Abstract

Type III secretion systems (TTSSs) are specialized protein transport systems in gram-negative bacteria which target effector proteins into the host cell. The TTSS of the plant pathogen Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria, encoded by the hrp (hypersensitive reaction and pathogenicity) gene cluster, is essential for the interaction with the plant. One of the secreted proteins is HrpF, which is required for pathogenicity but dispensable for type III secretion of effector proteins in vitro, suggesting a role in translocation. In this study, complementation analyses of an hrpF null mutant strain using various deletion derivatives revealed the functional importance of the C-terminal hydrophobic protein region. Deletion of the N terminus abolished type III secretion of HrpF. Employing the type III effector AvrBs3 as a reporter, we show that the N terminus of HrpF contains a signal for secretion but not a functional translocation signal. Experiments with lipid bilayers revealed a lipid-binding activity of HrpF as well as HrpF-dependent pore formation. These data indicate that HrpF presumably plays a role at the bacterial-plant interface as part of a bacterial translocon which mediates effector protein delivery across the host cell membrane.

The interaction of many gram-negative plant and animal pathogenic bacteria with their hosts depends on a highly conserved type III protein secretion system (TTSS), which transports proteins without cleavage of a classical N-terminal signal peptide into the extracellular milieu as well as into the host cell (13, 25). In plant-pathogenic bacteria, the TTSS is encoded by hrp (hypersensitive response and pathogenicity) genes. hrp mutants are no longer able to multiply and cause disease in susceptible plants and to induce defense responses such as the hypersensitive reaction (HR) in resistant host and nonhost plants (1). The HR is a rapid, localized cell death of infected plant tissue which halts bacterial ingress. At least nine hrp genes, designated hrc (for hrp conserved), are conserved between plant and animal bacterial pathogens (8, 22) and probably encode the core components of the type III secretion apparatus.

Analyses of nonpolar mutants revealed that an additional set of nonconserved proteins, encoded in the hrp gene clusters, were essential for secretion and/or translocation. Among the nonconserved proteins are secreted proteins such as the subunits of the Hrp pilus, which is associated with the TTSS of plant-pathogenic bacteria (48). Hrp pili have been described for Pseudomonas syringae, Ralstonia solanacearum, and Erwinia amylovora (30, 47, 61) and probably mediate contact between the bacterial and plant cell surface. In addition, Hrp pili have been shown to be essential for type III secretion in vitro (47, 61) and were proposed to function as conduits for secreted proteins traversing the plant cell wall (29, 30). Other proteins traveling the TTSSs of plant-pathogenic bacteria include harpins and effector proteins, the latter of which have been suggested to be translocated into the plant cell (32).

Intensive studies of Yersinia outer proteins (Yops) defined the N terminus of type III-secreted proteins as an important region which directs secretion (12, 37, 56). In addition, a secretion signal in the 5′ region of the mRNA has been discussed (2, 3, 41). A translocation signal has been proposed to be located within the first 50 to 100 codons of genes encoding effector proteins of both plant and animal pathogens (41, 53, 56). Translocation of effector proteins into the host cell was first described for Yersinia spp. (19, 49, 57) and appears to be the key function of TTSSs.

Translocation is mediated by the translocon, a bacterial protein or protein complex which presumably forms channel-like structures in the host cell membrane. In plant-pathogenic bacteria, there is indirect evidence for translocation of effectors because expression of bacterial avirulence (avr) genes in the plant cell resulted in the induction of a resistance (R) gene-specific HR (11). avr genes are present in Pseudomonas and Xanthomonas spp. (69) and were originally defined based on their ability to trigger a host defense reaction, in most cases the HR. Plant defense induction depends on the specific recognition of an Avr protein by a plant expressing the corresponding R gene (31, 36). In the absence of the avr or the R gene or both, the interaction between pathogen and plant leads to disease.

Our laboratory studies type III secretion in Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria, the causal agent of bacterial spot on pepper and tomato. The TTSS is encoded by the 23-kb chromosomal hrp gene cluster (9). Expression of the six operons, hrpA to hrpF, is induced in the plant (55) and in minimal medium XVM2 (66) and is regulated by the products of the regulatory genes hrpX and hrpG. HrpG belongs to the OmpR family of two-component response regulators and activates the expression of hrpA and hrpX (68). HrpX, an AraC-type transcriptional activator, controls the expression of operons hrpB to hrpF (66) as well as the expression of avrXv3 (4) and a number of putative virulence factors (45).

The TTSS of X. campestris pv. vesicatoria secretes a number of Hrp and Avr proteins as well as Xops (Xanthomonas outer proteins) into the culture supernatant (6, 16, 41, 45, 50, 51). One of the proteins secreted by the TTSS is HrpF, an overall hydrophilic protein of 87 kDa (26). HrpF contains two N-terminal imperfect direct repeats and two C-terminal hydrophobic segments (26, 50) and shows 48% sequence identity with NolX, a type III-secreted protein from Rhizobium fredii (26, 63). Intriguingly, HrpF, which is dispensable for type III secretion in vitro, has been found to be essential for the interaction of X. campestris pv. vesicatoria with the plant. It has therefore been suggested that HrpF plays a role in type III translocation (50).

In this study, we report on the functional importance of different regions in the HrpF protein. Furthermore, we obtained indirect evidence that HrpF is not translocated into the host cell. Lipid-binding activity of secreted HrpF and the observation of HrpF-dependent pore formation in lipid bilayers support the hypothesis that HrpF acts as a translocon protein.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, growth conditions, and plasmids.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are described in Table 1. Escherichia coli cells were cultivated at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) or Super medium (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). X. campestris pv. vesicatoria strains were grown at 30°C in NYG broth (15) or in minimal medium A (5) supplemented with sucrose (10 mM) and Casamino Acids (0.3%), and Agrobacterium tumefaciens strains were grown at 30°C in yeast extract-beef (YEB) medium. Antibiotics were added to the media at following final concentrations: ampicillin, 100 μg/ml; kanamycin, 25 μg/ml; rifampin, 100 μg/ml; spectinomycin, 100 μg/ml; and tetracycline, 10 μg/ml.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristicsa | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| X. campestris pv. vesicatoria | ||

| 85-10 | Pepper race 2; wild type; Rifr | 10 |

| 85* | Derivative of 85-10 carrying hrpG* | 67 |

| 82-8 | Pepper race 1; wild type; Rifr | 40 |

| 82* | Derivative of 82-8 carrying hrpG* | 67 |

| 85-10ΔhrpF | hrpF deletion mutant of 85-10 | This study |

| 85*ΔhrpF | hrpF deletion mutant of 85* | This study |

| 85*ΔhrcV | hrcV deletion mutant of 85* | 50 |

| 82*ΔhrpF | hrpF deletion mutant of 82* | This study |

| 82*ΔhrcV | hrcV deletion mutant of 82* | 51 |

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | F−recA hsdR17(rK− mK+) φ80d lacZΔM15 | Bethesda Research Laboratories, Bethesda, Md. |

| DH5α λpir | F−recA hsdR17(rK− mK+) φ80d lacZΔM15 (λpir) | 38 |

| BL21(DE3) | F−ompT hsdS20(rB− mB−) gal | Stratagene |

| A. tumefaciens GV3101 | Cured of Ti plasmid, Rifr | 24 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBI1.4t | Binary vector, derivative of pBI121 (Clontech), p35S* with bacterial transcription terminator; Kmr | 39 |

| pBluescript (II) KS | Phagemid, pUC derivative; Apr | Stratagene |

| pDSK602 | Contains triple lacUV5 promoter; Smr | 43 |

| pGEX-2TKM | p tac GST lacIq pBR322 ori; Apr, derivative of pGEX-2TK, polylinker of pDSK604 | Stratagene (16) |

