Abstract

The polytopic membrane protein presenilin 1 (PS1) is a component of the γ-secretase complex that is responsible for the intramembranous cleavage of a number of type I transmembrane proteins including the β-amyloid precursor protein (APP). Mutations of PS1, apparently leading to aberrant processing of APP, have been genetically linked to early-onset familial Alzheimer's disease. PS1 contains ten hydrophobic regions (HRs) sufficiently long to be α-helical membrane spanning segments. Most topology models for PS1 place its C-terminal ∼40 amino acids, which include the 10th HR, in the cytosolic space. However, several recent observations suggest that HR 10 may be integrated into the membrane and involved in the interaction between PS1 and APP. We have applied three independent methodologies to investigate the location of HR 10 and the extreme C-terminus of PS1. The results from these methods indicate that HR 10 spans the membrane and that the C-terminal amino acids of PS1 lie in the extra-cytoplasmic space.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, γ-secretase, β-amyloid, intramembranous protease, transmembrane topology

INTRODUCTION

Presenilin 1 (PS1) is thought to be the proteolytic component of the γ-secretase complex that is responsible for the intramembranous cleavage of a number of type I transmembrane proteins including the β-amyloid precursor protein (APP) (1,24,27). Mutations in PS1 have been genetically linked to cases of early-onset familial Alzheimer's disease (25). These mutations apparently lead to aberrant processing of APP resulting in increased production of the longer neurotoxic form of β-amyloid found in the characteristic senile plaques observed in the brains of Alzheimer's patients (1,24,27). Because of its role in the processing of APP, γ-secretase, and thereby PS1, is considered to be a major therapeutic target for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease.

PS1 is a ∼50 kDa integral membrane protein. In cells the PS1 holoprotein is rapidly endoproteolysed by cleavage near Met292. The resulting ∼30 kDa N-terminal fragment (NTF) and ∼20 kDa C-terminal fragment (CTF) are found in high molecular weight complexes with the integral membrane proteins nicastrin, PEN-2 and APH-1 which together are thought to constitute the γ-secretase (27). Recent evidence suggests that the components of these complexes not only stabilize PS1 but are also involved in its maturation by endoproteolysis (20,26).

An understanding of the transmembrane topology of PS1 is clearly essential to the interpretation of its role in γ-secretase activity. Hydropathy analysis shows that PS1 contains ten hydrophobic regions (HRs) sufficiently long to form α-helical membrane spanning segments (MSSs; Fig. 1A). Essentially two types of studies have been performed by various groups to study the PS1 topology: experiments examining antibody epitope accessibility before and after plasma membrane permeabilization (5-8), and experiments examining the membrane integration of truncated forms of PS1 (17,21) or SEL-12 (18,19), a PS1 homologue from C. elegans. In these latter experiments reporter peptides were fused to PS1 or SEL-12 truncated after each HR and these chimeric proteins were expressed in isolated microsomes or intact cells. Assays were then carried out to determine the location of the reporter peptide in the cytosolic or extracellular compartment, allowing one to infer the ability of each successive HR to integrate into the membrane.

