Abstract

Regulated gene expression is a complex process achieved through the function of multiple protein factors acting in concert at a given promoter. The transcription factor TFIID is a central component of the machinery regulating mRNA synthesis by RNA polymerase II. This large multiprotein complex is composed of the TATA box binding protein (TBP) and several TBP-associated factors (TAFIIs). The recent discovery of multiple TBP-related factors and tissue-specific TAFIIs suggests the existence of specialized TFIID complexes that likely play a critical role in regulating transcription in a gene- and tissue-specific manner. The tissue-selective factor TAFII105 was originally identified as a component of TFIID derived from a human B-cell line. In this report we demonstrate the specific induction of TAFII105 in cultured B cells in response to bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS). To examine the in vivo role of TAFII105, we have generated TAFII105-null mice by homologous recombination. Here we show that B-lymphocyte development is largely unaffected by the absence of TAFII105. TAFII105-null B cells can proliferate in response to LPS, produce relatively normal levels of resting antibodies, and can mount an immune response by producing antigen-specific antibodies in response to immunization. Taken together, we conclude that the function of TAFII105 in B cells is likely redundant with the function of other TAFII105-related cellular proteins.

The control of gene expression is a highly complex process requiring the combinatorial efforts of numerous protein factors that interact with regulatory DNA elements. In eukaryotes, protein-encoding genes are transcribed by RNA polymerase II (RNA Pol II). The molecular machinery that guides RNA Pol II to initiate transcription of a specific gene is composed of multiple classes of regulatory proteins. These regulators include general transcription factors, DNA-binding transcriptional activators and repressors, bridging modules designated coactivators, and chromatin-modifying enzymes (17). Acting in concert, this machinery regulates the activity of RNA Pol II in a temporal and spatial manner. The TFIID complex is a key transcription factor, conserved from Saccharomyces cerevisiae to humans, that is a core component of the RNA Pol II regulatory machinery. TFIID is a large multiprotein complex composed of the TATA box binding protein (TBP) and several TBP-associated factors (TAFIIs). Early biochemical studies of TFIID indicated that the TAFIIs functioned in core promoter recognition and were responsible for directing RNA Pol II to select genes in response to upstream activators (7, 23, 35, 38). In addition, the largest subunit of TFIID, TAFII250, was shown to be required for progression through the cell cycle in hamster cells (29). More recent genetic studies with yeast and Drosophila melanogaster have confirmed a prominent requirement for TAFIIs in transcription of many eukaryotic genes (1, 13, 16, 21, 43). Together, these studies highlight the critical requirement for the TAFIIs and TFIID in the process of regulating gene expression in eukaryotic cells.

Although TFIID was initially thought to be ubiquitous in expression and function, identification of putative tissue-specific TAFIIs suggested that specialized TFIID complexes could play a direct role in regulating tissue-specific programs of gene expression. The first cell type-specific TFIID subunit identified was TAFII105, which coprecipitated with TBP and other prototypic TAFIIs from a highly differentiated human B-cell line (4). The amino acid sequence of TAFII105 revealed that it was highly related to the broadly expressed human TAFII130 and its Drosophila homolog dTAFII110 (4, 11, 20, 36). This family of TAFIIs contains an amino-terminal coactivator domain responsible for activator association and a highly conserved carboxy-terminal TFIID-interaction domain (6, 25). While the related yeast TAFII48 contains a conserved C-terminal domain, the amino-terminal domain is absent, suggesting that this coactivator domain functions to regulate programs of transcription that are specific to metazoan organisms (26). In support of this notion, it has recently been shown that TAFII105 is required for proper gene expression in the mammalian ovary (5). Furthermore, identification of TAFII105 in B-cell-derived TFIID complexes, as opposed to TFIID derived from other cell lines, suggested that TAFII105 might play a role in regulating B-cell-specific programs of gene expression. In agreement with this hypothesis, human TAFII105 has been shown to associate with known regulators of B-cell transcription, including members of the NF-κB/Rel family of transcription factors and OCA-B (also called OBF-1 and Bob1), a B-cell-specific coactivator (39-41). Recently, nuclear retention of TAFII105 was shown to occur in B cells in response to mitogenic stimulation, and a putative dominant-negative version of TAFII105 was shown to disrupt NF-κB-dependent apoptotic survival in B cells (24, 31). Together, these studies suggest a role of TAFII105 and putative TAFII105-related proteins in transcriptional regulation of B lymphocytes.

To more directly characterize the potential role of TAFII105 in regulating transcription in B cells, we have used homologous recombination in the mouse to establish a TAFII105-null mouse line. The generation of this mouse and the identification of an essential role for TAFII105 in ovarian development have been described previously (5). Here we report that B-cell development and function are not significantly compromised in the absence of TAFII105. Although expression of TAFII105, and not that of other components of the RNA Pol II machinery, is induced in primary B cells stimulated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS), TAFII105-null B cells are able to proliferate in response to LPS. B-cell development is not significantly altered in the absence of TAFII105. In addition, levels of all resting immunoglobulin (Ig) subtypes tested are not reduced in TAFII105-null mice. Finally, when immunized, TAFII105-null mice successfully produce antigen-specific antibodies, and germinal centers are readily detected in the spleen. These data indicate that TAFII105 is not essential for the B-cell functions we have tested so far but rather appears to be redundant with the function of other TAFII105-related cellular proteins. These data underscore the apparent overlapping of functions of important transcription factors encoded within the genomes of mammalian organisms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

B-cell purification and LPS stimulation.

