Abstract

Calmodulin-like neuronal Ca2+-binding proteins (NCBPs) are expressed primarily in neurons and contain a combination of four functional and nonfunctional EF-hand Ca2+-binding motifs. The guanylate cyclase-activating proteins 1–3 (GCAP1–3), the best characterized subgroup of NCBPs, function in the regulation of transmembrane guanylate cyclases 1–2 (GC1–2). The pairing of GCAPs and GCs in vivo depends on cell expression. Therefore, we investigated the expression of these genes in retina using in situ hybridization and immunocytochemistry. Our results demonstrate that GCAP1, GCAP2, GC1 and GC2 are expressed in human rod and cone photoreceptors, while GCAP3 is expressed exclusively in cones. As a consequence of extensive modification, the GCAP3 gene is not expressed in mouse retina. However, this lack of evolutionary conservation appears to be restricted to only some species as we cloned all three GCAPs from teleost (zebrafish) retina and localized them to rod cells, short single cones (GCAP1–2), and all subtypes of cones (GCAP3). Furthermore, sequence comparisons and evolutionary trace analysis coupled with functional testing of the different GCAPs allowed us to identify the key conserved residues that are critical for GCAP structure and function, and to define class-specific residues for the NCBP subfamilies.

Keywords: Ca+-binding proteins, cone photoreceptors, guanylate cyclase-activating proteins, guanylate cyclase, phosphotransduction, rod photoreceptors

Introduction

Ca2+-binding proteins from the calmodulin (CaM) superfamily, termed GCAPs, are involved in the regulation of photoreceptor GC (Polans et al., 1996). GCAPs stimulate GC1 and/or GC2 in low [Ca2+]free, and this regulation is responsible, in part, for modulating the sensitivity of photoreceptor cells and extending their operation through a broad range of light intensities (Mendez et al., 2001). Two proteins, GCAP1 and GCAP2, which share only ≈50% homology were discovered initially (reviewed in Polans et al., 1996). More recently, we reported the presence of a new retina-specific GCAP, termed GCAP3 (Haeseleer et al., 1999), and GCIP (Li et al., 1998). For detailed understanding of phototransduction, the pairing of GCAPs with GCs is of great importance, however, it remains unclear. In situ hybridization with short GCAP1 RNA probes showed the transcript abundantly present in cone myoid regions and, to a lesser degree, in rod inner segments in human and bovine retina (Palczewski et al., 1994; Subbaraya et al., 1994). The intensity of GCAP1's immunoreactivity was strong in cone outer segments for all mammalian species tested but weaker in rod outer segments (ROS) (Gorczyca et al., 1995), particularly in primates (Kachi et al., 1999), cats (Cuenca et al., 1998), and mouse retina (Cuenca et al., 1998; Howes et al, 1998).

Initially, GCAP2 was localized in rod photoreceptors (Dizhoor et al, 1995). However, in subsequent experiments, we and colleagues localized GCAP2 to the cone inner segments, somata, and synaptic terminals and, less significantly, to the rod inner segments and inner retinal neurons. A number of interesting differences were observed between species (Otto-Bruc et al., 1997; Cuenca et al., 1998; Kachi et al., 1999). In mouse retina, GCAP2 was nearly undetectable in cones (Howes et al., 1998). All of these studies were carried out initially without knowledge of the existence of GCAP3 (Haeseleer et al., 1999), whose expression pattern and localization had not yet been reported.

Mammalian photoreceptors express two retina-specific membrane-associated types of GCs. GC1 immunoreactivity in human retina was detected in the photoreceptor outer segments, primarily in cones (Dizhoor et al, 1994; Liu et al., 1994). Although radioisotopic in situ hybridization localized human GC2 mRNA to photoreceptor inner segments and outer nuclear layer (Lowe et al., 1995), a higher resolution technique is required to determine the expression in rods and cones. Electron microscopy of rat retina showed that both cyclases are located in the rods (Yang & Garbers, 1997). However, because of the low abundance of cones in rat retina, localization of GCs to cones was not characterized.

The identification of a number of Ca2+-binding proteins that interact with multiple GCs suggests a complex regulation of photoreceptor GCs. Therefore, in this study we investigated the expression of GCAPs and GCs in vertebrate retinas using nonisotopic in situ hybridization supported by immunocytochemical techniques. Using evolutionary trace analysis (ET), we also identified the key conserved residues that are critical for GCAP structure and function, and we defined class-specific residues for the NCBP subfamilies.

Materials and methods

SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting

SDS-PAGE was performed using 12.5% polyacrylamide gels (Laemmli, 1970). The protein electrotransfer onto immobilon-P (Millipore, Bedford, Massachusetts, USA) was carried out with a Hoeffer mini-gel system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech. Piscataway, New Jersey, USA). For immunoblotting, the membrane was blocked with 3% BSA in phosphate-buffered saline (PBST; 136 mm NaCl, 11.4 mm sodium phosphate, 0.1% Triton X-100, pH 7.4) and incubated for 1.5 h with anti-GCAP3-antibody at a dilution of 1 : 2000. A secondary antibody conjugated with alkaline-phosphatase (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin, USA) was used at a dilution of 1 : 5000. Antibody binding was detected by incubation with NBT/BCIP (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin, USA).

Cloning of zebrafish GCAP1, GCAP2 and GCAP3 cDNAs

Based on the expressed sequence tag clones (e.g. BG307360, BG305035, BG305375 deposited by Stephen L. Johnson, Washington University School of Medicine), zebrafish GCAP1 coding region was amplified from a λZAPII zebrafish retina cDNA library (gift of Dr David Hyde, Notre Dame) with sense primer ZG1-S (5′-ATGGGCAATTCAACGGGC), antisense primer ZG1-A (5′-CGAGCCCCTGCTACAAACTC) using standard PCR conditions with Taq polymerase. The 5′-untranslated region of GCAP1 was amplified with ZG1-A and universal primer T3. The 3′-untranslated region of GCAP1 was amplified with ZG1-S and T7. GCAP2 and GCAP3 were amplified using similar approaches. The specific primers are ZG2-S (5′-ATGGGTCAGCGGCTCAGC) and ZG2-A (5′–GCCATGGGCGCCAAGGCATCC) for amplifying GCAP2; ZG3-A (5′–ACGTGTGTGAGGTCCATC) and ZG3-S (5′–GCCATGGGCGCCAAGGCATCC) for amplifying GCAP3. cDNA fragments of GCAPs were cloned into PCRII-TOPO vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California, USA).

Identification of mouse GCAP3 gene

Based on the sequence fragments (Accession numbers: 544850, 13770026, 20684911, 14011120) found from the mouse trace archives database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/mmtrace.html), the mouse GCAP3 genomic fragment, including exon 1, was amplified from mouse genomic DNA with sense primer mG3–1S (5′–ACCACACATTCAAATACATGAGTC) and antisense primer mG3–1 A (5′-GACGTGAGTTACAAATCAAGTTG) using standard PCR conditions with the Expand™ High Fidelity PCR System (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA). DNA fragments of mGCAP3 genes were cloned into PCRII-TOPO vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California, USA) and sequenced. Additional mouse genomic fragment including partial GCAP3 exon 3 and intron C, was amplified with sense primer mG2-3S (5′-GTTGAATGTATTCTTGGGTACT) and antisense primer mG3-3 A (5′-GTCTATGTCAATATTATGAAGC) based on trace files (ml2Cc274f04.p1ca and ml2C-c274f04.p1c from http://trace.ensembl.org/ and deposited by the Sanger Centre).

Tissue preparation for immunocytochemistry and in situ hybridization

The zebra fish were anesthetized with 0.02% methane tricaine sulfate, as approved by the Animal Care Committee at the University of Washington, and killed. Anterior segments of zebrafish eyes were removed and then eyecups were fixed for 4 h in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1% phosphate buffer (PB; 100 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.4). A human eyecup was fixed at 4 h postmortem in 4% paraformaldehyde for 12 h. Retinal tissues were infiltrated with 20% sucrose in PB, and then embedded in 33% OCT compound (Sakura, Tokyo, Japan) diluted with 20% sucrose in PB. Zebrafish and human retinas were sectioned at 5 μm and 12 μm, respectively.

Immunocytochemistry

Human GCAP3 (hGCAP3) was expressed and purified as described previously (Haeseleer et al., 1999). Purified hGCAP3 was used to immunize a mouse to obtain an anti-GCAP3 antiserum. To block nonspecific labelling, human retinal sections were incubated in 1.5% normal goat serum in PBST for 15 min at room temperature. Sections were incubated overnight at 4 °C in purified anti-GCAP3 polyclonal antibodies in PBST. Controls were prepared by absorbing the anti-GCAP3 antibodies with an excess amount of GCAP3 (1 μg/mL) or GCAP1/2 (2 μg/mL). Sections were rinsed in PBST and incubated with indocarbocyanine (Cy3)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG. Then, sections were rinsed in PBST, mounted in 50 μL 2% 1,4-diazabicyclo-2,2,2-octane in 90% glycerol to retard photobleaching. Sections were analyzed under an episcopic-fluorescent microscope (Nikon, Melville, New York, USA). Digital images were captured with a digital camera (Diagnostic Instruments; Sterling Heights, MI).