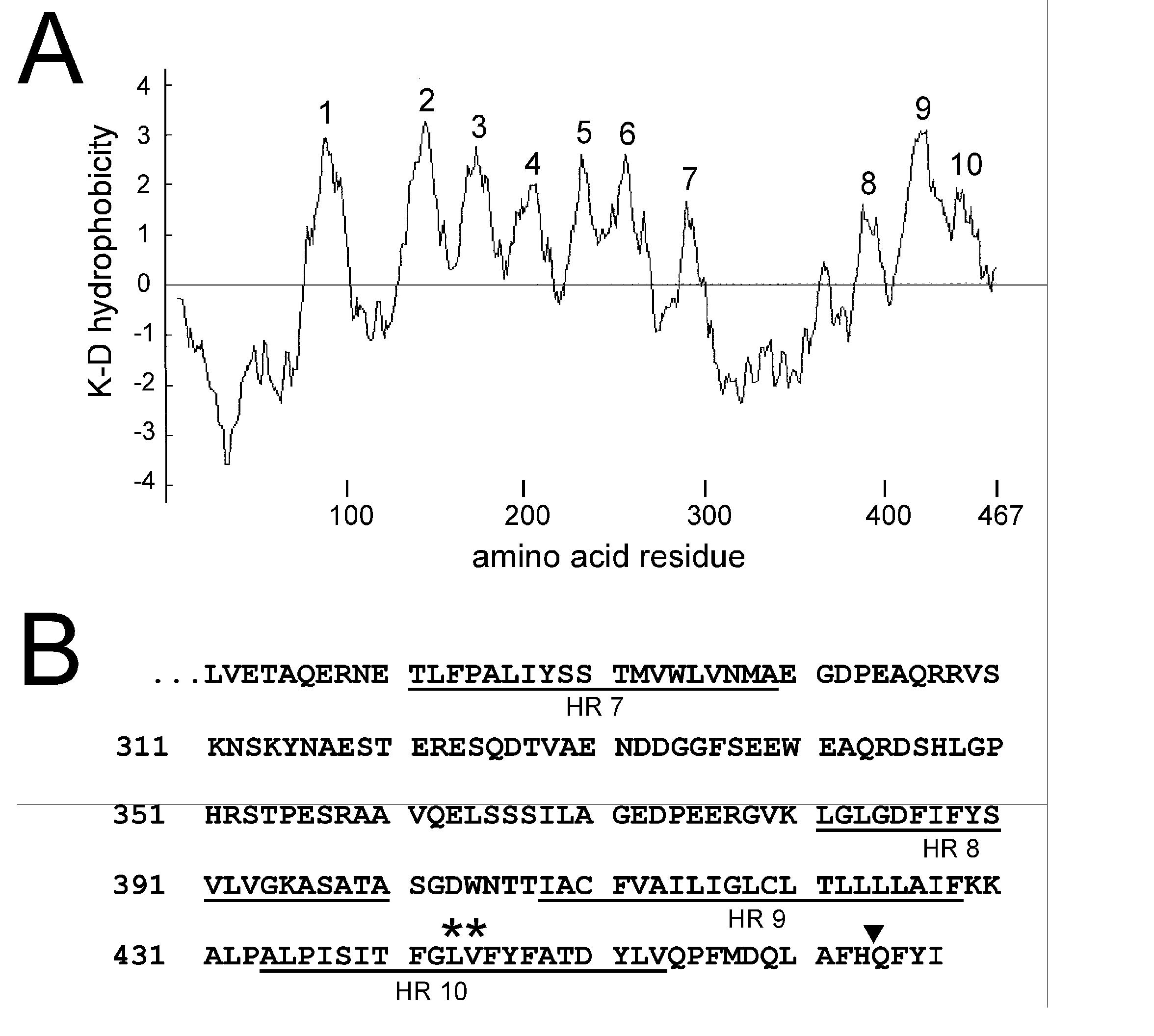

Figure 1.

Hydrophobicity and sequence of human PS1. A. Hydrophobicity plot of human PS1 obtained using the method of Kyte and Doolittle (K-D) with a 15 amino acid window. The 10 hydrophobic regions (HRs) referred to in the text are indicated. B. C-terminal sequence of PS1. The underlined amino acids indicate the approximate positions of HRs 7-10. The position of an inserted glycosylation site (filled triangle after His463) and two amino acids subjected to mutagenesis (asterisks) are also indicated (see text).

All of the above studies (recently reviewed in (14)) agree that HRs 1-6 are MSSs and that HR 7 is left out of the membrane so that the N-terminus of PS1 and the ‘loop’ region between HRs 6 and 8 are on the same side of the membrane. Most groups propose that the N-terminus and loop are cytosolic, however, Dewji and Singer have presented evidence from antibody accessibility studies that they are exposed on the extracellular surface of intact cells (6,7). There is some disagreement as to whether HRs 8 and 9 span the membrane or are peripherally associated with it, but all groups find that the C-terminal end of HR 9 faces the cytoplasm and all groups but one (21) find that HR 10 is left out of the membrane on the cytosolic side. In these latter dissenting studies Nakai et al. (21) found that a glycosylation tag appended to the end of full length PS1 was glycosylated when this fusion protein was expressed in the presence of dog pancreatic microsomes or in COS-1 cells. They concluded that HR 10 was a MSS so that the C-terminus of PS1 was located in the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). But this observation has been largely ignored and a topology model suggested by Li and Greenwald, based mainly on studies carried out on SEL-12 (18,19), is most commonly accepted (14). This model proposes that the N-terminus of PS1 is cytosolic, HRs 1-6, 8 and 9 are MSSs, and HR 10 is left out of the membrane on the cytosolic side.

Recently, however, Annaert et al. (2) have found evidence that the C-terminal 39 amino acids of PS1 bind specifically to the MSSs of both APP and telencephalin, another γ-secretase substrate. This 39 amino acid stretch begins at the C-terminal end of HR 9 and thus includes HR 10 (Fig. 1B). On the basis of their results Annaert et al. have proposed that the binding site in PS1 for type I membrane protein substrates actually lies within the membrane and that these 39 amino acids form a part of this binding pocket. This hypothesis is clearly difficult to reconcile with the commonly accepted view that the sequence downstream of HR 9 lies in the cytosol. In the experiments presented here we reexamine the location of the C-terminus of PS1 and the association of HR 10 with the membrane. We present the results of experiments carried out using 3 independent methodologies which provide strong evidence that HR 10 spans the membrane and that the C-terminus of PS1 lies in the extra-cytosolic compartment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clones and antibodies

The human PS1 clone and Swedish APP mutant (APP695ΔNL) were generously provided by Dr. Todd E. Golde (Mayo Clinic Jacksonville). We utilized commercial rabbit polyclonal antibodies against calregulin, the N-terminal 70 amino acids of human PS1 (PS1-N), the N-terminus of calnexin (all from Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and GFP (Molecular Probes). A mouse monoclonal antibody (PS1-Loop) raised against amino acids 263-378 of human PS1 was from Chemicon. The rabbit polyclonal antibodies 4627, raised against the C-terminal 10 amino acids of PS1 (22), and PS1-C (29) raised against the C-terminal 14 amino acids of PS1, were generous gifts from Drs. Dennis Selkoe (Harvard Medical School) and Hui Zheng (Baylor College of Medicine), respectively.

