Abstract

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) immediate-early protein IE1/IE72 is involved in undermining many cellular processes including cell cycle regulation, apoptosis, nuclear architecture, and gene expression. The multifunctional nature of IE72 suggests that posttranslational modifications may modulate its activities. IE72 is a phosphoprotein and has intrinsic kinase activity (S. Pajovic, E. L. Wong, A. R. Black, and J. C. Azizkhan, Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:6459-6464, 1997). We now demonstrate that IE72 is covalently conjugated to the small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO-1). SUMO-1 is an 11.5-kDa protein that is conjugated to multiple proteins and has been reported to exhibit multiple effects, including modulation of protein stability, subcellular localization, and gene expression. A covalently modified protein migrating at ∼92 kDa, which is stabilized by a SUMO-1 hydrolase inhibitor, is revealed by Western blotting with anti-IE72 of lysates from cells infected with HCMV or cells expressing IE72. SUMO modification of IE72 was confirmed by immunoprecipitation with anti-IE72 and anti-SUMO-1 followed by Western blotting with anti-SUMO-1 and anti-IE72, respectively. Lysine 450 is within a sumoylation consensus site (I,V,L)KXE; changing lysine 450 to arginine by point mutation abolishes SUMO-1 modification of IE72. Inhibition of protein phosphatase 1 and 2A, which increases the phosphorylation of IE72, suppresses the formation of SUMO-1-IE72 conjugates. Both wild-type IE72 and IE72K450R localize to nuclear PML oncogenic domains and disrupt them. Studies of protein stability, transactivation, and complementation of IE72-deficient HCMV (CR208) have revealed no significant differences between wild-type IE72 and IE72K450R.

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is a member of the herpesvirus family, exhibiting a narrow host range and a characteristic temporal cascade of gene expression in permissive cells. While HCMV poses a low threat to healthy individuals, it is life threatening to the immunocompromised, including prenatally infected newborns and AIDS patients (3).

Primary transcripts from the major immediate-early region undergo alternative splicing to yield two major gene products. The 1.95-kb IE1 transcript is comprised of exons 1 to 4 and gives rise to the abundant IE72 gene product. This 491-amino-acid protein is present throughout HCMV infection (42). The IE2 transcript is comprised of exons 1, 2, 3, and 5 and encodes IE86, which is a promiscuous transactivator of both viral and cellular promoters. During infection, IE72 and IE86 are the first and most abundantly expressed proteins and are required for the subsequent induction of the early and late genes. IE72 and IE86 contain a common transactivation domain encoded within exon 3, which encodes amino acids 25 to 85 of both proteins (37). IE86 and IE72 independently and synergistically activate heterologous promoters (8, 9, 16, 48). Cellular permissiveness for HCMV infection requires IE72 transactivation of the major immediate-early protein enhancer through the NF-κB site (43). Thus, both IE86 and IE72 are major gene regulatory factors that play essential roles in HCMV infection.

We have discovered that IE72 is a viral kinase capable of phosphorylating itself, as well as E2F-1, -2, and -3 and the pocket proteins p107 and p130, but not E2F-4 or -5 or pRb (36). The important role that IE72 plays in HCMV lytic growth is underscored by the fact that a recombinant virus bearing a deletion of exon 4 in the major immediate-early region is severely impaired for replication at a low multiplicity of infection (MOI) (30). This block in DNA replication correlates with a defect in the accumulation of ppUL44, an early gene product required for viral DNA polymerase, and failure to form DNA replication compartments, which may be related to a failure to disrupt the nuclear structures referred to as PML oncogenic domains (PODs) (2), nuclear domain 10, or nuclear dots; these defects can be corrected when IE72 is supplied in trans (2, 15, 50).

IE72 is involved in viral effects on numerous cellular processes including gene regulation, cell cycle progression, signal transduction, POD dispersal, and apoptosis (2, 25, 27, 32, 50, 52). Posttranslational modifications are common mechanisms for the regulation of multifunctional proteins. Our studies have determined that IE72 is autophosphorylated (36) and is also phosphorylated at distinct sites by a cellular kinase(s) (C. Himmelheber and J. Azizkhan-Clifford, unpublished data). The present investigation demonstrates that IE72 exhibits a novel posttranslational modification in which the small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO-1) is covalently attached to lysine 450 of IE72.

SUMO-1 (also known as sentrin, GMP1, PIC1, and Ubl1, or in Saccharomyces cerevisiae as SMt3), a ubiquitin-like protein sharing 48% homology with ubiquitin (5), functions as an important reversible protein modifier. Since the discovery of SUMO-1 in 1996, the list of proteins that have been reported to be SUMO-1 modified has been expanding (see reference 51 for a review); many SUMO-modified proteins are associated with PODs. The major POD structural component, promyelocytic leukemia protein (PML), was first discovered in acute promyelocytic leukemia patients exhibiting a chromosomal translocation, t(15;17), that fuses the retinoic acid receptor to PML (7, 11, 14, 22). PODs have more recently been identified as sites of cellular and viral replication processes (26). While POD organization has been linked to cell transformation, PODs are the target for a variety of viral proteins, and the loss of POD organization is thought to be important in the viral infection cycle (see references 1 and 18 for reviews). SUMO-1 conjugation accounts for specific effects, including altered stability, gene regulation, subcellular localization, and protein-protein interactions (10, 19, 24, 39). For example, the SUMO-1 conjugation of PML was reported to function as a POD targeting signal (34), whereas SUMO-1 modification of RanGAP1 enables its interaction at the nuclear pore complex and SUMO-1 modification of p53 increases its transactivation activity. In this study, we have mapped the site of SUMO modification on IE72 to lysine 450 and have demonstrated that IE72 sumoylation is not involved in the ability of IE72 to target or disrupt PODs, nor does it appear to significantly alter IE72 stability, transactivation activity, or ability to complement IE72-deficient HCMV. The precise role of IE72 sumoylation remains to be determined.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

Glioblastoma cells (U373-MG) and human foreskin fibroblasts (HFF) were used for HCMV infection and for the expression of HCMV IE72. Cells were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM), supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine, 10% fetal calf serum, and penicillin-streptomycin (100 μg/ml), in a humidified 10% CO2 incubator at 37°C. The human embryonic kidney cell line 293 was used to propagate recombinant adenovirus (49). HCMV was propagated in HFF as described elsewhere (35). Calyculin A (Sigma) was prepared as a 10 μM stock solution in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO); the final concentration for cell treatment was 0.1 μM.