In situ hybridization

cDNA fragments of GCAPs and GCs were cloned into PCRII-TOPO vector or pGEM-3Zf(+) plasmid vectors, and linearized with appropriate endonucleases. Antisense and sense RNA probes (500–700 bases in length for GCAPs and GC2, 1.6 kb for GC1) were synthesized by run-off transcription from the SP6 or T7 promoter with digoxigenin-UTP, as recommended in the manufacture's protocol (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA). In situ hybridization technique of retinal sections are as described previously (Barthel & Raymond, 2000), with modifications. Sections stored at −80 °C were thawed, rehydrated, and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min. After fixation, sections were washed three times in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then digested with proteinase K (5 μg/mL) for 10–15 min. After digestion, sections were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min, washed three times in PBS and treated with 0.25% acetic anhydride in 0.1 m triethanolamine. After washing with 1 × SSC, sections were hybridized at 65 °C for 16 h with 0.1 μg/mL RNA probes in the hybridization solution (Rosen & Beddington, 1994). After hybridization, the slides were washed in 1 × SSC at room temperature for 0.5 h, then in 50% formamide in 2 × SSC at 65 °C for 2 h, and then treated with RNAse A (5 μg/mL) at 37 °C for 1 h to digest unbound probe. To eliminate the endogenous alkaline phosphatase (AP) activity, sections were treated with 20 mm HCl for 5 min, and then blocked with 0.5% blocking solution (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA) in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST; 25 mm Tris, 137 mm NaCl, 3 mm KCl, and 0.1% Tween 20) at room temperature for 0.5 h. Sections were incubated at 4 °C for 16 h with anti-digoxigenin antibodies conjugated with AP. Hybridization signal was detected by incubation with NBT–BCIP (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin, USA) for 4–48 h at room temperature. Sections were rinsed with dH2O. For double labelling, after colouring reactions sections were incubated with 1.5% normal goat serum in PBST for 15 min at room temperature and then incubated with antibodies to human red/green opsin (generated against N-terminal peptide in human red/green cone opsin; a gift from J. Saari, University of Washington) or human blue cone opsin (JH455 serum, specific for the C-terminus of human blue opsin; a gift from Jeremy Nathans, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine). Sections were then rinsed in PBST and incubated with indocarbocyanine (Cy3)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG. Sections were rinsed in PBS, mounted in 50 μL 2% 1,4-diazabicyclo-2,2,2-octane in 90% glycerol to retard photobleaching. Sections were analyzed under fluorescent microscope. Fluorescent images and transparent images were imported into Adobe Photoshop 5.0 and merged images were generated.

RNA dot blots

Unlabelled sense transcripts were generated from cloned cDNAs following the manufacturer's specifications. Sense transcripts, 0.1 ng, 1 ng and 10 ng were blotted onto Hybond NX membrane (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech. Piscataway, New Jersey, USA) and bound by cross-linking. High stringency hybridization was carried out at 65 °C for 16 h in the hybridization solution. Digoxygenin-labelled cRNA probes were diluted to 100 ng/mL. All procedures for posthybridization and detection were as described for in situ hybridization.

Expression of GCAP3 and GC assay

The entire coding region of zGCAP3 was cloned into pET28a (Novagen, Madison, Wisconsin, USA), and expressed in Bl21(DE3)LysS strain. Bacterially expressed GCAP3-His6 was purified using Ni-NTA agarose (Qiagen, Valencia, California, USA). The GC assay was performed using [α-32P] GTP and washed ROS (Gorczyca et al., 1995). Ca2+ was calculated using the Chelator 1.00 (Schoenmakers et al., 1992) and adjusted in Ca2+ titration experiments to a higher concentration by increasing the amount of CaCl2.

Calculation of the phylogenetic tree

A phylogenetic tree was constructed from the aligned sequences using the ClustalW program. Evolutionary distances of the sequences (k) were estimated using the proportion of different amino acids between the two sequences (p), with correction for multiple substitutions of k = −ln(1 − p − 0.2 p2) (Kimura, 1991) by Protdist of phylip (version 3.573). The phylogenetic tree was constructed by the neighbour-joining method using the Neighbour program of phylip (version 3.573). Bootstrap resamplings were performed by Seqboot program of phylip (version 3.573).

Evolutionary trace analysis of NCBP and GCAP families

Evolutionary trace analysis (ET) was performed as previously described (Lichtarge et al., 1996; Sowa et al., 2001). Briefly, ET uses the sequence identity tree (dendrogram) produced from the multiple sequence alignment (MSA) of a protein family to divide the family into subgroups based on evolutionary relatedness. The number of subgroups can be varied and referred to as the rank of the trace. Residue positions that have an identical residue within each of the subgroups, but whose identity varies among the subgroups, are termed class-specific. These class-specific residues are considered to be important for delineating the functional specificities of the different subgroups and can provide information for designing targeted mutagenesis experiments for separation of function (Sowa et al., 2001). The amino-acid sequence of bovine GCAP2 was used in a BLAST search to retrieve similar sequences. Redundant and partial sequences were removed from the BLAST output and the remaining 106 unique sequences were aligned using the Genetic Computer Group (GCG, Wisconsin, USA) program PILEUP with the default matrix. The 33 members of the GCAP subfamily were extracted from this MSA, realigned, and the resulting MSA was used as the input for the ET of the GCAP family. The results were mapped onto the structure of Ca2+-bound bovine GCAP2. Rank 5 was chosen for the final analysis because this choice partitioned the dendrogram into individual GCAP subfamilies and GCIP. For the ET of the entire NCBP family, the initial MSA was used, including the GCAP family. Rank 30 was chosen for the analysis as above this rank, random signals begin to dominate the output At this rank, the major subgroups are GCAP1, GCAP2, GCAP3, GCIP, calsenilin, recoverin, visinin, neurocalcin, and frequenin, with additional groups formed either by single sequences associated with each of these groups or divisions within these groups.

Results

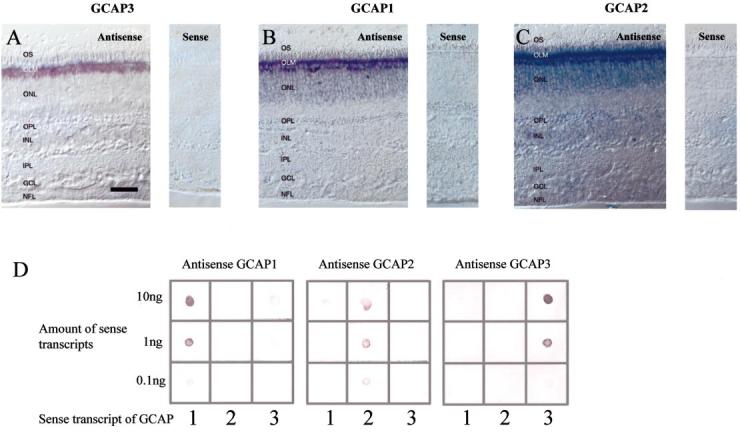

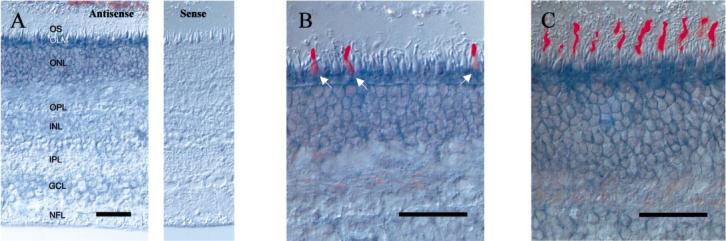

In situ localization of GCAP3 mRNA in human retina

The distribution of human GCAPs (hGCAPs) was investigated by nonisotopic in situ hybridization. The digoxigenin-conjugated GCAP3 antisense RNA probe hybridized only to the cells proximal to outer limiting membrane, and the signals were observed only in cone inner segments and cell bodies (Fig. 1A, left). GCAP3 sense RNA probe control did not produce a hybridization signal (Fig. 1A, right). For GCAP1 and GCAP2, the hybridization signal employing antisense RNA probe was observed throughout the outer nuclear layer (Fig. 1B and C left, respectively) with the most intense labelling observed in the cone inner segment and cell bodies. For GCAP2, weak signals were observed in a subpopulation of inner nuclear neurons and ganglion cells.

Fig. 1.

In situ hybridization of human GCAPs and specificity of hybridization. (A) In situ hybridization of GCAP3 transcripts using antisense (left) and sense (right) RNA. The strong signal is in cone inner segment and cell bodies. No signal is observed in rod photoreceptors. Bar, 50 μm (A–C). (B) In situ hybridization of GCAP1 transcripts using antisense (left) and sense (right) RNA. The strongest signal is in cone inner segment and cell bodies. Rod inner segments and cell bodies are also labelled. (C) In situ hybridization of GCAP2 transcripts using antisense (left) and sense (right) RNA. The strongest signal is in cone inner segment and cell bodies. Rod inner segments, cell bodies and inner retinal neurons are also labelled. (D) RNA dot blots of human GCAP transcripts. Different amounts of GCAP sense transcripts (10, 1, and 0.1 ng) were blotted on Hybond-NX membrane. GCAP1 cRNA probe hybridized specifically to GCAP1 sense RNA blotted on left column (left). GCAP2 hybridized to GCAP2 sense transcripts blotted on middle column. GCAP3 antisense probe hybridized to GCAP3 sense transcripts blotted on right column. Abbreviations: OS, photoreceptor outer segments; IS, photoreceptor inner segments; ONL, outer nuclear layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; IPL, inner plexiform layer; GCL, ganglion cell layer; and NFL, nerve-fibre layer.

RNA dot blots were employed to test the specificity of RNA–RNA hybridization. Unlabelled sense transcript of GCAPs were blotted onto hybond NX membrane and hybridized under the identical condition as in situ hybridization, using GCAP antisense probes. Each GCAP antisense probe hybridized specifically to the corresponding GCAP sense probe (Fig. 1D). These results indicate that the hybridization conditions employed here are GCAP subclass specific.

