Abstract

The viral protein Rev is essential for the export of the subset of unspliced and partially spliced lentiviral mRNAs and the production of structural proteins. Rev and its RNA binding site RRE can be replaced in both human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) by the constitutive RNA transport element CTE of the simian type D retroviruses. We used neonatal macaques as a sensitive animal model to evaluate the pathogenicity of a pair of SIV mutant strains generated from Rev-independent molecular clones of SIVmac239 which differ only in the presence of the nef open reading frame. After high primary viremia, all animals remained persistently infected at levels below the threshold of detection. All macaques infected as neonates developed normally, and none showed any signs of immune dysfunction or disease during follow-up ranging from 2.3 to 4 years. Therefore, the Rev-RRE regulatory mechanism plays a key role in the maintenance of high levels of virus propagation, which is independent of the presence of nef. These data demonstrate that Rev regulation plays an important role in the pathogenicity of SIV. Replacement of Rev-RRE by the CTE provides a novel approach to dramatically lower the virulence of a pathogenic lentivirus. These data further suggest that antiretroviral strategies leading to even a partial block of Rev function may modulate disease progression in HIV-infected individuals.

Attenuated strains of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) provide key model systems to understand virus replication and pathogenesis. Attenuated strains, such as SIVmac1A11 (22), have been molecularly cloned from SIV-infected animals or obtained by deletion of nonessential viral genes such as vif, vpx, vpr, and nef (6, 11, 13, 20), introduction of amino acid changes in env (8), deletion of the RNA leader sequence (14), and modulation of transcription and/or posttranscriptional regulation (13, 28, 36, 37) in the pathogenic SIVmac239 (26).

We have studied the role of Rev regulation in the pathogenesis of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and SIV. Lentiviruses depend on the viral Rev protein for virus production (4, 7). Rev is essential for the export of the Rev-responsive element (RRE)-containing mRNAs from the nucleus and the production of the structural proteins. We postulated that a drastic change in the posttranscriptional regulation of SIV may alter the pathogenic potential of the virus.

Because Rev is an essential factor, this hypothesis could not be addressed by deletion mutagenesis; it required substitution of Rev function by alternative mechanisms. The constitutive RNA transport elements (CTEs) of the simian type D retroviruses (3, 32, 39), the CTE-related element (31), and the recently identified RNA transport element RTE (25), present in distinct subgroups of intracisternal A-particle retroelements (IAP), represent three RNA transport elements that utilize cellular export factors and were shown to fulfill this criterion. These findings opened the possibility of generating virus strains having the Rev/RRE regulation replaced by another posttranscriptional regulatory system and evaluating the pathogenicity of these altered viruses in the presence of all other viral proteins in animal model systems (34, 36).

The mechanism mediating the export of CTE-containing mRNAs has been studied in detail. NXF1 (formerly called TAP) (12) is the key protein binding to the CTE RNA element and promoting its export. NXF1 is a ubiquitous cellular protein, which also plays an important role in the nucleocytoplasmic export of cellular mRNAs and whose function as an mRNA transport factor is conserved among metazoa (16, 17, 19, 27, 33).

A common feature of the Rev-independent clones of HIV and SIV is that they replicated to lower levels in primary cells in vitro (34, 36, 39). Using the SCID-hu mouse model, we found that, in contrast to studies using other HIV mutants, the CTE-containing HIV did not deplete CD4-bearing thymocytes, indicating that the replacement of the Rev-RRE regulatory system by the CTE generated viruses with altered biological properties in vivo (34). This finding was further supported in a pilot study using three juvenile rhesus macaques, which showed that the Rev-independent Nef− SIV strains induced low primary viremia and caused chronic infection without any signs of immune dysfunction or disease during the reported 80 weeks of follow-up (37). These data demonstrated that the replacement of the Rev regulation by the CTE RNA transport element generated a virus variant that retained its replicative capacity both in vitro and in vivo and suggested altered pathogenicity of the Rev-independent SIV.

Infection by another attenuated SIV strain, SIVmac239Δ3, lacking vpr and nef showed no pathogenicity during the initial follow-up in juvenile macaques, but even after a few months, it was highly pathogenic in neonatal macaques (2, 6, 38). Therefore, the neonatal macaque represents a sensitive model to evaluate the pathogenicity of potentially attenuated SIV strains.

In the present work, we examined the pathogenicity of the Rev-independent SIVmac239 containing the CTE RNA export element upon infection of neonatal macaques. Two groups of animals were infected with either a Nef-negative or a Nef-positive variant of the Rev-independent SIV. We present a follow-up study spanning up to 4 years postinoculation, demonstrating that all animals were chronically infected but remained clinically healthy and controlled the viremia at very low or undetectable levels.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Molecular clones of SIV.

The Rev-independent Nef(−) SIV clone contains CTE inserted at nucleotide (nt) 9281 of SIVmac239 (26) as described (36). The Nef-del clone contains a further deletion of 146 bp spanning the remaining nef sequences and was generated by deleting the nef sequences 3′ to the CTE (nt 9287 to 9433 of SIVmac239). A PCR fragment containing BamHI and NotI, the polypurine tract, and the 3′ long terminal repeat (LTR) followed directly by SacI and EcoRI was used to replace the BamHI (located 3′ to the CTE)-EcoRI (located in the 3′-flanking region) fragment in a subclone containing the 3′ half of R− RRE− Nef− CTE. This construct lacks the monkey genomic sequences next to the 3′ LTR. The intact molecular clone was generated by replacing the SphI-EcoRI fragment of the Rev-independent Nef(−) clone.

For the Rev-independent Nef-positive SIV, the 5′ portio nef (nt 9081 to 9280) was generated synthetically from oligonucleotides which had the nucleotide changed but maintained the coding potential to avoid sequence duplication. This region was PCR amplified and inserted into the unique NcoI site in nef located 3′ to the CTE. For this, we used an intermediate vector containing the SacI fragment spanning a portion of the 3′ half of R− Rev− Nef-negative CTE in which the all NcoI sites located 5′ to the CTE were eliminated by site-directed mutagenesis. This SacI fragment was used to replace the SacI fragment of the Rev-independent Nef(−) mutant. The intact Rev-independent Nef-positive molecular clone was generated by replacing the SphI-EcoRI fragment.

Virus expression.

Human 293 cells were transfected, and cell extracts were analyzed for the expression of Nef by Western immunoblots using a rabbit anti-Nef antiserum obtained from P. Luciw. Culture supernatants were used to infect rhesus macaque peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) or CEMx174 cells. Supernatants were monitored for the production of p27gag antigen using a commercially available assay (Zeptometrix).

