Abstract

Objective:

To determine whether routine use of duodenotomy (DUODX) alters cure rate, survival, or development of liver metastases in 143 patients (162 operations) with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (ZES) without MEN1.

Summary Background Data:

DUODX has been shown to increase the detection of duodenal gastrinomas, but it is unknown if it alters rate of cure, liver metastases, or survival. Data from our prospective studies of surgery in ZES allow us to address this issue because DUODX was not performed before 1987, whereas it was routinely done after 1987.

Methods:

All patients with sporadic ZES (non-MEN1) undergoing surgery for possible cure without a prior DUODX from November 1980 to June 2003 were included. Patients had preoperative computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or ultrasound; if unclear, angiography and somatostatin receptor scintigraphy since 1994. At surgery, all had the same standard ZES operation and were assessed immediately postoperatively, at 3 to 6 months, and yearly for cure (fasting gastrin, secretin test. and imaging studies).

Results:

A DUODX was performed in 79 patients (94 operations), and no DUODX was performed in 64 patients (68 operations), with 10 patients having both (no DUODX, then a DUODX later). Gastrinoma was found in 98% with DUODX compared with 76% with no DUODX (P < 0.00001). Duodenal gastrinomas were found more frequently with DUODX (62% vs. 18%; P < 0.00001), whereas pancreatic, lymph node, and other primary gastrinomas occurred similarly. Six of the 10 patients with 2 operations had a duodenal tumor found with DUODX during a second operation that was missed in the first operation without DUODX. Both the immediate postoperative cure rate (65% vs. 44%; P = 0.010) and long-term cure rate at last follow-up (8.8 ± 0.4 years; range, 0.1 to 21.5) (52% vs. 26%; P = 0.0012) were significantly greater with a DUODX than without. In patients without pancreatic tumors or liver metastases at surgery, both the rate of developing liver metastases (6% vs. 9.5%) and the disease-related death rate (0% vs. 2%) were low and not significantly different in patients with or without a DUODX.

Conclusions:

These results demonstrate that routine use of DUODX increases the short-term and long-term cure rate due to the detection of more duodenal gastrinomas. The rate of development of hepatic metastases and/or disease-related mortality in patients without pancreatic tumors is low, and no effect of DUODX on these parameters was seen. Duodenotomy (DUODX) should be routinely performed during all operations for cure of sporadic ZES.

The use of routine duodenotomy in patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (ZES) without MEN1 remains controversial. In 143 patients with sporadic ZES, we show that duodenotomy increases short-term and long-term cure rate and should be routinely performed.

Until the late 1980s, despite rapid improvements in preoperative imaging, the long-term cure rate in patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (ZES) remained relatively low (<25%) in most studies.1–8 With the increasing recognition that duodenal gastrinomas were more frequent than the originally reported value of <15% of all gastrinomas,4,9–11 and that they were frequently small (<1 cm) and missed on preoperative imaging studies,1,4,12–15 it was proposed that DUODX should be included as a routine component of the surgical exploration.14 Our prospective studies1,12,16–19 and those by others14,20 have demonstrated that DUODX can identify small duodenal gastrinomas not localized by other operative methods. These studies15 demonstrate that many duodenal tumors that are detected by DUODX are frequently missed by preoperative localization studies, including portal venous sampling and secretin angiography,1,13,17,21 endoscopic ultrasound,22 intraoperative ultrasonography,19,23,24 and somatostatin receptor scintigraphy.18 Despite the increased ability of DUODX to localize duodenal gastrinomas, its routine use has been debated.1,14,25–27 The principle factor lacking in evaluating the potential value of routine use of DUODX is an assessment of its effect on long-term cure rate, prevention of the development of liver metastases and ultimately on survival. No studies address these issues. Our prospective surgical studies allow us to address these issues because DUODX was not performed before 1987, whereas it was routinely performed after 1987. In this study, we report the results of a prospective assessment of the effect of DUODX on cure rate, development of liver metastases, and survival in 143 patients (DUODX, 79; no DUODX, 64) undergoing 162 explorations.

METHODS

Since 1980 at the National Institutes of Health and 1997 at the University of California San Francisco, all patients with ZES without MEN1 who were involved in our prospective studies of surgical exploration for cure in patients with ZES described previously1,16,17,28,29 were included in this analysis. As of May 2003, 143 patients underwent surgical exploration and were included in this study.

The diagnosis of ZES was based on acid secretory studies, measurement of fasting serum level of gastrin as well as the results of secretin and calcium provocative tests.30 Basal acid output was determined for each patient using methods described previously.31 Doses of oral gastric antisecretory drug were determined as described previously.32

Time from onset of the disease to exploration was determined for all patients.30,33 The time of diagnosis of ZES was the time the diagnosis was first established by appropriate laboratory studies or when a physician established the diagnosis on the basis of clinical presentation.17,34

The localization and the extent of the gastrinoma were evaluated in all patients as described elsewhere,1,18,28,35 by using upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and conventional imaging studies (computed tomography [CT] scan, magnetic resonance imaging [MRI], transabdominal ultrasound, selective abdominal angiography, and bone scanning). Functional localization of the gastrinoma, measuring gastrin gradients, was performed with the use of portal venous sampling (from January 1980 to April 1992) or hepatic venous sampling after the selective intraarterial injection of secretin (January 1988 to present).13,36,37 Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy was performed since 1994 using [111In-DTPA-DPhe1]-octreotide (6 mCi) with whole body, planar, and SPECT views.18,38,39

All patients referred with a diagnosis of possible ZES underwent an evaluation to establish the diagnosis of ZES17,30,34,40 and studies to determine the suitability of surgical exploration for cure.17,30,34,40 These latter studies included tumor localization studies, studies to determine the presence or absence of MEN1,40,41 and studies to determine the presence of other disease that might make surgery contraindicated.