Cell culture and transfection

HEK-293 and HEK293T cells were cultured and transfected as previously described (9). The PS1/PS2 double-knockout cell line BD1 (11), a generous gift from Dr Alan Bernstein (Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto), was cultured as described (30) and transfected using FuGENE (Roche).

Preparation of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) vesicles and proteinase K digestion

The procedure for the proteinase K experiments was based on that of Feramisco et al. (12) with some modifications. Briefly, HEK-293 cells were collected in buffer A (10 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.4, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM Na-EDTA, 5 mM Na-EGTA, and 250 mM sucrose; all steps at 4°C), homogenized by passing through a 22 gauge needle 15 times, and centrifuged at 3,000g for 10 min. The supernatant was centrifuged at 20,000g for 15 min and the resulting pellet containing sealed cytosolic-side-out ER vesicles (see Results) was resuspended in buffer A containing 100 mM NaCl. Aliquots of this preparation (2-4 μg of protein) were treated with 2 mg/ml proteinase K (Sigma, P5568) in the presence or absence of 1% Triton-X-100 in a total volume of 12 μl for 30 min on ice. The reaction was stopped by adding PMSF at a final concentration of 20-30 mM. Samples were then subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis.

DNA Constructs

The segments of the human PS1 sequence indicated were cloned into the mammalian expression vector pEGFP-β (10). This vector drives the expression of a fusion protein consisting of the enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) followed by Bgl II and Hind III restriction sites for the insertion of (PS1) sequence and a C-terminal glycosylation tag.

Site-directed mutagenesis was carried out using the Quikchange and Quikchange II XL kits (Stratagene) used according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Preparation and deglycosylation of membrane fractions

Particulate fractions were prepared from HEK-293T cells transiently transfected with pEGFP-β constructs as previously described (10). A membrane fraction was prepared from this particulate fraction by alkaline floatation essentially as previously described (10) except that all sucrose solutions were buffered with 100 mM Na2CO3 (pH 11.5). Membrane fractions were deglycosylated using peptide:N-glycosidase F (PNGase F; New England Biolabs)(10).

SDS-PAGE, Western blotting and data analysis

SDS-PAGE and Western blotting were carried out as previously described (10). Quantitation of Western blots was done using ImageQuant 5.2 software (Molecular Dynamics).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Proteinase K digestion