HCMV infection.

HCMV stocks were prepared from HFF cells infected at an MOI of 0.1 PFU per cell. An inoculum in 2% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS)-DMEM was allowed to adsorb to cells for 4 to 6 days. Medium was collected from cells displaying approximately 75% cytopathic effects and centrifuged at 1,800 × g for 10 min to remove cell debris. Aliquots of the stock supernatant were frozen at −90°C. Plaque assays were performed, and titers were calculated as PFU per milliliter. IE72-deficient HCMV from which the exon 4 region was deleted (CR208) was generously supplied by Richard Greaves (15).

Adenovirus infection.

The recombinant adenoviruses rAdLacZ (rAd35) and rAdIE72 (rAd31) were kindly provided by Gavin Wilkinson (49). The Escherichia coli lacZ and the HCMV IE72 cDNA were expressed under the control of the HCMV major immediate-early promoter. HFF cells were infected with adenovirus at an MOI of 30 PFU/cell, in a minimal volume of 2% heat-inactivated FBS-DMEM for at least 24 h.

Retrovirus infection.

Amphotrophic Phoenix cells were used to package recombinant retroviruses according to instructions found at http://www.standford.edu/group/nolan/.

Phoenix cells (5 × 106/10-cm culture dish) were plated 24 h prior to infection. Chloroquine (25 μM) was added 5 min before Phoenix cells were transfected with 20 μg of the retrovirus plasmid construct by the calcium phosphate coprecipitation method (4). Cells were incubated at 32°C overnight, followed by a wash in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and an additional 24 h of incubation at 32°C in medium containing 10% FBS. The medium was cleared and used immediately to infect HFF that were plated the night before at 1.5 × 105 cells/well in six-well dishes and incubated for 6 to 8 h in sodium phosphate-free DMEM supplemented with 10% dialyzed FBS. Retrovirus supernatant (1 ml/well), supplemented with 5 μg of Polybrene/ml, was added to the cells and incubated at 32°C for 24 h. Cells were then washed and incubated in DMEM-10% FBS at 37°C for 24 h.

Plasmids.

The pSG5 plasmids containing cDNA encoding wild-type IE72 or deletion mutant Δaa 421-486 were kindly provided by John Sinclair (17). The IE72 point mutant in which lysine 450 was replaced with arginine was constructed using pSG-IE72 as template and the two-step PCR mutagenesis technique. The first round consisted of two separate PCRs to generate the 5′ and 3′ ends of the gene with the desired mutation. The 5′ end was made using the primers 5′-AGCAATTCGGATCCATGGAGTCCTCTGCCAAGAG-3′ (5′ IE-1 primer) and 5′-GTGTCTGTCAGGTCTGAGCCA-3′. The 3′ end was made with the primers 5′-ACGAATTCGGATCCTGATTAGTGGGATCCATAACAGTAAC-3′ (3′ IE-1 primer) and 5′-TGGCTCAGACCTGACAGACAC-3′. pSG-IE72 was the template in both reactions. The products from these PCRs were gel purified and used as templates for the second-round PCR with both the 5′ and 3′ IE-1 primers. The final 1.5-kb fragment was digested with AflII and PflMI, and the resulting 530-bp fragment was ligated into a pSG-IE72 backbone which had been digested with the same enzymes. The final recombinant plasmid was verified by sequencing. The IE72 wild-type and mutant constructs, as well as the dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) reporter plasmids employed for luciferase assays, have been previously described (6, 25).

The LXSG retrovirus vector was obtained from Dusty Miller. LXSG was constructed from LXSN (29) by replacement of the neomycin phosphotransferase cDNA (neo) with enhanced green fluorescent protein (a variant of green fluorescent protein; Clontech). LXSG-IE72 was created by subcloning the blunt-ended SacI/BamHI IE72 cDNA fragment from pRSV-IE72 into the blunt-ended XhoI and BamHI sites of LXSG vector, downstream of the Moloney murine leukemia virus promoter (long terminal repeat [LTR]). LXSG IE72K450R was constructed using Stratagene's Quik Change site-directed mutagenesis kit. Briefly, the oligonucleotide primers used to construct pSG-IE72K450R were annealed to the LXSG IE72 template. By using the non-strand-displacing action of Pfu Turbo DNA polymerase, the mutagenic primers were extended, resulting in nicked circular strands. The nonmutated methylated parental DNA template was digested with DpnI, and the circular, double-stranded DNA was transformed into competent cells.

Antibodies.

Polyclonal antiserum directed against IE72 and IE86 was generated by immunizing rabbits with a polypeptide corresponding to amino acids 12 to 25 (pAb543). Polyclonal antibody that specifically recognizes IE72 (1-2) was obtained from Jay Nelson. The monoclonal antibody BS500, which recognizes an epitope in IE72 (amino acid residues 389 to 425), was generously provided by Bodo Plachter (Johannes Gutenberg-Universitat Mainz). Monoclonal antibody directed against SUMO-1 was purchased from Zymed Laboratories. Roel Van Driel (University of Amsterdam) generously supplied us with a monoclonal antibody directed against PML (5E10) (45).

Western blotting and immunoprecipitation analysis.

Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS] in PBS) or in 50 mM Tris (pH 6.8)-2% SDS-10% glycerol supplemented with 20 μM N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) followed by centrifugation at 4°C at 14,000 × g for 20 min. The supernatant was incubated with the appropriate primary antibody and protein A- or protein G-Sepharose for 3 to 4 h at 4°C. The beads were collected and washed in RIPA buffer three times, before being boiled in SDS sample buffer for analysis by Western blotting. Proteins were separated by SDS-8% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and electrophoretically transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Schleicher & Schuell). Membranes were blocked with 3% fat-free dried milk in PBS supplemented with 0.1% Tween 20 and then incubated with the appropriate primary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. Subsequently, membranes were incubated with a secondary antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase. Each of the incubation steps was followed by three washes for 5 min in PBS-0.1% Tween. Development was performed with Super Signal according to the manufacturer's protocol (Pierce).

Indirect immunofluorescence analysis.

U373 cells were grown overnight on coverslips in 35-mm six-well plates. At 48 h posttransfection, cells were washed in PBS and fixed with 2% formaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature. Cells were permeabilized in 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min, followed by incubation for 1 h at room temperature with the appropriate primary antibody (1/500 dilution of the polyclonal antibody directed against IE72; 1/100 dilution of the monoclonal antibody directed against PML). After three washes in PBS-Triton, cells were incubated at room temperature with the appropriate secondary antibodies: anti-mouse tetramethyl rhodamine isothiocyanate and anti-rabbit fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson Labs). Cells were mounted by using Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories) and analyzed with a fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss, Inc.) equipped with the appropriate optics and filter modules, and results were recorded with a digital camera (SPOT; Diagnostic Instruments Inc.).

Complementation assay.

Phoenix cells were transfected with 20 μg each of LXSG empty vector, LXSG-IE72, or LXSG-IE72K450R by the calcium phosphate coprecipitation method and cultured at 32°C overnight. At 24 h posttransfection, cells were washed and cultured overnight in 5 ml of DMEM for 24 h at 32°C. At 48 h posttransfection, retrovirus was collected and used immediately to infect HFF plated at 1.5 × 105/well on a six-well dish. Forty-eight hours later, cells were infected with 200 μl of a 1:103 dilution of the HCMV ΔIE72 (CR208) stock at 1.6 × 105 PFU/ml, followed by addition of an agarose overlay. Cells were monitored daily for plaques, whereupon they were fixed, stained, and counted.

RESULTS

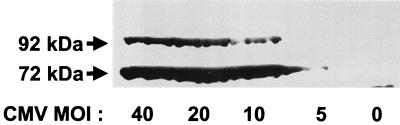

Western blot analysis detects two major forms of IE72.

Western blotting using anti-IE72 (monoclonal antibody against amino acid residues 389 to 425), which does not cross-react with IE86, revealed two major protein species in HCMV-infected HFF cells. A major protein that migrates with an apparent molecular mass of 72 kDa, as well as an additional protein that migrates at approximately 92 kDa, was detected (Fig. 1). This apparent 20-kDa molecular mass increase in IE72 is consistent with SUMO-1 conjugation, which induces a characteristic 20-kDa mobility shift (10, 23). The 92-kDa form of IE72 is highly sensitive to conditions of lysis and is seen only if cells are lysed under denaturing conditions, such as 2% SDS or 6 M guanidine HCl. Under these conditions, as much as one-third of the total IE72 is in the 92-kDa form. Western blot analysis was performed on lysates from several different cell types, including HFF and U373 cells infected with either HCMV or recombinant adenovirus expressing IE72 or transduced with a retrovirus expressing IE72. Several different monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies were found to detect the 92-kDa form of IE72 (data not shown). There was no detection of either form of IE72 in U373 or HFF cells that were infected with CR208, a mutated version of HCMV that does not express IE72, or in cells infected with the recombinant adenovirus expressing β-galactosidase or transduced with the control retrovirus empty vector (LXSG).

FIG. 1.

Two forms of IE72 with apparent molecular masses of 72 and ∼92 kDa can be detected in HCMV-infected cells. HFF cells were infected with HCMV at the indicated MOI. Cell lysates were prepared by direct lysis in SDS sample buffer and subjected to Western blotting with anti-IE72 (BS500). In addition to the major IE72 band migrating at 72 kDa, a significant band cross-reacting with IE72-specific antibody was detected at ∼92 kDa. Mock-treated cells do not show either protein.

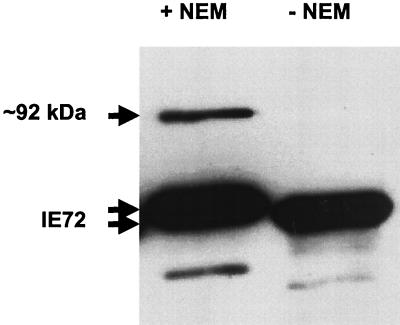

Detection of the ∼92-kDa IE72 protein after immunoprecipitations.

The 92-kDa form of IE72 was not detected in immunoprecipitations performed in RIPA buffer. Since the SUMO-1 conjugation of proteins is readily hydrolyzed under nondenaturing conditions, NEM, a potent inhibitor of deubiquitinating enzymes, which also inhibits SUMO-1 hydrolase activity (46), was added to immunoprecipitations. Cell lysates from U373 cells transfected with an IE72 expression vector were immunoprecipitated in the presence or absence of 20 μM NEM with a polyclonal antibody to IE72 (pAb543). Western blotting of these IE72 immunoprecipitates with a monoclonal antibody against IE72 detected a protein that comigrated with the ∼92-kDa IE72 protein in the presence of NEM that was not detected in the absence of NEM (Fig. 2). In the presence of NEM, the faster migrating species of IE72 migrates as a doublet. Thus, a specific SUMO-1 hydrolase inhibitor protected the highly labile form of IE72, suggesting that the higher-molecular-mass species may be sumoylated.

FIG. 2.

