Abstract

Soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive fusion protein attachment protein receptor (SNARE) proteins mediate cellular membrane fusion events and provide a level of specificity to donor–acceptor membrane interactions. However, the trafficking pathways by which individual SNARE proteins are targeted to specific membrane compartments are not well understood. In neuroendocrine cells, synaptosome-associated protein of 25 kDa (SNAP25) is localized to the plasma membrane where it functions in regulated secretory vesicle exocytosis, but it is also found on intracellular membranes. We identified a dynamic recycling pathway for SNAP25 in PC12 cells through which plasma membrane SNAP25 recycles in ∼3 h. Approximately 20% of the SNAP25 resides in a perinuclear recycling endosome–trans-Golgi network (TGN) compartment from which it recycles back to the plasma membrane. SNAP25 internalization occurs by constitutive, dynamin-independent endocytosis that is distinct from the dynamin-dependent endocytosis that retrieves secretory vesicle constituents after exocytosis. Endocytosis of SNAP25 is regulated by ADP-ribosylation factor (ARF)6 (through phosphatidylinositol bisphosphate synthesis) and is dependent upon F-actin. SNAP25 endosomes, which exclude the plasma membrane SNARE syntaxin 1A, merge with those derived from clathrin-dependent endocytosis containing endosomal syntaxin 13. Our results characterize a robust ARF6-dependent internalization mechanism that maintains an intracellular pool of SNAP25, which is compatible with possible intracellular roles for SNAP25 in neuroendocrine cells.

INTRODUCTION

In eukaryotic cells, protein and lipids are transported between different organelles of the secretory pathway via vesicular or tubulovesicular intermediates. A key issue is to understand the targeting specificity in membrane trafficking that allows donor vesicle compartments to fuse with appropriate acceptor membranes. The ∼60 members of the Rab superfamily, which are distributed across specific membrane domains (Zerial and McBride, 2001), play an important role in dictating donor and acceptor membrane interactions by assembling compartment-specific tethering complexes that promote organization of soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive fusion protein attachment protein receptor (SNARE) protein complexes (Zerial and McBride, 2001; Ungar and Hughson, 2003). A second layer of specificity for donor and acceptor membrane compartment interaction resides with the selective formation of SNARE complexes that catalyze fusion (McNew et al., 2000). Membrane compartments possess specific subsets of the ∼35 SNARE proteins of the syntaxin, vesicle-associated membrane protein (VAMP), and synaptosome-associated protein of 25 kDa (SNAP25) families (Sollner et al., 1993; Bock et al., 2001). SNARE proteins from each bilayer assemble into four-helix bundles that bridge two membranes to mediate bilayer mixing (Weber et al., 1998; Chen and Scheller, 2001; Jahn et al., 2003). Whereas soluble SNARE motifs form helical bundles with little selectivity, membrane-anchored SNAREs exhibit a high degree of pairing specificity in mediating membrane fusion (McNew et al., 2000; Scales et al., 2000).

An important issue concerns the targeting mechanisms by which the SNARE proteins themselves are delivered to specific membrane compartments. Most of the members of the syntaxin and VAMP families of SNAREs are tail-anchored type II membrane proteins with a C-terminal segment that anchors them in the membrane. These SNAREs are posttranslationally inserted into the bilayer of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (Kutay et al., 1995) and transported to distinct membrane compartments. Whereas in some cases transmembrane domains suffice for membrane targeting (Burri and Lithgow, 2004), in other cases cytoplasmic signals are required for sorting of SNAREs to appropriate membrane compartments (Martinez-Arca et al., 2003). Binding to phosphoinositide lipids that are characteristic of specific membrane compartments also plays a role in targeting certain SNARE proteins to membranes (Cheever et al., 2001).

SNAP25 is a plasma membrane t-SNARE required for Ca2+-triggered vesicle exocytosis in neurons and endocrine cells (Banerjee et al., 1996; Jahn et al., 2003). In contrast to the tail-anchored SNAREs, SNAP25 is palmitoylated on four cysteine residues in a linker domain that connects two helical SNARE motifs (Oyler et al., 1989; Lane and Liu, 1997; Gonzalo and Linder, 1998; Gonzalo et al., 1999). Palmitoylation of SNAP25 confers its initial membrane association (Hess et al., 1992; Gonzalo and Linder, 1998), but mutants lacking the cysteine cluster retain membrane association if paired with syntaxin 1A, another plasma membrane t-SNARE (Vogel et al., 2000; Washbourne et al., 2001). Non-palmitoylated SNAP25 is not, however, targeted properly to the plasma membrane (Loranger and Linder, 2002). Targeting to the plasma membrane requires palmitoylation as well as QPARV residues in the linker domain of SNAP25 (Gonzalo et al., 1999; Loranger and Linder, 2002). The cellular site of SNAP25 palmitoylation is unknown although HIP14, a putative SNAP25 palmitoyltransferase, is Golgi and cytoplasmic vesicle localized (Huang et al., 2004). Based on the sensitivity of SNAP25 palmitoylation to brefeldin A (BFA) treatment, it was suggested that trafficking to the plasma membrane is via the Golgi (Gonzalo and Linder, 1998).

The intracellular pool of SNAP25 in neural and neuroendocrine cells has been variously attributed to Golgi, endosomes, or secretory vesicles (Duc and Catsicas, 1995; Marxen et al., 1999; Morgans and Brandstatter, 2000), but it is unknown whether this pool represents newly biosynthesized SNAP25 undergoing transport to the plasma membrane. Transport vesicles that convey SNAP25 from a putative Golgi pool to the plasma membrane were suggested to consist of dense-core synaptic precursor vesicles in immature neurons (Zhai et al., 2001) or tubulovesicular transport vesicles in mature neurons that undergo fast axonal transport (Li et al., 1996; Nakata et al., 1998; Ahmari et al., 2000).

In the current study, we identified a dynamic recycling pathway for SNAP25 in PC12 neuroendocrine cells through which SNAP25 recycles between the plasma membrane and an endosome-TGN compartment. SNAP25 internalization occurs by a constitutive, ADP-ribosylation factor (ARF)6-regulated, dynamin-independent pathway of endocytosis that requires F-actin. SNAP25 endosomes, which exclude the plasma membrane SNARE partner of SNAP25, syntaxin 1A, merge with those derived from clathrin-dependent endocytosis whereupon SNAP25 associates with a new SNARE partner, endosomal syntaxin 13. These results characterize an ARF6-regulated recycling pathway that maintains an intracellular pool of SNAP25, which is compatible with possible intracellular roles for SNAP25.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture, Transfection, and DNA Constructs

PC12 cells were cultured and transfected by electroporation as described previously (Aikawa and Martin, 2003). Where indicated, cells were pretreated with media containing 10 μg/ml cycloheximide (CHX) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), 1 μM latrunculin A (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) or 5 μg/ml BFA (Epicenter Technologies, Madison, WI) for indicated times. A plasmid encoding an N-terminal enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) fusion with mouse SNAP25B was prepared by PCR amplification of the SNAP25B open reading frame and cloning into pEGFP-C1 (Clontech, Mountain View, CA). Constructs were checked by sequencing. Dynamin 1-hemagglutinin (HA) (wild-type and K44A) constructs were generously provided by S. L. Schmid (The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA), Rab5-green fluorescent protein (GFP) (wild-type, Q79L, S34N) constructs by S. Ferguson (Robarts Research Institute, London, Ontario, Canada), myc-syntaxin 13 construct by H. Hirling (Laboratoire de Neurobiologie Cellulaire, Lausanne, Switzerland), and the PLCδ1 PH-GFP construct by T. Balla (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). ARF6-GFP (wild-type, Q67L, T27N) constructs were described previously (Aikawa and Martin, 2003).

Immunofluorescence, Western Blotting, and Immunoprecipitation

Immunocytochemistry was performed as described previously (Aikawa and Martin, 2003). Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 30 min, and permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS. Primary antibodies were diluted in PBS containing 10% fetal calf serum. The following primary antibodies were used: monoclonal anti-HA (BAbCO, Richmond, CA), 1:1000; polyclonal anti-HA (BAbCO), 1:1000; monoclonal anti-SNAP25 (Sternberger Monoclonals, Lutherville, MD), 1:1000; monoclonal anti-syntaxin 1A (Sigma-Aldrich), 1:1000; monoclonal anti-TGN-38 (K. Howell, University of Colorado, Denver, CO), 1:10,000; monoclonal anti-phosphatidylinositol(4,5)bisphosphate (PIP2) (K. Fukami, University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan); polyclonal anti-mannosidase II (K. Moremen, University of Georgia, Athens, GA), 1:100; polyclonal anti-cathepsin D (Wako Pure Chemicals, Osaka, Japan); and monoclonal anti-Rab11 (Zymed Laboratories, South San Francisco, CA), 1:500.

