Abstract

To study the involvement of immune responses against Tax of human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1) in the growth of and gene suppression in Tax-expressing tumor cells in vivo, we established a model system involving C57BL/6J mice and a syngeneic lymphoma cell line, EL4. When mice were immunized by DNA-based immunization with Tax expression plasmids, solid tumor formation upon subcutaneous inoculation of EL4 cells expressing green fluorescent protein-fused Tax (Gax) under the control of the HTLV-1 enhancer was strongly inhibited, and in vitro analysis showed that DNA immunization elicited cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) responses but not production of antibodies to Tax protein. Since EL4/Gax cells inoculated into DNA-immunized mice were not completely eradicated but were maintained as small solid tumors for a long period, there appeared to be a certain equilibrium between CTL activity and the growth of Gax-expressing cells. With such a balance, expression of the Gax gene in EL4/Gax cells was strongly suppressed. These results suggested that gene expression under the control of the HTLV-1 long terminal repeat and Tax is silenced in vivo, resulting in an equilibrium between viral expression and the host immune system. Such a balance would represent a status of persistent infection by HTLV-1 in virus-infected individuals during the latency period.

Human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1) is the etiologic agent for adult T-cell leukemia (ATL) (23, 34) and for a neuropathic disease, tropical spastic paraparesis/HTLV-1-associated myelopathy (HAM/TSP) (3; M. Osame, M., K. Usuku, S. Izumo, N. Ijichi, H. Amitani, A. Igata, M. Matsumoto, and M. Tara, Letter, Lancet i:1031-1032, 1986). HTLV-1 infects 10 to 20 million people worldwide; of whom 1 to 2% develop HAM/TSP and a further 2 to 3% develop ATL. The 40-kDa viral transactivator protein Tax triggers viral transcription (4, 6, 7, 25, 26) as well as induction of cellular genes including those for interleukin-2 (IL-2) and the IL-2 receptor (2, 11, 18), and the function of Tax is essential for HTLV-1 transformation of human T lymphocytes (5).

In addition, Tax protein plays a role as an immunodominant target antigen recognized by HTLV-1 specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) in most HTLV-1-infected individuals (14, 22). In HAM/TSP patients, a high virus load in peripheral blood lymphocytes is observed and a Tax-specific CTL response occurs at a high frequency (14), while low CTL activity has been reported for ATL patients (15). Therefore, a balance between Tax expression and Tax-specific CTL responses is thought to be an important determinant of the development of HTLV-1-related diseases (31). There has been controversy over whether Tax-specific CTL causes or prevents HTLV-1-related diseases, or whether a high viral load in the blood in HAM/TSP patients is a result or a cause of CTL. Recently, it was reported that there is a significant negative correlation between the frequency of Tax-specific CTL and the percentage of HTLV-1-infected CD4+ T cells in the peripheral blood of HAM/TSP patients (10). These results seem to be in accord with the view that Tax-specific CTL protect against disease progression.

Furthermore, there remains another unanswered question as to the long latency before the onset of HTLV-1-related diseases. It has been suggested that the latent period involves mutations in the genomes of infected lymphocytes, some part of which have been attributed to the function of Tax protein (13, 32), and selection by the host immune system. In fact, it was demonstrated recently that the HTLV-1 tax gene in most leukemic cells from ATL patients accumulated various types of mutations leading to viral escape from the host immune system (9). For analysis of events in such a latent period, it is necessary to establish an animal model in which the growth of HTLV-1-infected lymphocytes and the host immune system reach a certain balance in vivo. Since HTLV-1 cannot replicate well in mouse cells, a certain strain of rat (17) and SCID mice (27) only have been used as animal models of HTLV-1-related diseases. Mice, however, have a great advantages as model animals, and normal immune reactivity is required to investigate the onset of HTLV-1-related diseases.

To gain insights into the mechanisms underlying the long latency and onset of HTLV-1-related diseases, we established a simple animal model for investigating the interaction between Tax-expressing cells and Tax-specific immune responses involving mice and syngeneic T lymphoma cells expressing Tax. Focusing on Tax and anti-Tax immune responses, we demonstrated that Tax expression under the control of the HTLV-1 long terminal repeat (LTR) was transiently suppressed in vivo, resulting in a kind of equilibrium between Tax-specific immune responses and the growth of tumor cells exhibiting very low Tax expression. Expression of Tax in vivo resumed quickly when the cells were transferred to in vitro conditions. Since this situation greatly resembles virus expression in HTLV-1-infected T lymphocytes derived from ATL or HAM/TSP patients, the mouse system that we established here will be a valuable model for analyzing the suppression mechanism for the proviral genome in vivo and the involvement of the host immune system in maintaining the long latency before the onset of HTLV-1-related diseases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid construction.

To establish a mouse lymphoma cell line which expresses HTLV-1 Tax under the control of the HTLV-1 LTR, we used a murine leukemia virus (MLV)-HTLV-1 chimeric retrovirus vector. The parental MLV vector pRx (30) comprises a cytomegalovirus enhancer/promoter unit at the 5′ end, a multicloning site (MCS) linked with a drug resistance gene, bsr, through an internal ribosomal entry site (IRES), and an MLV LTR at the 3′ end. The cDNA of Tax was inserted at the BamHI site in the MCS, resulting in Tax expression retrovirus vector pRTaxbsr. To replace the U3 region of the MLV LTR with that of HTLV-1, a 273-bp NheI-XbaI fragment of the U3 region of the MLV LTR was replaced with a 266-bp SmaI-NdeI fragment of U3 of the HTLV-1 LTR. The resultant vector was designated pR3Taxbsr. To obtain enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)-fused Tax DNA, an NcoI-PstI (757-bp) EGFP fragment of pEGFP-C1 (Clontech, Palo Alto, Calif.) was inserted into the 5′ end of the Tax coding region in frame (we refer to EGFP-fused Tax as Gax below). We also constructed an EGFP-expressing retrovirus vector (pREGFP) encoding EGFP cDNA in the MCS of pRx. Expression vector pCG-BL (8) was used for vaccine construction. The wild-type and mutant tax cDNAs were inserted into pCG-BL, resulting in pCG-Tax, pCG-d17/5, and pCG-Gax. In the d17/5 Tax mutant, the sequence Pro113-Tyr114 was changed to Gln-Asp-Cys, and thus the function of Tax as a transcriptional activator was completely abolished (28). To confirm the transcriptional activity of mutant Tax(s), we constructed a reporter plasmid, pLTR-Luc, by inserting a 647-bp HTLV-1 LTR fragment (33) into the MCS site of the pGL3 vector (Promega, Madison, Wis.). As adjuvants for DNA immunization, the granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) expression vector (obtained from Hirofumi Hamada, Sapporo Medical College) and a CpG oligonucleotide were used in some experiments. The sequence of the CpG oligonucleotide was as follows: 5′-TCCATGACGTTCCTGACGTT-3′. All plasmid DNAs were purified by using an Endfree Plasmid Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany).

Cell lines.

All cells used except EL4 and its derivatives were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and antibiotics. Carcinogen-induced lymphoma EL4 cells of C57BL/6 (H-2b) origin were grown in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and antibiotics. The mouse cell lines NIH 3T3 and EL4 and the human cell lines HeLa and 293T were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection. BOSC23 packaging cells (21) were also obtained from the American Type Culture Collection.

Retrovirus vectors.

