Abstract

Expression of the P3 promoter of the Bacillus subtilis ureABC operon is activated during nitrogen-limited growth by PucR, the transcriptional regulator of the purine-degradative genes. Addition of allantoic acid, a purine-degradative intermediate, to nitrogen-limited cells stimulated transcription of ure P3 twofold. Since urea is produced during purine degradation in B. subtilis, regulation of ureABC expression by PucR allows purines to be completely degraded to ammonia. The nitrogen transcription factor TnrA was found to indirectly regulate ure P3 expression by activating pucR expression. The two consensus GlnR/TnrA binding sites located in the ure P3 promoter region were shown to be required for negative regulation by GlnR. Mutational analysis indicates that a cooperative interaction occurs between GlnR dimers bound at these two sites. B. subtilis is the first example where urease expression is both nitrogen regulated and coordinately regulated with the enzymes involved in purine transport and degradation.

Urease degrades urea to two molecules of ammonia and carbon dioxide (14). In Bacillus subtilis, urease is encoded by the ureABC operon (7). Urease expression in B. subtilis is elevated during nitrogen-limited growth and is not induced by urea (1, 25). Although the ureABC operon has three promoters, this operon is primarily transcribed by the σA-dependent ure P3 promoter in exponentially growing cells (25). Expression of the ure P3 promoter has been shown to be regulated in response to nutrient availability by three transcriptional factors, GlnR, TnrA, and CodY (25). CodY activity is controlled by the levels of GTP, which serve as an indicator of the overall nutritional state of the cell (17). GlnR and TnrA are responsible for increased gene expression during nitrogen-limited growth in B. subtilis (10, 22, 26). TnrA and GlnR belong to the MerR family of DNA-binding proteins. The amino acid sequences of the N-terminal DNA-binding domain of TnrA and GlnR are nearly identical, and both proteins bind to sites with the same conserved DNA sequence, 5′-TGTNAN7TNACA-3′ (GlnR/TnrA site) (5, 22, 23, 26). GlnR and TnrA have little sequence similarity in their C-terminal signal transduction domains and are active under different nutritional conditions. GlnR represses gene expression during growth with excess nitrogen, while TnrA both activates and represses gene expression during nitrogen limitation. Although the mechanism regulating GlnR activity is not understood, the activity of TnrA is controlled by a reversible interaction with glutamine synthetase (28).

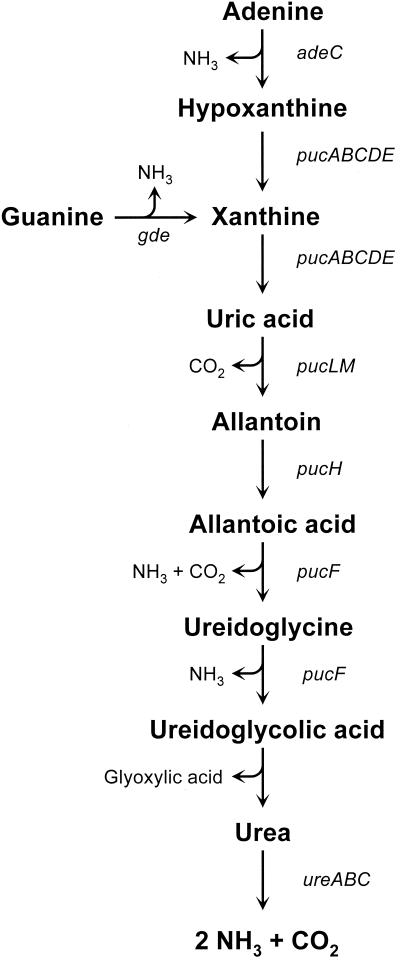

B. subtilis can utilize purines as a source of nitrogen (Fig. 1) (7, 15, 16, 20). The PucR transcription factor is a pathway-specific regulator of the genes belonging to the purine catabolic (puc) regulon (3, 24). PucR functions as both a transcriptional activator and repressor. The regulation of gene expression by PucR is enhanced by growth in medium containing intermediates in purine catabolism, such as uric acid, allantoin, or allantoic acid (3, 24). Mutational analysis of several puc promoters has identified a cis-acting sequence, 5′-WWWCNTTGGTTAA-3′ (PucR box), which is required for PucR-dependent gene regulation (3). Interestingly, the expression of pucR is activated by TnrA (3).