Addition of NEM to immunoprecipitation reaction mixtures allows detection of the ∼92-kDa form of IE72. Cell lysates from U373 cells transfected with pPSG-IE72 were immunoprecipitated with an anti-IE72 polyclonal antibody in the presence or absence of NEM, a specific SUMO-1 hydrolase inhibitor. Western blotting with anti-IE72 (monoclonal antibody) revealed the presence of the ∼92-kDa protein only in the lysates treated with NEM.

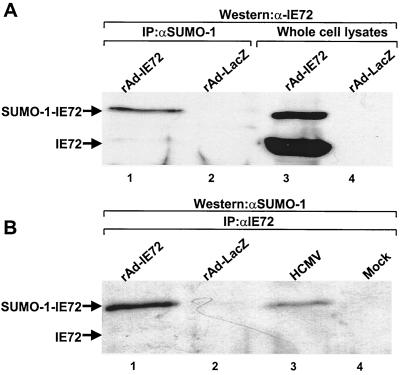

Detection of the ∼92-kDa form of IE72 by an antibody directed against SUMO-1.

U373 cells were infected with a recombinant adenovirus expressing either β-galactosidase or IE72. Cells were harvested in 50 mM Tris (pH 6.8)-2% SDS-10% glycerol, boiled for 10 min, and diluted 1:8 in PBS containing NEM, followed by addition of anti-SUMO-1 antibody (Fig. 3A) or anti-IE72 (pAb543) (Fig. 3B); immunoprecipitates were subjected to Western blot analysis using the reciprocal antibody, anti-IE72 (BS500) (Fig. 3A) or anti-SUMO-1 (Fig. 3B). The ∼92-kDa protein immunoprecipitated by anti-SUMO-1 cross-reacted with anti-IE72 (Fig. 3A), and that immunoprecipitated by anti-IE72 cross-reacted with anti-SUMO-1 (Fig. 3B). The reciprocal immunoprecipitations of the 92-kDa species with anti-SUMO-1 and anti-IE72 provide strong evidence for the 92-kDa species of IE72 resulting from its SUMO-1 modification.

FIG. 3.

Reciprocal coimmunoprecipitation of SUMO-1 and IE72. (A) U373 cells were infected with a recombinant adenovirus expressing either β-galactosidase (lanes 2 and 4) or IE72 (lanes 1 and 3). Untreated lysates (lanes 3 and 4) or lysates immunoprecipitated with anti-SUMO-1 antibody in the presence of NEM (lanes 1 and 2) were resolved by SDS-PAGE (lanes 3 and 4) and subjected to Western blot analysis using an antibody against IE72. (B) U373 cells were infected with rAd-IE72 (lane 1) or rAd-LacZ (lane 2). Forty-eight hours after infection, cells were harvested in 2% SDS buffer, boiled for 10 min, and diluted in PBS containing NEM to allow anti-IE72 immunoprecipitation of IE72. Western blot analysis of the precipitates was performed with anti-SUMO-1 antibody. For lanes 3 and 4, HFF were either HCMV infected (lane 3) or mock treated (lane 4). Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer supplemented with NEM. Immunoprecipitations were performed with an antibody against IE72, and an anti-SUMO-1 antibody was used for the Western blotting. IP, immunoprecipitation.

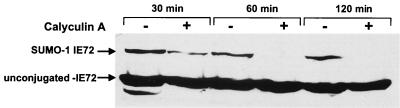

Relationship between SUMO-1 conjugation and phosphorylation of IE72.

Phosphorylation of PML, c-jun, and p53 appears to negatively regulate their SUMO-1 modification (13, 31, 34). Calyculin A (a potent inhibitor of serine/threonine phosphatases 1 and 2A) was used in the studies above to investigate the involvement of phosphorylation in sumoylation; therefore, we treated U373 cells stably expressing IE72 with either 0.1 μM calyculin A dissolved in DMSO or an equal volume of DMSO. Cells were lysed by being boiled in SDS sample buffer, and the extracts were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-IE72 for the presence of SUMO-modified IE72. Treatment of cells with calyculin A for as little as 30 min significantly decreased the amount of sumoylated IE72, and treatment for 1 h led to complete loss of sumoylated IE72, without affecting the levels of unconjugated IE72 (Fig. 4). These data suggest that serine/threonine phosphorylation of IE72 may negatively regulate its modification by SUMO-1. We are currently identifying the phosphoamino acid(s) involved in the regulation of IE72 sumoylation.

FIG. 4.

IE72 sumoylation is negatively regulated by its phosphorylation. U373 cells stably expressing IE72 were treated with either DMSO or 0.1 μM calyculin A (a phosphatase inhibitor) dissolved in DMSO. At the indicated time points, cells were harvested by direct lysis and boiling in SDS sample buffer. An antibody directed against IE72 was used for Western blotting.

Identification of the site of SUMO-1 modification in IE72.

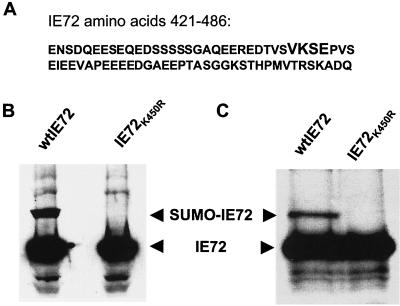

Having determined that IE72 is SUMO-1 modified, we sought to identify the region of IE72 involved in this modification. Lysates of cells transiently transfected with either wild-type IE72 or various C-terminal truncation mutants of IE72 were analyzed by anti-IE72 Western blotting. While a SUMO-modified form was clearly evident with wild-type IE72, no evidence of SUMO-1 modification could be detected on a mutant with the C terminus deleted (IE72Δ420-486) (data not shown). Analysis of the amino acids within this C-terminal region revealed a consensus sequence for sumoylation, 449(I/L/V)KXE452 (Fig. 5A). We constructed an IE72 point mutant in which lysine 450 was replaced with arginine (IE72K450R). U373 cells were transfected with pSG-IE72 or pSG-IE72K450R. Cell lysates were subjected to anti-IE72 Western blotting (Fig. 5B), and the 92-kDa band observed with wild-type IE72 was not seen with the point mutant. In a similar experiment, cells were labeled with [35S]methionine, followed by immunoprecipitation with anti-IE72, SDS-PAGE, and autoradiography. The 92-kDa radiolabeled band is seen only in the cells transfected with wild-type IE72 and not in those transfected with the K450R mutant (Fig. 5C). Thus, IE72K450R is deficient in SUMO-1 modification.