To produce a retrovirus vector, 3 μg of pRTaxbsr, pR3Taxbsr, or pR3Gaxbsr was transfected with 5 × 105 BOSC23 packaging cells by using Lipofectamine (GIBCO BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.). At 50 h posttransfection, the culture supernatants were collected in 15-ml tubes and centrifuged at 600 × g at 4°C for 10 min to remove the cells. Aliquots of the clarified supernatants were stored at −80°C until use. To determine the virus titers, 100 μl of the culture supernatant of each vector was infected with 105 NIH 3T3 cells in the presence of 8 μg of Polybrene/ml. Two days postinfection, 5 μg of Blasticidin S (Funakoshi, Tokyo, Japan)/ml was added with fresh growth medium. After 7 days of selection, colonies formed by surviving cells were counted and the titer of each virus vector was calculated. To compare the expression levels of Tax in the infected cells, 105 NIH 3T3 cells were infected with the same titer of RTaxbsr and R3Taxbsr virus, and then the cells were collected for Western blotting.

Tax mutants.

To confirm the expression of mutant Tax, d17/5, and Gax, 1.5 μg of each pCG plasmid was transfected into 105 293T cells with Lipofectamine. Two days after transfection, cells were collected for Western blotting. For the functional assay, 1.5 μg of each pCG plasmid and 0.5 μg of pLTR-Luc were cotransfected into 105 HeLa or 293T cells. Two days after transfection, the luciferase activity of each cell lysate was measured by using the Luciferase Assay System (Promega).

Protein analysis.

For Western blotting, transfected or infected cells were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-Cl, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.05% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 20 μM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 4 μg of aprotinin and leupeptin/ml). To extract proteins from a solid tumor, the tumor was cut into small pieces in liquid nitrogen and then homogenized in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer on ice. Cell lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C, and the concentrations of proteins were measured with bicinchoninic acid protein assay reagents (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.). The same amount of each protein was analyzed by SDS-12% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), blotted onto a PVDF membrane (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.), and then probed with a rabbit antiserum against the C terminus of Tax and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated protein A. Detection of a protein was performed by means of ECL (Amersham Pharmacia, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom). To distinguish live cells from dead ones, cells were first incubated with propidium iodide (PI; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) for 10 min at room temperature and then subjected to flow cytometry with a FACscan (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, Calif.). Data were analyzed with CELLQuest software (Becton Dickinson).

Establishment of a Tax-expressing lymphoma cell line.

A 0.1-ml volume of either R3Gaxbsr, RTaxbsr, or REGFP virus was inoculated with 2 × 106 EL4 cells into 0.9 ml of culture medium containing 0.8 μg of Polybrene (Sigma)/ml followed by culturing for 4 h. After a wash with RPMI 1640, the cells were suspended in 10 ml of growth medium. Two days postinfection, 20 μg of Blasticidin S (Funakoshi)/ml was added to select cells. Two weeks after selection, the mixture of surviving cells was diluted and seeded into the wells of microtiter well plates to obtain single-cell clones. Expression of Gax or EGFP protein was assessed as the intensity of EGFP fluorescence under a fluorescent microscope, and a cell clone exhibiting high-level expression of Gax was further selected by higher intensity of GFP with a FACstar (Becton Dickinson). The cell lines transduced with either R3Gaxbsr, RTaxbsr, or REGFP virus were named EL4/Gax, EL4/Tax, or EL4/EGFP, respectively.

Immunization protocol.

Six-week-old female C57BL/6J (H-2b) mice were purchased from CREA Japan Inc. and maintained under standard pathogen-free conditions in the animal facility of Kansai Medical University. Vaccination was performed five times weekly by intramuscular (i.m.) injection of 50 μg of pCG DNA in 100 μl of 0.9% NaCl into a hind thigh, with the animal under anesthesia. In some experiments, we also used 10 μg of adjuvant DNA(s). For the protection assay, immunized mice were then subcutaneously (s.c.) injected with 5 × 105 EL4/Gax or EL4 cells as a control. To analyze the protein expression of EL4/Gax cells in vivo, 104 EL4/Gax cells were intraperitoneally (i.p.) injected into immunized mice. Control mice were not immunized but were i.p. injected with 102 EL4 cells. For cell-immunization, 105 EL4, EL4/Tax, or EL4/EGFP cells in 100 μl of saline were injected s.c. 2 weeks before i.p. challenge.

CTL assay.

To prepare antigen-presenting cells (APCs), splenocytes of C57BL/6J mice were plated onto a dish and then cultured for 2 h at 37°C. After removal of floating cells by extensive washing with RPMI 1640, adherent cells were transfected with pCG-Tax with Lipofectamine. One day after transfection, CD5+ T cells were purified from the splenocytes of immunized mice on a MACS column (Miltenyi Biotec, Gladbach, Germany), and cocultivation was started with the APCs. After 3 days, CTL activity against EL4/Gax cells was determined by a 5-h 51Cr release assay.

RT-PCR.

A solid tumor in a sacrificed mouse was cut into small pieces and homogenized in Trisol (GIBCO BRL). The RNA extraction procedure followed the commercial instructions. Fifty micrograms of purified RNA was treated with 2 U of RNase-free DNase I (GIBCO BRL) at 37°C for 15 min, followed by phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. Two micrograms of RNA was subjected to reverse transcription (RT) using RivaTra Ace (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan) with oligo(dT)20-40 (Amersham Pharmacia) as a primer. All PCRs were performed in 50-μl reaction mixtures comprising 5 μl of the 50-times-diluted RT product, 1.25 U of Ex Taq polymerase and its buffer (Takara, Kyoto, Japan), 200 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, and a primer set at 250 μM. The cycling conditions for all amplifications were 94°C for 5 min; 30 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 2 min, and 72°C for 1 min; and a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. The sequences of the primers for detection of Gax and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (G3PDH) were as follows: 5′-CGGATACCCAGTCTACGTGT-3′ and 5′-GAGCCGATAACGCGTCCATCG-3′ for the Gax gene and 5′-ACCACAGTCCATGCCATCAC-3′ and 5′-TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTA-3′ for the G3PDH gene as an internal control. A 10-μl volume of PCR products was analyzed by 1.5% agarose electrophoresis. As a positive control, 50 fg of the pR3Gaxbsr plasmid was used as a template in one reaction.

RESULTS

Construction of a Tax-expressing EL4 cell line.

To establish an animal model for studying the interaction between Tax-expressing tumor cells and the host immune system, the lymphoma cell line EL4 was infected with a Tax-encoding recombinant retrovirus, and then the growth of the infected cells in syngeneic C57BL/6J mice and the gene expression in these cells were analyzed.

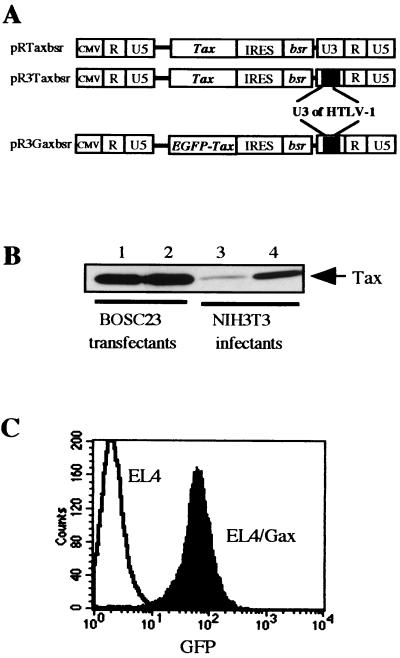

The Tax-encoding retrovirus vector, pR3Taxbsr, was constructed from an MLV-based retrovirus vector, pRTaxbsr, by exchanging the U3 region of the 3′ LTR with that of HTLV-1 (Fig. 1A). At the end of the recombinant retrovirus infection cycle, the HTLV-1 U3 sequence located in the 3′ LTR of the pR3Taxbsr vector plasmid was copied to the 5′ LTR of the proviral genome in infected cells and functioned as a Tax-dependent enhancer of transcription. Both retroviral vector plasmids, pRTaxbsr and pR3Taxbsr, were transfected into an ecotropic-packaging cell line, BOSC23, and recombinant viruses were recovered in the culture medium at 50 h posttransfection. Similar levels of Tax protein expression was observed in the packaging cells with the two vector plasmids (Fig. 1B, lanes 1 and 2). Tax-dependent transcriptional activation was confirmed in NIH 3T3 cells that had been infected with a similar titer of either recombinant retrovirus (Fig. 1B, lanes 3 and 4). About 100 drug-resistant cell clones were pooled, and Tax expression in these cells was analyzed by immunoblotting of the total-cell lysate. As shown in Fig. 1B, changing of the U3 region from that of MLV to that of HTLV-1 resulted in great enhancement of Tax expression in infected cells, indicating that the integrated proviral genome was activated by Tax protein, as was observed in HTLV-1-infected cells.