To specify the subtype of GCAP3-positive cones, sections were double stained by in situ hybridization with the GCAP3 antisense probe and immunocytochemistry, using anti-blue and anti-red/green cone opsins. GCAP3 mRNA is expressed in cones that are immunoreactive with anti-blue (Fig. 2A) and anti-red/green opsin (Fig. 2B), whereas GCAP1 and GCAP2 are present in both rods and cones.

Fig. 2.

Double labelling with DIG labelled GCAP3 cRNA (blue) with anti-cone opsins antibodies (red). (A) Double labelling with anti-blue cone opsin. Anti-blue cone opsin labels cone photoreceptors which hybridizes GCAP3 cRNA probe (blue). (B) Double labelling with anti-red/green cone opsin. Red/green cones are labelled with GCAP3 cRNA. Scale bar, 50 μm

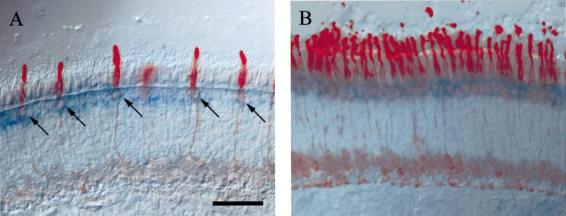

Subcellular localization of GCAP3

To investigate the specificity of the anti-GCAP3 antiserum, reactivity of GCAP1/GCAP2/GCAP3 was tested by immunoblotting. Anti-GCAP3 antiserum recognized recombinant hGCAP3 (Fig. 3A). Immunofluorescence microscopy of human retina revealed that GCAP3 was present in a limited number of photoreceptor outer segments (Fig. 3B). By morphological criteria, hGCAP3 appears to be present in cone outer segments and not ROS (Fig. 3C). Importantly, this result is consistent with the in situ hybridization results. The immunolabelling was abolished by preincubation with hGCAP3 (Fig. 3D), but was not altered by incubation with hGCAP1/hGCAP2 (Fig. 3E).

Fig. 3.

Immunolocalization of GCAP3 in human retina. (A) Specificity of anti-GCAP3 antibodies. Lane 1, purified GCAP1 (0.1 μg); lane 2 purified GCAP2 (0.1 μg); lane 3 purified GCAP3 (0.1 μg). Top, SDS-polyacrylamide gel stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250. Bottom, reactivity of anti-GCAP3 analyzed by Western blotting. The arrows indicate dimeric forms of GCAP3 seen in SDS-PAGE and on immunoblotting. The dimeric form of GCAP3 was confirmed using separate immunoblot and a generic antibody, G2, which recognizes all GCAPs. (B–D) Immunofluorescence localization of GCAP3 in human retina. (B) GCAP3 immunolabelling is specific to cone outer segments. (C) Fluorescent image from B was merged with a transparent image captured by Nomarski/DIC optics. (D) Addition of purified GCAP3 (1 μg/mL) abolishes GCAP3 immunoreactivity. (E) Addition of purified GCAP1 and GCAP2 (2 μg/mL each) produces minimal decrease in GCAP3 immunoreactivity. *rod outer segments; white arrow, cone cells. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Localization of GCs in human retina

In situ hybridization was used to determine the cell type specific expression pattern of photoreceptor GCs. cDNA, corresponding to the low-homology intracellular domain (≈1.6 kb in length), was used as a template for the probe. GC1 signals (purple) were strongest in the cone inner segments and were also intense in the rod inner segments and cell bodies (Fig. 4A, left). Weak signals were observed in the inner nuclear and ganglion cell layers (Fig. 4A, left) and no signal was observed for the sense probe (Fig. 4A, right). This localization of GC1 result is consistent with previous immunocytochemical reports (Dizhoor et al., 1994; Liu et al., 1994). Isotopic in situ hybridization showed exclusive expression of GC1 mRNA in the photoreceptor layer of monkey retina (Shyjan et al., 1992), yet as a consequence of low resolution and high background of this method, precise localization of the photoreceptor cell-type was not possible. To determine GC1 cell-specific expression, an immunohistochemical/in situ hybridization double staining technique with cone-specific antibodies was employed. Double staining with anti-blue opsin antibodies (red signal) shows that GC1 is expressed in blue cones (Fig. 4B). Double labelling with anti-red/green opsin antibodies (red signal) shows that GC1 is expressed in red/green cones (Fig. 4C). These results indicate that GC1 is expressed in all classes of cones.

Fig. 4.

In situ hybridization of human GC1. (A) In situ hybridization of GC1 transcripts using antisense (left) and sense (right) RNA. The strongest signal is in cone inner segment and cell bodies. Rod inner segments and cell bodies were also strongly labelled. Inner nuclear neurons and ganglion cells are weakly labelled. (B) Double labelling with anti-blue cone opsin. Anti-blue cone opsin labels cone photoreceptors (red) which hybridizes GC1 cRNA probe (blue). (C) Double labelling with anti-red/green cone opsin. Red/green cones (red) are labelled with GC1 cRNA (blue). White arrows, blue cones. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Using a similar method, in situ hybridization of GC2 was carried out using cDNA corresponding to the extracellular domain (≈0.7 kb in length) to produce sense and antisense RNA probes. The digoxigenin labelled antisense GC2 probe showed intense labelling in cone photoreceptors, and weak labelling in rod photoreceptors (Fig. 5A). GC2 is expressed in blue cones (Fig. 5B) and red/green cones (Fig. 5C), as shown by labelling using in situ hybridization and immunocytochemistry. A weaker signal was observed for GC2, compared to GC1, indicating that GC1 may be expressed at higher levels than GC2. These results suggest that GC1 and GC2 are coexpressed in all cones and rods in human retina.

Fig. 5.

In situ hybridization of human GC2. (A) In situ hybridization of GC2 transcripts using antisense (left) and sense (right) RNA. Strong signal is observed in cone inner segments. Rod inner segments and cell bodies were weakly labelled. (B) Double labelling with anti-blue cone opsin. Anti-blue cone opsin labels cone photoreceptors (red) which hybridizes with GC2 cRNA probe (blue). (C) Double labelling with anti-red/green cone opsin. Red/green cones (red) are labelled with GC2 cRNA (blue). Black arrows, blue cones. Scale bar, 50 μm.

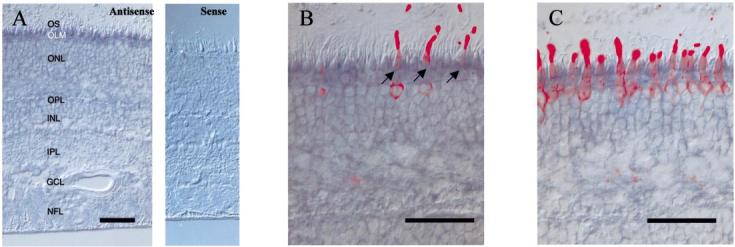

Identification of mouse GCAP3 genomic sequence

Several genomic fragments with homology to the human GCAP3 genomic sequence were found by searching the mouse trace database using megablast search program (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/mmtrace.html). Primers were designed based on these mouse traces (544850, 13770026, 20684911, 14011120, ml2C-c274f04.p1ca and ml2C-c274f04.p1c) and used to amplify mouse GCAP3 genomic DNA using mouse genomic DNA as a template. Two separate DNA fragments that are homologous to human GCAP3 gene were amplified. These genomic fragments consist of 838 and 308 base pairs, respectively. The BlastN program was utilized to compare these sequences with the human GCAP3 genomic sequence (accession numbers: AC016948, AF109998, and AF110000). Human and mouse GCAP3 genomic sequences around exon 1 were aligned (Fig. 6A). This region showed 67% nucleotide identity. Exon 1, especially, having the greatest homology (72%). In mouse, exon 1 of GCAP3 contains several deletions that create three frame shifts. Functional exon–intron junction sites were not found. Figure 6B shows the comparison of intron A sequences downstream of exon 1. This region shows even higher homology (83% 279/334 nucleotides) than exon 1. The comparison of partial intron C and exon 3 sequences (Fig. 6C) reveals high identity (69% 196/282 nucleotides) in this region of the gene and even higher identity in the exon 3 area (75% 61/81 nucleotides). These results indicate that these mouse genomic sequences are highly homologous to the human GCAP3 gene. We were unable to identify other genomic sequences closely related to human GCAP3 exon 1 and exon 3 in the mouse.

Fig. 6.

Partial gene sequence exon/intron junction of mGCAP3 compared to hGCAP3 gene. Vertical bars indicate the positions of identical residues. Exons are shown in capital letters. (A) Comparison of mouse and human GCAP3 genomic sequence around exon 1. In this region 67% of nucleotides (195/288 nucleotides with 9 gaps) were identical and 72% of nucleotides (128/177 nucleotides with 8 gaps) are identical in exon 1. (B) Comparison of mouse and human GCAP3 genomic sequence of intron A. In this area, 83% of nucleotides (279/334 nucleotides with three gaps) are identical. Note that sequence of A. and B. is from one contiguous genomic fragment. (C) Comparison of mouse and human GCAP3 genomic sequence including partial exon 3 region. In this region, 69% of nucleotides were identical (196/282 nucleotides with 21 gaps). Especially high identity (75% 61/81 nucleotides with 1 gap) was observed in exon 3 region. (D) Comparison of translated sequence. Frame shift sequences are translated into X residues. Arrows indicate positions of frame shifts due to deletion in mGCAP3 gene. The nonfunctional EF1 hand in human GCAP3 is boxed by broken line. The EF hand motifs (EF2 and 4) in human GCAP3 are boxed.