Infection of neonatal and adult rhesus macaques.

Virus stocks were generated in rhesus macaque PBMC collected from healthy, pathogen-free animals (37). The stocks were titrated in CEMx174 cells and used to infect neonatal and adult macaques with 1 ml of virus via the intravenous route. The neonatal macaques were infected at 1 day after birth, whereas the mothers were infected after the infants had been weaned. The following macaques were exposed to the indicated viruses and inocula (in 50% tissue culture infectious doses [TCID50]; the mothers are indicated in brackets): Nef(−) strains RKh-6 [RSb-3] (103), RPh-6 [N901], RJi-6 [ROl-3] (5 × 103); Nef-del, RQh-6 [RUu-3] (1.6 × 104); and Nef-positive strains 31469, 31470, 31474, and 31477 (104). The animals were monitored at regular intervals at days 0, 7, 14, and 28, then monthly up to 1 year, and every 3 months (Nef-negative) or monthly (Nef-positive) thereafter. Hematological values were monitored using standard flow cytometry. All animals used were healthy and pathogen-free.

Indicator cell line.

A recombinant retrovirus vector containing the HIV-1 LTR to +80 linked to the gene encoding the improved green fluorescent protein (GFP) FRED25 (29) was used to transduce CEMx174 cells. Using limited dilution of the G418-resistant mass culture, a subclone was selected for low basal levels of GFP and for being able to produce high GFP levels upon infection by SIVmac239 and used in the cocultivation experiments.

Virological parameters.

Plasma viral RNA was measured using the real-time quantitative reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR assay (30). Virus isolations were performed by cocultivation with CEMx174 and analysis of p27gag production or with the CEMx174-GFP indicator cell line and by monitoring for the appearance of green cells. Proviral DNA was quantitated in monkey PBMC using gag-specific primers (21).

For sequence analysis, DNA was isolated directly from the PBMC, and the regions containing the first and second coding exons of the mutated rev were sequenced. Plasma samples were subjected to Western immunoblot analysis using the commercial kit for HIV-2 (version 1.2) from Genelabs Diagnostics manufactured by Zeptometric. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) titers were determined using whole SIVmac251 lysate spiked with SIV gp120 protein. SIV antigen-specific proliferation was measured as [3H]thymidine uptake in PBMC from fresh blood samples and was performed in triplicate (15). Stimulation index, calculated as the mean counts per minute of replicate antigen wells divided by the mean counts per minute of medium alone, was scored positive if >2.0.

Neutralizing antibody assays.

Antibody-mediated neutralization of a T-cell-line adapted (TCLA) stock of SIVmac251 and molecularly cloned SIVmac239/nef-open was assessed in CEMx174 cells by using a reduction in virus-induced cell killing as described (23). Briefly, 500 TCID50 of virus were incubated with multiple dilutions of serum samples in triplicate for 1 h at 37°C in 96-well flat-bottomed culture plates. Cells were added, and the incubation continued until most but not all cells in virus control wells (cells plus virus but no serum sample) were involved in syncytium formation (usually 4 to 6 days). Cell viability was then quantified by neutral red uptake.

Neutralization titers are defined as the reciprocal serum dilution (before the addition of cells) at which 50% of cells were protected from virus-induced killing. A 50% reduction in cell killing corresponds to an approximately 90% reduction in p27gag antigen synthesis in this assay. The assay stocks of SIVmac251 and SIVmac239 were prepared in H9 cells and human peripheral blood mononuclear cells, respectively.

RESULTS

Absence of nef open reading frame does not affect the replicative capacity of Rev-independent SIV.

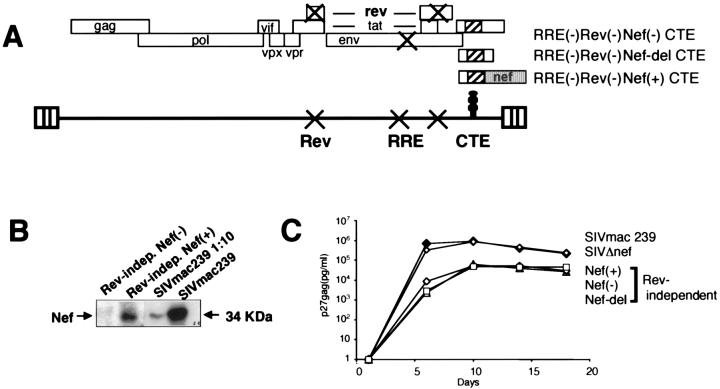

We generated a pair of molecular clones of the Rev-independent SIVmac239 which had rev and RRE replaced by the RNA transport element CTE and which either lacked or contained nef (Fig. 1A). Two variants of the Nef-negative molecular clones were used. The previously published Rev-independent Nef(−) SIV clone contains the CTE inserted into nef (36), whereas Nef-del has an additional deletion in the nef gene located downstream of CTE, which further reduces the ability to produce a Nef peptide.

FIG. 1.

Expression of Rev-independent molecular clones of SIVmac239. (A) Rev-independent molecular clones are derived from SIVmac239, lack the Rev AUG, and contain 15 point mutations in the second coding exon of rev and 15 point mutations in RRE. These point mutation were designed to destroy both rev and RRE without affecting the overlapping tat and env open reading frames. All clones contain the CTE of SRV-1 inserted 3′ to the env terminator codon located in the nef gene. The RRE− Rev− Nef− CTE was described previously (36); the RRE− Rev− Nef-del CTE has an additional 146-bp deletion, removing the region between the CTE and the polypurine tract; the RRE− Rev− Nef+ CTE has the intact nef gene inserted 3′of CTE. (B) Nef expression from the Nef-positive Rev-independent SIV. The Nef-negative and Nef-positive Rev-independent molecular clones and wild-type SIVmac239 were transfected into human 293 cells. Cell extracts were analyzed by Western immunoblot probed with anti-Nef antiserum. For SIVmac239-transfected cells, the total and a 1:10 dilution of the extract were analyzed. (C) Replication of Rev-independent SIV viruses in rhesus macaque PBMC. Virus stocks generated upon cocultivation of transfected 293 cells with CEMx174 cells containing 30 to 90 ng of p27gag/ml were used for cell-free virus infection of 15 × 106 PBMC. The cultures were monitored over time, and virus propagation was assayed by measuring p27gag by antigen capture assay.

