Abstract

Summary Background Data:

We compare the results of liver resection performed under in situ hypothermic perfusion versus standard total vascular exclusion (TVE) of the liver <60 minutes and ≥60 minutes in terms of liver tolerance, liver and renal functions, postoperative morbidity, and mortality. The safe duration of TVE is still debated. Promising results have been reported following TVE associated with hypothermic perfusion of the liver with durations of up to several hours. The 2 techniques have not been compared so far.

Methods:

The study population includes 69 consecutive liver resections under TVE <60 minutes (group TVE<60′, 33 patients), ≥60 minutes (group TVE≥60′, 16 patients), and in situ hypothermic perfusion (group TVEHYOPOTH, 20 patients). Liver tolerance (peaks of transaminases), liver and kidney function (peak of bilirubin, minimum prothrombin time, and peak of creatinine), morbidity, and in-hospital mortality were compared within the 3 groups.

Results:

The postoperative peaks of aspartate aminotransferase (IU/L) and alanine aminotransferase (IU/L) were significantly lower (P[r] < 0.05) in group TVE HYPOTH (450 ± 298 IU/L and 390 ± 391 IU/L) compared with the groups TVE<60′ (1000 ± 808; 853 ± 743) and TVE≥60′ (1519 ± 962; 1033 ± 861). In the group TVEHYPOTH, the peaks of bilirubin (μmol/L) (84 ± 31), creatinine (μmol/L) (75 ± 22), and the number of complications per patient (1.2 ± 0.9) were comparable to those of the group TVE<60′ (80 ± 111; 109 ± 77; and 0.8 ± 1.1 respectively) and significantly lower to those of the group TVE≥60′ (196 ± 173; 176 ± 176, and 2.6 ± 1.8). In-hospital mortality rates were 1 in 33, 2 in 16, and 0 in 20 for the groups TVE<60′, TVE≥60′, and TVEHYOPOTH, respectively, and were comparable. On multivariate analysis, the size of the tumor, portal vein embolization, and a planned vascular reconstruction were significantly predictive of TVE ≥60 minutes.

Conclusions:

Compared with standard TVE of any duration, hypothermic perfusion of the liver is associated with a better tolerance to ischemia. In addition, compared with TVE ≥60 minutes, it is associated with better postoperative liver and renal functions and a lower morbidity. Predictive factors for TVE ≥60 minutes may help to indicate hypothermic perfusion of the liver.

Liver resection under total vascular exclusion (TVE) with in situ hypothermic perfusion of the liver, compared with standard TVE, was followed by significantly better tolerance to ischemia, better liver and renal function, and lower morbidity. These results were obtained despite significantly longer ischemia time and much more complex procedures.

Total vascular exclusion of the liver (TVE), including the clamping of the portal triad, the vena cava above and below the liver, is indicated for tumors involving or adjacent to the vena cava and/or to the confluence of the hepatic veins into the latter. Whereas the safe time limit of the liver tolerance to TVE is still debated, 60 minutes seems a reasonable one. The adjunction of hypothermic perfusion of the liver has been reported to prolong safely the vascular exclusion up to several hours. The benefit of resection under hypothermic perfusion of the liver over standard TVE remains to be shown. The aim of the present study was to compare the results of TVE with in situ hypothermic perfusion of the liver to those of TVE <60 minutes and TVE ≥60 minutes in terms of postoperative liver tolerance, liver function, kidney function, in-hospital mortality, and morbidity. In a second step, the predictive factors for TVE ≥60 minutes were evaluated by univariate and multivariate analysis.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

From 1997 to 2003, 1138 consecutive hepatectomies were performed at our center, including 162 (14%) under vascular exclusion: 93 (8%) without clamping of the vena cava and 69 (6%) with clamping of the vena cava, including TVE <60 minutes, ≥60 minutes, and in situ hypothermic perfusion in 33 (group TVE <60′), 16 (group TVE≥60′), and 20 (group TVEHYPOTH) patients, respectively. These 69 consecutive cases of liver resection under TVE without or with in situ hypothermic perfusion of the liver form the population of the present study. In situ hypothermic perfusion of the liver was applied when the planned procedure included a vascular reconstruction, potentially prolonging beyond 1 hour of the TVE already indicated for the resection per se. Vascular reconstruction was considered by 4 senior surgeons together (HB, DC, RA, and DA) upon the evaluation of systematic preoperative ultrasonography, CT scan, and NMR.

Preoperative Management

All patients operated on for malignant disease were screened as indicated to exclude extrahepatic disease. Portal vein embolization was indicated and performed as already described in details elsewhere.1,2 This was performed in 3 of 33, 4 of 16, and 8 of 20 cases in group TVE<60′, group TVE≥60′, and group TVEHYPOTH, respectively.

Anesthetic Management

Intraoperative monitoring included the standard noninvasive techniques. In addition, a Swann-Ganz catheter and an arterial line were systematically used.