Patients underwent a surgical exploration for possible cure if they did not have diffuse liver metastases, MEN1, or a medical contraindication for surgery.1,16,17,28,29 Before 1987, an extensive search for gastrinoma was performed using palpation, intraoperative ultrasonography,1,23 and an extended Kocher maneuver.16,29 In 1987, additional procedures were added for localizing duodenal gastrinomas.1,12,16,27 These included endoscopic transillumination of the duodenum at surgery27 and the use of a DUODX.1,16,19 At exploration, an extensive search for endocrine tumors was performed.16–18,42 Briefly, palpation was performed first, followed by intraoperative ultrasound with a 10-MHz real-time transducer1,17,23 after the extended Kocher maneuver. Then, since 1987, the endoscopic transillumination of the duodenum was performed,27 and a 3-cm longitudinal DUODX was centered on the anterolateral surface of the descending (second) duodenum to search for duodenal tumors.1,17

Tumors in the pancreatic head were enucleated. Tumors in the pancreatic body and tail were enucleated if possible; otherwise, they were resected. Distal pancreatectomy was not routinely performed and was done only if multiple pancreatic body and/or tail tumors were present that could not be enucleated.17 If multiple pancreatic head tumors were present that could not be enucleated, a Whipple pancreaticoduodenectomy was performed if the patient had given prior consent. A detailed inspection for peripancreatic, periduodenal, or portal lymph nodes was carried out, and these were routinely removed.19,28 A gastrinoma in a lymph node(s) was termed a primary lymph node tumor if the patient was disease-free after resection of a gastrinoma only in a lymph node.28,43 If liver metastases were present and localized, they were wedge-resected with a 1-cm margin, if possible; if this was not possible, they were localized and a segmental resection or lobectomy was performed.44,45

Postoperatively, patients underwent evaluation for disease-free status immediately after surgery (ie, 2 weeks postresection), within 3 to 6 months postresection, and then yearly.16–18,30 Yearly evaluations included conventional imaging studies (CT, ultrasound, MRI, and angiography, if necessary); somatostatin receptor scintigraphy (SRS) since 1994; assessment of disease status (acid secretory studies, fasting gastrin determinations × 3, secretin provocative test); and assessment of endocrine status (parathyroid, pituitary, adrenal function).16–18,30 Disease-free was defined as a normal fasting gastrin level, negative secretin test, and no tumor on imaging studies.16–18,30 Secretin tests were performed with 2 units of secretin (Ferring Laboratories, Suffern, NY) per kilogram of body weight given by intravenous bolus injection after temporarily discontinuing all antisecretory drugs and serum gastrin was measured at a −5, 0, +2, +5, +10, and 20 minutes postinjection.46 An abnormal response was defined as an increase in the serum gastrin postinjection of ≥200 pg/ml above the average preinjection value.

A recurrence was defined as occurring in a patient who was initially disease-free postresection of a gastrinoma but then lost disease-free status on follow-up evaluation by developing an elevated fasting gastrin level (in the presence of pH < 3), an abnormal secretin test, or positive imaging studies.30,47 Patients with recurrent disease or who were not disease-free after the initial operation underwent reoperation if they had imageable disease on conventional localization studies (CT, MRI, ultrasound, angiography) as defined previously.47 After 1987, a DUODX was routinely performed in patients undergoing a reoperation.

The Fisher exact test and the Mann-Whitney U test were used for two-group comparisons. Tests of features of duodenal gastrinomas were adjusted for multiple comparisons. Tests of the strongly correlated localization studies, gastrinoma site distribution, and total outcome rates were not adjusted but would maintain their individual significance at the P < 0.05 level. All continuous variables were reported as mean ± SEM. The probabilities of survival were calculated and plotted according to the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the exact log-rank test.48

RESULTS

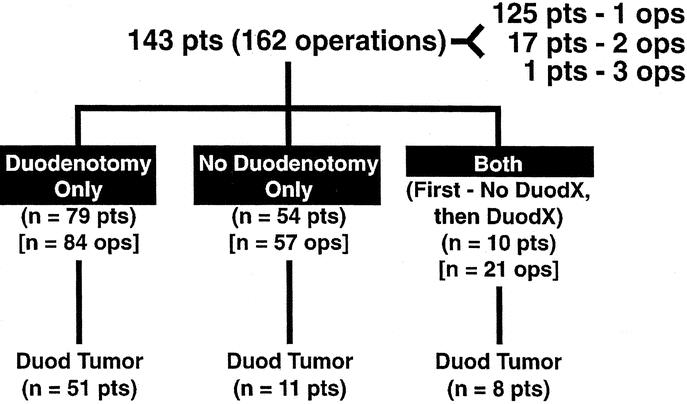

One hundred forty-three patients with sporadic ZES underwent 162 attempted curative resections and were prospectively followed over the 23-year period reported here. Of these, 125 patients had 1 surgical exploration for possible cure, 17 patients had 2, and 1 patient had 3 explorations (Fig. 1). Until 198716,17,29 no patients had a DUODX, which included 64 patients who underwent 68 explorations. After 1987, a routine DUODX was included in the surgical exploration, and 89 patients subsequently underwent 94 surgical explorations with a DUODX (Fig. 1). Ten patients underwent first an exploration without DUODX and later underwent re-exploration with a DUODX (Fig. 1). During these 162 operations, 70 patients (43%) were found to have duodenal gastrinomas (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1. Distribution of patients with sporadic ZES (ie, no MEN1) with or without a DUODX and with or without a duodenal gastrinoma found. The 143 patients underwent 162 surgical explorations for cure with 125, 17, and 1 patient(s) having 1, 2, or 3 explorations. In the 3 groups of patients, 94 DUODXs were performed in 89 patients, and 68 explorations without DUODX (ie, no DUODX) in 64 patients. Seventy patients in the 3 groups had duodenal gastrinomas found.