| pLAFR3 | RK2 replicon, Mob+ Tra−; contains p lac; Tcr | 58 |

| pUC119 | ColE1 replicon; Apr | 62 |

| pOK1 | sacB sacQ mobRK2 oriR6K; Smr | 27 |

| pRK2013 | ColE1 replicon, TraRK+ Mob+; Kmr | 17 |

| pDS300F | pDSK602 expressing AvrBs3, Flag tag | 60 |

| pVS300F | Binary vector pVB60 expressing AvrBs3, Flag tag | 60 |

| pDS356F | pDSK602 expressing AvrBs3 deleted in N-terminal 152 aa | O. Rossier and U. Bonas, unpublished data |

| pBI356F | Binary vector pBI1.4t carrying AvrBs3 deleted in N-terminal 152 aa | B. Szurek and U. Bonas, unpublished data |

| pOKΔhrpF | 2-kb fragment containing the hrpF flanking regions in pOK1 | This study |

| pDhrpF | pDSK602 expressing HrpF, His6 tag | This study |

| pLhrpF | pLAFR3 expressing HrpF, His6 tag | This study |

| pDhrpFΔI | pDSK602 expressing HrpF deleted in internal 460 aa, His6 tag | This study |

| pDhrpFΔN | pDSK602 expressing HrpF deleted in N-terminal 152 aa, His6 tag | This study |

| pLhrpFΔC109 | pLAFR3 expressing HrpF deleted in C-terminal 109 aa | This study |

| pLhrpFΔC249 | pLAFR3 expressing HrpF deleted in C-terminal 249 aa | This study |

| pDhrpFΔH1 | pDSK602 expressing HrpF deleted in H1, His6 tag | This study |

| pLhrpFΔH2 | pLAFR3 expressing HrpF deleted in H2, His6 tag | This study |

| pDhrpFΔH12 | pDSK602 expressing HrpF deleted in H1 and H2, His6 tag | This study |

| pBIhrpF | pBI1.4t carrying HrpF, His6 tag | This study |

| pBISPhrpF | pBI1.4t carrying HrpF containing the PR1a signal peptide, His6 tag | This study |

| pDhrpFN356, pBIhrpFN356 | pDSK602 and pBI1.4t expressing the fusion protein between the N-terminal 387 aa of HrpF and AvrBs3Δ2 | This study |

| pGhrpF, pGhrpFΔC249 | pGEX-2TKM expressing HrpF and HrpFΔC249 | This study |

| pGhrpE2 | pGEX-2TKM expressing HrpE2 | This study |

aa, amino acids; Ap, ampicillin; Km, kanamycin; Rif, rifampin; Sm, spectinomycin; Tc, tetracycline; r, resistant.

Plasmids were introduced into E. coli by electroporation and into X. campestris pv. vesicatoria and A. tumefaciens by conjugation, using pRK2013 as a helper plasmid in triparental matings (17).

Plant material and plant inoculations.

The near-isogenic pepper cultivars Early Cal Wonder (ECW), ECW-10R, and ECW-30R (40) were grown and inoculated with X. campestris pv. vesicatoria or A. tumefaciens as described previously (10, 60). Bacteria were hand-infiltrated into the intercellular spaces of fully expanded leaves at concentrations of 4 × 108 CFU/ml in 1 mM MgCl2. Reactions were scored over a period of 3 days.

Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression.

Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression assays were performed as described (60) with the following modifications: bacteria were incubated in induction medium for 4 to 6 h and infiltrated into the intercellular spaces of fully expanded leaves at concentrations of 5 × 108 CFU/ml in infiltration medium (10 mM MgCl2, 5 mM MES [morpholineethanesulfonic acid, pH 5.3], 150 μM acetosyringone).

Generation of an hrpF null mutant.

A 5.3-kb EcoRV fragment, derived from construct pBF (26), which contains the monocistronic hrpF locus, was subcloned in pUC119, giving pU5hrpF. A 2.9-kb fragment containing the hrpF coding region, 253 bp upstream, and 319 bp downstream region was deleted by ClaI digestion and religation of the plasmid. This mutation should not have a polar effect on other operons. The remaining 2-kb insert was cloned into the suicide plasmid pOK1 (27), giving pOKΔhrpF. X. campestris pv. vesicatoria strains 85-10ΔhrpF and 85*ΔhrpF were generated by introduction of pOKΔhrpF into 85-10 and 85*, respectively, as described (27).

Construction of hrpF derivatives.

For expression and purification of recombinant HrpF, plasmid pDhrpF was constructed. hrpF was amplified by PCR from genomic DNA of X. campestris pv. vesicatoria strain 85-10, using Pfu polymerase (Stratagene, Heidelberg, Germany) and primers HrpF-For (5′-TACTGAATTCGCCTCTATGTCGCTC-3′), containing an EcoRI site, and HrpF-Rev (5′-GTAAGCTTAGTGATGGTGATGGTGATGCCCGGGTCTGCGACGGATCCGGAC-3′), introducing a SmaI site, the coding sequence for six histidine residues, and a HindIII site (restriction sites are underlined in primer sequences). The PCR product was cloned by partial EcoRI and HindIII digestion into pUC119, pBluescript II KS and the broad-host-range vectors pDSK602 and pLAFR3 for expression in both E. coli and X. campestris pv. vesicatoria, giving constructs pUhrpF, pKhrpF, pDhrpF, and pLhrpF, respectively.

hrpFΔI was generated by a 1,380-bp SgrAI deletion in construct pUhrpF which leads to the deletion of amino acids 118 to 575. The resulting fragment was cloned into pDSK602, giving pDhrpFΔI. Construct pDhrpFΔN is a derivative of pDhrpF in which 456 bp encoding the N terminus of HrpF were replaced by an adaptor (5′-AATTCGCCTCTATGTCTAGAC-3′). In construct pLhrpFΔC109, a nonsense mutation was introduced by PCR, resulting in a translational stop after amino acid 697. To construct a C-terminal deletion derivative of HrpF, a 600-bp fragment at the 3′ end of hrpF in plasmid pLhrpF was deleted by digestion with SacI and SmaI, Klenow fill-in reaction, and religation. The resulting construct was designated pLhrpFΔC249.

For deletion of the C-terminal hydrophobic segments, the 600-bp SacI/HindIII fragment encoding the C terminus of HrpF was replaced by deletion derivatives. The SacI/HindIII cassette was amplified by PCR, introducing XbaI sites in the sequences flanking the hydrophobic segment-encoding region. The PCR products flanked by SacI/XbaI and XbaI/HindIII sites were fused at the XbaI site and introduced into the SacI and HindIII sites of constructs pLhrpF and pDhrpF. This resulted in deletion of amino acids 610 to 647 (pDhrpFΔH1), 647 to 692 (pLhrpFΔH2), and 610 to 692 (pDhrpFΔH12) in the corresponding gene products.

For Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression, hrpF derived from construct pKhrpF was cloned into the EcoRI and XhoI sites of pBI1.4t, giving construct pBIhrpF. For construct pBISPhrpF, a PCR product containing the signal peptide sequence of the tobacco PR1a gene (14) was fused to the hrpF open reading frame. For technical reasons, the signal peptide sequence contained 1 bp exchange, resulting in a conserved amino acid exchange at position 17 of the signal peptide. For generation of plasmids expressing the HrpF-AvrBs3 fusion protein, the 1.1-kb EcoRI fragment of construct pKhrpF encoding the N terminus of HrpF was cloned into the EcoRI site of constructs pDS356F and pBI356F, generating constructs pDhrpFN356 and pBIhrpFN356, respectively.