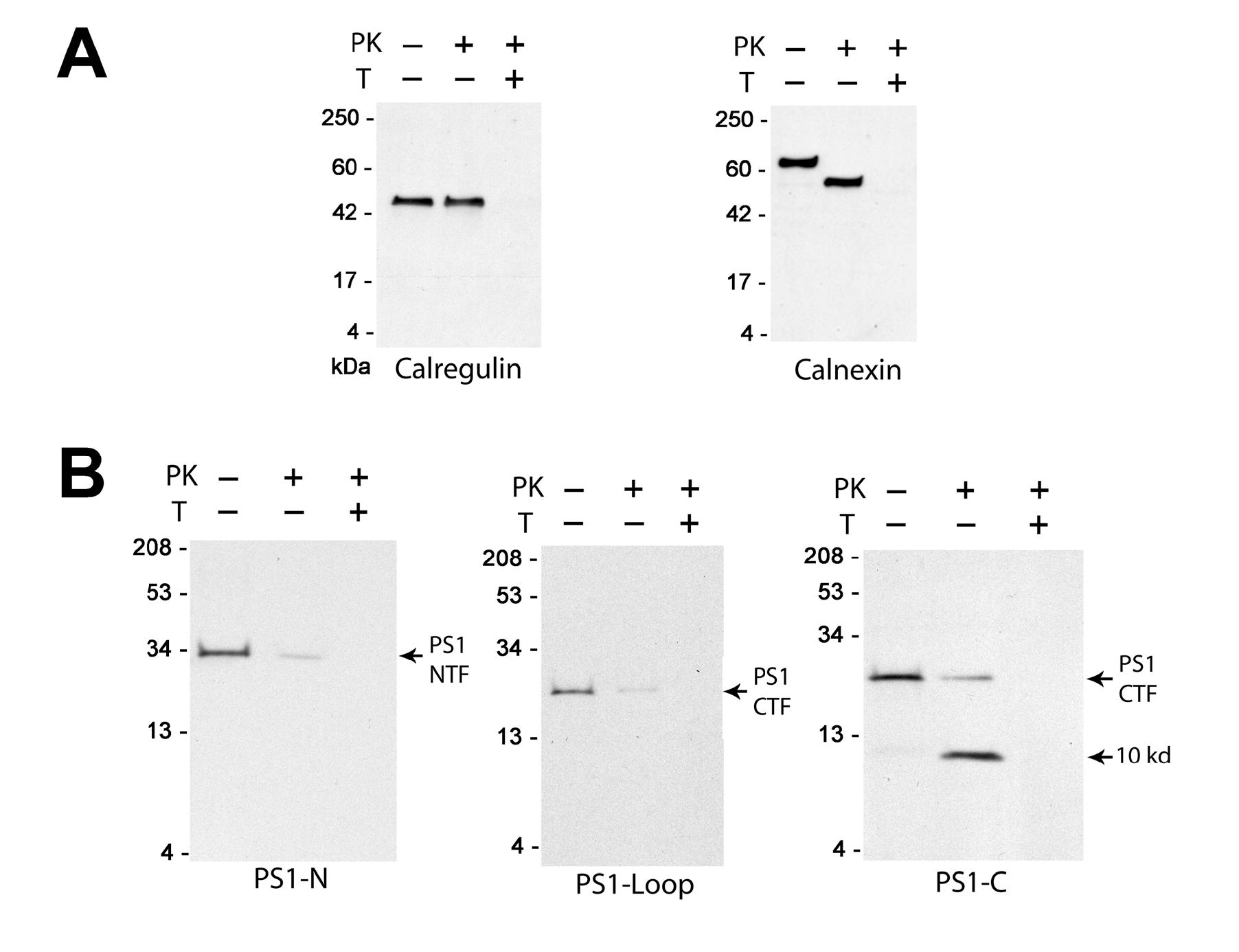

Endogenously expressed PS1 is found predominantly in the ER and in early ER to cis-Golgi compartments (3,15,28). To examine the location of the N- and C-termini and the loop region of endogenously expressed PS1 relative to the ER membrane we isolated ER vesicles from HEK293 cells and subjected them to proteinase K digestion in the presence or absence of 1% Triton X100 (see Methods). When we assayed this preparation via Western blotting for calregulin, an ER luminal protein, and calnexin, an ER membrane protein, we found that 99.0±5.6% (n=10) and 95.6±3.2% (n=8), respectively, of their immunoreactive signals were preserved after proteinase K treatment (Fig. 2A). In addition, the apparent molecular weight of calnexin was shifted downward ∼10 kDa by proteinase K consistent with the digestion of its cytosolic ∼90 amino acid C-terminus. Both the calregulin and calnexin signals were lost when digestion was carried out in the presence of 1% Triton X100 which solubilizes the vesicle membrane. Taken together these results demonstrate that virtually all of the ER membranes in this preparation are in the form of sealed cytosolic-side-out vesicles.

Figure 2.

Proteinase K digestion of endogenously expressed PS1. Representative Western blots of ER vesicles before (−) and after (+) treatment with proteinase K (PK) in the presence (+) or absence (−) of 1% Triton X-100 (T); see Methods for details. Blots were probed (A) with antibodies against calregulin and calnexin, or (B) with the antibodies PS1-N , PS1-Loop and PS1-C, as indicated. A similar resistance to epitope digestion by proteinase K was observed with the PS1-C antibody in HeLa, SH-SY5Y, and sf295 cells and with the antibody 4627 in HEK293 cells (not shown).

When these vesicles were probed with the antibodies PS1-N, raised against the N-terminus of PS1, and PS1-Loop, raised against the loop region, we found that only 4.4±2.0% (n=7) and 5.0±1.4% (n=7), respectively, of their immunoreactive signals remained undigested after proteinase K treatment (Fig. 2B). This undigested material was at the molecular weight of the full length NTF and CTF, recognized by PS1-N and PS1-Loop, respectively. Thus at least 95% of the PS1 molecules in this preparation are oriented with their N-termini and loop regions facing the cytoplasmic side of the ER where they are accessible to proteinase K. In additional experiments where we varied proteinase K concentration and/or digestion time we were unable to decrease the remaining signals from these antibodies below ∼5% (not shown). This result may indicate that a small population of PS1 molecules are oriented with their N-termini and loop regions toward the intravesicular space. However, if this were the case one might have expected a downward shift in the molecular weight of the remaining signal due to proteinase K digestion at other accessible sites (cf., calnexin in panel A). Accordingly we feel that it is more likely that these remaining signals represent PS1 molecules that for some reason are resistant to proteinase K (e.g., they may represent aggregated material).

In contrast to our results for PS1-N and PS1-Loop, we find that 100.2±7.6% (n=9) of the immunoreactive signal of the antibody PS1-C, raised against the extreme C-terminus of PS1, remains after proteinase K treatment. This signal is present in two bands, one at or near the molecular weight of the undigested CTF and the other at 10.0±0.3 kDa, representing 26.0±4.3% and 74.2±8.3% of the starting signal, respectively (Fig. 2B). We have not attempted to determine the reason why only 5% of the full length CTF signal is resistant to proteinase K when assayed by the PS1-Loop antibody vs. 26% when assayed by the PS1-C antibody. However, it is possible that the epitope recognized by PS1-Loop (a monoclonal antibody) lies near the N-terminal end of the CTF and may be digested from some of the molecules detected by PS1-C near the molecular weight of the full length CTF. In this regard, in our preliminary experiments (not shown) we noted that PS1 was considerably more resistant to digestion by proteinase K than calnexin, possibly because, as a part of a large membrane bound protein complex, PS1 is relatively less accessible from the surrounding medium. Nevertheless what is strikingly clear from Fig. 2B is that the accessibility of the extreme C-terminus of PS1 to proteinase K is quite different from that of the N-terminus and the loop region, strongly suggesting that it does not lie in the cytosolic compartment.