FIG. 1.

Purine-degradative pathway in B. subtilis. The purine-degradative enzymes are as follows: adenine deaminase (adeC) (16), guanine deaminase (gde) (15), xanthine dehydrogenase (pucABCDE) (24), uricase (pucLM) (24), allantoinase (pucH) (24), allantoate amidohydrolase (pucF) (24), and urease (ureABC) (7).

PucR activates ure P3 expression during nitrogen-limited growth.

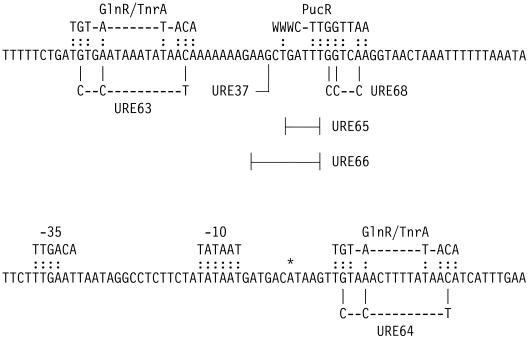

Several observations suggested that the ureABC operon may be a member of the PucR regulon. First of all, urea is produced by the degradation of purines in B. subtilis (Fig. 1) (7, 24). Secondly, a nucleotide sequence that is highly similar to the PucR box consensus sequence was found to be located upstream of the ure P3 promoter (Fig. 2). In addition, microarray experiments revealed that high-level ureABC expression during nitrogen-limited growth was dependent upon PucR (H. Jarmer and H. H. Saxild, unpublished observations).

FIG. 2.

Nucleotide sequence of the ure P3 promoter. The transcriptional start site is indicated by an asterisk. The consensus sequences for the −10 and −35 regions of σA-dependent promoters, GlnR/TnrA sites, and PucR box are indicated above the nucleotide sequence. The nucleotide substitutions in URE63, URE68, and URE64 and the nucleotide deletions in URE65 and URE66 are indicated below the nucleotide sequence. The upstream endpoint of ure DNA in URE37 is indicated.

The role of PucR in regulating the expression of the ure P3 promoter was examined in cells containing a ure P3-lacZ transcriptional fusion (URE28). The strains used in this study are given in Table 1. Under nitrogen-limiting growth conditions, allantoic acid was found to increase expression of the URE28 fusion twofold (Table 2). For unknown reasons, no induction was observed with allantoin (data not shown). β-Galactosidase levels from the URE28 fusion were 20-fold lower in a pucR mutant than in wild-type cells during nitrogen limitation, and allantoic acid induction of ure P3 expression did not occur in the pucR mutant (Table 2). Finally, mutational inactivation of the PucR box in the ure P3 promoter (URE68 [Fig. 2]) reduced ure P3 expression in nitrogen-limited cells and abolished induction by allantoic acid (Table 2). Taken together, these results indicate that ure P3 expression is activated by PucR.

TABLE 1.

B. subtliis strains used in this study

TABLE 2.

β-Galactosidase expression of various ure P3 promoter lacZ fusions in wild-type and mutant strains

| Fusiona | Fusion genotype | Strain genotypeb | β-Galactosidase sp act (U/mg of protein) in cells grown withc:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glutamine | Glutamate | Glutamate + allantoic acid | |||