All Nef-negative clones can produce a 70-amino-acid N-terminal portion of Nef (36, 37), since they contain the Nef AUG located within env, which is similar to the SIVmac239Δnef (20). The Rev-independent Nef-positive molecular clone contains the intact nef gene inserted 3′ of the CTE. To avoid sequence duplication, the introduced 5′portion of nef has multiple changes in nucleotide sequence without altering the coding potential. Western blot analysis confirmed the production of Nef only from the Rev-independent Nef-positive SIV and from wild-type SIVmac239 clone (Fig. 1B). The levels of Nef produced by the Rev-independent Nef-positive SIV were about three to five times lower than that of wild-type SIVmac239. Considering that this clone also produced about fivefold lower levels of Gag, as determined by antigen capture assay, the proportion of Nef and Gag proteins produced by these two molecular clones was similar.

Virus stocks were generated upon transfection of human 293 cells with the molecular clones and cocultivation with rhesus macaque PBMC or CEMx174 cells. In vitro infection studies using PBMC (Fig. 1C) or CEMx174 (data not shown) showed that the two Nef-negative viruses [Nef(−) and Nef-del] as well as the Nef-positive SIV propagated to similar levels. In PBMC, all Rev-independent SIVmac239 variants replicated less than wild-type SIVmac239, as expected (36), and also less than SIVmac239Δnef (Fig. 1C). We showed previously that insertion of the CTE within wild-type SIVmac239 did not affect its replication (36). In addition, as expected (36), all Rev-independent SIV strains replicated to the same level as wild-type SIVmac239 in CEMx174 (data not shown). Since CTE mediated lower SIV expression from the Rev− RRE− clones in some cell types, we had speculated that this may be the result of unbalanced expression of the structural proteins (36)

Infection of neonatal macaques.

Two groups of four neonatal macaques were inoculated with 1 ml of the Rev-independent SIV stocks via the intravenous route at the age of 1 day using 1 × 103 to 1.6 × 104 TCID50 of virus stocks generated in PBMC. Three of the four animals (RKh-6, RPh-6, and RJi-6) received the Nef(−) variant, and RQh-6 received the Nef-del variant, while animals 31469, 31470, 31474, and 31477 received the Nef-positive variant. The Nef(−) and Nef-del virus variants are referred to as Nef-negative viruses throughout this work. RKh-6, RPh-6, RQh-6, and RJi-6 were reared by their respective mothers, N901, RSb-3, RUu-3, and ROl-3, whereas 31469, 31470, 31474, and 31477 were hand-reared. The two groups of animals were monitored over time between 4 years for the Nef-negative (194 weeks for RJi-6, 207 weeks for RPh-6 and RQh-6, and 208 weeks for RKh-6) and 2.3 years for the Nef-positive Rev-independent variants by monitoring different parameters such as viremia (plasma viral RNA, virus isolation), hematological values, cellular and humoral immune responses, development, and general health.

Control of viremia in infected neonatal macaques.

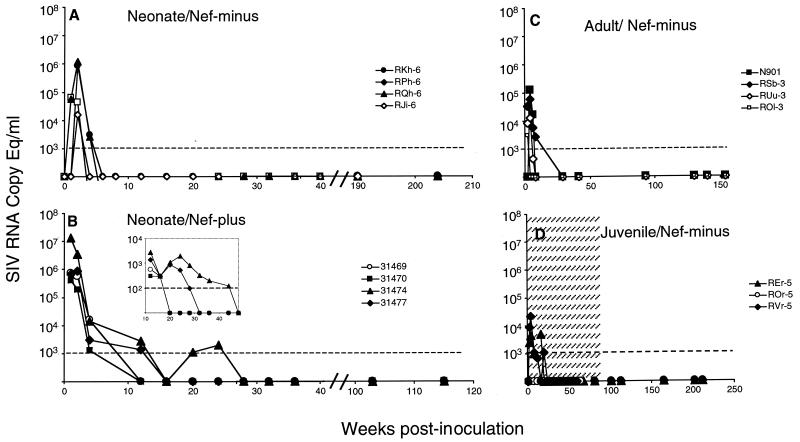

During the acute phase of infection, the viral RNA levels peaked between 1 and 2 weeks postinoculation ranging from 104 to 107 RNA equivalents per ml of plasma with a mean of about 106 RNA equivalents (Fig. 2A and 2B). These levels were about 2 logs lower than those obtained after infection of neonate macaques with SIVmac251 (35) and were significantly higher (about 2 logs) than those obtained in adult (Fig. 2C) and juvenile (see also Fig. 2D) (37) macaques infected with the same Rev-independent Nef-negative SIV strain. No significant differences were observed between the two groups of animals infected with the Nef-negative and the Nef-positive Rev-independent SIV.

FIG. 2.

Plasma viremia. Animals were infected with the Rev-independent Nef-negative SIV as neonates (A), adults (C), and juveniles (D) and with the Rev-independent Nef-positive SIV as neonates (B). Plasma SIV RNA levels were assayed by real-time RT-PCR (30). The Nef-positive SIV-infected neonates were also monitored with a more sensitive assay with a threshold of 100 RNA copies/ml (inset B). The animals infected as neonates were followed up for 119 (Nef-positive) and 208 (Nef-negative) weeks. The data in the shaded area in panel D are from reference 37.

We observed a range of peak values (16,200 to 1,220,000 RNA equivalents for Nef-negative versus 410,000 to 13,000,000 RNA equivalents for Nef-positive virus). Since, during early stages after birth, we could only analyze neonates at weeks 1, 2, and 4 postinfection, it is possible that these values do not reflect the peak per se and rather serve as indicators for virus propagation. We also did not notice a difference in the animals receiving different inocula. The plasma viral RNA levels declined sharply below detection within 6 to 16 weeks postinoculation. We noted a slight difference in the decline slope between animals infected as neonates with Nef-negative and Nef-positive viruses (Fig. 2A versus 2B). However, this difference is not linked to the presence of nef because another group of animals infected as neonates in a parallel study using a variant Rev-independent Nef-negative SIV containing a related CTE element showed a plasma viral RNA decline similar to that of the Nef-positive-infected neonates (A. S. von Gegerfelt and B. K. Felber, unpublished). The RNA levels were monitored for up to 4 years for the Nef-negative group and for 2.3 years for the Nef-positive group (Fig. 2A and 2B). Importantly, the plasma viral RNA levels for all the animals remained at or below the detection level of the assay during the complete time of follow-up.