Mouse exon 1 and partial exon 3 sequences were conceptually translated and aligned with the amino-acid sequence of human GCAP3. Translated exon 1 sequences showed low identity (46% 32/69 amino acids) despite high identity at the nucleotide level. The translated mouse exon 1 sequence does not show a potential myristoylation site or functional EF-hands, and has three stop codons and three frame shifts (Fig. 6D, arrows). Translated mouse exon 3 exhibits high identity (63% 17/27 amino acids) with human GCAP3 exon 3 amino-acid sequence, although one frame shift, which will cause a nonfunctional translation, was observed. These results indicate that mouse GCAP3 gene is a nonfunctional pseudogene, which presumably arose originally by duplication of genomic DNA (in contrast to pseudogenes arising by retrotransposition). The mouse GCAP3 gene may have originally been functional, but low amino acid conservation suggests that this gene became neutralized to a pseudogene during evolution and has diverged without functional constraints (reviewed in ref. Mighell et al., 2000).

Cloning of zebrafish GCAP cDNAs

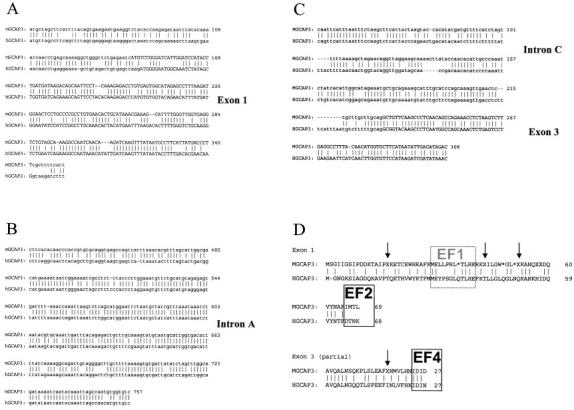

Several expressed sequence tags (ESTs) with homology to human GCAPs were found by searching databases with human GCAP3 sequence using the TBlastx program (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/). Primers based on these ESTs were used to amplify zebrafish GCAPs by PCR using zebrafish retina cDNA as a template. Three complete cDNAs encoding zGCAP1, zGCAP2, and zGCAP3 were amplified. The zGCAP3 cDNA encodes a protein of 188 amino acids with a calculated molecular mass of 21 868 Da. Correspondingly, the zGCAP1 and zGCAP2 cDNA encode proteins of 189 amino acids (21 874 Da) and 197 amino acids (22 956 Da), respectively. The strongest homology was observed within the central region of the protein that encompassed functional EF2 and EF3 Ca2+- binding motifs (Fig. 7). The most divergent regions in the amino-acid sequence are located between EF3, the functional EF4 motif, and in the C-terminal region. The N-terminus of mammalian GCAPs was implicated to be crucial for both GC stimulation (Palczewski et al., 1994; Li et al., 2001) and the conserved N-myristoylation. Zebrafish GCAPs contain a consensus myristoylation signal sequence (MGxxxS/E.), where Gly2 is the site of this post-translational modification. The residues around the nonfunctional EF1 motif contains conserved residues, such as W, Y, F, E and P, S, G (Fig. 7) in all GCAPs sequenced so far.

Fig. 7.

Amino-acid sequence alignment of Homo sapiens (prefix h) and Danio rerio (prefix z) GCAPs. The three EF hand motifs (EF2–4) representing high affinity Ca2+ binding sites are boxed. The nonfunctional EF1 hand is boxed by a broken line. Residues conserved in all GCAPs shown here are printed white on black. Residues not uniformly conserved are shaded. Arrows indicate the positions of introns in the three human GCAP genes whose exon/intron arrangement is identical (Surguchov et al., 1996; Haeseleer et al., 1999).

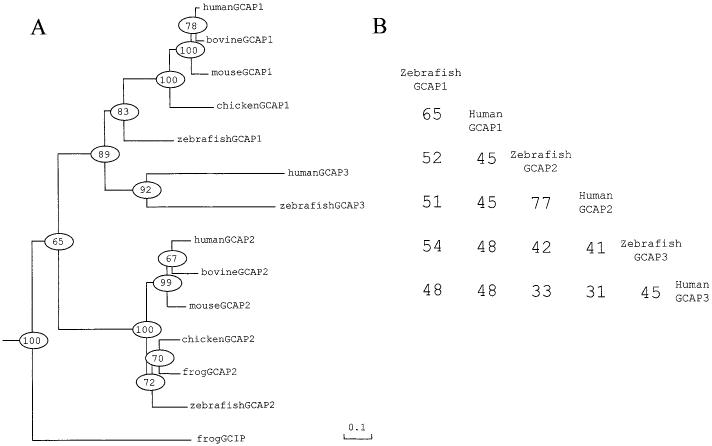

A third subfamily of GCAPs: GCAP3s

A neighbour joining (NJ)-tree was calculated from vertebrate GCAPs and GCIP, using vertebrate recoverin and visinin as out-groups (Fig. 8A). The ancestral gene first appears to diverge into GCIP and GCAP subfamilies, and then GCAPs further branched out into three subtypes, GCAP1, GCAP2, and GCAP3. In spite of low identity between human and zebrafish GCAP3s (45%) (Fig. 8B), the tree shows the group of GCAP3s with high clustering probability (92%). Therefore, we concluded that vertebrate GCAP3 is a third family of GCAPs. Each subtype of GCAPs seems to have appeared before teleost-tetrapod divergence. An exhaustive search of the invertebrate database, including Drosophilae, did not identify the GCAP family of regulators. It is speculated that the GCAP gene diverged after vertebrate-arthropod divergence, or is disrupted in other invertebrates. The phylogenetic analysis suggests that amino-acid substitution rates (k) are lower in GCAP1 and GCAP2, than in GCAP3. The k-value between zebrafish and human GCAP3 is 0.95, approximately double the k-value between zebrafish and human GCAP1 (0.50), and three times higher than the k-value between zebrafish and human GCAP2 (0.29). This variation of k-values among GCAPs may be because of a difference in the functional constraints. Together, these analyses suggest GCAP3s represent a unique subisoform family of proteins, different from GCAP1s and GCAP2s.

Fig. 8.

A phylogenetic and amino acid identities of GCAPs. (A) A phylogenetic tree calculated from the amino-acid sequences of GCAPs. Numbers indicate clustering percentage obtained from 1000 bootstrap resamplings. Bar indicates 10% replacement of an amino acid per site (k = 0.1; see Material and methods). (B) The amino acid identities between GCAPs from ClustalW alignment. Gaps were taken as the same amino acid. Sequence data used in the present analyses were taken from GenBank, EMBL, SWISS-PROT, NCBI databases, except for mouse GCAP2 (Howes et al., 1998). Accession numbers are as follows: human GCAP1 (11417667), bovine GCAP1 (1169873), mouse GCAP1 (1169875), chicken GCAP1 (5713275), human GCAP3 (6226818), human GCAP2 (8928106), bovine GCAP2 (1730238), chicken GCAP2 (5713277), frog GCAP2 (6225434), and frog GCIP (AAC15878).

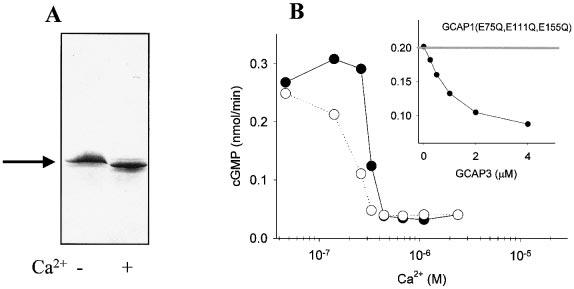

Biochemical properties of zGCAP3

To measure GCAP-mediated GC activation, zebrafish GCAP3 was expressed and purified to apparent homogeneity (Fig. 9A). zGCAP3 displayed a minor mobility change in the presence and absence of Ca2+, as observed for other GCAPs (Palczewski et al., 1994; Gorczyca et al, 1994) (Fig. 9A). In the GC assay, GCAPs display the expected properties, modulating ROS GCs in a Ca2+-dependent manner stimulating at low and inhibiting at high [Ca2+] (Fig. 9B). zGCAP3 competed with constitutively active GCAP1 [GCAP1(E75Q, E111Q, E155Q)] at high [Ca2+], suggesting that the binding site on GC is similar, if not identical, for GCAP1 and zGCAP3. These biochemical data further demonstrate that this Ca2+- binding protein, not only shows sequence relationship to GCAPs, but also shares biochemical properties in stimulating GC, as observed previously for GCAP1 and GCAP2.

Fig. 9.

Characterization of zebrafish GCAP3. (A) Bacterially expressed, purified protein was subjected to SDS-PAGE in the presence and absence of Ca2+. (B) Ca2+ titration of GC activity in washed ROS membranes, in the presence of zGCAP3 (closed circle) and control bGCAP1 (open circle). Inset, competition in 2 μm Ca2+ between indicated concentration of GCAP3 and 3 μm bGCAP1(E75Q,E111Q,E155Q) mutant. The assays were performed in two independent sets of measurements with comparable results.