The 2 different surgical groups of patients with ZES (ie, with or without a DUODX) were similar in clinical and laboratory characteristics (Table 1). Specifically, both had a mean age of 49 years; a slight male predominance; long disease duration of 8 years from onset to surgery, but a short duration from diagnosis to surgery of 1.5 to 2 years; and similar elevations in basal and maximal acid outputs, fasting gastrin levels, and increase in fasting gastrin post secretin (Table 1). In general, these characteristics are similar to other series of patients with ZES without MEN1.4,31,34

TABLE 1. Comparison of Clinical and Laboratory Characteristics in Patients With or Without a Duodenotomy

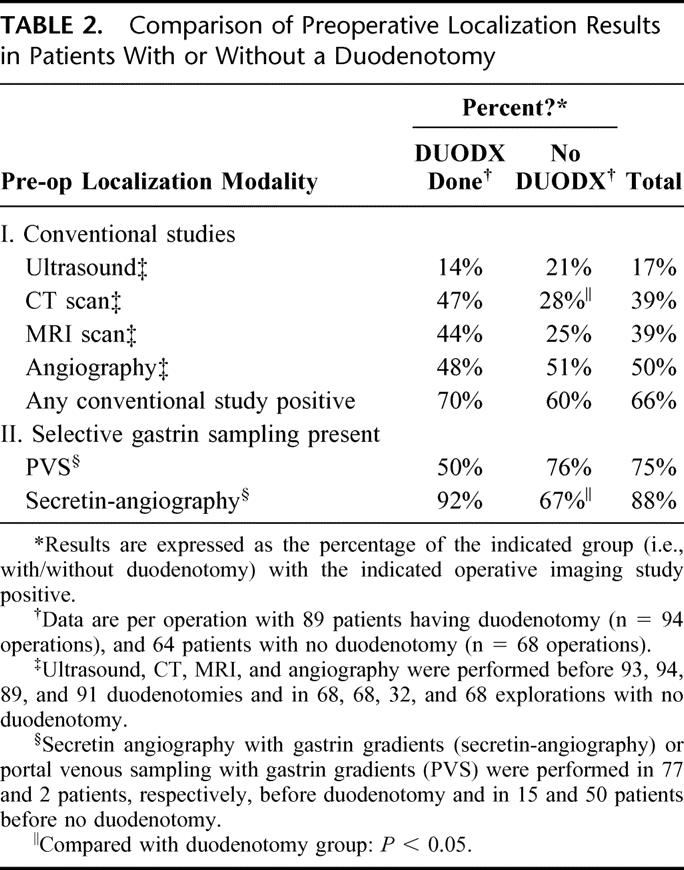

The 2 groups of patients with ZES with or without a DUODX did not differ in the percentage with a positive preoperative conventional imaging study (ie, 70% vs. 60%, respectively) (Table 2). Furthermore, ultrasound was the least sensitive in both groups (14 to 21%), whereas angiography was the most sensitive at detecting a tumor preoperatively (48 to 51%, Table 2). MRI and CT were equally sensitive (39%), and CT scan detected a preoperative lesion more frequently in the DUODX group (Table 2).

TABLE 2. Comparison of Preoperative Localization Results in Patients With or Without a Duodenotomy

Functional localization measuring gastrin gradients was performed using either portal venous sampling (1980 to 1992) or secretin angiography (1988 to present). Because of the later introduction of secretin angiography, it was used primarily in patients before DUODX and portal venous sampling in patients before no DUODX. Secretin angiography more frequently identified a gastrin gradient in the DUODX group of patients (Table 2).

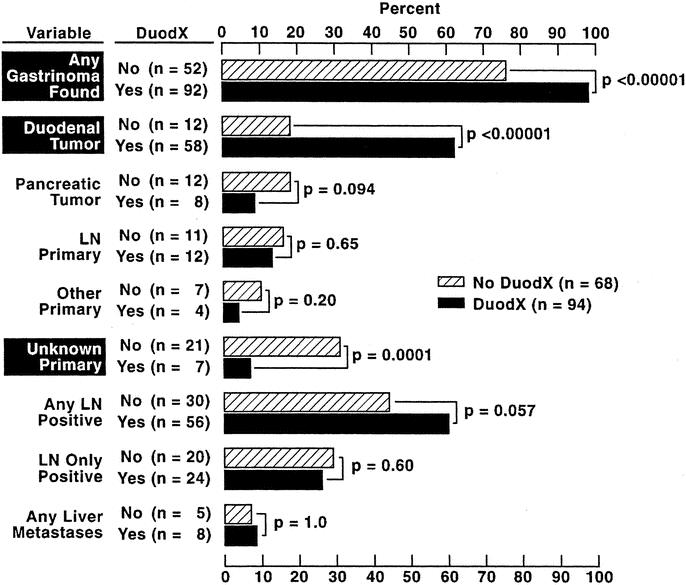

At exploratory laparotomy, a gastrinoma was more frequently found in patients receiving a DUODX (98% vs. 76%, P < 0.0001). This increase was entirely due to increased detection of duodenal gastrinomas with the use of DUODX (62% vs. 18%; P < 0.00001) because the rate of detection of pancreatic primaries (8.5% vs. 18%), lymph node primaries (13% vs. 16%), or primary tumors in other locations (4% vs. 10%) was not significantly different (Fig. 2). Because of the increased detection of duodenal tumors, the percentage of patients with an unknown primary postsurgical exploration was significantly lower in the DUODX group (7% vs. 31%; P = 0.0001). The percentages of patients with or without a DUODX in whom any lymph node metastases were found (60% vs. 44%), only a positive lymph node was found (26% vs. 29%), or liver metastases was found at surgery (8.5% vs. 7%) were not different (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2. Primary tumor location and extent of metastases in patients with or without a DUODX. Data are expressed per operation with 94 DUODXs (89 patients) and 68 no DUODXs (64 patients). “Lymph node (LN) primary” refers to patients with gastrinomas only in LN(s) who were cured postresection as described in Methods. “Other” refers to primary in liver (n = 4), bile duct (n = 1), pylorus (n = 2), jejunum (n = 1), omentum (n = 1), ovary (n = 1), or heart (n = 1). Duod, duodenal; PAN, pancreas; DUODX, duodenotomy.