B-cell suspensions were obtained from spleens disrupted between frosted glass slides and then purified as previously described (30). Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis was used to obtain the percentage of resting B220-positive cells at the start of the experiment. Purified B cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal calf serum, penicillin-streptomycin, and 50 mM B-mercaptoethanol. For the induction experiments for which results are shown in Fig. 1A, purified B cells were derived from wild-type C57BL6/J mice and cultured with 30 μg of bacterial LPS/ml for 1 to 4 days. For the proliferation assays for which results are shown in Fig. 2, B cells were purified from spleens derived from TAFII105+/+, TAFII105+/−, and TAFII105−/− littermates. By use of a 96-well plate and completion of each condition in triplicate, 105 B cells were incubated in 200 μl of medium containing 0, 11, 33, or 100 μg of LPS/ml. After 48 h, 1 μCi of [methyl-3H]thymidine was added to each well, and cells were incubated for an additional 12 h. The plate was then frozen on dry ice, and [3H]thymidine incorporation was measured by a scintillation counter. Developing B-cell populations in the bone marrow were characterized as in the work of Hardy et al. (9) Single-cell bone marrow suspensions were collected from three TAFII105+/− and three TAFII105−/− littermates, depleted of erythrocytes by incubation in NH4Cl, and incubated with an FcR blocker (2.4G2). The following antibodies were used to stain 1.5 × 106 cells: fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-IgMa and -b (II/41), phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-B220 (RA3-6B2), biotinylated-anti-CD43 (S7), and Streptavidin-QuantumRed (Sigma). Cell sorting was performed with an Epics Elite cell sorter (Beckman Coulter), and more than 100,000 events were collected after gating for live lymphocytes.

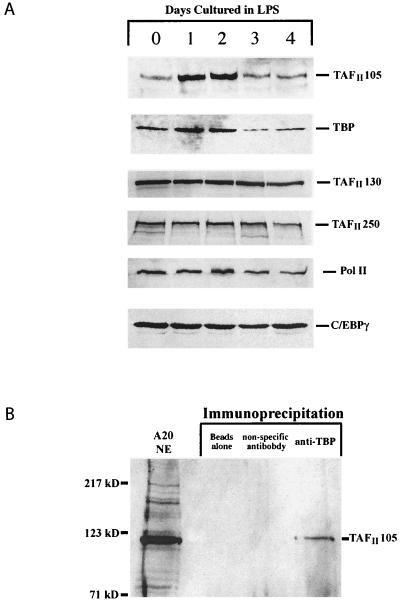

FIG. 1.

TAFII105 is induced in LPS-stimulated B lymphocytes. (A) Western blot analysis of TAFII105 and other components of the RNA Pol II machinery in resting and LPS-stimulated B cells (cultured in LPS for 0 and 1 to 4 days, respectively) purified from wild-type spleens. Fifty micrograms of each protein sample was loaded per lane. Positions of specific proteins are indicated on the right. (B) Mouse TAFII105 specifically coprecipitates with TBP in nuclear extracts derived from A20 mouse B cells. Immunoprecipitation was followed by Western blot analysis using anti-mouse TAFII105 antibodies. Molecular size markers are indicated on the left, and the position of the mouse TAFII105-specific band is indicated on the right.

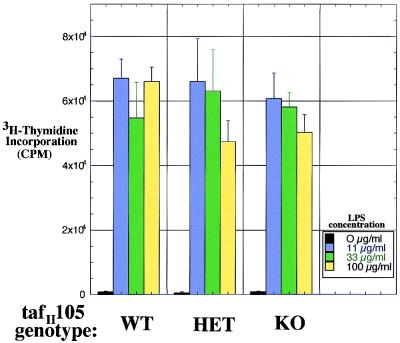

FIG. 2.

LPS-dependent proliferation in the absence of TAFII105. Splenic B cells were purified from TAFII105+/+ (WT), TAFII105+/− (HET), and TAFII105−/− (KO) mice. Proliferation was measured by incorporation of [3H]thymidine in the absence of LPS (black bars) or in response to increasing concentrations of LPS (11, 33, and 100 μg/ml, indicated by blue, green, and yellow bars, respectively). Levels of [3H]thymidine incorporation were measured by scintillation counting.

Western blotting and immunoprecipitation.

For LPS stimulation experiments, purified splenic B cells were extracted in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer for 60 min at 4°C. After determination of protein concentration by use of a standard Bradford assay, 50 μg of total protein per lane was loaded onto a sodium dodecyl sulfate-7.5% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-7.5% PAGE) gel. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and probed with the following primary antibodies: a polyclonal antibody (PAb) against mouse TAFII105 (1:5,000), a PAb against human TBP (hTBP) (1:2,500), a monoclonal antibody (MAb) against hTAFII130 (1:500; Becton Dickinson Transduction Laboratories), a PAb against hTAFII250 (1:2,500), a PAb against hPol II (1:1,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and a PAb against C/EBPγ (1:5,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-IgG secondary antibody (Pierce) was diluted 1:5,000, and proteins were visualized with ECL (Amersham Pharmacia). For immunoprecipitation, nuclei were prepared from mouse A20 B cells by using a hypotonic buffer and a nuclear stabilization buffer containing 50% glycerol and 25% sucrose. Pelleted nuclei were extracted with HEMG (25 mM HEPES [pH7.9], 0.1 mM EDTA, 12.5 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol) containing 420 mM NaCl, and nuclear extracts were dialyzed to 100 mM NaCl, and NP-40 was added to 0.05%. A 20-μl volume of protein A beads was incubated in 300 μl of phosphate-buffered saline containing 10 μl of affinity-purified anti-TBP antibodies or 10 μl of an affinity-purified nonspecific antibody for 60 min at room temperature. A 300-μl volume of nuclear extract was incubated with beads for 4 h at 4°C, and precipitates were washed eight times with HEMG containing 100 to 500 mM KCl. Beads were boiled in sample buffer and separated on an SDS-7.5% PAGE gel. Primary anti-mouse TAFII105 antisera were diluted 1:5,000 and developed as above.

Ig isotype measurement.