Surgical Techniques

TVE of the Liver Including Clamping of the Vena Cava

TVE was the common first step for all 3 groups after systematic intraoperative ultrasonography.3–5 In the groups TVE<60′ and TVE≥60′, a veno-venous bypass (see below) was installed in case of hemodynamic intolerance.6 This occurred in 4 of 33 cases of group TVE<60′ and 5 of 16 cases of group TVE≥60′.

In Situ Hypothermic Perfusion of the Liver

In situ hypothermic perfusion of the liver was performed according to the technique described by Fortner et al,7 with some modifications. A veno-venous bypass was systematically installed.8–10 Following TVE and veno-venous bypass, the portal vein was catheterized above the portal triad clamp, and UW solution chilled at 4°C was used for in situ hypothermic perfusion of the liver. The volume of infusion ranged from 2 to 4 L. A cavotomy was made immediately above the inferior caval clamp for placement of a 30 French catheter to drain the perfusate. The liver temperature was measured in the last 5 patients by deeply (44 mm) inserting into the future remnant liver the probe of a Thermister thermometer (Medtronic, Paris, France). This showed a drop in the liver temperature to 13°C to 21°C (median = 16°C). When liver resection and vascular reconstruction when indicated were completed, the liver was flushed with serum albumin (300 to 500 mL) via the portal vein. Circulation was restored as for TVE.

Vascular Reconstructions

Some form of vascular reconstruction was planned in 2, 3, and 20 cases in groups TVE<60′, TVE≥60′, and TVEHYPOTH, respectively. The vascular reconstruction was anticipated to be or not to be feasible after revascularization of the remnant liver in 2, 0, and 0 cases and in 0, 3, and 20 cases, respectively (see below). The retrohepatic IVC was resected and replaced by a 20-mm ringed polytetrafluoroethylene graft in 2 cases in each of the 3 groups. In the group TVE<60′, it was possible to leave a sufficient IVC stump below the confluence of the hepatic veins. This allowed us to replace the suprahepatic caval clamp by another one below the confluence of the hepatic veins. En bloc resection of the specimen and of the vena cava and caval reconstruction could thus be completed whereas the remnant liver had been revascularized. In the groups TVE≥60′, and TVEHYPOTH, replacement of the vena cava could not proceed this way and was performed under TVE of the liver.

The confluence of the 3 hepatic veins into the vena cava was resected in 7 patients from group TVEHYPOTH. In these 7 cases, there were only 1 or 2 hepatic vein tributaries from the main corresponding vein (ie, the left and right hepatic vein in 4 and 3 cases respectively) on the raw surface of the liver. The stump was reimplanted into the native vena cava in 6 cases and into a replaced vena cava in 1 case. Where there were 2 venous tributaries in the raw surface of the remnant liver, these were combined to form a common stump to be anastomosed to the vena cava, as already described.11 No graft was interposed between the hepatic veins tributaries and the native or the prosthetic vena cava.

In one TVE≥60′ patient, about 30° of the circumference of a remaining left hepatic vein was resected; it was repaired with a simple suture technique using 6–0 Prolene suture, without resorting to a patch repair.

The bifurcation of the portal vein was resected in 2 TVEHYPOTH patients. The remaining right branch or right posterior branch of the portal vein was anastomosed end to end to the portal trunk.

Additional Hepatic Procedures

Twenty-two additional nonanatomic resections were performed on the remnant liver in 8 TVE<60′, 5 TVE≥60′, and 4 TVEHYPOTH patients.

Extrahepatic Procedure

Four TVE<60′ and 5 TVEHYPOTH patients underwent the following 10 combined extrahepatic procedures: resection of the diaphragm (6 cases), pericardium (1 case), right adrenal gland (1 case), a small bowel loop (1 case), and the rectum (1 case).

Postoperative Management

Postoperative monitoring included the standard techniques. All the patients were systematically followed in ICU for 24 hours and transferred to the wards as soon as possible. Blood samples were obtained daily until day 7 and then when indicated by the clinical situation. Blood sample was obtained systematically the day of discharge and day 30.

Definition of Postoperative Complications

Patients were defined as having postoperative liver insufficiency when at least 2 of the following parameters were observed concurrently: total bilirubin ≥60 μmol/L, prothrombin time ≤30% of normal level, massive ascites (abdominal drain output >500 mL per day during more than 3 days). Asterixis and alteration of consciousness after exclusion of drug effect were considered as signs of liver failure, even when isolated. Other complications looked for included the need for reoperation, biliary fistula, massive ascites, renal insufficiency defined as serum creatinine >150 μmol/L, infection defined as a the presence of a temperature ≥38.5°C, a white blood cell count ≥10 × 1010/L, and either positive blood cultures or a documented septic focus.