FIG. 1.

(A) Design of retrovirus vectors. The parental vector, pRTaxbsr, has a cytomegalovirus enhancer/promoter unit (CMV p) at the 5′ end, cDNA of Tax linked with a drug resistance gene, bsr, by an IRES, and an MLV LTR at the 3′ end. The 273-bp U3 region of MLV LTR was replaced by a 266-bp fragment of HTLV-1 LTR, resulting in pR3Taxbsr. Then cDNA of EGFP was fused with tax cDNA at the 5′ end, resulting in pR3Gaxbsr. (B) The protein expression of the pR and pR3 vectors was compared by Western blotting using an anti-Tax rabbit antiserum. BOSC23 cells were transfected with either pRTaxbsr or pR3Taxbsr by using Lipofectamine. NIH 3T3 cells were infected with the same titer of a supernatant of transfected BOSC23 cells. Proteins were harvested 50 h posttransfection and 48 h postinfection. Three micrograms of transfected BOSC23 cell lysates (lanes 1 and 2) and 17 μg of infected NIH 3T3 cell lysates (lanes 3 and 4) were analyzed by SDS-12% PAGE, blotted onto PVDF membranes, and then probed with a rabbit antiserum against the C terminus of Tax. (C) Establishment a mouse lymphoma cell line expressing Gax. EL4 cells were infected with pR3Gaxbsr virus, selected with Blasticidin S, cloned by limiting dilution, and then sorted as to EGFP intensity. The Gax-expressing cell line was established and named EL4/Gax. We also established EL4/Tax and EL4/EGFP cell lines by infection with RTaxbsr and REGFP viruses, respectively (data not shown).

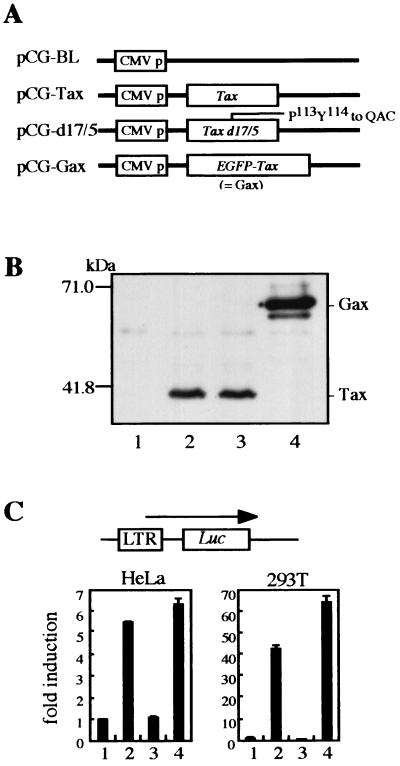

Then, to conveniently monitor Tax expression in vivo, pR3Taxbsr was further modified to encode Gax by fusing the EGFP gene to the 5′ end of the Tax-coding region, resulting in pR3Gaxbsr (Fig. 1A). The characteristics of Gax protein as a transactivator were shown to be retained in the luciferase assay by cotransfecting its expression vector with the HTLV-1 LTR Luc reporter plasmid into either HeLa or 293T cells (Fig. 2C).

FIG. 2.

DNA vaccine of HTLV-1 Tax and its mutant. (A) Schematic diagram of the expression vectors used for DNA immunization. The eukaryotic expression vector pCG-BL expresses no structural proteins. Wild-type and mutant tax cDNAs were inserted into pCG-BL, resulting in pCG-Tax, pCG-d17/5, and pCG-Gax. In pCG-d17/5, the 113Pro-114Tyr sequence was changed to Gln-Asp-Cys. (B) Protein expression from each vector in human kidney 293T cells. Cells were transfected with pCG-BL (lane 1), pCG-Tax (lane 2), pCG-d17/5 (lane 3), or pCG-Gax (lane 4), and then Western blot analysis was performed as described in the legend to Fig. 1. (C) Transactivation of the HTLV-1 LTR by Tax or Tax mutants. Either HeLa (left) or 293T (right) cells were cotransfected with pLTR-Luc, which is an HTLV-1 LTR reporter plasmid, and one of the pCG vectors by using Lipofectamine. Lanes correspond to those in panel B. Two days posttransfection, cells were lysed and luciferase activity was measured. Data shown are averages for three independent transfections.

EL4 cells were infected with R3Gaxbsr recombinant virus, and Gax-transduced cell-clones were selected by the limiting-dilution method in the presence of blasticidin S. Cloned cells were screened for GFP intensity, and from one of the clones expressing high levels of Gax, a cell population of higher intensity was further enriched by means of a fluorescence-activated cell sorter, resulting in EL4/Gax cells (Fig. 1C). We also established EL4-derived cell lines infected with either RTaxbsr or REGFP recombinant retrovirus, resulting in EL4/Tax or EL4/EGFP, respectively, as a control.

Effect of Tax DNA vaccine on EL4/Gax cells in vivo.

To analyze the interaction of the host immune system with Tax-expressing tumor cells, EL4/Gax cells were injected s.c. into syngeneic C57BL/6J mice. Injection of 5 × 105 EL4/Gax cells caused the formation of a solid tumor at the injection site; the maximum size was reached within 2 to 3 weeks, and the mice died of multiorgan metastasis in 4 to 10 weeks (data not shown). Since it has been demonstrated that Tax protein retains strong CTL epitope activity, we examined whether or not the CTL activity against Tax protein affected the growth of Tax-expressing EL4 cells.

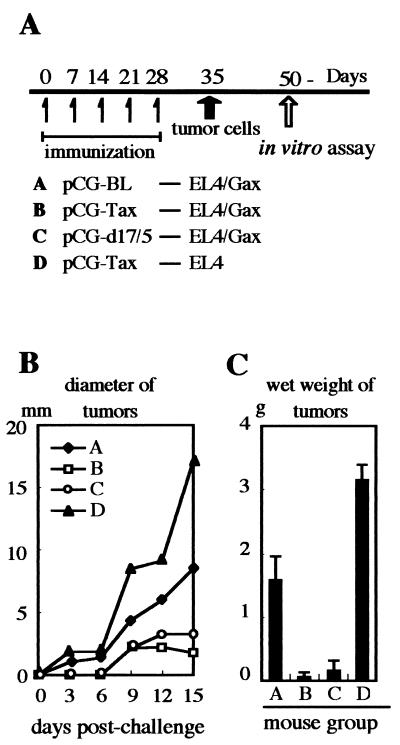

To induce CTL activity against Tax in mice, a DNA-mediated vaccine strategy was employed (Fig. 3A). Six-week-old female C57BL/6J mice were placed into four groups of five animals each and then immunized 5 times every week with 50 μg of an expression vector plasmid, pCG-Tax, or its derivatives by i.m. injection. To enhance immune responses, 10 μg of an expression vector for GM-CSF (1, 29) and 10 μg of a CpG oligonucleotide (16) were also injected. Mice in group A were immunized with the control vector, pCG-BL, which expresses no protein. Mice in groups B and D were immunized with the wild-type Tax expresser, pCG-Tax, and group C mice were immunized with the Tax null mutant expresser, pCG-d17/5 (a linker insertion mutant of the Tax gene with amino acid changes of P113 Y114 to QAC). On day 35 after the first immunization, mice were challenged s.c. in a hind thigh with 5 × 105 EL4/Gax cells (groups A, B, and C) or EL4 cells (group D). Fifteen days later, the mice were sacrificed, and the cellular and humoral immune responses were examined in vitro.

