Abstract

Gene therapy of many genetic diseases requires permanent gene transfer into self-renewing stem cells and restriction of transgene expression to specific progenies. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-derived lentiviral vectors are very effective in transducing rare, nondividing stem cell populations (e.g., hematopoietic stem cells) without altering their long-term repopulation and differentiation capacities. We developed a strategy for transcriptional targeting of lentiviral vectors based on replacing the viral long terminal repeat (LTR) enhancer with cell lineage-specific, genomic control elements. An upstream enhancer (HS2) of the erythroid-specific GATA-1 gene was used to replace most of the U3 region of the LTR, immediately upstream of the HIV type 1 (HIV-1) promoter. The modified LTR was used to drive the expression of a reporter gene (the green fluorescent protein [GFP] gene), while a second gene (a truncated form of the p75 nerve growth factor receptor [ΔLNGFR]) was placed under the control of an internal constitutive promoter to monitor cell transduction, or to immunoselect transduced cells, independently from the expression of the targeted promoter. The transcriptionally targeted vectors were used to transduce cell lines, human CD34+ hematopoietic stem-progenitor cells, and murine bone marrow (BM)-repopulating stem cells. Gene expression was analyzed in the stem cell progeny in vitro and in vivo after xenotransplantation into nonobese diabetic-SCID mice or BM transplantation in coisogenic mice. The modified LTR directed high levels of transgene expression specifically in mature erythroblasts, in a TAT-independent fashion and with no alteration in titer, infectivity, and genomic stability of the lentiviral vector. Expression from the modified LTR was higher, better restricted, and showed less position-effect variegation than that obtained by the same combination of enhancer-promoter elements placed in a conventional, internal position. Cloning of the woodchuck hepatitis virus posttranscriptional regulatory element at a defined position in the targeted vector allowed selective accumulation of the genomic transcripts with respect to the internal RNA transcript, with no loss of cell-type restriction. A critical advantage of this targeting strategy is the use of a spliced, major viral transcript to express a therapeutic gene and that of an internal, independently regulated promoter to express an additional gene for either cell marking or in vivo selection purposes.

Retroviral vectors provide a safe and relatively efficient gene transfer system for many gene therapy applications (reviewed in references 5, 17, and 27). These vectors are still the only available tool to achieve stable genomic integration of a therapeutic gene, and they are therefore largely used in clinical trials for gene therapy of genetic diseases. A significant limitation of retroviral vectors derived from the Moloney murine leukemia virus (Mo-MLV) backbone is their inability to integrate into the genome of nondividing cells, which essentially limits their use to ex vivo applications and to cells which can be induced to replicate in culture without losing a specific, therapeutically relevant phenotype. As an example, hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are very difficult to maintain in culture in an active mitotic state without compromising their self-renewing and bone marrow (BM)-repopulating capacity and are therefore difficult to transduce with retroviral vectors at an efficiency compatible with clinical applications. A number of groups have recently reported that human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-derived lentiviral vectors can integrate into the genome of nondividing cells in vivo and ex vivo (reviewed in references 24 and 28) and are much more efficient than Mo-MLV-derived vectors in transducing HSCs without compromising their repopulation capacity upon transplantation (10, 15, 29). Several years of research have drastically improved both design and packaging of lentiviral vectors and have virtually abolished the safety concerns originally raised by the idea of transducing human cells with a vector derived from HIV (6, 31, 32).

Correction of genetic disorders affecting a specific progeny of HSCs (e.g., hemoglobinopathies or thalassemias) requires restricting expression of the therapeutic gene in a cell lineage-specific fashion. In these cases, transcriptional targeting of the transferred gene is mandatory. Appropriate transgene regulation in the framework of a retroviral vector is a difficult task, due to a number of technical factors such as limited vector capacity, transcriptional interference between the viral long terminal repeat (LTR) and internal enhancers-promoters, and genetic instability of complex regulatory sequences (e.g., locus control regions) in this context (4). We had previously proposed a transcriptional targeting strategy for Mo-MLV-derived retroviral vectors, consisting of the addition of tissue- or lineage-specific regulatory elements into the LTR, thereby overcoming some of the problems associated with the use of internal transcriptional units (9, 11). Transcriptional targeting of lentiviral vectors has been attempted by placing the gene of interest under the control of restricted internal promoters (16) in the framework of self-inactivating (SIN) vectors, in which the LTR is disabled by deletion of the U3 region (enhancer and promoter) for safety reasons (31). Modification of the HIV LTR could theoretically be accomplished by the same strategy used for the Mo-MLV LTR, although the presence of a TAT-dependent promoter and a TAT-responsive element (TAR) in the primary transcript might add complexity to the vector design.

We attempted the development of transcriptionally targeted lentiviral vectors by replacing the viral LTR U3 enhancer elements with a DNase hypersensitive region (HS2) upstream of the erythroid-specific, GATA-1 zinc finger transcription factor gene (8, 25). This element contains an autoregulatory enhancer able to restrict transcription of a heterologous promoter to human or murine erythroblastic cell lines (18, 26) and to confer erythroid lineage specificity to a Mo-MLV-derived vector upon transduction of human and murine HSCs (11). The LTR modification was introduced in lentiviral vectors encoding the green fluorescence protein (GFP) as reporter gene within the major genomic transcript. A second gene, the cDNA for a truncated form of the p75 nerve growth factor receptor (ΔLNGFR) (21), was placed under the control of an internal, constitutive phosphoglycerokinase (PGK) promoter to monitor cell transduction and immunoselect transduced cells, independently from the expression of the targeted promoter. The vectors contained a central polypurine tract (cPPT), to enhance transduction of nondividing cells (10), and the woodchuck hepatitis virus posttranscriptional regulatory element (WPRE) (30) to increase the expression of the targeted transgene. The vectors were used to transduce hematopoietic cell lines and human and murine HSCs, and transgene expression was analyzed in the differentiated progenies in vitro and in vivo. The transcriptionally targeted HIV LTR directed high levels of transgene expression specifically in mature erythroblasts, in a TAT-independent fashion and with no alteration in titer, infectivity, and genomic stability of the lentiviral vector. Expression from the targeted LTR was higher, better restricted, and showed less position-effect variegation than that obtained with the same combination of enhancer-promoter elements placed in the conventional, internal position. Insertion of the WPRE upstream of the internal promoter allowed selective accumulation of the genomic transcripts with respect to the internal RNA transcript, with no loss of cell-type restriction. These data indicate that enhancer replacement is an effective strategy to achieve efficient and targeted expression of a transgene carried by a lentiviral vector while maintaining an independently regulated, second transcriptional unit to express additional gene functions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids.

An EcoRI/SacI fragment containing part of the 3′ LTR of the HIV-1-derived lentiviral vector pHR2 (6) was subcloned into the PvuII site of the pUC-19 plasmid. The plasmid was digested with EcoRV and BanII, self-ligated to generate a −418 to −40 deletion (where +1 is the transcription start site) in the U3 region of the LTR, or ligated with a 200-bp BamHI fragment containing the GATA-1 HS2 human genomic fragment (−856 to −655) (18, 26) to obtain a chimerical LTR. The two LTRs were then introduced in the pRRL.SIN vector backbone (31) to obtain the pRRL.sin-40.GFP (−40) and the pRRL.GATA.GFP (G) vectors, respectively. A second, independent transcriptional cassette (PGK.ΔLNGFR) was introduced into the HindII/SacII sites to generate the vectors pRRL.sin-40.GFP.PGK.ΔN (−40/P) and pRRL.GATA.GFP.PGK.ΔN (G/P). The WPRE (30) was cloned in the filled EcoRI or HindII sites of the G/P vector to generate the pRRL.GATA.GFP.W.PGK.ΔN. (G.W/P) or pRRL.GATA.GFP.PGK. ΔN.W (G/P.W) vectors, respectively. To generate the pRRL.sin-18.GATA.GFP (−18/G) vector, a fragment of 370 bp containing the GATA-1 HS2 and a portion of the HIV-1 LTR (−40 to +75) was inserted in the filled BamHI site of the pRRL.GFP.sin-18 vector. For some experiments, the G.W/P vector was further modified by the insertion of a 118-bp HpaII/ClaI fragment containing the HIV-1 cPPT, as previously described (10).

