Abstract

Summary Background Data:

Patients with Barrett's esophagus (BE) are frequently offered laparoscopic antireflux surgery (LARS) to treat symptoms. The effectiveness of this operation with regards to symptoms and to the evolution of the columnar-lined epithelium remains controversial.

Methods:

We analyzed the course of 106 consecutive patients with BE who underwent LARS between 1994 and 2000, representing 14% of all LARS (754) performed in our institution during that period. All 106 patients agreed to clinical follow-up in 2002 at 40 months (median; range, 12–95 months). Fifty-three patients (50%) agreed to functional evaluation (manometry and 24-hour pH monitoring); 90 patients (85%) to thorough endoscopy, with appropriate biopsies and histologic evaluation to determine the status of BE.

Results:

Heartburn improved in 94 (96%) of 98 and resolved in 69 patients (70%) after LARS. Regurgitation improved in 58 (84%) of 69 and dysphagia improved in 27 (82%) of 33. Distal esophageal acid exposure improved in 48 (91%) of 53 patients tested and returned to normal in 39 patients (74%). One patient underwent reoperation 2 days after fundoplication (gastric perforation). Preoperatively, biopsy revealed BE without dysplasia in 91 patients, BE indefinite for dysplasia in 12 patients, and low-grade dysplasia in 3 patients. Fifty-four of the 90 patients with endoscopic follow-up had short-segment BE (<3cm), and 36 had long-segment BE (>3cm) preoperatively. Postoperatively, endoscopy and pathology revealed complete regression of intestinal metaplasia (absence of any sign suggestive of BE) in 30 (55%) of 54 patients with short-segment BE but in 0 of 36 of those with long-segment BE. Among patients with complete regression, 89% of those tested with pH monitoring had normal esophageal acid exposure. This was observed in 69% of those who failed to have complete regression. One patient developed adenocarcinoma within 10 months of LARS.

Conclusions:

In patients with BE, LARS provides excellent control of symptoms and esophageal acid exposure. Moreover, intestinal metaplasia regressed in the majority of patients who had short-segment BE and normal pH monitoring following LARS, a fact that was, heretofore, not appreciated. LARS should be recommended to patients with BE to quell symptoms and to prevent the development of cancer.

This paper depicts the long-term clinical and pathologic outcome of laparoscopic antireflux surgery in 106 patients with Barrett's esophagus (BE). The majority of patients experience durable relief of reflux symptoms and have either significant reduction in or normalization of esophageal acid exposure on 24-hour pH monitoring. Moreover, 56% of patients with short-segment BE had complete regression of their intestinal metaplasia.

Barrett's esophagus (BE) is an acquired abnormality that is characterized grossly by an upward displacement of the squamo-columnar junction, with replacement of the typical whitish smooth esophageal mucosa by a velvety, reddish mucosa. Microscopically, BE is characterized by the presence of specialized intestinal metaplasia. It is associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and it is found in 15 to 20% of patients with GERD.1,2 The incidence of BE appears to have increased dramatically in the last 20 years,3 a fact that has been linked to the 10-fold increase in the incidence of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus observed during the last decade.4

It has been recommended that the treatment of BE be directed at controlling the symptoms of GERD, on the understanding that BE represents an irreversible lesion with its own unmodifiable chance of progression to cancer. Medical therapy is often inadequate to completely relieve symptoms, and even if symptoms are successfully relieved abnormal amounts of reflux persist.5 Surgical therapy for GERD provides better symptom control than medical therapy.6 These patients, however, are more likely to have larger hiatal hernias, esophageal inflammation, or a shortened esophagus, thus represent difficult surgical repairs. As a result, the long-term results of surgical therapy have been questioned.7

Whether the natural history of BE can be affected by intervention is still matter of debate. Medical therapy does not lead to regression of the intestinal metaplasia and does not modify its risk of progression to dysplasia and cancer.8 Ablative techniques exist, but are currently complicated and investigational.9–11 Recent reports suggest that an effective antireflux operation may halt the progression of BE, and in some patients encourage its regression.12,13

In this study we sought to determine the effectiveness of laparoscopic antireflux surgery for BE in long-term symptom control and in esophageal acid exposure. Furthermore, we wished to determine the effects of surgery on the histology of the esophageal mucosa and evaluate its impact on the chances of developing adenocarcinoma.

METHODS

Using the University of Washington Swallowing Center database where all 4507 patients who have been seen and evaluated at our center since 1993 have had their symptoms, functional, endoscopic, and radiologic evaluation prospectively entered, we identified all patients with BE who had undergone a laparoscopic antireflux procedure at our institution between 1994 and 2000. All patients were then contacted during 2002, so that every patient had at least 1 year of follow-up. We were able to contact every patient identified; our follow-up is 100% complete at a mean of 43 months (median, 40 months; range, 12–95 months). At the time of follow-up, every patient underwent a full clinical evaluation using the same format as in their first visit to our clinic. In addition, at this time we collected and reviewed their most current endoscopies and biopsies and invited every patient to undergo a repeat manometric and 24 hours pH monitoring evaluation. The data were reported as of last follow-up (2002), and all comparisons are with the initial observations as recorded in our database. This study was approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board (University of Washington HSD: 01-7645-E02) Initial and follow-up clinical, functional, and histologic characterization in these patients were as follows.