FIG. 3.

(A) Mice were placed in four groups, A to D, and immunized with 50 μg of pCG vector 5 times by i.m. injection. Mice in group A were immunized with pCG-BL. In groups B and D, mice were vaccinated with pCG-Tax, while mice in group D were challenged with control tumor cells, EL4, after immunization. Mice in group C were immunized with a vector expressing the Tax null mutant d17/5. All mice in groups B to D were also injected with 10 μg of a GM-CSF-expressing vector and a CpG oligonucleotide. Two weeks after five DNA injections, mice were challenged s.c. with 5 × 105 lymphoma cells. (B) The diameters of tumors at the injection sites were determined by using vernier calipers on the indicated days after challenge with EL4/Gax or EL4 cells. Data represent averages for five mice. (C) Wet weights of tumors taken from sacrificed mice 50 to 52 days postimmunization (about 2 weeks after tumor challenge) were determined. Mouse groups correspond to those in panel A.

On monitoring of the diameters of tumors with calipers every 3 days, we detected no visible solid tumors until day 6 postchallenge in mice immunized with either the wild type or the d17/5 tax gene (groups B and C, respectively), while solid tumors became visible in 3 days after challenge in control mice (groups A and D). Although, at 1 week after challenge, tumors were visible in immunized mice as well, the sizes of the tumors seemed to reach a plateau thereafter (Fig. 3B). On day 15 postchallenge, the average diameters of tumors in groups B and C were 42.3 and 23.5%, respectively, of that in the control mice in group A. DNA immunization with the wild type Tax gene afforded no protection against parental EL4 cells (group D), thus indicating that tumor growth was inhibited by Tax-specific immunity.

We also excised solid tumors from mice and determined the wet weight on the same day (Fig. 3C). The tumor weights in either Tax -or d17/5-immunized mice were significantly lower than those in control mice. Immunization with wild-type Tax DNA appeared not to inhibit the growth of parental EL4 cells.

In vivo protection assays showed no significant difference between vaccination with the wild-type Tax DNA and vaccination with the d17/5 mutant Tax DNA with regard to tumor protection. These data excluded the possibility that Tax expression in vivo might have an indirect effect on the host immune system by inducing cytokine production in DNA-transfected tissue cells, instead supporting the idea that some peptide epitope(s) on Tax protein is involved in the immune response to suppress the growth of EL4/Gax cells. Furthermore, the fact that direct injection of the expression plasmid for a null mutant of Tax protein successfully induced the protective immune response against Tax-expressing tumor cells suggests a possible practical application of the mutant gene.

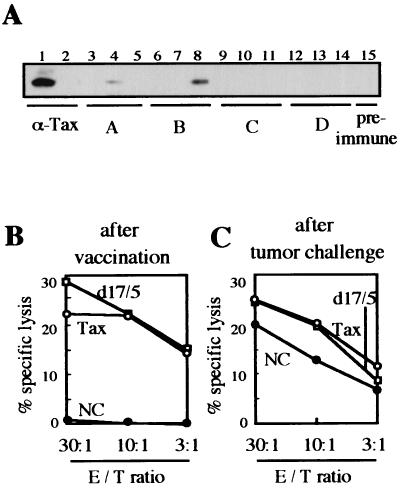

Cellular and humoral immunity with DNA vaccination.

To investigate immune responses induced by the DNA vaccine, we examined the antibody responses and CTL activities of the animals used in the experiment for which results are shown in Fig. 3. Sera of three mice in each group and one preimmune mouse were analyzed by immunoblotting (Fig. 4A). Two serum specimens from groups A and B showed positive signals (Fig. 4A, lanes 4 and 8). These responses were possibly due to the EL4/Gax challenge cells, because no antibody responses were observed just after DNA immunization (data not shown), and the positive signal detected in lane 4 was obtained for a group A mouse that had not been immunized with the Tax gene. Thus, we concluded that DNA vaccination with Tax DNA does not induce strong antibody production.

FIG. 4.

Humoral and cellular immune responses determined in vitro for DNA-immunized and EL4/Gax-challenged mice. (A) Sera were collected from three mice in each group and one preimmune mouse. 293T cells were transfected with pCG-Gax with Lipofectamine, and then cell lysates were used for blotting with Gax antigen. A lysate from nontransfected cells was used in lane 2. Sera used for blotting were as follows: lanes 1 and 2, anti-Tax rabbit antiserum; lanes 3 to 5, mice in group A (pCG-BL vaccinated and EL4/Gax challenged); lanes 6 to 8, mice in group B (pCG-Tax vaccinated and EL4/Gax challenged); lanes 9 to 11, mice in group C (pCG-d17/5 vaccinated and EL4/Gax challenged); lanes 12 to 14, mice in group D (pCG-Tax vaccinated and EL4 challenged); lane 15, preimmune mouse. (B and C) CTL responses to EL4/Gax cells were determined with different effector/target (E/T) ratios at 7 days after DNA immunization (B) and 15 days after EL4/Gax cell challenge (C). T cells purified from splenocytes of mice from groups A (NC), B (Tax), and C (d17/5) were incubated for 3 days with syngeneic dendritic cells transfected with pCG-Tax by using Lipofectamine. Subsequently, CTL activity against EL4/Gax cells was determined by means of a 5-h 51Cr release assay.

To investigate the role of cell-mediated immune responses in tumor suppression, we examined the potential of T cells derived from the same mice to lyse EL4/Gax cells in a 51Cr release assay. Assays were performed 1 week after the last booster DNA immunization and 15 days after challenge with tumor cells. As shown in Fig. 4B, both wild-type Tax and mutant d17/5 DNA vaccination induced good CTL activity, but control DNA (pCG-BL) vaccination had no effect on CTLs. On the other hand, mice immunized with the pCG-BL control vector showed a relatively high response of CTLs at 2 weeks after s.c. inoculation of tumor cells. This could be explained by the possibility that EL4/Gax challenge cells induced this CTL response as well as the occasional humoral response against Tax protein (Fig. 4A, lane 4), but the induction of immune responses appeared to be too late to protect mice from the vigorous growth of tumor cells. Based on the results of these assays of both humoral and cellular immune responses, we concluded that CTL activity against Tax is responsible for the elimination of EL4/Gax cells in mice immunized with the DNA vaccine.

Reduced expression of Gax in a solid tumor.

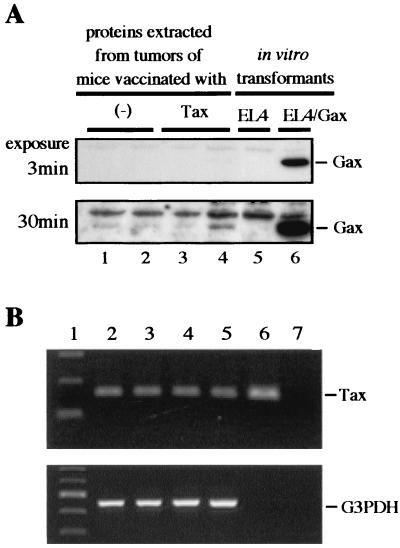

In mice with Tax DNA vaccination, a small solid tumor was found to remain at the injected site without tumor growth. To determine what kind of cells was maintained in vivo with or without DNA vaccination, expression of Gax protein in solid tumors was analyzed. Three weeks after challenge, mice were sacrificed under anesthesia, and tumors were excised and placed in liquid nitrogen. Proteins and total RNA were isolated from these samples and analyzed by Western blotting (Fig. 5A) and RT-PCR (Fig. 5B), respectively.

