Gastroschisis is the evisceration of the fetal intestine through a defect in the paraumbilical anterior abdominal wall with herniation of gastrointestinal structures into the amniotic cavity. Babies born with this condition are more likely to be born prematurely and to have had poor fetal growth. The anomaly requires immediate postnatal surgery, which has a good outcome in more than 90% of cases.1 It is a distressing condition for parents, however, and often requires a prolonged stay in a paediatric unit.

Ten years ago our group reported in the BMJ that the national system for notifying congenital malformations (collated by the Office for Population and Census Surveys, now called the Office for National Statistics, ONS) showed an increasing trend in the number of babies born with gastroschisis in England and Wales between 1987 and 1993.2 No such marked increase was apparent for other congenital anomalies such as exomphalos.

Gastroschisis was associated with a lower overall maternal age: the incidence among mothers aged under 20 is 4.71 per 10 000 total births compared with 0.26 per 10 000 total births to mothers aged 30-34. Furthermore, the incidence of gastroschisis was markedly higher in the northern regions of the United Kingdom (1.55 per 10 000 total births) than in the southeast (0.72 per 10 000 total births).2

The notification system is voluntary, however, and under-notification and misclassification of malformations may therefore be considerable, leading to under-ascertainment.3 This also favours over-notification of very visible anomalies such as gastroschisis while probably grossly underestimating non-visible lesions, such as heart defects. Nevertheless, even gastroschisis seems to be underestimated in ONS statistics.4,5

In contrast, regional registers for congenital anomalies aim to include all data from abortions, fetal loss, and infant deaths, as well as cross referenced information from paediatric surgical units. Such data sources have consistently shown better and more complete registration of congenital anomalies and have confirmed both an increasing incidence of gastroschisis among babies of teenage mothers and an overall increase year on year.6 This discrepancy between different register types has been well described.7 The UK's chief medical officer has expressed concern about the rising incidence of gastroschisis (L Donaldson, personal communication, July 2005) and has highlighted the importance to public health of rigorously compiled and centrally funded regional registers in providing information on congenital anomalies.8

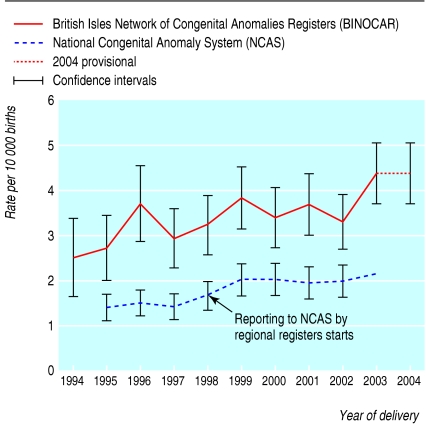

Figure 1.

Number of reported cases of gastroschisis between 1994 and 2004. Reproduced with permission from the Department of Health

Recent data from the British Isles Network of Congenital Anomaly Registers (BINOCAR) confirm the increasing incidence of gastroschisis—from 2.5 per 10 000 total births in 1994 to 4.4 per 10 000 in 2004.8,9 Among babies of women aged under 20 the incidence of gastroschisis increased from 8.9 to 24.4 per 10 000 total births. In addition, the incidence in some registers is four times as high as in others across different regional registers—for example, the Welsh register indicates an incidence of gastroschisis of 6.2 per 10 000 total births, whereas the rate in North West Thames was 1.6 per 10 000.

The observed increasing incidence of gastroschisis over time seems to be associated consistently with lower maternal age.2 Gastroschisis probably does not have a genetic cause because it occurs sporadically, with a relatively low recurrence rate. The most likely cause is early interruption of the fetal omphalo-mesenteric arterial blood supply. This may be associated with periconceptional tobacco smoking and use of recreational drugs such as alcohol, marijuana, and cocaine.10,11 The evidence for these associations is, however, only tentative and needs confirmation by carefully controlled cohort or case-control studies.12,13 Along with data from regional registers, such studies may lead the way to understanding the pathogenesis of this distressing condition and thus preventing it.

Competing interests: None declared.

News p 256

References

- 1.Sallihu HM, Emusu D, Aliyu ZY, Pierre Louis BJ, Druschel CM, Kirby RS. Mode of delivery and neonatal survival of infants with isolated gastroschisis. Obstet Gynecol 2004;104: 678-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tan KH, Kilby MD, Whittle MJ, Beattie BR, Booth IW, Botting BJ. Congenital anterior abdominal wall defects in England and Wales 1987-1993: retrospective analysis of OPCS data. BMJ 1996;313: 903-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Payne JN. Limitations of the OPCS congenital malformation notification system illustrated by examples of congenital malformations of the cardiovascular system in districts within Trent. Public Health 1992;106: 437-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clarke S, Dykes E, Chapple J, Abramsky L. Congenital wall defects in the United Kingdom: Sources had differing reporting patterns. BMJ 1999;318: 733. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kilby MD, Lander A, Tonks A, Wyldes M. Congenital wall defects in the United Kingdom: analysis should be restricted to regional data. BMJ 1999;318: 733-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kilby MD, Lander A, Tonks A, Wyldes M. West Midlands congenital anomaly register: anterior abdominal wall defects 1995-1996. Birmingham: West Midlands Perinatal Audit, 1998.

- 7.Ward Platt M. Participation in multiple neonatal research studies. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2005;90: 354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donaldson L. Gastroschisis: a growing concern. London: Department of Health, 2004. www.dh.gov.uk/assetRoot/04/11/57/82/04115782.pdf (accessed 4 Jan 2006).

- 9.Rankin J, Pattenden SW, Abramsky L, Boyd P, Jordan H, Stone D, et al. Prevalence of congenital anomalies in five British regions. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal 2005;5: F374-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.California birth defects monitoring program (1988-1990). Sacramento: Californian Department of Service, 1994.

- 11.Torfs C, Velie EM, Oeschili FW, Bateson TF, Curry CJR. A population study of gastroschisis demographic, pregnancy and life style risk factors. Teratology 1994;50: 44-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Draper ES, Rankin J, Tonks A, Field DJ, Burton PR, Abrams KR, et al. recreational drug use—a major risk factor for gastroschisis? Proceedings of the RCPCH. Arch Dis Child 2005;90(suppl II): A3. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morrison JJ, Chitty LS, Peebles D, Rodeck CH. Recreational drugs and fetal gastroschisis: maternal hair analysis in the peri-conceptional period and during pregnancy. BJOG 2005;12: 1022-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]