FIG. 5.

IE72 lysine 450 is SUMO-1 conjugated. (A) The C terminus of IE72 contains a sumoylation consensus motif, (V/I/L)KXE, implicating lysine 450 as the SUMO-1-conjugated residue. (B and C) A point mutation was made by replacing lysine 450 with arginine (IE72K450R). (B) U373 cells were transfected with pPSG-IE72 or pPSG-IE72K450R. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-IE72, followed by Western blotting with anti-IE72 in the presence of NEM and detection with a chemiluminescence reagent. (C) Cells were metabolically labeled by addition of [35S]methionine to the medium for 2 h, followed by immunoprecipitation of IE72 in the presence of NEM, SDS-PAGE, and autoradiography. wt, wild type.

Characterization of the role of SUMO modification of IE72.

Having determined that IE72 is SUMO-1 modified and having identified the lysine residue involved in this conjugation process, we proceeded to address the functional implications of this posttranslational modification.

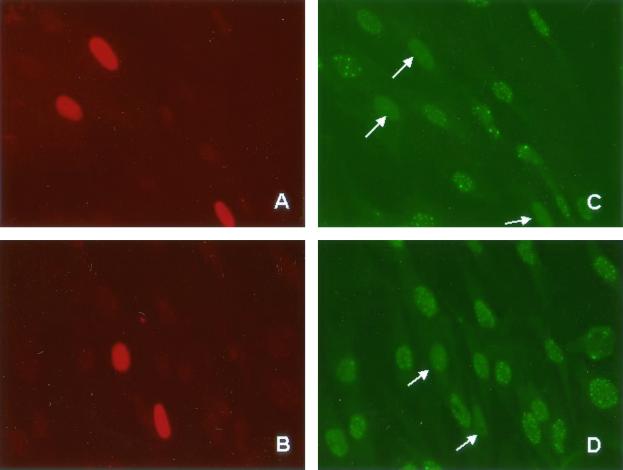

SUMO-1 modification of PML has been reported elsewhere to be involved in its targeting to PODs (12, 23, 34, 44). Since HCMV IE72 is localized in and disrupts PODs (2, 50), we tested the hypothesis that SUMO-1 conjugation of IE72 was responsible for POD localization and thereby for POD disruption. U373 cells grown on coverslips were transfected with either wild-type IE72 or IE72K450R and double immunostained for PML and IE72. We observed no differences between the POD localization or POD disruption in the sumoylation-deficient IE72 and that in the wild-type IE72 (Fig. 6). Therefore, we conclude that SUMO-1 is not responsible for the ability of IE72 to target and subsequently disrupt PODs.

FIG. 6.

The SUMO-1 modification of IE72 is not involved in POD targeting or disruption. HFF were transfected with either pPSG-IE72 or pPSG-IE72K450R. At 48 h posttransfection, cells were fixed and coimmunostained with anti-IE72 and anti-PML antibodies. Secondary antibodies were tagged with rhodamine (A and B) and fluorescein isothiocyanate (C and D). In cells that do not express IE72, PML is localized within subnuclear structures referred to as PODs (C and D). In cells not expressing IE72 (A and B, unstained cells), PODs are clearly seen as nuclear dots of about 20 to 30 per cell (C and D), whereas cells transfected with IE72 exhibit POD disruption (C, arrows). Cells expressing IE72K450R (B, stained cells) exhibit POD disruption (D, arrows) equivalent to that seen with wild-type IE72. Careful examination of the immunostaining reveals PML localization in nucleoli in untransfected and transfected cells whereas IE72 is excluded from these structures.

The DHFR promoter is activated by IE72 through the E2F sites (47). Transactivation assays were performed with U373 cells that were transfected with constructs containing the luciferase reporter gene under the control of the wild-type DHFR promoter or that with the E2F site mutated. As reported previously, IE72 activates the DHFR promoter approximately 20-fold, and mutation of the E2F sites reduces the activation by about 5-fold. No significant difference in transactivation of DHFR promoters was observed between IE72K450R and wild-type IE72 (data not shown).

SUMO modification reportedly affects protein stability. U373 cells were pSG-IE72 or pSG-IE72K450R. No significant difference was observed between the half-life of IE72K450R and that of wild-type IE72 (data not shown).

IE72-deficient HCMV (CR208) was used to test the significance of IE72 conjugation to SUMO-1 as it relates to HCMV replication. HFF were transduced with a retrovirus empty vector (LXSG) or a retrovirus that expresses wild-type IE72 or IE72K450R. These cells were then used to test the ability of the expressed protein to complement the IE72-deficient virus. Cells were infected with HCMV lacking IE72 (CR208) by using a 1:103 dilution of a 1.6 × 105-PFU/ml viral stock and overlaid with 0.6% low-melting-point agarose. Plaques were counted 9 days post-HCMV infection. The number of plaques obtained with IE72K450R was not significantly different from that with wild-type IE72. Thus, IE72 that cannot be SUMO-1 modified is not impaired in its ability to complement infection by IE72-deficient virus, suggesting that SUMO-1 modification of IE72 may not be essential for HCMV replication.