HrpF expression, purification, and antibody production.

For the production of a polyclonal anti-HrpF antiserum and for TRANSIL experiments, HrpF was expressed from pDhrpF and purified from E. coli BL21. Bacteria were grown in Super medium at 37°C. Expression was induced at an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.7 with IPTG (isopropylthiogalactopyranoside, 2 mM final concentration) for 2 h at 30°C. Cells were harvested, resuspended in 8 M urea-0.1 M NaH2PO4-0.01 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, and broken with a French press. After removal of cell debris, HrpF was purified from the supernatant using Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose (Qiagen). After washing with 0.1 M NaH2PO4 and 0.01 M Tris-HCl, pH 6.3, the protein was eluted with 0.1 M NaH2PO4-0.01 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.0)-150 mM histidine.

For antibody production, rabbits were immunized with the purified HrpF protein (Eurogentec, Herstal, Belgium). The serum after the third booster injection was used for immunoblot analyses.

For expression of glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins, hrpF derivatives from pUhrpF and pLhrpFΔC249 were cloned into the EcoRI and XhoI sites of the GST fusion vector pGEX-2TKM, generating pGhrpF and pGhrpFΔC249. In addition, hrpE2 was PCR amplified and cloned into the EcoRI and XhoI sites of pGEX-2TKM, giving pGhrpE2.

For the analysis of recombinant proteins in planar lipid bilayer experiments, E. coli BL21 carrying pGhrpF, pGhrpFΔC249, or pGhrpE2 was grown as described above. All GST fusion proteins were purified from inclusion bodies. Cells were broken with a French press, and inclusion bodies were pelleted by centrifugation. After extensive washing with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), the inclusion bodies were broken in 8 M urea-0.1 M NaH2PO4-0.01 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, with a French press. Insoluble debris was removed by centrifugation, and the samples were dialyzed for 16 h against PBS at 4°C. Then 200 μl of dialysate was incubated with 1 U of thrombin protease for 2 h at room temperature, and cleaved GST was removed by incubation with glutathione-Sepharose (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Freiburg, Germany) for 30 min at room temperature with shaking. After centrifugation, protein amounts in the supernatant fraction were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Coomassie staining.

Secretion experiments and protein analysis.

Bacteria were cultivated in minimal medium A overnight and resuspended to a concentration of 108 CFU/ml in minimal medium A at pH 5.4 (acidified by the addition of HCl and containing 100 μg of bovine serum albumin [BSA] per ml). After 3 h of cultivation, 0.5 ml of total cultures was pelleted by centrifugation (10,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C) and resuspended in 1/10th volume of Laemmli buffer (35). Two milliliters of culture supernatants was filtered with a low-protein-binding filter (HT Tuffryn; 0.45 μm; PALL Gelman Laboratory, Ann Arbor, Mich.), precipitated with 10% trichloroacetic acid, and resuspended in 1/100th volume of Laemmli buffer, and 10-μl aliquots of cell extracts and 15-μl aliquots of supernatants, adjusted for equal protein loading, were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose. Secretion experiments were performed at least three times.

Protein extracts from infected plant leaves were prepared by grinding leaf disks in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0)-150 mM NaCl-1 mM EDTA-1% Triton-0.1% SDS. Laemmli buffer was added, and samples containing approximately 70 μg of proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting.

Immunoblots were incubated with polyclonal antisera against HrpF, AvrBs3 (33), and the intracellular HrcN protein (50) to ensure that no cell lysis had occurred.

Horseradish peroxidase-labeled goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin antibodies (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) were used as secondary antibodies. Reactions were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

Lipid binding and planar lipid bilayer experiments.

Lipid binding experiments were performed with silica beads (TRANSIL; Nimbus Biotechnology, Leipzig, Germany) coated with POPC [1-hexadecanoyl-2-(cis-9-octadecenoyl)-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine]-POPS [1-hexadecanoyl-2-(cis-9-octadecenoyl)-sn-glycero-3-phosphoserin, 90:10]. From 1 to 3 μg of recombinant protein or 1 ml of X. campestris pv. vesicatoria culture supernatant was incubated with 2 to 5 μl of TRANSIL beads under shaking at room temperature for 1 h in 10 mM Tris (pH 7.4)-150 mM NaCl-0.5% Tween 20 (final concentration). In control samples, proteins and culture supernatants were incubated without TRANSIL beads. The beads were precipitated by centrifugation (10,000 × g for 30 s at room temperature), and the unbound material in the supernatant was collected. For secreted proteins, unbound material was precipitated on ice with 10% trichloroacetic acid and resuspended in 1/50th volume of Laemmli buffer. TRANSIL beads were washed three times with 1 ml of 10 mM Tris (pH 7.4)-1 M NaCl and resuspended in 20 μl of Laemmli buffer. Total proteins and bound and unbound material were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining and/or immunoblotting.

Planar lipid bilayers (42) were prepared from a solution of 80 parts (wt/wt) 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-glycero-3-phophatidylcholine and 20 parts (wt/wt) 1,2-dioleoyl-glycero-3-phophatidylethanolamine (Avanti Polar Lipids Inc., Alabaster, Ala.) dissolved in n-decane (15 mg/ml). Proteins were added to the cis-aqueous solution of the bilayer cuvette. Electrolyte solutions contained 100 mM KCl and 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.0. Current signals were filtered at corner frequencies between 3 and 10 kHz and recorded continuously on a digital tape recorder. As a membrane amplifier, we used a BLM-120 (Bio-Logic, Claix, France) with a low-pass linearized five-pole Tchebicheff filter.

RESULTS

Specific antiserum detects HrpF in the culture supernatant.

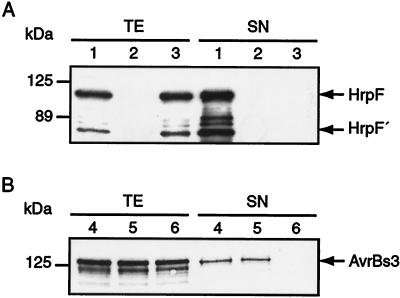

Recently, we showed type III-mediated secretion of HrpF, using a Flag-tagged version of the protein (50). For the analysis of native HrpF, a polyclonal antiserum was generated. In Western blot analyses , the antiserum reacted specifically with two proteins of approximately 100 and 70 kDa (Fig. 1A) in total extracts of X. campestris pv. vesicatoria strain 85* (85-10 carrying the hrpG* mutation, which renders hrp gene expression constitutive [67]). Since both proteins were absent in extracts of an hrpF null mutant (Fig. 1A), they were hrpF specific, indicating that the smaller protein corresponds to a processed form of HrpF, which was designated HrpF′. The processing probably occurs at the C terminus, since an anti-His6 antibody failed to detect HrpF′ in protein extracts of strain 85*(pDhrpF), which expresses a C-terminally His6-tagged HrpF protein (data not shown). In secretion experiments, HrpF and HrpF′ were detected in the supernatant of strain 85* but not of 85*ΔhrcV, a TTSS mutant (Fig. 1A). Depending on the experiment and protein amounts loaded, the antiserum also detected two additional proteins which are probably minor degradation products of HrpF. Similar results were obtained for strain 82* and derivatives (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Immunoblot analysis of wild-type and hrpF null mutant strains. (A) Detection of HrpF with a polyclonal antiserum. X. campestris pv. vesicatoria strains 85* (lane 1), 85*ΔhrpF (lane 2), and 85*ΔhrcV (lane 3), which contains a nonpolar deletion in a conserved TTSS gene, were grown in secretion medium. Equal protein amounts of total protein extracts (TE) and culture supernatants (SN) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with the HrpF-specific antiserum (see Materials and Methods). (B) The hrpF null mutant secretes AvrBs3. X. campestris pv. vesicatoria strains 82* (lane 4), 82*ΔhrpF (lane 5), and 82*ΔhrcV (lane 6) were grown in secretion medium as above. Equal protein amounts of total protein extracts (TE) and culture supernatants (SN) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with the AvrBs3-specific antiserum. The same blot was reacted with an HrcN-specific antibody to rule out that bacterial lysis had occurred (data not shown).

