nitrogen source in the absence or presence of DMSO (Table 3). Somehow a signal was received in SBII to allow the organism to compensate for the absence of form II RubisCO. This compensation resulted in the synthesis of form I RubisCO under conditions where the cbbI operon was normally not functional. It should be noted, however, that no signal for compensatory form I RubisCO synthesis was evident in various cbbP mutant strains, where a polar effect on cbbM also causes form II RubisCO not to be synthesized (46, 62). SBII also exhibited enhanced levels of cbbII promoter and enhanced PRK activity levels compared to the wild type under photoheterotrophic growth conditions (Table 3; also data not shown). Again, it is tempting to speculate that a signal for the compensatory effect on cbbI expression in SBII is, in part, mediated by enhanced levels of a metabolite generated by PRK function during photoheterotrophic conditions, as is the case for SBI/II. In R. sphaeroides, the intracellular level of RuBP or a metabolite derived from RuBP also appears to be important for cbb expression control. Thus, similar to R. capsulatus, when cbbM was disrupted by a polar mutation in cbbAII, levels of PRK activity were enhanced over wild-type levels during photoheterotrophic growth in R. sphaeroides (27; D. L. Falcone, J. L. Gibson, and F. R. Tabita, unpublished data). Finally, recent experiments performed by S. A. Smith in this laboratory indicated that enhanced levels of cbbI and cbbII promoter activities were manifest in an R. sphaeroides RubisCO deficient strain during photoheterotrophic growth in the presence of DMSO (malate-ammonia-DMSO) (S. A. Smith and F. R. Tabita, unpublished observations). Since we have shown that R. sphaeroides cbbI promoter activity was up-regulated and dependent on R. sphaeroides CbbR in an R. capsulatus SBI/IIRII background, similar to R. capsulatus cbbI, there appears to be a common and important role for the product of PRK in both organisms. The different abilities of R. sphaeroides CbbR, R. capsulatus CbbRI or CbbRII, and Rhodospirillum rubrum CbbR to complement R. capsulatus SBI/IIRII might reflect differences in the specificity of the coinducer(s) used, the nature of the DNA binding motifs, or affinities for binding motifs or might even reflect the requirement for specific interactions with additional factors. Obviously additional studies need to be performed in order to resolve these multiple possibilities; however, preliminary in vitro studies indicate that RuBP might have differential capabilities to influence the binding of CbbRI and CbbRII to its cognate promoter sites (66).

Finally, there are both known and unknown additional regulatory components and factors that are involved in controlling expression of the CBB system (9, 10, 67). For example, there is the RegB/A(PrrB/A) two-component signal transduction system, originally shown to control transcription of key operons involved in photosystem biosynthesis in R. capsulatus (30, 41), R. sphaeroides (13), and probably other nonsulfur purple photosynthetic bacteria (38) via a mechanism that shows organism-dependent specificity (3, 13, 14, 41, 54). More recently, RegB/A(PrrB/A) was found to function as a global two-component regulatory system (31), as it controls, among other processes, CO2 fixation in R. capsulatus (67) and R. sphaeroides (10, 50), nitrogen fixation in R. capsulatus (12, 61), R. sphaeroides (31, 51), Rhodospirillum rubrum (31), and Bradyrhizobium japonicum (4), H2 oxidation in R. capsulatus (12), and the regulation of formaldehyde oxidation in R. sphaeroides (2). With regard to the cbb system of R. capsulatus, Reg/Prr is involved in activation of cbbI promoter expression as well as maximal expression of the cbbII promoter under photoautotrophic growth conditions (67). It was further suggested that alteration of the oxidation-reduction potential of the ubiquinone pool, by activation of the DMSOR system, enables a redox signal to be transmitted to the Reg/Prr system, which in turn regulates the expression of key operons involved in phototrophic metabolism, including the cbb regulons of R. capsulatus (62). Perhaps, the enhanced levels of cbb expression observed during photoheterotrophic growth with DMSO in SBI/II is a result of the cooperative regulation by both the LysR-type regulatory activators CbbRI and CbbRII and the global response regulator RegA. It is thus conceivable that a synergistic interaction between CbbR and RegA occurs at the respective cbbI and cbbII promoters in SBI/II; the binding of RuBP (or a derivative thereof) to CbbRI and CbbRII could then somehow enhance the effects of RegA control at these promoters. Synergistic control of gene expression by a response regulator of a two-component regulatory system and a LysR-type transcriptional regulator is certainly not unprecedented and has been shown, for example, to be important for control of the eps operon of Ralstonia solanacearum (29). Ultimately, further in vitro studies will need to be performed to address these and other possibilities.