Sera from age- and sex-matched TAFII105+/+, TAFII105+/−, and TAFII105−/− littermates were collected, and resting antibody levels were measured by using a sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Briefly, 100 μl of a panspecific anti-mouse Ig capture antibody (10 μg/ml; Southern Biotechnology) was used to coat a 96-well plate on which 50 μl of a 1:1,000 dilution of serum in borate-buffered saline-1% fetal bovine serum was assayed. A 50-μl volume of 100-ng/ml isotype-specific alkaline phosphatase (AP)-conjugated antibodies (Southern Biotechnology) was used to detect specific Ig isotypes. The AP substrate methylumbelliferyl phosphate (Sigma) was incubated after the secondary antibody, and plates were read in a fluorescence plate reader at 420 nm. Serial dilutions of Ig standards were measured for each isotype and used to establish a standard curve to determine levels of Ig isotypes in serum.

Immunization and germinal-center formation.

Age-matched 6-week-old TAFII105+/− and TAFII105−/− (three of each) littermates were immunized with an intraperitoneal injection of 100 μg of alum-precipitated nitrophenyl (NP)15-chicken gamma globulin (NP-CG). Serum was collected 8 days postinjection from the immunized animals and from a nonimmunized TAFII105+/− control littermate. A sandwich ELISA was used to measure the levels of anti-NP antibodies. Ninety-six-well plates were coated with 100 μl of 50-μg/ml NP15-conjugated bovine serum albumin. A 1:1,000 dilution of serum was serially diluted twofold, and 100 μl of each dilution was used in the assay. A horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (Southern Biotechnology) was used at a 1:1,000 dilution. Samples were developed with 2,2′-azinobis(3-ethylbenzthiazolinesulfonic acid) (ABTS; Roche) and read at 405 nm. For germinal-center formation, 10-μm-thick frozen spleen sections were prepared 12 days post-NP-CG immunization. Germinal-center formation was measured by using a peanut agglutinin (PNA)- and biotin-conjugated antibody (Sigma) at a 1:500 dilution. Slides were incubated with a 1:1,000 dilution of streptavidin-AP (Roche) and then developed with nitroblue tetrazolium-BCIP (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate) (Roche). A blue-purple precipitate is indicative of germinal-center formation.

Transcription assays.

NF47 TAFII105−/− embryonic stem (ES) cells were transiently transfected for 24 to 48 h by using Effectene (Qiagen). The activity of 200 ng of a 5XGAL4-E1B-luciferase reporter was normalized to Renilla luciferase activity after use of 50 ng of a simian virus 40-Renilla internal control plasmid (Promega). The following proteins were expressed either alone or as Gal4 fusion proteins by use of 50 ng of the Gal4 expression plasmid (encoding DNA-binding domain residues 1 to 94) pCGNGAL4: VP16 residues 413 to 490, NF-κB/p65 residues 364 to 551, Sp1 residues 83 to 621, and OCA-B residues 120 to 256. Transient transfections were completed in triplicate; average luciferase values and standard deviations are shown.

RESULTS

Induction of TAFII105 in LPS-stimulated B cells.

The specific association of TAFII105 with TFIID derived from Daudi B cells, and not other cell lines, suggested that TAFII105 might play a role in transcription of B-cell-specific genes (4). However, although Daudi cells are of B-cell origin, their extensive propagation in culture may have resulted in the fortuitous overexpression of TAFII105. To distinguish between these possibilities, we set out to characterize the expression of TAFII105 in primary B cells. B lymphocytes were purified from spleens of wild-type mice, and whole-cell protein extracts were prepared. More than 90% of the cells at the start of the experiment were B220 positive, as analyzed by FACS, indicative of successful purification of B cells (data not shown). Western blot analyses of these extracts utilizing a panel of antibodies directed against multiple components of the RNA Pol II transcriptional machinery are shown in Fig. 1A. These extracts were prepared either from resting B cells directly extracted after purification or from activated B cells cultured in a standard regimen of bacterial LPS. Compared to levels in extracts from cells cultured for 1 or 2 days in the presence of LPS, only low levels of TAFII105 were detected in extracts from cells in the absence of LPS. Interestingly, by days 3 and 4 of LPS induction, TAFII105 levels had returned to their preinduction levels. While levels of TBP are somewhat similarly affected by LPS stimulation, levels of TAFII250, TAFII130, the largest subunit of RNA Pol II, and C/EBPγ are not induced by LPS treatment. Since TBP is involved in transcription by all three RNA polymerases in the cell, it is difficult to ascertain whether its induction is related to transcription by RNA Pol II or not. However, the specific induction of TAFII105, and not of the highly related TAFII homolog TAFII130, suggests that TAFII105 likely functions during the physiological response of B cells to activation by LPS. These data further establish a role of TAFII105 in B cells first proposed by the identification of TAFII105-containing TFIID complexes in proliferating B cells.

Since we detected induction of TAFII105 in LPS-stimulated B cells, we next wanted to examine the ability of mouse TAFII105 to associate with TBP in nuclear extracts derived from mouse B cells. To this end, nuclear extracts prepared from mouse A20 B cells were precipitated with anti-TBP antibodies. Western blot analysis (Fig. 1B) reveals the ability of mouse TAFII105 to specifically coprecipitate with TBP in these B-cell nuclear extracts. As expected, no TAFII105 was detected in control precipitations using either beads alone or a nonspecific antibody. These data establish that TAFII105 is a bona fide TBP-associated factor in nuclear extracts derived from murine B cells, as had previously been shown with human B-cell lines. Moreover, in combination with the specific induction of TAFII105 in response to LPS stimulation, these studies suggest a corresponding increase in the pool of TAFII105-containing TFIID complexes in the nucleus. Such specialized TFIID complexes may in turn target specific B-cell promoters for activation, allowing the B-cell transcriptional machinery to respond rapidly to LPS.

LPS-stimulated B-cell proliferation in the absence of TAFII105.