Complementation analyses of hrpF deletion derivatives.

Previous genetic analysis of hrpF, which is the only gene in the operon, was based on transposon insertion mutants (26, 50). For functional studies of the HrpF protein, we deleted hrpF from the genome of X. campestris pv. vesicatoria strains 85-10, 85*, and 82*. As expected, hrpF null mutants displayed a typical hrp phenotype. When inoculated into the plant, strains 85-10ΔhrpF and 85*ΔhrpF failed to grow in planta, and they were unable to cause disease symptoms in susceptible pepper ECW plants or to induce the HR in resistant ECW-10R plants, which carry the Bs1 gene.

The Bs1 resistance gene determines recognition of AvrBs1, which is expressed in strains 85-10 and 85* (40). Similar results were obtained when strain 82*ΔhrpF was inoculated into susceptible and resistant plants. X. campestris pv. vesicatoria strain 82* expresses the effector protein AvrBs3 (10) and induces the HR on ECW-30R plants, which carry the Bs3 resistance gene. As shown in Fig. 1B, AvrBs3 was detected in Western blot analysis of culture supernatants of strain 82*ΔhrpF. Thus, in contrast to the hrcV TTSS mutant, hrpF null mutants were not impaired in type III secretion.

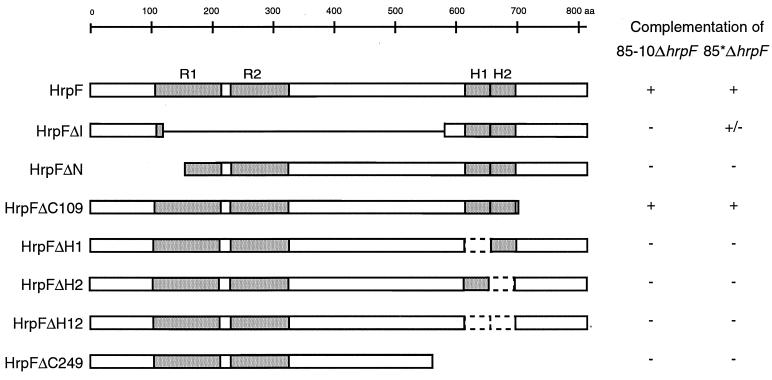

In order to identify functionally important regions in HrpF, several deletion derivatives (Fig. 2) were constructed and expressed in strains 85-10ΔhrpF and 85*ΔhrpF from broad-host-range plasmids. In plant infection tests, the mutant phenotype of both strains could be complemented by constructs expressing full-length HrpF or HrpFΔC109, but not by constructs expressing HrpFΔN and deletion derivatives lacking hydrophobic region H1 or H2 or both (Fig. 2). Interestingly, expression of hrpFΔI, which is deleted in the internal region, resulted in partial complementation of strain 85*ΔhrpF, i.e., delayed disease symptoms in pepper cultivar ECW and a partial hypersensitive reaction in ECW-10R plants (Fig. 2). In immunoblot analyses, HrpFΔI was not recognized by the HrpF-specific antiserum and could only be detected by an anti-His6 antibody in protein extracts of high-cell-density cultures (data not shown), indicating that the protein is unstable. In contrast, N- and C-terminal deletion derivatives were detected by the polyclonal HrpF-specific antibody, albeit in different amounts (Fig. 3).

FIG. 2.

Analysis of HrpF and different HrpF deletion constructs. The HrpF protein (806 amino acids) contains two repeats (R1 and R2) and two hydrophobic segments (H1 and H2). HrpF deletion derivatives were generated as described in Materials and Methods. Construct numbers refer to the numbers of deleted amino acids. Except for HrpFΔC109 and HrpFΔC249, all HrpF derivatives contain a C-terminal His6 tag (for details see Materials and Methods and Table 1). The ability of HrpF derivatives to complement an X. campestris pv. vesicatoria hrpF null mutant for disease symptom formation and HR induction is indicated on the right. Strains 85-10ΔhrpF and 85*ΔhrpF harboring the different deletion constructs were inoculated at a bacterial density of 4 × 108 CFU/ml into the intercellular spaces of leaves of pepper plants ECW-10R and ECW. Plant reactions were scored over a period of 1 to 3 days. +, disease in susceptible plants and HR in resistant plants; −, no disease symptoms, no HR; +/−, intermediate phenotype: delayed disease symptoms, partial HR.

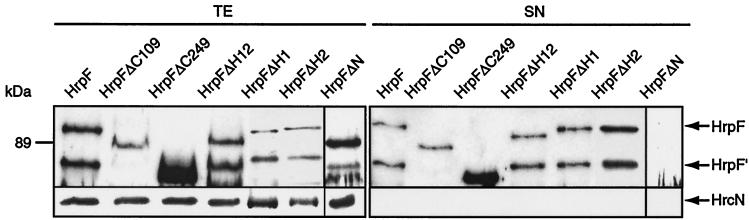

FIG. 3.

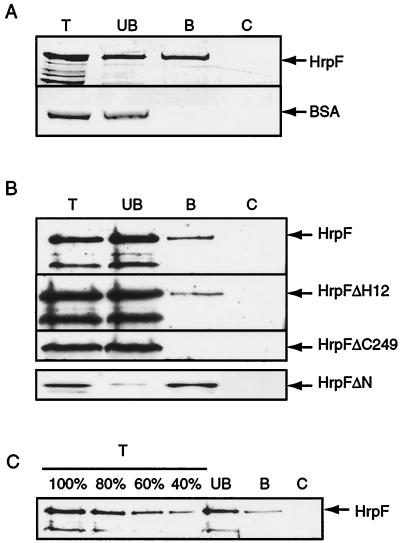

Secretion analysis of HrpF deletion constructs. X. campestris pv. vesicatoria strain 85*ΔhrpF expressing HrpF or a mutant derivative was grown in secretion medium. Equal protein amounts of total protein extracts (TE) and culture supernatants (SN) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with antibodies directed against HrpF and the intracellular HrcN protein, respectively.

The inability of hrpF deletion derivatives to complement an hrpF null mutant could be due to the lack of secretion of the corresponding gene products. However, all C-terminal HrpF deletion derivatives were secreted by the TTSS in vitro (Fig. 3). In contrast, the N-terminal deletion derivative HrpFΔN was not detected in the culture supernatant.

The N terminus of HrpF does not target the AvrBs3 protein into the host cell.

We then addressed the question of whether HrpF is not only secreted in vitro but could possibly be translocated into the plant cell, as has been observed for putative translocon proteins of animal-pathogenic bacteria (13). For this, we used an N-terminal deletion derivative (AvrBs3Δ2) of the type III effector AvrBs3 as a reporter. AvrBs3Δ2 is not secreted by X. campestris pv. vesicatoria but induces a specific hypersensitive reaction when fused with a functional translocation domain and when the gene is expressed in the resistant plant (E. Huguet, O. Rossier, and U. Bonas, unpublished data). Here, we fused the first 386 amino acids of HrpF to AvrBs3Δ2 and introduced the fusion construct (pDhrpFN356) into strain 85*.

