Abstract

Objective:

To determine whether vascular endothelial cell apoptosis occurs in the late stage of sepsis and, if so, whether administration of a potent vasodilatory peptide adrenomedullin and its newly reported specific binding protein (AM/AMBP-1) prevents sepsis-induced endothelial cell apoptosis.

Summary Background Data:

Polymicrobial sepsis is characterized by an early, hyperdynamic phase followed by a late, hypodynamic phase. Our recent studies have shown that administration of AM/AMBP-1 delays or even prevents the transition from the hyperdynamic phase to the hypodynamic phase of sepsis, attenuates tissue injury, and decreases sepsis-induced mortality. However, the mechanisms responsible for the beneficial effects of AM/AMBP-1 in sepsis remain unknown.

Methods:

Polymicrobial sepsis was induced by cecal ligation and puncture in adult male rats. Human AMBP-1 (40 μg/kg body weight) was infused intravenously at the beginning of sepsis for 20 minutes and synthetic AM (12 μg/kg body weight) was continuously administered for the entire study period using an Alzert micro-osmotic pump, beginning 3 hours prior to the induction of sepsis. The thoracic aorta and pulmonary tissues were harvested at 20 hours after cecal ligation and puncture (ie, the late stage of sepsis). Apoptosis was determined using TUNEL assay, M30 Cytodeath immunostaining, and electromicroscopy. In addition, anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 and pro-apoptotic Bax gene expression and protein levels were assessed by RT-PCR and Western blot analysis, respectively.

Results:

Vascular endothelial cells underwent apoptosis formation at 20 hours after cecal ligation and puncture as determined by three different methods. Moreover, partial detached endothelial cell in the aorta was observed. Bcl-2 mRNA and protein levels decreased significantly at 20 hours after the onset of sepsis while Bax was not altered. Administration of AM/AMBP-1 early after sepsis, however, significantly reduced the number of apoptotic endothelial cells. This was associated with significantly increased Bcl-2 protein levels and decreased Bax gene expression in the aortic and pulmonary tissues.

Conclusion:

The above results suggest that vascular endothelial cell apoptosis occurs in late sepsis and the anti-apoptotic effects of AM/AMBP-1 appear to be in part responsible for their beneficial effects observed under such conditions.

This study reports that vascular endothelial cell apoptosis occurs in the late, hypodynamic stage of sepsis induced by cecal ligation and puncture in the rat. Administration of adrenomedullin and its newly reported specific binding protein attenuates apoptosis formation, which is associated with the increased Bcl-2 protein and decreased Bax gene expression. Thus, the anti-apoptotic effects of AM/AMBP-1 appear to be in part responsible for their beneficial effects observed in sepsis.

Multiple organ failure remains the major cause of death in the septic patient, and its prognosis is still poor despite advances in the treatment of sepsis.1,2 The vascular endothelial cell (EC) plays an important role in the regulation of tissue perfusion by releasing various vasoactive mediators.3,4 The depression of endothelium-dependent vascular relaxation has been well demonstrated following endotoxic shock5 and sepsis.6 In this context, studies have indicated that EC can undergo apoptosis in response to a variety of stimuli.7–9 Studies using in vitro models have shown bacteria-induced EC apoptosis.10,11 Sylte et al10 reported that Hemophilus somnus, a common cause of pneumonia and vasculitis in cattle, induces apoptosis in bovine EC in vitro. Menzies and Kourteva11 noted that Staphylococcus aureus can be ingested by human umbilical vein EC and causes apoptosis in the infected cells. In addition, EC apoptosis has been reported in regions of atherosclerotic plaques.12 Shed apoptotic membrane particles that are highly procoagulant are found in the blood of patients with acute coronary diseases.12 Although EC is capable of undergoing apoptosis in response to various stimuli under in vitro conditions, the data documenting EC apoptosis in the in vivo models of sepsis are lacking at present.13 The first aim of this study, therefore, was to determine whether or not vascular EC apoptosis occurs in the late stage of polymicrobial sepsis induced by cecal ligation and puncture (CLP). Endothelial cells of the aorta along with anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 and pro-apoptotic protein Bax in aortic and pulmonary tissues were examined.

Our recent data have suggested that inadequate interaction between a potent vasodilatory peptide adrenomedullin (AM) and its novel specific binding protein (AMBP-1) due to the reduction of AMBP-1 may play an important role in the development of the hypodynamic response during the progression of sepsis.14,15 Moreover, administration of AM and AMBP-1 in vivo, in combination but not individually, maintains cardiovascular stability and reduces the mortality in sepsis.16 Since studies have shown that AM inhibits serum starvation-induced apoptosis in human umbilical vein EC cultures,17 we hypothesized that AM/AMBP-1 inhibit sepsis-induced vascular EC apoptosis and this may be partially responsible for the beneficial effect of these compounds in sepsis. Therefore, our second aim of this study was to determine whether in vivo administration of AM/AMBP-1 prevents the formation of vascular EC apoptosis. The effect of AM/AMBP-1 on Bcl-2 and Bax gene expression and protein levels was also determined.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal Model of Polymicrobial Sepsis

Male adult Sprague-Dawley rats (290–300 g), purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA), were used in this study. All surgery was performed using aseptic procedures with the exception of the induction of sepsis by CLP, as previously described.18 Briefly, rats were fasted overnight prior to the induction of sepsis but allowed water ad libitum. The animals were anesthetized with isoflurane inhalation and a 2-cm ventral midline abdominal incision was made. The cecum was then exposed, ligated just distal to the ileocecal valve to avoid intestinal obstruction, and punctured twice with an 18-gauge needle. The punctured cecum was squeezed to expel a small amount of fecal material and then returned to the abdominal cavity. The incision was closed in layers and the animals were resuscitated by 3 mL/100 g body weight normal saline subcutaneously immediately after CLP. Sham-operated animals underwent the same surgical procedure except that the cecum was neither ligated nor punctured. Studies were then conducted at 20 hours after the induction of sepsis or sham operation. Please note that 20 hours after CLP represents the late, hypodynamic phase of sepsis.18 The experiments described here were performed in adherence to the National Institutes of Health guidelines for the use of experimental animals. This project was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of University of Alabama at Birmingham and North Shore-Long Island Jewish Research Institute.