The induction of TAFII105 by LPS in purified B cells cultured in vitro suggested that TAFII105 might play an important role in transcription of genes during B-cell activation. To examine the in vivo role of TAFII105 in the development and function of the immune system, we disrupted the endogenous TAFII105 gene by homologous recombination. TAFII105-deficient mice are viable and display no gross developmental defects (5). However, female mice lacking TAFII105 are infertile owing to a defect in proper development of the ovarian follicle during oocyte maturation (5). We also set out to assess the function of TAFII105 in the immune system. First, we confirmed the absence of any detectable TAFII105 protein expression in LPS-stimulated splenic B cells derived from the TAFII105-null mice (5). We next asked whether such TAFII105-null B cells proliferated normally in response to LPS stimulation. B-cell proliferation was measured by incorporation of [3H]thymidine in response to increasing concentrations of LPS. The results of such a proliferation assay are shown in Fig. 2. Splenic B cells derived from TAFII105+/+, TAFII105+/−, and TAFII105−/− mice responded similarly to LPS treatment. In the absence of LPS, little proliferation was observed, whereas all three cell populations proliferated in response to increasing concentrations of LPS. These data indicate that B cells that lack TAFII105 can proliferate in response to LPS at least as well as matched B cells that contain TAFII105. Although TAFII105 is induced in B cells treated with LPS, its expression does not appear to be essential for the proper proliferative response of B cells to LPS stimulation.

Resting antibody levels in TAFII105-null mice.

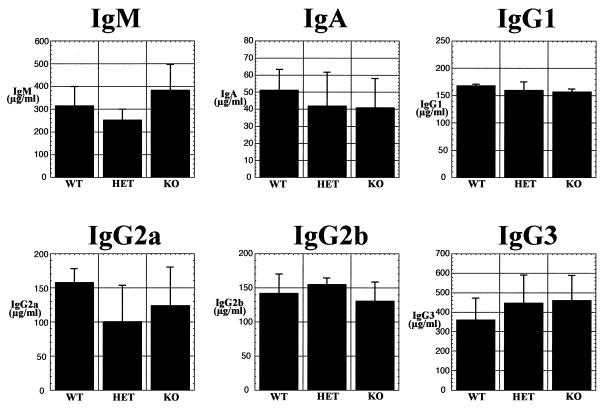

One of the major functions of B lymphocytes is to produce large numbers of circulating antibodies. To further investigate the potential role of TAFII105 in the immune system, we measured multiple antibody levels in the sera of TAFII105-null mice. Serum samples were collected from eight mice of each TAFII105 genotype, and an ELISA was used to measure levels of IgM, IgA, IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, and IgG3. Results of these ELISAs are shown in Fig. 3. The levels of all antibodies tested were relatively equivalent in the sera of TAFII105−/− mice and those of TAFII105+/+ and TAFII105+/− mice. In addition, levels of a number of antibodies at the cell surface and antibody switching in vitro were relatively equivalent in B cells derived from wild-type and mutant TAFII105 mice (R. Freiman, S. Albright, and R. Tjian, unpublished data). Together, these data indicate that disruption of the TAFII105 gene does not have a severe effect on the levels of the Ig subtypes tested in the serum and at the cell surface. In addition, the ability of the TAFII105-null mice to secrete multiple IgG subtypes suggests that the process of Ig isotype switching is not significantly affected by the absence of TAFII105.

FIG. 3.

Levels of resting antibodies in serum. In each graph, the Ig isotype is indicated at the top, the genotype of the animal from which the serum was derived is indicated at the bottom, and the respective concentration of the antibody in serum is indicated on the left. WT, TAFII105+/+; HET, TAFII105+/−; KO, TAFII105−/−.

Specific antibody production and germinal-center formation.

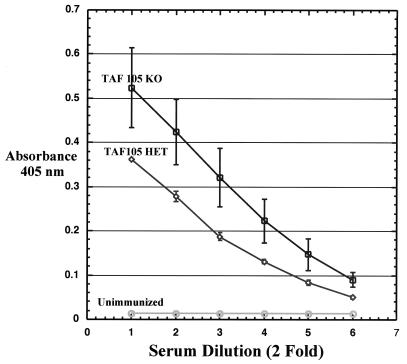

The relative abundance of Ig subtypes in the TAFII105-null mice indicates that in unchallenged animals TAFII105 is not essential for production and/or secretion of resting levels of antibodies. However, TAFII105 could be required at a different step during antibody production. More specifically, TAFII105 might function in the response of the immune system to challenge by a specific antigen. To test the ability of TAFII105-deficient mice to respond to a specific antigen, we immunized mice with NP-CG. Serum samples were collected from either nonimmunized or NP-CG-immunized TAFII105+/− and TAFII105−/− mice. Results of these experiments are shown in Fig. 4. We detected relatively equivalent levels of anti-NP antibodies in serum samples from +/− and −/− mice. In contrast, we detected only very low levels of anti-NP antibodies in serum from a nonimmunized mouse. These data indicate that in the absence of TAFII105, mice are able to mount an immune response to NP-CG and produce NP-specific antibodies. These data suggest that TAFII105 is dispensable for proper antigen recognition, antibody production, and secretion.

FIG. 4.

Production of antigen-specific antisera. The ability of TAFII105-null (KO) mice, relative to that of TAFII105+/− (HET) mice, to respond to a specific antigen was measured after immunization with NP-CG. Levels of NP-specific antibodies were measured by using a sandwich ELISA. A nonimmunized TAFII105+/− mouse served as a negative control for anti-NP antibodies.

