Abstract

In Rhodobacter sphaeroides, the two cbb operons encoding duplicated Calvin-Benson Bassham (CBB) CO2 fixation reductive pentose phosphate cycle structural genes are differentially controlled. In attempts to define the molecular basis for the differential regulation, the effects of mutations in genes encoding a subunit of Cbb3 cytochrome oxidase, ccoP, and a global response regulator, prrA (regA), were characterized with respect to CO2 fixation (cbb) gene expression by using translational lac fusions to the R. sphaeroides cbbI and cbbII promoters. Inactivation of the ccoP gene resulted in derepression of both promoters during chemoheterotophic growth, where cbb expression is normally repressed; expression was also enhanced over normal levels during phototrophic growth. The prrA mutation effected reduced expression of cbbI and cbbII promoters during chemoheterotrophic growth, whereas intermediate levels of expression were observed in a double ccoP prrA mutant. PrrA and ccoP1 prrA strains cannot grow phototrophically, so it is impossible to examine cbb expression in these backgrounds under this growth mode. In this study, however, we found that PrrA mutants of R. sphaeroides were capable of chemoautotrophic growth, allowing, for the first time, an opportunity to directly examine the requirement of PrrA for cbb gene expression in vivo under growth conditions where the CBB cycle and CO2 fixation are required. Expression from the cbbII promoter was severely reduced in the PrrA mutants during chemoautotrophic growth, whereas cbbI expression was either unaffected or enhanced. Mutations in ccoQ had no effect on expression from either promoter. These observations suggest that the Prr signal transduction pathway is not always directly linked to Cbb3 cytochrome oxidase activity, at least with respect to cbb gene expression. In addition, lac fusions containing various lengths of the cbbI promoter demonstrated distinct sequences involved in positive regulation during photoautotrophic versus chemoautotrophic growth, suggesting that different regulatory proteins may be involved. In Rhodobacter capsulatus, ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase-oxygenase (RubisCO) expression was not affected by cco mutations during photoheterotrophic growth, suggesting that differences exist in signal transduction pathways regulating cbb genes in the related organisms.

Rhodobacter sphaeroides and other nonsulfur purple bacteria exhibit unparalleled metabolic versatility. In part, a functional Calvin-Benson-Bassham (CBB) reductive pentose phosphate cycle is crucial for metabolic versatility. Depending on the growth mode, the CBB pathway plays different roles (28). During photoheterotrophic growth, the CBB pathway functions to enable CO2 to serve as an electron sink for excess reducing power generated during oxidation of organic carbon substrates. Alternate electron acceptors, such as dimethyl sulfoxide, however, may replace CO2 (32). In the absence of alternate electron acceptors provided under these growth conditions, the demand for the CBB cycle is directly related to the oxidation state of the carbon source provided (28). Two other growth modes, photoautotrophy and chemoautotrophy, require the CBB cycle to supply fixed carbon to the cell. Under these growth conditions, the demand for CO2 fixation is much higher than that during photoheterotrophic growth, simply because CO2 is the sole carbon source. Because of the different roles played by the CBB cycle, a regulatory network that links CO2 fixation not only to the demand for carbon but also to the oxidation-reduction (or redox) status of the cell has evolved in R. sphaeroides (8, 11, 24). In recent years, a variety of genes that appear to be involved in sensing redox have been identified in this organism (4, 5, 21). In particular, a two-component histidine kinase-response regulator pair, encoded by the prrBA (regBA) genes, has been shown to activate transcription of genes involved in such diverse processes as photosystem biosynthesis, carbon dioxide assimilation, and nitrogen fixation and metabolism (11, 17, 24, 25), and in the related organism Rhodobacter capsulatus, the regBA system has also been shown to repress genes involved in hydrogen oxidation and dimethyl sulfoxide reduction (3, 13). Although the signal recognized by the prr system has remained elusive, recent studies with R. sphaeroides suggest the involvement of electron transport through a Cbb3 cytochrome oxidase in transmitting an inhibitory signal to the sensor kinase, PrrB, resulting in decreased levels of phosphorylated PrrA required for activation of photosynthesis genes (Fig. 1) (19). This proposal is based on the observation that photosystem promoters, normally regulated by the response regulator PrrA, become deregulated in cytochrome oxidase mutants. Under aerobic growth conditions, genes that are normally not expressed, or are transcribed at low levels, are turned on; these genes become overexpressed under anaerobic growth conditions. Double mutants impaired in prrA and ccoP exhibit the nonpigmented phenotype of the single prrA mutant (19). This apparent dominance of the prrA mutation suggested that both prrA and ccoP were part of the same signal transduction pathway. Finally, mutations in ccoQ, a gene transcribed with cytochrome oxidase structural genes, do not affect cytochrome oxidase activity per se, but ccoQ mutants do elicit the same deregulated expression pattern for the pigment genes as observed in ccoP mutants, where the Cbb3 cytochrome oxidase is inactivated (20). Recent evidence suggests that the product of the ccoQ gene may play a role in stabilizing CcoP (22).

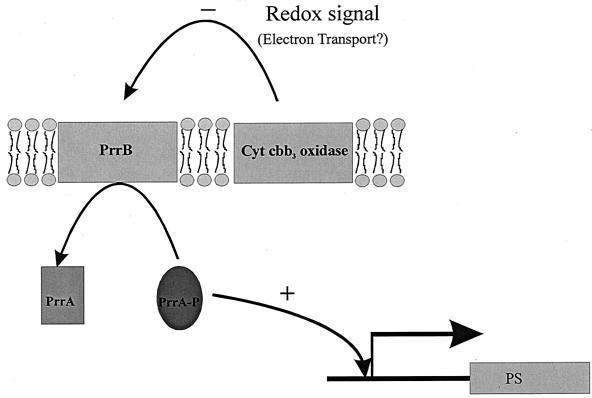

FIG. 1.

Model of photosystem gene regulation by PrrA in R. sphaeroides. An inhibitory signal generated by Cbb3 cytochrome oxidase in response to the redox status of the cell is suggested to be transmitted to PrrB, thereby inhibiting phosphorylation of PrrA. In the absence of the inhibitory signal, transcription of photosystem (PS) genes is observed. (Data are from reference 19.)

In R. sphaeroides duplicated CBB cycle genes are encoded within the cbbI and cbbII operons, which exhibit distinct growth-dependent gene expression patterns (7). In general, expression of genes within the cbbII operon is more responsive to the redox status of the cell, whereas the cbbI genes are transcribed in response to the demand for carbon (7, 12, 29). A LysR-type transcriptional regulator, CbbR, and the PrrBA two-component system activate both operons (1, 2, 8, 24). Additional, as-yet-unidentified, regulatory factors may account for differential expression of the cbb operons.