Vector production.

Viral stocks pseudotyped with the vesicular stomatitis G protein (VSV-G) were prepared by transient cotransfection of 293T cells using a three-plasmid system (the transfer vector, the pCMVΔR8.74 encoding Gag, Pol, Tat, and Rev, and the pMD.G plasmid encoding VSV-G), as previously described (6). In some cases, viral preparations were concentrated by ultracentrifugation to increase titer. The viral p24 antigen concentration was determined by using an HIV-1 p24 Core Profile enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (NEN Life Science Products). Viral titers (infectious particles) were determined by transduction of HeLa or HEL cells with serial dilution of the vector stocks. Transduction efficiency was evaluated by scoring GFP and/or ΔLNGFR transgene expression by flow cytometry (FACScan; Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, Calif.).

Transduction of stable cell lines.

HeLa cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (EuroClone), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone), and transduced in six-well plates as described previously (6). Human erythroleukemic (HEL), myeloblastic (K562), and monocytic (U937) cell lines (all from American Type Culture Collection [ATCC], Rockville, Md.) were grown in RPMI 1640 (EuroClone) supplemented with 10% FBS and transduced with viral supernatant at different multiplicities of infection (MOIs) in the presence of 4 μg of Polybrene/ml. On day 4 after transduction, cells were harvested and analyzed by flow cytometry for transgene expression.

Transduction and maintenance of human HSCs.

Human CD34+ stem-progenitor cells were purified from the Ficoll mononuclear cell fraction of umbilical cord blood by positive selection using the CD34 magnetic cell isolation kit (MiniMACS; Milthenyi, Auburn, Calif.). CD34+ cells were infected with viral stocks at an MOI of 50 to 200 in serum-free Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (IMDM; BioWhittaker, Verviers, Belgium) containing BIT serum substitute (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada), 20 ng of recombinant human interleukin-6 (rhIL-6) per ml (R&D Systems), 20 ng of thrombopoietin/ml (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, N.Y.), 100 ng of stem cell factor (rhSCF) per ml (R&D Systems), and 100 ng of Flt3-L/ml (PeproTech) for 24 h. Transduced CD34+ cells were washed in IMDM with 10% FBS (EuroClone), plated at a density of 1,000 cells/ml in methylcellulose medium (1% methylcellulose [Stem Cell Technologies], 30% FBS, 2 mM l-glutamine, 10−4 M β-mercaptoethanol, 1% bovine serum albumin in IMDM) containing 4 U of erythropoietin per ml (EPREX), 10 ng of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor per ml, 10 ng of rhIL-3 (R&D Systems) per ml, and 50 ng of rhSCF/ml, and scored by light and fluorescence microscopy 10 to 14 days after plating. Alternatively, transduced CD34+ cells were grown in liquid culture under three different conditions: (i) in the same medium used for transduction to maintain an undifferentiated phenotype; (ii) in X-VIVO-10 (BioWhittaker) serum-free medium supplemented with 20 ng of rhSCF per ml and 4 U of recombinant human erythropoietin per ml to induce erythroid differentiation; and (iii) in IMDM supplemented with 20% FBS, 20 ng of both rhIL-3 and rhIL-6 per ml to induce myeloid differentiation. Cell phenotypes and transduction levels were determined by flow cytometry.

Transplantation in NOD-SCID mice.

A breeding colony of nonobese diabetic (NOD)-SCID mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine) was housed in a positive-airflow ventilated rack and bred and maintained in microisolators under specific-pathogen-free conditions. Mice to be transplanted were sublethally irradiated at 6 to 8 weeks of age with 350 cGy of total body irradiation from a cesium source. Transduced human CD34+ cells (1.5 × 105 to 3 × 105) were administered within 24 h of irradiation in a single intravenous (tail vein) injection. Mouse BM was analyzed by flow cytometry 5 to 11 weeks posttransplant. BM cells were plated at a density of 0.5 × 105 to 2 × 105 cells/ml in methylcellulose preparation preferentially supporting the growth of human colonies (1).

Transduction of murine BM cells and BM transplantation.

Murine BM cells were harvested from C57BL/6 mice (Charles River) by flushing femurs and tibiae and infected for 24 h with viral stocks at an MOI of 200 in serum-free IMDM containing BIT serum substitute and 50 ng of mouse SCF (muSCF)/ml, 10 ng of muIL-3/ml, 10 ng of human Flt3-L (huFlt3-L)/ml, and 20 ng of huIL-6/ml. Transduced cells were injected (5 × 106 cells/mouse) into the tail vein of recipient 8- to 12-week-old male C57Bl/6-Ly-5.1 mice (B/6.SJL-CD45a-Pep3b; Jackson Laboratories) and irradiated with two split doses of 400 cGy 4 h apart. Nine to 11 weeks after BM transplantation, animals were sacrificed and hematopoietic tissues were collected for fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis and clonogenic assay.

Flow cytometry analysis.

ΔLNGFR expression in transduced cells was monitored by flow cytometry or epifluorescence microscopy using an indirect staining with the anti-human p75-NGFR monoclonal antibody (MAb) 20.4 (ATCC) and R-phycoerythrin (RPE)-conjugated goat anti-mouse serum (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, Ala.). Human cell surface phenotype and human cell engraftment in transplanted NOD-SCID mice were determined by flow cytometry using RPE-conjugated anti-human CD45 (DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) to detect total human leukocytes, CD34 (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, Calif.) for stem-progenitor cells, CD19 (DAKO) for B lymphocytes, CD14 (DAKO) for monocytes, CD13 (Caltag Laboratories, Burlingame, Calif.) for myeloid cells, and GpA (DAKO) for erythrocytes. Indirect staining with biotinylated anti-p75-NGFR MAb and Tricolor-conjugated streptavidin (Caltag Laboratories) was used to monitor transduction efficiency in each BM cell subpopulation. Mouse cell phenotyping was carried out using PE-conjugated anti-mouse TER-119 and Gr-1 (PharMingen) antibodies. The fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-mouse CD45.2 MAb (PharMingen) was used to evaluate donor-host chimerism in BM-transplanted mice. Isotype-matched nonspecific antibodies were used as controls (Becton Dickinson). For cytofluorometry analysis of nonerythroblastic cell populations, BM cells were lysed with 8.3% ammonium chloride to remove erythroid cells and washed with phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin and 0.01% sodium azide. Cells were then resuspended at 1 × 106 to 2 × 106 cells/ml and incubated with mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) and 5% human serum to block nonspecific binding to the Fc receptor.

Southern and Northern blot analyses.

Genomic DNA was isolated by lysis with TNE (10 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 100 mM NaCl, 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate), proteinase K treatment, phenol-chloroform extraction, and ethanol precipitation. Ten micrograms of DNA was digested overnight with AflII and EcoRI, run on a 0.8% agarose gel, transferred to a nylon membrane (Hybond-N; Amersham) by Southern capillary transfer, probed with 2 × 107 dpm of a 32P-labeled GFP probe, and exposed to X-ray film. Total cellular RNA was extracted by guanidine-isothiocyanate, poly(A)+-selected by oligo(dT)-cellulose chromatography, size-fractionated on 1% agarose-formaldehyde gel, blotted onto nylon membranes, hybridized to 107 dpm of 32P-labeled NGFR, GFP, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) probes, and exposed to X-ray film (22).