Clinical Evaluation

Symptoms were rated on a frequency scale from 0–4: 0, never; 1, once per month; 2, once per week; 3, once per day; 4, several times per day. Any frequency that fell between 2 numbers was upgraded to the higher number. We posed questions on twenty-two symptoms: 11 gastrointestinal (heartburn, regurgitation, abdominal pain, belching, dysphagia to liquids and solids, bloating, nausea, chest pain, odynophagia, globus) and 11 extraesophageal (coughing, hoarseness, wheezing, laryngitis, aspiration, choking, dyspnea, sore throat, asthma, bronchitis, pneumonia).

Symptom improvement was defined as a decrease in the symptom frequency (eg, 4 to 2), and resolution by the absolute absence of that symptom postoperatively when present preoperatively (frequency score of 0).

Manometry

A water-perfused 8-channel catheter (4 radial ports at the same level and 4 separated by 5-cm intervals) was used to assess esophageal pressures with the patient in the supine position. The lower esophageal sphincter (LES) was examined with 4 radial ports. A station pull-through measurement of the LES pressure determined the characteristics of the sphincter. The LES pressure was averaged over a series of 3 respiratory cycles. The peristaltic pump of the esophageal body was assessed over a minimum of 10 episodes of deglutition with 5-mL aliquots of water. The upper esophageal sphincter (UES) location, pressure, and relaxation were measured with the 4 radial ports before completion of the procedure.

24-hour Esophageal pH Monitoring

Ambulatory 24-hour pH monitoring was performed using a dual probe catheter. The distal probe was located 5 cm above the manometrically determined LES. The proximal probe was located 10 cm above the distal probe. A portable digital data logger (Synectics Medical Inc., Shoreview, MN) was used to record pH fluctuations, while the patient recorded symptoms in an event diary. All data were downloaded and analyzed by a computer program. Abnormal acid exposure was defined as a pH < 4 more than 1% of the total time in the proximal channel and more than 4% in the distal channel, or a DeMeester composite score > 14.7.

Upper Endoscopy

Upper endoscopy with biopsies was performed by the referring gastroenterologists in all cases. Equivocal biopsy results were interpreted by a second pathologist at the University of Washington. Resolution of BE postoperatively was defined as the absence of obvious BE on endoscopy and no evidence of intestinal metaplasia on biopsy.

Statistics

The Mann-Whitney U test was used to assess symptom scores prior to and after fundoplication. A paired, Student t test was used to assess the pH monitoring and manometry results. Significance was accepted at P < 0.05. All values are given as mean ± SD unless otherwise specified.

RESULTS

Between 1994 and 2000, 106 patients (67 male, 39 female; mean age, 50 years; range, 22–77 years) with endoscopic and histologic confirmation of BE underwent a laparoscopic antireflux procedure at our institution. This represented 14% of all LARS performed during that period of time. Eighty-two (77%) of the 106 patients had a primary Nissen fundoplication, 6 (6%) had a redo Nissen fundoplication (ie, they had undergone a previous, unsuccessful repair elsewhere), 9 (8%) had a partial posterior fundoplication (modified Toupet) because of ineffective esophageal motility, and 9 (8%) had a paraesophageal hernia repair and a Nissen fundoplication.

Fifty-four (51%) of the 106 patients agreed to manometry, and 53 (50%) to 24-hour pH monitoring postoperatively. Postoperative endoscopic surveillance for BE was carried out in 90 patients (85%).

Clinical Results

Symptoms

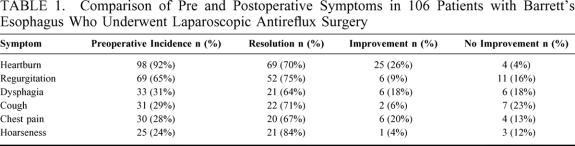

Heartburn and regurgitation were the most common presenting symptoms occurring in 92% and 65% of patients, respectively. Other common preoperative symptoms included dysphagia, cough, chest pain, hoarseness, and wheezing (Table 1). After LARS, heartburn improved in 96% of patients and regurgitation in 84%. Atypical symptoms such as cough, chest pain, and hoarseness were less common, but resolved in the majority of patients (Table 1). Dysphagia, which was a prominent feature in 33 patients preoperatively improved or disappeared in 27 of them and did not change in 6 patients. New dysphagia (ie, the patient did not experience it preoperatively) developed and persisted in 10 patients after operation; it was considered mild (< once/wk) in 8 of the 10 patients.

TABLE 1. Comparison of Pre and Postoperative Symptoms in 106 Patients with Barrett’s Esophagus Who Underwent Laparoscopic Antireflux Surgery

Thirteen patients (12%) had a peptic stricture before operation. This did not have a significant impact on the resolution of symptoms. All patients with a stricture had improvement in heartburn, regurgitation, and chest pain after operation. Eleven patients (85%) with stricture experienced lasting improvement of dysphagia after operation.