To monitor synaptotagmin endocytic recycling, PC12 cells were incubated at 37°C with 5 μg/ml N-terminal anti-synaptotagmin 1 antibody (Sigma-Aldrich) with calcium-free Locke's solution (basal release) or stimulated with an elevated K+ solution (Locke's containing 59 mM KCl and 85 mM NaCl). After washing, cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde, permeabilized with Triton X-100 and reacted with secondary antibody. For F-actin labeling, fixed Triton X-100-permeabilized cells were incubated with Alexa 568-phalloidin. The uptake of Alexa 568-transferrin (Tf) and Texas Red 10 kDa dextran was described previously (Aikawa and Martin, 2003). For Alexa 647-cholera toxin B subunit (CTxB) uptake, cells were incubated on ice for 30 min to bind CTxB followed by extensive washing with calcium-free Locke's solution and subsequent incubation at 37°C for indicated times. Texas Red-conjugated dextran and Alexa-conjugated probes were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA), Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting were conducted as described previously (Aikawa and Martin, 2003). PC12 cells were fractionated into membrane and cytosolic fractions for Western blotting by homogenizing cell suspensions in a ball homogenizer with subsequent centrifugation of homogenates at 288,000 × g for 2 h.

Confocal Microscopy and Live Cell Imaging

Cells were examined using a Bio-Rad MRC-600 or a Nikon C1 laser scanning confocal microscope with 63 or 100× oil immersion objectives. Quantitation of fluorescence was conducted with MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) on images from more than 100 cells from at least three independent experiments. Significance was evaluated by t test (asterisk, p < 0.001). Selective photobleaching on live cells at 37°C was conducted on a Bio-Rad MRC-1024 laser scanning confocal microscope with a 488-nm laser line at lowest power for 10–15 s. For the analysis of fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) data, a multicompartment model of SNAP25 trafficking was developed (Figure 6G). The plasma membrane and Golgi/endosome pools of SNAP25 were treated as two compartments exchanging via first order kinetics with k1 corresponding to the rate constant of SNAP25 transport from a Golgi/endosome compartment to the plasma membrane and k2 corresponding to the rate constant of SNAP25 internalization from the plasma membrane. The initial value of k2 was set to 0, which corresponds to no SNAP25 recycling, and was increased stepwise in increments of 0.5% min-1. For each value, a theoretical curve was generated for the model using Microsoft Excel. The SD between the experimental data and the theoretical curve was calculated for each k2 value and compared. Final values of k1 and k2 generated theoretical curves with minimal SD.

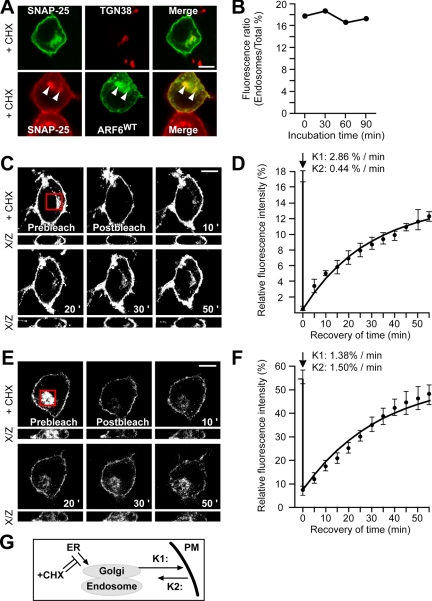

Figure 6.

Recovery after photobleaching defines the kinetics of SNAP25 internalization and recycling. (A) PC12 cells expressing GFP-SNAP25 (top) or ARF6-GFP (bottom) were treated with 10 μg ml-1 CHX for 120 min and immunostained for TGN-38 (red) or SNAP25 (red) respectively. (B) Quantitation of relative fluorescence intensity of intracellular compartment of endogenous SNAP25 after treatment with 10 μg ml-1 CHX for indicated times. Fifty randomly selected cells were quantitated for each time point. (C) Photobleaching of intracellular GFP-SNAP25. Cells expressing GFP-SNAP25 were incubated with CHX for 30 min, and the intracellular compartment (red box) was bleached by the 488-nm laser. Z-section images were collected every 5 min for the next 60 min. (D) Time course of recovery of intracellular GFP-SNAP25 after photobleaching. Plot shows mean relative fluorescence intensity for perinuclear region (•) on three confocal slices near the middle of cells from a typical experiment. Solid line is drawn from model using indicated values of k1 and k2. (E) Photobleaching of intracellular pool of GFP-SNAP25 (red box) in CHX-treated cells expressing ARF6Q67L. (F) Time course of recovery of intracellular GFP-SNAP25 after photobleaching in ARF6Q67L-expressing cells is shown as increase in mean relative fluorescence intensity (•) on three confocal slices near the middle of cells from a typical experiment. Solid line is drawn from model using indicated values of k1 and k2. (G) Two compartment model for SNAP25 trafficking.

RESULTS

ARF6 Regulates the Internalization of Plasma Membrane SNAP25

SNAP25 predominantly localizes to the plasma membrane in neural and neuroendocrine cells where it functions as a t-SNARE in regulated vesicle exocytosis (Banerjee et al., 1996; Jahn et al., 2003). However, a substantial portion of the SNAP25 in PC12 cells is also distributed in a perinuclear compartment that has not been characterized previously (Figure 1A). We found that expression of the constitutively active GTP-bound ARF6Q67L mutant in PC12 cells promoted an extensive intracellular accumulation of SNAP25 (Aikawa and Martin, 2003), so we further investigated the role of ARF6 in the trafficking of SNAP25. ARF6 regulates plasma membrane-endosome trafficking in cells (D'Souza-Schorey et al., 1995; Peters et al., 1995), and expression of the ARF6Q67L mutant redistributes plasma membrane constituents to an endosomal vacuolar compartment (Brown et al., 2001; Aikawa and Martin, 2003; Naslavsky et al., 2003). Wild-type ARF6 was found to colocalize with SNAP25 in tubular invaginations of the plasma membrane (Figure 1A, arrowheads in X/Z). In time-lapse imaging of GFP-SNAP25, tubulovesicular membranes containing SNAP25 were found to pinch off from the tubular invaginations and move away from the plasma membrane within 90 s (Figure 1B, circles). These results indicate that plasma membrane SNAP25 undergoes constitutive endocytosis.

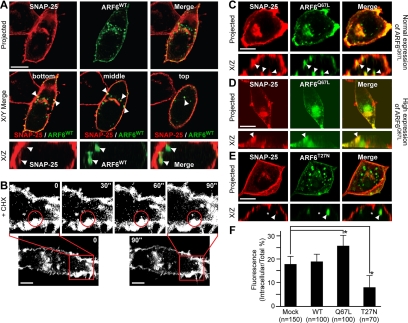

Figure 1.

SNAP25 is constitutively internalized from the plasma membrane into ARF6-positive tubular vesicles. (A) PC12 cells expressing ARF6WT-GFP (green) were fixed for immunostaining with a SNAP25 mAb (red). Confocal images shown are projected sections (top row) or merges of optical sections for bottom, middle, and top portions of the cell (middle). Vertical (X/Z) sections from separate fields are shown (bottom). Arrowheads indicate the colocalization of endogenous SNAP25 and ARF6WT-GFP. (B) Images obtained in a real-time series of live PC12 cells (CHX-treated) expressing GFP-SNAP25 recorded every 30 s. Boxed areas are enlarged to show SNAP25-containing vesicles pinching off (circled). Bars, 5 μm. Cells expressing normal (C) or high (D) levels of ARF6Q67L-GFP or expressing ARF6T27N-GFP (E) were immunostained with a monoclonal SNAP25 antibody (red). Projected images and vertical sections (X/Z) from confocal microscopy are shown. Arrowheads indicate invaginations in which ARF6Q67L and SNAP25 colocalization was apparent. Asterisk in E (X/Z) indicates absence of ARF6T27N and SNAP25 colocalization in tubular invaginations. Bars, 10 μm. (F) Quantitative analysis of intracellular SNAP25 in randomly selected cells expressing ARF6 and its mutants. The ratio of intracellular to total SNAP25 immunofluorescence × 100% was plotted as mean values (with SEM; asterisks indicate p < 0.001).

Expression of the GTP-bound ARF6Q67L mutant increased the number of tubular invaginations containing SNAP25 (Figure 1C, arrowheads in X/Z) and increased the perinuclear distribution of SNAP25 (Figure 1C). In a subpopulation (∼25%) of cells that expressed high levels of ARF6Q67L, extensive accumulation of SNAP25 on an intracellular ARF6Q67L-positive vacuole was observed with a corresponding depletion of SNAP25 from the plasma membrane (Figure 1D). In contrast, expression of the GDP-bound ARF6T27N mutant resulted in a decreased number of tubular invaginations containing SNAP25 and a reduced perinuclear distribution of SNAP25 (Figure 1E). Quantitation of images confirmed that the intracellular pool of SNAP25 was significantly increased in cells expressing ARF6Q67L and reduced in cells expressing ARF6T27N (Figure 1F). The results indicate that the ARF6 GTPase regulates the internalization of SNAP25 from the plasma membrane into an intracellular compartment with GTP-bound ARF6 functioning to promote SNAP25 internalization.

SNAP25 Endocytosis Is Dynamin Independent but PIP2 and Actin Dependent

Cells internalize plasma membrane constituents by several pathways that include clathrin-dependent and -independent endocytosis (Nichols and Lippincott-Schwartz 2001; Conner and Schmid 2003). Endocytosis via clathrin-coated pits is dependent on the GTPase dynamin and is inhibited by expression of the dominant negative K44A dynamin mutant (Damke et al., 1994). To investigate whether SNAP25 internalization is dependent on dynamin, we expressed HA-tagged dynamin-1 K44A and examined the subcellular distribution of SNAP25. Expression of the dynamin K44A mutant but not wild type strongly depressed Tf uptake (Figure 2B). In contrast, the relative fluorescence intensity of intracellular SNAP25 (Figure 2B, right) constituting ∼18% of the total protein (wild type; 17.8%; n = 150) was not changed by expression of either wild-type or K44A dynamin (K44A; 18.3%; n = 50), which indicates that SNAP25 internalization is mediated by a dynamin-independent pathway.