Because of the proposed involvement of the Cbb3 oxidase in the signal transduction pathway modulating phosphorylation of PrrA in R. sphaeroides, it was of obvious interest to examine the expression of cbb genes in cco mutant backgrounds. The inability of prrA strains of R. sphaeroides to grow phototrophically due to the absence of photosynthetic pigments has necessitated the use of alternate conditions of derepression to examine the role of PrrA in gene expression. The effect of PrrA on expression of photosynthesis genes has been examined in cells grown in the dark under lowered oxygen tension, a growth mode in which photosynthesis is not required but that nonetheless causes gratuitous induction of pigment synthesis. For cbb expression, CO2 starvation causes induction of cbb genes. In both cases, no induction was observed in the prrA mutant (2). prrB mutants grow phototrophically, presumably because PrrA is phosphorylated by alternative sensor kinases (10). In addition to decreased pigment production, cbb gene expression is down regulated in a prrB background (24).

In this investigation, a prrA mutant of R. sphaeroides was found to be capable of dark chemoautotrophic growth in a H2-CO2-O2 atmosphere (23). Under this growth condition cbb gene expression is required, allowing the organism to use CO2 as the sole carbon source, thus affording the opportunity to study the effects of prrA on cbb transcription in growing cells. Further, expression of both cbb operons was deregulated in a ccoP mutant background, similar to the case for genes involved in photosystem biosynthesis under chemoheterotrophic and phototrophic growth conditions. However, drastically different patterns of cbbI and cbbII promoter activity were found in prrA and prrA ccoP mutant backgrounds during chemoautotrophic growth, suggesting that the proposed link between ccoP and prrA in signal transduction may not be absolute.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

R. sphaeroides and R. capsulatus strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. For growth experiments, Ormerod's minimal salts medium supplemented with 0.4% dl-malate was used for aerobic chemoheterotrophic growth in flasks at 30°C with rigorous shaking. For anaerobic photoheterotrophic growth, completely filled screw-cap tubes were placed in front of incandescent light bulbs as described previously (12). Photoautotrophic cultures were bubbled continuously with 1.5% CO2-98.5% H2, and chemoautotrophically grown cultures were bubbled with 5% CO2-45% H2-50% air, in Ormerod's minimal salts medium (9). Adaptation of all R. sphaeroides strains, except strain CcoQ, to chemoautotrophic competence (CAC) was accomplished as previously described (23). For genetic exchange experiments, R. sphaeroides transconjugants were selected on peptone-yeast extract medium (33) supplemented with the appropriate antibiotic. Escherichia coli JM109 (34) and HB101(pRK2013) (6) were grown in Luria broth at 37°C with shaking (26). Conjugal transfer of plasmids pVKC1 and pVKCII from E. coli to R. sphaeroides strains was accomplished by triparental mating as previously described (33), using helper plasmid pRK2013 (6). Antibiotics were added to media when appropriate at the following concentrations: for E. coli, kanamycin at 25 μg/ml and tetracycline at 25 μg/ml; for R. sphaeroides, kanamycin at 25 μg/ml, tetracycline at 5 μg/ml, trimethoprim at 20 μg/ml, and spectinomycin at 20 μg/ml.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Bacterial strain or plasmid | Genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| R. sphaeroidesa | ||

| HR | Wild type; Smr | 33 |

| PrrA | HRCAC, prrA::SalI spc cartridge of pHP45 inserted into XhoI site of prrA | Y. Qian and F. R. Tabita, unpublished results |

| HRΩ | HRCAC prrB::ΩSp | 24 |

| 2.4.1 | Wild type | |

| CcoP1 | 2.4.1 ccoP::ΩTp | 18 |

| CcoP1PrrA | 2.4.1 ccoP::ΩTprrA::ΩSpc, | 19 |

| CcoQΔ | 2.4.1, in-frame deletion in ccoQ | 22 |

| R. capsulatus | ||

| MT1131 | Wild type, crtD121 Rifr | 27 |

| GK32 | MT1131 ccoNO::Km cox | 14 |

| MG1 | MT1131 ccoP::Km cox | 14 |

| M4 | MT1131 ΔccoN | 27 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pVKC1 | pVK102 Tcr Kmr, cbbI::lacZYA | 2 |

| pVKCII | pVK102 Tcr Kmr, cbbII::lacZYA | This study |

All R. sphaeroides strains except CCOQΔ are CAC.

Preparation of cell extracts and enzyme assays.

Rhodobacter cultures were grown to mid- to late exponential phase, and 20-ml samples were collected, washed once with TEM (25 mM Tris-Cl, 1 mM EDTA, and 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol), and frozen at −70°C until use. Cell extracts were prepared by sonication followed by centrifugation in an Eppendorf centrifuge at 4°C for 10 min. ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase-oxygenase (RubisCO) activity was measured in the supernatant fraction as described previously (7). The protein concentration was determined by a modified Lowry protocol (16) or with the Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, Calif.) protein assay dye-binding reagent. β-Galactosidase assays were based on continuous measurement of ο-nitrophenol produced, using the extinction coefficient for ο-nitrophenol (1). Absorbance spectra of cell extracts were determined at room temperature by using a Cary 100 spectrophotometer.

Western immunoblot procedure.

Proteins resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (15) were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Immobilon-P; Millipore, Bedford, Mass.) according to directions supplied by the manufacturer, using a Bio-Rad Transblot semidry transfer cell. Washes and incubations with antibodies were carried out as described previously (30), using antibodies directed against either the form I or form II RubisCO from R. sphaeroides. Immunoblots were developed with the Attophos detection reagent according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, England) and visualized with a Storm 840 imaging system (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, Calif.).

RESULTS

RubisCO activity in CcoP and PrrA/RegA strains.