RESULTS

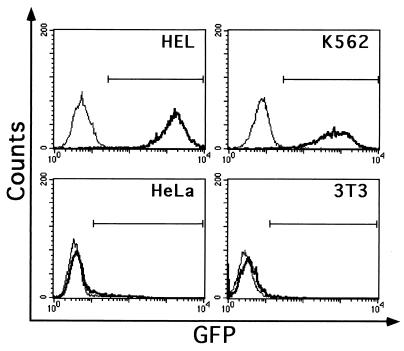

Replacement of the U3 enhancer of the HIV LTR with the GATA-1 HS2 element restricts lentiviral gene expression to erythroblastic cell lines. To restrict lentiviral transgene expression to a specific cell context, we developed a transcriptional targeting strategy based on replacing the U3 enhancer of the HIV LTR with cell-specific, genomic transcriptional control elements. The U3 region of the 3′ LTR of the pHR2 lentiviral vector (6), from position −418 to −40 with respect to the transcription start site, was removed and replaced by a 200-bp human genomic fragment containing an autoregulatory enhancer of the GATA-1 erythroid-specific transcription factor gene (GATA-1 HS2) (18, 26). The −40-deleted LTR and the GATA-1/HIV-1 chimerical LTR (GATA-LTR) were used to replace the 3′ LTR of the pRRL.SIN vector carrying GFP as a reporter gene (31). The resulting vectors, pRRL.sin-40.GFP (−40) and pRRL.GATA.GFP (G), were pseudotyped with VSV-G by a second-generation lentiviral packaging system (6) and preliminarily tested for their transcriptional properties by transducing bulk cultures of human and murine stable cell lines (MOI, 10). FACS analysis of GFP expression in transduced human erythroblastic (K562 and HEL) and nonhematopoietic (HeLa) cell lines and murine fibroblastic (NIH 3T3) cells showed no expression from the −40 vector, and expression was restricted to the HEL and K562 cells from the targeted G vector (Fig. 1). These data showed that the enhancerless HIV-1 LTR is virtually inactive in the absence of TAT, as previously reported for two similar U3 deletions (−45 and −36) in the context of lentiviral SIN vectors (31). Transcriptional activity is restored by the insertion of the GATA-1 HS2 enhancer, but it is restricted to the GATA-1-expressing K562 and HEL cells.

FIG. 1.

Analysis of GFP expression in cell lines transduced with the G lentiviral vector, carrying a GFP gene under the control of the GATA-1 HS2-modified LTR (see Fig. 2A), and with a control −40 vector, carrying a GFP gene under the control of an enhancerless LTR. Human erythroblastic HEL and K562 cells, nonhematopoietic HeLa cells, and murine fibroblastic NIH 3T3 cells were infected at an MOI of 10, grown as bulk cultures, and analyzed for GFP expression by single-channel cytofluorimetry (x axis). Expression profiles are indicated by a thin (−40 vector) or a bold (G vector) line, respectively.

A modified LTR is more efficient than an internal promoter to drive transgene expression in the context of a lentiviral vector.

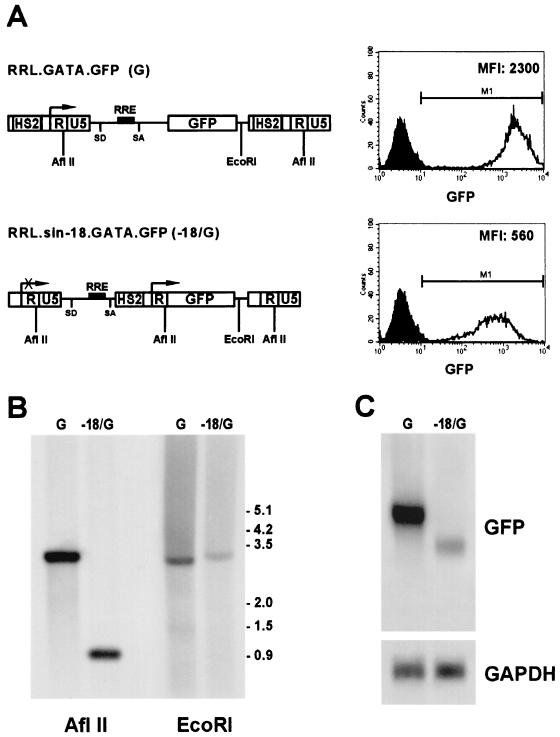

Retargeting the specificity of the LTR promoter allowed us to exploit the efficiency of the viral machinery in directing gene expression from the spliced, major genomic transcript rather than from an intronless, internal transcriptional unit. In order to test the advantage of this design, we compared the activity of the G vector with that of an RRL.sin-18.GATA.GFP (−18/G) vector containing the same combination of enhancer-promoter in the conventional internal position in the context of a SIN vector (Fig. 2A, left panel). HEL cells were transduced with the G and −18/G vectors at the same MOI (10), maintained in culture as bulk populations, and monitored for GFP expression by FACS analysis every 2 weeks for 2 months. Transduction efficiency was very similar for both vectors (virtually 100%), but GFP expression was fourfold higher in cells transduced with the G vector than in those transduced with the −18/G vector (mean fluorescence intensity [MFI], 2,300 versus 560; Fig. 2A, right panel). Southern blot analysis of DNA restricted with AflII showed that transduced cells harbored stably integrated vectors with intact recombinant LTRs at a comparable vector copy number (Fig. 2B). Restriction with EcoRI indicated essentially random integration in both cell populations, although a distinct band of unknown origin appeared over the hybridization smear in both cases (Fig. 2B). This does not reflect oligoclonality of the bulk populations, as demonstrated by subsequent analysis of individual clones (see below). Northern blot analysis showed that genomic transcripts from the G vector were accumulated in HEL cells at a level fivefold higher than that of the subgenomic transcript from the −18/G vector, as quantitated by phosphorimaging after normalization for GAPDH mRNA content (Fig. 2C). GFP expression, number of vector copies, and level of vector-derived transcripts were also analyzed in single cell clones derived from the transduced bulk cultures. Cells were cloned at 0.2 to 0.3 cells/well, and single clones were isolated after 2 weeks of culture and grown up to 2 months for further analysis. Overall, GFP expression levels were consistently higher in clones transduced with the G vector than in those transduced with the −18/G vector, as analyzed by Southern blotting of each individual clone and normalization for the vector copy number (data not shown). In both groups of clones, Southern blot analysis showed no evidence of common or preferential sites of proviral integration. Interestingly, GFP expression levels varied considerably among clones transduced with the −18/G vector (MFI, 63 to 407) and correlated with the number of integrated proviruses (2 to 9), while in clones transduced with the G vector GFP levels were uniformly higher (MFI, 852 to 1,275) and essentially independent from the vector copy number (4 to 18). Furthermore, 2 out of 18 HEL clones transduced with the −18/G vector lost transgene expression during prolonged culture, while all 16 clones transduced with the G vector showed sustained transgene expression throughout the 2 months. These results indicate that a lentiviral vector carrying a modified LTR directs higher levels of targeted gene expression at low vector copy number than a vector containing the same enhancer-promoter combination in an internal position, and that its expression could be less subjected to position-effect variegation in the target cell genome.

FIG. 2.

(A, Left) Schematic maps of the RRL.GATA.GFP (G) and the RRL.sin-18.GATA.GFP (−18/G) vectors in their proviral forms. HS2 indicates the GATA-1 HS2 autoregulatory enhancer replacing the HIV LTR U3 region in the G vector. An arrow indicates the transcription start site of the chimerical LTR promoter. A crossed arrow indicates the disabled LTR promoter in the −18/G vector. SD, splice donor; SA, splice acceptor; RRE, REV responsive element. Restriction sites used for the Southern analysis shown in panel B are indicated. (Right) Single-channel flow cytometry of GFP expression in HEL cells transduced with the G (upper panel) or −18/G (lower panel) vectors at an MOI of 10, as analyzed 4 weeks after transduction. Distributions of transduced and control, untransduced cells are indicated by white and black peaks, respectively. MFI of GFP expression is in arbitrary units. (B) Southern blot analysis of genomic DNA extracted from HEL cell lines transduced with the G or −18/G vector, digested with AflII or EcoRI, and hybridized to a GFP probe. Molecular size markers are reported in kb. (C) Northern blot analysis of poly(A)+ RNA extracted from HEL cells transduced with the G or −18/G vector and hybridized with GFP (upper panel) and GAPDH (lower panel) probes.

LTR modification allows expression of two independently regulated transcriptional units.