Reporter gene fusion

To further examine the location of the C-terminus of PS1 we have used a gene fusion approach where portions of the PS1 sequence were fused between EGFP and a C-terminal glycosylation tag (see Methods). This latter sequence contains five consensus sites for N-linked glycosylation (10); when translocated into the interior of the ER it acquires ∼14 kDa of apparent molecular weight due to glycosylation, an increase that is easily discerned on SDS-PAGE. The utility of this experimental system for membrane topology and biogenesis studies has been previously documented (9,10).

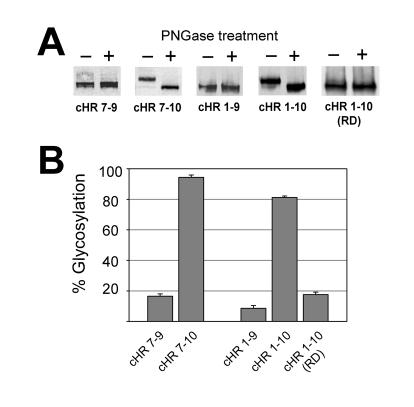

In Fig. 3 we illustrate the results of experiments where PS1 fragments encoding HRs 7-9 (cHR 7-9), HRs 7-10 (cHR 7-10), HRs 1-9 (cHR 1-9) and HRs 1-10 (full length PS1; cHR 1-10) were expressed as EGFP fusion proteins in HEK-293T cells. In each of the panels in Fig. 3A we show the results of a typical experiment where the membrane fraction from HEK-293T cells, transiently transfected with the construct indicated, was treated with (+) or without (−) PNGase F (see Methods). These membrane fractions were run on SDS-PAGE and probed by Western blotting using an antibody against EGFP to determine their extent of glycosylation and thus the location of the glycosylation tag inside or outside the ER lumen (Fig. 3B). Little glycosylation is seen for either cHR 7-9 or cHR 1-9 where the PS1 sequence ends after HR 9, consistent with the general consensus that the C-terminal end of HR 9 faces the cytoplasm (see Introduction). However, both fusion proteins that incorporate HR 10 (cHR 7-10 and cHR 1-10) are highly glycosylated indicating that HR 10 spans the membrane in these constructs. To confirm this interpretation, in the fusion protein cHR 1-10 (RD) we have mutated amino acids Leu443 and Val444 near the middle of HR 10 (Fig. 1B) in cHR 1-10 to Arg and Glu, respectively, dramatically reducing the hydrophobicity of HR 10. As illustrated in Fig. 3B the glycosylation of this mutated construct is markedly reduced relative to cHR 1-10 confirming that the glycosylation of cHR 1-10 is dependent on the hydrophobicity of HR 10, consistent with its role as a MSS.

Figure 3.

Evidence for integration of HR 10 into the membrane. A. Membranes prepared from HEK-293T cells transfected with the constructs indicated were treated with (+) or without (−) PNGase F and analyzed by Western blotting; see Methods for details.B. For each construct the density of the glycosylated band has been expressed as a percentage of the total recombinant protein (n≥3). The PS1 sequences cloned into pEGFP-β were Leu271-Pro433 (cHR 7-9), Leu271-Iso467 (cHR 7-10), Met1-Pro433 (cHR 1-9) and Met1-Iso467 (cHR 1-10; full length PS1). In cHR 1-10 (RD) the PS1 residues Leu443 and Val444 of cHR1-10 were mutated to Arg and Glu, respectively (Fig. 1B).