Acknowledgments

We thank Janet Gibson and James Dubbs, The Ohio State University, for helpful suggestions and advice concerning this work and Cedric Bobst for kind assistance and reagents necessary for transketolase assays.

This work was supported by NIH grant GM45404 from the U.S. Public Health Service.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl (ed.). 1987. Current protocols in molecular biology. Greene Publishing Associates and Wiley Interscience, New York, N.Y.

- 2.Barber, R. D., and T. J. Donohue. 1998. Pathways for transcriptional activation of a glutathione-dependent formaldehyde dehydrogenase gene. J. Mol. Biol. 280:775-784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauer, C. E., and T. H. Bird. 1996. Regulatory circuits controlling photosynthesis gene expression. Cell 85:5-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauer, E., K. Thomas, H. M. Fischer, and H. Hennecke. 1998. Expression of the fixR-nifA operon in Bradyrhizobium japonicum depends on a new response regulator, RegR. J. Bacteriol. 180:3853-3863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen, J. H., J. L. Gibson, L. A. McCue, and F. R. Tabita. 1991. Identification, expression, and deduced primary structure of transketolase and other enzymes encoded within the form II CO2 fixation operon of Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Biol. Chem. 30:20447-20452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collier, L. S., G. L. Gaines III, and E. L. Neidle. 1998. Regulation of benzoate degradation in Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1 by BenM, a LysR-type transcriptional activator. J. Bacteriol. 180:2493-2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de-Sury d'Aspremont, R., B. Toussaint, and P. M. Vignais. 1996. Isolation of Rhodobacter capsulatus transketolase: cloning and sequencing of its structural tktA gene. Gene 169:81-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dijkhuizen, L., and W. Harder. 1984. Current views on the regulation of autotrophic carbon dioxide fixation via the Calvin cycle in bacteria. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 50:473-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dubbs, J. M., and F. R. Tabita. 1998. Two functionally distinct regions upstream of the cbbI operon of Rhodobacter sphaeroides regulate gene expression. J. Bacteriol. 180:4903-4911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dubbs, J. M., T. H. Bird, C. E. Bauer, and F. R. Tabita. 2000. Interaction of CbbR and RegA* transcription regulators with the Rhodobacter sphaeroides cbbI promoter-operator region. J. Biol. Chem. 275:19224-19230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duport, C., C. Meyer, I. Naud, and Y. Jouanneau. 1994. A new gene expression system based on a fructose-dependent promoter from Rhodobacter capsulatus. Gene 145:103-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elsen, S., W. Dischert, A. Colbeau, and C. E. Bauer. 2000. Expression of uptake hydrogenase and molybdenum nitrogenase in Rhodobacter capsulatus is coregulated by the RegB-RegA two-component regulatory system. J. Bacteriol. 182:2831-2837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eraso, J. M., and S. Kaplan. 1994. prrA, a putative response regulator involved in oxygen regulation of photosynthesis gene expression in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol. 176:32-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eraso, J. M., and S. Kaplan. 1995. Oxygen-insensitive synthesis of the photosynthetic membranes of Rhodobacter sphaeroides: a mutant histidine kinase. J. Bacteriol. 177:2695-2706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Falcone, D. L., and F. R. Tabita. 1991. Expression of endogenous and foreign ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase-oxygenase (RubisCO) genes in a RubisCO deletion mutant of Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol. 173:2099-2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Falcone, D. L., and F. R. Tabita. 1993. Complementation analysis and regulation of CO2 fixation gene expression in a ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase deletion strain of Rhodospirillum rubrum. J. Bacteriol. 175:5066-5077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferguson, S. J., J. B. Jackson, and A. G. McEwan. 1987. Anaerobic respiration in the rhodospirillaceae: characterisation of pathways and evaluation of roles in redox balancing during photosynthesis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 46:117-143. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Figurski, D., and D. R. Helinski. 1979. Replication of an origin-containing derivative of the plasmid RK2 dependent on a plasmid function provided in trans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76:1648-1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gibson, J. L., and F. R. Tabita. 1977. Isolation and preliminary characterization of two forms of ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase from Rhodopseudomonas capsulata. J. Bacteriol. 