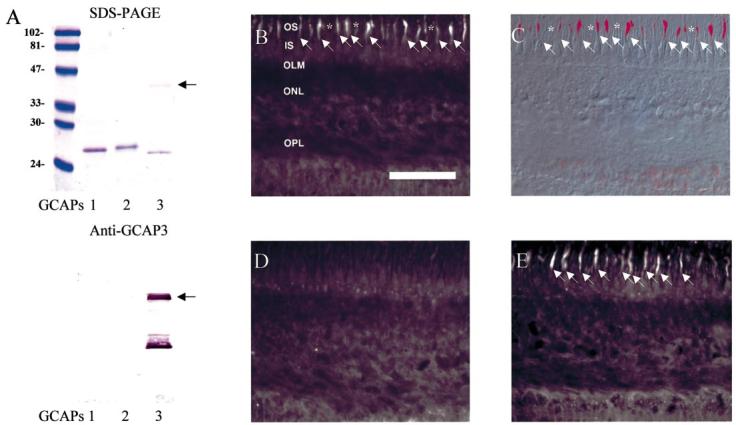

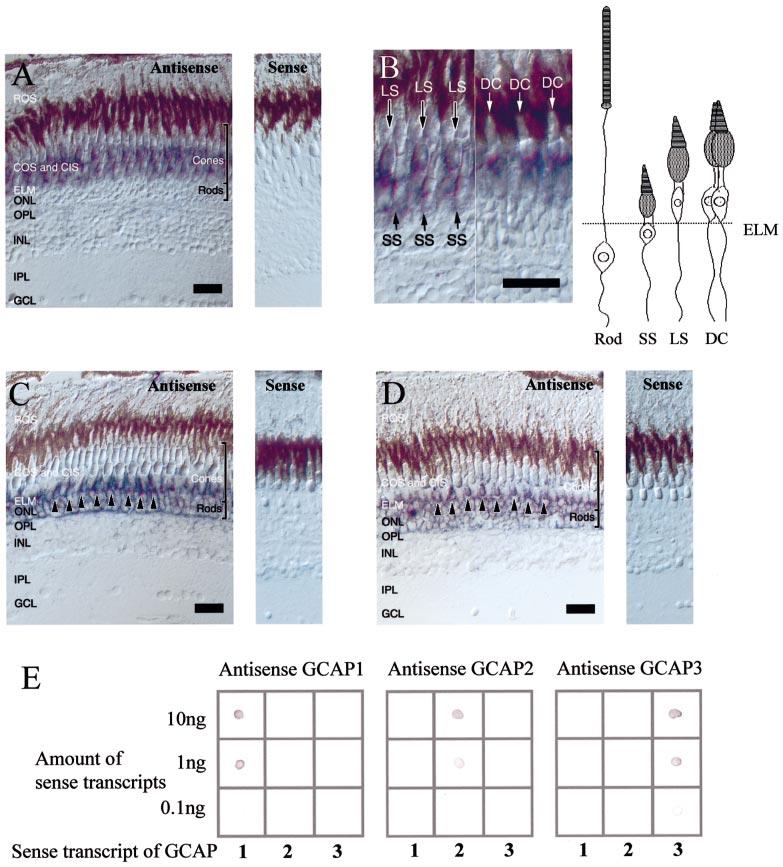

In situ localization of zebrafish GCAP mRNAs

Zebrafish photoreceptor cells are categorized morphologically into five types (Fig. 10B): rods, two different cones from the double cone pairs (DC), long single cones (LS), and short single cones (SS) (Raymond et al., 1993). The nuclei of DC and LS protrude above the external limiting membrane and the nuclei of SS and rods remain below it. The distribution of zebrafish GCAP mRNAs was investigated by in situ hybridization. The digoxigenin labelled zGCAP3 antisense RNA probe hybridized specifically to the myoid region of cone photoreceptors (Fig. 10A, left). Signals were observed in cell bodies of LS, SS and both members of DC (Fig. 10B). Cone cells negative for the zGCAP3 antisense RNA probe were not identified in our experiment. As a control, zGCAP3 sense RNA probe did not show hybridization signals (Fig. 10A, right). These results suggest that zGCAP3 is expressed in all four types of cone photoreceptors, but not in rods. Figure 10C and D shows the localization of zGCAP1 and zGCAP2 mRNAs, respectively. In both cases similar patterns were observed. Hybridization signals were observed only in the photoreceptors whose cell bodies are below the external limiting membrane. Signals were observed in the cell bodies and myoid regions of rods, as well as in the myoids of SS (see arrows in Fig. 10C and D, left). Signals were not observed in DC and LS whose nuclei are beyond the external limiting membrane. SS negative with GCAP1/2 antisense probes were not observed in these sections. Unlike human GCAP2 expression, no staining was observed in inner retinal neurons for zGCAP1 or zGCAP2. As a similar expression pattern and intensity was observed for zGCAP1 and zGCAP2, RNA dot blots were employed to test the specificity of RNA–RNA hybridization. Unlabelled sense transcripts of zGCAPs were blotted onto hybond NX membrane and hybridized under the same condition as in situ hybridization, using GCAP antisense probes. Each zGCAP antisense probe hybridized specifically to corresponding zGCAP sense transcript (Fig. 10E). These results indicate that the hybridization conditions employed here are specific, verifying that zGCAP1 and zGCAP2 are coexpressed in rods and SS, but not in other cone photoreceptors.

Fig. 10.

In situ hybridization of zebrafish GCAPs and specificity of hybridization. (A) In situ hybridization of GCAP3 transcripts using antisense (left) and sense (right) RNA. The strong signal is in cone inner segment. No signal is observed in rod myoid or cell bodies. (B) Localization of GCAP3 mRNA with higher magnification. Signals are observed in short single cones (SS), long single cones (LS), and double cones (DC). (C) In situ hybridization of GCAP1 transcripts using antisense (left) and sense (right) RNA. SS were strongly labelled (arrowheads). Rod myoids and cell bodies are also labelled. (D) In situ hybridization of GCAP2 transcripts using antisense (left) and sense (right) RNA. SS were strongly labelled (arrowheads). Rod myoids and cell bodies are also labelled. Abbreviations: ROS, rod photoreceptor outer segments; COS, cone photoreceptor outer segments; ELM, external limiting membrane; ONL, outer nuclear layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; IPL, inner plexiform layer; and GCL, ganglion cell layer. Scale bar, 20 μm. (E) RNA dot blots of zebrafish GCAP transcripts. Different amounts of GCAP sense transcripts (0.1, 1, and 10 ng) were blotted on Hybond-NX membrane. GCAP1 cRNA probe hybridized specifically to GCAP1 sense RNA blotted on left column (left). GCAP2 hybridized to GCAP2 sense transcripts blotted on middle column (middle). GCAP3 antisense probe hybridized to GCAP3 sense transcripts blotted on right column.

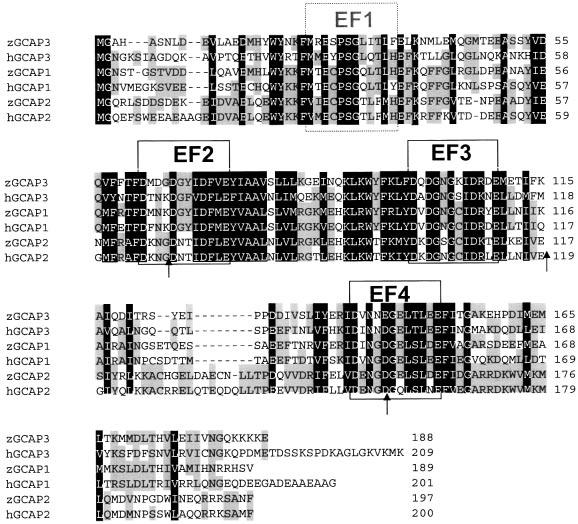

Evolutionary trace analysis of the GCAP family

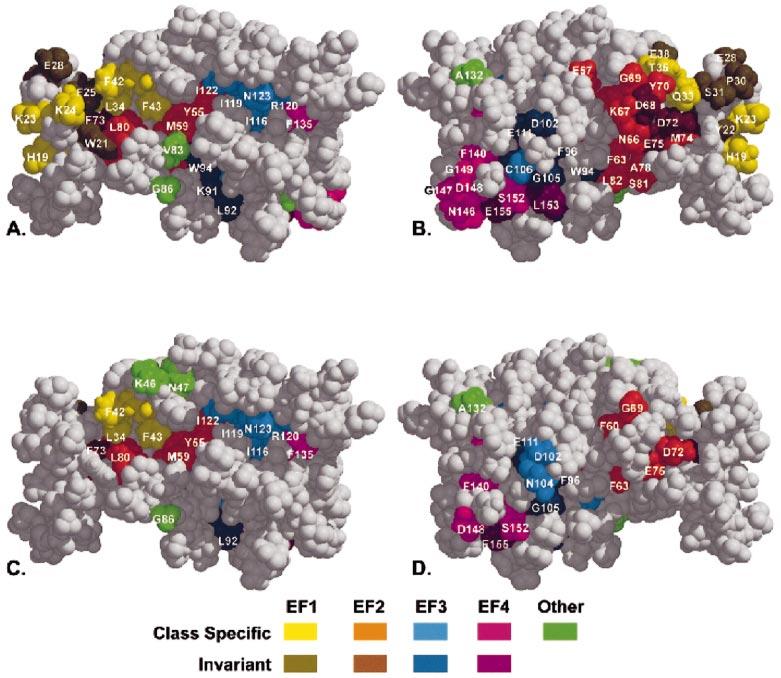

ET analysis was performed on the GCAP family consisting of 33 members. ET uses the sequence identity tree for the family as a means of dividing the multiple sequence alignment into distinct subclasses that are then examined for patterns of amino acid conservation and variation (Lichtarge et al., 1996). Residue positions that have an invariant amino acid within each subclass, but whose identity varies among the subclasses, are termed class-specific and have been shown to impart functional specificity among family members (Sowa et al., 2000). When the GCAP family is divided in such a way that GCAP1, GCAP2, GCAP3, and GCIP form subclasses, class-specific residues emerge on each of the EF-hands and form clusters at multiple sites on the surface (Fig. 11A and B) when mapped onto the Ca2+-bound structure of GCAP2 (Ames et al., 1999). Residue numbers in Fig. 11 and in the discussion below are based on bovine GCAP1.