FIG. 5.

Expression of Gax in vivo. In this experiment, mice were immunized with either pCG-BL (−) or pCG-Tax (Tax), with the schedules described in the legend to Fig. 3A. Solid tumors formed by EL4/Gax cells in mice were removed, and then proteins and RNAs were extracted as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Western blotting with anti-Tax serum. Two samples from each group (lanes 1 to 4) were analyzed. As negative and positive controls, respectively, lysates from cultured EL4 (lane 5) and EL4/Gax (lane 6) cells were blotted. The upper panel shows results with a 3-min film exposure, while the lower panel shows results with a 30-min exposure. (B) RT-PCR of RNA samples from tumors. Lane 1, size markers. RNAs used for RT-PCR were derived from tumors in mice vaccinated with pCG-BL (lane 2), pCG-Tax (lane 3), or pCG-d17/5 (lane 4), or from in vitro EL4/Gax cell cultures (lanes 5 and 7). In lane 6, pR3Gaxbsr was used as a positive control. In lane 7, RT-PCR was performed without reverse transcriptase as a negative control. In the upper panel, a PCR primer set was used to detect Tax, while in the lower panel, PCR was performed with another primer set to detect mouse G3PDH as an internal control.

Expression of Gax protein was scarcely observed in the tumor samples analyzed (two specimens for each group; Fig. 5A, lanes 1 to 4), while the amount of Gax protein in EL4/Gax cells that had been cultured in vitro without a drug remained unchanged for the same period as in the case of in vivo inoculation (lane 6). However, upon longer exposure, bands became visible for tumor samples, indicating a very low level of Gax expression in vivo. RT-PCR analysis also confirmed Gax-specific mRNA expression in tumors of EL4/Gax cells (Fig. 5B). Interestingly, little difference was observed in the intensity of amplified bands between RNA samples from EL4/Gax cells grown in vitro and those grown in vivo. This could be due to a certain bias of PCR, however, so further analysis is required. Nevertheless, the low level of Tax expression in tumor cells suggested that such low expression enabled the tumor cells to evade Tax-specific CTLs, but it was enough to maintain CTL activity against Tax in vivo. In accordance with this notion, an extensively growing tumor in a control mouse and a very small tumor with restricted growth in a vaccinated mouse expressed similar levels of Gax protein at 3 weeks after tumor inoculation, when CTL activity against Tax protein was already observed in both control and vaccinated mice. Thus, the growth of cells per se did not reflect the expression level of Tax; rather, the host immune response against Tax caused the suppression of Gax expression in target tumor cells.

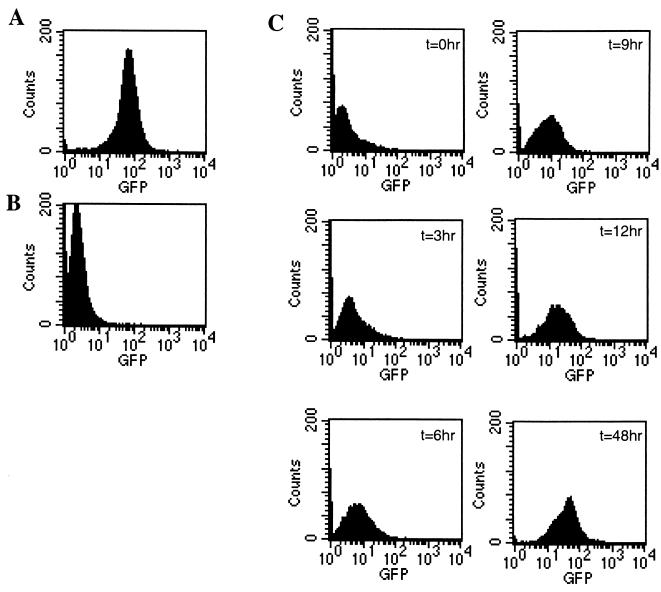

Suppression of Gax gene expression in the peritoneal cavity.

The reduced expression of Gax in EL4/Gax cells in vivo could be a consequence of negative selection by the immune system that eliminates cells with high Gax expression, leaving genetically silenced clones alive. To facilitate examination of the mechanism, EL4/Gax cells were inoculated into the peritoneal cavities of vaccinated C57BL/6J mice to monitor the expression of Gax protein in tumor cells. Mice were immunized four times weekly with the CpG oligonucleotide and with expression vector plasmids for Tax and GM-CSF and were then challenged by i.p. injection of 104 EL4/Gax cells. Three weeks after inoculation, ascitic fluid was collected from these mice and analyzed for Gax expression in cells by flow cytometry. Compared with that in an in vitro culture, expression of Gax decreased dramatically in ascitic fluids, as observed in a solid tumor (Fig. 6A and B).

FIG. 6.

Protein expression of EL4/Gax cells in ascitic fluid. Mice were vaccinated with 50 μg of pCG-d17/5, 10 μg of a GM-CSF expression vector, and 10 μg of a CpG oligonucleotide four times weekly. Two weeks after the last immunization, 104 EL4/Gax cells were i.p. injected. EL4/Gax cells were collected from ascitic fluids and transferred to in vitro conditions at 3 weeks after challenge. Expression of Gax proteins was analyzed before challenge (A) and just after collection from ascitic fluids (B). (C) Reversion of Gax expression after transfer to in vitro conditions. From the time point just after collection of cells from the peritoneal cavity (t = 0 h), Gax expression was analyzed by flow cytometry every 3 h. Gax expression started to show reactivation in 3 h and reached a level almost equivalent with that before in vivo incubation within 12 h.

To determine whether the lack of Gax expression is due to transient silencing of transcription or is a result of negative selection for permanently dormant clones by the immune system, the EL4/Gax cells from ascitic fluids were transferred to in vitro conditions. Gax expression was monitored every 3 h, and it was found that the expression in these cells had already started to increase by 3 h after the beginning of incubation; the maximum level was reached at 48 h (Fig. 6C). This result strongly supports the hypothesis that the suppression of Gax expression is caused by transient silencing of transcription and not by selection of genetically low-expression clones.

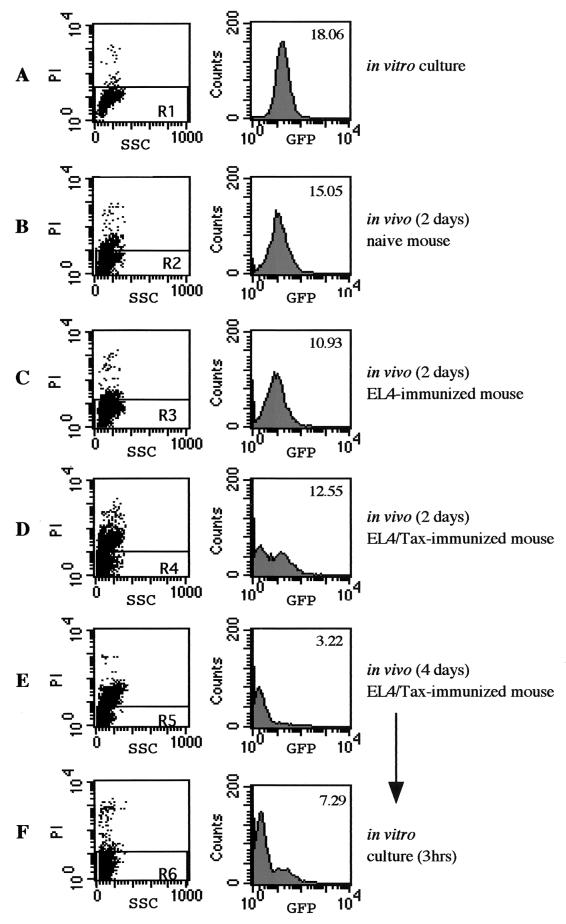

Effects of the immune reaction on Gax gene suppression in the peritoneal cavity.