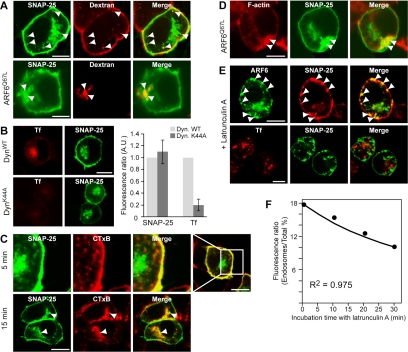

Figure 2.

SNAP25 internalization is dynamin independent and F actin dependent. (A) PC12 cells expressing GFP-SNAP25 (top row) or GFP-SNAP25 and ARF6Q67L (bottom row) were incubated with Texas-Red 10 kDa dextran for 5 min. Arrowheads indicate the colocalization of GFP-SNAP25 (green) with dextran (red) in peripheral endosomes (top) or the accumulation of dextran in the SNAP25-containing vacuole induced by ARF6Q67L expression (bottom). (B) PC12 cells expressing dynamin wild type (top row) or dynamin K44A mutant (bottom row) and GFP-SNAP25 (green) were incubated with Alexa 568-conjugated Tf (red) for 30 min. Tf uptake and perinuclear SNAP25 were quantitated in images of 50 randomly selected cells. Expression of dynamin K44A inhibited Tf uptake without affecting perinuclear SNAP25. (C) PC12 cells expressing GFP-SNAP25 (green) were incubated with CTxB-Alexa 648 (red) for 5 or 15 min. There was little colocalization of CTxB with SNAP25 in peripheral endosomes in 5-min incubations (top row), whereas CTxB colocalized extensively with GFP-SNAP25 in the perinuclear region in 15-min incubations (bottom row, arrowheads). (D) PC12 cells expressing GFP-SNAP25 (green) and ARF6Q67L were fixed for staining with Alexa 568-phalloidin (red). Projected images indicated that the SNAP25-containing vacuole is coated with F-actin (arrowheads). (E) Top row, PC12 cells expressing ARF6WT-GFP (green) were treated with 1 μM latrunculin A for 30 min, fixed, and stained with monoclonal SNAP25 antibody (red). SNAP25 accumulated on ARF6-positive tubular invaginations from the plasma membrane (arrowheads). Bottom row, PC12 cells expressing GFP-SNAP25 (green) were treated with latrunculin A for 10 min and incubated with Alexa 568-conjugated Tf for 30 min (red). Latrunculin A did not affect Tf uptake but blocked internalization of SNAP25. (F) Intracellular SNAP25 was quantitated in 50 randomly selected cells after treatment with 1 μM latrunculin A for indicated times. The ratio of intracellular to total immunofluorescence × 100% was plotted as mean values (•). Solid line, which corresponds to a theoretical curve based on the rate constant for SNAP25 recycling back to the plasma membrane (k1 = 2.86% min-1; see Figure 6) and the assumption that SNAP25 internalization was blocked (k2 = 0), fit well to experimental data points (r = 0.975).

Expressed GFP-SNAP25 was found to colocalize with the endogenous immunoreactive SNAP25 in PC12 cells (our unpublished data). To further characterize the pathway of SNAP25 endocytosis, cells expressing GFP-SNAP25 were incubated with Alexa 648-conjugated CTxB, a marker for gangloside GM1-containing lipid rafts, which traffic from the plasma membrane to the Golgi complex by a clathrin-independent mechanism (Nichols et al., 2001). There was little overlap between CTxB and GFP-SNAP25 after 5 min of CTxB uptake (Figure 2C, top row) but by 15 min of uptake, there was extensive colocalization of CTxB with GFP-SNAP25 in a perinuclear compartment that may correspond in part to the TGN (Figure 2C, bottom row, arrowheads). Thus, it seems that the initial internalization pathways for CTxB and SNAP25 differ, but there is subsequent convergence of these pathways. Similar studies were undertaken with Texas Red-dextran, a marker for fluid phase uptake. In this case, peripheral endosomes containing GFP-SNAP25 were readily labeled with the dextran in incubations as short as 5 min (Figure 2A, top row, arrowheads), which indicates that SNAP25 endosomes arise from pinocytosis. Consistent with this, expression of the constitutively active ARF6Q67L mutant promoted fluid phase uptake of dextran that colocalized with SNAP25 (Figure 2A, bottom row, arrowheads). These data indicate that SNAP25 internalization is mediated by a dynamin-independent pathway of micropinocytosis that is ARF6 regulated, which is similar to that previously observed for plasma membrane proteins that lack conventional endocytic signals for clathrin-dependent endocytosis (Radhakrishna and Donaldson, 1997).

In other cell types, expression of ARF6Q67L was reported to promote F-actin-rich protrusions of the plasma membrane (D'Souza-Schorey et al., 1997; Radhakrishna et al., 1999). To assess whether the internalization of SNAP25 involves F-actin, we determined the distribution of F-actin using fluorescent phalloidin in cells expressing ARF6. Expression of wild type and ARF6T27N did not alter the distribution of F-actin normally observed (our unpublished data). In contrast, expression of ARF6Q67L resulted in an increased density of F-actin around the peripheral vacuolar compartment where SNAP25 accumulated (Figure 2D). To determine whether F-actin assembly was required for the internalization of SNAP25, we used latrunculin A, an inhibitor of actin polymerization. After brief incubations with latrunculin A, we observed enlarged ARF6-positive tubular invaginations at the plasma membrane that contained SNAP25 (Figure 2E, top row, arrowheads). Longer incubations with latrunculin A progressively reduced the intracellular pool of SNAP25 (Figure 2F). We could entirely account for the rate of loss of intracellular SNAP25 by assuming that latrunculin A solely inhibited the internalization of plasma membrane SNAP25 (see Figure 2F and legend). The results indicate that actin polymerization is required for SNAP25 internalization. In contrast, latrunculin A treatment failed to affect the clathrin-dependent uptake of Tf into PC12 cells (Figure 2E, bottom row). These studies indicate that F-actin plays an essential role in generating the tubulovesicular transport intermediates from tubular invaginations that mediate SNAP25 internalization from the plasma membrane.

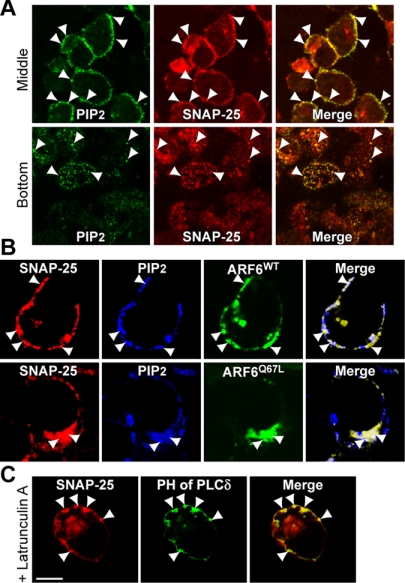

Our previous studies showed that ARF6 regulates phosphatidylinositol(4)phosphate 5-kinase type I [PI(4)P 5-kinase] and plasma membrane PIP2 synthesis in PC12 cells (Aikawa and Martin, 2003). To determine whether PIP2 may be involved in SNAP25 internalization, we conducted localization studies on this phospholipid. Localization studies with a PIP2-specific monoclonal antibody (mAb) in permeable PC12 cells revealed a high degree of colocalization of PIP2 with SNAP25 on the plasma membrane (Figure 3A, arrowheads) with each present in a punctate distribution. The membrane puncta contained ARF6 as well as PIP2 (Figure 3B, top row, arrowheads). In addition, expression of ARF6Q67L, which activates PI(4)P 5-kinase (Honda et al., 1999; Brown et al., 2001; Aikawa and Martin, 2003; Krauss et al., 2003), promoted extensive membrane PIP2 and SNAP25 internalization (Figure 3B, bottom row, arrowheads) as reported for other cell types (Brown et al., 2001; Delaney et al., 2002). Overall, these results suggest that SNAP25 is present in membrane domains containing ARF6 that may be active sites of PIP2 synthesis.

Figure 3.

Plasma membrane SNAP25 colocalizes with PIP2 and ARF6. (A) SNAP25 (red) and PIP2 (green) colocalize in permeable PC12 cells. Permeabilized cells were incubated with Mg-ATP and rat brain cytosol for 30 min, fixed and stained with monoclonal PIP2 antibody (green) and polyclonal SNAP25 antibody (red). Middle and bottom confocal sections of cells are shown. Arrowheads indicate examples where SNAP25 and PIP2 puncta colocalize. (B) Immunoreactive PIP2 was detected in permeable PC12 cells expressing ARF6WT-GFP (top row) or ARF6Q67L-GFP (bottom row). Arrowheads indicate colocalization of immunoreactive SNAP25 (red), PIP2 (blue), and ARF6-GFP proteins (green). (C) Cells expressing a PLCδ1-PH-GFP fusion protein (green) were treated with 1 μM latrunculin A for 30 min, fixed, and stained with a monoclonal SNAP25 antibody (red). Arrowheads indicate the colocalization of SNAP25 and the PLCδ1-PH-domain-GFP protein. All bars, 10 μm.

