Abstract

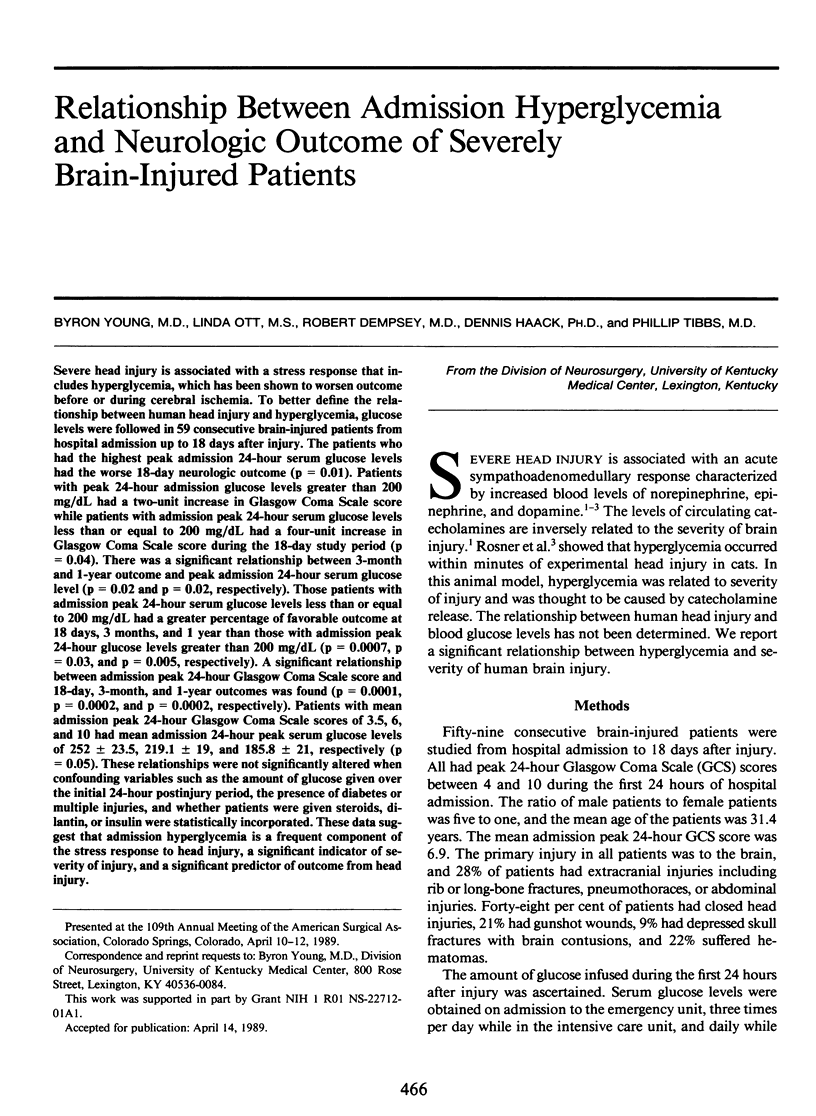

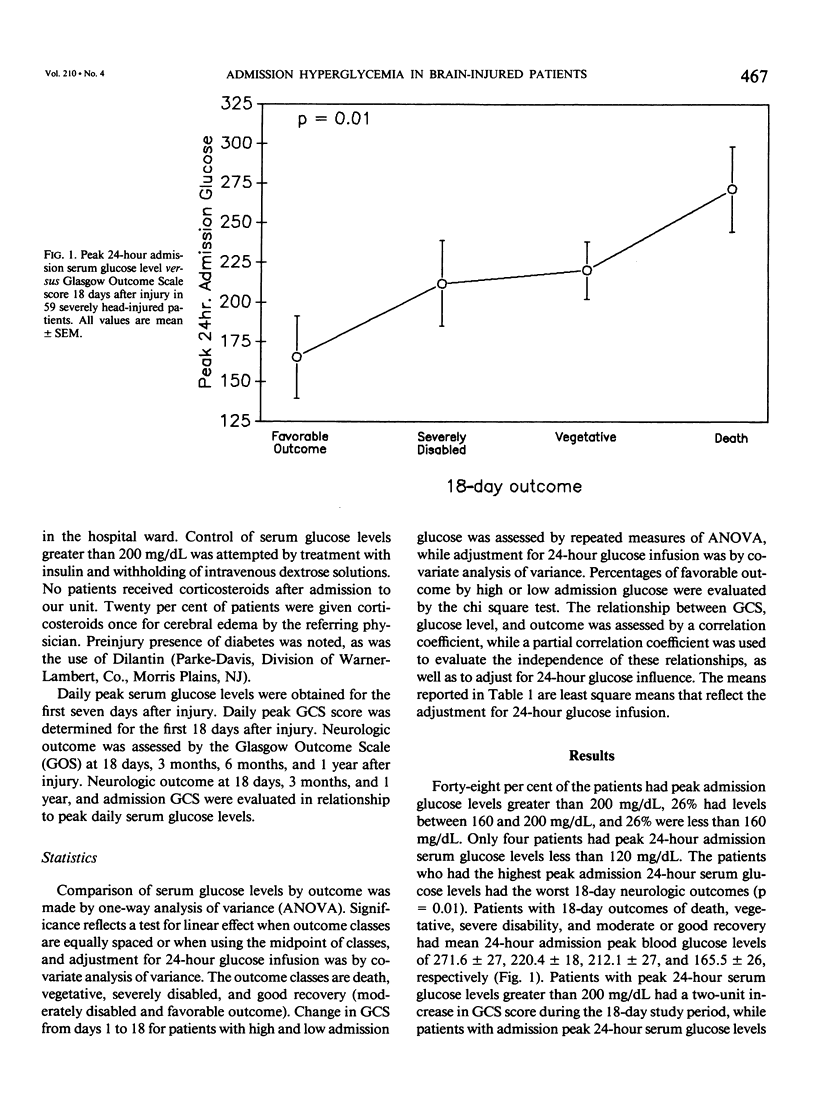

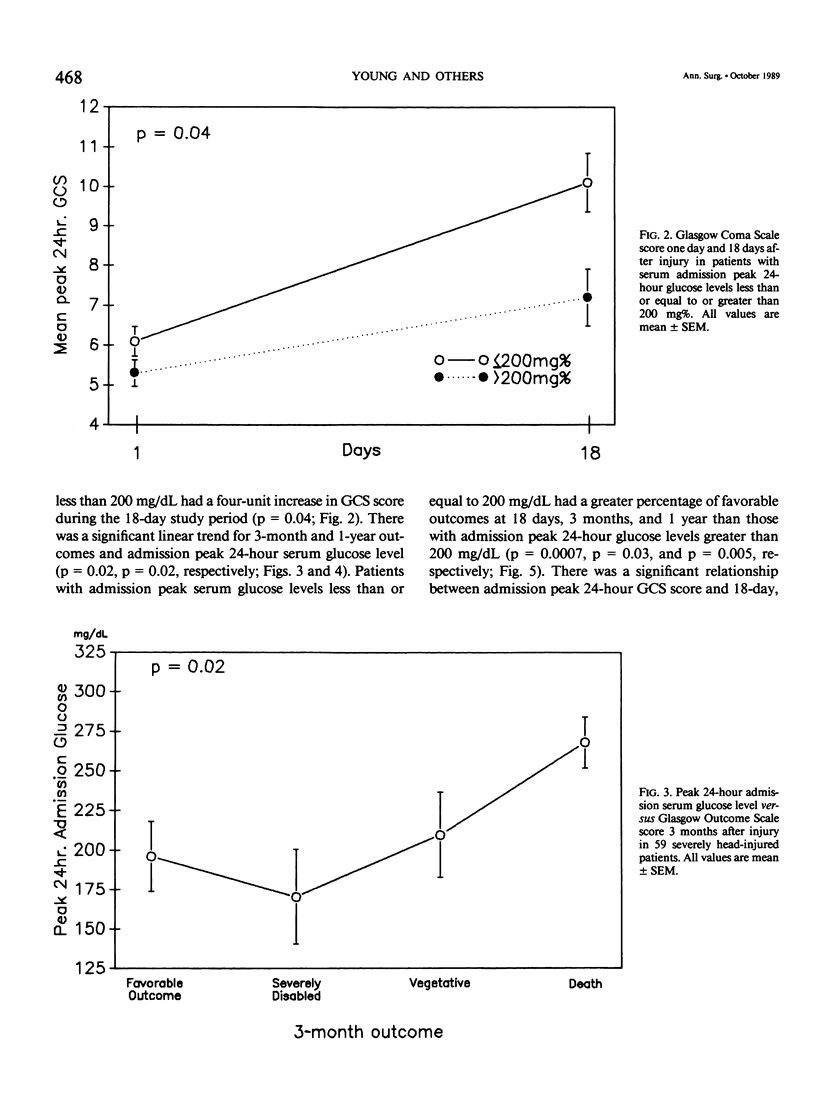

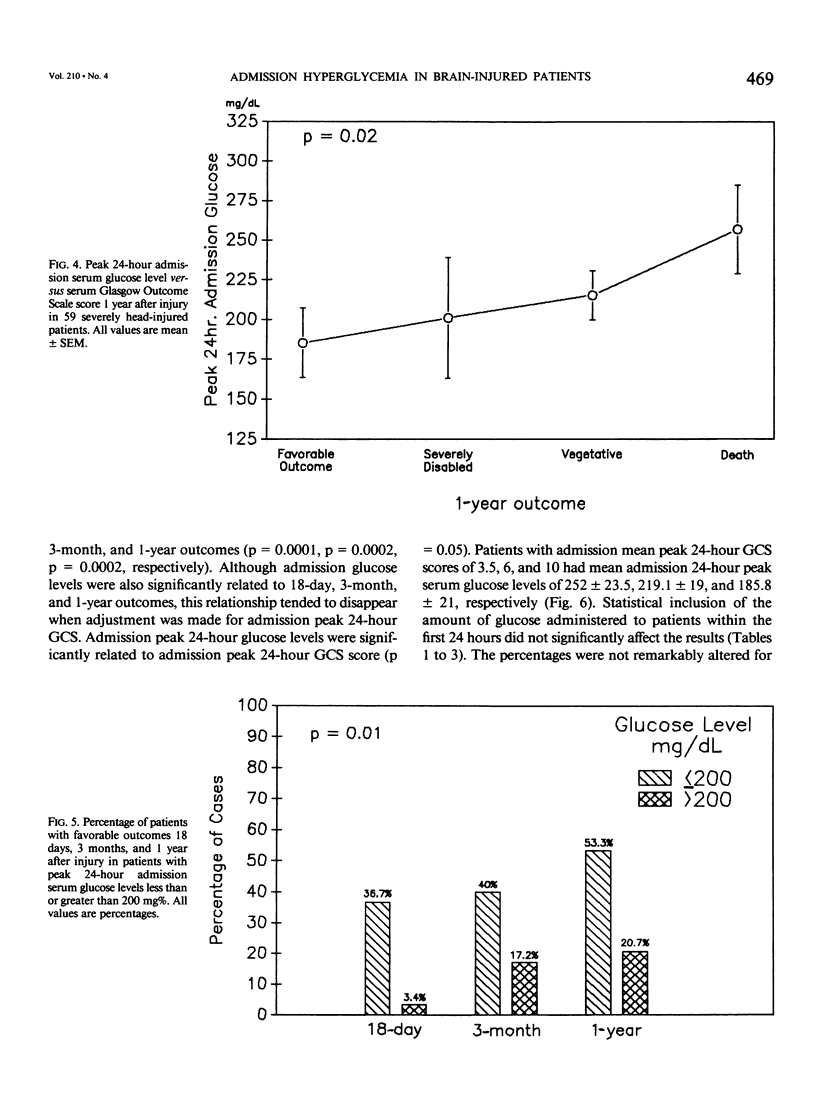

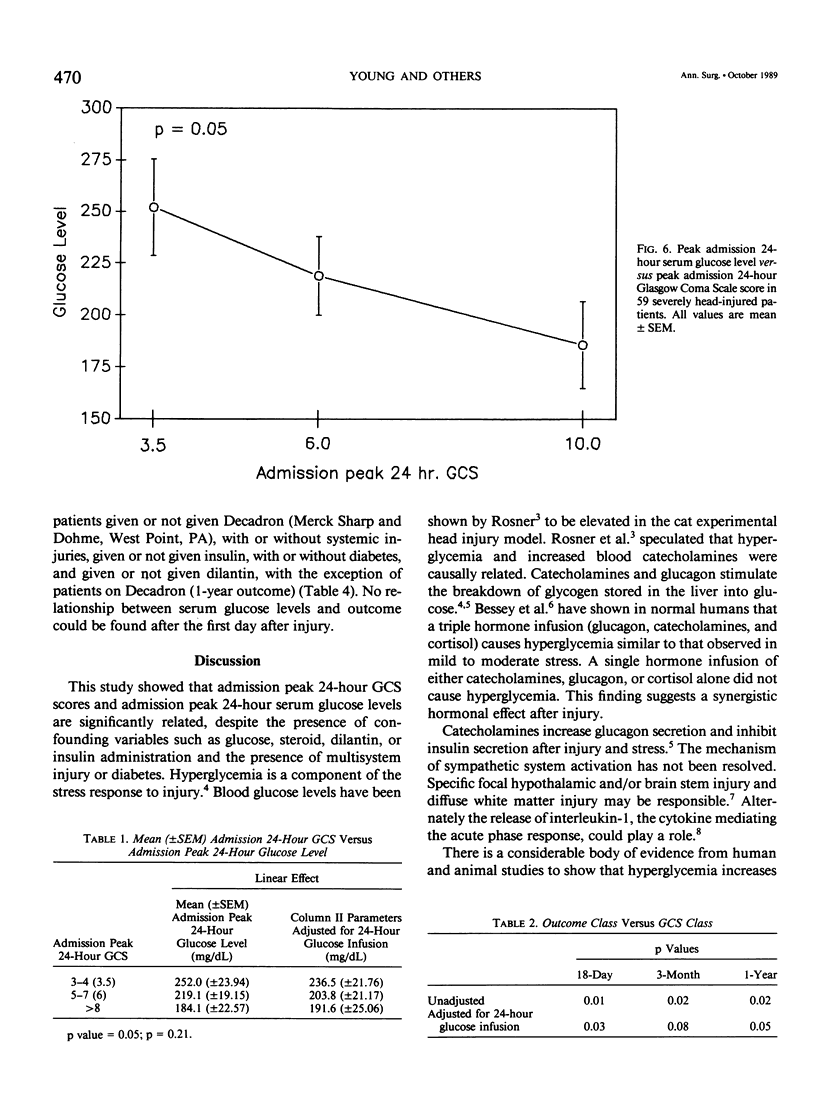

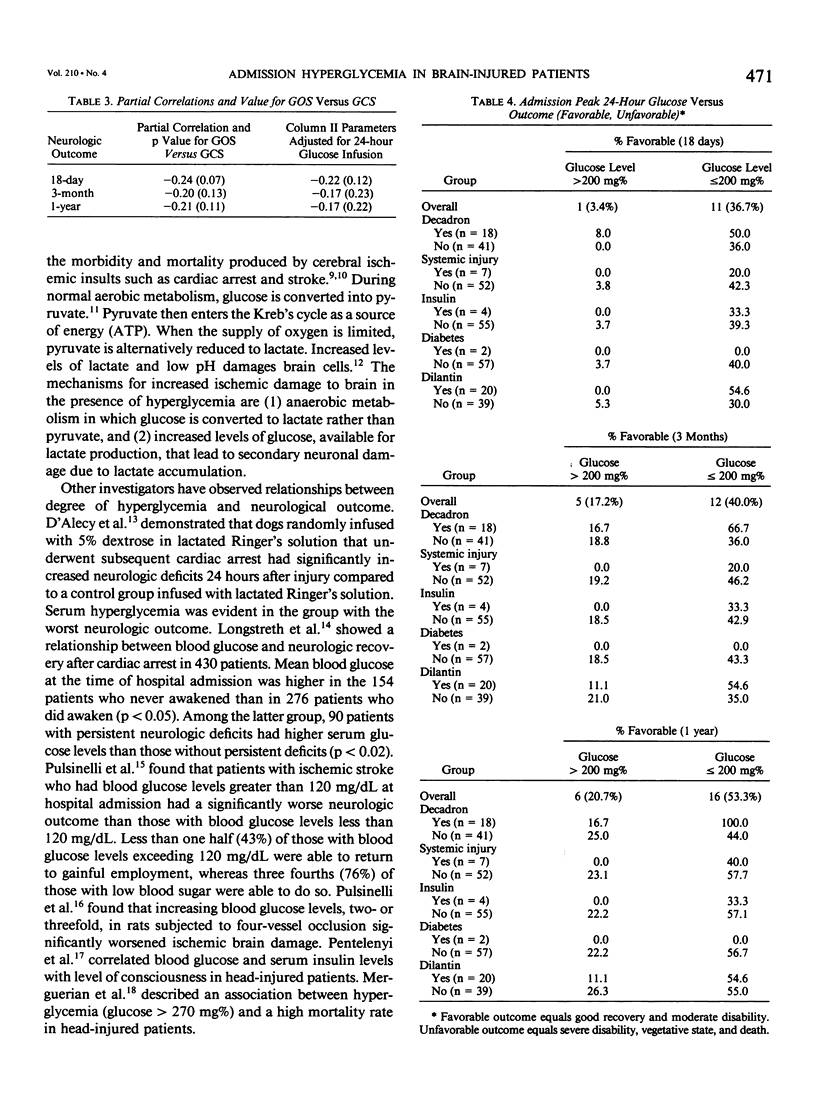

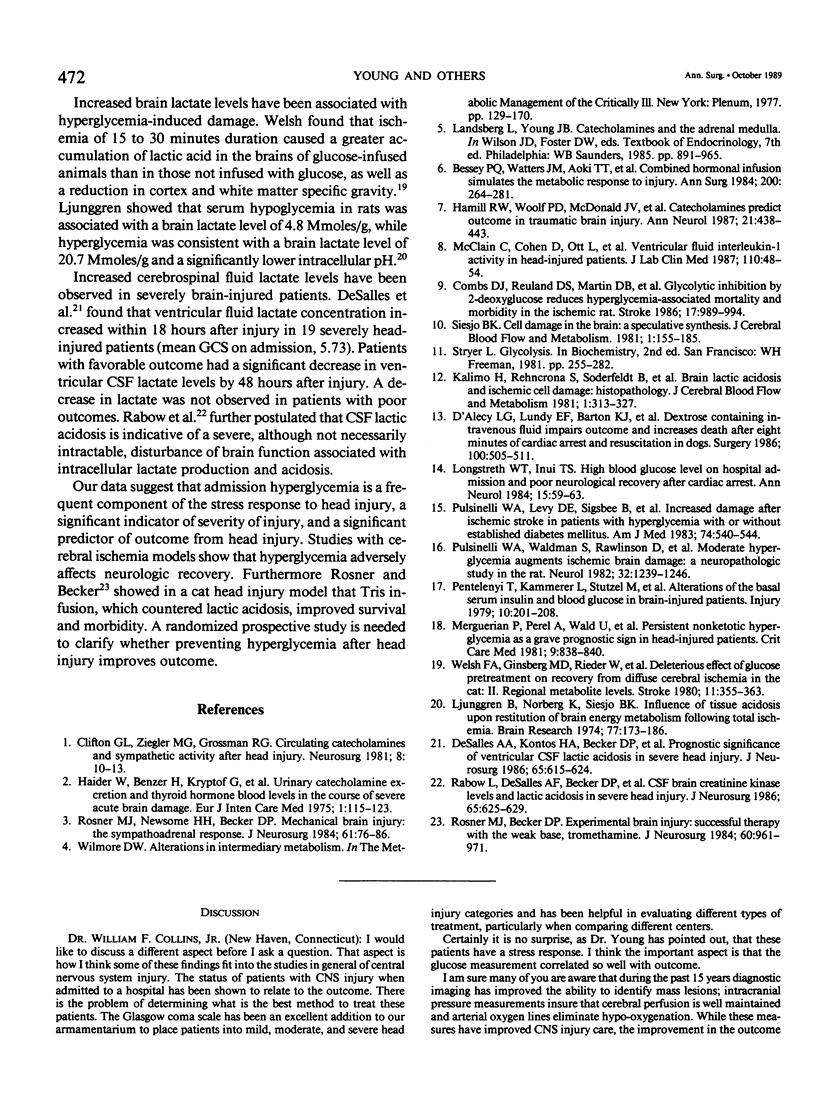

Severe head injury is associated with a stress response that includes hyperglycemia, which has been shown to worsen outcome before or during cerebral ischemia. To better define the relationship between human head injury and hyperglycemia, glucose levels were followed in 59 consecutive brain-injured patients from hospital admission up to 18 days after injury. The patients who had the highest peak admission 24-hour serum glucose levels had the worse 18-day neurologic outcome (p = 0.01). Patients with peak 24-hour admission glucose levels greater than 200 mg/dL had a two-unit increase in Glasgow Coma Scale score while patients with admission peak 24-hour serum glucose levels less than or equal to 200 mg/dL had a four-unit increase in Glasgow Coma Scale score during the 18-day study period (p = 0.04). There was a significant relationship between 3-month