Fig. 11.

Evolutionary trace analysis of the GCAP and NCBP families. An Evolutionary trace analysis (ET) was performed on both the GCAP family (33 members) and the NCBP family (106 members, including the GCAP subfamily). The results were mapped onto the structure of Ca2+-bound GCAP2 (Ames et al., 1999). EF hands, class specific, and invariant residues are coloured according to the colour table, with numbering and amino acid designation based on bovine GCAP1. Views A and B are rotated 180° about the y-axis with respect to each other as are C and D. (A, B) ET analysis of the GCAP subfamily reveals a large surface cluster of both class specific and invariant residues from EF1 and EF2. This site is much smaller in size for the NCBP trace suggesting that this region is specific for the GCAP subfamily (A vs. C, B vs. D). The stretch of ET-identified surface residues beginning with Phe73 and ending with Phe135 (A vs. C) is found in both the NCBP and the GCAP traces, indicating that this site is important for the functional specificity of the entire NCBP family.

The largest surface cluster comprises residues from EF1 and EF2. They include class-specific residues His19, Lys23, Lys24, Gln33, Leu34, Thr35, Phe42, Phe43, Tyr55, Met59, Phe63, Asn66, Lys67, Phe68, Gly69, Tyr70, Met74, Ala78, Leu80, Ser81, Leu82, and Val83. They also include the invariant (within the GCAP family) residues Trp21, Tyr22, Phe25, Glu28, Pro30, Ser31, Glu38, Asp68, Asp72, Phe73, and Glu75. Residues from this region have previously been proposed to play a role in regulating guanylate cyclase (Otto-Bruc et al., 1997; Ames et al., 1999; Li et al., 2001), and the residues Phe73–Glu75 were shown to be critical for GC activation (Schrem et al., 1999). Olshevskaya et al. (1999) have reported that replacing residues Phe78 to Asp113 in GCAP2, with the corresponding region from neurocalcin, produces a chimera that activates GC at high Ca2+ concentrations and inhibits it at low concentrations. Within this region (Phe73 to Asp108 in GCAP1), 12 residues are identified as class-specific and cluster primarily on the exiting helix of EF2. The region from Lys29 to Phe48 in GCAP2 (Lys23–Phe42 in GCAP1) is involved in GC activation and inhibition (Olshevskaya et al., 1999) and contains five class specific residues, four of which are solvent accessible and therefore could interact with GC.

The second cluster is composed predominantly of residues from EF3, with some contribution from EF4. One face of the exiting helix of EF3 is composed entirely of class-specific residues (Leu112, Ile115, Ile116, Ile119, Arg120, Ile122, and Asn123), yet this face does not interact with the entering helix of EF2 indicating that these class-specific residues may mediate some other interaction besides structure stabilization. Residues in the region spanning Phe170 to Asn189 in GCAP2 were shown to help mediate GC activation (Olshevskaya et al., 1999), yet the only ET-identified residues in this area are invariant across the GCAP family, and are located primarily on the exiting helix of EF4. However, one face of the entering helix of EF4 is composed of four class-specific residues that are positioned to interact with the C-terminal helix of GCAP2.

Evolutionary trace analysis of the NCBP family

An ET of the entire neuronal Ca2+-binding protein (NCBP) family, including the GCAPs, calsenilin, neurocalcin, recoverin, visinin, and frequenin families (106 sequences total) reveals a similar pattern of class-specific residue clustering to the ET of the GCAP family, yet several differences emerge (Fig. 11C and D). The almost complete lack of EF1 class-specific residues and the lower number of residues from EF2 in the NCBP trace indicates that the evolutionary importance of this region is specific for the GCAP family and is likely not to play a major role in other members of the NCBP family.

The stretch of class-specific residues including Met59, Tyr55, Ile122, Ile119, Asn123, Ile116, Arg120, and Phe135, is the same for both the GCAP trace and the NCBP trace, indicating that this region from EF2 and EF3 has importance for the entire NCBP family. The pattern of class-specific residues located within the protein is almost the same in the NCBP and GCAP traces, with the exception of EF1 and the exiting helix of EF2. For example, the exiting helix of EF3 has the same face composed entirely of class-specific residues in both the NCBP and the GCAP traces. The entering helix of EF4 also shares the same pattern of class-specific residues in both traces. In the NCBP trace, the entering helix of EF2 shares four of the five class-specific residues found in the GCAP trace, indicating that these residues may be structurally important for the formation of the cleft created by this helix and the EF3 domain. It is not surprising that the class-specific internal residues in both traces are nearly identical, yet the fact that these residues are class-specific suggests that changes to the internal architecture of the protein could have effects on the functional specificity of individual family members.

Discussion

Pairing GCAPs and GCs: cell type gene expression and protein localization

In human retina, GCAP1 and GCAP2 are expressed in both rod and cone photoreceptors (Fig. 1B and C), whereas GCAP3 is expressed in all types of cones, but not rods, and localizes to cone outer segments (Figs 1-3). In contrast, GC1 and GC2 are present in both rods and cones (Figs 4 and 5). These results suggest that four GC/GCAP pairs are possible in rods, whereas six pairs are feasible in cones.

Localization of GCAPs was extended to zebrafish. GCAP1 and GCAP2 localized to rod cells and SS, whereas GCAP3 was found in all subtypes of cones. Four members of sensory organ specific membrane GC (OlGC-R1, OlGC-R2, OlGC-C, OlGC3) were found in teleost fish (Seimiya et al., 1997; Hisatomi et al., 1999). In situ hybridization located OlGC-R1 and OlGC-R2 in rods, and OlGC-C in cones (Hisatomi et al., 1999). OlGC-3 transcripts were localized in photoreceptor cells (Kusakabe & Suzuki, 2001), but it is unclear in which cell type. Therefore, teleost fish may have a different combination of GC-GCAP pairs in rods and cones.

Expression levels of different GCAPs and GCs in rods and cones vary more among species than those of any other known phototransduction enzymes. The diversity of GCAP-GC pairing could be an important mechanism underlying observed differences among animal groups in their electrophysiological responses, such as implicit times, light sensitivity, light adaptation, and rate of dark adaptation (Dowling, 1978; Baylor, 1987; Rodieck, 1998).

Pairing GCAPs and GCs: human and mouse physiology

Insight into the functions of GCAPs and GCs in phototransduction can be gained from naturally occurring mutations and engineered gene disruptions. A dominant form of human retinal degeneration originating in cones results from mutations in GCAP1 (Payne et al., 1998) that lead to high activity of GC even at [Ca2+] that normally inactivate GCAP1 (Dizhoor et al., 1998; Sokal et al., 1998). There was no severe degeneration of rods reported in these patients. This is likely due to either lower expression levels of GCAP1 in human rods as compared to cones (Fig. 1B), instability of the mutant protein in rods, or because of a lower sensitivity of rods than cones to imbalances on Ca2+-homeostasis. Inactivation of GC1 in humans leads to recessive Leber Congenital Amaurosis (LCA), an early onset rod and cone degeneration, that causes initially very limited vision and ultimately leads to total blindness (Perrault et al., 1996; Perrault et al., 2000). This phenotype is consistent with that observed for a naturally occurring GC1 mutation in chickens (Semple-Rowland et al., 1998). A missense mutation (E837D) in GC1 was identified in family members affected with LCA, and a second missense mutation (R838C) was identified in other families with dominant cone–rod dystrophy (Kelsell et al., 1998; Van Ghelue et al., 2000). It was reported that the R838C mutant shows reduced overall catalytic efficiency, reduced stimulation by GCAP2, and an increase in the apparent affinity for GCAP1, as well as a shift to higher [Ca2+] of the GCAP1 Ca2+-sensitivity. These results point out functional differences of GCAP1-GC1 pairs in both rod and cone cells (Tucker et al., 1999). It was suggested that some other mutations affect the connection of photoreceptors to secondary neurons as GC1 is also found in synapses (Gregory-Evans et al., 2000). Although no disease has been associated with GC2 mutations, the expression of this cyclase in rods and cones suggests the importance of this protein in scotopic and photopic vision. Further genetic manipulation and electrophysiological measurements are required for additional insight into the role of this cyclase.

Disruption of the GC1 gene in mice does not lead to changes in the level of GC2, suggesting that the expression of one cyclase is independent of the second (Yang et al., 1999). The a- and b-waves of electroretinograms (ERG) from dark-adapted null mice were suppressed markedly, suggesting a major deficiency in signal transduction. Cones, which are only ≈3% of all murine photoreceptor cells (Carter-Dawson & LaVail, 1979; Applebury et al., 2000), are initially present at normal levels in the retina but disappear by 5 weeks in GC1-null mice (Yang et al, 1999). Surprisingly, rods isolated from these mice, despite having a normal dark current, recovered from a light flash markedly faster in single cell recordings.