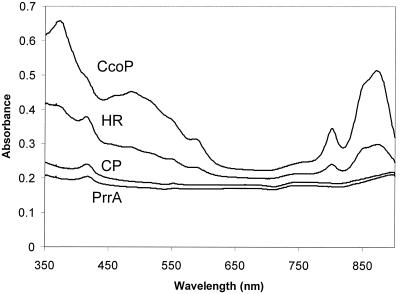

Mutations in ccoP that inactivate the high-affinity Cbb3 cytochrome oxidase of R. sphaeroides show significant levels of pigment production during aerobic chemoheterotrophic growth. Enhanced pigment synthesis is also observed in ccoP strains during anaerobic phototrophic growth, whereas mutants in which prrA is impaired are completely unable to synthesize pigments and grow phototrophically (35). The observed derepression of pigment gene expression in the ccoP strains appears to be mediated through PrrA, because double ccoP prrA mutants exhibit the nonpigmented phenotype of strain PrrA (19). Since expression of the cbb genes, which encode enzymes of the CBB CO2 fixation pathway, have also been shown to be under control of PrrA/RegA, it was of interest to determine the role of the Cbb3 cytochrome oxidase in repression of these genes during growth in the presence of oxygen. Accordingly, R. sphaeroides HR and 2.4.1 (wild type), CcoP1 (ccoP) (18), PrrA (prrA) (Y. Qian and F. R. Tabita, unpublished results), and CcoP1PrrA (a double mutant containing mutations in both ccoP and prrA) (19) were cultured under different growth conditions; extracts were prepared and assayed for RubisCO activity as a measure of overall cbb gene expression. During chemoheterotrophic growth in air in the presence of a fixed carbon source such as malate, RubisCO activity was, as expected, found at very low levels in wild-type strains (Table 2). However, the ccoP mutant strain exhibited a 15-fold increase in RubisCO activity over the wild type (Table 2). The prrA strain exhibited low RubisCO activity, comparable to that observed in the wild-type strain, whereas the ccoP prrA double mutant exhibited activity intermediate between those measured in the wild type and the ccoP mutant. In view of the enhanced levels of RubisCO activity in the ccoP strain during aerobic chemoheterotrophic growth, it was of interest to examine the effect of this mutation on cbb expression under aerobic chemoautotrophic growth conditions, that is, growth in the presence of O2, where CO2 serves as the sole carbon source in the absence of organic carbon. Under aerobic chemoautotrophic growth conditions the cbb genes are much more highly expressed than during aerobic chemoheterotrophic growth (23). R. sphaeroides does not normally grow under chemoautotrophic conditions unless it is adapted via a gain-of-function mutation (23). We have found that all R. sphaeroides strains may be adapted to these growth conditions (G. C. Paoli, J. L. Gibson, and F. R. Tabita, unpublished observations). Such CAC strains are capable of using CO2 as the sole carbon source and O2 as the terminal electron acceptor. A previously prepared prrA mutant of strain HRCAC (Qian and Tabita, unpublished results) was found to be capable of chemoautotrophic growth with 5% CO2, albeit with a prolonged lag and a generation time that was greater than that of the wild-type CAC strain. Because a mutation in the prrA/regA gene does not affect chemoautotrophic growth like it does phototrophic growth, this prrA strain afforded, for the first time, the ability to directly assess the effect of the prrA mutation on cbb gene expression in growing cells. In addition, R. sphaeroides strain HRΩ, which contains a mutation in the prrB gene (24), was also found to grow chemoautotrophically, albeit after about a 7-day lag period, which was not noted previously. Wild-type strains HR and 2.4.1 grew with a distinct pink coloration during chemoautotrophic growth; this coloration was markedly enhanced in the ccoP mutant, whereas the prrA and ccoP prrA strains were completely nonpigmented. These pigmentation differences for chemoautotrophically grown wild-type and mutant strains were reflected by the absorption spectra obtained (Fig. 2). Similar to phototrophically grown cells, the ccoP mutant expressed higher levels of pigments than the wild-type strain, while no pigment production was noted for the prrA and prrA ccoP strains (Fig. 2).

TABLE 2.

RubisCO activities in R. sphaeroides strains

| Strain | RubisCO activitya under the following condition:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemoheterotrophy (malate-air) | Photoheterotrophy (malate-argon) | Photoautotrophy (1.5% CO2-98% H2) | Chemoautotrophy (5% CO2-45% H2-50% air) | |

| 2.4.1 (wild type) | 2 ± 1 | 46 ± 5 | 288 ± 10 | 32 ± 2 |

| HR (wild type) | 2 ± 1 | 55 ± 15 | 278 ± 6 | 33 ± 2 |

| CACΩ | NDb | 17 ± 3 | 65 ± 38 | ND |

| PrrA | 3 ± 1 | ND | ND | 32 ± 11 |

| CcoP1 | 31 ± 5 | 261 ± 17 | 339 ± 13 | 142 ± 16 |

| CcoP1PrrA | 11 ± 2 | ND | ND | 138 ± 55 |

| CcoQ | 1 ± 0.3 | 35 ± 8 | 289 ± 67 | ND |

Activities are expressed as nanomoles of CO2 fixed per minute per milligram of protein. Numbers represent the averages and standard deviations from multiple assays of two or three independent cultures.

ND, not determined.

FIG. 2.

Absorption spectra of wild-type (HR) and mutant (CcoP1 [CcoP], PrrA, and CcoPPrrA [CP]) strains of R. sphaeroides. Spectra were obtained from cell extracts of cultures that were grown chemoautotrophically. Extracts were normalized to a protein concentration of 500 μg/ml.

In conjunction with the photosynthetic pigment content, RubisCO activity levels for the mutant and wild-type CAC strains were assessed when cells were cultured under chemoautotrophic growth conditions (Table 2). As noted for chemoheterotrophic cultures, both wild-type strains and the prrA strain exhibited similar levels of RubisCO during chemoautotrophic growth, suggesting that PrrA does not activate or repress cbb expression in the presence of oxygen. By contrast, in the ccoP and ccoP prrA mutant strains, RubisCO activity levels were fourfold greater than that in the wild-type strain. Based on RubisCO activity in chemoheterotrophic and chemoautotrophic cultures, activation of cbb genes in the presence of oxygen in the ccoP mutant appeared to be independent of PrrA. The effect of the mutation in ccoP on anaerobic expression of the cbb genes was also examined. RubisCO activity was measured in cells grown photoheterotrophically on malate and photoautotrophically in a 1.5% CO2-98.5% H2 atmosphere, growth conditions that in the wild-type strain elicit intermediate and high levels of RubisCO, respectively. The strains that contain a mutation in prrA were not included, since they do not grow phototrophically due to the inability to synthesize the photosynthetic apparatus. Therefore, in these experiments, strain CACΩ (containing a mutation in prrB/regB) was substituted, since this strain is able to grow despite reduced synthesis of pigments (25). In photoheterotrophically grown cells, the ccoP strain exhibited nearly a sevenfold increase in RubisCO activity over that of the wild-type strain, comparable to the highly induced levels of RubisCO observed during photoautotrophic growth of the wild-type strain (Table 2). By contrast, RubisCO activity levels were nearly identical in the wild-type strain and the ccoP mutant when these strains were grown photoautotrophically. As reported previously (24), RubisCO activity in the prrB mutant strain was severely diminished under photoautotrophic conditions, to levels comparable to that observed during photoheterotrophic growth (Table 2).

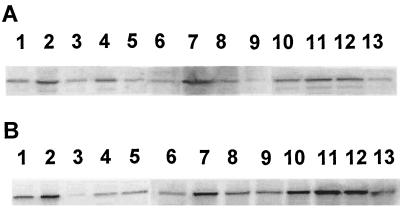

Western immunoblot analysis of form I and form II RubisCO synthesis.