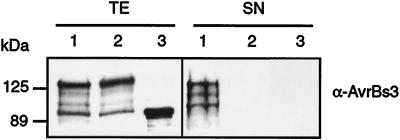

FIG. 4.

The N terminus of HrpF contains a type III secretion signal. X. campestris pv. vesicatoria strains (lane 1) 85*(pDhrpFN356), (lane 2) 85*ΔhrcV(pDhrpFN356), and (lane 3) 85*(pDS356F), expressing the HrpF-AvrBs3Δ2 fusion protein (lanes 1 and 2) and AvrBs3Δ2 (lane 3), respectively, were grown in secretion medium. Equal amounts of total protein extracts (TE) and culture supernatants (SN) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting using the AvrBs3-specific antiserum.

In total protein extracts, the HrpF-AvrBs3Δ2 protein could be detected by both the AvrBs3-specific (Fig. 4) and the HrpF-specific (data not shown) antiserum. The presence of smaller proteins which are detected by the AvrBs3-specific antibody might be due to protein instability (Fig. 4). In secretion experiments, the HrpF-AvrBs3Δ2 construct was detected in culture supernatants of strain 85* but not of the TTSS mutant 85*ΔhrcV, indicating the presence of a type III secretion signal in the N terminus of HrpF. This is in agreement with the finding that deletion of the N terminus abolished type III secretion of HrpF (Fig. 3). In plant inoculation experiments , strain 85*(pDhrpFN356) did not induce the HR in pepper genotype ECW-30R (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Plant reactions to AvrBs3 and HrpF derivativesa

| Protein expressed | Phenotype on pepper ECW-30R

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Delivery by X. campestris pv. vesicatoria 85* | Expression in planta via A. tumefaciens GV3101 | |

| AvrBs3 | HR | HR |

| AvrBs3Δ2 | + | HR |

| HrpF-AvrBs3 fusion | + | HR |

| HrpF | + | − |

Symptoms observed 3 days after inoculation at a bacterial density of 4 × 108 CFU/ml (delivery) or 5 × 108 CFU/ml (in planta). HR, hypersensitive response. +, disease symptoms; −, no phenotypic reaction.

To test whether the fusion of the HrpF-N terminus to AvrBs3Δ2 had a deleterious effect on recognition by Bs3, we expressed the fusion protein in ECW-30R, using pBIhrpFN356 and Agrobacterium-mediated gene transfer. In this case, the HrpF-AvrBs3Δ2 construct induced the HR in ECW-30R, as did full-length AvrBs3 and AvrBs3Δ2 (Table 2), demonstrating that the fusion protein is recognized by Bs3 inside the plant cell. Taken together, these data show that the HrpF-AvrBs3Δ2 fusion protein was not delivered into the plant cell when expressed in X. campestris pv. vesicatoria, although it was secreted by the TTSS in vitro.

In additional experiments, we investigated a putative function of HrpF inside the plant cell by transient expression of HrpF in planta. When A. tumefaciens strain GV3101(pBIhrpF) was inoculated into ECW-30R plants, no obvious plant reaction was observed (Table 2), although the protein was expressed, as shown by immunoblot analyses (data not shown). Furthermore, transiently expressed HrpF could not transcomplement an X. campestris pv. vesicatoria hrpF null mutant strain for disease and HR induction in ECW and ECW-10R, respectively. Since fusion of HrpF to the signal peptide sequence of the tobacco PR1a gene (14) rendered the protein unstable (data not shown), transcomplementation experiments with in planta-expressed HrpF targeted to the apoplast could not be performed.

Lipid-binding activity of HrpF.

Most putative type III translocon proteins identified so far contain predicted transmembrane regions and have been shown to associate with membranes (7, 20, 21, 23, 28, 52, 59, 64). Considering the presence of two putative transmembrane segments in HrpF as well as its proposed role during effector protein translocation, we investigated the lipid-binding activity of the protein. For this, we used a lipid bilayer system (TRANSIL beads; Nimbus Biotechnology), which consists of silica particles coated with a single phospholipid bilayer, noncovalently bound to the matrix. The bilayer contained negatively charged phospholipids which are also present in plant plasma membranes. Beads were incubated with purified recombinant HrpF protein (see Materials and Methods), and the lipid-bound and unbound material was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining or immunoblotting. To remove proteins that were associated with the lipid bilayer via ionic interactions, beads were washed under high-salt conditions (18).

As shown in Fig. 5A, recombinant HrpF associated with the lipid matrix. In contrast, BSA, used as a negative control, was only present in the supernatant. Furthermore, HrpF was not detected in the pellet when proteins were incubated without beads, ruling out that detection was due to protein precipitation. The lipid-binding activity of HrpF could be confirmed for the native protein expressed in X. campestris pv. vesicatoria. For this, TRANSIL beads were incubated with culture supernatants of strain 82*. While secreted HrpF bound to the lipid matrix, the truncated HrpF′ protein (see above) was only detected in the unbound material (Fig. 5B). The comparison of HrpF present in total supernatants and unbound and bound material indicated that approximately 40% of secreted HrpF was bound to the TRANSIL beads (Fig. 5C).

FIG. 5.

HrpF binds to lipid bilayers. (A) TRANSIL beads (2 μl) coated with POPC/POPS (90:10) were incubated with 3 μg of recombinant HrpF and BSA. After centrifugation and stringent washing of the beads, 20% of total proteins (T) and unbound (UB) and lipid-bound (B) material were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining. As a negative control (C), proteins were incubated without TRANSIL beads, and after centrifugation and stringent washing, samples corresponding to the lipid-bound material were analyzed as above. (B) X. campestris pv. vesicatoria strains 82* (top) and 82*ΔhrpF carrying plasmids pDhrpFΔH12 and pLhrpFΔC249 were grown in secretion medium. Culture supernatants were incubated with 4 μl of TRANSIL beads as above. Total culture supernatants (T) as well as unbound (UB) and lipid-bound (B) material were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with the HrpF-specific antiserum. HrpFΔN (bottom), which is not secreted in vitro, was analyzed as a recombinant protein; 0.5 μg of recombinant HrpFΔN was incubated with TRANSIL as described for A, and 20% of total protein and unbound and lipid-bound material was analyzed by immunoblotting with the anti-HrpF antibody. As a negative control, culture supernatants as well as recombinant HrpFΔN were incubated without TRANSIL (C) and analyzed as above. (C) Quantification of membrane-bound HrpF. Culture supernatants of X. campestris pv. vesicatoria strain 82* were incubated with 4 μl of TRANSIL beads and analyzed as described for B. Unbound (UB) and bound (B) material as well as samples incubated without TRANSIL (C) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with the HrpF-specific antiserum. As reference samples, 100, 80, 60, and 40% of total supernatant (T) were loaded.

In order to identify regions in HrpF which are important for membrane association, we tested HrpF deletion derivatives for their binding to TRANSIL beads. Deletion of the N terminus and of both hydrophobic segments did not affect the lipid-binding ability of HrpF (HrpFΔH12 and HrpFΔN, Fig. 5B). In contrast, HrpFΔC249, lacking a large C-terminal protein region, was not detected in the lipid-bound material (Fig. 5B). This is in agreement with the finding that HrpF′, which is similar in size to HrpFΔC249 (see Fig. 3), did not bind to the lipid matrix.

HrpF-dependent pore formation.