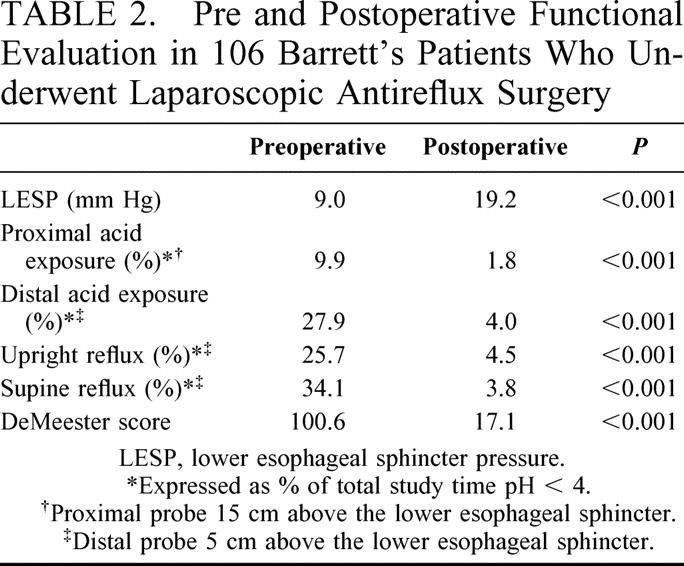

Motility

Manometry was performed preoperatively in ninety-three patients (87%). The mean lower esophageal sphincter pressure (LESP) was 9.0 mm Hg (± 7.8). Fifty-four patients (51%) returned for postoperative manometry. The mean LESP was significantly increased postoperatively (19.2 mm Hg; P < 0.001) (Table 2).

TABLE 2. Pre and Postoperative Functional Evaluation in 106 Barrett’s Patients Who Underwent Laparoscopic Antireflux Surgery

Twenty-five patients had ineffective esophageal motility, defined as an average amplitude in the distal esophagus ≤ 30 mm Hg and/or ≤ 70% propagation of peristaltic waves before operation. Fourteen of these patients returned for postoperative monitoring, and 6 (43%) had normal peristalsis. Thus, the operation appeared to have restored normal peristalsis in over 40% of the patients who had abnormal motility preoperatively.

pH Monitoring

Preoperative 24-hour pH monitoring was performed in 89 patients (83%) preoperatively. The average proximal acid exposure (15 cm above the LES) was 9.9%, and distal acid exposure (5 cm above the LES) was 27.9%. The mean DeMeester score was 100.6 before operation. Fifty-three patients (50%) returned for postoperative pH monitoring. Acid exposure in the distal and in the proximal esophagus was significantly reduced in these patients. It was entirely within normal limits in 39 of the 53 (Table 2).

Fourteen of the 53 patients had abnormal postoperative acid exposure on 24-pH monitoring. In 9 (64%) of these patients there was a significant reduction from preoperative values. Among these fourteen, 9 patients (64%) had factors other than BE that might predict a higher rate of failure: reoperation (n = 2), paraesophageal hernia (n = 2), ineffective esophageal motility requiring a partial fundoplication (n = 2), peptic stricture with a foreshortened esophagus (n = 2), and a gastric perforation recognized 2 days after initial operation requiring repair and revision of the fundoplication.

Recurrent Hiatal Hernia

Of the 90 patients who underwent an endoscopy, 8 (9%) had a recurrent hernia identified. The hernia was small (<3 cm) in all patients. Most patients with a hernia were asymptomatic (5 of 8; 63%); 2 of these patients had abnormal acid exposure on 24-hour pH monitoring. No patient to date has required a reoperation for recurrent symptoms, hiatal herniation, or recurrent reflux.

Pathologic Results

All 106 patients had preoperative histologic confirmation of intestinal metaplasia. The biopsy was indefinite for dysplasia in 12 patients and revealed low-grade dysplasia in 3 patients.

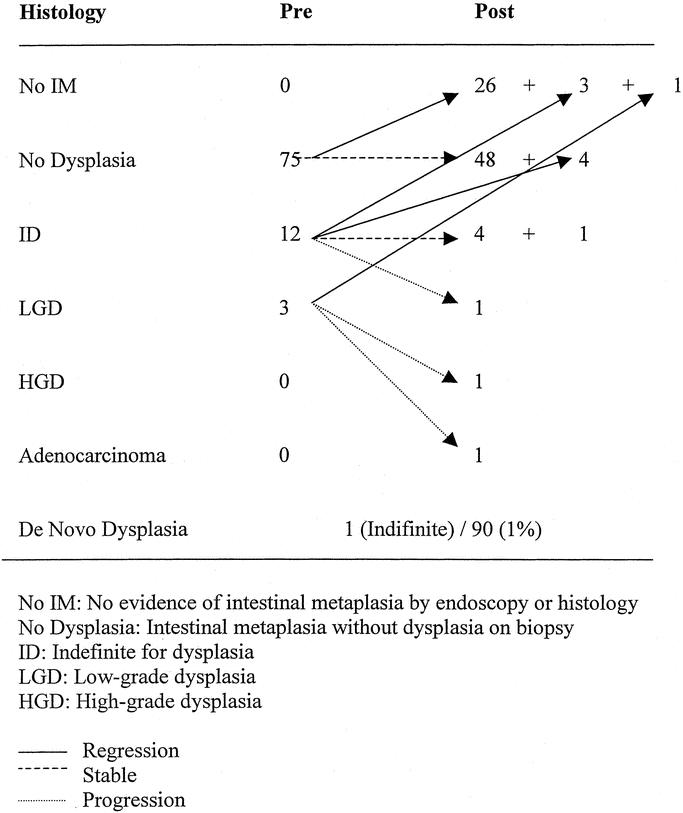

Endoscopy was completed postoperatively in 90 (85%) of 106 patients. The median endoscopic follow-up was 30 months (range, 5–97 months). In their most recent biopsy, 30 patients (33%) had no evidence of intestinal metaplasia, 52 had intestinal metaplasia without dysplasia, 5 biopsies were indefinite for dysplasia, 1 had low-grade dysplasia, 1 had high-grade dysplasia, and 1 developed adenocarcinoma (Fig. 1). The patient who developed cancer started with low-grade dysplasia in a 16-cm segment of BE and was found to have high-grade dysplasia on surveillance endoscopy 7 months after operation. Follow-up biopsy 10 months postoperatively revealed adenocarcinoma. The resected specimen revealed a T1N0M0 tumor, and she is now NED at 5 years and 10 months. The patient who developed high-grade dysplasia had persistent low-grade dysplasia for 3 years after operation, then developed recurrent reflux symptoms, was placed back on medications, and a year later had high-grade dysplasia. This patient had an abnormal 24-hour pH monitoring. (Fig. 1)

FIGURE 1. Fate of the Barrett's epithelium in patients with endoscopic follow-up. Fate of the Barrett's epithelium after LARS in patients with endoscopic follow-up.