R. sphaeroides synthesizes two distinct RubisCO enzymes, encoded by genes within separate cbb operons. RubisCO activity measurements do not distinguish between the two enzymes; however, advantage may be taken of the fact that the form I and form II RubisCO enzymes from R. sphaeroides are immunologically distinct. Therefore, Western immunoblot analysis was used to qualitatively assess the extent to which each operon was affected by the mutations. In chemoautotrophically grown cells (Fig. 3, lanes 1 to 5), the ccoP mutation resulted in increased accumulation of both forms of RubisCO (Fig. 3, lanes 2), in accordance with the higher level of RubisCO measured in this strain. In spite of unchanged RubisCO activity, an obvious decrease in the form II RubisCO was observed in the prrA mutant (Fig. 3B, lane 3); form I RubisCO accumulation was only slightly affected by the prrA mutation (Fig. 3A, lane 3). Under chemoautotrophic growth conditions, the pattern of form I and form II RubisCO accumulation exhibited by the ccoP prrA strain was distinct from that exhibited by the single mutants. The level of form I RubisCO protein in the ccoP prrA double mutant was similar to that observed in the ccoP strain (Fig. 3A, lane 4), whereas the amount of form II RubisCO protein observed in all prrA strains was clearly diminished compared to that in the ccoP strain (Fig. 3B, lanes 3 and 4). The amount of both form I and form II RubisCO was found to increase as a result of the ccoP mutation in cells grown photoheterotrophically (Fig. 3, lanes 6 and 7). In extracts derived from photoautotrophically grown cells, the level of form I and form II RubisCO protein increased only slightly in the ccoP strain compared to the wild-type strain (Fig. 3, lanes 11). The mutation in prrB, as reported previously (24) and shown here for comparison, resulted in decreased accumulation of both form I and form II RubisCO in cells cultured photoheterotrophically and photoautotrophically (Fig. 3, lanes 9 and 13).

FIG. 3.

Western immunoblot analysis of form I and form II RubisCO in R. sphaeroides cco and prr mutants grown under different conditions. Antisera to form I (A) and form II (B) RubisCO were reacted against immunoblots containing cell extracts of R. sphaeroides strain HR (lanes 1, 6, and 10), CcoP1 (lanes 2, 7, and 11), CcoQΔ (lanes 8 and 12), HRΩ (lanes 5, 9, and 13), PrrA (lanes 3), and CcoP1PrrA (lanes 4). Cells were cultured under three growth conditions: lanes 1 to 5, chemoautotrophic growth; lanes 6 to 9, photoheterotrophic growth; and lanes 10 to 13, photoautotrophic growth. For photoheterotrophic and photoautotrophic growth samples, 35 μg of protein was loaded onto sodium dodecyl sulfate gels, and for chemoautotrophic growth samples, 50 μg of protein was applied to gels.

RubisCO activity in the CcoQ mutant.

It was previously shown that inactivation of the ccoN, ccoO, or ccoP gene results in complete loss of Cbb3 cytochrome oxidase activity and a concomitant derepression of the expression of the photosystem biosynthesis genes in R. sphaeroides (18, 20). By contrast, although deregulation of pigment gene transcription in the presence of oxygen is observed in a ccoQ mutant, cytochrome oxidase activity is unchanged (20). Interestingly, inactivation of ccoQ did not affect the level of RubisCO activity in cultures of R. sphaeroides grown chemoheterotrophically on malate (Table 2), suggesting that cytochrome oxidase activity is required for the repressive effect under aerobic conditions. In addition, RubisCO activity was unaltered in the ccoQ mutant in cells grown phototrophically (Table 2). Analysis of cell extracts by Western immunoblot analysis also revealed little difference in form I and form II RubisCO synthesis between phototrophically grown ccoQ and wild-type strains (Fig. 3, lanes 8 and 12).