Administration of AM/AMBP-1

The fasted animals were anesthetized with isoflurane inhalation and a 1.0-cm incision was made in the neck. A 200-μL Alzet mini-osmotic pump (Durect, Cupertino, CA) was prefilled with synthetic rat AM solution (20 μg/mL sterile saline) and connected to a silastic catheter (size 0.030′′ I.D., 0.065” O.D., Baxter, McGaw Park, IL). The prefilled pump was then primed in sterile normal saline for 2 hours at 37°C before implantation. The mini-osmotic pump was then implanted subcutaneously in the rat prior to induction of sepsis and the silastic catheter was inserted into the right jugular vein for continuous infusion of AM at a constant rate of 8 μL/hr for 23 hours (total dosage 12 μg/kg body weight). Following the close of the neck incision, CLP was performed 3 hours after the implantation of the pump; 1 mL human AMBP-1 solution (Cortex, Sanleandro, CA) at a dose of 40 μg/kg body weight was then infused via the femoral vein by cannulation with PE-50 tubing and using a Harvard pump (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA) at a rate of 50 μL/min for a period of 20 minutes. Vehicle-treated animals received sterile normal saline instead of AM/AMBP-1. It should be noted that AM at a dose of 12 μg/kg body weight was used since this concentration of AM (in combination with AMBP-1) maintains cardiovascular stability and reduces mortality at the late stage of sepsis.16 The dosage of AMBP-1 used in this study was based on our study in which 2 to 5 × 10−9 M AMBP-1 significantly enhanced AM-induced vascular relaxation.14

Determination of Endothelial Cell Apoptosis: TUNEL Assay

The terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT)-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay was carried out using in situ cell death detection kit (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) in paraffin sections. The aortae and lungs were collected at 20 hours after CLP or sham operation and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and then processed for paraffin embedding and section; 6-μm paraffin sections were dewaxed and rehydrated. Tissue sections were incubated with proteinase K (20 μg/mL in 10 mM Tris HCl, pH 7.4–8.0) for 20 minutes at room temperature and rinsed with 50 mM Tris-buffered saline (TBS), pH 7.6. The slides were then reacted with the mixture of the label and enzyme solution supplied in the kit for 60 minutes at 37°C in dark. After washing with TBS for 3 times, the slides were mounted with Vectashield medium (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA). A Nikon E600 microscope with a fluorescent attachment was used to evaluate the slides. TUNEL-positive cells showed green fluorescent and propidium iodide staining showed red fluorescent on nuclei. The section reacted with the label solution alone served as the negative control.

Determination of Endothelial Cell Apoptosis: M30 Staining

M30 cytoDEATH monoclonal antibody (Roche) was also used for detecting EC apoptosis in the aorta at 20 hours after CLP or sham operation. The antibody M30 cytoDEATH recognizes a specific caspase cleavage site within cytokeratin 18 and cytokeratin 18 is a cytoskeletal protein, which is cleaved by a caspase in the early event of apoptosis.19 The paraffin sections were dewaxed and rehydrated followed by the microwave antigen retrieval procedures. For antigen retrieval, slides were soaked in 20% citric acid buffer, pH 6.0 (Vector Labs) and remain just below boiling for 15 minutes. The slides were cooled in room temperature for 5 minutes and rinsed with TBS. The slides were then incubated in 3% bovine serum albumin for 30 minutes to block the nonspecific binding. The section was then incubated in 1:10 M30 mouse monoclonal antibody for 2 hours at room temperature and reacted with 1:200 rat adsorbed biotinylated antimouse IgG (Vector Labs). Vectastain ABC-AP kit and alkaline phosphatase substrate kit from Vector Labs (Vector Labs) was used to reveal the immunohistochemical reaction. Nonimmunized mouse IgG was substitute primary antibody as negative control.

Determination of Endothelial Cell Apoptosis: Electromicroscopy

At 20 hours after CLP or sham operation, animals were killed and the thoracic aorta was immediately removed and submerged in 2% paraformaldehyde and 2% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4. The aorta was then cut into 1-mm lengths and kept in the fixative at 4°C for 3 hours. After wash with 0.1 M phosphate buffer, the tissue was postfixed for 1.5 hours in 1% OsO4 and dehydrated through a graded series of ethanol alcohol solutions. The tissue was infiltrated, embedded in Epon-Araldite resins (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Fort Washington, PA) and polymerized in 70°C. Ultrathin sections were cut and mounted on formvar and carbon-coated single-slotted grids and stained with 2% uranyl acetate and Reynold's lead citrate before examination under a Philips 300 electron microscope.

Determination of Bcl-2 and Bax Gene Expression

The thoracic aorta was harvested from the animals at 20 hours after CLP or sham operation. Total RNA was extracted by using Tri-reagent (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, OH) as previously described by us.20 Four micrograms of RNA were reverse-transcribed as previously described. The resulting cDNAs were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using specific primers for rat Bcl-2 (forward CAAGCCGGGAGAACAGGGTA; reverse CCCACCGAACTCAAAGAAGGC) and rat Bax (forward CCGAGAGGTCTTCTTCCGTGTG; reverse GCCTCAGCCCATCTTCTTCCA). For Bcl-2, the PCR reaction was conducted at 30 cycles for the aorta and 35 cycles for the lungs. Each cycle consisted of 30 seconds at 95°C, 45 seconds at 61°C, and 30 seconds at 72°C. For Bax, the PCR reaction was conducted at 32 cycles for the aorta and 33 cycles for the lungs. Each cycle consisted of 30 seconds at 95°C, 40 seconds at 57°C, and 25 seconds at 72°C. Rat glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (G3PDH) served as a housekeeping gene (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA). The PCR reaction for G3PDH was conducted at 30 cycles for the aorta and 25 cycles for the lungs. Each cycle consisted of 4 minutes at 95°C, 2 minutes at 60°C, and 3 minutes at 72°C. We chose the above cycles based on our preliminary experiments in which increments of 5 cycles were performed prior to choosing the parameters of the PCR experiments. The amplification reaction had not plateaued with those cycles. Following RT-PCR procedure, reaction products were electrophoresed in 1.6% TBE-agarose gel containing 0.22 μg/mL ethidium bromide. The gel was then photographed on Polaroid film and a digital image system was used to determine the band density.

Determination of Protein Levels of Bcl-2 and Bax

Samples of the thoracic aorta from the animals at 20 hours after CLP with or without AM/AMBP treatment or sham-operated animal were homogenized in a lysis buffer, which contains 10 mM Tris saline, pH 7.5 with 1% Triton-100X, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 2 mM Na orthovanadate, 0.2 mM PMSF, 2 μg/mL leupeptin, and 2 μg/mL aprotinin. After centrifugation at 16,000g for 10 minutes, the supernatant was collected and the protein concentration was determined by using Bio-Red DC Protein Assay kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). For Bcl-2, 75 μg protein was loaded on 4% to 12% Bis-Tris gel (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and electrophoretically fractionated in MES SDS running buffer (Invitrogen). The protein on the gel was then transferred to a 0.2-μm nitrocellulose membrane, and blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in 10 mM Tries saline with 0.1% Teen 20, pH 7.6 (TBST). The membrane was incubated with mouse anti-Bcl-2 monoclonal antibody (Oncogene, Boston, MA; 1:100 for the aorta; 1:200 for the lungs) overnight at 4°C, followed by incubation in 1:20,000 HRP-linked antimouse IgG for 1 hour at room temperature. To reveal the reaction bands, the membrane was reacted with ECL Western blot detection system (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ) and exposed on x-ray film. A digital image system was used to determine the density of the bands (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA). The same procedures was used to determine the Bax levels in aortic and pulmonary tissues except that 100 μg protein was loaded on the Bis-Tris gel and 1:200 mouse anti-Bax monoclonal antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) was applied.