Data Analysis

Results are given as mean ± SD. Continuous variables included age (years), number of courses of preoperative chemotherapy, number of nodules, maximal diameter of the largest nodule, number of liver segments planned to be resected according to Couinaud,12 preoperative levels of prothrombin (percentage of normal level), bilirubin (μmol/L), alanine aminotransferase (ALAT) (IU/L), aspartate aminotransferase (ASAT) (IU/L), indocyanine green retention rate at 15 minutes (ICG-R15), creatinine (μmol/L). Categorical variables included sex, indication for hepatectomy (benign versus malignant disease), planned vascular reconstruction, portal vein embolization. Intraoperative continuous variables included the duration of TVE (min), the actual number of segments resected, the specimen weight (g), the transfusion volume (units of blood, units of plasma). Categorical variables included vascular reconstruction subdivided into those performed during or after liver reperfusion, veno-venous bypass, combined resection in the remnant liver, combined extrahepatic procedure. During the postoperative period, the liver tolerance to TVE was assessed by the peaks of ASAT and ALAT. The postoperative liver function was assessed by the peak of bilirubin, and the minimal level of PT. The postoperative renal function was assessed by the peak of creatinine. ANOVA analysis, when indicated, was performed and allowed repeated t tests (data not shown).

To be clinically relevant, only data available before surgery and potentially predictive of TVE ≥60 minutes were assessed by univariate analysis. If significantly correlated with this end point, they were evaluated in the Cox proportional hazard model, using forward stepwise selection to identify independent predictive factors. Risk ratios (RRs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. A P value < 0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

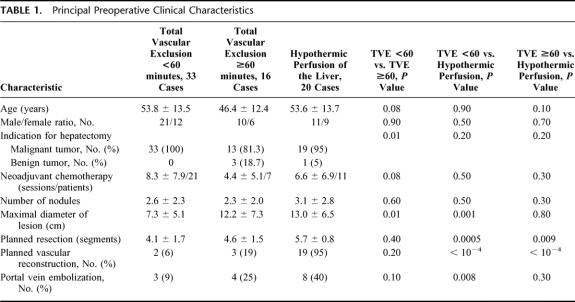

Preoperatively (Table 1), the 3 groups were comparable in all aspects, including age, sex distribution, the number of sessions of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, the number of liver nodules, and the liver and kidney function tests (data not shown). However, the number of benign tumors and the maximal diameter of the lesion were significantly higher in the group TVE≥60′ compared with the group TVE<60′ (P = 0.01 and 0.01, respectively). Only 1 patient (in group TVEHYPOTH) had a cirrhotic liver. The number of segments planned to be resected, the number of planned vascular reconstructions, and the number of portal vein embolizations were comparable in these 2 groups (P = 0.4, 0.2, and 0.1 respectively). On the other hand the maximal diameter of the lesion was comparable in groups TVE≥60′ and TVEHYPOTH (P = 0.8) whereas the number of segments planned to be resected was significantly higher in group TVEHYPOTH compared with the group TVE≥60′ (P = 0.09). The numbers of segments planned to be resected, vascular reconstructions, portal vein embolizations, and the maximal diameter of the largest nodule were significantly higher in the group TVEHYPOTH compared with the group TVE<60′.

TABLE 1. Principal Preoperative Clinical Characteristics

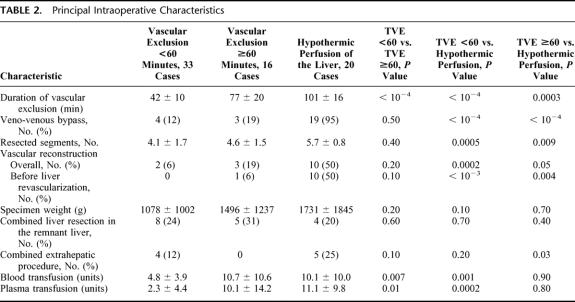

Intraoperative Characteristics (Table 2).

TABLE 2. Principal Intraoperative Characteristics

Compared with group TVE≥60′, the group TVE<60′ had a significantly shorter ischemia time (P <10−4), a lower number of transfused blood units (P = 0.007) and plasma units (P = 0.01). The 2 groups were comparable in all other intraoperative characteristics, including the number of cases of veno-venous bypass, vascular reconstructions, and the number of segments actually resected.

The comparison of group TVE≥60′ versus group TVEHYPOTH revealed that patients in the latter group underwent much extensive procedures with a longer ischemia time (P <0.001), a higher number of segments resected (P <0.009), and a higher number of vascular reconstructions before liver revascularization. Nevertheless, the transfusion volumes were comparable in both groups.

Intraoperative Complications

Veno-venous bypass was stopped in 1 patient of group TVEHYPOTH due to hemomediastinum and blood extravasation into the left pleura secondary to malposition of the left jugular catheter. However, after a chest tube was inserted into the left pleura, the resection was completed. The postoperative course of this patient was uneventful.