and 1-year outcome and peak admission 24-hour serum glucose level (p = 0.02 and p = 0.02, respectively). Those patients with admission peak 24-hour serum glucose levels less than or equal to 200 mg/dL had a greater percentage of favorable outcome at 18 days, 3 months, and 1 year than those with admission peak 24-hour glucose levels greater than 200 mg/dL (p = 0.0007, p = 0.03, and p = 0.005, respectively). A significant relationship between admission peak 24-hour Glasgow Coma Scale score and 18-day, 3-month, and 1-year outcomes was found (p = 0.0001, p = 0.0002, and p = 0.0002, respectively). Patients with mean admission peak 24-hour Glasgow Coma Scale scores of 3.5, 6, and 10 had mean admission 24-hour peak serum glucose levels of 252 +/- 23.5, 219.1 +/- 19, and 185.8 +/- 21, respectively (p = 0.05). These relationships were not significantly altered when confounding variables such as the amount of glucose given over the initial 24-hour postinjury period, the presence of diabetes or multiple injuries, and whether patients were given steroids, dilantin, or insulin were statistically incorporated. These data suggest that admission hyperglycemia is a frequent component of the stress response to head injury, a significant indicator of severity of injury, and a significant predictor of outcome from head injury.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bessey P. Q., Watters J. M., Aoki T. T., Wilmore D. W. Combined hormonal infusion simulates the metabolic response to injury. Ann Surg. 1984 Sep;200(3):264–281. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198409000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifton G. L., Ziegler M. G., Grossman R. G. Circulating catecholamines and sympathetic activity after head injury. Neurosurgery. 1981 Jan;8(1):10–14. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198101000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combs D. J., Reuland D. S., Martin D. B., Zelenock G. B., D'Alecy L. G. Glycolytic inhibition by 2-deoxyglucose reduces hyperglycemia-associated mortality and morbidity in the ischemic rat. Stroke. 1986 Sep-Oct;17(5):989–994. doi: 10.1161/01.str.17.5.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Alecy L. G., Lundy E. F., Barton K. J., Zelenock G. B. Dextrose containing intravenous fluid impairs outcome and increases death after eight minutes of cardiac arrest and resuscitation in dogs. Surgery. 