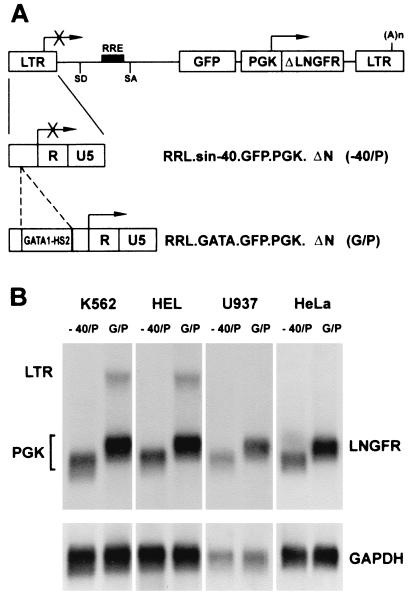

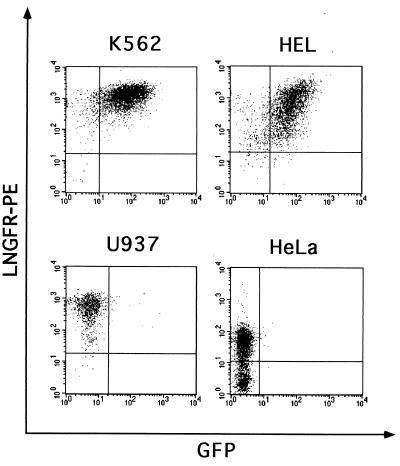

In order to monitor cell transduction and immunoselect transduced cells independently from the transcriptional activity of the targeted LTR, the ΔLNGFR cDNA was cloned downstream from the GFP gene in both vectors as a second reporter gene, under the control of a constitutive PGK promoter. The resulting vectors, RRL.sin-40.GFP.PGK.ΔN (−40/P) and RRL.GATA.GFP.PGK.ΔN (G/P) (Fig. 3A), were packaged at titers ranging from 5 × 106 to 5 × 107 transducing units/ml, as determined by infection of HeLa cells with serial dilutions of viral supernatants and FACS analysis of ΔLNGFR expression. To study the expression characteristics of the two transcriptional units, human myeloblastic (Kasumi-1), myelomonocytic (U937), erythroblastic (K562 and HEL), and nonhematopoietic (HeLa) cell lines and murine erythroblastic (MEL) and fibroblastic (NIH 3T3) cell lines were infected by −40/P and G/P vectors (MOI, 5 to 10) and grown as bulk cultures. Transduction efficiency ranged between 67 and 96%, depending on the cell line, as analyzed by FACS analysis of LNGFR expression. Southern blot analysis of genomic DNA showed stable integration of intact proviruses and the polyclonal nature of all tested cell populations (data not shown). Expression of vector-derived transcripts was analyzed by Northern blotting of poly(A)+ RNA and hybridization to a ΔLNGFR-specific probe. As expected, accumulation of LTR-driven transcripts was never detected in cells transduced with the −40/P vector (Fig. 3B). In cells transduced with the G/P vector, transcripts derived from the GATA-LTR were detected in K562, HEL (Fig. 3B), and MEL (data not shown) cells, but not in U937, HeLa (Fig. 3B), Kasumi-1, and NIH 3T3 (data not shown) cells. Subgenomic transcripts derived from the internal PGK promoter were present in all cell lines transduced with both vectors (Fig. 3B and data not shown). At the protein level, expression of both GFP and ΔLNGFR was quantitatively analyzed by double-fluorescence flow cytometry after staining with a PE-conjugated anti-LNGFR antibody (Fig. 4). Expression of ΔLNGFR from the internal PGK promoter was observed in all transduced cell lines, while expression of GFP from the GATA-LTR was detected only in erythroblastic cells (HEL and K562; Fig. 4). The two reporter genes were coexpressed in >90% of transduced erythroblastic cells. These data indicate that the use of a modified LTR and an internal promoter allows the expression of two independently regulated genes in the context of a lentiviral vector.

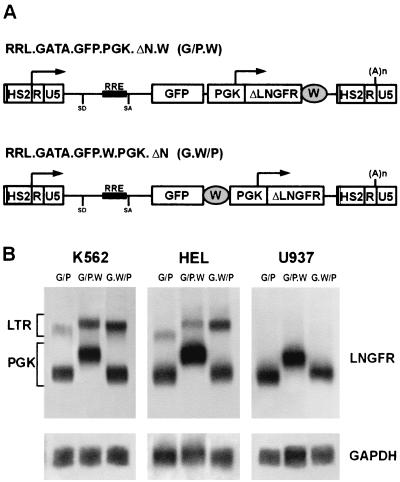

FIG. 3.

(A) Schematic map of the RRL.sin-40.GFP.PGK.ΔN (−40/P) and the RRL.GATA.GFP.PGK.ΔN (G/P) lentiviral vectors. In the −40/P vector, the LTR carries a −418 to −40 deletion removing the U3 enhancer, while in the G/P vector the same region is replaced by the GATA-1 HS2 autoregulatory enhancer. The arrows indicate the transcription start sites of the LTR or the internal PGK promoter. SD, splice donor; SA, splice acceptor; RRE, REV responsive element; (A)n, polyadenylation site. (B) Northern blot analysis of poly(A)+ RNA extracted from K562, HEL (erythroblastic), U937 (myelomonocytic), and HeLa (nonhematopoietic) cell lines transduced with the −40/P or the G/P vector and hybridized with GFP (upper panel) and GAPDH (lower panel) probes. Transcripts originating from the viral LTR or the internal PGK promoter are indicated on the left.

FIG. 4.

Double-immunofluorescence FACS analysis of GFP (x axis) and ΔLNGFR expression (y axis) in K562, HEL, U937, and HeLa cells transduced with the G/P vector (Fig. 3) at an MOI of 10. Cells were grown as bulk culture and analyzed 3 days after infection after staining with a PE-conjugated anti-LNGFR antibody.

Targeted gene expression is selectively enhanced by specific positioning of a WPRE.

Northern blot analysis showed that transcripts from the modified LTR, although restricted, were accumulated at a low level in K562 and HEL cells transduced with the double-expression cassette G/P vector compared to cells transduced with the single-cassette vector G (compare Fig. 3 and 2C), suggesting a negative interference of the internal promoter upon transcription of the GATA-LTR. In order to improve the level of LTR-driven transcripts in a selective fashion, we cloned a 500-bp WPRE at alternative positions in the G/P vector, downstream of the GFP gene (Fig. 5A, G.W/P vector) or the ΔLNGFR gene (Fig. 5A, G/P.W vector). As a result, the WPRE was contained exclusively in the LTR-driven, viral genomic transcript in the G.W/P vector or in both the genomic and the subgenomic PGK-driven transcripts in the G/P.W vector. Viral stocks derived from these vectors were used to transduce HEL, K562, and U937 cell lines (MOI, 10). In K562 and HEL cells transduced with the G/P.W vector, the level of both the LTR- and the PGK-driven transcripts was approximately twofold higher than that in cells transduced with the G/P vector, as quantitated by phosphorimaging of Northern blots of poly(A)+ RNA extracted from bulk cultures (Fig. 5B, lane G/P.W versus G/P). Conversely, in cells transduced with the G.W/P vector the level of the LTR-driven genomic transcripts was selectively increased (about fourfold) with respect to cells transduced with the G/P vector, while the level of the PGK-driven, subgenomic transcripts remained essentially unchanged (Fig. 5B, lane G.W/P versus G/P). Interestingly, addition of the WPRE in either configuration did not rescue accumulation of genomic transcripts in nonerythroid cells (Fig. 5B, U937) and had therefore no effect on the transcriptional targeting of the GATA-LTR. Protein expression data paralleled the results obtained at the RNA accumulation level. PGK-driven, ΔLNGFR expression increased slightly in both HEL and K562 cells transduced with the G/P.W vector compared to cells transduced with the G/P and the G.W/P vectors (MFI in HEL cells, 1,336 versus 759 and 1,051, respectively; MFI in K562 cells, 1,345 versus 1,010 and 1,116, respectively, in a representative experiment). Conversely, GFP expression increased three- to fivefold in HEL and K562 cells transduced with the G/P.W vector compared to cells transduced with G/P and G.W/P (MFI in HEL cells, 345 versus 78 and 72, respectively; MFI in K562 cells, 260 versus 68 and 107, respectively). Transduced U937 cells never showed expression of GFP, while ΔLNGFR levels increased slightly in cells transduced with G/P.W (MFI, 422) with respect to cells transduced with G/P or G.W/P (MFI, 318 and 303, respectively). These results demonstrate that the presence of WPRE within a transcript selectively enhances its accumulation in transduced cells, thus allowing us to differentially modulate the expression levels of two different genes carried by the same lentiviral vector. The G.W/P vector was therefore chosen to evaluate transcriptional targeting of the GATA-LTR in human primary HSCs

FIG. 5.