One patient in group TVE≥60′ operated on for angioma (duration of tVE = 120 minutes) presented a massive hemorrhage upon revascularization of the remnant right liver. He received 44 blood units and 50 plasma units. Hemostasis was achieved with prolonged compression of the raw surface of the liver and rewarming by pooling hot serum into the peritoneal cavity. The patient was discharged 32 days after hepatectomy with an external biliary fistula that never healed. He died 9 months after surgery from aspiration pneumonia. One patient in group TVEHYPOTH experienced massive hemorrhage upon revascularization of the liver. He received 42 blood units and 39 plasma units. Despite rewarming and compression of the raw surface, hemostasis could not be achieved until the abdomen was closed with a perihepatic packing. The patient was reoperated 3 days later for unpacking and had uneventful recovery.

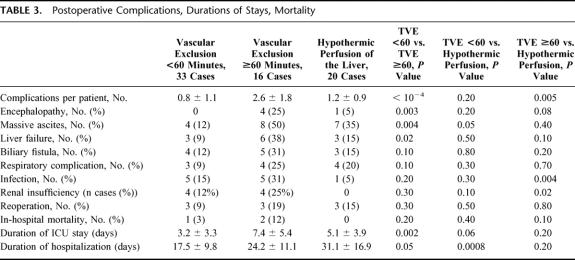

In-Hospital Mortality, Morbidity, Durations of ICU and Hospital Stay, and Cost Analysis

One patient in group TVE<60′ (3%) died. This patient had a right hepatectomy extended to segments 1 and 4 for colorectal metastases under TVE = 57 minutes. The patient developed liver failure, massive infected ascites, and renal failure. He died of sepsis on day 38. Two patients died in the group TVE≥60′ (12.5%). The first patient had resection of a central angioma with 60 minutes of TVE. Extensive bowel resection was performed on day 6 for necrotizing enterocolitis. No intestinal vascular thrombosis was found. She died of sepsis and multiple organ failure 7 months following surgery. A second patient died of sepsis 12 days following right hepatectomy for recurrent cholangiocarcinoma needing vascular exclusion during 70 minutes. In-hospital mortality was nil in the group TVEHYPOTH.

In-hospital mortality was comparable in the 3 groups. However, there was a trend towards higher mortality in the group TVE≥60′ compared with the group TVEHYPOTH (P = 0.1).

The number of complications per patient was significantly higher in group TVE≥60′ than in group TVE<60′ and group TVEHYPOTH (2.6 ± 1.8 versus 0.8 ± 1.1, P <10−4, and versus 1.2 ± 0.9, P = 0.005 respectively; Table 3). The number of complications per patient was comparable in groups TVE<60′ and TVEHYPOTH (P = 0.2). The incidence of encephalopathy, massive ascites, and liver failure was significantly higher in group TVE≥60′ than in group TVE<60′.

TABLE 3. Postoperative Complications, Durations of Stays, Mortality

Duration of ICU stay was significantly shorter for the group TVE<60′ (3.2 ± 3.3 days) than for the group TVE≥60′ (7.4 ± 5.4 days, P = 0.002).

The duration of total hospitalization stay for the group TVE≥60′ (24.2 ± 11.1 day) was not statistically different when compared with the groups TVE<60′ (17.5 ± 9.8 days, P = 0.05) and TVEHYPOTH (31.1 ± 16.9 days, P = 0.2). This duration was significantly shorter for the group TVE<60′ compared with the group TVEHYPOTH (P <10−3).

Patients of group TVE<60′ incurred significantly lower total charges (Euros 23, 714 ± 13, 026) than did patients of groups TVE≥60′ (Euros 36, 946 ± 16, 985, P = 0.01) and TVEHYPOTH (Euros 41,336 ± 15, 741, P = 0.0002). Total charges for groups TVE≥60′ and TVEHYPOTH were comparable (P = 0.5).

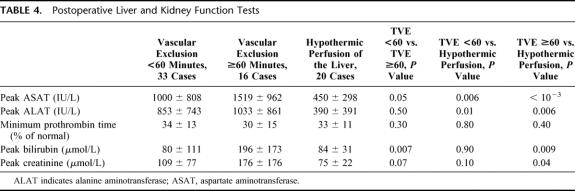

Liver Tolerance to Ischemia

The peaks of transaminases were significantly lower in group TVEHYPOTH compared with the 2 other groups. There was a trend towards lower peaks in groups TVE<60′ compared with the group TVE≥60′, but the difference did not reach statistical significance (Table 4).

TABLE 4. Postoperative Liver and Kidney Function Tests

Impact of Liver Ischemia on Liver and Renal Function Tests (Table 4)

The peak of bilirubin in groups TVE<60′ and TVEHYPOTH were comparable, and both were significantly lower than for group TVE≥60′. The minimal values of PT were comparable in the 3 groups.

The peak of creatinine was significantly lower in group TVEHYPOTH than in group TVE≥60′ and comparable to the one in group TVE<60′. Finally, there was a trend towards a lower peak of creatinine in group TVE<60′ compared with group TVE≥60′; however, this did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.1).