During the primary viremia, animals 31469, 31470, 31474, and 31477 were also monitored with a more sensitive quantitative RT-PCR assay detecting 100 RNA equivalents per ml (Fig. 2B, inset). The RNA levels of 31469 and 31470 remained below detection level starting at week 16. The RNA levels of 31474 and 31479 declined more slowly and were measurable until weeks 32 and 24, respectively. Thereafter, both animals were below threshold except for a few rare values reaching a maximum of 170 molecules (weeks 44 and 103 for 31474 and week 91 for 31477). During the chronic phase of infection, RKh-6, RPh-6, RQh-6, and RJi-6 were monitored with the more sensitive assay, and viremia remained below the detection level of the assay.

In summary, the two groups of macaques infected as neonates with the Nef-negative or Nef-positive Rev-independent SIV strains had a similar phase of acute viremia, and all animals were able to control the infection, resulting in low chronic viremia. Neither the genotype nor the amount of virus inoculum affected the outcome of the infection.

Control of viremia in infected adult and juvenile macaques.

After weaning off their infants, the mothers (N901, RSb-3, RUu-3, and ROl-3), which again tested negative for SIV infection at this time point, were also inoculated with the same Nef-negative Rev-independent SIV as their respective offspring and monitored for 154 weeks. This gave us the additional opportunity to study infection by the Rev-independent SIV of macaques of a different age group and allowed us to compare infection of neonates and adults (this study) with the data of our previously infected three juvenile macaques (37), which have been further monitored for 4.5 years. As shown in Fig. 2C, the adult animals had peak plasma RNA levels ranging from 3 × 103 to 1.3 × 105 RNA equivalents per ml, which declined to levels below threshold thereafter. Similarly, after the phase of the acute viremia, no plasma virus above the threshold was found for the previously infected juvenile macaques (Fig 1D).

Virus isolations were performed using a cocultivation assay in CEMx174 cells (for the Nef-negative group) and analyzed by antigen capture assay or by using engineered CEMx174-GFP cells (Nef-positive group) and monitored for the appearance of green cells, indicating infection. Table 1 shows that virus isolation was only possible within the first 4 weeks postinoculation. Semiquantitative assays performed for RKh-6, RPh-6, RQh-6, and RJi-6 revealed low levels (between 1 and 64 infected cells per million PBMC). Accordingly, measurements of proviral DNA in the PBMC of these animals revealed levels ranging from 100 to 6,000 target DNA copies per 106 PBMC within the first 2 months postinoculation, which declined within the following months to less than 5 target DNA copies per 106 PBMC (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Virus isolation from infected neonate macaquesa

| Wk | Virus isolatedb

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RKh-6 | RPh-6 | RQh-6 | RJi-6 | 31369 | 31470 | 31474 | 31477 | |

| 1 | + | + | + | nd | + | + | + | + |

| 2 | nd | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 4 | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| 6 | − | nd | − | − | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 8 | − | − | nd | − | − | − | − | − |

| 12 | − | − | − | − | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 16 | − | − | − | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 20 | − | − | − | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 36 | nd | nd | nd | nd | − | − | − | − |

Rhesus PBMC were used for cocultivation with CEMx174 or CEMx174-GFP cells.

nd, not done.

TABLE 2.

Proviral DNA in infected neonatal macaques

| Wk | No. of proviral DNA copies/106 PBMC

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RKh-6 | RPh-6 | RQh-6 | RJi-6 | |

| 1 | 379 | 379 | 5 | nda |

| 2 | nd | 1,515 | 1,515 | 95 |

| 4 | 6,060 | 379 | 4 | 95 |

| 6 | 95 | 29 | 95 | nd |

| 8 | 379 | 95 | 95 | nd |

| 12 | 5 | 2 | 4 | nd |

nd, not done.

To address the question of whether the 16 point mutations introduced into the two coding exons of rev in the Rev-independent SIV were maintained stably upon virus propagation in the animals, DNA was isolated directly from the PBMC of RQh-6 and RJi-6 at 2 weeks postinoculation. The two exons were PCR amplified as 193-bp and 373-bp fragments, respectively, cloned, and sequenced. Sequence analysis of 20 clones from each animal revealed that all clones lacked the rev AUG. Analysis of 13 clones of RQh-6 and 18 clones of RJi-6 spanning the second coding exon of rev confirmed the presence of all the introduced nucleotide changes. One clone showed one change (T8925C) leading to a reversion in rev (S64P). This clone as well as seven other clones had additional nucleotide changes resulting in either silent mutations or amino acid changes in the sequenced parts of tat, rev, and env.

The presence of the nef open reading frame was also verified by PCR analysis of the genomic DNA isolated at week 2 postinoculation. Ninety percent of the clones contained the correct size fragment, and sequence analysis confirmed the maintenance of the open reading frame. In conclusion, all of the clones had a rev-mutant genotype, demonstrating that this virus remains stable upon infection of neonatal macaques, despite the 1,000-fold-higher levels during the primary viremia. These data further support our previous observations that this virus is stable both in tissue culture and in juvenile macaques (36, 37).

Persistent humoral responses.

The animals were tested for development of humoral responses by Western blot analysis and ELISA (Table 3). Western blot analysis of sequential samples from animals infected with the Nef-negative and Nef-positive SIV viruses as neonates sampled between weeks 44 and 91 and weeks 24 and 32, respectively, showed persistent presence of antibody responses against Gag and Env (summarized in Table 3). Antibody titers were measured by ELISA. Table 3 shows persistent titers ranging from 1:50 to 1:3,200 between 0.5 and 4 years postinoculation. These values were at least 10-fold lower than those obtained from SIVmac251-infected juvenile macaques (A. S. von Gegerfelt and B. K. Felber, personal observation).

TABLE 3.

Humoral responses in macaques infected with Rev-independent SIV strains

| Infection group and virus strain | Animal | Western blot resulta

|

Antibody titerb to SIVmac251 at time postinfection (yr):

|

Neutralizing antibody titerc to lab-adapted SIVmac251 at time postinfection (yr):

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Env | Gag | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2–2.5 | 3 | ||

| Neonates | |||||||||||

| Nef-negative | RKh-6 | + | + | 800 | 800 | 3,200 | 3,200 | 195 | 160 | ||

| RPh-6 | + | w | 800 | 800 | 800 | 200 | <20 | <20 | |||

| RQh-6 | + | ++ | 800 | 3,200 | 3,200 | 3,200 | 327 | 701 | |||

| RJi-6 | + | + | 200 | 800 | 3,200 | 3,200 | <20 | <20 | |||

| Nef-positive | 31469 | + | + | 800 | 800 | 800 | 379 | 520 | |||

| 31470 | + | w | 200 | 200 | 50 | 286 | <30 | ||||

| 31474 | + | ++ | 3,200 | 3,200 | 3,200 | <30 | 325 | ||||

| 31477 | + | ++ | 3,200 | 200 | 800 | 131 | 140 | ||||

| Adults | |||||||||||

| Nef-negative | N901 | + | + | 1,404 | 1,482 | ||||||

| RUu-3 | + | − | <20 | <20 | |||||||

| RSb-3 | + | w | 125 | 52 | |||||||

| ROl-3 | + | − | <20 | <20 | |||||||

| Juveniled | |||||||||||

| Nef-negative | REr-5 | + | + | <20 | <20 | ||||||

| ROr-5 | + | + | 520 | 432 | |||||||

| RVr-5 | + | ++ | 4,589 | 3,825 | |||||||

w, weakly positive.