| URE28 | Wild type | Wild type | 0.1 | 110 | 240 |

| Wild type | glnR | 4.8 | 100 | NDd | |

| Wild type | tnrA | 0.1 | 11 | ND | |

| Wild type | pucR | 0.1 | 5.6 | 6.7 | |

| Wild type | glnR codY | 16 | 160 | 230 | |

| Wild type | glnR codY tnrA | 12 | 21 | 60 | |

| Wild type | pucR glnR codY | 11 | 7.9 | 8.4 | |

| URE63 | Mutant upstream GlnR site | Wild type | 2.1 | 130 | 220 |

| URE64 | Mutant downstream GlnR site | Wild type | 5.9 | 270 | 350 |

| URE68 | Mutant PucR site | Wild type | 0.1 | 6.4 | 7.7 |

The URE28 transcriptional lacZ fusion, which contains ure P3 DNA between −196 and + 118, has been described previously (25). Derivatives of URE28 containing the mutations and internal deletions shown in Fig. 2 were constructed by oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis. The URE37 fusion contains an AluI-EcoRV DNA fragment subclone of the ure P3 promoter.

All strains are 168 derivatives containing the indicated ure P3-lacZ fusion integrated as a single copy at the amyE locus. Strains were constructed by transforming mutant and wild-type cells to neomycin resistance with plasmid DNA. Transformants resulting from double-crossover events at the amyE locus were identified by screening for loss of amylase activity on tryptose blood agar-starch plates (12). The mutant alleles used in this study are shown in Table 1.

Cultures were grown in minimal medium containing glucose as the carbon source and the indicated nitrogen sources (2). Allantoic acid was added to a final concentration of 0.48 mM. β-Galactosidase was assayed as previously described (2). Values are the average of 2 to 15 determinations, which did not vary by more than 20%.

ND, not determined.

TnrA indirectly regulates ure P3 expression.

During growth with the nitrogen-limiting source glutamate, expression of the ure P3 promoter is 10-fold lower in the tnrA mutant than in wild-type cells (Table 2) (25). This result indicates that TnrA is required for the activation of ure P3 promoter expression under these conditions. Two consensus GlnR/TnrA sites are located in the ure P3 promoter region. One site is centered 91 bp upstream of the ure P3 transcriptional start site, while the other site is centered 15 bp downstream of the transcriptional start site (Fig. 2). The position of the upstream site is unusual in that the TnrA binding sites of other TnrA-activated promoters are centered 48 to 51 bp upstream of the transcriptional start site (27). To see whether the upstream GlnR/TnrA site is required for TnrA regulation of the ure P3 promoter, this site was mutationally inactivated (Fig. 2). This mutant ure P3-lacZ fusion, URE63, is expressed at levels similar to those seen with the wild-type URE28 fusion in glutamate-grown cells (Table 2). This result indicates that the upstream GlnR/TnrA site is not required for high-level ure P3 expression during nitrogen-limited growth and suggests that TnrA indirectly regulates ure P3 expression. Indeed, when expression of the URE28 lacZ fusion was examined in a pucR glnR codY mutant, no regulation was observed (Table 2).

It has been shown previously that during nitrogen-limited growth the expression of pucR increases 27-fold in a wild-type strain but only fourfold in a tnrA mutant (3). As a result, nitrogen-limited tnrA mutants contain low but significant levels of PucR compared to wild-type cells. Indeed, expression of the URE28 fusion was activated 10-fold in a glnR codY mutant but only twofold in a glnR codY tnrA mutant during nitrogen-limited growth (Table 2). Taken together, these observations indicate that the defect in ure P3 expression observed in the tnrA mutant during nitrogen-limited growth results from its inability to synthesize wild-type levels of PucR.

Both GlnR/TnrA sites are required for GlnR-dependent regulation.

GlnR represses gene expression during growth on excess nitrogen sources such as glutamine (10). During growth of wild-type cells with excess nitrogen, ure P3-lacZ fusions containing a mutation in either the upstream GlnR/TnrA site (URE63) or the downstream GlnR/TnrA site (URE64) were expressed at higher levels than was the wild-type URE28 fusion (Table 2). These data suggest that both GlnR/TnrA sites are required for nitrogen source-dependent regulation of ure P3 expression by GlnR.