132:818-823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gibson, J. L., and F. R. Tabita. 1988. Localization and mapping of CO2 fixation genes within two gene clusters in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol. 170:2153-2158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gibson, J. L., and F. R. Tabita. 1993. Nucleotide sequence and functional analysis of CbbR, a positive regulator of the Calvin cycle operons of Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol. 175:5778-5784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gibson, J. L., and F. R. Tabita. 1996. The molecular regulation of the reductive pentose phosphate pathway in proteobacteria and cyanobacteria. Arch. Microbiol. 166:141-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gibson, J. L., J. H. Chen, P. A. Tower, and F. R. Tabita. 1990. The form II fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase and phosphoribulokinase genes form part of a large operon in Rhodobacter sphaeroides: primary structure and insertional mutagenesis analysis. Biochemistry 29:8085-8093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gibson, J. L., D. L. Falcone, and F. R. Tabita. 1991. Nucleotide sequence, transcriptional analysis and expression of genes encoded within the form I CO2 fixation operon of Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Biol. Chem. 266:14646-14653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grimberg, J., S. Maguire, and L. Belluscio. 1989. A simple method for the preparation of plasmid and chromosomal E. coli DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 17:8893.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grzeszik, C., T. Jeffke, J. Schaferjohann, B. Kusian, and B. Bowien. 2000. Phosphoenolpyruvate is a signal metabolite in transcriptional control of the CO2 fixation operons in Ralstonia eutropha. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 3:311-320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hallenbeck, P. L., R. Lerchen, P. Hessler, and S. Kaplan. 1990. Roles of CfxA, CfxB, and external electron acceptors in regulation of ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase expression in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol. 172:1736-1748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hallenbeck, P. L., R. Lerchen, P. Hessler, and S. Kaplan. 1990. Phosphoribulokinase activity and regulation of CO2 fixation critical for photosynthetic growth of R. sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol. 172:1749-1761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang, J., W. Yindeeyoungyeon, R. P. Garg, T. P. Denny, and M. A. Schell. 1998. Joint transcriptional control of xpsR, the unusual signal integrator of the Ralstonia solanacearum virulence gene regulatory network, by a response regulator and a LysR-type transcriptional activator. J. Bacteriol. 180:2736-2743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Inoue, K., J. L. Kouadio, C. S. Mosley, and C. E. Bauer. 1995. Isolation and in vitro phosphorylation of sensory transduction components controlling anaerobic induction of light harvesting and reaction center gene expression in Rhodobacter capsulatus. Biochemistry 42:391-396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Joshi, H. M., and F. R. Tabita. 1996. A global two component signal transduction system that integrates the control of photosynthesis, carbon dioxide assimilation, and nitrogen fixation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:14515-14520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jouanneau, Y., and F. R. Tabita. 1986. Independent regulation of synthesis of form I and form II ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase-oxygenase in Rhodopseudomonas sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol. 165:620-624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kay, R., and J. McPherson. 1987. Hybrid pUC vectors for addition of new restriction enzyme sites to the ends of DNA fragments. Nucleic Acids Res. 15:2778.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kusano, T., and K. Sugwara. 1993. Specific binding of Thiobacillus ferrooxidans RbcR to the intergenic sequence between the rbc operon and the rbcR gene. J. Bacteriol. 175:1019-1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kusian, B., J.-G. Yoo, R. Bednarski, and B. Bowien. 1992. The Calvin cycle enzyme pentose-5-phosphate 3-epimerase is encoded within the cfx operons of the chemoautotroph Alcaligenes eutrophus. J. Bacteriol. 174:7337-7344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London) 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lascelles, J. 1960. The formation of ribulose 1,5-diphosphate carboxylase by growing cultures of Athiorhodaceae. J. Gen. Microbiol. 23:449-510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Masuda, S., Y. Matsumoto, K. V. Nagashima, K. Shimada, K. Inoue, C. E. Bauer, and K. Matsuura. 