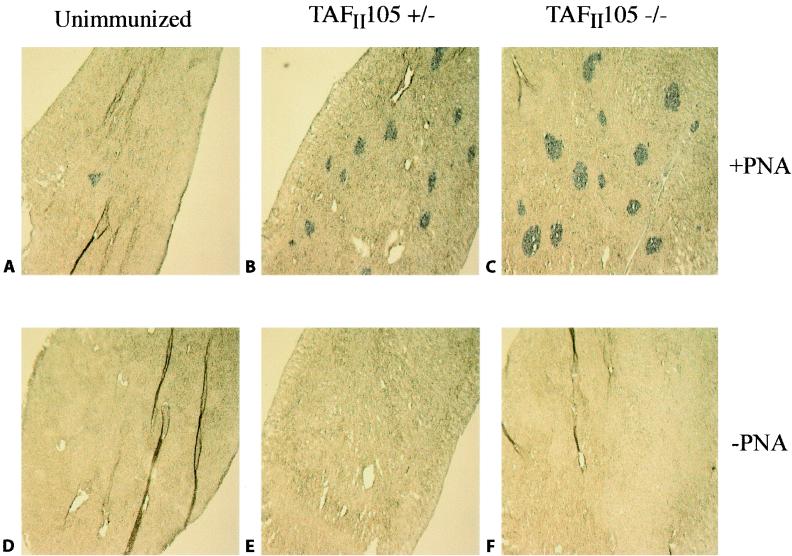

In addition to looking at the production of antigen-specific antibodies, we wanted to know whether germinal-center formation was detectable in spleens derived from immunized TAFII105-null mice. Germinal centers are sites of antigen-dependent B-cell maturation in the spleen and lymph nodes. To assay for germinal-center formation, spleen sections were prepared from nonimmunized and NP-CG-immunized mice and were stained with the lectin PNA. Figure 5 shows spleen sections stained in the presence (A through C) or absence (D and E) of PNA. Germinal-center formation, as detected by small regions of purple staining, is evident in immunized spleens derived from either TAFII105+/− or TAFII105−/− mice. These germinal centers were detectable only when the staining procedure included PNA and the animals were immunized with NP-CG. The ability of the TAFII105-null mice to produce germinal centers is consistent with the ability of these mice to produce anti-NP antibodies in response to immunization. These data indicate that mice lacking TAFII105 are capable of mounting an immune response to the antigen NP-CG and suggest that TAFII105 is not generally required for proper B-cell-mediated immune responses in the mouse.

FIG. 5.

Germinal-center formation in the absence of TAFII105. Spleen sections were derived from NP-CG-immunized TAFII105+/− and TAFII105−/− animals. The nonimmunized control is a TAFII105+/− animal that did not receive NP-CG immunization. Top panels represent staining in the presence of the lectin PNA to detect germinal centers, and bottom panels show similar sections stained with everything except PNA, demonstrating any background in the experiment. Genotypes of the immunized animals are indicated at the top.

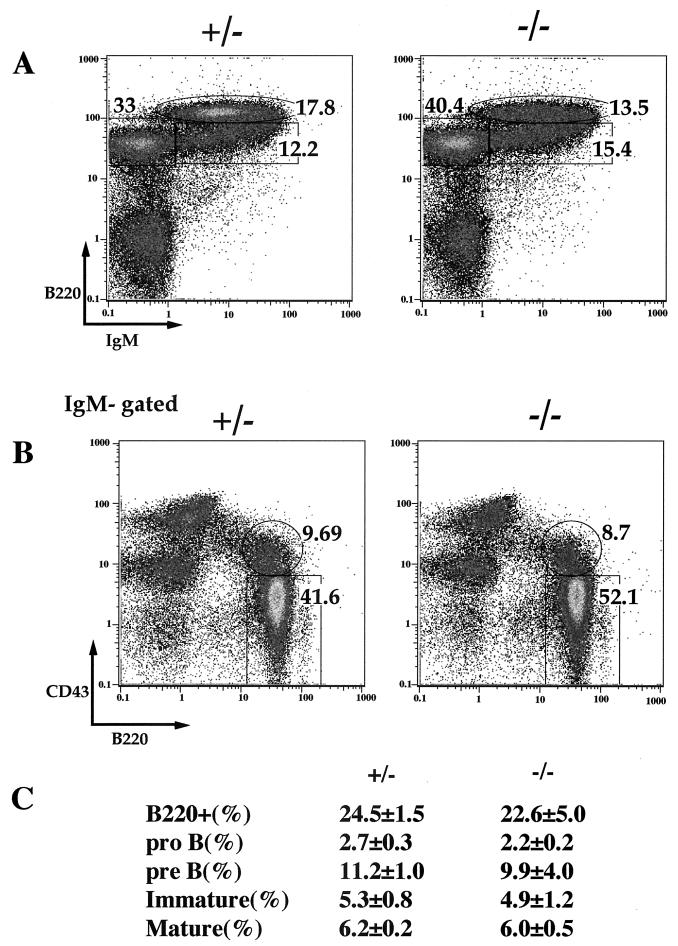

B-cell development in TAFII105-null mice.

Functional assays using TAFII105-null B cells failed to reveal any significant effect of TAFII105 deletion. To look more directly at B-cell development, we examined B-cell lineages in bone marrow derived from TAFII105+/− and TAFII105−/− littermates. Results of these experiments are shown in Fig. 6. FACS plots of representative TAFII105+/− and TAFII105−/− littermates comparing mature versus immature B cells (Fig. 6A) and pro-B versus pre-B cells (Fig. 6B) indicate that disruption of TAFII105 has no significant effect on B-cell development. In addition, the percentages of various B-cell lineages were enumerated (Fig. 6C). Together, these data indicate that the function of TAFII105 alone is not critical during B-cell development, which is consistent with the ability of TAFII105-null B cells to function properly in antibody production and immune response.

FIG. 6.

B-cell development in TAFII105-null mice. (A) Mature versus immature B-cell populations in the bone marrow of TAFII105+/− and TAFII105−/− littermates. IgM and B220 levels are plotted in log scale on the x and y axes, respectively. (B) Pro- versus pre-B-cell populations in TAFII105+/− and TAFII105−/− littermates. B220 and CD43 levels are plotted in log scale on the x and y axes, respectively. (C) Percentages of various B-cell compartments, relative to total nucleated cells, in TAFII105+/− and TAFII105−/− bone marrow. Standard deviations are shown.