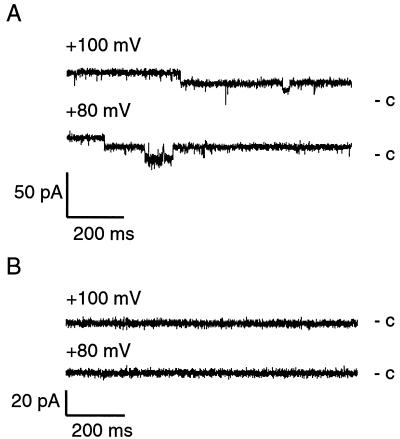

The lipid-binding activity of HrpF prompted us to investigate whether HrpF would form ion-conducting pores in a planar lipid bilayer system. When recombinant HrpF (see Materials and Methods) was added to the cis compartment of the artificial membrane, the conductivity across the bilayer increased when voltage was applied. We observed changes of open and closed channel states as well as prolonged phases of both states (Fig. 6A). HrpF-dependent pore formation did not alter significantly when different membrane potentials were applied (from −100 to +100 mV; data not shown). Surprisingly, the C-terminally truncated form of HrpF, HrpFΔC249, induced channels with similar properties (data not shown). To rule out that the channel formation was due to E. coli proteins present in the HrpF preparation, we used HrpE2 as a control, which was isolated similarly to HrpF (see Materials and Methods). HrpE2 is an 18.4-kDa acidic protein from X. campestris pv. vesicatoria and is predicted to be a soluble protein (U. Bonas, unpublished data). When applied to the artificial membrane, recombinant HrpE2 did not induce any current fluctuations (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

HrpF-dependent pore formation in planar lipid bilayers. (A) HrpF induces current fluctuations in planar lipid bilayers. Recombinant HrpF (0.5 μg/ml, purified as described in Materials and Methods) was added to the cis-aqueous solution of the lipid bilayer cuvette, and current traces were recorded. c, closed state. (B) HrpE2 shows no pore-forming properties in lipid bilayer experiments. HrpE2 was tested as a control protein. The experimental conditions were the same as in A.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated functionally important regions and membrane-binding activity of the HrpF protein from the plant pathogen X. campestris pv. vesicatoria. Our data strongly support the hypothesis that HrpF plays a role in protein translocation. So far, HrpF is the only known putative type III translocon protein of a plant-pathogenic bacterium.

Analyses of hrpF null mutant strains revealed that HrpF is essential for pathogenicity but dispensable for type III-mediated protein secretion in vitro. This is in agreement with results based on the analyses of hrpF transposon insertion mutants (50). An interesting feature of the HrpF protein is the presence of two imperfect repeats in the N terminus. Deletion studies showed that the presence of the second repeat is sufficient for protein function (26). Here, complementation experiments demonstrated that the region C-terminal to the hydrophobic segments is also not required. In contrast, the hydrophobic segments are essential for HrpF function. Interestingly, the internal protein region appears to be less important, since the hrpF null mutant could be partially complemented by HrpFΔI. However, partial complementation was only observed in an hrpG* background, which leads to a more efficient expression of the TTSS. Lack of complementation of the hrpF null mutant by HrpFΔN is probably due to the inability of the bacteria to secrete this derivative. This indicates that HrpF is targeted for type III secretion by its N terminus and that secretion is essential for HrpF function.

The hypothesis of a secretion signal in the N terminus is supported by the finding that a fusion protein between the N-terminal 386 amino acids of HrpF and AvrBs3Δ2 is secreted in vitro. AvrBs3, like other type III effectors, is probably translocated into the plant cell, because in planta expression of the gene triggers the HR (60). However, bacteria expressing the HrpF-AvrBs3 fusion protein did not induce the AvrBs3-specific HR, indicating that the N terminus of HrpF does not contain a translocation signal. HrpF might have to be delivered from outside of the plant cell, a hypothesis which is supported by the inability of in planta-expressed HrpF to transcomplement the phenotype of an hrpF null mutant.

Taken together, these data support the hypothesis that HrpF acts at the bacterial-plant interface as a translocon protein. So far, putative components of the predicted type III translocon have only been identified in animal-pathogenic bacteria, where they presumably form a transmembrane channel. In Yersinia, Shigella, and enteropathogenic E. coli spp., the existence of a translocation channel has been proposed based on their ability to induce the lysis of erythrocytes and macrophages (7, 20, 44, 65). Furthermore, fusion of planar lipid bilayers with liposomes which had been incubated with secreted Yops induced current fluxes, indicating the formation of transmembrane pores (59). Lytic activity of Yersinia requires at least three proteins, YopB, YopD, and LcrV (20, 23, 44). Recent demonstration of a pore-forming activity of purified LcrV suggested that LcrV is the channel size-determining component of the type III translocation channel, which is stabilized by YopB and YopD (23).

The putative translocon proteins from animal-pathogenic bacteria are not conserved among different species, but some of them have structural similarities, such as putative transmembrane regions. The presence of two predicted transmembrane segments in HrpF (26) prompted us to investigate its lipid-binding activity. A tendency of HrpF to bind to membranes had already been indicated by fractionation studies (26). From 30 to 40% of a Flag-tagged HrpF protein was localized to the inner membrane of X. campestris pv. vesicatoria under nonsecreting conditions. Here, using the TRANSIL system which provides a highly mobile artificial lipid bilayer, mimicking diffusion and other surface properties of natural lipid bilayers (54), we could demonstrate lipid-binding activity of recombinant as well as native secreted HrpF. The fact that high-salt washes did not remove HrpF from the lipid matrix is interpreted as membrane insertion rather than membrane binding.

Lipid-binding in vitro using the TRANSIL system was independent of the presence of the hydrophobic segments in HrpF, indicating that HrpF interacts with lipids via nonhydrophobic regions, presumably in the C terminus. This was surprising because the hydrophobic segments have been speculated to act as a transmembrane anchor. So far, except for IpaC from Shigella flexneri (46), it has not been investigated whether predicted transmembrane regions are essential for lipid binding in other putative translocon proteins. Interestingly, using the TM-PRED program (http://www.ch.embnet.org/software/TM-PRED_form.html), no transmembrane regions are predicted for LcrV from Yersinia spp. and PcrV from Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which have both been demonstrated to form transmembrane channels (23).

It is tempting to speculate that these proteins span the membrane via β-barrel structures. β-Barrel structures are typical of many bacterial outer membrane proteins (34) and are also found in several bacterial toxins which assemble to oligomeric channels in the eukaryotic host cell membrane. The presence of β-barrels in putative translocon proteins of the TTSS has not been investigated yet.

To address the question of whether HrpF forms transmembrane channels, we used a planar lipid bilayer system. Indeed, recombinant HrpF induced altered current fluxes, indicative of pore formation. Unexpectedly, this was also observed for an HrpF derivative lacking the C terminus, which was shown to be essential for lipid binding in the TRANSIL system. We speculate that this derivative has a residual in vitro lipid-binding activity which can only be detected by the very sensitive planar lipid bilayer assays. Similar findings have been reported for LcrV from Yersinia enterocolitica: deletion of a C-terminal protein region, which was demonstrated to be essential for Yop delivery as well as for induction of erythrocyte lysis, did not alter its pore-forming activity (23).

It has to be kept in mind that artificial lipid bilayers have smooth surfaces without any exposed structures, like lipid-bound polysaccharides or membrane proteins, which could influence the insertion of proteins in natural membranes. Here, we show that the C terminus of HrpF from X. campestris pv. vesicatoria, which is dispensable for pore formation in vitro, is essential for its biological function. It is conceivable that this region is required for efficient protein translocation in vivo, stabilizing the pore or interacting with accessory proteins. Whether HrpF alone is sufficient to form the translocation channel in vivo remains to be investigated.

In animal-pathogenic bacteria, the observation of protein-protein interactions between putative translocon components suggests that the translocon is a heterogenic protein complex (23). Future experimental approaches will therefore focus on the identification of HrpF's interaction partners.