Insertion of N-linked glycosylation site

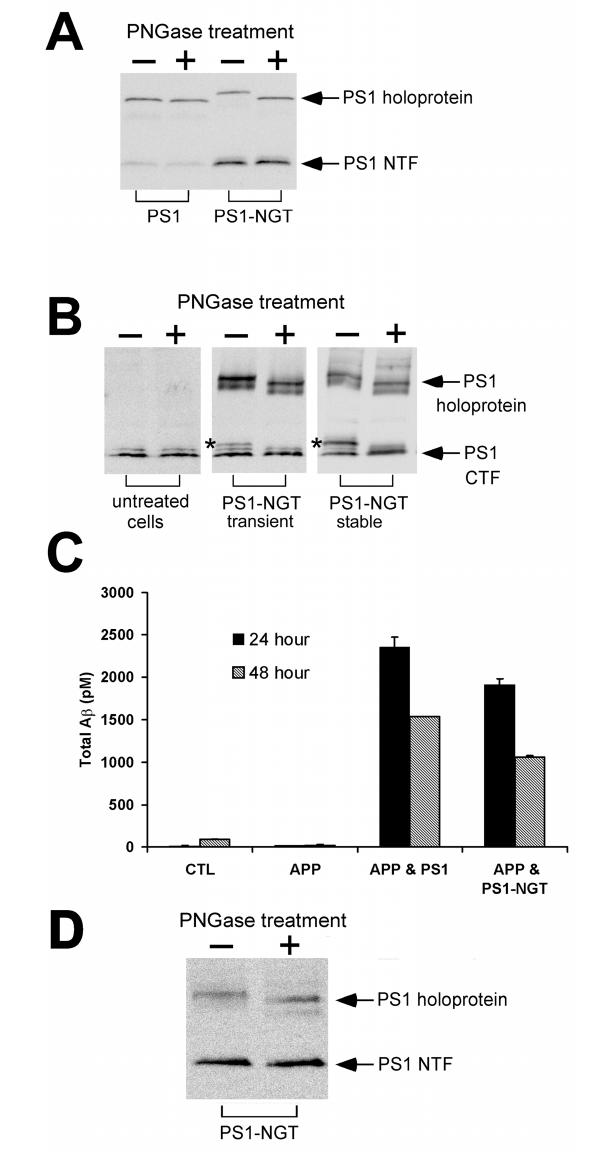

In Fig. 4 we illustrate the results of experiments where we have transfected cells with unmodified full length PS1 and with the clone PS1-NGT into which we have inserted a glycosylation consensus site (AsnGlyThr) after His463, four amino acids from its C-terminal end (Fig. 1B). In the Western blot shown in Fig. 4A, probed with the antibody PS1-N against the NTF of PS1, we find that the PS1-NGT holoprotein is 91 ± 3% (n = 3) glycosylated indicating that the C-terminus of this minimally modified version of PS1 is likewise exposed to the ER lumen.

Figure 4.

Effect of insertion of a glycosylation site near the C-terminal end of PS1. A. HEK-293T cells were transfected overnight with wild-type PS1 or PS1 into which a glycosylation consensus site had been inserted after H463 (PS1-NGT). Western blotting was carried out using PS1-N. B. Western blots of membranes from untreated HEK293 cells, or HEK293 cells transiently (4 days) or stably transfected with PS1-NGT, probed with the PS1-Loop antibody. Indicated by an asterisk is a band appearing only in PS1-NGT-transfected cells that is lost following treatment with PNGase F. The faint band running just above the CTF in untreated as well as transfected HEK-293 cells is thought to be due to PS1 phosphorylation (16). C. γ-secretase activity (total APP cleavage products in the extracellular medium) was measured in mock transfected BD-1 (PS1/PS2 double knockout) cells (CTL), and in BD-1 cells transfected with the Swedish APP mutant alone (APP) or in combination with wild-type PS1 (APP & PS1) or PS1-NGT (APP & PS1-NGT) as indicated. Cells were transfected for 6 h on day 0 then rested overnight. On day 1 the culture medium was changed and aliquots were collected on day 2 (24 h) and day 3 (48 h). Samples were assayed for total Aβ production according to (4). The results of one representative experiment of two carried out are shown. D. Western blot of membranes prepared from BD-1 cells transiently transfected with PS1-NGT, harvested on day 3 of the protocol described in C, and probed with the PS1-N antibody.

In Fig. 4B we show the results of experiments where PS1-NGT was transiently or stably expressed in HEK293 cells. Western blots of membranes from these cells as well as membranes from untreated cells were probed with the antibody PS1-Loop that recognizes the CTF of PS1. As in Fig. 4A we find that the PS1-NGT holoprotein is highly glycosylated. In addition, in these cells we observe a band running above the CTF of PS1 that is lost following treatment with PNGase F (marked with an asterisk). The presence of this glycosylated band, which is not seen in untransfected cells, indicates that the recombinant glycosylated protein PS1-NGT undergoes normal endoproteolytic maturation like wild-type PS1. In additional experiments (not shown) we have not been able to detect a component of Endoglycosidase H-resistant complex glycosylation associated with PS1-NGT. Since complex glycosylation takes place in the Golgi this observation is consistent with the prominent localization of PS1 to the ER. However, this does not preclude the existence of a small component of complex-glycosylated PS1-NGT that is undetectable in our experiments, especially since these bands often tend to be quite diffuse.

To test whether PS1-NGT could produce functional γ-secretase activity we transiently expressed it in BD-1 cells (which have no endogenous γ-secretase activity since they lack both PS1 and PS2 (11)) and measured the production of APP cleavage products (Total Aβ) in the extracellular solution. As illustrated in Fig. 4C this glycosylation mutant yielded similar activity to wild-type PS1. In Western blots of membranes from transfected BD-1 cells we were unable to detect any significant component of unglycosylated PS1-NGT (Fig. 4D).

Relationship to previous topology studies of PS1

As already discussed, our data from endogenously expressed PS1 indicating that the N-terminus and loop region between HRs 6 and 8 are cytosolic (Fig. 2) are in agreement with the conclusions of most other groups that have studied the PS1 topology. Dewji and Singer have presented evidence that the epitopes of antibodies directed against the N-terminus and loop regions are accessible on the surface of unpermeabilized cells (6,7). Similar results were found by Schwarzman et al. using an N-terminal antibody (23). While we cannot exclude the possibility that there is a pool of PS1 on the cell surface with an opposite orientation, our results are consistent with the conclusion that the vast majority of PS1 molecules that are synthesized in the ER have their N-terminus and loop regions in the cytoplasm.