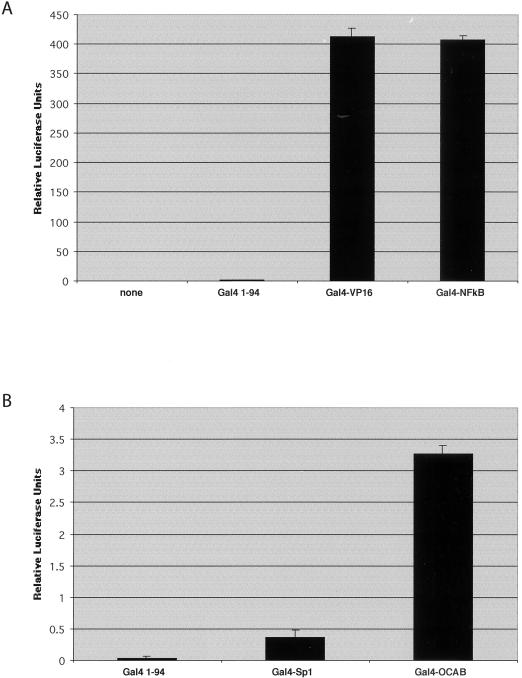

Transcriptional activation in cells lacking TAFII105.

The association of human TAFII105 with NF-κB and OCA-B suggested that TAFII105 functions in transcriptional regulation in B lymphocytes. We therefore tested the ability of activation domains derived from the p65 subunit of NF-κB and from OCA-B to function in cells lacking TAFII105. Such cells were derived by selection of TAFII105 heterozygous ES cells in high levels of G418, yielding homozygous TAFII105-null ES cells. The absence of TAFII105 protein expression in these cells was confirmed by Western blot analysis (data not shown). Proteins containing various activation domains fused to the Gal4 DNA-binding domain were transiently expressed in TAFII105−/− ES cells, and a luciferase reporter gene containing five copies of a Gal4 binding site was used to measure activation. Results of these experiments are shown in Fig. 7. Both Gal4-NFκB (Fig. 7A) and Gal4-OCAB (Fig. 7B) are able to activate transcription to appreciable levels over activation by the Gal4 DNA-binding domain alone. These data indicate that TAFII105 is not absolutely required for the ability of these activation domains to function in these cells and suggest that these activators can also utilize other coactivators, possibly TAFII105-related proteins, to signal the basal machinery.

FIG. 7.

Transcriptional activation in TAFII105-null ES cells. Solid bars, relative luciferase units for each Gal4 fusion protein, measured in triplicate. Error bars, standard deviations.

DISCUSSION

When first identified, the general transcription factor TFIID was proposed to perform a universal function in the regulation of gene expression by RNA Pol II. This function has since been described and includes core promoter recognition and activator-dependent recruitment of RNA Pol II. Recent experiments have revealed selective expression and function of alternate TFIID and TFIID-related subunits. These studies are indicative of basal transcription complexes that can play critical roles in directing gene- and tissue-specific transcriptional regulation (3, 5, 10, 12, 14, 19, 34, 37, 42). Such a tissue-selective function of TFIID is highlighted by characterization of the TAFII105 subunit of TFIID. TAFII105 was identified as a polypeptide that coprecipitated with TBP and other TAFIIs in a human B-cell line (4). Subsequent studies have shown that TAFII105 can associate with B-cell-specific components of the transcriptional machinery (39-41). Together, these findings implicated TAFII105 as a potential cofactor of B-cell-specific programs of gene expression.

To elucidate the function of TAFII105 in the immune system, we have specifically disrupted expression of TAFII105 in the mouse by homologous recombination. Although mice lacking TAFII105 are viable and display no major defects in growth and metabolism, female mice lacking TAFII105 are infertile (5). Characterization of TAFII105-deficient ovaries has identified an essential function of TAFII105 in the process of ovarian follicular development (5). In addition, expression of a number of genes known to function in fertility was abolished, suggesting that TAFII105 plays a critical role in regulating ovarian programs of gene expression (5). Here we report that, in contrast to our findings for the ovary, TAFII105 plays a nonessential role in the immune system. Mice lacking TAFII105 were capable of producing healthy numbers of B lymphocytes that proliferated in response to LPS. Furthermore, TAFII105-null B cells were capable of secreting normal levels of multiple Ig isotypes and could produce antigen-specific antibodies when mice were immunized. These studies suggest that although TAFII105 may function in regulating transcription in B cells, the function of TAFII105 in the immune system may be redundant with those of other cellular factors. Alternatively, we may have overlooked an essential role of TAFII105 in B cells by necessarily only assaying specific parameters of immune system function.

The regulation of transcription in B cells is a highly complex process involving the interplay of broadly expressed and B-cell-specific regulatory proteins (22). Such complexity is illustrated by studies of the octamer-binding proteins Oct-1 and Oct-2 and their role in the regulation of Ig gene transcription. Early studies of Ig gene promoters implicated the octamer element as an important cis-regulatory element involved in the control of Ig gene expression. Identification and characterization of the B-cell-specific octamer-binding protein Oct-2 suggested that this factor was important for expression of the Ig genes (32). More recent studies have implicated the B-cell-specific coactivator OCA-B (also called OBF-1 and Bob1) as an important coregulator of Ig gene transcription in B cells (8, 18, 33). The roles of these B-cell-specific transcription factors in vivo have been elucidated by using gene targeting in the mouse. Although mice lacking Oct-2 die during embryonic development, Oct-2 turns out not to be required for early B-cell development in reconstituted lymphoid systems (2). While OCA-B also is not required for early B-cell development, it is required for proper B-cell maturation and immune response (15, 27). Simultaneous disruption of Oct-2 and OCA-B has surprisingly little effect on early B-cell development and Ig gene expression (28). These studies suggest that the function of Oct-2 in B cells is partially redundant with the function of Oct-1, the more broadly expressed octamer-binding protein. Thus, a tissue-restricted and a ubiquitous transcription factor can have overlapping functions in the immune system.