PIP2 is known to modulate the activities of many actin regulatory proteins to promote F-actin formation involved in membrane movement (Yin and Janmey, 2003). PIP2 synthesis at SNAP25-containing membrane domains might promote membrane internalization by nucleating F-actin similarly to that described for phagocytosis (Botelho et al., 2000). Consistent with this possibility, we found that treatment of cells with latrunculin A resulted in the accumulation of SNAP25-containing tubular invaginations at the plasma membrane that were enriched in PIP2 but did not undergo internalization (Figure 3C, arrowheads). Overall, these data suggest that ARF6-regulated PIP2 synthesis on the plasma membrane in SNAP25-containing domains promotes local F-actin formation for membrane internalization.

Internalized SNAP25 Merges with Early Endosomes and Transits to the Recycling Endosome

Although SNAP25 is internalized by an ARF6-dependent, dynamin-independent endocytic pathway, SNAP25 was reported to be present in an early endosomal autoantigen 1-positive early endosomal compartment (Sun et al., 2003). To determine whether SNAP25 endosomes merge with endosomes derived from the clathrin-mediated pathway, we monitored the uptake of Alexa 568-Tf. In brief (5-min) incubations, there was little colocalization of internalized Tf with SNAP25 endosomes (Figure 4A), but in longer (15- and 30-min) incubations, there was considerable overlap (Figure 4A, arrowheads). These data suggest that SNAP25 endosomes derived from the ARF6-dependent, dynamin-independent pathway merge to some extent with those derived from the clathrin-dependent pathway. Similar convergence of ARF6-dependent endosomes with those from the clathrin-dependent pathway in HeLa cells has been reported previously (Naslavsky et al., 2003).

Figure 4.

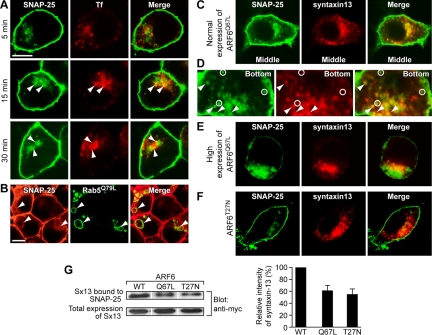

SNAP25-containing endosomes merge with Tf-positive endosomal compartments. (A) PC12 cells expressing GFP-SNAP25 (green) and human Tf receptor were incubated with Alexa 568-conjugated Tf (red) for indicated times. Arrowheads indicate the colocalization of GFP-SNAP25 and Tf. Bar, 10 μm. (B) PC12 cells expressing Rab5Q79L-GFP (green) were fixed and immunostained for endogenous SNAP25 (red). Arrowheads indicate the accumulation of endogenous SNAP25 on Rab5Q79L-positive endosomes. PC12 cells expressing myc-syntaxin 13 (red) and ARF6Q67L (C–E) or ARF6T27N (F) were fixed and stained for endogenous SNAP25 (green). (C) There was significant colocalization of SNAP25 and syntaxin 13 in the perinuclear region. (D) Near the ventral surface of the cells, some of SNAP25 endosomes contained syntaxin 13 (arrowheads), whereas other SNAP25 endosomes did not contain syntaxin 13 (circles). (E) In cells expressing higher levels of ARF6Q67L, SNAP25 was trapped in an endosomal vacuole where it segregated from syntaxin-13-positive endosomes. (F) ARF6T27N expression interfered with the internalization of SNAP25 and little colocalization of syntaxin 13 with SNAP25 was seen in the perinuclear region. (G) Expression of ARF6Q67L and ARF6T27N mutants alter the coimmunoprecipitation of syntaxin 13 with SNAP25. SNAP25 antibody immunoprecipitates were prepared from detergent lysates of cells expressing myc-syntaxin 13 and ARF6WT, ARF6Q67L, or ARF6T27N. Immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blotting with c-myc antibody to quantitate myc-syntaxin 13. Mean values with SEM are shown for three experiments. Coimmunoprecipitated myc-syntaxin 13 was significantly (p < 0.05) reduced in ARF6Q67L- and ARF6T27N-expressing cells.

A subset of SNAP25-containing endosomes were positive for Rab5 (our unpublished data), a protein that regulates the fusion of endocytic vesicles with early endosomes (Zerial and McBride, 2001). To further delineate early endosomal compartments containing SNAP25, we examined the effect of expressing Rab5Q79L, which stimulates homotypic early endosomal fusion (Stenmark et al., 1994). Expression of the constitutively active Rab5Q79L promoted the formation of large endosomal vacuoles that contained SNAP25 (Figure 4B, arrowheads). This result is similar to that reported for ARF6-dependent MHC I-containing endosomes in HeLa cells (Naslavsky et al., 2003) and indicates that SNAP25 endosomes derived from the ARF6-regulated pathway merge with Rab5-positive early endosomes in a peripheral endosomal sorting compartment.

Syntaxin 13 is a SNARE protein resident on early and recycling endosomes that colocalizes with endocytosed Tf (Prekeris et al., 1998). To characterize endosomal compartments to which SNAP25 is transported, we determined the localization of SNAP25 and syntaxin 13 in PC12 cells. Syntaxin 13 was present on peripheral endosomes and on a perinuclear compartment that represents recycling endosomes (Figure 4C). SNAP25 colocalized with syntaxin 13 in the perinuclear recycling endosome compartment (Figure 4C). In addition, many peripheral SNAP25-containing endosomes were positive for syntaxin 13 (Figure 4D, arrowheads), whereas others were negative (Figure 4D, circles). These results suggest the possibility that SNAP25 endosomes merge with syntaxin 13-containing endosomes at a point before the delivery of SNAP25 into the recycling endosome compartment.

Cells that extensively overexpress ARF6Q67L exhibit an accumulation of SNAP25 in a vacuolar compartment that is more peripherally localized than the perinuclear syntaxin 13-containing recycling compartment (Figure 4E). This may indicate that the ARF6Q67L mutant drives the initial internalization of SNAP25 but prevents its trafficking to the recycling compartment. In contrast, expression of ARF6T27N effectively inhibited SNAP25 internalization, and there was little colocalization of SNAP25 with syntaxin 13 (Figure 4F). As an independent measure of the transit of SNAP25 to a syntaxin 13-containing compartment, we conducted coimmunoprecipitation studies to determine the cellular association of these SNARE proteins. Syntaxin 13 was readily isolated in SNAP25 immunoprecipitates from wild-type ARF6-expressing cells (Figure 4G) as reported previously (Prekeris et al., 1998). In contrast, SNAP25/syntaxin 13 complexes were substantially reduced in cells overexpressing the ARF6Q67L mutant consistent with lack of delivery of SNAP25 to the syntaxin 13-containing recycling endosome compartment (Figure 4G). Expression of the ARF6T27N mutant, which inhibited SNAP25 internalization, also reduced SNAP25 coimmunoprecipitation with syntaxin 13 (Figure 4G). The results are consistent with the notion that SNAP25 endosomes merge with syntaxin 13-containing endosomes and are delivered into the recycling endosome compartment.

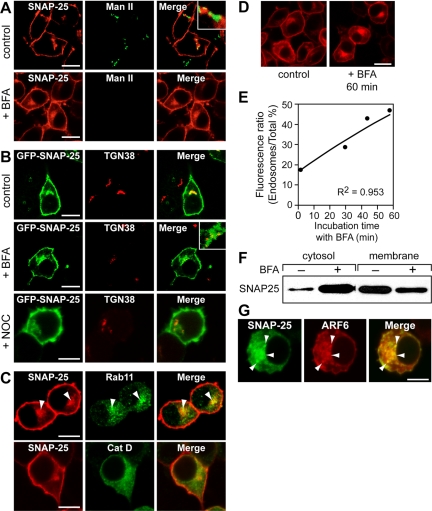

Brefeldin A Inhibits the Recycling of SNAP25 Back to the Plasma Membrane

We sought to further characterize the intracellular compartments to which internalized SNAP25 was transported by comparing the distribution of intracellular SNAP25 with that of well-characterized markers for Golgi, endosomal, and lysosomal compartments. The distribution of SNAP25 was found to overlap little with the cis-Golgi marker mannosidase II (Figure 5A). BFA treatment redistributes Golgi proteins back to the ER (Robinson and Kreis, 1992), collapses the TGN and endosome onto the microtubule-organizing center (Lippincott-Schwartz et al., 1991), and induces tubulation of the endosome recycling compartment (van Dam and Stoorvogel, 2002). Whereas BFA treatment completely dispersed mannosidase II, it promoted a redistribution of perinuclear SNAP25 into a more diffuse but still perinuclear distribution (Figure 5A). SNAP25 overlapped extensively with the TGN marker TGN-38 (Figure 5B), and BFA treatment did not significantly affect this colocalization. Colocalization of some of the intracellular SNAP25 with TGN-38 persisted after nocodazole treatment (Figure 5B). There was also substantial colocalization of SNAP25 with the recycling endosome marker Rab 11 but not with the lysosomal protein cathepsin D (Figure 5C). Overall, these results indicate that intracellular SNAP25 localizes to perinuclear recycling endosomal and TGN compartments.