R. sphaeroides cbbI and cbbII reporter-promoter assays.

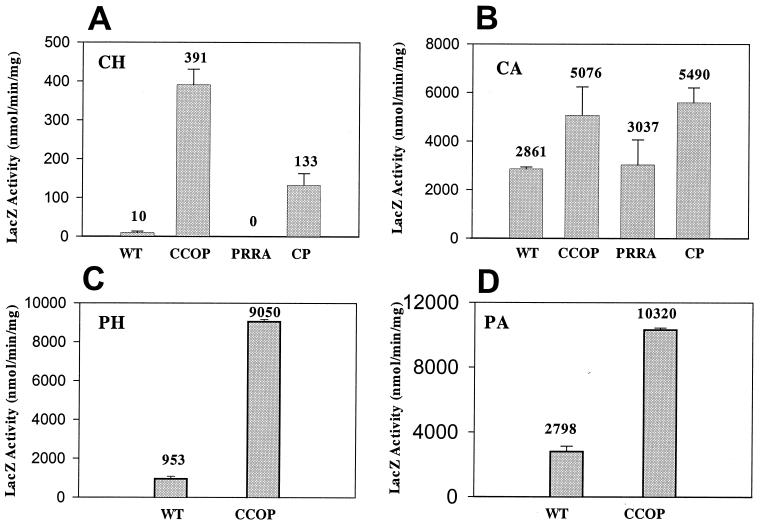

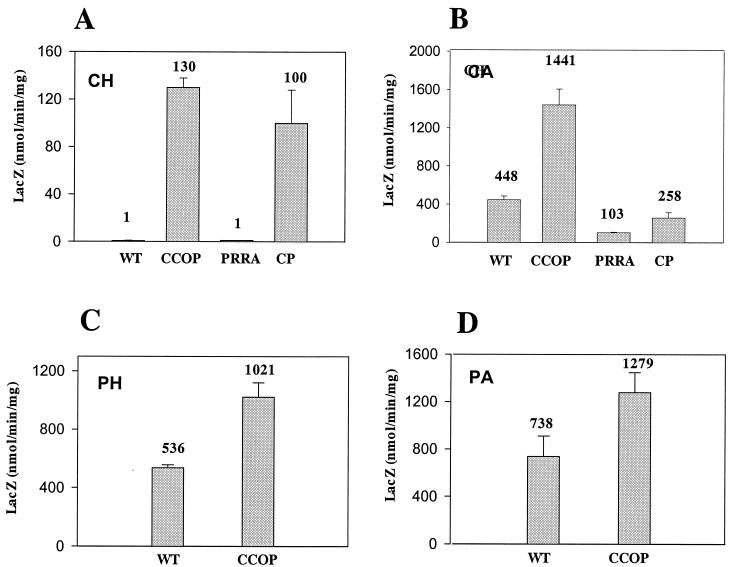

To determine whether or not the ccoP mutation was affecting transcription and to quantitate the effect, pVKC1 and pVKCII, broad-host-range plasmids containing the cbbI and cbbII promoters, respectively, translationally fused to lacZ were transferred to the various strains. β-Galactosidase activity was measured under the different growth conditions to quantitate the level of transcription. It was apparent that the effect of the ccoP mutation was exerted on both promoters at the level of transcription (Fig. 4 and 5). In the prrA mutant, cbbI and cbbII promoter activity was very low or undetectable for wild-type and prrA strains cultured chemoheterotrophically, whereas significant derepression was observed in the ccoP and ccoP prrA strains under these growth conditions (Fig. 4A and 5A). β-Galactosidase specific activities for strains harboring pVKC1, the cbbI promoter fusion (391 and 133 nmol/min/mg for the ccoP and ccoP prrA mutants, respectively), were somewhat higher than the activities obtained when these strains harbored cbbII promoter fusion pVKCII (131 and 100 nmol/min/mg, respectively). Although the trend is the same, during aerobic chemoheterotrophic growth, the negative effect of the prrA mutation on the ccoP strain was considerably less pronounced for expression directed by the cbbII promoter than for that directed by the cbbI promoter. Under chemoautotrophic growth conditions, strains containing the cbbI promoter fusion (pVKC1) exhibited increased levels of β-galactosidase activity (i.e., 1.8- to 1.9-fold-higher levels) in the ccoP and ccoP prrA strains compared to the wild type. This pattern of increased activity is reminiscent of the enhanced levels of total RubisCO activity previously observed for these strains (Table 2). Like RubisCO activity levels, the prrA strain exhibited cbbI promoter activity similar to that of the wild-type strain (Fig. 4B). By contrast, the activity profile of β-galactosidase with the cbbII promoter plasmid pVKCII in these strains was very different from that of RubisCO under chemoautotrophic growth conditions. Both prrA strains exhibited reduced β-galactosidase activity compared to the wild-type strain (Fig. 5B), with activity in the ccoP prrA and prrA mutants only 58 and 23% of that of the wild-type strain, respectively. In the ccoP strain containing the cbbII fusion, β-galactosidase activity was threefold higher than that measured in the wild-type strain. Based on the fusion activities and the Western immunoblot analyses, the prrA mutation appeared to negatively affect cbbII expression during chemoautotrophic growth. In addition, although enhanced expression from both promoters was observed in the ccoP mutant, the secondary prrA mutation affected expression from the two promoters differently. For the cbbII promoter, the positive effect of the ccoP mutation was almost completely negated in a prrA background, whereas exactly the opposite was observed for the cbbI promoter (Fig. 4B and 5B).

FIG. 4.

cbbI::lacZ fusion quantitation in R. sphaeroides ccoP and prrA mutant strains grown under different culture conditions. β-Galactosidase activity was measured in cell extracts of R. sphaeroides strains harboring plasmid pVKC1 grown to mid-exponential phase under the following growth conditions: chemoheterotrophic (CH) (A), chemoautotrophic (CA) (B), photoheterotrophic (PH) (C), or photoautotrophic (PA) (D). WT, wild-type strain 2.4.1; CCOP, strain CcoP1; PRRA, strain PrrA; CP, strain CcoPPrrA. Standard deviations are indicated as error bars. Numbers above bars are the means. All values are based on multiple assays of at least three independent cultures.

FIG. 5.

cbbII::lacZ fusion quantitation in R. sphaeroides ccoP and prrA mutant strains grown under different culture conditions. β-Galactosidase activity was measured in cell extracts of R. sphaeroides strains harboring plasmid pVKCII grown to mid-exponential phase under the following growth conditions: chemoheterotrophic (CH) (A), chemoautotrophic (CA) (B), photoheterotrophic (PH) (C), or photoautotrophic (PA) (D). WT, wild-type strain 2.4.1HR; CCOP, strain CcoP1; PRRA, strain PrrA; CP, strain CcoPPrrA. Standard deviations are indicated as error bars. Numbers above bars are the means. All values are based on multiple assays of at least three independent cultures.

Finally, cbbI and cbbII promoter activities were measured under phototrophic growth conditions in the wild-type and ccoP mutant strains in the presence or absence of organic carbon. In cultures grown photoheterotrophically on malate, the levels of β-galactosidase activity directed by the cbbI promoter in the ccoP mutant were 9.5-fold higher than those measured in the wild-type strain (Fig. 4C). The difference between cbbI::lacZ expression in the ccoP mutant and the wild-type strain was less pronounced (about 3.7-fold) during photoautotrophic growth (Fig. 4D), where the highest level of cbbI expression is normally observed. Expression from the cbbII promoter was approximately 1.7- to 1.9-fold higher in the ccoP mutant than in the wild type under both photoheterotrophic and photoautotrophic growth conditions (Fig. 5C and 5D).

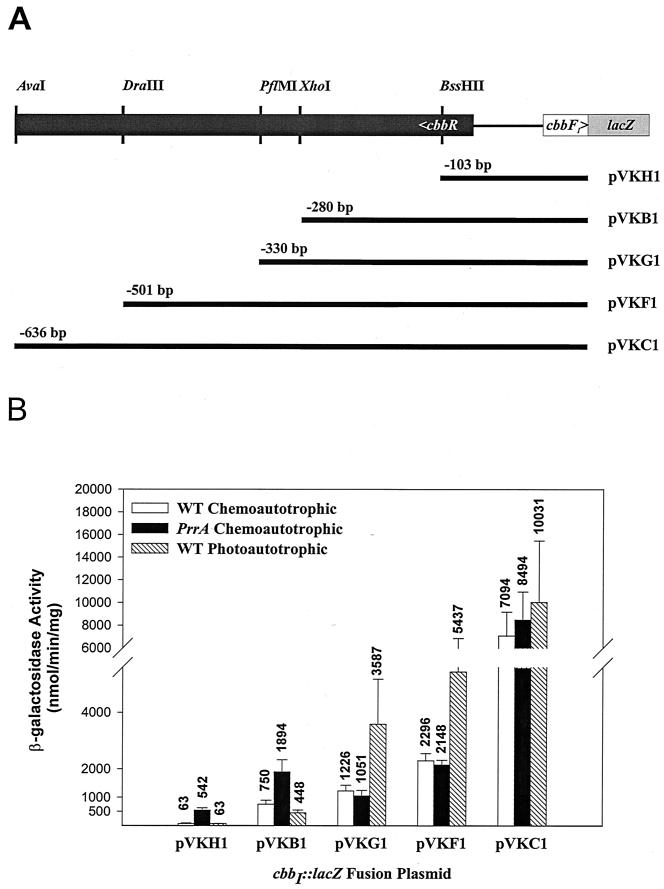

cbbI promoter elements required for chemoautotrophic gene expression.