Our conclusion that the C-terminus of HR 9 is cytosolic (Fig. 3) is in agreement with all groups that have studied the PS1 topology. In addition our results provide strong evidence that HR 10 is a MSS and that the C-terminal tail of PS1 is located in the ER lumen where it is inaccessible to proteinase K applied from the cytosolic compartment and accessible to luminal oligosaccharyl transferase (Figs. 3 and 4). As discussed in the Introduction, these findings are in agreement with the results of Nakai et al. (21) obtained using a reporter gene fusion approach and are consistent with the proposal of Annaert et al. (2) that the PS1 binding site for type I membrane protein includes HR 10 and lies within the membrane. Although the topology model of Li and Greenwald for the PS1 homologue SEL-12 (18,19) places HR 10 in the cytosol of C. elegans, our results provide strong evidence that this is not the case for PS1 in the mammalian cell lines we have tested.

Two groups that have examined the accessibility of PS1 C-terminal antibody epitopes also concluded that the C-terminus of PS1 is cytosolic (6-8), i.e., that C-terminal epitopes are not accessible in cells without treatment with membrane permeabilizing agents. But experiments of this type are complicated by the facts that that the majority of PS1 is localized to intracellular membranes (8), and that permeabilizing agents may also alter epitope affinity and/or accessibility independent of their permeabilizing effects. To distinguish between cytosolic and luminal epitopes these experiments depend on agents that selectively permeabilize the plasma membrane without permeabilizing intracellular compartments. Because of the large amount of intracellular PS1 even a small permeabilization of intracellular membranes could potentially confound their interpretation. Also, the C-terminal antibody used by one of these groups (6,7) was raised against a 9 amino acid peptide from human PS2 (STDNLVRPF) which is homologous to amino acids 448-456 of human PS1 (ATDYLVQPF); but the first 6 amino acids of this peptide actually lie within HR 10 of PS1 (Fig. 1B). Since we place HR 10 in the bilayer we would not have expected this epitope to be accessible from either side of the membrane in the absence of detergent.

Finally we note that in a recent publication Friedmann et al. (13) have studied the topology of 5 homologues of the presenilins found in the human genome. These include signal peptide peptidase and 4 signal peptide peptidase-like (putative) proteases. Interestingly they propose that all five of these proteins have a 9 MSS topology with extracellular N-termini and intracellular C-termini, i.e., with termini in the reverse orientation to our findings for PS1. Because of their reverse orientation in the membrane these proteins are thought to be intramembranous proteases acting on type II membrane proteins as substrates (13).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Drs. T.E. Golde and A.C. Nyborg for generously performing the γ-secretase assays. We also thank Dr. Bruce J. Baum for many helpful discussions during the course of this work.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- PS1