(A) Schematic maps of the RRL.GATA.GFP.PGK.ΔN.W (G/P.W) and RRL.GATA.GFP.W.PGK.ΔN (G.W/P) vectors in their proviral forms. See Fig. 3 for abbreviations. The WPRE (W) is inserted at alternative positions in the vectors, both derived from the G/P vector described in the legened to Fig. 3. (B) Northern blot analysis of poly(A)+ RNA extracted from K562, HEL, and U937 cells transduced with the G/P, G/P.W, or G.W/P vectors and hybridized to LNGFR (upper panels) or GAPDH (lower panels) probes. Transcripts originating from the viral LTR or the internal PGK promoter are indicated on the left.

Expression of the GATA-LTR is restricted to the erythroblastic progeny of human HSCs.

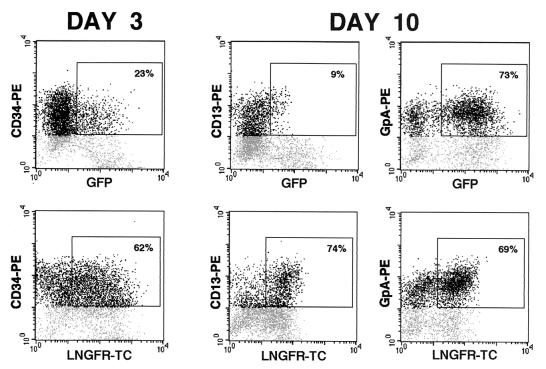

Human cord blood-derived CD34+ stem-progenitor cells were cultured for 24 h in serum-free medium supplemented with cytokines (SCF, Flt-3L, IL-6, IL-3) and transduced with the G.W/P vector at an MOI of 50 to 100. Three days after infection, cells were analyzed by flow cytometry for CD34, LNGFR, and GFP expression. More than 60% of CD34+ cells were transduced, as measured by the expression of LNGFR driven by the internal PGK promoter, while only 23% of them expressed GFP from the GATA-LTR (Fig. 6, left panels). To test the activity of the GATA-LTR in differentiated cells, transduced CD34+ progenitors were induced to differentiate in liquid culture into either myeloid or erythroid lineages. Ten days after induction, expression of GFP and LNGFR was evaluated by triple-immunofluorescence FACS analysis of cells stained with antibodies against either erythroid (GpA) or myeloid (CD13) lineage-specific surface markers. The proportion of GpA+ cells expressing LNGFR and GFP was comparable (69 and 73%, respectively), indicating that the GATA-LTR was active in virtually all transduced erythroid cells (Fig. 6, right panels). Conversely, GFP expression was barely detectable in a small fraction (9%) of the CD13+ myeloid cells transduced at a level of 74% (Fig. 6, middle panels). Under both differentiation conditions, a fraction of GFP+ cells stained negative for both GpA and CD13, indicating the presence of a residual, immature subpopulation derived from CD34+ cells and maintaining GATA-LTR activity. At a quantitative level, LNGFR expression was higher in undifferentiated (CD34+) progenitors than in differentiated (GpA+ and CD13+) progeny (MFI, 174, 58, and 68, respectively), whereas GFP expression increased fivefold in the GpA+ progeny of CD34+ cells (MFI, 52 to 255), showing that expression from the GATA-LTR increases with erythroid cell differentiation and suggesting that in an appropriate cell context the activity of a targeted LTR is higher than that of a constitutive internal promoter.

FIG. 6.

Expression of GFP (upper panels) and ΔLNGFR (lower panels) in liquid culture of human CD34+ hematopoietic stem-progenitor cells transduced with the G.W/P vector (Fig. 5) and analyzed 3 days after infection (left panels) or 10 days after induction of myelomonocytic or erythroblastic differentiation (center and right panels). Cells were analyzed by triple-immunofluorescence flow cytometry after staining with a TC-conjugated anti-LNGFR antibody and PE-conjugated antibodies against specific surface markers for undifferentiated progenitors (CD34, right panels) or myeloid (CD13, center panels) and erythroid (GpA, right panels) progeny. Values in the gated areas indicate the percentage of cells double positive for each surface marker and either GFP (upper panels) or ΔLNGFR (lower panels) expression.

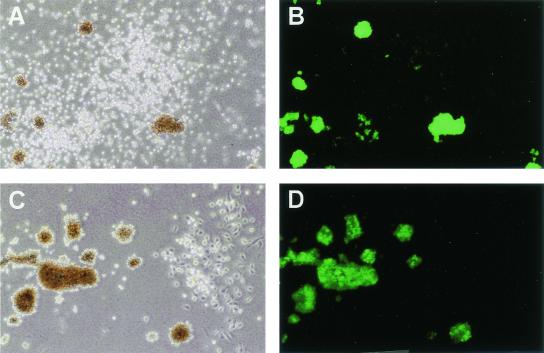

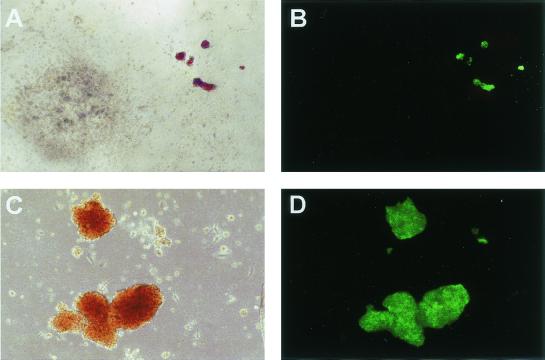

To analyze transgene expression at the level of single colonies, CD34+ cells were transduced with the G.W/P vector, immunoselected for ΔLNGFR expression by immunomagnetic cell sorting, and directly scored for GFP expression by fluorescence microscopy in methylcellulose clonal cultures. The introduction of the immunoselection step allowed us to analyze GATA-LTR-driven gene expression only in cells differentiating from transduced progenitors. Colonies were morphologically scored as erythroid-burst forming units (BFU-E), granulocyte-macrophage-colony forming units (CFU-GM), or granulocyte-erythroid-macrophage-megakaryocyte-colony forming units (CFU-GEMM) between 10 and 14 days from plating, and no difference in colony-forming efficiency was found in control, mock-transduced cells versus G.W/P-transduced and immunoselected cells. In the representative experiment shown in Fig. 7, most BFU-E colonies (54 out of 57) scored strongly positive for GFP by fluorescence microscopy, while only rare CFU-GM colonies (2 out of 49) appeared weakly positive by the same assay.

FIG. 7.

Erythroid-specific expression of GFP in methylcellulose colonies derived from CD34+ human hematopoietic progenitors transduced with the G.W/P lentiviral vector (Fig. 5) and immunoselected for ΔLNGFR expression before plating. (A and C) Bright-field view of fully mature BFU-E and CFU-GM colonies 14 days after plating. (B and D) Green fluorescence view of the same fields (GFP-specific filters). Magnification, ×10.

Overall, these results show that transcription from the GATA-LTR is active at low levels in a fraction of the CD34+ hematopoietic progenitors, strongly down-regulated during myelomonocytic differentiation, and activated and maintained at high levels in cells undergoing erythroid differentiation.