To specifically analyze GlnR-dependent regulation, expression of the ure P3-lacZ fusions was examined in pucR tnrA codY cells. In this genetic background, expression of the URE28 fusion, which contains the two wild-type GlnR/TnrA sites, was regulated 160-fold by GlnR (Table 3). No regulation of the URE64 fusion was observed (Table 3), indicating that the downstream GlnR/TnrA site is absolutely required for GlnR-dependent repression. Two ure P3-lacZ fusions that lack a functional upstream GlnR/TnrA site were only weakly regulated by GlnR. The URE63 fusion, which contains a 3-bp mutation in the upstream GlnR/TnrA site, was regulated fourfold by GlnR (Table 3). In the URE37 fusion, the upstream GlnR/TnrA site was deleted (Fig. 2). Expression of the URE37 fusion was regulated eightfold by GlnR (Table 3). These results indicate that both GlnR/TnrA sites in the ure P3 promoter are involved in regulation by GlnR and that they most likely function as binding sites for GlnR. The simplest model to explain these results is that GlnR binding to the downstream GlnR site inhibits the initiation of transcription at the ure P3 promoter and that the binding of GlnR to the downstream site can be strengthened by a cooperative interaction with GlnR bound to the upstream GlnR site.

TABLE 3.

GlnR-dependent regulation of β-galactosidase expression from wild-type and mutant ure P3-lacZ fusionsa

| Fusionb | Fusion genotype | β-Galactosidase sp act (U/mg of protein) in cells grown withc:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Glutamine | Glutamate | ||

| URE28 | Wild type | 0.1 | 16 |

| URE37 | Deletion of upstream GlnR site | 1.4 | 11 |

| URE63 | Mutant upstream GlnR site | 4.3 | 18 |

| URE64 | Mutant downstream GlnR site | 12 | 14 |

| URE65 | 5-bp deletion | 1.4 | 11 |

| URE66 | 10-bp deletion | 2.2 | 86 |

If a cooperative DNA-looping interaction occurs between GlnR bound at the upstream and downstream GlnR sites in the ure P3 promoter region, these two GlnR sites must be appropriately spaced on the same side of the DNA helix. By analogy to other systems (21), GlnR-dependent regulation of ure P3 should be reduced when the distance between the upstream and downstream GlnR sites is changed by half-integral turns of DNA (5 bp). Moreover, deletion of a whole integral turn of DNA (10 bp) should restore the correct phasing between these two sites and increase regulation by GlnR. In the URE65 fusion, 5 bp of DNA was deleted between the upstream and downstream GlnR sites (Fig. 2). Expression of the URE65 fusion was regulated only eightfold by GlnR (Table 3). In contrast, expression of the URE66 fusion, which contains a full-integral-turn 10-bp deletion between the two GlnR sites (Fig. 2), was regulated over 40-fold by GlnR (Table 3). The 10-bp deletion in the URE66 fusion moves a sequence containing 7 consecutive A's closer to the ure P3 promoter. The higher levels of expression seen with the URE66 fusion may result from this sequence acting as an upstream promoter element that enhances transcription from the ure P3 promoter (19).

The regulation of the glnRA operon by GlnR has previously been shown to involve cooperative interactions. GlnR represses glnRA transcription by binding to two adjacent operators that lie upstream and overlap the −35 region of the glnRA promoter (11, 23). Since GlnR binds simultaneously to both operators with in vitro and in vivo DNA footprinting experiments (5, 11), a cooperative interaction appears to occur between the GlnR dimers bound at these sites. This conclusion is supported by the observations that GlnR-dependent regulation of glnRA expression is completely relieved by either deletion of the upstream operator or insertion of a 5-bp DNA fragment between the two operators (23).

Although our analysis of the ure P3 promoter indicates that a cooperative interaction occurs between the forms of GlnR bound at the two GlnR sites in the ure P3 promoter region, GlnR still weakly regulates ure P3-lacZ fusions containing only the downstream GlnR site. It is possible that GlnR binds with sufficient affinity to the downstream GlnR site in the ure P3 promoter to weakly regulate gene expression. Alternatively, this low level of regulation may result from GlnR binding to both the downstream GlnR site and a yet unrecognized sequence with poor homology to a GlnR site in the ure P3 promoter region.

