Abstract

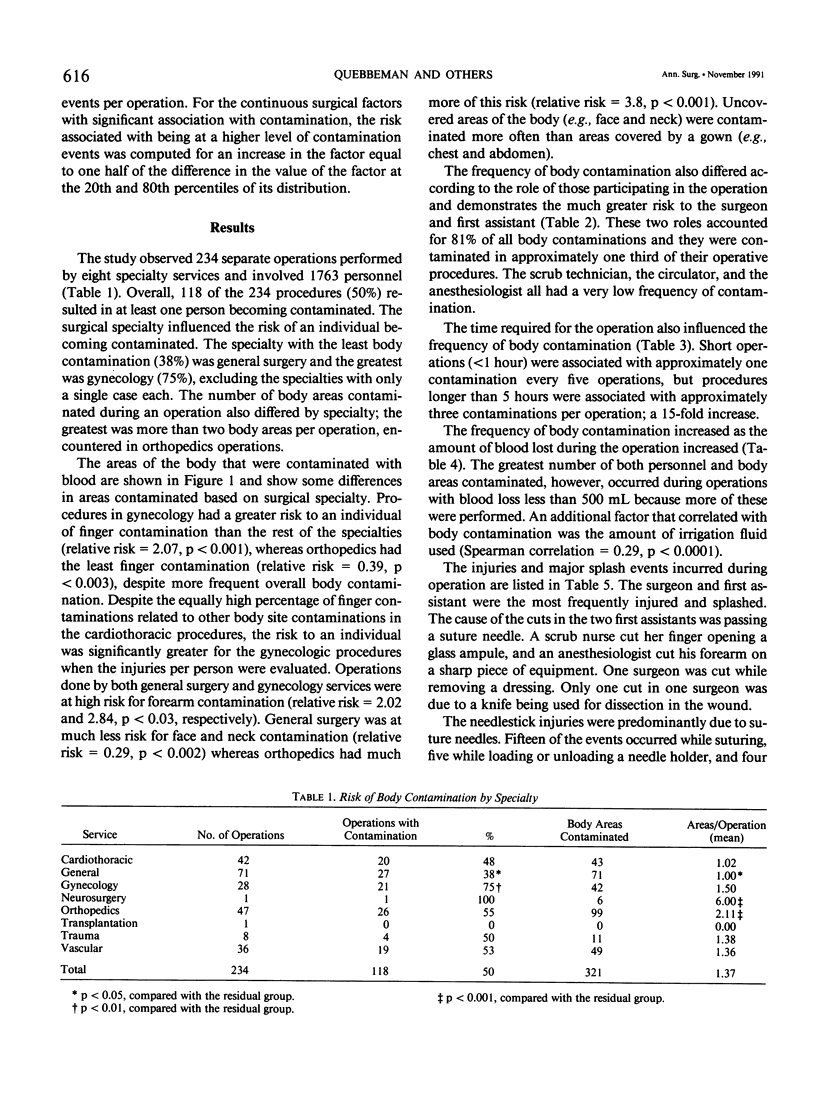

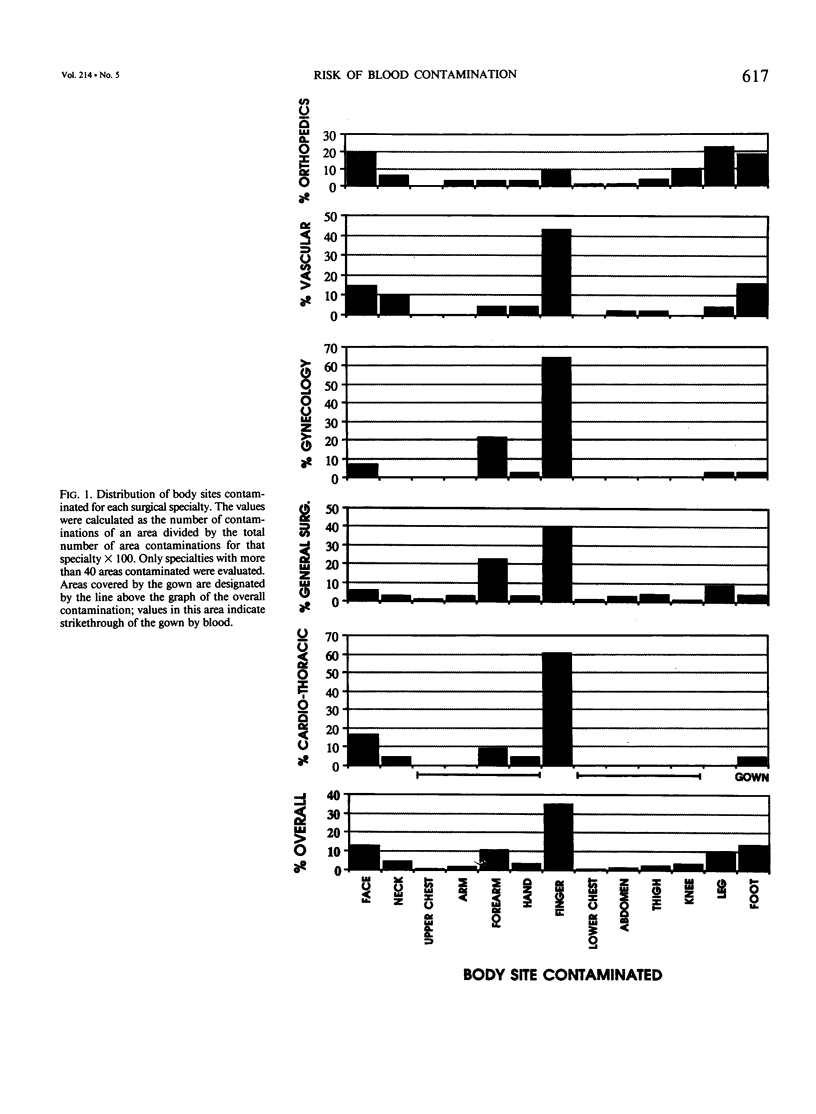

The potential for transmission of deadly viral diseases to health care workers exists when contaminated blood is inoculated through injury or when blood comes in contact with nonintact skin. Operating room personnel are at particularly high risk for injury and blood contamination, but data on the specifics of which personnel are at greater risk and which practices change risk in this environment are almost nonexistent. To define these risk factors, experienced operating room nurses were employed solely to observe and record the injuries and blood contaminations that occurred during 234 operations involving 1763 personnel. Overall 118 of the operations (50%) resulted in at least one person becoming contaminated with blood. Cuts or needlestick injuries occurred in 15% of the operations. Several factors were found to significantly alter the risk of blood contamination or injury: surgical specialty, role of each person, duration of the procedure, amount of blood loss, number of needles used, and volume of irrigation fluid used. Risk calculations that use average values to include all personnel in the operating room or all operations performed substantially underestimate risk for surgeons and first assistants, who accounted for 81% of all body contamination and 65% of the injuries. The area of the body contaminated also changed with the surgical specialty. These data should help define more appropriate protection for individuals in the operating room and should allow refinements of practices and techniques to decrease injury.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Agresti A. Tutorial on modeling ordered categorical response data. Psychol Bull. 1989 Mar;105(2):290–301. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.105.2.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong B. G., Sloan M. Ordinal regression models for epidemiologic data. Am J Epidemiol. 1989 Jan;129(1):191–204. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bessinger C. D., Jr Preventing transmission of human immunodeficiency virus during operations. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1988 Oct;167(4):287–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerberding J. L., Littell C., Tarkington A., Brown A., Schecter W. P. Risk of exposure of surgical personnel to patients' blood during surgery at San Francisco General Hospital. N Engl J Med. 1990 Jun 21;322(25):1788–1793. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199006213222506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagen M. D., Meyer K. B., Pauker S. G. Routine preoperative screening for HIV. Does the risk to the surgeon outweigh the risk to the patient? JAMA. 1988 Mar 4;259(9):1357–1359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamory B. H. Underreporting of needlestick injuries in a university hospital. Am J Infect Control. 1983 Oct;11(5):174–177. doi: 10.1016/0196-6553(83)90077-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain S. A., Latif A. B., Choudhary A. A. Risk to surgeons: a survey of accidental injuries during operations. Br J Surg. 1988 Apr;75(4):314–316. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800750407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagger J., Hunt E. H., Brand-Elnaggar J., Pearson R. D. Rates of needle-stick injury caused by various devices in a university hospital. N Engl J Med. 1988 Aug 4;319(5):284–288. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198808043190506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowenfels A. B., Wormser G. P., Jain R. Frequency of puncture injuries in surgeons and estimated risk of HIV infection. Arch Surg. 1989 Nov;124(11):1284–1286. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1989.01410110038007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matta H., Thompson A. M., Rainey J. B. Does wearing two pairs of gloves protect operating theatre staff from skin contamination? BMJ. 1988 Sep 3;297(6648):597–598. doi: 10.1136/bmj.297.6648.597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney W. P., Young M. J. The cumulative probability of occupationally-acquired HIV infection: the risks of repeated exposures during a surgical career. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1990 May;11(5):243–247. doi: 10.1086/646161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roach P. J., Fleming C., Hagen M. D., Pauker S. G. Prostatic cancer in a patient with asymptomatic HIV infection: are some lives more equal than others? Med Decis Making. 1988 Apr-Jun;8(2):132–144. doi: 10.1177/0272989X8800800209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schecter W. P. HIV transmission to surgeons. Assessment of risk, infection control precautions, and standards of conduct. Occup Med. 1989;4 (Suppl):65–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]