The prrA-independent expression of the cbbI::lacZ translational fusion (pVKC1) during chemoautotrophic growth indicated that additional regulators might be involved in cbbI activation under this growth condition. Regions of the cbbI promoter important for chemoautotrophic expression were mapped and compared to those regions known to be required for phototrophic expression (1, 2). cbbI::lacZ fusion plasmids (1) containing 103 bp (pVKH1), 280 bp (pVKB1), 330 bp (pVKG1), 501 bp (pVKF1), and 636 bp (pVKC1) of upstream sequence (Fig. 6) were introduced into R. sphaeroides strains HR and PrrA, and β-galactosidase was measured after chemoautotrophic growth. Under these growth conditions, all of the fusion plasmids, with the exception of pVKG1 and pVKF1, yielded higher expression levels in the prrA mutant strain. The levels ranged from slightly over twofold for pVKB1 to over eightfold for pVKH1, suggesting that prrA may exert a negative effect on cbbI expression during chemoautotrophic growth. Examination of β-galactosidase expression patterns with successively longer cbbI promoter fusions revealed three regions primarily responsible for induction during chemoautotrophic growth. The first region, situated between bp −103 and −280 relative to the mapped cbbI transcription start site (1), was responsible for 12-and 3.5-fold increases in β-galactosidase expression in the wild-type and prrA backgrounds, respectively. The second region, between bp −501 and −636, resulted in increases in β-galactosidase expression of over 3-fold in the wild-type strain and 3.9-fold in the prrA mutant. Similar analysis of photoautotrophically grown cells using these fusions revealed a different pattern in the wild-type background. While the region between bp −103 (pVKH1) and −280 (pVKB1) conferred a sevenfold induction of β-galactosidase under photoautotrophic growth conditions, addition of the 50-bp region between bp −280 (pVKB1) and −330 (pVKG1) contributed an additional eightfold induction. This is in stark contrast to the pattern observed under chemoautotrophic growth conditions, in which the region between pVKB1 and pVKG1 is responsible for only a 1.6-fold increase in β-galactosidase activity in the wild-type strain and a 1.8-fold decrease in the prrA mutant. These results indicate that the regions upstream of the cbbI promoter that are important for activation under photoautotrophic growth conditions (1, 2) are distinct from those that are important for activation under chemoautotrophic growth conditions.

FIG. 6.

cbbI::lacZ fusions in R. sphaeroides wild-type and prrA mutant strains grown chemoautotrophically. (A) Restriction map of the cbbI promoter region, illustrating restriction sites used to make cbbI::lacZ fusions. Numbers above restriction fragments indicate the number of nucleotides from the transcriptional start site. (B) β-Galactosidase activity in cell extracts of R. sphaeroides that contained cbbI::lacZ fusions in wild-type (WT) and prrA mutant strains. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

Effect of mutations in the ccoNOQP operon on cbb promoter activity in Rhodobacter capsulatus.

PrrA (RegA) has been shown to bind to cbb promoters and activate transcription of cbb genes in R. capsulatus (31). Therefore, it was of interest to assess the effect of mutations in cco genes on cbb expression in this background. Several mutants of R. capsulatus, in which cytochrome oxidase was disrupted (14), were grown chemoheterotrophically and photoheterotrophically on malate, and extracts were assayed for RubisCO activity. The cco mutations had no apparent effect on RubisCO activity levels under chemoheterotrophic (data not shown) or photoheterotrophic (Table 3) growth conditions, growth regimens that effected the most pronounced change in RubisCO gene expression and protein accumulation in R. sphaeroides.

TABLE 3.

RubisCO activity in Rhodobacter capsulatus cco mutants

| Strain (genotype) | RubisCO activitya during photoheterotrophic growth |

|---|---|

| MT1131 (wild type) | 44 ± 1 |

| GK32 (MT1131 ccoNO) | 43 ± 3 |

| MG1 (MT1131 ccoP) | 46 ± 3 |

| M4 (ccoN) | 56 ± 2 |

Activities are expressed as nanomoles of CO2 fixed per minute per milligram of protein. Numbers represent the averages and standard deviations from multiple assays of two independent cultures.

DISCUSSION

In R. sphaeroides the prrA/regA gene product has been shown to activate a number of promoters involved in various aspects of metabolism, including photosystem biosynthesis (4), nitrogen fixation and metabolism (11, 25), and CO2 assimilation (24). Inactivation of any of the genes within the ccoNOQP operon results in aerobic derepression as well as enhanced anaerobic expression of photosystem biosynthesis genes that are regulated by prrA (4). Curiously, inactivation of ccoQ does not seem to affect cytochrome oxidase activity but does affect expression of photosystem biosynthesis genes in the same manner as in mutants in which cytochrome oxidase is inactive. Based on these observations, it was proposed that electron flow through the high-affinity Cbb3 cytochrome oxidase within the membrane of R. sphaeroides transmits a signal to sensor kinase PrrB in the presence of oxygen; this signal somehow inhibits phosphorylation of PrrB, with the ccoQ gene product mediating signal transduction from cytochrome oxidase to PrrB (20). More recent evidence suggests that in R. sphaeroides, the ccoQ gene product plays a role in protecting CcoP from proteolytic degradation under aerobic conditions and inactivation of ccoQ does indeed actually effect a decrease in cytochrome oxidase activity which is most pronounced under high aeration, explaining the deregulation of photopigment genes in the presence of O2 (22). Among the genes in R. sphaeroides that are regulated by the PrrAB (RegAB) global two-component system are the cbb operons, which encode enzymes of the CBB reductive pentose phosphate CO2 fixation pathway. Expression of both cbbI and cbbII promoters is down regulated in a prrB mutant grown photosynthetically, suggesting that the PrrA-PrrB signal transduction system positively regulates cbb gene expression (24). In the prrB mutant, pigments are also expressed at lower levels than in the wild type (10). PrrA from R. capsulatus (RegA) has been shown to bind to the cbbI and cbbII promoters of R. sphaeroides; however, direct evidence for PrrA involvement in cbb expression in vivo has been lacking, because the prrA mutant of R. sphaeroides is incapable of phototrophic growth (2), although the ability to express both form I and form II RubisCO under anaerobic carbon starvation conditions was restored in a R. sphaeroides prrA (regA) mutant complemented with plasmid-borne R. capsulatus regA (2).

In the present study, a mutation in prrA, in R. sphaeroides strains that have the capacity for aerobic chemoautotrophic growth, did not eliminate or diminish the aerobic chemoautotrophic growth potential. Chemoautotrophic growth favors enhanced cbb gene transcription, as this growth condition requires that CO2 be used as the sole source of carbon. This growth condition thus allows one the opportunity to directly test the effect of the prrA mutation on cbb expression in vivo. Using cbbI and cbbII promoter-lacZ fusions, it was shown that cbbII expression was significantly decreased in the prrA mutant grown chemoautotrophically, whereas cbbI expression remained unchanged. Expression from both the cbbI and cbbII promoters increased in the ccoP mutant during chemoautotrophic growth, but expression of the two cbb promoters in the ccoP prrA double mutant was completely different. Expression from the cbbI promoter in the double mutant was slightly elevated compared to that measured in the ccoP mutant, whereas cbbII expression was fivefold lower in the double ccoP prrA mutant compared to the ccoP strain. Further, cbbII promoter activity in the double mutant was twofold the activity measured in the prrA mutant, suggesting that the prrA mutation was not completely dominant over the ccoP mutation under these growth conditions.

Derepression of both cbb promoters in the mutant backgrounds during aerobic chemoheterotrophic growth was very similar. In each case, activity was very low or not detectable in the wild-type strain and the prrA mutant. Activity from both promoters was highest in the ccoP strain and was reduced to 34 and 76% in the ccoP prrA double mutant for the cbbI and cbbII-lac fusions, respectively. For the cbbII promoter, this mirrors the chemoautotrophic growth results exactly, in which the ccoP mutation caused a reproducible increase in activity in the prrA background.