Statistical Analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± SE and compared by one-way ANOVA and Tukey's test or Student-Newman-Keuls test. Differences in values were considered significant if P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Effects of AM/AMBP-1 on Endothelial Cell Apoptosis in Sepsis

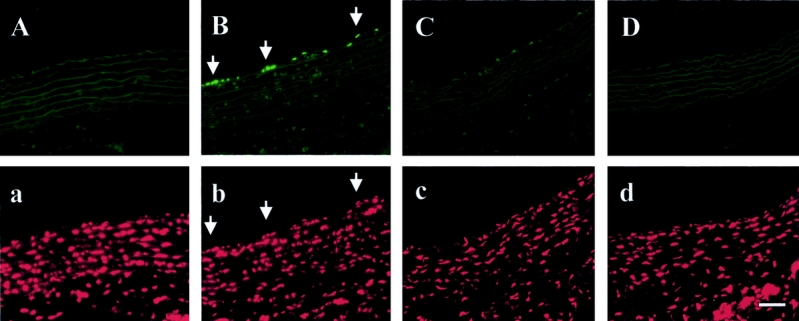

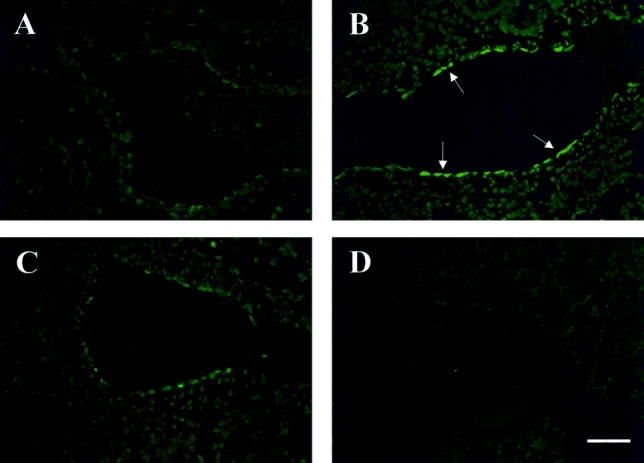

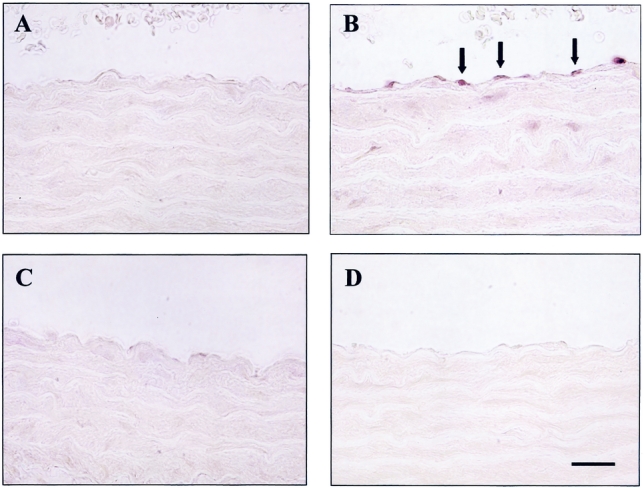

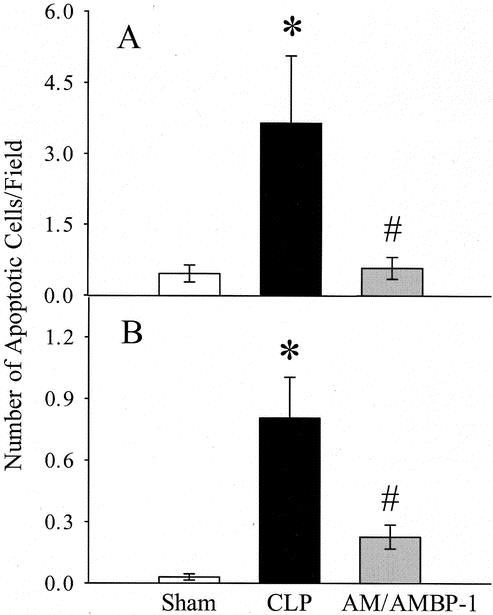

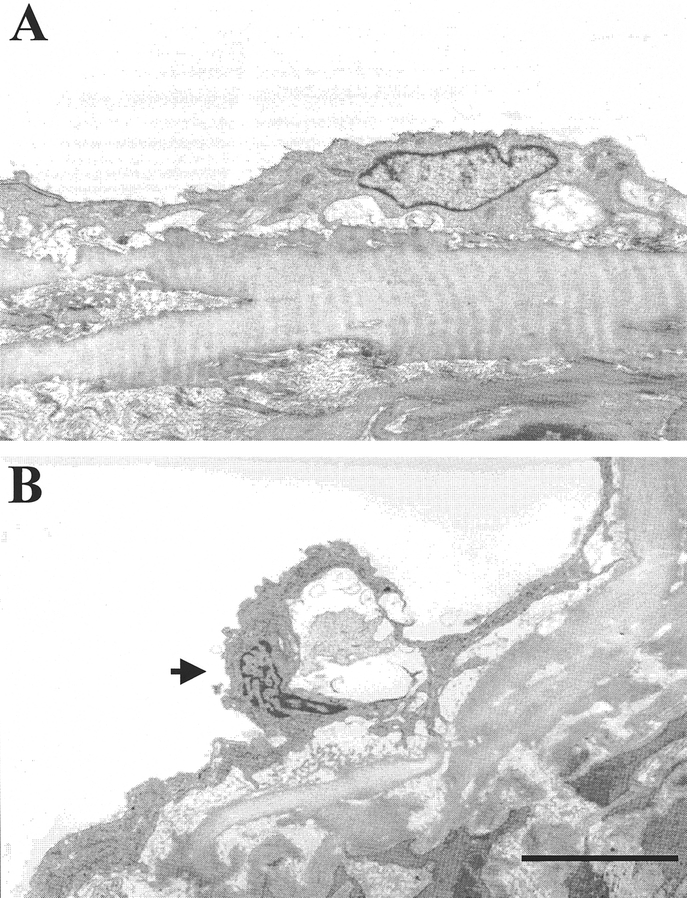

Endothelial cell apoptosis was determined by TUNEL assay, M30 immunohistochemistry, and electromicroscopy examination. As indicated in Figure 1A, almost no TUNEL-positive EC in the aortic section was observed in sham-operated animals. However, the number of TUNEL-positive cells was markedly increased in animals 20 hours after CLP (Fig. 1B). AM/AMBP-1 treatment significantly reduced TUNEL-positive EC in septic animals (Fig. 1C). Similarly, the increased TUNEL-positive EC in the pulmonary microvasculature in septic animals (Fig. 2B) was reduced following administration of AM/AMBP-1 (Fig. 2C). By using M30 cytoDEATH antibody, we have also shown that there was almost no M30-positive EC in the aortic section in sham-operated animals (Fig. 3A). However, M30-positive cells were significantly increased at 20 hours after CLP (Fig. 3B). Administration of AM/AMBP-1 in septic animals attenuated caspase cleavage of cytokeratin 18 in vascular EC at 20 hours after CLP (Fig. 3C). As shown in Figure 4, the number of apoptotic EC per high power field increased significantly in the aorta at 20 hours after the onset of sepsis as determined by TUNEL assay and M30 staining. Administration of AM/AMBP-1, however, reduced apoptotic EC by 84% and 72%, respectively (P < 0.05, Fig. 4A, B). To further confirm the occurrence of apoptosis in aortic EC, electron-microscopic examination was applied. The condensation and margination of chromatin to the nuclear periphery were observed in aortic EC at 20 hours after CLP (Fig. 5B). In addition, the endothelium was partially detached from the basal membrane (Fig. 5B). By using three different measures, ie, TUNEL assay, M30 staining, and electromicroscopy, we have clearly demonstrated that aortic EC undergoes apoptosis at 20 hours after CLP (ie, the late stage of sepsis). Although we did not use electron-microscopic technique to determine the effect of AM/AMBP-1 on vascular EC apoptosis formation, our results have clearly indicated that these compounds significantly reduced EC apoptosis in the aorta at 20 hours after the onset of sepsis by using TUNEL assay and M30 staining.