To analyze the effect of Tax-specific immunity on transient Gax gene suppression, EL4/Gax cells were i.p. inoculated into nonimmunized or Tax-immunized mice, and then Gax expression was monitored by flow cytometry. To induce immune responses against Tax, s.c. injection of EL4/Tax cells, instead of DNA vaccination, was employed as an immunization protocol. Six-week-old C57BL/6J mice were s.c. injected with 105 EL4 or EL4/Tax cells 2 weeks before i.p. challenge with 2 × 107 EL4/Gax cells. Two days after challenge, ascitic fluids were collected from each mouse and cells were stained with PI to exclude dead cells. In a naive (nonimmunized) mouse, 2 days of i.p. incubation resulted in little decrease in Gax expression compared with that in in vitro-cultured cells (Fig. 7A and B). When EL4/Gax cells were inoculated into mice immunized with the parental EL4 cells, a further slight decrease in the Gax expression level was observed (Fig. 7C). In contrast, in the peritoneal cavity of a mouse immunized with EL4/Tax cells, more cells became PI positive, indicating specific killing by Tax-specific immunity, and the level of Gax expression in living cells decreased greatly (Fig. 7D). Thus, Tax immunization resulted in the rapid reduction of Gax expression at the cellular level, although the partial decrease in Gax expression observed in nonimmunized mice could be due to natural immunity or to any changes in the growing condition. The intensity of Gax expression appeared as two peaks 2 days after i.p. inoculation, but i.p. incubation for an additional 2 days left a single peak of lower intensity (Fig. 7E). Since in vitro culture of these cells for 3 h resulted in the reexpression of Gax (Fig. 7F), most of the population expressing lower levels of Gax in the peritoneal cavity were not dead but living cells. These results strongly suggested that EL4/Gax cells with higher Gax expression were rapidly killed in Tax-immunized mice, while lower expressers survived. It was also confirmed that Gax gene modulation in vivo was not due to negative selection of genetically silenced EL4/Gax cell clones, but to cells whose Gax genes were transiently suppressed, while unsuppressed EL4/Gax cell clones were quickly killed by the host immune system.

FIG. 7.

Effects of the immune responses on Gax gene suppression in vivo. C57BL/6J mice were immunized by s.c. injection of either saline (B), 105 EL4 cells (C), or 105 EL4/Tax cells (D and E) cells 2 weeks before i.p. challenge with 2 × 107 EL4/Gax cells. Cells were harvested from an in vitro culture (A), from mice 2 days (B to D) or 4 days (E) after challenge, and after 3 h of in vitro culture following 4 days of incubation in the peritoneal cavity (F). The collected cells were stained with PI and then subjected to flow cytometry analysis. (Left panels) PI staining; (right panels) histograms of GFP fluorescence of the PI-negative population (R1 to R6). Numbers in the right panel indicate mean fluorescence.

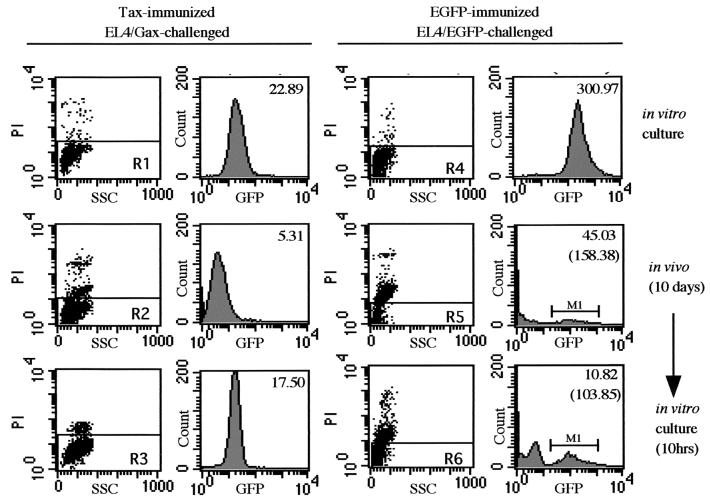

Transient Gax gene suppression.

To determine whether transient exogenous gene suppression occurs generally or not, in vivo gene suppression and in vitro recovery were examined with another exogenous gene product. Six-week-old C57BL/6J mice were immunized by s.c. injection with either 105 EL4/Tax cells or 105 EL4/EGFP cells 2 weeks before i.p. challenge with 2 × 107 EL4/Gax or EL4/EGFP cells, respectively. Ten days after challenge, cells in ascitic fluids were stained with PI and then subjected to flow cytometry. A part of the collected cells from the peritoneal cavity was cultured in vitro for 10 h and also analyzed by flow cytometry. In EL4/Gax cells inoculated into the peritoneal cavities of Tax-immunized mice, transient Gax gene suppression was observed repeatedly (Fig. 8, left panels). When a mouse was immunized with EGFP and then challenged with EL4/EGFP cells, the major population of cells was PI positive and the GFP intensity of the PI-negative population was dramatically decreased (Fig. 8, right panels). The mean fluorescence of EGFP, even in the EGFP-positive fraction (M1), had not recovered after10 h of in vitro culture (Fig. 8, bottom right panel), whereas in vitro culture of EL4/Gax cells isolated from ascitic fluids resulted in reexpression of Gax (from 5.31 to 17.50 in mean fluorescence value [Fig. 8, left histograms]). These data demonstrated that EL4 cells expressing exogenous antigens were killed in the peritoneal cavities of immunized mice, at least in both the cases of Tax and EGFP. However, recovery of expression upon in vitro culture was not a general event for exogenous gene products but rather specific to the Tax gene.

FIG. 8.

Gene suppression of EGFP. C57BL6 mice were immunized by s.c. injection of either 105 EL4/Tax cells (left) or 105 EL4/EGFP cells (right) 2 weeks before i.p. challenge with 2 × 107 EL4/Gax (left) or EL4/EGFP (right) cells. Cells were collected from an in vitro culture (top), just after 10 days of incubation in the peritoneal cavity (middle), or after 10 h of in vitro culture following 10 days of incubation in the peritoneal cavity (bottom). GFP fluorescence was analyzed in the PI-negative population (R1 to R6). Top numbers in histograms indicate mean fluorescence, and numbers in parentheses indicate the mean fluorescence of the M1 region.

It was further suggested that the transient silencing of the proviral genome in HTLV-1-infected lymphocytes helped virus-positive cells to evade eradication by the host immune system, in which cytotoxic T cells specific to the Tax protein are mainly involved. The suppression and reexpression of Gax transcription in this mouse system are in good agreement with the phenomenon observed in HTLV-1-infected CD4+ lymphocytes isolated from ATL and HAM/TSP patients, in which the virus expression suppressed in peripheral blood resumes soon after the transfer of cells to in vitro culture conditions. Although a high provirus load was observed in the peripheral blood of HAM/TSP patients, it was shown that virus replication was strongly suppressed in vivo (10). Therefore, the mouse system established here will provide a suitable model for investigating the apparent equilibrium in vivo between virus expression and the host immune system in individuals persistently infected with HTLV-1.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we established a simple mouse model for investigating the role of Tax-specific immune responses with regard to protection from Tax-expressing tumor cell growth. In C57BL/6J mice immunized with either the wild-type or the null mutant Tax-expressing plasmid, growth of a syngeneic T-cell lymphoma expressing EGFP-fused Tax (EL4/Gax) was strongly inhibited, while the parental EL4 cells grew rapidly to form the largest solid tumor (Fig. 3). This inhibition was Tax specific, because immunization with the empty plasmid vector did not protect mice from EL4/Gax tumor growth. The immune response involved in protection from Gax-expressing tumor cell growth consisted mainly of cellular immunity, since the CTL response, but not antibody production against Tax protein, was observed in mice which had been immunized with Tax DNA. Therefore, we concluded that DNA immunization by direct injection of Tax expression plasmids elicited protective immunity against Tax-expressing tumor cell growth through induction of anti-Tax CTL.