During phototrophic growth, expression from the cbb promoters in the ccoP background was elevated. For the cbbI promoter the enhancement was most pronounced during photoheterotrophic growth. However, neither RubisCO enzyme activity measurements nor Western immunoblot analyses showed any evidence that the cbbI or cbbII promoter was activated in a ccoQ background under chemoheterotrophic or phototrophic growth conditions, suggesting that ccoQ is a specific conduit for signal transmission from cytochrome oxidase to genes required for photosystem biosynthesis or that photosystem gene expression is more sensitive to slight changes in cytochrome oxidase activity than is cbb gene expression.

The finding that expression of the cbbI promoter is either unaffected or, in some cases, enhanced by the prrA mutation, whereas expression from the cbbII promoter is severely reduced during chemoautotrophic growth is both puzzling and intriguing. There are several possible explanations that might clarify these results. An alternate transcriptional activator that may also respond to a signal derived from the Cbb3 cytochrome oxidase competing for PrrA binding sites during chemoautotrophic growth might explain the unchanged cbbI transcription in the prrA strain, an idea that is supported by the results of expression studies using the cbbI::lacZ promoter fusions that possess different amounts of upstream sequence. With the exception of plasmids pVKG1 and pVKF1, all of the cbbI::lacZ fusion plasmids showed a higher expression level in the prrA mutant background relative to the wild-type background during chemoautotrophic growth (Fig. 5). This observation indicated that PrrA might actually function as a negative regulator of cbbI expression during chemoautotrophic growth. It is possible that PrrA could interfere with the action of other cbbI transcriptional activators by competing for binding sites. A similar mechanism has been proposed for PrrA-mediated negative regulation of the hup operon in the related organism R. capsulatus (3). PrrA binding sites within the hup operon promoter were found to overlap those of the transcriptional activator integration host factor. It was proposed that PrrA exerts its negative effect by competing with integration host factor for binding. It is also possible that the negative regulatory effect is indirectly due to a disruption in other systems controlled by PrrA.

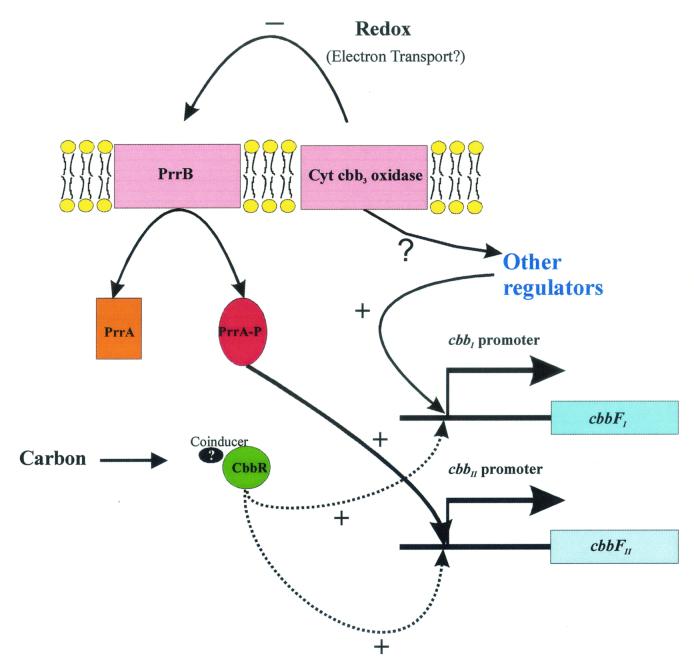

The results of the cbbI-lacZ promoter fusion expression studies with chemoautotrophic competent wild-type and prrA R. sphaeroides strains also suggest the existence of an additional transcriptional activator(s). Different regions of the cbbI promoter are important for activation during chemoautotrophic versus photoautotrophic growth (Fig. 6). During photoautotrophic growth, the portion of the cbbI promoter between bp −103 and −330 imparts the largest positive effect (57-fold) on cbbI expression. In contrast, two regions of the cbbI promoter are responsible for the majority of the observed enhancement of expression during chemoautotrophic growth. The first of these spans the sequence from bp −103 to −280 and confers increases in expression of approximately 12-and 3.5-fold in the wild-type and prrA strains, respectively. The second region occurs between bp −501 and −636 and enhances chemoautotrophic cbbI expression 3- and 3.9-fold in wild-type and prrA strains, respectively. The fact that during chemoautotrophic growth both of these regions function similarly in the wild-type and prrA mutant backgrounds suggests that they may contain binding sites for additional transcriptional activators. The presence of an additional response regulator in the PrrB pathway specific for the cbbI promoter could also explain the observed pattern of reduced cbbI and cbbII expression during phototrophic growth in the prrB mutant yet unaffected expression of the cbbI promoter during chemoautotrophic growth in the prrA mutant. Arguments against this include the lack of cbbI induction during carbon starvation in the prrA mutant and the fact that in the related organism R. capsulatus, PrrA alone is responsible for activation of both cbb operons. Finally, in the absence of PrrA, enhanced expression of cbbI genes may be influenced by the other known and specific transcriptional regulator, CbbR, to compensate for the loss of cbbII transcription. Indeed, CbbR has been shown to promote compensatory cbb transcription of one operon when the other is inactivated (9). A model illustrating cbb regulation during chemoautotrophic growth is shown in Fig. 7.

FIG. 7.

Proposed model of cbb gene regulation in R. sphaeroides during chemoautotrophic growth. The Cbb3 cytochrome (Cyt) oxidase transmits an inhibitory signal to PrrB, resulting in a shift in the equilibrium towards unphosphorylated PrrA and subsequent lack of activation of the cbbII promoter. Also shown is a signal derived from Cbb3 cytochrome oxidase activity going to an alternate transcriptional regulator that in turn activates the cbbI promoter. The model depicts transcriptional activation of both cbb operons by CbbR in response to a signal that presumably reflects the carbon status of the cell.