FIGURE 1. TUNEL staining in aortic tissues at 20 hours after CLP or sham operation with or without AM/AMBP-1 treatment. The vascular endothelial cell apoptosis was observed after CLP (B, arrows) as compared with sham-operated animals (A). AM/AMBP-1 treatment attenuated endothelial cell apoptosis under such conditions (C). A: Sham 20 hours. B: CLP 20 hours. C: CLP 20 hours with AM/AMBP-1 treatment. D: Negative control. a, b, c, and d: same area as A, B, C, and D, respectively. The aortic tissues were stained with propidium iodide (PI) showing nuclei. Bar = 50 μm.

FIGURE 2. TUNEL staining in pulmonary tissues at 20 hours after CLP or sham operation with or without AM/AMBP-1 treatment. The microvascular endothelial cell apoptosis was observed after CLP (B, arrows) as compared with sham-operated animals (A). AM/AMBP-1 treatment attenuated endothelial cell apoptosis (C). A: Sham 20 hours. B: CLP 20 hours. C: CLP 20 hours with AM/AMBP-1 treatment. D: Negative control. Bar = 50 μm.

FIGURE 3. M30 immunohistochemical staining in aortic tissues at 20 hours after CLP or sham operation with or without AM/AMBP-1 treatment. The vascular endothelial cell apoptosis was observed after CLP (B, arrows). AM/AMBP-1 treatment attenuated endothelial cell apoptosis under such conditions (C). A: Sham 20 hours. B: CLP 20 hours. C: CLP 20 hours with AM/AMBP-1 treatment. D: Negative control. Bar = 50 μm.

FIGURE 4. Effects of AM/AMBP-1 on endothelial cells apoptosis in aortic tissues at 20 hours after CLP as determined by TUNEL assay (A) and M30 staining (B). The data are expressed as the number of apoptotic cells per high power field of 5 animals in each group. Eight to 10 high power fields were randomly taken from each slide and then averaged. Values are presented as mean ± SE and compared by one-way ANOVA and Tukey's test: *P < 0.05 versus sham; #P < 0.05 versus CLP.

FIGURE 5. Representative electron-microscopy photographs of aortic tissues at 20 hours after CLP or sham operation (n = 3 or 4 rats/group). The condensed chromosome can be observed in the endothelial cell at 20 hours after CLP (B, arrow). Moreover, the endothelial cell was partially detached from the basal membrane. A: Sham 20 hours; B: CLP 20 hours. Bar = 2 μm.