1999. Structural and functional analyses of photosynthetic regulatory genes regA and regB from Rhodovulum sulfidophilum, Roseobacter denitrificans, and Rhodobacter capsulatus. J. Bacteriol. 181:4205-4215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meijer, W. G., A. C. Arnberg, P. Enequist, P. Terpstra, M. E. Lidstrom, and L. Dijkhuizen. 1991. Identification and organization of carbon dioxide fixation genes in Xanthobacter flavus H4-14. Mol. Gen. Genet. 225:320-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics, p. 352-355. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 41.Mosley, C. S., J. Y. Suzuki, and C. E. Bauer. 1994. Identification and molecular genetic characterization of a sensor kinase responsible for coordinately regulating light harvesting and reaction center gene expression in response to anaerobiosis. J. Bacteriol. 176:7566-7573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ormerod, J. G., K. S. Ormerod, and H. Gest. 1961. Light-dependent utilization of organic compounds and photoproduction of molecular hydrogen by the photosynthetic bacteria; relationships with nitrogen metabolism. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 94:449-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Paoli, G. C. 1997. Ph.D. thesis. The Ohio State University, Columbus.

- 44.Paoli, G. C., F. Soyer, J. M. Shively, and F. R. Tabita. 1998. Rhodobacter capsulatus genes encoding form I ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (cbbLS) and neighboring genes were acquired by a horizontal gene transfer. Microbiology 144:219-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paoli, G. C., N. Strom-Morgan, J. M. Shively, and F. R. Tabita. 1995. Expression of the cbbLcbbS and cbbM genes and distinct organization of the cbb Calvin cycle structural genes of Rhodobacter capsulatus. Arch. Microbiol. 164:396-405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paoli, G. C., P. Vichivanives, and F. R. Tabita. 1998. Physiological control and regulation of the Rhodobacter capsulatus cbb operons. J. Bacteriol. 180:4258-4269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Penfold, R. J., and J. M. Pemberton. 1992. An improved suicide vector for construction of chromosomal insertion mutations in bacteria. Gene 118:145-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pettersson, G., and U. Ryde-Pettersson. 1989. Dependence on the Calvin cycle activity on kinetic parameters for the interaction of non-equilibrium cycle enzymes with their substrates. Eur. J. Biochem. 186:683-687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pridmore, R. D. 1987. New and versatile cloning vectors with kanamycin-resistance marker. Gene 56:309-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Qian, Y., and F. R. Tabita. 1996. A global signal transduction system regulates aerobic and anaerobic CO2 fixation in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol. 178:12-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Qian, Y., and F. R. Tabita. 1998. Expression of glnB and a glnB-like gene (glnK) in a ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase-deficient mutant of Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol. 180:4644-4649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schell, M. A. 1993. Molecular biology of the LysR family of transcriptional regulators. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 47:597-626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Servaites, J. C., W.-J. Shieh, and D. R. Geiger. 1991. Regulation of photosynthetic carbon reduction cycle by ribulose bisphosphate and phosphoglyceric acid. Plant Physiol. 97:1115-1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sganga, M. W., and C. E. Bauer. 1992. Regulatory factors controlling photosynthetic reaction center and light harvesting gene expression in Rhodobacter capsulatus. Cell 68:945-954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shively, J. M., E. Davidson, and B. L. Marrs. 1984. Derepression of the synthesis of the intermediate and large forms of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase in Rhodopseudomonas capsulatus. Arch. Microbiol. 138:233-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Strecker, M., E. Sickinger, R. S. English, J. M. Shively, and E. Bock. 1994. Calvin cycle genes in Nitrobacter vulgaris T3. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 120:45-50. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tabita, F. R. 1980. Pyridine nucleotide control and subunit structure of phosphoribulokinase in photosynthetic bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 143:1275-1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tabita, F. R. 1995. The biochemistry and metabolic regulation of carbon metabolism and CO2 fixation in purple bacteria, p. 885-914. In R. E. Blankenship, M. T. Madigan, and C. E. Bauer (ed.), Anoxygenic photosynthetic bacteria. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.