In those patients with regression, 24-hour pH monitoring was normal in 8 (89%) of the 9 patients tested. Of those patients without regression, pH monitoring was normal in 30 (69%) of 43 patients.

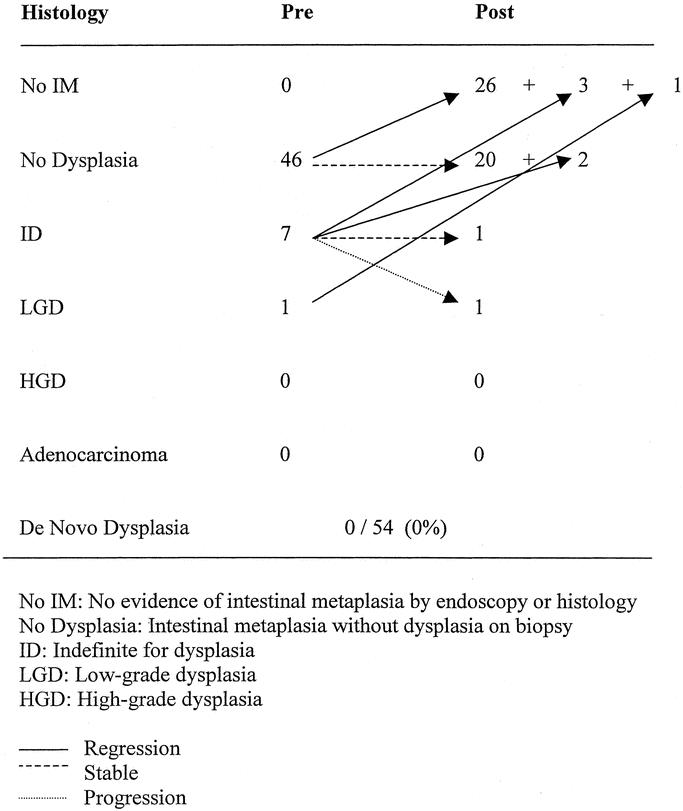

Short-segment BE

Fifty-four (60%) of the 90 patients who returned for endoscopy had short-segment BE (≤3 cm) before operation. Thirty (56%) of these 54 patients had no evidence of metaplasia at last follow-up. No patient in this group progressed to cancer. The fate of the epithelium after LARS in short-segment BE is reported in Figure 2. Nine of the patients in whom there was regression had a pH study; in all patients (100%) there was a reduction in acid exposure, and it was completely normal in 8 (89%). Sixteen patients who had no regression had a pH study, it was normal in 9 (56%) and abnormal in 7 (44%). There was no significant difference in age, length of endoscopic follow-up, type of operation, or presence of strictures between those with and without regression.

FIGURE 2. Fate of the Barrett's epithelium after LARS in patients with endoscopic follow-up; short-segment only (< 3cm).

Long-segment BE

Thirty-eight (41%) patients that returned for endoscopy had long-segment BE (>3 cm) before operation. None of the patients with more than 3 cm of BE had complete regression. Six patients had a reduction in the length of BE (>2 cm), but in only thirteen patients was the pre and postoperative length measured accurately enough to assess this.

DISCUSSION

The goals of surgical therapy in patients with BE are: long-term control of reflux symptoms, the provision of a durable gastro-esophageal barrier to acid and bile, and the elimination of BE or at least the decrease of the risk for developing adenocarcinoma. There is considerable controversy as to whether the operation achieves these goals. First, these patients have a much more defective LES and a more virulent form of GERD, which leads to greater esophageal damage than patients with GERD but no BE.14–16 The operation is therefore more complex, the number of complications greater,17 and the chances of a successful long-term outcome in terms of competency of the cardia decreased.7,12 Secondly, there is generalized belief that once BE develops, correction of reflux does not alter its natural history. This concept has been recently challenged.12,13 Our study was designed to test the hypothesis that, in a high-volume referral center using the techniques available today for mobilization of the esophagus, the operation could be accomplished with minimal morbidity and good long-term outcomes. Furthermore, we wished to determine what the fate of Barrett's epithelium might be in a large number of patients in whom the competency of the cardia was restored. We have shown that, although not perfect, under the conditions of this study LARS can accomplish all 3 goals of therapy.

Clinical Results

Symptom Control

We found that at a mean follow-up of 43 months, 95% of our BE patients continued to report improvement of their preoperative heartburn and regurgitation, which is similar to what we have reported for patients without BE after LARS.18 Furthermore, dysphagia, which was associated with impaired motility in many of the patients, improved in over 80% of those who presented with it. Other symptoms of GERD also responded well and remained absent several years after the repair.