The role of Tax protein in cellular transformation has been well studied (32). The mechanisms of onset of HTLV-1-related diseases, however, have been in contention. In particular, the role of the immune response against Tax is the subject of a key argument; that is, are Tax-specific CTL a protective factor or one of the causes of the diseases? In the case of HAM/TSP and other autoimmune syndromes involving HTLV-1 infection, there have been several reports insisting that Tax is the cause of the diseases. Recently, Hanon et al. showed a significant negative correlation between the frequency of Tax-specific CD8+ T cells and the percentage of CD4+ T cells among peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients infected with HTLV-1 (10). These data suggest the possibility of a protective function of Tax-specific CTL. In this context, it is of note that a mutant Tax protein lacking transforming ability could successfully induce CTL. The results obtained in this study indicate the practical possibility of a DNA vaccination procedure for prophylactic purposes to reduce the onset rates of HTLV-1-related diseases.

Recently, Ohashi et al. reported that Tax DNA vaccine was effective in their rat model (20). In this model, Tax DNA vaccination shortened the period for rejecting syngeneic HTLV-1-immortalized cells, which are able to grow only in syngeneic nu/nu rats. Their results are also consistent with the availability of a DNA vaccine for prophylactic use. However, to assess this possibility, the indicator cells should remain in vivo for a long period. In this respect, EL4/Gax cells stayed at the injected site even in extensively immunized mice in our model system. Thus, it is easy to monitor the fate of EL4/Gax cells and to analyze immune responses in a mouse that has a normal immune system.

The average size of EL4/Gax tumors in control mice was substantially lower than that of EL4 tumors in mice immunized with Tax DNA. These data suggest that some immune response was also elicited in naive mice after challenge with EL4/Gax cells (Fig. 4), and in vitro analysis of CTL activity supported this explanation. In agreement with this, previous studies demonstrated the presence of strong CTL epitopes on Tax protein (12, 14). Thus, mice bearing EL4/Gax tumors should express abundant CTL activity against Tax, irrespective of previous immunization with Tax DNA, and the difference in tumor growth between immunized and nonimmunized mice can be attributed to the initial number of input tumor cells, which should be smaller in immunized mice because of the cytotoxicity of preexisting CTL. Consistent with this explanation, inoculation of an increased number of EL4/Gax cells resulted in failure in protecting the immunized mice from tumor growth (data not shown).

In addition to the number of tumor cells, the expression level of the target antigen in each tumor cell should also determine the fate of an inoculated cell. In this regard, it is of note that the expression level of Gax remained extremely low in vivo (Fig. 5). Since tumor cells with almost undetectable Gax expression did not grow in immunized mice, such a low level of Gax might be sufficient for targeting by Tax-specific CTLs. This seems to be in accord with the observation that HTLV-1 provirus is transcriptionally silent within a high proportion of T lymphocytes in the peripheral blood of HTLV-1-infected patients (19, 24). These facts imply that there is some equilibrium between antigen expression and the host immune system in the peripheral blood of individuals persistently infected with HTLV-1. Furthermore, it has been postulated that the evasion of such equilibrium by escape mutations of the tax gene and/or suppression of the host immune system leads to the development of ATL (9).

The low level of Gax expression in vivo was also confirmed by an experiment in which EL4/Gax cells were transferred to the peritoneal cavity of a Tax DNA immunized mouse (Fig. 6A and B). Although expression of Gax was almost undetectable after 15 days of incubation in the peritoneal cavity, it was restored quickly upon culturing in vitro (Fig. 6C). These data strongly indicated that the expression of Gax was silenced rather transiently, probably through an enhancer/promoter region of HTLV-1 in vivo. This situation greatly resembles the suppression and reexpression of the HTLV-1 provirus genome in virus-positive CD4+ lymphocytes from HTLV-1-infected patients. Hanon et al. attributed the suppression of virus expression in infected cells in vivo to Tax-specific CTL, since the addition of a drug, concanamycin A, that inhibits the function of CTL in an in vitro culture of HTLV-1-positive T lymphocytes resulted in enhancement of the recovery from suppression of virus expression (10). As the mechanism of gene silencing remains unclear, the i.p. EL4/Gax inoculation system will provide a strong tool for investigating the mechanism of transcriptional suppression in vivo . In this context, it is of interest whether the silencing of gene expression involves any intracellular signal transduction or chemical modifications such as CpG methylation of genomic DNA, which has been implicated in most silencing events.

We demonstrated that the higher Gax expressers were rapidly killed in a Tax-immunized mouse but not in a nonimmunized mouse (Fig. 7), suggesting that Tax-specific immune responses play some role, if not all, in the transient suppression in vivo. Although we have not determined what kind of cells directly kill EL4/Gax cells in the peritoneal cavity, preliminary experiments showed that more T cells had infiltrated into the ascitic fluid of a Tax-immunized mouse, while more NK cells were observed in the ascitic fluid of a naive mouse after challenge with EL4/Gax cells (data not shown). We also demonstrated that transient suppression of exogenous gene products was not a general phenomenon, because, although EGFP expression in EL4/EGFP cells was suppressed in an immunization-specific manner, the expression was not recovered upon in vitro culturing. Therefore, transient gene suppression of Gax seemed to be a specific event with regard to the balance between viral gene expression and antivirus immunity.

We developed a simple but very useful mouse model system for investigating the events during the asymptomatic stage of HTLV-1 infection, in which there is a certain equilibrium between the host immune surveillance mechanism and the growth of HTLV-1-infected lymphocytes with limited expression of virus antigen. Studies on the involvement of the immune system in the control of disease progression related to HTLV-1 infection with such a simple mouse model will provide valuable information for protecting infected people from the onset of the diseases.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the Ichiro Kanehara Foundation, a grant from the Japanese Private School Foundation, and a grant from the “Haiteku Research Center” of the Ministry of Education.