Whatever the reason for the lack of a negative effect of the prrA mutation on cbbI transcription under chemoautotrophic growth conditions, it is difficult to reconcile the observed cbb expression pattern and the proposed pathway for redox signal transduction via PrrA in the ccoP prrA double mutant. If PrrA is an obligatory component in the signal transduction pathway leading from CcoP (19), then cbbI and cbbII promoter activity in the double ccoP prrA mutant would be expected to be identical to that observed in the single prrA mutant unless PrrA was acting to repress activity. Although evidence obtained with the cbbI promoter-lac fusions suggests this possibility during chemoautotrophic growth, it cannot explain the pattern of chemoheterotrophic cbb expression. Finally, the fact that RubisCO activity was unchanged in various cco mutants of R. capsulatus during photoheterotrophic growth on malate suggests that signal transduction pathways from Cbb3 cytochrome oxidase are different in the two organisms.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Huiqing Fang for her skillful technical assistance. We are grateful to S. Kaplan for providing some of the R. sphaeroides strains and to F. Daldal for providing the R. capsulatus mutant strains.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM45404.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dubbs, J. M., and F. R. Tabita. 1998. Two functionally distinct regions upstream of the cbbI operon of Rhodobacter sphaeroides regulate gene expression. J. Bacteriol. 180:4903-4911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dubbs, J. M., T. H. Bird, C. E. Bauer, and F. R. Tabita. 2000. Interaction of CbbR and RegA∗ transcription regulators with the Rhodobacter sphaeroides cbbI promoter-operator region. J. Biol. Chem. 275:19224-19230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elsen, S., W. Dischert, A. Colbeau, and C. E. Bauer. 2000. Expression of uptake hydrogenase and molybdenum nitrogenase in Rhodobacter capsulatus is coregulated by the RegB-RegA two-component regulatory system. J. Bacteriol. 182:2831-2837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eraso, J. M., and S. Kaplan. 1994. prrA, a putative response regulator involved in oxygen regulation of photosynthesis gene expression in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol. 176:32-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eraso, J. M., and S. Kaplan. 1995. Oxygen-insensitive synthesis of the photosynthetic membranes of Rhodobacter sphaeroides: a mutant histidine kinase. J. Bacteriol. 177:2695-2706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Figurski, D. H., and D. R. Helinski. 1979. Replication of an origin-containing derivative of plasmid RK2 dependent on a plasmid function provided in trans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76:1648-1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gibson, J. L., D. L. Falcone, and F. R. Tabita. 1991. Nucleotide sequence, transcriptional analysis, and expression of genes encoded within the form I CO2 fixation operon of Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Biol. Chem. 266:14646-14653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gibson, J. L., and F. R. Tabita. 1993. Nucleotide sequence and functional analysis of CbbR, a positive regulator of the Calvin cycle operons of Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol. 175:5778-5784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gibson, J. L., and F. R. Tabita. 1997. Analysis of the cbbXYZ operon in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol. 179:663-669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gomelsky, M., and S. Kaplan. 1995. Isolation of regulatory mutants in photosynthesis gene expression in Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1 and partial complementation of a PrrB mutant by the HupT histidine-kinase. Microbiology 141:1805-1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joshi, H. M., and F. R. Tabita. 1996. A global two component signal transduction system that integrates the control of photosynthesis, carbon dioxide assimilation, and nitrogen fixation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:14515-14520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jouanneau, Y., and F. R. Tabita. 1986. Independent regulation of synthesis of form I and form II ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase-oxygenase in Rhodopseudomonas sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol. 165:620-624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kappler, U., Huston, W. M., and A. G. McEwan. 2002. Control of dimethylsulfoxide reductase expression in Rhodobacter capsulatus: the role of carbon metabolites and the response regulators DorR and RegA. Microbiology 148:605-614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koch, H.-G., O. Hwang, and F. Daldal. 1998. Isolation and characterization of Rhodobacter capsulatus mutants affected in cytochrome cbb3 oxidase activity. J. Bacteriol. 180:969-978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London) 277:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Markwell, M. A., S. M. Haas, L. L. Bieber, and N. E. Tolbert. 1978. A modification of the Lowry procedure to simplify protein determination in membrane and lipoprotein samples. Anal. Biochem. 87:206-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mosley, C. S., J. Y. Suzuki, and C. E. Bauer. 1995. Identification and molecular genetic characterization of a sensor kinase responsible for coordinately regulating light harvesting and reaction center gene expression in response to anaerobiosis. J. Bacteriol. 177:3359.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Gara, J. P., and S. Kaplan. 1997. Evidence for the role of redox carriers in photosynthesis gene expression and carotenoid biosynthesis in Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1. J. Bacteriol. 179:1951-1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O'Gara, J. P., J. M. Eraso, and S. Kaplan. 1998. A redox-responsive pathway for aerobic regulation of photosynthesis gene expression in Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1. J. Bacteriol. 180:4044-4050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oh, J. I., and S. Kaplan. 1999. The cbb3 terminal oxidase of Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1: structural and functional implications for the regulation of spectral complex formation. Biochemistry 38:2688-2696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oh, J. I., J. M. Eraso, and S. Kaplan. 2000. Interacting regulatory circuits involved in orderly control of photosynthesis gene expression in Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1. J. Bacteriol. 182:3081-3087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oh, J. I., and S. Kaplan. 2002. Oxygen adaptation: the role of the CcoQ subunit of the cbb3 cytochrome c oxidase of Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1. J. Biol. Chem. 277:16620-16628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paoli, G. C., and F. R. Tabita. 1998. Aerobic chemolithoautotrophic growth and RubisCO function in Rhodobacter capsulatus and a spontaneous gain of function mutant of Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Arch. Microbiol. 170:8-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qian, Y., and F. R. Tabita. 1996. A global signal transduction system regulates aerobic and anaerobic CO2 fixation in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol. 178:12-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qian, Y., and F. R. Tabita. 1998. Expression of glnB and a glnB-like gene (glnK) in a ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase-deficient mutant of Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol. 180:4644-4649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sambrook, J., J. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 27.Scolnik, P. A., M. A. Walker, and B. L. Marrs. 1980. Biosynthesis of carotenoids derived from neurosporene in Rhodopseudomonas capsulata. J. Biol. Chem. 255:2427-2432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tabita, F. R. 1988. Molecular and cellular regulation of autotrophic carbon dioxide fixation in microorganisms. Microbiol. Rev. 52:155-189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tabita, F. R. 1995. The biochemistry and molecular regulation of carbon metabolism and CO2 fixation in purple bacteria, p. 885-914. In R. E. Blankenship, M. T. Madigan, and C. E. Bauer (ed.), Anoxygenic photosynthetic bacteria. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.

- 30.Towbin, H., T. Staehelin, and J. Gordon. 1979. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76:4350-4354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vichivanives, P., T. H. Bird, C. E. Bauer, and F. R. Tabita. 2000. Multiple regulators and their interactions in vivo and in vitro with the cbb regulons of Rhodobacter capsulatus. J. Mol. Biol. 300:1079-1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang, X., D. L. Falcone, and F. R. Tabita. 1993. Reductive pentose phosphate-independent CO2 fixation in Rhodobacter sphaeroides and evidence that ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase activity serves to maintain the redox balance in the cell. J. Bacteriol. 175:3372-3379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weaver, K. E., and F. R. Tabita. 1983. Isolation and partial characterization of Rhodopseudomonas sphaeroides mutants defective in the regulation of ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase. J. Bacteriol. 156:507-515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yanisch-Perron, C., J. Vieira, and J. Messing. 1985. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene 33:103-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zeilstra-Ryalls, J., M. Gomelsky, J. M. Eraso, A. Yeliseev, J. O'Gara, and S. Kaplan. 1998. Control of photosystem formation in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol. 180:2801-2809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]