Factors Associated With Vascular Exclusion ≥60 Minutes

Among the data available before surgery, univariate analysis identified 5 factors associated with vascular exclusion ≥60 minutes: maximum diameter of tumor (P = 0.0007), the indication of hepatectomy for benign tumor (P = 0.04), preoperative portal vein embolization (P = 0.01), the number of segments planned to be resected (P = 0.005), and a planned vascular reconstruction (P <10−4). There was no significant influence of the age (P = 0.3), the number of nodules (P = 0.9), ICG-R15 (P = 0.2), the preoperative levels of prothrombin time (P = 0.6), bilirubin (P = 0.7), transaminases (ASAT: P = 0.1; and ALAT: P = 0.2).

The logistic regression model showed that vascular exclusion ≥60 minutes was associated with the maximum diameter of the lesion (P = 0.001; RR = 1.2; 95% CI: 1.0–1.3), portal vein embolization (P = 0.02; RR = 7.9; 95% CI: 1.4–46), and a planned vascular reconstruction (P = 0.01; RR = 16.8; 95% CI: 3–93).

DISCUSSION

This is the first study that underlines that hypothermic perfusion of the liver is followed by a significantly better tolerance to ischemia, a better liver function, and, more importantly, a significantly lower number of complications per patients compared with standard TVE ≥60. The results obtained with hypothermic perfusion of the liver are comparable to or even better than those obtained following liver resection under TVE <60 minutes. The larger size of the tumor, a preoperative portal vein embolization, and a planned vascular reconstruction are predictive for TVE ≥60 minutes.

Resection under TVE for tumors adjacent to or involving the vena cava and/or the confluence of the hepatic veins prevents the risks of both air embolism and hemorrhage, which impacts on short-term prognosis for all patients13–15 and long-term prognosis for cancer patients.16,17 Nevertheless, we agree with others18,19 that TVE is rarely necessary, and the present series represents only 6% of the total number of liver resections performed in our center during the same period. As our center works mainly as a tertiary-care facility for referring hospitals, this percentage of mandatory TVE for liver resection would probably even be lower in a nonselected population. The technique of TVE, including control of the supraceliac aorta, was first reported in 1966 by Heaney et al.20 In the 1980s, Huguet et al4 and Bismuth et al5 demonstrated that TVE, without aortic clamping, could be performed safely with acceptable mortality and morbidity. The duration of TVE that a healthy liver can safely tolerate varies among series, ranging from 30 minutes to 120 minutes.4,5,18,21–29 In our series, when comparing TVE <60 to TVE ≥60 minutes, the latter was associated with significantly higher volumes of transfusion (blood and plasma) and a higher peak of postoperative bilirubin. More importantly, for comparable patients (Table 1) and comparable procedures (Table 2), the numbers of complications per patient, including the incidence of encephalopathy, massive ascites, and liver failure (Table 3), and duration of ICU stay were significantly higher for the group TVE≥60′ compared with the group TVE<60′. Our 60-minute cutoff is shorter than in others series.21,22,24 This might be due to the fact that 28 of 46 patients (61%) with a malignant disease had received a preoperative heavy chemotherapy (Table 1), which is known to be a major risk factor of postoperative liver failure.30,31 In addition 11 of 16 (70%) patients of this group TVE≥60′ had in fact a duration of TVE ≥70 minutes.

Some liver resections require to be performed under TVE during much more than 1 hour to achieve parenchymal division per se and/or combined vascular reconstruction. In these cases, hypothermic perfusion of the liver has been proposed to prolong vascular ischemia up to several hours.32,33 In the group TVEHYOPTH, the vascular exclusion lasted ≥90 minutes in 17 of 20 cases (85%). Hypothermia diminishes the metabolic rate, slows the degradation process of cellular components by intracellular organs, and decreases the lesions of membranes34 (for review see Kato et al35). Most enzyme systems show a 1.5- to 2.0-fold decrease in activity for every 10°C decline in tissue temperature.36 The measurement of the tissue temperature in 5 cases of the group TVEHYPOTH showed a drop of the temperature to a median of 16°C (range = 13°C to 21°C), much lower than the spontaneous drop of the liver temperature to a median of 31.5°C (range = 30.9°C to 33.5°C) observed during standard TVE.4