1986 Sep;100(3):505–511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSalles A. A., Kontos H. A., Becker D. P., Yang M. S., Ward J. D., Moulton R., Gruemer H. D., Lutz H., Maset A. L., Jenkins L. Prognostic significance of ventricular CSF lactic acidosis in severe head injury. J Neurosurg. 1986 Nov;65(5):615–624. doi: 10.3171/jns.1986.65.5.0615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haider W., Benzer H., Krystof G., Lackner F., Mayrhofer O., Steinbereithner K., Irsigler K., Korn A., Schlick W., Binder H. Urinary catecholamine excretion and thyroid hormone blood level in the course of severe acute brain damage. Eur J Intensive Care Med. 1975 Nov;1(3):115–123. doi: 10.1007/BF00571658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill R. W., Woolf P. D., McDonald J. V., Lee L. A., Kelly M. Catecholamines predict outcome in traumatic brain injury. Ann Neurol. 1987 May;21(5):438–443. doi: 10.1002/ana.410210504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalimo H., Rehncrona S., Söderfeldt B., Olsson Y., Siesjö B. K. Brain lactic acidosis and ischemic cell damage: 2. Histopathology. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1981;1(3):313–327. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1981.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ljunggren B., Norberg K., Siesjö B. K. Influence of tissue acidosis upon restitution of brain energy metabolism following total ischemia. Brain Res. 1974 Sep 6;77(2):173–186. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(74)90782-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longstreth W. T., Jr, Inui T. S. High blood glucose level on hospital admission and poor neurological recovery after cardiac arrest. Ann Neurol. 1984 Jan;15(1):59–63. doi: 10.1002/ana.410150111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClain C. J., Cohen D., Ott L., Dinarello C. A., Young B. Ventricular fluid interleukin-1 activity in patients with head injury. J Lab Clin Med. 1987 Jul;110(1):48–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merguerian P. A., Perel A., Wald U., Feinsod M., Cotev S. Persistent nonketotic hyperglycemia as a grave prognostic sign in head-injured patients. Crit Care Med. 1981 Dec;9(12):838–840. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198112000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pentelényi T., Kammerer L., Stützel M., Balázsi I. Alterations of the basal serum insulin and blood glucose in brain-injured patients. Injury. 1979 Feb;10(3):201–208. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(79)90009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulsinelli W. A., Levy D. E., Sigsbee B., Scherer P., Plum F. Increased damage after ischemic stroke in patients with hyperglycemia with or without established diabetes mellitus. Am J Med. 1983 Apr;74(4):540–544. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(83)91007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulsinelli W. A., Waldman S., Rawlinson D., Plum F. Moderate hyperglycemia augments ischemic brain damage: a neuropathologic study in the rat. Neurology. 1982 Nov;32(11):1239–1246. doi: 10.1212/wnl.32.11.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabow L., DeSalles A. F., Becker D. P., Yang M., Kontos H. A., Ward J. D., Moulton R. J., Clifton G., Gruemer H. D., Muizelaar J. P. CSF brain creatine kinase levels and lactic acidosis in severe head injury. J Neurosurg. 1986 Nov;65(5):625–629. doi: 10.3171/jns.1986.65.5.0625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosner M. J., Becker D. P. Experimental brain injury: successful therapy with the weak base, tromethamine. With an overview of CNS acidosis. J Neurosurg. 1984 May;60(5):961–971. doi: 10.3171/jns.1984.60.5.0961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosner M. J., Newsome H. H., Becker D. P. Mechanical brain injury: the sympathoadrenal response. J Neurosurg. 1984 Jul;61(1):76–86. doi: 10.3171/jns.1984.61.1.0076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siesjö B. K. Cell damage in the brain: a speculative synthesis. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1981;1(2):155–185. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1981.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh F. A., Ginsberg M. D., Rieder W., Budd W. W. Deleterious effect of glucose pretreatment on recovery from diffuse cerebral ischemia in the cat. II. Regional metabolite levels. Stroke. 1980 Jul-Aug;11(4):355–363. doi: 10.1161/01.str.11.4.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]