Here we propose that while TAFII105 may function in the regulation of transcription in B lymphocytes, such a function is likely redundant with that of one or more cellular proteins in mice. A wealth of previous studies implicated TAFII105 in the control of transcription in B cells (4, 24, 31, 39-41). In this study, we have found that expression of TAFII105 is induced in response to bacterial LPS stimulation in B cells. However, in a battery of assays we employed, no significant immune system defect was observed in TAFII105-null mice. We have previously shown that in RNA derived from mouse tissues, expression of TAFII105 is selective, in contrast to the broad expression of the related TAFII130 protein. Perhaps, in similar fashion to Oct-1 and Oct-2, the ubiquitously expressed TAFII130 protein can perform some of the functions of tissue-selective TAFII105 in the immune system. In addition, Dikstein and colleagues have recently described the existence of a TAFII105 paralog in the human genome (31). It is possible that such a paralog, which could substitute for the B-cell function of the TAFII105 gene disrupted in this study, may exist in mice as well. Biochemical and genetic studies documenting the existence of such TAFII105-related paralogs and their in vivo functions will be required to determine whether such related proteins have overlapping functions in B cells. While biochemical and molecular studies have revealed the existence of tissue-specific transcriptional activators and coactivators in B cells, gene targeting experiments in the mouse have revealed the redundant nature of these factors in mammalian organisms. Such is the case for the TAFII105-null mice described here, which have no B-cell defects that our assays have detected. Future mouse studies that disrupt TAFII105 in combination with other TAFII105-related proteins and/or activators will be required to reveal the function of TAFII105 in the immune systems of mammals.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Haggart for expert technical assistance, D. Bhattacharya and L. Liang for helpful instruction with the immunology assays, W. Herr for Gal4 expression plasmids, N. Tanese for the Gal4 reporter plasmid, M. Schlissel for reagents, A. Ladurner for the anti-hTAFII250 antisera, K. Geles, M. Marr, and O. Puig for insightful comments on the manuscript, and J. Lim for manuscript preparation.