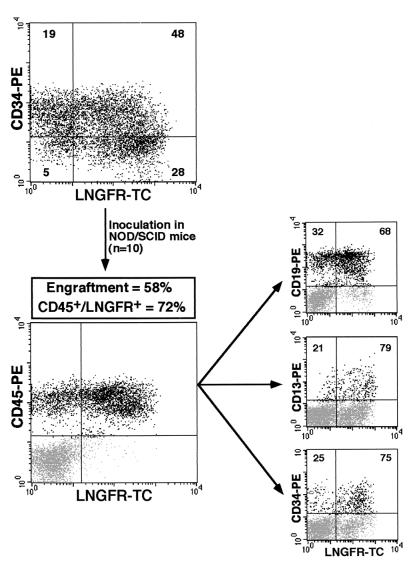

Expression of the GATA-LTR is restricted to the erythroid progeny of human SRCs.

The lineage-specific expression of the GATA-LTR was tested in human hematopoietic stem-progenitor cells in vivo in the NOD-SCID mouse model. Cord blood CD34+ cells were transduced with the G.W/P vector, further modified by the addition of the HIV-1 cPPT sequence, which was recently reported as essential for high efficiency of gene transfer into SCID-repopulating cells (SRCs) (10). A total of 10 mice in three different experiments were sublethally irradiated, inoculated with 1.5 × 105 to 3 × 105 CD34+ cells transduced at different MOIs (100 or 200), and sacrificed 5 to 11 weeks after transplantation. Transduction efficiency of CD34+ cells ranged from 49 to 76%, as assayed by ΔLNGFR expression 4 days after infection (Table 1). Engraftment of human cells ranged from 1.5 to 58%, as indicated by the proportion of human CD45+ cells in the mouse BM. Gene transfer efficiency in engrafted human cells ranged from 35 to 72%, as assayed by ΔLNGFR expression (Table 1). A representative analysis of the BM of a NOD-SCID mouse that received a transplantation dose of 3 × 105 CD34+ cells transduced at a proportion of 76% is shown in Fig. 8. Here, 58% of the BM cells were of human origin (CD45+) and 72% of human CD45+ cells expressed ΔLNGFR. Further staining with antibodies against the lineage markers CD19, CD13, and CD34 showed the presence of human lymphoid, myeloid, and undifferentiated progenitor cells. LNGFR+ cells were found in similar percentages in all tested lineages (Fig. 8). GFP expression was detectable in <1% of human cells recovered from BM of all but one of the 10 analyzed mice. In a single mouse (mouse number 1.3 in Table 1), GFP expression was detected in 33, 40, and 36% of transduced CD45+, CD34+, and CD19+ cells, respectively (data not shown), suggesting the presence in this animal of a high proportion of immature GATA-1-expressing multilineage and lymphoid progenitors. Since human erythroid differentiation occurs at a very low level in vivo in the NOD-SCID model (data not shown), expression of the GATA-LTR in the erythroblastic progeny of transduced SRCs was analyzed by plating BM cells from transplanted and control NOD-SCID mice in clonal cultures under conditions that preferentially support outgrowth of human progenitors (1). At 11 to 14 days after plating, single colonies were counted and GFP+ colonies were scored under an inverted fluorescence microscope. Overall, 70 out of 119 BFU-E colonies were GFP+ (average, 59%), while 0 out of a total of 232 CFU-GM colonies showed detectable GFP expression (Table 1). Figure 9A to D shows GFP expression in fully differentiated human erythroid colonies grown from the BM of a transplanted NOD-SCID mouse. Murine colonies derived from control, mock-transplanted NOD-SCID mice were few, GFP−, and morphologically distinguishable from human colonies obtained from transplanted animals.

TABLE 1.

Transduction of SRCs with the G.W/P vectora

| Group | Mouse | Wk after transplantation | MOI | TE FACS (%) | Cell dose (105) | Human cell engraftment (% CD45+) | LNGFR+ human cells (%) | GFP+ BFU-E colonies (%)b | GFP+ CFU-GM colonies (%)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 1.1 | 5 | 200 | 76 | 3 | 2.5 | 62 | ND | ND |

| 1.2 | 5 | 200 | 76 | 3 | 3 | 63 | 61 (8/13) | 0 (0/21) | |

| 1.3 | 9 | 200 | 76 | 3 | 58 | 72 | 73 (29/40) | 0 (0/91) | |

| II | 2.1 | 9 | 200 | 68 | 2 | 50.5 | 44 | 52 (16/31) | 0 (0/63) |

| 2.2 | 9 | 200 | 68 | 2 | 6.5 | 64 | ND | ND | |

| 2.3 | 9 | 200 | 68 | 2 | 9.4 | 54 | ND | ND | |

| 2.4 | 9 | 200 | 68 | 2 | 23.7 | 43 | 46 (11/24) | 0 (0/43) | |

| III | 3.1 | 11 | 100 | 49 | 1.5 | 5.7 | 47 | 54 (6/11) | 0 (0/24) |

| 3.2 | 11 | 100 | 49 | 1.5 | 4 | 35 | ND | ND | |

| 3.3 | 11 | 100 | 49 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 45 | ND | ND |

G.W/P lentiviral vector confers erythroid-specific expression in BFU-E colonies differentiating from transduced SRCs. The results from three different experiments are shown. MOI indicates MOI for CD34+ cells. TE indicates transduction efficiency assessed by FACS 4 days after transduction. ND, not done.

Ratios in parentheses indicate GFP+ colonies/total counted colonies.

FIG. 8.

Multilineage reconstitution of the BM of a NOD/SCID mouse transplanted with cord blood-derived human CD34+ hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells transduced with the G.W/P lentiviral vector (Fig. 5) at an MOI of 200. Transduction efficiency in the transplanted cells was measured by FACS analysis of ΔLNGFR expression 4 days after infection (upper left panel). Cells were transplanted in 10 different NOD/SCID mice (see Table 1 for complete data). Engraftment was analyzed by FACS analysis of the human-specific CD45 marker in bone marrow cells 9 weeks after transplantation (lower left panel). Transduction efficiency in the total engrafted cell population (CD45+, lower left panel) and in the progenitor (CD34+), B lymphoid (CD19+), and myeloid (CD13+) subpopulations (right panels) were analyzed by ΔLNGFR expression. The percentage of LNGFR-positive and -negative cells within each cell subpopulation is indicated in the appropriate quadrants.

FIG. 9.

Erythroid-specific expression of GFP in methylcellulose colonies derived from human NOD-SCID mouse repopulating cells (SRCs) transduced with the G.W/P lentiviral vector (Fig. 5) and analyzed ex vivo 9 weeks after transplantation. (A and C) Bright-field view of fully mature BFU-E and CFU-GM colonies 14 days after plating. (B and D) Green fluorescence view of the same fields (GFP-specific filters). Magnification: ×4 in panels A and B; ×10 in panels C and D.

Expression of the GATA-LTR is restricted to the erythroid progeny of murine repopulating HSCs.

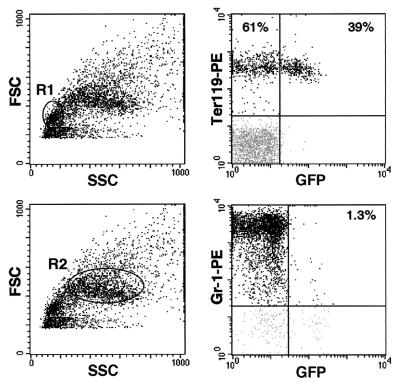

To test the lineage-specific expression of the GATA-LTR in a transplantation model supporting the terminal differentiation of all progenies derived from transduced HSCs, 5 × 106 BM cells from C57BL/6 (CD45.2+) donor mice were transduced with the G vector, further modified by the addition of the HIV-1 cPPT and WPRE sequences (MOI, 200), and transplanted into lethally irradiated C57BL/6-Ly-5.1 (CD45.1+) recipient mice. Transduction efficiency of murine progenitors, expressed as the percentage of GFP+ BFU-E colonies in a methylcellulose assay, averaged 75%. Nine to 11 weeks after transplantation, BM cells from recipient animals were analyzed for expression of GFP and erythroid (TER-119) and myeloid (Gr-1) lineage-specific markers. Engraftment of donor cells in the BM, indicated by the proportion of CD45.2+ to total CD45+ cells, ranged from 26 to 94% (data not shown). GFP+ cells were detected at a significant level (3.0 to 39%) only in the erythroblastic, TER119+ subpopulation of BM cells (Fig. 10, upper right panel). Conversely, in myeloblastic Gr-1+ cells GFP expression was virtually undetectable (0.6 to 1.3%) (Fig. 10, lower right panel). After normalization for the proportion of engrafted donor cells in BM, TER119+/GFP+ cells ranged from 3.2 to 96%. These results indicate that expression of the GATA-LTR is restricted to the fully differentiated erythroblastic progeny of transduced mouse repopulating stem cells in vivo.