Other studies have reported that although symptom control is good for patients with BE, it is inferior to those achieved in patients with uncomplicated reflux disease.19–22 One report suggested that the results are so much worse (half of patients considered long-term failures) that the authors stopped performing standard antireflux operations in patients with BE.7,23 In a recent prospective randomized trial of medical versus surgical therapy, Parrilla et al found that symptoms were controlled in over 80% of patients in both treatment arms.24

Long-term outcomes after LARS are sparse because of the short existence of laparoscopy. Farrell et al reported that their excellent short-term results remained in place with longer follow-up (2–5 years), suggesting that LARS had durable effects, although not as good as those observed in patients without BE.22 Since we were able to obtain information on symptoms in all 106 patients in our study during 2002 at a mean follow-up of 43 months and since we compared the symptoms reported in 2002 to those they had reported at their initial visit using a patient-filled questionnaire, we believe that our observations are real and represent the medium to long-term outcome of this large group of patients.

Physiologic Results

The restoration of a durable barrier to reflux at the gastroesophageal junction is the ultimate objective of any antireflux operation. We18 and others25 have found that symptoms are not always a reflection of a competent cardia. Indeed, in patients who experience a substantial reduction of reflux by medication or by operation, symptoms may be absent while reflux persists. For example, up to 80% of patients whose symptoms are under control with medical therapy continue to have abnormal acid exposure.5

Our intervention had a dramatic effect in decreasing esophageal acid exposure. However, we found that 14 (26%) of 53 patients tested still had abnormal values, despite the fact that 9 of them had experienced a substantial reduction from their preoperative values. We found that most of these patients had complicating factors that may make failure or ineffective operations more likely. These included reoperations (n = 2), paraesophageal hernia repair (n = 2), ineffective esophageal motility requiring a partial fundoplication (n = 2), a peptic stricture with a short esophagus (n = 2), and a gastric perforation requiring an acute reoperation and revision of the fundoplication. The 26% failure to achieve normalization of acid exposure in this study may be an overestimation, because all patients who returned with symptoms underwent 24-hour pH monitoring as part of their evaluation while only some (<40%) of the totally asymptomatic patients agreed to this test postoperatively. While this may be the case, the findings of this study underscore the impact that associated anatomic abnormalities have on the results of surgery in patients with BE and suggests that earlier referral to surgical therapy (ie, before complications develop) may be important to improve the chances of a successful outcome.

There is a relationship between competency of the cardia and anatomic integrity of the repair. We observed an anatomic recurrence rate of 9%, which while lower than most other reports7,12,17,24 is still higher than our 2% for non-BE patients. While our findings support a higher incidence of anatomic abnormalities at a time of operation, we attribute our relative success to a very careful technique that includes a substantial mobilization of the esophagus a meticulously constructed fundoplication and the securing of the fundoplication to the esophagus and the hiatus.26 In this sense, a high-volume center and the utilization of advanced laparoscopic techniques may offer a unique advantage.

Pathologic Results

The third goal of therapy, and perhaps the most important in patients with BE, is the potential positive impact that restoration of competency to the cardia may have on Barrett's epithelium. This may mean complete regression (ie, a “cure”) or a decreased risk of progression to dysplasia and cancer.

Regression of Intestinal Metaplasia

Only patients with intestinal metaplasia are at risk for developing adenocarcinoma; if the metaplastic cells disappear, so should the risk of cancer. Several reports have shown that medical therapy does not result in the regression of BE.27 In 1980, Brand et al first reported regression after surgery in 4 of 10 patients.28

We were extremely gratified by the finding that 55% of our patients with short-segment BE (and 33% of all patients) experienced a complete regression of their Barrett's epithelium. The fact that complete regression was observed exclusively in patients with short-segment BE is not surprising. Bowers et al, reported that regression of BE after LARS was more common among patients with short-segment BE.13 In fact, of the 22 such patients reported by their group, 13 patients (59%) experienced regression. Furthermore DeMeester reported that 73% of patients with BE confined to the GEJ resolved after surgery.19 If, as most recent studies on pathogenesis of BE suggest, the disease is initially localized and nonvisible and then becomes progressively longer, the results of our studies combined with the findings of these 2 other studies would strongly suggest that earlier referral to surgery for patients with BE may yield the best results in terms of cure of the disease.

Since BE carries with it a risk of progressing to adenocarcinoma, the most effective form of therapy would be directed at decreasing this risk while providing symptom relief. However, this is not currently included as a priority of treatment by most practitioners. In fact, the Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology states the goal of treatment of BE should be “the control of the symptoms of GERD.”29 In contrast to medical therapy, surgical therapy, by reducing the refluxate that contributes to the ongoing injury, may be able to control symptoms and induce a complete regression.