Titers were defined as the serum dilution at or above the absorbence value two times of the negative contol.

Titers are the reciprocal serum dilution at which 50% of the cells were protected from virus-induced killing, as measured by neutral red uptake.

Western immunoblot data are from reference 37.

We also detected the presence of low, persistent levels of neutralizing antibodies in a CEMx174 killing assay against the H9-grown lab-adapted SIVmac251 in all animals except RPh-6 and RJi-6. These values were at least 10-fold lower than those obtained in infant macaques infected with the attenuated but pathogenic SIVmac239Δ3 (23). None of the macaques infected as neonates with Rev-independent viruses developed neutralizing antibodies against the more difficult to neutralize SIVmac239 strain, as observed earlier for SIVmac239Δ3 (23).

Western immunoblot analysis of sequential samples from the infected adult animals taken at weeks 8, 28, and 40 postinoculation (Table 3) and of juvenile macaques (37) (summarized in Table 3) showed the persistent presence of anti-Env and anti-Gag antibodies. Animals of both groups also developed neutralizing antibody titers to SIVmac251 of up to 1:4,500 (Table 3). RVr-5 also developed low levels (1:50) of neutralizing antibody against SIVmac239. RUu3-3 and ROl-3 generated anti-Env but no anti-Gag antibodies or neutralizing antibody.

Taken together, the low antibody titers and the weak neutralizing capacity supported the notion that there is on-going low-level virus replication of the Rev-independent SIV strains in the monkeys infected as neonates, as juveniles, or as adults.

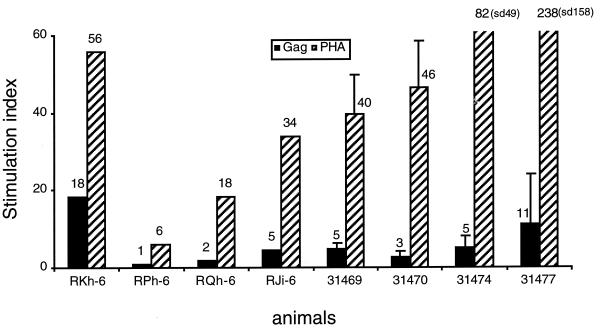

Cellular immune responses.

To examine cellular immunity, we measured SIV-specific proliferative responses to p27gag antigen using PBMC isolated at two (between 176 and 204 weeks) and three (weeks 90, 97, and 105) time points for the Nef-negative and Nef-positive groups, respectively. As shown in Fig. 3, all neonates except RPh-6 showed T-helper cell responses to the SIV Gag-specific stimulation. Although persistent over time, the overall stimulation indices were low, ranging from 2- to 18-fold, with an average of 6-fold. These data further support the notion that the macaques infected as neonates have on-going low-level virus replication.

FIG. 3.

Lymphocyte proliferative responses to SIV Gag antigen in neonates infected with Rev-independent viruses. The Nef-negative-infected neonates (RJi-6, RKh-6, RPh-6, and RQh-6) were analyzed at two time points between 176 and 201 weeks, and the mean values for Gag and the positive control PHA are presented. The Nef-positive SIV-infected animals (31469, 31470, 31474, and 31477) were assayed at three time points (weeks 90, 97, and 105). The proliferative responses are given as means with standard deviations (sd).

Examination of the animals infected as adults (weeks 140 and 154) and as juveniles (between 204 and 226 weeks) showed a positive stimulation index only for RVr5. All the others, including all animals infected as adults, were negative. REr5 and RSb-3 could not be evaluated because of repeated high basal activity and/or inability to respond to phytohemagglutinin (PHA). Taken together, these findings are in agreement with very low levels of sustained virus replication.

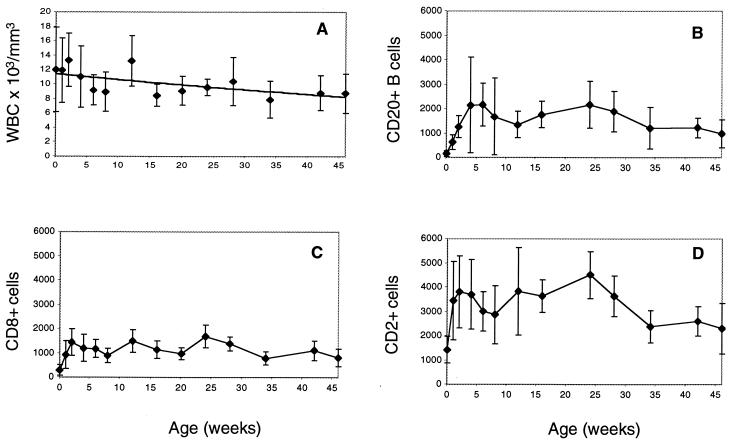

No signs of hematological abnormalities or immune dysfunction.

We further monitored hematological values at regular intervals over the 2.3 to 4 years of follow-up (Fig. 4 and 5). Overall, all animals showed normal lymphocyte counts comparable to those of age-matched naive animals (5). The initial high white blood cell counts declined during the first year of life (Fig. 4A) and stabilized thereafter, as expected (5). B-cell counts (CD20+) were very low after birth, increased during the first month, and stabilized at the expected levels (Fig. 4B). CD8+ cells (Fig. 4C) and CD2+ cells (Fig. 4D) were very low at birth, increased during the next 2 weeks, and remained at this level thereafter. Taken together, all these parameters matched those published for naive age-matched animals (5).

FIG. 4.

Hematological values. White blood cell counts (A) and numbers of CD20+ B cells (B), CD8+ cells (C), and CD2+ cells (D) in macaques infected as neonates (31469, 31470, 31474, and 31477) by the Nef-positive Rev-independent SIV variants were determined. Mean values with standard deviations for the first 45 weeks are shown.