Significance of ure P3 regulation by PucR.

Urease is widely distributed in bacteria (14). The expression of urease is controlled by diverse regulatory mechanisms, suggesting that this enzyme has multiple physiological roles in bacteria. For example, urease expression in Streptococcus salivarius is induced by growth at acidic pH (6). Since the degradation of urea to carbon dioxide and two molecules of ammonia produces a net increase in pH, high levels of urease can facilitate alkalization and bacterial survival in acidic environments. Because ammonia produced during urea catabolism can provide nitrogen for cell growth, the expression of urease in some bacteria is regulated in response to nitrogen availability. During nitrogen-limited growth, urease expression is activated by the Ntr system in Klebsiella aerogenes (18).

B. subtilis urease is a novel example of an urease enzyme whose expression is controlled by both a global nitrogen transcription factor and a pathway-specific regulator that responds to purine availability. Purine degradation occurs during nitrogen-limited growth in B. subtilis (3, 15, 16, 24). Since urea is produced by the final step in purine catabolism (Fig. 1), activation of ureABC expression by PucR ensures that purines are completely degraded to ammonia under these growth conditions. Substrates for purine catabolism are likely obtained from the degradation of DNA present in the environment because B. subtilis synthesizes both extracellular nucleases and efficient transport systems for DNA degradation products (8). It is also noteworthy that the expression of competence genes is induced during nitrogen-limited growth in B. subtilis (13). This observation raises the possibility that single DNA strands that are not incorporated into the chromosome during transformation may be degraded to provide nutrients for continued cell growth. Interestingly, the ability to utilize extracellular DNA as an energy source during stationary phase in Escherichia coli cells has been shown to be dependent upon homologs of proteins involved in transformation in Haemophilus influenzae and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (9).

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Zalieckas for technical assistance.

This research was supported by Public Health Service research grant GM51127 from the National Institutes of Health to S.H.F. and by grants from the Danish National Research Foundation and the Saxild Family Foundation to H.J. and H.H.S., respectively.