Figure 5.

BFA inhibits SNAP25 recycling to the plasma membrane. PC12 cells were treated with 5 μg ml-1 BFA for 30 min or with 3 μg ml-1 nocodazole (NOC) for 60 min where indicated. Immunocytochemistry was conducted to localize SNAP25 (A–D), Golgi mannosidase II (A), TGN-38 (B), Rab11 (C, top row), or cathepsin D (C, bottom row). Perinuclear SNAP25 colocalized with TGN-38 and Rab11 but not with mannosidase II or cathepsin D. (D) BFA treatment for 60 min promoted an accumulation of perinuclear SNAP25 detected by immunocytochemistry. (E) The accumulation of perinuclear SNAP25 was quantitated in 50 randomly selected cells for indicated time points after BFA addition. The ratio of intracellular to total SNAP25 immunofluorescence × 100% was plotted as mean values (•). A theoretical curve (solid line) based on the rate constant for SNAP25 internalization (k2 = 0.44% min-1) derived from FRAP analysis (see Figure 6) and the assumption that SNAP25 recycling back to the plasma membrane was blocked (k1 = 0) fit well to experimental data points (r = 0.953). (F) BFA treatment converted some membrane-associated SNAP25 to cytosolic SNAP25. PC12 cells were treated with 5 μg ml-1 BFA for 60 min where indicated. Membrane (10 μg of protein corresponding to 0.3% of total) and cytosol (5 μg protein corresponding to 0.65% of total) fractions were analyzed for SNAP25 by Western blotting and densitometry. Correcting for total recovered membrane and cytosol protein, we calculated that 97% of the total SNAP25 was membrane-associated in untreated cells, whereas only 50% was membrane-associated in BFA-treated cells. (G) Immunoreactive SNAP25 (green) colocalized with expressed ARF6-HA (red) in an expanded recycling endosome compartment after 60 min of BFA treatment (arrowheads).

BFA treatment promoted a progressive accumulation of SNAP25 in the recycling endosome-TGN compartment (Figure 5, D and E). This BFA-induced accumulation was at the expense of the plasma membrane SNAP25 pool and was also observed in the presence of cycloheximide to inhibit de novo SNAP25 synthesis (Gonzalo and Linder, 1998). The intracellular pool of SNAP25 accumulated with BFA was ARF6-positive (Figure 5G) suggesting that it represented an expanded recycling endosome compartment. BFA treatment induces tubulation of the recycling endosome compartment and retards the recycling of proteins back to the plasma membrane (van Dam and Stoorvogel, 2002). Consistent with this, we could entirely account for the rate of accumulation of SNAP25 in the recycling endosome compartment by assuming that BFA solely inhibited recycling back to the plasma membrane (see Figure 5E and legend). The results indicate that internalized SNAP25 traffics to a recycling endosome-TGN compartment from which it recycles back to the plasma membrane by a BFA-sensitive pathway.

SNAP25 is mainly (>97%) membrane-associated at steady state (Figure 5F). However, BFA treatment for an hour was found to convert a considerable portion (∼50%) of SNAP25 to a cytosolic form (Figure 5F). BFA treatment has been reported to inhibit the palmitoylation of SNAP25 (Gonzalo and Linder, 1998). Our results indicate that BFA treatment both inhibited SNAP25 transport from the recycling endosome-TGN compartment back to the plasma membrane (Figure 5, D and E) as well as promoted solubilization of the protein (Figure 5F). Collectively, these results suggest that the palmitoylation of SNAP25 may be coupled to its recycling back to the plasma membrane.

ARF6Q67L Stimulates the Endocytosis of SNAP25 and Blocks Recycling

The portion of perinuclear SNAP25 that colocalizes with TGN-38 (Figure 5B) could represent biosynthetic SNAP25, which was reported to transit through the Golgi (Duc and Catsicas, 1995; Gonzalo and Linder, 1998; Tao-Cheng et al., 2000; Morgans and Brandstatter, 2000), or could represent retrograde transport from recycling endosomes to the TGN (Reaves et al., 1993; Ghosh et al., 1998). Incubation of PC12 cells in cycloheximide at concentrations that fully block protein synthesis had little effect on perinuclear SNAP25 for the initial 90 min of incubation (Figure 6B). These results indicate that most of the SNAP25 detected in the perinuclear compartment does not represent de novo-synthesized protein. Under conditions of inhibited protein synthesis, SNAP25 localized to ARF6-positive endosomes and TGN-38-positive TGN elements (Figure 6A). These data are compatible with the endosomal trafficking of SNAP25 from the plasma membrane to both the recycling endosome compartment as well as the TGN.

To directly monitor rates of transit between the plasma membrane and the recycling endosome-TGN destination, we used FRAP in cells expressing GFP-SNAP25. Selective photobleaching of the intracellular pool of GFP-SNAP25 in cycloheximide-treated cells was followed by recovery of the intracellular GFP-SNAP25 fluorescence at the expense of the plasma membrane GFP-SNAP25 (Figure 6, C and D). Seventy-five percent of the intracellular pool of GFP-SNAP25 recovered in a 50-min incubation (Figure 6D), confirming that intracellular SNAP25 is in dynamic exchange with the plasma membrane. Kinetic modeling of the recovery time course based on first order processes for exchange in a two compartment model (Figure 6G) provided estimates of the rate constants as 2.86% min-1 for SNAP25 transport from the recycling endosome-TGN compartment to the plasma membrane (k1) and 0.44% min-1 for plasma membrane internalization to the intracellular compartment (k2) (Figure 6D). Similar studies were conducted in cells expressing ARF6Q67L (Figure 6, E and F). The rate constant for SNAP25 internalization (k2) increased three- to fourfold to 1.5% min-1, whereas the rate constant for recycling back to the plasma membrane (k1) decreased twofold to 1.38% min-1 in cells expressing ARF6Q67L (Figure 6F). The data indicate that the constitutive active ARF6Q67L mutant accelerates the endocytosis of SNAP25 and slows its recycling back to the plasma membrane.

ARF6 Constitutively Regulates the Internalization of SNAP25 but Not Syntaxin 1A

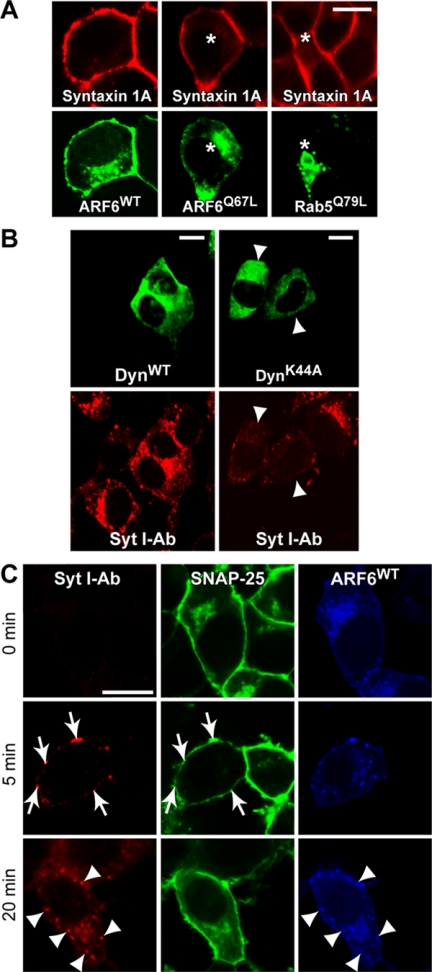

SNAP25 forms a heterodimeric complex with syntaxin 1A (Jahn et al., 2003), and it was suggested that these proteins traffic together (Vogel et al., 2000;Washbourne et al., 2001). In immunofluorescence studies, syntaxin 1A was found exclusively at the plasma membrane with none detected on intracellular membranes (Figure 7A). Expression of constitutive active ARF6Q67L, dominant negative ARF6T27N, or constitutive active Rab5Q79L, which markedly alter the distribution of SNAP25, did not affect the exclusive plasma membrane distribution of syntaxin 1A (Figure 7A). These results indicate that plasma membrane SNAP25 is selectively recycled by the ARF6-regulated endocytic pathway and is segregated from syntaxin 1A.

Figure 7.

SNAP25 is not cointernalized with syntaxin 1A nor with vesicle constituents after exocytosis. (A) PC12 cells expressing ARF6WT-, ARF6Q67L-, or Rab5Q79L-GFP (green) were immunostained for syntaxin-1A (red). Asterisks indicate enlarged endosomal vacuoles that did not contain syntaxin 1A. (B) PC12 cells expressing wild-type dynamin-HA or K44A dynamin-HA were incubated with synaptotagmin I antibody in 59 mM K+ buffer for 20 min and fixed for immunostaining with HA antibody (green) and anti-rabbit IgG (red). Cells expressing K44A dynamin exhibited reduced synaptotagmin I antibody uptake (arrowheads). (C) Cells expressing HA-ARF6WT (blue) and GFP-SNAP25 (green) were incubated for indicated times in 59 mM K+ buffer with synaptotagmin I antibody (red). Arrows indicate sites of vesicle fusion that colocalize GFP-SNAP25 and synaptotagmin I antibody on the plasma membrane. Arrowheads indicate the colocalization of internalized synaptotagmin I antibody with ARF6WT.