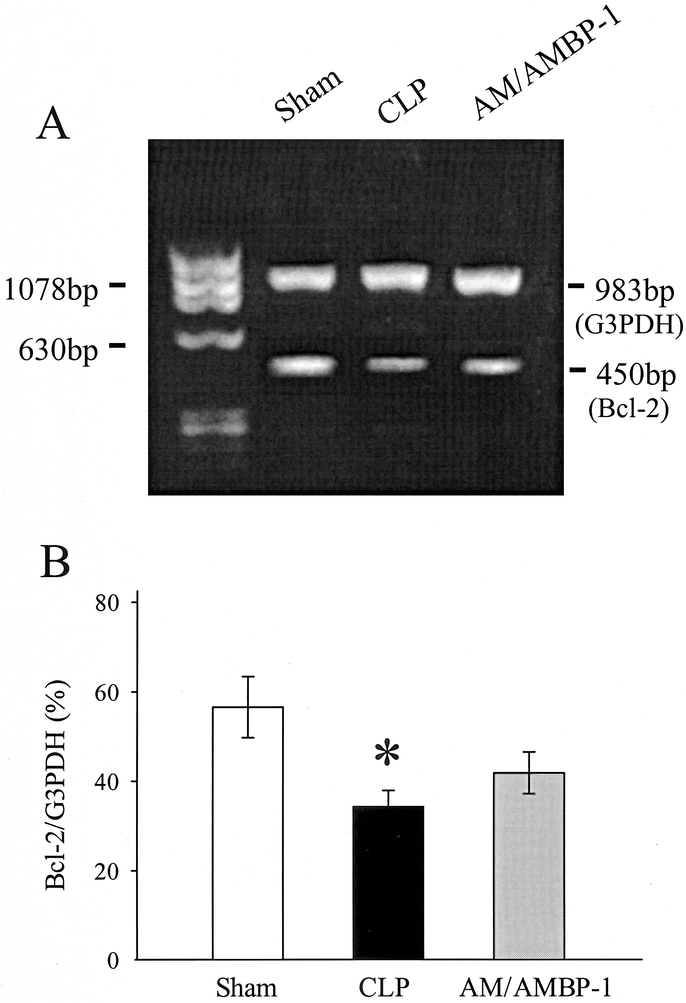

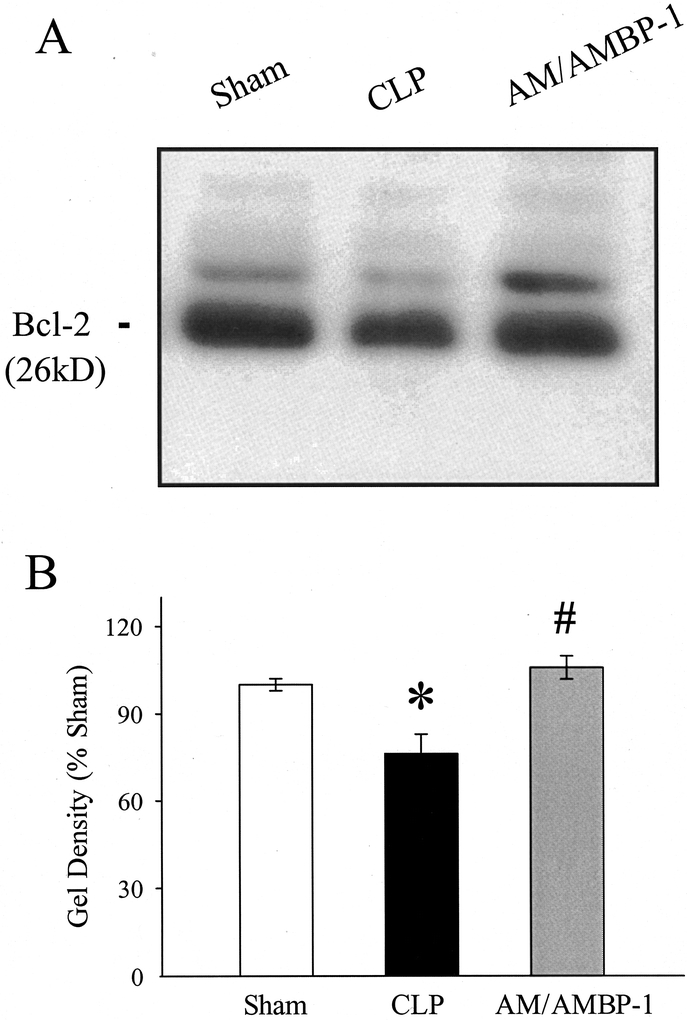

Effects of AM/AMBP-1 on Bcl-2 in Sepsis

Anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 gene expression and protein levels were determined in aortic tissues by RT-PCR and Western blot analysis. As shown in Figure 6A and B,, Bcl-2 gene expression was significantly reduced (by 39%, P < 0.05) at 20 hours after CLP as compared with sham-operated animals in the aorta. Although administration of AM/AMBP-1 in septic animals increased Bcl-2 mRNA by 22%, such an increase was not statistically different (Fig. 6B). As indicated in Figure 7, Bcl-2 protein levels in the aorta decreased significantly in septic animals which were prevented by AM/AMBP treatment.

FIGURE 6. Gene expression of Bcl-2 and the housekeeping gene G3PDH in aortic tissues at 20 hours after CLP or sham operation with or without AM/AMBP-1 treatment. The representative PCR gel (A) and the ratio of Bcl-2/G3PDH (B) are presented. Values (n = 4−6/group) are presented as mean ± SE and compared by one-way ANOVA and Student-Newman-Keuls test: *P < 0.05 versus sham; #P < 0.05 versus CLP 20 hours.

FIGURE 7. Alteration in Bcl-2 protein levels in aortic tissues at 20 hours after CLP or sham operation with or without AM/AMBP-1 treatment. The representative Western blot (A) and the optical densities as a percentage of sham (B) are presented. Values (n = 4−6/group) are presented as mean ± SE and compared by one-way ANOVA and Tukey's test: *P < 0.05 versus sham; #P < 0.05 versus CLP 20 hours.