Acknowledgments

We thank Angelika Landgraf for technical assistance, Laurent Noël for helpful suggestions, and O. Rossier for construction of pDS356F.

This work was supported by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft to U.B. (BO 790/7-1) and a fellowship from the Verband der Chemischen Industrie to D.B.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alfano, J. R., and A. Collmer. 1997. The type III (Hrp) secretion pathway of plant-pathogenic bacteria: trafficking harpins, Avr proteins, and death. J. Bacteriol. 179:5655-5662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson, D. M., D. E. Fouts, A. Collmer, and O. Schneewind. 1999. Reciprocal secretion of proteins by the bacterial type III machines of plant and animal pathogens suggests universal recognition of mRNA targeting signals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:12839-12843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson, D. M., and O. Schneewind. 1997. A mRNA signal for the type III secretion of Yop proteins by Yersinia enterocolitica. Science 278:1140-1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Astua-Monge, G., G. V. Minsavage, R. E. Stall, M. J. Davis, U. Bonas, and J. B. Jones. 2000. Resistance of tomato and pepper to T3 strains of Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria is specified by a plant-inducible avirulence gene. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 13:911-921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl (ed.). 1996. Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 6.Ballvora, A., M. Pierre, G. van den Ackerveken, S. Schornack, O. Rossier, M. Ganal, T. Lahaye, and U. Bonas. 2001. Genetic mapping and functional analysis of the tomato Bs4 locus governing recognition of the Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria AvrBs4 protein. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 14:629-638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blocker, A., P. Gounon, E. Larquet, K. Niebuhr, V. Cabiaux, C. Parsot, and P. Sansonetti. 1999. The tripartite type III secretion of Shigella flexneri inserts IpaB and IpaC into host membranes. J. Cell Biol. 147:683-693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bogdanove, A., S. V. Beer, U. Bonas, C. A. Boucher, A. Collmer, D. L. Coplin, G. R. Cornelis, H.-C. Huang, S. W. Hutcheson, N. J. Panopoulos, and F. Van Gijsegem. 1996. Unified nomenclature for broadly conserved hrp genes of phytopathogenic bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 20:681-683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonas, U., R. Schulte, S. Fenselau, G. V. Minsavage, B. J. Staskawicz, and R. E. Stall. 1991. Isolation of a gene-cluster from Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria that determines pathogenicity and the hypersensitive response on pepper and tomato. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 4:81-88. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonas, U., R. E. Stall, and B. Staskawicz. 1989. Genetic and structural characterization of the avirulence gene avrBs3 from Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria. Mol. Gen. Genet. 218:127-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonas, U., and G. Van den Ackerveken. 1999. Gene-for-gene interactions: bacterial avirulence proteins specify plant disease resistance. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2:94-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng, L. W., D. M. Anderson, and O. Schneewind. 1997. Two independent type III secretion mechanisms for YopE in Yersinia enterocolitica. Mol. Microbiol. 24:757-765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cornelis, G. R., and F. Van Gijsegem. 2000. Assembly and function of type III secretory systems. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54:735-774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cornelissen, B. J., J. Horowitz, J. A. van Kan, R. B. Goldberg, and J. F. Bol. 1987. Structure of tobacco genes encoding pathogenesis-related proteins from the PR-1 group. Nucleic Acids Res. 15:6799-6811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daniels, M. J., C. E. Barber, P. C. Turner, M. K. Sawczyc, R. J. W. Byrde, and A. H. Fielding. 1984. Cloning of genes involved in pathogenicity of Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris using the broad host range cosmid pLAFR1. EMBO J. 3:3323-3328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Escolar, L., G. Van den Ackerveken, S. Pieplow, O. Rossier, and U. Bonas. 2001. Type III secretion and in planta recognition of the Xanthomonas avirulence proteins AvrBs1 and AvrBsT. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2:287-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Figurski, D., and D. R. Helinski. 1979. Replication of an origin-containing derivative of plasmid RK2 dependent on a plasmid function provided in trans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76:1648-1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Finberg, K. E., T. R. Muth, S. P. Young, J. B. Maken, S. M. Heitritter, A. N. Binns, and L. M. Banta. 1995. Interactions of VirB9, -10, and -11 with the membrane fraction of Agrobacterium tumefaciens: solubility studies provide evidence for tight associations. J. Bacteriol. 177:4881-4889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Håkansson, S., E. E. Galyov, R. Rosqvist, and H. Wolf-Watz. 1996. The Yersinia YpkA Ser/Thr kinase is translocated and subsequently targeted to the inner surface of the HeLa cell plasma membrane. Mol. Microbiol. 20:593-603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Håkansson, S., K. Schesser, C. Persson, E. E. Galyov, R. Rosqvist, F. Homble, and H. Wolf-Watz. 1996. The YopB protein of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis is essential for the translocation of Yop effector proteins across the target cell plasma membrane and displays a contact-dependent membrane disrupting activity. EMBO J. 15:5812-5823. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hayward, R. D., E. J. McGhie, and V. Koronakis. 2000. Membrane fusion activity of purified SipB, a Salmonella surface protein essential for mammalian cell invasion. Mol. Microbiol. 37:727-739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.He, S. Y. 1998. Type III protein secretion systems in plant and animal pathogenic bacteria. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 36:363-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holmström, A., J. Olsson, P. Cherepanov, E. Maier, R. Nordfelth, J. Pettersson, R. Benz, H. Wolf-Watz, and A. Forsberg. 2001. LcrV is a channel size-determining component of the Yop effector translocon of Yersinia. Mol. Microbiol. 39:620-632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holsters, M., B. Silva, F. Van Vliet, C. Genetello, M. De Block, P. Dhaese, A. Depicker, D. Inze, G. Engler, R. Villarroel, et al. 1980. The functional organization of the nopaline A. tumefaciens plasmid pTiC58. Plasmid 3:212-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hueck, C. J. 1998. Type III protein secretion systems in bacterial pathogens of animals and plants. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:379-433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huguet, E., and U. Bonas. 1997. hrpF of Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria encodes an 87-kDa protein with homology to NolX of Rhizobium fredii. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 10:488-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huguet, E., K. Hahn, K. Wengelnik, and U. Bonas. 1998. hpaA mutants of Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria are affected in pathogenicity but retain the ability to induce host-specific hypersensitive reaction. Mol. Microbiol. 29:1379-1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ide, T., S. Laarmann, L. Greune, H. Schillers, H. Oberleithner, and M. A. Schmidt. 2001. Characterization of translocation pores inserted into plasma membranes by type III-secreted Esp proteins of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Cell. Microbiol. 3:669-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jin, Q., and S. Y. He. 2001. Role of the Hrp pilus in type III protein secretion in Pseudomonas syringae. Science 294:2556-2558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jin, Q., W. Hu, I. Brown, G. McGhee, P. Hart, A. L. Jones, and S. Y. He. 2001. Visualization of secreted Hrp and Avr proteins along the Hrp pilus during type III secretion in Erwinia amylovora and Pseudomonas syringae. Mol. Microbiol. 40:1129-1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keen, N. T. 1990. Gene-for-gene complementarity in plant-pathogen interactions. Annu. Rev. Genet. 24:447-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kjemtrup, S., Z. Nimchuk, and J. L. Dangl. 2000. Effector proteins of phytopathogenic bacteria: bifunctional signals in virulence and host recognition. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 3:73-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Knoop, V., B. Staskawicz, and U. Bonas. 1991. Expression of the avirulence gene avrBs3 from Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria is not under the control of hrp genes and is independent of plant factors. J. Bacteriol. 