We thank M. Inaba for technical advice and N. J. Halewood for language assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abe, J., H. Wakimoto, Y. Yoshida, M. Aoyagi, K. Hirakawa, and H. Hamada. 1995. Antitumor effect induced by granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor gene-modified tumor vaccination: comparison of adenovirus- and retrovirus-mediated genetic transduction. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 121:587-592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ballard, D. W., E. Bohnlein, J. W. Lowenthal, Y. Wano, B. R. Franza, and W. C. Greene. 1988. HTLV-I tax induces cellular proteins that activate the κB element in the IL-2 receptor α gene. Science 241:1652-1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bangham, C. R., S. Daenke, R. E. Phillips, J. K. Cruickshank, and J. I. Bell. 1988. Enzymatic amplification of exogenous and endogenous retroviral sequences from DNA of patients with tropical spastic paraparesis. EMBO J. 7:4179-4184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cann, A. J., J. D. Rosenblatt, W. Wachsman, N. P. Shah, and I. S. Chen. 1985. Identification of the gene responsible for human T-cell leukaemia virus transcriptional regulation. Nature 318:571-574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen, I. S., A. J. Cann, N. P. Shah, and R. B. Gaynor. 1985. Functional relation between HTLV-II x and adenovirus E1A proteins in transcriptional activation. Science 230:570-573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Felber, B. K., H. Paskalis, C. Kleinman-Ewing, F. Wong-Staal, and G. N. Pavlakis. 1985. The pX protein of HTLV-I is a transcriptional activator of its long terminal repeats. Science 229:675-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fujisawa, J., M. Seiki, T. Kiyokawa, and M. Yoshida. 1985. Functional activation of the long terminal repeat of human T-cell leukemia virus type I by a trans-acting factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 82:2277-2281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fujisawa, J., M. Toita, T. Yoshimura, and M. Yoshida. 1991. The indirect association of human T-cell leukemia virus Tax protein with DNA results in transcriptional activation. J. Virol. 65:4525-4528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Furukawa, Y., R. Kubota, M. Tara, S. Izumo, and M. Osame. 2001. Existence of escape mutant in HTLV-I tax during the development of adult T-cell leukemia. Blood 97:987-993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanon, E., S. Hall, G. P. Taylor, M. Saito, R. Davis, Y. Tanaka, K. Usuku, M. Osame, J. N. Weber, and C. R. Bangham. 2000. Abundant tax protein expression in CD4+ T cells infected with human T-cell lymphotropic virus type I (HTLV-I) is prevented by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Blood 95:1386-1392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inoue, J., M. Seiki, T. Taniguchi, S. Tsuru, and M. Yoshida. 1986. Induction of interleukin 2 receptor gene expression by p40x encoded by human T-cell leukemia virus type 1. EMBO J. 5:2883-2888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobson, S., H. Shida, D. E. McFarlin, A. S. Fauci, and S. Koenig. 1990. Circulating CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes specific for HTLV-I pX in patients with HTLV-I associated neurological disease. Nature 348:245-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jin, D. Y., F. Spencer, and K. T. Jeang. 1998. Human T cell leukemia virus type 1 oncoprotein Tax targets the human mitotic checkpoint protein MAD1. Cell 93:81-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kannagi, M., S. Harada, I. Maruyama, H. Inoko, H. Igarashi, G. Kuwashima, S. Sato, M. Morita, M. Kidokoro, M. Sugimoto, S. Funahashi, M. Osame, and H. Shida. 1991. Predominant recognition of human T cell leukemia virus type I (HTLV-I) pX gene products by human CD8+ cytotoxic T cells directed against HTLV-I-infected cells. Int. Immunol. 3:761-767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kannagi, M., S. Matsushita, H. Shida, and S. Harada. 1994. Cytotoxic T cell response and expression of the target antigen in HTLV-I infection. Leukemia 8(Suppl. 1):S54-S9. [PubMed]

- 16.Krieg, A. M., A. K. Yi, S. Matson, T. J. Waldschmidt, G. A. Bishop, R. Teasdale, G. A. Koretzky, and D. M. Klinman. 1995. CpG motifs in bacterial DNA trigger direct B-cell activation. Nature 374:546-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kushida, S., M. Matsumura, H. Tanaka, Y. Ami, M. Hori, M. Kobayashi, K. Uchida, K. Yagami, T. Kameyama, T. Yoshizawa, H. Mizusawa, Y. Iwashita, and M. Miwa. 1993. HTLV-1-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis-like rats by intravenous injection of HTLV-1-producing rabbit or human T-cell line into adult WKA rats. Jpn. J. Cancer Res. 84:831-833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leung, K., and G. J. Nabel. 1988. HTLV-1 transactivator induces interleukin-2 receptor expression through an NF-κB-like factor. Nature 333:776-778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moritoyo, T., S. Izumo, H. Moritoyo, Y. Tanaka, Y. Kiyomatsu, M. Nagai, K. Usuku, M. Sorimachi, and M. Osame. 1999. Detection of human T-lymphotropic virus type I p40 Tax protein in cerebrospinal fluid cells from patients with human T-lymphotropic virus type I-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis. J. Neurovirol. 5:241-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohashi, T., S. Hanabuchi, H. Kato, H. Tateno, F. Takemura, T. Tsukahara, Y. Koya, A. Hasegawa, T. Masuda, and M. Kannagi. 2000. Prevention of adult T-cell leukemia-like lymphoproliferative disease in rats by adoptively transferred T cells from a donor immunized with human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 Tax-coding DNA vaccine. J. Virol. 74:9610-9616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pear, W. S., G. P. Nolan, M. L. Scott, and D. Baltimore. 1993. Production of high-titer helper-free retroviruses by transient transfection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:8392-8396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Pique, C., F. Connan, J. P. Levilain, J. Choppin, and M. C. Dokhelar. 1996. Among all human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 proteins, Tax, polymerase, and envelope proteins are predicted as preferential targets for the HLA-A2-restricted cytotoxic T-cell response. J. Virol. 70:4919-4926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poiesz, B. J., F. W. Ruscetti, A. F. Gazdar, P. A. Bunn, J. D. Minna, and R. C. Gallo. 1980. Detection and isolation of type C retrovirus particles from fresh and cultured lymphocytes of a patient with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 77:7415-7419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Richardson, J. H., P. Hollsberg, A. Windhagen, L. A. Child, D. A. Hafler, and A. M. Lever. 1997. Variable immortalizing potential and frequent virus latency in blood-derived T-cell clones infected with human T-cell leukemia virus type I. Blood 89:3303-3314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sodroski, J., C. Rosen, W. C. Goh, and W. Haseltine. 1985. A transcriptional activator protein encoded by the x-lor region of the human T-cell leukemia virus. Science 228:1430-1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sodroski, J. G., C. A. Rosen, and W. A. Haseltine. 1984. Trans-acting transcriptional activation of the long terminal repeat of human T lymphotropic viruses in infected cells. Science 225:381-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stewart, S. A., G. Feuer, A. Jewett, F. V. Lee, B. Bonavida, and I. S. Chen. 1996. HTLV-1 gene expression in adult T-cell leukemia cells elicits an NK cell response in vitro and correlates with cell rejection in SCID mice. Virology 226:167-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suzuki, T., H. Hirai, J. Fujisawa, T. Fujita, and M. Yoshida. 1993. A trans-activator Tax of human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 binds to NF-κB p50 and serum response factor (SRF) and associates with enhancer DNAs of the NF-κB site and CArG box. Oncogene 8:2391-2397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Turner, J. G., J. Tan, B. E. Crucian, D. M. Sullivan, O. F. Ballester, W. S. Dalton, N. S. Yang, J. K. Burkholder, and H. Yu. 1998. Broadened clinical utility of gene gun-mediated, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor cDNA-based tumor cell vaccines as demonstrated with a mouse myeloma model. Hum. Gene Ther. 9:1121-1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wakimoto, H., Y. Yoshida, M. Aoyagi, K. Hirakawa, and H. Hamada. 1997. Efficient retrovirus-mediated cytokine-gene transduction of primary-cultured human glioma cells for tumor vaccination therapy. Jpn. J. Cancer Res. 88:296-305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wodarz, D., M. A. Nowak, and C. R. Bangham. 1999. The dynamics of HTLV-I and the CTL response. Immunol. Today 20:220-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoshida, M. 2001. Multiple viral strategies of HTLV-1 for dysregulation of cell growth control. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 19:475-496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yoshida, M., J. Inoue, J. Fujisawa, and M. Seiki. 1989. Molecular mechanisms of regulation of HTLV-1 gene expression and its association with leukemogenesis. Genome 31:662-667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoshida, M., M. Seiki, K. Yamaguchi, and K. Takatsuki. 1984. Monoclonal integration of human T-cell leukemia provirus in all primary tumors of adult T-cell leukemia suggests causative role of human T-cell leukemia virus in the disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81:2534-2537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]