Duodenal gastrinomas were found in 70 patients (Figs. 1 and 2; Table 3), including 58 patients after a DUODX and 12 patients after no DUODX (Table 3). Ten of the patients who had both surgical procedures first underwent a surgical exploration before 1987 in which no DUODX was performed and no duodenal tumor was found, later undergoing a DUODX. In 6 of the 10 patients undergoing both operations, a duodenal gastrinoma was found with the DUODX, which had been previously missed when no DUODX was performed. Duodenal tumors were generally smaller in size in the group detected by DUODX (0.76 ± 0.05 vs. 1.52 ± 0.4 cm), with 90% of the duodenal tumors being ≤ 1 cm in diameter detected by DUODX compared with 50% after no DUODX (P = 0.0039 before correction for multiplicity). However, the 2 surgical groups did not differ in the mean number of duodenal tumors found (mean = 1 in both groups) or the distribution of the tumors in the duodenum with more than 50% in D1, followed by D2 (17% to 36%), D3 (7% to 17%), and D4 (0% to 3%) (Table 3). The extent of disease also did not differ between the 2 surgical groups, with approximately one half of the patients (47% to 58%) having a primary only in both groups and the remainder a primary with lymph node metastases alone or with liver metastases (5% to 17%). The average number of positive lymph nodes found was slightly greater in patients without a DUODX (2.4 vs. 1.4); however, there was no difference in the size of the largest positive lymph node found in the 2 surgical groups (Table 3).

TABLE 3. Comparison of Features of Duodenal Gastrinomas in Patients With or Without a Duodenotomy