DISCUSSION

IE72 has two major forms of differing molecular masses on SDS-PAGE. The slower-migrating form migrates at an apparent molecular mass of approximately 92 kDa. The increase in apparent molecular mass is approximately 20 kDa, a size consistent with a single SUMO-1 conjugation. The amount of the 92-kDa protein is increased in the presence of NEM, a SUMO-1 hydrolase inhibitor. This 92-kDa form of IE72 was immunoprecipitated with antibodies directed against either IE72 or SUMO-1. There is a sumoylation consensus sequence in the C terminus of IE72, (I/V/L)KXE, where K represents lysine 450. A mutated protein in which lysine 450 was replaced with arginine was incapable of being SUMO-1 modified.

One of our initial hypotheses to explain the role of SUMO conjugation of IE72 was that SUMO-1 served as a POD targeting signal for IE72. This idea was based on the association of IE72 with PODs (2, 50) and the reports that SUMO-1 conjugation to PML (the major nuclear POD structural protein), served as a POD targeting signal (34). However, we found that the SUMO-1-deficient IE72 and wild-type IE72 had equal abilities to target and disrupt PODs (Fig. 6). More recent data demonstrate that SUMO-1-conjugation to PML may not be required for PML translocation to the PODs; however, it is necessary for the recruitment of other POD-associated proteins and for the maintenance of POD integrity (21).

Our studies have shown that IE72 is phosphorylated at distinct sites in its C-terminal region through autophosphorylation and also through phosphorylation by a cellular kinase (36; Himmelheber and Azizkhan-Clifford, unpublished data). Our data showing that inhibition of Ser/Thr protein phosphatases by calyculin A results in a decrease in the SUMO-1-modified form of IE72 suggest that phosphorylation may inhibit SUMO-1 conjugation. The sumoylation site is adjacent to the region of autophosphorylation, and we are presently analyzing the role of phosphorylation at specific sites in IE72 sumoylation. It is highly probable that the posttranslational modifications of phosphorylation and sumoylation play an important role in IE72 interaction with other gene regulatory proteins, because IE72 has been shown not to bind DNA directly, implicating protein-protein interactions in IE72 gene-regulatory function.

SUMO-1 modification of a protein can serve to stabilize it against proteosomal lysis through competition for a lysine residue that is used for both sumoylation and ubiquitination (e.g., IκBα) (10). While no significant difference was detected between the stability of IE72K450R and that of wild-type IE72, additional experiments are required for a comprehensive understanding of the role of phosphorylation and sumoylation in IE72 stability. Deletion of the C-terminal 80 amino acids from IE72, which removes the amino acids that are phosphorylated as well as lysine 450, decreases the stability of the protein in cells (S. Pajovic and J. Azizkhan-Clifford, unpublished data).

A review of the growing list of SUMO-1-modified or SUMO-1/Ubc9-interactive proteins suggests that SUMO-1 is important in numerous cellular processes (for reviews, see references 33 and 51) including apoptosis (p53, Mdm2, Daxx, IκBα, FAS/apolipoprotein-1, and TNFR1), viral oncogenesis (E1A, papillomavirus E1, and HCMV IE1 and IE2), transcription and cell cycle progression (ETS-1, TEL, CBP/p300, c-jun, glucocorticoid and androgen receptors, E2A, ATF2, p53, p73, HIPK2, MITF, and Wilms' tumor gene product), POD formation (PML and Sp100), centromere function (Cbf3 and MITF), nuclear import (RanGap1), and maintenance of genome integrity (topoisomerases, p53, and Wrn Rad 51 and 52). From this partial list of SUMO-interactive proteins, we can predict that SUMO-1 plays a role in transcription. The sumoylation motif is identical to a common motif within the negative regulatory regions of multiple factors (20). In accord with these data, sumoylation negatively regulates the transcription of c-jun and steroid receptors (31, 38), while others report that sumoylation increases the transactivation function of p53 and HCMV IE86 (19, 39). Using DHFR-luciferase, a promoter that is significantly transactivated by IE72 alone (25, 47), we found that sumoylation of IE72 does not significantly affect the transactivation of DHFR-luciferase compared to the wild type. The possible role of SUMO modification of IE72 in transactivation needs to be further explored.

The SUMO-1 yeast homologue was identified as a suppressor of mutations in Mif2 (mitotic instability factor 2), a protein thought to be the equivalent of the mammalian centromere protein CENP-C (28). Therefore, SUMO-1 may play a role in meiosis and/or mitosis control. We and others have found specific effects of IE72 on the cell cycle (27, 40). Since free SUMO-1 is limiting in the cell, SUMO-1 deconjugation is required to release SUMO-1 for additional protein modifications (10). SUMO-1 conjugation and deconjugation must be in balance for controlled cell growth (41). Thus, considering the abundance of IE72 in infected cells and the extent of its SUMO modification, sumoylation of IE72 could exert a global modulation of SUMO-1, which could regulate diverse genetic programs.