REFERENCES

- 1.Atkinson, M. R., and S. H. Fisher. 1991. Identification of genes and gene products whose expression is activated during nitrogen-limited growth in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 173:23-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atkinson, M. R., L. V. Wray, Jr., and S. H. Fisher. 1990. Regulation of histidine and proline degradation enzymes by amino acid availability in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 172:4758-4765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beier, L., P. Nygaard, H. Jarmer, and H. H. Saxild. 2002. Transcriptional analysis of the Bacillus subtilis PucR regulon and identification of a cis-acting sequence required for PucR-regulated expression of genes involved in purine catabolism. J. Bacteriol. 184:3232-3241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biaudet, V., F. Samson, C. Anagnostopoulos, S. D. Ehrlich, and P. Bessieres. 1996. Computerized genetic map of Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology 142:2669-2729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown, S. W., and A. L. Sonenshein. 1996. Autogenous regulation of the Bacillus subtilis glnRA operon. J. Bacteriol. 178:2450-2454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen, Y.-Y. M., C. A. Weaver, and R. A. Burne. 2000. Dual functions of Streptococcus salivarius urease. J. Bacteriol. 182:4667-4669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cruz-Ramos, H., P. Glaser, L. V. Wray, Jr., and S. H. Fisher. 1997. The Bacillus subtilis ureABC operon. J. Bacteriol. 179:3371-3373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dubnau, D., and C. M. Lovett, Jr. 2002. Transformation and recombination, p. 453-471. In A. L. Sonenshein, J. A. Hoch, and R. Losick (ed.), Bacillus subtilis and its closest relatives. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 9.Finkel, S. E., and R. Kolter. 2001. DNA as a nutrient: novel role for bacterial competence gene homologs. J. Bacteriol. 183:6288-6293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher, S. H. 1999. Regulation of nitrogen metabolism in Bacillus subtilis: vive la différence. Mol. Microbiol. 32:223-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gutowski, J. C., and H. J. Schreier. 1992. Interaction of the Bacillus subtilis glnRA repressor with operator and promoter sequences in vivo. J. Bacteriol. 174:671-681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henkin, T. M., F. J. Grundy, W. L. Nicholson, and G. H. Chambliss. 1991. Catabolite repression of α-amylase expression in Bacillus subtilis involves a trans-acting gene product homologous to the Escherichia coli lacI and galR repressors. Mol. Microbiol. 5:575-584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jarmer, H., R. Berka, S. Knudsen, and H. H. Saxild. 2002. Transcriptome analysis documents induced competence of Bacillus subtilis during nitrogen limiting conditions. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 206:197-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mobley, H. L. T., M. D. Island, and R. P. Hausinger. 1995. Molecular biology of microbial ureases. Microbiol. Rev. 59:451-480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nygaard, P., S. M. Bested, K. A. K. Andersen, and H. H. Saxild. 2000. Bacillus subtilis guanine deaminase is encoded by the yknA gene and is induced during growth with purines as the nitrogen source. Microbiology 146:3061-3069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nygaard, P., P. Duckert, and H. H. Saxild. 1996. Role of adenine deaminase in purine salavage and nitrogen metabolism and characterization of the ade gene in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 178:846-853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ratnayake-Lecamwasam, M., P. Serror, K.-W. Wong, and A. L. Sonenshein. 2001. Bacillus subtilis CodY represses early-stationary-phase genes by sensing GTP levels. Genes Dev. 15:1093-1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reitzer, L. J. 1996. Sources of nitrogen and their utilization, p. 380-390. In F. C. Neidhardt, R. Curtiss III, J. L. Ingraham, E. C. C. Lin, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, W. S. Reznikoff, M. Riley, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger, (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 19.Ross, W., K. K. Gosink, J. Salomon, K. Igarashi, C. Zhou, A. Ishihama, K. Severinov, and R. L. Gourse. 1991. A third recognition element in bacterial promoters: DNA binding by the α subunit of RNA polymerase. Science 262:1407-1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rouf, M. A., and R. F. Lomprey. 1968. Degradation of uric acid by certain aerobic bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 96:617-622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schleif, R. 1992. DNA looping. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 61:199-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schreier, H. J., S. W. Brown, K. D. Hirschi, J. F. Nomellini, and A. L. Sonenshein. 1989. Regulation of Bacillus subtilis glutamine synthetase gene expression by the product of the glnR gene. J. Mol. Biol. 210:51-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schreier, H. J., C. A. Rostkowski, J. F. Nomellini, and K. D. Hirschi. 1991. Identification of DNA sequences involved in regulating Bacillus subtilis glnRA expression by the nitrogen source. J. Mol. Biol. 220:241-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schultz, A. C., P. Nygaard, P., and H. H. Saxild. 2001. Functional analysis of 14 genes that constitute the purine catabolic pathway in Bacillus subtilis and evidence for a novel regulon controlled by the PucR transcription factor. J. Bacteriol. 183:3293-3302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wray, L. V., Jr., A. E. Ferson, and S. H. Fisher. 1997. Expression of the Bacillus subtilis ureABC operon is controlled by multiple regulatory factors including CodY, GlnR, TnrA, and Spo0H. J. Bacteriol. 179:5494-5501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wray, L. V., Jr., A. E. Ferson, K. Rohrer, and S. H. Fisher. 1996. TnrA, a transcription factor required for global nitrogen regulation in Bacillus subtilis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:8841-8845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wray, L. V., Jr., J. M. Zalieckas, A. E. Ferson, and S. H. Fisher. 1998. Mutational analysis of the TnrA-binding sites in the Bacillus subtilis nrgAB and gabP promoter regions. J. Bacteriol. 180:2943-2949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wray, L. V., Jr., J. M. Zalieckas, and S. H. Fisher. 2001. Bacillus subtilis glutamine synthetase controls gene expression through a protein-protein interaction with transcription factor TnrA. Cell 107:427-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]