Progression of Intestinal Metaplasia to Cancer

The demonstration that any form of therapy reduces the risk to develop adenocarcinoma among patients with BE is difficult. However, there is data from studies of the natural history of the disease that provide some baseline information. For example, Rudolph et al reported a 3.4 per year chance of progression to cancer in a group of 309 patients followed for a mean of 3.8 years, the risk was 0.8 if 1 excluded patients who initially had high-grade dysplasia.30

Our findings support the premise that an effective antireflux barrier reduces the progression of BE. None of our patients without dysplasia before operation progressed to high-grade dysplasia or cancer. Only 1 of our patients was found to have adenocarcinoma, but this occurred within a year of operation. This patient had a long segment of intestinal metaplasia with low-grade dysplasia. Given the short period of time, it is probable that this focus was either missed before operation, or the dysplasia-carcinoma sequence was irreversible at the time of operation. In fact, in most studies of natural history of BE, patients who develop a cancer within 6 months to a year are excluded as they are thought to have harbored the disease when first seen.31 Nevertheless, if we included this patient this would be 1 cancer in 274 patient years of follow-up (incidence of 0.3% per year). McDonald and colleagues have shown that most cancers after antireflux surgery present in the first year postoperatively, suggesting that in these patients the dysplastic process had entered an irreversible phase before the operation. They also found that very few patients develop HGD or cancer when followed for longer periods.32

We did, however, have 1 patient with long-segment BE progress from low-grade to high-grade dysplasia after surgery. This patient had a recurrence of reflux and symptoms more than a year before the development of high-grade dysplasia, which underscores the need for complete correction of abnormal reflux. Because he was only 55, healthy, and had multifocal high-grade dysplasia in a 6-cm segment, he was treated with esophagectomy. There was no evidence of carcinoma in the resected specimen. Our findings in these 2 patients underscore the need for thorough endoscopic examination and meticulous biopsies both before and after operation, especially in patients with long segments and dysplastic epithelium.

At the same time, however, the majority of patients (10 of 15) with preoperative evidence of dysplasia regressed to nondysplastic metaplasia or to normal (no BE) after LARS. This supports the findings from other groups, which have demonstrated up to a 70% chance of regression of dysplasia after successful antireflux surgery.19,33,12 Thus, it appears that if the integrity of the antireflux mechanism is restored and remains intact over several years preventing the continued injury from gastric and duodenal contents, patients with BE have a good chance of disease regression.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study strongly suggests that LARS, while not perfect, is currently the most effective treatment of patients with BE. In fact, typical reflux symptoms improved in 96% of our patients, an efficient gastroesophageal barrier was restored in the majority of the patients, and there were few objective functional or anatomic failures. We found that the operation eliminated BE in over 55% of patients with short segments and that progression of metaplasia to dysplasia or cancer was rare. Furthermore, since regression requires normalization of acid exposure and since this is easier to achieve in patients who have not developed additional anatomic complications from their disease, the findings of this study support the indication of surgery in all patients with BE at the earliest possible stage.

Discussion

Dr. John G. Hunter (Portland, Oregon): There is no quicker way to anger a gastroenterologist than to proclaim that laparoscopic Nissen Fundoplication should be used in patients with GERD and Barrett’s esophagus to prevent esophageal cancer, and yet the last line of the abstract accompanying this paper states that ‘laparoscopic antireflux surgery should be offered to patients to prevent the development of cancer.’ Where does the truth lie? Why do GI docs get twisted up inside by such proclamations? The facts are these: First, patients with Barrett’s esophagus may develop cancer after Nissen fundoplication. In a superb review of the subject performed by Steve and Tom DeMeester a couple of years ago, the incidence of cancer reported in follow-up of Nissen fundoplication was 3%. Whatever the protective effects of Nissen may be, surgically treated Barrett’s patients need equivalent endoscopic surveillance to patients on medical therapy. Secondly, the incidence of cancer in medical surveillance studies of Barrett’s is 0.5% per year or 1 in 200 patient years of follow up. The incidence of cancer in Dr. Oschlanger’s series was 0.4% or 1 in 276 years of follow up, not significantly different from those under medical surveillance. It would take well over a thousand years of cancer free follow up to develop adequate statistical power in this series.

But, before we discount the claim made be the authors, lets look at 2 more facts: First, published or presented during the last 2 years are 4 similar series with similar findings, and no recent study with contradictory findings. Added together these studies represent nearly 1,500 patient years of follow up after laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication with only 1 cancer reported, the 1 that was detected 10 months after lap Nissen in this series. If one takes the statistically risky step of summing the concordant data in these 5 studies, perhaps we can more confidently state that fundoplication provides better protection against malignant transformation than medical therapy alone in Barrett’s patients. Additionally, this study and the others previously mentioned demonstrate histologic and endoscopic regression of short segment Barrett’s esophagus. While critics of this finding cite sampling error as the culprit for believing Barrett’s regressed after surgery, it is hard to dispute this claim after the observation has been so frequently made by investigators with very aggressive biopsy strategies. Thus, it follows that elimination of the premalignant lesion, intestinal metaplasia, should reduce or eliminate the risk of developing adenocarcinoma.

This well written paper provides a wealth of information about the natural history of Barrett’s, surgically treated. I have several questions:

How confident are you that regression of metaplasia is an adequate surrogate for cancer protection?

Suzie Kim demonstrated nicely that pre and post op measurements of the squamocolumnar junction may vary by 3 to 5 cm as a result of esophageal dissection and elongation. How confident are you that the endoscopic and histologic regression seen in 55% of patients with short segment Barrett’s doesn’t represent a measurement problem, that the presumed GE junction within the fundoplication was instead the inferiorly displaced squamocolumnar junction, and the regression noted was exclusively histologic?

In the cohort with short segment Barrett’s it was noted that those without reflux postoperatively were more likely to regress than those with an abnormal pH study. Was this difference statistically significant?

The 1 cancer in this series occurred in a patient with long segment Barrett’s and a pre op diagnosis of low-grade dysplasia. It is our policy to follow this patients for a minimum of 6 months and 2 biopsy sessions before performing fundoplication to make sure high-grade dysplasia and/or cancer is not missed. How was this patient managed preoperatively?