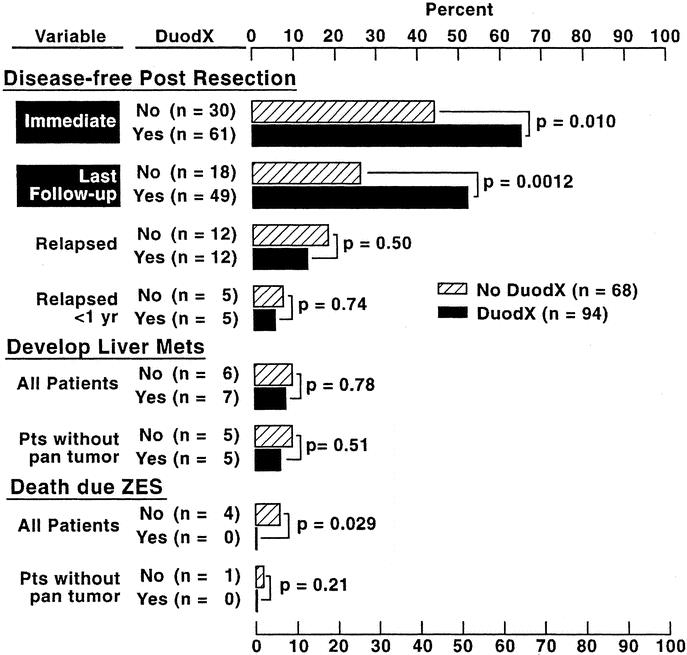

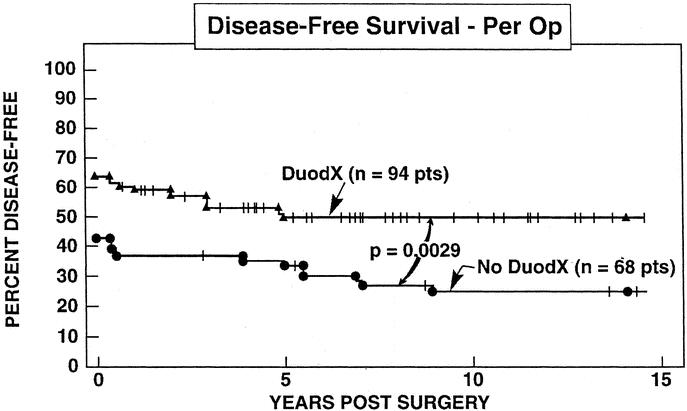

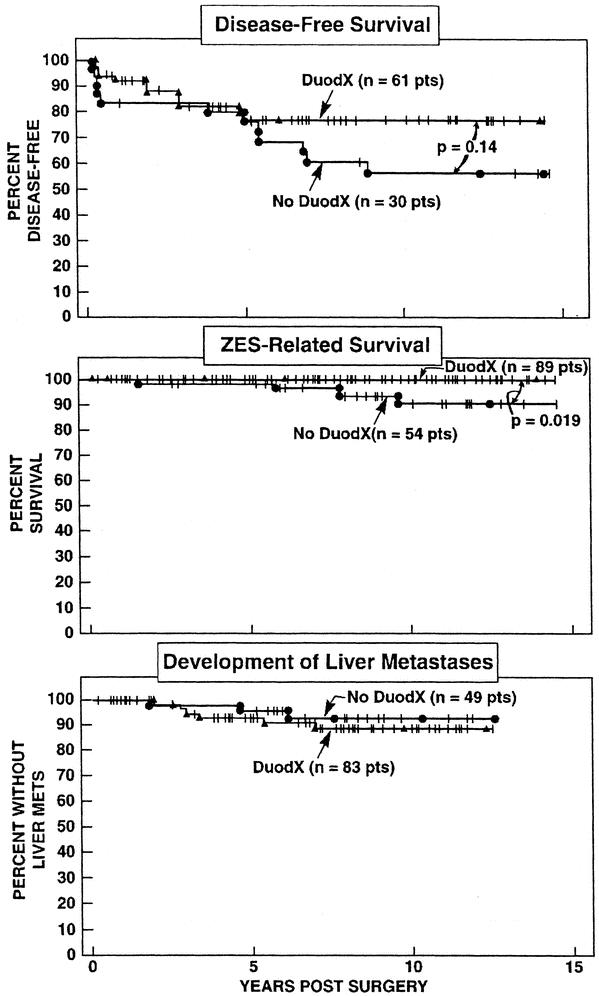

In patients undergoing a DUODX the disease-free rate was significantly higher than patients not undergoing a DUODX, both immediately postoperative (65% vs. 44%; P < 0.010), as well as at the last follow-up evaluation (52% vs. 26%; P = 0.0012), respectively, at a mean of 8.8 ± 0.4 (range, 0.05 to 21.5 years) postresection (Fig. 3). Because the majority of patients without DUODX were operated before 1987 and those with DUODX after 1987, the time from surgery to the last follow-up evaluation differed (10.8 ± 0.7 vs. 7.4 ± 0.4 years). Therefore, the 5- and 10-year postoperative cure rates for each surgical group were calculated from Kaplan-Meier plots, and the cure rates were also significantly better for patients undergoing DUODX (Fig. 4) [DUODX vs. no DUODX: 5 years, 52% (95% CI, 41 to 62%) vs. 35% (25 to 47%); 10 years, 50% (40 to 60%) vs. 25% (16 to 37%); P = 0.0029]. As a proportion of all operations the total relapse rate between the 2 surgical groups did not differ (18% for no DUODX vs. 13% for DUODX; Fig. 3); however, in the Kaplan-Meier plot there was a trend toward the nonDUODX group having a higher relapse rate (P = 0.14) (Fig. 5, top panel). There was no difference in the rate of developing liver metastases in patients without metastases at the time of surgery between the DUODX or no-DUODX groups, whether calculated from the last follow-up (7.4% vs. 9%) or from the Kaplan Meier plot (Fig. 5, bottom panel). The disease-related death rate at last follow-up was higher in patients not undergoing DUODX (5.8% vs. 0%; P = 0.029; Fig. 3) and also reached significance on the Kaplan-Meier plot (91% vs. 100%; P = 0.019; Fig. 5, middle panel). Pancreatic gastrinomas have been shown to have a worse prognosis than duodenal tumors,33,49,50 and 20 patients in the present study had a pancreatic gastrinoma. Therefore, both the rate of development of liver metastases and death rate due to ZES at last follow-up were calculated in the 2 surgical groups in patients with duodenal gastrinomas only, and neither rate differed in the 2 groups (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 3. Postsurgical disease-free status, development of liver metastases, and survival in patients with or without a DUODX. Results are expressed per operation with 94 DUODXs (89 patients) and 68 no DUODXs (64 patients). Immediate is within 2 weeks of surgery. “Relapse” refers to patients who were disease-free immediately postresection and who develop recurrent disease as described in Methods. “All patients” refers to the total having or not having a DUODX, and “without pan tumor” includes all patients without pancreatic primaries (no DUODX, 12; DUODX, 8).

FIGURE 4. Comparison of disease-free survival in all patients with or without a DUODX. Results are expressed for all patients per DUODX (n = 94) or after no DUODX (n = 68). Data are plotted in the form of Kaplan-Meier.

FIGURE 5. Comparison of (top) disease-free survival (per operation), (middle) disease-related survival (per patient), and (bottom) development of liver metastases (per patient) in patients after a DUODX or no DUODX. Results are plotted in the form of Kaplan-Meier. Disease-free survival is plotted as the percentage of the patients disease-free immediately postresection. In the middle and bottom panels, patients who underwent both procedures (n = 10) are counted in the DUODX group. In the bottom panel, only patients without liver metastases at the time of surgery are included.

DISCUSSION

Our prospective surgical study of patients with ZES was analyzed in this report to attempt to address the value of performing routine DUODX for a number of reasons. First, recent studies suggest duodenal gastrinomas are much more frequent than previously reported.4,15,17,25,51 Whereas it was originally reported that duodenal gastrinomas were less than one fifth as frequent as pancreatic tumors,4,9–11 recent studies report they are 3 to 10 times more frequent than pancreatic tumors.4,15,17,25,51 Second, duodenal tumors are frequently small (ie, ≤1 cm) and are not detected by conventional preoperative imaging studies or by routine surgical techniques (palpation, intraoperative ultrasound)1,16–19,23,25,52 and therefore missed at surgery. Third, even newer localization techniques such as somatostatin receptor scintigraphy (SRS) and endoscopic ultrasound frequently miss duodenal tumors and do not allow preoperative localization.1,15,24,25 Lastly, despite improvements in localization methods, the ability to control the acid hypersecretion and increased awareness of the anatomic distribution of gastrinomas, the long-term cure rate for sporadic ZES increased to only 20–30% in most studies.5–8,29,53–55 This had led some to propose routine surgical exploration should not be performed on these patients.55,56 For the above reasons, it was originally proposed by some authors1,14 that routine DUODX be performed in all ZES patients at time of exploration. The risks and benefits of routine DUODX have been debated.1,14,19,26,27 Our previous prospective surgical studies1,16,19 demonstrate that DUODX could locate duodenal gastrinomas not localized by other nonsurgical and surgical methods. However, follow-up in these studies was too short to determine whether DUODX increased cure rate, altered disease-related mortality, or affected the rate of development of hepatic metastases, which is the most important prognostic factor for long-term survival in almost all studies.4,33,49,50 At present there are no reports of a prospective simultaneous comparison of the effect of DUODX on these variables. However, data from our long-term prospective surgical studies allow us to address these questions because DUODX was not routinely performed before 1987, whereas it was after 1987.

A number of our results establish that DUODX increases the disease-free rate and supports the conclusion that it is the result of DUODX detecting duodenal gastrinomas in a greater number of patients. First, both the immediately postoperative disease-free rate as well as the long-term disease-free rate were significantly higher (P < 0.01) in patients undergoing DUODX. The disease-free rate in patients undergoing a DUODX remained above 50% even over a mean follow-up of 7.4 years, whereas the disease-free rate in the patients without a DUODX fell to one half of this during long-term follow-up. Second, this increased long-term disease-free rate with DUODX was almost entirely due to the increased numbers of resected duodenal tumors, as there was an increased immediate disease-free rate in this group and not a difference in relapse rates between patients with or without a DUODX. Although there was a trend (P = 0.14) for disease-free patients post DUODX to have a lower relapse rate with time, this did not reach significance. Third, surgical findings supported the conclusion that the increased disease-free rate was due to finding additional duodenal tumors. With a DUODX the proportion of patients in whom gastrinomas were found increased 20% such that almost every patient (ie, 98%) had a tumor found. This increase was due entirely to a 3-fold increase in the rate of finding duodenal tumors (62% for DUODX vs. 18% for no DUODX), with no significant change in the percentage of patients having a primary in the pancreas, lymph node, or other locations. Furthermore, there was no difference in the percentage of patients having gastrinoma found in lymph nodes. The increased finding of duodenal gastrinomas with DUODX resulted in a highly significant decrease in the number of patients without a primary tumor found compared with patients without a DUODX (7% vs. 31%; P < 0.0001).