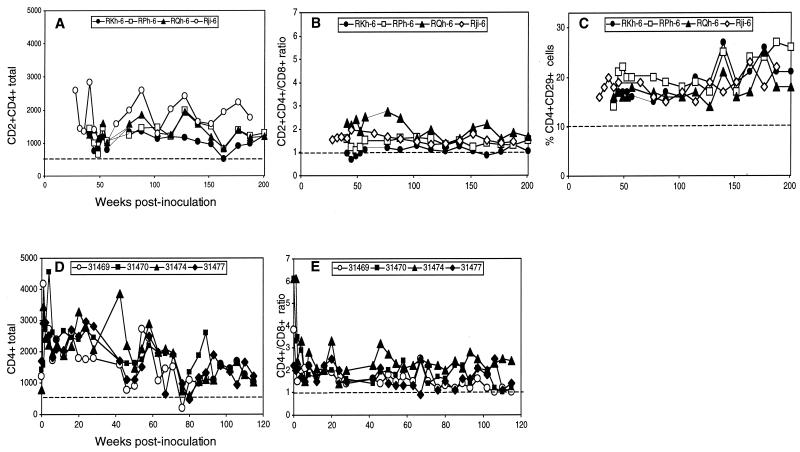

FIG. 5.

Analysis of CD4+ cell subset. The Nef-positive-infected animals were analyzed starting at birth, while the evaluation of the Rev-independent Nef-negative-infected neonates started at week 29 (RJi-6) and week 42 (RKh-6, RPh-6, and RQh-6). Total CD4+ cells (A and D), the CD4+/CD8+ cell ratio (B and E), and the percent CD4+ CD29+ double-positive T cells (C) are shown for macaques infected as neonates with Nef-negative (A to C) and Nef-positive (D to E) SIV. Note that in panels D and E (Nef-positive), CD4+ cells were measured, while in all other panels CD2+ CD4+ cells were measured.

We also compared the levels of the CD4+ cell subset in the Nef-negative SIV-infected animals (CD2+ CD4+) and in the Nef-positive SIV-infected animals (total CD4+ lymphocytes) (Fig. 5). Overall, the analysis of the Nef-negative (Fig. 5A to C) and the Nef-positive (Fig. 5D and 5E) SIV-infected animals showed usual fluctuations in individual animals, but no difference between the two groups was detected. Importantly, the CD4+ cells did not show any decline over time.

As noted for naive neonate macaques (5), the absolute counts of CD4+ cells (Fig. 5D) are much higher after birth than the counts of CD8+ cells (Fig. 4C). During the next few weeks of life, the levels of CD4+ cells decreased and stabilized in all animals, as expected (5). In agreement with this finding, the CD4+/CD8+ ratios were higher in neonates (Fig 5E), declined during infancy to a ratio of 1 to 2, and remained at this level thereafter (Fig. 5B and E). The Nef-negative-infected animals were only monitored starting from week 29 (RJi-6), week 40 (RPh-6 and RQh-6), and week 41 (RKh-6). Thereafter, no changes from age-matched naive animals were noticed.

For this group of animals, we also included the measurement of percent CD4+ CD29+ cells (Fig 5C). This subset measures memory cells; decline of these cells to <10% could indicate early signs of disease progression (24). As shown in Fig. 5C, no changes in this parameter were observed during the 208 weeks postinfection.

Similarly, we also monitored the hematological parameters of the infected adult macaques as well as the three juveniles from our pilot study (data not shown). No changes in total CD4+ cells, CD4+/CD8+ ratio, or the percent CD4+ CD29+ cells were observed.

In conclusion, the virological and hematological parameters together with the physical evaluation of the animals demonstrate that macaques infected with the Rev-independent SIV strains as either neonates, juveniles, or adults showed no signs of disease during the follow-up period ranging from 2.3 to 4.5 years.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that the Rev-independent SIV strains induced chronic infection in neonatal macaques. All eight animals infected as neonates were able to control this attenuated virus over a period ranging from 2.3 to 4 years. Although neonatal macaques infected by this SIV strain showed high peak levels of viremia of up to 107 RNA copies per ml, this peak was always followed by a rapid decline to levels below detection (<100 RNA copies per ml of plasma).

In addition to the neonatally infected macaques, we have been monitoring animals infected with the Rev-independent SIV strains as juveniles and adults for up to 4.5 years. In all cases, the phase of acute viremia was followed by a decline to levels below the detection level of the assay. These data demonstrate that the Rev-RRE regulatory mechanism is required for continuous high levels of virus propagation in the host. The observed persistence of humoral and cellular immune responses further supports the notion that all the animals have a chronic but controlled infection. None of the animals showed any signs of immune dysfunction or disease during the 2.3 to 4 years of follow-up. This finding is in contrast to that of infection studies using attenuated SIVmac239Δ3, which showed early signs of immune dysfunction and a median survival time of 166 weeks in neonatally infected macaques (2).

Comparison of viremia levels and pathogenic potential of Nef-negative and Nef-positive strains did not reveal any differences, indicating that the fundamental change in virus expression rather than the absence of the accessory nef gene is responsible for this outcome. Therefore, Rev, a key factor for the expression of the RRE-containing subset of viral mRNAs, also plays an important role in pathogenicity, in that Rev regulation may guarantee optimal expression of the structural proteins, thus promoting efficient production of infectious virus.

Ideally, we would like to study Rev-independent expression using an RNA transport element as potent as the viral Rev-RRE system. So far this has not been possible, since all elements identified which are able to replace Rev-RRE, such as the CTE, the CTE-related CTE IAP, and the RTE, function less efficiently. We speculate that the acquisition of Rev-RRE guarantees efficient virus expression, which, as a consequence, leads to pathogenesis. For this reason, the replacement of Rev-RRE by the CTE provides a novel approach to lower the virulence of a pathogenic lentivirus.

We observed chronic but controlled infection by the Rev-independent SIV in monkeys infected as neonates, juveniles, and adults. The presence of persistent humoral and cellular anti-SIV responses in the absence of detectable plasma viremia indicates on-going low level virus expression. The anti-SIV immune responses were comparable to those obtained with SIVmac239Δ3 but higher than those obtained with SIVmac239Δ4-infected juvenile macaques (9, 10, 18). During the time of follow-up of up to 4.5 years, no signs of immune dysfunction or disease have been observed. Two of the juvenile macaques (REr-5 and ROr-5) had to be sacrificed because of self-mutilation at week 205 and 221 postinoculation, respectively. These animals did not show any SIV replication or signs of immune dysfunction.