Mice lacking both GCAP1 and GCAP2 have altered light responses as measured by ERG and single cell recordings (Mendez et al., 2001). The GC activity from GCAPs−/− ROS showed no Ca2+-dependent modulation, indicating that Ca2+ regulation of GCs had indeed been abolished. Rod flash responses from dark-adapted GCAPs−/− rods were larger and slower than responses from wildtype rods, consistent with absence of GCAP3 in mouse. GCAP1, but not GCAP2, restored wildtype responses when expressed on the GCAPs−/− background (W. Baehr, K. Howes, M. Pennesi, F. Rieke, K. Palczewski and P. Detwiler, unpublished results), suggesting that GCAP2 is dispensable for the rod function.

GCAP3–a cone specific isoform of GCAPs

Rods and cones are known to have similar isozymes of various transduction proteins including opsins, transducins, phosphodiesterases, cGMP-gated channels, and arrestins. The molecular properties of these isozymes result in the physiological differences between rods and cones, such as sensitivity and adaptation processes. Among NCBPs, only visinin and s26, a homologue of recoverin (Goto et al., 1989; Kawamura et al., 1996), and GCAP3 have been reported to be cone specific. However, it was proposed that visinin and s26, found only in nonmammalian species, are not necessary for normal mammalian cone physiology because recoverin is expressed in rods and cones of mammalian photoreceptors (Polans et al., 1993). In this study, we show that zebrafish and human possess a cone specific GCAP isoform, GCAP3, which likely contributes to cone-specific features of [Ca2+] homeostasis, and GC regulation. GCAP3s are predicted to have three functional EF-hands for binding of Ca2+, and a consensus sequence for N-myristoylation at Gly2. Both GCAP3s can activate photoreceptor GC (Fig. 9B) (Haeseleer et al., 1999), and hGCAP3 has been shown to stimulate both GC1 and GC2 in vitro (Haeseleer et al., 1999), suggesting overlapping functions of all three GCAPs in regulation of cone photoresponses.

The human GCAP1 and GCAP2 genes are arranged in a tail-to-tail array on chromosome 6p (Surguchov et al., 1996), while the GCAP3 gene is located on 3q13.1. Chicken and mouse have also conserved the tandem array of these genes. The close relationship between GCAP1 and GCAP3 (Fig. 8) suggests that the GCAP3 gene translocated after formation of the GCAP1/2 tandem array. However, we were unable to demonstrate (by long range genomic PCR) that a tail-to-tail GCAP1/2 gene array exists in zebrafish, so it is possible that the GCAP1/2 are on different chromosomes in this species. Our finding of three GCAPs in zebrafish retina suggests that these gene duplication and translocation events occurred prior to vertebrate diversification.

We were unable to detect GCAP3 cDNA in mouse and bovine retina by RT/PCR and library screening, although the bovine GCAP3 gene was detectable by Southern blot analysis (Haeseleer et al., 1999) Based on our sequence analysis, it appears that the mouse GCAP3 gene is inactive (Fig. 6). This conclusion is supported by our observation that the retina from knockout GCAP1/GCAP2 mice appears to lack GCAP3 as tested using immunoblotting with generic anti-GCAP G2 antibody (data not shown).

GCAPs – key residues for the function and structure

The ET analysis reveals two major clusters of functionally important residues for members of the GCAP family. The first is largely from EF1 and EF2, and the second includes primarily residues from EF3, with some contribution from EF4. These regions have been previously implicated in GC regulation and may be directly involved in GC binding. While most of these positions are also identified by the ET as important for the entire NCBP family, the functional importance of much of the EF1/EF2 cluster appears unique to the GCAP family. Therefore these residues likely emerged early in the evolution of GCAPs as sites important for regulation of GC. The theoretically identified residues are in agreement with recently determined key regions of GCAP1 that are involved in the interaction with photoreceptor GC (Li et al., 2001; Sokal et al, 2001).

In summary, our results demonstrate that GCAP1, GCAP2, GC1 and GC2 are expressed in human rod and cone photoreceptors, but GCAP3 is expressed exclusively in red/green and blue cone photoreceptors. Furthermore, we identified all three GCAPs from teleost fish (zebrafish) retina and localized them to rods, SS (GCAP1 and GCAP2), and all-subtypes of cones (GCAP3), suggesting that GCAP3 is not primate specific as suspected previously. An extensive modification of the GCAP3 gene explains why this transcript/protein is not produced in mouse retina. Mouse is a nocturnal animal in which cone vision plays a minor role as compared to human or fish. Sequence comparisons in conjunction with functional testing of the different GCAPs allowed us to identify key conserved residues that are critical for GCAP structure and function. The importance of these proteins in phototransduction is proven; however, many specific questions still require further analysis. This study provides important novel data on the paring of GCs and GCAPs and in depth characterization of GCAP3 from zebrafish to man.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr Françoise Haeseleer for GCAP clones and the initial help with this project. This research was supported by grants from NIH EY08123 (W.B.) and EY08061 (K.P.), the Ruth and Milton Steinbach Fund, the E.K. Bishop Foundation, the Alcon Research Institute, Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc. (RPB) to the Departments of Ophthalmology at the University of Washington and the University of Utah, a Center Grant from Foundation Fighting Blindness, Inc., to the University of Utah. W.B. and K.P. are recipients of an RPB Senior Investigator Award. W.B. acknowledges an endowment from Ralph and Mary Tuck in Salt Lake City, Utah. M.E.S. was supported by NLM training grant LM07093.