Our results provide some insights into why DUODX increases the disease-free rate. Not only were duodenal tumors found in more patients with the use of DUODX, an increased proportion of small duodenal tumors (<1 cm) were found with the use of DUODX. In contrast, no change in the number of duodenal gastrinomas per patient, the distribution of the duodenal gastrinomas or the proportion removed with accompanying lymph node metastases (42 to 53%), was seen between patients with or without a DUODX. Furthermore, this higher proportion of small duodenal tumors found with DUODX was specific for the duodenal tumors because there was no difference in the mean size of the positive lymph nodes found in patients with or without a DUODX. These results suggest that the size of the duodenal gastrinoma rather than its location or multiplicity is one of the primary reasons they are missed when no DUODX is carried out.

It could be argued that other differences that occurred because of the sequential nature of our study, with no DUODXs done before 1987 and patients with DUODXs undergoing surgical exploration after 1987, could be affecting the rate of finding duodenal tumors. A number of our findings are against the hypothesis that other factors than the performance of a DUODX affected outcome. First, the clinical and laboratory characteristics of the 2 surgical groups of patients (ie, with or without DUODX) showed no differences, suggesting that differences in disease severity, duration, or other clinical characteristics were not factors in the differences found. Second, neither surgical group contained patients with MEN1 with ZES, who frequently have multiple duodenal tumors with multiple lymph node metastases17,20,40,57 and are rarely cured; therefore, their inclusion could influence the results. Third, there was no difference in the percentage of patients in the 2 surgical groups who had preoperative localization of a tumor by at least 1 conventional imaging study (ie, ultrasound, CT, MRI, or angiography). Fourth, the percentage of patients who had a positive gastrin gradient was higher in the DUODX group (92% vs. 76%) because of the increased use of secretin angiography rather than portal venous sampling after 1987, which has greater sensitivity.13 This however, is unlikely to be an important factor, because gastrin gradients only give regional localization to a given area (ie, pancreatic head/duodenal area) and do not specifically help identify the tumor as being in the duodenum.36 Fifth, somatostatin receptor scintigraphy was only begun in 1994 at the NIH and, therefore, it was used almost entirely in the DUODX group. However, only 52% of the DUODX patients underwent SRS and more importantly, a recent study18 shows that SRS does not alter the cure rate in patients with gastrinomas. Lastly, it could be argued the difference in follow-up times (DUODX, 7.4 years; no DUODX, 10.8 years) influenced the conclusion. This is not the case because both the immediate postoperative disease-free rate as well as the 5- and 10-year postoperative disease-free rates calculated from Kaplan-Meier plots were significantly higher in patients undergoing a DUODX.

Our study demonstrates no difference in the rate of development of liver metastases in patients with or without a DUODX. A number of studies33,49,58,59 have reported that duodenal gastrinomas are much less aggressive than pancreatic primaries and infrequently develop liver metastases. Our data support this conclusion because only 3% of the patients with duodenal tumors had liver metastases at surgery and during a follow-up period of a mean of 9 years only 10% (4/44 patients) of patients with duodenal tumors who were not cured long-term developed liver metastases. Therefore, with this low rate of aggressive disease, even longer follow-up periods will be needed to assess the effect of DUODX on the development of liver metastases.

For all patients, our data suggested a possible positive effect of DUODX on disease-related survival. Disease-related survival determined from the Kaplan-Meier plot also showed an increased survival in patients after DUODX (10 years, 100% vs. 90%; P = 0.0029). However, when patients with pancreatic tumors were excluded, the disease-related survival was not different in the 2 operative groups. Only longer follow-up times will resolve whether DUODX specifically affects overall survival in patients with only duodenal tumors.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that routine use of DUODX in patients with sporadic ZES increases the immediate and long-term disease-free (cure) rate. Our results are consistent with the conclusion that this increase in disease-free rate is due to increased detection of duodenal gastrinomas at surgery. This increased detection is due to detecting small duodenal gastrinomas, not by detecting more duodenal gastrinomas per patient, or detection of gastrinomas in other duodenal locations. DUODX did not affect the rate of development of liver metastases or disease-related mortality in patients with only duodenal tumors, perhaps because of the nonaggressive growth pattern of most duodenal gastrinomas. These results support the recommendation that DUODX should be routinely performed in patients with sporadic ZES (ie, no MEN1) undergoing surgery.

Discussions

Dr. Jon A. van Heerden (Rochester, Minnesota): Dr. Norton and his colleagues have contributed much over the past 2 and a half decades to the better understanding of the Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. I salute you and your colleagues, Dr. Norton. Prior to 1987, as Dr. Norton said, it was understood by all of us dealing with this disease that this was a pancreatic disease and we erred by exploring many of these patients paying little if any attention to the duodenum—obviously incorrect. So thank you for that lesson. Today a duodenotomy should be routine and should be the gold standard. There is no excuse for not opening the duodenum in all patients being explored for Zollinger-Ellison syndrome regardless of the negativity or positivity of preoperative localizing studies.

Dr. Norton, I have 3 questions for you. These duodenal gastrinomas can be extremely difficult to find. I wonder if you have had any success with endoscopic ultrasonography in locating these tumors? And similarly, could you comment on the mean size of these duodenal gastrinomas? They can be quite small, can't they?

Secondly, what about the complications of the duodenotomy? Have you had any fistulae? Have you had any episodes of pancreatitis? Have you had any duodenal stenosis in particular?

Thirdly, from a practical standpoint, what do you do—and I know this seldom happens as I look at those slides—when you do not find a duodenal gastrinoma? In particular, is that the end of the operation? Or how do you address the lymph nodes?

And lastly, Dr. Norton, in the rare circumstance of Zollinger-Ellison syndrome occurring in the MEN 1 setting, is duodenotomy indicated in those patients as well?

Dr. William L. Holman (Birmingham, Alabama): Dr. Norton, you had a certain failure rate in the patients even after duodenotomy. This was the disease recurrence. When you have one of these patients, what steps do you take and where are you most commonly finding the recurrent gastrinomas?

Dr. Roger R. Perry (Norfolk, Virginia): When you have clearly identified a pancreatic gastrinoma and you do a duodenotomy, how often do you find tumors in the duodenum in that situation?