Infection of neonatal macaques by SIVmac239Δ3 led to relatively rapid onset of immune dysfunction and disease development (1, 2, 38). Since infection by our Rev-independent SIV clones was not pathogenic despite initial high viremia, it is important to understand the difference in the outcome. Importantly, SIVmac239Δ3 can be expressed as efficiently as wild-type virus (11) in vitro. In contrast, the CTE function is not as efficient as that of Rev-RRE, leading to reduced mRNA export by the Rev-independent clones. This may lead to continuous low-level production of virus with reduced infectivity, as previously reported from in vitro and in vivo studies (34, 36, 37). Further studies are necessary to shed light on the underlying mechanisms preventing pathogenicity by the Rev-independent clones. In addition, our data suggest that antiretroviral strategies leading to even a partial block of Rev function may lead to a delay in disease progression in HIV-infected individuals. Thus, our data may be considered as proof of concept in a realistic animal model supporting the development of anti-Rev drugs.

The replacement of Rev/RRE provides a novel approach to fundamentally alter the virulence of a pathogenic SIV and possibly HIV (34). These studies will provide critical information about the establishment and maintenance of host immune responses during chronic lentivirus infections in the absence of pathogenicity.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Piatak and J. Lifson for RNA-PCR assays; P. Markham, P. Luciw, and V. Kewalramani for assays, reagents, and equipment use; J. Bear and T. Jones for assistance; B. Mathieson and N. Miller for support; and A. Valentin and G. Franchini for discussions.