In 1974, Fortner et al7 reported the first series of liver resection under TVE combined to in situ hypothermic perfusion of the liver. Liver hypothermy was induced by portal and arterial perfusion of Ringer lactate chilled to 4°C. By analogy with the reduced-size liver transplantation, Pichlmayr et al37 designed the technique of ex situ liver resection. In the latter, the main technical steps are the installation of TVE, veno-venous bypass, and the removal of the whole liver. The latter is then perfused ex situ by portal and arterial perfusion of the HTK solution used for liver graft preservation. The liver is maintained in cold HTK solution packed with ice for optimal preservation during bench hepatectomy. The remaining liver is reimplanted as for a reduced-size graft. To improve the access to the posterior side of the liver without resorting to the division of the portal triad, Hannoun et al32,38,39 designed the so-called ante situm technique in which one of the hepatic veins is divided, allowing mobilization of the liver anteriorly. During the procedure, the liver is placed on a heat exchanger (4°C). The future remnant liver is perfused with the Belzer's36 University of Wisconsin solution chilled at 4°C (UW solution) via the portal vein or the hepatic artery. The remaining hepatic veins are reimplanted into the vena cava that was left in place. Finally, Belghiti et al40 described a variation of the latter technique in which the vena cava is cut above and below the liver and reconstructed after liver resection. Our experience was similar to that of Fortner et al,7 and the ex situ or ante situm techniques were not necessary. Compared with the in situ and ante situm techniques, the ex situ technique includes the division and the reconstruction of the portal triad following bench hepatectomy. The specific additional morbidity and mortality of this triple reconstruction (ie, the portal vein, the hepatic artery, and the bile ducts) might participate in the different short-term results when comparing the ex situ technique to the 2 others. From 1992 to 2002, 36 cases of ex situ hepatectomy have been reported;33,41–47 postoperative mortality occurred in 10 cases (28%),34,35 including 6 cases following salvage liver transplantation.33 By opposition and including the present 20 cases, 72 cases of in situ or ante situm hepatectomy are available for analysis.7,37,38,40,46,48 In-hospital mortality occurred in 6 cases (8%).7,38,40,48 Taking into account these contrasted results and the present shortage of liver grafts, we would consider the ex situ technique with caution.

Hemodynamic failure, including 1 fatal case, has been reported upon reperfusion of the liver following hepatectomy with hypothermic perfusion of the liver when veno-venous bypass was not applied.40 Besides the need to protect the liver parenchyma, prolonged TVE requires protection of the renal function threatened by the caval clamping to obviate splanchnic congestion subsequent to portal triad clamping and to maintain stable systemic hemodynamics since the caval clamping diminishes the right heart preload. The cavo-porto-jugular veno-venous bypass achieves this triple objective. Considering the lower peak of postoperative creatinine observed in the group TVEHYPOTH, this might be due rather to the systematic use of veno-venous bypass with its beneficial role on renal function as already shown in liver transplantation8 than to the hypothermic perfusion of the liver. TVE without caval clamping49 associated with in situ hypothermic perfusion of the liver might be a way to obviate the need for veno-venous bypass and its specific risks.10 However, not only it is not always feasible for actual indications of standard TVE, but also this would not solve the problem of prolonged splanchnic congestion, considered to participate to ischemia-reperfusion injury50,51 (for review, see Serracino-Inglott et al52), unless some form of temporary portacaval decompression is combined. In addition, the so-called inequity of splanchnic congestion on the intestine integrity itself and on other vital organs has been recently reappraised.50

Hypothermic perfusion of the liver allows prolongation of the duration of TVE and subsequent safe performance of hepatectomies that were otherwise technically possible but contraindicated due to a redhibitory risk of liver failure following the potentially too long warm ischemia time. The complex hepatectomies for large, centrally located tumors, and/or requiring vascular reconstruction are such procedures.45,46 In the present series, 11 of 15 (73%) vascular reconstructions required a prolonged TVE. These included the resection of all 3 main hepatic veins (7 cases), vena cava replacement (3 cases), and even the combination of both (1 case). We also consider45,46 that the complexity of these vascular reconstructions justifies the use of hypothermic perfusion of the liver. The discrepancy between the planned and the actual need for vascular reconstruction in our series (24 planned versus 15 actually performed; Tables 1 and 2) is due not only to preoperative imaging inaccuracy but also to the systematic use of intraoperative ultrasonography of the liver and the delay given by hypothermic perfusion of the liver to decide when vascular reconstruction is actually indicated.

The retrospective nature of the present study may be a source of biased interpretation of the results obtained. However, as the liver resections performed in the group TVEHYPOTH were more complex than those of the standard TVE groups, it is highly probable that for groups comparable for the procedure, the positive impact of hypothermic perfusion on liver tolerance and function, morbidity, and mortality would be maintained, if not reinforced. The fact that in situ hypothermic perfusion of the liver is well tolerated might enlarge its indications in the future. It could be used not only for patients with predictive factors for TVE ≥60 minutes but also to increase the safety of liver resections, even if already feasible within 1 hour of TVE. This could be considered particularly for patients with chronic liver disease, as already suggested by some case reports.41,44,48 Before this second step is achieved, the present results need to be confirmed by other teams, and ideally in prospective randomized studies including comparative cost analysis. Meanwhile, we will keep planning a priori hypothermic perfusion of the liver for patients with a planned vascular reconstruction, and for those with the others factors predictive for TVE ≥60 minutes (ie, with preoperative portal vein embolization and/or large tumors). The place of hypothermic perfusion of the liver among other protective measures against the ischemia-reperfusion injury is an important issue53,54 (for review see Jaeschke55).

CONCLUSION

In situ hypothermic perfusion of the liver is associated with an improved tolerance to ischemia, a better postoperative liver function and a lower morbidity compared with TVE ≥60 minutes. The available predictive factors for TVE ≥60 minutes might help to consider hypothermic perfusion of the liver before complex resection requiring prolonged TVE. The results of the present series and the predictive factors for TVE ≥60 minutes need to be confirmed by further studies.