FIG. 10.

Erythroid-specific expression of GFP (x axis) in BM from a representative mouse transplanted with coisogenic BM cells transduced with the G vector. Nine weeks after transplantation BM cells were stained with PE-conjugated anti-Ter-119 (erythroid-specific) and Gr-1 (myeloid-specific) (y axis) antibodies. Positivity to Ter-119 was analyzed in the blast cell-lymphocyte-gated cells (R1 in the right upper panel), and positivity to Gr-1 was analyzed in the granulocyte-monocyte-gated cells (R2 in the right lower panel). The percentage of GFP-positive and -negative cells within each cell subpopulation is indicated in the appropriate quadrants (left panels). The degree of chimerism in this representative animal, expressed as the proportion of CD45.2+ to total CD45+ cells, was 67.5%. SSC, side scatter; FSC, forward scatter.

DISCUSSION

Gene therapy of most blood genetic disorders (e.g., SCID, chronic granulomatous disease, thalassemia) requires ex vivo gene transfer into transplantable, self-renewing HSCs and regulation of transgene expression in one or more differentiated cell lineages. Lentiviral vectors are emerging as the vectors of choice for transducing HSCs without compromising their repopulation capacity after BM transplantation (10, 15, 29). However, most preclinical studies carried out so far have relied on the use of internal, constitutive promoters to drive transgene expression, while no systematic attempt has been undertaken to regulate transcription in a tissue- or cell-specific fashion (24, 28). One way to target transgene transcription is to drive an internal expression cassette with specific enhancer-promoter combinations (16). As an alternative strategy, we have attempted to redirect the activity of the HIV-1 LTR promoter by replacing most of the U3 region (from position −418 to −40 from the transcription start site) with a 200-bp autoregulatory enhancer (HS2) of the erythroid-specific GATA-1 transcription factor. In this design, the modified LTR controls the expression of the gene of interest (GFP in this study), while an internal PGK promoter drives the expression of a constitutive, independently regulated reporter gene (ΔLNGFR). Human cord blood-derived CD34+ stem-progenitor cells and murine repopulating HSCs were transduced at high efficiency (up to 70%) with this type of vector, as shown by the expression of the constitutively regulated reporter gene in undifferentiated progenitors as well as in the differentiated progenies (myeloid, lymphoid, and erythroid) obtained in vitro and in vivo upon transplantation into NOD-SCID (human cells) or coisogenic (murine cells) mice. Expression of the transgene driven by the modified LTR was successfully restricted to the erythroblastic progeny of CD34+ progenitors in vitro and of human SCID repopulating cells and murine HSCs in vivo. Transcription from the chimerical LTR was active at a low level in a subpopulation of transduced CD34+ cells (probably cycling progenitors), down-regulated in myelomonocytic cells, and up-regulated and maintained at sustained levels in erythroblastic cells, strictly paralleling the expression pattern of the GATA-1 gene during differentiation of human primary hematopoietic cells (3, 23). Modification of the LTR had no effects on titer, infectivity, and genomic stability of the vector. Interestingly, expression from the hybrid LTR does not require coexpression of TAT and appears therefore to be relatively insensitive to the presence of a TAR secondary structure in the genomic transcript produced by the integrated provirus.

As a general strategy, modification of the viral LTR offers a number of potential advantages. First, it provides a more efficient vector design, which allows the use of the major viral transcriptional unit to express a gene of interest under the form of a genomic, spliceable RNA. In this study, we have directly compared the expression of a GFP gene driven by the modified LTR with that obtained by the same enhancer-promoter combination placed in a conventional, internal position, and we showed that expression from the genomic transcript is indeed higher and better restricted than that obtained from an unspliced transcript driven by an internal promoter. Second, it allows the use of a second, independently regulated internal promoter to control additional vector functions. For most genetic diseases that could be cured by transplantation of genetically modified HSCs, providing an in vivo selection function to transduced cells (e.g., a drug resistance or a modified growth factor receptor gene) is mandatory. In our vectors, the internal promoter is transcribed at approximately constant levels in undifferentiated HSCs (CD34+ progenitors or SRCs) and all their differentiated progenies in vitro and in vivo, while transcription from the modified LTR is effectively restricted to the erythroblastic lineage. This design is therefore suitable for expressing a constitutive in vivo selection marker and a transcriptionally targeted therapeutic gene in a single vector. Third, the presence of two copies of a genomic enhancer flanking the integrated provirus could reduce the chances of chromatin-mediated inactivation of transcription, which is known to affect the long-term maintenance of retroviral transgene expression in vivo, particularly in stem cells (2). Indeed, we show that the expression driven by the GATA-LTR is persistent at uniformly high levels and independently from the number of integrated proviruses in individual clones of transduced HEL cells, showing remarkably less position-effect variegation than a vector based on the same enhancer-promoter combination placed in an internal position. This vector design could therefore be indicated in all cases in which long-term persistence of gene expression, tight gene regulation, and high-level protein expression are required in a specific progeny of transduced HSCs, such as in gene therapy of thalassemia. A major breakthrough in this field has been obtained by the use of a full β-globin gene cloned in opposite transcriptional orientation in a lentiviral vector containing a reduced version of the β-globin locus control region (LCR), which allowed the synthesis of potentially therapeutic levels of adult hemoglobin in a murine model of thalassemia (14). However, LCR sequences do not appear to confer position-independent expression to the viral-encoded transgene, even in this configuration (14). Indeed, the role of the LCR in maintaining an open chromatin conformation to the β-globin locus has been challenged by several authors (7, 20). Binding of erythroid-specific transcription factors, such as GATA-1, to enhancers of erythroid-specific genes early in development or differentiation could instead be a key factor in initiation and maintenance of active chromatin structures (13, 19), providing a rationale for using transcriptionally targeted vectors based on erythroid-specific enhancers rather than LCRs. Although we have not addressed this issue directly, our vector targeting strategy could offer an alternative design to drive β-globin gene expression in erythroblastic cells derived from transduced HSCs.

Gene expression analysis carried out on cells transduced with vectors carrying two transcriptional units showed that the internal promoter negatively interferes with the activity of the targeted LTR, thereby reducing the overall output of the vector genomic transcript with respect to single-gene vectors. Down-regulation of LTR expression is an undesirable effect of this vector design, which could reduce its usefulness for many therapeutic applications. To overcome this problem, we tried to boost gene expression at the posttranscriptional level by introducing a WPRE at different positions within the vector construct (Fig. 5). A WPRE positioned at the 3′ end of the vector was transcribed in both the genomic and the subgenomic RNA and accordingly increased expression of both GFP and ΔLNGFR. Conversely, a WPRE downstream of the GFP gene but upstream of the PGK promoter was incorporated only in the genomic transcript and caused a selective increase of the GATA-LTR-driven GFP expression with no effect on its transcriptional restriction. Use of a WPRE therefore allows modulation of the relative abundance of two different gene products within a single lentiviral vector and restoration of high-level expression of a modified LTR even in the presence of an interfering internal promoter.

An inherent limitation of our vector design is the persistence of a potentially active, TAT-responsive HIV promoter in the integrated provirus. This could theoretically be activated by superinfection of wild-type HIV, for instance in the T-cell or macrophage progeny of transduced HSCs, thereby leading to mobilization of the vector genome into infective HIV particles. Although the occurrence of such an event should be practically verified in an appropriate in vivo model, vector mobilization would be an undesirable effect, potentially affecting the safety characteristics of the gene transfer system for clinical applications. However, last-generation lentiviral packaging systems do not rely any more on TAT for the expression of the transfer vector into the packaging cell line (12), allowing us to design lentiviral vectors which do not incorporate a TAR element in the primary transcript. Mutation of the TAR element downstream to the targeted LTR should abolish the possibility of HIV-induced mobilization of the vector and therefore restore a degree of safety comparable to that of the currently used, fully U3-deleted SIN vectors.