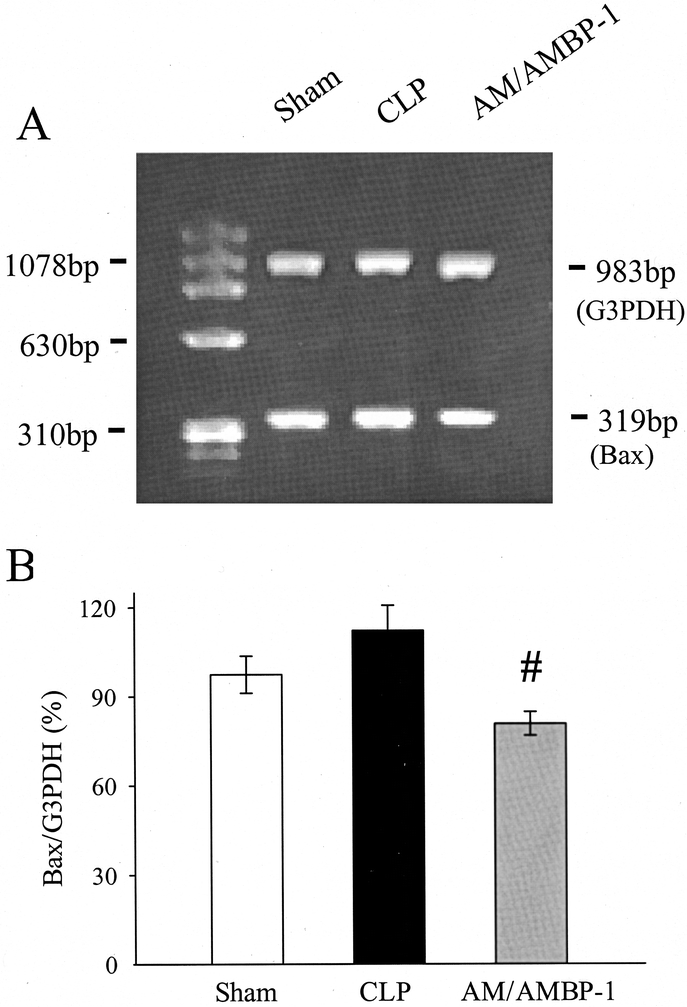

Effects of AM/AMBP-1 on Bax in Sepsis

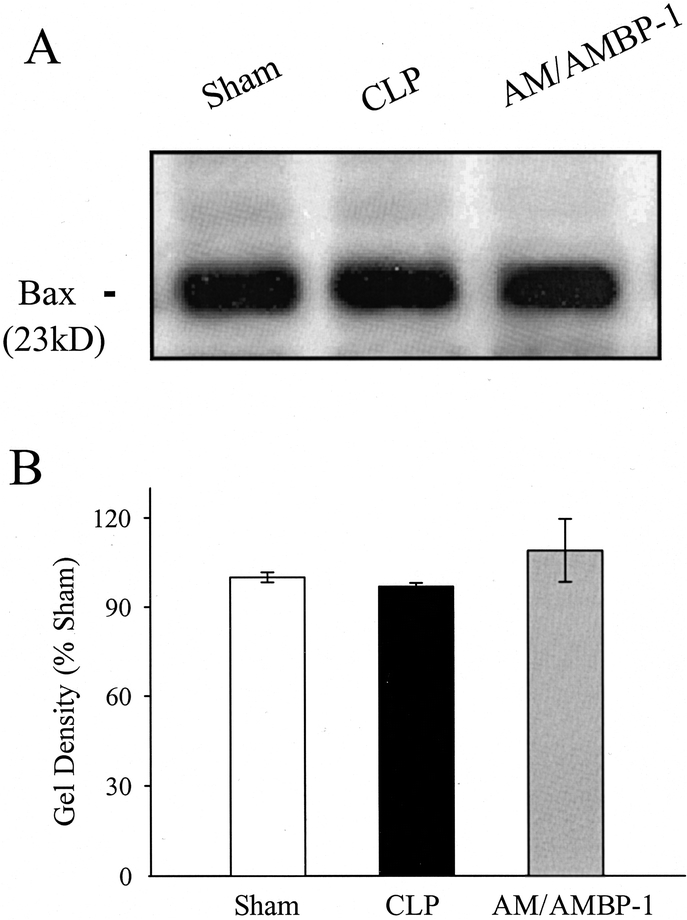

Although the gene expression of the pro-apoptotic protein Bax was not significantly altered at 20 hours after the onset of sepsis, Bax mRNA decreased by 28% in the aortic tissue following administration of AM/AMBP-1 (P < 0.05; Fig. 8). In contrast to Bcl-2, Bax protein levels in the aorta were not significantly altered at 20 hours after CLP, irrespective of AM/AMBP-1 treatment (Fig. 9).

FIGURE 8. Gene expression of Bax and the housekeeping gene G3PDH in aortic tissues at 20 hours after CLP or sham operation with or without AM/AMBP-1 treatment. The representative PCR gel (A) and the ratio of Bax/G3PDH (B) are presented. Values (n = 4−6/group) are presented as mean ± SE and compared by one-way ANOVA and Student-Newman-Keuls test: #P < 0.05 versus CLP 20 hours.

FIGURE 9. Alteration in Bax protein levels in aortic tissues at 20 hours after CLP or sham operation with or without AM/AMBP-1 treatment. The representative Western blot (A) and the optical densities as a percentage of sham (B) are presented. Values (n = 4−6/group) are presented as mean ± SE.

DISCUSSION

Alterations in EC function at macro and microcirculatory levels play an important role in the development of multiple organ failure in sepsis.4,13,21 Studies have shown that EC can undergo apoptosis under various physiologic and pathologic conditions such as angiogenesis, aging, serum or growth factor withdrawal, Fas activation, and radiation injury.7,8,12,22 Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) has been shown to induce EC apoptosis both in vivo and in vitro.23,24 LPS also directly induces EC activation of caspases in the absence of endogenous mediators derived from non-EC sources such as TNF-α.25 Although EC apoptosis was primarily reported under in vitro conditions, endotoxin from Salmonella typhimurium induced disseminated EC apoptosis in a process mediated via ceramide generation in an in vivo mouse model.24 However, the role of EC apoptosis in polymicrobial sepsis still remains inconclusive.

Hotchkiss et al have examined the effect of sepsis on EC apoptosis by electron-microscopy technique.13 They did not find significant evidence of EC apoptosis in septic animals. Since only discrete focal regions were examined, it is possible that EC apoptosis was present in other areas of the vessel that were not examined.13 Some limitations make the investigation of EC apoptosis under in vivo condition difficult. In addition to the limitation of electromicroscopy technique, vascular ECs that are undergoing apoptosis may detach from the base membrane and enter the circulation. In this regard, shed apoptotic EC membrane particles that are highly procoagulant are found in the blood of patients with acute coronary events.12 A clinical study indicates that patients with sickle-cell anemia presented significantly more circulating ECs than the normal donors.26 Our preliminary result also showed that increased number of circulating ECs could be seen in the blood from the animals at late stage of sepsis by EC specific VE-cadherin immunohistochemistry staining (unpublished data). In addition, our current electromicroscopy examination has shown the partially detached EC in the late stage of sepsis (Fig. 5B). These evidences strongly support that ECs could detach from the base membrane in sepsis, which may make the detection of EC apoptosis difficult and the results inconsistent under in vivo conditions. Despite those difficulties, we have demonstrated that EC undergoes apoptosis at the late stage of polymicrobial sepsis by using TUNEL assay, M30 immunohistochemistry, and electron-microscopy technique. This is associated with significant reduction in anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 mRNA and protein levels in aortic tissues. Since we have previously shown that vascular EC function is depressed in sepsis,6 it is possible that EC apoptosis may play an important role in producing vascular EC dysfunction during the progression of sepsis. Although our data have clearly demonstrated that vascular EC apoptosis occurs at the late, hypodynamic stage of polymicrobial sepsis, further studies are needed to determine how early vascular endothelial cells apoptosis occurs after the onset of sepsis. Alternatively, it is important to determine whether circulating endothelial cells are increased at the early, hyperdynamic stage of sepsis.

Vascular ECs, which line the vasculature, are the first host tissue barrier met by circulating LPS, TNF-α, and other proinflammatory molecules under various disease conditions. LPS causes actin reorganization,27 monolayer barrier dysfunction,28 and cell detachment from the underlying extracellular matrix.29 LPS-induced caspase activation cleaves adherens junction proteins and leads the EC apoptosis.28 Disruption of cytoskeletal microfilaments can induce both cell rounding and apoptosis.19,30 During the progression of sepsis, circulating levels of LPS and TNF-α are significantly elevated,31 which could induce the above damage on the cytoskeleton filaments in EC. By using M30 immunohistochemistry staining, our data show that caspase-cleaved cytokeratin 18 was increased in sepsis, which is the evidence of the disruption of the cytoskeleton filaments. In addition, EC detachment from the base membrane in late sepsis was observed by electromicroscopy examination. The detachment process also involves with actin reorganization and disassociation.28 Our results have shown that Bcl-2 levels and its gene expression decreased in the aorta in sepsis, while pro-apoptotic protein Bax levels did not change. Therefore, the ratio of Bcl-2/Bax decreased at the late stage of sepsis. It is possible that the increased circulating levels of TNF-α, LPS, and other proinflammatory mediators down-regulate Bcl-2 expression and subsequently induce EC apoptosis.