Footnotes

Reprints: Daniel Azoulay, MD, PhD, Centre Hépato-Biliaire, Hôpital Paul Brousse 94800, Villejuif, France. E-mail: daniel.azoulay@pbr.ap-hop-paris.fr.

REFERENCES

- 1.Azoulay D, Raccuia JS, Castaing D, et al. Right portal vein embolization in preparation for major hepatic resection. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;181:267–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azoulay D, Castaing D, Smail A, et al. Resection of nonresectable liver metastases from colorectal cancer after percutaneous portal vein embolization. Ann Surg. 2000;231:480–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Castaing D, Emond JC, Kunstlinger F, et al. Utility of operative ultrasound in the surgical management of liver tumors. Ann Surg. 1986;204:600–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huguet C, Nordlinger B, Galopin J, et al. Normothermic hepatic vascular exclusion for extensive hepatectomy. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1978;147:689–693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bismuth H, Castaing D, Garden OJ. Major hepatic resection under total vascular exclusion. Ann Surg. 1989;210:13–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delva E, Barberousse JP, Nordlinger B, et al. Hemodynamic and biochemical monitoring during major liver resection with use of hepatic vascular exclusion. Surgery. 1984;95:309–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fortner JG, Shiu MH, Kinne DW, et al. Major hepatic resection using vascular isolation and hypothermic perfusion. Ann Surg. 1974;180:644–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shaw BW, Martin DJ, Marquez JM, et al. Venous bypass in clinical liver transplantation. Ann Surg. 1984;200:524–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oken AC, Frank SM, Merritt WT, et al. A new percutaneous technique for establishing venous bypass access in orthotopic liver transplantation. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 1994;8:58–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Budd JM, Isaac JL, Bennett J, et al. Morbidity and mortality associated with large-bore percutaneous venovenous bypass cannulation for 312 orthotopic liver transplantations. Liver Transplant. 2001;7:359–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kakazu T, Makuuchi M, Kawazaki S, et al. Reconstruction of the middle hepatic vein tributary during right anterior segmentectomy. Surgery. 1995;117:238–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Couinaud C. Le Foie: Etudes Anatomiques et Chirurgicales. Paris: Masson; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagorney DM, van Heerden JA, Ilstrup DM, et al. Primary hepatic malignancies: surgical management and determinants of survival. Surgery. 1989;106:740–749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Makuuchi M, Takayama T, Gunven P, et al. Restrictive versus liberal blood transfusion policy for hepatectomies in cirrhotic patients. World J Surg. 1989;13:644–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jamieson GG, Corbel L, Campion JP, et al. Major liver resection without blood transfusion: is it a realistic objective? Surgery. 1992;112:32–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stephenson KR, Steinberg SM, Hughes L, et al. Perioperative blood transfusions are associated with decreased time to recurrence and decreased survival after resection of colorectal liver metastasis. Ann Surg. 1988;208:679–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamamoto J, Kosuge T, Takayama T, et al. Perioperative blood transfusion promotes recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatectomy. Surgery. 1994;115:303–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grazi GL, Mazziotti A, Jovine E, et al. Total vascular exclusion of the liver during hepatic surgery: selective use, extensive use, or abuse? Arch Surg. 1997;132:1104–1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Torzilli G, Makuuchi M, Midorikawa Y, et al. Liver resection without total vascular exclusion: hazardous or beneficial? an analysis of our experience. Ann Surg. 2001;233:167–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heaney JP, Stanton WK, Halbert DS, et al. An improved technique for vascular isolation of the liver: experimental study and case reports. Ann Surg. 1966;163:237–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huguet C, Gavelli A, Chieco PA, et al. Liver ischemia for hepatic resection: where is the limit? Surgery. 1992;111:251–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hannoun L, Borie D, Delva E, et al. Liver resection with normothermic ischaemia exceeding 1 h. Br J Surg. 1993;80:1161–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Emre S, Schwartz ME, Katz E, et al. Liver resection under total vascular isolation: variations on a theme. Ann Surg. 1993;217:15–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Terblanche J, Krige JEJ, Bornman PC, et al. Simplified hepatic resection with the use of prolonged vascular inflow occlusion. Arch Surg. 1991;126:298–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Habib N, Zografos G, Dalla Serra G, et al. Liver resection with total vascular exclusion for malignant tumours. Br J Surg. 1994;81:1181–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Emond JC, Kelley S, Heffron T, et al. Surgical and anesthetic management of patients undergoing total vascular isolation. Liver Transplant Surg. 1996;2:91–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Evans P, Vogt DP, Mayes III JT, et al. Liver resection under total vascular exclusion. Surgery. 1998;124:807–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berney T, Mentha G, Morel PH. Total vascular exclusion of the liver for the resection of lesions in contact with the vena cava or the hepatic veins. Br J Surg. 1998;85:485–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.So SK, Monge H, Esquivel CO. Major hepatic resection without blood transfusion: experience with total vascular exclusion. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;14(suppl):S28–S31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Didolkar MS, Fitzpatrick JL, Elias EG, et al. Risk factors before hepatectomy, hepatic function after hepatectomy and computed tomographic changes as indicators of mortality from hepatic failure. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1989;169:17–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elias D, Lasser P, Rougier P, et al. Frequency, technical aspects, results, and indications of major hepatectomy after prolonged intra-arterial hepatic chemotherapy for initially unresectable hepatic tumors. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;180:213–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hannoun L, Panis Y, Balladur P, et al. Ex-situ in-vivo liver surgery. Lancet. 1991;337:1616–1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oldhafer KJ, Lang H, Schlitt HJ, et al. Long-term experience after ex situ liver surgery. Surgery. 2000;127:520–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takeuchi K, Ohira M, Yamashita T, et al. An experimental study of hepatic resection using an in situ hypothermic perfusion technique. Hepatogastroenterology. 1997;44:1281–1294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kato A, Singh S, McLeish KR, et al. Mechanisms of hypothermic protection against ischemic injury in mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;282:G608–G616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Belzer FO, Southard JH. Principles of solid-organ preservation by cold storage. Transplantation. 1988;45:673–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pichlmayr R, Grosse H, Hauss J, et al. Technique and preliminary results of extracorporeal liver surgery (bench procedure) and of surgery of the in situ perfused liver. Br J Surg. 1990;77:21–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Delrivière L, Hannoun L. In situ and ex situ procedures for complex major liver resections requiring prolonged hepatic vascular exclusion in normal and diseased livers. J Am Coll Surg 1995;181:272–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hannoun L, Delrivière L, Gibbs P, et al. Major extended hepatic resections in diseased livers using hypothermic protection: preliminary results from the first 12 patients treated with this new technique. J Am Coll Surg. 1996;183:597–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Belghiti J, Dousset B, Sauvanet A, et al. Résultats préliminaires de l'exérèse < ex situ> des tumeurs hépatiques: une place entre les traitements palliatifs et la transplantation. Gastroentérol Clin Biol. 1991;15:449–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kumada K, Yamaoka Y, Morimoto T, et al. Partial autotransplantation of the liver in hepatocellular carcinoma complicating cirrhosis. Br J Surg. 1992;79:566–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yanaga K, Kishikawa K, Shimada M, et al. Extracorporeal hepatic resection for previously unresectable neoplasms. Surgery. 1993;113:637–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yagyu T, Shimizu R, Nishida M, et al. Reconstruction of the hepatic vein to the prosthetic inferior vena cava in right extended hemihepatectomy with ex situ procedure. Surgery. 1994;115:740–744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wakabayashi H, Maeba T, Okano K, et al. Treatment of recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma by hepatectomy with right and middle hepatic vein reconstruction using total vascular exclusion with extracorporeal bypass and hypothermic hepatic perfusion: report of a case. Surg Today Jpn J Surg. 1998;28:547–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lodge JPA, Ammori BJ, Prasad R, et al. Ex vivo and in situ resection of inferior vena cava with hepatectomy for colorectal metastases. Ann Surg. 2000;231:471–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hemming AW, Reed AI, Langham MR, et al. Hepatic vein reconstruction for resection of hepatic tumors. Ann Surg. 2002;235:850–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lechaux D, Magavand JM, Raoul JL, et al. Ex vivo right trisegmentectomy with reconstruction of inferior vena cava and “flop” reimplantation. J Am Coll Surg. 2002;194:842–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ohwada S, Ogawa T, Kawashima Y, et al. Concomitant major hepatectomy and inferior vena cava reconstruction. J Am Coll Surg. 1999;188:63–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nagasue N, Yukaya H, Ogawa Y, et al. Segmental and subsegmental resections of the cirrhotic liver under inflow and outflow occlusion. Br J Surg. 1985;72:565–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu DL, Jeppsson B, Hakansson CH, et al. Multiple-system organ damage resulting from prolonged hepatic inflow interruption. Arch Surg. 1996;131:442–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Arai M, Thurman RG, Lemasters JJ. Ischemic preconditioning of rat livers against cold storage-reperfusion injury: role of nonparenchymal cells and the phenomenon of heterologous preconditioning. Liver Transplantation. 2001;7:292–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Serracino-Inglott F, Habib NA, Mathie RT. Hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am J Surg. 2001;181:161–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Clavien PA, Yadav S, Sindram D, et al. Protective effects of ischemic preconditioning for liver resection performed under inflow occlusion in humans. Ann Surg. 2000;232:155–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Compagnon P, Wang HB, Southard JH, et al. Ischemic preconditioning in a rodent hepatocyte model of liver hypothermic preservation injury. Cryobiology. 2002;44:269–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jaeschke H. Molecular mechanisms of hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury and preconditioning. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2003;284:G15–G26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]