The SUMO-1 modification of IE72 may play a role in the precise temporal cascade of gene expression exhibited during HCMV infection. Considering the rapidly expanding list of proteins modified by SUMO-1, the contribution of sumoylated IE72 to HCMV replication may be complex. The observation that IE72K450R can complement CR208 suggests that sumoylation of IE72 is not essential for viral replication. At this time, we have not found an activity of IE72 that is compromised by lack of SUMO modification. However, our data are consistent with a possible negative regulatory role for SUMO modification of IE72. Further experimentation is required to determine the possible effects of sumoylation of IE72 in its various activities: modulation of gene expression, cell cycle control, and apoptosis.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Christopher Himmelheber and Andrew Ippolito for comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by NIH grant RO1-CA71019 to J.A.-C. and by U.S. Army DAMD17-00-1-0654 to M.L.S.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahn, J. H., and G. S. Hayward. 2000. Disruption of PML-associated nuclear bodies by IE1 correlates with efficient early stages of viral gene expression and DNA replication in human cytomegalovirus infection. Virology 274:39-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahn, J. H., and G. S. Hayward. 1997. The major immediate-early proteins IE1 and IE2 of human cytomegalovirus colocalize with and disrupt PML-associated nuclear bodies at very early times in infected permissive cells. J. Virol. 71:4599-4613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alford, C. A., and W. J. Britt. 1996. Cytomegalovirus, p. 2493-2534. In B. N. Fields, D. M. Knipe, and P. M. Howley (ed.), Fields virology, 3rd ed. Lippincott-Raven Publishers, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 4.Ausubel, L. J., C. K. Kwan, A. Sette, V. Kuchroo, and D. A. Hafler. 1996. Complementary mutations in an antigenic peptide allow for crossreactivity of autoreactive T-cell clones. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:15317-15322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bayer, P., A. Arndt, S. Metzger, R. Mahajan, F. Melchior, R. Jaenicke, and J. Becker. 1998. Structure determination of the small ubiquitin-related modifier SUMO-1. J. Mol. Biol. 280:275-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blake, M. C., and J. C. Azizkhan. 1989. Transcription factor E2F is required for efficient expression of the hamster dihydrofolate reductase gene in vitro and in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 9:4994-5002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang, K. S., S. A. Stass, D. T. Chu, L. L. Deaven, J. M. Trujillo, and E. J. Freireich. 1992. Characterization of a fusion cDNA (RARA/myl) transcribed from the t(15;17) translocation breakpoint in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12:800-810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dal Monte, P., M. P. Landini, J. Sinclair, J. L. Virelizier, and S. Michelson. 1997. TAR and Sp1-independent transactivation of HIV long terminal repeat by the Tat protein in the presence of human cytomegalovirus IE1/IE2. AIDS 11:297-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis, M. G., S. C. Kenney, J. Kamine, J. S. Pagano, and E. S. Huang. 1987. Immediate-early gene region of human cytomegalovirus trans-activates the promoter of human immunodeficiency virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:8642-8646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desterro, J. M., M. S. Rodriguez, and R. T. Hay. 1998. SUMO-1 modification of IκBα inhibits NF-κB activation. Mol. Cell 2:233-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de The, H., C. Lavau, A. Marchio, C. Chomienne, L. Degos, and A. Dejean. 1991. The PML-RAR alpha fusion mRNA generated by the t(15;17) translocation in acute promyelocytic leukemia encodes a functionally altered RAR. Cell 66:675-684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duprez, E., A. J. Saurin, J. M. Desterro, V. Lallemand-Breitenbach, K. Howe, M. N. Boddy, E. Solomon, H. de The, R. T. Hay, and P. S. Freemont. 1999. SUMO-1 modification of the acute promyelocytic leukaemia protein PML: implications for nuclear localisation. J. Cell Sci. 112:381-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Everett, R. D., P. Lomonte, T. Sternsdorf, R. van Driel, and A. Orr. 1999. Cell cycle regulation of PML modification and ND10 composition. J. Cell Sci. 112:4581-4588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goddard, A. D., J. Borrow, P. S. Freemont, and E. Solomon. 1991. Characterization of a zinc finger gene disrupted by the t(15;17) in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Science 254:1371-1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greaves, R. F., and E. S. Mocarski. 1998. Defective growth correlates with reduced accumulation of a viral DNA replication protein after low-multiplicity infection by a human cytomegalovirus ie1 mutant. J. Virol. 72:366-379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hagemeier, C., S. M. Walker, P. J. Sissons, and J. H. Sinclair. 1992. The 72K IE1 and 80K IE2 proteins of human cytomegalovirus independently trans-activate the c-fos, c-myc and hsp70 promoters via basal promoter elements. J. Gen. Virol. 73:2385-2393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayhurst, G. P., L. A. Bryant, R. C. Caswell, S. M. Walker, and J. H. Sinclair. 1995. CCAAT box-dependent activation of the TATA-less human DNA polymerase α promoter by the human cytomegalovirus 72-kilodalton major immediate-early protein. J. Virol. 69:182-188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hodges, M., C. Tissot, K. Howe, D. Grimwade, and P. S. Freemont. 1998. Structure, organization, and dynamics of promyelocytic leukemia protein nuclear bodies. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 63:297-304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hofmann, H., S. Floss, and T. Stamminger. 2000. Covalent modification of the transactivator protein IE2-p86 of human cytomegalovirus by conjugation to the ubiquitin-homologous proteins SUMO-1 and hSMT3b. J. Virol. 74:2510-2524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iniguez-Lluhi, J. A., and D. Pearce. 2000. A common motif within the negative regulatory regions of multiple factors inhibits their transcriptional synergy. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:6040-6050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ishov, A. M., A. G. Sotnikov, D. Negorev, O. V. Vladimirova, N. Neff, T. Kamitani, E. T. Yeh, J. F. Strauss III, and G. G. Maul. 1999. PML is critical for ND10 formation and recruits the PML-interacting protein daxx to this nuclear structure when modified by SUMO-1. J. Cell Biol. 147:221-234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kakizuka, A., W. H. Miller, Jr., K. Umesono, R. P. Warrell, Jr., S. R. Frankel, V. V. Murty, E. Dmitrovsky, and R. M. Evans. 1991. Chromosomal translocation t(15;17) in human acute promyelocytic leukemia fuses RAR alpha with a novel putative transcription factor, PML. Cell 66:663-674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kamitani, T., H. P. Nguyen, K. Kito, T. Fukuda-Kamitani, and E. T. Yeh. 1998. Covalent modification of PML by the sentrin family of ubiquitin-like proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 273:3117-3120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mahajan, R., C. Delphin, T. Guan, L. Gerace, and F. Melchior. 