Human AM is a 52-amino acid peptide belonging to the calcitonin gene-related peptide family, which participates in the control of vascular tone regulation or fluid and electrolyte homeostasis.32 It has been reported that transgenic mice overexpressing AM in vasculatures are resistant to LPS-induced shock.33 Moreover, mice with disrupted AM gene have displayed an extreme hydrops fetalis and cardiovascular abnormalities, suggesting a central role of AM in the regulation of the cardiovascular system, especially EC function.34 A recent report indicates that AM reduces endothelial hyperpermeability via protecting cytoskeleton filaments.3 AM is up-regulated in sepsis20 as well as other pathophysiologic conditions, such as systemic inflammatory response syndrome35 and endotoxic shock.36 The increased AM plays an important role in initiating the hyperdynamic response in the early stage of sepsis.37 Moreover, the reduced vascular responsiveness to AM appears to be responsible for the transition from the early, hyperdynamic phase to late, hypodynamic phase of sepsis.38 In this regard, a novel specific AM-binding protein, AMBP-1, has been recently identified.39 AMBP-1 can significantly enhance AM biologic action.39 Although incubation with AM alone inhibited TNF-α release from macrophages and Kupffer cells, AMBP-1 significantly potentiates its down-regulatory effects on the production of this proinflammatory cytokine.40 Studies have indicated that the vascular level of AMBP-1 is reduced at 20 hours after CLP (ie, late sepsis),14 and our preliminary data also showed that plasma AMBP-1 binding capacity was also decreased under such conditions. Although our recent studies have shown that administration of AM/AMBP-1 maintains cardiovascular stability and reduces the mortality rate in late sepsis,16 the precise mechanism responsible for the beneficial effect of those compounds remains unknown. Since studies have indicated that AM can act as an apoptosis survival factor for cultured rat and human endothelial cells,17,41,42 we hypothesized that the beneficial effects of AM/AMBP-1 observed in sepsis may be partially due to the prevention of EC apoptosis.

Our results clearly indicate that AM/AMBP-1 administration reduced vascular EC apoptosis as determined by TUNEL assay and M30 staining, which was associated with the significantly improved Bcl-2 protein levels and reduced Bax gene expression. The beneficial effect of AM/AMBP-1 is probably through their actions on protection of the cytoskeleton filaments from disruption, which may relate with down-regulation of TNF-α production. In this regard, our recent studies have indicated that incubation with AM/AMBP-1 significantly suppressed endotoxin-induced TNF-α gene expression and its release from murine macrophage-like cell line RAW 264.7 cells and isolated rat Kupffer cells.40 Moreover, in vivo administration of AM/AMBP-1 markedly reduced circulating levels of proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-1β, at 20 hours after the onset of sepsis.43 This result would suggest that the down-regulatory effect of AM/AMBP-1 on proinflammatory cytokines may be responsible for the beneficial effect of these compounds on vascular EC apoptosis in sepsis.

It should be noted that the sham-operated animals did not receive AM/AMBP-1 treatment in this study. This was done because the results presented in Figures 1 to 3 do not suggest any significant endothelial cell apoptosis formation under sham conditions. In this regard, Tokudome et al have recently demonstrated that while AM reduced doxorubicin-induced cultured rat cardiac myocyte apoptosis, AM per se did not have any effects on apoptotic index in the cultured cells without the addition of doxorubicin.44 In addition, AM did not affect LDH release and caspase-3 activity without doxorubicin stimulation.44 Based on this observation, it is unlikely that administration of AM/AMBP-1 in sham-operated animals would significantly affect endothelial cell apoptosis. Since AM is a potent vasodilator, it could be argued that the beneficial effect of AM/AMBP-1 in sepsis could be due to the vasodilating effect of these compounds. This does not appear to be the case since studies have demonstrated that other vasodilators such as dopamine, papaverine, and adenosine did not have any protective effects on organ function following ischemia and reperfusion injury.45–47 The observation that AM reduces apoptosis in cultured cells and prevents reduction of cell viability in cultured human endothelial cells43,48 would suggest that this compound has anti-apoptotic property.

It should also be pointed out that our study has clearly shown a correlation between the decreased endothelial cell apoptosis and the beneficial effect of AM/AMBP-1 in sepsis. However, a clear cause-and-effect relationship has not been established. It could be argued that the attenuation of EC apoptosis by AM/AMBP-1 in septic animals is the result (not the cause) of the improved hemodynamic responses induced by these compounds. This, however, may not be the case since studies have convincingly demonstrated that AM reduces apoptosis in cultured HUVECs and cultured rat cardiac myocytes.17,44 In this regard, our preliminary result has indicated that AM/AMBP-1 prevents the reduction in cell viability induced by TNF-α in cultured HUVECs. This observation along with our present study would suggest that the anti-apoptotic effect of AM/AMBP-1 may be in part responsible for their beneficial effects in sepsis. In addition to the anti-apoptotic property, AM/AMBP-1 has been shown to down-regulate proinflammatory cytokines and up-regulate endothelial constitutive nitric oxide synthase in sepsis.43,48 We think that these effects, taken together, are responsible for the beneficial effect of AM/AMBP-1 in sepsis.

CONCLUSION

Our results indicate that vascular EC apoptosis occurred at the late stage of polymicrobial sepsis as determined by TUNEL assay, M30 staining and electromicroscopy. The occurrence of EC apoptosis was associated with the down-regulated Bcl-2 gene expression and reduced protein levels of this anti-apoptotic factor. Early administration of AM/AMBP-1, however, significantly reduced apoptotic ECs, increased Bcl-2 protein levels and decreased Bax gene expression. Since we have previously shown that administration of AM/AMBP-1 in sepsis is protective, it appears that their anti-apoptotic effects in vascular ECs may be partially responsible for the beneficial effects of AM/AMBP-1 observed in sepsis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Shaolong Yang, MD and Dale E. Fowler, MD, for their excellent assistance in conducting this project.

Footnotes

Part of this study was performed while Drs. Zhou and Wang were at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL.

Supported by NIH Grant no. R01 GMO-57468 (P.W.).