R.N.F. is a fellow of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society. This work was supported in part by a grant from the NIH to R.T.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albright, S. R., and R. Tjian. 2000. TAFs revisited: more data reveal new twists and confirm old ideas. Gene 242:1-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corcoran, L. M., M. Karvelas, G. J. Nossal, Z. S. Ye, T. Jacks, and D. Baltimore. 1993. Oct-2, although not required for early B-cell development, is critical for later B-cell maturation and for postnatal survival. Genes Dev. 7:570-582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dantonel, J. C., S. Quintin, L. Lakatos, M. Labouesse, and L. Tora. 2000. TBP-like factor is required for embryonic RNA polymerase II transcription in C. elegans. Mol. Cell 6:715-722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dikstein, R., S. Zhou, and R. Tjian. 1996. Human TAFII 105 is a cell type-specific TFIID subunit related to hTAFII130. Cell 87:137-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freiman, R. N., S. R. Albright, S. Zheng, W. C. Sha, R. E. Hammer, and R. Tjian. 2001. Requirement of tissue-selective TBP-associated factor TAFII105 in ovarian development. Science 293:2084-2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gill, G., E. Pascal, Z. H. Tseng, and R. Tjian. 1994. A glutamine-rich hydrophobic patch in transcription factor Sp1 contacts the dTAFII110 component of the Drosophila TFIID complex and mediates transcriptional activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:192-196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goodrich, J. A., T. Hoey, C. J. Thut, A. Admon, and R. Tjian. 1993. Drosophila TAFII40 interacts with both a VP16 activation domain and the basal transcription factor TFIIB. Cell 75:519-530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gstaiger, M., O. Georgiev, H. van Leeuwen, P. van der Vliet, and W. Schaffner. 1996. The B cell coactivator Bob1 shows DNA sequence-dependent complex formation with Oct-1/Oct-2 factors, leading to differential promoter activation. EMBO J. 15:2781-2790. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hardy, R. R., C. E. Carmack, S. A. Shinton, J. D. Kemp, and K. Hayakawa. 1991. Resolution and characterization of pro-B and pre-pro-B cell stages in normal mouse bone marrow. J. Exp. Med. 173:1213-1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hiller, M. A., T. Y. Lin, C. Wood, and M. T. Fuller. 2001. Developmental regulation of transcription by a tissue-specific TAF homolog. Genes Dev. 15:1021-1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoey, T., R. O. Weinzierl, G. Gill, J. L. Chen, B. D. Dynlacht, and R. Tjian. 1993. Molecular cloning and functional analysis of Drosophila TAF110 reveal properties expected of coactivators. Cell 72:247-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holmes, M. C., and R. Tjian. 2000. Promoter-selective properties of the TBP-related factor TRF1. Science 288:867-870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holstege, F. C., E. G. Jennings, J. J. Wyrick, T. I. Lee, C. J. Hengartner, M. R. Green, T. R. Golub, E. S. Lander, and R. A. Young. 1998. Dissecting the regulatory circuitry of a eukaryotic genome. Cell 95:717-728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaltenbach, L., M. A. Horner, J. H. Rothman, and S. E. Mango. 2000. The TBP-like factor CeTLF is required to activate RNA polymerase II transcription during C. elegans embryogenesis. Mol. Cell 6:705-713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim, U., X. F. Qin, S. Gong, S. Stevens, Y. Luo, M. Nussenzweig, and R. G. Roeder. 1996. The B-cell-specific transcription coactivator OCA-B/OBF-1/Bob-1 is essential for normal production of immunoglobulin isotypes. Nature 383:542-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Komarnitsky, P. B., B. Michel, and S. Buratowski. 1999. TFIID-specific yeast TAF40 is essential for the majority of RNA polymerase II-mediated transcription in vivo. Genes Dev. 13:2484-2489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lemon, B., and R. Tjian. 2000. Orchestrated response: a symphony of transcription factors for gene control. Genes Dev. 14:2551-2569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luo, Y., and R. G. Roeder. 1995. Cloning, functional characterization, and mechanism of action of the B-cell-specific transcriptional coactivator OCA-B. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:4115-4124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martianov, I., G.-M. Fimia, A. Dierich, M. Parvinen, P. Sassone-Corsi, and I. Davidson. 2001. Late arrest of spermiogenesis and germ cell apoptosis in mice lacking the TBP-like TLF/TRF2 gene. Mol. Cell 7:509-515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mengus, G., M. May, L. Carré, P. Chambon, and I. Davidson. 1997. Human TAFII135 potentiates transcriptional activation by the AF-2s of the retinoic acid, vitamin D3, and thyroid hormone receptors in mammalian cells. Genes Dev. 11:1381-1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moqtaderi, Z., M. Keaveney, and K. Struhl. 1998. The histone H3-like TAF is broadly required for transcription in yeast. Mol. Cell 2:675-682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Riordan, M., and R. Grosschedl. 2000. Transcriptional regulation of early B-lymphocyte differentiation. Immunol. Rev. 175:94-103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pugh, B. F., and R. Tjian. 1990. Mechanism of transcriptional activation by Sp1: evidence for coactivators. Cell 61:1187-1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rashevsky-Finkel, A., A. Silkov, and R. Dikstein. 2001. A composite nuclear export signal in the TBP-associated factor TAFII105. J. Biol. Chem. 276:44963-44969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saluja, D., M. F. Vassallo, and N. Tanese. 1998. Distinct subdomains of human TAFII130 are required for interactions with glutamine-rich transcriptional activators. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:5734-5743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanders, S. L., and P. A. Weil. 2000. Identification of two novel TAF subunits of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae TFIID complex. J. Biol. Chem. 275:13895-13900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schubart, D. B., A. Rolink, M. H. Kosco-Vilbois, F. Botteri, and P. Matthias. 1996. B-cell-specific coactivator OBF-1/OCA-B/Bob1 required for immune response and germinal centre formation. Nature 383:538-542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schubart, K., S. Massa, D. Schubart, L. M. Corcoran, A. G. Rolink, and P. Matthias. 2001. B cell development and immunoglobulin gene transcription in the absence of Oct-2 and OBF-1. Nat. Immunol. 2:69-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sekiguchi, T., Y. Nohiro, Y. Nakamura, N. Hisamoto, and T. Nishimoto. 1991. The human CCG1 gene, essential for progression of the G1 phase, encodes a 210-kilodalton nuclear DNA-binding protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11:3317-3325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sha, W. C., H. C. Liou, E. I. Tuomanen, and D. Baltimore. 1995. Targeted disruption of the p50 subunit of NF-κB leads to multifocal defects in immune responses. Cell 80:321-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Silkov, A., O. Wolstein, I. Shachar, and R. Dikstein. 2002. Enhanced apoptosis of B and T lymphocytes in TAFII105 dominant-negative transgenic mice is linked to NF-κB. J. Biol. Chem. 277:17821-17829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Staudt, L. M., R. G. Clerc, H. Singh, J. H. LeBowitz, P. A. Sharp, and D. Baltimore. 1988. Cloning of a lymphoid-specific cDNA encoding a protein binding the regulatory octamer DNA motif. Science 241:577-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Strubin, M., J. W. Newell, and P. Matthias. 1995. OBF-1, a novel B cell-specific coactivator that stimulates immunoglobulin promoter activity through association with octamer-binding proteins. Cell 80:497-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takada, S., J. T. Lis, S. Zhou, and R. Tjian. 2000. A TRF1:BRF complex directs Drosophila RNA polymerase III transcription. Cell 101:459-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tanese, N., B. F. Pugh, and R. Tjian. 1991. Coactivators for a proline-rich activator purified from the multisubunit human TFIID complex. Genes Dev. 5:2212-2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tanese, N., D. Saluja, M. F. Vassallo, J. L. Chen, and A. Admon. 1996. Molecular cloning and analysis of two subunits of the human TFIID complex: hTAFII130 and hTAFII100. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:13611-13616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Veenstra, G. J., D. L. Weeks, and A. P. Wolffe. 2000. Distinct roles for TBP and TBP-like factor in early embryonic gene transcription in Xenopus. Science 290:2312-2315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Verrijzer, C. P., J. L. Chen, K. Yokomori, and R. Tjian. 1995. Binding of TAFs to core elements directs promoter selectivity by RNA polymerase II. Cell 81:1115-1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolstein, O., A. Silkov, M. Revach, and R. Dikstein. 2000. Specific interaction of TAFII105 with OCA-B is involved in activation of octamer-dependent transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 275:16459-16465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamit-Hezi, A., and R. Dikstein. 1998. TAFII105 mediates activation of anti-apoptotic genes by NF-κB. EMBO J. 17:5161-5169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yamit-Hezi, A., S. Nir, O. Wolstein, and R. Dikstein. 2000. Interaction of TAFII105 with selected p65/RelA dimers is associated with activation of subset of NF-κB genes. J. Biol. Chem. 275:18180-18187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang, D., T. L. Penttila, P. L. Morris, M. Teichmann, and R. G. Roeder. 2001. Spermiogenesis deficiency in mice lacking the Trf2 gene. Science 292:1153-1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou, J., J. Zwicker, P. Szymanski, M. Levine, and R. Tjian. 1998. TAFII mutations disrupt Dorsal activation in the Drosophila embryo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:13483-13488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]