Fourteen patients had an abnormal pH score postoperatively. It is stated that these patients had factors that might predict Nissen failure, but it is not stated whether these were the same patients who developed anatomic failure. Was this the case? If not, is it the author’s belief that one can reflux through an intact Nissen?

Nine patients in this series had an anatomic failure, most commonly a reherniation of the fundo, as compared with 2% of patients without Barrett’s. Why are Barrett’s patients more prone to recurrent hernia? Is it possible that esophageal foreshortening might have been responsible for these failures?

I wish to thank Dr. Oshlanger and Dr. Pellegrini for the honor of discussing their tremendous work, and thank the American Surgical for the privilege of the floor.

Dr. Carlos A. Pellegrini (Seattle, Washington): Thank you, Dr. Hunter. The answer to your first question, regarding how confident we are that regression of metaplasia protects against the development of cancer has 2 parts. First, we believe that if Barrett’s has disappeared, completely, the patient is protected from cancer, but we do not know at this time if in some of these patients Barrett’s will return, thus, we recommend surveillance following the guidelines of the American College of Gastroenterology. Second, regression does not occur in all patients, thus it is important to continue surveillance after the operation, adapting the frequency of endoscopy to the findings at any given time.

You asked if the changes observed could be due to the ‘lowering’ of the squamous columnar junction that occurs with most antireflux operations. It is not. We are aware of the work of Kim, and because of that we have examined the entire esophagus as well as esophagogastric junction with retroflexed viewed and obtained biopsies of it. Only when the biopsies have shown no evidence of Barrett’s throughout the entire esophagus and the junction have we called it complete regression. Could this be a sampling error? Unlikely given the fact that we obtain multiple biopsies, but ultimately just as possible as any sampling error before the operation.

Although we noted that in patients with short Barrett’s complete regression occurred more commonly among those who had a complete correction of their reflux, the numbers were not statistically significant.

The patient who developed cancer had diagnosis of low-grade dysplasia before the operation. She had a very long segment, in fact almost her entire esophagus had Barrett’s. She had been followed preoperatively for quite some time by the gastroenterologist who sent her to us. We proceeded with her operation and then she enrolled in the UW longitudinal follow-up study and underwent a mapping of the esophagus with biopsies as per our protocol. She was found to have high-grade dysplasia and a localized (T-1) adenocarcinoma for which she underwent total esophagectomy within the first year of her antireflux procedure. I am almost certain she either had this lesion preoperatively or had already started its development before her operation. She is now health, has NED and is 6 years after her operation.

You wanted to know if all patients who had abnormal pH monitoring postoperatively had an anatomically identifiable problem, and the answer is no. We found patients with both functional and anatomic recurrence but we also found among the 14 patients who had reflux, several with what radiologically appeared to be a normal looking wrap.

Lastly you asked if a short esophagus may have contributed to some of the recurrences. I believe that – as a group – Barrett’s patients have a more scarred esophagus than non-Barrett’s patients and this may predispose them to recurrence.

Dr. Tom R. DeMeester (Los Angeles, California): Dr. Pellegrini, I greatly appreciated this paper because it adds to the growing knowledge that surgical therapy can interrupt the natural history of gastroesophageal reflux disease. This message needs to be disseminated, particularly to the gastroenterologists who don’t appreciate what surgery can do for this disease. I have 2 questions:

First, what was your criteria for regression? The criteria has been debated because of the possibility of sampling error. We have come to the conclusion that there must be evidence of regression on 2 endoscopies done on separate occasions to assure that the findings were not due to a sampling error.

Second, you have shown that the control of the symptoms is not the key objective in this disease, rather it is cessation of reflux that gives the protection and also controls symptoms. If this is true, do you recommend that patients have the competency of the repair documented by 24-hour pH monitoring 1 year after the procedure? If so, how would you manage a patient who 1 year after their operation has a positive 24-hour test and is asymptomatic? Would you recommend that their repair be redone?

Dr. Carlos A. Pellegrini (Seattle, Washington): Dr. DeMeester made a very important point in his discussion. When Barrett’s is not found, the patient should be advised to undergo another endoscopy within a year. If a complete absence of Barrett’s is again documented, then we would recommend that he or she undergo another endoscopy at 3 to 5 years. We do not have anyone that has gone that far, but I presume that if Barrett’s remains absent on this third endoscopy we should assume the patient is cured. The point is still valid: a single endoscopy which fails to show Barrett’s in a patient who, preoperatively, had Barrett’s is not enough. We agree entirely with your second point: our data strongly suggests that complete control of reflux is the key for regression.

You asked what to do with those in whom we find asymptomatic reflux postoperatively. I would offer the following observation. First, we are now convinced that it is important to perform 24-hour pH monitoring in all these patients postoperatively regardless of symptoms. Second, in the past we have not recommended reoperation. However, a recent observation makes us question this practice. Indeed, we had a man in his mid-50s who was symptomatic for the first 3 years postoperatively. He then redeveloped reflux (symptoms and pH monitoring positive), we followed him, and within 2 more years he developed high-grade dysplasia. Because it was multifocal and because his Barrett’s extended for 6 cm and he was young and fit, last week we did an endoscopy. The specimen showed high-grade dysplasia only. Perhaps this patient should have had a second antireflux procedure 2 years ago.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by the Mary and Dennis Wise Fund and in part by an educational grant from United States Surgical Corporation, Tyco Healthcare.