Reprints: Ping Wang, MD, Division of Surgical Research, North Shore-Long Island Jewish Research Institute, 350 Community Drive, Manhasset, NY 11030. E-mail: pwang@nshs.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hotchkiss RS, Karl IE. The pathophysiology and treatment of sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:138–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baue AE. Multiple organ failure, multiple organ dysfunction syndrome, and systemic inflammatory response syndrome: why no magic bullets? Arch Surg. 1997;132:703–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hippenstiel S, Witzenrath M, Schmeck B, et al. Adrenomedullin reduces endothelial hyperpermeability. Circ Res. 2002;91:618–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vallet B. Endothelial cell dysfunction and abnormal tissue perfusion. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(suppl):229–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parker JL, Adams HR. Selective inhibition of endothelium-dependent vasodilator capacity by Escherichia coli endotoxemia. Circ Res. 1993;72:539–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang P, Ba ZF, Chaudry IH. Endothelium-dependent relaxation is depressed at the macro- and microcirculatory levels during sepsis. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:R988–R994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dimmeler S, Zeiher AM. Endothelial cell apoptosis in angiogenesis and vessel regression. Circ Res. 2000;87:434–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suhara T, Mano T, Oliveira BE, et al. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling controls endothelial cell sensitivity to Fas-mediated apoptosis via regulation of FLICE-inhibitory protein (FLIP). Circ Res. 2001;89:13–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Assaly R, Olson D, Hammersley J, et al. Initial evidence of endothelial cell apoptosis as a mechanism of systemic capillary leak syndrome. Chest. 2001;120:1301–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sylte MJ, Corbeil LB, Inzana TJ, et al. Haemophilus somnus induces apoptosis in bovine endothelial cells in vitro. Infect Immun. 2001;69:1650–1660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Menzies BE, Kourteva I. Staphylococcus aureus alpha-toxin induces apoptosis in endothelial cells. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2000;29:39–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nofer JR, Levkau B, Wolinska I, et al. Suppression of endothelial cell apoptosis by high density lipoproteins (HDL) and HDL-associated lysosphingolipids. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:34480–34485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hotchkiss RS, Tinsley KW, Swanson PE, et al. Endothelial cell apoptosis in sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(suppl):225–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou M, Ba ZF, Chaudry IH, et al. Adrenomedullin binding protein-1 modulates vascular responsiveness to adrenomedullin in late sepsis. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2002;283:R553–R560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fowler DE, Yang S, Zhou M, et al. Adrenomedullin and adrenomedullin binding protein-1: their role in the septic response. J Surg Res. 2003;109:175–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang S, Zhou M, Chaudry IH, et al. Novel approach to prevent the transition from the hyperdynamic phase to the hypodynamic phase of sepsis: role of adrenomedullin and adrenomedullin binding protein-1. Ann Surg. 2002;236:625–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sata M, Kakoki M, Nagata D, et al. Adrenomedullin and nitric oxide inhibit human endothelial cell apoptosis via a cyclic GMP-independent mechanism. Hypertension. 2000;36:83–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang P, Chaudry IH. A single hit model of polymicrobial sepsis: cecal ligation and puncture. Sepsis. 1998;2:227–233. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caulin C, Salvesen GS, Oshima RG. Caspase cleavage of keratin 18 and reorganization of intermediate filaments during epithelial cell apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:1379–1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang P, Zhou M, Ba ZF, et al. Up-regulation of a novel potent vasodilatory peptide adrenomedullin during polymicrobial sepsis. Shock. 1998;10:118–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fowler DE, Wang P. The cardiovascular response in sepsis: proposed mechanisms of the beneficial effect of adrenomedullin and its binding protein [Review]. Int J Mol Med. 2002;9:443–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Asai K, Kudej RK, Shen YT, et al. Peripheral vascular endothelial dysfunction and apoptosis in old monkeys. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:1493–1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi KB, Wong F, Harlan JM, et al. Lipopolysaccharide mediates endothelial apoptosis by a FADD-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:20185–20188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haimovitz-Friedman A, Cordon-Cardo C, Bayoumy S, et al. Lipopolysaccharide induces disseminated endothelial apoptosis requiring ceramide generation. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1831–1841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schumann RR, Belka C, Reuter D, et al. Lipopolysaccharide activates caspase-1 (interleukin-1-converting enzyme) in cultured monocytic and endothelial cells. Blood. 1998;91:577–584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Solovey A, Lin Y, Browne P, et al. Circulating activated endothelial cells in sickle cell anemia. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1584–1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bannerman DD, Goldblum SE. Endotoxin induces endothelial barrier dysfunction through protein tyrosine phosphorylation. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:L217–L226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bannerman DD, Sathyamoorthy M, Goldblum SE. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide disrupts endothelial monolayer integrity and survival signaling events through caspase cleavage of adherens junction proteins. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:35371–35380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harlan JM, Harker LA, Reidy MA, et al. Lipopolysaccharide-mediated bovine endothelial cell injury in vitro. Lab Invest. 1983;48:269–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Flusberg DA, Numaguchi Y, Ingber DE. Cooperative control of Akt phosphorylation, bcl-2 expression, and apoptosis by cytoskeletal microfilaments and microtubules in capillary endothelial cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:3087–3094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ertel W, Morrison MH, Wang P, et al. The complex pattern of cytokines in sepsis: association between prostaglandins, cachectin and interleukins. Ann Surg. 1991;214:141–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hinson JP, Kapas S, Smith DM. Adrenomedullin, a multifunctional regulatory peptide. Endocr Rev. 2000;21:138–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shindo T, Kurihara H, Maemura K, et al. Hypotension and resistance to lipopolysaccharide-induced shock in transgenic mice overexpressing adrenomedullin in their vasculature. Circulation. 2000;101:2309–2316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Caron KM, Smithies O. Extreme hydrops fetalis and cardiovascular abnormalities in mice lacking a functional Adrenomedullin gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:615–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ueda S, Nishio K, Minamino N, et al. Increased plasma levels of adrenomedullin in patients with systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:132–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ono Y, Kojima M, Okada K, et al. cDNA cloning of canine adrenomedullin and its gene expression in the heart and blood vessels in endotoxin shock. Shock. 1998;10:243–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang P, Ba ZF, Cioffi WG, et al. The pivotal role of adrenomedullin in producing hyperdynamic circulation during the early stage of sepsis. Arch Surg. 1998;133:1298–1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang P, Yoo P, Zhou M, et al. Reduction in vascular responsiveness to adrenomedullin during sepsis. J Surg Res. 1999;85:59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pio R, Martinez A, Unsworth EJ, et al. Complement factor H is a serum binding protein for adrenomedullin: the resulting complex modulates the bioactivities of both partners. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:12292–12300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu R, Zhou M, Wang P. Adrenomedullin and adrenomedullin binding protein-1 downregulate TNF-α in macrophage cell line and rat Kupffer cells. Regul Pept. 2003;112:19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kato H, Shichiri M, Marumo F, et al. Adrenomedullin as an autocrine/paracrine apoptosis survival factor for rat endothelial cells. Endocrinology. 1997;138:2615–2620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim W, Moon SO, Sung MJ, et al. Protective effect of adrenomedullin in mannitol-induced apoptosis. Apoptosis. 2002;7:527–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang S, Zhou M, Fowler DE, et al. Mechanisms of the beneficial effect of adrenomedullin and adrenomedullin-binding protein-1 in sepsis: down-regulation of proinflammatory cytokines. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:2729–2735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tokudome T, Horio T, Yoshihara F, et al. Adrenomedullin inhibits doxorubicin-induced cultured rat cardiac myocyte apoptosis via a cAMP-dependent mechanism. Endocrinology. 2002;143:3515–3521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chaudry IH. ATP-MgCl2 and liver blood flow following shock and ischemia. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1989;299:19–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ohkawa M, Clemens MG, Chaudry IH. Studies on the mechanism of beneficial effects of ATP-MgCl2 following hepatic ischemia. Am J Physiol. 1983;244:R695–R702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sumpio BE, Hull MJ, Baue AE, et al. Comparison of effects of ATP-MgCl2 and adenosine-MgCl2 on renal function following ischemia. Am J Physiol. 1987;252:R388–R393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang P, Fowler DE, Yang S, Ornan DA, Zhou M. The mechanism of beneficial effects of adrenomedullin (AM) and adrenomedullin binding protein-1 (AMBP-1) in sepsis: maintenance of vascular endothelial cell function [Abstract]. Shock 2002;17(suppl.):52. [Google Scholar]