In conclusion, we report a new lentiviral vector design based on the use of an enhancer-replaced, transcriptionally targeted HIV LTR to express a therapeutic gene and of a second, independently regulated internal promoter to drive the expression of an accessory function such as an in vivo selection marker. This vector combines the advantages of using the spliced, genomic viral transcript to obtain high-level protein expression with the possibility to direct gene expression in a tissue- or cell-specific function through the use of a cellular enhancer to restrict the activity of the LTR promoter. Such a vector design appears particularly suited for gene therapy applications based on genetic modification of pluripotent HSCs with transcriptionally targeted transgenes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a core grant from the Italian Telethon Foundation and by a grant from the European Union Fifth Framework Program (key action 3.1.3, contract no. QLRT-99-00859). F.L. is partially supported by a fellowship from the H. San Raffaele/Open University Ph.D. Program.

We thank Bianca Piovani and Barbara Camisa for expert technical assistance with primary human cell cultures and murine bone marrow transplantation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cashman, J., and C. Eaves. 1999. Human growth factor-enhanced regeneration of transplantable human hematopoietic stem cells in nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficient mice. Blood 93:481-487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Challita, P. M., and D. B. Kohn. 1994. Lack of expression from a retroviral vector after transduction of murine hematopoietic stem cells is associated with methylation in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:2567-2571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng, T., H. Shen, D. Giokas, J. Gere, D. G. Tenen, and D. T. Scadden. 1996. Temporal mapping of gene expression levels during the differentiation of individual primary hematopoietic cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:13158-13163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coffin, J. M., S. H. Hughes, and H. E. Varmus. 1997. Retroviruses. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y. [PubMed]

- 5.Crystal, R. G. 1995. Transfer of genes to humans: early lessons and obstacles to success. Science 270:404-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dull, T., R. Zufferey, M. Kelly, R. J. Mandel, M. Nguyen, D. Trono, and L. Naldini. 1998. A third-generation lentivirus vector with a conditional packaging system. J. Virol. 72:8463-8471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Epner, E., A. Reik, D. Cimbora, A. Telling, M. A. Bender, S. Fiering, T. Enver, D. I. K. Martin, M. Kennedy, G. Keller, and M. Groudine. 1998. The β-globin LCR is not necessary for an open chromatin structure or developmentally regulated transcription of the native mouse β-globin locus. Mol. Cell 2:447-455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Evans, T., and G. Felsenfeld. 1989. The erythroid-specific transcription factor Eryf1: a new finger protein. Cell 58:877-885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrari, G., G. Salvatori, C. Rossi, G. Cossu, and F. Mavilio. 1995. A retroviral vector containing a muscle-specific enhancer drives gene expression only in differentiated muscle fibers. Hum. Gene Ther. 6:733-742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Follenzi, A., L. E. Ailles, S. Bakovic, M. Geuna, and L. Naldini. 2000. Gene transfer by lentiviral vectors is limited by nuclear translocation and rescued by HIV-1 pol sequences. Nat. Genet. 25:217-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grande, A., B. Piovani, A. Aiuti, S. Ottolenghi, F. Mavilio, and G. Ferrari. 1999. Transcriptional targeting of retroviral vectors to the erythroblastic progeny of transduced hematopoietic stem cells. Blood 93:3276-3285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klages, N., R. Zufferey, and D. Trono. 2000. A stable system for the high-titer production of multiply attenuated lentiviral vectors. Mol. Ther. 2:170-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin, D. I., S. Fiering, and M. Groudine. 1996. Regulation of beta-globin gene expression: straightening out the locus. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 6:488-495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.May, C., S. Rivella, J. Callegari, G. Heller, K. M. Gaensler, L. Luzzatto, and M. Sadelain. 2000. Therapeutic haemoglobin synthesis in beta-thalassaemic mice expressing lentivirus-encoded human beta-globin. Nature 406:82-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miyoshi, H., K. A. Smith, D. E. Mosier, I. M. Verma, and B. E. Torbett. 1999. Transduction of human CD34+ cells that mediate long-term engraftment of NOD/SCID mice by HIV vectors. Science 283:682-686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moreau-Gaudry, F., P. Xia, G. Jiang, N. P. Perelman, G. Bauer, J. Ellis, K. H. Surinya, F. Mavilio, C. K. Shen, and P. Malik. 2001. High-level erythroid-specific gene expression in primary human and murine hematopoietic cells with self-inactivating lentiviral vectors. Blood 98:2664-2672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mulligan, R. C. 1993. The basic science of gene therapy. Science 260:926-932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nicolis, S., C. Bertini, A. Ronchi, S. Crotta, L. Lanfranco, E. Moroni, B. Giglioni, and S. Ottolenghi. 1991. An erythroid specific enhancer upstream to the gene encoding the cell-type specific transcription factor GATA-1. Nucleic Acids Res. 19:5285-5291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Orkin, S. H. 1995. Regulation of globin gene expression in erythroid cells. Eur. J. Biochem. 231:271-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reik, A., A. Telling, G. Zitnik, D. Cimbora, E. Epner, and M. Groudine. 1998. The locus control region is necessary for gene expression in the human β-globin locus but not the maintenance of an open chromatin structure in erythroid cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:5992-6000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruggieri, L., A. Aiuti, M. Salomoni, E. Zappone, G. Ferrari, and C. Bordignon. 1997. Cell-surface marking of CD(34+)-restricted phenotypes of human hematopoietic progenitor cells by retrovirus-mediated gene transfer. Hum. Gene Ther. 8:1611-1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 23.Sposi, N. M., L. I. Zon, A. Care, M. Valtieri, U. Testa, M. Gabbianelli, G. Mariani, L. Bottero, C. Mather, S. H. Orkin, et al. 1992. Cell cycle-dependent initiation and lineage-dependent abrogation of GATA-1 expression in pure differentiating hematopoietic progenitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:6353-6357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trono, D. 2000. Lentiviral vectors: turning a deadly foe into a therapeutic agent. Gene Ther. 7:20-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsai, S. F., D. I. Martin, L. I. Zon, A. D. D'Andrea, G. G. Wong, and S. H. Orkin. 1989. Cloning of cDNA for the major DNA-binding protein of the erythroid lineage through expression in mammalian cells. Nature 339:446-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsai, S. F., E. Strauss, and S. H. Orkin. 1991. Functional analysis and in vivo footprinting implicate the erythroid transcription factor GATA-1 as a positive regulator of its own promoter. Genes Dev. 5:919-931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Verma, I. M., and N. Somia. 1997. Gene therapy--promises, problems and prospects. Nature 389:239-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vigna, E., and L. Naldini. 2000. Lentiviral vectors: excellent tools for experimental gene transfer and promising candidates for gene therapy. J. Gene Med. 2:308-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woods, N. B., C. Fahlman, H. Mikkola, I. Hamaguchi, K. Olsson, R. Zufferey, S. E. Jacobsen, D. Trono, and S. Karlsson. 2000. Lentiviral gene transfer into primary and secondary NOD/SCID repopulating cells. Blood 96:3725-3733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zufferey, R., J. E. Donello, D. Trono, and T. J. Hope. 1999. Woodchuck hepatitis virus posttranscriptional regulatory element enhances expression of transgenes delivered by retroviral vectors. J. Virol. 73:2886-2892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zufferey, R., T. Dull, R. J. Mandel, A. Bukovsky, D. Quiroz, L. Naldini, and D. Trono. 1998. Self-inactivating lentivirus vector for safe and efficient in vivo gene delivery. J. Virol. 72:9873-9880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zufferey, R., D. Nagy, R. J. Mandel, L. Naldini, and D. Trono. 1997. Multiply attenuated lentiviral vector achieves efficient gene delivery in vivo. Nat. Biotechnol. 15:871-875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]