Reprints: Brant K. Oelschlager, MD, University of Washington Medical Center Department of Surgery 1959 NE Pacific Street Box 356410 Seattle, WA 98195-6410. E-mail: brant@u.washington.edu

REFERENCES

- 1.DeMeester S, DeMeester T. Columnar mucosa and intestinal metaplasia of the esophagus. Ann Surg. 2000;231:303–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirota W, Loughney T, Lazas D, et al. Specialized intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, and cancer of the esophagus and esophagogastric junction: prevalence and clinical data. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:277–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conio M, Cameron A, Romero Y, et al. Secular trends in the epidemiology and outcome of Barrett's oesophagus in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Gut. 2001;48:304–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pera M, Cameron A, Trastek V, et al. Increasing incidence of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and esophagogastric junction. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:510–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katzka D, Castell D. Successful elimination of reflux symptoms does not insure adequate control of acid reflux in patients with Barrett's esophagus. Am J Gastroenterology. 1994;89:989–991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lundell L, Mittinen P, Myrvold H, et al. Continued (5-year) follow-up of a randomized clinical study comparing antireflux surgery and omeprazole in gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;192:172–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Csendes A, Braghetto I, Burdiles P, et al. Long-term results of classic antireflux surgery in 152 patients with Barrett's esophagus: clinical, radiologic, endoscopic, manometric, and acid reflux test analysis before and late after operation. Surgery. 1998;123:645–657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hameeteman W, Tytgat GN, Houthoff HJ, et al. Barrett's esophagus: development of dysplasia and adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology. 1989;96:1249–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Overholt B, Panjehpour M, Haydek J. Photodynamic therapy for Barrett's esophagus: follow-up in 100 patients. Gastrointest Endosc 1999;49:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ackroyd R, Brown N, Davis M, et al. Photodynamic therapy for dysplastic Barrett's esophagus: a prospective, double blind, randomized, placebo controlled trial. Gut 2000;47:612–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang K, Sampliner R. Mucosal ablation therapy of Barrett's esophagus. Mayo Clinic Proc 2001;76:433–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hofstetter W, Peters J, DeMeester T, et al. Long-term outcome of antireflux surgery in patients with Barrett's esophagus. Ann Surg. 2001;234:532–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bowers S, Mattar S, Smith C, et al. Clinical and histologic follow-up after antireflux surgery for Barrett's esophagus. J Gastrointest Surg. 2002;6:532–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cameron A. Barrett's esophagus: prevalence and size of hiatal hernia. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2054–2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eisen GM, Sandler RS, Murray S, et al. The relationship between gastroesophageal reflux disease and its complications with Barrett's esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:27–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oberg S, DeMeester TR, Peters J, et al. The extent of Barrett's esophagus depends on the status of the lower esophageal sphincter and the degree of esophageal acid exposure. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1999;117:572–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yau P, Watson D, Devitt P, et al. Laparoscopic antireflux surgery in the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux in patients with Barrett's esophagus. Arch Surg. 2000;135:801–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eubanks T, Omelanczuk P, Richards C, et al. Outcomes of laparoscopic antireflux procedures. Am J Surg. 2000;179:391–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DeMeester SR, Campos GM, DeMeester TR, et al. The impact of an antireflux procedure on intestinal metaplasia of the cardia. Ann Surg. 1998;228:547–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Starnes VA, Adkins RB, Ballinger JF, et al. Barrett's esophagus. A surgical entity. Arch Surg. 1984;119:563–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williamson WA, Ellis FH Jr, Gibb SP, et al. Effect of antireflux operation on Barrett's mucosa. Ann Thorac Surg 1990;49:537–541; discussion 541–542. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Farrell TM, Smith CD, Metreveli RE, et al. Fundoplication provides effective and durable symptom relief in patients with Barrett's esophagus. Am J Surg. 1999;178:18–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Csendes A, Burdiles P, Braghetto I, et al. Dysplasia and adenocarcinoma after classic antireflux surgery in patients with Barrett's esophagus. Ann Surg. 2002;235:178–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parrilla P, Martinez de Haro L, Ortiz A, et al. Long-term results of a randomized prospective study comparing medical and surgical treatment of Barrett's esophagus. Ann Surg. 2003;237:291–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patti M, Diener U, Tamburini A, et al. Role of esophageal function tests in diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46:597–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oelschlager B, Pellegrini C. Minimally invasive surgery for gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2001;11:341–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sampliner RE, Garewal HS, Fennerty MB, et al. Lack of impact of therapy on extent of Barrett's esophagus in 67 patients. Dig Dis Sci. 1990;35:93–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brand D, Ylvisaker J, Gelfand M, et al. Regression of columnar esophageal (Barrett's) epithelium after anti-reflux surgery. N Eng J Med. 1980;302:844–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sampliner RE. Practice guidelines on the diagnosis, surveillance, and therapy of Barrett's esophagus. The Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1028–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rudolph RE, Vaughan TL, Storer BE, et al. Effect of segment length on risk for neoplastic progression in patients with Barrett esophagus. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:612–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schnell T, Sontag S, Chejfec G, et al. Long-term Nonsurgical management of Barrett's esophagus with high grade dysplasia. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1607–1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McDonald ML, Trastek VF, Allen MS, et al. Barrett's esophagus: does an antireflux procedure reduce the need for endoscopic surveillance? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1996;111:1135–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Low DE, Levine DS, Dail DH, et al. Histological and anatomic changes in Barrett's esophagus after antireflux surgery. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:80–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]