Abbreviations

- AP

alkaline phosphatase

- CaM

calmodulin

- DC

double cones

- ERG

electroretinogram

- EST

expressed sequence tag

- ET

evolutionary trace analysis

- GC

guanylate cyclase

- GCAP

GC-activating protein

- GCIP

GC-inhibitory protein

- LCA

Leber Congenital Amaurosis

- LS

long single cones

- MSA

multiple sequence alignment

- NCBP

neuronal Ca2+-binding protein

- PAGE

polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- PB

phosphate buffer

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PBST

phosphate-buffered saline with 0.1% Triton X-100

- TBST

Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- ROS

rod outer segment

- SS

short single cones

References

- Ames JB, Dizhoor AM, Ikura M, Palczewski K, Stryer L. Three-dimensional structure of guanylyl cyclase activating protein-2, a calcium-sensitive modulator of photoreceptor guanylyl cyclases. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:19329–19337. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.27.19329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Applebury ML, Antoch MP, Baxter LC, Chun LL, Falk JD, Farhangfar F, Kage K, Krzystolik MG, Lyass LA, Robbins JT. The murine cone photoreceptor: a single cone type expresses both S and M opsins with retinal spatial patterning. Neuron. 2000;27:513–523. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barthel LK, Raymond PA. In situ hybridization studies of retinal neurons. Meth. Enzymol. 2000;316:579–590. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)16751-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baylor DA. Photoreceptor signals and vision. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1987;28:34–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter-Dawson LD, LaVail MM. Rods and cones in the mouse retina II. Autoradiographic analysis of cell degeneration using tritiated thymidine. J. Comp. Neurol. 1979;188:263–272. doi: 10.1002/cne.901880205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuenca N, Lopez S, Howes K, Kolb H. The localization of guanylyl cyclase-activating proteins in the mammalian retina. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1998;39:1243–1250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dizhoor AM, Boikov SG, Olshevskaya E. Constitutive activation of photoreceptor guanylate cyclase by Y99C mutant of GCAP-1. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:17311–17314. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.28.17311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dizhoor AM, Lowe DG, Olshevskaya EV, Laura RP, Hurley JB. The human photoreceptor membrane guanylyl cyclase, RetGC, is present in outer segments and is regulated by calcium and a soluble activator. Neuron. 1994;12:1345–1352. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90449-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dizhoor AM, Olshevskaya EV, Henzel WJ, Wong SC, Stults JT, Ankoudinova I, Hurley JB. Cloning, sequencing, and expression of a 24-kDa Ca2+-binding protein activating photoreceptor guanylyl cyclase. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:25200–25206. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.42.25200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling JE. How the retina ‘sees.’. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1978;17:832–834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorczyca WA, Gray-Keller MP, Detwiler PB, Palczewski K. Purification and physiological evaluation of a guanylate cyclase activating protein from retinal rods. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:4014–4018. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.4014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorczyca WA, Polans AS, Surgucheva I, Subbaraya I, Baehr W, Palczewski K. Guanylyl cyclase activating protein: a calcium-sensitive regulator of phototransduction. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:22029–22036. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.37.22029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto K, Miki N, Kondo H. An immunohistochemical study of pinealocytes of chicks and some other lower vertebrates by means of visinin (retinal cone-specific protein) - immunoreactivity. Arch. Histol. Cytol. 1989;52:451–458. doi: 10.1679/aohc.52.suppl_451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory-Evans K, Kelsell RE, Gregory-Evans CY, Downes SM, Fitzke FW, Holder GE, Simunovic M, Mollon JD, Taylor R, Hunt DM, Bird AC, Moore AT. Autosomal dominant cone-rod retinal dystrophy (CORD6) from heterozygous mutation of GUCY2D, which encodes retinal guanylate cyclase. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:55–61. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(99)00038-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haeseleer F, Sokal I, Li N, Pettenati M, Rao N, Bronson D, Wechter R, Baehr W, Palczewski K. Molecular characterization of a third member of the guanylyl cyclase- activating protein subfamily. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:6526–6535. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.10.6526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hisatomi O, Honkawa H, Imanishi Y, Satoh T, Tokunaga F. Three kinds of guanylate cyclase expressed in medaka photoreceptor cells in both retina and pineal organ. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999;255:216–220. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howes K, Bronson JD, Dang YL, Li N, Zhang K, Ruiz C, Helekar B, Lee M, Subbaraya I, Kolb H, Chen J, Baehr W. Gene array and expression of mouse retina guanylate cyclase activating proteins 1 and 2. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1998;39:867–875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kachi S, Nishizawa Y, Olshevskaya E, Yamazaki A, Miyake Y, Wakabayashi T, Dizhoor A, Usukura J. Detailed Localization of Photoreceptor Guanylate Cyclase Activating Protein-1 and -2 in Mammalian Retinas using Light and Electron Microscopy. Exp. Eye Res. 1999;68:465–473. doi: 10.1006/exer.1998.0629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura S, Kuwata O, Yamada M, Matsuda S, Hisatomi O, Tokunaga F. Photoreceptor protein s26, a cone homologue of Smodulin in frog retina. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:21359–21364. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.35.21359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelsell RE, Gregory-Evans K, Payne AM, Perrault I, Kaplan J, Yang R-B, Garbers DL, Bird AC, Moore AT, Hunt DF. Mutations in the retinal guanylate cyclase (RETGC-1) gene in dominant con-rod dystrophy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1998;7:1179–1184. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.7.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura M. The neutral theory of molecular evolution – A review of recent evidence. Jpn. J. Genet. 1991;66:367–386. doi: 10.1266/jjg.66.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusakabe T, Suzuki N. A cis-regulatory element essential for photoreceptor cell-specific expression of a medaka retinal guanylyl cyclase gene. Dev. Genes Evol. 2001;211:145–149. doi: 10.1007/s004270100136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N, Fariss RN, Zhang K, Otto-Bruc A, Haeseleer F, Bronson JD, Qin N, Yamazaki A, Subbaraya I, Milam AH, Palczewski K, Baehr W. Guanylate cyclase inhibitory protein is a frog retinal Ca2+ binding protein related to mammalian guanylate cyclase activating proteins. Eur. J. Biochem. 1998;252:591–599. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2520591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N, Sokal I, Bronson JD, Palczewski K, Baehr W. Identification and functional regions of guanylate cyclase-activating protein 1 (GCAP1) using GCAP1/GCIP chimeras. Biol. Chem. 2001;382:1179–1188. doi: 10.1515/BC.2001.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtarge O, Bourne HR, Cohen FE. Evolutionarily conserved G·αβγ binding surfaces support a model of the G protein-receptor complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:7507–7511. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Seno K, Nishizawa Y, Hayashi F, Yamazaki A, Matsumoto H, Wakabayashi T, Usukura J. Ultrastructural localization of retinal guanylate cyclase in human and monkey retinas. Exp. Eye Res. 1994;59:761–768. doi: 10.1006/exer.1994.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe DG, Dizhoor AM, Liu K, Gu Q, Spencer M, Laura R, Lu L, Hurley JB. Cloning and expression of a second photoreceptorspecific membrane retina guanylyl cyclase (RetGC), RetGC-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:5535–5539. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez A, Burns ME, Sokal I, Dizhoor AM, Baehr W, Palczewski K, Baylor DA, Chen J. Role of guamylate cyclase-activating proteins (GCAPs) in setting the flash sensititvity of rod photoreceptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:9948–9953. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171308998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mighell AJ, Smith NR, Robinson PA, Markham AF. Vertebrate pseudogenes. FEBS Lett. 2000;468:109–114. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01199-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olshevskaya EV, Boikov S, Ermilov A, Krylov D, Hurley JB, Dizhoor AM. Mapping Functional Domains of the Guanylate Cyclase Regulator Protein, GCAP-2. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:10823–10832. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.10823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto-Bruc A, Fariss RN, Haeseleer F, Huang J, Buczylko J, Surgucheva I, Baehr W, Milam AH, Palczewski K. Localization of guanylate cyclase activating protein 2 in mammalian retinas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:4727–4732. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palczewski K, Subbaraya I, Gorczyca WA, Helekar BS, Ruiz CC, Ohguro H, Huang J, Zhao X, Crabb JW, Johnson RS, Walsh KA, Gray-Keller MP, Detwiler PB, Baehr W. Molecular cloning and characterization of retinal photoreceptor guanylyl cyclase activating protein (GCAP) Neuron. 1994;13:395–404. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90355-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne AM, Downes SM, Bessant DA, Taylor R, Holder GE, Warren MJ, Bird AC, Bhattacharya SS. A mutation in guanylate cyclase activator 1A (GUCA1A) in an autosomal dominant cone dystrophy pedigree mapping to a new locus on chromosome 6p21.1. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1998;7:273–277. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.2.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrault I, Rozet J-M, Calvas P, Gerber S, Camuzat A, Dollfus H, Chatelin S, Souied E, Ghazi I, Leowski C, Bonnermaison M, Le Paslier D, Frezal J, Dufier J-L, Pittler SJ, Munnich A, Kaplan J. Retinal-specific guanylate cyclase gene mutations in Leber's congenital amaurosis. Nature Genet. 1996;14:461–464. doi: 10.1038/ng1296-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrault I, Rozet JM, Gerber S, Ghazi I, Ducroq D, Souied E, Leowski C, Bonnemaison M, Dufier JL, Munnich A, Kaplan J. Spectrum of retGC1 mutations in Leber's congenital amaurosis. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2000;8:578–582. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polans A, Baehr W, Palczewski K. Turned on by Ca2+ǃ The physiology and pathology of Ca2+-binding proteins in the retina. Trends Neurosci. 1996;19:547–554. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)10059-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polans AS, Burton MD, Haley TL, Crabb JW, Palczewski K. Recoverin, but not visinin, is an autoantigen in the human retina identified with a cancer-associated retinopathy. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1993;34:81–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond PA, Barthel LK, Rounsifer ME, Sullivan SA, Knight JK. Expression of rod and cone visual pigments in goldfish and zebrafish: a rhodopsin-like gene is expressed in cones. Neuron. 1993;10:1161–1174. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90064-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodieck RW. The First Steps in Seeing. Sinauer Associates; Sunderland, MA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen B, Beddington R. Detection of mRNA in whole mounts of mouse embryos using digoxigenin riboprobes. Meth. Mol. Biol. 1994;28:201–208. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-254-x:201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenmakers TJ, Visser GJ, Flik G, Theuvenet AP. CHELATOR: an improved method for computing metal ion concentrations in physiological solutions. Biotechniques. 1992;12:870–879. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrem A, Lange C, Beyermann M, Koch KW. Identification of a domain in guanylyl cyclase-activating protein 1 that interacts with a complex of guanylyl cyclase and tubulin in photoreceptors. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:6244–6249. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.10.6244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seimiya M, Kusakabe T, Suzuki N. Primary structure and differential gene expression of three membrane forms of guanylyl cyclase found in the eye of the teleost Oryzias latipes. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:23407–23417. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.37.23407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semple-Rowland SL, Lee NR, Van-Hooser JP, Palczewski K, Baehr W. A null mutation in the photoreceptor guanylate cyclase gene causes the retinal degeneration chicken phenotype. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:1271–1276. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shyjan AW, de Sauvage FJ, Gillett NA, Goeddel DV, Lowe DG. Molecular cloning of a retina-specific membrane guanylyl cyclase. Neuron. 1992;9:727–737. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90035-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokal I, Li N, Klug CS, Filipek S, Hubbell WL, Baehr W, Palczewski K. Calcium-sensitive regions of GCAP1 as observed by chemical modifications, fluorescence and EPR spectroscopies. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:43361–43373. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103614200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokal I, Li N, Surgucheva I, Warren MJ, Payne AM, Bhattacharya SS, Baehr W, Palczewski K. GCAP1 (Y99C) mutant is constitutively active in autosomal dominant cone dystrophy. Mol. Cell. 1998;2:129–133. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80121-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowa ME, He W, Slep KC, Kercher MA, Lichtarge O, Wensel TG. Prediction and confirmation of a site critical for effector regulation of RGS domain activity. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2001;8:234–237. doi: 10.1038/84974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowa ME, He W, Wensel TG, Lichtarge O. A regulator of G protein signalling interaction surface linked to effector specificity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:1483–1488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.030409597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subbaraya I, Ruiz CC, Helekar BS, Zhao X, Gorczyca WA, Pettenati MJ, Rao PN, Palczewski K, Baehr W. Molecular characterization of human and mouse photoreceptor guanylate cyclase activating protein (GCAP) and chromosomal localization of the human gene. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:31080–31089. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surguchov A, Ruiz CC, Rao PN, Palczewski K, Baehr W. Cloning, expression, and chromosomal localization of the human and mouse GCAP2 gene. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1996;37:335. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker CL, Woodcock SC, Kelsell RE, Ramamurthy V, Hunt DM, Hurley JB. Biochemical analysis of a dimerization domain mutation in RetGC-1 associated with dominant cone-rod dystrophy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:9039–9044. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ghelue M, Eriksen HL, Ponjavic V, Fagerheim T, Andreasson S, Forsman-Semb K, Sandgren O, Holmgren G, Tranebjaerg L. Autosomal dominant cone-rod dystrophy due to a missense mutation (R838C) in the guanylate cyclase 2D gene (GUCY2D) with preserved rod function in one branch of the family. Ophthalmic Genet. 2000;21:197–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang RB, Garbers DL. Two eye guanylyl cyclases are expressed in the same photoreceptor cells and form homomers in preference to heteromers. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:13738–13742. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.21.13738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang RB, Robinson SW, Xiong WH, Yau KW, Birch DG, Garbers DL. Disruption of a retinal guanylyl cyclase gene leads to cone-specific dystrophy and paradoxical rod behavior. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:5889–5897. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-14-05889.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]