Dr. Jeffrey A. Norton (Stanford, California): In response to Dr. van Heerden, we have done studies with endoscopic ultrasound, and it hasn't helped our ability to detect duodenal gastrinomas. I think the problem with ultrasound in the duodenum is the mixed background, in that there is solid, liquid, and gas, so that even when the duodenum is distended, the gastrinoma is not visible. And as you mentioned, gastrinomas are very small in size. Ninety percent are less than 1 centimeter and some are 2 to 4 millimeters. So these tumors are very difficult to detect. And when you do a duodenotomy, as you know, the tumor feels like a little BB on your finger.

I think that the complications question is important. The area where we had the most difficulty is the medial wall of the duodenum. It may be difficult to distinguish accessory pancreatic ducts and ampulla from a duodenal tumor from it. We commonly catheterize the common bile duct to help identify it, and we administer secretin IV during surgery to identify an accessory pancreatic duct. The complication rate we have had is very low. We have had no duodenal stenoses because we try to close it in a transverse direction. But occasionally we can't. Even in that setting, it didn't stricture. We did have one woman who had a duodenal fistula and a prolonged septic course, but eventually she completely recovered. If there are no duodenal gastrinomas found, I think that lymph node sampling is critical. During all these operations one should carefully remove as many lymph nodes as possible, because small lymph node metastases occur.

One year ago at this meeting we described lymph node primary gastrinomas. Therefore, we know that these tumors occur 10% of the time. In MEN 1 the gastrinomas are still most commonly within the duodenum, and they are usually multiple. So in those patients it is even more difficult to cure them. We have had a very low cure rate in MEN 1 patients. I think that if they have multiple large tumors one could consider doing a Whipple pancreaticoduodenectomy. In MEN 1 patients this is controversial because the prognosis is good and the long-term survival is excellent.

In response to Dr. Perry's and Dr. Holman's question, the disease recurrence site for duodenal gastrinomas is in lymph nodes. Duodenal tumors do not usually metastasize to the liver. If we miss duodenal tumors and patients develop recurrent disease, it is within lymph nodes. And the confusing aspect is that sometimes you can remove what appears to be a pancreatic tumor and it is actually a lymph node within the pancreas. It has happened to me before. I have removed a tumor within the pancreas and the pathologists say it is really a lymph node. Then we open the duodenum and we find the primary tumor. So it appears that sometimes when we remove a pancreatic tumor, it is really a lymph node within the pancreas. So it is still important to open the duodenum.

Footnotes

Reprints: Jeffrey A. Norton, MD, Stanford University Medical Center, Department of Surgery, Room H-3591, 300 Pasteur Drive, Stanford, CA 94305–5641. E-mail: janorton@stanford.edu