presenilin 1

- HR

hydrophobic region

- APP

β-amyloid precursor protein

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- MSS

membrane spanning segment

- PNGase F

peptide:N-glycosidase F

- NTF

N-terminal fragment

- CTF

C-terminal fragment

REFERENCES

- 1.Annaert W, De Strooper B. A cell biological perspective on Alzheimer's disease. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2002;18:25–51. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.18.020402.142302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Annaert WG, Esselens C, Baert V, Boeve C, Snellings G, Cupers P, Craessaerts K, De Strooper B. Interaction with telencephalin and the amyloid precursor protein predicts a ring structure for presenilins. Neuron. 2001;32:579–589. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00512-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Annaert WG, Levesque L, Craessaerts K, Dierinck I, Snellings G, Westaway D, George-Hyslop PS, Cordell B, Fraser P, De SB. Presenilin 1 controls gamma-secretase processing of amyloid precursor protein in pre-golgi compartments of hippocampal neurons. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:277–294. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.2.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Das P, Howard V, Loosbrock N, Dickson D, Murphy MP, Golde TE. Amyloid-beta immunization effectively reduces amyloid deposition in FcRgamma-/- knock-out mice. J Neurosci. 2003;23:8532–8538. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-24-08532.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Strooper B, Beullens M, Contreras B, Levesque L, Craessaerts K, Cordell B, Moechars D, Bollen M, Fraser P, George-Hyslop PS, Van Leuven F. Phosphorylation, subcellular localization, and membrane orientation of the Alzheimer's disease-associated presenilins. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:3590–3598. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.6.3590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dewji NN, Singer SJ. The seven-transmembrane spanning topography of the Alzheimer disease-related presenilin proteins in the plasma membranes of cultured cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:14025–14030. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.14025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dewji NN, Valdez D, Singer SJ. The presenilins turned inside out: implications for their structures and functions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:1057–1062. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307290101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doan A, Thinakaran G, Borchelt DR, Slunt HH, Ratovitsky T, Podlisny M, Selkoe DJ, Seeger M, Gandy SE, Price DL, Sisodia SS. Protein topology of presenilin 1. Neuron. 1996;17:1023–1030. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80232-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dohke Y, Oh YS, Ambudkar IS, Turner RJ. Biogenesis and topology of the transient receptor potential Ca2+ channel TRPC1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:12242–12248. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312456200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dohke Y, Turner RJ. Evidence that the transmembrane biogenesis of aquaporin 1 is cotranslational in intact mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:15215–15219. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100646200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donoviel DB, Hadjantonakis AK, Ikeda M, Zheng H, Hyslop PS, Bernstein A. Mice lacking both presenilin genes exhibit early embryonic patterning defects. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2801–2810. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.21.2801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feramisco JD, Goldstein JL, Brown MS. Membrane topology of human insig-1, a protein regulator of lipid synthesis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:8487–8496. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312623200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedmann E, Lemberg MK, Weihofen A, Dev KK, Dengler U, Rovelli G, Martoglio B. Consensus analysis of signal Peptide peptidase and homologous human aspartic proteases reveals opposite topology of catalytic domains compared with presenilins. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:50790–50798. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407898200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim J, Schekman R. The ins and outs of presenilin 1 membrane topology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:905–906. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307297101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim SH, Lah JJ, Thinakaran G, Levey A, Sisodia SS. Subcellular localization of presenilins: association with a unique membrane pool in cultured cells. Neurobiol Dis. 2000;7:99–117. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1999.0280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lau KF, Howlett DR, Kesavapany S, Standen CL, Dingwall C, McLoughlin DM, Miller CC. Cyclin-dependent kinase-5/p35 phosphorylates Presenilin 1 to regulate carboxy-terminal fragment stability. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2002;20:13–20. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2002.1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lehmann S, Chiesa R, Harris DA. Evidence for a six-transmembrane domain structure of presenilin 1. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:12047–12051. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.18.12047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li X, Greenwald I. Membrane topology of the C. elegans SEL-12 presenilin. Neuron. 1996;17:1015–1021. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80231-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li X, Greenwald I. Additional evidence for an eight-transmembrane-domain topology for Caenorhabditis elegans and human presenilins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:7109–7114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.7109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luo WJ, Wang H, Li H, Kim BS, Shah S, Lee HJ, Thinakaran G, Kim TW, Yu G, Xu H. PEN-2 and APH-1 coordinately regulate proteolytic processing of presenilin 1. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:7850–7854. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200648200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakai T, Yamasaki A, Sakaguchi M, Kosaka K, Mihara K, Amaya Y, Miura S. Membrane topology of Alzheimer's disease-related presenilin 1. Evidence for the existence of a molecular species with a seven membrane-spanning and one membrane-embedded structure. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:23647–23658. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.33.23647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Podlisny MB, Citron M, Amarante P, Sherrington R, Xia W, Zhang J, Diehl T, Levesque G, Fraser P, Haass C, Koo EH, Seubert P, St George-Hyslop P, Teplow DB, Selkoe DJ. Presenilin proteins undergo heterogeneous endoproteolysis between Thr291 and Ala299 and occur as stable N- and C-terminal fragments in normal and Alzheimer brain tissue. Neurobiol Dis. 1997;3:325–337. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1997.0129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwarzman AL, Singh N, Tsiper M, Gregori L, Dranovsky A, Vitek MP, Glabe CG, St George-Hyslop PH, Goldgaber D. Endogenous presenilin 1 redistributes to the surface of lamellipodia upon adhesion of Jurkat cells to a collagen matrix. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:7932–7937. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.7932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Selkoe DJ. Alzheimer's disease: genes, proteins, and therapy. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:741–766. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sherrington R, Rogaev EI, Liang Y, Rogaeva EA, Levesque G, Ikeda M, Chi H, Lin C, Li G, Holman K. Cloning of a gene bearing missense mutations in early-onset familial Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 1995;375:754–760. doi: 10.1038/375754a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takasugi N, Tomita T, Hayashi I, Tsuruoka M, Niimura M, Takahashi Y, Thinakaran G, Iwatsubo T. The role of presenilin cofactors in the gamma-secretase complex. Nature. 2003;422:438–441. doi: 10.1038/nature01506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van GG, Annaert W. Amyloid, presenilins, and Alzheimer's disease. Neuroscientist. 2003;9:117–126. doi: 10.1177/1073858403252227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walter J, Capell A, Grunberg J, Pesold B, Schindzielorz A, Prior R, Podlisny MB, Fraser P, Hyslop PS, Selkoe DJ, Haass C. The Alzheimer's disease-associated presenilins are differentially phosphorylated proteins located predominantly within the endoplasmic reticulum. Mol Med. 1996;2:673–691. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xia X, Wang P, Sun X, Soriano S, Shum WK, Yamaguchi H, Trumbauer ME, Takashima A, Koo EH, Zheng H. The aspartate-257 of presenilin 1 is indispensable for mouse development and production of beta-amyloid peptides through beta-catenin-independent mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:8760–8765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.132045399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang Z, Nadeau P, Song W, Donoviel D, Yuan M, Bernstein A, Yankner BA. Presenilins are required for gamma-secretase cleavage of beta-APP and transmembrane cleavage of Notch-1. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:463–465. doi: 10.1038/35017108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]