Plasma membrane SNAP25 is essential for Ca2+-dependent exocytosis of dense-core vesicles in PC12 cells (Banerjee et al., 1996; Jahn et al., 2003) during which SNARE complex formation with VAMP 2 and syntaxin 1A is required. SNAP25 also interacts with synaptotagmin, which plays a role in the Ca2+-triggering mechanism for SNARE complex formation and vesicle exocytosis (Zhang et al., 2002). After exocytosis, there is the compensatory endocytic retrieval of dense-core vesicle components (Patzak and Winkler, 1986; Henkel et al., 2001), but the precise point at which SNARE complex constituents are disassembled and recycled has not been established. To determine this, we monitored the fates of SNAP25 and synaptotagmin I after Ca2+-triggered exocytosis. Depolarization with high K+ buffers to stimulate Ca2+ influx and vesicle exocytosis promoted the progressive internalization of an N-terminal synaptotagmin I antibody (Figure 7C, left) indicative of compensatory endocytosis after exocytosis. Unlike SNAP25 internalization (see Figure 2B), stimulation-dependent synaptotagmin I antibody uptake was strongly inhibited by expression of the dynamin K44A mutant (Figure 7B, arrowheads), indicating it is mediated by dynamin-dependent endocytosis. Internalized synaptotagmin I antibody did exhibit colocalization with a subset of ARF6-positive endosomes (Figure 7C, arrowheads), which is consistent with a report that ARF6 may also regulate clathrin-dependent endocytosis at the synapse (Krauss et al., 2003).

To determine whether SNAP25 is cointernalized with synaptotagmin I after Ca2+ influx-evoked exocytosis, we monitored the distribution of SNAP25 in cells that internalized synaptotagmin I antibody. Cell surface staining by synaptotagmin I antibody initially colocalized with patches of SNAP25, which represent sites of exocytosis (Figure 7C, 5 min, arrows). Synaptotagmin I antibody internalized at later times (Figure 7C, 20 min), however, was clearly segregated from internalized SNAP25. These results imply that the SNAP25, present in SNARE complexes during exocytosis, is subsequently sorted from vesicle constituents such as synaptotagmin I in the plane of the plasma membrane before compensatory endocytosis. The ARF6-dependent SNAP25 internalization pathway seems to operate constitutively and is clearly distinct from the dynamin-dependent compensatory endocytic pathway that retrieves dense-core vesicle constituents after fusion.

DISCUSSION

SNAP25 Endocytosis by a Dynamin-independent, F-Actin-dependent Pathway

Although predominantly plasma membrane-localized, SNAP25 has also been variously localized to Golgi elements and cytoplasmic vesicles, secretory vesicles and transport vesicles (Oyler et al., 1989; Walch-Solimena et al., 1995; Duc and Catsicas, 1995; Gonzalo and Linder, 1998; Marxen et al., 1999; Tao-Cheng et al., 2000; Morgans and Brandstatter, 2000). It has generally been assumed that intracellular SNAP25 is a biosynthetic intermediate in anterograde traffic toward the plasma membrane but this seems unlikely. SNAP25 is a relatively stable protein (t1/2 ∼10 h), yet intracellular SNAP25 constitutes ∼20% of the total protein in PC12 cells, which indicates that a substantial intracellular pool is maintained at steady state. That expression of the GTP-bound ARF6Q67L mutant markedly enhanced intracellular SNAP25 at the expense of the plasma membrane pool (Aikawa and Martin, 2003) suggested that intracellular SNAP25 is actively maintained by endocytosis.

Plasma membrane protein internalization occurs by a number of endocytic pathways that have been categorized as clathrin dependent or clathrin independent (Conner and Schmid, 2003). Although the clathrin-dependent pathway is well characterized, a large number of distinct clathrin-independent pathways are less clearly defined (Nichols and Lippincott-Schwartz, 2001). Recent work identified a novel clathrin-independent endocytic pathway that internalizes proteins such as major histocompatibility complex I and interleukin-2 receptor α subunit (Radhakrishna and Donaldson, 1997; Brown et al., 2001; Naslavsky et al., 2003, 2004). Key features of this pathway are that it is clathrin and dynamin independent and regulated by ARF6. Our studies on SNAP25 internalization indicate that a similar pathway mediates the recycling of this protein between the plasma membrane and a recycling endosome-TGN pool in neuroendocrine cells.

Plasma membrane SNAP25 colocalized with ARF6 in membrane invaginations, and the internalization of SNAP25 was accelerated by expression of the constitutive active ARF6Q67L mutant. ARF6 recruits and activates PI(4)P 5-kinase I as an effector at the plasma membrane (Honda et al., 1999; Brown et al., 2001; Aikawa and Martin, 2003). The ARF6 activation of PIP2 synthesis in domains at the plasma membrane may be the key initiator of membrane invagination and pinching off of vesicles in this pathway. Indeed, we found that SNAP25 and PIP2 colocalized along with ARF6 in membrane domains and invaginations. Expression of the ARF6Q67L mutant in PC12 cells seemed to drive the unregulated accumulation of SNAP25 into PIP2-, ARF6-, and F actin-containing vacuoles (Brown et al., 2001) from which SNAP25 recycling was inhibited. Latrunculin A, an inhibitor of actin polymerization, blocked SNAP25 internalization and caused enlargement of ARF6-positive, PIP2-enriched plasma membrane invaginations that failed to pinch off or internalize. The synthesis of PIP2 is known to promote F-actin assembly at plasma membrane sites by binding directly to a variety of actin regulatory proteins and modulating their function (Botelho et al., 2000; Yin and Janmey, 2003). Thus, SNAP25 internalization may be driven by the ARF6-dependent activation of PI(4)P 5-kinase, the local synthesis of PIP2, and the nucleation of F-actin, leading to membrane invagination and the pinching off of tubulovesicular endosomes.

Specific Internalization of SNAP25 but Not Syntaxin-1A

The ARF6-dependent endocytic pathway that internalizes plasma membrane SNAP25 excludes syntaxin 1A. Although it was suggested that SNAP25 targeting to the plasma membrane requires association with its plasma membrane SNARE partner syntaxin 1A (Vogel et al., 2000; Washbourne et al., 2001), the correct plasma membrane targeting of SNAP25 can be achieved in the complete absence of syntaxin 1A (Rowe et al., 1999) or with SNAP25 constructs that do not interact with syntaxin 1A (Gonzalo et al., 1999; Loranger and Linder, 2002). At steady-state in the plasma membrane of PC12 cells, SNAP25, and syntaxin 1A are not extensively associated but are localized in distinct membrane domains (Vogel et al., 2000; Lang et al., 2001, 2002; Xiao et al., 2004).

The localization of SNAP25 to specific plasma membrane domains may be the basis for its segregation from syntaxin 1A and its selective endocytic recycling by the ARF6-dependent endocytic pathway. Dually palmitoylated membrane proteins partition into distinct sphingomyelin/cholesterol-rich membrane domains (Arni et al., 1998; Zacharias et al., 2002), and SNAP25 may similarly do so (Lang et al., 2001; Salaun et al., 2005). Cholesterol depletion was reported to disrupt plasma membrane clusters of SNAP25 (Lang et al., 2001). The possible selectivity of the ARF6-dependent endocytic mechanism for specific cholesterol-rich membrane domains was suggested by the finding that filipin, a cholesterol-binding polyene macrolide, inhibited the ARF6-dependent internalization pathway in HeLa cells without affecting the clathrin-dependent pathway (Naslavsky et al., 2004). If SNAP25 is resident in cholesterol-rich membrane domains, the cytoplasmic leaflet of these domains is likely to be enriched for PIP2 as indicated by our colocalization studies. This enrichment may be conferred by membrane anchoring of myristoylated ARF6 and its recruitment of PI(4)P 5-kinase (Honda et al., 1999) as well as by a type II PI 4-kinase, which is associated with raft domains by palmitoylation (Waugh et al., 1998; Barylko et al., 2001).

Kinetics of SNAP25 Recycling Pathway

FRAP studies determined that the rate constant for SNAP25 internalization of 0.44% min-1 was increased to 1.5% min-1 in cells expressing the constitutively active ARF6Q67L mutant. These values are similar to those recently reported for the uptake of surface proteins in HeLa cells by an ARF6-regulated pathway (Naslavsky et al., 2004). The FRAP analysis of the kinetics of SNAP25 recycling provided insights into the internalization and recycling mechanisms of the ARF6-regulated pathway. The inhibition of SNAP25 internalization by latrunculin A treatment (Figure 2F) was entirely accounted for (R2 = 0.975) by the kinetics of recycling, which supports the conclusion that SNAP25 internalization pathway is entirely dependent upon F-actin assembly at the plasma membrane, which may represent a general feature of the ARF6-regulated dynamin-independent pathway of endocytosis. Conversely, BFA-induced expansion of the intracellular SNAP25 pool (Figure 5E) was entirely accounted for (R2 = 0.953) by the rate constant for internalization. Whereas BFA does not inhibit ARF6 activation, it does inhibit ARF1 activation and the recruitment of coat proteins (Randazzo et al., 2000). Inhibition by BFA suggests that SNAP25 recycling back to the cell surface is mediated through a tubular endosomal recycling compartment that uses clathrin-coated buds (van Dam and Stoorvogel, 2002).