173:7142-7150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koebnik, R., K. P. Locher, and P. Van Gelder. 2000. Structure and function of bacterial outer membrane proteins: barrels in a nutshell. Mol. Microbiol. 37:239-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lahaye, T., and U. Bonas. 2001. Molecular secrets of bacterial type III effector proteins. Trends Plant Sci. 6:479-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lloyd, S. A., M. Norman, R. Rosqvist, and H. Wolf-Watz. 2001. Yersinia YopE is targeted for type III secretion by N-terminal, not mRNA, signals. Mol. Microbiol. 39:520-532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ménard, R., P. J. Sansonetti, and C. Parsot. 1993. Nonpolar mutagenesis of the ipa genes defines IpaB, IpaC, and IpaD as effectors of Shigella flexneri entry into epithelial cells. J. Bacteriol. 175:5899-5906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mindrinos, M., F. Katagiri, G. L. Yu, and F. M. Ausubel. 1994. The A. thaliana disease resistance gene RPS2 encodes a protein containing a nucleotide-binding site and leucine-rich repeats. Cell 78:1089-1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Minsavage, G. V., D. Dahlbeck, M. C. Whalen, B. Kearny, U. Bonas, B. J. Staskawicz, and R. E. Stall. 1990. Gene-for-gene relationships specifying disease resistance in Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria-pepper interactions. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 3:41-47. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mudgett, M. B., O. Chesnokova, D. Dahlbeck, E. T. Clark, O. Rossier, U. Bonas, and B. J. Staskawicz. 2000. Molecular signals required for type III secretion and translocation of the Xanthomonas campestris AvrBs2 protein to pepper plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:13324-13329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mueller, P., D. O. Rudin, H. Tien, and W. C. Wescott. 1962. Reconstitution of a cell membrane structure in vitro and its transformation into an excitable system. Nature 194:979-980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murillo, J., H. Shen, D. Gerhold, A. Sharma, D. A. Cooksey, and N. T. Keen. 1994. Characterization of pPT23B, the plasmid involved in syringolide production by Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato PT23. Plasmid 31:275-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Neyt, C., and G. R. Cornelis. 1999. Insertion of a Yop translocation pore into the macrophage plasma membrane by Yersinia enterocolitica: requirement for translocators YopB and YopD, but not LcrG. Mol. Microbiol. 33:971-981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Noël, L., F. Thieme, D. Nennstiel, and U. Bonas. 2001. cDNA-AFLP analysis unravels a genome-wide hrpG-regulon in the plant pathogen Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria. Mol. Microbiol. 41:1271-1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Picking, W. L., L. Coye, J. C. Osiecki, A. Barnoski Serfis, E. Schaper, and W. D. Picking. 2001. Identification of functional regions within invasion plasmid antigen C (IpaC) of Shigella flexneri. Mol. Microbiol. 39:100-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roine, E., W. S. Wei, J. Yuan, E. L. Nurmiaho-Lassila, N. Kalkkinen, M. Romantschuk, and S. Y. He. 1997. Hrp pilus: A hrp-dependent bacterial surface appendage produced by Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:3459-3464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Romantschuk, M., E. Roine, and S. Taira. 2001. Hrp pilus-reaching through the plant cell wall. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 107:153-160. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rosqvist, R., K. E. Magnusson, and H. Wolf-Watz. 1994. Target cell contact triggers expression and polarized transfer of Yersinia YopE cytotoxin into mammalian cells. EMBO J. 1390:964-972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rossier, O., G. Van den Ackerveken, and U. Bonas. 2000. HrpB2 and HrpF from Xanthomonas are type III-secreted proteins and essential for pathogenicity and recognition by the host plant. Mol. Microbiol. 38:828-838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rossier, O., K. Wengelnik, K. Hahn, and U. Bonas. 1999. The Xanthomonas Hrp type III system secretes proteins from plant and mammalian pathogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:9368-9373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Scherer, C. A., E. Cooper, and S. I. Miller. 2000. The Salmonella type III secretion translocon protein SspC is inserted into the epithelial cell plasma membrane upon infection. Mol. Microbiol. 37:1133-1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schesser, K., E. Frithz-Lindsten, and H. Wolf-Watz. 1996. Delineation and mutational analysis of the Yersinia pseudotuberculosis YopE domains which mediate translocation across bacterial and eukaryotic cellular membranes. J. Bacteriol. 178:7227-7233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schmitz, A. A., E. Schleiff, C. Rohring, A. Loidl-Stahlhofen, and G. Vergeres. 1999. Interactions of myristoylated alanine-rich C kinase substrate (MARCKS)-related protein with a novel solid-supported lipid membrane system (TRANSIL). Anal. Biochem. 268:343-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schulte, R., and U. Bonas. 1992. Expression of the Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria hrp gene cluster, which determines pathogenicity and hypersensitivity on pepper and tomato, is plant inducible. J. Bacteriol. 174:815-823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sory, M. P., A. Boland, I. Lambermont, and G. R. Cornelis. 1995. Identification of the YopE and YopH domains required for secretion and internalization into the cytosol of macrophages, using the cyaA gene fusion approach. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:11988-11991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sory, M. P., and G. R. Cornelis. 1994. Translocation of a hybrid YopE-adenylate cyclase from Yersinia enterocolitica into HeLa cells. Mol. Microbiol. 14:583-594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Staskawicz, B. J., D. Dahlbeck, N. Keen, and C. Napoli. 1987. Molecular characterization of cloned avirulence genes from race0 and race1 of Pseudomonas syringae pv. glycinea. J. Bacteriol. 169:5789-5794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tardy, F., F. Homble, C. Neyt, R. Wattiez, G. R. Cornelis, J. M. Ruysschaert, and V. Cabiaux. 1999. Yersinia enterocolitica type III secretion-translocation system: channel formation by secreted Yops. EMBO J. 18:6793-6799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Van den Ackerveken, G., E. Marois, and U. Bonas. 1996. Recognition of the bacterial avirulence protein AvrBs3 occurs inside the host plant cell. Cell 87:1307-1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Van Gijsegem, F., J. Vasse, J. C. Camus, M. Marenda, and C. Boucher. 2000. Ralstonia solanacearum produces Hrp-dependent pili that are required for PopA secretion but not for attachment of bacteria to plant cells. Mol. Microbiol. 36:249-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vieira, J., and J. Messing. 1987. Production of single-stranded plasmid DNA. Methods Enzymol. 153:3-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Viprey, V., A. Del Greco, W. Golinowski, W. J. Broughton, and X. Perret. 1998. Symbiotic implications of type III protein secretion machinery in Rhizobium. Mol. Microbiol. 28:1381-1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wachter, C., C. Beinke, M. Mattes, and M. A. Schmidt. 1999. Insertion of EspD into epithelial target cell membranes by infecting enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 31:1695-1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Warawa, J., B. B. Finlay, and B. Kenny. 1999. Type III secretion-dependent hemolytic activity of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 67:5538-5540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wengelnik, K., and U. Bonas. 1996. HrpXv, an AraC-type regulator, activates expression of five of the six loci in the hrp cluster of Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria. J. Bacteriol. 178:3462-3469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wengelnik, K., O. Rossier, and U. Bonas. 1999. Mutations in the regulatory gene hrpG of Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria result in constitutive expression of all hrp genes. J. Bacteriol. 181:6828-6831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wengelnik, K., G. Van den Ackerveken, and U. Bonas. 1996. HrpG, a key hrp regulatory protein of Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria is homologous to two-component response regulators. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 9:704-712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.White, F. F., B. Yang, and L. B. Johnson. 2000. Prospects for understanding avirulence gene function. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 3:291-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]