REFERENCES

- 1.Sugg SL, Norton JA, Fraker DL, et al. A prospective study of intraoperative methods to diagnose and resect duodenal gastrinomas. Ann Surg. 1993;218:138–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malagelada JR, Edis AJ, Adson MA, et al. Medical and surgical options in the management of patients with gastrinoma. Gastroenterology. 1983;84:1524–1532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mignon M, Ruszniewski P, Haffar S, et al. Current approach to the management of tumoral process in patients with gastrinoma. World J Surg. 1986;10:703–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jensen RT, Gardner JD. Gastrinoma. In: Go VLW, DiMagno EP, Gardner JD, et al., eds. The Pancreas: Biology, Pathobiology and Disease. New York: Raven; 1993:931–978. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zollinger RM, Ellison EC, Fabri PJ, et al. Primary peptic ulcerations of the jejunum associated with islet cell tumors. Twenty-five-year appraisal. Ann Surg. 1980;192:422–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thompson JC, Lewis BG, Wiener I, et al. The role of surgery in the Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Ann Surg. 1983;197:594–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stabile BE, Morrow DJ, Passaro E Jr. The gastrinoma triangle: operative implications. Am J Surg. 1984;147:25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deveney CW, Deveney KS, Stark D, et al. Resection of gastrinomas. Ann Surg. 1983;198:546–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oberhelman HA Jr, Nelsen TS, Johnson AN, et al. Ulcerogenic tumors of the duodenum. Ann Surg. 1961;153:214–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ellison EH, Wilson SD. The Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: re-appraisal and evaluation of 260 registered cases. Ann Surg. 1964;160:512–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hofmann JW, Fox PS, Wilson SD. Duodenal wall tumors and the Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Surgical management. Arch Surg. 1973;107:334–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Norton JA, Jensen RT. Current surgical management of Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (ZES) in patients without multiple endocrine neoplasia-type 1 (MEN1). Surg Oncol. 2003;12:145–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thom AK, Norton JA, Doppman JL, et al. Prospective study of the use of intraarterial secretin injection and portal venous sampling to localize duodenal gastrinomas. Surgery. 1992;112:1002–1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thompson NW, Vinik AI, Eckhauser FE. Microgastrinomas of the duodenum. A cause of failed operations for the Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Ann Surg. 1989;209:396–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Norton JA, Jensen RT. Resolved and unresolved controversies in the surgical management of patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Ann Surg. 2003 (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Norton JA, Doppman JL, Jensen RT. Curative resection in Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: Results of a 10-year prospective study. Ann Surg. 1992;215:8–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Norton JA, Fraker DL, Alexander HR, et al. Surgery to cure the Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:635–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alexander HR, Fraker DL, Norton JA, et al. Prospective study of somatostatin receptor scintigraphy and its effect on operative outcome in patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Ann Surg. 1998;228:228–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zogakis TG, Gibril F, Libutti SK, et al. Management and outcome of patients with sporadic gastrinomas arising in the duodenum. Ann Surg. 2003;238:42–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thompson NW, Pasieka J, Fukuuchi A. Duodenal gastrinomas, duodenotomy, and duodenal exploration in the surgical management of Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. World J Surg. 1993;17:455–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thom AK, Norton JA, Axiotis CA, et al. Location, incidence and malignant potential of duodenal gastrinomas. Surgery. 1991;110:1086–1093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doppman JL. Pancreatic endocrine tumors–the search goes on [editorial]. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1770–1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Norton JA, Cromack DT, Shawker TH, et al. Intraoperative ultrasonographic localization of islet cell tumors. A prospective comparison to palpation. Ann Surg. 1988;207:160–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruszniewski P, Amouyal P, Amouyal G, et al. Localization of gastrinomas by endoscopic ultrasonography in patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Surgery. 1995;117:629–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cadiot G, Lebtahi R, Sarda L, et al. Preoperative detection of duodenal gastrinomas and peripancreatic lymph nodes by somatostatin receptor scintigraphy. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:845–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Norton JA, Jensen RT. Unresolved surgical issues in the management of patients with the Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. World J Surg. 1991;15:151–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frucht H, Norton JA, London JF, et al. Detection of duodenal gastrinomas by operative endoscopic transillumination: a prospective study. Gastroenterology. 1990;99:1622–1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Norton JA, Alexander HA, Fraker DL, et al. Possible primary lymph node gastrinomas: occurrence, natural history and predictive factors: A prospective study. Ann Surg. 2003;237:650–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Norton JA, Doppman JL, Collen MJ, et al. Prospective study of gastrinoma localization and resection in patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Ann Surg. 1986;204:468–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fishbeyn VA, Norton JA, Benya RV, et al. Assessment and prediction of long-term cure in patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: the best approach. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:199–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roy P, Venzon DJ, Feigenbaum KM, et al. Gastric secretion in Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: correlation with clinical expression, tumor extent and role in diagnosis - A prospective NIH study of 235 patients and review of the literature in 984 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 2001;80:189–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Metz DC, Pisegna JR, Fishbeyn VA, et al. Control of gastric acid hypersecretion in the management of patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. World J Surg. 1993;17:468–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weber HC, Venzon DJ, Lin JT, et al. Determinants of metastatic rate and survival in patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: a prospective long-term study. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:1637–1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roy P, Venzon DJ, Shojamanesh H, et al. Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: clinical presentation in 261 patients. Medicine. 2000;79:379–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Orbuch M, Doppman JL, Strader DB, et al. Imaging for pancreatic endocrine tumor localization: recent advances. In: Mignon M, Jensen RT, eds. Endocrine Tumors of the Pancreas: Recent Advances in Research and Management. Basel, Switzerland: S. Karger; 1995:268–281. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Strader DB, Doppman JL, Orbuch M, et al. Functional localization of pancreatic endocrine tumors. In: Mignon M, Jensen RT, eds. Endocrine Tumors of the Pancreas: Recent Advances in Research and Management. Basel, Switzerland: S Karger; 1995:282–297. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cherner JA, Doppman JL, Norton JA, et al. Selective venous sampling for gastrin to localize gastrinomas. A prospective study. Ann Intern Med. 1986;105:841–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gibril F, Reynolds JC, Doppman JL, et al. Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy: its sensitivity compared with that of other imaging methods in detecting primary and metastatic gastrinomas: a prospective study. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:26–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Termanini B, Gibril F, Reynolds JC, et al. Value of somatostatin receptor scintigraphy: A prospective study in gastrinoma of its effect on clinical management. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:335–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Norton JA, Alexander HR, Fraker DL, et al. Comparison of surgical results in patients with advanced and limited disease with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 and Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Ann Surg. 2001;234:495–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Benya RV, Metz DC, Venzon DJ, et al. Zollinger-Ellison syndrome can be the initial endocrine manifestation in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia-type 1. Am J Med. 1994;97:436–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fraker DL, Norton JA, Alexander HR, et al. Surgery in Zollinger-Ellison syndrome alters the natural history of gastrinoma. Ann Surg. 1994;220:320–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arnold WS, Fraker DL, Alexander HR, et al. Apparent lymph node primary gastrinoma. Surgery. 1994;116:1123–1130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Norton JA, Doherty GD, Fraker DL, et al. Surgical treatment of localized gastrinoma within the liver: a prospective study. Surgery. 1998;124:1145–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Norton JA, Sugarbaker PH, Doppman JL, et al. Aggressive resection of metastatic disease in selected patients with malignant gastrinoma. Ann Surg. 1986;203:352–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Frucht H, Howard JM, Slaff JI, et al. Secretin and calcium provocative tests in the Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: a prospective study. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111:713–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jaskowiak NT, Fraker DL, Alexander HR, et al. Is reoperation for gastrinoma excision in Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (ZES) indicated? Surgery. 1996;120:1057–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yu F, Venzon DJ, Serrano J, et al. Prospective study of the clinical course, prognostic factors and survival in patients with longstanding Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:615–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jensen RT. Natural history of digestive endocrine tumors. In: Mignon M, Colombel JF, eds. Recent Advances in Pathophysiology and Management of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases and Digestive Endocrine Tumors. Paris: John Libbey Eurotext; 1999:192–219. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Norton JA. Neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas and duodenum. Curr Probl Surg. 1994;31:1–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Howard TJ, Zinner MJ, Stabile BE, et al. Gastrinoma excision for cure. A prospective analysis. Ann Surg. 1990;211:9–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wise SR, Johnson J, Sparks J, et al. Gastrinoma: the predictive value of preoperative localization. Surgery. 1989;106:1087–1092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jensen RT. Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. In: Doherty GM, Skogseid B, eds. Surgical Endocrinology: Clinical Syndromes. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001:291–344. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hirschowitz BI. Clinical course of nonsurgically treated Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. In: Mignon M, Jensen RT, eds. Endocrine Tumors of the Pancreas: Recent Advances in Research and Management. Basel, Switzerland: S. Karger; 1995:360–371. [Google Scholar]

- 56.McCarthy DM. The place of surgery in the Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1980;302:1344–1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.MacFarlane MP, Fraker DL, Alexander HR, et al. A prospective study of surgical resection of duodenal and pancreatic gastrinomas in multiple endocrine neoplasia-Type 1. Surgery. 1995;118:973–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stabile BE, Passaro E Jr. Benign and malignant gastrinoma. Am J Surg. 1985;49:144–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Donow C, Pipeleers-Marichal M, Schroder S, et al. Surgical pathology of gastrinoma: site, size, multicentricity, association with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1, and malignancy. Cancer. 1991;68:1329–1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]