The basal rate for dynamin-independent SNAP25 internalization was slower than that of the clathrin-dependent endocytic pathway (rate constants 0.44 and 2–10% min-1, respectively; Mukherjee et al., 1997), but expression of the constitutively active ARF6Q67L mutant accelerated the rate of SNAP25 internalization approximately fourfold. The ARF6-regulated pathway could play a role in modulating plasma membrane SNAP25 levels through a multitude of characterized ARF6 GEF proteins such as mSec7 (Ashery et al., 1999). Endocytosis of plasma membrane SNAP25, especially in polarized regions such as neuronal synapses or dendrites, could render this SNARE protein rate limiting and thereby alter probabilities for vesicle exocytosis.

Potential Roles of SNAP25 Recycling

Our results documenting a constitutively active recycling pathway for SNAP25 raise the issue of what role recycling may play. The half-life of SNAP25 protein in PC12 cells is ∼10 h (Lane and Liu, 1997), which indicates that SNAP25 molecules will transit the recycling pathway approximately three times during their life span. Because the measured half-life of palmitate on SNAP25 is ∼3 h (Lane and Liu, 1997), it is possible that the endocytic recycling of SNAP25 is coupled to a cycle of depalmitoylation and repalmitoylation. The putative SNAP25 palmitoyltransferase HIP14 exhibits a Golgi and cytoplasmic vesicle localization (Huang et al., 2004), which suggests that repalmitoylation of SNAP25 may occur during its recycling back to the plasma membrane as has been described for neuronal postsynaptic PSD-95 and presynaptic GAD65 (Smotrys and Linder, 2004). This would provide an attractive explanation for the finding that SNAP25 palmitoylation is blocked by BFA (Gonzalo and Linder, 1998). Our results indicate that BFA blocks the recycling of SNAP25 back to the plasma membrane (Figure 5E) and also promotes the conversion of SNAP25 from a membrane-associated to cytosolic form (Figure 5F). Conversion to a cytosolic form may result the cumulative depalmitoylation of SNAP25. Overall, the results are consistent with a possible cycle in which SNAP25 endocytosis is coupled to its depalmitoylation with recycling back to the plasma membrane coupled to its repalmitoylation.

A second possible role for SNAP25 internalization may be to target the protein to endosomal membranes where it may function as a SNARE protein in endosome fusion. Botulinum neurotoxin E, a protease that cleaves SNAP25 and certain isoforms of SNAP23, was reported to inhibit early endosome fusion in vitro (Sun et al., 2003). Our recent studies revealed that expression of botulinum neurotoxin E light chain in PC12 cells blocks the trafficking of SNAP25 as well as other endocytosed cargo to the perinuclear recycling endosome compartment (Aikawa, Lynch, Boswell, and Martin, unpublished data). A role for SNAP25 in endosome fusion would provide a functional rationale for the internalization pathway described in the current work.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to X. Zhang for contributing the expression plasmid encoding HA-tagged SNAP25, to J. Kowalchyk for some of the experimental work, and to R. Lance (Keck Biological Imaging Laboratory, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI) for help with the FRAP studies. This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service Grant DK25861 (to T.F.J.M.) and American Heart Association fellowship support (to X. X.).

This article was published online ahead of print in MBC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E05–05–0382) on November 28, 2005.

Abbreviations used: ARF, ADP-ribosylation factor; BFA, brefeldin A; CHX, cycloheximide; CTxB, cholera toxin B; FRAP, fluorescence recovery after photobleaching; GFP, green fluorescent protein; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; PIP2, phosphatidylinositol(4,5)bisphosphate; PI(4)P 5-kinase I, phosphatidylinositol(4)phosphate 5-kinase type I; SNAP25, synaptosome-associated protein of 25 KDa; SNARE, soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor; Tf, transferrin.