- 59.Tabita, F. R. 1999. Microbial ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase: a different perspective. Photosynth. Res. 60:1-28. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Takeuchi, T., K. Nishino, and Y. Itokawa. 1984. Improved determination of transketolase activity in erythrocytes. Clin. Chem. 30:658-661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tichi, M. A., and F. R. Tabita. 2000. Maintenance and control of redox poise in Calvin-Benson-Bassham pathway deficient strains of Rhodobacter capsulatus. Arch. Microbiol. 174:322-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tichi, M. A., and F. R. Tabita. 2001. Interactive control of Rhodobacter capsulatus redox balancing systems during phototrophic metabolism. J. Bacteriol. 183:6344-6354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Towbin, H., T. Staehelin, and J. Gordon. 1979. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76:4350-4354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.van Keulan, G., L. Girbal, R. H. Van Den Bergh, L. Dijkhuizen, and W. G. Meijer. 1998. The LysR-type transcriptional regulator CbbR controlling autotrophic CO2 fixation by Xanthobacter flavus is an NADPH sensor. J. Bacteriol. 180:1411-1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Viale, A. M., H. Kobayashi, T. Akazawa, and S. Henikoff. 1991. rbcR, a gene coding for a member of the LysR family of transcriptional regulators, is located upstream of the expressed set of ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase genes in the photosynthetic bacterium Chromatium vinosum. J. Bacteriol. 173:5224-5229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vichivanives, P. 2000. Ph.D. thesis. The Ohio State University, Columbus.

- 67.Vichivanives, P., T. H. Bird, C. E. Bauer, and F. R. Tabita. 2000. Multiple regulators and their interaction in vivo and in vitro with the cbb regulons of Rhodobacter capsulatus. J. Mol. Biol. 300:1079-1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vieira, J., and J. Messing. 1982. The pUC plasmids, an m13mp7-derived system for insertion mutagenesis and sequencing with synthetic universal primers. Gene 19:259-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang, X., D. L. Falcone, and F. R. Tabita. 1993. Reductive pentose phosphate-independent CO2 fixation in Rhodobacter sphaeroides and evidence that ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase activity serves to maintain redox balance of the cell. J. Bacteriol. 175:3372-3379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Whitman, W., and F. R. Tabita. 1976. Inhibition of ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase by pyridoxal 5-phosphate. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 71:1034-1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Windhövel, U., and B. Bowien. 1991. Identification of cfxR, an activator gene of autotrophic CO2 fixation in Alcaligenes eutrophus. Mol. Microbiol. 5:2695-2705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Xu, H. H., and F. R. Tabita. 1994. Positive and negative regulation of sequences upstream of the form II cbb CO2 fixation operon of Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol. 176:7299-7308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yanisch-Perron, C., J. Vieira, and J. Messing. 1985. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene 33:103-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yen, H. C., and B. Marrs. 1976. Map of genes for carotenoid and bacteriochlorophyll biosynthesis in Rhodopseudomonas capsulatus. J. Bacteriol. 126:619-629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]