1997. A small ubiquitin-related polypeptide involved in targeting RanGAP1 to nuclear pore complex protein RanBP2. Cell 88:97-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Margolis, M. J., S. Pajovic, E. L. Wong, M. Wade, R. Jupp, J. A. Nelson, and J. C. Azizkhan. 1995. Interaction of the 72-kilodalton human cytomegalovirus IE1 gene product with E2F1 coincides with E2F-dependent activation of dihydrofolate reductase transcription. J. Virol. 69:7759-7767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maul, G. G. 1998. Nuclear domain 10, the site of DNA virus transcription and replication. Bioessays 20:660-667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McElroy, A. K., R. S. Dwarakanath, and D. H. Spector. 2000. Dysregulation of cyclin E gene expression in human cytomegalovirus-infected cells requires viral early gene expression and is associated with changes in the Rb-related protein p130. J. Virol. 74:4192-4206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meluh, P. B., and D. Koshland. 1995. Evidence that the MIF2 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae encodes a centromere protein, CENP-C. Mol. Biol. Cell 6:793-807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller, A. D., D. G. Miller, J. V. Garcia, and C. M. Lynch. 1993. Use of retroviral vectors for gene transfer and expression. Methods Enzymol. 217:581-599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mocarski, E. S., G. W. Kemble, J. M. Lyle, and R. F. Greaves. 1996. A deletion mutant in the human cytomegalovirus gene encoding IE1(491aa) is replication defective due to a failure in autoregulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:11321-11326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muller, S., M. Berger, F. Lehembre, J. S. Seeler, Y. Haupt, and A. Dejean. 2000. c-Jun and p53 activity is modulated by SUMO-1 modification. J. Biol. Chem. 275:13321-13329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muller, S., and A. Dejean. 1999. Viral immediate-early proteins abrogate the modification by SUMO-1 of PML and Sp100 proteins, correlating with nuclear body disruption. J. Virol. 73:5137-5143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muller, S., C. Hoege, G. Pyrowolakis, and S. Jentsch. 2001. SUMO, ubiquitin's mysterious cousin. Nat. Rev. 2:202-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muller, S., M. J. Matunis, and A. Dejean. 1998. Conjugation with the ubiquitin-related modifier SUMO-1 regulates the partitioning of PML within the nucleus. EMBO J. 17:61-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nelson, J. A., C. Reynolds-Kohler, M. B. Oldstone, and C. A. Wiley. 1988. HIV and HCMV coinfect brain cells in patients with AIDS. Virology 165:286-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pajovic, S., E. L. Wong, A. R. Black, and J. C. Azizkhan. 1997. Identification of a viral kinase that phosphorylates specific E2Fs and pocket proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:6459-6464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pizzorno, M. C., M. A. Mullen, Y. N. Chang, and G. S. Hayward. 1991. The functionally active IE2 immediate-early regulatory protein of human cytomegalovirus is an 80-kilodalton polypeptide that contains two distinct activator domains and a duplicated nuclear localization signal. J. Virol. 65:3839-3852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Poukka, H., U. Karvonen, O. A. Janne, and J. J. Palvimo. 2000. Covalent modification of the androgen receptor by small ubiquitin-like modifier 1 (SUMO-1). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:14145-14150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rodriguez, M. S., J. M. Desterro, S. Lain, C. A. Midgley, D. P. Lane, and R. T. Hay. 1999. SUMO-1 modification activates the transcriptional response of p53. EMBO J. 18:6455-6461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Salvant, B. S., E. A. Fortunato, and D. H. Spector. 1998. Cell cycle dysregulation by human cytomegalovirus: influence of the cell cycle phase at the time of infection and effects on cyclin transcription. J. Virol. 72:3729-3741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schwienhorst, I., E. S. Johnson, and R. J. Dohmen. 2000. SUMO conjugation and deconjugation. Mol. Gen. Genet. 263:771-786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stenberg, R. M., A. S. Depto, J. Fortney, and J. A. Nelson. 1989. Regulated expression of early and late RNAs and proteins from the human cytomegalovirus immediate-early gene region. J. Virol. 63:2699-2708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stenberg, R. M., and M. F. Stinski. 1985. Autoregulation of the human cytomegalovirus major immediate-early gene. J. Virol. 56:676-682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sternsdorf, T., K. Jensen, and H. Will. 1997. Evidence for covalent modification of the nuclear dot-associated proteins PML and Sp100 by PIC1/SUMO-1. J. Cell Biol. 139:1621-1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stuurman, N., A. de Graaf, A. Floore, A. Josso, B. Humbel, L. de Jong, and R. van Driel. 1992. A monoclonal antibody recognizing nuclear matrix-associated nuclear bodies. J. Cell Sci. 101:773-784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Suzuki, T., A. Ichiyama, H. Saitoh, T. Kawakami, M. Omata, C. H. Chung, M. Kimura, N. Shimbara, and K. Tanaka. 1999. A new 30-kDa ubiquitin-related SUMO-1 hydrolase from bovine brain. J. Biol. Chem. 274:31131-31134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wade, M., T. F. Kowalik, M. Mudryj, E.-S. Huang, and J. C. Azizkhan. 1992. E2F mediates dihydrofolate reductase promoter activation and multiprotein complex formation in human cytomegalovirus infection. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12:4364-4374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Walker, S., C. Hagemeier, J. G. Sissons, and J. H. Sinclair. 1992. A 10-base-pair element of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 long terminal repeat (LTR) is an absolute requirement for transactivation by the human cytomegalovirus 72-kilodalton IE1 protein but can be compensated for by other LTR regions in transactivation by the 80-kilodalton IE2 protein. J. Virol. 66:1543-1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wilkinson, G. W., and A. Akrigg. 1992. Constitutive and enhanced expression from the CMV major IE promoter in a defective adenovirus vector. Nucleic Acids Res. 20:2233-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wilkinson, G. W., C. Kelly, J. H. Sinclair, and C. Rickards. 1998. Disruption of PML-associated nuclear bodies mediated by the human cytomegalovirus major immediate early gene product. J. Gen. Virol. 79:1233-1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yeh, E. T., L. Gong, and T. Kamitani. 2000. Ubiquitin-like proteins: new wines in new bottles. Gene 248:1-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhu, H., Y. Shen, and T. Shenk. 1995. Human cytomegalovirus IE1 and IE2 proteins block apoptosis. J. Virol. 69:7960-7970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]