Research was sponsored in part by NIH grants RO1 A135533-S1 and RO1 RR14180 to R.M.R., the Center for AIDS Research core grant IP3028691-01 awarded to the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute as support for AIDS research efforts by the institute, and NIH/NCRR grant RR-00165 to the Yerkes Primate Center. M.L.M. was supported by Public Health Service grant RR00169 from the National Center for Research Resources and is also the recipient of an Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation Scientist Award.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baba, T. W., Y. S. Jeong, D. Pennick, R. Bronson, M. F. Greene, and R. M. Ruprecht. 1995. Pathogenicity of live, attenuated SIV after mucosal infection of neonatal macaques.Science 267:1820–1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baba, T. W., V. Liska, A. H. Khimani, N. B. Ray, P. J. Dailey, D. Penninck, R. Bronson, M. F. Greene, H. M. McClure, L. N. Martin, and R. M. Ruprecht. 1999. Live attenuated, multiply deleted simian immunodeficiency virus causes AIDS in infant and adult macaques. Nat. Med. 5:194–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bray, M., S. Prasad, J. W. Dubay, E. Hunter, K.-T. Jeang, D. Rekosh, and M.-L. Hammarskjold. 1994. A small element from the Mason-Pfizer monkey virus genome makes human immunodeficiency virus type 1 expression and replication Rev-independent. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:1256–1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cullen, B. 1998. Retroviruses as model systems for the study of nuclear RNA export pathways. Virology 248:203–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeMaria, M. A., M. Casto, M. O”Connell, R. P. Johnson, and M. Rosenzweig. 2000. Characterization of lymphocyte subsets in rhesus macaques during the first year of life. Eur. J. Haematol. 65:245–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Desrosiers, R. C., J. D. Lifson, J. S. Gibbs, S. C. Czajak, A. Y. Howe, L. O. Arthur, and R. P. Johnson. 1998. Identification of highly attenuated mutants of simian immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 72:1431–1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Felber, B. K. 1998. Posttranscriptional control: A general and important regulatory feature of HIV-1 and other retroviruses, p. 101–122. In G. Myers (ed.), Viral regulatory structures and their degeneracies, vol. XXVIII. Addison-Wesley, Reading, Mass. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fultz, P. N., P. J. Vance, M. J. Endres, B. Tao, J. D. Dvorin, I. C. Davis, J. D. Lifson, D. C. Montefiori, M. Marsh, M. H. Malim, and J. A. Hoxie. 2001. In vivo attenuation of simian immunodeficiency virus by disruption of a tyrosine-dependent sorting signal in the envelope glycoprotein cytoplasmic tail. J. Virol. 75:278–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gauduin, M. C., R. L. Glickman, S. Ahmad, T. Yilma, and R. P. Johnson. 1999. Characterization of SIV-specific CD4+ T-helper proliferative responses in macaques immunized with live-attenuated SIV. J. Med. Primatol. 28:233–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gauduin, M. C., R. L. Glickman, S. Ahmad, T. Yilma, and R. P. Johnson. 1999. Immunization with live attenuated simian immunodeficiency virus induces strong type 1 T helper responses and beta-chemokine production. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:14031–14036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gibbs, J. S., D. A. Regier, and R. C. Desrosiers. 1994. Construction and in vitro properties of SIVmac mutants with deletions in ”nonessential“ genes. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 10:607–616. Errected and republished; article originally printed in AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grüter, P., C. Tabernero, C. von Kobbe, C. Schmitt, C. Saavedra, A. Bachi, M. Wilm, B. K. Felber, and E. Izaurralde. 1998. TAP, the human homolog of Mex67p, mediates CTE-dependent RNA export from the nucleus. Mol. Cell 1:649–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guan, Y., J. B. Whitney, M. Detorio, and M. A. Wainberg. 2001. Construction and in vitro properties of a series of attenuated simian immunodeficiency viruses with all accessory genes deleted. J. Virol. 75:4056–4067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guan, Y., J. B. Whitney, C. Liang, and M. A. Wainberg. 2001. Novel, live attenuated simian immunodeficiency virus constructs containing major deletions in leader RNA sequences. J. Virol. 75:2776–2785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hel, Z., D. Venzon, M. Poudyal, W. P. Tsai, L. Giuliani, R. Woodward, C. Chougnet, G. Shearer, J. D. Altman, D. Watkins, N. Bischofberger, A. Abimiku, P. Markham, J. Tartaglia, and G. Franchini. 2000. Viremia control following antiretroviral treatment and therapeutic immunization during primary SIV251 infection of macaques. Nat. Med. 6:1140–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herold, A., M. Suyama, J. P. Rodrigues, I. C. Braun, U. Kutay, M. Carmo-Fonseca, P. Bork, and E. Izaurralde. 2000. TAP (NXF1) belongs to a multigene family of putative RNA export factors with a conserved modular architecture. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:8996–9008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hurt, E., K. Strasser, A. Segref, S. Bailer, N. Schlaich, C. Presutti, D. Tollervey, and R. Jansen. 2000. Mex67p mediates nuclear export of a variety of RNA polymerase II transcripts. J. Biol. Chem. 275:8361–8368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson, R. P., J. D. Lifson, S. C. Czajak, K. S. Cole, K. H. Manson, R. Glickman, J. Yang, D. C. Montefiori, R. Montelaro, M. S. Wyand, and R. C. Desrosiers. 1999. Highly attenuated vaccine strains of simian immunodeficiency virus protect against vaginal challenge: inverse relationship of degree of protection with level of attenuation. J. Virol. 73:4952–4961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katahira, J., K. Strasser, A. Podtelejnikov, M. Mann, J. U. Jung, and E. Hurt. 1999. The Mex67p-mediated nuclear mRNA export pathway is conserved from yeast to human. EMBO J. 18:2593–2609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kestler, H. W., D. J. Ringler, K. Mori, D. L. Panicali, P. K. Sehgal, M. D. Daniel, and R. C. Desrosiers. 1991. Importance of the nef gene for maintenance of high virus loads and for development of AIDS. Cell 65:651–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liska, V., A. H. Khimani, R. Hofmann-Lehmann, A. N. Fink, J. Vlasak, and R. M. Ruprecht. 1999. Viremia and AIDS in rhesus macaques after intramuscular inoculation of plasmid DNA encoding full-length SIVmac239. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 15:445–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marthas, M. L., R. A. Ramos, B. L. Lohman, K. K. Van Rompay, R. E. Unger, C. J. Miller, B. Banapour, N. C. Pedersen, and P. A. Luciw. 1993. Viral determinants of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) virulence in rhesus macaques assessed by using attenuated and pathogenic molecular clones of SIVmac. J. Virol. 67:6047–6055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Montefiori, D. C., T. W. Baba, A. Li, M. Bilska, and R. M. Ruprecht. 1996. Neutralizing and infection-enhancing antibody responses do not correlate with the differential pathogenicity of SIVmac239delta3 in adult and infant rhesus monkeys. J. Immunol. 157:5528–5535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murphey-Corb, M., S. Ohkawa, B. Davison-Fairburn, L. N. Martin, G. B. Baskin, A. J. Langlois, M. McIntee, O. Narayan, and M. B. Gardner. 1992. A formalin-fixed whole SIV vaccine induces protective responses that are cross-protective and durable. AIDS Res. Hum. Ret 8:1475–1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nappi, F., R. Schneider, A. Zolotukhin, S. Smulevitch, D. Michalowski, J. Bear, B. K. Felber, and G. N. Pavlakis. 2001. Identification of a novel posttranscriptional regulatory element by using a rev- and RRE-mutated human immunodeficiency virus type 1 DNA proviral clone as a molecular trap. J. Virol. 75:4558–4569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Regier, D. A., and R. C. Desrosiers. 1990. The complete nucleotide sequence of a pathogenic molecular clone of simian immunodeficiency virus. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 6:1221–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saavedra, C., B. Felber, and E. Izaurralde. 1997. The simian retrovirus-1 constitutive transport element, unlike the HIV-1 RRE, uses factors required for cellular mRNA export. Curr. Biol. 7:619–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith, S. M., M. Khoroshev, P. A. Marx, J. Orenstein, and K. T. Jeang. 2001. Constitutively dead, conditionally live HIV-1 genomes: ex vivo implications for a live-virus vaccine. J. Biol. Chem. 276:32184–32190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stauber, R. H., K. Horie, P. Carney, E. A. Hudson, N. I. Tarasova, G. A. Gaitanaris, and G. N. Pavlakis. 1998. Development and applications of enhanced green fluorescent protein mutants. BioTechniques 24:462–466, 468–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suryanarayana, K., T. Wiltrout, G. Vasquez, V. Hirsch, and J. Lifson. 1998. Plasma SIV RNA viral load determination by real-time quantification of product generation in reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 14:183–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tabernero, C., A. S. Zolotukhin, J. Bear, R. Schneider, G. Karsenty, and B. K. Felber. 1997. Identification of an RNA sequence within an intracisternal-A particle element able to replace Rev-mediated posttranscriptional regulation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 71:95–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tabernero, C., A. S. Zolotukhin, A. Valentin, G. N. Pavlakis, and B. K. Felber. 1996. The posttranscriptional control element of the simian retrovirus type 1 forms an extensive RNA secondary structure necessary for its function. J. Virol. 70:5998–6011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tan, W., A. S. Zolotukhin, J. Bear, D. J. Patenaude, and B. K. Felber. 2000. The mRNA export in C. elegans is mediated by Ce-NXF-1, an ortholog of human TAP and S.cerevisiae Mex67p.RNA 6:1762–1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Valentin, A., G. Aldrovandi, A. S. Zolotukhin, S. W. Cole, J. A. Zack, G. N. Pavlakis, and B. K. Felber. 1997. Reduced viral load and lack of CD4 depletion in SCID-hu mice infected with Rev-independent clones of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 71:9817–9822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Rompay, K. K., P. J. Dailey, R. P. Tarara, D. R. Canfield, N. L. Aguirre, J. M. Cherrington, P. D. Lamy, N. Bischofberger, N. C. Pedersen, and M. L. Marthas. 1999. Early short-term 9-[2-(R)-(phosphonomethoxy)propyl]adenine treatment favorably alters the subsequent disease course in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected newborn rhesus macaques. J. Virol. 73:2947–2955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.von Gegerfelt, A. S., and B. K. Felber. 1997. Replacement of posttranscriptional regulation in SIVmac239 generated a Rev-independent infectious virus able to propagate in rhesus peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Virology 232:291–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.von Gegerfelt, A. S., V. Liska, N. B. Ray, H. M. McClure, R. M. Ruprecht, and B. K. Felber. 1999. Persistent infection of rhesus macaques by the Rev-independent Nef− SIVmac239: replication kinetics and genomic stability. J. Virol. 73:6159–6165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wyand, M. S., K. H. Manson, A. A. Lackner, and R. C. Desrosiers. 1997. Resistance of neonatal monkeys to live attenuated vaccine strains of simian immunodeficiency virus. Nat. Med. 3:32–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zolotukhin, A. S., A. Valentin, G. N. Pavlakis, and B. K. Felber. 1994. Continuous propagation of RRE− and Rev− RRE− human immunodeficiency virus type 1 molecular clones containing a cis-acting element of simian retrovirus type 1 in human peripheral blood lymphocytes. J. Virol. 68:7944–7952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]