References

- Ahmari, S., Buchanan, J., and Smith, S. (2000). Assembly of presynaptic active zones from cytoplasmic transport packets. Nat. Neurosci. 3, 445-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aikawa, Y., and Martin, T.F.J. (2003). ARF6 regulates a plasma membrane pool of phosphatidylinositol (4,5) bisphosphate required for regulated exocytosis. J. Cell Biol. 162, 647-659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arni, S., Keilbaugh, S., Ostermeyer, A., and Brown, D. (1998). Association of GAP-43 with detergent-resistant membranes requires two palmitoylated cysteine residues. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 28478-28485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashery, U., Koch, H., Scheuss, V., Brose, N., and Rettig, J. (1999). A presynaptic role for the ADP ribosylation factor-specific GDP/GTP exchange factor msec7–1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 1094-1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, A., Kowalchyk, J. A., DasGupta, B. R., and Martin, T.F.J. (1996). SNAP25 is required for a late postdocking step in Ca2+-dependent exocytosis. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 20227-20230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barylko, B., Gerber, S., Binns, D., Grichine, N., Khvotchev, M., Sudhof, T., and Albanesi, J. (2001). A novel family of phosphatidylinositol 4-kinases conserved from yeast to humans. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 7705-7708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock, J. B., Matern, H. T., Peden, A. A., and Scheller, R. H. (2001). A genomic perspective on membrane compartment organization. Nature 409, 839-841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botelho, R. J., Teruel, M., Dierckman, R., Anderson, R., Wells, A., York, J. D., Meyer, T., and Grinstein, S. (2000). Localized biphasic changes in phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate at sites of phagocytosis. J. Cell Biol. 151, 1353-1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, F. D., Rozelle, A. L., Yin, H. L., Balla, T., and Donaldson, J. G. (2001). Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate and ARF6-regulated membrane traffic. J. Cell Biol. 154, 1007-1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burri, L., and Lithgow, T. (2004). A complete set of SNAREs in yeast. Traffic 5, 45-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. A., and Scheller, R. H. (2001). SNARE-mediated membrane fusion. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2, 98-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheever, M. L., Sato, T. K., deBeer, T., Kutateladze, T. G., Emr, S. D., and Overduin, M. (2001). Phox domain interaction with PtdIns(3)P targets the Vam7 t-SNARE to vacuole membranes. Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 613-618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner, S., and Schmid, S. (2003). Regulated portals of entry into the cell. Nature 422, 37-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damke, H., Baba., T., Warnock., D. E., and Schmid, S. L. (1994). Induction of mutant dynamin specifically blocks endocytic vesicle formation. J. Cell Biol. 127, 915-934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaney, K. A., Murph, M. M., Brown, L. M., and Radhakrishna, H. (2002). Transfer of M2 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors to clathrin-derived early endosomes following clathrin-independent endocytosis. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 33439-33446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Souza-Schorey, C., Boshans, R. L., McDonough, M., Stahl, P. D., and Van Aelst, L. (1997). A role for POR1, a Rac1-interacting protein, in ARF6-mediated cytockeletal rearrangements. EMBO J. 16, 5445-5454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Souza-Schorey, Li, G., Columbo, M. I., and Stahl, P. D. (1995). A regulatory role for ARF6 in receptor-mediated endocytosis. Science 267, 1175-1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duc, C., and Catsicas, S. (1995). Ultrastructural localization of SNAP25 within the rat spinal cord and peripheral nervous system. J. Comp. Neurol. 356, 152-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, R. N., Mallet, W. G., Soe, T. T., McGraw, T. E., and Maxfield, F. R. (1998). An endocytosed TGN38 chimeric protein is delivered to the TGN after trafficking through the endocytic recycling compartment in CHO cells. J. Cell Biol. 142, 923-936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalo, S., Greentree, W. K., and Linder, M. E. (1999). SNAP25 is targeted to the plasma membrane through a novel membrane-binding domain. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 21313-21318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalo, S., and Linder, M. E. (1998). SNAP25 palmitoylation and plasma membrane targeting required for a functional secretory pathway. Mol. Bio. Cell 9, 585-597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henkel, A. W., Horstmann, H., and Henkel, M. K. (2001). Direct observation of membrane retrieval in chromaffin cells by capacitance measurements. FEBS. Let. 505, 414-418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess, D., Slater, T., Wilson, M., and Skene, J. (1992). The 25kDa synaptosomal-associated protein SNAP25 is the major methionine-rich polypeptide in rapid axonal transport and a major substrate for palmitoylation in adult CNS. J. Neurosci. 12, 4634-4641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda, K., et. al. (1999). Phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinase alpha is a downstream effector of the small G. protein ARF6 in membrane ruffle formation. Cell 99, 521-532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, K., et al. (2004). Huntingtin-interacting protein HIP14 is a palmitoyl transferase involved in palmitoylation and trafficking of multiple neuronal proteins. Neuron 44, 977-986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahn, R., Lang, T., and Sudhof, T. C. (2003). Membrane fusion. Cell 112, 519-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krauss, M., Kinuta, M., Wenk, M. R., De Camilli, P., Takei, K., and Haucke, V. (2003). ARF6 stimulates clathrin/AP-2 recruitment to synaptic membranes by activating phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase type Iγ. J. Cell Biol. 162, 113-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutay, U., Ahnert-Hilger, G., Hartmann, E., Wiedenmann, B., and Rapoport, T. (1995). Transport route for synaptobrevin via a novel pathway of insertion into the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. EMBO J. 14, 217-223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane, S., and Liu, Y. (1997). Characterization of the palmitoylation domain of SNAP25. J. Neurochem. 69, 1864-1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang, T., Bruns, D., Wenzel, D., Riedel, D., Holroyd, P., Thiele, C., and Jahn, R. (2001). SNAREs are concentrated in cholesterol-dependent clusters that define docking and fusion sites for exocytosis. EMBO J. 20, 2202-2213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang, T., Margittai, M., Holzer, H., and Jahn, R. (2002). SNAREs in native plasma membranes are active and readily form core complexes with endogenous and exogenous SNAREs. J. Cell Biol. 158, 751-760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippincott-Schwartz, J., Yuan, L., Tipper, C., Amherdt, M., Orci, L., and Klausner, R. (1991). Brefeldin A's effect on endosome, lysosomes, and the TGN suggest a general mechanism for regulating organelle structure and membrane traffic. Cell 67, 601-616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.-Y., Jahn, R., and Dahlstrom, A. (1996). Axonal transport and targeting of the t-SNAREs SNAP25 and syntaxin 1 in the peripheral nervous system. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 70, 12-22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loranger, S. S., and Linder, M. E. (2002). SNAP25 traffics to the plasma membrane by a syntaxin-independent mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 34303-34309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Arca, S., et al. (2003). A dual mechanism controlling the localization and function of exocytic v-SNAREs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 9011-9016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marxen, M., Volknandt, W., and Zimmerman, H. (1999). Endocytic vacuoles formed following a short pulse of K+-stimulation contain a plethora of presynaptic membrane proteins. Neuroscience 94, 985-996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNew, J. A., Parlati, F., Fukuda, R., Johnston, R. J., Paz, K., Paument, F., Sollner, T. H., and Rothman, J. E. (2000). Compartmental specificity of cellular membrane fusion encoded in SNARE proteins. Nature 407, 153-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgans, C., and Brandstatter, J. H. (2000). SNAP25 is present on the Golgi apparatus of retinal neurons. Neuroreport 11, 85-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, S., Ghosh, R. N., and Maxfield, F. R. (1997). Endocytosis. Physiol. Rev. 77, 759-803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakata, T., Terada, S., and Hirokawa, N. (1998). Visualization of the dynamic synaptic vesicle and plasma membrane proteins in living axons. J. Cell Biol. 140, 659-674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naslavsky, N., Weigert, R., and Donaldson, J. G. (2003). Convergence of non-clathrin- and clathrin-derived endosomes involves Arf6 inactivation and changes in phosphoinositides. Mol. Biol. Cell. 14, 417-431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naslavsky, N., Weigert, R., and Donaldson, J. G. (2004). Characterization of a nonclathrin endocytic pathway: membrane cargo and lipid requirements. Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 3542-3552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols, B. J., Kenworthy, A. K., Polishchuk, R. S., Lodge, R., Roberts, T. H., Hirschberg, K., Phair, R. D., and Lippincott-Schwartz, J. (2001). Rapid recycling of lipid raft markers between the cell surface and Golgi complex. J. Cell Biol. 153, 529-541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols, B. J., and Lippincott-Schwartz, J. (2001). Endocytosis without clathrin coats. Trends Cell Biol. 11, 406-412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyler, G. A., Higgins, G. A., Hart, R. A., Battenberg, E., Billingsley, M., Bloom, F. E., and Wilson, M. C. (1989). The identification of a novel synaptosomal-associated protein, SNAP25, differentially expressed by neuronal subpopulations. 109, 3039-3052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patzak, A., and Winkler, H. (1986). Exocytotic exposure and recycling of membrane antigens of chromaffin granules: ultrastructure evaluation after immunolabelling. J. Cell Biol. 102, 510-515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters, P. J., Hsu, V. W., Ooi, C. E., Finazzi, D., Teal, S. B., Oorschot, V., Donaldson, J. G., and Klausner, R. D. (1995). Overexpression of wild-type and mutant ARF1 and ARF 6, distinct perturbations of nonoverlapping membrane compartments. J. Cell Biol. 128, 1003-1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prekeris, R., Klumperman, J., Chen, Y. A., and Scheller, R. H. (1998). Syntaxin 13 mediates cycling of plasma membrane proteins via tubulovesicular recycling endosomes. J. Cell Biol. 143, 957-971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radhakrishna, H., Al-Awar, O., Khachikian, Z., and Donaldson, J. G. (1999). ARF6 requirement for Rac ruffling suggests a role for membrane trafficking in cortical actin rearrangements. J. Cell. Sci. 112, 855-866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radhakrishna, H., and Donaldson, J. G. (1997). ADP-ribosylation factor 6 regulates a novel plasma membrane recycling pathway. J. Cell Biol. 139, 49-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randazzo, P. A., Nie, Z., Miura, K., and Hsu, V. W. (2000). Molecular aspects of the cellular activities of ADP-ribosylation factors. Sci. STKE 2000, re1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reaves, B., Horn, M., and Banting, G. (1993). TGN38/41 recycles between the cell surface and the TGN: brefeldin A affects its rate of return to the TGN. Mol. Biol. Cell 4, 93-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, M. S., and Kreis, T. E. (1992). Recruitment of coat proteins onto Golgi membranes in intact and permeabilized cells: effects of brefeldin A and G protein activators. Cell 69, 129-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, J., Corradi, N., Malosio, M., Taverna, E., Halban, P., Meldolesi, J., and Rosa, P. (1999). Blockade of membrane transport and disassembly of the Golgi complex by expression of syntaxin 1A in neurosecretion-incompetent cells. J. Cell Sci. 112, 1865-1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salaun, C., Gould, G. W., and Chamberlain, L. H. (2005). The SNARE proteins SNAP25 and SNAP23 display different affinities for lipid rafts in PC12 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 1236-1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scales, S. J., Chen, Y. A., Yoo, B. Y., Patel, S. M., Doung, Y.-C., and Scheller, R. H. (2000). SNAREs contribute to the specificity of membrane fusion. Neuron 26, 45-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smotrys, J., and Linder, M. (2004). Palmitoylation of intracellular signaling proteins: regulation and function. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 73, 559-587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sollner, T., Bennet, M. K., Whiteheart, S. W., Scheller, R. H., and Rothman, J. E. (1993). A protein assembly-disassembly pathway in vitro that may correspond to sequential steps of synaptic vesicle docking, activation, and fusion. Cell. 75, 409-418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenmark, H., Parton, R. G., Steele-Mortimer, O., Lutcke, F., Gruenberg, J., and Zerial, M. (1994). Inhibition of rab5 GTPase activity stimulates membrane fusion in endocytosis. EMBO J 13, 1287-1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, W., Yan, Q., Vida, T. A., and Bean, A. J. (2003). Hrs regulates early endosome fusion by inhibiting formation of an endosomal SNARE complex. J. Cell Biol. 162, 125-137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao-Cheng, J. H., Du, J., and McBain, C. J. (2000). SNAP25 is polarized to axons and abundant along the axolemma: an immunogold study of intact neurons. J. Neurocytol. 29, 67-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungar, D., and Hughson, F. M. (2003). SNARE protein structure and function. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 19, 493-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dam, E., and Stoorvogel, W. (2002). Dynamin-dependent transferring receptor recycling by endosome-derived clathrin-coated vesicles. Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 169-182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, K., Cabaniols, J.-P., and Roche, P. (2000). Targeting of SNAP25 to membranes is mediated by its association with the target SNARE syntaxin. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 2959-2965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walch-Solimena, C., Blasi, J., Edelmann, L., Chapman, E. R., von Mollard, G. F., and Jahn, R. (1995). The t-SNAREs syntaxin 1 and SNAP25 are present on organelles that participate in synaptic vesicle recycling. J. Cell Biol. 128, 637-645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washbourne, P., Cansino, V., Mathews, J., Graham, M., Burgoyne, R., and Wilson, M. (2001). Cysteine residues of SNAP25 are required for SNARE disassembly and exocytosis but not for membrane targeting. Biochem. J. 357, 625-634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waugh, M., Lawson, D., Tan, S., and Hsuan, J. (1998). Phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate synthesis in immunoisolated caveolae-like vesicles and low buoyant density non-caveolar membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 17115-17121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber, T., Zemelman, B. V., McNew, J. A., Westermann, B., Gmachl, M., Parlati, F., Sollner, T. H., and Rothman, J. E. (1998). SNAREpins: minimal machinery for membrane fusion. Cell 92, 759-772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, J., Xia, Z., Pradhan, A., Zhou, Q., and Liu, Y. (2004). An immunohistochemical method that distinguishes free from complexed SNAP25. J. Neurosci. Res. 75, 143-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin, H. L., and Janmey, P. A. (2003). Phosphoinositide regulation of the actin cytoskeleton. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 65, 761-789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacharias, D., Violin, J., Newton, A., and Tsien, R. (2002). Partitioning of lipid-modified monomeric GFPs into membrane microdomains of live cells. Science 296, 913-916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerial, M., and McBride, H. (2001). Rab proteins as membrane organizers. Nature Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2, 107-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, R. G., Vardinon-Friedman, H., Cases-Langhoff, C., Becker, B., Gundelfinger, E. D., Ziv, N. E., and Garner, C. C. (2001). Assembling the presynaptic active zone: a characterization of an active zone precursor vesicle. Neuron 29, 131-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X., Kim-Miller, M. J., Fukuda, M., Kowalchyk, J. A., and Martin, T.F.J. (2002). Ca2+-dependent synaptotagmin binding to SNAP25 is essential for Ca2+-triggered exocytosis. Neuron 34, 599-611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]